ABSTRACT

Reappraisal of the local and living a rooted life are often highlighted by international advocates for sustainable and environmentally conscious lifestyles. The purpose of this study is to explore and theorize downshifters’ lifestyle changes, with a particular focus on their living environments and sense of place, and we draw on a theoretical framework that combines insights from previous research on downshifting and voluntary simplicity. We conducted 30 life story interviews with individuals in Sweden who consider themselves downshifters or advocates of a simpler life. These materials were analysed along the dimensions of (1) spatial adaptation and appropriation; (2) local and global scales; and (3) temporality of place. Our results emphasize the non-linearity of lifestyle changes towards simplicity where, whereby commitment to sustainability varies while personal goals rely on the previous experiences and everyday practices, values and knowledge that can improve both individual and global sustainability. Our analysis shows that sense of place is a dynamic process influenced by mobilities and flows, spatial inertia and context, and memories and emotions. Our research contributes to the recent more than- relational view on space and place with concepts from humanistic geography that further assist in understanding individuals’ sense of place.

Introduction

Research on sustainable lifestyles addresses the role of environmentally conscious everyday practices and consumption decisions of individuals and groups (Barr and Gilg Citation2006; Barr, Shaw, and Coles Citation2011; Longo, Shankar, and Nuttall Citation2019; Echegaray et al. Citation2021). Within this research, studies on downshifting and voluntary simplicity have been gaining growing scientific attention in relation to an increased striving for sustainable lifestyles, concern about overconsumption and human impacts on the globe. Dating back to the 1960s and 1970s (Meadows et al. Citation1972; Carson Citation2013), a general awareness of the negative consequences associated with high materialism in countries with well-established economies has recently increased. These studies – mainly concentrating on consumption patterns, individual values of environmental and social responsibility, self-sufficiency and reduction of working hours (Etzioni Citation1998; Alexander and Garrett Citation2017; Rebouças and Soares Citation2020) – lack grounding in the spatial attributes, localities and place-related prerequisites that would allow sustainable lifestyles to be successfully carried out.

Therefore, this paper aims to identify pivotal themes in the lives of individuals who identify themselves as downshifters and voluntary simplicity seekers. We study the role of place and sense of place for the individuals and in the identified pivotal themes. As the studied downshifting and voluntary simplicity-seeking processes are non-linear, the individual’s place attachment is dynamic as it unfolds in the studied processes. This leads us to a reappraisal of local place-related attributes, which can support individuals and societies in their move towards more sustainable living.

In this paper, we analyse in-depth interviews with individuals in Sweden who have voluntarily decided to downshift and live a simpler life. Analysing how these individuals describe their personal experiences of this transition, we engage with existing definitions of downshifting and voluntary simplicity, which have previously been described as ‘cousins’ (Etzioni Citation1998). We suggest a more specific definition based on a close integration of the two concepts, in which downshifting is approached as a voluntary process of individual social mobility towards an end-goal of simplicity, with consumption and other practices reduced to sustainable levels. In this sense we argue against the claim by Lindsay, Lane, and Humphery (Citation2020) that downshifting does not actually reduce consumption and lead to sustainability. Our definition reflects strong individualistic motivations for this kind of lifestyle transition, which unfolds over the life course and therefore might be difficult to measure in a certain timeframe. We claim that, even though downshifting processes are seldom linear paths towards sustainable lifestyles (including temporary deviations towards higher levels of consumption and pollution), this is still a transition that inspires and finds its way to simplicity and sustainability.

A novel aspect in this study is the inclusion of geographic perspectives in the analysis of downshifting and voluntary simplicity. This is mainly done through the concept of place, understood as ‘a meaningful location [that] people are attached to in one way or another’ (Cresswell Citation2014, 7). In this way, we ground our study in the humanistic tradition of sense of place, as it strongly resonates with the positive emotional attachment that individuals can have to a place. Creating place attachment is a dynamic, evolving process that includes mitigation and adaptation to local qualities and prerequisites that individuals assign to different localities (Devine-Wright and Quinn Citation2020). Following an interpretation of humanistic geography, in which human physical and emotional relationships with their surroundings are seen as fundamental to their existence, this holistic approach sees people and places as intimately connected (Rodaway Citation2004, 306). Thus, being-in-the-world and human-environment relationships are explained as not merely objective and material but also essentially affective and moral. Here, the study leans towards a ‘more-than-relational’ view on space (Allen Citation2012; Jones Citation2022), emphasizing the contextual specificities, and the temporal dimensions of how a place is constructed together with the relations that reach a place across time. Di Masso et al. (Citation2019) have outlined how both fluid and fixed elements in a place together form the basis for an individual’s place attachment, in which both objects and discourses in a place as well as personal mobility and an individual’s life changes are constituents. Suggesting that a humanistic perspective on place can be further integrated into a ‘more-than-relational’ view on space and place (Allen Citation2012; Jones Citation2022), we draw on humanistic understandings of ‘sense of place’ to study how people connect to places and how these connections shape and are shaped by thought, emotions and behaviour (Tuan Citation1974; Diener and Hagen Citation2022). Accordingly, we see places as shaped by not only relations and material objects but also emotions and discourses that remain as layers in a place across time (Massey Citation1995). This can gainfully be attached to the current reappraisals of local processes among downshifters in Sweden.

The remainder of the paper is divided into five sections. First, we explain our conceptual framework and present literature on downshifting and voluntary simplicity, connected to geographic perspectives on space and place. Next, we discuss our methodology and then present the results. We then analyse downshifting processes in relation to the studied senses of place. The final section concludes the study and indicates topics for future research.

Downshifting, voluntary simplicity and senses of place

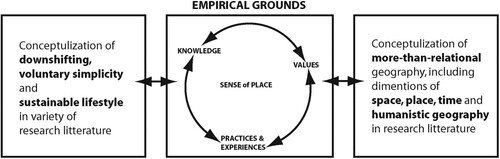

Throughout this study the empirical and theoretical understanding of the subject matter has developed in parallel, taking its baseline from ethnographic studies (Crang and Cook Citation2007). summarizes our thinking process, in which the main empirical emic categories have been compared and developed with the help of literature on downshifting, voluntary simplicity and sustainability on the one hand, and conceptualizations of place, space and time on the other.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for our analysis, based on empirical grounds while being informed by conceptualizations of sustainable lifestyles and place-related theorizations.

We focus on individuals’ changing values and everyday practices in relation to personal, social and environmental sustainability in downshifting and voluntary simplicity (Osikominu and Bocken Citation2020; Rebouças and Soares Citation2020). All three categories in represent the temporality and dynamic nature of downshifting. We add theoretical and practical knowledge as important factors in these lifestyle changes (Hobson Citation2003; Clarkson, Janiszewski, and Cinelli Citation2013; Longo, Shankar, and Nuttall Citation2019), and link this to sense of place in the centre of the empirical foundation to indicate the geographic perspectives that constituted our primary research interest prior to our fieldwork. In this way, we enrich the conceptualization of downshifting and voluntary simplicity both in how daily practices are emerging and in how values and access to knowledge are being shaped. To this, we add current debates in human geography that reconsider unique, contextual and temporal relations in a place and notions of locational specificity, in addition to an awareness of how relations are intersecting in places and contributing diversity (Jones Citation2009, Citation2022; Pierce, Martin, and Murphy Citation2011). This provides the conceptual basis for thematically analysing downshifting and voluntary simplicity processes, including heterogeneous experiences of lifestyle changes towards less commercial purposes, which is further discussed when we present our findings.

Lifestyle changes: practices, values and knowledge

Downshifting is often instigated by individualistic work- and health-related motivations like escaping the rat race, recovering from burnout, or solving clashes between personal and workplace values (Breakspear and Hamilton Citation2004). Etzioni (Citation1998) categorized downshifting as a moderate lifestyle change in which people give up some luxuries and perhaps work less, but with little reduction in overall consumption levels. Downshifting also captures a focus on quality of life as opposed to status derived from work and income (Rich, Hanna, and Wright Citation2017; Rich et al. Citation2017). Recognizing that people are happier in the long run if they like what they do for a living rather than working ‘for the paycheck’ or performing work on a level with their education, downshifting has been conceptualized as a ‘low-keyed trend’ (Popcorn Citation1991, 223). Such lifestyle changes were initially studied in the UK, the USA and Australia with a focus on economy, psychology, leisure and migration (Schor Citation1998, Citation2005; Juniu Citation2000; Tan Citation2000; Hamilton Citation2003; Hamilton and Mail Citation2003). Since gaining control over one’s time is an important aspect of both downshifting and voluntary simplicity (e.g. Alexander and Ussher Citation2012; Lindsay, Lane, and Humphery Citation2020), both fields have recently been connected to reduced worktime and consumption, but less to geographic perspectives (Nässén and Larsson Citation2015; Paulsen Citation2017; Rebouças and Soares Citation2020; Persson, Larsson, and Nässén Citation2022).

Some argue that voluntary simplicity goes further than downshifting, as the former not only rejects consumption and material values of greed, acquisitiveness, luxury and excess, but also actively and knowingly involves spiritualism, ecological responsibility and resistance to high-consumption lifestyles (Alexander and Garrett Citation2017; Kennedy, Krahn, and Krogman Citation2013; Rich, Hanna, and Wright Citation2017; Rich et al. Citation2017). Such studies seldom include less well-off groups living in forced poverty (Kala, Galčanová, and Pelikán Citation2017), but rather well-educated and economically well-off individuals whose basic needs are met and who voluntarily adopt these lifestyle changes while living in Western societies (Etzioni Citation1998; Alexander and Garrett Citation2017; Kennedy, Krahn, and Krogman Citation2013; Demetry, Thurk, and Fine Citation2015). Voluntary simplifiers are often seen as political actors (Alexander Citation2011) and important carriers of anti-consumerist and pro-sustainability values (Osikominu and Bocken Citation2020). Motivations for voluntary simplicity stem from a process of changing intrinsic values, wellbeing and personal growth, combined with deliberate choices to increase personal, social and environmental sustainability (Rebouças and Soares Citation2020). One seminal text described voluntary simplicity as a ‘way of life that is outwardly simple, inwardly rich’ (Elgin Citation1993, cover).

Moreover, consumption studies have identified individuals’ knowledge as a relevant theme. This has been analysed in relation to sustainability perspectives in order to investigate how levels of theoretical or practical knowledge influence lifestyle choices (Hobson Citation2003; Clarkson, Janiszewski, and Cinelli Citation2013; Longo, Shankar, and Nuttall Citation2019). The ability to construct knowledge based on relevant information plays important enabling and hindering roles in turning intentions of sustainable living into sustainable behaviours (Longo, Shankar, and Nuttall Citation2019). As this point has not been sufficiently emphasized in earlier downshifting and voluntary simplicity literature, this article considers the extent to which knowledge can be added to the dimensions that contribute to our respondents’ lifestyle changes towards downshifting and voluntary simplicity.

Spatiality, sense of place and time

This paper searches to further understand the spatial implications of a lifestyle transitioning process such as downshifting. We believe that downshifting is related to space in at least two central ways: on the one hand, space is constructed of mobilities and flows, and the relations that intersect with space (Massey Citation2005; Cresswell Citation2010); and on the other hand, the possibilities that are provided by a place contain important dimensions of time, context and inertia (Jones Citation2009; Citation2022), approaching geography as ‘bounded but relationally connected’ (Jones Citation2022, 2). Attached to the empirical case, our idea is that downshifters are related to place in at least three ways: First, they are influenced both by external relations to other places, such as the spatial interactions that have been highlighted in transition lifestyles (Nicolosi and Feola Citation2016), and by internal relations, objects and discourses within the places where they reside. Second, the downshifting process affects their own sense of place. Third, the place as a container where they perform their downshifting process, by producing materialities, networks and discourses.

This perspective is based on a more-than-relational view on space. Essentially, this means that relations that intersect in space leave distinct footprints, as layers in time, which contain their own internal power structures. These inertial capacities of space are what Jones (Citation2022, 12) calls a plastic space that is ‘not rigid and determined, but instead always contingent upon the context within which it unfolds, and thus always evolving and becoming’. Through our empirical analysis of downshifting individuals, however, we recognize that a more-than-relational view on space assigns particular emphasis on the material footprints that influences leave in a place, and which remain as layers in time (Massey Citation1995), rather than on the fluid perspective of space as always under construction through intersections of relations.

In order to further theorize the place where relations meet, we suggest that a more-than-relational space be grounded in the classical findings of humanistic geography. We especially emphasize the personal, emotional affection that, so far, has not been emphasized much in more-than-relational views on space. This perspective has evolved since the 1970s in parallel with human concerns for the environment, emphasizing human perceptions of the environment based on meanings, values, goals and purposes related to spatial psychology (Tuan Citation1976). We find that the environmental associations and values that humanistic geography carries are pertinent to the further theorization of downshifting and its spatiality. Tuan views place as ‘combining the sense of position within society […] with the sense of and identity with spatial location that comes from living in and associating with it’ (Agnew, Livingstone, and Rogers Citation(1996) 2005, 444). Described as ‘a centre of meaning or a focus of human emotional attachment’ (Entrikin Citation1976, 616), Tuan sees place as ‘a unique amalgam of prolonged interactions between nature (as physical fundament) and humans’ (Agnew, Livingstone, and Rogers Citation(1996) 2005, 445–447). People perceive and experience this amalgam via various senses of place.

Tuan (Citation1974) differentiates between visual or aesthetic senses and other senses (hearing, smell, taste and touch). A visual sense of place needs a trained eye, but contributes rather quickly and explicitly to perceptions of a location (even from a distance), while the other senses require close contact and long association with the environment to construct more profound senses of place that can be hard to capture in words. Relph (Citation1976) conceptualized people’s varying degrees of insideness as feeling enclosed rather than exposed and at ease rather than stressed, and outsideness as feeling alienated from a place (Seamon Citation1996, original italics). Senses of place thus contribute to subconscious knowledge creation and development, which people demonstrate when they apply their moral and aesthetic values to sites and locations (Agnew, Livingstone, and Rogers Citation(1996) 2005, 445–447).

When adding this emotionally loaded sense of place to a more-than-relational view on space, Di Masso et al.’s (Citation2019) perspective on how mobilities and fixities in a place together shape the place that individuals perceive is useful. This idea inserts mobilities, migration and possibly traumatic changes to places in the classical approach of static and rooted place attachment. It suggests that ‘place attachments are not inherently stable psychological constructions, but rather are informed across time and space by an array of mobility conditions and the relational configurations that underpin them’ (Di Masso et al. Citation2019, 131). For the individuals, this approach combines the time-restricted experiences of different places and remaining relations to these places with the layers of creating an attachment to and a sense of the current place of residence.

Summing up this discussion, we reckon that the spatial analysis of individuals in their downshifting processes – which could also be stretched to analyse other individuals and communities in their local settings – can be conducted according to the following themes: (1) spatial adaptation and appropriation, which takes into account the emotions, memories and uniqueness of a place; (2) local and global scales, recognizing how places and the individuals inhabiting them are influenced by both global and local connections; and (3) the temporality of place, which recognizes how past, present and future dimensions are interlinked in the individual’s relation to place(s). In this paper, we will use this thematic division for the spatial analysis of the downshifting process.

Methods and material

Data gathering

The data collection and analysis focus on how someone with personal experiences of the phenomenon in question explains its essence (Creswell and Poth Citation2018). Focusing on individual experiences and explanations of downshifting and voluntary simplicity, we conducted life story interviews with individuals who consider themselves downshifters or voluntary simplifiers. Our study has got ethical approval from Swedish Ethical Review Authority, doc nr 2019-06354. Voluntary participation was based on informed consent, and informants shared their experiences and reflections regarding their decision processes towards downshifting and voluntary simplicity.

The study draws on interviews conducted at the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic forced us to limit social contact. As such, the data were gathered before the outbreak (in Sweden) but were analysed during the pandemic, when pro-rural living to escape urban population density intensified (Eimermann, Hedberg, and Nuga Citation2020; Sandow and Lundholm Citation2020). This paper is timely, as it analyses pre-pandemic trends and personal reflections on sustainable living just before they became even hotter topics.

We employed snowball sampling with a twist (Parker, Scott, and Geddes Citation2019). We started recruiting participants at the Swedish transition movement’s annual conference in Umeå in 2019. Participants also contacted us at their own initiative after learning about the project through various media. These two entry points were followed by classical snowball sampling in which initial participants spread the word to their peers. However, we found most participants through announcements in thematic Facebook groups and other social media (Kosinski et al. Citation2015). While this implies a possible bias as those with a shyer nature did not contact us, we managed to gather people who were happy to share their experiences and ideas, which is essential for a qualitative study. Thus, the material unveils deep reflections regarding individual changes in lifestyle.

All but two interviews were carried out in the informants’ places of residence in order to better understand their living conditions and everyday experiences, but also to make them feel comfortable and respected. The interviews lasted one to three hours and were conducted in Swedish by Mari Nuga. The semi-structured interviews started with warm-up questions like ‘please explain how you picture a good life’ and ‘do you think you live accordingly?’. The interview guide further contained concrete questions about lifestyle, migration, place, economy, social relations, health and sustainability. At the same time, the interviewer encouraged informants to lead the course of the conversation depending on what kind of planned or additional topics they found more important or applicable. At the end of the interview, the participants filled in a brief questionnaire with background information.

The interviews were transcribed and coded both inductively and deductively (Crang and Cook Citation2007, 140). Inspired by Rebouças and Soares (Citation2020), we identified themes related to the theoretical questions regarding the variety of motivations, engagements and arrangements in the process of downshifting towards voluntary simplicity. We relied on the participants’ accounts to create thick and subjective descriptions of the themes without seeking to generalize findings. In references to participants in this paper pseudonyms are used, followed by the participant’s age.

Participant profiles

Summarized in , this sampling resulted in 30 interviews with altogether 46 individuals (29 women and 17 men). Eight interviewees were not cohabiting, 15 interviews were carried out with adults living together, and 18 households included children currently living at home. More than 80% of the participants had a higher education (i.e. at least three years of completed university studies or equivalent).

Table 1. Participant profiles.

Most participants earned a salary through wage labour, working 20% to 75% of full-time. They worked as teachers, journalists, writers, environmental scientists, psychologists, economists, artists, IT specialists and medical caretakers, as well as in other professions. All of them earned an income in other ways as well, through either self-employment, social or study benefits, or as passive income (from renting out real estate, receiving book royalties or investing in stock dividends). The point in life at which a participant diminished his or her work hours and downshifted is measurable for 19 individuals. Others have never had full-time employment, still work full-time periodically, or have gone back and forth with more or less time for work. There were no households in which both partners worked full-time at the time we interviewed them, but in 13 interviews one partner did. Most participants are white (Swedish and European) middle class, while some are working class.

To simultaneously vary and limit the geographical spread of the study, we focused on two regions in Sweden: urban and rural parts of Västra Götaland in the southwest, and Västerbotten in the north. Eight interviews were conducted in Västerbotten’s regional capital of Umeå, and four in and around Västra Götaland’s regional capital city of Gothenburg. Umeå and Gothenburg differ in size and population composition, but both are equal in the sense that they are the largest and most urban settlement in their respective region. Other interviews took place both in villages with relatively high population density and in more solitary places with some hundred metres’ distance between houses. The participants’ houses included detached houses, country houses, townhouses, apartments and tiny houses on wheels. Regardless of housing type or tenure, however, many participants pondered about the pros and cons of rural ways of living and the significance of social and physical environments for their lifestyle changes. For instance, about half of them produced at least some of their food themselves and six had livestock. We relate this to the empirical results, senses of place and place identity below.

Temporal perspectives in downshifting

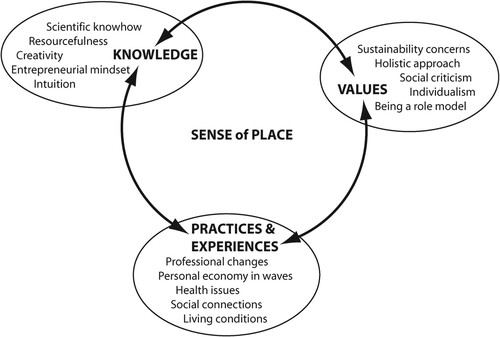

In relation to our interviewees, we identified the themes of practices/experiences, values and knowledge as central to their understanding of downshifting (). The themes were temporal in nature, changing in time and intertwined; for example, practices can be informed by knowledge and formed by values, or practices can help in gaining new knowledge, which in turn can lead to a re-evaluation of values.

Figure 2. Themes, subthemes and connections that characterize the variety of engagement and relation to the place in downshifting towards voluntary simplicity.

Practices and experiences

Participants described a wide variety of professional changes in relation to their downshifting and employment. These included (1) changing jobs, (2) reducing work time and/or assignments within the same job, (3) attaining new education and (partly) changing professional fields, (4) becoming self-employed in the same professional field, (5) becoming self-employed selling handwork, artwork, books, or products from the garden, (6) being self-employed but changing business plans, (7) downshifting due to health problems and (8) living mainly on health benefits. Many such changes were performed either simultaneously or subsequently, often following personal reflections and consultations with significant others in regard to what it means to ‘live more according to one’s values’ (Ulf, 60). The primary purpose was to gain time for other valued activities in life, in line with previous studies (e.g. Etzioni Citation1998).

Some participants valued their professional contribution within the downshifting process as particularly important. Finding meaningful, but still professional, practices that resonated with their personal and environmental sustainability values (rather than with a prominent need to earn an income) was essential. Carina (51), having stopped working as a schoolteacher some years earlier because she had become overwhelmed by the high demands at work had lived on the edge of burnout and felt she could not manage her work/life balance, explained:

I get up at six o’clock and start writing my new book. I’m also reading articles from medical journals about women’s health. Very interesting. I read and write for a few hours and then I often go and meet someone. Last Monday I had lunch with a politician. The day before I had a book presentation at the library, and I met very exciting people. The weekend before that I was in a town about 200 km from here and had a workshop where I taught the participants to make butter from scratch. I’m still working through meeting people and sharing knowledge like I used to do as a teacher. (Carina, 51)

These multiple work-and-income-related options in the participants’ downshifting processes also imply that this is seldom a one-way process leading to a final lifestyle. Instead, many participants reported multiple waves of downshifting (and ‘upshifting’) over their life course, with their personal economy fluctuating in waves. The main reason for this was that their chosen alternative practices had grown into time-demanding jobs and they had felt the need to slow down again. Other fluctuations resemble seasonal workers’ lifestyles, with a person deliberately working and earning a great deal during high season (e.g. in tourism) and working less or not at all during other seasons. In both longer- and shorter-term cycles, periods of intensified work were alternated with periods of lower activity. For instance, Malin (50) had run a café in an open-air museum during the summer and attended university courses or travelled during low season. She became ‘overworked and ill for a while’ and found a new job as a caretaker at a church, but resigned due to conflicts. This is an example of the flexible attitudes and variety of work and income sources that were very common among the participants.

While Carina illustrates the more common experience of burnout among downshifters, Malin’s example shows that health issues can occur and serve as an extra reminder even when a person already lives a simpler life. Health issues are related to tendencies of overworking and burning out, sometimes due to social issues at the workplace but sometimes due to gradually developed chronic symptoms that, according to the participants themselves, have little or nothing to do with overworking. Having emerging health issues or learning about other people’s physical or mental problems have been important trigger points in many participants’ lifestyle changes. Many participants related lifestyle changes for avoiding or coping with illness to their value changes, including alternative income, increased interest in learning about sustainability, and reflections on their place of residence. For Susanne (37), the process of downshifting offered a possibility to re-evaluate her chronic disease, which had forced her to stop working. The experience of illness had placed the focus on what Susanne valued in life, connecting practices and experiences with values:

This meant a lot less income than we had planned for, and we had just built our new house. […] In social media, I found inspiration from people who had wanted to get out of the rat race, how they gave up so many things but were nevertheless happy. I saw that it can function this way. […] My husband and I got into this mindset and focused on things that made us happy: mainly social gatherings. (Susanne, 37)

This brings us to various meaningful social connections. Susanne had become a mother and had moved to a new place close to her husband’s family just before her health issues started. Although she did not connect her motherhood and choice of place of residence with a need to downshift, she regarded her in-laws living close by as a source of essential support and relief in her process. Mia (37), another young mother who lived with her husband and young child in a tiny house in their friends’ backyard, felt that their family relations were stronger than those with many friends (with similar values) who lived nearby. They planned to move soon and search for a house near some of their relatives: ‘I’m very family-loving; I want to be able to spend a lot of time with them, wherever they are’.

Camilla (44) and Mattias (47) feel that meaningful local connections are as important as family connections. They had lived near Camilla’s relatives, but felt at odds with the local countryside culture there. After moving away, they have maintained close contact with their relatives while enjoying the social relations in their new environment:

I think it’s very important to also have people close by whom I feel close to. We have some people here, but that’s something I could always have more of. (Camilla, 44)

To these place-related social connections, participating individuals, couples and families added everyday living conditions as crucial elements in their downshifting processes. For Camilla and Mattias, a desire to test living in their self-built ecological house amid powerful natural scenery and not simply use it as a second home (as they had done before) was the main reason they settled in their current place of residence. Although our participants’ houses and living arrangements varied in size and type, they linked such conditions with ways of creating a home and practical opportunities for downshifting. Participants provided examples, saying for instance that changing a lawn into a potato field can provide future nourishment (or fail to do so) in similar ways as inviting a neighbour for coffee for the first time can start a new social connection (or disagreement). Carina has recreated her urban garden and home according to her aspirations:

My dream of rural life just feels impossible because it costs money to buy a farm and you need so much knowledge to start running a farm. […] I would need to persuade the whole family, because everyone should want it. But I’ve learned that I can live a rural lifestyle right where I live, in the middle of town. (Carina, 51)

This indicates how participants relate practices and experiences involving living conditions to economic (im)possibilities to downshift, and how they considered their environment to be physically and socially amenable to various degrees.

Values

The process of downshifting often involved major changes in values, which also influenced participants’ lifestyles. As pivotal drivers, they mentioned ecological responsibility and long-term environmental sustainability concerns with a main focus on decreasing their consumption. Driven by practical and value-related sustainability concerns, Karin (54) and Ulf (60) keep domestic animals from native breeds: cows, sheep, chicken and bees. Where they live, they let the animals graze on pastures along the coast:

Everything we do has climate thinking […] but also other aspects. There’s biological diversity, and cultural diversity if such a coastal environment disappears. So, we read a lot and think about this when it comes to animals. How should we keep the animals? And trying to find an argument that feels good for us to still have them. (Karin, 54)

From a climate point of view, it would be possible to have fewer animals. Fifteen or 10 animals would meet our meat needs. But it wouldn’t go together with our cultural-historical ambitions, or with what we think is important. For us, biodiversity is as important as the climate. We have 50 animals to maintain the cultural history and biodiversity. Because that’s what the impact is without a climate argument. (Ulf, 60)

Karin and Ulf engage in debates about domestic animals having ‘the worst climate impact’, leading to dilemmas between different aspects of sustainability that they value as important. They have chosen to consider cultural history and biodiversity, even though this might affect the climate badly due to the carbon dioxide and methane that the animals produce. For them it is an important daily activity to discuss and re-evaluate their sustainability actions with each other based on updated scientific knowledge and their own ability to act.

This fits with a holistic approach including ecological, cultural, social and personal considerations that vary between different participants and change over the life course. The analysis identified a search for personal and planetary balance and wellbeing as a common goal. For instance, Silvia (56) has a diverse professional path, having first worked as a farmer without a secondary education and then attending and passing courses to become a psychologist when she was 40. She linked this with personal health, how much a person can handle in a day, and finding motivation in life:

I’ve been a small-scale milk producer and it became literally backbreaking to survive, as I had to work more and more for less and less income. I think I stopped so I could adapt to society (the way it is today) and try to realize my own thoughts about what a good life is. For me, it’s always been important to try to have a holistic approach and a sensible use of resources. We use so incredibly much of the earth’s resources in the rich countries, so that it doesn’t feel balanced or sensible at all. (Silvia, 56)

This quote also indicates social criticism among downshifters and challenging ways of ‘being in the world’ when trying to achieve structural change while simultaneously adapting to society at large. As a farmer, Silvia had experienced how big corporations were ‘eating up’ small-scale producers. She accepted this, but also criticized large-scale production for being more polluting and wasteful of the planet’s resources. Per (38) added social justice and global uneven development and opportunities to these concerns:

In no way do I think it feels morally right that we live as we do [in Western society]. We cause nature and people so much suffering: everyone who starves and is affected by war. We in the Western world will probably be affected last. […] There are so many people who get hurt because of these systems that we’ve built up […] and I think that’s a disaster. (Per, 38)

Per realized that he was not in a position to combat all social injustice and geographic unevenness, which felt ‘very heavy’. He wanted to somehow accept this while also trying to make as fair everyday choices as possible.

The analysis identified individualistic ways of enjoying things and practices that ‘feel right’. Like Per, most participants primarily focused on their own lives, trying to be true to themselves while at the same time hoping that their admittedly selfish choices live up to their overall sustainability concerns. Many participants worried that their own mental health may decline because of their anguish over their own, mankind’s, and the Earth’s future. However, some had more difficulty concentrating on their individual development than others. Inger (52) has turned to Hindu teaching and spiritual books for help:

It’s helped me not to be as upset in different situations when things don’t work the way I want. Then I can just tell myself that, that my interpretation was just a thought. I create my own mind by believing in these thoughts that just spin around in my head, but I could also have other thoughts. I’m reflecting on myself in the past: she’s had thoughts in her upbringing and she’s had thoughts about society. For example, that you have to have a full-time job or you have to save money for your children, for the future. That’s a thought. It’s just an idea that could be replaced. (Inger, 52)

Many participants said they want to be a role model for others (although recognizing their own limitations in changing other people’s lifestyles). Their idea is to make inspiring social connections with others, which would create both local and more distant communities, and help to create an overall positive narrative of the lifestyles to which they aspire. They also have a list of influencers whom they consider important for their own path. For instance, Ines (32) is organizing courses during the ongoing process of building her ecological house, and finds a great deal of support for her values:

Every time someone new comes here it gives an incredible amount of energy. Especially in the moments when you just sit here and just kind of regret it because you encounter yet another problem. It helps to see the big picture again. It reaches somewhere, something will come of it and it’s great fun if we can just inspire one person to choose something other than the usual. (Ines, 32)

Values provide the downshifters with inspiration and motivation, and they are also influenced by (and themselves influence) their own and others’ eagerness to gain knowledge.

Knowledge

Our participants related gaining knowledge to processes of practical change, recognizing that there was always more to learn and that new knowledge informs new decisions in downshifting. Such knowledge-based decisions often went well with their generally high education levels, specific skills and creativity (which could also be interpreted as a bias, with our study including mainly higher-educated participants). As a forest owner, forest researcher and activist, Staffan (62) explained detailed forest management challenges. He and his partner live on a property with forest, and try to put knowledge into practice on a small scale:

This is where I have opportunities to act, as I own this forest. We’ve been working on several projects. We’ll try to get a permit to create a bird lake here, and to restore the wetlands. The physical work is what counts. You have to be able to see that you’ve done something. Otherwise, it’s just talk. If you’re doing a little teaching and research, hopefully you’ll spread some knowledge, but you never know if it’ll succeed at improving anything. (Staffan, 62)

Staffan possesses a great deal of scientific knowhow, which he continues to expand and use in practice. Other participants are autodidactic, in the sense that they have actively sought knowledge to enhance their sustainability decisions and support their life goals. However, scientific knowhow is not always essential; our participants demonstrate that they could often find knowledge based on their practical needs, in this way being highly resourceful. For example, David (30) moved to a village with his girlfriend and even has some other friends sharing their little farmhouse. He highly values the social connections in his own household as well as communication with neighbours in order to increase his knowledge about the place and the possibilities they have while living there. He said ‘We never have to worry that we cannot travel somewhere and there’s nobody to take care of our animals as there’s always one of us here or the neighbours can come and help’. They are active young people who would not have been able to live this lifestyle without the local social resources they have established.

Knowledge can also be part of enhancing creativity with practical information or offer more philosophical support in finding the inner strength and conviction to strive for sustainability. For instance, Anders (57) is interested in sociology and the humanities, having studied the history of ideas. His living room walls are full of books that he enjoys reading to gather new knowledge: ‘Now that I want to create my garden, I’ve studied permaculture and ecology. I’d like to read more about it. I’m really interested in that’. Gaining theoretical knowledge thus changes the way participants interpret various local resources and use them creatively. Their changing values can influence the kind of knowledge they are looking for, and vice versa (as their knowledge often influences their value changes).

Some participants who could be seen as less professional demonstrated alternative abilities to be resourceful and creative. Eva (56) and her husband own a small farmhouse where they keep animals, birds, bees, fruit and a vegetable garden. They sell garden products and organize workshops there. They said they easily maintain their garden without fossil fuels, only using them when they drive their products to market. This was inspired by a friend who had introduced Eva and her husband to debates on Peak Oil and to how using fossil fuels can lead to the end of mankind. They immersed themselves in this issue while still living in the city, and started to value life within the planetary limits and changed their lifestyle completely, illustrating an entrepreneurial mindset based on ongoing theoretical and practical knowledge-gathering:

He read all the research reports that existed. We chewed Peak Oil for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and began to think about what kind of consequence it has on our own lives. […] We started by installing stoves to be able to handle our own heating. We bought a small forest so we could have our own energy. We got a very energy-efficient car, which we didn’t use that often because we usually cycled. […] We organized an allotment garden for us in town and trained for cultivation and bee-farming there. […] We had many discussions and we concluded that it still doesn’t help. We had to move to the countryside, and it was really not because we wanted to move to the countryside but we realized that we have 50% food supply in Sweden, of which 100% is powered by oil. [Thus,] we have no food supply in Sweden at all. (Eva, 56)

A final subtheme indicates that participants sometimes simply follow their intuition towards simplicity because it feels right, drawing inspiration from their lived experiences and social practices. As such, Erik is inspired by what feels ‘right’:

I grew up around here and tried to escape from here a few times, but always ended up back here. But I’ve accepted it and now it’s so easy for me to do the things I want to do and enjoy doing. Because I have a setup here that’s needed. I like to build things from scratch with all kinds of different reusable material. And I have all the machines and material here and all the social contacts I need to be able to ask for help and extra skills from people who know me. (Erik, 35)

We were sitting on a kitchen sofa in a very artistically built tiny house on wheels, while he explained his urges to create and build houses and things as well as social community in his surroundings. Considering that his wife has a university degree in environmental science it was clear that, for him, following his passion for creating something was more important than reasoned explanations of sustainable living, which his lifestyle fully supported anyway.

Our participants explained their downshifting journey through their gained life experiences, re-evaluation of realization of values, and eagerness to learn. The reduced time working for a salary in recent years has given them more time to reflect and gain more knowledge in order to live more according to their values for a sustainable life. Still, independent of the time ‘after downshifting’ (see ), none of them could say that it is impossible to live more sustainably than they already do. Instead, they embrace the journey and are eager to push their own lifestyle further towards sustainable outcomes.

Spatial perspectives on downshifting

There is already a taste of some spatial aspects that are relevant to the downshifters in the previous section. This section analyses the spatial dimensions of downshifting and a more-than-relational view on space and sense of place, and relates the spatial experiences to the downshifters’ practices, experiences, values and knowledge (). This means examining the meanings the downshifters attach to the places where their social and physical realms of everyday life converge. We divide spatial perspectives into three subheadings: spatial adaptation and appropriation; local and global scales; and temporality of place.

Spatial adaptation and appropriation

One of the main overarching findings from the interviews is how our participants reappraise local conditions and find new opportunities and activities to integrate into their lifestyle. Downshifters re-evaluate the spatial settings they encounter, can learn and increase their knowledge about the local circumstances, and practically, based on their values and (globally) acquired knowledge, shape the local possibilities or adapt their own life in order to live more sustainably. In other words, they relate to the context and inertia in a place (Jones Citation2022) as well as find the possibilities to shape it through external influences. All our empirical examples above – Silvia’s farming, Carina turning her lawn into an allotment garden, Eva and her husband buying a small forest for energy supply combined with their allotment garden, Karin and Ulf’s engagement with the local coastal environment through their animals, and Staffan’s knowledge-based opportunities for deliberate forest management as a forest owner – illustrate deep and long-lasting interactions with their local physical surroundings. As such, the practices, values and knowledge of the interviewees are aspects of co-producing the places where they live; downshifting activities create a layer in time in these places.

Our findings illustrate the need for more attention to inertial constraints and possibilities at the local level when theorizing downshifters’ senses of place. Inertia, or stickiness, opens up for understanding places as not necessarily changing in a linear way forward, for instance when downshifters regard local history and reintroduce former land uses while also connecting to global relations, practices and discourses.

It is remarkable that this kind of adaptation and appropriation process takes place regardless of whether the individuals in question live in rural or urban areas, or in a farmhouse, villa or apartment. Looking for local opportunities in the form of allotment gardens, meaningful social connections or other things is a common thread. In the constant process of downshifting towards a simpler and sustainable life, downshifters value the contexts of a places and its history, social connotations and physical structure, and are eager to learn and experience this local everyday life. At the same time, they are also open to investing their time and physical work and to creating new social connections in order to make the place more sustainable for their individual lives and for society more generally. However, searching for a balance between local opportunities and individual values and life aspirations has also forced some downshifters to move to a different place as they were not able to adapt where they originally were. For example, Ella (36) and Carl (40) had moved to an old farmhouse in the countryside in their pursuit of a simpler life, but after a few years of too much physical work and having no local community they realized it did not suit them, and returned to a small town where their life with less wage work got onto the right track:

We were very lonely where we lived and noticed, I think above all, that we were lacking social connections and context. Everyone thought we were different and weird, but we decided that we don’t need to live like that and moved back here. These were difficult years. (Carl, 40)

The important point in their example is that even though they could not adapt in this setting, they did not stop pursuing their downshifting lifestyle but rather accepted the reality, and their dynamic solution was to find a more appropriate place for their chosen lifestyle.

Local and global scales of place attachment

With an appreciation for and eagerness to connect with local settings, the emotional attachment to the places was obvious among our downshifters. We connect this with humanistic understandings of place, combining the sense of position within society with the sense of spatial location when applying their moral and aesthetic values to their places of residence (Agnew, Livingstone, and Rogers Citation(1996) 2005, 445–447). Regarding highly environmental associations and deeply attaching one’s own lifestyle and everyday opportunities to local conditions involve an appraisal of classical theories of humanistic geography that should be pertinent in theorizations of downshifting and its spatiality (Tuan Citation1976; Rodaway Citation2004, 306). This entails deeper understandings of affective and moral issues, with our participants attaching meaning and significance to practices, experiences, values and knowledge as essential attributes of being-in-the-world. Tuan’s understanding of place as a centre of meaning and a focus of human emotional attachment (Entrikin Citation1976, 616) goes further than the idea of places as briefly being ‘meaningful’ (Cresswell Citation2010).

However, senses of place were also established in ways other than those suggested in humanistic geography, which has been criticized for its static view on places (Di Masso et al. Citation2019). We need to emphasize the time aspect and processes that change both places and downshifters, as well as the fact that places are not isolated entities but are rather globally connected. As opposed to the humanistic concept insideness, emphasizing long-term associations and close contacts at the local level (e.g. Relph Citation1976), our informants showed great flexibility in creating emotional place attachments on a short-term basis. Instead, they combined their knowledge and experiences of different places where they had lived in the past with their current, newly established sense of place. For instance, Erik’s considerate local connections and current living conditions also offered practical possibilities and comparisons based on experiences in different places of residence from his previous life, which were relevant when considering whether to stay put or move elsewhere. Most participants argued for a renewed importance of living one’s life locally to increase sustainability, but their values, practices, experiences and knowledge were simultaneously inspired by global trends, networks, environmental movements and flows of information regarding minimalism, tiny houses and similar ideas. As such, the downshifters studied here underlined contemporary issues of mobility and global connections that differ from the idea of ‘prolonged interactions’ with one place, as put forward in the 1970s (Entrikin Citation1976, 616). Instead, their sense of place was based on both local and place-based experiences, layered in their contexts across time, at the same time as they were influenced by their external connections to other places. Here, downshifting illustrates an example of a more-than-relational view on space, constructed by both fixities and flows, which affects their place attachment (Di Masso et al. Citation2019). Thus, we claim that the studied downshifters’ sense of place is mutually globally informed and locally adapted.

We therefore connect the downshifters’ vivid reappraisal of local settings as important meeting places for people, ideas and sustainable lifestyle projects with relational constructions of flows and relations that intersect with space (Massey Citation2005; Cresswell Citation2010). These fluidities of place, however, were added through vertical links and layers of social and political practices and memories to local places, as illustrated by David, Camilla, Mattias and others, whose locally based networks include relatives and childhood friends (living locally and elsewhere) offering important knowledge about local social practices. Childhood memories connected to imaginaries of other places like previous homes or holiday places rendered positive senses of place that were important for many of the studied downshifters’ current local place connections where they lived. In sum, downshifting is an illuminating example of how places, and the individuals residing there, are ‘bounded but relationally connected’ (Jones Citation2022, 2).

Temporality of place

Developing this idea further, the spatial experience is closely connected with temporal dimensions (Massey Citation2005) and the ‘temporal depth’ of places (Jones Citation2009). In our material, we saw that spending shorter periods of time in a certain place is not an obstacle to making meaningful local connections. For example, combining local and non-local knowledge, the downshifters studied here acknowledged that they may not live in their current place of residence for many years. For instance, Camilla was proud that she was ‘not originally from here’ and could imagine moving again when ‘life makes its corrections’. However, this did not prevent her from investing time and extensive resources in creating and maintaining connections to local social networks and natural surroundings. This had an impact on both her wellbeing and the lifestyle she aspired to, as well as her current place of residence. She could also relate to people living in more distant places, based on a strong motivation to create meaningful local and global connections. Such investments in local places irrespective of one’s expected duration of stay are often deeply rooted in downshifters’ social values.

The temporality of places is also reflected in the general fluctuation of the practices, knowledge and values of our participants, as we discussed earlier in this text. We know that the downshifting process has not been linear for our participants: working less has been replaced by working more in many cases, and has led to a new decision to work less; for some, downshifting was triggered by new parenthood or acute health issues. All these life events are also reflected in how the downshifters related to the places where they lived. They have had more or less time and emotion to invest in the local surroundings, and sometimes have not stayed put and have instead moved on to a more adaptable and relatable place, taking with them the experiences they gathered in their ‘previous’ place. This kind of openness to mobility and a short-term ability to create attachments is well developed in Di Masso et al.’s (Citation2019) fixities and flows conceptual framework, suggesting that individual relations to different places combine a psychologically feasible and relatable construction for a person who is concerned with sustainability values.

Conclusions

This paper has analysed pivotal themes in the lives of individuals who identify themselves as downshifters and voluntary simplicity seekers, and has studied the role of place and sense of place in relation to downshifting. The analysis offers a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of downshifting as a social process, in terms of both its practices and how it relates to space and place.

Starting with the spatial perspective, the paper is based on a novel spatial approach building on Jones’s (Citation2009; Citation2022, 2) ideas on how space should be seen as ‘bounded but relationally constructed’, whereby not only the relational aspects of space but also the context and inertia of a place should be approached. To this we add ideas from humanistic geography, which ascribes importance to attaching moral and emotional aspects to place, which affects the individual’s place attachment (Tuan Citation1976). Analysing the empirical material of downshifting individuals, we distinguish three analytical themes, based on which we analyse the spatial understanding of individuals: spatial adaptation and appropriation; local and global scales; and temporality of place. Notably, whereas these themes emerged from the spatial analysis of the downshifting process, they could also be attached to the placial analysis of individuals and communities in a broader context.

Moving on to the analysis of downshifting more specifically, we suggest that downshifting should be defined as a social process evolving over time and in relation to its conceptual cousin, voluntary simplicity. Accordingly, downshifting is a social process towards voluntary simplicity and thus emphasizes how lifestyles evolve over time in an individual’s life, with the process towards the end-goal potentially carrying meanings for the individual. In relation to the downshifting process, our study revealed three interlinked themes: (1) practices and experiences, (2) values and (3) knowledge. All these aspects of the participants’ lives carried significant importance in advancing towards sustainable lives. However, they ascribe different levels of importance to the various aspects of these themes, presenting a combination of varied individual approaches. All these themes were also in a process of evolution for each individual, mutually shaping one another and additionally taking in the local spatial impact. We conclude that downshifting is not a one-way street towards working less and valuing free time, as is suggested in the literature (Etzioni Citation1998; Alexander and Garrett Citation2017; Rebouças and Soares Citation2020). Rather, this study shows aspects of the complex downshifting process, with its individual twists and turns including success or misfortune in business or investments, health problems and progress in treatments, learning new knowledge and crafts. The downshifting process does not have to be perfect; there can also be periods of more work, higher income and higher consumption. The common denominator for the participants is their goal of living more sustainable and simpler lives for not only personal but also societal and global gains. Sustainability is not a measurable variable for these individuals, but rather a perception of the environmental value they are able to achieve by balancing their everyday life and practices. They accept that their ideal life remains beyond the horizon, while still having the motivation to continue their sustainability journey.

A challenge for future studies is to examine how downshifters and others sculpt the form of places through time, for instance via their practices, experiences, values and knowledge. It remains unanswered if participants of our study were exceptional because of their educational level, general experience of residential mobility and their current residence in Sweden. We encourage further research on the spatial and temporal dimensions that can support sustainable outcomes involving how a wide range of individuals and communities relate to place(s).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all participants for sharing their insights with us and to Maxim Vlasov and Iana Nesterova (both at Umeå University) for their valuable comments during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agnew, J. A., D. N. Livingstone, and A. Rogers, eds. (1996) 2005. Human Geography: An Essential Anthology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Alexander, S. 2011. “The Voluntary Simplicity Movement: Reimagining the Good Life Beyond Consumer Culture.” doi:10.2139/ssrn.1970056.

- Alexander, S., and J. Garrett. 2017. The Moral and Ethical Weight of Voluntary Simplicity. A Philosophical Review, 1–19. Simplicity Institute Report 17.

- Alexander, S., and S. Ussher. 2012. “The Voluntary Simplicity Movement: A Multi-National Survey Analysis in Theoretical Context.” Journal of Consumer Culture 12 (1): 66–86. doi:10.1177/1469540512444019.

- Allen, J. 2012. “A More Than Relational Geography?” Dialogues in Human Geography 2 (2): 190–193. doi:10.1177/2043820612449295.

- Barr, S., and A. Gilg. 2006. “Sustainable Lifestyles: Framing Environmental Action in and Around the Home.” Geoforum 37 (6): 906–920. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.05.002.

- Barr, S., G. Shaw, and T. Coles. 2011. “Sustainable Lifestyles: Sites, Practices, and Policy.” Environment and Planning A 43 (12): 3011–3029. doi:10.1068/a43529.

- Breakspear, C., and C. Hamilton. 2004. Getting a Life: Understanding the Downshifting Phenomena in Australia. Discussion Paper Number 62. The Australia Institute. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://apo.org.au/node/8344.

- Carson, R. 2013. “Silent Spring (1962).” In The Future of Nature, edited by L. Robin, S. Sörlin, and P. Warde, 195–204. Yale University Press. doi:10.12987/9780300188479-019.

- Clarkson, J. J., C. Janiszewski, and M. D. Cinelli. 2013. “The Desire for Consumption Knowledge.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (6): 1313–1329. doi:10.1086/668535.

- Crang, M., and I. Cook. 2007. Doing Ethnographies. London: Sage.

- Cresswell, T. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1068/d11407.

- Cresswell, T. 2014. Place: An Introduction. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. London: Sage Publications.

- Demetry, D., J. Thurk, and G. A. Fine. 2015. “Strategic Poverty: How Social and Cultural Capital Shapes Low-Income Life.” Journal of Consumer Culture 15 (1): 86–109. doi:10.1177/1469540513493205.

- Devine-Wright, P., and T. Quinn. 2020. “Dynamics of Place Attachment in a Climate Changed World.” In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, edited by L. Manzo and P. Devine-Wright, 226–242. New York: Routledge.

- Diener, A, and J Hagen. 2022. “Geographies of Place Attachment: A Place-Based Model of Materiality, Performance, and Narration.” Geographical Review 112 (1): 171–186.

- Di Masso, A., D. R. Williams, C. M. Raymond, M. Buchecker, B. Degenhardt, P. Devine-Wright, and T. Von Wirth. 2019. “Between Fixities and Flows: Navigating Place Attachments in an Increasingly Mobile World.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 61: 125–133. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.01.006.

- Echegaray, F., V. Brachya, P. J. Vergragt, and L. Zhang. 2021. Sustainable Lifestyles After Covid-19. New York: Routledge.

- Eimermann, M., C. Hedberg, and M. Nuga. 2020. “Is Downshifting Easier in the Countryside? Focus Group Visions on Individual Sustainability Transitions.” In Dipping in to the North, edited by L. Lundmark, D. B. Carson, and M. Eimermann, 195–216. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elgin, D. 1993. Voluntary Simplicity: Toward a Way of Life That is Outwardly Simple, Inwardly Rich. Second Rev. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Entrikin, J. N. 1976. “Contemporary Humanism in Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66 (4): 615–632. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1976.tb01113.x.

- Etzioni, A. 1998. “Voluntary Simplicity: Characterization, Select Psychological Implications, and Societal Consequences.” Journal of Economic Psychology 19: 619–643. doi:10.1016/S0167-4870(98)00021-X.

- Hamilton, C. 2003. Downshifting in Britain. A Sea-Change in the Pursuit of Happiness. The Australia Institute Discussion Paper Number 58.

- Hamilton, C., and E. Mail. 2003. “Downshifting in Australia.” The Australia Institute News, 34.

- Hobson, K. 2003. “Thinking Habits into Action: The Role of Knowledge and Process in Questioning Household Consumption Practices.” Local Environment 8 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1080/135498303200041359.

- Jones, M. 2009. “Phase Space: Geography, Relational Thinking, and Beyond.” Progress in Human Geography 33 (4): 487–506. doi:10.1177/0309132508101599.

- Jones, M. 2022. “For a ‘New New Regional Geography’: Plastic Regions and More-Than-Relational Regionality.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. doi:10.1080/04353684.2022.2028575.

- Juniu, S. 2000. “Downshifting: Regaining the Essence of Leisure.” Journal of Leisure Research 32 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1080/00222216.2000.11949888.

- Kala, L., L. Galčanová, and V. Pelikán. 2017. “Narratives and Practices of Voluntary Simplicity in the Czech Post-Socialist Context.” Sociologický Časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 833–855. doi:10.13060/00380288.2017.53.6.377.

- Kennedy, E. H., H. Krahn, and N. T. Krogman. 2013. “Downshifting: An Exploration of Motivations, Quality of Life, and Environmental Practices.” Sociological Forum 28 (4): 764–783. doi:10.1111/socf.12057.

- Kosinski, M., S. C. Matz, S. D. Gosling, V. Popov, and D. Stillwell. 2015. “Facebook as a Research Tool for the Social Sciences: Opportunities, Challenges, Ethical Considerations, and Practical Guidelines.” American Psychologist 70 (6): 543. doi:10.1037/a0039210.

- Lindsay, J., R. Lane, and K. Humphery. 2020. “Everyday Life After Downshifting: Consumption, Thrift, and Inequality.” Geographical Research 58 (3): 275–288. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12396.

- Longo, C., A. Shankar, and P. Nuttall. 2019. “‘It’s Not Easy Living a Sustainable Lifestyle’: How Greater Knowledge Leads to Dilemmas, Tensions and Paralysis.” Journal of Business Ethics 154 (3): 759–779. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3422-1.

- Massey, D. 1995. “Places and Their Pasts.” History Workshop Journal 39: 182–192. doi:10.1093/hwj/39.1.182.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Meadows, D. H., D. L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. W. Behrens. 1972. The Limits to Growth, A Report of THE CLUB OF ROME’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. Universe. https://www.clubofrome.org/publication/the-limits-to-growth/.

- Nässén, J., and J. Larsson. 2015. “Would Shorter Working Time Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions? An Analysis of Time Use and Consumption in Swedish Households.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (4): 726–745. doi:10.1068/c12239.

- Nicolosi, E., and G. Feola. 2016. “Transition in Place: Dynamics, Possibilities, and Constraints.” Geoforum 76: 153–163. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.09.017.

- Osikominu, J., and N. Bocken. 2020. “A Voluntary Simplicity Lifestyle: Values, Adoption, Practices and Effects.” Sustainability 12 (5): 1903. doi:10.3390/su12051903.

- Parker, C., S. Scott, and A. Geddes. 2019. Snowball Sampling. Sage Research Methods Foundations. doi:10.4135/9781526421036831710.

- Paulsen, R. 2017. Arbetssamhället. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Atlas.

- Persson, O., J. Larsson, and J. Nässén. 2022. “Working Less by Choice: What Are the Benefits and Hardships?” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 18 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.2023292.

- Pierce, J., D. G. Martin, and J. T. Murphy. 2011. “Relational Place-Making: The Networked Politics of Place.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00411.x.

- Popcorn, F. 1991. The Popcorn Report. London: Thorsons.

- Rebouças, R., and A. M. Soares. 2020. “Voluntary Simplicity: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: 303–319. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12621.

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. Vol. 67. London: Pion.

- Rich, S. A., S. Hanna, and B. J. Wright. 2017. “Simply Satisfied: The Role of Psychological Need Satisfaction in the Life Satisfaction of Voluntary Simplifiers.” Journal of Happiness Studies 18 (1): 89–105. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9718-0.

- Rich, S. A., S. Hanna, B. J. Wright, and P. C. Bennett. 2017. “Fact or Fable: Increased Wellbeing in Voluntary Simplicity.” International Journal of Wellbeing 7 (2). doi:10.5502/ijw.v7i2.589.

- Rodaway, P. 2004. “Yi-Fu Tuan.” In Key Thinkers on Space and Place, edited by P. Hubbard and R. Kitchin, 306–310. London: Sage Publications.

- Sandow, E., and E. Lundholm. 2020. “Which Families Move Out from Metropolitan Areas? Counterurban Migration and Professions in Sweden.” European Urban and Regional Studies 27 (3): 276–289. doi:10.1177/0969776419893017.

- Schor, J. B. 1998. The Overspent American. New York: HarperCollins.

- Schor, J. B. 2005. “Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9: 37–50. doi:10.1162/1088198054084581.

- Seamon, D. 1996. “A Singular Impact: Edward Relph’s Place and Placelessness.” Environmental and Architectural Phenomenology Newsletter 7 (3): 5–8.

- Tan, P. 2000. “Leaving the Rat Race to Get a Life: A Study of Midlife Career Downshifting.” Doctoral diss., Swinburne University of Technology.

- Tuan, Y. F. 1974. Topophilia. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Tuan, Y. F. 1976. “Humanistic Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1976.tb01089.x.