ABSTRACT

This article analyses the politics of spatial justice in the knowledge-making practices of planning expertise in postwar Sweden. The paper traces the genealogy of ‘standards’ in modern Swedish planning, arguing that this was a fundamental form of planning knowledge which came to articulate a ‘universalist’ politics of justice. Standards were constructed as a way to measure and make complex calculations about a range of ‘needs’, making the overarching goal of planning to address the universal human needs measured by standards. This technocratic articulation of justice had limitations. Standards often proved difficult for grassroots groups to contest this expertise, but were a mode of knowledge well-suited to corporate interests looking to influence planners to make space for their standardized consumer products. These tensions came to the fore in the planning of postwar Sweden's green outdoor spaces, where the standards for car users played a crucial role in shaping the landscape and planners hesitated to define national standards for areas such as parks and green space provision. Expert knowledge such as standards might, then, be a powerful tool to systematically shape space according to a particular articulation of justice, yet Sweden’s technocratic road to spatial justice also exemplifies the dangers of this approach.

Introduction

A key geographical concern of planning scholarship is the way that comprehensive visions of ideal future space are constructed as aspirational targets to guide spatial interventions. Indeed, architectural history often frames modern spatial planning as a struggle between different visions of ‘urban utopias’, as exemplified by the title of Robert Fishman’s (Citation1982) canonical work. Borrowing, instead, leading planning scholar Patsy Healey’s (Citation2003, 102) turn of phrase, aspirational ‘blueprints’ were in the postwar era’s ‘traditional conception of a plan’ visions simply ‘translated into built form on the ground’.

Observing the repetitive features of places like Sweden’s postwar landscape it is easy to imagine a social-democratic vision or ‘blueprint’ of a utopian, just city agreed on by a committee of politicians and planners and then ‘translated into built form’ in a myriad of different locations. Indeed, the hubristic utopianism of planners in the heyday of social democracy is the main point of contention with the welfare state’s planners in much of critical literature. The critique levelled by left-wing feminist Yvonne Hirdman, among the most influential historical scholars of postwar Sweden, in her (Citation2018) bestseller Att lägga livet tillrätta is a staunchly Popperian argument against what she argues is a unrealizable technocratic utopia. Similar arguments about dogmatically utopian planners can be found across the political spectrum, as in the writings of the more conservative architectural historian Johan Rådberg’s (Citation1988) influential studies of postwar planning or cultural critic Per Gedin’s (Citation2018) recent assault on Sweden’s modernist avantgarde. Together these accounts suggest a pessimistic story of technocratic planners who may have had good intentions, but whose utopian aspirations to build a just society were destined to fail.

This framing of Sweden’s social democratic planners as overbearing utopians who never achieved their idealistic vision is indicative of a more general critique of midcentury planning. One of the responses to the series of urban crises erupting around 1970, the framing of planning as failed utopianism came to the fore in the 1980s and 1990s just as neoliberal urbanism was being forged. This critique of planning as the flawed attempt to realize rigid utopian blueprints as built space can be found in a broad range of important works on planning from James C. Scott to Peter Hall to (the already-mentioned) Patsy Healey. Anti-utopian arguments do not necessarily line up neatly with a neoliberal agenda, yet there are some clear convergences between this style of critique and actually existing neoliberal urbanism. Such an anti-utopian aspect of neoliberal critiques of planning is perhaps best exemplified by Margaret Thatcher’s favourite geographer, Alice Coleman’s, take-down of British postwar social housing in the aptly titled 1985 monograph Utopia on Trial (Jacobs and Lees Citation2013).

While the interwar architects associated with modernism certainly toyed with utopian visions, I will in this article show how the planners that shaped Sweden’s postwar landscape did not primarily rely on the kind of settled, utopian blueprints translated into urban space which critics have come to focus on. Instead, I suggest that Sweden’s planned postwar geographies are better understood and – more importantly – have more to teach us today if these landscapes are analysed in relation to how their features provided answers to the technocratic problems posed by a particular form of expert knowledge. The most interesting aspect of this planning expertise was, I argue, the way plans were framed by an ambition to know and satisfy what were constructed as quantifiable human ‘needs’, often specified as so called technical ‘standards’. Planning to measure and satisfy needs was the very starting point of Swedish planning policy in the postwar period, and this technical approach was at times even explicitly posed against the speculative utopianism familiar from recent decade’s critique of planning as invariably failed translations of particular visions.

Standards as a mode of planning knowledge which measured needs as abstract quantifications were used to map the built environment, but also to estimate how proposed plans might address these needs. This allowed planners to forecast how plans would increase the satisfaction of needs and raise standards of living or compare different possible plans according to a range of standard benchmarks. Standards were also a mode of knowledge which was understood to be possible to empirically evaluate by systematically studying how realized plans in practice provided for actual users’ needs, to thus accumulate more knowledge about needs and how they related to the built environment. These abstract measurements also proved to be a surprisingly flexible way to co-produce plans between actors and across scales, with planning at the national level primarily setting abstract standards but the planning process being more detailed, concrete, and – at least in theory – open for democratic negotiations the closer it came to the situation on to the ground.

This understanding of standards as way to measure needs allowed Sweden’s postwar planning to become a powerful tool to make the built environment express an understanding of spatial justice as the equal access to a broad range of human needs. That standards expressed such as ‘universalist’ understanding of justice as equal access to all of life’s necessities is no coincidence, as this was clearly in line with the dominant thinking about social provision among the social democrats who governed the country for decades (Rothstein Citation1998). With the social democrats’ ideal of justice codified in the very bureaucratic practices of making planning knowledge, the problem planning sought to fix was the creation of a landscape which provided equal access to life’s necessities. Despite there seldom being anything like a detailed vision of the just city to use as a blueprint, and even in the countless cases of entire housing areas going up with no local residents’ movements voicing demands for more just plans, planners could not help but shape the landscape by systematically identifying and building for the needs which standards sought to measure. For decades Sweden’s landscape was thus quietly and profoundly remade by a social democratic universalist politics of spatial justice, as spatial plans were directed at addressing human needs in this deeply technocratic way.

What constituted ‘needs’ in the view of planning expertise was by no means a culturally neutral process (Mattsson Citation2020), an issue often rendered invisible by the universalist thinking of the modernist architects which the Swedish planners’ notion of basic human needs emerged from This technocratic construction of expert knowledge largely took place beyond grassroots groups democratic control, and thus also beyond the reach of claims marking injustices which much of the critical literature on spatial justice takes as its starting point (e.g. Barnett Citation2018). Nevertheless, formal standards were not fixed once and for all, but produced in complex negotiations and often first pioneered locally in response to issues voiced by specific communities. Indeed, social movements facing off against corporate interests actually played a key role in 1960s bureaucratic struggles over spatial standards for outdoor space in particular. Despite these shifting and at times contentious concerns, for several decades the most basic epistemological concern of Swedish planning remained how human needs could be identified in space and satisfied by spatial interventions.

Since postwar Sweden’s spacious landscapes were not simply derived from a settled welfarist blueprint, there is no lost utopian vision for critics to put on trial or sympathetic scholars to unearth and again apply in practice. Instead, Sweden’s postwar landscapes illustrate the productive capacity of a technocratic bureaucracy whose very mode of perceiving space was shaped by a particularly spatialized understanding of justice. This highlights a rather different set of problems for research to explore than the ‘failed utopia’ framing. Today we would be wise to be critical of the inequalities left intact by the universalist notions of justice expressed by the equal provision of necessities in the built environment that shaped postwar Sweden’s spatial standards. Similarly, when accounting for this bureaucratic practice we must be wary of how it often lacked democratic accountability and the difficulty for grassroots groups to directly intervene in how technical standards expressing needs were constructed. However, Sweden’s postwar planners use of standards as a mode of expert knowledge also speaks of a technocratic road to spatial justice which is more than a statist lack of grassroots confrontation with injustice or inescapably flawed utopian visions of just futures. Thus, standards as planning knowledge articulating spatial justice deserves to be studied on its own terms.

Theorizing the politics of planning knowledge

Many scholars have noted the enormously influential role that the idea of ‘standards’, ‘norms’, ‘types’ or simply ‘demands’ has played until recently in Swedish spatial planning (e.g. Kuchenbuch Citation2010a; Mattsson Citation2010; Hirdman Citation2018; Mack Citation2019; Mattsson Citation2020), before turning their attention to other matters. There are some exceptions where the impact of one kind of standard has been studied in some detail, such as Eva Kristensson’s (Citation2003) work on postwar residential yards, Per Lundin’s (Citation2008) scholarship on traffic planning, or landscape architects’ work on how standards shaped the outdoor environment for children (Janson, Bucht, and Bodeliu Citation2016) and outdoor recreation (Pries and Qviström Citation2021). That few scholars have sought to come to terms with the broader significance of standards for postwar planning is perhaps not so surprising. International scholarship on spatial planning standards is fragmented and largely empirical and descriptive (e.g. Turner Citation1992; Southworth and Ben-Joseph Citation1995; Veal Citation2013).

More theoretically-driven work on planning standards is rare, and tends to frame standards as a collection of desirable, permitted or otherwise sanctioned design typologies, echoing a more general argument about the overdetermining role of settled visions and blueprints in planning. This interpretation is most coherently spelled out in the work of Eran Ben-Joseph, whose Citation2005 The Code of the City has been one of the most important interventions in shaping contemporary debates on standards in spatial planning. By treating standards as any kind prescription of spatial typology – a ‘rule book’ – Ben-Joseph can trace standards as far back as the very first urban settlements. Ben-Joseph then follows this mode of space-making through history and its absorption into modern, and modernist, city-making practices.

Rather than this trans-historical approach to describe whichever ‘rules’ might be deduced from city-making typologies as standards, I suggest thinking about standards in a much narrower sense. With the Fordist standardization of mass production in the early twentieth century, standards came to signify a relationship between knowledge about consumer groups, the design of products, and consumers’ actual use of products. In this article I show that the specific way that standards became used in planning from the early twentieth century is deeply shaped by planners critically engaging with the expertise emerging around the ‘standardization’ of Fordist factories and their measurements of work, productivity, product quality and consumer needs and desires in new ways at the same point in time.

As in many other countries (e.g. Turner Citation1992; Kuchenbuch Citation2010a; Henderson Citation2013; Veal Citation2013), interwar planners experiments with standards as a way to measure standards of living laid the foundations for the postwar expertise which profoundly remade the built environment. The same measurements used to measure standards of living and how these standards might change could also describe, and thus evaluate, the standards of proposed plans. This meant that standards as a mode of planning knowledge allowed calculations about the uses of space in the present and the future, allowing planning to claim it was constructing an ideal landscape without ever settling first on detailed visions of any specific utopian landscape ideal. If form followed function, standards became a way to make complex calculations about which functions were necessary or desirable, which enabled experiments with completely new ideal landscapes derived from this mode of planning knowledge.

This expert knowledge made human ‘needs’, a welfarist normative concern as Raphael Fischler (Citation1998) suggested some twenty years ago (see also Kuchenbuch Citation2010a), the key issue of planning. Many of the interwar architects and planners grouped under the ‘modernist’ label experimented with similar ways of measuring how spaces addressed needs in other places, perhaps most notably in Frankfurt and Berlin before 1933. Still, as David Kuchenbuch (Citation2010a, 161) notes, not even the ‘German architects […] developed such complex tools to register people’s needs’ as the planners of social democratic Sweden of the postwar period.

That standards were used as quantitative measurements to make increasingly sophisticated calculations about how needs could be addressed by planning interventions was arguably the most important aspect of this new mode of planning expertise. Ways to translate empirical details to abstract knowledge is what makes complex calculations possible as a governmental practice, as Tania Li (Citation2007, 6) reminds us Foucault argued. Quantifications are thus both dangerous ways of detaching knowledge from the concrete and productive in enabling bureaucratic systems to relate desired outcomes to interventions in the present even when dealing with complex systems.

Once adopted as policy in postwar Sweden, standards as planning knowledge about needs and needs satisfaction allowed a broad range of actors working across scales, at times in a contentious manner, to experiment with what specifying standards meant in practice. Through a combination of technical research, practical planning experiments and political mobilization, a vast amount of knowledge about needs and how they could be addressed by the production of space accumulated in the postwar period. This made standards an immensely productive kind of bureaucratic knowledge and mode of calculation, something already noted in passing in David Kuchenbuch’s (Citation2010b) work on the relationship between German and Swedish urban planners’ use of standards.

Particularly important was how standards enshrined Sweden’s postwar social democrats’ emerging ‘universalist’ (Rothstein Citation1998) notion of justice as the equal provision of a generous understanding of a dignified life’s basic needs. By integrating this notion of spatial justice in the technical production of space, standards expressed justice in a radically different way from merely a fixed political vision of a just future or grassroots demands forcing planners to respond to demands marking ongoing injustice. Other factors, including social movements and formal policy and cultural critics, were certainly important in pushing planners to address concerns about spatial justice in postwar context. Yet standards made the satisfaction of human needs a technical object of planning knowledge itself. Rather than the technocratic practices of experts being a depoliticized sphere (c.f. Li Citation2007), standards in postwar Sweden shaped landscapes according to this social democratic idea of justice even when there were few immediate pressures from outside forces active in the planning process.

The planning standards used to measure and model human needs also had another effect. This expert knowledge of use and usefulness of space partly crowded out the price mechanism as a way to calculate the effects of plans by measuring market responses to production of space. Esping-Andersen (Citation1990) has discussed the social democratic welfare state as project of decommodifying access to social provisions. Even as the Swedish welfare state left capitalist property relations largely in place and allowed real estate developers to grow immensely powerful, planning standards became a form of largely decommodified expert knowledge about human needs and space which was used to profoundly shape the way people satisfied their needs even as monetary transactions often remained the means to access these utilities. Typical of the hesitant stance of Swedish social democracy, the standard was a tactical recuperation of Fordist practices very much concerned with extending the rule of markets, and thus a decommodification both from within and against the most advanced form of capitalist management and marketing, rather than a clean break from economic logics of capitalist mass society.

When this planning system culminated in the multifaceted, welfarist planning of Sweden’s 1970s it had, however, come up against a set of severe limits. The limit I highlight in this article is how standards as planning knowledge of human needs caused frictions when applied to public space as a site of infinitely complex human interactions. This is related to how standards as a mode of planning knowledge struggled to disentangle itself from its roots within Fordist mass-production and marketing of commodities, an issue which deserves more exploration than this paper allows. These issues were compounded by the technocrats defining needs themselves becoming a point of contention in relation to a range of issues (e.g. Kuchenbuch Citation2010a). The 1970s both saw the expansion of standards to new planning concerns (Pries and Qviström Citation2021) and was also a moment were planners emphasizing community participation increasingly provided a competing mode of expert knowledge to the standard (see Mack Citation2019. See also Mattsson Citation2020). The public amenities and spaces making up the green geographies of postwar Sweden which came to the forefront of planning around 1970 were thus thoroughly shaped by standards as a mode of expertise, but it is also these landscapes which most clearly expose the limits of this mode of planning.

To study how standards emerged as the most salient planning knowledge in shaping the welfare landscapes of postwar Sweden, I draw on what Michel Foucault (Citation1977) described as a genealogical method. My ambition is to follow some of the many different forces and sources of meaning which contingently came together in the making of a particular planning practice (see Fischler Citation1998), in this case standards as a mode of planning knowledge. Thus, I do not aspire to uncover a universal theory of standards, nor to cover all the ways standards as a planning practice have generated bureaucratic knowledge. Instead, I trace the contingent historical geographies which allowed standards to become expert knowledge having a particular set of material effects in a particular time and place.

My account draws largely on an existing, but very empirical, Swedish literature on the historical geographies of planning, combined with a selection from primary sources such as journals, pamphlets, public inquiries and plans. Beginning in the early interwar years, I track how ideas, partly inspired by an international debate among modernist architects, came to shape the notion of standards as a planning practice in Sweden around 1930. I then show how this understanding of the standard was taken up as official policy which profoundly shaped the human environment in the 1940s and circulated far beyond the national state by the 1950s. Finally, I point to how standards as a planning practice encountered difficult limits by the 1960s and was beginning to be rolled back in certain ways by the 1970s, even as it was expanded in other fields and still has a lingering afterlife as informal policy today.

This account of the planning standards’ genealogy is necessarily transnational. The notion of standardization travelled to Swedish discussions on urban space via German debates on typisierung (see Kuchenbuch Citation2010b, 79–80; Henderson Citation2013, 96–98) from the United States’ heartlands of Fordism. However, as I will show in detail, there were contingent forces shaping how standards came to be taken up in Swedish planning, rewiring what was a tool of corporate capital to be more appropriate for public bureaucracies engaged in spatial planning along the welfarist lines of mid-century social democracy. So, while I note important transnational policy mobilities, this article’s main emphasis is on how these ideas in motion were fixed in place and standards were shaped to become a social democratic planning knowledge articulating postwar Sweden’s ‘universalist’ ideals of spatial justice as access to life’s necessities.

Making demands on urban developers

As the First World War came to an end, most of Europe found itself in a severe housing crisis caused by civilian rationing and disrupted supply chains. At this time, Sweden had almost no bureaucratic means of regulating urban space, apart from rudimentary legal specifications for housing construction codified in law to oversee fire hazards and the sanitary conditions of the most densely-populated areas. The 1907 Building Code, a slight revision of a law from 1874, allowed dense urban areas to be built, but with some restrictions; the Code sought to draw a line at tenement-like slums with mandatory yards in all residential buildings, capped building height at five stories and the width of streets at 18, or in some cases, 12 metres (Rådberg Citation1988, 154). Developers were essentially free to build as they pleased, so long as they complied with these basic specifications and a street structure drawn up by skeletal municipal authorities.

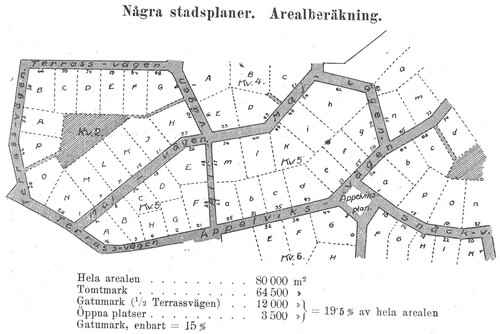

Sweden’s first serious attempt to introduce a more complex set of planning policies sought to go beyond this established legal practice of only using design specifications which barred the most densely populated areas from becoming outright tenement slums. However, it was never adopted. A public inquiry into ‘practical and hygienic housing’, set up by a social democrat-liberal coalition government, made the case in its 1921 report for creating incentives for essentially all builders to build cities differently. The final report was a 323-page book, amply illustrated with hundreds of floor plans, maps and photographs of (mostly domestic and British) attempts to build housing for the urban poor as well as for the upwardly mobile inhabitants of the new garden city suburbs being developed around Stockholm (See ).

Figure 1. The 1921 report on ‘practical and hygienic dwelling’ explicitly sought to use state funding to scale up experiments with garden cities, with green space largely contained within private gardens as in this plan for Äppelviken garden city, included with the report. Uncredited illustration, scanned by author.

Unlike the existing legislation, which had a few strict rules prohibiting specific ways of building, the 1921 report argued for a positive vision of a ‘low-rise and low-density way of building’ to shape most, if not all, urban development (Larsson et al. Citation1921, 26). To do this, the report suggested defining ‘minimum social demands of dwelling’. The most important recommendation was the rather unspecific ‘low-rise and low density’ ideal of maximum two-story buildings. When it came to apartments the inquiry suggested an additional sixteen points specifying ‘demands’, such as mandatory storage spaces, pantries, washrooms, toilets, kitchens with at least 12m2 floor space and bedrooms of no less than 22 m2 (Larsson et al. Citation1921, 106–107).

The report recommended that these detailed ‘demands’ were not to be legally binding like the building codes’ maximum heights of residential houses or minimum widths of streets. Instead, the committee proposed using these ‘demands’ as a precondition for subsidized state credits to those developers who agreed to comply with the demands. The committee thus suggested a model of planning which, unlike the building code, did not only regulate housing for the poorest urban dwellers. Public subsidies would incentivize all construction to move towards a low-rise and low-density urban typology.

This report’s proposals were torn between two different modes of planning expertise. On the one hand was the main ambitions of the report to set up a policy that forced a shift among developers to the low-density typology associated with the garden cities movement (Rådberg Citation1988, 202–203. See also Swenarton Citation1981, 92–117). This was very similar to the British Tudor Walters Report of 1919. The 1921 report’s ‘demands’ were thus much more like the ‘rule books’ for realizing utopian visions which Ben-Joseph describes. However, and more consequentially, the 1921 report was also a first attempt to work out what the ‘necessary spaces of small apartments’ were (Larsson et al. Citation1921, 84), and translate these into quantifiable ‘demands’ as preconditions for applying for state credits. While the means for defining what were ‘necessary spaces’ in this report were rather opaque, the very idea of quantifying ‘demands’ on developers in response to measurable ‘necessities’, and not only having rules to prohibit tenement-like density, marked the first attempt in Swedish planning to define this kind of knowledge as quantifiable categories, prefiguring later ideas about ‘norms’ and ‘standards’ as ways to measure needs. There were, also in this regard, British antecedents to the committee’s argument, but it is less clear if the ongoing debate about ‘decent standards’ in British policy circles (Swenarton Citation1981, 91) had a direct influence on the 1921 report in the same way as Raymond Unwin’s highly publicized plans for a garden city in Letchworth shaped the report’s ‘low rise and low density’ vision.

Little came of this committee’s work in the short term. The unstable political terrain of the 1920s undermined the committee’s proposals, and the protracted rewriting of the old building code stalled again. Still, the proposal had some important effects. Several of the authors, in particular architects Osvald Almqvist and Sigurd Westholm, would continue to play a role in debates about planning which were pushed forward by a new generation of architects. A decade later, this younger cohort revived the committee’s argument for making detailed but non-compulsory ‘demands’ on developers the precondition for subsidized state credits. They also developed the 1921 report’s vague idea that ‘demands’ could relate to knowledge about which spaces were ‘necessary’ in order to live a dignified life. What changed was the fading power of the low-density garden city ideal as the main motivation for rolling out specifications, with new and much more precise ideas about how to measure social ‘necessities’.

Art in the age standardized production

The shift towards more precise models for establishing the ‘necessities’ of life was inspired by the debates about Fordist ‘standardization’, or ‘typification’ as it was first known in many European countries, in manufacturing and marketing. The new ideas about standardization started to spill over into Swedish housing construction and urban design circles around 1920. One example is how the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (Ingenjörsvetenskapsakademien) soon after its 1918 foundation took upon itself to coordinate and settle specific standards for housing construction (Nordlander Finn Citation1994, 98), along similar lines to American and German attempts to standardize construction (Henderson Citation2013, 96).

As state bureaucrats tried to govern the ongoing standardization of housing construction, intellectuals were busy debating the consequences of standardization for art, design and architecture. The way that standardization within firms was seen to rest on new kinds of expert knowledge, an expertise connecting information about potential markets, customer satisfaction and product design opened up new possibilities to theorize planning.

Art historian Gregor Paulsson, chairman of The Swedish Society of Crafts and Design (Svenska Slöjdföreningen, started in the image of the Deutsche Werkbund), became the key figure for reworking the expertise of standardized mass-production to a theory of planning. Paulsson used the authority of his position to sustain a decade-long, meandering debate about standardization, which drew inspiration from a range of international contexts, beginning with the provocative and widely-read 1919 pamphlet ‘More Beautiful Everyday Commodities’ (Vackrare vardagsvara).

Paulsson argued in this pamphlet that standardization held the key to new ways of knowing and shaping the world (Paulsson Citation2008, 89). Having discussed the technical possibilities of standardization, Paulson shifted to how it created new tensions between the artist as designer and business owners. Paulson departed from a bleak diagnosis offered by liberal social theorist Walter Lippmann, who lamented the loss of entrepreneurs as a personal mediator between markets and design, with the massive corporations dominating mass-production relying an army of experts to describe how products were and might be used. This meant that firms dealing in standardized mass-production had little need for individual entrepreneurs assessing what the market needed from direct interactions with customers (Paulsson Citation2008, 119).

Standardization relied on a new mode of expert knowledge, with prototype testing and consumer surveys precisely measuring the needs of different groups of consumer and how well the design of consumer objects corresponded to these groups’ needs. This meant that the influence of ‘the salesman’ could be curtailed in the design process (Paulsson Citation2008, 116–117), by artists using their position as ‘specialists’ to interpret new kinds of statistical information about people’s needs in the design of beautiful, durable ‘everyday commodities’ (Paulsson Citation2008, 106–107). If only designers were liberated from a constant pressure to create cheap and marketable goods for the broad layers of price-sensitive and poor consumers, they could make full use of their new expert knowledge about specific groups’ needs. This, argued Paulsson, meant an emerging ‘potential’ to ‘raise the standards of the form of products’ for all consumers (Paulsson Citation2008, 106).

Paulson’s provocative pamphlet caused a considerable stir, particularly among conservatives. Still, it would take years before Paulsson’s argument that standardization had greater potential than simply generating efficiency would gain any real influence on the Swedish spatial planning debate. Once this happened, the idea of ‘standards’ or ‘types’ provided those arguing for planning making ‘demands’ for what was ‘necessary’ a much more refined theory of how spatial forms could enshrine knowledge about ‘needs’.

Prototyping an architecture of typical housing needs

Inspired by the Deutsche Werkbund’s 1927 Stuttgart exhibition of workers’ housing, Paulsson convinced The Swedish Society of Crafts and Design to start planning for a major housing exhibition. The immense undertaking that eventually became known as the 1930 ‘Stockholm Exhibition’ had several components, but its definitive centrepiece was an architecture competition. Paulsson and modernist pioneer Gunnar Asplund were appointed managing architects, but also involved lesser-known names in the organizing efforts. Osvald Almqvist from the 1921 public inquiry was asked to take part, and the left-leaning cooperative movement’s architectural firm’s director Sven Wallander as well as the radical new editor of the leading Swedish architectural journal Byggmästaren Uno Åhrén took on important positions (Åhrén Citation1930a, Citation1930b, 23; Rudberg Citation1981, 73-74)

Åhrén was by the late 1920s becoming one of Scandinavia’s most important theorists of urban design. He was part of the same circle as Paulsson and his writings regularly appeared in The Society of Crafts and Design’s journal. In 1928 he had intervened in the protracted arguments about a new Swedish building code by proposing ‘density specifications’ (exploateringstal) as a ‘cold, hard and radical’ way to use standard measurements to shape the density of entire urban areas (Rudberg Citation1981, 55–56, 72.). The reform Åhrén proposed would in one stroke make it impossible to build the kind of tightly-packed housing that proponents of planning had been arguing against for decades. Åhrén’s proposal also had a political implication, because it would ensure that plans provided generous public spaces as a sort of urban right guaranteed for all.

To no-one’s surprise, the radical proposal did nothing to settle the gridlocked debates over a new a building code. Åhrén’s intervention did, however, contribute to reframing the problem of overcrowding so that the solution was no longer necessarily the low-rise garden city typology proposed by the 1921 inquiry. ‘Density specifications’ also allowed other typologies to become solutions to crowded cities, such as the first modernist experiments with taller buildings enmeshed in green space. That Åhrén introduced this way to measure density is not surprising, given that he was one of Sweden’s leading proponents of modernist architecture and was at this moment just about to become one of two Swedes in the famed Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM).

Uno Åhrén was particular closely attuned to the German-speaking modernists, and the notion of density specifications was largely inspired by German architectural theorist Anton Hoenig (Rådberg Citation1988, 250). Just as Åhrén gained prominence in Sweden, the circle around CIAM affiliate Ernst May in Frankfurt was experimenting with reducing workers’ housing to the most ‘basic standards’ (grundnormen) in new municipal housing areas built under increasing fiscal austerity (Henderson Citation2013, 96–105). These prototypes became the focus of the 1929 CIAM conference, organized in Frankfurt by May’s group around the theme ‘housing for the minimum of existence’. May’s work in Frankfurt gave Åhrén and his collaborators a second model to draw on, besides the 1927 Stuttgart exhibition, in the run up the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition (See Kuchenbuch Citation2010a, 161–162).

Based on these modernist credentials one might assume that Åhrén’s primary interest in proposing new ways of measuring space was to write a new ‘rulebook’, to return to Ben-Joseph’s understanding of standards, which imprinted the open modernist tower-in-park typology of urban space (e.g. Rådberg Citation1988, 252). This interpretation, however, fits rather badly with the argument modernists like Åhrén were making publicly leading up to the exhibition. In a lengthy article in Byggmästaren’s 1930 special exhibition issue, Åhrén (Citation1930a, 1) explained that the main point of the architecture competition was to ‘radically organize our housing based on studies of housing needs’. Indeed, while Åhrén willingly admitted that this needs-based planning might be branded as ‘radical’, he adamantly argued that it ‘must not be allowed to become utopian’ and sidetracked by lofty visions rather than its actual effects (Åhrén Citation1930b, 25).

To put these ideas into practice, Åhrén (Citation1930b, 26–27) had led a large statistical survey seeking to establish ‘precise’ new, knowledge about ‘housing needs’ in the run-up to the exhibition. The crucial move in this attempt to ensure that knowledge about housing needs was the foundation of planning, and thus prototyping standards as a mode of planning knowledge, was that needs’ were then divided into a set of 15 distinct households’ ‘need types’ (Åhrén Citation1930a, 27). This move drew on a range of different ideas in motion at this particular moment. The framing of housing needs as a worthwhile analysis for more than the most destitute and dense urban areas, already targeted by the building code, expanded the 1921 idea of describing ‘necessities’ for a broad swathe of society. The notion that types of design could correspond to types of need instead echoed Gregor Paulsson’s 1919 argument about how standardization require expert knowledge which allowed designers to by-pass the entrepreneur and directly address the consumers’ needs. These two ideas, clearly represented by Paulsson and Almqvist in the exhibition’s organizing committee, were in turn linked to the May group’s Frankfurt experiments with using the standards of standardized mass-production as a spatial planning technique – albeit to identify the lowest possible acceptable standard rather than define a range of varied need types.

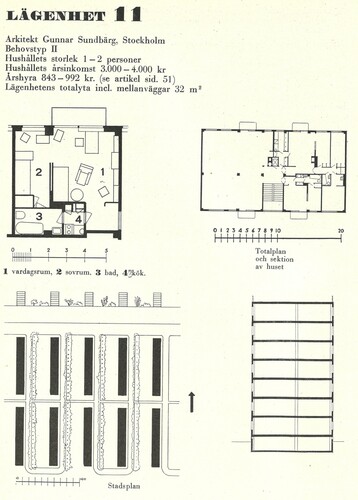

The 15 need types where integrated into the design of the exhibition by making them part of the formal criteria of the architecture competition. Each competing housing design had to show how it addressed the needs specified for a particular need type, both in terms of a range of housing needs like dwelling space and sunlight but also construction costs and potential affordability for poorer residents and what kind of site plan the presented unit was designed for (See ). This approach to organizing the exhibition prototyped a mode of planning where actual needs and how designs respond to these needs were measured with the same ‘precise’ specifications. However, the fact that ‘typical households’ were an amalgamation of measured everyday needs with the household’s economic means introduced a tension that would trouble Swedish planning for years.

Figure 2. The 1930 Stockholm Exhibition is mainly remembered as the mainstreaming of sleek, modernist design ideals, but each furnished home displayed was also carefully designed to model how this home would fit within permanent new housing units which could be scaled to entire housing areas. Drafts of plans for these areas were attached and often included generous green space provision, as in this contribution by Gunnar Sundbärg's team. Uncredited illustration, scanned by author.

The organizer who most explicitly confronted this contradiction was architect and competition jury member Wolter Gahn. In a lengthy article, also published in the special issue of Byggmästaren, he explained that the competition’s contributions were design solutions only for the ‘typical needs’ of some of the different groups in society. It was, Gahn continued, impossible to convert the actual needs of the ‘purely proletarian’ layers of the urban population to ‘need types’ as these dwellers did not have the economic means to satisfy basic universal needs (Gahn Citation1930, 9). Architecture could perhaps transform itself into a field of planning expertise that claimed to both measure actual needs and discipline designs to satisfy these needs for the ‘types’ of households it was built for. However, what architecture could not do on its own was, in Gahn’s words, bring about a ‘classless society’ (Gahn Citation1930, 9). The tension between varying economic means and basic universal housing needs that made it impossible to address the ‘typical needs’ of the most destitute meant that government policy needed to somehow allocate economic means in addition to planning space in order to satisfy human needs. A force beyond architectural design was thus necessary to, according to Åhrén, ensure ‘housing with human dignity for each member of society’ (Citation1930b, 30).

How such socio-economic reforms might look was something that Gahn and Åhrén both outright refused to elaborate at this moment. Åhrén (Citation1930b, 30) unyieldingly argued that the exhibition’s task was to force architecture ‘to pose the problem, formulate the questions, rather than to solve them’. The theory of housing needs as measurable quantities which could be converted into a series of housing types indicated what was necessary for future planners to do. The point of standards was to formulate a new question about spatial planning as one of measuring and addressing needs, but with a clear red line to not undermine universal needs. That the meshing of needs and economic means in the definition of ‘need types’ meant urban design on its own could not provide housing with ‘human dignity’ for all groups thus remained an unsolved problem, yet a problem defiantly put on the table by the exhibition’s organizers.

Governing by standards

The enormous impact of the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition and its controversial showcasing of modernist architecture provided an opportunity for Paulsson, Asplund, Gahn and Åhrén to develop and further publicize their ideas. Together with two other architects, Eskil Sundahl who had also been on exhibition’s organizing committee and the second CIAM-affiliated Swede Sven Markelius, the group responded to conservative critics by collectively writing the 1931 acceptera (‘accept’) manifesto. Just like the Stockholm Exhibition, the manifesto is largely remembered for its showcasing of modernist design, but more importantly for postwar planning it also developed, and propelled to a mass audience, the theoretical debate on standards as a mode of planning knowledge addressing practical problems.

Much of the 200-page long text was an extended argument for standardized mass-production of housing as a way to push down living costs, illustrated by photographs of housing projects for workers wrapped in public green space in places like Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Basel. The acceptera manifesto, however, also doubled down on the argument several of its authors had made in the previous year about specifying housing ‘needs’ as the basis for architecture (Asplund et al. Citation1931, 48). Without the 1930 exhibition’s requirement to showcase for developers how they might shift to building for a range of needs under existing economic conditions, the manifesto pivoted away from the notion of ‘typical needs’ as a way to combine a household’s economic ability and actual ‘housing needs’. Plans should instead be based on universal ‘primary needs’ (Asplund et al. Citation1931, 56) which did not factor in the economic means of the household in question.

‘With a few words’ these universal needs were ‘a healthy and sunny place, enough air and space for those that live there’ as well as ‘a secluded room for sleep’, a ‘common space for all to gather’, ‘a corner for undisturbed study’, ‘enough and comfortable space for cooking’, ‘hygienic devices making good bodily care possible’ and ‘preferably a space for open air leisure’ (Asplund et al. Citation1931, 48). Starting from these fundamental needs underwriting ‘hygienically equal housing for all’, meant taking ‘the worst, not the best, homes’ as ‘the norm of urban planning’ (Asplund et al. Citation1931, 54). Entire areas needed to be planned to make sure that not one single flat was built which did not provide for these universal needs, in particular in terms of access to natural light.

The notion of standards, still sometimes referred to as types, emerging in this debate was not simply a way of reducing a modernist vision of urban space to a ‘rulebook’ of desirable typological features. The acceptera group was certainly interested in experiments with taller buildings, opening up the traditional block and prototyping new kinds of designs. However, such architectural features were only possible solutions to the problem of human needs to be specified as standards. Rather than an existential battle for a new modernist urban typology, these theorists of planning willingly emphasized the need to keep standards ‘alive’, ‘changing it [i.e. the standard] after changes in needs and improved methods’ (Asplund et al. Citation1931, 83). Planning was thus conceived as the mapping of needs, translating these needs into standards for design, to then again map what needs arose as the built environment changed to specify new standards, and so on.

When a social-democratic minority government formed in 1932 and decided to push ahead with the stalled reforms on planning and housing questions, standards as a mode of planning knowledge was a new but well-established idea, tried and tested in the 1930 exhibition and theorized further in the 1931 manifesto. A public inquiry about ‘social dwelling conditions’ was appointed in 1933 by the new Minister of Social Affairs Gustav Möller. The commission was formally led by two civil servants, but also consisted of the left-leaning economist, and future Nobel laureate, Gunnar Myrdal, the famously progressive real estate developer, Olle Engkvist, and three architects. Uno Åhrén and Sven Wallander from the Stockholm Exhibitions’ organizing group were joined by Sigurd Westholm who had been involved in the 1921 precursor inquiry (Rådberg Citation1988, 202–206).

The first of the commission’s reports which had any serious impact on planning was a 1935 document on the housing conditions of low-income families, which proposed a range of reforms including cash allowances for parents and setting up national research centres on the standardization of housing construction. The report also specified ‘minimum needs’ of poor families (Bostadssociala utredningen Citation1935, 197) and thus introduced standards as a way to measure needs in both everyday life and planning documents as national policy. Some of these ‘needs’ were quantified in detail and related to the type of household, like the number and size of rooms and indoor plumbing. Others were still described in more sweeping terms, like access to daylight, green space and front yards, where no detailed consensus existed for setting specific standards. The inquiry recommended subsidizing developers which built for poor families according to the ‘norms’, that is, standards, providing for these ‘minimum needs’.

Unlike the 1921 proposal to subsidize low-density, low-rise development, the centre-left government led by the social democrats managed to secure funding for the 1935 report’s key proposals. The Bureau of Building Credits, managed by Sigurd Westholm, was given a mandate to provide funds for all developers who could show that their new housing construction was up to these standards (Rudberg Citation1981). This policy would fund more than 10,000 new housing units for poor families in the decade that followed (see ). Standards as a planning knowledge to both measure needs and the propensity for designs to satisfy needs was in this way placed at the core of the Swedish state’s new planning bureaucracy.

Figure 3. Housing built with the funding the 1935 report proposed not only entrenched ‘needs’ as a way to measure the output of planning, but allowed for experiments in how to plan areas with more open space which today often are lush landscape in relatively central parts of towns and cities, like this 1936 housing area designed by Wolter Gahn in Stockholm for the new public housing company Familjebostäder. 2020 photograph Arild Vågen, used in accordance with a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license.

After the 1935 report, the committee began the arduous task of designing an urban and regional planning system from scratch. This work continued until 1946, and was marked by debate between those arguing for selective, means-tested welfare reforms targeting the worst-off and those that instead opted for universal social rights. On the one side stood Gunnar Myrdal, who would come to symbolize using the power of state interventions aimed at the poor to socially re-engineer these groups’ behaviours (Hirdman Citation2018). On the opposite side was the Minister of Social Affairs Gustav Möller who, afraid that designing policy specifically for the poorest required an expensive bureaucratic system of degrading means-testing, argued for ‘universal’ social rights (Rothstein Citation1998).

This tension between means-tested welfare for the poorest and universal social rights lined up with the debate about how to measure and specify ‘housing needs’. The Stockholm Exhibition had used a model of ‘need types’, borrowed from the standardization debate’s grouping of consumers on the market. This model’s measuring of needs and economic means – a crucial factor in estimating the market viability of an actual standardized mass commodity – had posed a problem for the large groups that did not have enough economic means to satisfy the most basic housing needs. The 1935 reforms addressed this issue by providing support for landlords building according to the basic standards of minimum needs for one particular group that otherwise could not have afforded this level of housing. With subsidies making housing cheaper for this particular group, planners could after all specify a standard that described needs which were above the minimum level of ‘primary needs’ yet were profitable for commercial developers to build.

This meant that the standards rolled out in 1935 were dependent on regularly means-testing which poor families required assistance to satisfy their primary housing needs and thus qualified for the subsidized apartments. This did not sit well with Möller, the Minister of Social Affairs, whose strategy was to spend as little as possible of his limited budget on bureaucratic expansion by keeping the surveillance of the poor at a minimum. Furthermore, the architects involved had reasons for wanting to go further. The acceptera group’s argument for making standards describing universal ‘primary’ needs ‘the norm of urban planning’ had by the 1935 reforms been contained to a small minority of all housing construction. All but segregated islands of social housing for the poor was as unplanned as ever. With the interests of Möller and the architects around Åhrén aligning, it is then perhaps not surprising that the committeés final 1946 report, written after Myrdal withdrew from the group, rolled out standards as the main way for the state to manage planning beyond just poor families.

The final policy proposals were prefigured by Sigurd Westholm, still in charge of the Bureau of Building Credits which managed state loans for the housing built along the lines suggested in the 1935 proposal. In April 1942 Westholm’s bureau quietly issued a 28-page brochure which, vaguely citing ‘directives’, provided oddly specific ‘minimum demands’ for a wide range of apartment types (Statens byggnadslånebyrå Citation1942). Any developer who wanted to borrow cheaply from the Bureau could from this point on do so for any kind of multi-family housing construction, at least in theory, as long they sent in blueprints complying with these minimum specifications (See Rådberg Citation1988, 296).

When the final report in 1946 concluded that ‘state loans for housing construction appear to be the fundamental means for a politics of housing seeking to raise standards of living’ it already had the means to achieve these ends in place (Bostadssociala utredningen Citation1946, 541). The report proposed a range of new policies, like legislation endowing municipalities extensive legal rights to plan constructions and mandating that municipal authorities provide housing for all residents as a universal, social right. The most important means for managing this process towards specific outcomes was, however, formalizing universal standards as the evaluation criteria for the Bureau of Building Credits subsidized loans.

A new government agency, the Housing Board (Bostadsstyrelsen), was founded in 1948 and tasked with managing state credits and the corresponding standards. From 1954 the Housing Board issued these standards as a printed booklet called ‘Good Housing’ (e.g. Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen Citation1954). Since the planning system put in place by the late 1940s required all construction to be approved by municipal authorities that were responsible for local plans, all the Housing Board needed to do was to compare the already-approved municipal permissions with its national standards.

This system thus set up a multi-scalar co-production of planning, where municipal planners, politicians, developers and residents could work out the messy details locally. The national bureaucracy only had to define the standards, review already-approved plans, sign the checks, and then evaluate how the housing actually built stood up with sociological research in order to evaluate and refine standards. While these standards did not necessarily measure the things everyone might agree corresponded to the most urgent ‘housing needs’, standards would reliably steer development on the ground towards predictable and, on its own terms, just outcomes without any need for the Social Department or Housing Board’s central bureaucracy to intervene directly in local planning.

The limits of standards

Once formally designated as the foundational mode of expert knowledge of Swedish planning in 1946, standards took on ever-greater importance for planning in the decades that followed. A key actor was the well-funded State Council for Research on the Home (Statens byggnadsforskningsnämnd), originally set up in 1942 as a government commission (Nordlander Finn Citation1994, 53–67), which sponsored both quantitative and qualitative studies of the home and its needs. The State Council was complemented by independent groups, most notably the Research Institute for the Home (Hemmens forsknignsinstitut) founded by a coalition of women’s groups in 1944. These experts carefully mapped the home as if it were a workplace in order to set new design standards to ease the burden of reproductive labour, standards largely then adopted as policy by the Housing Board. This intervention, however, also did much to ensure that the nuclear family remained the planners’ standard unit of measurement, illustrating one of the many normative assumptions shielded from controversy as housewives demands for better conditions were translated into technocratic expertise (see Hirdman Citation2018).

Another important non-state actor mapping needs through standards was the left-leaning cooperative movement (Mattsson Citation2010). When the Swedish association of cooperative housing in 1954 celebrated its 30th year and 100,000th completed apartment, an entire chapter of its luxuriously illustrated coffee table style anniversary book was dedicated to detailing the associations’ use of its own standards. Indeed, the book argued that it was by the strict adherence to these ambitious standards that the organization had made a ‘contribution to the housing standard development’ of Sweden (Holm Citation1954, 209–238).

While standards was perhaps then a form of expertise beyond the direct influence of most people, this knowledge was plainly contestable by at least non-state expertise. Experts from government bureaucracies and popular movements both shaped what needs standards sought to measure, just as local planners and elected politicians coproduced actual plans with the national bureaucrats who used policy to fix standards in documents like Good Housing. That planning experts were sensitive about maintaining these multiscalar relations can be seen in the important 1956 public inquiry on ‘collective housing utilities’ (Bostadskollektiva utredningen). Its final report discussed a range of ‘norms’ as the solution to its overarching aim of raising the minimum ‘standard’ of life, but the report also cautioned decisionmakers against attempts to formulate one-size-fits-all solutions oblivious to ‘local knowledge’ (Bostadskollektiva kommittén Citation1956, 196).

This ‘local knowledge’ was in some places, however, already based on more advanced standards than the Housing Board's, with the immensely detailed 1952 Comprehensive Plan for Stockholm (Stockholms stads stadsplanekontor Citation1952) being the prime example. The 1952 Comprehensive Plan, printed as book and used as a field manual far beyond the capital, specified standards for access to a range of recreational amenities, a move probably inspired by Abercrombie’s 1944 Greater London Plan (see Turner Citation1992). Municipal planners all over Sweden soon adopted this approach, with the second and third largest Swedish cities, Göteborg and Malmö, in the 1950s setting their own standards for the planning of outdoor recreation (Schlyter Citation1976, 31). Stockholm retained the leading edge in this municipal production of standards as a tool for comprehensive planning, drawing on the same research as the Housing Board on things like children’s needs in the outdoor environment, but adopting a much more ambitious set of standards with the 1965 document Plandstandard (Jansson, Bucht, and Bodelius Citation2016, 84).

This move of standards out from the home, however, encountered challenges. Key modernist planners like Stockholm’s City Gardener Holger Blom warned that the benefits of elusive activities like children’s play defied quantification (Lundin Citation2008, 74), and the Housing Board’s standards were explicitly vague on the outdoor environment. The 1954 version of ‘Good Housing’ even conceded that ‘guaranteeing a good outdoor living environment only through norms’ wasn’t possible (Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen Citation1954, 21). The Board highlighted the need for careful urban design, and only made vague recommendations for playgrounds in every yard visible from the home, ‘preferably visible from the kitchen window’ (Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen Citation1954, 19). In the 1964 edition of ‘Good Housing’ some quantifiable specifications about outdoor spaces had been added, but only when it came to the proximity and size of playgrounds (Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen Citation1964, 48–50).

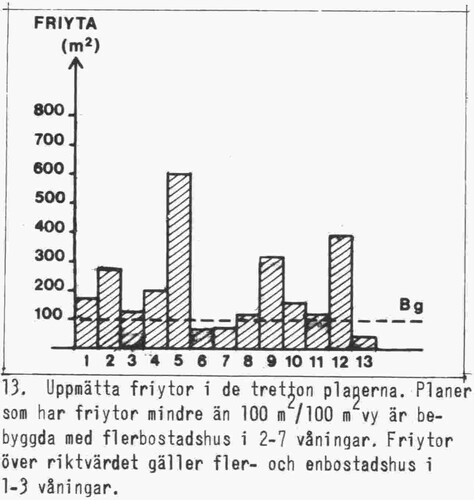

There were extensive demands for more detailed open space standards in the proposed update to the 1964 version of ‘Good Housing’, but developers lobbied against these proposals and they were severely delayed (Schlyter Citation1976, 29–30). By 1968 the state credit system that had enforced the standard as a mode of planning knowledge was being reformed, and when comprehensive national open space standards were eventually published in 1972 they were formulated as recommendations rather than being wedded to the economic power of subsidized credits. These detailed standards for playgrounds, bus stops, open space and much more were available in a booklet called ‘The Neighbourhood of Housing’ (Bostadens Grannskap) and could, perhaps, be seen as the highpoint of standards of welfarist planning knowledge in Sweden (see ). In practice developers seldom adhered to these specifications with the same rigour as the ‘Good Housing’ standards, because they were not tied to the reformed state housing credit system (Schlyter Citation1976; 29–30. See also Kristensson Citation2003, 56).

Figure 4. ‘The Neighbourhood of Housing’ not only provided a range of government standards for open space, but also an appendix that showed how these benchmarks could be used to compare existing areas in quantitative terms and correlate planning typologies with how well they corresponded to key standards. One example such as this comparison of open space square metres to housing square metres in thirteen new housing areas – the minimum standard suggested being the dashed line. Uncredited illustration, scanned by author.

There were, then, certainly ambitious open space standards, like the comprehensive plans for Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö or the detailed standards proposed by government commissions like the 1970 public inquiry into children’s outdoor environments (Schlyter Citation1976, 30; Jansson, Bucht, and Bodelius Citation2016, 85). Yet, the only ‘need’ outside the home that the powerful Housing Board quantified in detail in the early editions of ‘Good Housing’ was those of car owners (Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen Citation1954, 19–20). So-called ‘parking space norms’ (Parkeringsnormer) also came to shape the built environment profoundly, as did the widely circulated so-called ‘SCAFT 1968’ research report on traffic safety for residential areas which proposed standards for a whole range of needs both for drivers and pedestrians (Lundin Citation2008). This report’s standards contributed to making large systems of spaces for mobility and recreation designed with children’s needs in mind a foundational aspect of Sweden’s postwar landscape. The same standards also hard-wired a ‘car society’ into the very material fabric of built space in a way typical of how standards came to be used to make space for the car in other contexts internationally (Lundin Citation2008).

The ease with which standards were adopted to produce space for cars speaks to how this planning knowledge remained influenced by its origins in a Fordist conceptualization of standardized commodities made for mass consumption. The car, like apartments and their kitchen appliances, was a consumer commodity tied to the household which made its prevalence predictable and planning standards easy to relate to manufacturers’ output of standardized commodities. Combining research on how much space each car ‘needed’ to move about with forecasts of average cars owned per household made modelling of the total needs of space for cars within a residential area as a standard more predictable, unlike the patterns of pedestrian mobility which some planners saw as too complex to quantify.

Business interests organized around standardized mass production and consumption, making their products apt objects for plans, came to powerfully shape both this mode of planning and its content, leading to a series of conflicts in the 1970s. A 1975 public inquiry contrasted the diligence with which the ‘parking norms’ had been followed and the spurious attention to standards for children’s playgrounds, when examining what had gone wrong with Malmö’s huge Rosengård residential area, regularly described as a planning failure (Barnmiljöutredningen Citation1975; 58. See also Zalar and Pries Citation2022). A year later a paper from a special government-funded research group on ‘urban open space’ formulated a similar critique, arguing that the ambiguity of open space standards had allowed corporate developers to ignore these unprofitable undertakings and focus on following the narrower car-related standards in line with their economic interests (Schlyter Citation1976, 27–30).

Despite the unenthusiastic, and often, vague government standards set for all things related to open space, informal and local standards as a way of making sense of space thoroughly shaped the postwar landscape, contributing to the ‘spaciousness’ of the postwar typology described by landscape architect Eva Kristensson (Citation2003). In part, the limited guidelines on open space that did exist in national standards must be understood to have played a key role in this regard. Most important was that God Bostad, despite its vagueness, argued that multi-story buildings should be compensated for the lack of private gardens by allotting more generous public green spaces to these areas (Kristensson Citation2003). Equally important was that standards were also sought out, or even created in situ, by local planners trained to measure needs using quantifications. One example of how this mode of knowledge was used even when it was not mandated from above is how planners in the Upplands Väsby commuter community between Stockholm and Uppsala for decades used detailed standards within all major planning ventures. Even in the early postwar period planners explicitly cited a range of sources, like the standards proposed in the 1952 Stockholm Comprehensive Plan. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, planners in this small municipal planning department continued to look at Stockholm’s ambitious experiments with standards, but also included proposals from government inquiries that had not been implemented, consultancies which proposed standards for recreational facilities, work done on standards by community organizers like the Tenants Union and even the standards proposed for using green space to separate traffic from pedestrian areas proposed in the infamous SCAFT report on trafic safety (Pries and Qviström Citation2021).

The 1970s was certainly the most creative period of municipal green space planning in places like Upplands Väsby, where emerging critiques of lingering economic inequality and a ‘car society’ was combined with a range of actors proposing standards contributing to a complex and evermore green co-production of plans. Still, this was also the period where standards as planning knowledge began to lose its institutional sway, with the state credit system that had been the main mode of enforcing standards being rolled back at the turn of the 1970s. National standards, including the ambitious open space provision of The Neighbourhood of Housing booklet or the Swedish Building Norms specifying how the Building Code was to be reinterpreted by municipalities, were for many years only used in the technical negotiations preceding municipal building permits (Schlyter Citation1976, 30). However, this meant that both the pressure to comply with standards created by attaching norms to subsidies and the possibility of direct oversight by national bureaucrats in early phases of the planning process were rolled back, and the sense of ‘living standards’ as a way to continually experiment with ways to identify and satisfy human needs was slowly eroded.

Meanwhile, the cultural radicalism of the 1968 generation worked itself also into social-democratic planning (Lundin Citation2008, 242–244). New notions of how planners might represent and imagine the world they sought to intervene in would begin to take the place of standards, often inspired by ideas about local and lay knowledges trumping expert measurements (e.g. Mack Citation2019). Increasingly, Swedish planning was, with the slow shift to neoliberal urbanism, relieved of the unfashionably welfarist burden of making the ambition to know what needs human beings might have the epistemological challenge undergirding spatial planning (Mattsson Citation2020, 175–6).

Conclusions: a technocratic road to spatial justice?

The notion that planning imperfectly imprints fixed visions of an ideal future on space has long shaped the scholarship of planning. This perspective has been a crucial component in critical studies of the public production of space, including framings of social democratic Sweden’s postwar planners as hubristically failing to realize visions of a spatially just society (Rådberg Citation1988; Gedin Citation2018; Hirdman Citation2018). Utopian visions aside, this article argues that the basic problem that Swedish planners of the postwar years were tasked to solve was the ‘universal’ provision for fundamental human ‘needs’. This problem was codified as planning knowledge through a series of technical standards which sought to measure everyday life’s various needs, plans’ ability to address needs and the outcomes of plans in relation to the needs of the actual residents populating newly built environments.

This particular use of standards allowed complex and multi-scalar production of planning knowledge and plans, radically different from what we might expect if analysing the postwar public geographies crafted as a product of a fixed utopian ideal or vision imprinted on people and place without any regard for local conditions. National planners used standards as an abstract form of knowledge to monitor how actual plans were worked out in detail by local actors, at times including popular movements mobilizing their own set of technical standards. The bureaucratic energy devoted to setting and refining technical standards also allowed complex calculations of needs largely independent from the market’s processing of information about demand and supply. In practice this use of standards is perhaps best viewed as an unplanned experiment in how to construct decommodified, multiscalar spatial knowledge about human needs.

Standards as expert knowledge enshrined the dominant social democratic idea of spatial justice as the right to have a very generous conception of ‘universal’ needs addressed deep within planners’ technical knowledge-making practices. This dry, technical articulation of justice is not only quite different from plans that seek to translate blueprints of a spatially just world to built space which many critics of utopian planning have focused on. This unapologetically bureaucratic engagement with spatial justice is also radically different to the way that many scholars have posed contentious claims of injustice as the constitutive act of aspiring to make space just (Barnett Citation2018). Instead, Sweden’s technocratic road to spatial justice meant that the landscape was quietly but profoundly shaped by planning practices designed to systematically view space as a collection of universal human needs which plans must be designed to satisfy.

Technical standards as a mode of planning knowledge encountered a set of limits that should not be dismissed. Which needs that were important enough to be measured and what counted as an appropriate standard were both contested by non-state actors throughout the postwar period, in particular by large and powerful organizations like the women’s movement or the cooperative movement. Still, standards as planning knowledge proved difficult to challenge for groups that could not leverage technical expertise for their own ends. Conversely, powerful economic interests used their control over this technical expertise to profoundly shape standards, best exemplified by the real estate interest’s lobbying against open space standards in the late 1960s. Further, the social-democratic notion of justice as ‘universal’ access to generously defined ‘primary needs’ expressed by planning standards allowed potentially disruptive political conversations around ownership, redistribution, power and recognition to remain at the margins of planning, surely a serious downside of this attempt to chart a technocratic road to spatial justice.

Another serious limit of standards that planners at the time identified was dealing with needs radically different from the commercial mass-production of commodities which the very notion of technical standards was lifted from. Who needed what, and if standards could gauge this, was a particularly intensely-debated issue when it came to public green spaces. There were certainly ambitious attempts to use standards to craft complex public spaces speaking to many different groups’ range of needs, and this had profound effects on Sweden’s ‘spacious’ and lush postwar landscape. Particularly important was the creatively co-produced planning knowledge which combined several unofficial standards created by different actors, often at the municipal scale. Still, government planners’ hesitation about measuring the complex range of needs which public spaces could sustain postponed national standards for open space for decades and made this mode of planning less forceful in this field. Paired with intense corporate lobbying, this lack of national standards meant that the standards for open spaces which tended to be followed most carefully were that of the car: a privately-owned, mass-produced consumer object easily quantifiable in terms of road capacity and parking space per household.

Bringing the example of postwar Sweden’s standards to bear on contemporary debates, it is neither the welfarist standards nor the universalist ideal of justice which the standards articulated that appears to have most to offer. Instead, I would argue that the genealogy of Sweden’s postwar planning standards illustrates that the very technical practices of producing planning knowledge can have important material effects and thus political stakes worth grappling with. The Swedish welfarist use of standards might, then, hold few ready-made answers about what kinds of knowledge planners today can use to chart a technocratic road to spatial justice. But with Uno Åhrén’s argument about the need to first ‘formulate the questions’ in mind, planners seeking spatial justice would do well to ask how the epistemic devices or our time might be put to use as planning practice towards new, more just, ends.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Andrés Brink Pinto, Erik Jönsson, Amalia Engström, Märit Jansson, Mia Ågren, Mattias Qviström, and “@Sniltroll” for fruitful discussions, as well as Richard Ek and the two thorough referees at Geografiska Annaler B who provided very useful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åhrén, U. 1930a. Stockholmsutställningen och framtiden. Byggmästaren: Utställningsnummer, 1-3.

- Åhrén, U. 1930b. Bostadsavdelningens planläggning och tillkomst. Katalog över bostadsavdelningen, Stockholmsutställningen 1930. Stockholm: Bröderna Lagerström.

- Asplund, E., W. Gahn, S. Markelius, G. Paulsson, E. Sundahl, and U. Åhrén. 1931. Acceptera. Stockholm: Tiden.

- Barnett, C. 2018. “Geography and the Priority of Injustice.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2): 317–326.

- Barnmiljöutredningen. 1975. Barn: Rapport Från Barnmiljöutredningen Nr 6: Barnen och den Fysiska Miljön. Stockholm: LiberFörlag.

- Ben-Joseph, E. 2005. The Code of the City: Standards and the Hidden Language of Place Making. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Bostadskollektiva kommittén. 1956. Hemmen och samhällsplaneringen. Stockholm: Beckman.

- Bostadssociala utredningen. 1935. Betänkande med förslag rörande lån och årliga bidrag av statsmedel för främjande av bostadsförsörjning för mindre bemedlade barnrika familjer jämte därtill hörande utredningar. Stockholm: Ivar Häggströms boktryckeri.

- Bostadssociala utredningen. 1946. Slutbetänkande del 1. Stockholm: K.L. Bäckmans boktryckeri.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Fischler, R. 1998. “Toward a Genealogy of Planning: Zoning and the Welfare State.” Planning Perspectives 13 (4): 389–410.

- Fishman, R. 1982. Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT P.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Nietzsche, Genealogy, History. In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice, 139–164. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Gahn, W. 1930. Bostadsavdelningen på Stockholmsutställningen. Byggmästaren: Utställningsnummer, 8-54.

- Gedin, P. 2018. När Sverige blev modernt: Gregor Paulsson, Vackrare vardagsvara, funktionalismen och Stockholmsutställningen 1930. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag.

- Healey, P. 2003. “Collaborative Planning in Perspective.” Planning Theory 2 (2): 101–123.

- Henderson, S. R. 2013. Building Culture: Ernst May and the New Frankfurt am Main Initiative, 1926-1931. New York: Peter Lang.

- Hirdman, Y. 2018. Att lägga livet till rätta: Studier i svensk folkshemspolitik. Stockholm: Carlssons.

- Holm, L. 1954. HSB. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers boktryckeri.

- Jacobs, J. M., and L. Lees. 2013. “Defensible Space on the Move: Revisiting the Urban Geography of Alice Coleman.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (5): 1559–1583.

- Janson, M., E. Bucht, and S. Bodelius. 2016. “Fri lek och fast normer: om lekplatserna reglering.” In Plats för lek: Svenska lekplatser förr och nu, edited by M. Jansson and Å Klintborg Ahlklo, 72–93. Stockholm: Svensk Byggtjänst.

- Kristensson, E. 2003. Rymlighetens betydelse: en undersökning av rymlighet i bostadsgårdens kontext. Lund: Lunds universitet.

- Kuchenbuch, F. 2010a. “Footprints in the Snow. Power, Knowledge, and Subjectivity in German and Swedish Architectural Discourse on Needs, 1920s to 1950s.” In Swedish Modernism: Architecture, Consumption, and the Welfare State, edited by H. Mattsson, and S. O. Wallenstein, 160–169. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Kuchenbuch, F. 2010b. Geordnete Gemeinschaft. Architekten als Sozialingenieure – Deutschland und Schweden im 20. Jahrhundert. Bielefeldt: transcript Verlag.

- Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen. 1954. God Bostad. Stockholm.

- Kungliga Bostadsstyrelsen. 1964. God bostad: idag och imorgon. Stockholm.

- Larsson, Y., O. Almqvist, G. Göthlin, A. Ingelman, and S. Westholm. 1921. Praktiska och hygieniska bostäder. Stockholm: Kungliga Boktryckeriet.

- Li, T. M. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Lundin, P. 2008. Bilsamhället: ideologi, expertis och regelskapande i efterkrigstidens Sverige. Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag.

- Mack, J. 2019. “Renovation Year Zero: Swedish Welfare Landscapes of Anxiety, 1975 to the Present.” Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskrift 76: 63–79.

- Mattsson, H. 2010. “Designing the Reasonable Consumer: Standardization and Personalization in Swedish Functionalism.” In Swedish Modernism: Architecture, Consumption, and the Welfare State, edited by H. Mattsson, and S. O. Wallenstein, 74–100. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Mattsson, H. 2020. “Norm to Form: Postmodernsim, Deregulation and Swedish Welfare State Housing.” In Neoliberalism on the Ground: Architecture & Transformation from the 1960 to the Present, edited by K. Cupers, C. Gabrielsson, and H. Mattsson, 167–194. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Nordlander Finn, A. 1994. Byggforskningen organiseras: 1900-1960 Statens kommitté för byggnadsforskning. Stockholm: Statens nämnd för byggnadsforskning.