ABSTRACT

The article examines Finnish forest suburbs in the 1940s–1960s. We highlight the role of landscape architecture – a dimension that has received limited attention. Suburban landscapes have largely remained as an invisible background of modern architecture without design history of their own. Our article focuses on forest landscapes and discusses how they were conceptualized and implemented by urban and landscape planners. With the case studies of Tapiola and Vuosaari, we demonstrate that forests were not neutral and ‘natural’, but culturally constructed and carefully designed. We look at the construction of nature in landscape architecture and show how suburban forests were amenitized by recreation facilities and embedded with moral and restorative aspirations. In both cases, nature was the starting point; however, the design approaches evince clear differences. In Tapiola, the aim was the aestheticization of the forest – enhancing nature with design interventions – whereas in Vuosaari, the focus was on the natural state. Forests were regarded as a specifically Finnish landscape, which rooted rural migrants to their new home. The national dimension was also manifested by using native biotopes and tree species. Finnishness was consciously constructed, and modern living in the forest became the national and international icon of urban planning.

Introduction

Today the idea is no longer to have ‘parks in cities’ but ‘cities in parks’, in other words, buildings within nature. Thus, courtyards and plots, together with the adjoining unbuilt areas, fuse into one coherent garden city in which people and nature can once again coexist so that the freshness and joy of life can return to cities from which urbanization had almost banished them. (Meurman Citation1947, 367)

Our article focuses on the forest suburb’s characteristic immediacy to nature and the suburban forest landscape. An important premise is the cultural and designed dimension of the landscape – an aspect that has been largely bypassed by research. Although the forest and the city are often regarded as conceptually each other’s opposites – as nature and culture – in the forest suburb, nature and culture were intertwined. Geographers and environmental historians have long been interested in understanding the ways in which nature is produced by complex and interacting social and ecological processes (e.g. Braun and Castree Citation1998; Harvey Citation1996; Latour Citation1993; Kaika Citation2004). Similarly, suburban forests are not wild and untouched as often depicted but urbanized, designed and managed. This approach materialized in landscape architecture, in the aims to preserve and manage existing nature whilst also constructing new nature. Suburban forests were produced in both concrete and conceptual terms. Thus, they represent not only a geographic location and a material form but also an investment with meaning and value – they were constructed, narrated, perceived and imagined (Gieryn Citation2000, 464–465).

In Finland, post-war residential planning and suburbs have been studied a great deal with a focus on urban planning and architecture (e.g. Mikkola Citation1972; Hurme Citation1991; Nikula Citation1994; Hankonen Citation1994; Saarikangas Citation2002; Tuomi Citation1992, Citation2003). However, the research has largely bypassed landscapes that have been overshadowed by architecture. As Peil (Citation2014, 37) notes, landscape and nature tend to be generally considered as a category of conceptions that act as a background. Moreover, even though forests have received a lot of attention in research, the focus is on the history of forestry (e.g. Kotilainen and Rytteri Citation2011; Lisberg Jensen Citation2002), not on the role of forests in urban history. The absence of planning is also evident in the research of forests. As Laszlo Ambjörnsson et al. (Citation2016, 111) note ‘Planning may consequently be regarded as constituting a blind spot in forest discourses, evidencing not only the fragmented nature of discussions on forests but also the limitations of these discussions’.

Therefore, the main motivation for this article is the identified knowledge deficit concerning the suburban forest landscape created by planners and architects. We want to highlight the often invisible landscapes of forest suburbs and diversify the interpretations of their relationship to nature. We aim to demonstrate that the forest is not only background but an integral part of the forest suburb and its scenic, recreational and cultural values. In the broader context of studies on urban nature, we propose that our landscape architectural approach can contribute to the understanding of the suburban forest as a designed and managed space with multiple meanings in modernist urban planning.

The research theme is topical and has practical implications for urban planning. Sparse forest suburbs are currently threatened by densification, which started in the Helsinki Region in the 2000s. Densification reflects the prevailing compact city thinking, which advocates urbanity and dense urban structure. The forest landscapes of the suburbs are regarded as anti-urban, not appropriate in dense city with urban squares and pocket parks (Hautamäki Citation2019, 27). Architect Leena Makkonen describes the threats of densification facing forest suburbs and their characteristic values: ‘The sparse city structure may be seen as wasteful land use with the intermediate areas and buffer zones considered as wasteland without an understanding of the primary idea behind forest towns. Suburban areas must not be allowed to wilt but they must also not be choked through densification’ (Makkonen Citation2011, 68–69). Thus, densification and the pursuit of urbanity endanger the core characteristics and values of forest suburbs – their sparse and lush environment.

The threats to post-war residential landscapes have received increasing attention also more widely across the Nordic countries. In many places, residential areas are facing new challenges, such as densification, social segregation, changing uses and the impacts of climate change (Jessen and Tietjen Citation2017, 1673–1674). In this new situation, landscapes have been transformed without sufficient consideration for their cultural values and spatial qualities. As Nymoen Rørtveit and Setten (Citation2015, 955) note ‘Housing estates are rarely considered as specific landscapes with particular histories, social and physical fabrics, let alone considered of relevance to heritage debates’. They are rather regarded as a failure of modernist planning and architecture, requiring to be fixed by renewal and densification. However, lush forest suburbs are appreciated by residents and are an established part of urban history. Therefore, more knowledge on post-war landscapes is needed in order to recognize and preserve their qualities.

Finnish forest suburbs

The article examines the landscape architecture of Finnish forest suburbs in the 1940s–1960s. We discuss the meanings that were assigned to suburban forests by urban and landscape planners. How was the ideal nature of the forest suburbs produced and what was the role of suburban forests in post-war modernist urban planning? We use the internationally well-known Tapiola in Espoo and Vuosaari in eastern Helsinki as our case studies (). We explore their urban planning and especially landscape planning, for example, the works of the garden architect Jussi Jännes (1922–1967) in Tapiola and the landscape architect Katri Luostarinen (1915–1991) in Vuosaari. In both city districts, landscape architecture played a crucial role – it defined the ecological basis of the urban structure and articulated the architecture of the outdoor spaces.

Figure 1. The location of case study areas Tapiola (left) and Vuosaari (right). Source: National Land Survey of Finland.

In this article, the central concept of the forest suburb refers to the sparse and forest-rich post-war suburban model in the 1940s–1960s. The model began with Tapiola of the 1940s and continued to suburban development of the 1950s and 1960s, such as Vuosaari, and finally ended with the establishment of the dense, compact city model, which overrode the principles of sparse forest suburbs. Our definition of the forest suburb follows Kirmo Mikkola’s (Citation1972) notion of the forest suburb – or forest town (metsäkaupunki) as he calls it – coinciding with late-functionalism. However, we use slightly different timeframes. In Mikkola’s definition, the period of the forest suburb starts already in the 1930s, along with Alvar Aalto’s Sunila residential area, which, according to Mikkola, represented the prototype of the forest town. In our own timeline, we lean on a significant turning point in World War II and the launch of the actual suburban development and post-war reconstruction. Tapiola represented the start of this era. We also use a slightly different endpoint than Mikkola. Mikkola regards Kortepohja local detailed plan designed in 1964 in Jyväskylä as the end of the forest suburb era while we highlight that the construction of forest suburbs continued until the end of 1960s as the example of Vuosaari demonstrates.

The concept of forest suburb is context-dependent and far from univocal. In the compact city thinking, the forest suburb provokes pejorative associations referring to lacking traffic connections and public services and missing urban qualities (Roivainen Citation1999, 12). On the other hand, forest suburbs also entail positive associations: the close link to nature and their lush and sparse urban environment (e.g. Saarikangas Citation2002, 490–494). The notion of forest suburbs also has several parallels. For example, Tapiola is commonly called a garden city inspired by the international garden city movement. However, according to Mikkola, Tapiola did not actually follow the social, political or structural ideas of the garden city (Mikkola Citation1972, 101, 105–108). Moreover, Mikkola and several scholars use the notion of forest town as a synonym to forest suburb even though residential areas were not independent ‘towns’ or settlements. Additionally, the concept of the forest suburb has been rather freely applied in general. The notion is commonly attached in everyday language to suburbs in forested areas in general and not just to a specific style or period. In this article, we use the concept of forest suburb, highlighting the era of Finnish post-war suburban development of the 1940s–1960s and its main characteristics – the sparse urban planning ideal based on functionalism and its close link to nature and forest landscape.

The context of our study is Finland; however, we acknowledge that the model originated in the synthesis of several international influences, especially the works of Ebenezer Howard, Clarence Perry and Lewis Mumford (Hurme Citation1991, 174–175). The model also has interesting parallels in the Nordic countries. In Sweden, the fusion of functionalism and the social-democratic idea of the people’s home contributed to the construction of suburbs in the 1930s–1950s, characterized by carefully designed parks and green areas (Andersson Citation2000, 61–75; Nilsson Citation2006). Especially Friluftsstaden in Malmö, Guldheden in Gothenburg and Vällingby in Stockholm were internationally well-known, also among Finnish urban planners and architects (von Hertzen Citation1946; Tuomi Citation1992). Similarly, in Norway, modernist planning adopted the principles of the garden city into new town ideas (Brown and Luccarelli Citation2012, 122). However, it is interesting that the notion of the forest suburb was not used in Sweden or Norway for the post-war new towns. For example, Vällingby – the Swedish emblem of the 1950s’ new town – was called a satellite city or an ABC community, with the letters referring to the Swedish words for work, dwelling and centre (Hall Citation2005, 110). The neighbourhood (grannskap) was at the heart of the Swedish suburban development, which was evident especially in the aim to locate services in connection to residential areas and the design of communal yard spaces. Saarikangas (Citation2002, 388, 391) highlights the key difference between Finnish and Swedish suburbs: in Finnish planning, nature was emphasized, whilst in Swedish urban planning, the neighbourhood and the community were more important factors in the design of residential areas.

Analysing suburban forest landscapes

The landscape is a process of continuous interaction in which nature and culture both shape and are shaped by each other. Thus, the relationship between culture and nature constitutes the core of the study of landscapes (Wylie Citation2007, 9). Similarly, the focus of this article – suburban forests – are at the intersection of culture and nature, the human and non-human. They can be seen as ecological entities but also as social and cultural constructions (Konijnendijk Citation2018, 14). This is also evident in the origin of the word: On the one hand, the forest is derived from the wilderness, for example, Wald in German, and on the other, it has a distinct cultural component, for example, the Latin foris, that is, ‘the area that lies outside the normal laws’ (Rackham Citation2004, 164; Konijnendijk Citation2018, 3). Similarly, in the Finno-Ugric proto-language, metsä – forest – has presumably referred to an edge or fringe, something far away from humans (Itkonen Citation1959, 141). Thus, both the human and the non-human – wilderness and culture – are present in the suburban forest of this study.

The landscape of forest suburbs is understood both as a biophysical and conceptual phenomenon. As a biophysical entity, it refers to housing set in a matrix of vegetation – ‘nature’ – that is different from urban green space, which is usually patches of vegetation set in a matrix of the built environment (Cadieux and Taylor Citation2013, 2). At a conceptual level, the suburban landscape is a kind of middle landscape, designated by Marx (Citation1964), referring to environments between the built up city and the country, combining the best of both worlds, where inhabitants have access both to nature and to the modern conveniences that the city provides (Cadieux and Taylor Citation2013, 7; Cadieux Citation2013, 271). The middle landscape has inspired generations of urban planners around the world, starting from Howard’s garden city of the late nineteenth-century and continuing to suburban settlements of the twentieth century, with the forest suburbs of the 1940s–1960s as its Finnish application.

The study positions itself in landscape architecture, highlighting the dimension of the design of suburban landscapes. Landscape architecture reflects the interplay between nature and culture, synthesizing heterogeneous knowledge derived from a variety of fields – natural, technical, life and social sciences – into spatial entities. The temporal and material contexts in which landscape architecture operates require a constant reinterpretation of the changing nature motifs (Braae and Steiner Citation2019, 1). Design is a social, artistic, technical and political process. It entails conceptualization and framing – organizing ideas into a structured whole, highlighting some issues while excluding others (Asikainen and Jokinen Citation2009, 353; Fischer Citation2003, 143). The capacity to tell stories and envision the future is a fundamental dimension in design. According to Whiston Spirn (Citation2007, 64), design as ‘a way of imagining and telling new stories and reviving old ones, a process of spinning out visions of landscapes, alternatives from which to choose, describing the shape of a possible future’.

In this article, we study the construction of nature in landscape architecture, acknowledging that the notion of nature refers at the same time to a physical place and its natural elements and the ideals and concepts representing the relationship between nature and humans (e.g. Wylie Citation2007, 10–11). Our analytical starting point is that nature must be analysed both as a material and cultural construction. This approach is inherent in landscape architecture which materially constructs and conceptually interprets nature in planning documents, texts and drawings. According to Swyngedouw (Citation2004, 20), ‘the production of nature includes both the material processes, as well as the proliferation of discursive and symbolic representations of nature’. The approach is also evident in political ecology, which combines historical-materialist analyses of the production of nature and representational analyses of these contexts (Bunce and Desfor Citation2007, 253).

We study the construction of nature with two case studies. Case studies and the related multiple sources allow the exploration and understanding of complex issues. Case study methodology in historical research provides an example or exemplification used to demonstrate, exemplify and illustrate or alternatively contradict a claim or thesis (Petrina Citation2020, 1). According to Smulyan (Citation1994): ‘examining a small piece can illuminate the whole’. We use Tapiola and Vuosaari as such pieces to illuminate and explain the phenomenon of the forest suburb. The justification for the selection of the two cases is twofold: first, the two cases represent the beginning (Tapiola) and the end (Vuosaari) of the forest suburb era. Second, in both cases, landscape architecture played a central role, and the cases provide an archive material to study landscape design. As case study methodology in general, we aim to generalize the results on the basis of the empirical material and test hypotheses and develop new explanations (Mills, Durepos, and Wiebe Citation2010).

The empirical basis of the article is the qualitative content analysis of landscapes and related planning discourse. Qualitative analysis and case study methodology emphasize acquiring information from multiple sources and comparing different data sets (Mills, Durepos, and Wiebe Citation2010). Our analysis of the sources was based on the triangulation of the plans, written material, historical photographs and fieldwork. The archive sources, combined with the literature, have been approached methodologically through close reading, analysis and contextualization. Through the close reading of this material, we have searched for meanings and key themes and narratives and aimed to organize the data in a compact and clear manner.

The source material for our article includes planning and particularly landscape design documents in the archive of the Museum of Finnish Architecture and administrative statements related to the case areas as well as contemporary accounts that supplement the material. The key sources consist of urban plans by Otto-Iivari Meurman (Tapiola) and Olof Stenius (1907–1968) (Vuosaari) and landscape designs by Jussi Jännes (Tapiola) and Katri Luostarinen (Vuosaari). Plans and drawings constitute a specific source, described by Corner (Citation1992, 265), as ‘a translatory medium which enabled the figuration of an imaginary idea into a visual/spatial corporeality embodied in the built fabric of the landscape’. We use multiple datasets in order to complement our interpretations: for example, books and articles by the planners. We acknowledge the limitations of our source material. The written explanatory material is scarce in Tapiola and Vuosaari, as is the case in general in the historical research in landscape architecture. For example, plans and designs seldom include any explanations of design aims. Moreover, archived material is often deficient, as only a part of planning documents is archived.

The landscapes themselves constitute another key source as the end products of the designs and urban plans, depicted in photographs and observed in the field. The ideas embedded in the designs and plans have been materialized in residential areas and their parks, courtyards and recreational areas. Photographs in Espoo and Helsinki City Museum and field visits have complemented the information acquired from plans and designs. The conceptual dimension of the designs and plans also pertains to landscapes. Corner notes (Citation1992, 243) that ‘landscape architecture is conceptual, schematizing Nature and humankind's place within, but at the same time it differs from other landscape representations in that it operates through and within the medium of landscape itself’.

Forests in Finnish urban planning

The Finnish forest is a precious fortune, so precious that without its forests this country would be unfit for human habitation. Forests are needed as firewood, building material for homes, fences, bridges, ships and many other purposes. Forests protect the country from cold winds and the sudden changes between warm and cold. [… .] Thanks to these features, the forests are the coat of the country. A country this far north needs good winter clothes but if it strips of its coat, it can but blame itself for freezing. (Topelius Citation1876, chapter 46)

Zacharias Topelius’ Boken om Vårt Land (Citation1876), a book for school pupils about Finland’s provinces, nature and people, encapsulates the dependency of humans and forests. Over a hundred years later, Finnish people’s relationship with forests is still a strong narrative and has been acknowledged as a significant intangible heritage, characteristic of Finland (//metsasuhteita.fi/elava-perinto). There are many explanations for the special status of the forest in Finland: it is the most forested country in Europe, and 50 per cent of Finns live a maximum of 200 metres from a forest, and more than two-thirds of Finns exercise weekly in nature (//wiki.aineetonkulttuuriperinto.fi). Forests hold a key role in nature conservation and are pivotal to the economy. Finland has built its vision of national success on forest resources. Securing wood supply for the forest industry has remained the principal aim of the national policy from the nineteenth-century until the present day (Takala et al. Citation2019, 1). Nature and forests are the central building blocks of nationalism in Finland, which is evident, for example, in the forest imagery of national art and literature.

The Finnish relationship to forests embodies multiple discourses. In the suburban context, the discourses differ from the traditional production-oriented view, characteristic of societies with a long history of intensive forestry (Berninger, Kneeshaw, and Messier Citation2009). Along with suburban development, forests were urbanized and transformed into recreational forests, a new typology of urban green space. In the recreation discourse, the idea was to boost the recreational qualities of forests to meet the locals’ needs. This new approach to forests was manifested by new concepts, such as park forest and recreational forest (Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus Citation1968, 11; Lehto Citation1990, 96). The approach to urban forests was largely practical and based on economic arguments. It was cheaper and more efficient to develop forests into parks instead of wasting money on constructing new parks (Lehto Citation1990, 91; Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus Citation1966, 10). The amenitization of nature was a key component: the forest department, in collaboration with the sports and recreation department, built recreation services in forests as per the wishes of locals (Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus Citation1966, 11).

Another discourse characteristic of suburban forests addresses nature conservation. It is notable that nature conservation did not only concern conservation of unique natural areas and rare species but also environmental education provided to locals (Lehto Citation1990, 119). Forests were an object of vandalism: after the war, many trees were chopped for firewood, and later, as a result of increasing camping, wood was used for bonfires and rubbish was left in the forests (Lehto Citation1990, 85, 101; Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus Citation1966, 11). These problems were tackled by adding supervision in the forests and providing guidance and education: the aim was to change the residents’ attitudes through campaigns and notices and to highlight the role of urban forests as a shared asset that needed to be treasured (Lehto Citation1990, 108, 110; Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus Citation1966, 11).

Forests hold an important place also in architecture. Pallasmaa speaks about specific Finnish forest culture, which is evident both in building design and the urban planning of residential areas. He states that the main feature in architectural history in Finland is the modification of international styles, developed for more southern cultures and climates, into the style of forest culture (Pallasmaa Citation1987, 451). This also applies to Finnish functionalism. After the purist beginning, functionalism started to adjust into more of a ‘forest style’: the utilization of Finnish wood and peasant tradition and the spatial arrangement of placing buildings organically within a forest landscape replaced strict geometry and universal white architecture (Pallasmaa Citation1987, 448–449; Mikkola Citation1972, 74). Particularly Alvar Aalto’s work in the 1930s with its free form anticipated the ‘architecture of the forest’, which was attuned to nature (Mikkola Citation1972, 190; Louekari Citation2006, 196). In Aalto’s well-known Villa Mairea built in 1939, the forest continues inside the building, and its freely grouped pillars resonate with the pine trunks in the surrounding landscape (Pallasmaa Citation1987, 449). Respectively, the residential area designed by Aalto for the Sunila factory site in 1936–1939 is regarded as a prototype of the forest town in which the buildings have been placed in the forest landscape in a fan formation with an aim to preserve nature (Mikkola Citation1972, 74, 190). Both works reflect the regional adaptation of the international and urban principles of modern architecture and the interpretation of the characteristic patterns of Finnish forest types (Pallasmaa Citation1987, 451–452).

Although Aalto’s Sunila in the 1930s already manifested features of the forest suburb, the actual model was only established after World War II. Post-war reconstruction became a national project during which agricultural Finland transformed into a more modern, industrialized and urbanized nation. At the centre of the national project was suburban development, which became the predominant planning paradigm for several decades (Hirvensalo Citation2006, 98–99). The main ideological bases for the suburban development were functionalism, decentralization and the garden city ideology. The most significant international influences were the garden cities by Ebenezer Howard, the New Towns in England and the Siedlung residential districts in Germany. Clarence Perry’s theory on suburbs, Le Corbusier’s futuristic urban visions and Lewis Mumford’s ideological anti-urbanism were also reflected in Finnish planning (Hurme Citation1991, 12–54). The most significant advocate for the suburban theory was professor Otto-Iivari Meurman, an influential figure in urban planning, who also designed the first local detailed plan of Tapiola in 1945. Meurman’s suburban ideas are encapsulated in his book Asemakaavaoppi (Urban Planning Handbook, Citation1947), according to which housing was to be organized in separate communities surrounded by green zones, with the communities then divided into neighbourhood units and further into smaller residential units (Meurman Citation1947, 78–79).

The suburbs outside the city centre, in forested landscapes, combined modern architecture and a strong link to nature. The forest suburb encapsulated the criticism of metropolises. The densely built city centres were regarded as unhealthy environments which were lacking in sunlight, fresh air and morals (Saarikangas Citation2002, 78–79). The anti-urbanism of suburbs continued the late nineteenth-century interpretation of cities as the home of evil where people only ended up out of absolute necessity (Saarikangas Citation2002, 79; Haapala Citation2007, 59). Thus, the forest suburb was a morally and hygienically healthier alternative to the city centre. It also embodied a symbolic dimension: the proximity to nature and particularly to forests provided a direct connection to the homes and roots of rural emigrants (Saarikangas Citation2008, 149). The forest suburb strongly reflected the idea that the core of Finnish residential culture was in nature, not urbanism, whose history has traditionally been considered short and culturally thin. The urban structure was also visually hidden: the aim of the forest suburb was to conceal the architecture in the forest and preserve the residential environment as untouched as possible (Saarikangas Citation2002, 388). The landscape, topographical features and vegetation, as well as the configuration of buildings, were carefully considered in urban planning.

Tapiola – the suburb in designed nature

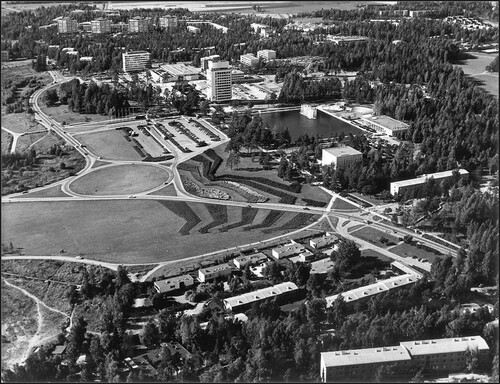

Tapiola manifests the starting point of the forest suburb era, which summed up the connection between Finnish architecture and nature. The connection to nature was highlighted even in the name given to the new district, which refers to the realm of Tapio, the king of the forest in the Finnish national epic, Kalevala (von Hertzen and Itkonen Citation1985, 53). Tapiola's relationship with nature had Finnish roots, but it was also based on international garden city models, and topical inspiration was found in, among other places, Sweden, for example, Guldheden in Gothenburg (von Hertzen Citation1946, 48–61; Tuomi Citation1992, 41; Byman and Ruokonen Citation2009, 5). As seen in aerial photographs (), Tapiola combined two of the key principles of garden cities: the open block structure of modernism and the close proximity to nature. Just as its garden city models, it offered a spacious alternative for the narrow and gloomy stone blocks in the city centre and the monotonous districts of detached houses.

Figure 2. The evolution of Tapiola, presented in aerial photographs 1950 and 1969. Source: CitationOrtophotographs of Helsinki. City of Helsinki.

As a suburban model, Tapiola was exceptional in many ways. The planning and construction were implemented by Asuntosäätiö, a non-profit organization established for that purpose, with Heikki von Hertzen as its managing director. The residential area for 30,000 inhabitants was situated on the cultural landscape of Hagalund Manor (). The planning and design of the area were given to Finland’s leading architects, and the work involved many experimental designs, for example, on different flat and house types. Simultaneously, Tapiola became the first Finnish residential area in which landscape architecture had a key role and where garden and landscape architects participated extensively in the planning alongside architects and engineers. Carefully designed green spaces, designed by landscape and garden architects, contributed significantly to the identity of Tapiola (Ruokonen Citation2003; Hurme Citation1991). Tapiola also had a wider impact: it opened the doors to landscape architecture in Finland and provided a model that was followed in later suburban development.

The starting point for design in Tapiola was preserving nature, and natural surroundings were given particular attention in the detailed local plan as well. Professor Meurman, who produced the first plan for Tapiola in 1945, left the forested hills and highest slopes in their natural state as unbuilt areas and kept the largest meadows as parks. Moreover, his street plans followed the old gravel roads, thus emphasizing and preserving the existing trees and forest fringes (von Hertzen and Itkonen Citation1985, 36–38, 45; Mannerla-Magnusson, Donner, and Raassina Citation2016, 139). Tapiola was a protest against ‘ruler-drawn street grids’ and densely built urban jungles (von Hertzen and Itkonen Citation1985, 6). Meurman stressed the naturalization of the city and envisaged the ideal town as one in which nature dominates the creations of man. Buildings and throughfares were subordinate to the natural environment, and the aim was to even hide the architecture in the shelter of the forest. Meurman’s successor, architect Aarne Ervi, who managed the planning of the area from 1954, followed his predecessor’s guidelines. The practical construction was to ‘preserve nature without fail and to avoid any unnecessary tree felling’ (von Hertzen and Itkonen Citation1985, 51).

The close link to nature was not only about preserving and respecting the existing landscape but also about creating a healthy living environment. Asuntosäätiö, which steered Tapiola’s development, emphasized the importance of a good living environment, particularly for families with children. Families have been the focus of the social debate since the early twentieth century. Asuntosäätiö’s managing director Heikki von Hertzen put families at the centre of the post-war urban development (Saarikangas Citation2002, 71). He published a pamphlet in 1946 called Koti vaiko kasarmi lapsillemme (Homes or barracks for our children), in which he voiced his concern about the detriments of dense urban structures as a growing environment for children. Von Hertzen wrote about the home as the heart of society and the precondition for its health: ‘A good home, particularly when it is in the right and suitable environment, creates the best possible grounds for the positive development of individuals and through that the entire society’ (Citation1946, 5–6). Von Hertzen stressed that too dense a living environment would bring with it ‘social diseases, generate crime and immorality and increase alcoholism and vagrancy’ in addition to other problems that weaken society and its people. A carefully designed residential environment reflected the progressiveness of the nation (Citation1946, 5–6).

A healthy living environment also embodied outdoor activities. Meurman wrote about the healthiness of the environment and emphasized the residents’ opportunities ‘to spend time and exercise outdoors in fresh air close to nature to remain mentally and physically active and to allow people to develop into well-adjusted and well-rounded members of society’ (Meurman Citation1947, 12–13). The amenitization of nature was materialized in the versatile facilities, especially designed for families and children. Tapiola’s socio-utopian character was highlighted by the aim to design an egalitarian environment where professors and factory workers could live side by side (Saarikangas Citation2002, 398–399).

Landscape architecture was a crucial means in materializing von Hertzen’s and Meurman’s ideas of a healthy living environment near nature. Tapiola’s landscape architects included Nils Orento, Erik Sommerschield and C. J. Gottberg as well as Jussi Jännes as the most productive of them (Byman and Ruokonen Citation2009, 67–71). Landscape architecture conveyed the idea of the interplay between nature and culture. Preserving the area’s natural character was the basis of the design (Jännes Citation1964, 4). However, the cultural dimension of landscape architecture also highlighted design interventions: transforming nature, supplementing its characteristics and contrasting natural features with design elements.

This approach is evident in the design of the large parks, particularly Leimuniitty with its striking ornamental vegetation, planned as its transport hub and Silkkiniitty pastoral landscape, designed for leisurely activities and recreation ( and ). The contrast between existing forest landscape and landscape design is also manifested in the yard for the Länsikorkee blocks of flats. Garden architect Jussi Jännes created an interplay between nature and modern tower houses, designed by architect Viljo Revell (). The original plans for the site show how Jännes implemented design interventions in the rugged rocky landscape. He used colourful horticultural garden plants, for example, red-leaved barberries in rock crevices and creeping phloxes with its scarlet flowers. The contrast between nature and culture was also evident in the bigger picture: the white, statuesque tower blocks rise above the dense forest when looking over towards the sea.

Figure 3. Tapiola garden city and its large designed parks and white modernist architecture amid forests. Photo: Atte Matilainen, Museum of Finnish Architecture.

Figure 4. Silkkiniitty park and its aestheticized and amenitized nature, designed by Jussi Jännes. Photo: Teuvo Kanerva, between 1960 and 1969, Asuntosäätiö Archives/Espoo City Museum.

Figure 5. Länsikorkee residential area by Jussi Jännes and the designed forest contrasting the monumental tower houses. Photo: Teuvo Kanerva, 1966, Espoo City Museum.

Landscape architecture was a means to spatially articulate the open block structure and fluid space, characteristic of functionalism. In Tapiola, the urban space formed a continuum of open, semi-open or enclosed spaces in which residential buildings were hidden within forested enclaves following the topography of the terrain. The model for the spatial concept was Friluftsstaden in Malmö where the boundary between private, part-public and public was subtle. The yards were not enclosed spaces inside the blocks as was the tradition but connected seamlessly into the public space. The forest functioned in Tapiola as a gentle transitional zone between private yards and shared, public areas. The planning for Tapiola’s first centre, the so-called Itäkartano, was a model example of the spatial structuring described above (Saarikangas Citation2008, 149–150). The landscape in Mäntyviita is fluctuated by low buildings and forest parks in-between them. For example, architect Aulis Blomstedt’s linked houses are separated from Menninkäisentie street, with a zone of pine trees growing freely on a lawn. The small, garden-like yards behind the houses merge into the forest. The carefully thought out, garden-like plantings in Mäntyviita, especially around the shopping centre and the cinema as well as in Neulaspuisto Park, emphasize the contrast between the modern architecture and the forested natural areas. In the extensive Silkkiniitty park area, the surrounding forested terrain elevations were utilized as a shelter for the open park landscape (Jalkanen et al. Citation1997, 20–21; Byman and Ruokonen Citation2009, 67–72).

Tapiola encapsulated the self-image of post-war Finland. The suburb built in forests and pastures was a showcase for modern, international Finland, emphasizing the national dimension of nature. Thus, Tapiola became an attraction for international expert and state visits in the 1960s (von Hertzen and Itkonen Citation1985, 340–350). The landscape opens out from the top floor of Tapiola’s central tower featured the elements on which the image of the developing nation was to be built: out of the forest grows a modern society that recognizes its roots in the realm of the king of the forest (Lahti et al. Citation2017, 115).

Vuosaari – the suburb in the forest

Vuosaari, built in the 1960s in east Helsinki, marked the end of the forest suburb era. The suburb is in many ways comparable to Tapiola. As with Tapiola, the residential area was developed into a cultural landscape, forests and fields (). The main developer in the area was the non-profit-making organization Asuntosäästäjät ry, which aimed to provide affordable homes for ordinary wage earners. The area was marketed to the future inhabitants as a place in harmony with nature, and its idyllic, lush and untouched landscape was emphasized. The new, nature-rich residential area was also presented as a contrast to the cramped living conditions in the city centre and as an attainable possibility for raising one’s standard of living (Weckman et al. Citation2006, 16).

Figure 6. The evolution of Vuosaari, presented in aerial photographs 1950 and 1969. Source: CitationOrtophotographs of Helsinki. City of Helsinki.

Vuosaari also differed in many ways from Tapiola. Unlike Tapiola, which was built in stages, Vuosaari was developed in almost one stage and the residential area for 15,000 inhabitants was completed by the early 1970s. Although the aim was to achieve high quality, the implementation was simpler and more economical than in Tapiola, and the area was later referred to as the ‘poor man's Tapiola’. Tapiola’s ambitious aims with regards to both architecture and landscape architecture became a unique effort never to be implemented again (Mannerla-Magnusson, Donner, and Raassina Citation2016, 138).

Living near nature was the key principle of planning and designing Vuosaari. The town planning architect Olof Stenius produced the detailed local plan for Vuosaari with an aim to achieve a setting resembling Tapiola. Stenius’ plan from 1963 took into account the area’s microclimate, topography and landscape. Buildings were located in the existing forests and rocky terrains, and lowland meadows were preserved as parks and green areas following the same principles as in Tapiola (). Landscape architecture was in a central role, especially the work of landscape architect Katri Luostarinen (Hautamäki and Donner Citation2019, 50, 52; Weckman et al. Citation2006, 25). Luostarinen presented her vision about ideal cities in harmony with nature in her book Puutarha ja maisema (Garden and landscape, 1951). In Vuosaari, she implemented these ideas, according to which large areas of nature were to form a significant part of a city.

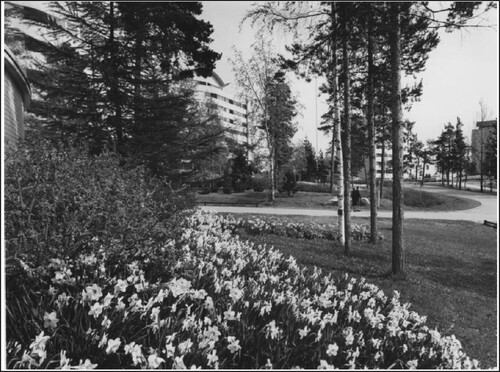

Unlike Tapiola, which fluctuated from open to semi-open and enclosed landscape spaces, Vuosaari was mainly forest, and the city, in a sense, grew from the forest (). Forests were seen as an aesthetic and recreational amenity for the modern suburb. The free-flowing, open and green space was the backbone of the area. No large, built parks in the manner of Tapiola were planned for Vuosaari; instead, the forested central park formed the core element of the residential area, in accordance with Luostarinen’s ideas. The central park was provided with sport and recreation facilities which stressed the amenitized character of nature. The central park is surrounded by residential enclaves formed by large blocks of flats whose expansive yards enabled the preservation of the forest. The yards were seamlessly linked to the surrounding forests and transitioned into natural vegetation or outcrops (Hautamäki and Donner Citation2019, 50, 52; Weckman et al. Citation2006, 34). As in , skiing was possible from the front door of your home.

Figure 7. Vuosaari forest suburb grew from the forest landscape. Photo: Studio B. Möller, 1968, Helsinki City Museum.

Figure 8. Skiing in the home yard in the Vuosaari suburb. Photo: Yrjö Lintunen, 1965, The People’s Archives.

Landscape architecture in Tapiola and Vuosaari shared similar visions; however, they had clear differences in their articulation of nature. Whilst Tapiola highlighted designed nature, landscape architecture in Vuosaari emphasized the naturalization of the environment and the characteristics of Finnish nature. This approach was influenced by the pre-war ideology of anti-urbanism and the polarization of urban and rural and the emphasis on the natural landscapes and characteristics of the homeland (Meurman Citation1947; Dümpelmann Citation2015, 21). Moreover, environmental consciousness, which was on the rise in the 1960s and also resonated in international landscape architecture discussion, influenced the new planning paradigm. The aim was to understand nature’s processes and to take them into account in planning. This kind of an approach is highlighted in Ian McHarg’s seminal book Design with Nature (1969), which states that landscape designers should design in the same way as nature does, and the designed landscape should evoke a natural condition – a state without human intervention (Herrington Citation2018, 496).

The goal to achieve a natural state in design was clearly evident in Luostarinen’s work, both in her writing and plans, as the example of Vuosaari shows. According to her, it was possible to preserve areas in their natural state in urban communities as well, as long as the landscape management was taken into account early enough (Luostarinen Citation1951, 109–111). The majority of the green areas in Vuosaari were different kinds of natural forests, from the rocky hilltops and forested slopes to the central park’s pine forest, and the area featured only very few constructed parks. The large blocks of flats also clustered around their own coniferous or deciduous forested parks, such as Kivisaarentie 12 () and the versatile yard with fluctuating topography at housing company Säästöpurje. The terrain in the yards was worked on as little as possible and thus could evolve almost on its own. The locations for lawns, tiled areas and playgrounds were dependent on the terrain formations.

Figure 9. In Vuosaari, the forest landscape was preserved in its natural state. Preserved pine trees in Kivisaarentie 12. Photo: Eeva Rista, 1970, Helsinki City Museum.

The national dimension was an integral part of modern landscape architecture. In Vuosaari, Luostarinen wanted to introduce elements of traditional Finnish landscape within a new, modern residential area. She aimed to restore native biotopes and reinstate national landscape types. In her yard plans, she sketched, for example, a meadow theme executed with wildflowers as part of the courtyards (Mannerla-Magnusson, Donner, and Raassina Citation2016, 146). Bringing familiar wildflowers, native trees species and forest types into urban living environments reminded new city dwellers of traditional rural landscapes and lifestyle and, thus, generated well-being and helped people feel at home (Luostarinen, Kortteli 65, As Oy Lokkisaari, renewed planting plan 1966; Luostarinen Citation1951, 109).

Vuosaari’s development was linked to a significant structural change and a period of rural emigration in Finland. In 1966, the Parliament of Finland approved the so-called ‘half a million programme’ which corresponded with the million programme launched in Sweden (Miljonprogrammet) (Saarikangas Citation2002, 408; Hall and Vidén Citation2005). The fast urbanization implied progress, but also raised concerns about social problems and the rootlessness of the new urban dwellers. Landscape architecture contributed to finding solutions to these problems. The studied material shows how landscape architecture helped to root urban dwellers that migrated from the countryside to the city. Katri Luostarinen wrote that at its best nature should be available to and in the immediate vicinity of all. Without it, ‘people are like rootless trees’, she remarked (Luostarinen Citation1951, 106). As in Vuosaari, ideal cities should merge with and lean on nature, and the urban structure had to feature the special characteristics of the landscape.

Discussion and conclusions

The Finnish forest suburb combined modern housing and the closeness of nature resulting in the suburban landscape typical of post-war residential planning, ‘the sugar cube in the forest’ (Roivainen Citation1999). Suburban forest landscape and the role of landscape architecture have remained largely unexamined in research. Moreover, the emergence of suburban forests as a new typology of the urban environment and green spaces requires more attention. The aim of our analysis on Tapiola and Vuosaari was to illuminate this typology and its multiple meanings. We demonstrate that forests were not just a ‘natural’ background but culturally constructed, amenitized with facilities and designed by leading urban planners and landscape architects.

With the case studies of Tapiola and Vuosaari, we illustrate how the suburban forest landscape was conceptualized and implemented by designers and planners. A key theme in this construction of nature in both cases is the urbanization of forest – the transformation of existing forest landscapes into suburbs and their green spaces. The urbanization of nature is understood by Swyngedouw and Kaika (Citation2014, 463) as ‘the process through which all types of nature are socially mobilized, economically incorporated (commodified), and physically metabolized/transformed in order to support the urbanization process’. As cases demonstrate, the urbanization of suburban forest landscapes entails multiple narratives in design. We found four key themes: amenitization, aestheticization, naturalization and the national dimension of the forest. We propose that these four themes illustrate how forests were transformed by planners and designers into suburban forests and green spaces for suburban dwellers. These themes also reveal specific characteristics of suburban forest landscapes, elementary to Finnish urbanism.

The urbanization of forests is manifested in the shift from a production-oriented view to multiple-use and a public recreation amenity. With amenitization of the forest, we refer to reshaping suburban landscapes around their amenity functions, primarily visual and recreational values (Cadieux Citation2013, 267). In landscape design, this is evident in the planning of recreational routes and facilities and equipment, such as lighting and benches (e.g. Qviström Citation2016). In both Tapiola and Vuosaari, the recreational value of the forest was essential. The aim was to achieve an aesthetic and safe residential area in which the inhabitants were able to step out from their homes straight into a natural environment and rejuvenate in their free-time. The suburban forest was seen as a restorative but also a moral and educational landscape, an antithesis to the unhealthy urban milieu. The anti-urbanism of suburbs formed an urban model, which became established as a form of Finnish housing with the focus specifically on nature – not urban culture.

Nature was a central part of the visual and aesthetic cityscape of suburbs and their organic spatial planning, designed to adapt to the natural features and terrain. Even though nature was the common starting point for both areas, the design approaches evince clear differences. In Tapiola, the emphasis was on the aestheticized forest and design interventions which aimed to highlight, add and contrast existing nature. With aestheticization of the forest, we refer to the urban conception of nature, free from production or extraction of natural resources (Cadieux and Taylor Citation2013, 10). Aestheticized landscape can also be understood in the context of pastoral, as an idealized image of landscape, emphasizing human design (Cadieux Citation2013, 271). In landscape architecture, the concept of the aestheticized forest has a specific focus on design interventions, contrasting natural features of nature.

While Tapiola represented the aestheticized forest, in Vuosaari, the focus was on the naturalized forest, aiming to preserve the natural state and existing vegetation. The naturalization of suburban forest stresses nature without human intervention and understands forests as ‘natural’, appearing to be the way they should be, as Raymond Williams has pointed out in his etymology of ‘nature’ (Cadieux and Taylor Citation2013, 4, 19; Williams Citation1976, 184). Similarly, Qviström (Citation2016, 207) has described how Swedish leisure planning regarded urban forests as untouched nature despite the major investment of recreational infrastructure. As the example of Vuosaari demonstrates, the naturalized forest was also manifested in constructing natural biotopes and using native vegetation, in naturalizing the city and designing with nature, according to seminal McHarg’s principles.

The national dimension of the forest refers to the role of landscapes in nation-building (Häyrynen Citation2005) and landscape architectural references to Finnish nature. According to Moscovici (Citation1984), a forest landscape can be seen in a wooded country such as Finland as an example of social representation referring to the concept of a nation. As the case studies illustrate, forests were regarded as a specifically Finnish landscape, which rooted rural migrants to their new homes. Finnishness of the forest was also manifested in the use of native biotopes and tree species, as Vuosaari demonstrates. Finnishness was consciously constructed, and especially in Tapiola, modern architecture in the forest became the national and international icons of urban planning. This narrative was strengthened by naming the area after Tapio, the king of the forest in the Finnish national epic, Kalevala.

The aim of the article is to highlight the often invisible suburban landscapes and their forests as an integral part of the Finnish suburban development. Forest suburbs manifest a Finnish way of life close to nature. They also illustrate the dichotomy between nature and the city, inherent in suburbs. Due to this dichotomy, they are simultaneously both loved and hated – loved for their immediacy to nature or hated for their lack of urban character. The 1960s’ compact city ideology took a strong stance against sparsely built suburbs. Roivainen (Citation1999) illustrated in their doctoral thesis how newspaper articles on suburbs turned in the late 1960s more problem-centred, placing emphasis on the external image of suburbs. Only in the 1990s, the narrative deepened and depicted suburbs from the inside – as a home for suburban dwellers. From the beginning of the 2000s, however, the strengthened densification and the new compact city thinking have generated more critical voices against suburbs among urban planners. The suburb has turned into an antithesis to urban and even a slur. Spaciousness and nature have been regarded as attributes not belonging to the city (Hautamäki Citation2019, 27). Nymoen Rørtveit and Setten (Citation2015, 956) recognize the same negative attitude in their research on Norwegian housing estates: experts, especially urban planners and architects, regard estates as inherently bad places to live and in danger of becoming ghettoized due to the large numbers of low-income, poorly educated residents, including ethnic minorities. However, the negative views are not shared by residents. As Saarikangas’ research on life in the suburb shows, people enjoy living in the suburbs and advocate particularly strongly their proximity to nature (Saarikangas Citation2002, 490–494; Saarikangas Citation2011, 12–37). Therefore, there is a major gap between the experts’, especially planners' ideas about the suburbs as less-attractive landscapes and residents’ narratives (see also Brattbakk and Hansen Citation2004).

An important starting point for this article is to respond to this prevailing critique against forest suburbs and to highlight their characteristics and their value as heritage. The forest suburb is traditionally interpreted within the framework of anti-urbanism, but it should be understood as a special Finnish form of urbanism. Mäenpää (Citation2008, 26) has characterized this attitude as open-minded urbanism (avara urbanismi), which lets go of the eternal pursuit of missing urban qualities. Modern living in the forest is an established part of Finnish urban culture. In Alvar Aalto’s words: ‘There should not be a commute from home to work that does not take you through a forest’ (Schildt and Mattila Citation1990, 272).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersson, T. 2000. Utanför staden. Parker i Stockholms förorter. Stockholms tekniska historia. Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag.

- Asikainen, E., and A. Jokinen. 2009. “Future Natures in the Making: Implementing Biodiversity in Suburban Land-Use Planning.” Planning Theory & Practice 10 (3): 351–368.

- Berninger, K., D. Kneeshaw, and C. Messier. 2009. “The Role of Cultural Models in Local Perceptions of SFM – Differences and Similarities of Interest Groups from Three Boreal Regions.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (2): 740–751.

- Braae, E., and H. Steiner. 2019. Routledge Research Companion to Landscape Architecture. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Brattbakk, I., and T. Hansen. 2004. “Post-war Large Housing Estates in Norway? Well-kept Residential Areas Still Stigmatised?” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 19 (3): 311–332.

- Braun, B., and N. Castree. 1998. Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millenium. London: Routledge.

- Brown, M., and M. Luccarelli. 2012. “Oslo's Ullevål Garden City: An Experiment in Urbanism and Landscape Design.” In Green Oslo: Visions, Planning and Discourse, edited by M. Luccarelli and P. G. Røe, 81–115. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Bunce, S., and G. Desfor. 2007. “Introduction to “Political Ecologies of Urban Waterfront Transformations”.” Cities 24 (4): 251–258.

- Byman, E., and R. Ruokonen. 2009. Tapiolan kasvillisuuden hoito- ja uusimissuunnitelma. Espoo: Espoo kaupunki.

- Cadieux, K. 2013. “The Mortality of Trees in Exurbia’s Pastoral Modernity. Challenging Conservation Practices to Move Beyond Deferring Dialogue About the Meanings and Values of Environments.” In Landscape and the Ideology of Nature in Exurbia Green Sprawl, edited by K. Cadieux, and L. Taylor, 252–294. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cadieux, K., and L. Taylor. 2013. “Introduction.” In Landscape and the Ideology of Nature in Exurbia Green Sprawl, edited by K. Cadieux, and L. Taylor, 1–30. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Corner, J. 1992. “Representation and Landscape: Drawing and Making in the Landscape Medium.” Word and Image 8 (3): 243–275.

- Dümpelmann, S. 2015. “Creating New Landscapes for Old Europe: Herta Hammerbachher, Sylvia Crowe, Maria Teresia Parpagliolo.” In Women, Modernity, and Landscape Architecture, edited by S. Dümpelmann and J. Beardsley, 15–37. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fischer, F. 2003. Reframing Public Policy Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gieryn, T. 2000. “A Space for Place in Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 463–496.

- Haapala, P. 2007. “Kun kaikki alkoi liikkua … .” In Suomalaisen arjen historia. Modernin Suomen synty, edited by K. Häggman and P. Haapala, 47–63. Helsinki: Weilin & Göös.

- Hall, T. 2005. “Post-war New-town ‘Models’: A European Comparison.” Urban Morphology 9 (2): 109–121.

- Hall, T., and S. Vidén. 2005. “The Million Homes Programme: A Review of the Great Swedish Planning Project.” Planning Perspectives 20 (3): 301–328.

- Hankonen, J. 1994. Lähiöt ja tehokkuuden yhteiskunta: suunnittelujärjestelmän läpimurto suomalaisten asuntoalueiden rakentumisessa 1960-luvulla. Espoo: Otatieto.

- Harvey, D. 1996. Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Hautamäki, R. 2019. “Contested and Constructed Greenery in the Compact City: A Case Study of Helsinki City Plan 2016.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 14 (1): 20–29.

- Hautamäki, R., and J. Donner. 2019. “Representations of Nature - the Shift from Forest Town to Compact City in Finland.” Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskrift 2019 (76): 44–62.

- Häyrynen, M. 2005. Kuvitettu maa: Suomen kansallisten maisemakuvastojen rakentuminen. Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

- Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus. 1966. Kertomus Helsingin kaupungin kunnallishallinnosta. 2. Kiinteistövirasto. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupungin Tilastokeskus.

- Helsingin kaupungin tilastokeskus. 1968. Kertomus Helsingin kaupungin kunnallishallinnosta. 2. Kiinteistövirasto. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupungin Tilastokeskus.

- Herrington, S. 2018. “Landscape Design.” In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, edited by P. Howard, I. Thompson, E. Waterton, and M. Atha, 487–498. London: Routledge.

- Hirvensalo, V. 2006. Modernin kaupungin luonto muutoksessa - kahdeksan esimerkkiä suomalaisesta asuinaluesuunnittelusta. Turku: Turun yliopisto.

- Hurme, R. 1991. Suomalainen lähiö Tapiolasta Pihlajamäkeen. Helsinki: Suomen tiedeseura.

- Itkonen, E. 1959. “Etymologisia lisiä.” In Verba docent: juhlakirja Lauri Hakulisen, 60-vuotispäiväksi 6.10.1959, edited by T. Itkonen, P. Pulkkinen, and P. Virtaranta, 135–143. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Jalkanen, R., T. Kajaste, T. Kauppinen, and P. Pakkala. 1997. Asuinaluesuunnittelu. Rakennustieto: Helsinki.

- Jännes, J. 1964. “Tapiolan maisemahuollosta ja puutarhasuunnittelusta. Pyrkimyksiä ja kokemuksia.” Asuntopolitiikka 4/1964: 4–7.

- Jessen, A., and A. Tietjen. 2017. “Reconfiguring Welfare Landscapes: A Spatial Typology. City and Territory in the Globalization Age Conference Proceedings.” ISUF International Conference, 1673–1683.

- Kaika, M. 2004. City of Flows: Modernity. Nature, and the City. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Konijnendijk, C. C. 2018. The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland 2nd ed. Cham: Springer.

- Kotilainen, J., and T. Rytteri. 2011. “Transformation of Forest Policy Regimes in Finland Since the 19th Century.” Journal of Historical Geography 37 (4): 429–439.

- Lahti, J., H. Kalha, J. M. Woodham, T. Karjalainen, A. Niskanen, B. Colomina, E. Heikka, et al. 2017. Modernia elämää! Suomalainen modernismi ja kansainvälisyys. Helsinki: Parvs.

- Laszlo Ambjörnsson, E., E. C. H. Keskitalo, and S. Karlsson. 2016. “Forest Discourses and the Role of Planning-Related Perspectives: the Case of Sweden.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 31 (1): 111–118.

- Latour, B. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. New York, NY: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Lehto, L. 1990. Elämää helsinkiläismetsissä. Livet i helsingforsskogar: Helsingin kaupunginmetsänhoidon syntyhistoriaa. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupunginmuseo.

- Lisberg Jensen E. 2002. Som man ropar i skogen: Modernitet, makt och mångfald i kampen om Njakafjäll och i den svenska skogsbruksdebatten 1970–2000. Lund: Lund University.

- Louekari, L. 2006. Metsän arkkitehtuuri. Oulu: Oulun yliopisto.

- Luostarinen, K. 1951. Puutarha ja maisema. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Mäenpää, P. 2008. “Avara urbanismi. Yritys ymmärtää kaupunki toisin.” In Asuttaisiinko toisin? Kaupunkiasumisen uusia konsepteja kartoittamassa, edited by H. Lehtonen and M. Norvasuo, 21–49. Espoo: Teknillinen korkeakoulu.

- Makkonen, L. 2011. “Metsäkaupunki eilen, tänään ja huomenna.” In Asiasta toiseen. Kirjoituksia restauroinnista ja rakennussuojelusta, edited by L. Putkonen, 66–69. Helsinki: Museovirasto, Rakennustieto Oy.

- Mannerla-Magnusson, M., J. Donner, and M. Raassina. 2016. “Tapiola ja sen jälkeinen aika. Metsäpuistoja, nurmiluiskia ja kävelykansia.” In Unelma paremmasta maailmasta. Moderni puutarha ja maisema Suomessa, 1900–1970, edited by J. Sinkkilä, J. Donner, and M. Mannerla-Magnusson, 138–156. Helsinki: Aalto Arts Books.

- Marx, L. 1964. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Meurman, O. 1947. Asemakaavaoppi. Helsinki: Otava.

- Mikkola, K. 1972. Metsäkaupungin synty: funktionalismin ja kaupunkisuunnittelun aatehistoria. Espoo: Teknillinen korkeakoulu.

- Mills, A. J., G. Durepos, and E. Wiebe. 2010. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Moscovici, S. 1984. “The Phenomenon of Social Representations.” In Social Representations, edited by R. M. Farr and S. Moscovici, 3–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nikula, R. 1994. Sankaruus ja arki. Suomen 50-luvun miljöö. Heroism and Everyday. Building Finland in the 50´s. Helsinki: Suomen Rakennustaiteen museo.

- Nilsson, L. 2006. “The Stockholm Style: A Model for the Building of the City in Parks, 1930s–1960s.” In The European City and Green Space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St. Petersburg, 1850-2000, edited by P. Clark, 141–158. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Nymoen Rørtveit, H., and G. Setten. 2015. “Modernity, Heritage and Landscape: The Housing Estate as Heritage.” Landscape Research 40 (8): 955–970.

- Pallasmaa, J. 1987. “Metsän arkkitehtuuri.” Silva Fennica 21 (4): 445–452.

- Peil, T. 2014. “The Spaces of Nature: Introduction.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 96 (1): 37–39.

- Petrina, S. 2020. Methods of Analysis Historical Case Study. Accessed 22 June 2021. https://www.academia.edu/44505802/Historical_Case_Study.

- Qviström, M. 2016. “The Nature of Running: On Embedded Landscape Ideals in Leisure Planning.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 17: 202–210.

- Rackham, O. 2004. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. The Complete History of Britain’s Trees, Woods & Hedgerows. New York, NY: Phoenix Press.

- Roivainen, I. 1999. Sokeripala metsän keskellä: Lähiö sanomalehden konstruktiona. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupunki.

- Ruokonen, R. 2003. “Kädenjälkiä maisemassa - Tapiolan viheralueet.” In Tapiola. Elämää ja arkkitehtuuria, edited by T. Tuomi, 90–111. Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy.

- Saarikangas, K. 2002. Asunnon muodonmuutoksia: Puhtauden estetiikka ja sukupuoli modernissa arkkitehtuurissa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Saarikangas, K. 2008. “Rakennetun ympäristön muutos ja asumisen mullistus.” In Suomalaisen arjen historia. Hyvinvoinnin Suomi, edited by K. Häggman, M. Kuisma, P. Markkola, P. Pulma, R.-L. Kuosmanen, and R. Forslund, 142–163. Helsinki: Weilin + Göös.

- Saarikangas, K. 2011. “Takapihalta alkoi metsä”. Muistin paikat kerrotussa ja eletyssä lähiötilassa.” In Näköalapaikka: Kertomuksia Pihlajamäestä, edited by K. Markkanen and L. Tirri, 12–37. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupunginmuseo.

- Schildt, G., and R. Mattila. 1990. Inhimillinen tekijä: Alvar Aalto 1939-1976. Helsinki: Otava.

- Smulyan, S. 1994. “Discovering Science and Technology Through American History.” Technology and Culture 35 (4): 846–856.

- Spirn, A. W. 2007. ““One with Nature”: Landscape, Language, Empathy, and Imagination.” In Landscape Theory, edited by R. Delue and J. Elkins, 43–67. Florence: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2004. Social Power and the Urbanization of Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Swyngedouw, E., and M. Kaika. 2014. “Urban Political Ecology. Great Promises, Deadlock … and New Beginnings?” Documents D’anàlisi Geogràfica 60 (3): 459–481.

- Takala, T., A. Lehtinen, M. Tanskanen, T. Hujala, and J. Tikkanen. 2019. “The Rise of Multi-objective Forestry Paradigm in the Finnish Print Media.” Forest Policy and Economics 106: 1–12.

- Topelius, Z. 1876. “Boken om Vårt Land.”

- Tuomi, T. 1992. Tapiola. Puutarhakaupungin vaiheita. Arkkitehtuuriopas. Espoo: Espoon kaupunginmuseo.

- Tuomi, T. 2003. Tapiola. Elämää ja arkkitehtuuria. Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy.

- von Hertzen, H. 1946. Koti vaiko kasarmi lapsillemme: Asunnontarvitsijoiden näkökohtia asunto- ja asemakaavakysymyksissä. Porvoo: WSOY.

- von Hertzen, H., and U. Itkonen. 1985. Raportti kaupungin rakentamisesta. Tapiolan arkea ja juhlaa. Espoo: Länsiväylä.

- Weckman, E., K. Susi-Wolff, T. Rönkä, H. Timonen, and L. Makkonen. 2006. Keski-Vuosaari. Maisema- ja kaupunkikuvallinen selvitys. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupunki.

- Williams, R. 1976. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London: Fontana.

- Wylie, J. 2007. Landscape. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Internet sources

- https://wiki.aineetonkulttuuriperinto.fi/wiki/Suomalainen_metsäsuhde (15.10.2020)

- https://metsasuhteita.fi/elava-perinto/ (28.11.2020)

- Ortophotographs of Helsinki. City of Helsinki, Urban Environment Division/City survey service. https://hri.fi/data/fi/dataset/helsingin-ortoilmakuvat. CC BY 4.0. (25.7.2021)

- Unprinted sources

- Museum of Finnish Architecture: the plans by Jussi Jännes and Katri Luostarinen.