ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on How Texts Teach What Readers Learn (Meek, 1988) and considers how texts teach readers in a digital age. I use Meek’s book as a frame for exploring the ways children learn about narration, structure, voice, discourse and language, and becoming an “insider” in the text. To demonstrate this, I use Meek’s own stipulation “If we want to see what lessons have been learned from the texts children read, we have to look for them in what they write” (p38). Three vignettes are included as exemplars, offering insights into the ways children use their experiences as readers to create hybrid texts, drawing on different media and modes. I conclude that How Texts Teach is still highly relevant to understanding of children’s reading and writing despite changing social and material contexts, and is a frame through which changes in children’s reading and writing practices can usefully be explored.

Introduction

How Texts Teach What Readers Learn is a short book of fewer than 40 pages, published in 1988 by Thimble Press. Since then, it has been reprinted several times, the latest edition being in 2011, though the text itself has remained the same. The blurb on the back of the copy I have, from 1992, states that the book “establishes the necessary connection between literacy and literature”, and this connection continues to be an important one, despite changing understandings of both literacy and literature. At the beginning of the book, Meek tells us that it is “a workshop rather than an essay or lecture” (p3) and presents a series of illustrative examples from children’s books to demonstrate the types of “reading lessons” children learn from books. It is written in a relaxed, even conversational style, and addresses the “ordinary things that readers do” (p4) which under her scrutiny are shown to be “a little less ordinary than we first believed”. In fact, the same can be said of this unassuming book, which at first seems to be modestly offering common sense ideas about what we already know about reading, but is rather less ordinary than that, and presents a clear, analytical focus on the relationship between reader and text. In moving the discussion away from the processes of learning to read, which she argues characterised books about reading and teaching at the time, Meek places the text, “what is to be read” (p5) at the heart of the discussion.

She articulates the ways that readers learn different things from different types of text, and that different contexts provoke different readings, in order to challenge notions of a neutral text upon which neutral skills are brought to bear to create meaning. In the section “How the book works, how the story goes” (p7) Meek examines a child’s response to and experience of Rosie’s Walk, the popular picture book by Pat Hutchins (Citation1967). This section focuses not only on the story, but also on the way the whole text works; the para-text, the pictures and the way the story is told by the text and by the reader. Meek shows us the child’s developing understanding of how narrative works, of the gaps and omissions which are essential to meaning, and argues that “Nowhere but in a reader’s interaction with a text can this lesson be learned” (p13). Developing this theme, the subsequent sections “Reading Secrets” and “Lessons in Discourse” show how a reader becomes an “insider” in a text, by recognising how stories are told in a “process of discovery” (p19), by learning the rules and then subverting them. Perhaps the most notable conclusion drawn here is that “The most important single lesson that children learn from texts is the nature and variety of written discourse, the different ways that language lets a writer tell, and the many and different ways a reader reads” (p21 italics in the original). This experience in the nature and variety of written discourse remains fundamental to the way children learn from texts over 30 years later, although there have been enormous changes in both the discourses of texts and the modes and media in which texts are encountered. In the next section I briefly survey the changes in texts, and theorising around texts that have occurred since the publication of this book. I then discuss three vignettes to illustrate the reading lessons that texts teach in the digital age. Throughout the paper I use sub-headings taken from How Texts Teach to illustrate the important lessons that Meek continues to teach us in the study of children’s reading. Frequently used words or phrases taken from Meek’s book are presented in italics.

As the learning goes on

In the 30 years since the first publication of How Texts Teach there has been considerable scholarship in the field of literacy and literacy studies, much of it rooted in the work of the New London Group (Cazden et al. Citation1996), now known as New Literacy Studies. The conceptualisation of literacy as plural and multiple, using multiple modes and media, being multilingual and being dependent on contextual variety, reframed traditional ideas about literacy which focused on schooled, standardised varieties. In academic study and in school classrooms there continues to be exploration of new literacies (Pahl and Rowsell Citation2005; Kalantzis and Cope Citation2012) in particular the interaction of different communicative modes and the many insights from study of multimodality (Kress Citation2010), have contributed to new understandings of the ways that children use text and image together to create and engage with stories (Cohn Citation2013; Fisher Davies Citation2019; Pantaleo Citation2015). Meek noted in How Texts Teach that “young people nowadays practise their interpretive processes mostly by watching television” (p37). Those interpretative processes have been examined by Bulman (Citation2017), and Parry (Citation2013), (Citation2016)) whose work on film and visual narrative on screen illustrates the relationships between children’s cultures and their literacy practices, and the ways that children draw on their experiences of film in their writing. Children’s cultures are of course many and varied, but in recent years have become much more associated with on-screen and digital spaces, from children’s television channels to video games, YouTube and social media platforms. In these new and emerging contexts for literacy and engagement with narrative, research into digital literacies has explored the affordances of the digital and the ways children are adapting their literacy practices (Chamberlain, Citation2018; Dowdall Citation2006, Citation2019; Merchant Citation2013; Kucirkova et al. Citation2019; Kucirkova and Cremin Citation2020; Parry, Burnett, and Merchant Citation2017; Parry and Taylor, Citation2021). Digital spaces do not exist separately, away from other aspects of children’s lives; they are integrated into everyday experiences where online and offline activities interact. Children’s video game play, for example, becomes part of their physical play and stories from virtual worlds become part of stories children tell and play in their material worlds (Bailey Citation2016; Marsh Citation2010; Potter and Cowan Citation2020). Hybrid literacy practices, where the digital and material worlds become part of one communicative event have been explored recently in innovative ways, taking account of the relationships between virtual realities and the real world (Kumpulainen et al. Citation2021; Byman et al. Citation2022; Burnett et al. Citation2019). Social, cultural, material, embodied and digital literacies are part of children’s everyday lives and their experiences of stories, (Colvert Citation2019, Citation2022; Stephenson, Daniel, and Storey Citation2022) and the concept of the “text” in all these engagements and encounters has been demonstrated to be broadly defined. Margaret Meek’s work has not, however, been superseded by these more recent analyses; her description of the ways that text teach remains fundamental to understanding what reading means, whatever the mode or medium. Whilst the research and theorising discussed here tells a story of innovation and change in the way literacy is understood and positioned, the same change has not occurred in school curriculum and assessment practices in England. In fact it could be argued that a more traditional, functionalist approach to literacy has been embedded even more firmly into policy and public discourse in the thirty years since the publication of How Texts Teach. In the context of ongoing debates about the aims, purposes and definitions of literacy, as well as contention about approaches to the teaching of reading and writing, it is ever more important to pay attention to what children do. In the next section I will explore some examples of children’s writing to illustrate the ways that children learn from and about texts outside of formal literacy lessons.

How the text works, How the story goes

In How Texts Teach, Meek tells us that “If we want to see what lessons have been learned from the texts children read, we have to look for them in what they write” (p38). To explore this statement in reference to contemporary children in an age of digital texts, the terms reading and writing will be conceptualised in broad and multiple ways. Children’s reading includes words on screens, still or moving images and words interacting on pages or screens, and the interpretation of a range of semiotic resources in different media. Similarly, children’s writing is not only made up of examples of handwritten work on paper. It includes writing on screens, drawings, images selected and inserted into language-based texts, communicating meaning by adding sound, image, colour or symbols and working across modes and media. The examples below will show that we can still clearly see the lessons children have learned from the texts they read by looking at the texts they write.

During the covid-19 pandemic in 2020, children across the world experienced the closure of their school buildings and the transfer of all lessons online. Experiences of this varied widely across different families, schools and communities. For some children online learning was isolating and difficult, for others liberating. For many it provided opportunities to spend more time in digital spaces, whether that was taking part in online fitness sessions, watching film or television, communicating in real-time with their peers or playing video games. During the lockdowns of 2020, children adapted to changing contexts for learning and play (Play Observatory, Citation2022) and the boundaries between formal and informal learning environments became increasingly blurred. Mia, aged 11 at the time, started to write a Minecraft novel (). Situated in the game-world of Minecraft, her writing shows sophisticated awareness of “how the text works and how the story goes” (Meek, p 7); specifically, how the game works and how the story goes in the world of the game. Mia exploits her insider knowledge of the game in the story she writes; her story is not just about Minecraft, it is within Minecraft. Meek would argue that Mia has been giving herself “private lessons” (p7); she has been learning how to play and progress through the game, as well as how to share this knowledge with others through her writing. The value of these “untaught lessons” (p7) is clear in her story, as she confidently places her narrators within the world of the game. I do not mean to suggest that Mia has learned everything she knows about texts and writing from Minecraft, but rather that in this example it is easy to trace the ways that key elements of plot, character and world building have been learned from the particular type of text she is writing.

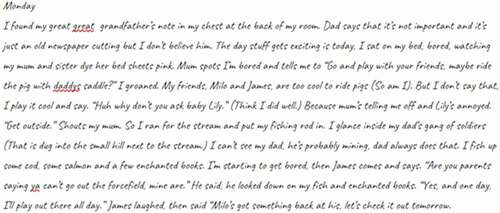

Mia is an insider in the world of the game, and to some extent her story is only fully accessible to other insiders. Inexperienced readers like myself might find ourselves at a disadvantage in this world of zombies, portals and enchanted bows. This is a useful reminder of the ways in which children may find themselves at a disadvantage when reading texts adults provide for them, especially in school. Mia’s novel requires some insider knowledge about Minecraft, and this suggests an implied reader whose experience is similar to her own. Mia writes for other fans and players of Minecraft, whom Meek would describe as members of the same clubs and networks (p20). There are several examples of “something the writer takes for granted the reader will understand” (p20), in which Mia refers to aspects of game-play that are only familiar to others with experience of the game. is an extract from the beginning of Mia’s novel, which starts with a mysterious message that the narrator has found, written by their great-great grandfather.

There are several good examples here of insider knowledge associated with Minecraft players. The first instance is the mum’s suggestion the narrator goes to ride a pig, followed by references to dad’s gang of soldiers, dad mining, the enchanted books that are fished out of the river, and the prohibition from going out of the forcefield. Insider knowledge, however, is not limited to familiarity with the features of the world, but the rules which govern the way they can be used or manipulated, and by extension, the type of story that can be written within this world.

When a child reads a story, particularly a story which does not include illustrations, the world of the text is created in the reader’s imagination drawing on the words used by the author and the child’s prior experiences. As has been demonstrated by work in cognitive linguistics, particularly Text World Theory (Gavins Citation2007) and story world theories (Herman Citation2013) the language used by the author of the text and the language experiences of the reader both contribute to the imagined world created in the mind of the reader. Once the imagined world of the text has been created, the child reader learns that there are rules which govern the way the world of the story works. These rules are learned as the child reads; expectations about places and characters are built up which explain how and why things might happen in the world of the story. These are the private lessons that Meek describes. The plot, however, is out of the control of the reader. The author of the story controls the narrative, telling the reader what happened next. The mental model which is built during reading is the product of the interaction between text and reader and is unique to each reader. But however different my imagined world of Northern Lights (Pullman Citation1995) is to another reader’s, I cannot alter the actions of Lyra or Mrs. Coulter, or prevent Lord Asriel from opening up the gap between worlds.

In a digital text such as a video game the situation is rather different. The game player enters a visually realised world which has already been created by the author/designer of the game. There are rules which govern the way the world of the game works, which the child learns as they play, and the private lessons they gain through the experience of play tell them how to make progress or solve problems in the game world. But within these constraints the narrative is entirely within the control of the player. Whether in games where a set of pre-designed options may be chosen, or a game which allows almost total freedom to the player, the player has agency. The player chooses their own narrative and chooses the perspective they take within the story being played. Decisions about who to be (a choice from a pre-defined set of avatars or a first-person “self”) and how to behave are in the hands of the player, and this has quite important implications for children as writers. Mia writes “I run past fields and birch forests until I see an abandoned nether portal. Awesome! I take some obsidian and golden armour I put the gold armour on and start to head back on my way I see a beautiful horse!” This demonstrates the way that she is working within the parameters of the pre-defined Minecraft world, but is building them into a narrative over which she has control. The perspective is first person “I”, in line with the first-person perspective experienced by a player of the game, but her story overall is constructed in a more complex manner, with different narrator voices, demonstrating knowledge of how texts work in a variety of different ways.

In the story that she is writing Mia is in control of both the world and the events in the narrative. Although she uses pre-existing world features based on the Minecraft game, she is free to choose which ones to use and how. She can use the rules of the game-world to build a story-world of her own, and it is in this sense that the lessons in discourse (p18) she has learned through her engagement with a range of texts can be seen to work together.

Lessons in discourse

Meek argues that the textual variety present in the books that children read teaches lessons in discourse. They learn how information might be communicated through text and image, about the language of fantasy and the language of realism, and about how humour and parody can subvert stories and worlds. If we also consider the range of digital texts, textual variety is further expanded to include film, television, video game and social media, and with that variety of text there are further lessons in discourse. In Mia’s story the lessons she has learned from textual variety can be clearly seen. The opening sentence “I know I will be dead before this story can be retold” shows skilful insider knowledge of the language of fantasy stories, of authorial techniques designed to intrigue the reader and to immediately place them at the heart of the action of a story. It might also remind the reader of a voice-over at the beginning of a film, but in either case is a superb example of the centring of narrator voice and perspective from the outset. It becomes clear that this voice is one from the past, which Mia indicates by writing “I ask you, show many after us about this time, many after us what it was like”. She demonstrates the way she knows that different voices can tell different stories in one narrative, and that stories are often told using the discourses of time shifts and flashbacks.

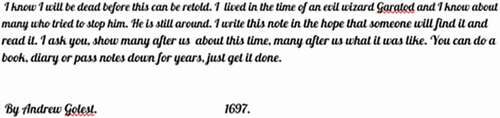

There are at least three narrators present in Mia’s story, and as well as giving them linguistically different voices, she uses visual changes to the font to indicate difference. The first voice is presented using a bold font, which looks like handwriting ().

The writer of this note is subsequently revealed to be the great, great grandfather of the protagonist, Max, whose story is told in a lighter, less formal style and font ()

Later in the plot, Max discovers a note written by his father, about him, when it is revealed that Max’s destiny is to slay a dragon ()

These examples make it clear that Mia is drawing on her insider status in the Minecraft world as she uses elements of the world in her plot. They also show that Mia is aware of the potential offered by writing online to change the font and use visual features of the text to represent character change, alongside the stylistic changes in language that she uses for each character. Mia’s story is so interesting because she creates a blended type of text which relies on digital game-world knowledge for world-building, narrative features of storytelling for the structure of the plot, and visual indicators of character difference. All of these can be seen to be lessons in discourse learned from the variety of texts she engages with.

Clubs, networks and spies

Mia exploited her insider knowledge of different texts whilst writing her story. Meek (p20) says that as well as having insider knowledge about texts, readers also become members of a club, or network, which includes other readers of the same texts. In this way, like Mia, they are able to make assumptions about what other members of their network will understand or appreciate. However, insider knowledge is not just about the individual text being read at the time, but about the connections between texts, intertextual references which reach beyond the text to other texts, and out into the reader’s wider experience of the world. Meek’s example in How Texts Teach is a reference to Tom Thumb in Each, Peach, Pear Plum by Janet and Alan Ahlberg (Citation1978). Seeing a character in a text that has previously been encountered elsewhere (as frequently happens in Each, Peach, Pear, Plum) puts the child reader into a network of connection with the author of the book, and with the other readers who share the knowledge that Tom Thumb has come from another story to become part of this one.

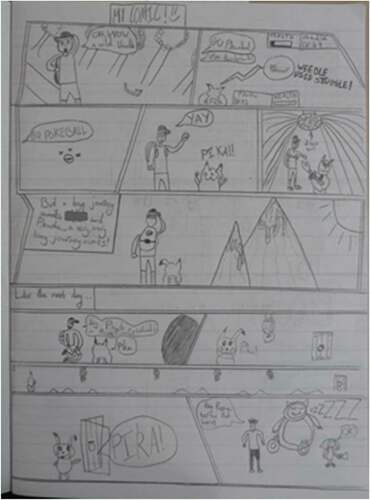

The following example is taken from a research project exploring relationships between children’s reading and their writing in primary schools (Taylor Citation2019). This rich data set was particularly illuminating about the ways that children were learning from the digital texts they encountered. Like Mia, Xavier () is able to use his insider knowledge of different texts, and the way they work, to produce his own writing Xavier clearly demonstrates the networks he is part of in this comic strip. As part of a series called “More funny Pokémon comics”, this example is named “Pokémon Hunger Games”. Drawing on his insider knowledge from his own engagement with these texts, Xavier invites a reader to be part of a network which recognises the comic potential of Pokemon characters participating in a Hunger Games (Collins Citation2008) style contest. In the dystopian young adult book and film series (Collins Citation2008; Ross and Lawrence (Citation2012-2015)), characters are selected to represent their community in a series of deadly contests. In Xavier’s comic, referencing this, he pits Magicarp and Gyrados (Pokémon characters) against each other in battle (panel 1). At the same time he invites his readers to be part of a network that recognises that the Hunger Games format has been brought in from another story to be part of this one.

However, Xavier’s intertextual connections do not end there; he goes on to signal his membership of a group of users of you tube channels who watch other gamers play their favourite games. In the third panel, in the top left-hand corner is a small box with a character shouting “Yeeeeeees!!!” Xavier has helpfully labelled this, (for all readers who are not members of his network) “youtube face cam”. This indicates that the character in the left-hand corner is playing the game, whilst the reader of the comic is positioned as the person watching the game being played. This fascinating and sophisticated dual positioning of the reader in Xavier’s text is made possible through the private lessons he has given himself, the insider knowledge he has gained from the texts he engages with, and the networks he is part of as a result of that engagement. Xavier’s text relies upon and emerges from his experiences with digital texts, but it also relies on shared understanding with a reader about the nature of the kinds of texts created by You-tube writers.

Reading lessons

A second example from the project (Taylor Citation2019; Clarke and Taylor, Citation2021) provides an illustration of the ways that readers learn about the structure, organisation and stylistic features of texts through their reading.

Meek argued that texts provided reading lessons for children because they were able to see “how dialogue appears on a page, the formal ways of making requests, the way that sentences appear on a page” (p16). Andy’s comic () demonstrates the many reading lessons he has received through his encounters with texts. These texts are themselves varied, with different conventions, but Andy creates a comic which includes elements common to different media, showing his facility with the paper based comic form and the visual features of video games. He creates a hybrid of different media in which Pokemon can be encountered, and presents them as a comic. Pokemon can be played as a trading card game; in video games and can be read in print or online in comic strip form.

In the first panel of Andy introduces the protagonist who is engaged in a game, indicated by his speech “OH WOW a wild weedle!”, who may, or may not be an avatar of himself. The way Andy has drawn the protagonist, with the backpack and baseball cap, is the same as the way the boy avatar is presented in the Pokemon video game. He also uses his own name for the character in the central panel. This suggests that he is reflecting the way things work in the video game, and is transferring this understanding to his own text. The carefully delineated double lined edges for the panels and dynamic images suggest a comic book style similar to Manga. The reading lessons Andy has received from his engagement with comics are evident in the stylistic features of the drawing, the layout and the way that text is presented. Movement and perspective are reflected in the sloping pathways (panel 1), and the mountains (panel 6). The angled divisions between panels emphasise the visual effects of the tunnel entrance (panel 8), and the passage of time is represented by the horizontal panel which breaks up the page (panel 7). Andy has learned that narration in comics is contained in boxes inside or above the panels, whilst dialogue is presented in speech bubbles close to the character that is speaking. He has also learned that upper and lower case letters can be used to indicate differences in the volume of speech. Along with comics, Andy’s reading lessons also come from the video games he has played, and these are transferred into this text to create a hybrid form.

The second panel shows a battle between the wild weedle and Pikachu. Typically, a fight scene in a comic might be a visual representation such as clouds of dust with the words “Blam!” or “Pow!” explosive lines surrounding characters to show movement, or characters drawn in motion, swiping their fists towards each other. As Andy appears to be an experienced reader of comics, it seems clear that his decision not to present the fight scene in this way is a deliberate one. Instead, he shows the battle as it would be viewed on screen. The second panel shows a “health bar” for each character, indicating the status and progress of the character. Speech bubbles show the words of encouragement, “Go Pikachu!, Use thunderbolt!” and the information on the screen tells us that “Weedle used Struggle”. Struggle and thunderbolt are weapons that can be deployed in a fight; the thunderbolt is shown being directed by Pikachu towards the weedle. This panel creates a hybrid of the video game experience, represented by the stylised fight scene, and the comic strip experience, where a protagonist participates in the events of the narrative through speech bubbles. Andy’s reading lessons from traditional comic strips and from video games have allowed him to make authorial decisions about how best to present the content of his text; he knows how things work in both of these media and is confident as an insider that he can use this knowledge to his advantage.

To return to Andy’s comic () there is another example of the combination of comic strip and video game experience. In panel 9, which runs across the width of the page, above the last two panels, Andy has drawn a long, narrow room. In the previous panel (8) Pikachu is shown on the left-hand side of a door, with what appears to be a bat hanging from above. No explanation is given about what happens next, but Andy’s reading lessons from video games tell him that where there is a door it should be reached and opened, and where there are obstacles, they should be avoided. Pikachu is shown at the left of the page in panel 9, ready to embark on an attempt to reach the door whilst avoiding the hanging obstacles, his bouncing motion indicated in the wavy line on the floor. In the panel on the bottom left (panel 10) Pikachu arrives triumphantly and opens the door, his smiling face and the large, upper case “PIKA!” indicating success.

Through exploring the writing of Mia, Andy and Xavier it is clear to see that readers in a digital age continue to learn from texts. Their reading is wide and varied and not limited to printed books, and this reading, however broadly conceptualised, has an impact on the way they write.

Conclusion; adult lessons, teaching lesson

Meek concludes How Texts Teach with two short sections which direct the adult reader to reflect on their own reading practices; and this direction remains pertinent to adults working with child readers in a digital age.

The children and young people of the 21st century practise their interpretive processes through reading books, watching television, and film, and informative you tube channels, and other people playing their preferred games, and the ever-growing range of platforms that enable young people to create their own content to inform and entertain. But the examples discussed here demonstrate that they are doing far more than that. They are also learning about narrative through books and films and video games, about authorial perspective and narrator voice, and the varied discourses of different texts. They gain insider knowledge through private lessons as they engage with different texts; they learn lessons in discourse which affect perspective, point of view and plot in the texts they create; and they join networks of other readers who play and read the same kinds of texts that they do.

The vignettes discussed in this article all discuss children’s writing which was done of their own free choice, and show the lessons learned from texts they had chosen to engage with for their own enjoyment. Research indicates that there are close relationships between the texts children enjoy reading and those they write for pleasure (Parry and Taylor Citation2018; Taylor and Clarke Citation2021) across genre, language use, style and structure. There is a danger, however, that the lessons children learn from their own reading are missed in the more structured contexts of primary school classrooms. Meek argued that “many early reading skills can be missed by teachers whose training has been strictly geared to ‘schooling’ literacy”. (p7). The child reader she describes exploring Rosie’s Walk in How Texts Teach, was a child considered to be in need of extra support because of slow progress in phonics. The need to acquire the skills required to decode texts, and the best way to acquire those skills remains a point of debate and contention (Castles, Rastle, and Nation Citation2018; Wyse and Bradbury Citation2021) and the perception of reading as a set of technical skills to be learned dominates public debate on the subject. Meek’s assertion that the reading of stories ‘is a strong defence against … the reductive power of so-called “functional-literacy” (p40) is still current although the types of texts through which children can engage with stories have diversified enormously since the publication of How Texts Teach. It would certainly not be true to suggest that all teachers are constrained by skills-based narratives about English teaching; excellent and innovative work is evident in many schools despite the directions of policy. However, if there are “teaching lessons” to be gained from revisiting How Texts Teach in a digital age, then surely they are to open up spaces for children to demonstrate how texts have taught them, to give opportunities for the reading lessons in a variety of digital texts to be explored, and to embrace the directions in which texts continue to take readers and writers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lucy Taylor

Lucy Taylor is a Lecturer in Education at the University of Leeds. Her research and teaching interests include primary literacy, children's literature, digital literacies and multimodality.

References

- Ahlberg, J. A. A. 1978. Each, Peach, Pear, Plum. London: Puffin.

- Bailey, C. 2016. “Free the Sheep: Improvised Song and Performance in and around a Minecraft Community: Free the Sheep.” Literacy 50 (2): 62–71. doi:10.1111/lit.12076.

- Bulman, J. H. 2017. Children’s Reading of Film and Visual Literacy in the Primary Curriculum. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burnett, C., B. Parry, G. Merchant, and V. Storey. 2019. “Treading Softly in the Enchanted Forest: Exploring the Integration of iPads in a Participatory Theatre Education Programme.” Pedagogies: An International Journal 15 (3): 203–220.

- Byman, J., K. Kumpulainen, C. Wong, and J. Renlund. 2022. “Children’s Emotional Experiences in and about Nature across temporal-spatial Entanglements during Digital Storying.” Literacy 56 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1111/lit.12265.

- Castles, A., K. Rastle, and K. Nation. 2018. “Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition from Novice to Expert.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 19 (1): 5–51. doi:10.1177/1529100618772271.

- Cazden, C., B. Cope, N. Fairclough, and J. Gee. 1996. Harvard Educational Review 66: 1.

- Chamberlain, L. 2018. “Places, Spaces and Local Customs: Honouring the Private Worlds of Out-Of-School Text Creation.” Literacy 53: 1.

- Cohn, N. 2013. The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Collins, S. 2008. The Hunger Games. London: Scholastic.

- Colvert, A. 2019. “Presenting a New Hybrid Model of Ludic Authorship: Reconceptualising Digital Play as ‘three-dimensional’ Literacy Practice.” Cambridge Journal of Education 50 (2).

- Colvert, A. 2022. “Dreams of Time and Space: Exploring Digital Literacies through Playful Transmedia Storying in School.” Literacy 56 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1111/lit.12271.

- Dowdall, C. 2006. “Ben and His Army Scenes: A Consideration of One Child’s Out‐of‐school Text Production.” English in Education 40 (3): 39–54. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2006.tb00799.x.

- Dowdall, C. 2019. “Young Children’s Writing in the 21st Century: The Challenge of Moving from Paper to Screen.” In The Routledge Handbook of Digital Literacies in Early Childhood, edited by O. Erstad, R. Flewitt, B. Kummerling-Meibauer, and I. S. Pires Pereira. 257–270. Oxon: Routledge.

- Fisher Davies, P. 2019. Comics as Communication. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gavins, J. 2007. The Text World Theory: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Herman, D. 2013. “Cognitive Narratology.” In The Living Handbook of Narratology, P. E. A. E. Huhn edited by, 1–20. Hamburg: Hamburg University . Retrieved from http://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/article/cognitive-narratology-revised-version-uploaded-22-september-2013

- Hutchins, P. 1967. Rosie's Walk. London: Puffin.

- Kalantzis, M., and B. Cope. 2012. Literacies. Port Melbourne, Vic: Cambridge University Press.

- Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

- Kucirkova, N., D. Wells Rowe, L. Oliver, and L. E. Piestrzynski. 2019. “Systematic Review of Young Children’s Writing on Screen: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know.“ Literacy. 53 (4): 216–225. doi:10.1111/lit.12173.

- Kucirkova, N., and T. Cremin. 2020. Children Reading for Pleasure in the Digital Age; Mapping Reader Engagement. London: Sage.

- Kumpulainen, K., J. Renlund, J. Byman, and C. C. Wong. 2021. “Empathetic Encounters of Children’s Augmented Storying across the Human and more-than-human Worlds.” International Studies in Sociology of Education online early view 1–23. doi:10.1080/09620214.2021.1916400.

- Marsh, J. 2010. “Young Children’s Play in Online Virtual Worlds.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 8 (1): 23. doi:10.1177/1476718X09345406.

- Meek, M. 1988. How Texts Teach What Readers Learn. Stroud: Thimble Press.

- Merchant, G. 2013. Virtual Literacies: Interactive Spaces for Children and Young People. Vol. 84. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pahl, K., and J. Rowsell. 2005. Literacy and Education: Understanding the New Literacy Studies in the Classroom. London: Paul Chapman.

- Pantaleo, S. 2015. “Language, Literacy and Visual Texts.” English in Education 49 (2): 113–129. doi:10.1111/eie.12053.

- Parry, R. 2013. Children, Film and Literacy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parry, B. H.-Y., Nadia, and L. Taylor. 2016. “Time Travels in Literacy and Pedagogy: From Script to Screen.” In Literacy. Media, Technology: Past Present and Future: Bloomsbury.

- Parry, B., C. Burnett, and G. Merchant. 2017. Literacy, Media, Technology: Past, Present and Future. London: Bloomsbury.

- Parry, B., and L. Taylor. 2018. Readers in the Round: Children’s Holistic Engagement with Texts. Literacy(Special ed. Supporting Reading for Pleasure).

- Parry, B., and L. Taylor 2018. ”Readers in the Round: Children's Holistic Engagement with Texts.” Literacy 52: 2.

- Play Observatory 2022: Retrieved from www.play-observatory.com

- Potter, J., and K. Cowan. 2020. “Playground as meaning-making Space: Multimodal Making and re-making of Meaning in the (Virtual) Playground.” Global Studies of Childhood 10 (3): 248–263. doi:10.1177/2043610620941527.

- Pullman, P. 1995. Northern Lights. UK: Scholastic UK.

- Ross, G., and F. Lawrence.Writers 2012-2015. In J. N (Producer). The Hunger Games, USA: Lionsgate.

- Stephenson, L., A. Daniel, and V. Storey. 2022. “Weaving Critical Hope: Storymaking with Artists and Children through Troubled Times.” Literacy 56 (1): 73–85. doi:10.1111/lit.12272.

- Taylor, L. E. 2019. “We Read, We Write: Investigating the Relationship between Children’s Reading and Their Writing in Upper Primary School.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Leeds

- Taylor, L., and P. Clarke. 2021. ”We Read, We Write: Reconsidering Reading-Writing Relationships in Primary School Children.” Literacy 55:1.

- Taylor, L., and P. Clarke. 2021. “We Read, We Write: Reconsidering reading-writing Relationships in Primary School Children.” Literacy 55 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1111/lit.12235.

- Wyse, D., and A. Bradbury. 2021. Reading Wars or Reading Reconciliation? A Critical Examination of Robust Research Evidence, Curriculum Policy and Teachers’ Practices for Teaching Phonics and Reading. Review of Education BERA.