Abstract

This article is published as part of the Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography special issue based on the Vega symposium: 'Bounded spaces in question: X-raying the persistence of regions, territories and borders, edited by Anssi Paasi.

ABSTRACT

The distorted shape of many of today’s political borders has been widely noted. An increasingly sprawling body of literature in geography and beyond has explored the growing spatial ambiguity of borders which are now seen as both externalized and networked throughout society. There is some recognition that the spatial reconfiguration of borders to appear in locations that challenge conventional assumptions about the relationship between state, border and territory may involve a temporal dimension; however, the many ways in which time and space work through each other to shape what it means to move in and out of a political community have remained largely overlooked. In order to make sense of the complex temporal and spatial entanglements involved in contemporary bordering processes, I advance an understanding of borders as devices which selectively contract and expand the distance between internal and external spaces and mobilize and immobilize migrants by altering the speed and rhythm of their movements. A focus on dynamic, fragmented and ephemeral border timespaces, in my view, offers a more nuanced account of how the cross-border movements of migrants are currently regulated.

Introduction

Interest has renewed in the spatial ambiguity of borders over the last couple of decades. A now substantial body of scholarship in geography and beyond has demonstrated that the international mobility of people is no longer primarily regulated at ports of entry into a given territory but through a complex web of increasingly spatially ambiguous border controls both beyond and within state territories (e.g. Bialasiewicz Citation2012; Coleman Citation2007a; Vaughan-Williams Citation2010; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018). According to this literature, borders have been pushed outwards to points of embarkation and to international waters. There has been a concurrent rise in interior spaces of border control, and many people on the inside are now living as though they were part of the outside (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Bigo Citation2001; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2012). Contemporary bordering practices consequently appear to challenge much of the conventional understanding of the relationship between state, border and territory.

It is increasingly recognized, however, that by privileging space and spatialities in the analysis of borders, the critical border studies literature might have overlooked the profound temporalizing effects of border regimes (e.g. Axelsson, Malmberg, and Zhang Citation2017; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013). Indeed, contemporary bordering practices displace borders just as much in time as in space. They establish deadlines, time limits and intervals with which migrants must comply to become eligible for protection (Tazzioli Citation2018) and settlement and associated rights (e.g. Anderson Citation2010; Axelsson Citation2017); they distort relationships between past, present and future (Amoore and de Goede Citation2008; Axelsson, Malmberg, and Zhang Citation2017; Drangsland Citation2020b); and they selectively regulate the pace of migratory movements (Andersson Citation2014; Axelsson Citation2018a; Cwerner Citation2004; Papadopoulos, Stephenson, and Tsianos Citation2008; Sontowski Citation2018; Tazzioli Citation2018).

Simply shifting the focus to an understanding of borders as a temporal rather than a spatial arrangement or adding a temporal dimension to an already spatial analysis of borders might not necessarily help us account for the full complexity of contemporary bordering practices. Instead, this paper argues that it is necessary to think time and space together, to consider how time and space work through each other (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Axelsson Citation2013) in order to produce more precise accounts of what it means to gain access to and move in and out of a political community.

This paper uses the example of labour migrants, that is, people who move through the designated channels established through labour migration policies, to explore how time and temporality shape the spatialities of borders in quite specific ways. Labour migrants are a relatively understudied group in critical border studies, a field that has tended to place more emphasis on so-called ‘illegal’, ‘irregular’ or ‘undesired’ migration and the often violent practices of detention and deportation (but see, e.g. Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013). However, a fuller understanding of how time and temporality distort the spatiality of borders in increasingly complex ways demands that the subtler registers of power involved in the management of other routine forms of international mobility be included in the analysis. These subtler temporal and spatial entanglements can perhaps be seen as the latest in a series of border reconfigurations which in combination challenge the understanding of borders as lines enclosing state territories (see Paasi Citation2022 in this issue for an overview).

The next section of the paper explores in more detail the spatialities and temporalities involved in contemporary bordering practices. It outlines how critical border scholars have tended to understand borders as either a spatial or a temporal arrangement while largely overlooking how time and space work through each other to shape international mobility and migration. I then engage with the work of a range of scholars who have emphasized in different ways the importance of holding time and space together in geographical analysis. Although based in different philosophical traditions, these scholars share an interest in how speed and distance work through each other to shape our relationship to the world around us. For example, the relational understanding of time‒space found in the work of David Harvey (Citation1990) and Jon May and Nigel Thrift (Citation2001) allows for distances between places to compress and expand, fold in upon themselves and twist in paradoxical ways as the speed of movement alters, which is in contrast to scholars such as Torsten Hägerstrand (Citation1973, 76), who understands space and time as inherently Euclidean, indeed, as ‘one unified geometrical space-time’ in which the speed of movement and the time at one’s disposal determine the distance one can travel. Following that, I draw on the example of labour migration to show how time is an integral part of the ways in which borders have changed shape in recent years rather than acting as a supplement to a spatial analysis of contemporary bordering practices. More specifically, I take inspiration from the aforementioned scholarship on the relationship between speed and distance along with another mode of time, namely rhythm, to set out two ways in which time and space work through each other to shape the cross-border movements of migrant labour – expedited crossings and departures and halted entries, suspended mobilities. In the final part of the paper, I try to bring out the contributions this particular way of thinking time and space together can make towards understanding contemporary bordering practices. At the same time, I highlight the tensions between, on the one hand, the contingent nature of any such border timespace and, on the other hand, the inert desire for borders which characterize contemporary societies.

Border spatialities and temporalities

There has been intense debate over the last few decades about the growing spatial ambiguity of borders. A sprawling body of literature in geography and beyond has demonstrated that borders are, to quote Étienne Balibar (Citation2002, 91) no longer ‘localizable in an unequivocal fashion'. Rather than fixed territorial lines, borders are seen as spatially mobile arrangements which are both externalized and networked throughout society. Governments have reached out beyond their territories, pushing their borders outwards to points of embarkation, to the routes along which migrants travel and into the digital realm (e.g. Amoore Citation2006; Bialasiewicz Citation2012; Coleman Citation2007b; Salter Citation2004; Mountz Citation2011a; Vaughan-Williams Citation2010; Weber Citation2006). The European Union (EU), for example, has externalized its borders by integrating so-called safe countries into its border regime, by patrolling international waters and enrolling airlines to act as border guards, by investing in a host of smart border technologies and by constructing a network of detention centres on the edges of or indeed outside its territory (Papadopoulos, Stephenson, and Tsianos Citation2008). These strategies are based in a spatial logic which suggests that territorial security is best maintained through the creation of buffer zones to stop threatening mobilities long before they arrive at the border (Lahav and Guiraudon Citation2000; Mountz Citation2011a).

Concurrently, there has been a rise in interior spaces of border control (e.g. Coleman Citation2007a; Inda Citation2006; Martin Citation2012). Migrant status, for example, is increasingly policed in workplaces and in a range of other everyday spaces (e.g. Tervonen, Pellander, and Yuval-Davis Citation2018; Vaughan-Williams Citation2008; Warren and Mavroudi Citation2011; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018). Access gained to a territory thus no longer equals inclusion in a political space. Instead, as Louise Amoore (Citation2006, 338) has argued, ‘the crossing of a physical territorial border is only one border crossing in a limitless series of journeys that traverse and inscribe the boundaries of safe/dangerous, civil/uncivil, legitimate traveller/illegal migrant’. As such, borders continue to divide migrants at railway stations or on city streets, and in the hospital, the office or the neighbourhood, and many of those on the inside are now living as though they were part of the outside.

The increasing use of so-called smart border and risk management technologies, including biometrics, data-mining and radio frequency identification, have served to further complicate the relationship between the internal and external spaces of borders. It is now widely suggested that these technologies have effectively transformed human bodies into carriers of borders (e.g. Aas Citation2006; Amoore Citation2006; van der Ploeg Citation2003). When the information needed to enforce borders, including information about identity, legal status or the degree of risk that a certain individual represents, is carried in bodies, border control is no longer limited to specific entry points into nation-state territories but may be carried out wherever ‘risky’ bodies appear, within as well as beyond state territories.

The topological figure of the Möbius strip has frequently been invoked to account for the ways in which contemporary bordering practices challenge the conventional understanding of the relationship between state, border and territory, for example, by merging the inside and outside spaces of borders (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Bigo Citation2001; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2012) or by producing different configurations of presence and absence (see, e.g. Axelsson and Hedberg Citation2018; Sigvardsdotter Citation2013). Indeed, when traced along its length, the twisted, apparently two-sided figure of the Möbius strip reveals itself to be a single non-orientable surface. Didier Bigo (Citation2001, 115) has consequently argued that from the migrant perspective, it becomes more or less impossible to know ‘on which face of the strip one is located’, whether one is included or indeed excluded in a political space despite appearing, on the face of it, to have gained access. Other topological figures that have been used to account for the changing shape of contemporary political borders include, for example, the Agambenian camp (e.g. Johnson Citation2013; Mountz Citation2011a; Papadopoulos, Stephenson, and Tsianos Citation2008), the Klein bottle (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Bigo Citation2001) and the spatial fold (Allen Citation2016; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2012). With regard to the last example, John Allen (Citation2016, 147) has suggested that ‘the folding of space’ has enabled states ‘to reach into their own territories, as well as beyond them, drawing migrant populations within reach of their authority and control, or displacing responsibility for them by placing access to the public sphere out of reach’. Thus, for Allen, the externalization and internalization of borders are less about an extensive spatiality, about the movement of border controls outwards or inwards across a flat surface, and more about the intensity of relationships which enables, for example, governments to exercise their powers to reach into the territories of other states or to place legal rights beyond reach.

Contemporary borders thus exhibit a complex relationship to territories, and it is increasingly difficult to determine what a border is, where the inside of a political space ends and the outside begins, and what crossing a border actually means. As such, bordering practices both challenge and reinforce the notion of bounded spaces (Paasi Citation2022). Bordering practices challenge the notion of bounded spaces because the merging of the inside and outside spaces of borders, the ways that governments are able to reach into and beyond their territories in order to enforce their borders increasingly call into question the traditional, cylindrical model of sovereign territoriality. They reinforce the notion of bounded spaces because at the centre of these spatially ambiguous bordering practices is an inert desire for borders, an understanding that it is necessary to (selectively) control global flows in order to protect internal spaces.

However, the changing shape of contemporary borders is not just spatial in the making. A small but growing body of literature suggests that states also rely on time and temporality in the regulation of cross-border movements and access to rights (Donnan, Hurd, and Leutloff-Grandits Citation2017; Little Citation2015; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013; Papadopoulos, Stephenson, and Tsianos Citation2008; Sontowski Citation2018; Tazzioli Citation2018). For example, risk management technologies reconfigure borders in a temporal sense by drawing on past events to produce risk profiles in the present in order to prevent terrorist attacks from taking place in the future (e.g. Amoore Citation2009). Likewise, the promise of a future in a given territory, which is inscribed into many immigration policies appropriates the present in a variety of ways (Axelsson, Malmberg, and Zhang Citation2017; Drangsland Citation2020b). Contemporary bordering practices also shape international mobility and migration by projecting borders backwards and forwards in time, to moments before and after the border. Simon Sontowski (Citation2018), for example, has suggested that by introducing pre-vetting and pre-screening of passengers, the EU’s smart border scheme determines who is eligible to enter the Schengen area in advance and, in so doing, projects the timing of border control to a point before the individual reaches the territorial border. Similarly, a growing body of work shows that borders continue to play a role in migrants’ lives long after they have gained access to a particular territory, shaping their access to the labour market, welfare and other rights as well as their long-term incorporation (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Anderson Citation2010; Axelsson Citation2017; Cwerner Citation2001; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013; Robertson Citation2014; Warren and Mavroudi Citation2011).

Borders are also increasingly designed to regulate the pace of international mobility and migration rather than to block mobility and migration entirely. In Escape Routes, Dimitris Papadopoulos, Niamh Stephenson, and Vassilis Tsianos (Citation2008) argue that the purpose of the detention centres (or camps in their terminology) that have been constructed around the edges of the EU is not to stop migration. They instead suggest that ‘[t]he main function of camps is to impose a regime of temporal control on the wild and uncontrollable […] movements of the transmigrants’ (199); indeed, to slow down or temporarily freeze migratory movements. Drawing their inspiration from Paul Virilio’s understanding of the relationship between speed and politics, Papadopoulos et al. urge a re-think of detention camps as spatialized attempts to temporarily regulate mobility through the suspension of time. Camps, they argue, are better understood as speed boxes that merely serve to slow down the pace of migration yet still intend to insert migrants into the global regime of labour. As such, they suggest ‘[d]ecelerated circulation is a means of regulating migration not through space but through time’ (198). Similar arguments about the role of time in the regulation of international migration have been made in the rapidly growing literature on waiting which has demonstrated how state authorities use delays, disruptions and deferrals to appropriate migrants’ time in a variety of ways (e.g. Andersson Citation2014; Axelsson, Malmberg, and Zhang Citation2017; Drangsland Citation2020a; Griffiths Citation2014; Ilcan Citation2020; Mountz Citation2011b).

Others have highlighted how the acceleration of cross-border movements is just as much a part of the regulation of international mobility and migration as its deceleration, in particular when it comes to denial of access to the asylum channel, deportations and removals. Basing his argument in an analysis of the United Kingdom’s asylum process, Saulo Cwerner (Citation2004) argued that speed has become a marker of a successful immigration system. Quick decision-making has been facilitated by the establishment of deadlines and time limits with which asylum seekers have to comply. Relatedly, Martina Tazzioli (Citation2018) argued that the EU’s asylum system relies on a combination of an infrastructure of detention and accelerated procedures for identification and selection. Consequently, it is determined within hours of arrival on the EU’s shores who will be allowed to claim asylum and who will be expelled. Tazzioli (Citation2018, 17) consequently claimed that the EU’s border regime is characterized by ‘a split temporality of control’ which uses incarceration to disrupt and slow down migratory movements and at the same time, hastens the channels of deportation. The temporal ambiguity of migratory processes in which periods of waiting and feeling stuck are cut through with moments of acceleration also plays a central role in the work of for example Melanie Griffiths (Citation2014) and John Clayton and Tom Vickers (Citation2019) on the UK’s asylum system.

Time, then, is a powerful tool in the regulation of international mobility and migration. However, simply shifting the analytical attention from the spatial to the temporal dimensions of borders is not enough to move the debate about contemporary borders forward (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019). Instead, it might be necessary to consider how space and time work through each other to regulate the pace of cross-border movements and shape access to the internal spaces of borders in increasingly ambiguous and paradoxical ways.

What might an analysis of the changing shape of contemporary borders be like which takes seriously the relationship between the temporal and the spatial? In the next section, I engage with geographical literature that has sought to overcome the spatial–temporal divide in the analysis of social science phenomena in order to begin to outline some specific ways in which the temporal is irrevocably bound with the spatial constitution of borders.

Timespace geographies

The ways in which social and cultural phenomena unfold in space and time has long been a key concern in human geography (for an overview, see, e.g. Merriman Citation2012). For decades, concepts and approaches such as time geography (Hägerstrand Citation1970), space‒time (Massey Citation1994), plastic time‒space (Thrift Citation1977), time‒space convergence (Janelle Citation1969) and Harvey’s (Citation1990) notion of time‒space compression have asserted the importance of integrating spatial and temporal analysis, to move away from prioritizing either space or time in geographical analysis and to instead hold the two together.

Despite being based in different philosophical traditions, several of these scholars share an interest in the relationship between speed and distance. Swedish geographer Hägerstrand (Citation1970, Citation1973, Citation1975), for example, developed a methodology for graphic notation of sequential movements in space‒time and focused attention on how individuals occupy time and space. Human activities, Hägerstrand argued, are shaped by spatial and temporal constraints, with time and space acting as limited resources that individuals have to navigate in order to realize their projects. Consequently, there are only a certain number of locations that individuals can reach and only a certain distance they can travel given their speed of movement and the amount of time they have at their disposal.

By contrast, the notion of time–space convergence was developed to account for the decline in travel time between locations over time. The development of transportation and telecommunication technologies and related technological and social innovations have served to radically shorten the distance between places in relative terms, making them appear closer than they once were (Janelle Citation1969). As Stephen Kern (Citation1983) famously argued, wave upon wave of innovation has reconfigured our perception of proximity and distance. The telegraph, the telephone, the car and the aeroplane, as well as, photography and the cinema have made it ‘possible, in a sense, to be in two places at once’ (Kern Citation1983, 69). These innovations have served to blur the conventional understanding of near and far by enabling people to learn about distant places and to interact with one another across distance, thereby rendering less meaningful the traditional views of distance and absolute space found in the work of scholars such as Hägerstrand. Relatedly, David Harvey (Citation1990) has linked time‒space convergence to the history of capitalism, arguing that the ‘annihilation of space by time’ is fundamental to the operation of capitalism. Capitalist societies are consequently typified by a significant acceleration of the pace of life which dramatically compresses geographical and social distances to the extent that the world appears to collapse upon us. For Harvey, just as for Janelle and Kern, space is not an absolute surface and time is not necessarily linear. In Harvey’s work, ‘time and space loop around one another, fold in upon themselves and twist and turn in complex, contingent ways’ (Warf Citation2011, 145).

Taking time‒space compression as their point of departure, May and Thrift (Citation2001) called a decade later for increased attention by geographers to the multiple, multidimensional and uneven ways in which time is irrevocably bound up with the spatial constitution of society. TimeSpace (which is May and Thrift’s preferred term), they argued, is not just characterized by a collapse of distance through an acceleration of the pace of life. Instead, they drew on thinkers such as Latour, Bergson, Deleuze and Lefebvre to qualify the standard narratives of time‒space compression. Distances between places, May and Thrift consequently argued, are simultaneously contracting and expanding and time is simultaneously speeding up and slowing down. Moreover, there are other qualities to TimeSpace than the simple acceleration of time and the collapse of distance. Indeed, events are being reordered in ways that challenge linear conceptions of time and lend ‘space a radically discontinuous and fragmented quality’ (May and Thrift Citation2001, 11). Both time and space, then, are amenable to flow and discontinuity which, in turn, complicate what is accessible and inaccessible, near and far, within reach and out of reach and amplify ‘the presence of the now’ while remaking what ‘counts as past and future, here and there’ (37), and they do so differently in different places and at different times.

The understanding that events cannot be split into their temporal and spatial qualities is not without its critics. Peter Merriman (Citation2012), for example, has raised concern about what he calls an ‘obsession’ among human geographers with time‒space and space‒time. Instead, Merriman foregrounds movement, arguing that it cannot ‘be reduced to instants in space and moments in time’ (21). The unfolding of events, Merriman continues, ‘is manifested not in multiple socialized neo-Euclidean or neo-Cartesian space-times, but rather in the eruption of movement-spaces, rhythmic-movements, energetic space-times, movement-affect-space-times, etc’ (21‒22). Consequently, movement–spaces rather than time–spaces should be at the centre of geographical analysis. By contrast, Ben Page, Anastasia Christou and Elizabeth Mavroudi (Citation2017) assert that the solution is to return to time and the temporal, to prioritize time over space and to acknowledge the difference between time and space in the analysis of international migration, something which the notion of time–space, in their view, obscures.

It would consequently appear that thinking time and space together has lost some of its momentum in human geography. However, when it comes to understanding contemporary bordering processes, I would argue that there is still is merit in considering how space and time work through each other to change the shape of political borders, as well as, what it means to gain access to and move in and out of a political community. Indeed, even if few critical border scholars have explicitly demonstrated how space and time are inextricably linked in contemporary bordering processes, it is evident that time and temporality are not simply something which can replace or be added onto an already spatial analysis of borders. For example, in her work on virtual or biometric borders, Amoore (Citation2011) has suggested that smart border technologies simultaneously stretch borders in space and time. In this view, borders are ‘exported’ through space and time to stop the international mobility of people who are considered to be a threat to those on the inside ‘“prior to arrival”, demarcating lines long before a recognizable border is reached’ (63). Equally, the decision by the Australian government in 2001 to retroactively declare parts of its territory no longer part of Australia in order to prevent asylum claims to be made in the present (Mountz Citation2011a; Weber Citation2006) represents one of the more extreme examples of the construction of paradoxical border timespaces. Many migrants also find themselves in increasingly paradoxical positions in which they are partly on the inside partly on the outside of legal rights and protections (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019; Könönen Citation2018; Mezzadra and Neilson Citation2013; Rigo Citation2011) or are partly present, partly absent in a political space (Axelsson and Hedberg Citation2018; Sigvardsdotter Citation2013) because of the ways in which speed, rhythm and duration selectively combine. Thus, time and temporality rework the spatialities of borders and vice versa in quite specific ways which are not fully understood if borders are split into their spatial or temporal qualities (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019).

In the rest of the paper, I draw on some of the ideas about the relationship between speed and distance, flow and discontinuity (in both the temporal and spatial sense) and about the fragmented quality of timespaces (which is the term I have opted to use to indicate that time and space are inextricably bound up with each other) to discuss the complex temporal and spatial entanglements involved in contemporary bordering processes. Distance is here understood not as a metric but in terms of connectivity and discontinuity, of access to the internal spaces of borders, to territories and labour markets, and to cross-border mobility itself. This access is mediated through time by altering the speed of migrants’ cross-border movements. For the migrant whose cross-border movements are accelerated, access to the internal space of borders is more or less immediate, while access for the migrant whose movements are decelerated is suspended or even placed beyond reach. Taking inspiration from May and Thrift’s call for attention to non-linear time, I also introduce rhythm as another temporal device which selectively gives rise to moments of movement and enforced stillness for different people for different lengths of time (on migration, circularity and rhythm see, e.g. Castles Citation2006; Conway, Potter, and Bernard Citation2009; Griffiths, Rogers, and Anderson Citation2013; Reid-Musson Citation2018).

The following account is based on insights from work on the regulation of labour migration, including empirical work that I have conducted over the past decade on borders and labour migration in Sweden. The latter includes documentary analysis covering the period 2008–2018 and ten semi-structured interviews with staff at the government body responsible for implementing immigration law in Sweden: the Swedish Migration Agency. In order to give voice to some of the migrants whose lives are cut through by spatially and temporally complex borders, I also draw on insights from 30 semi-structured interviews with information technology professionals conducted in 2015 and 2018‒2019 who migrated to Sweden from a wide variety of countries outside the European Economic Area. Lastly, I discuss what this particular way of thinking time and space together has to contribute towards understanding contemporary bordering practices.

Calibrating cross-border movements

In order to begin to outline how time and space work through each other to give shape to international labour migration, I draw attention in this section to two ways in which governments shape labour migrants’ access to territories and labour markets and to international mobility itself by altering the speed and rhythm of their movements. Put another way, labour migrants find their access to international mobility, territories and labour markets to be selectively drawn within or placed beyond reach because of the ways in which speed and rhythm selectively combine. In such instances, time does not act as a supplement to space and vice versa, but rather time and space combine to distort access to cross-border mobility and the inside space of borders. In what follows, I first consider how the acceleration of migrants’ cross-border movements serves to connect and disconnect places and shape labour migrants’ access to the internal spaces of borders in both linear and rhythmic ways. After that, I shift the focus to how contemporary borders shape international mobility and access to territories and labour markets by slowing down the movements of labour migrants, by delaying entries and by introducing moments of enforced stillness into otherwise mobile lives. In both instances, a focus on the ways in which speed and rhythm work through distance, connectivity and immobility opens up a different way of conceptualizing how contemporary bordering practices selectively shape access to the internal spaces of borders and to international mobility itself.

Expedited crossings and departures

The world of business travellers is full of examples of expedited crossings. The international mobility of highly valued professionals is accelerated through a variety of so-called smart border schemes which, in theory at least, enable them to move across borders at a higher speed than other travellers (Adey Citation2004; Sontowski Citation2018; Sparke Citation2006). Smart border schemes rely on accelerated procedures for identification and selection of migrants and project borders outwards in space and time to the country of departure and before the border, while enrolling those on the outside as if they already were part of the inside. In a similar fashion, some governments have sought to gain a competitive advantage by offering the highly skilled fast-tracked admission processes and a comprehensive set of rights upon arrival (e.g. Axelsson and Pettersson Citation2021; Boeri Citation2012; Chaloff and Lemaitre Citation2009; Shachar Citation2006). Nandita Sharma (Citation2005, 4) has consequently argued that for highly valued migrants, borders are ‘mere formalities’; something they traverse at speed, and their inclusion may be full and immediate.

At times, the pace at which external and internal spaces are connected and the distance between them is compressed is accelerated to the extent that the mind struggles to keep up. One highly skilled professional who participated in a study about Sweden’s labour immigration policies said:

I was googling on the Swedish website, the wait list for a work permit is like eleven months or something like that […] [T]hat’s kind of crazy, I accept a job, then I wait a year. But they [the Swedish employer] were like, no, no, [company name] has a special … some kind of A-level employer or whatever […] Four days later they [the Swedish employer] were like, we have your work permit, you’re all set and ready to come over here and I’m like, all right, I am not mentally ready to go to Sweden. Me getting my work permit triggered an entire series of panic attacks. I was almost comatosed on my couch, like, what have I done, why am I going to a place I’ve never been to. […] And I arrived on a Sunday and I rolled into work on a Monday so … it was just like, right you’re in Sweden, here’s your apartment, here’s your keys, here’s your work card, off and go. (IT-professional #3)

The IT professional is referring to a nationwide fast track for work permit applications (sw. certifieringssystemet) which was established in the late 2000s and early 2010s in order to speed up work permit administration. A limited number of employers, predominantly in the IT industry, and immigration service providers who specialized in preparing work permit applications on behalf of their corporate clients were given a guarantee that a decision on their applications would be delivered within a certain timeframe in exchange for performing some of the administrative tasks of the Swedish work permit system (Axelsson and Pettersson Citation2021).

However, fast-tracked admission is not limited to the highly skilled. Due to the demand for transient, low-skilled workforces which arrive just-in-time and depart at the end of their short-term contracts, there has been a rise in temporary migration programmes (e.g. Castles Citation2006; Lenard and Straehle Citation2012; Ruhs Citation2006). Consequently, some lower-skilled workers also circulate in and out of territories at an accelerated pace. This is the case in Sweden, for example, where work permit applications for migrants from Thailand who work in Sweden’s forest berry industry for a few months every year are fast-tracked in order to ensure that the workers arrive in time for the season. However, in contrast to the highly-skilled, there is no fast-tracked inclusion for these workers. Instead, return is part of their arrival. Due to the fact that the right to remain as well as access to welfare and other social rights are commonly granted only after a certain length of time has been spent working on the inside (e.g. Anderson Citation2010; Rajkumar et al. Citation2012), workers such as these are indefinitely excluded from claiming long-term inclusion (Allen and Axelsson Citation2019). The same holds true for many skilled migrants, predominantly in the information technology industry, who are speedily transferred between branches within multinational organizations for short-term, pre-defined periods of time.

Other migrant departures are similarly expedited. A rejected application for a renewed work permit, for example, is quickly followed by an order to leave the country within a short space of time. As I conducted interviews with highly skilled professionals, I found that many of their trajectories contradicted the idea that borders for the highly skilled were mere formalities. Instead, borders were very much present in their lives, and the respondents expressed fear of being forced to leave Sweden with little notice while some had been deported from the country (Axelsson Citation2017). One of them said:

So, they [the Swedish Migration Agency] said, you have to leave the country, you can’t stay in Sweden anymore, you just send us your tickets within two weeks and just give us green signal that you are out of the country. I was like surprised, I have a job here [in Sweden]. You are playing with my future actually. [—] I went to [country of origin] and then apply again from there but that was really hectic for me, that’s really shocking that … I had no idea either shall I come back or not. [—] We have served four years for this country and there’s no benefit, no value for us. It’s just like you just use them and throw them out [laughs]. So, this is the feeling I had that time, I was really frustrated. [—] There is no safe space […] for us immigrants. (IT professional #7)

Deportability and the insecurity of presence that comes with it (De Genova Citation2002) are consequently not reserved for undocumented or unauthorized migrants. Currently, migrant workers of all shades are subject to visa conditions and security laws which can quickly transform them into deportable subjects (e.g. Basok, Bélanger, and Rivas Citation2014; Rajkumar et al. Citation2012; Xiang Citation2007).

The acceleration of cross-border movements, the removal of temporal frictions to mobility is thus a central part of how borders have changed shape in recent years to blur the line between a territory’s internal and external spaces. Access to the inside can be so immediate that, in a temporal sense, the distance between countries of origin and destination almost ceases to exist. However, access might also be withdrawn in an accelerated manner, and for workers on short-term work visas, departures are as expedited as arrivals. This also suggests that there is another temporal device at play in contemporary bordering practices, one which challenges linear conceptions of time by inducing certain rhythms of international mobility. A rising number of migrants are currently part of a globally circulating workforce which is selectively, and often repetitively, given access to the inside spaces of borders in an accelerated fashion to meet demands for their labour. These workers circulate between countries of origin and destination for pre-defined, short periods of time.

Delayed entries, halted mobilities

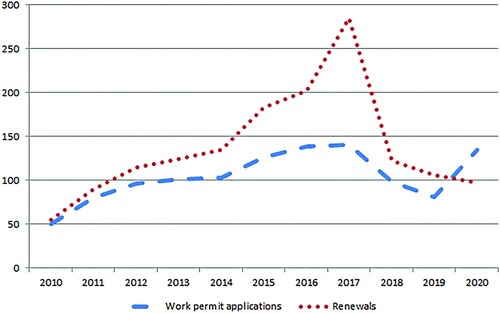

Borders also intervene in migrant mobility by slowing it down. In Sweden, migrant labour which moves outside the expedited channels of border crossing can wait for long periods of time before being granted admission. The dashed line in the graph in shows the average time to a decision on a work permit application in Sweden, measured in working days. However, the average number of working days to a decision presented in the figure conceals significant inequalities between migrants who are able to access a fast track and migrants who move through the regular channels of labour migration. For example, in 2017, the average processing time for work permit applications in the fast tracks was 36 working days. For applicants moving outside these expedited channels of border crossing the average processing time was 199 working days (Axelsson Citation2018a). Averages also hide differences betweein individual applicants. In reality, this means that some labour migrants wait for extended periods of time for a decision on their applications, in some cases over a year. While they wait for permission to enter, they remain in countries of departure for unknown periods of time in a condition of state-induced waiting. Waiting, as I have argued elsewhere, is a central component of immigration administration and bureaucracy (Axelsson Citation2018b; see also Auyero Citation2012; Olson Citation2015) which might be the result of a deliberate state strategy (see e.g. Sellerberg Citation2008) or simply the inadvertent outcome of limited budgets, inefficient administrative procedures, etc. Of importance to the argument pursued here, waiting serves to insert distance between inside and outside spaces through the technology of time. Waiting projects migrants’ entries into the future and if the wait becomes too long, it can even place entry out of reach. One highly skilled professional who waited 14 months in his country of origin for a decision on his application noted:

It’s just the waiting, too long time for waiting. So originally on the Migration Board website it says about ten months and I think I submit everything [all the documents needed for a decision to be made] at the very beginning and then nothing happened so I wrote some mails to them. The answer is basically, you have to be patient. [—] Actually, my wife was quite worried about it and she wanted me to buy an apartment in our hometown instead, a good place to live and close to schools. [—] So, you are actually preparing for the second option [staying where you are]. I was about to buy apartment then I think maybe I should write email just to check the status. Then I got approval. (IT-professional #14)

However, the distinction between inside and outside, before and after the border, is not always clear-cut, especially for highly skilled professionals whose jobs might require them to be present on the inside despite not yet having gained long-term admission. Many highly skilled professionals, for example, spoke about how they had repeatedly travelled back and forth between Sweden and their countries of origin on short-term business visas to participate in meetings, perform short-term work on client sites, etc. while they waited for a decision on their work permit applications. These migrants’ lives consequently oscillated between experiences of expedited crossings in the short-term and suspension of their long-term migration. By contrast, the strategy of ‘benching’ – that is, placing workers ‘on hold’ once they have reached the destination where their temporary work visa applies – temporarily suspends the entry of highly skilled professionals into labour markets while placing their lives on hold (Xiang Citation2007). Thus, benching produces a different rhythm of international mobility in which expedited crossings are followed by delayed access to labour markets.

Others who have gained entry might have their freedom of movement taken away. Labour migrants in Sweden, for example, might have their freedom of movement temporarily taken away for periods during which their visas have to be renewed. During these periods in which they lack the documents they need to return if they leave Sweden, they are confined to the space within, as represented by the dotted line in . Many of the highly skilled professionals I interviewed talked about the uncertainty that came with not knowing the outcome of their applications for extended periods of time; about families being separated when decisions on family members’ applications were delayed; about feeling stranded or stuck and about their frustration when repeatedly being told to ‘wait’, ‘be patient’ or that the Swedish Migration Agency ‘didn’t know anything’ about the status of their applications (see Maury Citation2022 for a similar discussion). One highly skilled professional who waited 18 months for a renewal said:

I was kind of stuck here, it was bad feeling actually for me. Yes, I like the country but … I don’t know, maybe that I couldn’t go out, I couldn’t go. Because this is Europe, you know, the best thing is you just travel. I really, really like travelling. [–] But I couldn’t go anywhere and after I get the work my [new] colleagues they had vacations, going there, the Hawaii, Bahamas [laughs]. Don’t tell me anything, please, be quiet. Tell that you were staying at home here. So, it got me homesick and depressed to be honest. (IT professional #9)

The deceleration of cross-border movements consequently works to suspend access to territories and labour markets for those on the outside. Thus, if the acceleration of mobility served to connect external and internal spaces by collapsing the distance between them, deceleration here rather inserts distance between insides and outsides, countries of origin and destination through time. For some of the migrants who wait on the outside for an opportunity to be included in the long-term, the distance between the country of origin and destination is momentarily collapsed through moments of accelerated short-term mobility. Concurrently, the slowness of immigration administrations serves to confine some of the labour migrants who have gained entry to the space within, completely halting their cross-border mobility for undefined periods of time.

Conclusion: border timespaces

By drawing attention to the ways in which time and temporality help to shape what it means to move in and out of a political community, to complicate what is near and far, accessible and inaccessible, I have tried to not only show that labour migrants are given differential access to the internal spaces of borders and to international mobility itself but also that time and space are irrevocably bound together in the production of such differential access. If the relationship between the internal and external spaces of borders is shaped by a temporal dimension, one which selectively alters the distance between and connects and disconnects countries of origin and destination through the medium of time, then any understanding of contemporary borders has to go beyond simply adding a temporal dimension to an already spatial analysis of borders. Instead, as I have suggested, contemporary borders can be usefully understood as devices which selectively contract and expand the distance between internal and external spaces by altering the speed of migrants’ movements. Governments compress the distance between countries of origin and destination by accelerating the movements of some labour migrants, by providing immediate access to the internal spaces of borders and by connecting the internal and external spaces of borders to the extent that they almost appear to collapse into each other. Conversely, states expand the distance between external and internal spaces and produce discontinuities through the medium of time by intentionally or inadvertently slowing down migratory movements. In these instances, access to the internal spaces of borders is made distant, is pushed into the future, at times so far that international mobility is placed firmly beyond reach.

Borders also intervene in international labour migration by inducing certain rhythms of cross-border movement. Here, time and space work through each other to mobilize and immobilize migrant labour, to selectively give rise to moments of movement and of enforced stillness for different lengths of time. Certain migrants are given temporary access to territories and specific segments of the labour market on a recurring basis. For others, moments of enforced stillness are temporarily incorporated into otherwise mobile lives.

To paraphrase mobilities scholar Tim Cresswell (Citation2010), this suggests that international mobility does not happen evenly over a continuous surface or in a uniform timespace. Instead, a variety of ambiguous migrant statuses and flows and discontinuities are shaped by accelerated and decelerated experiences of mobility and by repeated or disrupted movements in and out of territories. One person’s expedited crossing is consequently another person’s delayed entry, some people move while others are fixed in place for shorter or longer periods of time and the life of a single person might oscillate between moments of movement and enforced stillness. Thus, the picture that emerges is less that of singular border timespace that reshapes borders according to a generalized pattern and more of a variety of fragmented timespaces, of uneven conduits of international mobility and access constructed through particular sets of temporal and spatial distortions of border relationships.

Moreover, the ways in which borders mobilize and immobilize migrant labour by selectively bringing time and space to bear on each other are forever shifting and changing; new timespaces take shape and existing ones appear in new shapes. I consequently want to end with a short reflection on the ephemeral nature of any border timespace, using recent amendments to Sweden’s immigration legislation as an example (Government Bill Citation2020/21:191). The new immigration law was primarily designed to manage the so-called refugee crisis, but it in reality has an impact on access to Swedish territory and labour market for all migrants who lack permanent status. Thus, the new immigration law uses time and temporality to selectively exclude from settlement all migrants on short-term contracts.

Several years before these amendments to Sweden’s immigration law, a highly skilled migrant I interviewed reflected on the shifting nature of borders, perhaps foreseeing not this particular change to immigration law but demonstrating an acute awareness of the very real possibility that the criteria of selection might change over time, retroactively withdrawing access to Swedish territory and its labour market:

I think in settlement, just planning, I can’t plan. Sometimes I don’t feel secure, that’s all. Sometimes you think, do I need a plan B? [—] [I]f the political parties change I don’t know what’s going to come up with the new rules, it might come, the four years [that you now have to work in Sweden in order to become eligible to apply for permanent status] might be changed to ten years or I don’t know […] So you can’t plan. (IT professional #6)

Time, then, accentuates the lack of a clear dividing line between the internal and external spaces of borders and between inclusion and exclusion, and if it is difficult to discern who is eligible for access in the present, it is even more difficult to know how borders might change shape in the future. Just as there are no unequivocal lines between internal and external spaces in the present, there are also no discrete temporal intervals that separate the times before and after the border in the future; there are just continuous timespaces which order international mobility and migration as time and space loop through each other in complex, contingent ways. At the same time, the intention is not to overstate the relational or fluid nature of border timespaces, of distance, connectivity, speed and rhythm. As Alec Murphy (Citation2022) and Martin Jones (Citation2022) argue in their contributions to this special issue, not only is there a sticky or plastic quality to bounded spaces, territories and regions but societies are also characterized by an inert desire for borders that cannot be overlooked. This is especially true if the purpose of an analysis of borders, as suggested by Anssi Paasi (Citation2022), is to draw attention to and challenge the numerous inequalities they produce. Thus, it is not the desire for bounded spaces that is ephemeral but the many ways in which borders are enacted and the many ambiguous positions they produce which place migrants partly on the inside, partly on the outside, as partly present, partly absent in a political space that is continuously shifting and changing. To move the understanding of contemporary borders forward and to call their divisive effects into question, the challenge appears to be to continue to explore what other complex entanglements are at play between the temporal and the spatial in contemporary bordering processes.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the respondents for participating in this study. I would also like to thank Anssi Paasi for inviting me to contribute to this special issue. Thanks also go out to colleagues with whom I have collaborated with over the years on the topic of labour migration and borders including John Allen at The Open University and Charlotta Hedberg at Umeå University, whose constructive comments on my work over the years are bound to have shaped some of the thoughts presented in this paper. The author would also like to acknowledge that funding to cover the costs of fieldwork was gratefully received from Helge Ax:son Johnsons Stiftelse and Kungliga Vetenskapsakademiens fonder. The author alone is responsible for the contents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aas, K. F. 2006. ““The Body Does Not Lie”: Identity, Risk and Trust in Technoculture.” Crime, Media, Culture 2 (2): 143–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659006065401.

- Adey, P. 2004. “Surveillance at the Airport: Surveilling Mobility/Mobilising Surveillance.” Environment and Planning A 36 (8): 1365–1380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a36159.

- Allen, J. 2016. Topologies of Power: Beyond Territory and Networks. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Allen, J., and L. Axelsson. 2019. “Border Topologies: The Time-Spaces of Labour Migrant Regulation.” Political Geography 72: 116–123.

- Amoore, L. 2006. “Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror.” Political Geography 25 (3): 336–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.001.

- Amoore, L. 2009. “Lines of Sight: On the Visualization of Unknown Futures.” Citizenship Studies 13 (1): 17–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020802586628.

- Amoore, L. 2011. “On the Line: Writing the Geography of the Virtual Border.” Political Geography 30 (2): 63–64.

- Amoore, L., and M. de Goede. 2008. “Transactions After 9/11: The Banal Face of the Preemptive Strike.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33 (2): 173–185.

- Anderson, B. 2010. “Migration, Immigration Controls and the Fashioning of Precarious Workers.” Work, Employment & Society 24 (2): 300–317.

- Andersson, R. 2014. “Time and the Migrant Other: European Border Controls and the Temporal Economics of Illegality.” American Anthropologist 116 (4): 795–809. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12148.

- Auyero, J. 2012. Patients of the State: The Politics of Waiting in Argentina. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Axelsson, L. 2013. “Temporalizing the Border.” Dialogues in Human Geography 3 (3): 324–326.

- Axelsson, L. 2017. “Living Within Temporally Thick Borders: IT Professionals Experiences of Swedish Immigration Policy and Practice.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 43 (6): 974–990. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1200966.

- Axelsson, L. 2018a. “Bordering on the Temporal: Fast and Slow Routes Through Sweden’s Labour Immigration System”. Paper presented at the Nordic Migration Research Conference, Linköping University, August 15–17.

- Axelsson, L. 2018b. “Om väntan: IT-företags och dataspecialisters erfarenheter av svensk migrationspolitik och praktik.” In Högutbildade migranter i Sverige, edited by M. Povrzanović Frykman and M. Öhlander, 71–85. Arkiv förlag & tidskrift: Lund.

- Axelsson, L., and C. Hedberg. 2018. “Emerging Topologies of Transnational Employment: “Posting” Thai Workers in Sweden’s Wild Berry Industry Beyond Regulatory Reach.” Geoforum 89: 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.01.003.

- Axelsson, L., B. Malmberg, and Q. Zhang. 2017. “On Waiting, Work-Time and Imagined Futures: Theorising Temporal Precariousness Among Chinese Chefs in Sweden’s Restaurant Industry.” Geoforum 78: 169–178.

- Axelsson, L., and N. Pettersson. 2021. “Spatial Shifts in Migration Governance: Public-Private Alliances in Swedish Immigration Administration.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 39 (7): 1529–1546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544211043523.

- Balibar, É.. 2002. Politics and the Other Scene. Phronesis. London: Verso.

- Basok, T., D. Bélanger, and E. Rivas. 2014. “Reproducing Deportability: Migrant Agricultural Workers in South-Western Ontario.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (9): 1394–1413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.849566.

- Bialasiewicz, L. 2012. “Off-Shoring and Out-Sourcing the Borders of Europe: Libya and EU Border Work in the Mediterranean.” Geopolitics 17 (4): 843–866.

- Bigo, D. 2001. “The Möbius Ribbon of Internal and External Security(Ies).” In Identities, Borders, Orders: Rethinking International Relations Theory, edited by M. Albert, D. Jacobson and Y. Lapid, 91–115. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Boeri, T. 2012. Brain Drain and Brain Gain: The Global Competition to Attract High-Skilled Migrants. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199654826.001.0001.

- Castles, S. 2006. “Guestworkers in Europe: A Resurrection?” International Migration Review 40 (4): 741–766.

- Chaloff, J., and G. Lemaitre. 2009. Managing Highly-Skilled Labour Migration: A Comparative Analysis of Migration Policies and Challenges in OECD Countries. OECD Publishing. http://ideas.repec.org/p/oec/elsaab/79-en.html.

- Clayton, J., and T. Vickers. 2019. “Temporal Tensions: European Union Citizen Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees Navigating Dominant Temporalities of Work in England.” Time & Society 28 (8): 1464–1488. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X18778466.

- Coleman, M. 2007a. “Immigration Geopolitics Beyond the Mexico–US Border.” Antipode 39 (1): 54–76.

- Coleman, M. 2007b. “A Geopolitics of Engagement: Neoliberalism, the War on Terrorism, and the Reconfiguration of US Immigration Enforcement.” Geopolitics 12 (4): 607–634. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040701546087.

- Conway, D., R. B. Potter, and G. St. Bernard. 2009. “Repetitive Visiting as a Pre-Return Transnational Strategy Among Youthful Trinidadian Returnees.” Mobilities 4 (2): 249–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100902906707.

- Cresswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407.

- Cwerner, S. B. 2001. “The Times of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (1): 7–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830125283.

- Cwerner, S. B. 2004. “Faster, Faster and Faster: The Time Politics of Asylum in the UK.” Time & Society 13 (1): 71–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X04040747.

- De Genova, N. P. 2002. “Migrant “Illegality” and Deportability in Everyday Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 419–447.

- Donnan, H., M. Hurd, and C. Leutloff-Grandits. 2017. Migrating Borders and Moving Times: Temporality and the Crossing of Borders in Europe.

- Drangsland, K. A. 2020a. “Waiting as a Redemptive State: The “Lampedusa in Hamburg” and the Offer from the Hamburg Government.” Time & Society 29 (2): 318–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X19890989.

- Drangsland, K. A. 2020b. “Bordering Through Recalibration: Exploring the Temporality of the German “Ausbildungsduldung”.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 38 (6): 1128–1145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420915611.

- Government Bill. 2020/21:191. Ändrade regler i utlänningslagen. https://www.regeringen.se/4994e4/contentassets/f3c5d42a0d4f4684b21dc8885dceb589/andrade-regler-i-utlanningslagen-prop.-202021191.

- Griffiths, M. B. E. 2014. “Out of Time: The Temporal Uncertainties of Refused Asylum Seekers and Immigration Detainees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.907737.

- Griffiths, M. B. E., A. Rogers, and B. Anderson. 2013. Migration, Time and Temporalities: Review and Prospect. COMPAS Research Resources Paper. Oxford: Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, www.compas.ox.ac.Uk/Publications/Research-Resources. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/fileadmin/files/Publications/Research_Resources/Citizenship/Report_-_Migration_Time_and_Temporalities_FINAL.pdf.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1970. “What About People in Regional Science?” Papers of the Regional Science Association 24: 7–21.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1973. “The Domain in Human Geography.” In Directions in Geography, edited by Richard J. Chorley, 67–87. London: Methuen.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1975. “Space, Time and Human Conditions.” In Dynamic Allocation of Urban Space, edited by A. Karlqvist, L. Lundqvist and F. Snickars, 3–14. Farnborough: Saxon House.

- Harvey, D. 1990. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hedberg, C. 2014. “Restructuring Global Labor Markets: Recruitment Agencies and Work Relations in the Wild Berry Commodity Chain”. In Labor Relations in Globalized Food, edited by A. Bonanno and J. S. B. Cavalcanti, 33–55. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/S1057-1922_2014_0000020000.

- Ilcan, S. 2020. “The Borderization of Waiting: Negotiating Borders and Migration in the 2011 Syrian Civil Conflict.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420943593.

- Inda, J. X. 2006. Targeting Immigrants: Government, Technology, and Ethics. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Janelle, D. G. 1969. “Spatial Reorganization: A Model and Concept.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 59 (2): 348–364.

- Johnson, H. L. 2013. “The Other Side of the Fence: Reconceptualizing the “Camp” and Migration Zones at the Borders of Spain.” International Political Sociology 7 (1): 75–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12010.

- Jones, M. 2022. “For a New New Regional Geography: Plastic Regions and More-than-Relational Regionality”. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 104 (1): 43–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2028575

- Kern, S. 1983. The Culture of Time and Space 1880–1918. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Könönen, J. 2018. “Differential Inclusion of Non-Citizens in a Universalistic Welfare State.” Citizenship Studies 22 (1): 53–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2017.1380602.

- Lahav, G., and V. Guiraudon. 2000. “Comparative Perspectives on Border Control: Away from the Border and Outside the State.” In The Wall Around the West: State Borders and Immigration Control in North America and Europe, edited by P. Andreas and T. Snyder, 55–77. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lenard, P. T., and C. Straehle. 2012. “Temporary Labour Migration, Global Redistribution, and Democratic Justice.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics 11 (2): 206–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X10392338.

- Little, A. 2015. “The Complex Temporality of Borders: Contingency and Normativity.” European Journal of Political Theory 14 (4): 429–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885115584831.

- Martin, L. L. 2012. ““Catch and Remove”: Detention, Deterrence, and Discipline in US Noncitizen Family Detention Practice.” Geopolitics 17 (2): 312–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2011.554463.

- Massey, D. B. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Maury, O. 2022. “Punctuated Temporalities: Temporal Borders in Student-Migrants’ Everyday Lives.” Current Sociology 70 (1): 100–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120936315.

- May, J., and N. J. Thrift. 2001. Timespace: Geographies of Temporality. London: Routledge.

- Merriman, P. 2012. “Human Geography Without Time-Space.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00455.x.

- Mezzadra, S., and B. Neilson. 2012. “Between Inclusion and Exclusion: On the Topology of Global Space and Borders.” Theory, Culture & Society 29 (4–5): 58–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276412443569.

- Mezzadra, S., and B. Neilson. 2013. Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mountz, A. 2011a. “The Enforcement Archipelago: Detention, Haunting, and Asylum on Islands.” Political Geography 30 (3): 118–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.005.

- Mountz, A. 2011b. “Where Asylum-Seekers Wait: Feminist Counter-Topographies of Sites Between States.” Gender, Place & Culture 18 (3): 381–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.566370.

- Murphy, A. B. 2022. “Taking Territory Seriously in a Fluid, Topologically Varied World: Reflections in the Wake of the Populist Turn and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104 (1): 27–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.2022987.

- Olson, E. 2015. “Geography and Ethics I: Waiting and Urgency.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (4): 517–526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515595758.

- Paasi, A. 2022. “Examining the Persistence of Bounded Spaces: Remarks on Regions, Territories, and the Practices of Bordering.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104 (1): 9–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.2023320.

- Page, B., A. Christou, and E. Mavroudi. 2017. “Introduction: From Time to Timespace and Forward to Time Again in Migration Studies.” In Timespace and International Migration, edited by E. Mavroudi, B. Page and A. Christou, 1–16. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Papadopoulos, D., N. Stephenson, and V. Tsianos. 2008. Escape Routes: Control and Subversion in the Twenty-First Century. London: Pluto.

- Rajkumar, D., L. Berkowitz, L. F. Vosko, V. Preston, and R. Latham. 2012. “At the Temporary–Permanent Divide: How Canada Produces Temporariness and Makes Citizens Through its Security, Work, and Settlement Policies.” Citizenship Studies 16 (3–4): 483–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2012.683262.

- Reid-Musson, E. 2018. “Intersectional Rhythmanalysis: Power, Rhythm, and Everyday Life.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (6): 881–897. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517725069.

- Rigo, E. 2011. “Citizens Despite Borders: Challenges to the Territorial Order of Europe.” In The Contested Politics of Mobility. Borderzones and Irregularity, edited by V. Squire, 199–215. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Robertson, S. 2014. “Time and Temporary Migration: The Case of Temporary Graduate Workers and Working Holiday Makers in Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.876896.

- Ruhs, M. 2006. “The Potential of Temporary Migration Programmes in Future International Migration.” International Labour Review 145 (1–2): 7–36.

- Salter, M. B. 2004. “Passports, Mobility, and Security: How Smart Can the Border Be?” International Studies Perspectives 5 (1): 71–91.

- Sellerberg, A. M. 2008. “Waiting and Rejection: An Organizational Perspective “Cooling Out” Rejected Applicants.” Time & Society 17 (2–3): 349–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X08093428.

- Shachar, A. 2006. “Race for Talent: Highly Skilled Migrants and Competitive Immigration Regimes.” New York University Law Review 81: 143–206.

- Sharma, N. R. 2005. Home Economics: Nationalism and the Making of Migrant Workers in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Sigvardsdotter, E. 2013. “Presenting Absent Bodies: Undocumented Persons Coping and Resisting in Sweden.” Cultural Geographies 20 (4): 523–539.

- Sontowski, S. 2018. “Speed, Timing and Duration: Contested Temporalities, Techno-Political Controversies and the Emergence of the EU”s Smart Border.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16): 2730–2746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1401512.

- Sparke, M. B. 2006. “A Neoliberal Nexus: Economy, Security and the Biopolitics of Citizenship on the Border.” Political Geography 25 (2): 151–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.10.002.

- Tazzioli, M. 2018. “The Temporal Borders of Asylum. Temporality of Control in the EU Border Regime.” Political Geography 64: 13–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.002.

- Tervonen, M., S. Pellander, and N. Yuval-Davis. 2018. “Everyday Bordering in the Nordic Countries.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 8 (3): 139–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2018-0019.

- Thrift, N. 1977. “Time and Theory in Human Geography. Part I.” Progress in Human Geography 1: 65–101.

- Tomic, P., and R. Trumper. 2012. “Mobilities and Immobilities: Globalisation, Farming, and Temporary Work in the Okanagan Valley.” In Legislated Inequality: Temporary Labour Migration in Canada, edited by P. T. Lenard and C. Straehle, 73–94. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- van der Ploeg, I. 2003. “Biometrics and the Body as Information: Normative Issues of the Socio-Technical Coding of the Body.” In Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and Digital Discrimination, edited by D. Lyon, 57–73. London: Routledge.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2008. “Borderwork Beyond Inside/Outside? Frontex, the Citizen–Detective and the War on Terror.” Space and Polity 12 (1): 63–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570801969457.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2010. “The UK Border Security Continuum: Virtual Biopolitics and the Simulation of the Sovereign Ban.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6): 1071–1083. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d13908.

- Warf, B. 2011. “Teaching Time–Space Compression.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 35 (2): 143–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2010.523681.

- Warren, A., and E. Mavroudi. 2011. “Managing Surveillance? The Impact of Biometric Residence Permits on UK Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (9): 1495–1511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.623624.

- Weber, L. 2006. “The Shifting Frontiers of Migration Control.” In Borders, Mobility and Technologies of Control, edited by S. Pickering and L. Weber, 21–44. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Xiang, B. 2007. Global ‘Body Shopping’: An Indian Labor System in the Information Technology Industry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, N., G. Wemyss, and K. Cassidy. 2018. “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation.” Sociology 52 (2): 228–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599.