ABSTRACT

Whereas geographers have outlined the effect of neoliberalism on the discipline, we ask how neoliberalism has particularly altered what it means to be a geographer. We do this by exploring geography as a vocation. After a summary of debates about academia and vocation, we present an overview of autobiographical and biographical writing on becoming a geographer. In these accounts, we note the increased attention that has been paid to issues of race, class, gender and precarity as shaping both what geography is and who can pursue it. These accounts are then contrasted with visual timeline interviews we undertook with geographers in UK secondary and higher education. We found a strong sense that geography is not simply a job, but a calling or vocation. However, this experience of vocation is being undermined by neoliberalism marked in particular by metricization and casualization. We argue, however, that both individually and collectively geographers are finding ways to resist the deforming effects of neoliberalism and to reclaim a sense of vocation. Although we recognize that vocation is a problematic and historically situated notion, we conclude that it is a productive new way to approach contemporary debates on what it means to be a geographer under neoliberalism.

1. Introduction: geography and neoliberalism

From the 1990s onwards, there have been extensive discussions about the impacts of neoliberalism on what Sidaway (Citation1997) calls ‘the production of British geography’. In this paper, we contribute to these debates by suggesting that using the concept of geography as a vocation opens new perspectives on what it means to be a geographer under neoliberalism. Whilst recognizing that neoliberalism is an international phenomenon, we do this by exploring the life and work histories of geographers in English secondary and higher education institutions. Methodologically, we approach vocation by analysing visual timelines produced and narrated by geographers to describe their career pathways. In this, we draw on the pioneering Scandinavian scholarship by Buttimer and Hägerstrand which established autobiography as an apposite way to explore the emergence and practice of a geographical sense in the whole life course.

Sidaway (Citation1997) describes the imagined Golden Age of 1960s UK academia – increasing numbers of young people eligible for higher education following the ‘baby boom’ and political pressures to widen participation among an expanding middle class. This was a moment of opportunity, but also of entrenched inequalities. It was subsequently followed by a period of neoliberal ‘Thatcherite hegemony’ paving the way for a move to competitive research funding, formal staff appraisal and research audit exercises beginning in 1985 (Sidaway Citation1997). The import of neoliberalism in this way has led to momentous changes in both secondary and higher education. These include: external audits such as the Research Assessment Exercise (REF) for universities and the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (OFSTED) for schools (regular assessments of an institution’s performance); pressure to rise up to local, national and international league tables which recast schools and universities as competitors rather than collaborators (Lakes and Carter Citation2011); a preoccupation with branding and image (Wæraas and Solbakk Citation2009); the massive growth of casualized labour in universities as a fragmented labour force emerges to facilitate university success in these audit and league table systems (University and College Union Citation2019); and the deployment of new technologies of Human Resource Management (HRM) which conceptualize staff not as autonomous educators but as ‘resources’ to be scientifically managed by realigning their work to the achievement of management ‘visions’ (Legge Citation2005).

Reflecting on these changes, the Analogue University geography writing collective (Citation2019b) conceptualizes neoliberalism as leading to a change in university governance from causation to correlation. That is, managers switch their register of engagement with the wider world from the vocational reasoning that education is worth pursuing as a social good in itself, to a more pragmatic and adaptive neoliberal approach of seeking to correlate their activities to perform well in the latest metric. This has resulted in the decline of individual and collective staff wellbeing, as staff struggle to meet rising demands (Gill Citation2010; Franco-Santos and Doherty Citation2017). These pressures exacerbate existing inequalities and have led to important discussions around gender, race, and equality within academia (McDowell and Peake Citation1990; Mountz et al. Citation2015; Navarro Citation2017; Noxolo Citation2017; Caretta et al. Citation2018; Smyth, Linz, and Hudson Citation2019; Okoye Citation2021).

These feminist and other accounts illustrate the importance of individual autobiographies for understanding how the professional lives of geographers are an outcome of ‘interactions between actors and social structures’ (Al-Hindi Citation2000, 697). In this article, we develop this autobiographical aspect to think through interactions in the neoliberal university. We build on the multiple studies by geographers of both neoliberalism itself and its impacts on our lived experience of being geographers, yet we seek to do something different: to explore how neoliberalism is changing what it means to be a geographer in secondary and higher UK education. The original contribution of this article is to do this through the conceptual lens of vocation. In particular, we use autobiographies to explore the specific reasons why people want to be geographers, and how their experiences of becoming geographers have been impacted by neoliberalism. By ‘geographers’ we consider in this article both school and university teachers, because they are part of the same project of geographical education, share many key assumptions about the nature of the discipline, and have been subject to similar processes of neoliberalism.

The article proceeds as follows. It first outlines debates about vocation in cognate disciplines, particularly sociology. It then discusses the place of autobiography in geography, arguing that it is an appropriate way to explore the senses of vocation. The visual timeline interview method is then introduced and the research activity is summarized. The substantive material asks (1) why contemporary geographers became geographers (emphasizing a sense of vocation), (2) whether and if so how neoliberalism is radically threatening their sense of vocation, and (3) how they are finding ways to resist this and reclaim their sense of the geographical vocation. In doing so we offer a new angle in which to think through the impacts of neoliberalism on being a geographer.

2. Becoming a geographer: An autobiographical approach

2.1. Academia and vocation

In their much-cited 2008 sociological survey of US attitudes about individualism and community, Habits of the Heart, Bellah et al. identify three ways of thinking about work. A job sees work as a means of making money. The idea of career emerged in the nineteenth-century as a course of professional life that offers an individual advancement and achievement, yielding a self that is defined by success in an occupation through rendering work as a source of self-esteem. Finally, calling or vocation links a person’s work to a larger community, where work constitutes a practical ideal of activity and character that makes a person’s work morally inseparable from his or her life and from the common good (Bellah et al. Citation2008, 65–66).

This way of thinking about work as vocation has its origins in Christian thought and its long tradition of evaluating work in terms of how socially beneficial it is (Kidwell Citation2016, 170). However, it was the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther who first systematically conceptualized work as vocation. In a landmark study of theologies of work, Miroslav Volf summarizes Luther’s concept of vocation as everyone being able to serve God and humanity by performing well in their station or profession. This had two significant consequences: overcoming the medieval distinction between active and contemplative lives, and ascribing greater value to work than previously (Volf Citation2001, 105–106). Luther’s ideas on vocation have fallen out of favour with theologians, who have questioned the basis of its Biblical interpretation, its suitability for modern mobile industrial and informational economies, and its lack of resources for questioning alienation and dehumanization in work and thereby fostering structural change in employment relations (Volf Citation2001, 108–109). As well as losing theological support, nineteenth-century secularization led fewer people to view their work as a direct calling from God.

However, as Baumeister argues, the concept of vocation has endured. Instead of an external divinity, people commonly locate their calling in alternative sources such as the nation, or recognize ‘internal calls’ linked to notions of self-actualization assuming that supposed inherent giftings, natures and dispositions ought to be recognized, cultivated and pursued (Baumeister Citation1991, 15). Today it is more commonly sociologists who discuss vocation. Weber’s famous 1917 ‘science as a vocation’ essay contrasted ‘the external organisation of science as a profession’ with ‘an inner vocation for science’ seeking to gain personal satisfaction from achieving something ‘perfect in the realm of learning’ (Weber Citation2004, 7). The appeal – and also the peril – of this concept of vocation as a way to rescue academic work from the corrosion of neoliberalism is illustrated in a prominent discussion between sociologists Les Back and Ros Gill. Back places vocation centrally in his widely read Citation2016 Academic Diary. Interpreting Weber’s suggestion that ‘science is a vocation’ as meaning ‘a disposition and a way of holding to the world’ (75), he argues that this is being undermined by the neoliberal assault on education marked by managerialism and audit. In the face of this, he contends, we need to resist and act differently, and to do this ‘see that what we do is not just a job but an intellectual vocation or craft’ (10–11).

Gill takes issue with Back on this. She argues that whilst ‘vocation’ ‘captures something real about our passionate attachment to our work, which is palpably different from many other jobs’ (106), this ideal can have serious, detrimental consequences:

Many of us suffer deeply because we do live up to this ideal—we spend lots of time with students, we look at draft after draft of dissertations, we stay up all night to write references for students and colleagues, we review generously for journals—and sometimes, after all of this, completely exhausted, there is nothing left for ourselves, and nowhere to turn for support, and it is usually at those moments that your HoD says, ‘why haven’t you published in any top ranked journals this year?' (105–106)

‘Vocation' can, she argues, paralleling the critiques of theologians like Volf, ‘so easily become a disciplinary mechanism, a way of extracting yet more work from us at intense personal cost’ (106). In reply, Back accepts Gill’s description of the university, but insists that ‘The problem is that the pressures within contemporary university make the weight of that vocation hard to carry. This is the key problem rather than the idea of an intellectual vocation itself’ (Back Citation2018, 121). Back (Citation2018) engages with bell hooks’ (Citation2009) description of teaching as a ‘prophetic vocation’ and that ‘integrity of vision’ is central to speak critically to structures of power and oppression. Back insists that it is these structures that we need to change and that the notion of scholarship as a vocation provides important imaginative resources to enable us to do that. As hooks writes:

The more I teach, the more I learn that teaching is a prophetic vocation. It demands of us allegiance to integrity of vision and belief in the face of those who would either seek to silence, censor, or discredit our words. In Jim Wallis’s book The Soul of Politics he maintains that the prophetic vocations require us to be ‘bold in telling the truth and ready to uphold an alternative vision— one that enables people to imagine new possibilities’ (hooks Citation2009, 81)

These debates about the concept of vocation, and the tension between its progressive vision and its shortcomings, help us understand how our interviewees reflected on their autobiographical accounts of becoming geographers. We did not set out to ask about vocation, but because the term came up so often in our interviews we turned to the above literature to help structure our analysis of the material. This perspective, we argue, allows us to present a novel perspective on how neoliberalism is changing what it means to be a geographer in secondary and higher UK education, and thus complements and advances existing work on the lived experiences of neoliberalism.

2.2. Is geography a vocation? An autobiographical approach

The notion of vocation offers a novel way of thinking through the effects of neoliberalism on what it means to be a geographer. In this article, we explore how geographers think about vocation through the medium of autobiography.

The pages of Geografiska Annaler are a very appropriate place to discuss autobiography in geography, because of the importance of the International Dialogue Project (IDP) that ran out of the collaboration between Anne Buttimer and Thorsten Hägerstrand based at Lund University (Hägerstrand and Buttimer Citation1988). The pair collected and reflected on the autobiographical essays and video recordings of 150 geography (and other) academics. Buttimer pioneered the use of autobiography in geography (Jones Citation2018) with her groundbreaking 1983 book The Practice of Geography which built on an eclectic range of theoretical, philosophical and Christian humanist traditions (Buttimer Citation1983b). Buttimer argued that autobiography was useful for inviting the reader to engage in ‘a shared intersubjective task’ of clarifying the ‘relationships between Geo-graphic thought and practices in the lived experiences of humankind’ (Buttimer Citation1983a, 3), helping us answer the question of how does ‘a geographical sense emerge, how is it articulated, disciplined, and practiced?’ (4). Buttimer influenced others, including Pamela Moss (Citation2001) edited collection, such that Daniels and Nash felt able to refer to an ‘autobiographical turn’ in geography (Daniels and Nash Citation2004, 450). This was perhaps too strong a claim, with Purcell contending in response that ‘the place of autobiography is not secure in the discipline’ (Purcell Citation2009, 238).

Nonetheless, Buttimer’s argument about the importance of autobiography in helping us understand the emergence of geographical sense is arguably borne out by an examination of extant autobiographies. It was geography that enabled Peter Gould (Citation1999) to understand the intersections between his own life and his historical context. It was walking down her local high street that informed Doreen Massey’s (Citation1991) insights into a ‘global sense of place’, helping her to grasp the connections between her life, the local, and the global. As such, Carl Sauer’s (Citation1956, 287) observation that the ‘geographer partly is born, partly shaped by his [sic] early environment’, is one that explains the close connection between those who choose geography and their own life experiences.

In its newsletter, the Historical Geography Research Group of the Royal Geographical Society publishes an occasional section entitled ‘How I became a geographer’ in which members are invited to reflect on their own journey into geography. In almost all accounts it is the relationship with people and places that have sparked their interest; visions of wanting to change the world and make it better; and how the political context in which they grew up shaped them (see for instance Kearns Citation2016; Thomas Citation2016). Similarly, Janet Townsend’s landmark feminist book Women’s Voices from the Rainforest (Citation1995) begins by explaining how, over her long career, she was shaped by the intellectual trends and political contexts of the times and places in which she lives. Notably, these accounts point to how people became geographers following geography’s critical turn. This marks a move away from the history of ‘Big Men’ and biographical accounts of explorers, as well as the ‘hidden histories’ of colonial exploration central to the formation of the UK’s Royal Geographical Society (Driver Citation2013). What it means to be a geographer is therefore increasingly linked to calls to decolonize geographical knowledge and pursue critical approaches. As Noxolo (Citation2017, 318) writes, geography is both ‘deeply implicated’ in colonial histories but also ‘well-placed to respond to the call to decolonise knowledge’ when long-term commitments are made.

What is striking for this paper and its focus on what it means to be a geographer is that many of these autobiographical texts are marked by a sense of geography as a vocation – something which emerges strongly in the International Dialogue Project. Aadel Tschdui (the first woman professor of geography in Norway), wrote that ‘geography is a calling’ (Tschudi and Buttimer Citation1983, 36). Likewise, France’s first woman geography professor, Jacqueline Beaujeu-Garnier, spoke of her ‘calling to geography’ (Beaujeu-Garnier Citation1983, 142) – a calling that is ‘an integration of research and teaching, of university life and participation in public action’ (151). Similarly, in his autobiography Who Am I?, Yi-Fu Tuan frequently refers to his work as a vocation, beginning sentences with expressions like ‘My vocation in geography’ (Tuan Citation1999, 93). These autobiographical accounts are especially striking because not only is geography described as a vocation, but because of the absence of dynamics which we would describe as neoliberalism. In sharp contrast, contemporary accounts of becoming geographers in the neoliberal academy are marked by two different questions.

The first is how neoliberal logics are shaping academia, and the adaptive strategies and energies demanded to simply survive. Hartman and Darab (Citation2012) write that neoliberalism has led to more individual working patterns, the valorization of individual over collective work, and the valuing of quick research through funding and outputs. For Shahjahan (Citation2014, 3), neoliberal logics create divisions and competitive working environments in which certain working practices are valued. This extends to how we teach geography at university as changing assessment techniques value specific forms of learning and the move to the modular system in geography results in the danger of a ‘tyranny of choice’ and ‘frequent high-stakes assessment’ (Harland et al. Citation2015, 539). A further element of the neoliberal metrics management of universities has been the so-called ‘impact agenda’, where universities are required to show the positive societal impact of their work. Although Pain, Kesby, and Askins (Citation2011) posit ‘a politics of positive appreciation’ in which this agenda can be recuperated for critical ends, Slater (Citation2012) argues that it is impossible to simply play the neoliberal game, as we are inevitably changed by adopting the language and logic of these agendas. He argues that ‘precious to scholarship is the ability to ask our own questions drawn from astonishment at the world, from a thirst for intellectual/theoretical discovery, from political outrage and commitment to praxis', an ability that is eroded by the neoliberal impact agenda (Slater Citation2012, 118).

Second, if neoliberalism affects how geography is done, it also affects who can do it. A considerable literature has arisen in which individuals reflect on how gender, class, racial inequality, disability, and the vulnerabilities of being an ECR affect who can enter the neoliberal academy (Al-Hindi Citation2000; Acker and Armenti Citation2004; Mansfield et al. Citation2019). Navarro (Citation2017, 507) argues that women of colour are disproportionately affected by neoliberal restructuring in universities because they are ‘disproportionately represented in the ranks of unsecured, contingent labour’. In such a context, Caretta et al. (Citation2018) argue that who is able to continue in the neoliberal academy is affected by factors such as gender, class, and mother-tongue. Bhakta (Citation2020) draws on personal experiences as a British Indian researcher with cerebral palsy to argue this shapes her research and that academic practice and experiences of academia must consider intersectionality. Tolia-Kelly (Citation2017) writes in a first-person collective voice to offer a narrative experience of being a Black woman in the discipline of Geography and their experiences of micro-aggression, bullying, and isolation. Similarly, Tate (Citation2014) uses auto-ethnographic reflections to explore how neoliberal structures in the university ensure Black academics are ‘bodies out of place’ to keep white hierarchical structures intact. Daley (Citation2020) argues therefore that even as white feminists struggled to carve out space for women’s voices in geography they marginalized the voices of black women geographers.

These unequal power dynamics in academia are therefore part and parcel of geographical knowledge, as these academic structures shape knowledge production (Mansfield et al. Citation2019). A study by Hawkins, Manzi, and Ojeda (Citation2014) exemplifies this as they examine the everyday and corporeal experiences of graduate students in Geography PhD programmes across North America to explore how the corporatized university alters the lifeworlds of academics, the process of becoming a geographer, and structures of knowledge production. Okoye’s (Citation2021) report into supervising Black geography PhD students in the UK, argues that structures of racial discrimination and exclusion deter Black students from Postgraduate study and succeeding in their goals. She argues that a lack of retention of Black students should be understood within processes of marginalization and disparities that Black academics face in neoliberal higher education. She details how the lived experiences of students and academics shape wider knowledge production in academia. As such we must begin to explore how neoliberalism as well as shaping the lived experiences of being a geographer, in turn shapes how knowledge is produced in geography.

In describing this shift in the literature to reflection on how being a geographer has changed to who can be a geographer, we are not suggesting that the sense of vocation is entirely absent. We see echoes of it in calls for resistance. For example, the feminist-inspired slow scholarship movement calls for our work to be marked by an ethics of care and collaboration, for slowness ‘before the writing even begins, in research design, community engagement, and the pursuit of personally and meaningful work’ (Mountz et al. Citation2015, 1244). Similarly, in their call for collective industrial action as a way to challenge the deforming impacts of neoliberalism, another geographical collective, The Analogue University, insist on foregrounding ‘the truth that science and education have a fundamental, non-relational and non-negotiable value for society, and that they are of intrinsic worth in and of themselves’ (The Analogue University, Citation2019a, 1202). All of these strategies of resistance, in other words, call for a return to the reasons why we became geographers and the importance of understanding the wider life histories of academics, especially within different structures of power.

In this section, we have illustrated that exploring autobiographical writing and the reasons why individuals want to be geographers makes a new contribution to existing literature on neoliberalism. We acknowledge the value of existing work exploring how neoliberalism alters the experience of being a geographer and an academic and the valuable insights this work has offered into understanding the impacts of neoliberalism. However, we suggest that considering autobiographical writing and the reasons why individuals became geographers through the lens of vocation offers an important and novel contribution to the literature. It connects experiences of neoliberalism with debates in geography on positionality and the connection between knowledge production and our individual biographies.

3. Method

This research was conducted by the authors over the course of the year 2018–2019 as part of a larger study of workers in charity and public sector employment in the North East of England (Megoran Citation2019). Following Yin (Citation2014, 16), it was devised as a case study seeking to investigate a contemporary phenomenon (the experience of the workplace as humanizing or dehumanizing) in depth and in its real-world context (the effects on neoliberalism on personnel management technologies in the not-for-profit sector). Material for this article is derived from visual timeline interviews conducted with eight geography academics and eight geography schoolteachers, who in this article are considered equally as ‘geographers’. This cuts against the grain of research on geographers which tends to be bifurcated into studies of either teachers (for example, Corney Citation2000) or academics (for example Mountz et al. Citation2015). Tellingly, texts such as Johnston and Sidaway’s Geography and Geographers (Citation2016) and Moss’ Placing Autobiography in Geography (Citation2001), whose titles claim to be about ‘geographers and ‘geography’ in general, are in fact only about academic geographers. Johnston and Sidaway (Citation2016) do recognize that schoolteachers are also ‘professional geographers’ but exclude them from their analysis because, they claim, teachers are not committed to the basic canons of the university which are to propagate, preserve and advance knowledge (2).

We regard this omission as problematic and suggest five reasons why the separation of secondary and higher education geography is unhelpful for understanding the geographical profession under neoliberalism. The first is predicated on a vision of geography as what Bonnett (Citation2008) calls ‘the world discipline’, an understanding widely shared by the geography academics and teachers whom we interviewed. Second, this vision relates to the nature of the university. When students formally graduate, they do not cease to be part of that society. Our interviews showed multiple ways in which geography teachers continued to identify with higher education: attending summer schools and public lectures organized by university geography departments, engaging in joint pedagogical research, and inviting academics to meet their students. Third, the adoption by geographers (e.g. Pain Citation2004) of participatory action research methods pioneered by sociologists (Whyte Citation1994; Greenwood and Levin Citation1998) has contributed towards a recovery of the perspective that geographical knowledge is not the sole preserve of academics. Fourth, not all geographers in HE advance new knowledge, whereas some schoolteachers do so; and all schoolteachers transmit and preserve knowledge, so the distinction Sidaway et al make is unconvincing. Fifth, both school and university geography in the UK have been subject to similar processes under neoliberalism, and considering them together may help our broader understanding of neoliberalism’s impact on geography.

3.1. Visual timeline analysis

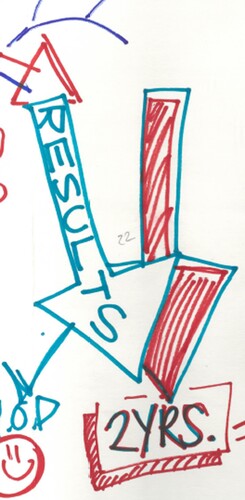

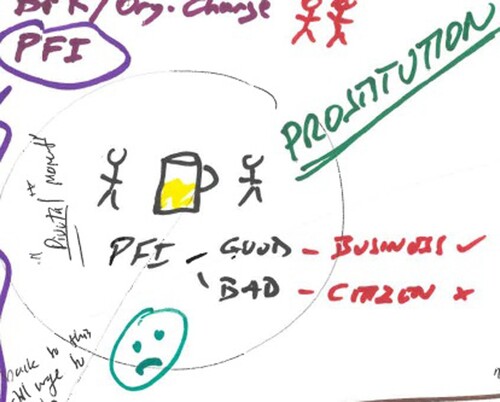

To explore how our participants experienced work as geographers over time we used visual timeline methodology (VTM). This combines narrative histories with visual methods, as developed by Mazzetti and Blenkinsopp (Citation2012, 652) to enable a focus ‘on significant life events that could be compared across participants’. In order to draw out their autobiographies, interviewees were asked to tell the story of their working lives by drawing a timeline, using visual metaphors as far as possible. Following this, interviewees were then asked to mark on the timelines moments or periods when they felt treated in humanity-affirming or dehumanizing ways, and to reflect on these. Finally, they were asked how employers could ensure they were treated in humanity affirming rather than dehumanizing ways. show examples of sections of timelines produced.

We conducted 16 such interviews, each lasting between 1½ and 4 h. Interviews were not audio recorded, allowing greater openness; summaries of narrative accounts written up for publication were subsequently checked with the individuals concerned. Interviewees were recruited randomly (using university departmental staff lists with individuals approached based on random number generation) or by gatekeepers (especially in the case of schoolteachers, where introductions were sought from headteachers, trade unions, and geographical teachers’ associations). They ranged in length of service from people who had worked five decades to those in their first year. Indexing the gender balance in these professions, the majority of schoolteachers interviewed were women, whereas academic staff were more evenly split. All the schoolteachers interviewed worked as geography teachers; some of the academics were employed in geography departments, whilst others worked on geographical themes (for example climate change policy) and methods (GIS) in cognate departments such as planning or economics.

VTM has its origins in ‘critical incident technique’ developed in psychological studies of how workers function in workplaces (Flanagan Citation1954) and has been most used by scholars in psychology and business studies (Chell Citation2004). We found that it is highly appropriate for geographical research. Not only is it a powerful way to structure the listening and telling of individual working life autobiographies, but as a visual method, it prioritizes place. Most people (including non-geographical participants in the wider study, overall n = 55), told the stories of their lives through drawing places: home, school, places of work. As Buttimer argued (see above), we found that these autobiographies facilitated the articulation of how a geographical sense emerged and was practiced. VTM in particular asks respondents to draw and narrate visual timelines of their careers and to consider how wider life events have shaped their careers. Champagne argues that timelines are important semiotic devices which ‘enable the drawing of connections not previously made, allowing novel features to come into view’ (Champagne Citation2016, 13).

All respondents work in the North East of England. To protect anonymity, we have conflated all the HE institutions to a fictional ‘Northtown University’ and all the schools to an equally fictional ‘Northtown Academy’. In one case we discuss, an outcomes-based performance-management system, it would not be easy to conceal the particular university and write up the data meaningfully, and therefore all quotations have been checked with respondents.

As part of a wider research project on human value in the workplace, our research was inductive giving respondents – quite literally – a blank canvas on which to draw out the issues of importance to their experiences as geographers. We recognize that a broad range of important dimensions of being human (including race, religion, disability, gender, class, ethical convictions and philosophical worldview) are important structurally for questions of who can be geographers and how they experience the work of being geographers, and that these dimensions are not forefront in our findings. This design of this study leads to this limitation as it did not directly ask participants about these dimensions, nor did it choose participations based on them. Our analysis here is results-led, focussing on the topics of vocation and neoliberalization that repeatedly came up in these interviews.

The remainder of this paper discusses our three key findings about the ways in which neoliberalism is altering what it means to be a geographer. First, we explore geography as a vocation rather than a career or a job. Second, we outline how this vision of geography as a vocation is being challenged under neoliberalism, and third, we discuss the means through which neoliberalism is resisted, both individually and collectively.

4. Geographical formation: vocation

We saw above that Bellah et al. identified job, career, and vocation as the three main ways that US citizens think about work. Although in practice these three may all overlap (Baumeister Citation1991, 127) our interviews showed that geographers’ primary motivations for choosing their work emphasized vocation over career.

Geography lecturer Simone could point to a dramatic change of work and income upon entering academia. After graduating she worked for a US-based global data and media conglomerate, living a glamorous lifestyle of first-class travel between the world’s metropolizes. Eventually, she returned to academia to do a PhD on issues of justice, discrimination, and racism, which appeared increasingly important to her in Britain at that time. This came at personal cost – her income dropped from around £70,000 p/a to a £12,000 stipend, meaning she had to get part-time jobs to manage. However, she was driven by a belief in ‘the value of education’ and recounted that ‘I felt I could do something where I could make a real change’.

Kevin, also a lecturer at Northtown, identified his sense of geographical vocation as being formed earlier in his life than Simone’s. The experience of being a student during the 2003 US-UK invasion of Iraq was decisive here. He described his studies as ‘a very empowering education’ with seminars being ‘exciting and dynamic’, helping him reflect on the war as part of a range of global injustices, giving the students ‘a sense we could do something about this’. This sense was intensified by an ongoing industrial dispute on his campus coinciding with the anti-war activism, and the solidarity of ‘hanging out together’ heightened the quality of the experience for him as local and global scales became intertwined through both his studies and his activism. Pursuing graduate studies seemed a sensible next move. ‘I didn’t think much about ‘career’’, he reflected, ‘I was lost in the theory, it was so moving, a mind-opening exercise, constant questioning’ at what was ‘an intense time for the world’.

Bryony, a secondary-school geography teacher, drew a visual timeline of her working life that was punctuated by an extended period teaching overseas. This was in an educational culture that was far less marked by the outcomes-based performance-management culture of school geography that had emerged in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s. It was striking that she used the word ‘career’ up until that point in the interview, and then switched to talk about ‘vocation’. We pointed this out to her, and she said:

Oh yes, I don’t think of it as a career now, you have to want to do it. You have to see it as a vocation. You have an impact on children’s lives, and I like that … A goal is to let them know that they can leave Northtown if they want to, and qualifications are a way to do that.

By asking Bryony to reflect on her entire working life, the way in which neoliberalism has impacted her sense of vocation clearly emerges. Similarly, Jamie recounted that he was inspired as a schoolboy by his geology teacher, and so eventually found work as a geophysicist undertaking surveys for a private geological company. The company worked him hard and he experienced low job satisfaction, feeling that ‘I was working to line someone else’s pocket'. What he really enjoyed in the role was setting up and running placements for students from his former sixth-form college. He found this very rewarding, feeling that he was making a difference by helping people along their career paths, and it was more enjoyable than the main part of the job itself. He retrained as a teacher, finding ‘instant job satisfaction’ especially as he worked with kids with challenging behaviour – ‘I felt I was giving back into the system’. He recounted that when asked in his job interview what his ambitions were, he replied, ‘I just want to enjoy my teaching’ – he wanted to be a classroom teacher, and to get good at doing that. ‘Job satisfaction is more important to me than pay', he said, adding that he took a pay cut to become a teacher. He explicitly contrasted his motivation with that of a manager whom he described pejoratively as ‘career-minded’ and whose ambition made the working environment more fraught, as she inculcated ‘a culture of fear’.

4.1. The cost of vocation: ‘Ask Marx about his work-life balance’

Our research showed a clear (although not uniform) sense of geography as a vocation. However, it also showed, as Gill (above) argued, that a sense of vocation can lead teachers/academics to accept lower wages and unmanageable pressure. For example, university lecturer Simon can clearly remember the ‘pivotal’ moment that precipitated a dramatic career change from management consultancy to academia. Over a drink with colleagues after a day’s work, he began reflecting on how he thought the Private Finance Initiative-funded hospital and prison projects on which they were working were a good deal for business, a good deal for management consultants, a good deal for the government, but a bad deal for the taxpayer (see ). This discussion led him to quit his job and enter academia to research, write and teach students about topics he regarded as very important including attitudes to climate change and how those attitudes themselves can be changed. He took ‘a significant pay cut’ (of around 50%) to do this and said that many years on ‘I am still earning considerably less than I was in my previous role’. But he did this because he believes that there is ‘something important to be said, and it’s interesting'. He takes satisfaction from it, regarding it as ‘important for the world – it is nice to feel you are changing the way people think’.

The experience of another interviewee, geography lecturer Amanda who researches climate change policy, reflects Gill’s (Citation2018, 106) diagnosis of vocation leading to self-imposed over-work and suffering when ‘we cannot live this vocational ideal’. Her work is motivated by a strong sense of the importance of her topic and the urgency for society to make significant changes to mitigate anthropogenic global warming: ‘there may be only a few years left to change things’. She describes the topic as ‘eating her up’, so that she devotes considerably more time to her work than she is paid to. This was, tellingly, the only interview we conducted at a weekend, and Amanda herself observed the irony of this as she reflected on work–life balance and that her own life was in ‘tension’ with the ideals of the feminist scholarship that she espouses: ‘I ask myself, if I am not working, ‘Have I really earned this weekend?’’ Although she would recognize the tensions that Gill identifies and acknowledges the drawbacks of seeing geography as a vocation, the greater meaning of her work and the urgency and clarity with which she explained this was striking: ‘these are historically important moments, and may be the only opportunity we have to do this’. Gill’s critique misses the fundamental point that for Amanda it was not an unexamined choice to understand her work this way: she knew the costs, but for her, it was a response to a compelling external call. ‘Being a vocationally political-active person is not a 9–5 job', she emphasized: ‘This is the revolution … Ask Marx about his work-life balance’.

5. Geographical deformation: neoliberalism

We have seen the motivations for becoming a geographer in both secondary and higher education: a fascination with subject, and the sense that a geographical education and particular topics within it are important for the public good in and of themselves. Together these constitute a sense of geography as a vocation and as we have seen this produce a high sense of intrinsic motivation and a committed work ethic. But in this section, we explore from our interviews how neoliberalism threatens and undermines this sense of the geographic vocation: in particular through metricization and casualization.

5.1. The metricized distortion of geography

Secondary-school teacher Michelle told us that due to attempts to correlate her school’s activities to national audit regimes, ‘since 2015 my role as head of geography has been reduced in importance’. She claimed that this was a direct result of the school’s desire to do well in the English and Mathematics Standard Assessment Tests (SATS) that were used to grade the school. There is no geography SATS test, so her school had sought to improve its SATS scores by reorientating other subjects to help improve English SATS skills. ‘It’s all about ‘topics’ in years 5 and 6 now, geography is squeezed out', she complained, to help with the English SATS: ‘so their [work]books look like English books now’. She recognized this as a national phenomenon: ‘More schools are playing the game now’.

Michelle complained that this erosion of the importance of geography had a series of other consequences. One is that the school is less willing to provide resources for ongoing training, so she has to arrange this herself. More significant have been contractual issues. Having previously been head of geography and history, she took two parental leave breaks. After the first one, she returned to work three days a week and dropped her head of geography and history role, and after her second she was told, she recounted, that she would never be given the full-time job she wanted because she was on too expensive a pay grade and geography was not seen as important enough. She has, therefore, had to take on a series of other part-time jobs to make financial ends meet. The gendered aspects of employment doubly work against Michelle, as a mother and as a geography teacher under changing neoliberal audit regimes.

All of this disturbs her not only because of personal financial cost, but because of how it devalues geography. ‘There’s definitely a concept of education as a machine', she argues – learning exam technique just so students can pass an exam and bump up the school’s position in league tables. In contrast, she felt geography should be defended on intrinsic grounds: ‘I do really value geography as a subject, I think it’s important to the children'. She gave examples of a recent lesson she had run on the production of sporting goods, fair trade and links to Premier League football: ‘It’s so important to every aspect of their lives, I really value the subject', she said, ‘making them more interested individuals’.

Some teachers highlighted the scalar nested nature of audit. Stan spoke very critically of changes that occurred under the UK’s Liberal Democrat – Conservative coalition government (2010–2015), placing particular blame on Education Secretary Michael Gove’s special advisor, Dominic Cummings. Driven by a concern that the UK was ‘slipping down the [international] league tables', they ‘decided that we needed to make everything harder’. As a result, Stan complained, there is ‘no time to talk about love of geography and meaning of place’ – previously ‘we needed two lessons for this', he recounted. ‘Data-managers drive a lot of these changes', he concluded. This corroborates Keddie and Lingard’s contention that the English schooling system ‘is actually constructed or constituted through these data and the data infrastructures that manage them’ (Citation2015, 118).

On beginning her working life as a geographer, academic Rachel had said to herself that this was ‘the best job in the world’. However, like Stan, she relayed how she experienced a focus on metrics and audit as jarring and deforming of her sense of vocation. She drew particular attention to her arrival and induction at the Northtown University. After being offered the job she remembered being asked by a colleague, ‘What kind of academic do you want to be?’ She described the feeling of this as, ‘Wonderful – I felt I had freedom’. However, the formal induction process when she did start was in marked contrast. For example, as a new staff member, she was invited to an ‘away day’ about ‘“strategizing” your career’. She found its utilitarian approach to the academic life jarring:

It was all about money, networking, etc. For example, how to become a CO-I [co-investigator on a large grant]. There was nothing about ideas, about how to generate them, etc. We were told instead that a good way to become a CO-I was to get in with top PI-s, so there was advice on how to network them. Until then, I had only said ‘I love this job.’

It was like people were counting pennies and came and told me how many I had got and how many I needed. But I had a small grant, of £3000: in my field site that paid for travel, subsistence, and doing over 30 interviews. I don’t need these huge amounts.

At conferences you get ‘REF warriors’ – people who play the game, have got all the targets, and talk the talk.

5.2. Casualization of academic labour

We earlier encountered Amanda, Simone and Kevin, all of whom had strong senses of vocation in becoming academic geographers. However, their careers did not unfold as they had hoped because they all became part of the new academic precariat. The UK HE trade union, UCU, argues that as a business model increasingly pursued by universities, casualization has become a ‘massive problem', with extensive reliance on a reserve army of poorly paid, expendable labour (Megoran and Mason Citation2020; Mason and Megoran, Citation2021). As recently as 2016, Johnston and Sidaway describe fixed-term teaching positions as an ‘apprenticeship’ stage of the ‘academic career structure’ (Johnston and Sidaway Citation2016, 2). This view has become quickly outdated: our interviews showed that this casualization of academic labour ruptures a sense of the traditional expectation of career progression from PhD to permanent lectureship.

As we saw above, Kevin was drawn into geography as a student at the time of the 2003 Iraq War, attracted to a community of people committed to working towards a more just and peaceful world. But following his PhD he entered a discouraging period of casualized employment. Although he initially enjoyed the research and teaching he was doing for other people as a post-doctoral researcher, over two years he applied for around 80 jobs, and spoke of how a ‘new sense of panic and discouragement’ set in. As he said:

After ten years of masters, PhD, post-doc, you put everything into that, all your energies – you are just getting rejected, and ask, ‘what has the system done to me?’ It has led me into a dead end. I remember feeling that this is very dehumanising. Maybe we should have been more honest with the PhD students telling them that only a few of you will get jobs. We should at least be honest and say clearly that there are many more candidates for a dwindling number of jobs. This was terrifying.

Geographers who were able to move from casualized to permanent contracts were able to gain, through the contrast, further insights into how it treated people. Amanda – who as we saw earlier entered academia driven by a strong compulsion to influence climate change policy – reported that prior to her current permanent position at Northtown University, she had lived on a series of temporary contracts. These drained her energy, as she made ‘more than a hundred applications’ and had 15 interviews whilst being on temporary contracts. Finally, having secured an open-ended position, she appreciated, in particular, the care of her new academic colleagues: ‘everyone is supportive’ personally and professionally, whether this was in giving her freedom to design a new course, or personal care at time of family illness, she noted. She emphasized what she described as ‘coming into a permanent community’ and as a result ‘to be asked how you are doing’. This contrasted with her previous experience of years and years ‘bouncing around on temporary jobs’ which were all marked by ‘a lack of pastoral care’. Now, Amanda felt ‘recognised and supported by colleagues’. In contrast, that recognition is denied to temporary staff who can be less visible to the formal institutional mechanisms and processes, and less visible to their colleagues as building supportive relationships inevitably takes time. Therefore, temporary staff can miss out on the quality of workplace relations and supportive communities that geographers on permanent contracts reported in interviews as being of particular value. This includes the ability for individuals to pursue their own research as in both short-term teaching contracts and post-doctoral positions there is often little or no time built in for this. Furthermore, the invisibility and sense of lack of belonging described in the interviews above is more likely to be experienced by those discriminated against for race, class, gender, and disability (Okoye Citation2021; Tolia-Kelly Citation2017).

These interviews suggest that using autobiographies to interrogate being a geographer through the notion of vocation offers new insights to augment existing research on working in the neoliberal academy. Exploring autobiographies enables understanding of the wider life histories that led individuals to become geographies and how neoliberal policies have been experienced by geographers throughout their whole life course. Neoliberal metricization and casualization degrade the experience of caring communities and alter the value of academic research that our respondents reported to be an important part of their sense of being geographers.

6. Resisting neoliberalization: reclaiming the vocation

If the sense of geographical vocation that animated many secondary and higher education geographers has been eroded or deformed by neoliberalism, our interviews also pointed towards ways in which geographers are resisting the deforming effects of neoliberalism, by engaging in both collective and individual practices of resistance to reclaim that sense of geography as a vocation.

6.1. Collective resistance, communities of care

Autobiographical writing is not simply about the individual: it informs collective care and resistance by enabling people to connect with others and think about their life stories in relation to wider events and relationships with others. A specific example of collective resistance to the deforming effects of neoliberalization was opposition to an outcomes-based performance-management (OBPM) scheme called ‘Raising the Bar’ (RTB) introduced in one section of Northtown University in 2015–2016. A classic example of OBPM, it set academics a range of crude targets for grant capture, publications and PhD supervisee completions as a way to align individual working practices with particular management goals. These goals were entirely products of a neoliberal imperative that equated success with Northtown’s position in league tables: for example, ensuring the university was in the world’s ‘top 200’ universities and having ‘at least 10 subjects (Units of Assessment) which are ranked top 50 in the world’ (Morrish Citation2017). Failure to hit targets could result in staff being moved to teaching-only contracts or even eventually being dismissed from the university. It created great anxiety and fear amongst staff at Northtown, as well as unhappiness on the part of many middle-managers who were instructed by the university’s ‘Human Resources’ department to implement it.

Although some authors see opposition to such neoliberal logics as essentially futile (Kalfa, Wilkinson, and Gollan Citation2018), Northtown staff actively sought to resist the scheme. Ultimately, they voted on industrial action in the form of a marking boycott, leading to the swift capitulation of management and withdrawal of the scheme. Geographers were particularly involved in the dispute, and a Northtown-based geography collective, The Analogue University, subsequently conducted research about it. They used industrial relations theory of mobilization to explain how activists worked to transform individual workers with individual grievances into a collective who came to see themselves as facing a shared injustice that they were willing to take what was ultimately successful collective action over, in the face of counter-mobilization strategies by managers at Northtown University (The Analogue University Citation2019b).

Rachel (whom me met earlier) was a relatively recent arrival at Northtown when the RTB dispute erupted and drew particular attention to it when asked about thehigh points in her working life as a geographer. For Rachel, involvement in anti-RTB action was a way for her to reclaim the sense of geographical vocation which, as we saw above, she felt had been ground down by the instrumentalism of her induction. ‘When RTB was withdrawn it was off the scale', she recounted with pleasure. She felt she was part of a community of ‘people who didn’t just criticize or sympathize but who were willing to put their careers on the line'. Although she highlighted in particular ‘the importance of senior colleagues who had already made it, raising these issues', the resistance was positive because ‘people were actually asking about ideas, not who was funding them’.

Rachel’s narrative highlights the collective aspect of this resistance alongside collective feelings about what a University should be for. During the RTB and pensions disputes, school/departmental meetings played a vital role in organizing mobilization, as did university-wide reading groups and UCU-led discussions. These communities were marked by increased care. Lynch (Citation2010, 57) argues ‘[t]he highly individualised entrepreneurialism that is at the heart of the new academy has allowed a particular ‘care-less’ form of competitive individualism to flourish'. Through academic communities of practice at Northtown, they were able to counter this.

Similarly, Sally is a geography teacher at Northtown Academy who traces her interest in the world and inspiration for the subject to a year out backpacking around the world she spent with her mum as a child. Her year of teaching training was hard, as it was ‘so focussed on getting trained to survive a classroom, not asking how you were coping', she recalled. In contrast, she drew particular attention to the ‘supportive environment’ of her first job. This was characterized by regular check-ins on how she was doing, colleagues taking her out for drinks, and structural support from management. Such collective acts of mutual solidarity over individualism echo accounts of care in the academy illustrated in the literature by geographies and the creation of the slow scholarship movement (Mountz et al. Citation2015; Smyth, Linz, and Hudson Citation2019; Hawkins Citation2019).

6.2. Individual resistance: geography for the social good

Resistance against the deforming effects of neoliberalization on the geographical vocation could be demonstrated by individual choices as well as by participation in collective action.

For example, Simone, an academic with a strong sense of vocation, was highly critical of a number of neoliberal practices in the Northtown University, including policies that saw staff members who were deemed ‘unproductive’ in audits being dismissed in order to employ staff who were deemed better able to help the university succeed against these targets. For Simone, her personal choices about what she researched and how she used this to inform activism within the university and in Northtown more generally helped act as a bulwark against these tendencies. She spoke about how her research had led her to being involved in campaigning to help asylum seekers access education. ‘This is what makes me feel more complete’, trying to ‘bring about change for people who have been marginalised', she explained. ‘It goes against everything that is corporate and horrible within the university’ and ‘it gets me connected into the values that are part of me as an academic’ – values she felt were not reflected in the corporate-style management approach increasingly adopted and favoured by the university’s senior managers.

Pete is a schoolteacher at Northtown Academy. Although not a geography teacher, he has taught cognate subjects and, as a reader of radical geographical writings, self-consciously locates himself within Northtown’s radical tradition. Indeed, he proudly reported that had known someone who had met the great anarchist geographer Petr Kropotkin during his visits to a commune outside Northtown. He gave up better-paid work as a plasterer to become a schoolteacher, he said, because ‘young people from typical working-class backgrounds are short-changed’ and ‘I was naïve enough to think that I could make a difference’. He recounted making a series of choices in his working life that were premised on attempting to keep this purpose in view when schools lost sight of them in the miasma of neoliberalism. He described his unhappiness when the economics syllabus he was teaching shifted emphasis from macro to micro-economics: ‘They wanted people smart enough to be machinists, but dumb enough not to ask why’. ‘I felt I was betraying the kids', in continuing to teach it, he reflected, so stopped doing so. Instead, he increasingly focussed on supporting children who were at risk of exclusion due to behavioural issues. Being successful at this he was given ‘leeway’ by the school management, running after-school activities, philosophy for kids, teaching practical as well as thinking skills, and the like – ‘we were able to do what we wanted', he said, and claimed ‘some considerable success’. He gave an example of one child whose family had been evicted for drug dealing leaving him homeless at age 14. We helped him with teaching practical building skills, Pete said, so he developed these skills and was eventually able to gain financial independence. ‘Now he has a family, income, kids, car, and a home', recounted Pete with evident pride. Spending extra time helping working-class kids disadvantaged by the system rather than teaching curricula he felt were politically compromised by neoliberalism enabled Pete to reclaim that sense of vocation.

Pete said that at some point in the 2000s the success of this work led the management to ask him to roll out wider skills training across the whole school, leading to an improvement in results. However, although ‘the school was pleased, I saw it as disastrous because teachers were involved who weren’t committed', he continued. They were doing it, he said, to improve their performance in league tables rather than out of commitment to the kids – it was ‘essentially cheating’. Therefore, he made a decision to refuse to continue doing it which, as he put it felicitously, ‘went down like a one-legged man in an arse-kicking contest’.

Pete said that this last example shows how target management alters behaviour, as ‘targets themselves become the raison d’etre, everything else becomes secondary'. When this led to what he regarded as practices that significantly undermined the purpose of education, he was willing to take personal action to remain true to that sense of vocation, even if it cost him. ‘What are they going to do, sack me?’ he commented. ‘I’ve been sacked before … It won’t kill you'.

As this section shows, geographers were willing to take action that might be seen as harmful to their careers (going on strike or refusing to engage in practices that play the metrics games) and invest time in building communities of care in order to protect their understanding of what geography is for. Such individual acts of care mirror Al-Hindi’s (Citation2000, 72) call for individuals who have institutional authority to ‘speak up’ rather than support and reproduce the structures that work against building humane workplaces. By so doing, they can resist neoliberalism, and reclaim a sense of vocation.

7. Conclusion

In this article, we have used autobiographical methods to consider what it means to be a geographer, and in doing so offer a novel way of interrogating the effects of neoliberalism. Considering geographers’ autobiographies collectively over time offers a unique way of understanding the creeping impacts of neoliberalism on higher and secondary education geography. We began by exploring autographical accounts written by geographers and how these can be used to think through the effects of neoliberalism. In earlier autobiographies, we noted the description of geography as a vocation and the absence of dynamics that we would describe as neoliberalism. Over time a shift emerged from autographical reflections on why individuals became geographers to who can become geographers and how neoliberalism affects their experiences and practices. Through our use of visual timeline interviews, we developed these autobiographical accounts further and the differing ways in which vocation and what it means to be a geographer changed over the lifetimes of our interviewees. For many of our interviewees, geographical formation is not merely the reasoned ‘choice’ of a ‘career', but is often rather experienced as the result of a compulsion to pursue a vocation. In our interviews, however, neoliberalism in both secondary and higher education geography has led to a significant undermining of this idea of vocation. For instance, increased metrification devalues geography and the meaning ascribed to both researching and teaching geography, and power dynamics inherent within the neoliberal academy value specific types of projects and those who are able to ‘play the game’. However, our data lead us to reject the blanket characterization of geographers’ responses to the neoliberal ‘contemporary situation’ as simply accepting the ‘constraints’ imposed from above. Rather, many geographers are developing individual and collective practices of reforming geography as they seek to counter various manifestations of neoliberalism and reclaim their sense of vocation.

We recognize that a limitation of this study is its lack of focus on how some dimensions of being human (including race, sexuality, religion, (dis)ability, class, ethical convictions and philosophical worldviews) alter what it means to be a geographer. In setting up the literature review of this paper we have highlighted the move from autobiographical accounts that describe geography as a vocation and the absence of neoliberalism in these accounts, to contemporary accounts of becoming geographers in which neoliberalism is central. In these accounts, neoliberalism affects how geography is done and it also affects who can do it. Power dynamics and discrimination are central to both these questions. Cardwell and Hitchen (Citation2022), in discussing experiences of harassment, sexual misconduct, and bullying as early career geographers, argue that while social justice, inequality and power relations are common topics in critical geography, few geographers point out these issues in the academic community itself. They argue that the ‘dependence on the material and social provision of the university’ creates toxic and exhausting relationships with academia, exacerbated by precarity, that compromise ‘social bonds, ethics, or acting communally’ (Cardwell and Hitchen Citation2022). We hope that this intervention paves the way for more work that explores the myriad ways that the process of becoming a geographer and what it means to be a geographer is impacted by power relations and discrimination.

This article suggests that using autobiographical methods to explore the notion of vocation is a productive new contribution to contemporary debates on what is happening to the geographical profession under neoliberalism. We are not advocating vocation as an unproblematic banner under which to rally, as we recognize that it is an historically situated and problematic idea. Gill observes that Back’s advocacy of an ‘elevated sense of vocation’ is one of many responses to the pressures of the neoliberal university, including anarchist refusal, trade union work-to-rule, counselling resilience, and self-help mindfulness. Assaying these options, she comments that ‘I think it is genuinely hard to know how to proceed: how to resist, how to take care of ourselves and each other in all of this’ (Gill Citation2018, 106). We share this sense of uncertainty and awareness of the tensions involved, as do many of our interviewees: indeed Amanda, was our interviewee who spoke most clearly of her work as vocation yet was the most aware of precisely these tensions. Nonetheless, it is striking just how important and productive a sense of vocation was to our respondents, and how it provided an important tool to reflect critically and in some cases frame and mobilize resistance. This leads us to conclude that we should reflect more carefully on how ‘vocation’ can help us think about our working histories and life-courses as geographers.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank James Sidaway, Craig Jones, two anonymous referees, and the editor Richard Ek for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We are grateful to the William Leech Research Fund for supporting the work. Most of all, we would like to acknowledge the time that our interviewees gave us to vouchsafe autobiographical stories of their pursuit of the geographical vocation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acker, S., and C. Armenti. 2004. “Sleepless in Academia.” Gender and Education 16 (1): 3–24.

- Al-Hindi, K. F. 2000. “Women in Geography in the 21st Century. Introductory Remarks: Structure, Agency, and Women Geographers in Academia at the End of the Long Twentieth Century.” The Professional Geographer 52 (4): 697–702.

- The Analogue University. 2019a. “Calling all Journal Editors: Bury the Metrics Pages!.” Political Geography 68 (1): A3–A5.

- The Analogue University. 2019b. “Correlation in the Data University: Understanding and Challenging Targets-Based Performance-Management in Higher Education.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 18 (6): 1184–1206.

- Back, L. 2016. Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters. London: Goldsmiths Press.

- Back, L. 2018. “Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters. London: Goldsmiths Press, “Taking and Giving Hope: A Response to Ros Gill’s ‘What Would Les Back Do?’.”.” International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 31: 111–125.

- Baumeister, R. 1991. Meanings of Life. London: The Guilford Press.

- Beaujeu-Garnier, J. 1983. “Autobiographical Essay.” In The Practice of Geography, edited by Anne Buttimer, 141–152. London: Longman.

- Bellah, R., R. Madsen, W. Sullivan, A. Swidler, and S. Tipton. 2008. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. With a New Preface. London: University of California Press.

- Bhakta, A. 2020. “Which Door Should I Go Through?” (In)Visible Intersections of Race and Disability in the Academy.” Area 52 (4): 687–694.

- Bonnett, A. 2008. What is Geography? London: Sage.

- Buttimer, A. 1983a. “Introduction.” In The Practice of Geography, edited by Anne Buttimer, 1–19. London: Longman.

- Buttimer, A. 1983b. The Practice of Geography. London: Longman.

- Cardwell, E., and E. Hitchen. 2022. Intervention – “Precarity, Transactions, Insecure Attachments: Reflections on Participating in Degrees of Abuse”. Antipode Online. https://antipodeonline.org/2022/01/06/precarity-transactions-insecure-attachments/.

- Caretta, M. A., D. Drozdzewski, J. C. Jokinen, and E. Falconer. 2018. “Who Can Play This Game?” The Lived Experiences of Doctoral Candidates and Early Career Women in the Neoliberal University.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (2): 261–275.

- Champagne, M. 2016. “Diagrams of the Past: How Timelines Can aid the Growth of Historical Knowledge.” Cognitive Semiotics 9 (1): 11–44.

- Chell, E. 2004. “Critical Incident Technique.” In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research, edited by C. Cassell and G. Symon, 45–60. London: Sage.

- Corney, G. 2000. “Student Geography Teachers’ Pre-Conceptions About Teaching Environmental Topics.” Environmental Education Research 6 (4): 313–329.

- Daley, P. 2020. “Lives Lived Differently: Geography and the Study of Black Women.” Area 52: 794–800.

- Daniels, S., and C. Nash. 2004. “Lifepaths: Geography and Biography.” Journal of Historical Geography 30: 449–458.

- Driver, F. 2013. “Hidden Histories Made Visible? Reflections on a Geographical Exhibition.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38: 420–435.

- Flanagan, J. 1954. “The Critical Incident Technique.” Psychological Bulletin 51 (4): 327–358.

- Franco-Santos, M., and N. Doherty. 2017. “Performance Management and Well-Being: A Close Look at the Changing Nature of the UK Higher Education Workplace.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 28 (16): 2319–2350.

- Gill, R. 2010. “Breaking the Silence: The Hidden Injuries of the Neoliberal University.” In Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections, edited by R. Ryan-Flood, 228–244. London, UK: Routledge.

- Gill, R. 2018. “What Would Les Back Do? If Generosity Could Save Us.” International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 31: 95–109.

- Gould, P. 1999. Becoming a Geographer. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Greenwood, D. J., and M. Levin. 1998. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change. London, UK: Sage.

- Hägerstrand, T., and A. Buttimer. 1988. Geographers of Norden. Lund: Lund University Press.

- Harland, T., A. McLean, R. Wass, E. Miller, and K. N. Sim. 2015. “An Assessment Arms Race and its Fallout: High-Stakes Grading and the Case for Slow Scholarship.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (4): 528–541.

- Hartman, Y., and S. Darab. 2012. “A Call for Slow Scholarship: A Case Study on the Intensification of Academic Life and its Implications for Pedagogy.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 34 (1–2): 49–60.

- Hawkins, H. 2019. “Creating Care-Full Academic Spaces? The Dilemmas of Caring in the ‘Anxiety Machine’.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 18 (4): 816–834.

- Hawkins, R., M. Manzi, and D. Ojeda. 2014. “Lives in the Making: Power, Academia and the Everyday.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 13 (2): 328–351.

- Hooks, b. 2009. Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. London: Routledge.

- Johnston, R., and J. Sidaway. 2016. Geography and Geographers: Anglo-American Human Geography Since 1945. 6th ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jones, M. 2018. “Anne Buttimer's The Practice of Geography: Approaching the History of Geography Through Autobiography.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 100 (4): 396–405.

- Kalfa, S., A. Wilkinson, and P. J. Gollan. 2018. “The Academic Game: Compliance and Resistance in Universities.” Work, Employment and Society 32 (2): 274–291.

- Kearns, G. 2016. How I Became a Historical Geographer. https://historicalgeographyresearchgroup.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/hgrg-newsletter-autumn-2016.pdf.

- Keddie, A., and B. Lingard. 2015. “Navigating the Demands of the English Schooling System: Problematics and Possibilities for Social Equity.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 19 (11): 1117–1125.

- Kidwell, J. 2016. The Theology of Craft and the Craft of Work: From Tabernacle to Eucharist. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lakes, R. D., and P. A. Carter. 2011. “Neoliberalism and Education: An Introduction.” Educational Studies 47 (2): 107–110.

- Legge, K. 2005. Human Resource Management: Rhetorics and Realities. Anniversary Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lynch, K. 2010. “Carelessness: A Hidden Doxa of Higher Education.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 9 (1): 54–67.

- Mansfield, B., R. Lave, K. McSweeney, A. Bonds, J. Cockburn, M. Domosh, T. Hamilton, R. Hawkins, A. Hessl, D. Munroe, et al. 2019. “It's Time to Recognize How Men's Careers Benefit from Sexually Harassing Women in Academia.” Human Geography 12 (1): 82–87.

- Mason, Olivia, and Nick Megoran. 2021. “Precarity and Dehumanisation in Higher Education.” Learning and Teaching 14 (1): 35–59. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2021.140103.

- Massey, D. 1991. “A Global Sense of Place.” Marxism Today 38: 24–29.

- Mazzetti, A., and J. Blenkinsopp. 2012. “Evaluating a Visual Timeline Methodology for Appraisal and Coping Research.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 85: 649–665.

- McDowell, L., and L. Peake. 1990. “Women in British Geography Revisited: Or the Same Old Story.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 14 (1): 19–30.

- Megoran, N. 2019. Human Resources? Recognising the Personhood of Workers in the Charity and Public Sectors. Newcastle: Newcastle University/William Leech Research Fund.

- Megoran, N., and O. Mason. 2020. Second Class Academic Citizens: The Dehumanising Effects of Casualisation in Higher Education. London: University and College Union.

- Morrish, L., and The Analogue University. 2017. “Academic Identities in the Managed University: Neoliberalism and Resistance.” Australian Universities Review 59 (2): 23–35.

- Moss, P. 2001. Placing Autobiography in Geography. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Mountz, A., A. Bonds, B. Mansfield, J. Loyd, J. Hyndman, M. Walton-Roberts, R. Basu, et al. 2015. “For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance Through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (4): 1235–1259.

- Navarro, T. 2017. “But Some of us are Broke: Race, Gender, and the Neoliberalization of the Academy.” American Anthropologist 119 (3): 506–517.

- Noxolo, P. 2017. “Introduction: Decolonising Geographical Knowledge in a Colonised and re-Colonising Postcolonial World.” Area 49 (3): 317–319.

- Okoye, V. O. 2021. Supervising Black Geography PhD Researchers in the UK: Towards Good Practice Guidelines. https://raceingeographydotorg.files.wordpress.com/2021/09/report_supervising-black-phd-researchers-in-geography-v3.pdf.

- Pain, R. 2004. “Social Geography: Participatory Research.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (5): 652–663.

- Pain, R., M. Kesby, and K. Askins. 2011. “Geographies of Impact: Power, Participation and Potential.” Area 43 (2): 183–188.

- Purcell, M. 2009. “Autobiography.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by Nigel Thrift and Rob Kitchin, 234–239. London: Elsevier.

- Sauer, C. O. 1956. “The Education of a Geographer.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 46 (3): 287–299.

- Shahjahan, R. A. 2014. “From ‘No’ to ‘Yes’: Postcolonial Perspectives on Resistance to Neoliberal Higher Education.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 35 (2): 219–232.

- Sidaway, J. D. 1997. “The Production of British Geography.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22 (4): 488–504.

- Slater, T. 2012. “Impacted Geographers: A Response to Pain, Kesby and Askins.” Area 44 (1): 117–119.

- Smyth, A., J. Linz, and L. Hudson. 2019. “A Feminist Coven in the University.” Gender, Place & Culture 27 (6): 854–880.

- Tate, S. A. 2014. “Racial Affective Economies, Disalienation and ‘Race Made Ordinary’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 2475–2490.

- Thomas, N. 2016. How I Became a Historical Geographer. https://historicalgeographyresearchgroup.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/hgrg-newsletter-summer-2016.pdf.

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P. 2017. “A day in the Life of a Geographer: ‘Lone’, Black, Female.” Area 49 (3): 324–328.

- Townsend, J. G. 1995. Women's Voices from the Rainforest. London: Routledge.

- Tschudi, A. B., and A. Buttimer. 1983. “Worlds Apart.” In The Practice of Geography, Edited by Anne Buttimer, 35–61. London: Longman.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1999. Who Am I? An Autobiography of Emotion, Mind, and Spirit. London: University of Wisconsin.

- University and College Union. 2019. Counting the Costs of Casualisation in Higher Education. https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/10336/Counting-the-costs-of-casualisation-in-higher-education-Jun-19/pdf/ucu_casualisation_in_HE_survey_report_Jun19.pdf.

- Volf, M. 2001. Work in the Spirit: Towards a Theology of Work. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock.

- Weber, M. 2004. “Science as a Vocation.” Translated by Rodney Livingstone. In The Vocation Lectures, edited by David Owen and Tracy Strong, 2–31. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

- Whyte, W. F. 1994. Participant Observer: An Autobiography. Ithaca, NY: IRL press.

- Wæraas, A., and M. N. Solbakk. 2009. “Defining the Essence of a University: Lessons from Higher Education Branding.” Higher Education 57: 449–462.

- Yin, R. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5th ed. London: Sage.