ABSTRACT

As energy transitions are progressing and economies of scale are kicking in, renewable-electricity generation begins to include, and be dominated by, large-scale operations. This shift is accompanied by far-reaching changes in the ownership and financing structures of renewable-energy projects, involving connections and (inter)dependencies between international and domestic investors and policies. With growing sizes and maturity, renewable-energy projects are also increasingly taken to capital markets and have become subject to financialization. Until recently these processes have only been observed in the Global North but not in the Global South. So far there has been little research on renewable-energy financialization in the Global South, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In our paper we address this gap by exploring the international connections and (possible) financialization of two large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya. Based on case-study analyses of geothermal and wind projects in Kenya, we argue that due to their complex risk structure, public investment and support, both from domestic sources and development finance institutions (DFIs), are and will remain key to facilitate or even enable such projects. In contrast to Baker’s (2015) case study on South Africa, we neither see nor expect financialization of large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya and most other Sub-Saharan African countries any time soon.

1. Introduction

In contrast to fossil and nuclear energy, renewable energies for a long time have been characterized by their decentralized organization and geography. As a result research has focused on renewable energies’ role in national energy transitions and policies, and they have mainly been analyzed from bottom-up perspectives (e.g. Ohlhorst Citation2015; Becker, Kunze, and Vancea Citation2017). However, with the progression of energy transitions as well as economies of scale, renewable-energy generation, particularly from wind and geothermal sources, is becoming dominated by large-scale operations (IRENA Citation2018). While national energy and international climate policies are important drivers for large-scale renewable-energy projects, liberalization of energy markets and new infrastructure financing models have led to an increasing role of private and international investments in renewable energies (Pollitt Citation2012; Jamasb, Nepal, and Timilsina Citation2015). This is reflected in the heterogeneous ownership and financing structures of large-scale renewable-energy projects, which are characterized by multifarious connections between domestic and international as well as between public and private investments (OECD Citation2015).

While growing in size and maturity, renewable-energy projects are increasingly taken to capital markets and have become subject to financialization (Klagge and Anz Citation2014; OECD Citation2015). Up until recently these processes have mainly been observed in the Global North but not in the Global South. So far there has been little research on renewable-energy financialization in Global South contexts, with the exception of Baker (Citation2015). And yet projects in the Global South are especially interesting because of the significant role international investments and development finance (Eberhard et al. Citation2016) as well as international development finance institutions (DFIs) play. Some researchers have interpreted their activities as supporting financialization or acting as a catalyst for it (Carroll and Jarvis Citation2014; Mawdsley Citation2018).

In this paper we address the above-stated research gap by exploring the ownership and financing structures as well as (possible) financialization of two renewable-energy projects in Kenya, thereby responding to French, Leyshon, and Wainwright (Citation2011) who call for more research into the space and place dimensions of financialization. Our overarching research questions are the following ones: What are the respective roles of public and private investors in large-scale renewable-energy projects, and how and in which ways are these projects characterized by international connections and/or subject to financialization? We will show that, public actors, policies, and resources, at both the national and international levels, continue to play a decisive role for realizing these projects, despite energy-markets being liberalized and an increased focus on private investments. Based on our analyses, we argue that investment in large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya and very likely also in other Sub-Saharan African contexts is and will remain dependent on domestic government and politics as well as on international development finance. More specifically, we argue that most private and especially institutional-investor participation in such projects is and will be deterred as a result of their complex risk structure, which stands in the way of imminent emergence of financialization.

Our case studies here are two of the largest renewable-energy projects in Africa: Lake Turkana wind park, which was initiated by private actors and the geothermal energy exploitation initiated by the Kenyan national government. Both technologies are contingent on specific geographical and geological conditions, such as extremely high wind speeds in the case of Lake Turkana wind park (Aldwych International Citation2014) and sufficient geothermal resources in Kenya’s Rift Valley, where exploration activities have recently been accelerated (Ngugi Citation2012; Ogola, Davidsdottir, and Fridleifsson Citation2012; Mangi Citation2017). The projects were or are being newly developed for electricity generation and transmission to the Kenyan national grid by different groups and investor types. They differ, however, in their ownership structure as well as in the nature of private-sector involvement. These characteristics make the two cases a good starting point for understanding and untangling complexities in financing large-scale renewable-energy development in Sub-Saharan Africa and possibly other countries of the Global South. It will also allow us to learn whether or not financialization processes play a role in Kenya’s renewable-energy development. In the following sections, we first conceptually situate our case studies in research on financialization and infrastructure finance (section 2), and then outline our empirical research questions and explain our methodology (section 3). After introducing the reader to the Kenyan context, its electricity system, and the case studies (section 4), we analyze their ownership and financing structures with a focus on different investor types and risk mitigation challenges (section 5). We then conclude and reflect on the implications of our results for how large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya and possibly other Sub-Saharan African countries are shaped by international connections and local contexts (section 6).

2. Financialization and investment in infrastructure: the case of renewable energies

2.1. Financialization: fuzzy concept with national bias

Financialization is one of the so-called ‘fuzzy concepts’ (Markusen Citation2003) that have sparked lively academic debates. An early, and very general, definition was provided by Epstein, who refers to financialization as ‘the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies’ (Citation2005, 3). Financialization has been conceptualized and empirically addressed in various economic and societal contexts and at different analytical levels. At the macro level, financialization usually refers to the growing prominence of the financial sector in national economies, especially in the US and the UK. In her seminal work, Krippner defines financialization as ‘a pattern of accumulation in which profit-making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than trade and commodity production’ (Citation2005, 181). At the meso and micro levels, financialization research addresses ‘the growing influence of capital markets (their products, actors, and processes) on firm and household behaviours’ (Erturk et al. Citation2007, 556).

Since financialization was introduced into the academic literature there have been debates on its merits and pitfalls. A major criticism of the work on financialization addresses the national bias in much of the research and discussion, i.e. the neglect of international connections (French, Leyshon, and Wainwright Citation2011; Christophers Citation2012, Citation2015). Furthermore, most (including critical) work on financialization deals with structures and developments in the Global North, and only recently have developments in the Global South received some attention. Mawdsley (Citation2018) is one of the first to discuss financialization as a research area in development geography. She sees a ‘deepening nexus between financial logics, instruments and actors, and intentional “development”’, which goes ‘beyond the more commonly referenced private-sector led development’ (Citation2018, 265 & 264). While citing Carroll and Jarvis (Citation2014, 535 & 538), she states that ‘[f]oreign aid is being used to de-risk investment, ‘escort’ capital to frontier markets, and carry out the mundane work of transforming objects into assets available to speculative capital flows’, thus facilitating capital market growth and thereby serving speculative financial investors’ interests (Mawdsley Citation2018, 264). This provides an interesting take on the role of donors and development finance for infrastructure investment in the Global South. Notwithstanding the ‘fuzziness’ and the different conceptualizations of, as well as critical views on, financialization, it is still a useful starting point for better understanding the extent and implications of the ‘structural transformations of capitalist economies during the last three decades’ (Lapavitsas Citation2011, 611). Today there are various empirical studies which aim at corroborating financialization and its (mainly negative) effects (Assa Citation2012). These effects include, or are results of, a shift in capital market logics towards what is called ‘short-termism’ (Lazonick and O'Sullivan Citation2000; Jackson and Petraki Citation2011). ‘Short-termism’ implies a focus on immediate profits and yields, often at the cost of neglecting the long-term viability of a firm or enterprise as well as its social and environmental implications. This issue is of particular importance in the case of infrastructures, which originally were established to provide good and affordable services to the general public.

2.2. Financialization of infrastructures

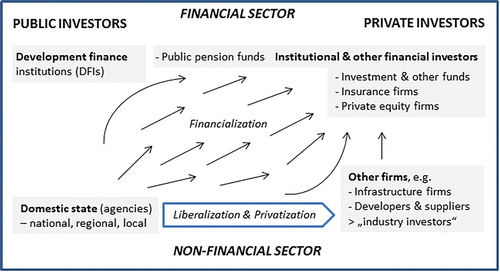

Infrastructures have been an important object in the financialization debate and developed into what is called a new or ‘alternative asset class’ (O’Neill Citation2013; OECD Citation2014, Citation2018; O’Brien, O’Neill, and Pike Citation2019). While in the past, infrastructures were mainly financed with public funds and provided through the local, regional and/or national state (including publicly-owned utilities), liberalization has opened up infrastructure for private investors and public-private partnerships (PPP) (Pollitt Citation2012; OECD Citation2015; Gurara et al. Citation2018). This shift, which is depicted in the bottom of (‘liberalization and privatization’), has further been driven by fiscal crises and budget constraints at all government levels as well as by neoliberal policy agendas and, in the Global South, structural adjustments programmes. As a result, the ownership and financing structures of infrastructures have become heterogeneous, combining private investment with public funding and risk mitigation (Banerji, Bayar, and Chemmanur Citation2018; O’Brien, O’Neill, and Pike Citation2019).

Figure 1. Important types of investors and their relationship with processes of liberalization, privatization and financialization (Authors’ illustration).

To what extent infrastructures can be regarded as financialized depends on how financialization is conceived. When focusing on concrete infrastructures this commonly refers to turning them into a tradeable asset by selling shares to institutional investors or by using other capital-market instruments. In addition, it can also include ownership and/or management by financialized (often listed) firms, which use their assets to maximize short-term financial returns without much regard for serving the public good. While financialization is mainly seen critically, there is also a positive view of taking infrastructures to capital markets. Involving institutional investors or capital market instruments into infrastructure finance is regarded, by its proponents, as a viable potential for providing additional funding for capital-intensive infrastructure projects and for increasing the efficiency of infrastructure management and service (Kaminker and Stewart Citation2012; Kaminker et al. Citation2013; Sharma Citation2013). Critics, in contrast, point out that financialization can lead to under-investment in infrastructures and/or over-pricing of its services due to relentless pursuit of profits and resulting in limited infrastructure access, as well as to exclusion and inequality (Harvey Citation2006; Beizley Citation2015; Bear Citation2017).

Exploring financialization in concrete projects entails looking closely at investors. gives an overview of the most important public (including publicly-funded) and private types of infrastructure investors and their financial and non-financial sectoral classifications. Based on this distinction, we define financialization in our study as the (increasing) involvement of institutional and other (private) financial investors as well as of financialized firms as capital providers. In this view, as depicted through several smaller arrows pointing towards the top right corner in , financialization is by no means a ‘linear, all-consuming, homogenizing, and unstoppable process’, but rather a stepwise development leading to ‘complex, hybrid and messy … arrangements’ (O’Brien, O’Neill, and Pike Citation2019, 1294; also see OECD Citation2015). Typically, liberalization and privatization are precursors of financialization, when institutional or other financial investors buy into, or provide capital for, (privatized) infrastructures. However, as has been pointed out by development researchers, DFIs can also support financialization by ‘escort[ing private financial] capital to frontier markets’ (Mawdsley Citation2018, 264; citing Carroll and Jarvis Citation2014). This is especially relevant for the Global South, where DFIs as well as other publicly-funded international investment and finance facilities (e.g. climate and other green finance) play an important role not only as capital providers but also for risk mitigation and thus for making investments attractive to private investors, possibly also including financial investors.

2.3. The challenge of risk mitigation: role of state and non-state investors in infrastructure projects

Despite liberalization, privatization, and financialization, (domestic) state actors remain important for infrastructure development (O’Brien, O’Neill, and Pike Citation2019). They can maintain shares or become owners of new infrastructure facilities and may provide debt capital and other investment incentives. Often they are responsible for arranging international development and other supporting finance (e.g. climate finance, export credit insurance) and for issuing permits and licenses. And, last but not least, the state provides the regulatory framework through which private investors gain access to infrastructure markets and that (is supposed to) guarantee a certain scale and scope of service provision. This includes stipulations about how non-state investors are remunerated for their engagement (e.g. through guaranteed tariffs) and instruments to mitigate the risk inherent in infrastructure projects in order to make them attractive to private and international investors (OECD Citation2014).

The complex risk structure is one of the greatest challenges associated with attracting and incorporating non-state capital into large-scale infrastructures (OECD Citation2014, Citation2015; Baker Citation2015). This is partly due to the long-term nature of infrastructure investments and projects, where high upfront capital expenditures usually face very long payback periods of 20 or more years. Associated risks include legal and regulatory risks,Footnote1 for example when (domestic) state actors change regulation and remuneration agreements, but also complex bureaucratic procedures and corruption as well as macro-economic risks such as fluctuation of interest-rates, exchange-rates and inflation. While these risks are present throughout the project’s lifetime, there are also specific (pre-completion) risks during the project development and construction phase and during the operational phase (post-completion risks).Footnote2 In designing the ownership and financing structure of an infrastructure project, the different types of risks need to be considered and addressed by contractual risk allocation mechanisms (for details see OECD Citation2014; Banerji, Bayar, and Chemmanur Citation2018).

The most common form of financing large-scale infrastructure projects with private participation is project finance (OECD Citation2014; Banerji, Bayar, and Chemmanur Citation2018). It refers to a non-recourse or limited-recourse financial structure where repayment to capital investors is limited to profits of the projects, thus limiting the risk for equity shareholders. Equity takes most of the risk, senior debt the lowest, and mezzanine finance (incl. subordinate loans) is somewhere in the middle. Generally, equity makes up at least 20% in an infrastructure project and is typically provided by corporate sponsors and developers, i.e. industry investors. Accordingly, debt and mezzanine finance account for up to 80% of the total investment sum, with (syndicated) loans playing ‘the prominent role’ (OECD Citation2014, 6). The contractual structure of an infrastructure project is usually through a special-purpose vehicle (SPV). SPVs are project companies with public and/or private shareholders, banks and other financial institutions providing debt capital, insurance companies dealing with some of the (insurable) risks, contractor(s) and engineers for the construction, an operator for operation and maintenance (O&M) as well as suppliers and off-takers. While renewable energies are a relatively young investment target, project sizes have grown rapidly and, associated with this, the use of project finance and the propensity for financialization.

2.4. Financialization of renewable energies?

Since the liberalization and unbundling of energy markets in the 1990s, renewable-energy infrastructures have become subject to financialization processes (Klagge and Anz Citation2014). Renewable-energy projects are interesting for institutional and other financial investors because they generate steady revenue streams and (if large enough for generating economies of scale) have relatively low transaction costs. However, most financial investors are not ready to bear the huge (pre-completion) risk associated with initial (greenfield) investment in large-scale renewable-energy projects and instead prefer to invest in a completed, already revenue-generating project (OECD Citation2018). This corresponds well with the preferences of developers and technology suppliers who are often major shareholders in the construction phase and tend to sell their shares once the project is operational in order to free-up capital for investment in new projects (Baker Citation2015). Overall, attracting financial and other private capital to large-scale renewable-energy projects depends on the conditions of the risk-sharing agreements, the mix of investors in the project consortium, and the relevant legal and institutional conditions.

Renewable-energy projects have benefitted from various legal, institutional, and political changes in the context of climate policies and also the financial crisis. The financial crisis in 2008 led to an increase in liquidity due to central-bank interventions and decreasing yields in various traditional asset classes; this is why financial (especially institutional), investors searched for new asset types (Inderst Citation2011; OECD Citation2014). Furthermore, the rapid development of renewable energies, supporting policies, and risk-mitigating measures have triggered financial investors’ interest in renewable-energy projects. This is reflected in various investments by institutional investors and financialized firms, for example in offshore wind farms and large renewable-energy companies but also in the development of renewable-energy indices at various stock exchanges (Klagge and Anz Citation2014; OECD Citation2015). Most of these developments have been taking place and have been researched in the Global North, whereas in the Global South financialization of renewable energies, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, has not (yet) been investigated.

2.5. Renewable-energy finance in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)

Renewable energy has a large potential in SSA and can play an important role in achieving various social and economic development goals (Schwerhoff and Sy Citation2017). However, investors perceive the SSA region’s investment environment as riskier than in other regions. This is especially true with regard to legal, regulatory and, market risks but also with regard to how technology and capital markets function (Eberhard et al. Citation2016; Klagge and Zademach Citation2018). Hence these risks make financing renewable energies in SSA more challenging than in the Global North (Oberholzer et al. Citation2018), which is reflected in the general trend of low institutional investment in infrastructure in the SSA region (OECD Citation2018). Furthermore, ‘financing requirements of the power sector far exceed most countries’ already stretched public finances’, making independent power producers (IPPs) and private investment ‘critical to scale up generation capacity and thereby expand and improve electricity supply’ (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, xvii). From 1990 to 2013 governments and utilities provided more than 50% of total investment in completed power generation plants in SSA excluding South Africa,Footnote3 while IPPs already had a share of 22%.Footnote4 Interestingly, almost half of the IPP investment in SSA outside South Africa was provided by DFIs, which emphasizes the great importance of development finance for renewable energy in Africa (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, xxvii).

While the majority of IPP investments in SSA used to be in thermal plants or large hydro projects, IPP investments in other grid-connected renewable energies are ‘gaining traction’ (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, xxxv). South Africa became a regional pioneer with the inception of the country’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Project Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) in this regard. An interesting background to our study on Kenya is Lucy Baker’s exploration of the ‘role that different modes of finance have played in shaping South Africa’s emerging renewable energy sector’ and in which she explicitly discusses ‘finance and financialization as growing features within [the South African mineral-energy complex]’ (Citation2015, 146 & 147). She finds that the ownership structures in REIPPPP projects are mostly dominated by international and domestic industry investors, whereas debt finance is much less international and mainly provided by South Africa-based institutions as ‘[t]here has been minimal appetite for international banks to get involved in debt financing given the currency risk involved’ (Baker Citation2015, 151). The role of international DFIs in South Africa is much smaller than for renewable-energy finance in other SSA countries, with some multilateral DFIs providing debt capital as co-funders ‘in a small number of projects, usually restricted to financing ‘unproven’ technology i.e. CSP'Footnote5 (Baker Citation2015, 151).Footnote6

Baker’s findings exhibit the heterogeneity of the ownership and financing structure of renewable-energy projects in South Africa. Even though they do not directly involve capital markets or institutional investors, Baker anticipates that international financial investors will buy into the projects after the 3-years restriction on the sale of equity is over and that equity shareholdings ‘may [then] very quickly become assets that are restructured, bought, sold and repackaged in the financial markets’ (Citation2015, 154). Interestingly, Baker does not discuss donors and DFIs as drivers of renewable-energy financialization in South Africa. This contrasts with Mawdsley (Citation2018), who in her work on the finance-development nexus argues that donors ‘are currently seeking to accelerate and deepen financialization in the name of “development”’ (Citation2018, 264).

3. Research questions and methodology

The conceptual considerations and literature review show that there are many open questions regarding the financing of large-scale renewable-energy projects in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). On the one hand, private and international capital is needed to expand renewable-energy generation facilities and thereby help to achieve various social and economic development goals. On the other hand, there is concern that the engagement by financial investors other than banks, including DFIs, might lead to financialization with various negative implications. It has also become clear that the national state plays an important role, not only by providing and shaping the institutional context, but also as provider and arranger of risk mitigation as well as a co-investor.

Tackling these issues requires detailed analyses for which, however, the necessary data is not readily available. To answer our overarching research questions and broaden our knowledge on the international connections and financialization of renewable energy in SSA, we provide in the following in-depth analyses of the ownership and financing structures of two landmark developments in the Kenyan renewable energy sector: the Lake Turkana Wind Power project (LTWP) and recent geothermal developments. The empirical research questions are as follows:

Who are the owners and investors in these projects, and how do they finance the projects (equity, debt)? What are the roles of different investor types?

What is the balance between domestic and international, public and private, and financial and non-financial investors?

How is the mix of investors related to the challenges of risk mitigation, and what types of risk mitigation approaches and instruments are built into the ownership and financing structure?

To answer these questions, we conducted a thorough literature and newspaper-articles review, and we conducted interviews with key experts involved in geothermal and wind energy development in Kenya. The interviewees work at different government levelsFootnote7 (MoEFootnote8, County Commissioners, County Government representatives), in energy-related and other state agencies (ERC, GDC, KenGen, NLC)Footnote9, in development finance institutions (AFD, AfDB, EIB, KfW, TDB, USAID)Footnote10, in private firms (Tetra-Tech, GeoHydro Energy Consultants Limited) and in an energy research institute (GETRI).Footnote11 In addition, we analyzed relevant investment and policy documents and conducted site visits in both Menengai and Baringo-Silali geothermal fields. As some of the interviews were granted on the condition of anonymity, we do not provide further details on the interviewees. Based on cross-checking and triangulating the statements from different interviews and sources, we only present findings that are plausible and coherent or otherwise indicate that there is contradictory evidence.

4. The Kenyan context, its electricity system and the case studies

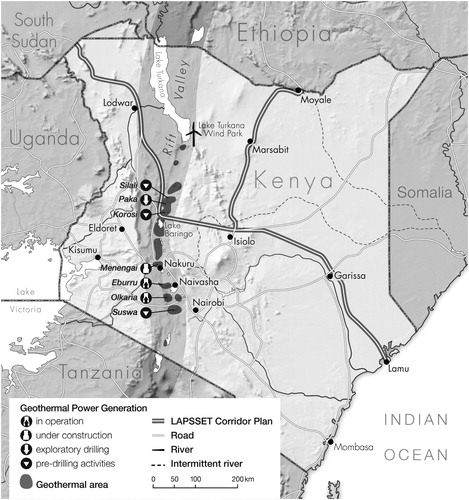

Kenya has a population of approximately 50 million and is among the largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with a continuously growing GDP, both in absolute terms and per capita (WBG Citation2019). The Kenyan government aspires to become a middle-income country by 2030 – a goal envisioned and elaborated in its Kenyan Vision 2030 document. As part of this vision, the Kenyan government plans, and in some cases has already started, massive investments in its infrastructures (roads, railways, sea port, airports, pipe-borne water, information and communication technology) as drivers of its ambitious economic development plans (GoK Citation2007, 8 & 4). This includes the transnational Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET), which aims to develop the previously marginalized areas in Northern Kenya (; Browne Citation2015; Greiner Citation2016). To finance these and other infrastructures, the Kenyan government started launching infrastructure bonds in 2009 with terms of maturity of 12–25 years. These bonds are tax-free with relatively high coupon rates (mostly above 10%) and thus attractive to both international buyers and domestic (incl. small) investors. From the financial years 2008/09–2017/18, the Kenyan government issued 13 infrastructure bonds with a total worth of Ksh 413 billion and by mid 2018 with a total outstanding stock of Ksh 303 billion as some of the bonds were amortized (GoK Citation2018). These government-issued infrastructure bonds added to the country’s growing public debt,Footnote12 which has risen from around 40% in 2008 to more than 55% of GDP in mid 2018, thereby reaching ‘dangerous levels’ according to some observers (CBK Citation2018; Kodongo Citation2018; Ngugi Citation2018).Footnote13

Figure 2. Map of Kenya showing the Lake Turkana Wind Power project (LTWP), geothermal power generation areas and the planned LAPSSET corridor (Authors’ illustration based on Browne Citation2015; Mangi Citation2017; Interview information 2019).

Given the importance of electricity for achieving the stipulated economic development goals by 2030, the Kenyan government plans to attain universal access to electricity by 2020 (GoK Citation2007). Between 2010 and 2016 the percentage of electrified households already increased from 18% to 65% as a result of newly-developed power plants and grid extensions (IEA Citation2017, 114). While Kenya’s total installed grid-connected capacity stood at 2,300 MW in 2015, it would take an additional 2,700 MW to reach universal electricity access by 2020 (USAID Citation2015; Eberhard et al. Citation2016, 101). To achieve this goal, the government plans to continue regulatory and utility reforms in order to usher in private investors and increase private-sector participation (GoK Citation2007, 8). To better understand the development of large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya, the following sections provide some background on its electricity system (4.1) as well as on the physical and institutional conditions of geothermal energy projects (4.2), and the LTWP (4.3).

4.1. Kenya’s electricity system and support for developing renewable energies

The electricity mix in Kenya has always been dominated by renewable energies contributing more than 75% of electricity generation to the national grid (Kiplagat, Wang, and Li Citation2011). However, while in the past hydropower projects made up the bulk of such projects and were the most important baseload provider, in 2014 geothermal surpassed hydropower in terms of power production, accounting for 51% (geothermal) and 38% (hydropower) respectively (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, 107).

While there are relatively few opportunities for new hydropower projects and existing plants increasingly suffer from droughts, the government has identified geothermal power as the ‘least cost source of energy’, which can ‘become a preferred contributor of baseload power’ (Kiplagat, Wang, and Li Citation2011, 2969, 2971). Furthermore, the government is currently reviewing plans to develop a coal-fired power plant in Lamu County (Browne Citation2015; AfDB Citation2016; Amu Power Citation2018); it had also considered building nuclear plants but has deferred those plans to 2036 as a result of the government’s current priority on renewable-energy projects (Alushula Citation2018; ERC, MoE interviews 2019). Wind has also attracted some attention as an additional renewable-energy source, and there are several wind projects operational or in development, most famously the Lake Turkana Wind Park. Geothermal and especially wind energy development are still relatively new in the SSAn context, and Kenya is one of the few countries in the region where both energy sources are exploited on a large scale (Suberu et al. Citation2013; IEA Citation2014).

The high upfront financing requirements of large-scale renewable-energy projects far exceed Kenya’s public finances, which is why donor and private-sector participation, both from international and domestic sources, are actively solicited through the implementation of supporting policies and frameworks (Eberhard et al. Citation2016). The necessary institutional conditions were established in the mid 1990s when Kenya’s government started, under the influence of the World Bank, to restructure and liberalize its energy sector (Eberhard et al. Citation2016). This ‘neoliberal energy transition’ (Newell and Phillips Citation2016, 39) resulted in the current hybrid market structure of Kenyan’s energy system. Whereas the Kenyan electricity sector is still dominated by publicly-owned or -dominated companies such as KenGen (electricity generation) and KPLC (transmission & distribution), private investment and investors are playing an increasingly larger role (Kiplagat, Wang, and Li Citation2011; Eberhard et al. Citation2016; KenGen interview 2019), mainly as independent power producers (IPPs).

The main incentive for private-sector investment in renewable energy in Kenya are feed-in-tariffs (FITs), i.e. the guarantee to off-take the generated electricity at a fixed price per kWh for 20 years (GoK Citation2012) and thereby mitigating (post-completion) market risk for investors. To fast-track the exploitation of geothermal energy, in 2004 the Kenyan government incorporated the Geothermal Development Corporation (GDC) as a SPV with the aim of realizing a capacity of 5,000 MW by 2030. The establishment of this parastatal is due to the fact that geothermal energy entails high (pre-completion) exploration risks. These risks are specific to this technology and include the risk of high and hard-to-calculate drilling costs as well as of not hitting steam at all or finding far less capacity than anticipated (GDC, MoE interviews 2019). Supported by foreign donors and development partners, GDC covers the very high upfront costs for drilling and assessment of geothermal resources and, together with other state agencies and international development partners, for establishing the necessary ancillary infrastructures (roads, water provision etc.). Furthermore, GDC deals with legal issues concerning land (access) rights, environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) licenses, and establishes community-engagement frameworks, all of which has the potential of causing conflict and thus pose risks to the realization of geothermal projects (Mariita Citation2002; GDC, NLC interviews 2019). Eventually, in case of sufficient resource potential, GDC sells the generated steam or the established plants to KenGen or to (private) IPPs, which are then responsible for building power plants for electricity generation and/or direct (e.g. industrial) usage of steam (Kiplagat, Wang, and Li Citation2011).

4.2. Geothermal electricity generation in Kenya

Exploration of geothermal energy in Kenya started in the 1950s with the first grid-electricity generation commissioned in 1981 by KenGen (Mangi Citation2017; KenGen interview 2019). So far, Olkaria and Eburru are the only geothermal fields that generate electricity for the grid (Omenda and Simiyu Citation2015; Mangi Citation2017). While the small wellhead generator at Eburru is owned by KenGen, the power plants in Olkaria are owned by KenGen and Orpower4 (an IPP) as well as Oserian, an IPP that developed the power plants for its private use in flower farms (Mangi Citation2017; Omenda and Simiyu Citation2015, KenGen interview 2019). As of 2017, the total geothermal energy-generation capacity in Kenya stood at 657 MW, of which 78% were owned by KenGen and 22% were privately owned (calculated from Mangi Citation2017).

In addition to the geothermal sites already operating, the Rift Valley provides further vast potential for the exploitation of geothermal energy, estimated at 7,000 MW in total (Ngugi Citation2012; Omenda Citation2014; Mangi Citation2017). Different from most of these sites where only surface explorations have taken place, operations in Menengai and the Baringo-Silali Block are more advanced because the two sites have the highest estimated resource potentials (GDC Citation2011; Mangi Citation2017). Other recent geothermal developments include the expansion of existing power units in Olkaria as well as some private initiatives (GDC Citation2011; Mangi Citation2017; Nchoe Citation2018). As the financing of these developments is not documented in detail, the following analyses concentrate on Menengai and Baringo-Silali, the latter containing the three sites Korosi, Paka, and Silali.

4.3. Lake Turkana wind power development

In addition to its geothermal resources, Kenya also has large wind resources, especially in the marginal and the arid Northern parts of the country. This is where Lake Turkana Wind Park was developed by an international consortium of private and public firms and institutions, called the Lake Turkana Wind Power (LTWP) Limited, starting in 2006. After a development phase of eight years the project reached its financial close in December 2014. The construction of the wind farm started in January 2015 and was completed in mid 2017 (Schilling, Locham, and Scheffran Citation2018, 1); however, because of delays in the construction of the transmission line, the park only started feeding electricity into the national grid in late 2018 (Kamau Citation2018). Turbines were provided by Danish manufacturer Vestas, and Vestas was also tasked with the supply and maintenance for the initial 10 years after the project was commissioned (Jørgensen Citation2016; PT Citation2019; KP&P Africa website as of April 27, 2019). With 365 turbines and a generation capacity of 310 MW, LTWP is the largest single wind park in Africa – and at the time was the largest private investment in Kenya’s history (LTWP Citation2014).

The Kenyan government was neither part of the consortium nor among the lenders. However, it was responsible for the pre-negotiated power-purchase agreement (PPA) with KPLC (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, 113) and for the construction of the more-than-400 km transmission line that connects the project to the national grid (AfDB Citation2013; AfDB, ERC, MoE interviews 2019). The World Bank was also involved but withdrew its risk guarantee commitment in 2012 because of its concerns over over-generation of electricity in relation to short-term demand and consumption (Dodd Citation2012). Additionally, there were criticisms regarding negative social and environmental impacts, land (use) conflicts, and the consideration of local-communities’ interest (Danwatch Citation2016; Enns Citation2016; Schilling, Locham, and Scheffran Citation2018). These, however, did not stop the project but rather triggered an intensification of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities (County Commissioners and County Government representatives interviews 2019). It is against this background that the project presents itself as a Vision 2030 flagship project and ‘transformative … in terms of the development impact to the Northern arid areas of Kenya, the electricity sector, and to Kenya as a whole’ (LTWP Citation2014).

In contrast to geothermal exploration and development led by state-owned GDC, LTWP overall is an example of a predominantly foreign-driven and partly privately financed large-scale renewable-energy project. However, both large-scale renewable-energy projects are part of the development plan for Northern Kenya and have made Kenya a pioneer in developing large-scale renewable-energy projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has attracted worldwide attention. To what extent the projects have attracted capital from private, international, and financial investors is examined in greater detail in the next section.

5. Case-study analyses

This section presents, analyses, and discusses the ownership and financing structures of the LTWP project and recent geothermal energy projects in Menengai and Baringo-Silali. They both have large planned (or actualized, in the case of LTWP) plant capacities – 310 MW for LTWP and 465Footnote14 MW for Menengai, whereas Baringo-Silali is still in the explorative drilling stage. All projects are being newly developed by different groups and investor types for electricity generation and transmission to the Kenyan national grid. The projects are, however, different in their ownership structure as well as in the nature of private-sector involvement. In the following we first give overviews of the ownership and financing structures of Menengai and Baringo-Silali (5.1) and LTWP (5.2) and then we analyze the different investor types and their respective roles (5.3-5.5) as well as the challenges of risk mitigation in Kenya’s large-scale renewable-energy projects (5.6).

5.1. Menengai and Baringo-Silali ownership and financing structures

Menengai, located in the north of Nakuru, is the most advanced new geothermal development and has an estimated potential of 1,600 MW (Mwangi Citation2017). Exploratory drilling began in 2010, leading to steam discovering in 2011 (GDC Citation2011). Assessment, exploration and drilling for Phase 1 was financed by GDC together with loans from several development finance institutions as well as a combined loan and grant from the Scale-up Renewable Energy Program (SREP) ().

Table 1. Capital investment and grants in the Menengai geothermal project Phase 1: name and type of capital/grant providers, country of origin, sum and type of invested capital (only assessment, exploration and drilling, that is excluding IPP investment).

Following the discovery of steam, three independent power producers were selected through competitive bidding and charged to build, own, and operate three power plants with a total capacity of 105 MW (AfDB Citation2018; Richter Citation2018a), with steam provided by GDC. The three IPPs are Quantum Power East Africa GT Menengai Ltd, Orpower22 (a consortium of Ormat, Civicon and Symbion), both mainly originating in the US, and the Kenyan Sosian Menengai Geothermal Power Limited (SMGPL) (AfDB Citation2018; Richter Citation2018a). All three IPPs have started seeking for debt financing (AfDB, TDB, EIB interviews 2019).

Farther north, the Baringo-Silali Block has a combined estimated potential of 3,000 MW (Mwangi Citation2017; Richter Citation2018b). Whereas the Menengai project is located close to a larger city (Nakuru), the Baringo-Silali Block lies in a remote area inhabited mainly by pastoralists and agro-pastoralists (Ogola, Davidsdottir, and Fridleifsson Citation2012; Greiner Citation2017). To allow geothermal exploration and drilling, various ancillary infrastructures had to be constructed first, including roads, water pipelines, and treatment plants. Drilling started after a road network of more than 100 km was built and the water infrastructure for drilling and for providing drinking water to people and their cattle was established. In December 2018, the first rig was transported to Paka from the Menengai project and exploratory drilling in the Baringo-Silali Block started (GDC Citation2019). Financing for all these activities and infrastructures (except for the roads)Footnote15 was provided by GDC, co-financed with a large loan from the German development finance institution KfW, and additionally supported by the African Union Commission (AUC) through the Geothermal Risk Mitigation Facility (GRMF) (see ).

Table 2. Capital investment and grants in the Baringo-Silali geothermal project (assessment, exploration and drilling; ongoing operation): name and type of capital/grant providers, country of origin, sum and type of invested capital, as of April 2019 (financing not completed).

5.2. LTWP ownership and financing structure

LTWP was initiated in 2006 as an unsolicited bid by Kemperman Paardekooper & Partners Africa (KP&P Africa), a consortium of Dutch and Kenyan businessmen (KP&P Africa website as of April 28, 2019). In 2010, Aldwych Turkana Limited, a subsidiary of Aldwych International, which is an experienced African power development company registered in England and Wales, joined KP&P Africa as co-developer with the mandate of overseeing the construction and operations of the power plant on behalf of LTWP (KP&P Africa website and Aldwych International website as of April 28, 2019). In the same year the world-leading Danish turbine producer Vestas,Footnote16 the Danish Investment Fund for Developing Countries (IFU), and the Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries (Norfund), both government-established DFIs, became equity shareholders in the project. In 2013, another Scandinavian DFI, the Finnish Fund for Industrial Cooperation Ltd (Finnfund) and Sandpiper Ltd, a GIS company incorporated in Kenya, joined the consortium. The total equity finance was estimated at €125 million ().

Table 3. Capital investment in the Lake Turkana Wind Power (LTWP) project (completed): name and type of investors, country of origin, sum and type of invested capital.

The project’s debt raising and arrangement was led by the African Development Bank (AfDB) together with the Standard Bank of South Africa and Nedbank Limited as co-arrangers. Debt funding was provided by various development banks, institutions, and facilities (LTWP Citation2014). After the World Bank’s withdrawal of in 2012 (see 4.3), the AfDB played an even greater role in building investor confidence on mitigation of environmental and governance risks (AfDB Citation2013; AfDB interview 2019). AfDB’s prominent role as well as that of various development organizations were not only related to the project’s energy-related benefitsFootnote17 but also justified by the positive impact on local labor markets during construction and the ‘upgrade [of] the rural road network, significantly improving access to markets and business opportunities for the local communities, thus catalyzing additional jobs and income-generation opportunities in this poor and remote area’ (AfDB Citation2013). Additional benefits were expected from the project’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programme, which supported investments in local health, drinking water, and school facilities (AfDB Citation2013; Aldwych International Citation2014; County Commissioners and County Government representatives interviews 2019).

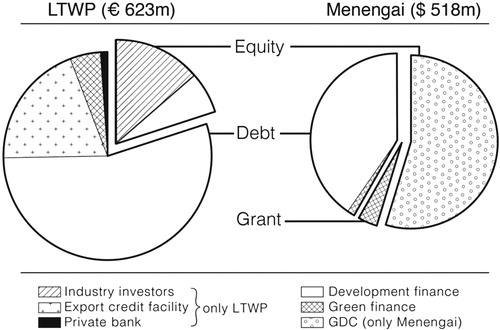

5.3. Equity-debt ratio and the national’s state enabling role

In the financing mix of renewable-energy (and other) projects, the equity-debt ratio can be interpreted as a signifier of how risky a project is perceived by potential investors (cp. 2.3). Whereas LTWP exhibits an equity share of only 20%, the percentage in the Menengai (Phase 1) assessment, exploration, and drilling activities is well above 50% () and which can be explained by the great risk associated with geothermal energy exploration. The so-far relatively low equity share – and overall capital – in Baringo-Silali () is related to the early exploration stage and to the fact that the drilling rigs are not newly acquired but taken and transported from Menengai after drilling for Phase 1 was completed there. The different risk structures are also reflected in the specific roles the (national) state takes on in both projects.

Figure 3. Shares of equity, debt and grant financings of the Lake Turkana Wind Power project (LTWP) and Menengai geothermal project (Phase 1; assessment, exploration and drilling) (Authors’ illustration based on and ).

LTWP does not involve direct state investment (), whereas the geothermal projects in Menengai and Baringo-Silali do. There the Kenyan national state, through GDC, is the initiator and until now the only equity investor ( and ). GDC, together with DFIs, absorbs most of the exploration risk before (private) IPPs will build, own, and operate power plants (see 5.1). The IPPs will benefit from FITs for renewable energies in Kenya and associated PPAs with KPLC. In the LTWP project case, the state’s involvement also included providing incentives in form of a favorable PPA with KPLC and by taking the responsibility of constructing the required circa 400 km high-voltage transmission line for off-take of generated electricity. In both cases the national state overall has played an important and enabling role and without its support none of the projects would have materialized.

5.4. Private-sector investment predominantly provided as equity by industry investors

Private-sector participation in infrastructure development in the Global South is increasingly encouraged, and, like in the Global North, often materialized through PPPs (see 2.2). This is also true for LTWP and geothermal development, albeit in very different forms. In LTWP, private companies are the initiators and main owners of the plant (68% of equity). The situation is different in the Menengai project and in Baringo-Silali, where private firms do not become involved as equity investors until after a successful exploration and after steam has been discovered. It is only then that IPPs are selected in a competitive bidding process.

In the case of LTWP project, the four private companies involved in the initial project consortium were industry investors who also took other roles in project development: project managers (KP&P, Aldwych), turbine producer and maintenance services (Vestas)Footnote18, and GIS services (Sandpiper). Apart from Sandpiper, which is incorporated in Kenya, these firms are international firms from the Netherlands, UK, and Scandinavia. In debt financing, the only private capital provider is the Dutch Triodos Bank, which contributed a relatively small amount of debt capital and presents itself as a ‘leading expert in sustainable banking … [with] the mission … to make money work for positive change’ (Triodos website as of February 27, 2019).

With private investment predominantly coming from industry investors, the assets in the two cases studies are neither tradable nor are they owned by institutional investors or financialized firms. To further explore the relevance of financialization in our case studies, we now turn to the role of DFIs and other international support facilities.

5.5. The large role of development finance and international public funding

Development institutions are increasingly being structured into development finance institutions (DFIs), which provide development assistance to the Global South by using a broad range of financial instruments (Mawdsley Citation2018). Furthermore, several international climate- and renewable-energy related green-finance facilities complement state government and DFI roles in providing investment incentives and mitigating risks for private investors. In addition to their – often relatively small – financial contribution, these facilities serve as proof for a project’s sustainability and thus not only mitigate risks but together with DFIs also provide legitimacy for private and international investors to join the project. International public funding facilities have consequently become a relevant financing source for large-scale renewable-energy projects. This is also true for our case studies.

DFIs are the by far most important debt capital providers and, in the case of LTWP, also important equity investors as they mitigate the risks for private investors and support renewable-energy development. The equity financing for LTWP involves financing from three Scandinavian DFIs, providing almost a third of total equity. DFIs play an even larger role in LTWP debt financing, both in absolute and relative terms, accounting for 70% of debt financing (). Whereas DFI equity investment only comes from Scandinavian countries, DFI debt financing is more heterogeneous, originating also from several other European as well as African sources and with the AfDB serving as the lead financing arranger and an important capital provider.

To some extent the DFI debt financing structure of LTWP matches that of its project consortium (equity), which has both European and African origins. The Danish and Dutch involvements present especially interesting matches and point to the use of international public funding for supporting (private) industry investors from the same country and thus facilitating export of their products and technologies in the process of delivering ‘development’. An example in point is Vestas, the Danish turbine producer charged with the supply and maintenance of the wind turbines. Together with a Danish DFI in the LTWP equity consortium they have invested in the project and they are also supported by a large loan from the Danish Export Credit Bank (EKF), which absorbs some of the financial and political risks of exporting Danish products to other countries. Another example in point is KP&P B.V, a Dutch private company that initiated the LTWP project and received debt financing from a Dutch DFI and even from a private Dutch bank (Triodos). Together Danish and Dutch investors, including private investors and the Danish Export Credit Bank, account for 44% of equity and almost a third of LTWP debt financing, all resulting to a share of 35% of total capital.Footnote19

In Menengai and Baringo-Silali, where start-up equity financing heavily depended on state-owned GDC, we did not find any obvious connections between DFIs and other project participants. In contrast to LTWP, DFIs are only involved in debt financing and include African, European, and US-American institutions as well as the World Bank. Whereas in Menengai the AfDB and French AFD are the largest debt capital providers and account for more than 80% of debt capital, in Baringo-Silali German KfW is, together with the Geothermal Risk Mitigation Facility (GRMF), the only debt capital provider so far ( and ).

In sum, debt financing in our case studies is heavily dependent on DFIs. They are complemented by other publicly-funded international facilities, including export bank credit and climate- and renewable-energy-related instruments and schemes, albeit with relatively small shares. In comparison with international public funds, private debt capital plays no or only a very minor role. There is no evidence yet that DFIs or other international public funding agencies function as a vehicle for ‘transforming objects [here: our case study projects] into assets available to speculative capital flows’, as posited by Mawdsley (Citation2018, 264). However, at least in the case of LTWP, there is evidence that they serve the interests of private firms from the same country and mitigate their risk. Furthermore, they also pursue their own institutional interests and, according to our interview partners, not only collaborate in the development of large-scale renewable-energy projects but also compete for participation, for the sake of ‘pitching their flags’ in ‘worthy’ projects (AfDB, EIB, KfW, TDB interviews 2019).

5.6. Risk mitigation challenges in Kenya’s large-scale renewable-energy projects

The fact that the majority of investment capital comes from public sources is related to the relatively cumbersome risk involved in large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya. In addition to the risks associated with the long-term nature of these infrastructure projects, there are various risks that are peculiar to the Kenyan – and more generally the Sub-Saharan African – context. Political and pre-completion risks, on the one hand, include legal and regulatory issues (land rights, environment, and social impact assessment) and are also related to implementing and developing relatively young technologies in the Kenyan context, where success cannot be guaranteed (Mariita Citation2002; GDC, NLC interviews 2019). In the case of geothermal energy projects, assessment, exploration, and drilling pose a technology-specific risk and at the same time require large amounts of capital (GDC, MoE interviews 2019). The Kenyan government established GDC to carry these risks and the costs specific to geothermal development, and it established KETRACO to construct the required new transmission lines, which connect the new projects to the national grid (Eberhard et al. Citation2016; GDC GeoHydro Consulting, MoE interviews 2019). Both state agencies are supported by large amounts of international development and renewable-energy or climate finance (AFD, KfW, MoE, Tetra Tech, USAID interviews 2019).

Post-completion risks, on the other hand, are associated with the functioning of the Kenyan electricity market and its institutions. The payment of FITs and honoring PPAs and other contracts is not a completely assured condition, and there is still room for improvement in the provision of a reliable and institutionally sound investment environment in the country. And while the expansion of electricity generation has been successfully pursued, the continuation of these efforts poses some challenges. Our interviewees pointed out that electricity supply is already exceeding demand because various development projects (e.g. LAPSSET corridor, expansion and electrification of SGR, the new standard-gauge railway) are delayed (AFD, AfDB, MoE interviews 2019). Unless this is countered by injecting (additional) public money into the electricity sector, this could lead to higher tariffs and thus impede the desired industrial development. Furthermore, the current unsustainable public-debt-to-GDP ratio in Kenya, in addition to the complicated and bureaucratic government processes in closing contracts, have increased private investors’ wariness (Kodongo Citation2018; MoE interview 2019).

Interestingly, from our expert interviews we know that most of the developers, financiers, and policy makers did not regard the risks associated with environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs), land (rights), labor, permits, local acceptance and support as a major impediment to investment or development. While they saw community participation and benefit sharing as a great challenge in large-scale renewable-energy development, especially in Kenya’s arid north, they were optimistic that those challenges were manageable through compensation schemes (where applicable), local engagement, hiring policies, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) measures (EIB, ERC, GDC, KenGen, KfW, MoE, TDB interviews 2019). All of these local engagement activities have been applied in the case-study projects and are important factors and (in most cases), a prerequisite for engagement of DFIs and other international investors. However, their success(ful implementation) is not guaranteed, particularly in Kenya’s northern arid areas, which are inhabited by pastoralists and agro-pastoralists with a long history of violence (Ogola, Davidsdottir, and Fridleifsson Citation2012; Greiner Citation2016; Schilling, Locham, and Scheffran Citation2018). Furthermore, in the several informal interviews we conducted during our site visits, we learned that there are various uncertainties resulting from recent changes in land laws, the devolution of government functions in 2013 as well as resistances and conflicts associated with transformation of local livelihoods.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Financing renewable-energy projects in Kenya, and very likely also in other Sub-Saharan African contexts, is a complex endeavor and involves many different actors. However, while there is usually a mix of investors, our case studies show that public investment and public actors are key to facilitate or even enable such projects. Interestingly, it is not or not only the national state that played this enabling role but also development finance institutions (DFIs) that provided the majority of debt funding in both case studies and even some equity in LTWP.

The comparison of the two projects reveals the key role of risk for the investor mix, especially for private investors. A proven technology like onshore wind can attract international private investment from the start or international private investors might even initiate such projects if there is leverage through public funding and institutional conditions are perceived as stable (enough) and supportive (e.g. including market risk mitigation through FITs or PPAs and the provision of grid connections). In contrast, the high risk of geothermal exploration deters private investors in the early (project development) phase, and even after steam has been found the process of getting IPPs involved is cumbersome. In our case studies we therefore see a difference in the timing of private investments, which is closely associated with (technological) pre-completion risk and also leads to a different development of international connections.

It is against the background of the complex risk structure and in contrast to Baker’s (Citation2015) expectation of financialization in South Africa’s renewable-energy sector, we do not expect or observe financialization with regard to large-scale renewable-energy infrastructure in Kenya and most other Sub-Saharan African countries – at least not in the sense that project shares will be traded in stock exchanges or owned by institutional investors or financialized firms any time soon.

The private capital providers in both LTWP and geothermal development are industry investors with defined stakes in project operations, but so far there are no private financial investors. The only exception is a Dutch sustainability bank, which granted a very small loan to LTWP. Regarding the balance between domestic and international investment, there is a clear dominance of international investors in both equity and debt finance for LTWP, whereas in geothermal projects this is only the case for debt finance. However, with IPPs entering the scene, the equity balance for Menengai is also shifting towards a greater role of international as well as to private (industry) investors, thus typifying the process labelled as ‘liberalization & privatization’ in .

There is also no evidence so far that DFIs, though de-risking investment for private (industry) capital in the case of LTWP, support financialization or serve speculative financial investors’ interests, as suggested by Carroll and Jarvis (Citation2014) and Mawdsley (Citation2018). Rather, our interviews showed that DFIs seem to see these projects as their contribution to climate change mitigation and development policies, which is why they not only compete for participation but also cooperate in ‘worthy’ projects.

Overall, investment in large-scale renewable-energy projects in Kenya and other Sub-Saharan African countries with similar or even less favorable macro-economic conditions and income-level is and will very likely remain dependent on government and politics, both at the domestic and international level. This is mainly due to the various risks associated with such projects, which in combination with the strong role of government and politics so far deters most private and especially institutional-investor participation. However, as stated earlier, financialization is by no means a ‘linear, all-consuming, homogenizing, and unstoppable process’, but rather a stepwise development (O’Brien, O’Neill, and Pike Citation2019, 1294). It therefore remains to be seen whether, and under which conditions, financial investors might become interested and/or DFIs might change their strategies in the future.

What are the implications of our findings for the conceptualization of international connections of large-scale renewable-energy projects and their relationship with local contexts? Our analyses have shown that besides the Kenyan government, DFIs are the most important enablers and financiers for these projects in Kenya. Although they do not support financialization so far, they are important facilitators of internationalization. First of all, DFI provide capital from abroad and sometimes, as is the case for LTWP, also de-risk foreign investments of private investors from their respective home countries. Furthermore, as some interviewees mentioned, DFI investment is often associated with the import of technology goods as well as technology-related services also from their respective home countries (KfW, TDB interviews 2019). They thus strengthen international connections beyond capital flows and development support for the receiving country. This, however, is qualified by the fact that, at least in geothermal-energy projects, domestic capacity building is a major part of the projects, and that Kenya has started to become an exporter of geothermal expertise to other East African countries (GETRI, KfW, MoE interviews 2019). To what extent this will help to achieve the ambitious goal stipulated in the Vision 2030, i.e. becoming a middle-income country by 2030, will also depend on whether and how large-scale renewable-energy projects support economic and social (including labor markets) development at the local level.

In Kenya, domestic and local-level activities are strongly shaped by state actors at various levels: national, local and, since the 2013 devolution, county. In addition to the government’s provision of investment incentives, their activities comprise carrying out environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) as well as securing permits, land (rights), labor, and also local acceptance and support (GDC, MoE, NLC interviews 2019). These activities are managed and monitored mainly at the domestic or even local level, e.g. by GDC, but require various state agencies and other domestic stakeholders (GDC interview 2019) to collaborate. As a result, large-scale renewable-energy projects are characterized by an intricate web of international and national relations, including local, financial, and other relations as well as (inter)dependencies that link national energy transition to international development and climate policies. This web entails an interesting, though not clear-cut division of labor between DFIs and other international investors, on the one hand, and the state as well as other domestic actors on the other hand. Whereas the former are mainly occupied with the financial and technological dimensions, i.e. project’s international connections, the latter deal with national challenges and local uncertainties. As we have focused on the international and financial dimension of large-scale renewable-energy projects in this article, future researches can link our findings more thoroughly to the local level and by so doing contribute to the understanding of the extent to which large-scale renewable-energy projects change local economies and livelihoods and also how local elites are involved. Furthermore, research on the subject matter in different Global South contexts is needed, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa where research on infrastructure finance, its international connections, and local contexts is still limited.

Acknowledgements

We thank Clemens Greiner at the University of Cologne as well as two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Also referred to as political risk.

2 While pre-completion risks mainly refer to exploration, planning, construction, and technological risks, post-completion risks include supply and market risks.

3 South Africa features more IPP projects with a higher investment sum than all other SSA countries combined (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, xxv). The figures include both renewable and non-renewable power generation.

4 The remaining investment comes from China (16%) and ODA, DFI, and Arab funds (11%) (Eberhard et al. Citation2016, xxv).

5 CSP = concentrated solar power.

6 Baker (Citation2015, 151) explicitly mentions the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), both part of the World Bank Group, and the European Investment Bank (EIB).

7 National, local and, since 2013, county levels, following the devolution of government functions in Kenya (Hope Citation2014).

8 Ministry of Energy.

9 Energy Regulatory Commission, Geothermal Development Company, Kenya Electricity Generating Company, National Land Commission.

10 Agence Française de Développement, African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Trade and Development Bank, United States Agency for International Development.

11 Geothermal Energy Research and Training Institute.

12 Albeit, not substantially. By mid 2018 the total outstanding infrastructure bond debt accounted for only 6% of total outstanding debt (calculated from GoK Citation2018).

13 Higher than IMF recommended 40% ratio of public debt to GDP.

14 This figure includes the envisaged five phases of which only Phase I (with three power plants of 35 MW capacity each) has started so far and is covered here.

15 The roads were built and financed by the Kenyan government (GDC, KfW interviews 2019).

16 through its subsidiary Vestas Eastern Africa Ltd.

17 energy diversification and access to clean energy.

18 After the wind park was completed in 2017, the US internet firm Google acquired Vestas’ 13% share to provide its server farms with green power and thereby relying on an existing business relationship between Vestas and Google (Ecoreporter Citation2015, Citation2017).

19 This does not include the two countries’ ‘share' in EU debt funding sources (EIB, EU-AITF and ICCF), which accounts for 25% of total capital.

References

- Abdallah, R. 2018. “Geothermal Risk Mitigation Facility (GRMF).” African Union Commission. Slides Presented at Regional Workshop on Geothermal Financing and Risk Mitigation in Africa, Nairobi. February 2. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Events/2018/Jan/Geothermal-financing/S4-p2-GRMF-AUC-IRENA-Presentation.pdf?la=en&hash=626AA38E2DA2DFA64135B1007F0B6C596BCD1803.

- AfDB. 2011. “Menengai Geothermal Development Project.” Project Appraisal Report. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/615591531555223611/1887-XSREKE012A-Kenya-Project-Document.pdf.

- AfDB. 2013. “AfDB Facilitates Energy Diversification and Access to Clean Energy with the Approval of a €115 Million Loan to Turkana Wind Power Project in Kenya.” AfDB News & Events, April 26. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/afdb-facilitates-energy-diversification-and-access-to-clean-energy-with-the-approval-of-a-eur115-million-loan-to-turkana-wind-power-project-in-kenya-11704/.

- AfDB. 2016. “Lamu Coal Power Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Summary.” AfDB Documents. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Environmental-and-Social-Assessments/Kenya_-_Lamu_Coal_Power_Project_%E2%80%93_ESIA_Summary.pdf.

- AfDB - African Development Bank. 2018. “Geothermal Energy Powering Kenya’s Futures. Menengai Geothermal Field Development Facilitated by Public-Private Partnership.” AfDB Case Study, June 2018. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/cif_case_study_kenya_dtp3_1.pdf.

- Aldwych International. 2014. “Lake Turkana Wind Power Project (LTWP).” Slides presented at Seminar on Sustainable Energy Investments in Africa, Copenhagen, June 24-25. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://old.danwatch.dk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Aldwych-Presentation-on-LTWP-2014.pdf.

- Alushula, P. 2018. “Kenya Now Pushes Nuclear Power Plant Plan to 2036.” Business Daily, September, 25. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/economy/Kenya-now-pushes-nuclear-power-plant-plan-to-2036/3946234-4777866-b05oauz/index.html.

- Amu Power. 2018. “Amu Power Signs Clean Coal Technology Agreement with GE.” Press Release, May 16. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.amupower.co.ke/downloads/Press-release-16.05.2018.pdf.

- Assa, J. 2012. “Financialization and its Consequences: the OECD Experience.” Finance Research 1 (1): 35–39. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://researchpub.org/journal/fr/number/vol1-no1/vol1-no1-4.pdf.

- Baker, L. 2015. “The Evolving Role of Finance in South Africa’s Renewable Energy Sector.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 64: 146–156. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.017.

- Banerji, S., O. Bayar, and T. J. Chemmanur. 2018. “Optimal Financial and Contractual Structure for Building Infrastructure Using Limited-Recourse Project Financing.” Working Paper, Boston College doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2795889

- Bear, L. 2017. “‘Alternatives’ to Austerity: A Critique of Financialized Infrastructure in India and Beyond.” Anthropology Today 33 (5): 3–7. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12376.

- Becker, S., C. Kunze, and M. Vancea. 2017. “Community Energy and Social Entrepreneurship: The Purpose, Ownership and Embeddedness of Renewable Energy Initiatives.” Journal of Cleaner Production 147: 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.048.

- Beizley, D. 2015. “Financialization of Infrastructure: Losing Sovereignty on Energy and Economy.” Observatori del Deute en la Globalització. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://odgcatdytm.cluster027.hosting.ovh.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/financialization_of_infrastructure_eng.pdf.

- Browne, A. 2015. “LAPSSET: The History and Politics of an Eastern African Megaproject.” Rift Valley Institute Report. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://riftvalley.net/publication/lapsset#.XMGaiWgzaPR.

- Carroll, T., and D. S. L. Jarvis. 2014. Financialisation and Development in Asia. London: Routledge.

- CBK – Central Bank of Kenya. 2018. “Public Debt.” Central Bank of Kenya. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.centralbank.go.ke/public-debt/.

- Christophers, B. 2012. “Anaemic Geographies of Financialisation.” New Political Economy 17 (3): 271–291. doi:10.1080/13563467.2011.574211.

- Christophers, B. 2015. “The Limits to Financialization.” Dialogues in Human Geography 5 (2): 183–200. doi:10.1177/2043820615588153.

- Danwatch. 2016. “A People in the Way of Progress — Part 3.” Danwatch, June 8. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://medium.com/@Danwatch/a-people-in-the-way-of-progress-part-3-b01c3be0caee.

- Dodd, J. 2012. “World Bank Withdraws Support for Lake Turkana Wind Power Project.” Wind Power Monthly, October 23. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.windpowermonthly.com/article/1156128/world-bank-withdraws-support-lake-turkana-wind-power-project.

- Eberhard, A., K. Gratwick, E. Morella, and P. Antmann. 2016. “Independent Power Projects in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Five Key Countries.” Directions in Development: Energy and Mining. World Bank Group; Washington DC. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0800-5.

- Ecoreporter. 2015. “Vestas Sells Stake in Large Wind Farm in Africa.” Ecoreporter, October 21. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.ecoreporter.de/artikel/vestas-verkauft-beteiligung-an-grossem-windpark-in-afrika-21-10-2015/.

- Ecoreporter. 2017. “Project in Kenya: Vestas Completes Africa's Largest Wind Farm.” Ecoreporter, March 8. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.ecoreporter.de/artikel/projekt-in-kenia-vestas-stellt-groessten-windpark-afrikas-fertig-08-03-2017/.

- Enns, C. 2016. “Experiments in Governance and Citizenship in Kenya’s Resource Frontier.” PhD diss., University of Waterloo. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/144149828.pdf.

- Epstein, G. A., ed. 2005. Financialization and the World Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Erturk, I., J. Froud, S. Johal, A. Leaver, and K. Williams. 2007. “The Democratisation of Finance? Promises, Outcomes and Conditions.” Review of International Political Economy 14 (4): 553–575. doi: 10.1080/09692290701475312

- French, S., A. Leyshon, and T. Wainwright. 2011. “Financializing Space, Spacing Financialization.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (6): 798–819. doi: 10.1177/0309132510396749

- GDC. 2019. “Baringo-Silali Exploration Drilling on Course.” GDC Blog, January 24. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://www.gdc.co.ke/blog/baringo-silali-exploration-drilling-on-course/.

- GDC – Geothermal Development Company. 2011. “GDC Strikes Steam in Menengai.” GDC, May-June, 2011. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.gdc.co.ke/steam/steam4.pdf.

- GoK. 2007. “Kenya Vision 2030.” The Government of Kenya. Accessed January 12, 2019. http://www.vision2030.go.ke/home/.

- GoK. 2012. “Feed-in-Tariffs Policy for Wind, Biomass, Small Hydros, Geothermal, Biogas and Solar.” Ministry of Energy Kenya, December 2012. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://renewableenergy.go.ke/downloads/policy-docs/Feed_in_Tariff_Policy_2012.pdf.

- GoK - Government of Kenya. 2018. “Annual Public Debt Management Report 2018.” The National Treasury and Planning. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://www.treasury.go.ke/economy1/debt-reports/category/157-annual-debt-management.html?download=873:annual-public-debt-report-2017-2018.

- Greiner, C. 2016. “Land-use Change, Territorial Restructuring, and Economies of Anticipation in Dryland Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10 (3): 530–547. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266197.

- Greiner, C. 2017. “Pastoralism and Land Tenure Change in Kenya: The Failure of Customary Institutions.” Development and Change 48 (1): 78–97. doi:10.1111/dech.12284.

- Gurara, D., V. Klyuev, N. Mwase, and A. Presbitero. 2018. “Trends and Challenges in Infrastructure Investment in Developing Countries.” International Development Policy Revue internationale de politique de développement. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://journals.openedition.org/poldev/2802?lang=de.

- Harvey, D. 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. New York: Verso.

- Hope, K. R. 2014. “Devolved Government and Local Governance in Kenya.” African and Asian Studies 13 (3): 338–358. doi:10.1163/15692108-12341302.

- IEA. 2014. “Africa Energy Outlook: A Focus on Energy Prospects in Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Energy Outlook Special Report. IEA Publications. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://www.iea.org/PUBLICATIONS/FREEPUBLICATIONS/PUBLICATION/WEO2014_AFRICAENERGYOUTLOOK.PDF.