Abstract

This article is published as part of the Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography special issue based on the Vega symposium: ‘Bounded spaces in question: X-raying the persistence of regions and territories, edited by Anssi Paasi.

ABSTRACT

Regions and territories become institutionalized as part of wider geohistorical processes and practices in which these spatial entities accomplish their borders, institutions, symbolisms and normally contested identity narratives. The borders of bounded spaces are ever more topical today because of the mobilities of human beings (tourists, migrants, refugees), the rise of (ethno-)nationalism and regionalism, anti-immigration discourses and racism; features that expose the ideological significance of territories and the forms of physical and symbolic violence that are frequently embedded in borders/bordering. This essay explores the tenacity of bounded spaces in academic research and in social practices, and the meanings attached to such spaces. It will analyze how geographers and other social scientists have understood and conceptualized regional and territorial spaces and traces the evolution of the keywords in border studies. Borders are material and ideological constructs, institutions, processes and symbols that are critical in the production and reproduction of regions/territories, identities and ideologies. The article leans on author’s idea of spatial socialization and Shields’ notion of social spatialization in making sense of how the obstinate power of borders is embedded in the production and reproduction of bounded spaces and in the process of subjectification.

Introduction

Region, territory and border are major keywords in academic geography but critical also in socio-spatial practices such as governance and planning. Region has been constantly a highly motivating term for geographers, but the debates on the meanings and the future of the region have extended beyond geography since the 1980s–1990s. New ideas on regions have been impregnated with socio-spatial theory and characterized by the upsurge of such notions as geohistory, relationality, performativity, or topology, for example (Murphy Citation1991; Allen, Massey, and Cochrane Citation1998; Macleod and Jones Citation2001; Paasi and Metzger Citation2017; Jones Citation2018; Paasi, Harrison, and Jones Citation2018). Likewise, territory, the major watchword of political geography has revived in both geographic and interdisciplinary debates (Brighenti Citation2010; Elden Citation2010; Murphy Citation2013; Moore Citation2015; Storey Citation2020). Rather than static entities, regions and territories are often conceptualized as dynamic socio-spatial, geohistorical processes. Thus, instead of merely ‘being’ passive backgrounds, they constantly ‘become’, are institutionalized, and modified through territorial, symbolic and institutional shaping in the matrix of wider power relations, geohistorical practices and discourses. In these practices and discourses such bounded spaces accomplish their shifting borders, formal and informal institutions, imaginings, and symbolisms, and often contested identity narratives. Consequently, space and time are inseparable in the making of regions and bordering. Regions and territories may ultimately become deinstitutionalized through mergers or disintegration (Paasi Citation1991).

Border, another watchword of political geography (but also critical in regional geography) has become topical in two contexts. First, in multidisciplinary research focusing on the meanings and future of (state) borders in the globalizing world characterized by the border-crossing movement of capital, goods and people (Johnson et al. Citation2011). Correspondingly, as in the production and reproduction of regions and territories, also in the case of borders and the practices of bordering, spatialities and temporalities become fused in complex ways (Axelsson Citation2022; Allen and Axelsson Citation2019). Second, borders have become significant in the debate on sub-state and cross-border planning spaces and their territorial and/or relational qualities (Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2009; Walsh Citation2015; Paasi and Zimmerbauer Citation2016; Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020).

Borders are mobilized by individual and institutional actors (politicians, civil servants and legislators, organizations, law, heritage, tourism industry, media, etc.), often in contradictory ways, to organize, govern, regulate, and plan social spaces and social life, and to manage welfare, identities, and meanings at and across various scales, as well as to slow down and speed up mobilities. This occurs through boundary producing/reproducing practices that can be both material and ideological, conceptual and cartographic, imaginary and actual, and social and aesthetic (Ó Tuathail and Dalby Citation1998).

The processes of globalization have impacted the spatialities of power, unlocked many territorial spaces, questioned the justification of many hard borders, and forced scholars to rethink their key categories (and their relations) connected to clear-cut topographies, among them borders and bordering (Amin Citation2004; Urry Citation2003; Allen Citation2016; Jessop Citation2018). While globalization is frequently associated with the opening of borders, de-bordering and/or border-crossings, the key forces behind globalization, such as rationalist knowledge, capitalist production, automated technologies, cyberspace, or bureaucratic governance (Scholte Citation2005) both de-border (by means of capitalist accumulation, neo-liberalization and internationalization as the key rationalities) and re-border (by means of nationalist ideologies, border governance and expanding control technologies). Massey and Clark (Citation2008, 3) aptly wrote:

One of the ways in which a ‘globalized world’ is frequently characterized is in terms of a planet in which all borders and boundaries have dissolved and in which flows of people, money, cultural influence, communications and so on flow freely. It is this feature of globalisation that can give rise to feelings of being bombarded from all directions … Yet, even as this image of a globalized world becomes ever more powerful, it is clear that the world does still have its borders and distances, that it is still in many ways divided up into territories; indeed, that new enclosures are being erected in the very midst of the production of powerful new flows. Nation states still exist; there are fierce debates over international migration; the rich may try to seal themselves off against the poverty outside; and aboriginal peoples may fight to protect their lands from invasion by multinational corporations. It may even be that the very process of opening up which is implied in so many stories (and realities) of globalization itself encourages a need to build protective boundaries, to define areas of privacy – territories which can be controlled in some way or other.

We live enmeshed in thick webs of borders and boundaries. Most are out of sight and conscious awareness, yet they all impinge in some way on our lives as integral parts of our real and imagined geographies and biographies. Some carry with them the hard and invasive powers of the state, others the manipulative magic of market forces, still others the softer limits of identity and community, desire and imagination. Borders and boundaries are life’s linear regulators, framing our thoughts and practices into territories of action that range in scale and scope from the intimate personal spaces surrounding our bodies through numerous regional worlds that enclose us in nested stages extending from the local to the global. (Soja Citation2005, 33)

I will start by examining the resurgence of the region and territory, its motives, and the politicization of such spaces. I will then evaluate the shifting roles of regional and state borders, the violence embedded in state borders, current contested tendencies in de- and re-bordering, and will then consider why borders are so persistent. I will conclude this essay by considering what ‘progress’ could be in the geographic research focusing on bounded spaces and borders.

The resurgence of bounded/non-bounded spaces

The many-faced region

Geographers have theorized regions since the founding of this field in the academia. Conceptual developments have varied between different linguistic and national contexts, though knowledge constantly tends to move across borders from one context to another (cf. Agnew and Livingstone Citation2011), typically from hegemonic centres to peripheries. Montgomery (Citation2003, 1, cited in Cronin Citation2005) once proclaimed that ‘There are no boundaries, no walls, between the doing of science and the communication of it; communicating is the doing of science’. Despite the noble ideal of a ‘borderless academy’ and freely travelling knowledge, academic communication, publishing and exchange of ideas reflect power relations and contextuality (Paasi Citation2015). Knowledge is relentlessly negotiated and transforms when it travels (Agnew and Livingstone Citation2011). Conceptual change and development do not rise in vacuo: science studies have shown that the transformation of academic concepts echo both individual and institutional motives, societal power relations, interests of knowledge, philosophical and methodological approaches, and wider (geo)political developments (Paasi Citation2011).

French and German geographers were originally significant sources of inspiration for regional thinking, and, as Jones (Citation2022) shows in his article, many British and US geographers followed them. Region was at the core of methodological debates in regional geography until the post-World War II period. Scholars debated intensively whether the region should be understood as a ‘mental category’ or as a ‘really existing entity’ (Hartshorne Citation1939; Minshull Citation1967). Region maintained its position in the emerging positivist geography, although in a functional, more abstract sense (Haggett Citation1965). Key conceptual ideas hovered now from the Anglophone world elsewhere (Entrikin Citation2010; Paasi, Harrison, and Jones Citation2018). After the early pleas (Gregory Citation1978; Massey Citation1978; Thrift Citation1983; Pred Citation1984; Paasi Citation1986) social theory began to nourish the evolving regional concepts. The key for understanding and conceptualizing the region was now social practice. From this standpoint regions are not merely resulting from academic musings, but the ‘existence’ of regions is related to social practices and discourse. As Anderson (Citation2000, 35–36) writes,

Regions come in all shapes and sizes, some clearly demarcated by a long history, others little more than figments of a central bureaucrat’s imagination. Regionalisms likewise range from an almost non-existent sense of regional identity to fully-fledged sub-state nationalisms, a form of identity politics which sees the ‘region’ as a potentially separate independent country. The terms region and regionalism thus mask a range of quite different phenomena which vary not only from state to state but also within particular states.

New views on region emerged also in so-called ‘new regionalism’ (cf. Jones Citation2022) that resonated with economic geography. The key issue was now ‘regional competitiveness’ (Storper Citation1997; Scott Citation1998). A new regionalism emerged also in political science and international relations studies (Söderbaum Citation2003). This focused on the sub-state or cross-border ethno-regionalisms of independence movements, and on economy and security-related supra-state alliances of states. New regionalism partly replaced older culture and identity -based regionalisms but its attention to regional identities has also retained such themes on agenda (LeGales and Lequesne Citation1998; Keating Citation1998; Katzenstein Citation2005; Kohlenberg and Godehardt Citation2020).

Geographic research has leaned on three interpretations of regional spaces which force us to reflect the roles of borders. The first is pre-scientific where regions are taken for granted as practical choices, without any precise conceptual role. Fitting examples are statistical regions or bounded administrative units with fixed borders that are used mainly in applied research and governance. In European Union statistical NUTS-regions have provided such a given matrix for studies. Second, discipline-centric views on regions are typically outcomes of research processes and result from the formal or functional classification of phenomena or perceptions that are mapped and represented as a set of bounded spaces in regional divisions. This type of region was in the focus of the critique when Doreen Massey (Citation1993) outlined relational thinking on regions. She had suggested earlier (Massey Citation1978) that geographers should start from capital accumulation processes rather than given regions. Hence, she rejected the taken-for-granted ideas bounded regions and many others followed (Massey Citation1993; Allen, Massey, and Cochrane Citation1998). The border she had her in mind was obviously an abstract line of separation, typically created by geographers when making regional divisions. For Massey such lines would not be relevant in the world of human interactions and encounters (cf. Amin Citation2004).

Indeed, many geographers since Hartshorne had challenged the role of regional borders. Kimble (Citation1951) even stated that regional geographers try to put boundaries that do not exist around areas that do not matter! Nonetheless, in social practice regional borders, similarly as state borders, are also social processes, institutions and symbols that can be spread and embedded in plentiful practices, discourses and power relations in a region, and they may also stretch beyond the region; it is therefore difficult to remove them with an ‘academic fiat’. As political spaces regions are both bounded and porous (Jones Citation2022). Thus, thirdly, we need critical views on regions that recognize and theorize them as social and geohistorical processes. Regions and their borders are contested political, economic and cultural constructs, perhaps even sort of social contracts, that are performed in various social practices and discourses, particularly in governance and politics/policies.

A parallel critique emerged in relational regional/strategic planning where new concepts such as soft spaces and fuzzy borders were launched and that have spread widely, as an illustration of the transnational diffusion of policy practices (policy transfer). In this context Paasi and Zimmerbauer (Citation2016) outlined the concept of ‘penumbral border’, which acknowledges the multidimensionality and temporality of borders; they can be open in certain practices at certain times and closed in some others. Regions theorized in planning are usually sub-state or cross-border units (Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2009; Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020). Cross-border regions are relevant also in economic geography and regional science, where regional spaces are often seen as given backgrounds for economic processes (Bristow Citation2010; Christopherson and Clark Citation2007). Nijkamp (Citation2021) argues that regional science has regularly ignored borders by disregarding that they are much more than economic barriers in human interaction spaces; rather they are multidimensional ‘organizing principles’ for mobility, interaction, location and socio-cultural identities of regions. He proposes the concept ‘enabling space’ in which borders are understood as opportunities for innovative development in a cross-border space-economy.

Geographers are now stepping beyond the divide between territorial and relational regions, towards more flexible ideas such as plastic region, as Jones (Citation2022) shows in his Vega Symposium contribution. One of the ‘mediating’ backgrounds in such efforts has been topology which has motivated scholars reflecting the current roles of regions, territories and borders (Shields Citation2013; Allen Citation2016; Jones Citation2022; Murphy Citation2022; Axelsson Citation2022).

The polymorphous territory

Territory, the traditional keyword of political geography (Soja Citation1971; Gottmann Citation1973; Sack Citation1986), has also revitalized in recent research focusing on the genealogy of the term, on territory’s shifting roles for the state sovereignty, on transforming human-nature relations (e.g. climate change) and globalization, or even in proposals for a general theory of territories (Delaney Citation2005; Brighenti Citation2010; Painter Citation2010; Murphy Citation2013; Elden Citation2010; Agnew Citation2017; Moore Citation2015; Stilz Citation2019; Ochoa Espejo Citation2020; Storey Citation2020; Dalby Citation2020). Territory is typically defined as a spatial unit occupied by individual actors, social collectives or institutions, primarily national states, which has highlighted the role of borders in their making. Yet, territory is, in the same way as the region, a word denoting many, even contradictory concepts, and scales, and, similarly, its territorial and relational qualities can be highlighted (Paasi Citation2003; Jessop Citation2018). Due to its polymorphous nature and definitions territory has been recognized as an ‘over-extended concept’ (Painter Citation2010). To avoid such overstretching, it is critical to be sensitive to both the context and intentions behind the usage of the term.

The political significance and contested nature of territories evolve exactly from their polymorphous nature since numerous dimensions of social life and social power come together in them. Territory comprises material elements such as land, functional elements such as the control of space and its borders, as well as the diverse, often powerful, sacred and symbolic dimensions (Paasi Citation2009). Hence it brings together identity, authority, and organizational and economic efficacy required in the governance of social mechanisms, ideologies and memories that make territorial spaces meaningful. Thus, both social spatialization and spatial socialization come into play, the former in the making of spatial structures, the latter in meaning-making and in the mobilization of media and national(ist) moral education in history and geography, for example (Paasi Citation2020). For political geographers, territorial borders have been significant but often partly given devices not only in the making of territories and in territorializing subjectivities but also in practicing territoriality as a specific strategy of power (Sack Citation1986). Their meanings are rarely discussed in-depth, rather borders are frequently seen as necessary (often linear), relatively firm elements in the making of regulated-bounded spaces (Sack Citation1986; cf. Painter Citation2010). Anderson and ÓDowd (Citation1999, 594) argue that territorial borders both shape and are shaped by what they comprise, and what cross, or is prohibited from crossing them. Sibley (Citation1995), for his part, contends that spatial borders are in part moral boundaries and spatial separation symbolizes moral order. Ethical and moral issues related to territory and borders emerge immediately when we consider ‘who should be where?’. Respectively, particularly state territories and their borders are often ideologically coloured pools of emotions, fears and memories that have accumulated historically and that can be mobilized for both progressive and regressive purposes (cf. Murphy Citation2022)

The term territory has currently also wider meanings that reverberate with moral orders and different scales that vary from human bodies to broader spatial constellations in politics, governance, spatial planning, or Europeanization, for example. Borders have a role to play in all of these, but this role varies. Cunningham (Citation2020, 135) claims that sovereign borders are designed to manage human bodies in space and time and respectively borders are constantly experienced in somatic and embodied terms. While narratives of spatial identities are also significant in making territories meaningful, it is critical to avoid psychologizing views on borders as reflecting some sort of ‘basic human need to live in a bounded space’ (Leimgruber Citation1991, 41).

The politicization of bounded spaces

Current focus on regional and territorial spaces and borders has not arisen from academic motives only. New interest resonates with socio-spatial processes and practices that echo neo-liberal (economic) globalization, uneven development, and geopolitical and geo-economic rivalries. For example: immigration; efforts towards regional integration and networking; strengthening ethno-regionalism/nationalism; fragmentation of social and regional identities and interests; the rise of autonomy and independence movements; shifting forms governance; the rescaling and devolution of territorial spaces; (city-)regionalism; the upsurge of cross-border regions/cooperation; the mergers of territorial spaces; supra-state regionalization; the invention of new, ‘soft’ planning spaces; regional resilience and sustainability, or regional branding and marketing. All such propensities have stimulated research on regions, territories and borders. Some tendencies have led to the consolidation of bounded spaces, some to their disintegration, some others have challenged the existing (state) borders, and still some others have witnessed the replacement of old borders with new ones. A fitting (European) example are ‘non-standard’ or ‘unusual regions’ (Deas and Lord Citation2006) that overlap with dominant regional-territorial (state-centric) worlds. Such new regions are typically cross-border units or other policy spaces designed for reorganizing socio-spatial processes and governance or simply to lower the borders between states and/or old, established regions.

The previous list of partly contradictory impulses implies that regional and territorial spaces are often disputed, a point echoing often their ‘boundedness’. The construction of socio-spatial entities, categorizations and meanings display various forms of politics embedded in both social spatialization and spatial socialization. Political philosopher Kari Palonen (Citation2003) distinguishes four modalities of the ‘political’: polity, policy, politicization and politicking. Polity is a metaphorical space with possibilities and limits; policy signifies the regulatory aspects of politics; politicization marks opening something as political; and politicking is making politics by putting a performative, persuading facet at the centre. These dimensions come regularly together in region/territory building and bordering that result from complex agencies and contested power relations. Thus, bounded spaces and their borders may be objects of policies mobilized to accomplish contested political goals in these contexts and in the wider world. They can also be objects of politicking, often fetishized as subjects capable of doing things as self-sufficient actors. Such fetishizing is usual in Othering occurring in media, nationalist politics, or regional policies and marketing, for example (Paasi Citation2021). Bounded spaces and their borders may also be articulated as actors engendering security or identity for a community. Such fetishization has been questioned. Ochoa Espejo (Citation2020), for example, criticizes views on territories as discrete pieces (of property) possessed by identity groups. She conceptualizes them in more dynamic terms as flowing, moving, leaking and melting, as interconnected arrangements where people, institutions, the biota and the land together form overlapping civic responsibilities and relations (cf. Paasi et al. Citation2022). Likewise, Joe Painter (Citation2010) argues that territory should be seen primarily as an effect, a product of relational networks; territory-effect thus results from networked socio-technical practices.

The fact that regional and territorial spaces are disputed and politicized is therefore often related to bordering (Paasi Citation2016; Paasi and Zimmerbauer Citation2016). Bounded spaces imply a political struggle over the definitions and meanings – real or imagined – of the anticipated spatial entity under construction (Keating Citation2017). This is evident particularly when regions or territories as devices for state policy are in tension with those expressing territorial autonomy or regionalist passions. Respectively, ‘regions are arenas for playing out some of the most important political issues such as the balance between economic competition and social solidarity’ (Keating Citation2017, 16). Reasons for politicization may also mirror the changing geohistorical position of territorial spaces. Murphy (Citation2022) suggests that hyper-globalization has played a major role in the rising power of a right-wing variant of populism rooted in the obstinate glorification of state sovereignty. This may appear in regional contexts, where populists are claiming back the ‘lost’ sovereignty, stronger borders, or anti-immigration policies. A useful illustration is Rodriquez-Pose’s (Citation2020) work on ‘places that do not matter’. He found, for example, that the rise of the vote for anti-system parties relates to the long-term economic decline of regional spaces that have earlier experienced better times and have then been disadvantaged by processes that have rendered them unprotected. This observation doubtless also holds also with territorial identity, since belonging to a group inhabiting a bounded space is not only embedded in shared political and socio-cultural values but also in the socio-economic advantages reflecting the assembly of mutual competencies and local relationships. Rodriquez-Pose notes that ‘fixing’ such places is critical in challenging anti-system politics and this will require well-targeted spatially sensitive policies.

Shifting border studies

If the literature on regions and territories and their borders has multiplied since the 1990s, an even more massive amount of research on state borders has appeared. Respectively, all efforts to trace the long-term evolution of border studies are inevitably selective and display investigator’s subject positions in specific spatiotemporal and linguistic contexts (cf. Kolossov and Scott Citation2013). Such efforts also express researchers’ understanding of what ‘progress’ in research means. Various academic generations may also have different methodological views on what is progress and what is regress.

While borders have been important since the birth of political geography (Ratzel Citation1898) and significant in the gradual consolidation of ‘sovereign’ national states, nationalism and international law, traditional border studies have been at times regarded as the most torpid area of political geography, which refers to their long non-theoretical and predominantly empirical tradition (Agnew Citation1995). Theoretical interest in borders has evolved since the 1990s when political geographers and scholars in Critical Geopolitics and International Relations put forward new perspectives and interdisciplinary research agendas (Newman and Paasi Citation1998; Ó Tuathail and Dalby Citation1998; Parker and Vaughan-Williams Citation2009). Also, cultural and ethnic borders and dividing lines, studied earlier primarily by anthropologists, have gained new ground in geography (Megoran Citation2006). Atrocious wars in eastern Europe in the 1990s, often related to ethnic conflicts, wars of independence and insurgencies gave also rise to both new borders and new research. Paradoxically, at the same time too eager business gurus inspired by the processes of globalization declared prematurely the birth of the new brave borderless world (Ohmae Citation1990; cf. Paasi Citation2019).

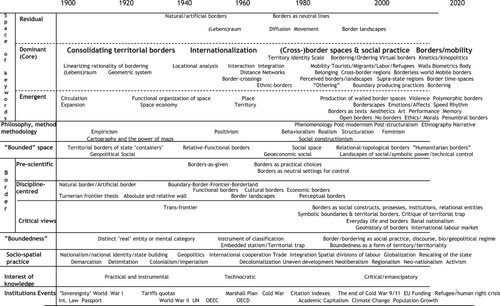

provides a generalization of the evolution of the ‘space of keywords’ in border studies. It recognizes four main phases (Consolidating territorial borders, Internationalization, Cross-border spaces and social practices, and Borders/mobility) with emerging, dominant and residual keywords (cf. Paasi Citation2011). Dominant keywords are perpetually being challenged, replaced by emergent ones at times and may become sometimes residual. Four phases are partly overlapping and express social and institutional paths, theoretical/philosophical backgrounds and interests of knowledge. Science studies show that the motives for research are both institutional and personal. Institutional interests appreciate novelty and innovation, particularly now when research is being subjected to continual assessment (Paasi Citation2011). Individual scholars are mainly moved by factors intrinsic to their disciplines, particularly the desire to contribute to a certain field and to build up a reputation in it.

Figure 1. The ‘space of keywords’ in border studies and the major social and institutional backgrounds.

As shows, the unremitting tendency to re-conceptualize borders has been linked with major societal transformations (colonialism, war, nationalism), relevant social practices and other events and episodes. The general course goes from the evolving meanings of borders for the gradually consolidating state territory and sovereignty, or the making of the geopolitical social (Cowen and Smith Citation2009), to the later re-formulation of this model resonating with the rise of economic flows, and a transfer from the opening of national spaces to border crossings, and ultimately to cross-border cooperation i.e. steps towards the geo-economic social (Cowen and Smith Citation2009). All phases are embedded in wider social and geopolitical developments, and they demonstrate scholars’ efforts to advance new conceptual interpretations of borders. also shows how human experience became gradually important in border studies and that led to qualitative ethnographic viewpoints (Megoran Citation2006). also displays that the watchwords in border studies have rapidly multiplied since the 1990s, and a conceptual complexity, diversity and new critical approaches characterize the field. Currently, borders and mobility are increasingly often two sides of the same coin which manifests itself in a rich lexis and interdisciplinary approaches. These two modalities come together in such categories as migration, transnationality, refuge, nationality and citizenship. As Axelsson (Citation2022) shows, in current border studies these categories force scholars to rethink borders dynamically and to recognize multiple space–time rhythms that migrants face and that display diverging relations between inside and outside: acceleration, expedition, deceleration, or waiting, for example.

If critical geographers have rejected the taken-for-granted views of regional borders, also border scholars have questioned state-centrism, the self-explanatory role and neutrality of territorial borders, and sovereign territory. New terminology revealed this already in the 1990s when such notions as territorial trap (Agnew Citation1994), embedded statism (Taylor Citation1996), cartographic anxiety (Krishna Citation1994) or methodological nationalism (Wimmer and Glick-Schiller Citation2002) were outlined. Yet, borders are perpetually the most palpable and sticky markers of state territoriality (Murphy Citation2022). The significance of borders still derives from the mobilization of territoriality, but the functions and meanings attached to borders are inherently vague and even contradictory (Anderson and ÓDowd Citation1999).

New emerging theoretical approaches have once again raised on agenda the seemingly eternal question, what constitutes a ‘border’ (Amilhat-Szary and Giraut Citation2015; Ochoa Espejo Citation2020; Dijstelbloem Citation2021; Axelsson Citation2022). Many scholars have noted that it is often hard to see what the ‘border’ or bordering is that scholars talk about. Shachar (Citation2020) is ready to claim that the border is one of the most important issues of our times but also least understood, because current bordering techniques have partly detached borders from the former imagined fixity of territorial geographies. In fact, geographers have argued even earlier that borders should be seen as mobile and stretching in space (Amilhat-Szary and Giraut Citation2015). Thus, not only people, goods and capital are mobile but also borders themselves that can be mobile in many ways. Borders can be understood as mobile because they are manifested in the biometric features of mobile human bodies and in their travel documents (Amoore Citation2006; Häkli Citation2015). In tourism geographies, the mobility of borders is today the order of the day (Więckowski & Timothy, Citation2021).

Bordering thus occurs in a range of practices, forms and locations and has many goals. Current border studies, often reverberating with topological thinking, highlight both spatial and temporal dimensions of bordering, thus not privileging space or time. Axelsson (Citation2022), for example, does not see borders as discrete spatial entities but looks at how time and space work through one another and she finds topological approaches particularly useful in understanding borders. As she demonstrates, borders ‘become’ in the multiple social practices of bordering, and are dynamic, fragmented and ephemeral border timespaces, that is they turn to time-space categories and webs of control that may both stretch and curtail distances and can make people both to move and to wait.

The violence of borders

The roots of state borders are often in past violence and conflicts, and these may continue even after a border has been settled. Research has revealed profound consequences for patterns of conflict and cooperation when the border is disputed. One of the key issues in this sense is mobility since the border is the site where the permission to move or not becomes materialized. Currently fetishized anxieties concerning the security and the fear of the Other but also the aim to prevent migrants from applying asylum inside the border are frequently used to justify the monitoring, policing and prevention of border-crossings and arrival into territories (see the examples in Axelsson Citation2022). Jones (Citation2016) and Dijstelbloem (Citation2021) argue that borders are violent for migrants and can turn places, routes and territories into ‘zones of death’. Violence can refer to the brutality of border guards and their use of force that can cause injuries or be lethal, but also to hazardous infrastructures. More than 75,000 migrant deaths have occurred in the Mediterranean, Africa, Asia and the Americas since 1996. Border violence is currently occurring at the border between Belorussia and the EU where the former exploits migrants in its hybrid operations. One general, ethically unsustainable form of border violence is the prevention of migrant’s mobility to search for a better life (Jones Citation2016). The world is bluntly uneven in its borders where multi-layered cultural and politico-economic geographies are in work. Echoing this van Houtum (Citation2010) labels the increased control of immigration as a form of global apartheid. Numerous scholars and activists have claimed for open borders or even ‘no borders’ since the millennium (Jones Citation2019; Sager Citation2020). They thus push the earlier ideas of a ‘borderless world’, propagated initially by neo-liberal business economists (Ohmae Citation1990) to a new level. Particularly ‘no borders’ activists make anarchist claims to eliminate not only borders but also the state and the nation, state-based sovereignties and the territorialization of people’s subjectivities (cf. Paasi Citation2019). Such ideas have received criticism from both right and left and in practice many politicians tend to underline the lack of border control rather than the need for open borders (Megoran Citation2021).

States use many strategies and counter practices to cope with immigration and to control the claims of activists (Paasi Citation2019). These strategies typically aim to reproduce the territorial power of the state. They also attempt to justify the monopoly of the state over violence and territorial control, as well as the sovereign power over the destinies of people inside the territory, for example, by controlling citizenship and border crossings. Counter practices may also emerge from hot and banal nationalism (Billig Citation1995; Koch and Paasi Citation2016), from politicians’ efforts to please the people entitled to vote, or from the embeddedness of borders in practices and discourses related to the regulation of labour markets, welfare schemes and political participation. Of course, states also use their power to take care for and support migrants who are granted refugee or asylum seeker status (Paasi Citation2019). State-based international ethics is central also in responding through humanitarian interventions to such forms of violence such as genocides, ethnic cleansing and natural disasters. Humanitarian catastrophes and the COVID-19 pandemic have displayed the deeply political and politicized nature borders and bordering, and the politicking practiced mainly by right-wing factions but also by ‘vaccine nationalists’. The ongoing political conflicts have also highlighted the allure of territory particularly among the right-wing nationalists (Murphy Citation2022). ‘Borderless world’, whatever it could be, would undoubtedly demand some form of global government, substantial changes in current global understanding, international coordination of the levels of social security and the standards of living, and likewise new sources for identities alternative to destructive nationalism.

Contested tendencies of de- and re-bordering and their ideological backgrounds

Many scholars have highlighted the flexibility of current state territory and how it is partly ‘giving up’ in the globalizing world. Sassen (Citation2009), for example, argues that while the exclusive territorial authority of the state continues as predominant, the constitutive foundations of such authority are now less absolute than they were once intended to be. Similarly, the critical site for making and registering that change is not inexorably the traditional territorial border. For example, ‘nations’ living in diaspora have today much better tools to join up across borders with social media than earlier.

Yet, the attempts to open, transform, or remove territorial borders seem to coexist with the imperative of state governments to build new ones. Border closures witnessed during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic were at first exceptionally widespread, but they were only one – temporary? – expression in the longer trajectory towards bordering. Current vigorous construction of walls around the world is a relatively recent phenomenon. There existed only 7 walls or fences worldwide after the Second World War, 15 after the Berlin Wall collapsed (1989), and about 80 in year 2018 (Vallet Citation2017; Hjelmgaard Citation2018). Border wall construction is frequently about economic security, which implies the protection of earlier attained privileges. Hence borders that separate economies with very different levels of development are likely to be unstable; cross-border inequality is found to be a core predictor of wall presence and construction (Carter and Poast Citation2015).

Such re-bordering is also taking place in Europe. A couple of years ago Federica Mogherini, then EU’s foreign policy chief, criticized Donald Trump’s plans to build the wall on the US–Mexico border. However, Europe itself is now investing huge sums of money on border control because of the growing worries of the possible future migration crises. Many European states refuse to take immigrants and construct new walls (Dettmer Citation2021). There were only two fences in Europe in the 1990s, but this figure was already 15 in 2017. These tendencies prove that state borders are disputed and resonate evermore often with politicking and xenophobia. Indeed, current building of walls and fences has been interpreted as producing ‘theatre pieces’ for national populations that are anxious about global forces represented as threatening sovereignty and identity at both individual and state level (Brown Citation2010). State security and societal security can be distinguished analytically (McSweeney Citation1999, 68–78). The former has sovereignty as its ultimate criterion, the latter identity. Both resonate with and become often fused in the case of territorial borders.

Consequently, efforts towards de-bordering and re-bordering are parallel, context-bound socio-spatial processes that have a material basis but that are also related to broader ideologies and spatial socialization. The extremes of such ideologies are perhaps cosmopolitanism and ethnonationalism. Cosmopolitan thinkers see territorial state system as unjust, invite us to think about people, space and place relationally, to open or reject national and cultural borders, and to recognize that relational transnational spaces could help us to care for others considering their shared humanity (Warf Citation2021, 4). As Delanty (Citation2009, 7) notes, ‘thinking beyond the established forms of borders is an essential dimension of the cosmopolitan imagination’, in which ‘no clear lines can be drawn between inside and outside, the internal and external’.

Different cosmopolitan institutional proposals are still politically unfeasible today (Stilz Citation2019, 8). The allure of territory persists for states and their ideological structures (Murphy Citation2013, Citation2022), reflecting the power of both social spatialization and spatial socialization. This is particularly obvious in ethnonationalist thinking that rejects cosmopolitan reasoning, and emphasizes ethnic heritage, social boundaries and, from time-to-time, racial dividing lines in the making of national states. It may hence also aim to separate social groupings inside states, at times violently (Kecmanovic Citation1996). This ideology is bolstering now around the world, particularly among many right-wing movements that use social media effectively in territorializing subjectivities. Besides exclusive ethnonationalism, borders and their policing are also embedded in ostensibly more neutral national identity narratives that are part of spatial socialization in practically all national states (Paasi Citation1996; cf. Rheindorf and Wodak Citation2018). Territory seems to be constantly an important but given element in such narratives (cf. Smith Citation1991).

Why borders and bordering persist so stubbornly?

Alec Murphy (Citation2022) analyses in his Vega presentation the appeal of state territory. The following discussion complements his ideas by scrutinizing the modalities of bordering. To understand what territorial (state) borders are, why they persist and become politically laden, it is useful to look at how they are embedded in spatial socialization and are performed in social practices and discourses. This occurs typically in the form of two overlapping modalities of bordering (Paasi Citation2012). First, borders exist as technical landscapes of social control that are justified by flexible but coercive institutions such as sovereignty, citizenship, state governance, security and control/regulation that draw on various border ‘timespaces’ (Axelsson Citation2022). These landscapes are thus above all manifestations of state power. Graham (Citation2010, 89) argues that states are becoming internationally organized systems geared towards trying to separate people and circulations considered risky or malign from those deemed risk-free or worthy of protection. This disconnection occurs both inside and outside of state’s territorial borders and results in a blurring between international and urban/local borders so that local, national and global constitute no more a simple hierarchy. Much of border research since the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the USA has focused on such technical landscapes, which build on increasingly sophisticated technological innovations that are mobilized to practice both selective geo- and biopolitical control over (mobile) human bodies (Dijstelbloem Citation2021). This is occurring around the world. Also, European Union’s organizations actively investigate how artificial intelligence technologies could be developed and implemented in border control in the name of security. Biometric identification, risk calculation or emotion detection have been installed or tested at its borders (Dumbrava Citation2021). It is not only people who move but states also move their borders inwards and outwards to prevent unwanted entrances (Shachar Citation2020; Axelsson Citation2022). Technical landscapes are frequently all-pervading inside states but can also be outsourced beyond state borders. This has occurred in many states or been based on internationally coordinated bordering and control practices, as in the case of EU’s Frontex organization or in the case of so-called humanitarian borders that tend to hide and perhaps depoliticize the violence of bordering. Thus, the militarization of border control is an evolving, highly relevant topic in border studies (Jones and Johnson Citation2016). Militarization can lead to the globalization of bordering. Miller (Citation2019), for example, shows how the US border has literally stretched around the world, forming a new regime which is tied with the escalating militarization of the US and that manifests itself in several hundreds of US military camps around the world.

Second, if the technical landscapes of social control are tools of governments that can be explicitly or distantly violent, and strive to justify and control inside and outside, state borders are at the same time powerful ideological and symbolic institutions and processes, forming discursive landscapes of social/symbolic power/control that reproduce not only the imaginings, ideologies, emotions and passions related to nation, but also national identity narratives that reverberate with collective memory (Paasi Citation2016, Citation2020; Murphy Citation2013). Such landscapes come into being also materially in memorial sites (e.g. military cemeteries) and other landscapes elevated as ‘national’ that provide classical nourishment for state territoriality and nationalism, and powerful ideas of loss, often highlighting specific borders as theatres of historical violence and sacrifice. Thus, to understand such landscapes, we must examine how collective territorial identities, shared memories and traditions evolve contextually and in which practices and discourses they are produced and reproduced. Often some specific state border becomes a significant symbol of the nation that brings together the past, the present and the future. Good examples are the Finnish state and the meanings attached to the Soviet/Russian border (Paasi Citation1996) or in the US, to the US-Mexican border. The meanings of different borders may thus vary but some borders are frequently fetishized as sacred or holy entities. Since borders are critical in the institutionalization of territorial spaces, they become vital for spatial socialization. Discursive landscapes of social/symbolic power are mediated into everyday life in the form of hot and banal nationalism but also in formal national socialization (Paasi Citation2016). Teaching geography and history have been critical subjects in national(ist) education in most states and seem to be today under strict control particularly in autocratic states. Both histories and geographies are often rewritten to help to preserve the power of the existing authorities. Fetishization of borders reinforces the separation of territorial spaces from each other even if, as Agnew notes, ‘for most of world history, and increasingly so, all sorts of transactions involving people, goods, services and capital flow backward and forward over, through, under, and around territorial borders’ (see Paasi et al. Citation2022).

Technical and symbolic landscapes thus take form not only at the border region but stretch into multiple spaces of control, spatial socialization/subjectification and bestow human bodies and minds with national signs and symbols. Technical landscapes in particular have diffused into shopping centres, streets and airports where mobile people are monitored with sophisticated tools such as biometric identity techniques, digital surveillance, risk analysis and data-banking (Amoore Citation2006; Häkli Citation2015). These two modalities make easier to understand how borders exist, are set into ‘border work’ and, also, how borders are actually social relations set up in the production and reproduction of territory. They also demonstrate how borders, and the processes of bordering are scattered in state space and may stretch beyond the ostensibly fixed territoriality of states. Yet, borders are not literally ‘everywhere’, as Balibar (Citation1998) once suggested. Not only the decisions regarding borders and the forms of bordering are typically made in national centres and increasingly in international networks, but cities are also zones, where border struggles and the practices of bordering are highly intensive and scalar processes come together (Graham Citation2010).

Coda: ‘Progress’ in the studies of bounded spaces and borders?

Progress has always been one of the ideals of scientific work, but this ambiguous notion means different things at different times and places (Livingstone Citation2006). Similarly, it has various meanings for different epistemic communities. In this section I will discuss, partly inspired by the presentations at the Vega symposium, partly by the discussion above, what could be progress in the critical geographical research focusing on regions, territories and borders/bordering. Philosopher Ilkka Niiniluoto (Citation2019) notes how the notion of science refers to many interconnected spheres: to a social institution, researchers, research process, the methods of inquiry, or scientific knowledge. Correspondingly, he suggests that progress can be understood in relation to each such sphere and recognizes several forms of progress: economical (e.g. the increased funding of research), professional (the rising status of scientists and their institutions in the society), educational (the increased skills and expertise of the scientists), methodical (invention of new research methods or the improvement of scientific instruments) and cognitive progress (increase or advancement of scientific knowledge). Scientific progress can also be linked to technological advancement (increased effectiveness of tools and techniques) and social progress (economic prosperity, quality of life, justice in society).

When thinking the expansion of the theoretical and concrete studies of regions, territories and borders during the last 20–30 years or so, all such types of progress have become apparent in geography. As the contributions in this special issue demonstrate, in quantitative terms the research and publications on regions, territories and borders have increased strikingly since the 1990s. This is partly because of the number of researchers and publication forums has expanded, partly since the funding for research focusing on bounded spaces and especially on borders has increased around the world. Likewise conceptual progress has occurred. A significant stimulus has been the border-migration nexus which has attracted massive scholarly attention since the 1990s and raised moral and ethical concerns to the fore (Paasi Citation2019).

One laudable step of progress in the research on regions, territories and borders is the fact that such studies have become ever more international. Yet, as noted above, despite the noble ideal of a ‘borderless academy’ and freely ‘travelling’ ideas, academic communication, publishing and the exchange of ideas echo contextuality and power relations. Knowledge is constantly under negotiation and tends to alter when it circulates (Agnew and Livingstone Citation2011). Many geographers have noted power-knowledge relations during the last few decades and contend that not only spatial contexts but also languages condition the production of scientific knowledge. An uneven ‘geopolitics of knowledge’ is embedded in academic communication, since both languages and publication forums are structured asymmetrically in global space (Paasi Citation2015). Many non-English-speaking scholars have criticized the Anglophone hegemony in academia, which appears in the domination of English as a publishing language, but also in the self-evident status given to theoretical ideas and research agendas that travel from the ‘Anglophone-core’ to peripheries. Despite such power relations, it is ever more difficult to say now, and perhaps there is no need to declare, where the cores and peripheries of regional theory and border studies are today (Paasi Citation2022). Besides language, geographers’ epistemic community displays also other critical social relations of power and dividing lines that position members unequally, such as North–South-axis, gender, generation and ethnicity, and freedom of speech in general and academic freedom in particular, for example.

When thinking progress from a cognitive viewpoint, i.e. the increase of scientific knowledge, an important sign of progress has been the rise of critical work that has challenged (and re-conceptualized) bounded spaces, borders and bordering in both theory and practice. Likewise, research methods and conceptual approaches have developed fast (see ). Equally valuable has been the expanding critique of the spatialities of essentialist, exclusive identities and ideologies (particularly in the context of nationalism and ethno-regionalism) that are frequently mobilized by fetishizing the boundedness of spatial entities. We must thus ask what it means to argue that there is an identity related to some spatial unit and/or to the people who inhabit it? (cf. Billig Citation1995). Such critiques benefit also other forms of ‘progress’, i.e. professional, and methodical. The need for such critique was pertinently articulated by Soja (Citation1989, 6) as follows:

We must be insistently aware how space can be made to hide consequences from us, how relations of power and discipline are inscribed into the apparently innocent spatiality of social life, how human geographies become filled with politics and ideology.

There is of course one more serious question: why there exists a tendency to think that regional or territorial spaces should be self-evidently bounded and separate from the external world which particularly in the case of state borders often paves the way to unfriendly, if not aggressive and violent attitudes and actions between social groupings inhabiting such spaces? Despite globalization, the rise of cosmopolitan thinking and the opening of borders for economy, tourism, or educated elites in transnational markets, states and governments stubbornly use their power to regulate both social spatialization and spatial socialization in controlling their territory, borders, identities, loyalties and who gets in and who does not. States thus not only regulate borders and mobilities but also tend to territorialize consciousness and imagination. Balibar (Citation1998, 216) once reminded that what can be ‘demarcated, defined, and determined, has a constitutive relation with what can be thought’. Likewise, also Agnew (Citation2008, 176) notes how borders trap thinking about and acting in the world in territorial terms but also limit the exercise of ‘intellect, imagination and political will’.

Such observations take us again back to the question of progress, which in social sciences inevitably forces us to think about the modalities of the political. Progress may be both a regulative ideal and an ethical goal: it forces us to keep academic debates and critical research on the move and to struggle to make the world a better place (Livingstone Citation2006; cf. Lee et al. Citation2009). If we want to change and advance thinking about the geographical world towards a more open direction, even though perhaps not achieving a ‘borderless’ world, and to avoid national and ethnic skirmishes that are often associated or mediated by territorial borders, we must start to rethink what and how we teach about borders and bounded spaces to children, young people and other audiences. Therefore, bounded spaces, regions and territories, and their borders are incessantly both significant academic concepts and concrete sites for research and politics that force us to reflect the moral consequences of the mobilization of these categories in social action, education and everyday life. For (im)migrants in particular the territory-border nexus has always been problematic. It is not only state borders that matter but also regional borders and the borders of rights, labour markets, welfare and citizenship that persistently limit full (political) participation in the society (Pécoud and de Guchteneire Citation2007; Paasi Citation2019; Axelsson Citation2022). A critical geography of bounded spaces must struggle to make visible and resists such inequalities, to trace the material and ideological practices of how regional and territorial spaces are produced and reproduced and how such spaces and their borders are made meaningful in various contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agnew, J. 1994. “The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory.” Review of International Political Economy 1 (1): 53–80.

- Agnew, J. A. 1995. “Book Review of Territories, Boundaries and Consciousness.” Geografiska Annaler B 78 (3): 181–182.

- Agnew, J. 2008. “Borders on the Mind: Re-Framing Border Thinking.” Ethics & Global Politics 1 (4): 175–191.

- Agnew, J. 2017. Globalization and Sovereignty. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Agnew, J., and D. Livingstone. 2011. “Introduction.” In The Sage Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, edited by J. Agnew and D. Livingstone, 1–17. London: Sage.`

- Allen, J. 2016. Topologies of Power. Beyond Territory and Networks. London: Routledge.

- Allen, J., and L. Axelsson. 2019. “Border Topologies: The Time-Spaces of Labour Migrant Regulation.” Political Geography 72: 116–123.

- Allen, J., D. Massey, and A. Cochrane. 1998. Rethinking the Region. London: Routledge.

- Allmendinger, P., and G. Haughton. 2009. “Soft Spaces, Fuzzy Boundaries, and Metagovernance: The new Spatial Planning in the Thames Gateway.” Environment and Planning A 41 (3): 617–633.

- Amilhat-Szary, A.-L., and F. Giraut. 2015. Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Amin, A. 2004. “Regions Unbound: Towards a New Politics of Place.” Geografiska Annaler B 25 (1): 33–44.

- Amoore, L. 2006. “Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror.” Political Geography 25: 336–351.

- Anderson, J. 2000. “The Rise of Regions and Regionalism in Western Europe.” In Governing European Diversity, edited by M. Guibernau, 35–64. London: Sage.

- Anderson, J., and L. ÓDowd. 1999. “Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance.” Regional Studies 33 (7): 593–604.

- Axelsson, L. 2022. “Borders as Time-Spaces of Authority: The Regulation of Cross-Border Movements and Rights.” Geografiska Annaler B 104 (1): 59–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2027260

- Balibar, É. 1998. “The Borders of Europe.” In Cosmopolitics, edited by P. Cheah and B. Robbins, 216–233. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

- Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

- Brighenti, A. M. 2010. “On Territorology: Towards a General Science of Territory.” Theory, Culture, Society 27 (1): 52–72.

- Bristow, G. 2010. Critical Reflections on Regional Competitiveness. Theory, Policy, Practice. London: Routledge.

- Brown, W. 2010. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. New York: Zone books.

- Carter, D. B., and P. Poast. 2015. “Why Do States Build Walls? Political Economy, Security, and Border Stability.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (2): 239–270.

- Christopherson, S., and J. Clark. 2007. Remaking Regional Economies. London: Routledge.

- Cowen, D., and N. Smith. 2009. “After Geopolitics? From the Geopolitical Social to Geoeconomics.” Antipode 41 (1): 22–48.

- Cronin, B. 2005. The Hand of Science: Academic Writing and its Rewards. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

- Cunningham, H. 2020. “Necrotone: Detah-Dealing Volumetrics at the US-Mexico Border.” In Voluminous States: Sovereignty, Materiality, and the Territorial Imagination, edited by F. Billé, 131–145. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Dalby, S. 2020. Anthropocene Geopolitics: Globalization, Security, Sustainability. Ottawa: Ottawa University Press.

- Deas, I., and A. Lord. 2006. “From a New Regionalism to an Unusual Regionalism? The Emergence of Non-standard Regional Spaces and Lessons for the Territorial Reorganisation of the State.” Urban Studies 43 (10): 1847–1877.

- Delaney, D. 2005. Territory: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Delanty, G. 2009. The Cosmopolitan Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dettmer, J. 2021. “Fortress Europe Takes Shape as EU Countries Fear Bigger Migration Flows”. https://www.voanews.com/a/europe_fortress-europe-takes-shape-eu-countries-fear-bigger-migration-flows/6219293.html.

- Dijstelbloem, H. 2021. Borders as Infrastructure. The Technopolitics of Border Control. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Dumbrava, C. 2021. Artificial Intelligence at EU Borders: Overview of Applications and Key Issues. Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service.

- Elden, S. 2010. “Land, Terrain, Territory.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 799–817.

- Entrikin, J. N. 2010. Regions: Critical Essays in Human Geography. London: Routledge.

- Gottmann, J. 1973. The Significance of Territoriality. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

- Graham, S. 2010. Cities Under Siege: A New Military Urbanism. London: Version.

- Gregory, D. 1978. Ideology, Science and Human Geography. London: Hutchinson.

- Haggett, P. 1965. Locational Analysis in Human Geography. London: Edward Arnold.

- Häkli, J. 2015. “The Border in the Pocket: The Passport as a Boundary Object.” In Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders, edited by A.-L. Amilhat-Szary and F. Giraut, 85–99. London: Palgrave.

- Hartshorne, R. 1939. The Nature of Geography. Lancaster, PE: The Association of American Geographers.

- Hjelmgaard, K. 2018. “From 7 to 77: There’s Been an Explosion in Building Border Walls since World War II.” https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/05/24/border-walls-berlin-wall-donald-trump-wall/553250002/.

- Jessop, B. 2000. “The Crisis of the National Spatio-Temporal Fix and the Tendential Ecological Dominance of Globalizing Capitalism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24 (2): 323–360.

- Jessop, B. 2018. “The TPSN Schema: Moving Beyond Territories and Regions.” In Handbook of the Geographies of Regions and Territories, edited by A. Paasi, J. Harrison, and M. Jones, 89–101. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Johnson, C., R. Jones, A. Paasi, L. Amoore, A. Mountz, M. Salter, and C. Rumford. 2011. “Interventions on Rethinking ‘the Border’ in Border Studies.” Political Geography 30: 61–69.

- Jones, R. 2016. Violent Borders. London: Verso.

- Jones, M. 2018. “Introduction: For a New New Regional Geography.” In Reanimating Regions: Culture, Politics, and Performance, edited by J. Riding and M. Jones. London: Routledge.

- Jones, R. 2019. Open Borders: In Defense of Free Movement. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

- Jones, M. 2022. “For a New New Regional Geography: Plastic Regions and More-Than-Relational Regionality.” Geografiska Annaler B. 104 (1): 43–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2028575

- Jones, R., and C. Johnson. 2016. “Border Militarisation and the re-Articulation of Sovereignty.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (2): 187–200.

- Katzenstein, P. 2005. A World of Regions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Keating, M. 1998. The New Regionalism in Western Europe. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Keating, M. 2017. “Contesting European Regions.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 9–18.

- Kecmanovic, D. 1996. The Mass Psychology of Ethnonationalism. New York: Planun Press.

- Kimble, G. H. T. 1951. “The Inadequacy of the Regional Concept.” In London Essays in Geography, edited by L. D. Stamp and S. W. Woolridge, 151–174. London: Longmans Green.

- Koch, N., and A. Paasi. 2016. “Banal Nationalism 20 Years on: Re-Thinking, re-Formulating and re-Contextualizing the Concept.” Political Geography 54: 1–6.

- Kohlenberg, P., and N. Godehardt. 2020. The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics. London: Routledge.

- Kolossov, V., and J. Scott. 2013. “Selected Conceptual Issues in Border Studies.” Belgeo 13: 1–19.

- Krishna, S. 1994. “Cartographic Anxiety: Mapping the Body Politic in India.” Alternatives 19: 507–521.

- Lee, R., N. Castree, V. Lawson, A. Paasi, S. Radcliffe, and C. Withers. 2009. “Editorial: Progress in Human Geography?” Progress in Human Geography 33 (1): 3–6.

- LeGales, P., and C. Lequesne. 1998. Regions in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Leimgruber, W. 1991. “Boundary, Values and Identity: The Swiss-Italian Transborder Region.” In The Geography of Border Landscapes, edited by D. Rumley and J. V. Minghi, 43–62. London: Routledge.

- Livingstone, D. N. 2006. “Putting Progress in its Place.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (5): 559–579.

- Macleod, G., and M. Jones. 2001. “Renewing the Geography of Regions.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19 (6): 669–695.

- Massey, D. 1978. “Regionalism: Some Current Issues.” Capital and Class 2 (3): 106–125.

- Massey, D. 1993. “Power-geometry and the Progressive Sense of Place.” In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Change, edited by J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G. Robertson, and L. Tickner, 59–69. London: Routledge.

- Massey, D., and N. Clark. 2008. “Introduction.” In Material Geographies, edited by N. Clark, D. Massey, and P. Sarre, 1–6. London: Sage.

- McSweeney, B. 1999. Security, Identity and Interest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Megoran, N. 2006. “For Ethnography in Political Geography: Experiencing and re-Imagining Ferghana Valley Boundary Closures.” Political Geography 25 (6): 622–640.

- Megoran, N. 2021. “Borders on Steroids: Open Borders in a Covid-19 World?” Political Geography 91 (1): 102443.

- Miller, T. 2019. Empire of Borders. The Expansion of the U.S. Border Around the World. London: Verso.

- Minshull, R. 1967. Regional Geography: Theory and Practice. London: Hutchinson.

- Montgomery, S. 2003. The Chicago Guide to Communicating Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moore, M. 2015. A Political Theory of Territory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, A. B. 1991. “Regions as Social Constructs: The Gap Between Theory and Practice.” Progress in Human Geography 15 (1): 23–35.

- Murphy, A. B. 2013. “Territory’s Continuing Allure.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103 (5): 1212–1226.

- Murphy, A. B. 2022. “Taking Territory Seriously in a Fluid, Topologically Varied World: Reflections in the Wake of the Populist Turn and the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Geografiska Annaler B. 104 (1): 27–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.2022987

- Newman, D., and A. Paasi. 1998. “Fences and Neighbours in the Postmodern World. Boundary Narratives in Political Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 22 (2): 186–207.

- Niiniluoto, I. 2019. “Scientific Progress.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-progress/?source = post_page (loaded 14.11.2021).

- Nijkamp, P. 2021. “Borders as Opportunities in the Space-Economy: Towards a Theory of Enabling Space.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 5: 223–239.

- Ochoa Espejo, P. 2020. On Borders: Territories, Legitimacy, and the Rights of Place. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ohmae, K. 1990. Borderless World. London: Harper Collins.

- Ó Tuathail, G. and S. Dalby. 1998. “Introduction: Rethinking Geopolitics: Towards a Critical Geopolitics,” In Rethinking Geopolitics edited by G. Ó Tuathail and S. Dalby, 1-15. London: Routledge.

- Paasi, A. 1986. “The Institutionalization of Regions: A Theoretical Framework for Understanding the Emergence of Regions and the Constitution of Regional Identity.” Fennia 164 (1): 105–146.

- Paasi, A. 1991. “Deconstructing Regions: Notes on the Scales of Human Life.” Environment and Planning A 23 (2): 239–256.

- Paasi, A. 1996. Territories, Boundaries and Consciousness: The Changing Geographies of the Finnish-Russian Border. Chichester: Wiley.

- Paasi, A. 2003. “Territory.” In A Companion to Political Geography, edited by J. Agnew, K. Mitchell, and G. Toal, 109–122. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Paasi, A. 2009. “Bounded Spaces in a ‘Borderless World’? Border Studies, Power, and the Anatomy of the Territory.” Journal of Power 2 (2): 213–234.

- Paasi, A. 2011. “From Region to Space, Part II.” In Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Human Geography, edited by J. A. Agnew and J. S. Duncan, 161–175. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Paasi, A. 2012. “Border Studies re-Animated: Going Beyond the Relational/Territorial Divide.” Environment and Planning A 44: 2303–2309.

- Paasi, A. 2015. “Academic Capitalism and the Geopolitics of Knowledge.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Political Geography, edited by J. Agnew, A. Secor, V. Mamadouh, and J. Sharp, 509–523. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Paasi, A. 2016. “Dancing on the Graves: Independence, Hot/Banal Nationalism and the Mobilization of Memory.” Political Geography 54: 21–31.

- Paasi, A. 2019. “Borderless Worlds and Beyond: Challenging the State-Centric Cartographies.” In Borderless Worlds for Whom? Ethics, Moralities and Mobilities, edited by A. Paasi, E.-K. Prokkola, J. Saarinen, and K. Zimmerbauer, 21–36. London: Routledge.

- Paasi, A. 2020. “Nation, Territory and Memory: Making State-Space Meaningful.” In A Research Agenda for Territory and Territoriality, edited by D. Storey, 61–82. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Paasi, A. 2021. “Problematizing “Bordering, Ordering and Othering” as Manifestations of Socio-Spatial Fetishism.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 112 (1): 18–25.

- Paasi, A. 2022. “The Institutionalization of Regions: An Autobiographic View on the Making of Socio-Spatial Theory in the Nordic Periphery.” In Socio-Spatial Theory in Nordic Geography. Intellectual Histories and Critical Interventions, edited by P. Jakobsen, E. Jönsson, and H. Gutzon Larsen. New York: Springer. (forthcoming).

- Paasi, A., Md A. Ferdoush, J. Agnew, A. B. Murphy, R. Jones, P. Ochoa Espejo, J. J. Fall, and G. Peterle. 2022. “Intervention: Locating the Territoriality of Territory in Border Studies.” Political Geography (in print).

- Paasi, A., J. Harrison, and M. Jones. 2018. “New Consolidated Regional Geographies.” In Handbook on the Changing Geographies of Regions and Territories, edited by A. Paasi, J. Harrison, and M. Jones, 1–20. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Paasi, A., and J. Metzger. 2017. “Foregrounding the Region.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 19–30.

- Paasi, A., and K. Zimmerbauer. 2016. “Penumbral Borders and Planning Paradoxes: Relational Thinking and the Question of Borders in Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning A 48 (1): 75–93.

- Painter, J. 2010. “Rethinking Territory.” Antipode 42 (5): 1090–1118.

- Palonen, K. 2003. “Four Times Politics: Policy, Polity, Politicking, and Politicization.” Alternatives 28 (2): 171–186.

- Parker, N., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2009. “Lines in the Sand? Towards an Agenda for Critical Border Studies.” Geopolitics 14 (3): 582–587.

- Pécoud, A., and P. de Guchteneire. 2007. Migration Without Borders. Essays on the Free Movement of People. Paris: Unesco Publishing and Berghahn Books.

- Pred, A. 1984. “Place as Historically Contingent Process: Structuration and the Time-Geography of Becoming Places.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 74 (2): 279–297.

- Ratzel, F. 1898. Politische Geographie. Munich/Leipzig: Oldenbourg.

- Rheindorf, M., and R. Wodak. 2018. “Borders, Fences, and Limits – Protecting Austria from Refugees: Metadiscursive Negotiation of Meaning in the Current Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 15–38.

- Rodriquez-Pose, A. 2020. “The Rise of Populism and the Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter.” LSE Public Policy Review 1.

- Sack, R. D. 1986. Human Territoriality: A Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sager, A. 2020. Against Borders: Why the World Needs Free Movement of People. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Sassen, S. 2009. “Bordering Capabilities Versus Borders: Implications for National Borders.” Michigan Journal of International Law 30 (3): 567–597.

- Scholte, A. 2005. Globalization: A Critical Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Scott, A. 1998. Regions and the World-Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shachar, A. 2020. The Shifting Border: Legal Cartographies of Migration and Mobility. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

- Shields, R. 1992. Places on the Margin. London: Routledge.

- Shields, R. 2013. Spatial Questions: Cultural Topologies and Social Spatializations. London: Sage.

- Sibley, D. 1995. Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West. London: Routledge.

- Smith, A. D. 1991. National Identity. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

- Söderbaum, F. 2003. “Introduction: Theories of New Regionalism.” In Theories of New Regionalism: A Palgrave Reader, edited by F. Söderbaum and T. M. Shaw, 1–21. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Soja, E. 1971. “The Political Organization of Space.” Commission on College Geography, Resource Paper No. 8.

- Soja, E. 1989. Postmodern Geographies. The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. London: Verso.

- Soja, E. 2005. “Borders Unbound. Globalization, Regionalism, and the Postmetropolitan Transition.” In B/Ordering Space, edited by H. Van Houtum and O. Kramsch, 33–46. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Stilz, A. 2019. Territorial Sovereignty: A Philosophical Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Storey, D. 2020. A Research Agenda for Territory and Territoriality. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Storper, M. 1997. Regional World: Territorial Development in a Global Economy. New York: Guilford Press.

- Taylor, P. J. 1996. “Embedded Statism and the Social Sciences: Opening Up to New Spaces.” Environment and Planning A 28: 1917–1928.

- Thrift, N. 1983. “On the Determination of Social Action in Time and Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 1 (1): 23–57.

- Urry, J. 2003. Global Complexity. Cambridge: Polity.

- Vallet, E. 2017. Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity? London: Routledge.

- van Houtum, H. 2010. “Human Blacklisting: The Global Apartheid of the EU’s External Border Regime.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6): 957–976.

- Walsh, C. 2015. “Creating a Space for Cooperation: Soft Spaces, Spatial Planning and Cross-Border Cooperation on the Island of Ireland.” In Soft Spaces in Europe. Re-Negotiating Governance, Boundaries and Borders, edited by P. Allmendinger, G. Haughton, J. Knieling, and F. Othengrafen, 192–211. London: Routledge.

- Warf, B. 2021. Geographies of Cosmopolitanism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Więckowski, M., and D. J. Timothy. 2021. “Tourism and an Evolving International Boundary: Bordering, Debordering and Rebordering on Usedom Island, Poland-Germany.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 22, 100647.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Glick-Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation–State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334.

- Zimmerbauer, K., and A. Paasi. 2020. “Hard Work with Soft Spaces (and Vice-Versa): Problematizing the Transforming Planning Spaces.” European Planning Studies 28 (4): 771–789.