ABSTRACT

In reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Chinese authorities have installed visa restrictions and strict quarantine rules to prevent foreigners from spreading new infections to the country. This has disrupted a trend of increasing European Union (EU)-China travel and socio-economic exchanges. EU citizens living in or travelling to China have had to deal with the consequences of Beijing’s so-called Zero-Covid strategy. In view of quasi-closed borders, many Europeans have given up on living in or travelling to China. Those who have stayed have come up with strategies of adaptation, while European-owned firms have reacted by adopting initiatives such as doing business online or localising staff. Overall, the Chinese visa restrictions have added a new dimension to the debate on asymmetries in EU-China relations.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in early 2020, the European Union (EU) and China developed different approaches on how to deal with the virus. In Europe, the objective has been to bring Covid-19 infections under control through vaccinations and targeted public health measures – yet also to eventually accept it as an endemic. Vaccine rollouts have been considered the turning point to opening up, including to vaccinated travellers from third countries. China, by contrast, has aimed at suppressing Covid-19 infections – including any Covid-19 variant – by imposing lockdowns in the case of local outbreaks as well as strict border controls and quarantine requirements for incoming individuals from outside the country. The pandemic has come to be seen as something exogenous to China. Covid-19 border and travel restrictions have been kept in place while most other countries were moving towards opening up again.

In the first year after the outbreak, the so-called Zero-Covid strategy allowed China to have much fewer victims of the Covid-19 pandemic. By March 2022, China’s excess mortality rate was estimated to be at about 5 per cent of the United States’ (US) (The Economist Citation2022). In a “pandemic power play”, the Chinese Communist Party has sought to showcase its competence, bolster its legitimacy and perpetuate its rule at home (Rolland Citation2020). Thus, Chinese citizens and residents would be able to continue with pre-pandemic lifestyles. From 2020 to early 2022, the Chinese economy expanded by 10.5 per cent, while the average growth rate of advanced economies was only 0.4 per cent (The Economist Citation2022). The strategy, however, has also had major costs and side effects. More contagious Covid-19 variants have made the containment difficult and costly from an economic perspective, requiring an increasing number of (local) lockdowns to keep infections at bay. Furthermore, shielding China from the rest of the world has had far-reaching implications for those willing to enter or exit the country and subsequently for firms doing business with/in China.

This article analyses this interaction between China and the outside world by focusing on travel patterns and (short-term) visa policies between the EU and China after the initial pandemic outbreak. It elaborates on how EU citizens living in and travelling to China, as well as European-owned firms, have reacted to the Chinese visa restrictions and quarantine rules. The research is informed by a set of interviews with stakeholders living in China or working with Chinese authorities. In total, 17 interviews were conducted between April and September 2021 with visa officials of EU member states, officials of the Chamber of Commerce of the EU and those of its member states in Beijing, representatives of the tourism and airline industries, as well as European businesspeople operating in China.Footnote1 Investigating their experiences and perspectives, the article addresses a research lacuna. Most scholarly work has focused on how EU-China relations evolve, are negotiated or relate to the US-China rivalry (for example, Christiansen et al. [Citation2018]; Finamore [Citation2015]; Casarini [Citation2020]). This article, instead, provides a more bottom-up perspective in terms of elaborating on how EU-China relations have played out for European stakeholders.

The article is structured into three main sections. It first provides an overview of the drivers and constraints of EU-China relations. In the next section, EU-China visa policies and travel patterns pre- and post-pandemic are investigated. The third section is dedicated to how EU nationals and firms have reacted to China’s visa restrictions and quarantine rules. It highlights that many Europeans have given up on living in China in view of quasi-closed borders. Those who could not or did not want to do so – mostly because of family ties or their economic engagement – have come up with strategies of adaptation. Overall, the pandemic has had a profound impact on the expat communities of EU nationals in China, which in turn will likely have an impact on EU-China relations at large.

The EU and China between engagement and confrontation

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1975, first the European Community and then the EU have developed a complex relationship with China. On the one hand, the EU’s institutions and member states have been interested in engaging with China and seizing the (economic) opportunities that its vast internal market offer. On the other hand, there is unease among EU actors about the authoritarianism and assertiveness of the Chinese Communist Party under President Xi Jinping (Breslin and Pan Citation2021). The EU has defined China as a strategic partner but, at the same time, also “a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance” (European Commission and High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Citation2019).

At its heart, the relationship has been dominated by trade and investment, although it has become more multifaceted over the years. As Thomas Christiansen et al. (Citation2019, 182) maintain, “the EU and China are far from being in a cosy relationship, and that this should come as no surprise – each side works from a unique historical experience, different political systems and values, distinct processes of economic and social development, and different geopolitical positions and interests”. A closer engagement of the EU has been driven by economic opportunities. China has become the EU’s largest trading partner, with 16 per cent of the EU’s total trade in 2021. The US came only second with 15 per cent (European Commission Citation2022). Apart from trade, Brussels and Beijing have put forward a range of other shared objectives, including fighting climate change, ensuring international security and stability, as well as global economic growth (see for example European Commission [Citation2017]). The EU and China even worked towards establishing a “strategic partnership”, which is meant to help manage the political, security and environmental challenges of mutual interest. The realisation of this strategic partnership, however, turned out to be an “elusive” objective (Maher Citation2016).

It has become challenging for the EU to develop closer economic and political relations with China while maintaining its normative claim of promoting human rights, democracy and the rule of law worldwide (Mattlin Citation2012). Heightened geopolitical and ideological tensions, notably between China and the US, have brought up thorny questions for Brussels in terms of how to position itself in the Indo-Pacific region (Simon Citation2021). China has increasingly been framed as a “security threat” in EU capitals (Chen and Gao Citation2021), comparable to the debates of the US, Australia and the United Kingdom (McCourt Citation2021). However, there are different voices in the European debate. Some believe that the EU should reduce its reliance on and exposure to China to a minimum (Holslag Citation2017; Citation2019). Other researchers and policymakers have suggested that the EU should avoid being drawn into the US-China power competition and develop an independent approach allowing a continued engagement (Biscop Citation2019). Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, has echoed this line of thinking by putting forward a “Sinatra doctrine” – according to which the EU would deal with geopolitical competition and competitors “in its own way” (Borrell Citation2020). A “European sovereignty” or “strategic autonomy” should ensure the EU’s capacity to act independently and become more resilient in a range of areas, from defence, trade and industrial base to digital policy (Howorth Citation2018; European Parliament Citation2021a).

The EU has struggled to speak with one voice in its relations with China, which has made its quest for autonomy more difficult. EU member states tend to have diverging views on relevant issues, such as the scope of China’s access to the EU’s Single Market or how to position themselves in the face of “conflicting great-power interests” (Do Céu Pinto Arena Citation2022, 1). In effect, EU member states often prioritise their bilateral relations with China, thereby “undermin[ing] Brussels’ capacity to fashion a clear and coherent China policy” (Casarini Citation2015, 122). John Fox and François Godement (Citation2009) categorised the EU member states into four groups, namely “assertive industrialists, ideological free traders, accommodating mercantilists and European followers”. Some Chinese initiatives, notably the “16 + 1” initiative originally set up in 2012 for Central and Eastern Europe, were seen as an attempt to lure a group of EU states closer to China, thereby preventing Brussels from developing an assertive approach (Pepermans Citation2018; for a different view see Zhao [Citation2016]). Indeed, some member states with close ties to China have opposed joint EU measures. Two well-known examples include Hungary’s refusal to sign a joint EU statement criticising the reported torture of detained lawyers in China, and Greece vetoing an EU statement critical of Beijing’s human rights record in 2017 (Chen and Gao Citation2021).

By and large, however, the EU’s approach towards China has moved to a more “defensive if not confrontational” approach over the years (Le Corre Citation2020). This is reflected by the imposition of sanctions on Chinese officials involved in alleged human rights violations and the freezing of the ratification process of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment by the European Parliament in May 2021 (European Parliament Citation2021b). Brussels has also installed a framework for the screening of foreign direct investment into the Union (Regulation 2019/452) – a step primarily targeting Chinese economic actors (Reisman Citation2020). The EU member states had hoped for greater and quicker concessions from China in terms of reciprocating the openness of the EU’s Single Market. However, their efforts have not resulted in the desired outcomes. Certain Chinese decisions, such as the industrial and technological strategy called “Made in China 2025”, seemed to “be designed to make an already uneven economic playing field more uneven at a time when Europeans (and others) were asking for greater reciprocity in market access” (Breslin and Pan Citation2021). A “shared sense of economic imbalance, disappointment and unease” (Oertel Citation2020) has emerged among most EU actors.

The Covid-19 pandemic has sharpened these controversies. Several parliaments, such as the Dutch Parliament, have openly debated whether China is to blame and should be held accountable for the pandemic. Furthermore, China’s diplomacy was seen to have gone “into overdrive” with aid, mask deliveries and the promotion of China’s Covid response as a “success story” (European Think-tank Network on China Citation2020, 8). The economic side of this debate has primarily related to the question of whether the pandemic would reinforce “decoupling trends, [thereby] pulling major economies further apart and disrupting commercial flows and other exchanges”, as raised in a report co-authored by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China and MERICS (Citation2021, 3). The report also highlights that growing geopolitical tensions have made China redouble its drive for self-reliance. “European companies in China report that this drive is different and more radical than in the past” (4).

Overall, the EU and China have developed close trade and economic relations. The EU’s policy towards China has arguably remained less adversarial compared to the US’, even though Brussels has increasingly focused on issues such as a fairer level playing field for its firms active in China. This article will highlight that the debate has now moved beyond the economic field, with asymmetrical visa restrictions and quarantine rules adding to calls for a more reciprocal EU policy vis-à-vis China.

EU-Chinese travel patterns and visa policies

The EU-China visa regimes reflect the ambiguous relationship between the two partners. Economic opportunities created a push towards facilitated travel opportunities between China and Europe. At the same time, both sides have become warier of allowing certain (categories of) travellers to come in, even for short time periods.

The dynamics pre-Covid-19

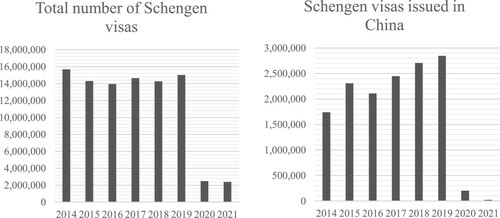

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU saw a continuous rise in short-term visa applications from Chinese citizens and residents. Between 2014 and 2019, the number of Schengen visas issued per year to Chinese applicants increased by 1.1 million (from 1.7 to 2.8 million).Footnote2 The overall number of Schengen visas issued worldwide remained roughly the same, reflecting the growing relevance of the Chinese market and travellers to the EU. This growth was permitted by a range of factors, including a stronger EU presence in China in terms of visa infrastructure. Cheaper airline tickets and the growing financial resources of the Chinese middle class also played a role. With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Schengen visa applications of Chinese nationals dropped from 2.8 million in 2019 to less than 25,000 in 2021 (; see also the next section for a detailed discussion).

Figure 1. Schengen visas issued per year (all third countries and China, 2014-2021)

Source: author’s compilation based on the yearly “Visa statistics for consulates” released by DG Home (Citation2022).

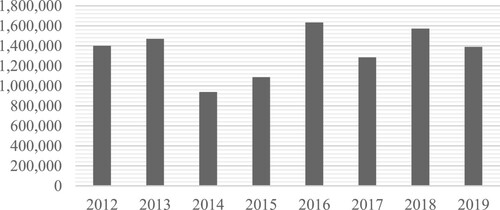

Until the pandemic, short-term travel also increased in the other direction, from the EU to China. The number of (non-resident) tourists who travelled to China increased from around 83 million in 2000 to 162 million in 2019 (Knoema Citation2021). In 2018, EU residents made 1.75 million trips to China, which corresponds to the 11th most popular destination outside of the EU (Eurostat Citation2020). The number of yearly trips by EU residents to China (pre-Covid-19) fluctuated but was slightly on the rise until 2019 (). Most EU residents left for professional purposes (48 per cent), with tourism (35 per cent) and visiting friends and relatives (15 per cent) coming next (Eurostat Citation2020).

Figure 2. Trips by EU residents to China (2012-2019).

Source: author's compilation based on Eurostat (Citation2022).

In view of the increasing volumes of visa applications pre-Covid-19, Brussels and Beijing sought to deepen their cooperation and facilitate short-term travelling. At the 17th EU-China Summit in June 2015, the two sides envisaged a range of measures to move towards easier visa regimes. In the first phase, diplomats benefitted from a reciprocal visa waiver agreement, and the EU was allowed to expand its visa application centres up to 15 Chinese cities (European Commission Citation2015). In the second phase, the EU and China planned to negotiate in parallel an “agreement on visa facilitation and an agreement on cooperation in combating illegal migration” (EU-China Summit Citation2018, 7). This linkage between visa facilitation and readmission is standard for the EU when it engages with third countries (Trauner and Kruse Citation2008). Overall, expat communities, business actors, as well as EU and Chinese officials, were hopeful that short-term travel between the two sides would become smoother and continue to grow.

However, already pre-Covid-19-pandemic, the two visa regimes were not spared from a certain politicisation that had come to characterise EU-Chinese relations at large. The 2019 Annual Report of the “Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China” already highlighted that the work of foreign journalists was becoming more difficult in terms of entering and staying in the country. Chinese authorities would use “visas as weapons against the foreign press like never before”. Visa bans, their non-renewal and the expulsion of journalists were applied more frequently (FCCC Citation2019). Also, a number of EU officials and businesspeople have been increasingly concerned about privacy and data security given the growing amount of information required in the Chinese Visa Application Form.Footnote3 Revised in 2019, the length of the Chinese form increased from four to eight pages, now asking for more and more detailed information than the EU’s.

Politicisation has also taken place in the other direction of travel. For example, Chinese students have faced more thorough application procedures when asking for an invitation letter from a university in the EU. Whereas EU-based professors and institutes formerly may have signed these letters themselves, they now have more frequently to pass through the rectorates in order to verify that the invited students or researchers would not come from a university seen to be associated with a Chinese ministry engaged in surveillance or defence activities.Footnote4

While still being the exception, travel bans and visa restrictions have also been employed in high-level political controversies. In March 2021, the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that it would sanction ten EU individuals and four EU entities by prohibiting them from getting a visa and entering the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Macao, as well as doing business with China (MFA of the People’s Republic of China Citation2021). The sanctioned individuals included senior politicians such as Reinhard Bütikofer, Member of the European Parliament (MEP) and Chair of the European Parliament’s (EP) delegation for relations with China.Footnote5 The ban came in response to the EU’s decision to sanction four Chinese officials and one entity considered to be involved in alleged human rights violations of the Uyghur Muslim minority in the Xinjiang autonomous region (Euronews Citation2021).

Visa restrictions and quarantine rules during the Covid-19 pandemic

After the outbreak of the pandemic, China has quickly developed its Zero-Covid strategy. A key objective has been to ensure that no new infections would be introduced from abroad. On 28 March 2020, China suspended travel for EU and other third-country nationals, even those with a valid visa.Footnote6 Several types of visas, notably for European tourists, have not been issued since. However, at different stages of the pandemic, Chinese authorities relaxed entry restrictions for specific groups of foreigners: for example, those with a valid residence permit.Footnote7 In March 2021, Beijing also declared that people vaccinated with a Covid-19 vaccine produced in the People’s Republic could face lower requirements when applying for a visa to China. This, however, has been of limited relevance for the EU. Apart from Hungary, indeed, Chinese vaccines have not been used in the vaccination campaigns of EU member states.Footnote8

In practice, during the Covid-19 pandemic, EU nationals have been able to enter China primarily in two ways: an emergency humanitarian need or if in possession of an additional Chinese welcome letter (called the PU letter) issued by a relevant Foreign Affairs Office (Chengdu-Expat.com Citation202Citation1). This letter has opened the way to a Chinese visa procedure, yet only companies have been allowed to apply for their senior staff such as managers, technical experts and other high-end talents. As a matter of fact, this measure is not meant to foster short-term travel; it should primarily ensure that foreign-owned firms in China can continue to exist and operate.

As a result of the pandemic, it has not only been that fewer foreigners have had opportunities to come in; Chinese nationals have also had fewer opportunities to leave. The People’s Republic has essentially stopped issuing and renewing Chinese passports. The objective has been to minimise travel to contain the import of Covid variants (Mimi Citation2021a). Those Chinese nationals who still had a valid passport have been encouraged not to use it. President Xi Jinping set the example in this respect. Until September 2022, he did not leave the country after the first lockdown was imposed in Wuhan in January 2020, participating virtually in major international gatherings such as the G20 meeting in Rome and the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in October and November 2021. President Xi’s refusal to travel became an issue of salience in Chinese public debates. Media and blogs counted how many days he stayed inside the country after the first lockdown (see, for example, Bloomberg [Citation2021]). Moreover, as a Beijing-based European official of a chamber of commerce highlighted, not travelling to foreign countries is only one element of a wider picture:

President Xi is not meeting any foreigners. But once a year, he has to meet the foreign ambassadors. At this occasion, these ambassadors have to keep a distance of five meters; they have to wear a mask and have to go in quarantine before this meeting – and still, five meters distance. This all highlights that the President is sending out a signal – I do not want to see you, I do not want to interact with you. If necessary, then only online.Footnote9

Compared with China, the EU has remained more open to third-country nationals, including to Chinese nationals. The EU imposed a travel ban on Chinese nationals only for a short period of time in early 2020. When China started to have low or no new Covid-19 cases, the People’s Republic was included in the list of countries for which EU member states lifted travel restrictions on 30 June 2020 (Council of the EU Citation2020). The EU still asked for Covid-19-related documents such as a negative test result or proof of a vaccination as a precondition for inbound travel. If a country was on the EU’s list of countries with low health risks, however, quarantine requirements could be lifted. China remained the only country of the EU’s list with the qualification “subject to confirmation of reciprocity” (European Commission Citation2021b), implying that Beijing should lift its entry restrictions on EU travellers as well. This has not happened; notwithstanding, Chinese travellers have been allowed entrance to several EU member states regardless. In particular, tourist-driven economies, such as Greece, have allowed Chinese travellers to enter again, subject to presenting a negative PCR test or proof of vaccination (including Chinese vaccines, in the Greek case) (Government of Greece Citation2021).

Even if legally permitted, though, few Chinese nationals have come for short-term travel to the EU during the pandemic. Only about 200,000 Chinese nationals travelled to the Schengen area in 2020, the first year of the pandemic. This amount further decreased to a mere 24,183 in 2021. Apart from the fact that travelling has become socially undesirable, Chinese nationals have also been deterred by the long quarantine period that they have to face upon return.Footnote10 China’s quarantine rules have remained much stricter compared with EU quarantine rules throughout the different phases of the pandemic. There have been no exceptions; foreigners (including from the EU) travelling to China and Chinese nationals coming back to the country have been subject to the same quarantine requirements. The Chinese quarantine rules have compelled travellers to stay in ad-hoc hotels for, in most cases, two or three weeks (length may vary in different provinces; Beijing has had the longest quarantine period of three weeks).Footnote11 A company sending a businessperson to China must therefore cover these costs, plus the salary of the employee. An official of an economic chamber of commerce of an EU member state pointed out: “Which EU enterprise can afford to pay this and also block an engineer or a technician for three weeks?”.Footnote12

European adaptation strategies in China

This section looks at the strategies adopted by different actors to deal with Chinese Covid-19 regulations. The first – leaving – is mostly at the level of individuals. The second – going online or localising – concerns primarily firms operating in China. Finally, the strategy of reducing the exposure has been typically applied by airline companies – a sector which strongly benefitted from the tighter socio-economic exchanges prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Individuals: leaving China

In the EU expat community, notably among EU families with children, the perspective of a Chinese border closure caused rushed departures in early 2020.Footnote13 Families were at risk of separation for prolonged periods. This happened, for example, if one parent left with the children while the other had to stay for professional reasons (primarily due to concerns of not being able to re-enter China). According to an August 2020 survey conducted by EURAXESS China among 99 European researchers based in China, 60 per cent of respondents were already outside the country when border restrictions were introduced. Ninety per cent of the survey participants were not able to return in the following three months, when the survey was organised, given that “exemptions were not being issued by the authorities” (EURAXESS Citation2020).

Not only was it difficult for EU nationals to return to China once they were abroad; many of them did not want to come back due to the risks linked to a positive Covid-19 test during the quarantine procedure, especially for children. Indeed, children faced the possibility of being hospitalised and separated from their parents if they tested positive (Riordan Citation2022a). The same could happen to couples. EU nationals were also concerned about the collective medical observation procedure in case of Covid-19 infection and the lack of freedom in terms of choosing a quarantine place.Footnote14

The effects of (quasi-)closed borders became visible in other areas too, notably the education of EU or binational children in China. Non-Chinese teachers of English and other subjects have been increasingly difficult to attract and find. As an EU businessperson highlights, “this is a determining issue if you cannot educate your children” in their parents’ mother tongue.Footnote15

As a result of these challenges, EU expat communities in China have considerably shrunk since the outbreak of the pandemic. Between 40 and 50 per cent of all EU expats are estimated to have left China in the first year of the pandemic.Footnote16 Even Hong Kong, an international centre of commerce, lost at least 10 per cent of EU residents in the first one-and-a-half years of the pandemic (Riordan Citation2022a). According to the President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, in 2020, there were more foreigners in Luxembourg than in Beijing and Shanghai combined (quoted in Wu Citation2021).

The exodus of EU and other foreign nationals has triggered a discussion on whether China has been “turning inward” (The Economist Citation2021). Most interviewees for this research project assumed in mid-2021 that China’s (de-facto) closure to foreign nationals would last for a longer period. According to a European official of a chamber of commerce, the “top level of Chinese authorities seemed to be pleased that fewer and fewer foreigners are in China”.Footnote17 There was a widespread perception that “China wants foreign know-how and respect, [but] not foreigners” (The Economist Citation2021).

Firms: going online and/or localising

EU expats and EU-owned firms in China have operated in a context of uncertainty as to how long the temporary measures introduced to counter the Covid-19 pandemic will remain in place: “It looks as if it will take a long time to bring in people again, notably people that are not celebrities or CEOs – such as normal employees or even interns. Interns are crucial for many enterprises”.Footnote18 According to an April 2021 survey of the German Chamber of Commerce in China (Citation2021), 78 per cent of respondents named easing travel restrictions as the key priority to be addressed to promote foreign investment and attract staff (29 percentage points ahead of ensuring a level playing field between EU and Chinese companies).

The exodus of EU nationals from China, as well as the difficulties in bringing in new employees, have left many EU companies with hard choices. The first – and obvious – response has been to seek to maintain the existing staff in the country and transition to an online solution whenever possible. As an official of a chamber of commerce of an EU member state noted, “for many exports, we do not need to be in China physically. […] We are discovering that you may not need to know the other person so much. If you want to do business in China, show the product and send the money. That’s all”.Footnote19

The digitalisation processes of EU firms were actively supported by different chambers of commerce, which established online platforms and livestreams to enhance their visibility. A case in point was the “Discover Germany Live Stream”, which aimed at promoting German products and brands and had one million viewers in the first two years of the pandemic (German Chamber of Commerce in China Citation2022a, 59).

If online solutions were not possible, many EU-owned companies had little choice but to replace EU employees with Chinese nationals.Footnote20 The ‘localisation’ of staff had already begun before the pandemic, driven by factors such as decoupling, changing consumer behaviour and regulatory requirements (namely, to partner with Chinese actors) (EU Chamber of Commerce in China and Mercis Citation2021). Yet the Covid-19 pandemic has substantially reinforced this dynamic. According to a survey among German companies, the “ongoing travel restrictions are also accelerating localization. Around a third (33 per cent) of German companies are localizing technical and operational know-how in China” (German Chamber of Commerce in China Citation2022b). Interviewed EU stakeholders believe that Chinese authorities have seen opportunities in this development, notably to increase the Chinese impact on foreign-owned firms.Footnote21 Most EU-owned companies have accepted a growing Chinese influence to be allowed to operate in the country and to benefit from economic opportunities in China.

China’s economic rebound after the outbreak of the pandemic was quicker compared with other advanced economies. In the 2021 Business Confidence Survey of the European Chamber of Commerce, 42 per cent of European companies reported that they grew in the first year after the pandemic, while only 25 per cent saw their revenues decline. Furthermore, commitment to the Chinese market remained high. Only 9 per cent of the respondents indicated that they were planning to leave China (EU Chamber of Commerce in China Citation2021). However, the economic outlook deteriorated in late 2021-early 2022, when the Omicron variant made Chinese authorities impose lockdowns on economic hubs such as Shanghai, Xi’an and Shenzhen (Hale et al. Citation2022b).

If online and localised solutions were not possible, there was a third option for EU businesspeople: searching for loopholes. The strategies of (financially affluent) EU-owned companies for getting through the Chinese travel restrictions have been creative at times. Chinese authorities permitted primarily senior staff or specialised technicians to come to and work in China. However, these specialists would often refrain from coming if their families were not allowed to follow them. An official recounted how an EU-owned enterprise searched for loopholes in the Chinese border measures to bring in family members too. It turned out that family members were allowed entrance more easily from Germany compared with, say, India and the US:

We flew the family members from the US and India to Frankfurt where they now stay for six months. After six months, they are entitled to get a Chinese visa in Berlin so they can join their husbands and wives already working in China. […] You can imagine what this implies for the children. This is very disruptive. But there is no other way. […] We have a billion-dollar project in Guangdong. We needed these expats.Footnote22

Airlines: downsizing the exposure

No other business sector has been more affected by visa and travel restrictions than airline companies, whose daily business is to organise travel within and across countries. The example of EU airline companies highlights a strategy of downsizing the exposure while seeking to stay afloat in the Chinese market.

The number of international flights to and from China has become limited after the outbreak of the pandemic. Most foreign airlines flying to China have run at 10 per cent or less of their pre-pandemic capacity (The Economist Citation2021). For instance, one of the biggest European airline companies reduced its number of flights to China from 46 per week to 3 per week after the outbreak of the pandemic.Footnote23 Still, airline companies hoped to return to the growth trend of the pre-pandemic period, thereby accepting additional costs during the pandemic.

Indeed, airline companies have had to bear extraordinary expenditures to be allowed to fly to China. A case in point has been the handling of transit passengers. While China allowed only passengers on direct flights during the earlier phases of the pandemic, transit flights eventually resumed. However, transit passengers are asked to take a new PCR or IgM antibody test in the EU airport in which they change aircraft. European airlines have, hence, installed testing centres in transit areas and re-scheduled their flights to China in such a way that the test results arrive in time for departure.Footnote24

Another challenge for airlines has been that they are subject to punitive measures if they transport passengers with Covid-19. In June 2020, Chinese authorities decided that they would sanction airlines by cancelling inbound flights to China (or limiting their landing permits) over variable periods, depending on the number of passengers positive for Covid-19 upon arrival in China or during quarantine.Footnote25 A basic rule has been that an (EU) airline would be subject to a travel ban of two weeks if it carries three times in a row more than five passengers who test positive for Covid-19 during the quarantine period following the flight.Footnote26 EU airlines are informed of the number of positive cases on their flights – yet they do not receive the names of the passengers involved or can see test certificates.Footnote27 This policy has been considered to lack transparency and has created particular tensions with France, which has been one of the few member states to respond with reciprocity by sanctioning flights of Chinese airlines flying to France.Footnote28

Different interviewees suggested that the “Commission may talk with the Chinese on how to make a transparent and uniform travel policy”Footnote29 or even that the “Commission gets tougher” in its response to such punitive measures.Footnote30 The challenge would be, however, that “the Chinese [do] not care in any case”Footnote31 given the political importance that the Chinese leadership has attributed to the Zero-Covid strategy during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Pre-pandemic, the EU and China saw growing numbers of nationals travelling between them. In 2015, Brussels and Beijing worked on introducing facilitated visa procedures to maintain the growth trend in Schengen and Chinese visa applications. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a disruption in this process. China’s Zero-Covid strategy has aimed at eliminating infections in the country – and not importing new infections from abroad. The Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths to achieve this objective and introduced stricter visa procedures (notably through the PU letter) as well as a long quarantine period upon arrival.

This article has embedded the pandemic restrictions in a longer-term perspective of EU-China short-term visa travel and investigated how EU nationals and actors have reacted to them. While tourism has been banned due to Chinese regulations, EU nationals living in or seeking to travel to China for professional or family reasons have often been left with hard choices. Many have decided to leave China, with roughly half of all Europeans living in China exiting the country within the first year of the pandemic. European families with children were especially concerned about the side effects of quasi-closed borders, such as difficulties in having access to international education due to a lack of foreign teachers. The EU nationals who stayed in China for professional or private reasons have adapted. As far as EU-owned firms doing business in China are concerned, they have often sought to ‘go online’, whenever possible, or to localise by hiring Chinese staff. Those depending on cross-border travel (such as airline companies) have sought to get through the pandemic with reduced capacity and exposure.

EU officials and business actors interviewed for this research perceived an inequality in terms of travel opportunities. Travel and visa restrictions have been substantially tougher on the Chinese than on the European side. An official of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China described the situation in mid-2021 as follows: “it is extreme what happens now: if people arrive in China, they have to be three weeks in quarantine. If Chinese nationals fly to Frankfurt or Vienna, they can immediately leave the airport and go home or wherever they want”.Footnote32 It needs to be mentioned, however, that few Chinese nationals have taken up these travel opportunities to the EU. The strict quarantine upon return to China, limited renewals of expired Chinese passports and social stigmatisation of travelling as undesirable have contributed to very low volumes of visa applications. It is likely that Chinese tourism to the EU – and Europeans travelling to China – will not bounce back quickly (if ever) to pre-pandemic levels.

What does this mean for EU-China relations at large? A note of caution is certainly required. Visa and travel rules are only one element of the political, economic and diplomatic relations between the EU and China. Also, it may be too soon to determine whether the pandemic has been a real turning point or just a bump on the road from which EU-China relations can recover. China may well end up lifting its visa restrictions sooner or later. Still, the travel restrictions imposed in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic are likely to have long(er)-lasting effects. Lower numbers of Europeans living in or travelling to China (and vice versa) imply that transnational expertise decreases and networks loosen. This will have a negative effect on business and policy links, research communities and student exchanges (see also Czajka and Neumayer [Citation2017]). Furthermore, Beijing’s response to the pandemic has reinforced a perception that the EU-China relationship has become asymmetrical. Such a perception is not entirely new in EU political and economic circles, yet it had hitherto concerned primarily trade and economic issues. China’s establishment of a ‘great Covid paper wall’ against the outside world during the pandemic has enlarged this debate to questions of travel, visa applications and people-to-people exchanges.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Stephan Klose, Luis Simon, the four reviewers and the editors of The International Spectator for constructive comments on earlier versions of this article. The research assistance of Gabriele Valodskaite and Sinclare C. Smith is gratefully acknowledged.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Florian Trauner

Florian Trauner holds a Jean Monnet Chair at the Brussels School of Governance of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium.

Notes

1 Due to Covid-19-related travel restrictions, the interviews were conducted online via Teams or Zoom with informed consent. They were based on a semi-structured questionnaire and conducted in English.

2 The Schengen visa provides the right to enter and travel for a period of three months in the Schengen area, comprising 26 EU member states and associate Schengen states.

3 Author’s interview with European Commission official, 11 June 2021; author’s interview with EU businessperson in China 1, 2 June 2021.

4 Author’s interview with International relations officer of European university 1, 4 June 2021.

5 Four other MEPs were also targeted, alongside politicians of EU member states, scholars and entities such as the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Germany, the largest China-dedicated think tank in Europe.

6 It allowed for very narrow exceptions, such as individuals indispensable for economic, trade, scientific or technological activities or those having to travel for emergency humanitarian needs: see Li (Citation2021).

7 Individuals with a valid residence permit for work, personal matters or family reunion could be allowed to enter China (without applying for a visa). If such a permit was no longer valid, a renewal could be requested. All other measures of the first phase remained in force, see Li (Citation2021).

8 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

9 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 1, 17 September 2021.

10 Furthermore, many Chinese (and Asian-looking) people were subject to stigmatisation and prejudice in the EU during the Covid-19 pandemic (see Roberto et al. Citation2020), which may also have contributed to reduced Chinese visa applications.

11 These hotels typically costed between EUR 60 and EUR 100 a night. Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

12 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

13 Given that many EU nationals who left the country in 2020 have not been not able to get a new Chinese visa thereafter, there are still European families having property and personal affairs in China but with no access to them: see author’s interview with EU businessperson in China 2, 16 June 2021.

14 Author’s interviews with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 2 and 3; EU businessperson in China 2 (June 2021)

15 Author’s interview with EU businessperson in China 1, 2 June 2021.

16 Author’s interview with Official of EU economic chamber 1, 14 June 2021.

17 Author’s interview with Official of EU economic chamber 1, 14 June 2021.

18 Author’s interview with an EU businessperson in China 1, 2 June 2021.

19 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 1, 17 September 2021.

20 Author’s interview with an Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

21 From the perspective of EU officials, however, this approach has been short-sighted. Replacing Europeans with Chinese may be seen to create short-term benefits for the Chinese, but it will have a negative long-term impact. If there are only loose or less personal ties between a Chinese branch and a European headquarters, investment decisions are likely to get harder or be negatively affected; see author’s interviews with EU businessperson in China 1, 2 June 2021; Official of economic chamber of EU member state 1, 14 June 2021; Official of economic chamber of EU member state 2, 15 June 2021.

22 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 1, 14 June 2021.

23 Author’s interviews with Employees of two different European airline companies, 16 August 2021.

24 Author’s interview with Manager international affairs of a European airline company, 16 August 2021.

25 A case in point was Air France’s Paris-Tianjin flight. After Covid-19 cases were detected among passengers, the Chinese aviation authority reduced the rate of usual flights on the route to 40 per cent for four weeks from 7 June 2021. The same restrictions were also imposed on flights from Paris to Shanghai. The French government responded by reimposing similar restrictions on Chinese airlines flying to France. See Schaeffer (Citation2021).

26 Author’s interview with Employee of European airline company 1, 16 August 2021.

27 Author’s interview with Employee of European airline company 2, 16 August 2021

28 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

29 Author’s interview with Official of EU Chamber of Commerce 1, 17 September 2021.

30 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

31 Author’s interview with Official of economic chamber of EU member state 3, 18 June 2021.

32 Interview with official of EU Chamber of Commerce 1, 17 September 2021.

References

- Biscop, Sven. 2019. European Strategy in the 21st Century: New Future for Old Power. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bloomberg. 2021. Xi Jinping Hasn’t Set Foot outside China for 600 days. 9 September. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-09/xi-jinping-hasn-t-set-foot-outside-china-for-600-days.

- Borrell, Josep. 2020. The Sinatra Doctrine: How the EU Should Deal with the US-China Competition. IAI Papers 20 (24). Rome: IAI, September. https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/sinatra-doctrine-how-eu-should-deal-us-china-competition.

- Breslin, Shaun, and Pan, Zhongqi. 2021. Introduction: A Xi Change in Policy? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (2): 197-209.

- Casarini, Nicola. 2015. China’s Rebalancing towards Europe. The International Spectator 50 (3): 122-29.

- Casarini, Nicola. 2020. Rising to the Challenge: Europe’s Security Policy in East Asia amid US-China Rivalry. The International Spectator 55 (1): 78-92.

- Chen, Xuechen, and Gao, Xinchuchu. 2021. Analysing the EU’s Collective Securitisation Moves Towards China. Asia Europe Journal. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-021-00640-4.

- Chengdu-Expat.com. 2021. The Ultimate Guide to the PU Invitation Letter. 2021. 1 June. https://chengdu-expat.com/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-pu-letter/.

- Christiansen, Thomas, Kirchner, Emil, and Wissenbach, Uwe. 2019. The European Union and China. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Council of the EU (European Union). 2020. Council Agrees to Start Lifting Travel Restrictions for Residents of Some Third Countries. 30 June. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/06/30/council-agrees-to-start-lifting-travel-restrictions-for-residents-of-some-third-countries/.

- Czajka, Mathias, and Neumayer, Eric. 2017. Visa Restrictions and Economic Globalization. Applied Geography 84: 75–82.

- DG Home. 2022. Statistics on Short-stay Visas Issued by the Schengen States. Accessed 23 September 2022. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/visa-policy_en.

- Do Céu Pinto Arena, Maria. 2022. Portugal’s Challenging Relationship with China under Tense US/EU-China Relations. The International Spectator. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2022.2064059.

- EU Chamber of Commerce in China. 2021. European Business in China. Business Confidence Survey 2021. Beijing, 8 June. https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/publications-archive/917/Business_Confidence_Survey_2021.

- EU Chamber of Commerce in China and MERICS (Mercator Institute for China Studies). 2021. Decoupling. Severed Ties and Patchwork Globalisation. Beijing. https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/Decoupling_EN.pdf.

- EU-China Summit. 2018. Joint Statement of the 20th EU-China Summit. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/36165/final-eu-cn-joint-statement-consolidated-text-with-climate-change-clean-energy-annex.pdf.

- EURAXESS. 2020. EURAXESS China. Quarterly Newsletter Issue 3/2020. https://cdn4.euraxess.org/sites/default/files/2020_euraxess_china_3_quarter-v2.pdf.

- Euronews. 2021. EU Agrees First Sanctions on China in More than 30 Years. 22 March. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2021/03/22/eu-foreign-ministers-to-discuss-sanctions-on-china-and-myanmar.

- European Commission. 2015. Proposal for a Council Decision on the Signing, on Behalf of the European Union, and Provisional Application of the Agreement between the European Union and the People's Republic of China on the Short-stay Visa Waiver for Holders of Diplomatic Passports. COM(2015) 645 final. 15 December. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52015PC0645&qid=1663704660862.

- European Commission. 2017. Speech by President Jean-Claude Juncker at the 12th EU-China Business Summit. 2 June. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_17_1526.

- European Commission. 2022. EU27 Trade in Goods by Partner (2021, Excluding Intra-EU Trade). April. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_122530.pdf.

- European Commission and High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. 2019. EU-China – A Strategic Outlook. JOIN(2019) 5 final. March. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021a. The EU Strategic Autonomy Debate. Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/690532/EPRS_BRI(2021)690532_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021b. MEPs Refuse Any Agreement with China whilst Sanctions Are in Place. EP Press Room, 20 May. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210517IPR04123/meps-refuse-any-agreement-with-china-whilst-sanctions-are-in-place.

- European Think-tank Network on China. 2020. Covid-19 and Europe-China Relations. A Country-level Analysis. Paris: French Institute of International Relations, 29 April. https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_special_report_covid-19_china_europe_2020.pdf.

- Eurostat. 2020. EU Residents Made 1,75 Million Trips to China. 3 February. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/fr/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20200203-1.

- Eurostat. 2022. Number of Trips by Country/World Region of Destination. Last update 2 May. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tour_dem_ttw/default/table?lang=en.

- FCCC (Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China). 2019. Media Freedoms Report 2019: “Control, Halt, Delete: Reporting under Threat of Expulsion”. Beijing. https://fccchina.org/2021/03/02/media-freedoms-report-2019-control-halt-delete-reporting-under-threat-of-expulsion/.

- Finamore, Salvatore. 2015. China and Europe in 21st Century Global Politics: Partnership, Competition or Co-Evolution. Europe-Asia Studies 67 (9): 1503-4.

- Fox, John, and Godement, François. 2009. A Power Audit of EU-China Relations. Berlin: ECFR, April. https://ecfr.eu/archive/page/-/ECFR12_-_A_POWER_AUDIT_OF_EU-CHINA_RELATIONS.pdf.

- German Chamber of Commerce in China. 2021. Flash Survey: Key Issues for German Businesses in China: Ease of Travel Restrictions and Level Playing Field. Beijing. 28 April. https://china.ahk.de/news/news-details/flash-survey-key-issues-for-german-businesses-in-china-ease-of-travel-restrictions-and-level-playing-field.

- German Chamber of Commerce in China. 2022a. 2021 Annual Report. Beijing. https://china.ahk.de/membership/chamber-publications.

- German Chamber of Commerce in China. 2022b. Business Confidence Survey 2021/22. Beijing. https://china.ahk.de/market-info/economic-data-surveys/business-confidence-survey.

- Government of Greece. 2021. Protocol for Arrivals in Greece. Accessed 30 June 2021. https://travel.gov.gr/#/.

- Hale, Thomas, Lin, Andy, and Riordan, Primrose. 2022. Shanghai Lockdown Tests the Limits of Xi Jinping’s Zero-Covid Policy. Financial Times, 4 April. https://www.ft.com/content/11d1f525-6253-4238-b0f6-500f508ec073.

- Holslag, Jonathan. 2017. How China’s New Silk Road Threatens European Trade. The International Spectator 52 (1): 46-60.

- Holslag, Jonathan. 2019. The Silk Road Trap: How China’s Trade Ambitions Challenge Europe. London: Wiley.

- Horwitz, Josh. 2022. China Urges Caution Opening Overseas Mail after Omicron Case. Reuters, 18 January. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/china-suspects-covid-19-might-arrive-overseas-mail-2022-01-18/.

- Howorth, Jocelyn. 2018. Strategic Autonomy and EU-NATO Cooperation: Threat or Opportunity for Transatlantic Defence Relations. Journal of European Integration 40 (5): 523–37.

- Knoema. 2021. Arrivals of Non-resident Tourists at National Borders. https://knoema.com/atlas/topics/Tourism/Inbound-Tourism-Indicators/Arrivals?baseRegion=CN&origin=cn.knoema.com&_ga=2.216636564.30313321.1540471574-261359819.1540471574.

- Le Corre, Philippe. 2020. The EU’s New Defensive Approach to a Rising China. ISPI, 29 June. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/eus-new-defensive-approach-rising-china-26760.

- Li, Monica. 2021. How Can Foreigners Enter China under the Covid-19 Travel Restrictions? China Briefing, 19 April. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/how-can-foreigners-enter-china-under-the-Covid-19-travel-restrictions/.

- Maher, Richard. 2016. The Elusive EU–China Strategic Partnership. International Affairs 92 (4): 959–76.

- Mattlin, Mikael. 2012. Dead on Arrival: Normative EU Policy Towards China. Asia Europe Journal 10: 181-98.

- McCourt, David M. 2021. Framing China's Rise in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. International Affairs 97 (3): 643–65.

- MFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) of the People’s Republic of China. 2021. Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Announces Sanctions on Relevant EU Entities and Personnel. 22 March. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2535_665405/202103/t20210322_9170814.html.

- Mimi, Lau. 2021. Coronavirus: China Pauses Passport Renewals to Try to Keep Delta Variant Out. South China Morning Post, 30 July. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3143225/coronavirus-china-pauses-passport-renewals-hope-curbed.

- Oertel, Janka. 2020. The New China Consensus: How Europe Is Growing Wary of Beijing. 7 September. Berlin: ECFR. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_new_china_consensus_how_europe_is_growing_wary_of_beijing/.

- Pepermans, Astrid. 2018. China’s 16 + 1 and Belt and Road Initiative in Central and Eastern Europe: Economic and Political Influence at a Cheap Price. Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 26 (2–3): 181–203.

- Reisman, Diana. 2020. The EU and FDI: What to Expect from the New Screening Regulation. Research Paper Nr. 104. Paris: IRSEM. https://www.irsem.fr/data/files/irsem/documents/document/file/3270/RP%20IRSEM%20104%20-%202020.pdf.

- Riordan, Primrose. 2022. EU Warns of Hong Kong Exodus as Diplomats Oppose Covid Controls. Financial Times, 25 February. https://www.ft.com/content/f098a9cf-c1ad-4f51-8945-b80a628d8c97.

- Roberto, Katherine, Johnson, Andrew F., and Rauhaus, Beth M. 2020. Stigmatization and Prejudice during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Administrative Theory & Praxis 42 (3): 364-78.

- Rolland, Nadège. 2020. China’s Pandemic Power Play. Journal of Democracy 31 (3): 25-38.

- Schaeffer, Frédéric. 2021. Quand les expatriés français se heurtent à la grande muraille sanitaire chinoise [When French expatriates come up against the great Chinese health wall]. Les Echos, 10 June. https://www.lesechos.fr/industrie-services/air-defense/quand-les-expatries-francais-se-heurtent-a-la-grande-muraille-sanitaire-chinoise-1322544.

- Simon, Luis. 2021. The Geopolitics of Multilateralism: What Role for the EU in the Indo-Pacific. CSDS Policy Brief. Brussels: Vrije Universiteit Brussel. https://brussels-school.be/publications/policy-briefs/geopolitics-multilateralism-what-role-eu-indo-pacific.

- The Economist. 2021. China is Keeping Its Borders Closed, and Turning Inward. 17 July. https://www.economist.com/china/2021/07/17/china-is-keeping-its-borders-closed-and-turning-inward.

- The Economist. 2022. Escaping Zero-Covid: China Must Eventually Learn to Live with the Coronavirus. 26 March. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/03/26/china-must-eventually-learn-to-live-with-the-coronavirus.

- Trauner, Florian, and Kruse, Imke. 2008. EC Visa Facilitation and Readmission Agreements: A New Standard EU Foreign Policy Tool? European Journal of Migration and Law 10 (4): 411–38.

- Wu, Wendi. 2021. European Business Group Points to ‘Troubling Signs’ of China Turning Inwards. South China Morning Post, 23 September. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3149699/european-business-group-points-troubling-signs-china-turning.

- Zhao, Minghao. 2016. The Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications for China-Europe Relations. The International Spectator 51 (4): 109-18.