ABSTRACT

While re-employment opportunities for redundant workers have been a much-debated topic in economic geography, the characteristics of these new employments and the medium-run effect of major lay-offs constitute a less explored field. The present paper investigates skill matching between the pre-redundancy job and the employment workers have five years after redundancy by studying the distance and direction of their labour market trajectories. By following 670 manufacturing workers made redundant in major layoffs in 2003, the present paper connects patterns of career mobility and underemployment to possible frictions connected to spatial and industrial mobility. The results indicate that moving some distance from the initial point of departure is correlated with upward mobility. This especially concerns moving to a related industry in the same region or moving to a new region, but within the same industry. Moving too great a distance, however, increases the risk of downward mobility. Moving to unrelated industries in general, but also to related industries in new regions, is associated with a higher risk of facing underemployment in the medium run. In conclusion, the longer-run labour market trajectories, in relation to both distance and direction, need to be addressed if we are to assess the outcome of redundancies.

Introduction

Today’s economy is facing a high turnover in employment, in both declining and expanding sectors and regions (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017; Essletzbichler Citation2007). This entails great pressure on the labour-matching process, where both the time to re-employment and the skill match between the worker and the new employment are of vital importance. High turnover is caused by, e.g. changes in production technology (Autor, Levy, and Murnane Citation2003), an increase in more fixed-term contracts (Holmlund and Storrie Citation2002), and shifts from old to new economic activities (Andersson, Eriksson, and Hane-Weijman Citation2018). Especially low-skilled jobs and routine manual labour have been put under increased pressure to automate or move abroad to low-wage countries (Autor, Levy, and Murnane Citation2003; Dicken Citation2016; Lundquist and Olander Citation2010). These developments have had a pronounced spatial dimension, resulting in regional divergence processes, as manufacturing jobs have been replaced by new service jobs, which are primarily located in the bigger cities (Andersson, Eriksson, and Hane-Weijman Citation2018; Combes Citation2000; Desmet and Fafchamps Citation2005). These large-scale transformations have resulted in labour-matching problems, and the European Commission (Citation2010) put skill matching on the agenda as one of the major challenges faced by European labour markets.

The many negative effects of being laid-off have been discussed in the redundancy literature (e.g. Eliason and Storrie Citation2006; Bailey, Chapain, and de Ruyter Citation2012; Tomaney, Pike, and Condford Citation1999; Huttunen, Møen, and Salvanes Citation2011). Studies in the sub-field of Evolutionary Economic Geography (EEG) have argued for the importance of studying different dimensions of proximities (Boschma Citation2005) in an attempt to understand the skill matching between different jobs. Even so, few have combined the two strands of literature with a view to investigating how the proximity literature can help us to understand the negative effects on redundant workers’ labour market trajectories.

The novelty of the present paper lies in combining these two strands of literature, redundancy and proximity, in an effort to understand that labour market trajectories have both a direction and a distance. As proposed by Nedelkoska, Neffke, and Wiederhold (Citation2015b, 1): ‘ … we need to move beyond the recently proposed symmetric occupational distance measures towards characterizing occupational switches as having both a distance and a direction'. Hence, the present study aims to investigate skill matching between the pre-redundancy job and the employment workers have five years after redundancy by studying the distance and direction of their post-redundancy labour market trajectories. The study will use the same set of categories for geographical and industrial distance employed by Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning (Citation2018) – ‘same’, ‘related’ or ‘unrelated’ industry in ‘same’ or ‘new’ labour market. The present paper will, however, add a direction to these trajectories. This is done by using the Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale (‘SIOPS’) to calculate the occupational status change that workers have experienced with these moves (categorized as ‘career’, being ‘stable’ or becoming ‘underemployed’). In addition, the paper focuses on a group of workers who have been identified in the literature as especially vulnerable to the economic structural changes of recent decades: manufacturing workers outside metropolitan regions without a formal higher education. While this leaves us with a relatively small dataset, it has the advantage of focusing on trying to understand the mobility and re-allocation of a group of workers who are: (i) particularly vulnerable to the ongoing structural changes of today's economy, and (ii) particularly vulnerable when subjected to changes. Moreover, this focus provides insights into productive regional branching in peripheral economies that are facing structural transformation. This is accomplished using Swedish longitudinal geo-coded employer-employee microdata, following the 670 manufacturing workers without a higher education who became redundant outside of metropolitan areas in 2003.

The contribution of the present study is twofold. First, it will add to the redundancy literature by going beyond the single point of returning to employment to create post-redundancy labour market trajectories with both a distance and a direction. Second, it builds on and adds to theories of regional diversification (Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2011) as well as proximity studies within the EEG literature (e.g. Boschma Citation2005) by including workers and their mobilities in both geographical and industrial space, as well as showing how they interact.

The present study provides empirical evidence to suggest that the distance a worker moves has a significant effect on the direction their labour market trajectory takes. Moreover, the distances used in the present paper, mobilities in the industrial and geographical space, interact and should not be analysed separately from one another. Workers who end up taking a job in the same region and industry as prior to the layoff are likely to stay on a stable labour market trajectory. Those who move away from their initial point of departure, but not too far (e.g. same industry in new region, or related industry in the same region) increase their chances of upward mobility. However, workers who move too great distances – especially into unrelated industries – increase the likelihood of not being able to re-use their cumulated competences, experiencing a skill mismatch and embarking on a trajectory in an unfavourable direction, ending up underemployed. Understanding the distance and direction of labour trajectories is critical for policymakers who wish to plan for productive re-employment opportunities for regional diversification and strategic career moves for workers facing redundancy.

The paper is structured as follows: The first part introduces a summary of the redundancy literature and an elaboration of how the proximity literature is used to categorize mobilities as distances in geographical and industrial space. The concept of labour market trajectory is then introduced, discussing how it is used to connect the notion of distance with that of direction. The third section presents the data and methods used, and the fourth provides an overview of the empirical results. The subsequent section concludes the paper.

Redundancy, labour market trajectories and skill matching

An increasing number of studies have shown that there are different experienced negative effects on workers’ post-redundancy employment. How specific individual characteristics impact chances of re-employment is a well-studied issue both in general (e.g. Eliason and Storrie Citation2006; Frederiksen and Westergaard-Nielsen Citation2007; Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan Citation1993) and more specifically, for instance, in mature sectors (e.g. Bailey, Chapain, and de Ruyter Citation2012; Eriksson, Henning, and Otto Citation2016; Oesch and Baumann Citation2015). Unemployment has negative effects on stress and well-being (Leana and Feldman Citation1995), but generally speaking, a large proportion of individuals who lose their job following plant closure cease to be unemployed within the first couple of years (e.g. Eliason and Storrie Citation2006; Gripaios and Gripaios Citation1994; Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018; Oesch and Baumann Citation2015; Tomaney, Pike, and Condford Citation1999). The redundant workers start studying, enrol in training programmes, retire or get a new job. However, people who return to work after redundancy end up in temporary positions to a larger extent (Tomaney, Pike, and Condford Citation1999) and need to accept a lower standard and wage than they had in their previous position (e.g. Gripaios and Gripaios Citation1994; Tomaney, Pike, and Condford Citation1999). In addition, they are also more vulnerable in a future crisis, meaning they will have to face redundancy once more (Eliason and Storrie Citation2006). Thus, time to re-employment may not be the greatest challenge regions and workers face after redundancy, but rather the qualitative aspects of the new employment.

Hence, the redundancy literature reveals that there are negative effects of facing larger layoffs and plant closures that are passed on into the next job after becoming re-employed. Nedelkoska, Neffke, and Wiederhold (Citation2015a) showed that earning losses related to redundancy were not due to the redundancy per se, but rather to the increased risk, associated with involuntary job separation, of becoming re-employed in a new occupation in which much of the worker's accumulated human capital is unused – so-called down-skilling. The lesson here is that we need to put more focus on skill matching between jobs in times of economic turbulence. Scholars in the sub-field of EEG have argued for the importance of studying different dimensions of proximities (Boschma Citation2005) if we are to understand skill matching in relation to the merging and creation of knowledge and innovativeness. The core idea is that all worker mobilities entail frictions, and with those frictions there are costs, but also potential benefits, e.g. knowledge creation. The level of frictions and benefits associated with a job switch depends on the characteristics of the worker's competences and the firm's knowledge base, but also on whether the new employer is able to recognize the worker's skills, understand their value and absorb these skills into the firm (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990). This match depends on a wide set of dimensions that capture how similar the workplace and the worker are, what has been termed the proximity dimensions. These dimensions have been developed by the French School of Proximity Dynamics (e.g. Kirat and Lung Citation1999; Torre and Gilly Citation2000) and further elaborated in a geographical framework proposed by, e.g. Boschma (Citation2005). Within the EEG framework, these proximities have primarily been used to measure the industry composition within a region, but also the frictions that arise due to labour mobility. It is the frictions that a worker encounters or the distance that a worker moves in geographical and industrial space that this paper will address.

Even though today's technology enables a much higher degree of spatial mobility, people rarely move greater distances if they do not have to. While there have been discourses of a hyperglobal new generation of elites, this is rarely the reality. There is a geographical ‘stickiness’ that affects all workers, due to both professional and social aspects of life. Spence, Sturdy, and Carter (Citation2018) found that even elite employees of global firms pursue their careers locally, and that even though they have transnational ties and resources, they are considered locally rooted. In the case of workers made redundant, searching for a job after being laid-off is stressful (Leana and Feldman Citation1995), and searching for one in a new labour market comes with additional costs. On the whole, people in Sweden are unlikely to move to another labour market (Fischer and Malmberg Citation2001), and those who do move are to a lesser extent (comparing 1970–2001) part of the adult population already established on the labour market (Lundholm Citation2007). This may partly be because the Swedish welfare system allows a certain degree of immobility, but also because, over time people have invested in the place and in social networks, giving rise to emotional attachments as well as professional advantages. Professionally, the ‘insider advantage’ that comes with accumulated time in a region means knowledge about informal rules and networks (Fischer et al. Citation1998) and results in an increased switching cost when looking for a job in a new region. The work of Bailey, Chapain, and de Ruyter (Citation2012) emphasizes the importance of networks for individuals’ ability to find new employment after a plant closure. This becomes even more challenging in a dual-income household, as there are two people who will need to face these challenges. In his paper on the segmented labour markets in the UK, Gordon (Citation1995) concluded that there has been a structural shift, whereby more inter-regional moves are contracted and sponsored and fewer are unsponsored. This may indicate a higher risk associated with unsponsored moves, which causes marginalized workers to be less inclined to move to a new labour market.

Turning to mobility between industries, we know that there are costs for the individual associated with moving into new economic activities. Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan (Citation1993) found that dispatched workers subjected to major layoffs experienced larger wage losses, on average, when re-employed than did the control group. However, workers who found a new job within the same industry, but not necessarily within the same 4-digit sector, showed less of a wage decrease than the people who moved from manufacturing to non-manufacturing and vice versa. Huttunen, Møen, and Salvanes (Citation2011) found similar patterns, where wage losses were most significant for labour mobility to new firms and new industries. Interview data from Bailey, Chapain, and de Ruyter (Citation2012) showed that 60 per cent of respondents employed three years after the plant closure of MG Rover Birmingham (UK) reported that their new job required a totally new skill set compared to their old one. The same figure was reported by Tomaney, Pike, and Condford (Citation1999) for the plant closure of Swan Hunter shipyard in Tyneside (UK), where 40 per cent of respondents reported feeling bitter about it. These studies show that there are frictions associated with moving into new economic activities, new employment that is unrelated to the worker's previous job. If we return to the EEG literature, the argument is that the distance a worker has to move in an industry space is due to the proximity in the skill set employed by different industries. The idea is that a worker's skills and competences can be seen as being directly in line with the tasks she is assumed to perform in the new job, or that they are so dramatically different than her accumulated knowledge is not seen as relevant at the new workplace (Neffke and Henning Citation2013). These two extremes are usually categorized such that the skills of the worker and the workplace are considered the ‘same’ or ‘unrelated’. However, as argued in the proximity literature, the cognitive distances between industries are more fluid than simply the same or unrelated, and this is the productive contribution from this strand of literature; scholars have developed the notion of ‘related’ industries (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2009; Neffke and Henning Citation2013). This is a situation where the worker has an employment background that is slightly different, but where the cognitive distance is so small that her skills and competences are easily bridged to the new workplace and can be absorbed and used. Sometimes these mergers can even result in a recombination that adds something new to the plant's existing knowledge (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2009) and is beneficial, in that knowledge is created or innovations produced. Hence, while being re-employed back into the old industry should be a safe move with regard to skill matching, a related move may be a more productive strategy for the firm and for the worker. Moreover, the present paper argues that mobility in geographical and in industrial space interact and should be analysed together. This is in line with the findings of Rigby and Essletzbichler (Citation2006), who found intra-regional similarities and inter-regional differences in production techniques within the same industry.

One investigation that tried to merge these two strands of literature, redundancy and proximity, as well as to combine geographical and industrial space, is the study by Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning (Citation2018). They looked at the re-employment patterns after major layoffs and plant closures and categorized the distance a worker had moved to be re-employed by combining the industry and regional move into six categories (same, related or unrelated industry in same or new labour market). They showed that the most popular move when returning to work was to return to the same industry, in the same region. This is not surprising, as it is easy to conclude that this move provides solid ground for skill matching. They did show, however, that different groups of workers were more likely to perform different mobilities. But concerning skill matching between the old and new job, they theoretically discussed, on the one hand, referring to flexible workers as being able to move to other industries or regions. On the other hand, they discussed the risk of workers moving too far away from their initial point of departure and, thereby, not being able to re-use their accumulated competences. They did not investigate the direction that these distances entailed. The risk we face when we fail to address the direction of these labour market trajectories is that we will confuse a flexible worker with a precarious one, and ‘ … a lack of power in the labour market / … / should not be confused with flexibility’ (Strauss Citation2018, 488). A discussion on flexibility may be applicable to a certain group of people, such as highly educated people whose knowledge is typically viewed as more adaptable (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018). Other groups may suffer more from these unrelated moves, as their knowledge is seen as more specialized, where branching into unrelated industries after major layoffs is due to changing demand rather than workers being ‘flexible’. The aim of the present paper is to investigate how distance, as used by, e.g. Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning (Citation2018), has an effect on the direction of workers’ labour market trajectories after major layoffs. This means that time to re-employment is not sufficient if we are to evaluate the costs the workers are subjected to when facing redundancy. The quality of the new employment as well as the long(er)-run effects need to be considered. A crucial point here is that it is not enough to observe a single point in time; instead we need to include time and change. One productive way to approach time and change is to use the concept of paths or trajectories.

Based on the literature on industrial and geographical labour mobility presented above, the present paper assumes that the distance a worker needs to move in industrial and geographical space (same, related or unrelated industry in same or new labour market) will have an effect on the direction of her labour market trajectory. The direction is argued to be of importance because skill mismatch or underemploymentFootnote1 has been shown to have effects on both wellbeing (Leana and Feldman Citation1995) and wage development (Holm, Østergaard, and Olesen Citation2017), as well as to affect the potential for productive regional transformation. Moreover, without addressing the direction explicitly, we cannot know whether high mobility is the result of precariousness or flexibility. Theoretically, in relation to proximity (cognitive and spatial), staying in the same industry and region will mean the smallest distance a worker has to move. This move should mean a good skill match; it is expected to be the most popular move and the most common one for workers who are re-employed quickly. However, Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning (Citation2018) showed that these moves increase the workers’ risk of facing another mass layoff within a ten-year period, probably due to initial structural problems within that sector. A related or unrelated move was safer in this respect. However, in line with the literature on proximity, moving too great distances may cause skill mismatching. Holm, Østergaard, and Olesen (Citation2017) argued that the former shipyard workers who moved into related industries experienced less ‘skill destruction’ than did those who moved to unrelated industries, which is in line with previous findings in the literature. Still, we know very little about how the industrial and spatial proximities interact and how that distance affects the direction of redundant workers’ labour market trajectories.

Data and empirical strategy

By using unique longitudinal micro-data, in the form of matched employer-employee data from Statistics Sweden, the present study is able to construct individual trajectories for workers’ labour market outcomes over time and space following a redundancy. However, it is not possible to know the actual sequences of events, as the data are recorded on an annual basis. This means that it is not possible to know when and how a worker has been employed or unemployed, as the only data are the sum of incomes and benefits for each year. Hence, to construct the sample and variables needed, different measurements have been made, as reported below.

Sample selection

To study the effects of redundancy, it is necessary to clearly define the sample, as including all job separations would mean including data comprising both layoffs due to individual productivity problems as well as strategic career moves. One way would be to only consider plant closures, as there is no selection (Gibbons and Katz Citation1991), however, this would mean an oversampling of small plants. Instead, a major layoff criterion is constructed to try to minimize voluntary job separations. The criterion is threefold: (a) at least 15 workers should be laid-off in a plant closure or downsizing and these should (b) comprise at least 50 per cent of the plant's workforce (Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan Citation1993). These closures/downsizings should not be part of any within-firm re-organization either, and therefore (c) all firms that re-employ at least 75 per cent of all workers they laid off, in the same region in the year after the observed (false) job separation, are excluded from the sample. Furthermore, a couple additional criteria have been included to narrow down the study to focus on a group of workers who are seen as particularly vulnerable and whose aim is to return to work. Previous findings have shown that it is easier for workers with a higher education to be re-employed (Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018), in combination with studies showing that there has been considerable destruction of low-skill manufacturing jobs in the whole of Sweden, while the major proportion of job creation in the service sector has occurred in the metropolitan areas (Andersson, Eriksson, and Hane-Weijman Citation2018). Hence, only (i) non-metropolitan redundancies of (ii) manufacturing workers (iii) without a formal higher education (three years or more) are included. Because age has been shown to have a great effect on redundant workers’ chances of finding re-employment and the quality of the new job, the present study focuses only on (iv) middle-aged workers (30-45 years of age), as such workers are in the prime age for developing a career, but also a common age for having family responsibilities. We do not want to include labour introduced in the downsizing phase, hence only (v) workers who have a minimum of one year of tenure in the plant before the year of the major layoff (t-1) (Fallick Citation1993) and who have a (vi) salary that exceeds the threshold of the subsistence level (Socialstyrelsen Citation2009) are included. As they are supposed to be actively committed to returning to the labour market, (vii) all individuals who retire during any year of the five-year trajectory are excluded. It is not the single point of return that is of interest here, rather we want a time frame that allows us to see the major trends in re-employment and to exclude individuals who get stuck in a spell of unemployment – which seems to be five years, according to the literature (Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018). Hence, (iix) all individuals who are not employed five years after the initial layoff (t0) are excluded. In the end, the dataset contains 670 middle-age manufacturing workers without a higher education, made redundant in major layoffs or plant closures in non-metropolitan regions in Sweden in 2003. About 80 per cent of these are men, and the majority of them (70%) have young children. These workers live all over Sweden, mainly in larger regional centres (75%), but also in smaller regional centres (19%), while only a few per cent live in small peripheral regions. Most of them worked in low-tech manufacturing industries in 2003, and the most common occupation was ‘Plant and machine operators and assemblers’. Thus, what we end up with is a group of workers who have been particularly adversely affected by the recent structural changes and who are especially vulnerable when subjected to these changes.

A note should be added that this is a period in Sweden characterized by relative stability in terms of growth, which could have an effect on the size of the sample as well as which plants and workers are included.

Independent variables

To understand the frictions associated with movement in industry space, a definition of relatedness is needed. Using skill relatedness in the way Neffke and Henning (Citation2013) did could give rise to circular reasoning because the measurement is based on labour mobility. Instead, inspired by the management literature (Farjoun Citation1994), the present paper focuses on human expertise as a resource for an industry and constructs groups of resource-related industries based not primarily on industry groups, but on employees’ occupations. The rates of different occupations within an industry are an indication of what mix of competencies is needed. By using longitudinal matched employer-employee data from Statistics Sweden (SCB) for the period 2003–2010, the number of employees in different occupations in each plant is aggregated to the industry level. The resource relatedness between different industries is then calculated in three steps: (i) create a vector of occupation shares for each industry for the whole period, (ii) measure the similarity of each pair of industry vectors by the pairwise correlation of occupation shares within them, and then (iii) categorize two industries as resource related if their occupational structures are statistically significant (5%) with a correlation of at least 0.75 (see Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018; Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018). This gives us 2812 significant links between related 4-digit industries, where about half are between manufacturing industries, half between service industries and about five per cent are between service and manufacturing. Now it is possible to categorize each industry pair as ‘related’, ‘same’ (within the same 4-digit sector code), and the rest as ‘unrelated’, see below. To give an example: a typical related move is that of moving from being in ‘Manufacturing of industrial process control equipment’ to being employed in ‘Manufacture of electricity distribution and control apparatus’. Similarly, a typical unrelated move is that from ‘Manufacture of motor vehicles’ to ‘Sales of motor vehicles’, but a common unrelated move is also that from ‘Plant and machine operators and assemblers’ to ‘Clerks’. In addition, the share of all employees in a region who belonged, at t0, to the same industry the worker became redundant from is added as a variable, as well as the share of employees in related plants (‘IndMix’).

Table 1. Variable definitions.

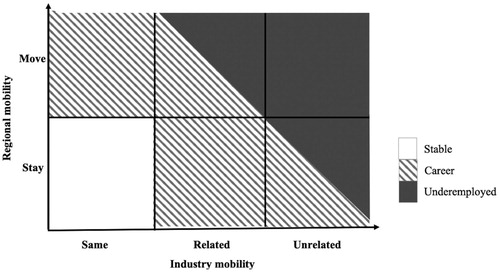

As its spatial unit of analysis, the present paper uses the functional analysis regions (FA regions) created by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth. These 72 FA regions are constructed from labour-commuting patterns between municipalities, and by considering the historic growth trends for these municipalities; they are intended to represent labour markets that are relatively coherent over time. Workers are then categorized as regional movers when they are no longer working in the same region at t+5 as they were at t0. There may of course be problems associated with not allowing space to be more fluid; workers are not simply reappearing in a new region and the intra-regional characteristics may differ considerably depending on where in the region one lives, works and travels. However, scales help make sense of the landscape. One advantage of using a categorical dummy to represent geographical space is that it is possible to capture some of the dynamics and institutional characteristics that are part of producing a place, such as business dynamics (Herod Citation2001). Because there are frictions associated with both the industry and regional move, the distance a worker moves depends on how these, industry and region, are combined (Rigby and Essletzbichler Citation2006). Therefore, a categorical variable is created, see , where information about both the regional and the industry move is combined into one (‘Distance’) (see Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018). Besides mobilities, individual controllers for occupational status (‘SIOPS’) and income (‘Income’) prior to being laid off have been included, as these factors are likely to have an effect on how employers value workers’ skills. Because previous studies have emphasized the importance of acquiring a higher education for re-employment possibilities, a dummy is included indicating whether the workers attained a Bachelor's degree during the period under study (‘HiEdu’). Variables controlling for the firm dynamics of the region at t0 have also been included: the rate of all ‘micro-’plants and ‘SME’ (see for the exact definitions) and the rate of plants that are ‘incumbents’ (not entries).

Dependent variables

In labour economics an employee is typically valued in relation to salary (Holm, Østergaard, and Olesen Citation2017; Nedelkoska, Neffke, and Wiederhold Citation2015a). However, the dataset available only has information on salary aggregated on an annual basis, and we cannot know whether the reported salary comes from, e.g. working part-time the whole year or full-time for only a month. Instead, the present paper uses occupational status change as a proxy for valuation of the worker's accumulated skills in the new job. Occupation tells us something about what a person does, but sometimes also who the person is – a role that affects her economical as well as social position (Hansen and Bihagen Citation2003). While income and education are important, it seems as though occupation adds something to the feeling of reward a worker associates with employment (see, e.g. Goyder Citation2009).

The occupational status measure used here is the SIOPS – Standard International Occupational Prestige Scale. The SIOPS is based on a ranking of occupations by respondents in 60 countries, gathered by Treiman, and later linked to the international occupational classification of ISCO-88 proposed by Ganzeboom and Treiman (Citation1996). This prestige scale for occupations is considered quite stable over time and space (Bihagen Citation2007) and has been made publicly available by Ganzeboom and Treiman (Citation2004). These SIOPS rankings have then been linked to the Swedish occupational 4-digit code (SSYK96) using Bihagen's (2007) work and weighted using data from 2006 (first year of 4-digit occupational data) to construct a mean for the occupational 3-digit occupational code.Footnote2 Occupational status seems to form a hierarchy that can have a diverse set of effects, and SIOPS has been used to study, e.g. how parents’ occupational status affects youth health (Pfortner et al. Citation2015) and sense of happiness in relation to job prestige (Di Tella, Haisken-De New, and MacCulloch Citation2010).

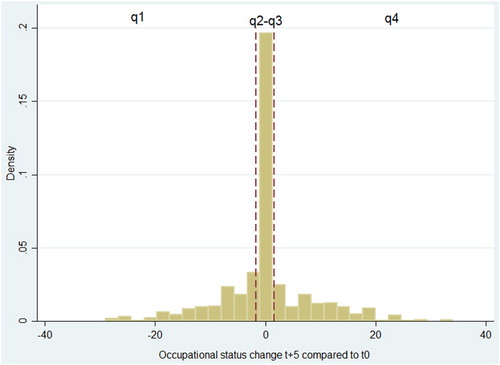

Because occupational status is a ranking, the data are ordinal rather than continuous, and the steps cannot be said to be equal independent of their positions on the scale. Hence, the aim is not to understand how the explanatory variables give rise to one step up or down on the SIOPS scale, but rather the probabilities of ending up above, under or at the same status in the medium run. Therefore, three dummy variables are created that indicates the direction, whether the worker has ended up making a career, stayed stable or become underemployed.Footnote3 To categorize different status mobilities, the occupational status change between post-redundancy employment (t0) and employment at the end of the period studied (t+5) has been used. This status change ranges from −30 to +35 points on the SIOPS scale, and each individual's status change is categorized depending on which quartile they end up in (see Appendix). The group of workers who have experienced positive status development between the two years (t0 and t+5), above 1.6 and up to 34.0 status points, end up in Quartile 4 and are categorized as making a career (‘Career’=1). The people categorized as underemployed (‘Underemp’=1) are those who have experienced a negative status change (Quartile 1) of at least 1.7 up to 29 status points. The workers who end up in Quartile 2 and 3 have almost no change in their status (−1.7 to +1.6) and are categorized as being stable (‘Stable’=1). To give a couple of examples: ‘Assemblers’ is one of the most common occupations in 2003, and a common occupation for this group in 2008 is as ‘Building and trade workers’. This means a −1 drop on the SIOPS scale, which is a ‘stable’ trajectory. Being ‘underemployed’ is typically when workers lose a manager position and end up as sales personal or machine operators, and a common ‘career’ trajectory involves moving in the opposite direction. The correlation between income and SIOPS is significant at the one per cent level at least, but a correlation of about 50 indicates that they are related, but not fully replaceable. Thus, something else is captured by using occupational status. These moves are then used as an indicator of whether or not the accumulated skills are compatible with the new job and appreciated by the employer at the new workplace.

The empirical results comprise both descriptive figures and regressions. All figures and tables concern the final sample of 670 workers made redundant in 2003 (t0) and employed in 2008 (t+5). While probabilities of binary variables are usually analysed using a logistic regression, Mood (Citation2009) managed to show that, due to unobserved heterogeneity, this estimator is more complex than is usually thought. In line with Mood's arguments, the models in the present paper have instead been estimated using a linear regression (OLS), as it is not the non-linearity of the relationship that is of interest, but the average effect and whether it is significant.

A robustness check has been carried out using a logistic regression with marginal effects. An additional option would have been to use a multinominal logistic regression with all three status mobilities. The findings of the robustness checks did not lead to any reinterpretations of the main results. Regional population size and age of the worker were included, but did not change the result and had no significant effect, probably because the population studied does not vary a great deal in these respects. Sex was included, but it did not show any significant effect. Having children may affect the mobilities these workers carry out, but no significant result was found when this variable was included in the regression, and hence it was dropped. One reason for this may be limitations in the data to accurately categorize households. Running the regressions separately for ‘IndMix’ and industrial and regional mobility did not lead to any reinterpretation of the main results.

Results

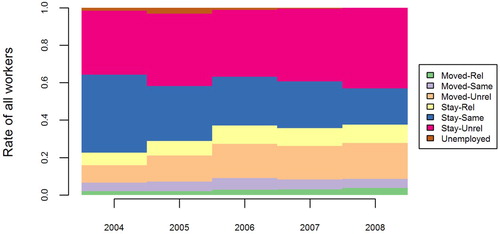

First of all, in line with previous research, a large proportion of the laid-off workers were re-employed immediately after becoming redundant (87% in t+1). After that initial year, a smaller and smaller portion of the still redundant workers found a new job. However, in the end, only about three per cent of all workers made redundant in 2003 had not found new employment during the five-year period.Footnote4 below shows the labour market outcomes over time for each year for all workers in the dataset, all categorized only in relation to pre-redundancy employment. In line with previous studies on the whole economy (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018), the figure shows that a rapid return to the same industry in the same region was the most popular move when re-employed. However, the workers in the present study return to new employment in unrelated industries to a higher degree, which is not surprising, as their pre-redundancy jobs are generally part of what is seen as belonging to the ‘old’ Swedish economy. Already in the first year after the layoff, 44 per cent were re-employed in an unrelated industry, and this figure increased dramatically over time. Two years after the redundancy, 82 per cent found their first job in an unrelated industry and all re-employed five years after the job separation did so in an unrelated industry. Only about nine per cent found a job in a related industry in 2004. However, the proportion of people in related industries increased with time if we follow the redundant workers beyond the single point of return. Because the percentage of workers within the same industry decreased over time, this might have been used as a stepping stone to branch out into new related employment. However, this group remained fairly small, and at the end of the period studied, about 62 per cent of the whole population were working in industries far from similar to their pre-redundancy employment. If we look beyond the initial point of labour market re-entry, about 25 per cent of all workers in employment were located in a plant outside their ‘home’ region in each year. In the end, even though workers found new employment relatively quickly, they continued to be pushed out, or moved voluntarily, further and further away from their initial point of departure (t0). Five years after the major layoff, most workers were employed in unrelated industries, primarily in the home region (pink category in ). In addition, at this point, an equally large percentage of the workers were employed in unrelated industries in a ‘new’ region, as there were workers who remained in their initial industry within their home region – the initially so popular same-industry-same-region move.

Figure 1. The proportion of industrial and regional moves for each year (‘Distance’), compared to t0. The x-axis shows time (in years) since the redundancy, the y-axis shows the proportions in each state.

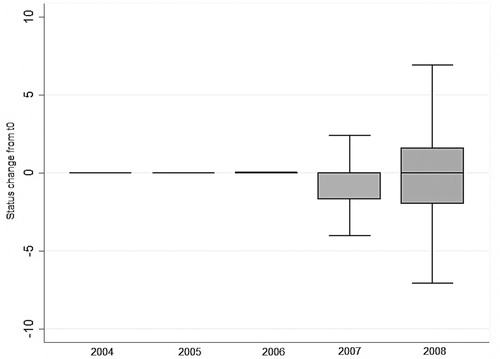

Even though returning to the same industry appears to be a desirable outcome, acquiring the same occupation seems to be a stronger force in shaping individuals’ trajectories. For the workers re-employed immediately after the layoff, 78 per cent returned to the same occupation they had prior to job separation. This percentage drastically decreased for each year the worker experienced unemployment, and for the workers re-employed in the last year of observation, none returned to the same occupation they had before the layoff. This means that the workers who found their first new job in 2008 did not perform the same tasks (occupation) or work with the same economic activity (industry) they had prior to the layoff. These layoffs triggered a time of great turbulence for the workers made redundant. Even though a high portion found new employment already in the year following redundancy, only about 30 per cent remained in the employment they acquired in 2004 until the end of the period studied. For the national average during this period, somewhat less than 10 per cent of all workers changed plant each year (Andersson, Andersson, and Poldahl Citation2014). For this group of manufacturing workers, about 28 per cent of those re-employed in 2004 changed plant and firm in 2005, if they were still employed. shows the occupational status change for all employed each year compared to the status of the pre-redundancy employment. The majority of workers re-employed already in 2004 ended up in an occupational status similar to the one they had prior to the layoff. For example, the most common occupation before redundancy was ‘Plant and machine operator and assembler’, for both women and men, which is a common re-employment occupation in 2005. However, with time we see a divergence, where an increasingly large proportion have a higher and lower occupational status than before the layoff. In 2008, ‘Plant and machine operators and assemblers’ is still the biggest single group for men, but less so compared to 2003, where new important occupations are ‘Building and trade workers’. For women, the biggest occupational group has switched to what is termed ‘Service, Care and Sales’, which encompasses occupations such as clerks, retail and housekeeping.Footnote5 This is in line with the findings of Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning (Citation2020), who showed that redundancy triggers gendered labour trajectories that reproduce a traditional segmented labour market.

Figure 2. Occupational status change for all employed each year (t+1–t+5) compared to t0 (excluding outliers).

Thus, if we look beyond the initial year of re-employment, interesting labour mobility dynamics are found with regard to occupations, industries and geographies. The present paper, therefore, focuses on the medium run, comparing pre-redundancy employment with employment at t+5, and analysing how the distance between those two points affects the direction of the individual labour trajectory. This is done in , by performing an OLS to estimate the probability of ending up in a ‘Stable’ trajectory (M1), experiencing upward mobility and making a ‘Career’ (M2) or becoming ‘Underemployed’ (M3), depending on the regional-industry mobility variable (‘Distance’). All three models include fixed effects on sector groupFootnote6 employed at t0 and t+5 as well as time of re-employment to moderate the influence of unobserved heterogeneity.

Table 2. OLS on effect from distance moved in t+5 compared to t0 on direction of labour market trajectory.

First of all, in line with the expectations, workers who managed to stay, or who ended up in the same industry and region five years after becoming redundant, are most likely to stay on a stable labour market trajectory (M1). Regarding the same-region-same-industry strategy, though a common move directly after the layoff, only about 19 per cent of all employed ‘manage’ to keep this position in the medium run. Moving some distance seems to be a good strategy for making a career (M2), and even staying in the same industry but in a new region increases chances of upward mobility. This is in line with our assumption that there is potential for productive frictions to arise when two different industry routines from different regions are merged. Moving to an unrelated industry does not necessarily mean too great a ‘distance’ for there to be fruitful merges with the new plant. If the worker can reuse the ‘insider advantage’ of staying in the region, there is potential to reuse skills in related as well as unrelated industries. However, when the worker moves too far, into unrelated industries or related industries in new regions, the frictions becomes too high and the worker risks becoming underemployed (M3). below is meant to be a visualization aid that summarizes the most important results from . The initial position, the worker's point of departure, is the bottom left corner. Staying in that corner means no distance and hence no frictions, and those workers are most likely to stay on a stable labour market trajectory. However, we know from previous studies (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018) that returning to the initial position increases the chances of facing another mass layoff. The further up and to the right in the figure, the longer the distance a worker has moved, and the greater the frictions and risk of experiencing skill mismatch. Ending up in the top-right corner entails a long move from the worker's initial position, a too great distance that will most likely result in skill mismatch and underemployment. The part in the middle, between these two corners or extremes, is where productive new mergers appear. Here, the worker has moved some distance but not too far, e.g. staying in the same industry but moving to a new region, or staying in the region but moving to a related industry, which leads the worker on an upwards trajectory and towards making a ‘career’.

Figure 3. Space of industrial and geographical distance and how it effects the direction (inspired by figure in Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018).

Finally, some notes on the control variables in are needed. The share of related economic activity at the time of redundancy has an effect on the quality of the new employment in the medium run. The presence of related industries seems to decrease the frictions of returning to work, creating favourable conditions for trajectories in positive directions (M2). While a high regional supply of the same industry has been shown to have an effect on time to re-employment (Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018), it does not seem to have a significant effect on career possibilities in the medium run. One explanation could be that even though there is a large group of workers returning to the same industry and occupation in the first year, this is not stable employment. Acquiring a higher education is associated with a higher probability of making a career.Footnote7 For firm dynamics, it seems that a high share of incumbents and a low share of entries facilitate career mobility for this group of workers. This is not only a question of size, as this is controlled for (Micro, SME). Some of this effect may be because incumbents contribute more to job creation than entries do (Eriksson and Hane-Weijman Citation2017; Essletzbichler Citation2007) as well as a problem of new entry survival (Bartelsman, Scarpetta, and Schivardi Citation2005), and incumbents may thus generate more stable career possibilities in the medium run.

Reflections and conclusions

The present paper sets out to investigate non-metropolitan manufacturing workers without a higher education, and their labour trajectories for a period of five years after becoming redundant in major layoffs and plant closures. The paper argues that this specific group of workers need particular attention as they have most often suffered the negative effects of the structural transformation occurring during recent decades. The results show that the distance a worker moves to find employment has a significant effect on the direction her labour market trajectory will head. The measures of distance travelled used here, the industrial and geographical space, interact and cannot be analysed separately from one another. This means that the effect deriving from changing industry depends on how that move is combined with geographical mobility. Workers tend to start by returning to the same region and industry as prior to the layoff – a familiar move that should in theory mean low costs. For workers who manage to keep that kind of job for the remaining period, it also means a stable labour market trajectory. However, few workers manage to remain that close to the point of departure for the five years, but most are instead gradually pushed out to unrelated industries and new labour markets. This will in theory mean long distances moved, implying the risk of skill mismatch for workers between the old and the new job. The present study also shows that moving too great distances (especially into unrelated industries) increases the risk of workers embarking on a trajectory in an unfavourable direction and ending up underemployed. However, branching away from their initial point of departure, but not too far (e.g. same industry in new region, or related industry in the same region) increases their chances of experiencing upward mobility and making a career. The same-region-same-industry move is probably the most desirable one for the worker made redundant. However, as a previous study (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018) demonstrated, returning to the same industry that experienced mass layoffs and plant closures increases the chances of the workers experiencing yet another redundancy. Hence, it is not a desirable outcome in the longer run. Rather, the present paper argues, in line with Holm, Østergaard, and Olesen (Citation2017), that switching to related industries within the home region could be seen as a process of creative destruction that benefits the individual's career, as well as the process of regional transformation.

The present study confirms high re-employment rates after major layoffs and plant closures in Sweden, in line with previous studies on the topic (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018; Hane-Weijman, Eriksson, and Henning Citation2018). Thus, on the whole, time outside the labour market might not be the greatest problem. What happens, on the other hand, is that the layoff seems to trigger a period of intense job switching, higher than the Swedish average during the period under study. The frequent plant and firm switching observed, even after the first re-employment, results in a smaller and smaller proportion of workers remaining in their original industry, region as well as occupation. This could be because they return to a vulnerable sector (Eriksson, Hane-Weijman, and Henning Citation2018), or due to a skill mismatch that means an unsatisfactory job situation, which would lead to a continued search for a new job on the side – a stressful situation (Leana and Feldman Citation1995). Job switching leads to diverging trajectories, where one group of workers experience upward mobility, ending up making a ‘career’ when they manage to branch into related economic activities enabling a match between their accumulated skills and the demand at the new plant. Another group, about a fourth of the whole population, are slowly being pushed further and further down, ending up as ‘underemployed’ and facing skill mismatch. Rather than focusing on the redundant worker returning to any employment as quickly as possible, the focus should be on her competences and finding a job with a good skill match. This is further strengthened by the findings of Holm, Østergaard, and Olesen (Citation2017), who found higher positive effects on income developments from skill-related mobility than from rapid re-employment. Turbulence and destruction are parts of the economic system. Hence, labour mobility is an essential but also potentially fruitful mechanism in the economy. Life-long learning and continuous competence upgrading need to be made part of a system for everyone on the labour market, so as to tackle structural change and facilitate workers’ transition into new but related jobs. This means that more work is needed to understand how mature and outdated economic activities are related to new ones, so that we know which labour mobilities are productive and which mean leaving accumulated skills idle – a skill mismatch.

Regional branching and industry relatedness have been addressed as key points in attempts to understand how resilient structures can be created. Regional branching refers to the introduction of new industries within a region, where related industries are more likely to emerge because new parts of the regional economy and unrelated ones are more likely to disappear (Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2011). However, very little attention has been paid to the workers who actually constitute the mobility that these transformations entail, treating labour as a passive production resource. Adaptability for the region might not be the same as adaptability for the worker. Research addressing regional diversification needs to understand the industry space from the regional but also the workers’ point of view, and the latter has been theoretically underdeveloped. When regions diversify, and old industries in the periphery of the industry space exit and new related ones enter (Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2011), it is likely that a skill mismatch will arise between the jobs created and the ones destroyed. If regional diversification is not addressed from the workers’ perspective, we will experience increasing labour polarization and regions that lack the competences needed for the development they are pursuing. Development is increasingly becoming a regional responsibility, and the spatial distribution of jobs is not thought to be a state concern. Adaptability then becomes an issue of the geography of jobs as well as the geography of power (Massey and Meegan Citation1982). For workers, this has meant a major shift in where and what kind of jobs there are. Policy addressing resilience issues in relation to regional diversification needs to acknowledge and ask the questions: related and resilient for whom and where? This is because, in line with the present findings, it seems as though the shift from the old economy to the new one is is being paid by a group of people who are being pushed into unrelated industries where their accumulated skills and competences are left idle, out of necessity rather than as a result of them being ‘employable’ and ‘flexible’.

Either we view this polarization of workers and spatial divergence as part of a discourse of competition, or we need to better combine place-based and people-based approaches, if the goal is to design inclusive policies that avoid the growing contempt felt by certain groups of people and certain places that are being excluded from the discourse of development (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). After times of economic turbulence, micro-mobilities shape not only individual labour trajectories, but also the potential for generating new regional paths (Bristow and Healy Citation2013).

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful for the comments of Anet Weterings, Therese Danley, Zoltán Elekes, Rikard Eriksson, two anonymous reviewers as well as the researchers at the School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg on previous versions of this paper. Any errors are the responsibility of the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘unsatisfactorily’ is the phrasing used in Leana and Feldman (Citation1995).

2 There are other occupational status measures, e.g. ISEI (International Socio Economic Index), which is based on groups that have similar income and education demands; CAMSIS (The Cambridge Social Interaction and Stratification Scale) – based on data on marriage between people with different occupations; AWM (Average Wage Mobility) – mean wage development for occupations within an organization (employer). The correlation between SIOPS and ISEI (0.85) as well as AWM (0.79) is high, and with CAMSIS relatively high (0.67), according to Bihagen (Citation2007).

3 The concept of underemployed is usually associated with income, but has a wider meaning as shown by Clogg and Sullivan (Citation1983), who referred to the Labor Utilization Framework (LUF). This framework has been used to study underemployment in relation to both occupational status (Friedland and Price Citation2003) and occupational mismatch (Morrison and Lichter Citation1988).

4 There is an income threshold for being categorized as employed, so these workers might have a job, but in that case, they might be, e.g. part-time jobs that do not result in an income that exceeds the subsistence level.

5 In terms of SIOPS, ‘Plant and machine operators and assemblers’ have a status score between 25.8 and 42 (where about 40% is between 35 and 37), while the status score for ‘Service, Care and Sales’ ranges from 13 to 32 (where about 50% of the workers in this group have a status score of 13).

6 High-tech, Medium-tech and Low-tech manufacturing, Primary, Other Services, KIBS (Knowledge Intensive Business Services), FIRE (Finance), EXP (Experience), Public.

7 Five people in the present sample acquire a Bachelor's degree.

References

- Andersson, F. W., J. Andersson, and A. Poldahl. 2014. “Sannolikheten att byta jobb.” In Fokus På näringsliv och arbetsmarknad hösten 2014, 55 edited by A. Lennmalm. Örebro: Statistics Sweden.

- Andersson, L.-F., R. H. Eriksson, and E. Hane-Weijman. 2018. Växande regionala obalanser. Ekonomisk Debatt 8.

- Autor, D. H., F. Levy, and R. J. Murnane. 2003. “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (4): 1279–1333.

- Bailey, D., C. Chapain, and A. de Ruyter. 2012. “Employment Outcomes and Plant Closure in a Post-Industrial City: An Analysis of the Labour Market Status of MG Rover Workers Three Years On.” Urban Studies 49 (7): 1595–1612.

- Bartelsman, E., S. Scarpetta, and F. Schivardi. 2005. “Comparative Analysis of Firm Demographics and Survival: Evidence from Micro-Level Sources in OECD Countries.” Industrial and Corporate Change 14 (3): 365–391.

- Bihagen, E. 2007. “New Opportunities for Social Stratification Research in Sweden: International Occupational Classifications and Stratification Measures Over Time.” Sociologisk Forskning 44 (1): 52–67.

- Boschma, R. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74.

- Boschma, R., R. H. Eriksson, and U. Lindgren. 2009. “How Does Labour Mobility Affect the Performance of Plants? The Importance of Relatedness and Geographical Proximity.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (2): 169–190.

- Bristow, G., and A. Healy. 2013. “Regional Resilience: An Agency Perspective.” Regional Studies 48 (5): 923–935.

- Clogg, C. C., and T. A. Sullivan. 1983. “Labor Force Composition and Underemployment Trends, 1969-1980.” Social Indicators Research 12: 117–152.

- Cohen, W. M., and D. A. Levinthal. 1990. “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1): 128–152.

- Combes, P.-P. 2000. “Economic Structure and Local Growth: France, 1984–1993.” Journal of Urban Economics 47 (3): 329–355.

- Desmet, K., and M. Fafchamps. 2005. “Changes in the Spatial Concentration of Employment Across US Counties: a Sectoral Analysis 1972-2000.” Journal of Economic Geography 5 (3): 261–284.

- Dicken, P. 2016. Global Shift. London: Sage.

- Di Tella, R., J. Haisken-De New, and R. MacCulloch. 2010. “Happiness Adaptation to Income and to Status in an Individual Panel.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 76 (3): 834–852.

- Eliason, M., and D. Storrie. 2006. “Lasting or Latent Scars? Swedish Evidence on the Long-Term Effects of Job Displacement.” Journal of Labor Economics 24 (4): 831–856.

- Eriksson, R. H., and E. Hane-Weijman. 2017. “How do Regional Economies Respond to Crises? The Geography of job Creation and Destruction in Sweden (1990–2010).” European Urban and Regional Studies 24 (1): 87–103.

- Eriksson, R. H., E. Hane-Weijman, and M. Henning. 2018. “Sectoral and Geographical Mobility of Workers After Large Establishment Cutbacks or Closures.” Environment and Planning A 50 (5): 1071–1091.

- Eriksson, R. H., E. Hane-Weijman, and M. Henning. 2020. Nedläggningars och stora neddragningars effekter på branscher och yrkesroller: en analys utifrån geografi och kön. Tillväxtanalys, PM 2020:05.

- Eriksson, R. H., M. Henning, and A. Otto. 2016. “Industrial and Geographical Mobility of Workers During Industry Decline: The Swedish and German Shipbuilding Industries 1970–2000.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 75: 87–98.

- Essletzbichler, J. 2007. “The Geography of Gross Employment Flows in British Manufacturing.” European Urban and Regional Studies 14 (1): 7–26.

- European Commission. 2010. New Skills for New Jobs: Action Now: Report by the expert group on New Skills for New Jobs prepared for the European Commission.

- Fallick, B. C. 1993. “The Industrial Mobility of Displaced Workers.” Journal of Labor Economics 11 (2): 302–323.

- Farjoun, M. 1994. “Beyond Industry Boundaries: Human Expertise.” Diversification and Resource-Related Industry Groups. Organization Science 5 (2): 185–199.

- Fischer, P. A., E. Holm, G. Malmberg, and T. Straubhaar. 1998. Why do People Stay? The Insider Advantages Approach: Empirical Evidence from Swedish Labour Markets. Discussion Paper 1952, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), London.

- Fischer, P. A., and G. Malmberg. 2001. “Settled People Don’t Move: On Life Course and (Im-)Mobility in Sweden.” International Journal of Population Geography 7 (5): 357–371.

- Frederiksen, A., and N. Westergaard-Nielsen. 2007. “Where did They go? Modelling Transitions out of Jobs.” Labour Economics 14 (5): 811–828.

- Friedland, D. S., and R. H. Price. 2003. “Underemployment: Consequences for the Health and Well-Being of Workers.” American Journal of Community Psychology 32: 33–45.

- Ganzeboom, H. B. G., and D. J. Treiman. 1996. “Internationally Comparable Measures of Occupational Status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations.” Social Science Research 25 (3): 201–239.

- Ganzeboom, H. B. G., and D. J. Treiman. 2004. International Stratification and Mobility File: Conversion Tools. http://www.harryganzeboom.nl/ismf/index.htm

- Gibbons, R. S., and L. F. Katz. 1991. “Layoff s and Lemons.” Journal of Labor Economics 9: 351–380.

- Gordon, I. 1995. “Migration in a Segmented Labour Market.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20: 139–155.

- Goyder, J. 2009. The Prestige Squeeze: Occupational Prestige in Canada Since 1965. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Gripaios, P., and G. R. Gripaios. 1994. “The Impact of Defence Cuts: The Case of Redundancy in Plymouth.” Geography (sheffield, England) 79 (1): 32–41.

- Hane-Weijman, E., R. H. Eriksson, and M. Henning. 2018. “Returning to Work: Regional Determinants of re-Employment After Major Redundancies.” Regional Studies 52 (6): 768–780.

- Hansen, L., and E. Bihagen. 2003. “Svensk Yrkesstruktur och Yrkesklassificering över tid.” In Reflektioner: perspektiv i Forskning om Arbetsliv och Arbetsmarknad: en vänbok till Bengt Furåker, edited by B. Furåker, M. Blomsterberg, and T. Soidre, 45–68. Sociologiska institutionen, Göteborgs universitet.

- Herod, A. 2001. Labor Geographies: Workers and the Landscapes of Capitalism. New York: Guilford Press.

- Holm, J. R., C. R. Østergaard, and T. R. Olesen. 2017. “Destruction and Reallocation of Skills Following Large Company Closures.” Journal of Regional Science 57 (2): 245–265.

- Holmlund, B., and D. Storrie. 2002. “Temporary Work in Turbulent Times: The Swedish Experience.” The Economic Journal 112: 245–269.

- Huttunen, K., J. Møen, and K. G. Salvanes. 2011. “How Destructive Is Creative Destruction? Effects of Job Loss on Job Mobility, Withdrawal and Income.” Journal of the European Economic Association 9 (5): 840–870.

- Jacobson, L. S., R. J. LaLonde, and D. G. Sullivan. 1993. “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers.” The American Economic Review 83 (4): 685–709.

- Kirat, T., and Y. Lung. 1999. “Innovation and Proximity: Territories as Loci of Collective Learning Processes.” European Urban and Regional Studies 6 (1): 27–38.

- Leana, C. R., and D. C. Feldman. 1995. “Finding new Jobs After Plant Closing: Antecedents and Outcomes of the Occurence and Quality of Reemployment.” Human Relations 48 (12): 1381–1401.

- Lundholm, E. 2007. “Are Movers Still the Same? Characteristics of Interregiojnal Migrants in Sweden Between 1970-2001.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98: 336–348.

- Lundquist, K.-J., Olander, L.-O., 2010. Growth Cycles – Transformation and Regional Development, 50th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Sustainable Regional Growth and Development in the Creative Knowledge Economy,” Jönköping, Sweden.

- Massey, D., and R. Meegan. 1982. The Anatomy of Job Loss; The How, Why and Where of Employment Decline. New York: Routledge.

- Mood, C. 2009. “Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82.

- Morrison, D. R., and D. T. Lichter. 1988. “Family Migration and Female Employment: The Problem of Underemployment among Migrant Married Women.” Journal of Marriage and Family 50 (1): 161–172.

- Nedelkoska, L., F. Neffke, and S. Wiederhold. 2015a. “Skill Mismatch Affects Life-Long Earnings P5_20150922.pdf>.” Policy Brief, Proceedings of LLLight’in’Europe Research Project.

- Nedelkoska, L., F. Neffke, and S. Wiederhold. 2015b. Skill Mismatch and The Costs of Job Displacement, American Economic Association Annual Meeting. Boston, Massachusetts.

- Neffke, F., and M. Henning. 2013. “Skill Relatedness and Firm Diversification.” Strategic Management Journal 34 (3): 297–316.

- Neffke, F., M. Henning, and R. Boschma. 2011. “How Do Regions Diversify Over Time? Industry Relatedness and the Development of New Growth Paths in Regions.” Economic Geography 87 (3): 237–265.

- Oesch, D., and I. Baumann. 2015. “Smooth Transition or Permanent Exit? Evidence on job Prospects of Displaced Industrial Workers.” Socio-Economic Review 3 (1): 101–123.

- Pfortner, T. K., S. Gunther, K. A. Levin, T. Torsheim, and M. Richter. 2015. “The Use of Parental Occupation in Adolescent Health Surveys. An Application of ISCO-Based Measures of Occupational Status.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 69 (2): 177–184.

- Rigby, D. L., and J. Essletzbichler. 2006. “Technological Variety, Technological Change and a Geography of Production Techniques.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (1): 45–70.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “Commentary: The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to do About it).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024.

- Socialstyrelsen. 2009. Normer för ekonomiskt bistånd för socialbidrag, 1985–2005, Article number 2009-9-24.

- Spence, C., A. Sturdy, and C. Carter. 2018. “Professionals with Borders: The Relationship Between Mobility and Transnationalism in Global Firms.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 91: 235–244.

- Strauss, K. 2018. “Precarious Work and Winner-Take-all Economies.” In The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, edited by G. Clark, M. Gertler, M. Feldman, and D. Wójcik. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 485–498.

- Tomaney, J., A. Pike, and J. Condford. 1999. “Plant Closure and the Local Economy: The Case of Swan Hunter on Tyneside.” Regional Studies 33 (5): 401–411.

- Torre, A., and J.-P. Gilly. 2000. “On the Analytical Dimension of Proximity Dynamics.“ Regional Studies 34 (2): 169–180.