ABSTRACT

In Sweden, immigrants’ integration and residential patterns are much disputed. Segregation is seen as a threat to social cohesion and policies at least rhetorically aim to create mixed neighbourhoods. Immigrants’ settlement patterns and residential mobility are often explained with competing spatial assimilation and place stratification theories. Building from these two theories, this study investigates immigrants’ mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods by clarifying the role of immigrants’ country of origin in association with socioeconomic status, while emphasizing the importance of settlement context. The paper presents a survival analysis based on everyone who migrated to Sweden from 1990 to 2010. The conclusion is that immigrants’ backgrounds strongly shape residential outcomes, and that spatial integration can be facilitated by a better housing market position at the start of the housing career in Sweden, by labour market participation, and good educational attainment. There are better prospects of ending up in native-dominated neighbourhoods outside metropolitan areas, whereas in metropolitan areas, increase in income has less impact on residential mobility and the opportunity structures for spatial integration are much more constrained, especially for refugees. The study finds more support for the place stratification theory, especially for the weak version, than for spatial assimilation.

Introduction

With populations increasing due to immigration and urbanization, European urban regions have become much more ethnically diverse, socioeconomically unequal, and spatially segregated versus in previous decades (Maloutas and Fujita Citation2016; Tammaru et al. Citation2016). Segregation is seen as undesirable, being considered an important factor inhibiting social integration, creating parallel societies, and even threatening the social cohesion of European societies (Søholt and Lynnebakke Citation2015; Phillips Citation2010). At the heart of political rhetoric concerning ‘breaking down segregation’ is the idea that immigrants should live closer to natives.

In Sweden, large-scale immigration has been an important factor in economic and social change (Castles, de Haas, and Miller Citation2014). The number of international migrants to Sweden has increased greatly in recent decades; in 2018, 19.1% of the Swedish population was foreign-born. The topics of integration and segregation have become prominent in political discussions and in media and academic debates. Ethnic residential segregation is notable not only in all larger Swedish cities, where more than 25% are foreign-born and an even higher proportion of residents have foreign backgrounds, but also occurs in small and medium-sized cities (Bråmå Citation2006). Segregation has been a concern on the Swedish political agenda since the early 1970s, and a belief in the negative consequences of residing in poverty concentrations (which in Sweden coincide with high concentrations of foreign-background residents) has guided Swedish housing and social mix policies. For example, between 1985 and 1994 a refugee dispersal strategy was in place and in 1998 an area-based integration programme targeting mainly immigrant-dense large housing estates was launched. However, the state goals of achieving (ethnically) mixed neighbourhoods and thus more cohesion in society might not correspond to the actual residential mobility patterns of immigrants.

Spatial assimilation theory states that immigrants as they ‘assimilate’ into their host society, and as their status rises, they attempt to convert their socioeconomic achievements into an improved spatial position (Massey and Denton Citation1985). According to Massey (Citation1985), an improved spatial position is seen as living in neighbourhoods where ethnic natives dominate. However, immigrants might not want to move to such neighbourhoods, as living among co-ethnics could have certain advantages, such as useful contacts for job opportunities (see, e.g. Damm Citation2009; Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003) and extended family in the neighbourhood can offer social support (Pinkster Citation2007). Or even if they do move, the relationship between upward socioeconomic status and mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods could be stronger or weaker for particular groups of immigrants (e.g. arriving with varying levels of human capital and encountering different levels of prejudice, racism, and discrimination), and it could also vary within countries and between contexts. This paper studies immigrants’ mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods in Sweden against the backdrop of counter-segregation policies. The results contribute to our understanding of the variance between immigrant groups and to our scarce knowledge of the importance of the underlying geography. Do socioeconomic achievements facilitate the residential mobility of immigrants to neighbourhoods where Swedish natives predominate? How does this relationship vary across different contexts and immigrant groups in Sweden?

First, to investigate the impact of geography and settlement context, the paper considers the full population of foreign-born individuals who migrated to Sweden from 1990 to 2010. This results in a unique longitudinal panel dataset covering all of Sweden. When studying immigrants’ residential patterns and mobility, analyses are generally restricted to the largest metropolitan areas (Bolt, van Kempen, and van Ham Citation2008; Bolt and van Kempen Citation2010) or to comparing just a few cities (Edgar Citation2014; Logan, Zhang, and Alba Citation2002; Wessel et al. Citation2017; Vogiazides Citation2018), but do not examine other contexts within a country. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first study in the Nordic context that covers an entire country and offers insights into differences between municipality types. This is made possible by using geographically sound coordinate-based individual k-nearest neighbour-defined neighbourhoods, comparable over time, constructed using EquiPop software (Östh Citation2014). By placing individuals in the centre of their neighbourhoods, one can capture a better representation of their residential environment and reduce the risk of biased neighbourhood estimates that are likely due to boundary effects when using administrative units (Östh Citation2014; Östh and Türk Citationforthcoming). Besides municipal context, the context of the initial neighbourhood is also included in this study. Thus, the study provides new findings about the importance of both the absolute (i.e. initial neighbourhood) and relative (i.e. municipal settlement context) geographical contexts. Second, it explores the role of income in spatial integration in different municipal contexts and between different country of origin groups, thus, improving our knowledge about the strong and weak versions of place stratification theory in Sweden.

Third, this study adds to our understanding of how residential mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods varies between different immigrant groups, not only by taking account of region of origin but also by incorporating a category showing refugee status at the time of immigration to Sweden. In the Nordic context, researchers have so far typically only studied certain groups consisting mainly of refugees, for example, whose country of origin is Iran or Iraq (Macpherson and Strömgren Citation2013; Magnusson Turner and Wessel Citation2013) or Somalia (Magnusson Turner and Wessel Citation2013; Skovgaard Nielsen Citation2016).

Theoretical background, previous research, and hypotheses

The first contributions to residential pattern and mobility research came from the Chicago School in the 1920s, for example, the invasion and succession models applying evolutionary logic to urban society (Park et al. Citation1925). Later, influenced by the works of the Chicago School, Massey and others (Massey Citation1985; Massey and Bitterman Citation1985; Massey and Mullan Citation1984; Massey and Denton Citation1985) further developed the spatial assimilation framework, in which the dispersion of immigrants from ethnic concentrations is hypothesized to be driven by socioeconomic mobility and acculturation. An ethnic group tends to start at the bottom in a new country, later accumulating more country-specific human capital and higher income. As the socioeconomic status of the ethnic group rises, the group gains a more favourable spatial position within mainstream society, meaning that it moves out of immigrant-dense areas or ethnic enclaves in the direction of areas having more natives. By moving closer to the native population, immigrants can improve their position in society, since resources and opportunities are unevenly distributed in space in the differentiated urban economy (Massey Citation1985). One could argue that the whole process is about social class position and advancement.

In spatial assimilation theory, which was created in a market-liberal U. S. context, ethnic differences are believed to reflect differences in sociodemographic attributes, i.e. individual characteristics are what determine one’s residential location. Thus, following spatial assimilation theory, it can be expected differences in residential mobility disappear after controlling for socioeconomic attributes and an increase in income has the same impact for all groups regardless of country of origin. However, other approaches emphasize the institutional side, and the constraints on the housing market. The approach that stresses the importance of structural barriers is sometimes called place stratification theory (Alba and Logan Citation1991). According to this theory, different ethnic groups encounter different challenges. For example, immigrants with physical attributes differing from those of the native population may encounter various forms of harassment and discrimination in the housing market (Magnusson Turner and Wessel Citation2013). Such ‘ethnic hierarchies’ are often based on racialized discourses of ‘the other’, referring to physical attributes and/or dress codes. Those immigrants who are culturally similar to the native group are supposed to do better in the host society than are those who are more ‘different’. Certain groups will have fewer chances of succeeding, in both the labour and housing markets. Place stratification theory implies that even when socioeconomic variables are controlled for, the differences between ethnic groups will not disappear. Place stratification theory has two variants: in the strong version of place stratification theory even the most successful members of the minority may live in worse locations than the lowest-status majority-group members; in the weak version the most successful members of the minority-group achieve only just slightly better location outcomes than the lowest-status majority-group members (Logan and Alba Citation1993). In the studies where residential outcome is measured by neighbourhood’s ethnic composition, weak version of the place stratification theory has found more support (e.g. Alba and Logan Citation1993; Pais, South, and Crowder Citation2012; Crowder, South, and Chavez Citation2006). Current study does not compare immigrants’ residential mobility to natives’ mobility, thus, it is difficult to test properly these two versions of place stratification theory. However, comparing immigrant groups and following the weak version of place stratification theory, I expect immigrant groups that are least similar to the natives to pay more to achieve the same residential outcomes as the groups that are most similar to the natives. Strong version, on the other hand, implies that even paying more would not result in the same residential outcomes.

Place stratification theory also notes that contextual differences play a role in residential mobility (Alba and Logan Citation1991). Contextual factors found to be of importance are ethnic composition of a given area, segregation levels, immigrant population size, poverty levels, the home ownership level, and availability of housing (Alba and Logan Citation1991; South and Crowder Citation1998; South, Crowder, and Chavez Citation2005; Pais, South, and Crowder Citation2012). In the European context, the degree of urbanization has found to have a strong effect on neighbourhood quality change after residential mobility, with mobility to rural areas being beneficial to neighbourhood quality (Lersch Citation2013). Thus, it can be hypothesized that mobility to native-dominated neighbourhoods is more common outside of bigger urban areas.

The spatial assimilation and place stratification theories have inspired numerous studies in the European countries as well. In Germany, neither theories have found full support (e.g. Lersch Citation2013), in the Netherlands, the spatial assimilation theory has in some cases found support (e.g. Zorlu Citation2009) but in other cases not (e.g. Bolt and van Kempen Citation2003). Spatial assimilation in the Nordic countries has mainly been studied from three perspectives: moving away from distressed immigrant-dense neighbourhoods (Vogiazides Citation2018; Macpherson and Strömgren Citation2013), moving to a neighbourhood considered higher status in socioeconomic terms (Wessel et al. Citation2017; Magnusson Turner and Wessel Citation2013), and moving into homeownership as an indicator of integration (Magnusson Turner and Hedman Citation2014; Kauppinen, Andersen, and Hedman Citation2015; Kauppinen and Vilkama Citation2016). Most of these studies find some limited support for the spatial assimilation thesisFootnote1 (although Wessel et al. (Citation2017) find a complete lack of spatial integration), but the studies that consider differences between immigrant groups find that variation between groups is insufficiently explained by socioeconomic attributes. This indicates support for place stratification theory over the relatively simplistic view of spatial assimilation theory (e.g. Vogiazides Citation2018). Other studies that have not specifically looked into spatial assimilation or place stratification, but rather the reproduction of neighbourhoods via residential mobility, have found that immigrants do move away from distressed areas and that this mobility is socioeconomically selective (Andersson and Bråmå Citation2004; Andersson Citation2013; Bråmå and Andersson Citation2005; Bråmå Citation2008). However, there is less research on mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods. How many of the out-movers from these immigrant neighbourhoods, which are typically situated at the bottom of the housing hierarchy, move to neighbourhoods dominated by the native population, and thereby conform to what Massey (Citation1985) defined as spatial assimilation?Footnote2

Spatial assimilation and place stratification are essentially complementary, assuming that the goal of migrants is to live closer to natives. In contrast, the ethnic preference (or ethnic enclave) perspective argues that migrants may prefer to live close to co-ethnics (Clark Citation1992) and that ethnic concentrations can have positive effects for their residents (Zhou Citation1992; Portes and Bach Citation1985). Bolt, Burgers, and van Kempen (Citation1998) identified three possible advantages of ethnic concentrations: social and cultural advantages (i.e. social networks enable their members to derive benefits and support from one another), economic advantages (i.e. ethnic networks can give ethnic enterprises a competitive edge over other businesses), and political advantages (i.e. possible political influence at the local level). Moreover, kinship ties are known to tie minorities to particular neighbourhoods (Zorlu Citation2009) as extended family networks can offer social support (Pinkster Citation2007). In addition, ethnic capital spillover effects have been found to be stronger when neighbourhoods are ethnically homogenous (Borjas Citation1998).

In the Scandinavian context, several studies have found that ethnic clustering can have some positive effects on income (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2014; Musterd et al. Citation2008; Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003; Damm Citation2009), although the results are not straightforward. For example, the direction and magnitude of effects can vary by gender, neighbourhood employment context (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2014, Citation2018), quality of the ethnic concentration in terms of income in the enclave (Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003), and length of stay in the enclave (Musterd et al. Citation2008). In Sweden, ethnic enclaves have also been studied from the perspective of the self-employment of refugees, and results indicate that living close to co-ethnics increases the probability of self-employment (Andersson Citation2018). However, the success of this strategy should not be taken for granted, and many self-employed display poor economic outcomes, having weaker income trajectories in the long term than do those employed on the formal market (Andersson Citation2018). In addition, Molina (Citation1997) found no support in the Swedish context for the belief that minorities strive to live in proximity to co-ethnics. She argued that they have similar housing aspirations as natives and that the structural reasons are the ones that are central to explaining residential segregation. It is therefore important to investigate what individual socioeconomic factors facilitate immigrants’ mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods, but to do this in a context-sensitive way, since different structural barriers might confront different groups. This paper does this by adding to our knowledge of the role of income, differences between groups, and of contextual differences between initial neighbourhoods and settlements within Sweden.

Swedish context

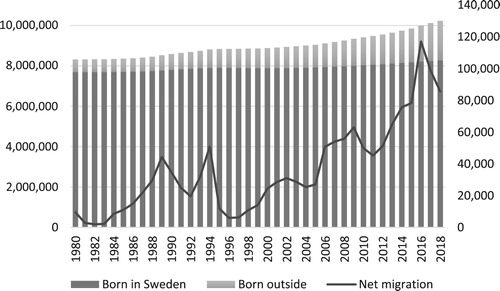

To understand concurrent trends in the migration and spatial distribution of migrants in Sweden, a brief historical description is needed. Between 1850 and 1930, emigration from was greater than immigration to Sweden. The years of the Great Depression saw considerable return migration from the U. S. A., and later, during the war years, many migrants from the occupied neighbouring Nordic countries and from the Baltics and Germany came to Sweden. This led to net immigration. During the early Cold War (1950s and 1960s) and with the establishment of a common labour market and free mobility within the Nordic countries, many migrants arrived from Finland, but also from other European countries (Yugoslavia, Italy, and Greece were three important non-Nordic migration origin countries at the time). During the later Cold War (1960/70s–1990), labour migration became more restricted, being replaced with refugee migration and family reunification. Finally, the contemporary migration situation (since 1990) has been characterized by strong variation in the number of migrants and by a tremendous increase in the number of migrants from non-European countries. Numerically, migrants from former Yugoslavia dominated immigration during the early parts of the contemporary phase, while Syria, Iraq, and Somalia are important countries of origin for more recent migration. Between 1980 and 2018 the Swedish population grew from roughly 8.3 million to 10.2 million inhabitants. A substantial amount of this increase (around 1.3 million) can be attributed to net-migration (). In 2018, 19.1% of Swedish population was foreign-born.

The recessions of the mid 1970s and early 1990s and the ensuing restructuring of the labour market negatively affected employment opportunities, especially for newly arrived immigrants, who by that time were largely refugees (Holmqvist and Bergsten Citation2009). Due to the housing shortage, it was also difficult to find adequate housing for the new arrivals, leading to the concentration of immigrants in certain housing estates in the outskirts of Sweden’s largest cities (Holmqvist and Bergsten Citation2009). The increasing geographical concentration of immigrants and increasing unemployment rates triggered a belief that ethnic integration failure is linked to residential segregation. Since residential segregation, and especially ethnic segregation, is seen as a problem in the Swedish debate, many desegregation and social mixing policies have been launched since the 1970s, as in other European countries. Mixed neighbourhoods are believed to enhance the living conditions and life chances of their residents, promoting more stable and cohesive communities (Bolt, Phillips, and Van Kempen Citation2010). The goal of early policies was to counteract socioeconomic rather than ethnic segregation, and this goal has remained a constant (Holmqvist and Bergsten Citation2009). However, the socioeconomically deprived areas in Sweden coincide with high concentrations of foreign-born individuals (Andersson Citation2013). Social mix was supposed to be achieved through new construction and renewal to obtain a more varied housing stock, while not being imposed on anyone and not targeting specific groups, to avoid discrimination and violation of the free-choice principle (Andersson, Bråmå, and Holmqvist Citation2010). Compared with social mix policies in other countries, the aim of the Swedish policy has been not only to change disadvantaged neighbourhoods, but to create cities that are mixed in their entirety (Bergsten and Holmqvist Citation2013). However, the indirectness of the measures, the withdrawal of state production subsidies, and the voluntary nature of policy implementation (i.e. each municipality can implement the policy in its own way) has made social mix policy in Sweden weak and difficult to implement (Andersson, Bråmå, and Holmqvist Citation2010).

Two other housing programmes have similarities with the social mix strategies applied in other countries, and warrant mention here. Between 1985 and 1994, the ‘All of Sweden’ strategy was imposed on refugee immigrants. This forced dispersal strategy meant that newly arrived refugees were not free to locate where they wanted until receiving permanent residence permits, but were placed in municipalities in different parts of the country.Footnote3 The strategy was supposed to avoid further concentration in the metropolitan areas and improve the labour market integration (Holmqvist and Bergsten Citation2009). Another integration programme launched in 1998 was an area-based policy targeting ‘exposed’ areas (mainly immigrant-dense large housing estates) in the three largest cities of Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö. The emphasis of this policy was on employment and education, rather than housing (Holmqvist and Bergsten Citation2009; Andersson Citation2006).

It is important to note that in Sweden, as elsewhere, the variation in integration processes between different immigrant groups and cohorts is often not recognized (Andersson Citation2011). However, ‘ethnic hierarchies’ that cannot be explained with reference to the different socioeconomic characteristics of immigrants also exist in Sweden, and discrimination against ethnic minorities occurs in both the Swedish housing and labour markets (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Carlsson and Eriksson Citation2014; le Grand and Szulkin Citation2002). Ethnic hierarchies are similar in the labour market and in terms of residential segregation: immigrant groups from neighbouring countries are at the top, with high employment and low segregation rates, while refugee immigrants from Western Asia (e.g. Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq) and Africa are found at the bottom; immigrants from Eastern European and Latin American countries are considered to occupy an intermediate position (Andersson, Bråmå, and Holmqvist Citation2010; Andersson Citation2011, Citation2013; Bråmå and Andersson Citation2010). Similar differences between immigrant groups have also been observed in homeownership rates (Magnusson Turner and Hedman Citation2014).

Data and methods

Study population

The study population is derived from the PLACE database located at Uppsala University. PLACE is based on various administrative longitudinal registers containing annual discrete statistics for all residents in Sweden between 1990 and 2010. All individuals are geo-coded (100 × 100-m coordinate grid), and annual changes in residential addresses are known throughout the whole period.

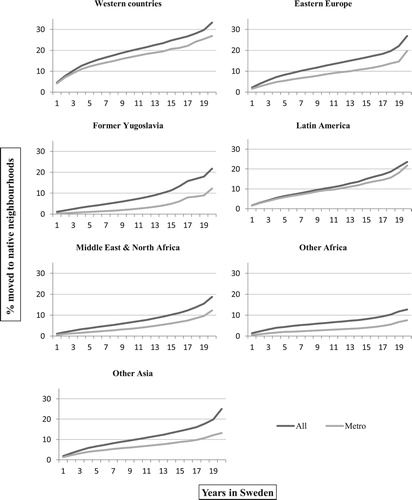

The panel dataset used in the analysis contains yearly information on every foreign-born individual who was at least 16 years old when migrating to Sweden, who migrated to Sweden between 1990 and 2010, and lived in Sweden at least one-year. The analytical unit for the study is individuals, because households cannot be easily followed through time. This results in a longitudinal dataset of 834,665 individuals. Around 40% of all the individuals did not move at all (change coordinates) from their first residential location during the time they were represented in the data (). This study is concerned with moves to native-dominated neighbourhoods which are operationalized in this study as neighbourhoods that have a higher share of natives (i.e. Swedish-born people) than the country as a whole at the time of relocation (hereinafter ‘native-dominated neighbourhoods’). Around 45% of immigrants (23.4% in metropolitan municipalities) were living in a native-dominated neighbourhood already the first year they arrived to Sweden (), these individuals are excluded from the survival analyses.

Table 1. Number of individuals migrating to Sweden in four time periods and their residential mobility (all municipalities and metropolitan municipalities).

In the dataset, every person is represented every year until she or he moves to a native-dominated neighbourhood (‘the event’). After the event, the individual is eliminated from the dataset, meaning that only one event per person is examined. In the case of immigration to followed by emigration from Sweden, and then repeated immigration to the country, only the first period is observed, since it indicates the pioneer experience.Footnote4 Individuals are allowed to enter and exit (i.e. move away from Sweden or die) the dataset at any time, resulting in an unbalanced panel in which some groups that migrated earlier are represented for longer than are others.

The longitudinal nature of the data enables the researcher to measure the variables every year. Since spatial assimilation theory states that socioeconomic advancement translates into residence near the native population, several time-varying explanatory variables capturing socioeconomic status (i.e. educational level, employment status, and disposable incomeFootnote5) are used. Variables for gender, age, and position in the household are used as demographic control variables. Housing tenure variables would have been useful, but cannot be used here, because housing statistics were missing for several of the studied years.Footnote6 It would also have been valuable to include a code for cohabitation with a Swedish-born partner, but in the registry data, cohabitation is only known for people who are married or have a child together. Since cohabitation without being married is common in Sweden, the data would not be reliable in all cases, resulting in overrepresentation of single people, so partner information is omitted. Since family ties are important determinants of residential mobility, a dummy variable showing whether individual’s mother lives within 5 km (Cartesian distance) was included in the models.Footnote7 Descriptive statistics and variable categories are listed in Appendix 1.

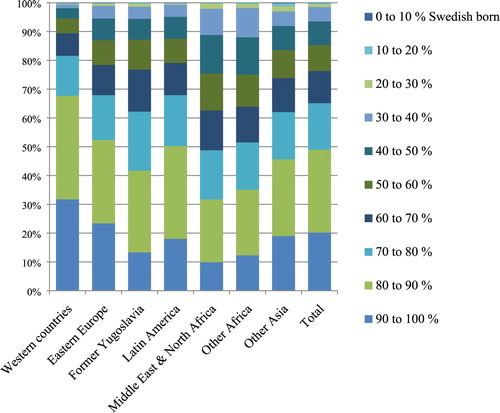

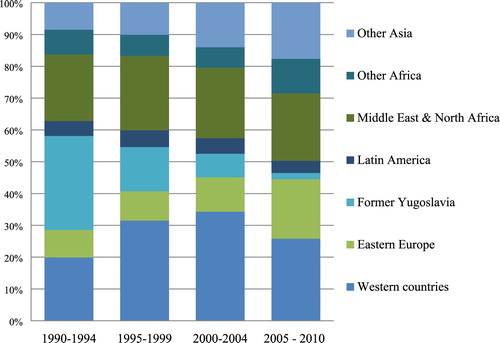

Since place stratification theory emphasizes that assimilation also depends on ethnicity, the analyses focus on different immigrant groups. Swedish registers do not contain self-classified ethnicity information, so immigrants were grouped into seven categories by country of birth: Western countries,Footnote8 Eastern Europe, former Yugoslavia, Latin America, Middle East and North Africa, other Africa, and other Asia. The biggest changes over time are seen in migrants from former Yugoslavian countries: during the 1990–1994 period, they accounted for almost 30% of all immigrants, while during the 2000–2005 period, they constituted under 2% of all immigrants (). Migration from Eastern European and other Asian countries has increased the most over time. The analysis also takes account of whether the individual arrived in Sweden from a country at war at time t; this measure indicates refugee status at the time of entry.Footnote9 Refugees have lower employment rates and have been increasingly concentrating in certain housing estates in the outskirts of the largest cities. In addition, during the 1985–1994 period, the ‘All of Sweden’ refugee dispersal policy was in place.

Figure 2. Share of foreign-born migrating to Sweden in four time periods, grouped by country of birth.

The type of municipality of residence is also included in the analysis, since contextual differences have been found to affect residential patterns (Alba and Logan Citation1991; Pais, South, and Crowder Citation2012). In Sweden, municipalities are the core administrative units at the local level and are responsible for most services that affect integration and residential mobility. Sweden has 290 municipalities categorized by size, urban function, and economic activity into 10 types: metropolitan municipalities, suburban municipalities, large cities, suburban municipalities near large cities, commuter municipalities, tourism and travel industry municipalities, manufacturing municipalities, sparsely populated municipalities, municipalities in densely populated regions, and finally municipalities in sparsely populated regions. This classification of municipalities follows the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) classification (SKL Citation2011).

The initial neighbourhood of residence of immigrants arguably plays a role in their integration trajectories (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2018; Skovgaard Nielsen Citation2016). For example, the port-of-entry neighbourhood’s ethnic composition affects the immigrant’s employment prospects (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2018), and the parental neighbourhood’s ethnic composition affects the home-leaver’s future neighbourhood’s ethnic composition (Skovgaard Nielsen Citation2016). A variable capturing the share of Swedish born in the immigrant’s initial neighbourhood as of the year of arrival is therefore included in the analysis. illustrates how the initial neighbourhood’s ethnic composition varies across immigrant groups. I hypothesize that groups starting in more immigrant-dense neighbourhoods take longer to move to native-dominated neighbourhoods as spatial assimilation is a gradual process. For example, in , note the case of individuals born in Middle Eastern and African countries; around 25% of individuals in these two groups start in neighbourhoods where the share of foreign-born is 50% or higher.

Analytical strategy

An important part of this study is the spatial unit used in the analysis: individual bespoke neighbourhoods instead of available administrative geographical units. In the Swedish context, Small-Area Market Statistics (SAMS) spatial units are usually used by researchers studying immigrants’ spatial mobility (Macpherson and Strömgren Citation2013; Vogiazides Citation2018; Bråmå Citation2008). However, using SAMS units when conducting research on the entire country of Sweden can be problematic because the size and population density of SAMS units differ greatly between municipalities. Moreover, the bespoke neighbourhood approach allows a micro-scale analysis that is comparable over time. From every individual residential coordinate-pair, a neighbourhood based on counts of the k-nearest neighbours is created using EquiPop software (Östh Citation2014). The size of each individualized neighbourhood was chosen to be the 500 nearest neighbours, as this size has been successfully employed in several studies in the Swedish context (see for instance Hedman et al. Citation2015; van Ham et al. Citation2014). Using these neighbourhoods based on counts of individuals gives a better representation of the residential environment surrounding each individual. By placing the individual in the centre of their neighbourhood, the risk of biased neighbourhood estimates caused by boundary effects can be reduced (Andersson and Musterd Citation2010; Johnston et al. Citation2005; Östh, Malmberg, and Andersson Citation2014). EquiPop uses the k-nearest neighbour approach to create contextual variables for each individual, variables that will be identical for all individuals living in the same 100 × 100-m grid cell. For the analysis, the share of foreign-born in each neighbourhood for the entire population of Sweden was calculated for every year between 1990 and 2010.

As this study is specifically interested in immigrants’ spatial mobility towards the native-dominated areas, and in the time that it takes them to move to these areas, a treatment variable consisting of two parts was created for this study. First, a residential move to a native-dominated neighbourhood is operationalized as residential mobility into a neighbourhood (k = 500) that has a higher share of natives than does the country as a whole in a given year. Some studies use neighbourhood quality and moving to higher-status neighbourhoods as a proxy when studying spatial assimilation, but in the Swedish context, residential closeness to natives is arguably a better proxy. Nordic welfare state policies and planning are intended to equalize the quality of public services (e.g. schools and kindergartens) across urban districts, historically resulting in limited differentiation across neighbourhoods (Wessel et al. Citation2017). Accordingly, a treatment variable capturing movement into native-dominated neighbourhoods was created using the following procedures:

From each residential coordinate i, determine the share of foreign-born among the nearest 500 neighbours in each year, 1990–2010.

Calculating the national average: Calculate the mean number of foreign born in the 500-nearest-neighbour neighbourhoods in each year, 1990–2010. To relax the definition and make the measure less crude, while still resulting in native population-dominated neighbourhoods, half a standard deviation is added to the meanFootnote10 (see Appendix 2 for the treatment variables per year); accordingly, the share of foreign born in neighbourhoods ranges from 13.8% to 23.2%.

Categorize each location i at time t as: 1 – having a share of foreign-born less than or equal to the national average plus ½ st. dev. (among the 500 nearest neighbours to i); or 0 – having a share of foreign- born greater than the national average plus ½ st. dev. (among the 500 nearest neighbours to i).

Mobility towards a native-dominated neighbourhood happens only when an individual changes residential coordinates, i.e. moves.

Since immigrants concentrate in metropolitan areas where segregation is greater and housing more expensive, it is important to have a separate treatment variable for all of Sweden and for the metropolitan municipalities (i.e. Sweden’s three largest cities: Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö; see Appendix 2). The second part of the treatment variable measures time in years elapsed from the immigration to Sweden until the move to a native-dominated neighbourhood (value 1 of the treatment variable).

The aim of this paper is to model the differences in residential mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods between immigrant groups and between municipalities. To achieve this, first, proportion of immigrants moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods depending on the length of time elapsed from immigration to Sweden is presented by country of origin groups.

Second, discrete time complementary log–log regression is used to estimate how mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods varies not only between subgroups of migrants and between socioeconomic classifications, but also between municipalities and depending on initial neighbourhood context. Exponentiated coefficients of the discrete time complementary log–log model can be interpreted as hazard ratios, which are measures of the potential for an event to occur at time t, given that it has not yet occurred. Hazard ratios show the association between predictors and the outcome: if the hazard ratio is less than 1, then the predictor is associated with decreased likelihoodFootnote11 of the event happening, and if the hazard ratio is greater than 1, then the predictor is associated with increased likelihood. Time was specified in the regression framework as natural logarithm of time. The model was also estimated with time specified as squared, cubical, and fully non-parametric (dummies for each one-year period). Model fit was best for natural logarithm of time and time dummies specifications, however, since there was not much difference in model fit and the coefficients between these two specifications, a model with natural logarithm of time (using less degrees of freedom) was chosen. Since differences between municipalities are expected, the analysis is run separately for all municipalities in Sweden and for the metropolitan municipalities.

Results

In this section, first, an overview of the residential patterns based on neighbourhoods of the 500 nearest neighbours is presented. This is followed by the presentation of residential mobility of different immigrant groups to native-dominated neighbourhoods depending on how much time has elapsed since migration to Sweden. The last subsection presents the results of the discrete time complementary log–log model, indicating what individual characteristics and geographical contexts facilitate or hamper mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Overview of the residential patterns in Sweden

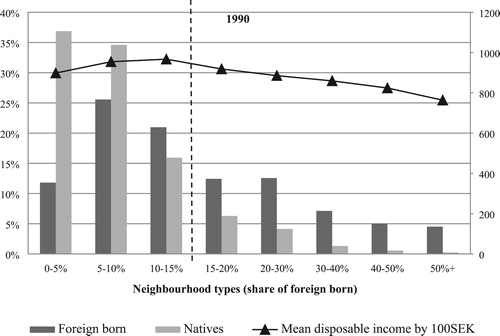

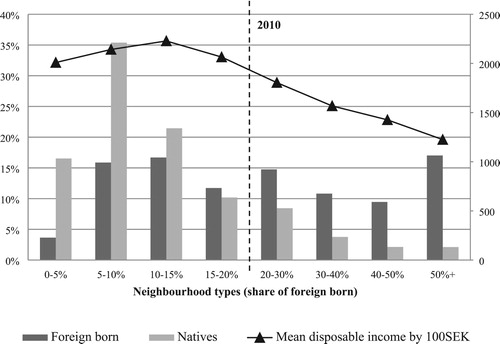

To explain the choice of definition of a native-dominated neighbourhood, an overview of the residential patterns of the native and foreign-born populations is helpful. From 1990 to 2010, the foreign-born population grew substantially, accompanied by the greater clustering of immigrants. In both 1990 and 2010, more than 80% of native Swedes lived in neighbourhoods categorized as native-dominated neighbourhoods in this study (see and ). In 1990, more than half of the foreign-born population lived in native-dominated neighbourhoods, but in 2010 less than half did so. Also, the distribution of income across neighbourhoods has become much more unequal: in 2010 the most immigrant-dense neighbourhoods had 1.7 times lower mean disposable income than did the predominantly native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Mobility to native-dominated neighbourhood

To describe the differences over time between the countries of origin groups in residential mobility to native-dominated neighbourhoods, life tables were computed. Cumulative failure rates show that mobility into a native-dominated neighbourhood is quite rare, especially in the metropolitan municipalities: overall only 21.0% of the studied individuals in Sweden as a whole moved to a native-dominated neighbourhood during 1990–2010 and only 13.5% of the individuals in the metropolitan cities. There is considerable variation across the immigrant groups, however. The groups represented in the dataset that have the largest shares of individuals who moved to a native-dominated neighbourhood are migrants from Western countries and Eastern Europe (). In metropolitan municipalities, these groups are from the Western, Latin American, and Eastern European countries. The groups that moved to native-dominated neighbourhoods the least are in both cases migrants from other African countries and from Middle Eastern and North African countries. These results indicate that groups that on average are economically weaker are moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods to a lesser extent than are others. These two groups also start from more immigrant-dense neighbourhoods than do other groups ().

The discrete time regression analysis

Previous sections have established that there is variation between immigrant groups in both time and propensity to move to a native-dominated neighbourhood. In this section of the analysis, I ask whether the variation in time and propensity can be explained by variation in the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of individuals and their residential locations in Sweden. The regressions were limited to people over 19 years old, because younger individuals are typically at school and have no declared income.

shows the results of four estimated discrete time complementary log–log models: models one and two include all immigrants in Sweden and models three and four are geographically restricted models including only immigrants living in Sweden’s metropolitan cities, i.e. Stockholm, Malmö, and Göteborg.Footnote12 Models one and three include only the country of birth and time variables, whereas models two and four include other variables as well. The estimates specify the predicted change in moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood for a unit change in the covariates.

Table 2. Results of discrete time proportional hazard model (complimentary log–log regression) explaining entry into a native-dominated neighbourhood: models 1 and 2 are based on all municipalities in Sweden, models 3 and 4 on metropolitan municipalities (i.e. Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö).

Time variable in the models shows that the baseline hazard decreased with elapsed time. Models one and two solely estimate the effects of immigrant group on the hazard ratio for moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood. There is a significantly lower tendency to move for all immigrant groups compared with immigrants from Western countries. The tendency to move is even lower in the metropolitan municipalities, probably because of the high cost of housing in the metropolitan areas and because the proportion of native-dominated neighbourhoods is greater outside the metropolitan areas where there are fewer immigrants. There are also differences in the hazard ratios between the groups: 0.426 times for the Other Africa group (0.270 in the metropolitan cities) and 0.732 times for the Eastern European group (0.633 in the metropolitan cities) versus the Western country group. In the metropolitan municipalities, the hazard ratio (0.757) most similar to that of the Western countries is for the immigrant group from Latin America.

Models two and four indicate that after controlling for all other variables in the models, all immigrant groups retain their lower tendency to move compared with immigrants from Western countries. In metropolitan municipalities, the variation in hazard ratios between the immigrant groups also remains relatively unchanged. However, in both models, the gap between immigrants from Western countries and other immigrant groups decreases when socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are controlled for. After controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors, the most similar hazard ratios for moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood versus immigrants from Western countries are for people from Eastern Europe and Latin America (both in all municipalities and in metropolitan municipalities). The lowest hazard ratios in model two for all municipalities are for Other Africa and Middle East and North Africa, whereas in the metropolitan municipalities, the lowest hazard ratios are for the Other Africa and former Yugoslavia groups. Being a refugee significantly decreases one’s likelihood of moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood, and more so in the metropolitan cities.

Both in all municipalities and in metropolitan municipalities, having higher levels of education, higher disposable income, being single, and being employed increase the tendency to move to a native-dominated neighbourhood. The estimates for education and employment, which are even stronger in the metropolitan areas, therefore support spatial assimilation theory. The variable for the context of the initial neighbourhood shows the expected results: the higher the share of foreign-born in the initial neighbourhood, the lower the likelihood of moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood. The housing market position at the beginning of the housing career in Sweden plays a role in possible future residential mobility trajectories. As expected, family ties in the neighbourhood, measured as mother’s residential location closer than 5 km, lower the likelihood of moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood.

The type of municipality of residence variable indicates that mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods is largely a matter of scale. The hazard ratios for moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods are many times greater in municipalities in sparsely populated regions than in the metropolitan regions of Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö. Types of municipalities located relatively near metropolitan areas (i.e. suburban municipalities) and large cities have hazard ratios more similar to those of metropolitan regions.

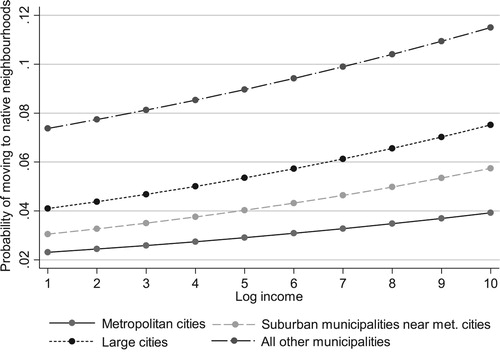

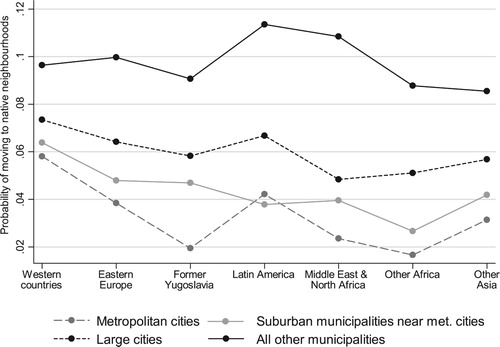

In order to better assess which minorities are able to move to native-dominated neighbourhoods and where this process is most evident a model including interaction terms between (1) income and municipality types, (2) country of origin and municipality types, and (3) country of origin and income (also run separately for metropolitan municipalities) was estimated. For the model with interactions, municipality types were divided into 4 categories: metropolitan cities, suburban municipalities near metropolitan cities, large cities, and all other municipalities were grouped into one category. Only about 15% of the study population lives outside of the first three categories (Appendix 1). The results of the interactions are shown using predicted probability plots.

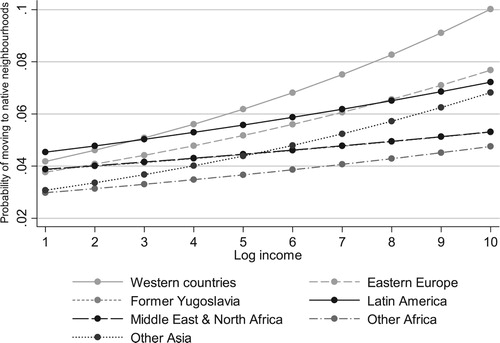

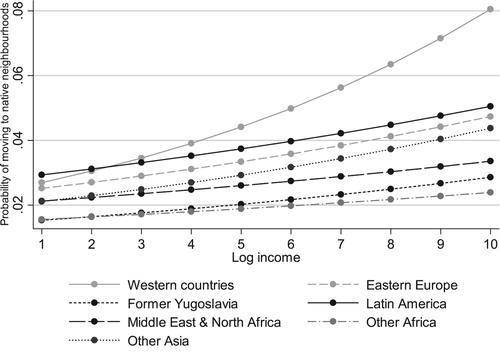

shows that moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods is much easier outside the major economic hubs in Sweden: even for groups with the highest disposable income the probability to move to native-dominated neighbourhoods is lower in the major economic hubs than for groups having the lowest income outside these areas. The effect of income increase on residential mobility is smallest in the metropolitan cities and largest in large cities and all other municipalities (). shows that the same pattern among municipality types exists for all country of origin groups: for all the groups the probabilities to move to native-dominated neighbourhoods are the lowest in the metropolitan cities and the highest outside the biggest cities. For some groups the differences in probabilities depending on the municipality types are smaller (i.e. Western countries), for some larger (i.e. Middle East & North Africa) ().

Figure 7. Predicted probabilities of municipality types across income levels explaining residential mobility to native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Figure 8. Predicted probabilities of municipality types across immigrant groups explaining residential mobility to native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Table 3. Interaction effects in average marginal effects between disposable income and municipality type on the likelihood of moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Interactions with country of origin and income explain better which migrant groups are able to move to native-dominated neighbourhoods. The effect of income increase is biggest for migrants from Western, Eastern European and Other Asian countries; the effect is smallest for categories Former Yugoslavia and Other Africa (). For all immigrant groups the effect is smaller in metropolitan cities than in all municipalities, but the biggest differences between metropolitan cities and all municipalities are seen for categories Other Africa, Eastern Europe, and Other Asia (). Thus, in terms of residing in native neighbourhoods, living in metropolitan cities is especially harmful for these three groups.

Table 4. Interaction effects in average marginal effects between disposable income and country of origin on the likelihood of moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods.

Moreover, interactions with country of origin and income can be used to differentiate between the strong and the weak place stratification theories. Since the residential mobility of the majority population is not studied in this paper, comparing other immigrant groups to migrants from Western countries is the best option to shed some light on how the strong and the weak place stratification theories might carry out in Sweden. Residential mobility in Sweden as a whole follows the weak version of place stratification theory: to reach the same probabilities of moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods as the poorest groups of the Western countries, all other groups need much higher incomes (). In metropolitan municipalities, it is also the case for most of the immigrant groups (). However, Other African group cannot reach the same probabilities even with the highest incomes, thus, supporting the strong version of the place stratification theory.

Conclusions and discussion

The aim of this paper is to extend research on immigrants’ residential mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods. The paper fills a gap in spatial assimilation research by looking at the entire country as well as different municipal contexts within Sweden. The paper also adds more nuanced information on the role of ethnic origin and income. By employing discrete time survival models, the study finds that mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods in Sweden depends not only on individual socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, but also on country of origin and geography. The paper finds some support for spatial assimilation theory, in that a better socioeconomic situation (i.e. being employed, having higher income, and having higher levels of education) increases the likelihood of moving to a native-dominated neighbourhood. The notion that a higher socioeconomic position facilitates spatial assimilation is consistent with other studies conducted in a Swedish context (Magnusson Turner and Hedman Citation2014; Macpherson and Strömgren Citation2013; Bråmå Citation2008; Vogiazides Citation2018). Adding to previous studies, the analysis clearly shows that mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods outside the metropolitan cities is much easier than such mobility within them, even when the labour market outcomes in terms of income are often worse outside the biggest cities. In metropolitan municipalities, a smaller share of people start in native-dominated neighbourhoods, and for those who do not, mobility towards a native-dominated neighbourhood is rarer than in other municipalities. This is also in line with earlier research showing that the spatial isolation of minorities in Sweden is considerably greater in metropolitan areas (Östh, Clark, and Malmberg Citation2015; Östh, Malmberg, and Andersson Citation2014). Economic segregation and social polarization in Swedish metropolitan cities is on the rise (Andersson and Kährik Citation2015; Hedin et al. Citation2012), and the current study shows that increasing economic segregation is making spatial integration in densely populated areas very difficult, especially for marginalized groups. A potential explanation is that the cost of moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods in the metropolitan areas is excessive – the housing costs and the size of the labour market there simply do not favour the poor. One thing that facilitates the process is starting from a neighbourhood where more natives live; accordingly, the ethnic composition of the port-of-entry neighbourhood clearly matters for integration trajectories (Andersson, Musterd, and Galster Citation2018).

Besides the spatial contextual findings, this study further provides support for the weak version of the place stratification theory as it finds that all groups need to have much higher levels of income to reach the same levels of probability of moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods as the poorest migrants from Western countries. Further, this paper detects the existence of ethnic hierarchies when it comes to moving closer to the native population, supplementing previous findings regarding ethnic hierarchies in other contexts (Andersson Citation2011, Citation2013; Bråmå and Andersson Citation2010; Magnusson Turner and Hedman Citation2014; Andersson, Bråmå, and Holmqvist Citation2010). The groups that can be considered culturally and visually the most similar to native Swedes (e.g. those from Western countries, Eastern European countries, and Latin American countries) are more likely to live closer to the native population. At the bottom of the ethnic hierarchy in this study are people from Middle Eastern and African countries. Earlier studies have found that people with Arabic/Muslim-sounding names are clearly discriminated against on the Swedish housing market (Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt Citation2010; Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008). Moreover, many people from these geographical areas have entered Sweden as refugee migrants, which is another characteristic associated in the current study with decreased likelihood of mobility towards native-dominated neighbourhoods.

As many other studies have concluded, the relationship between social integration and residential context is very complex. My results suggest that future studies should put more emphasis on the local context. On one hand, the relationship between segregation and integration is arguably not as strong as many assume and policies intended to promote mixed neighbourhoods probably do little to enhance social integration (e.g. labour market integration) in society (Musterd Citation2003). The general standpoint in Sweden is that poor labour market integration is responsible for the residential segregation of minority groups (Andersson Citation2006), and indeed the present results indicate that employment increases the likelihood of living closer to the native population everywhere in Sweden. On the other hand, this study finds that economic motives for moving to native-dominated neighbourhoods are not uniform across local contexts. In metropolitan regions, income level plays a smaller role in neighbourhood outcomes than in other municipalities; it could be, rather, it is a success in progressing in other life domains, such as labour market participation and strong educational attainment that translates into spatial integration. In addition, financial gains can easily be transferred to one’s home country and may not materialize in spatial integration at all if people do not feel they belong and do not engage with the structures of society (e.g. employment and education). Wessel et al. (Citation2017) found that in Stockholm upward earnings mobility does not translate into upward spatial mobility, and they argued that welfare generosity decreases the speed of spatial assimilation. In the Scandinavian welfare state, there is less to gain from moving to better neighbourhoods (Magnusson Turner and Wessel Citation2013). Thus, sometimes the individual material advancement may diverge from the policy goal of creating mixed cities. However, this should not be seen as an argument for ethnic segregation; rather, the results indicate that the relationship between socioeconomic advancement (especially upwards earnings mobility) and spatial location is more complicated than the assimilation theory states, depending greatly on the geographic location – both relative (in terms of metropolitan vs. other area) and absolute (in terms of initial neighbourhood context) – and varying between immigrant groups. Future research could benefit from more detailed analyses of different contexts and immigrant groups. For example, in future studies, the treatment variable could be formulated in an even more context-sensitive way. First, treatment variable could include neighbourhood’s socioeconomic status to measure upward mobility. Second, as immigrant density in a neighbourhood can be perceived differently depending on the local context (e.g. share of immigrants on a local scale), a treatment variable that takes into account different local contexts could provide useful insights. It would also be useful to incorporate more information on kinship ties and housing market information (e.g. rental share and available dwellings) about the studied areas, since housing accessibility and availability play an important role in residential mobility (South and Crowder Citation1998). Moreover, as this study has demonstrated, the initial neighbourhood context affects possible future residential mobility trajectories, so additional neighbourhood contextual variables could be implemented for a more nuanced analysis.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Roger Andersson, John Östh, Anneli Kährik and Lina Hedman for their valuable advice. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Kati Kadarik http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5701-2622

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 However, stronger support has been found for spatial assimilation theory in the Danish context (Skifter Andersen Citation2010; Skovgaard Nielsen Citation2016; Skifter Andersen Citation2015).

2 To the author’s knowledge, only one other study (Bråmå Citation2008) has examined moves to native Swedish neighbourhoods.

3 The labour market effects of the ‘All of Sweden’ strategy were mostly negative, and most of the relocated migrants moved to the larger urban areas as soon as they received their permits (Åslund, Östh, and Zenou Citation2010).

4 It is possible that individuals may have lived in Sweden before 1990, but emigrated from and then returned to Sweden after 1990. This information is unknown because the dataset starts in 1990, so all prior movements are unknown.

5 Individual subcomponent of household disposable income; specified in SEK 100s.

6 At the time of planning and compiling the dataset, housing data in the PLACE database were available only for every fifth year during the 1990s and every second year during the 2000s.

7 It is important to note that because the dataset consists only of individuals who have been born abroad, mother’s residential coordinates are known only for 5.5% of the cases in the dataset.

8 This category includes Western European, North American, and Oceanian countries.

9 A new variable is now available that indicates the reason for permission to stay in Sweden, but at the time of dataset compilation it was unavailable.

10 As a robustness check, the analysis was also run using the national average and the national average minus 1/2 standard deviation. Both models produced results similar to those of using the national average plus 1/2 standard deviation.

11 Because survival analysis is common in medical research, the term often used is ‘risk’; however, in this paper ‘likelihood’ is more suitable.

12 Separate models for ‘the most urban municipalities’ (including metropolitan cities, suburban municipalities near metropolitan cities, and large cities) and for ‘the most rural municipalities’ were set up as well, but as their results are very similar to those of the model that includes all municipalities, they are not shown here.

References

- Ahmed, A. M., L. Andersson, and M. Hammarstedt. 2010. “Can Discrimination in the Housing Market be Reduced by Increasing the Information About the Applicants?” Land Economics 86 (1): 79–90.

- Ahmed, A. M., and M. Hammarstedt. 2008. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 362–372. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004.

- Alba, R. D., and J. R. Logan. 1991. “Variations on Two Themes: Racial and Ethnic Patterns in the Attainment of Suburban Residence.” Demography 28 (3): 431–453. doi:10.2307/2061466.

- Alba, R. D., and J. R. Logan. 1993. “Minority Proximity to Whites in Suburbs: An Individual-Level Analysis of Segregation.” American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1388–1427. doi:10.1086/230193.

- Andersson, R. 2006. “‘Breaking Segregation’ – Rhetorical Construct or Effective Policy? The Case of the Metropolitan Development Initiative in Sweden.” Urban Studies 43 (4): 787–799. doi:10.1080/00420980600597608.

- Andersson, R. 2011. “Exploring Social and Geographical Trajectories of Latin Americans in Sweden.” International Migration, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00679.x.

- Andersson, R. 2013. “Reproducing and Reshaping Ethnic Residential Segregation in Stockholm: The Role of Selective Migration Moves.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 95 (2): 163–187. doi:10.1111/geob.12015.

- Andersson, H. 2018. “Immigration and the Neighbourhood: Essays on the Causes and Consequences of International Migration.” PhD Thesis, Uppsala University, Sweden.

- Andersson, R., and Å. Bråmå. 2004. “Selective Migration in Swedish Distressed Neighbourhoods: Can Area-Based Urban Policies Counteract Segregation Processes?” Housing Studies 19 (4): 517–539. doi:10.1080/0267303042000221945.

- Andersson, R., Å. Bråmå, and E. Holmqvist. 2010. “Counteracting Segregation: Swedish Policies and Experiences.” Housing Studies 25 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1080/02673030903561859.

- Andersson, R., and A. Kährik. 2015. “Widening Gaps: Segregation Dynamics During Two Decades of Economic and Institutional Change in Stockholm.” In Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities. East Meets West, edited by T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. V. Ham, and S. Musterd, 110–131. London: Routledge.

- Andersson, R., and S. Musterd. 2010. “‘What Scale Matters? Exploring the Relationships Between Individuals’ Social Position, Neighbourhood Context and the Scale of Neighbourhood.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 92 (1): 23–43.

- Andersson, R., S. Musterd, and G. Galster. 2014. “Neighbourhood Ethnic Composition and Employment Effects on Immigrant Incomes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (5): 710–736. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2013.830503.

- Andersson, R., S. Musterd, and G. Galster. 2018. “Port-of-Entry Neighborhood and Its Effects on the Economic Success of Refugees in Sweden.” International Migration Review, doi:10.1177/0197918318781785.

- Åslund, O., J. Östh, and Y. Zenou. 2010. “How Important is Access to Jobs? Old Question—Improved Answer.” Journal of Economic Geography 10 (3): 389–422.

- Bergsten, Z., and E. Holmqvist. 2013. “Possibilities of Building a Mixed City – Evidence From Swedish Cities.” International Journal of Housing Policy 13 (3): 288–311. doi:10.1080/14616718.2013.809211.

- Bolt, G., J. Burgers, and R. van Kempen. 1998. “On the Social Significance of Spatial Location; Spatial Segregation and Social Inclusion.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 13 (1): 83–95.

- Bolt, G., D. Phillips, and R. Van Kempen. 2010. “Housing Policy, (De)Segregation and Social Mixing: An International Perspective.” Housing Studies 25 (2): 129–135. doi:10.1080/02673030903564838.

- Bolt, G., and R. van Kempen. 2003. “Escaping Poverty Neighbourhoods in the Netherlands.” Housing, Theory and Society 20 (4): 209–222.

- Bolt, G., and R. van Kempen. 2010. “Ethnic Segregation and Residential Mobility: Relocations of Minority Ethnic Groups in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 333–354. doi:10.1080/13691830903387451.

- Bolt, G., R. van Kempen, and M. van Ham. 2008. “Minority Ethnic Groups in the Dutch Housing Market: Spatial Segregation, Relocation Dynamics and Housing Policy.” Urban Studies 45 (7): 1359–1384. doi:10.1177/0042098008090678.

- Borjas, G. J. 1998. “To Ghetto or not to Ghetto: Ethnicity and Residential Segregation.” Journal of Urban Economics 44 (2): 228–253.

- Bråmå, Å. 2006. Studies in the Dynamics of Residential Segregation.

- Bråmå, Å. 2008. “Dynamics of Ethnic Residential Segregation in Göteborg, Sweden, 1995–2000.” Population, Space and Place 14 (2): 101–117. doi:10.1002/psp.479.

- Bråmå, Å., and R. Andersson. 2005. “Who Leaves Sweden’s Large Housing Estates.” In Restructuring Large Housing Estates in Europe, edited by R. Van Kempen, K. Dekker, S. Hall, and I. Tosics, 169–192. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Bråmå, Å., and R. Andersson. 2010. “Who Leaves Rental Housing? Examining Possible Explanations for Ethnic Housing Segmentation in Uppsala, Sweden.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 25 (3): 331–352. doi:10.1007/s10901-010-9179-4.

- Carlsson, M., and S. Eriksson. 2014. “Discrimination in the Rental Market for Apartments.” Journal of Housing Economics 23: 41–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2013.11.004.

- Castles, S., H. de Haas, and M. J. Miller. 2014. The age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Clark, W. A. V. 1992. “Residential Preferences and Residential Choices in a Multiethnic Context.” Demography 29 (3): 451–466. doi:10.2307/2061828.

- Crowder, K., S. J. South, and E. Chavez. 2006. “Wealth, Race, and Inter-Neighborhood Migration.” American Sociological Review 71 (1): 72–94.

- Damm, A. P. 2009. “Ethnic Enclaves and Immigrant Labor Market Outcomes: Quasi-Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Labor Economics 27 (2): 281–314.

- Edgar, B. 2014. “An Intergenerational Model of Spatial Assimilation in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (3): 363–383.

- Edin, P.-A., P. Fredriksson, and O. Åslund. 2003. “Ethnic Enclaves and The Economic Success of Immigrants—Evidence From a Natural Experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (1): 329–357.

- Hedin, K., E. Clark, E. Lundholm, and G. Malmberg. 2012. “Neoliberalization of Housing in Sweden: Gentrification, Filtering, and Social Polarization.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (2): 443–463. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.620508.

- Hedman, L., D. Manley, M. van Ham, and J. Östh. 2015. “Cumulative Exposure to Disadvantage and the Intergenerational Transmission of Neighbourhood Effects.” Journal of Economic Geography 15 (1): 195–215. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbt042.

- Holmqvist, E., and Z. Bergsten. 2009. “Swedish Social Mix Policy: A General Policy Without an Explicit Ethnic Focus.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24 (4): 477. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9162-0.

- Johnston, R. O. N., C. Propper, S. Burgess, R. Sarker, A. Bolster, and K. Jones. 2005. “Spatial Scale and the Neighbourhood Effect: Multinomial Models of Voting at Two Recent British General Elections.” British Journal of Political Science 35 (3): 487–514. doi:10.1017/s0007123405000268.

- Kauppinen, T. M., H. S. Andersen, and L. Hedman. 2015. “Determinants of Immigrants’ Entry to Homeownership in Three Nordic Capital City Regions.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 97 (4): 343–362. doi:10.1111/geob.12085.

- Kauppinen, T. M., and K. Vilkama. 2016. “Entry to Homeownership among Immigrants: A Decomposition of Factors Contributing to the Gap with Native-Born Residents.” Housing Studies 31 (4): 463–488. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1094566.

- le Grand, C., and R. Szulkin. 2002. “Permanent Disadvantage or Gradual Integration: Explaining the Immigrant–Native Earnings Gap in Sweden.” LABOUR 16 (1): 37–64. doi:10.1111/1467-9914.00186.

- Lersch, P. M. 2013. “Place Stratification or Spatial Assimilation? Neighbourhood Quality Changes After Residential Mobility for Migrants in Germany.” Urban Studies 50 (5): 1011–1029. doi:10.1177/0042098012464403.

- Logan, J. R., and R. D. Alba. 1993. “Locational Returns to Human Capital: Minority Access to Suburban Community Resources.” Demography 30 (2): 243–268. doi:10.2307/2061840.

- Logan, J. R., W. Zhang, and R. D. Alba. 2002. “Immigrant Enclaves and Ethnic Communities in New York and Los Angeles.” American Sociological Review 67 (2): 299–322.

- Macpherson, R. A., and M. Strömgren. 2013. “Spatial Assimilation and Native Partnership: Evidence of Iranian and Iraqi Immigrant Mobility from Segregated Areas in Stockholm, Sweden.” Population, Space and Place 19 (3): 311–328. doi:10.1002/psp.1713.

- Magnusson Turner, L., and L. Hedman. 2014. “Linking Integration and Housing Career: A Longitudinal Analysis of Immigrant Groups in Sweden.” Housing Studies 29 (2): 270–290. doi:10.1080/02673037.2014.851177.

- Magnusson Turner, L., and T. Wessel. 2013. “Upwards, Outwards and Westwards: Relocation of Ethnic Minority Groups in the Oslo Region.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 95 (1): 1–16.

- Maloutas, T., and K. Fujita. 2016. Residential Segregation in Comparative Perspective: Making Sense of Contextual Diversity. New York: Routledge.

- Massey, D. S. 1985. “Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Review.” Sociology and Social Research 69 (3): 315–350.

- Massey, D. S., and B. Bitterman. 1985. “Explaining the Paradox of Puerto Rican Segregation.” Social Forces 64 (2): 306–331.

- Massey, D. S., and N. A. Denton. 1985. “Spatial Assimilation as a Socioeconomic Outcome.” American Sociological Review 50 (1): 94–106.

- Massey, D. S., and B. P. Mullan. 1984. “Processes of Hispanic and Black Spatial Assimilation.” American Journal of Sociology 89 (4): 836–873.

- Molina, I. 1997. Stadens rasifiering: Etnisk boendesegregation i folkhemmet (Racialization of the city: Ethnic residential segregation in the Swedish Folkhem).

- Musterd, S. 2003. “Segregation and Integration: A Contested Relationship.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29 (4): 623–641. doi:10.1080/1369183032000123422.

- Musterd, S., R. Andersson, G. Galster, and T. M. Kauppinen. 2008. “Are Immigrants’ Earnings Influenced by the Characteristics of Their Neighbours?” Environment and Planning A 40 (4): 785–805.

- Östh, J. Introducing the EquiPop software – an application for the calculation of k-nearest neighbour contexts/neighbourhoods. http://equipop.kultgeog.uu.se.

- Östh, J., W. A. V. Clark, and B. Malmberg. 2015. “Measuring the Scale of Segregation Using k-Nearest Neighbor Aggregates.” Geographical Analysis 47 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1111/gean.12053.

- Östh, J., B. Malmberg, and E. K. Andersson. 2014. “Analysing Segregation Using Individualised Neighbourhoods.” In Social-Spatial Segregation: Concepts, Processes and Outcomes, edited by C. D. Lloyd, I. Shuttleworth, and D. W. S. Wong, 135–162. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Östh, J., and U. Türk. forthcoming. “Integrating Infrastructure and Accessibility in Measures of Bespoke Neighbourhoods.” In Handbook on Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd. Edward Elgar.

- Pais, J., S. J. South, and K. Crowder. 2012. “Metropolitan Heterogeneity and Minority Neighborhood Attainment: Spatial Assimilation or Place Stratification?” Social Problems 59 (2): 258–281.

- Park, R. E., L. Wirth, E. W. Burgess, and R. D. McKenzie. 1925. The City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Phillips, D. 2010. “Minority Ethnic Segregation, Integration and Citizenship: A European Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 209–225. doi:10.1080/13691830903387337.

- Pinkster, F. M. 2007. Localised Social Networks, Socialisation and Social Mobility in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in the Netherlands. Urban Studies 44 (13): 2587–2603.

- Portes, A., and R. L. Bach. 1985. Latin Journey: Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

- Skifter Andersen, H. 2010. “Spatial Assimilation in Denmark? Why do Immigrants Move to and from Multi-Ethnic Neighbourhoods?” Housing Studies 25 (3): 281–300. doi:10.1080/02673031003711451.

- Skifter Andersen, H. 2015. “Explanations for Special Neighbourhood Preferences among Ethnic Minorities.” Housing, Theory and Society 32 (2): 196–217.

- SKL (Sveriges Kommuner och Landstings). 2011. “Sveriges Kommuner och Landstings (SKLs) kommungruppsindelning (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions’ classification of municipalities).” https://skl.se/.

- Skovgaard Nielsen, R. 2016. “Straight-Line Assimilation in Leaving Home? A Comparison of Turks, Somalis and Danes.” Housing Studies 31 (6): 631–650. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1114076.

- Søholt, S., and B. Lynnebakke. 2015. “Do Immigrants’ Preferences for Neighbourhood Qualities Contribute to Segregation? The Case of Oslo.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (14): 2314–2335. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1054795.

- South, S. J., and K. D. Crowder. 1998. “Leaving the ‘Hood: Residential Mobility Between Black, White, and Integrated Neighborhoods.” American Sociological Review 63 (1): 17–26. doi:10.2307/2657474.

- South, S. J., K. Crowder, and E. Chavez. 2005. “Migration and Spatial Assimilation among U.S. Latinos: Classical Versus Segmented Trajectories.” Demography 42 (3): 497–521. doi:10.1353/dem.2005.0025.

- Tammaru, T., S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, and S. Musterd. 2016. Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities. New York: Routledge.

- van Ham, M., L. Hedman, D. Manley, R. Coulter, and J. Östh. 2014. “Intergenerational Transmission of Neighbourhood Poverty: An Analysis of Neighbourhood Histories of Individuals.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (3): 402–417.

- Vogiazides, L. 2018. “Exiting Distressed Neighbourhoods: The Timing of Spatial Assimilation among International Migrants in Sweden.” Population, Space and Place, e2169. doi:10.1002/psp.2169.

- Wessel, T., R. Andersson, T. Kauppinen, and H. S. Andersen. 2017. “Spatial Integration of Immigrants in Nordic Cities: The Relevance of Spatial Assimilation Theory in a Welfare State Context.” Urban Affairs Review 53 (5): 812–842. doi:10.1177/1078087416638448.

- Zhou, Min. 1992. Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Zorlu, A. 2009. “Ethnic Differences in Spatial Mobility: The Impact of Family Ties.” Population, Space and Place 15 (4): 323–342.