ABSTRACT

Renovators of old buildings sometimes discover concealed inscriptions made by past tradesmen. They are a means of communicating with fellow workers and posterity and passing on the traditional culture of the building trade. This article investigates a collection of graffiti created by early nineteenth-century plumbers. It explores how and why these marks were made -in celebration of tradesmen's skills - and deduces their meanings, with particular relevance to the noxious and dangerous trade of plumbing. It analyses how these values are reflected in other surviving English plumbers’ material culture and outlines the wider use of working-class graffiti.

Introduction

Northenden is a workaday suburb of south Manchester jammed between two motorways (the M56 and M60) and a main road leading to Manchester Airport (the second largest in the UK). Traffic noise and pollution means comparatively cheaper housing, unlike that afforded in neighbouring suburbs by the cachet of lively ‘Boho’ Chorlton or sedate leafy Didsbury (‘The Hampstead of Manchester’). Now separated from open country by the vast Wythenshawe housing estate, there is little in Northenden’s present appearance, which gives a clue to its rural origins. The village was formerly a northerly parish of Cheshire with its church mentioned in the Doomsday book. The historic boundary of the county is the River Mersey, just north of the village. From the seventeenth century both a ford and ferry operated to enable the ‘Palatine’ road used to connect Lancashire southwards towards Cheshire’s salt production. Northenden’s strategic importance was also recognized by military protagonists. It is probable that Prince Rupert’s Royalist army crossed here in 1644 in its march to destruction at Marston Moor and a century later, Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Highlanders constructed a temporary bridge in Northenden to continue their fruitless progress towards London and a Stuart crown.

The village was dominated by the Tatton family based at nearby Wythenshawe Hall. In the nineteenth century, the fertile Mersey flood plain gave rise to intensive market gardening and dairying as villagers fulfilled demand for fresh produce from the burgeoning city of Manchester five miles to the north. This was helped by a permanent bridge in 1862. A subsequent horse-drawn bus service also encouraged middle-class Mancunians to settle in this desirable and commutable suburb. In the late-nineteenth century, Northenden’s riverside location also became the focus of Mancunian day trippers with large pubs, boat hire, and newly created golf courses. In the twentieth century, Northenden’s rural character declined in the face of relentless southward urbanization and in 1931 it was transferred from Cheshire to Manchester Corporation. (Though an aerial photograph of the church in 1933 on the Historic England website still shows a remarkably pastoral setting https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1200834?section=comments-and-photos)

On a sandstone bluff, to the south of the Mersey stands Northenden’s fifteenth-century Grade II* listed church of St Wilfrid. It was largely rebuilt in 1873–6 by the architect J. S. Crowther, funded by the village’s wealthy residents, but it retained many original features, particularly the battlemented tower. It forms the centre of a charming conservation area. Over a decade ago, this author climbed the uneven and windy stairs, past the belfry, to the top of the tower, opened to the public as part of a tour laid on for the annual Civic Trust Heritage Day. The last 15 feet was by a vertical ladder and whilst my companions took in the superb views over the Mersey flood plain and south Manchester’s green southern suburbs, my attention was drawn by the lead sheets covering the tower’s roof and the deliberate marks in them. These were covered with inscriptions made by nineteenth-century plumbers including dates, names, initials, shoe and hand outlines, representations of tools and equipment, and other strange symbols significant to the plumbers’ trade.

This article will describe what can be observed at St Wilfrid’s, explore how and why these marks were made, and deduce their meanings. It will discuss graffiti, especially in the building trades and its use in commemoration and in the observance of skill. Plumbing was a particularly dangerous occupation, whose stock-in-trade (lead sheets) was inherently noxious (.). Plumbers therefore adopted a distinctive culture, partly private and secret but also public and celebratory. This culture will be examined, engaging as case studies of surviving objects used in their ceremonies. The article will go on to explore the wider use of working-class graffiti to record, connect with the past and future, and sometimes also to protest anonymously. Surviving graffiti can offer a rare direct connection to generally silent working-class voices struggling to earn a living in times of momentous economic change. Lastly, comments will be made on recording, preserving, and interpreting graffiti for posterity as its creators may have intended.

Description

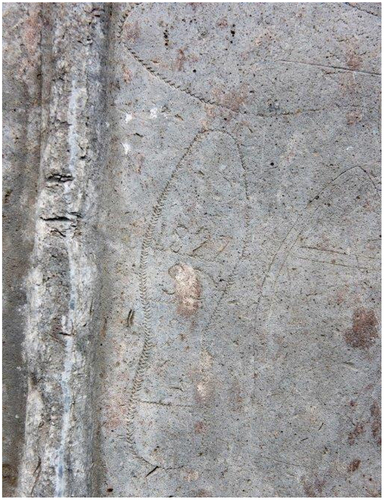

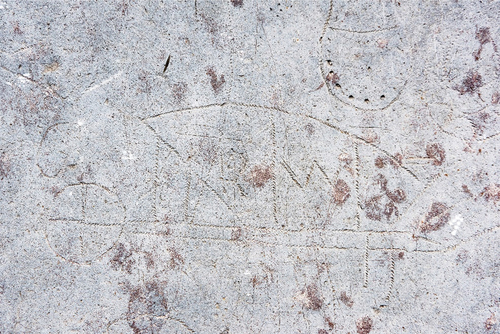

Subsequent visits to the tower revealed several hundred inscriptions. Many were difficult to identify, but a grant from the School of Humanities, Languages and Global Studies Faculty Research Fund at UCLan enabled a professional photographer to be commissioned. Her photographs, taken on a sunny day, revealed previously unnoticed details and made the task of identification much easier. The most distinct images were finished with herring bone edges, often with a double outline, with a chisel type tool, which gave a slightly three-dimensional impression. There was no pattern to the images. They were clearly added at various times and at various places according to the fancy of the inscriber in locations where there was unoccupied space on the leads.

Dates were surprisingly sparse with only 1807, 1827 (.), 1836, 1854, and 1855 represented. These were usually entered alongside initials with JLN (1807), SD (1827), C IL (1836), and RG (1854). All of these were as part of shoe outlines.

JS, SD, and JB were inscribed on other shoe designs with no date, as was RW, on an inscription of a wheelbarrow (.). JB 1855 (.) was on the wrist of an elaborate hand design, which may well have included a cutting knife and a representation of the sacred heart symbol, used by both friendly societies and Roman Catholics.

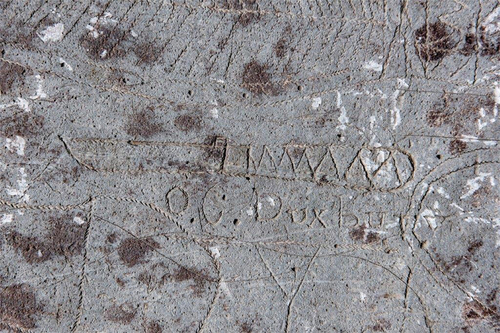

Other initials and names unattached to particular images included RW, L J TRAN, P R Meehan, and Peter Bricknell. O. C. Duxbury was ‘signed’ next to a fine image of a hacking knife used by plumbers, glaziers, and house painters (.).

There were four other outlines of leather handled hacking knives, perhaps indicating that this was the tool that was used by the creators. Other tools may have been intended, particularly files, indicated by cross-hatching, but much of the carving is indistinct. There were two possible representations of knives with sharper blades, used for cutting up sheets of lead. The largest number of images were of shoe outlines with over 100 represented, closely followed by several scores of hand outlines. By modern standards, all these shoes were small. Two (dated 1836 and 1854) had square rather than round or pointed toes, and many were shown overlapping and inter-locking. Two shoes that were side by side were particularly small, perhaps indicating that they were made by apprentices.Footnote1

In their work on objects concealed in buildings, Ceri Houlbrook and Owen Davies stress the importance of shoes, both actual and representational, so shoe outlines may relate to this custom. Anthropologists have concluded; ‘As bearer of the individual’s imprint, the shoe functions as a signature – a spiritual graffito’. However, at St Wilfrid’s, it may be that bored plumbers used whatever was most available, i.e. their hands and feet.Footnote2

There were two detailed carvings of the ‘all-seeing’ Eye of God, an important early nineteenth-century icon used widely by working class and friendly societies in their regalia. There were also several crude representations of Union Jacks, again widely used by trade unions and radical political groups in the early nineteenth century. Both these aspects will be discussed later.

Context

These images are enigmatic and tantalizing, raising more questions than answers. We can assume that they were made by plumbers working in various years in the early-nineteenth century for their own amusement. We can speculate that they were made in breaks during work, usually the mid-morning ‘lunch’ traditional in the building trades and mid-day ‘dinner’, especially if the carvers did not wish to descend from the tower. Essentially, the images are private in nature and were only intended for other workers of the future, especially plumbers. There was a long tradition amongst building trade workers of recording ‘concealed’ messages. The introduction of wallpaper in middle-class homes from the mid-eighteenth century, in particular, gave house painters the opportunity to pencil messages, typically consisting of names, dates, and rate per hour of the job.

In the nineteenth century, plumbers supplied, fitted, and crafted lead needed for roofs, gutterings, and cisterns, to keep out rainwater in dwellings and commercial buildings. As domestic hygiene improved, they also installed sewerage and washing systems in houses and workplaces. Most provincial plumbers were also skilled in glass work of all kinds, as windows largely had lead fixings: ‘In the country it is not infrequent to find the business of a plumber, glazier and painter, is united in the same person.’ Footnote3

The world of plumbers was especially close knit, inward looking, arduous, and often embattled, compared with other workers, simply because their stock-in-trade was noxious In their workshops, plumbers ‘cast’ their own sheet lead from ‘pigs’ typically weighing 150 pounds (68 kg), before transporting it to a job. These dangers were recorded candidly in the early nineteenth century in Philip's Book of Trades: ‘The health of the men is often injured by the fumes of lead. Journeymen earn about thirty shillings a week; and we recommend earnestly to lads, that they cultivate cleanliness and never, on any account, eat their meals, or retire to rest at night, before they have well washed their hands and face’.Footnote4

Even in the late-nineteenth century, Raymond Postgate noted: ‘The effects on the operative plumber had always been deadly; the average age at death of a union member in 1890 was only thirty seven years.’ Fortunately, the death rate of plumbers decreased as cheap mass-produced ceramics gradually replaced the more expensive lead goods in the late-nineteenth century. Painters, though, continued to grind paint from lead-based pigments with stone mullers well into the twentieth century. Many suffered therefore from ‘painters’ colic’, intense intestinal pain, associated with obstinate constipation caused by chronic lead poisoning.Footnote5

Despite these dangers, plumbers exhibited great pride in their craft skills combined with a macho disregard for danger often shared by other building tradesmen. The inherent dangers in handling sheet lead meant that plumbers were considered a poor risk by friendly societies, so they had to form their own benefit clubs and, as we shall see, trade unions.

The tradition in the parish is that the plumbers were from a Stockport firm who walked four miles along the Mersey to Northenden. Unsurprisingly, they were therefore not inclined to take unnecessary further exercise by descending the St Wilfrid’s tower during breaks. Regretfully, the Covid crisis has prevented the study of any parish records held in the church, which may have provided details of the work and the firm commissioned to undertake it. It is likely that over the nearly 50 years covered by the dates recorded there were a small number of re-fittings of the leads followed by various repairs. None of the names recorded match those of firms listed in Stockport trade directories of the period, indicating that the carvings were the work of journeymen plumbers rather than master plumbers. There were a surprisingly large number of plumbers’ firms in Stockport, which like Northenden was in Cheshire during this period. However, as were common outside cities, these firms also undertook glazing and house painting along with plumbing. The earliest directory in 1811, records four concerns, rising to 21 by 1851, though by then gasfitting was added to the trades that they undertook.Footnote6

The rise in the number of plumbing firms indicates that Stockport was prospering through the town being part of the huge ‘Cottonopolis’ boom, which propelled the region’s textile economy to national and international significance. As well as working on larger private and public buildings, plumbers would also be employed on dwellings as the flourishing middle class aspired to the latest ‘mod cons’.

Surviving plumbers material culture

Just as no surviving business records have been located by Stockport plumbing firms, no objects connected to plumbers have been acquired by Stockport Museums and Galleries. Aspects of plumbers’ culture will therefore be explored using examples surviving in other parts of England.

The oldest objects located come from Ludlow in Shropshire. One is a banner or ‘streamer’ used by the town’s Hammermen’s trade society. Medieval guilds tended to survive in smaller provincial towns, though in early modern times they often merged into trade societies that represented groups of skilled workers as well as small masters. Ludlow in Shropshire had two companies each of six trades; the Stichmen, whose main symbolic tool was the needle, and the Hammermen, who used the hammer. The latter included Ludlow’s plumbers. The Hammermen’s archives, still extant, record trade union-type activities concerned with wages and conditions, along with drinking and feasting. They also took part in an ongoing civic calendar of local and national events in which they used long guidon-shaped flags or ‘streamers’. The first mention of their use was in 1693, but it is likely that this example is the eighteenth century in origin:

At festivals and state occasions the Hammermen would take part in civic events about the town. It is recorded that it was the duty of the two youngest freemen to carry the guild’s streamers at the head of the ‘fraternity’ when it was in procession. The banners were also paraded at the pleasure fair, held annually on 1st May … The Hammermen’s streamers were reported as last carried in procession at the birth of Robert Windsor-Clive, heir to the Clive estates, in 1824.Footnote7

The streamer is elaborately painted with bastardized versions of the coats of arms of the relevant City of London Livery companies, which by this time were evolving into rich men’s clubs. Each streamer had three coats of arms on each side. shows the top of the hammermen’s streamer with Plumbers Arms with tools (soldering irons, shave hooks and wooden bobbins) and the Glaziers Arms with crossed glazing irons.Footnote8

The streamer on one pole was waved in stylized patterns creating an unwritten language, now lost, which was presumably understood by participants and spectators. In some towns, flag carriers wore exotic uniforms and were paid for their efforts. Such activities were severely curtailed by the reforming Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, which prevented local authorities from spending money on such fripperies.

However, it would be wrong to present such groups purely as loyal paternalistic drinking clubs. The Ludlow Hammermen could display the ‘multi identities’ typical of the nineteenth-century working class. In 1820, the Hammermen paid a delegate, Richard Russell, 15 shillings a day to travel to London with an address to Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of the Prince Regent, whose complaints were taken up as a radical cause. In 1831, the Hammermen submitted a radical petition to the House of Commons supporting the Reform Bill, again sending Russell to London, along with a similar petition from the Stichmen. By 1862, the Ludlow societies had collapsed as a result of part of the general modernization of such activities.Footnote9

The Ludlow Hammermen, like many other working-class organizations, made a charge on their members and tried to control their income and expenditure. Managing money was a problem, since banking was closed to bodies that had no legal status. This meant they often felt under threat from the law deployed by government or employers. Consequently, groups’ assets continued to be cash-based and handling comparatively large sums could prove a temptation for poor tradesmen and labourers. In the early days, many branch officials embezzled or absconded with funds. A solution was found by using boxes with several keys, each held by a different individual, which can only be opened in the presence of all.

The box shown in was used by the Hammermen’s company of Ludlow. From the seventeenth century, they spent their funds attempting improvements in wages and conditions, drinking and feasting and on democratic, and often radical, politics. The simple box is made of oak and is of great antiquity. It may well be the ‘common box or treasury’ that the Hammermen are recorded as having made in 1669.Footnote10

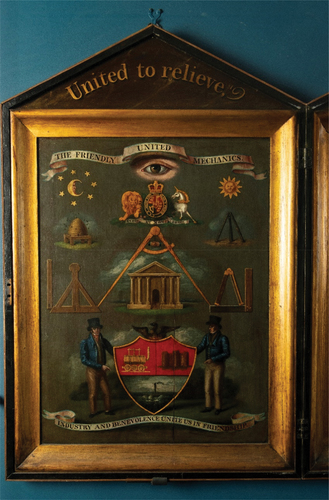

The ‘All seeing eye’ () made by plumbers on the St Wilfrid’s roof leads is not repeated in any other known surviving plumbers’ material culture. However, the image was widely used in other working-class iconography, indicating the importance of religion, belief, and also the ambition for workers’ organizations to be taken seriously and behave responsibly. They wished not to be condemned as subversive and disloyal during a period of social and economic turmoil but to stake their claim to be part of Britain’s political body in a more democratic future. They also wanted to display pride in their craftsmanship and celebrate their contribution to Britain’s new rapidly expanding industrialism, often by embracing technological change. Within the town of Stockport, this was exemplified by the surviving painted emblem of the Friendly United Mechanics, from about 1829 (). This trade union evolved from millwrights, via the Steam Engine Makers Society and by mid-century was to become a major component of the powerful New Model Union, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers.

The emblem was designed as a diptych, to be opened when the society meeting was in progress, probably in a pub. Members’ deliberations would then be overseen by the iconography, slogans, and products of the trade. As with any skilled working-class nineteenth-century organization, the key tools of the trade are carefully represented; here dividers, set square, ruler, and spirit level. Members of the trade are depicted in respectable working dress of the 1820s as supporters of a shield that shows a railway locomotive and a steam ship. These demonstrate extreme pride in contributing their skills to the new technology making Britain the world’s first industrial nation. It also emphasizes their determination to secure commensurately high wages.Footnote11

The slogans emphasize the defensive, peaceful, and mutual aid aspects of the organization with the slogan: ‘Industry and Benevolence Unite Us in Friendship’. This is reinforced by the loyalism of a borrowed royal coat of arms, overseen by the powerful all-seeing eye of God. This symbol is ubiquitous in early nineteenth-century working-class iconography. It dominates the world’s oldest trade union banner, that of the Liverpool Tinplate Workers banner, 1821.Footnote12

The ‘All-seeing eye of God’ also appears in overtly radical political material culture, such as in a horn beaker, decorated with a carving of the membership card of the National Chartist Association, made about 1842. This beaker is a good example of the use of an everyday object to affirm the owner’s political views and was possibly made by the user.

However, the best representation of plumbers’ culture and tools (particularly the hacking knife depicted at St Wilfrid’s) amongst surviving material culture is found in the Norwich Plumbers’ Emblem, c.1833. (). Painted on wood, it almost certainly hung in the Plumbers Arms ‘house of call’ in Norwich. It is more than probable that it is a relic of Robert Owen’s attempt to link trade societies to the first modern national union of all trades. It was probably made by a member, given that provincial plumbers often also undertook painting and glazing. It shows the society’s pride in skill and a spurious antiquity in borrowing the heraldry of the medieval guilds though linked to what functioned as a modern trade union.Footnote13

Houses of call were pubs where artisans could meet secretly to discuss politics and knowledge of the trade and where available work opportunities were publicized. Sympathetic landlords provided an upstairs room where one or more societies could meet and store their precious regalia and papers, in return for the custom, which their activities generated. Landlords, often ex-tradesmen, sometimes acted as officials or even safeguarded funds on behalf of the society. In some trades, houses of call formed networks across Britain and Ireland within which unemployed or striking tradesmen ‘on tramp’ could seek work or be helped on their journey. In their early years, trade societies were underground, illegal, and embattled. They endured legal prosecutions and police raids from allied employers and government, who deemed the trades societies’ sturdy democracy to be subversive and alien.

The shield on the emblem was lifted from the City of London Livery company founded in 1611, referred to in the painted motto at the bottom. The painter covered it with highly accurate depictions of the tools of the trade, including round and square shavehooks, wooden dressers and bobbins, plumb lines, hacking and putty knives, rules, and measures. The two supporters are dressed in the contemporary stylized processional costume; smart Sunday best dress with clean white aprons and hats and hold soldering irons as the main symbol of their trade.

As already noted, plumbing was a dangerous trade. Working with sheet lead on large buildings and churches was hazardous and led to high death rates. It is small wonder that friendly societies and other unions would refuse plumbers membership. Instead, from an early stage, plumbers’ embattled self-reliance resulted in attempts to create their own self-support organizations. In 1846 plumbers complained: ‘How often do we see the poor but honest working man, he whose hand produces all we boast of beyond a savage state pining in sickness or distress with his family starving amidst the wealth he has been instrumental in creating’. As early as 1831 a National Plumbers Union was set up, perhaps a thousand strong, mainly based in Manchester and the North, and it is highly likely that the Stockport plumbers were members, along with the Norwich lodge responsible for this emblem.Footnote14

Two years later, James Morrison, a charismatic young Birmingham house painter, inspired by radical politics and Owenite socialism, founded an Operative Builders’ Union (OBU). This drew in all of the building trades, including plumbers, and led to a national recruiting campaign, which is likely to have included the Norwich Plumbers. In Birmingham, the OBU, advised by Robert Owen, submitted its own tenders for co-operative building projects and in December 1833 celebrated the laying of the foundation stone of the Operative Builders Guildhall, with a procession of all trades. Morrison also edited a builders’ newspaper The Pioneer. Owen, though, had more grandiose plans and opened the OBU to all workers to create the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (GNCTU) into a federal structure that flourished in an initial wave of enthusiasm, with several hundred thousand members, before collapsing under joint attack from employers and government.

How long the Norwich plumbers trade society survived is unknown, as the collapse of the GNCTU set back building trades unionism for a generation. It wasn't until 1865, in the wake of the New Model Unions, that the National Plumbers Society re-established itself. The same story also probably applied to the Stockport plumbers.Footnote15

Most of the objects discussed so far illustrate the private and indoor culture of the plumbers. At various points in the early nineteenth-century, working-class organizations felt strong enough to actively advertise their presence and political opinions without fear of accusations of sedition, with the danger of prosecution by employers or government. This was seen especially in the mobilization of working-class support by the Whigs and Liberals during the Reform Crisis of 1831–2. Banners were the most common of these public expressions, and typical of them was a Plumbers Reform banner, made like many others for the celebrations after the passing of the Great Reform Act of 1832 (). Footnote16

From careful perusal, it can be concluded that it started life as a wall or table covering for secret meetings of the trade before being converted for public display. Pride in the plumber’s craft figures largely in this banner. The shield is adapted from the coat of arms of the City of London Plumbers Livery Company. On it are depicted the plumbers’ tools: plumb line, mallet, plumber’s dresser, plumb square, grozing iron, hacking knife and soldering iron. On top of the shield is a delicately painted figure of Justice labelled with the motto ‘JUSTITIA PAX’. The other mottos are typical of the uplifting messages that the society was attempting to convey, in order to give an organization on the fringes of the law added gravitas. ‘In God All Our Hope’ emphasizes the society’s underlying Christian principles already seen in the ‘All seeing eye of God’ iconography.

It is most likely that this banner was constructed from a smaller wall or table hanging used by this local Plumbers trade society in its secret meetings and then simply sewn onto a larger blue sheet. It was a case of its literally emerging from an underground existence to become emblematic of the new and increasingly confident working class.

The name of this particular plumber’s society was not given on this banner, so its location is unknown, but it is thought that the banner may have originated in Cumbria. This is quite possibly given that pro-Reform meetings involving trade societies took place all over Britain. Carlisle in particular had a strong radical tradition. But these Reform Act processions ended in disappointment when the details of the act were received. The new franchise, based on property qualifications, led to a narrow electorate, which excluded working-class men for another generation.

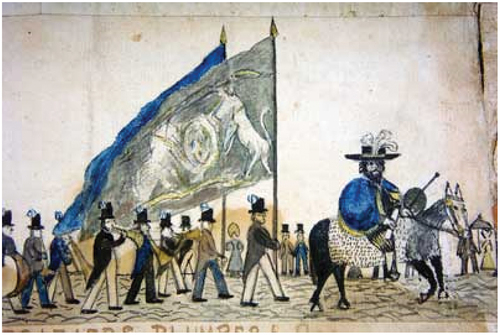

The way in which trade societies used their banners in the early-nineteenth century is rarely recorded, especially regarding images. The most dynamic image known to the author of any trade societies is recorded in a charming long ink and watercolour painting by Samuel Hulbert, an eleven-year-old bookseller’s son, entitled ‘Representation of the Shrewsbury Show’, 1831. An annual trades procession in the Shropshire county town, the Shrewsbury Show was a vestige of the Medieval feast of Corpus Christi, and was a hedonistic day of procession, drinking, and feasting, which drew thousands of visitors to the market town.

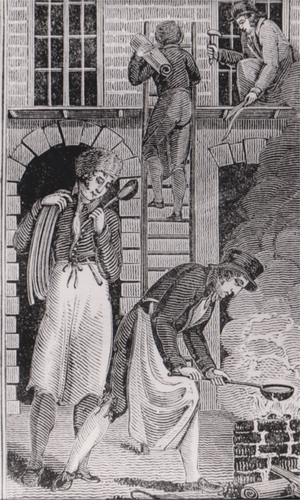

Ten companies of journeymen and apprentices were arrayed with banners, flags, bands of music, Sunday best clothes, staves, and iconic representations of their skills, each led by a mounted ‘King’ as representative of their trade group. Some companies consisted of groups of trades; for example, the painters also included the related plumbers. They were decked in yellow and purple ribbons and led by ‘Peter Paul Rubens’ holding a painter’s guide and pallet (). The coat of arms on their flag has panther supporters, a play on their name used in their iconography by the Society of House Painters until the 1930s.

Figure 12. Painters and Plumbers led by ‘Peter Paul Rubens’ from ‘Representation of the Shrewsbury Show’, 1831.

The huge spectacle drew crowds into Shrewsbury. The companies each had their own ‘Arbours’ in Kingsland just across the river Severn, outside the town. There they sold food and drink to the participants, alongside dancing, booths, and fairgrounds. The resultant rowdy behaviour led to attempts at repression, with a critical Methodist tract in 1831, and weakening official support from the mayor after the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. However, the arrival of railways in Shrewsbury in 1848 gave the show a temporary fillip by encouraging spectators from West Midlands and Welsh Marches. However, the granting of Kingsland to Shrewsbury public school by the corporation proved its death knell and the parade was abolished in 1878.

The young artist, Samuel Hulbert, was clearly obsessed with the occasion. He also wrote a detailed 90-page description of the Show, still extant. (It has been suggested that he may have had Asperger’s.) He died whilst studying for ‘holy orders’ at Cambridge University, in 1846 aged 22 ‘cut off by atrophy’. The painting is in Shrewsbury Museum alongside some surviving Show regalia, such as a buff coat worn by St Crispin, the leader of the shoemakers, which is likely to be of Civil War origin, a breast plate made by the blacksmiths for their King and a tenor drum used by one of the bands of musicians, likely to be militia origin. This unique picture is a valuable reminder that as well as being involved in protest and organization, the nineteenth-century workers also knew how to have fun.Footnote17

Plumbers taking part in civic festivities in other parts of the country went to even more elaborate lengths. During the 1882 Preston Guild procession (held every 20 years), the plumbers and glaziers’ float displayed a garden scene, with intricate lead fancy work including a working water fountain.Footnote18

Wider use of graffiti to commemorate and protest

Nineteenth-century graffiti was widely used to record a working-class presence and connect with the past and future. One example was discovered during the 2020 renovations at Dove Cottage, Wordsworth’s home and museum, in Grasmere, Cumbria. Here, layers of tradesmen’s graffiti from different dates were discovered inscribed on the back of a wooden window shutter dating to the original conversion of the house, begun by painters in 1891. These have been retained as part of the new display.

Graffiti was also a long-established form of working-class protest, as communication was anonymous. It was used extensively by trade societies in disputes to shame mean employers who would not pay the agreed price of labour. It was adopted especially by political radicals to campaign and communicate in the post-1815 government repression.Footnote19

Such anonymous, often radical, comments were often written in chalk, such as ‘Whether the subject regards bread or peace NO KING introduces it’ found on a Manchester wall in 1800. An openly seditious message was painted on Chester’s medieval walls at the height of the Queen Caroline agitation in 1820: ‘No Damned Royal Crown’, ‘No Damned King’, ‘A short Reign & a bloady one: Behead him’.Footnote20

Perhaps influenced by Robert Owen’s early socialist ideas, a group of builders in Edinburgh concealed the following message in a bottle behind plaster work in the Union Bank in Parliament Square, Edinburgh:

December 1829. – Men of other years, this will inform you that the plaister work of this Bank was executed by the undersigned individuals in the employ of Mr James Anderson, wages at the present time being 13s per week, and the trade in a very bad state, consequently a great number of the profession are feeling the most serious privations. Reader, when this comes to your eye the winds of (perhaps) a hundred winters will have blown over our graves. May it have a salutary impression on your mind, when it informs you of the dissolution of all human affairs. – JOHN CAMPBELL, foreman; ARCHIBALD DONALDSON, RODERICK INNES, THOMAS KIRKWOOD, ROBERT ALLAN, JAMES ROUGH, ALEXANDER MILNE, JOHN INNES.

The bottle discovered in 1884 was as Houlbrook and Davies comment, a ‘poignant message in which the builders addressed the future directly with their reflections on mortality’.Footnote21

In the Spring of 2020, a previously concealed passageway was discovered in the Houses of Parliament, on whose walls was the inscription:

This room was enclosed by Tom Porter who was very fond of Ould Ale. Congdon Mason T. Parker Williams P. Duval Terrey. These masons were employed refacing these groines. Aug 11th 1851 Real Demorcrats.

The latter was an ironic political comment in the Mother of Parliaments as the Chartist movement, which would have given these tradesmen a vote, suffered a major defeat in 1848 and was then virtually moribund. The construction of Barry’s new Houses of Parliament had already resulted in bitter industrial disputes such as the masons’ strike of 1841. A later painter, Alan Leiper, added his own name to the inscription in 1950.Footnote22

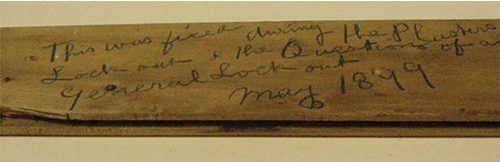

Graffiti could also record trade disputes. Builders found a wooden panel (.)in a Leeds office in 1997 while removing a partition wall that reads: ‘This was fixed during the plasterers lockout and the question of a general lockout May 1899’. An attempt had been made by the Master Builders’ Association (MBA) to test the strength of the National Association of Operative Plasterers (NAOP) by locking them out, therefore preventing them from working. Other building unions feared similar measures and supported the plasterers against the MBA, despite the threat of a national general lockout. So, in June 1899 the MBA was forced to back down.Footnote23

Anonymous graffiti were also sometimes used by groups of workers who were not in a position to protest, such as British common soldiers. The political comments of nineteenth-century soldiers were recorded scrawled in barracks in Britain, India, and South America. They were used as early as 1807, when the miserable British captives who surrendered after their failed assault on Buenos Aires no doubt mystified their captors with the chalked comment on their commander: ‘General Whitelocke is a coward or a traitor or both’. The slogan was apparently soon also seen on the streets of London.Footnote24

Peter Stanley’s pioneering work shows how soldiers in India used graffiti chalked on walls to demonstrate a variety of previously concealed feelings, ‘in the otherwise hidden world of the Victorian barrack room’. Comments cover racism: ‘Kill the Darkie’; corrupt NCOs: ‘Sergeant – is suspected of having put water in the grog; ‘tis to be hoped that he’ll not be guilty of such unsoldierlike conduct in future’; and the ‘White Mutiny of 1859: ‘“Unity is Strength”, Men and Comrades are we to be sold like a lot of pigs … now let us be men and stand up for our rites [sic]’, ‘Damn the Queen, Company for ever, give us bounty’, ‘and lastly ‘John Company is dead, we will not soldier for the Queen’. In the ‘White Mutiny’, nearly 10,000 white soldiers employed by the East India Company successfully struck work and occupied their barracks against forced transfer to the Queen’s army.Footnote25

As late as the First World War, protest graffiti were used by enlisted soldiers, who as conscientious objectors were imprisoned in Richmond Castle, North Yorkshire. They have recently been conserved and interpreted by Historic England.Footnote26

Conclusion

This article has located its hidden historic narrative in the Manchester suburb of Northenden. It has described the unusual graffiti found on the leads in the tower of St Wilfrid’s Northenden and interpreted their meaning in the context of the close knit, proud, skilled but dangerous trade of plumbing. These traits have been investigated using rare surviving material culture of the plumbing tradesmen’s organizations. It has also explored the wider meaning and use of the nineteenth-century, working-class graffiti, including in anonymous protests.

In 2016, English Heritage published a guide to Recording Historic Graffiti: Advice and Guidance, with input from the Institute of Historic Building Conservation. This included an illustration (p. 36) of a shoe outline graffiti on a church’s roof leads almost identical to the St Wilfrid’s examples. The guide outlines how to conduct a full archaeological survey of discovered graffiti. This was beyond the scope of the present study, but it is intended to deposit the commissioned photographs and this article with Historic England.Footnote27

Acknowledgments

The School of Humanities, Languages and Global Studies Faculty Research Fund at UCLan for its generous support. Staff at the following museums have kindly provided images and assistance; Megan Dennis (Norfolk Museums Service), Sam Jenkins (People’s History Museum), Emma-Kate Lanyon (Shropshire Museums). Individual thanks are due to Rev. Andrew Bradley, Mark Collins, Owen Davies, Paul Good, the late Fred Mansfield, Julia Mansfield, Stef Mastoris, Karen Wright (photographer), Martin Wright, and Bridget Yates.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Early nineteenth century apprentices could be even pre-teen and surviving images show clearly their small stature see the plumber/glazier and apprentice in George Maton’s The Green, Marlborough, c. 1840, in James Ayres, Building the Georgian City, (Yale UP, 1998), p.181, and the apprentices in Samuel Hulbert’s painting, 'The Representation of the Shrewsbury Show', 1831, discussed in Nick Mansfield and Martin Wright, Made by Labour – A Visual and Material History of British Labour, 1780–1926, (University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 2023).

2. Ceri Houlbrook and Owen Davies, Building Magic: Ritual and Re-enchantment in Post-Medieval Structures (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), p. 84.

3. The Book of English Trades and Library of the Useful Arts, (Sir Richard Philips, London 1824), p. 308.

4. Philips Book of English Trades, p. 308.

5. R. W. Postgate, The Builders History, (London; Labour Publishing Company, 1923), p. 234. See also James Ayres, Art, Artisans and Apprentices – Apprentice Painters and Sculptors in the Early Modern British Tradition, (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014) and R. A. Leeson, Travelling Brothers – The six centuries’ road from craft fellowship to trade unionism, (London: Granada, 1979).

6. Holden’s Annual London and Country Directory, of the United Kingdoms, and Wales, Vol. II, (London: W. Holden, 1811) and Slater’s Manchester and Salford and their Vicinity Directory, (Manchester: Isaac Slater, 1851).

7. G. M. Hills, ‘On the Ancient Company of Stichmen of Ludlow’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, vol. xxiv, (1961) p. 5.

8. The streamer is in the Shropshire Museums Service collection (H.20102). It measures 337 × 99 cm. and is held at Ludlow Museum.

9. Shropshire Archives, Records of the Ludlow Hammermen, LB 16/217 and 238.

10. Shropshire Archives, Records of the Ludlow Hammermen, LB 16/298. The box is in the collection of the Shropshire Museums Service (H.01969) and measures 51 × 36 × 28 cm.

11. The emblem was donated to the People’s History Museum in Manchester (NMLH. 1992.66) by the Stockport branch of Amicus having been preserved by successive iterations of the union for nearly 200 years. It measures overall 127 × 92 cm.

12. See Nick Mansfield, ‘Radical Rhymes and union jacks: a search for evidence of ideologies in the symbolism of 19th.c.banners’, University of Manchester, Working Paper in Economic and Social History, No.45, 2000, http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/arts/history/workingpapers/wp_45.pdf and Mansfield and Wright, Made by Labour,2023).

13. The emblem is in the collection of the Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service, (NWHCM : 221) at the Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse and measures 32 × 27 cm.

14. RW Postgate, The Builders History, (London; Labour Publishing Company, 1923), pp. 20 and 133.

15. Nick Mansfield, ‘The Norwich Plumbers Emblem’, Social History Curators Group Journal, No.14, 1987, pp.29–31. See also Postgate, Builders History and Malcolm Chase, Early Trades Unionism – Fraternity, Skill and the Politics of Labour, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

16. Banners from the Reform Crisis of 1831–2 are discussed in Mansfield and Wright, Made by Labour, The banner has a ground of cotton with applied central area of oil-painted linen edged with silk. It measures 238 × 200 cm and can be seen in the People’s History Museum’s Reform Act display (NMLH.1998.24.AEEU.1).

17. The painting is covered in detail in Mansfield and Wright, Made by Labour.

18. Illustration of the Preston Guild in The Graphic, September 16, 1882.

19. For a discussion of political and trades graffiti see Iorwerth Prothero, Artisans and Politics in Early Nineteenth-Century London (Folkestone: Dawson, 1979), Chapter 2.

20. Adrian Randall, Riotous Assemblies – Popular Protest in Hanoverian England, (Oxford: OUP, 2006), p. 227, and Malcolm Chase, 1820 Disorder and Stability in the United Kingdom, (Manchester: MUP, 2013, p. 71.

21. Houlbrook and Davies, Building Magic, p. 82.

22. Prospect, April 21, 2020 https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/the-rediscovery-of-a-fascinating-parliamentary-secret-history-17th-century-doorway.

23. The panel is in the collection of the People’s History Museum (NMLH.1997.25) and measures 395 × 95 mm.

24. J.W. Fortescue A History of the British Army, Vol V (London: Macmillan, 1921), p. 430 and Nick Mansfield, Soldiers as Workers – Class, employment, conflict and the Nineteenth Century British Military, (Liverpool: LUP, 2016), p. 177.

25. Peter Stanley, ‘“Highly Inflammatory Writings”: Soldiers Graffiti and the Indian Rebellion’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 74 (1996), pp. 236, 238, and 242–3.

27. English Heritage Recording Historic Graffiti: Advice and Guidance (2016), https://doczz.net/doc/2603612/recording-historic-graffiti–advice-and-guidance.