ABSTRACT

Transnational networks of sub-national authorities are an established and growing phenomenon in Europe, where they perform a number of (soft) governance functions for their members, often in direct connection with European Union (EU) institutions. Differentiation is an inherent characteristic of sub-national authority networks, which is nonetheless still largely unexplored. Building on original empirical data, we identify three dimensions of differentiation generated by networks – ‘insider-outsider’, ‘compound’ and ‘multi-level’ differentiation – and discuss their implications for the efficiency, effectiveness and legitimacy of these organisations. Based on our analysis, we also sketch some avenues for future research connecting the national and sub-national dimensions of differentiation in Europe.

In the context of European governance, differentiation – the creation of flexible and non-homogeneous forms of cooperation among territorial authorities – is a topic most commonly conceived and studied in state-centric terms, namely by seeing European Union (EU) member states as the primary instigators, subjects and implementers of differentiated integration (DI) arrangements (see for example Andersen and Sitter Citation2006; Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020; Stubb Citation1996).Footnote1 This makes sense intuitively, for state-led DI is the foremost embodiment of differentiation within the continent. Yet, one cannot but see the irony of such state-centrism within the context of a polity – the EU – whose main purpose has been, historically, to challenge the nation state as the dominant institutional form in Europe. More importantly, focusing mostly on the state in studying differentiation carries the risk of obscuring other arenas in which differentiation plays an important role, and which can contribute to our understanding of this concept and its implications for the politics and governance of Europe. Such is the case for transnational networks of sub-national authorities.

Sub-national authority networks are an established and growing phenomenon in Europe, some with historical precedents dating back to the early 20th century, such as the United Cities and Local Governments network, which originates from the Union Internationale des Villes founded in 1913, and the International Federation for Housing and Planning, also founded in 1913 (Couperus Citation2011). They span a wide number of policy areas and provide their members (primarily cities and regions)Footnote2 with a range of benefits and tools of (soft) governance. Sub-national authority networks can be seen as both a consequence and a manifestation of a number of epochal transformations in Europe and elsewhere, such as globalisation, transnationalism and the rescaling of governance functions (Brenner Citation2004; Leitner Citation2004; Sassen Citation2001; Taylor Citation2005). More concretely, they are part and parcel of Europe’s system of multi-level governance, insofar as they participate in the EU’s policymaking cycle at various stages and in various ways (Hooghe Citation1995; Perkmann Citation2007; Tortola Citation2013; Citation2017).

Sub-national authority networks are loci of institutional flexibility and differentiation par excellence, due to their very nature and characteristics, above all the fact that they gather specific sub-sets of local and regional governments in a non-compulsory fashion. Differentiation is also engendered by the ways networks interlock with one another and with other levels of government in the continent, primarily the supranational one. Studying networks, therefore, can enrich our overall understanding of differentiation in Europe by expanding this notion beyond its predominant state-centric focus. At the same time, examining sub-national authority networks can potentially offer new perspectives and lessons for more traditional, state-centric forms of differentiation, either indirectly by analogical reasoning, or directly insofar as network governance connects to state-led (differentiated) integration.

This article presents an analysis of sub-national authority networks in Europe through the lens of differentiation, supported by an original dataset of 96 networks and six elite interviews with network practitioners within the energy policy sub-set, conducted between July and September 2020.Footnote3 Our analysis contributes to the literature on sub-national networks, which so far has dealt with the topic of differentiation only sporadically and unsystematically. Above all, this study aims to encourage differentiation scholars to look beyond state-centric DI, as they further develop this research programme.

We proceed as follows: the next section introduces sub-national authority networks by briefly discussing their history, functions and main empirical traits. We then examine, in the following three sections, three distinct dimensions of differentiation generated by sub-national authority networks: ‘insider-outsider’, ‘compound’, and ‘multi-level’ differentiation. Briefly, insider-outsider differentiation concerns the distinction between members and non-members of networks; compound differentiation refers to the different degrees of ‘insiderness’ and ‘outsiderness’ generated by overlaps in the membership of different local authority networks; finally, multi-level differentiation relates to mismatches between EU (differentiated) membership and the geographic coverage of local authority networks, whenever these two levels operate in the same policy areas. For each type of differentiation, the article discusses advantages and drawbacks in the areas of organisational efficiency, political and administrative effectiveness, and legitimacy defined primarily in terms of inclusiveness and representativeness of sub-national authorities. The final section concludes by recapping our findings and sketching some avenues for future research connecting the national and sub-national dimensions of differentiation.

Sub-national authority networks in the EU

For the purposes of this article, we define sub-national authority networks as horizontal, voluntary and independent organisations connecting local and/or regional authorities across state boundaries in a stable manner, with the aim of achieving some common goal and/or producing mutually beneficial services. This broad definition includes a wide range of networks in terms of type of members, size, geographic span, organisational density and thematic focus. It leaves out, however, all-inclusive organisations of sub-national authorities formally embedded in a wider institutional structure – such as the EU’s Committee of the Regions or the Council of Europe’s Congress of Local and Regional Authorities – and collaborations that are episodic or mere emanations of specific projects (for instance, in the context of the EU’s regional policy).

The activity of transnational networking among sub-national authorities can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when municipalities, taking up ever more public tasks and responsibilities, shared experiences, best practices and (administrative) technologies across borders in the realm of public utilities, public transport, municipal bureaucracy and social services (Saunier and Ewen Citation2008; Hietala Citation1987). After the Second World War, the institutional make-up of transnational local and regional networks gradually thickened, for instance with the creation of a number of experiments involving cities as well as regions, such as town twinning (Couperus and Vrhoci Citation2019), Euroregions (for example, the Dutch-German one, established in 1958) and larger organisations like the Council of European Municipalities, founded in 1951. However, it is really in the past three decades or so that networking has gathered pace, stimulated by a number of converging factors such as improvements in cross-border communications, power and competence gains for local and regional authorities, encouragement (and in some cases initiation) by inter- and supra-national institutions (such as the United Nations [UN], the Council of Europe and, above all, the European Community/Union) and, finally, the emergence of a number of new and inherently transnational challenges, in the first place environmental ones (Ewen and Hebbert Citation2007; Kuznetsov Citation2015; Le Galès Citation2002; Murphy Citation1993; Tavares Citation2016). Taken together, these trends have contributed to the establishment of dozens of networks of various kinds, in particular in Europe, which stands today as one of the most densely networked areas in the world (Acuto Citation2013; Acuto and Leffel Citation2020).

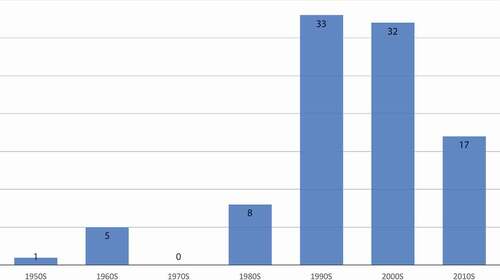

Comprehensive and reliable data on sub-national authority networks in Europe (and elsewhere) is hard to come by.Footnote4 For our study, we therefore collected and coded an original dataset of 96 networks operating, fully or partially, in the EU’s territory, comprising 30 city networks, 30 regional networks and 36 mixed membership networks (see Online Appendix for more details on data collection procedures).Footnote5 While this dataset is likely to underestimate the total number of sub-national authority organisations in the continent, we believe that it provides us with a reliable and broadly representative sample of Europe’s current sub-national network landscape. shows the distribution of networks in our sample by decade of establishment.

The picture emerging from the graph is consistent with the above account: over two-thirds of the networks in our sample were established in the 1990s and 2000s. Environmental and climate change activism on the part of many sub-national governments, in conjunction with the UN, played an important role in accelerating networking in this period, by spurring the creation of a number of important networks – such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, the Climate Alliance, Energy Cities and later the C40 network – and, more generally, promoting the notion of sub-national participation and leadership in actions against global warming, above all through the UN’s Agenda 21 (Acuto and Leffel Citation2020; Bansard et al. Citation2017; Bulkeley et al. Citation2003; Keiner and Kim Citation2007).

The prominence of environmental themes among sub-national authority networks is confirmed by , which shows the static breakdown of our network dataset by policy area. Slightly over a quarter of the organisations surveyed work exclusively or predominantly on environmental policy or in the adjacent area of energy. At the same time, taken together, sub-national authority networks cover a wide array of policy sectors, oftentimes combining more than one, as shown by the considerable portion of generalist networks, which work in two or more fields without a stated hierarchy among them. In this latter category, one finds a number of broad organisations – such as Eurocities, the Assembly of European Regions or the Association of European Border Regions – as well as regionally specific ones, which tackle a range of topics within a well-delimited geographic area, such as the Alps-Adriatic Alliance, the Alpine network Arge-Alp or the French-German PAMINA Eurodistrict. These findings are in line with previous surveys of the field (for example, Davidson et al. Citation2019; Keating Citation1999; Niederhafner Citation2013; Rapoport et al. Citation2019).

Figure 2. Thematic breakdown of sub-national authority networksNote: Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Regardless of the field(s) in which they operate, the functions of sub-national authority networks tend to be similar. As voluntary, non-coercive and often not particularly wealthy organisations, the main resources on which networks base their activities (and authority) are knowledge and information, in their various forms. Among the activities to which networks devote most of their time, one finds policy learning and innovation, exchanges of know-how and best practices, technical support to local and regional governments, project formulation, development and implementation, and further networking and matchmaking among members (for example, for project consortia) (Keating Citation1999; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009; Leitner Citation2004; Niederhafner Citation2013). Sub-national authority networks also perform transnational interest representation functions, in particular vis-à-vis EU institutions. In this respect, they exemplify the neo-functionalist notion of “political spillover”, that is, the increasing organisation of political activity – including lobbying – at the supra-national level as more policy competences are integrated (Haas Citation1958; Schmitter Citation1969).

With the growing importance of sub-national authority networks in Europe’s political and institutional landscape has come increasing scholarly interest in these organisations. Over the past couple of decades, research across several disciplines – notably Political Geography, Urban Studies, Regional Studies, International Relations and, more recently, European Studies – has produced important findings on aspects such as the drivers of networks (for example, Huggins Citation2018a; Keating Citation1999; De Sousa Citation2013), their main types (for instance, Callanan and Tatham Citation2014; Murphy Citation1993), their organisational dynamics (for example, Bulkeley et al. Citation2003; Mocca Citation2018) and their relationships with other governance levels, most notably the EU (among them, Heinelt and Niederhafner Citation2008; Hooghe Citation1995).

What still remains largely unexplored in this literature is the differentiation perspective. Differentiation is an inherent feature of networks, above all because they gather together specific sets of sub-national governments in a voluntary and flexible way. This, in turn, can have significant implications for the nature, effectiveness and even legitimacy of their actions. Analysing differentiation in the sub-national arena can, therefore, not only fill an important gap in the network literature, but also, and more importantly for this Special Issue, contribute to moving the study of differentiation beyond its traditional state-centric perimeter. The remainder of the article takes a first stab at such an analysis, by describing and reflecting on three main dimensions of institutional differentiation – that is, differentiation arising from formal membership in networks – emerging from our empirical data: ‘insider-outsider’; ‘compound’; and ‘multi-level’.

Insider-outsider differentiation

The first type of differentiation created by sub-national authority networking is, very simply, that separating members of each network from non-members. This ‘insider-outsider’ differentiation is the most straightforward kind, and the most similar to traditional state-based differentiated integration. Unlike the latter, however, insider-outsider differentiation accompanies networks almost by definition: given these institutions’ voluntary nature and often specialised focus, it would be hard to imagine a network comprising each and every potentially eligible member. Our data reveal tremendous variability in territorial membership size: ranges for city, region and mixed networks are, respectively, between 2 and 9,741; between 4 and 151; and between 2 and 1,709.Footnote6 But even the largest city and regional organisations – the Covenant of Mayors and the Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions – do not come close to being all-inclusive.

Sheer numbers do not tell the whole story, however. Broadly speaking, insider-outsider differentiation in networks can be broken down into two dimensions. The first concerns limits established by the network’s mission to who can participate, based on certain attributes that can be geographic, demographic, institutional or of other kinds. Cross-border cooperation networks – such as the Arge-Alp or PAMINA – are a typical case of this ’statutory differentiation’. Other examples in our dataset include the metropolitan areas network METREX, the Association of European Border Regions, the Association Internationale des Maires Francophones, the Unión de Ciudades Capitales Iberoamericanas and the European Straits Initiative, just to mention a few. The second dimension concerns actual participation in the network compared to the latter’s potential coverage as statutorily defined. (To mention one example from our dataset, the Union of the Baltic Cities is differentiated by statute, as it focuses on a specific region, but also by actual coverage, for not all Baltic cities participate in the network). All the networks in our dataset entail at least one of these two dimensions of insider-outsider differentiation.

Differentiation has several advantages for sub-national authority networks. The most obvious is that, in principle, it allows sub-sets of cities and/or regions sharing similar features, needs and problems to get together in a flexible fashion and define the perimeter of the organisation to best fit their common goals. This, in turn, should increase the network’s internal coherence in terms of the framing and definition of problems, governance outlook and policy agendas, ultimately improving the effectiveness of joint activities (Interview 3 Citation2020; Interview 4 Citation2020). Consider, for instance, these remarks by one of our interviewees:

I know that […] other regions would like to participate [in our network], but at this point, the political level […] decided not to go too quick too broad, but rather to deepen work within the network. […] And we stick to our definition, [whereby a member must be] a region with constitutional responsibilities (and not just an autonomous region within a nation state […] with some legislative competencies), and economically strong – strong enough to [be able to] share in with the other [member] regions (Interview 4 Citation2020).

For organisations that are more open-ended in terms of (potential) membership, differentiation also means greater flexibility for groups of pioneers to launch joint endeavours to which more sub-national governments will adhere later on. From an organisational standpoint, and especially for more exclusive organisations, having smaller groups of insiders may also facilitate the management of the network and its internal flow of information and communication, and increase the density and depth of cooperation among members (Leitner Citation2004; Interview 4 Citation2020). Finally, insider-outsider differentiation may also be regarded as advantageous to the outsiders of an organisation, insofar as it involves the freedom for sub-national authorities that are not willing or ready to join a network to remain unencumbered by it, organisationally and financially.

On the other hand, insider-outsider differentiation presents four major drawbacks. The first is that differentiation may lead to free-riding on the part of outsiders, whenever they are able to benefit from public goods produced by the network, not only in the area of ‘external governance’, such as lobbying and interest representation, but also in ‘internal governance’ – that is, the generation of know-how, best practices and standards (Hooghe Citation1995; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009). While this is, admittedly, not the biggest problem for networks – some of which have, in fact, the ambition to provide leadership beyond their confines – free-riding may nonetheless lead to the suboptimal production of some of the network’s services.

A second, and even bigger drawback of differentiation concerns those services that take the form of club goods, from which outsiders can therefore be excluded, such as technical support, training or access to privileged information (Capello Citation2000). Clearly, the disadvantage here is particularly marked for those outsiders that are not so by virtue of a deliberate choice, but rather because they are unable to join, for example, for financial or administrative reasons. For smaller sub-national governments, exclusion might even end up feeding a vicious circle whenever the capacities that would facilitate participation in a network – which can be as simple as having an officer in charge of international and EU relations – are exactly those that would be boosted by joining the network in the first place (Kern and Löffelsend Citation2008; Tortola Citation2012; Citation2016; Interview 1 Citation2020).

The third drawback is the mirror image of the coherence argument presented above. Reducing diversity within a network might become a disadvantage in all those areas in which variety – of various kinds: institutional, cultural, political, etc. – is a plus, for instance, in the areas of policy learning and innovation (Burch et al. Citation2018; Wolfram et al. Citation2019). To the extent that these are seen as priorities, a network might be better served by an inclusive strategy that tries to increase the number, or at least the types, of participants.

Finally, and connected to the foregoing, insider-outsider differentiation may diminish the representativeness of networks in their interactions with other actors (most notably, EU institutions, but also other inter- and transnational organisations), and possibly impinge on the legitimacy of their actions in these contexts (Hooghe Citation1995; Pirozzi et al. Citation2017). This problem might be particularly pronounced for networks characterised by a geographically skewed membership. Kristine Kern and Harriet Bulkeley (Citation2009) list a few examples of such unequal representation in the crowded environmental field, noting how most cities participating in the prominent Climate Alliance network are located in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, while Cities for Climate Protection and Energie-Cités have their strongholds, respectively, in Finland and the UK, and in France. To the extent that interactions with the EU are concerned, the unequal distribution of network participants might also produce a more specific mismatch between the countries represented in the network and EU member states, which will be discussed in greater detail below, as we explore ‘multi-level’ differentiation.

Compound differentiation

The differentiation picture becomes more complicated as we move from considering networks individually to looking at them collectively within EU boundaries. Unlike what happens at the state level, where we usually find one main cooperation or integration arrangement per policy area, at the sub-national level several – and in some cases many – networks usually coexist within each policy area, often with (partly) overlapping missions and memberships.Footnote7 This multiplies the points of differentiation created by networks, generating what we call here ‘compound differentiation’, namely a situation in which sub-national governments can have various degrees and types of ‘insiderness’ and ‘outsiderness’, depending on how many (if any) and which networks they take part in. Compound differentiation is especially important in network-dense fields, such as environmental policy.

The presence of different networks in the same policy area may be taken as a mitigating factor for some of the drawbacks of insider-outsider differentiation. Coexisting networks may, for instance, multiply opportunities for cooperation among sub-national governments, while preserving a certain degree of coherence within each organisation (Interview 1 Citation2020; Interview 2 Citation2020; Interview 3 Citation2020). Consider the case of C40, a network working on climate change with a specific focus on large cities, whose interests and preferences might be overly diluted in the context of a more generalist organisation. Multiple networks can also be a stimulus to healthy competition among organisations, especially when it comes to policy innovation and the elaboration of projects (Keiner and Kim Citation2007; Mocca Citation2018; Interview 2, Citation2020). Finally, the existence of different organisations within the same policy areas may encourage a virtuous division of labour in the network’s modus operandi and specific mix of services, which can in turn facilitate ad-hoc cooperative arrangements that take advantage of the synergies among different organisations (Keiner and Kim Citation2007; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009; Interview 2 Citation2020; Interview 3 Citation2020). One of our interviewees expresses this idea rather clearly:

[W]e are even thinking to […] start working with [organisation names omitted] based on their membership, because we are becoming […] specialised in infrastructure, […] in finance, in […] delivering those projects. […] [W]e feel more and more that other actors are getting better than us at working with the regions on capacity building, [and being] the voice of the sub-national [level]. […] I think what we’ll see more and more is that all these networks of cities and regions – because actually there are many of them – will start to get more and more specialised (Interview 2 Citation2020).

At the same time, the coexistence of multiple networks may increase the risk of duplicating efforts and even wasting resources, both on the side of networks themselves, and on that of financing institutions – especially, but not only, the EU – which might be tempted to spread their support broadly across organisations rather than picking winners and losers (Interview 1 Citation2020; Interview 2 Citation2020). Additionally, excessive fragmentation among networks can lead (some) sub-national authorities to lose some of the advantages and economies of scale that come with unity and size, such as political weight or the ability to establish an effective administrative and policy infrastructure at the centre of the network (Barber Citation1997; Capello Citation2000). This is exacerbated by the fact that a sub-national government’s adherence to one network rather than another is sometimes driven not so much by functional reasoning with respect to the size, shape and mission of the organisation, but by more contingent factors such as personal connections, pre-existing links among sub-national authorities or even effective public relations on the part of the network (Barber Citation1997; Tavares Citation2016; Interview 3 Citation2020; Interview 4 Citation2020; Interview 6 Citation2020).

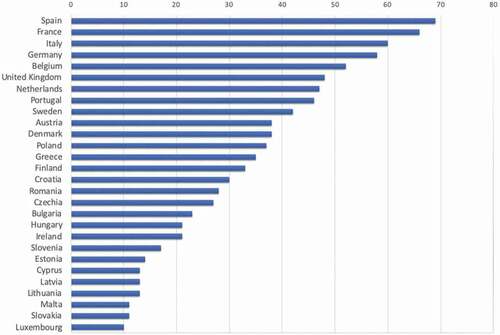

As noted above, membership overlaps among networks further increase the range of differentiation among sub-national governments, creating what one could dub ‘super-insiders’, namely local or regional governments that participate in several networks per policy area. Previous research has found, unsurprisingly, that the greatest number of transnational connections tend to be found among the biggest and most resourceful sub-national governments: for instance, major cities such as Paris, Barcelona, Brussels, Berlin or Rome (Acuto and Leffel Citation2020; Rapoport et al. Citation2019). The number and size of networks in our dataset do not allow us to draw a comprehensive and granular picture of network membership overlap. As a rough proxy, however, one can look at network membership by EU member state, shown in .

As one could expect, the figure suggests a general relation between country size and membership coverage: cities and regions in bigger countries tend to participate in a greater number of networks. Interestingly, however, there seems to be also a broad connection between length of EU membership and number of networks: older member states are generally those whose sub-national governments are more connected across borders. This is consistent with what we have noted above about the central role of the EU in encouraging, supporting and sometimes even creating transnational networks of sub-national governments in its territory.

Membership overlaps between networks may help redress some of the problems generated by the existence of multiple networks in the same policy area, as cities and regions participating in several organisations can play an important role in inter-network communication, mediation and collaboration (Keiner and Kim Citation2007; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009; Interview 5 Citation2020). On the other hand, membership overlaps could also produce some undesirable effects for the super-insiders, who might at times find themselves having to juggle conflicting demands from different networks.

The greatest potential drawback of membership overlaps, however, is that it may further magnify the hierarchies among sub-national governments (or clusters thereof) that already exist within, and are reinforced by, each individual network (Acuto Citation2013; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009; Mocca Citation2018). Being in the middle of different networks allows super-insiders to benefit from the club goods produced by each of them, provides them with different arenas to which they can turn according to their needs and affords them with better connections and access to other levels of government, above all the EU (Keiner and Kim Citation2007).

Multi-level differentiation

With ‘multi-level’ differentiation we indicate the sort of differentiation originating at the intersection of sub-national authority networks and state-based (differentiated) integration in the EU. To a significant degree, networks work on policy areas in which the EU is also involved, in a more or less extended fashion. It is, therefore, very common for networks to be in contact with the EU and its work, either directly (for instance, by taking part in EU-supported projects, or by playing a consultative role in EU decision-making), or indirectly, by operating in areas that are exposed to processes of Europeanisation (Interview 2 Citation2020; Interview 4 Citation2020). This raises the issue of possible mismatches between the membership of the Union (or some of its differentiated integration arrangements) on the one hand, and the countries represented in the various sub-national authority organisations on the other. More precisely, we identify here two kinds of multi-level differentiation, which we term ‘internal’ and ‘external’, building on the terminology of DI studies (Leuffen et al. Citation2013). The former occurs whenever sub-national authorities from one or more member states are absent from a network interacting with the EU; the latter takes place when local authority networks operating on EU territory include members from non-EU countries.Footnote8

Internal multi-level differentiation is prevalent in our dataset, in which the Covenant of Mayors – a network initiated by the European Commission – is the only organisation including sub-national governments from each and every EU member state. More generally, networks in the dataset span the whole range between one and 28 member states, with an overall average slightly lower than 10. In several cases, participation from a limited number of member states is a direct result of the design and rationale of the network, which we discussed above – we would not expect, for example, a cross-border cooperation organisation to involve countries far from the border in question, or landlocked countries to be represented in a network of coastal regions.

In other cases, however, the limited representation of countries in the network is less obviously justifiable, and potentially more problematic. In the first place, it may add a distinctly national dimension to the issues of representativeness and legitimacy mentioned above, whenever networks participate, more or less directly, in the EU’s decision-making process. This would be an example of what Sandra Lavenex and Ivo Križić (Citation2019) refer to as “organisational differentiation” – the differential participation of sub-national entities in European processes of governance – which is especially problematic because the involvement of sub-national organisations in supranational policymaking is often regarded as an important channel to alleviate the democratic deficit of EU institutions (Davidson et al. Citation2019; Heinelt and Niederhafner Citation2008; Hooghe Citation1995). The absence of certain countries in the membership of networks might also pose a problem of policy effectiveness insofar as it may remove nation-specific needs, considerations, administrative experience etc. from the policy input provided by these organisations.

Limited national representation in networks may also create a number of top-down issues in the relationship between supra- and sub-national governments. First and most tangibly, it could limit the ability of sub-national authorities from certain countries to take advantage of EU projects and funds. More importantly, it could truncate the intra-network flow of information, know-how, best practices, etc. along national lines. This is more so if we consider that members of a transnational network may, in some cases, also act as nodes that relay domestically (for example, through national networks) what they have learnt from the EU as well as their peers abroad. To the extent that intra-network learning processes are connected to EU policies, not being represented in one or more networks may also affect a country’s capacities and opportunities in terms of sub-national-level Europeanisation (Huggins Citation2018b; Kern and Bulkeley Citation2009; Tortola Citation2016).

External multi-level differentiation is also frequent among sub-national networks. shows the incidence of this type of differentiation in our dataset, by ordering networks according to the percentage of EU-based versus non-EU-based members. As the figure shows, of the 96 networks in our sample, only 35 have an all-EU-based membership. The remaining 61 include one or more members based outside the EU, and 25 of these have a majority of non-EU-based members.

The questions raised by this second type of multi-level differentiation are, in part, a mirror image of those just described. Insofar as networks function as interfaces between their members and EU institutions (in representing local and regional interests, participating in policymaking, evaluating policies, etc.) one could see here not only issues of representativeness, but also a problematic mismatch of accountability, given that a portion of the constituency of the networks in question lies outside the borders of the EU. At the same time, the presence of non-EU-based members in networks can also be a source of fresh ideas and out-of-the-box policy thinking, both for EU-based network members and for EU institutions, notably the European Commission.

Networks that reach beyond the EU can, finally, be channels for the diffusion of certain ideas and practices promoted by the Union beyond its borders, either directly, via interactions between EU institutions and non-EU sub-national governments, or indirectly, to the extent that networks are carriers of sub-national Europeanisation. This function is all the more valuable when it provides a backdoor through which to counter the limits or deterioration of traditional diplomatic relations between the EU and outside actors.

We argue that there are three instances in which transnational networking beyond EU borders can be especially helpful. First, networks can (indirectly) help prospective EU members prepare for accession. This was, for instance, the role played by some Euroregions bridging the EU and post-communist Europe in the 1990s (Pasi Citation2007). Kristine Kern and Tina Löffelsend (Citation2008), for example, have shown how a number of transnational structures of governance, among which the Union of the Baltic Cities, played a role in promoting the Europeanisation of their post-communist members in the field of environmental policy, and in strengthening their links with Brussels, well before the 2004 enlargement.

Second, networks can help establish and maintain productive transnational relations with those countries – above all in the EU’s neighbourhood – in which the practice of liberal democracy is currently wanting. Anstassia Obydenkova (Citation2005), for instance, has documented how transnational cooperation between European and Russian regions has solidified processes of sub-national democratisation in the latter. Anne Pintsch (Citation2020) has explored the growing connections between the EU and newly decentralised Ukraine via community twinning and transnational municipal networks as vehicles for the societal Europeanisation of Ukraine and, more generally, increasing legitimacy of the country’s European agenda. In this respect, sub-national authority organisations can reproduce, on a larger scale, one of the historical functions of town twinning: to promote linkages and engagement beyond international rivalries.

Finally, networks have a role to play in post-Brexit Europe, as a tool to foster transnational communications between the EU and the UK – whose sub-national governments participate in 48 of the networks surveyed here – and perhaps help mitigate some of the political and policy rifts that have already begun to emerge between the two sides.

Conclusion

This article has presented a systematic analysis of sub-national authority networks in the EU from the hitherto unexplored perspective of institutional differentiation. Building on an original dataset and interviews with network practitioners, we have identified and discussed three main dimensions of differentiation generated by networks: insider-outsider, compound and multi-level differentiation. For each, we have highlighted some of the main advantages and drawbacks, primarily in terms of the effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy of networks’ actions.

A key objective of this exploratory study is to encourage scholars of differentiation to look beyond the state as the primary unit of analysis as they examine this important topic. In this respect, this article is aligned with recent theoretical analyses of differentiation, which have argued for an expansion of this concept beyond its traditional ‘comfort zone’ (for example, Fossum Citation2019; Lavenex and Križić Citation2019). Despite the fact that some recent developments in European integration – such as the intoduction of the Next Generation EU package as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic – have marked a return to a more traditional and uniform mode of integration, there is little doubt that differentiation will remain an important feature of Europan integration for the foreseeable future (Leruth and Lord Citation2015; Pirozzi and Tortola Citation2016; Schimmelfennig Citation2018). As theoretical and empirical work on differentiation advances, looking at the sub-national level will contribute significantly to a full understanding of the nature and implications of this phenomenon.

The foregoing analysis has highlighted a number of aspects of sub-national differentiation on which future research could build. In concluding the article, we want to mention three such areas that connect the study of sub-national networks more directly to European integration, and therefore might resonate more immediately with DI scholars. The first is empirical in nature: as noted above, one of the shortcomings of the existing scholarship on sub-national networks is the lack of comprehensive and easily accessible data on these organisations. Future research should concentrate first and foremost on filling this gap, by collecting and classifying reliable information on networks, in Europe and beyond. To be sure, this is a tall order: the characteristics of this institutional form make the collection of truly exhaustive data rather elusive. The world of networks is, among other things, constantly evolving and has very fuzzy borders due to its great diversity. Even so, the room for improving on the status quo is significant, and the potential payoffs of such work enormous. Above all, better data on networks would help clarify the map of institutional asymmetries at different levels, thus contributing to the still too tenuous links between differentiation research and the multi-level governance research programme (Hooghe and Marks Citation2003; Tortola Citation2017).

Second, and connected to the foregoing, future research should look into the role(s) of sub-national networks within the policymaking cycles of the EU. As mentioned in the previous pages, sub-national organisations can and do play a number of functions on both the input and output side of EU policymaking, such as lobbying on behalf of their members, promoting policy ideas, channelling local-level Europeanisation and, more tangibly, complementing the Union’s infrastructural capacity (for example, in their role as implementers of EU-funded projects). In this context, the focus should be particularly on the asymmetries generated by the network landscape, and their effects on policymaking dynamics and outcomes. Research themes include, for example, the impact of network characteristics (for instance, size and country coverage) on their ability to bring policy ideas at the EU level; the effects of internal and external multi-level differentiation on patterns of Europeanisation; finally, the role and advantages of ‘super-insider’ local governments as nodes in multi-level policy networks.

Third, networks research should be conducted in connection with the main normative issues engendered by differentiation and differentiated integration. Among these are the key questions of: a) policy effectiveness, emerging especially when interconnected policy areas are tackled by institutions with different territorial scope; and b) democracy and accountability issues arising from the mismatch between the direct or indirect electoral constituencies of EU institutions (in the first place, the European Parliament) and the territorial applicability of their decisions (Pirozzi et al. Citation2017). For each of these issues, research should investigate the conditions in which networks, and their institutional asymmetries, mitigate normative problems – for instance, by providing alternative, albeit imperfect, channels for the representation of societal interests, or for softening policy discrepancies between insiders and outsiders of differentiated integration arrangements – or, on the contrary, exacerbate them, such as in the case of the accountability issues created by external multi-level differentiation. In either case, research on networks has the potential not only to further unpack the key normative aspects of differentiation, but also to attach more fine-grained empirical evidence to them.

Online Appendix. Data collection procedures

Download MS Word (25.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jelmer Herms and Niklas Abel for research assistance, and Tiziana Caponio, Sandra Lavenex, Antonio Magnano and two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

This article, as well as the Special Issue in which it is included, is one of the outputs of research conducted in the framework of the EU IDEA research project – Integration and Differentiation for Effectiveness and Accountability – which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 822622. This article, and the Special Issue as a whole, reflect only the views of the authors, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pier Domenico Tortola

Pier Domenico Tortola is Assistant Professor of European Politics and Society at the University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

Stefan Couperus

Stefan Couperus is Associate Professor of European Politics and Society at the University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected]; Twitter: @stefancouperus

Notes

1 For clarity, in this article we use ‘differentiated integration’ to indicate asymmetric configurations of EU membership (Stubb Citation1996). Differentiated integration so defined is a subset of the broader phenomenon of differentiation.

2 Throughout the article, we will use the term ‘region’ generically, to indicate any sub-national unit of government larger than a town or a city – hence not only regions properly named, but also provinces, Länder etc.

3 All interviews were conducted with informed consent of the interviewees.

4 To the authors’ knowledge, the only existing comprehensive and publicly accessible database of sub-national authority networks is included in the Yearbook of International Organizations maintained by the Union of International Associations (https://uia.org/ybio), which collects information on over 70,000 inter- and transnational organisations. However, the absence of a specific category for sub-national authority networks in the database hinders the extraction of data for our purposes.

5 For the purposes of our dataset, which was collected before the official Brexit date, the United Kingdom is considered part of the EU.

6 These figures exclude non-territorial members of networks, such as non-governmental organisations, foundations, universities and the likes. For networks with different layers of participation, only full members are counted. Finally, in line with Marco Keiner and Arley Kim (Citation2007), we exclude members that are themselves sub-national authority organisations, so as to emphasise the direct and voluntary character of network participation.

7 This is not to deny the presence of some overlaps among state-based institutions, especially as we expand the focus beyond the EU: take, for instance, the overlaps between the European Union and NATO or between the EU and the Council of Europe in the areas of defence, and democracy and human rights, respectively. But while for states the presence of multiple cooperative arrangements in the same field is an exception, for sub-national governments it seems to be the rule.

8 For simplicity, in defining multi-level differentiation, we are leaving aside EU policy initiatives and institutions in which non-EU countries participate, such as the Single Market and the Schengen area. However, the logic of internal and external multi-level differentiation can be extended to these cases. For instance, a sub-national authority network including Norwegian members would generate external multi-level differentiation if it operates in the area of, say, regional policy, but not if it works in the area of the Single Market, of which Norway is a member.

References

- Acuto, Michele. 2013. Global Cities, Governance and Diplomacy. The Urban Link. London-New York: Routledge.

- Acuto, Michele, and Leffel, Benjamin. 2020. Understanding the Global Ecosystem of City Networks. Urban Studies, 7 July. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020929261.

- Andersen, Svein S., and Sitter, Nick. 2006. Differentiated Integration: What Is It and How Much Can the EU Accommodate? Journal of European Integration 28 (4): 313–30.

- Bansard, Jennifer S., Pattberg, Philipp H., and Widerberg, Oscar. 2017. Cities to the Rescue? Assessing the Performance of Transnational Municipal Networks in Global Climate Governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 17 (2): 229–46.

- Barber, Stephen. 1997. International, Local and Regional Government Alliances. Public Money & Management 17 (4): 19–23.

- Brenner, Neil. 2004. New State Spaces. Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bulkeley, Harriet et al. 2003. Environmental Governance and Transnational Municipal Networks in Europe. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 5 (3): 235–54.

- Burch, Sarah et al. 2018. Governing Urban Sustainability Transformations: The New Politics of Collaboration and Contestation. In Thomas Elmqvist et al., eds. Urban Planet: Knowledge towards Sustainable Cities: 303–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Callanan, Mark, and Tatham, Michaël. 2014. Territorial Interest Representation in the European Union: Actors, Objectives and Strategies. Journal of European Public Policy 21 (2): 188–210.

- Capello, Roberta. 2000. The City Network Paradigm: Measuring Urban Network Externalities. Urban Studies 37 (11): 1925–45.

- Couperus, Stefan. 2011. In Between ‘Vague Theory’ and ‘Sound Practical Lines’: Transnational Municipalism in Interwar Europe. In Daniel Laqua, ed. Internationalism Reconfigured: Transnational Ideas and Movements Between the World Wars: 67–89. London: Bloomsbury.

- Couperus, Stefan, and Vrhoci, Dora. 2019. A Profitable Friendship, Still? Town Twinning Between Eastern and Western European Cities before and after 1989. In Eleni Braat and Pepijn Corduwener, eds. 1989 and the West. Western Europe Since the End of the Cold War: 143–60. London-New York: Routledge.

- Davidson, Kathryn et al. 2019. Reconfiguring Urban Governance in an Age of Rising City Networks: A Research Agenda. Urban Studies 56 (16): 3540–55.

- De Sousa, Luís. 2013. Understanding European Cross-Border Cooperation: A Framework for Analysis. Journal of European Integration 35 (6): 669–87.

- Ewen, Shane, and Hebbert, Michael. 2007. European Cities in a Networked World during the Long 20th Century. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (3): 327–40.

- Fossum, John Erik. 2019. Europe’s Triangular Challenge: Differentiation, Dominance and Democracy. EU3D Research Paper no. 1. Oslo: ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo. https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=239073082082023004106064098018074099032048032049061056117002090127002100010002001112024061044008020011060006079005098099028065024091023050060018066064015121079068064071061085091106069069071026073114012117104069070031118122001015007094000001024124105092&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE.

- Haas, Ernst B. 1958. The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces 1950-1957. London: Stevens.

- Heinelt, Hubert, and Niederhafner, Stefan. 2008. Cities and Organized Interest Intermediation in the EU Multi-Level System. European Urban and Regional Studies 15 (2): 173–87.

- Hietala, Marjatta. 1987. Services and Urbanization at the Turn of the Century. The Diffusion of Innovations. Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura.

- Hooghe, Liesbet. 1995. Subnational Mobilisation in the European Union. West European Politics 18 (3): 175–98.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Marks, Gary. 2003. Unraveling the Central State, but How? Types of Multi-Level Governance. American Political Science Review 97 (2): 233–43.

- Huggins, Christopher. 2018a. Subnational Government and Transnational Networking: The Rationalist Logic of Local Level Europeanization. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (6): 1263–82.

- Huggins, Christopher. 2018b. Subnational Transnational Networking and the Continuing Process of Local-Level Europeanization. European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (2): 206–27.

- Interview 1. 2020. Author’s interview with sub-national authority network officer (online interview). 6 July.

- Interview 2. 2020. Author’s interview with sub-national authority network officer (online interview). 6 July.

- Interview 3. 2020. Author’s interview with sub-national authority network officer (online interview). 8 July.

- Interview 4. 2020. Author’s interview with three sub-national authority network officers (joint online interview). 14 July.

- Interview 5. 2020. Author’s interview with sub-national authority network president (online interview). 31 August.

- Interview 6. 2020. Author’s interview withs sub-national authority network officer (online interview). 11 September.

- Keating, Michael. 1999. Regions and International Affairs: Motives, Opportunities and Strategies. Regional and Federal Studies 9 (1): 1–16.

- Keiner, Marco, and Kim, Arley. 2007. Transnational City Networks for Sustainability. European Planning Studies 15 (10): 1369–95.

- Kern, Kristine and Bulkeley, Harriet. 2009. Cities, Europeanization and Multi-Level Governance: Governing Climate Change through Transnational Municipal Networks. Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (2): 309–32.

- Kern, Kristine, and Löffelsend, Tina. 2008. Governance beyond the Nation State: Transnationalization and Europeanization of the Baltic Sea Region. In Marko Joas, Detlef Jahn and Kristine Kern, eds. Governing a Common Sea. Environmental Policies in the Baltic Sea Region: 115–41. London: Erthscan.

- Kuznetsov, Alexander. 2015. Theory and Practice of Paradiplomacy. Subnational Governments in International Affairs. London/New York: Routledge.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Križić, Ivo. 2019. Conceptualising Differentiated Integration: Governance, Effectiveness and Legitimacy. EU IDEA Research paper No. 2. https://euidea.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/euidea_rp_2.pdf.

- Le Galès, Patrick. 2002. European Cities. Social Conflicts and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leitner, Helga. 2004. The Politics of Scale and Networks of Spatial Connectivity: Transnational Interurban Networks and the Rescaling of Political Governance in Europe. In Eric Sheppard, and Robert B. McMaster, eds. Scale and Geographic Inquiry. Nature, Society, and Method: 236-55. Malden/Oxford: Blackwell.

- Leruth, Benjamin, and Lord, Christopher. 2015. Differentiated Integration in the European Union: A Concept, a Process, a System or a Theory? Journal of European Public Policy 22 (6): 754–63.

- Leuffen, Dirk, Rittberger, Berthold, and Schimmelfennig, Frank. 2013. Differentiated Integration: Explaining Variation in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mocca, Elisabetta. 2018. “All Cities Are Equal, But Some Are More Equal Than Others”. Policy Mobility and Asymmetric Relations in Inter-Urban Networks for Sustainability. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 10 (2): 139–53.

- Murphy, Alexander. 1993. Emerging Regional Linkages within the European Community: Challenging the Dominance of the State. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 84 (2): 103–18.

- Niederhafner, Stefan. 2013. Comparing Functions of Transnational City Networks in Europe and Asia. Asia Europe Journal 11 (4): 377–96.

- Obydenkova, Anstassia. 2005. Europeanization, Democratization, and Regionalization: The Role of Transnational Regional Cooperation in the Regime Transition in Regions. Working Paper. Florence: EUI. https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/3913.

- Pasi, Paolo. 2007. Euroregions as Micro-Models of European Integration. In Josef Langer, ed. Euroregions. The Alps-Adriatic Context: 73–9. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Perkmann, Markus. 2007. Policy Entrepreneurship and Multilevel Governance: A Comparative Study of European Cross-Border Regions. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (6): 861–79.

- Pintsch, Anne. 2020. Decentralization in Ukraine and Bottom-Up European Integration. In Hanna Shelest, and Maryna Rabinovych, eds. Decentralization, Regional Diversity, and Conflict. The Case of Ukraine: 339-63. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pirozzi, Nicoletta, and Tortola, Pier Domenico. 2016. Negotiating the European Union’s Dilemmas: Proposals on Governing Europe. IAI Working Papers. Rome IAI. https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/iaiwp1624.pdf.

- Pirozzi, Nicoletta, Tortola, Pier Domenico, and Vai, Lorenzo. 2017. Differentiated Integration: A Way Forward for Europe. Rome: IAI.

- Rapoport, Elizabeth, Acuto, Michele, and Grcheva, Leonora. 2019. Leading Cities. A Global Review of City Leadership. London: UCL Press.

- Sassen, Saskia. 2001. The Global City. New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Saunier, Pierre-Yves, and Ewen, Shane, eds. 2008. Another Global City. Historical Explorations into the Transnational Municipal Moment, 1850–2000. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

- Schimmelfennig, Frank. 2018. Brexit: Differentiated Disintegration in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (8): 1154–73.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Winzen, Thoms. 2020. Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmitter, Philippe C. 1969. Three Neo-Functional Hypotheses about International Integration. International Organization 23 (1): 161–6.

- Stubb, Alexander. 1996. A Categorization of Differentiated Integration. Journal of Common Market Studies 34 (2): 283–95.

- Tavares, Rodrigo. 2016. Paradiplomacy. Cities and States as Global Players. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, Peter J. 2005. New Political Geographies: Global Civil Society and Global Governance through World City Networks. Political Geography 24 (6): 703–30.

- Tortola, Pier Domenico. 2012. Federalism, the State and the City: Explaining Urban Policy Institutions in the United States and in the European Union. PhD diss., University of Oxford. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c7fc59b8-474d-45db-b5ae-e1c95f2e44fc.

- Tortola, Pier Domenico. 2013. Federalism, the State and the City: Explaining ‘City Welfare’ in the United States and the European Union. Publius: The Journal of Federalism 43 (4): 648–75.

- Tortola, Pier Domenico. 2016. Europeanization in Time: Assessing the Legacy of URBAN in a Mid-size Italian City. European Planning Studies 24 (1): 96–115.

- Tortola, Pier Domenico. 2017. Clarifying Multilevel Governance. European Journal of Political Research 56 (2): 234–50.

- Wolfram, Marc, et al. 2019. Learning in Urban Climate Governance: Concepts, Key Issues and Challenges. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (1): 1–15.