ABSTRACT

The succession of rebordering shocks that occurred in recent years raises questions about the implications of these (geo)political events for cross-border cooperation. Based on the premise that special attention should be paid to the evolution of ideas pertaining to borders as a forerunner of significant policy changes, this paper seeks to show the extent to which the reintroduction of temporary border controls between Sweden and Denmark since 2015 has changed the meaning cross-border cooperation stakeholders give to the national border crossing the Öresund region. In order to identify ideational shifts in the mindset of cross-border cooperation actors, the multiplicity of meanings concerning borders is captured according to a relational perspective using semantic network analysis. In doing so, an innovative method is proposed. The comparative analysis of actors' collective mental representations of the border in 2014 and 2021 allows us to show the impact of rebordering shocks. If the connecting role of the border is now considered marginal, the opportunities it is likely to represent for the Öresund region's economic growth are still relevant. Moreover, the recognition of a common regional identity also appears to have been strengthened. In the meantime, the idea that the border could be a source of conflict has gained momentum. The increasing recognition of the ambivalence of the border reminds us that a crisis is often a source of new challenges, but also of opportunities.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, a succession of (geo)political events of varying nature and scale have led to the closure and militarization of many borderlands, the reintroduction of controls along supposedly open borders – such as within the Schengen Area –, and more broadly, a strengthening of nationalist-territorial ideas and a hardening of border regimes in various regions around the globe (Jones Citation2012; Murphy Citation2022; Vallet Citation2016). In Europe, Brexit, the so-called ‘European refugee crisis’ and the COVID-19 pandemic constitute the most notable events that have triggered border closures and the reintroduction of border checks. The revival of national borders and their selective permeability have led the scientific community to wonder about the future of the Schengen border regime and more generally, the process of European integration caught between the contradictory logics of economic opening and security-led closure (Casella Colombeau Citation2020; De Somer Citation2020; Gülzau Citation2023; Medeiros et al. Citation2021; Stoffelen Citation2022). The consequences of border closures – in particular in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic – for borderlands, the practices of their inhabitants and border workers, have also attracted sustained attention (Peyrony, Rubio, and Viaggi Citation2021; Lara-Valencia and Laine Citation2022; Andersen and Prokkola Citation2021). However, only a few studies have looked at the impact of rebordering on cross-border cooperation (CBC), which represents one of the pillars of European integration (Svensson Citation2022). To better understand the transformations that may affect cross-border regionalization within the European Union (EU), this paper argues that special attention should be paid to the evolution of ideas and discourses pertaining to borders and mobilized by the actors involved in CBC. Theoretically, such a constructivist perspective draws on the literature concerning discursive institutionalism, as this contends that ideas play a central role in institutional and policy change (Blyth Citation2002). In the context of EU cross-border regionalism, Molema (Citation2021) has shown that the emergence of new economic ideas in the 1970s actually preceded and stimulated subsequent CBC change. With regard to the current situation along EU’s internal borders, the reintroduction of border controls clearly contradicts the principle of free movement of EU nationals that has been a key aspect to promote CBC (Scott Citation2012). Any substantial ideational shift in the mindset of CBC stakeholders concerning the meaning of borders could therefore represent a forerunner of significant future changes involving cross-border regionalization.

In order to explore this line of thought further, the current paper seeks to show the extent to which the rebordering dynamic observed in the Öresund region since 2015 has changed the meaning of the national border between Denmark and Sweden for the CBC stakeholders involved in this emblematic case of cross-border region-building. More specifically, the aim is to see how the temporary, yet repeated, reintroduction of border controls has altered the way actors collectively view the border, as well as what meaning they give to it. To achieve the aim and provide relevant empirical insights, the proposed research tackles a certain number of challenges. In doing so, this paper also proposes a methodological approach well suited to grasp CBC actors’ collective mental representations of the border and to identify changes in their statements. The first challenge concerns the conceptualization of the meaning of borders, and in particular the fact that borders mean different things to different people (Balibar Citation2002). In substance, what is needed is an operational definition of the multiple nature of borders, able to represent complex empirical realities. The second challenge relates to the case studied. In order to identify the impact of the reintroduction of border controls on the mindset of CBC actors, the case under scrutiny should have undergone a significant rebordering dynamic. The third challenge concerns the data to be used. In the absence of relevant corpora of text documents that could reveal how the recent border closures have affected the way CBC stakeholders understand the border, there is a need to collect such information in an ad hoc manner.Footnote1

These different challenges have been addressed in the following ways. First, by conceptualizing the multiplicity of borders as a set of concepts that are related to each other according to actors’ statements, we propose to identify the ideas associated with the border and study their relationships through semantic network analysis. This approach is understood as a framework of representation and a body of methods to analyse the associations of words and concepts according to a relational perspective (Danowski Citation1993; Yang and González-Bailón Citation2017). Second, we selected the case of the Öresund region for the empirical analysis. In addition to its iconic status as a model of cross-border integration in Europe (Löfgren Citation2008; OECD Citation2013), this region is also particularly relevant due to the successive ‘rebordering shocks’ (understood here as the reintroduction of border controls) that have taken place between 2015 (and the ‘European refugee crisis’) and 2021 as part of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than isolating the effect of a particular rebordering shock on CBC, the current paper is concerned with the transformations induced by a general trend (i.e. a rebordering dynamic). Such a perspective is aligned with the view that processes of institutional and policy change are only rarely sudden and massive. Instead, they usually evolve over time, incrementally and subtly (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010). Third, the data concerning the ideas and concepts associated with the border was collected via semi-structured interviews among CBC stakeholders. Two rounds of interviews targeting the same actors were conducted, one in 2014 and the other in 2021. Each time, key representatives of the organizations involved in the Öresund regional cooperation were asked about what the border meant to them. The individual mental representations were then put together and analysed as a collective discourse reflecting the multiplicity of the border’s meanings for the group of actors targeted at the two reference dates.

The comparative analysis of actors’ border discourses before and after the reintroduction of border controls allows us to see how the rebordering dynamic at work has changed the meaning of the border for the CBC stakeholders in the Öresund region. To achieve this objective, a three-step approach is followed. First, we carry out an inductive content analysis of the keywords provided by the actors interviewed to describe what the border means to them, in order to identify the changes in conceptualizations (i.e. frames) induced by the rebordering experienced. Based on the analysis of keyword occurrences, the aim is to determine which framing categories had appeared or had been reinforced, and which ones had disappeared or diminished. In order to deepen our understanding of the conceptual shifts in CBC actors’ discourse, we then proceed to an analysis of the relationships among concepts that reflect different facets of the border according to actors’ assessment. The multiple aspects of the border and changes therein are grasped through a comparison of graphs depicting the border’s semantic networks in 2014 and 2021. Lastly, the characterization of the roles played by the concepts in the semantic networks based on centrality measurements allows us to better understand the changes at work in the understanding that CBC actors have of the border and its multifaceted meaning.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we review the literature on the implications of rebordering on CBC in Europe and highlight the research gap that motivated this study. In the third section, we first introduce our conceptualization of the border’s multiplicity and then present semantic network analysis as the approach mobilized for our research. The fourth section is dedicated to the presentation of the Öresund region and the rebordering dynamics that has occurred since 2015. In the subsequent section, we start by describing how the data were collected and then we present the methodologies used to perform the empirical analyses. The sixth section presents the results and the final section concludes.

The impact of rebordering on cross-border cooperation: a largely overlooked topic

Until recently, the conditions and implications of rebordering dynamics for local and regional CBC initiatives have mainly been addressed in the context of external EU borders to the east (Koch Citation2018) or in the Mediterranean area (Celata, Coletti, and Stocchiero Citation2017). The focus of scholars studying European CBC has been on debordering, European integration and the EU cohesion policies and their cross-border manifestations at the local and regional scales (see notably De Sousa Citation2013; Kaucic and Sohn Citation2022; Noferini et al. Citation2020; Perkmann Citation2007; Scott Citation2012). Following the temporary closure of some intra-Schengen borders during the peak of the ‘European refugee crisis’ in 2015–2016, the impact of this specific rebordering shock on the activities and attitudes of CBC actors along well-integrated European borderlands started to spark interest. Facing national decisions to reintroduce controls along open borders, Euroregions and their stakeholders were confronted with divergent imperatives (in particular the free movement of workers versus the need to ensure security and public order) and have appeared to be either helpless or relatively passive (Evrard, Nienaber, and Sommaribas Citation2020; Klatt Citation2020; Svensson Citation2022). The attention paid to sudden changes in cross-border mobility has also triggered new insights into the resilience of border regions and the development of adaptive and coping strategies (Prokkola Citation2019; Andersen and Prokkola Citation2021).

The reintroduction of active border policing, systematic checks and even the closure of border crossing points as part of the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic has given a new impetus to studies scrutinizing the effects of what has been termed ‘covidfencing’ (Medeiros et al. Citation2021). The social, economic and political consequences of border closures for European border regions – and in particular the disruption of people’s daily life, and the fragility of livelihoods and businesses that depend on cross-border interactions – have been the subject of a growing number of works (Lara-Valencia and Laine Citation2022; Montaldo Citation2020; Opiłowska Citation2021; Peyrony, Rubio, and Viaggi Citation2021; Radil, Castan Pinos, and Ptak Citation2021; Wallin Aagesen, Järv, and Gerber Citation2022). The impact of these border closures on CBC activities has particularly been investigated by studies focusing on the practical and immediate consequences, and aiming to provide detailed and factual accounts of what has happened (Weber Citation2022; Böhm Citation2021a). At the same time, some analyses have looked at the longer-term consequences of the COVID-19-related border closures on CBC. In their study of the impact of COVID-19 on the structure and agency of two twin towns in Central Europe, Kajta and Opiłowska (Citation2022) highlight the weakness of CBC initiatives and institutions confronted with the closure of borders decided by their national government, most of the time without prior consultation. The authors also note that the crisis has led some local CBC initiatives to strengthen their common structure and deepen its institutionalization. This seems particularly to be the case where high levels of cross-border commuting were involved (Böhm Citation2021b). Yet beyond these immediate reactions, little is known about the way in which the rebordering dynamic at play actually changes the very meaning of borders for CBC stakeholders. In the next section, we discuss how a border’s meaning can be grasped according to a semantic network perspective.

A semantic network perspective on the meaning of borders

Conceptualizing a border’s multiplicity

Over the past three decades, the ways in which borders are conceived have undergone significant changes. Border scholars have notably moved away from a perspective in which borders appear as the physical outcomes of political and social processes, towards dynamic and non-finalizable processes (Kolossov and Scott Citation2013). Evolving from divisive territorial lines and political institutions, into socio-cultural practices and discourses symbolizing spatial differentiation, the concept of bordering has gradually established itself as a new paradigm (Newman Citation2006; Paasi Citation1998; Van Houtum and Van Naerssen Citation2002; Van Melik Citation2021). As part of this processual ‘turn’ in border studies, borders are conceived as social, cultural and political constructions constantly being made. As borders appear more dispersed, fluid and multifaceted, the multiplicity of actors, practices and situations must be taken into account (Andersen, Klatt, and Sandberg Citation2012). For Andersen and Sandberg (Citation2012), the multiplicity of borders emanates from the different practices through which borders are ‘performed’ and promulgated, and requires thinking in terms of heteronomy and diversity. Heteronomy refers to the fact that a border does not exist as such, but is created through the meanings that the actors attach to it. Diversity points to the various actors that contribute to the creation and transformation of borders and implies taking into consideration the diversity of experiences, perceptions and representations.

Different conceptualizations have been proposed to come to grips with the various agencies and meanings at work in border-making, such as ‘borderwork’ (Hooper Citation2004; Rumford Citation2008) or ‘borderscapes’ (Brambilla Citation2015; Rajaram and Grundy-Warr Citation2007). The plurality of meanings and their potentially contradictory nature is notably acknowledged by Rajaram and Grundy-Warr (Citation2007), who define a borderscape as a zone of contingent and competing meanings. The practical application of these vague yet relevant conceptualizations nevertheless remains challenging (Krichker Citation2021). With a view to proposing a conceptualization of a border’s multiple aspects that allows the concept to be grasped empirically, the reference to a relational perspective to multiplicity as emphasized by Husserl in his philosophical reflections offers interesting insights (Ierna Citation2012). According to this perspective, multiplicity is defined by the relations between the properties of the border, rather than the mere presence or juxtaposition of meanings (Sohn Citation2016). More specifically, we contend that what matters are the ways in which different ideas are articulated to each other, the ways certain meanings are associated with others whereas some are opposed, and the ways some concepts play a prominent role whereas others appear marginal. Heterogeneous and even contradictory meanings are part of what borders signify, since they are fundamentally equivocal and ambivalent (Agnew Citation2008; Anderson and O’Dowd Citation1999; Van Houtum Citation2011). In order to translate this conceptualization of multiplicity into an approach capable of representing and analysing empirical data about borders, the use of semantic network analysis appears appropriate.

Semantic network analysis as a method to analyse text-related data

Semantic network analysis broadly encompasses the study of the relationships among words or concepts, and describes the underlying meaning in text-based networks (Danowski Citation1993). It is sometimes described as being at the intersection between content analysis and network analysis (Segev Citation2021). Similar to content analysis, semantic network analysis focuses on the words, topics and concepts present in texts. The main differences relate to the privileged relational approach to studying the meaning of words and to the use of the methodological corpus of network analysis to reveal, represent and model these relations and the structures they draw. Since the early 1990s, the network analysis of text-related data has become a widely-used approach and methodology in a broad range of disciplines and academic fields (for an overview of different research, see Segev Citation2021). Yet the cross-disciplinary nature of semantic network analysis comes with a variety of theories, methods and approaches, and hence a certain lack of coherence. By following Yang and González-Bailón (Citation2017), we can nevertheless identify some of the essential aspects that allow us to better understand the analysis of semantic networks and to subsequently develop our own approach.

The first aspect allowing us to distinguish different approaches refers to the nature of the network considered. There are mainly two possibilities (Yang and González-Bailón Citation2017): either the network corresponds to a set of relations between ‘semantic units’ (for example, the co-occurrence of words in a public discourse), or a set of relations between actors and concepts (for example, policymakers and their statements). In the former case, we are dealing either with a unimodal network (concept-to-concept) representing the existence or the number of times that two concepts co-occur (such as within the same sentence), or with a bimodal network (word-to-concept) reflecting the association between the two categories of semantic units. In the latter case, this involves a bimodal network (actor-to-concept), for which the matrix will reflect the reference of an actor to concepts.

The second aspect concerns the level of data collection and analysis. According to Yang and González-Bailón (Citation2017), three levels can be distinguished. At the individual level, the analysis focuses on the discourse of an actor, to undertake what is generally termed cognitive mapping (i.e. the mental representations or models of an individual). At the interpersonal level, the analysis focuses on a group of actors (such as a policy community or an advocacy coalition) in order to determine the relations of congruence or conflict between concepts or between actors. This interpersonal level is the preferred object of discourse network analysis (Leifeld Citation2017). Lastly, the collective level corresponds to the aggregation of semantic data produced by a collective of individuals, typically in order to carry out what is called framing analysis (the identification of patterns between concepts). The distinction between the interpersonal level and the collective level lies in the fact that at the collective level, the information on who issued what expressions is not explicitly considered in the analysis, whereas it is retained as a key aspect for the interpersonal level (Yang and González-Bailón Citation2017).

The third aspect that allows us to distinguish different approaches relates to the definition of the semantic units considered, as well as the relationships between them. The definition of semantic units can follow an inductive or a deductive approach (Carley and Palmquist Citation1992). In an inductive approach, the semantic units are identified based on the interpretation of the data collected. Such an approach appears particularly well-suited to identifying unexpected emergent meanings. The deductive approach involves identification of the semantic units in texts according to preconceived categories. Such categories are usually derived from theory in order to test hypotheses. For both approaches, one can distinguish between higher-order semantic units (abstract concepts) and lower-order semantic units (words). Lastly, the relationships among semantic units can either rely on the co-occurrence of concepts within a group of words or on the free association between words and concepts based on the interviewees’ interpretation.

The case of the Öresund region

A model of cross-border cooperation

The Öresund region is a cross-border area straddling the strait that separates Denmark from Sweden.Footnote2 Made up of the Capital and Zealand regions in Denmark and the Skåne and Halland regions in Sweden, the Öresund region has nearly 4.4 million inhabitants. The emergence of this cross-border region is closely linked to the construction of a bridge between Copenhagen and Malmö at the end of the 1990s. In fact it is thanks to this transport infrastructure linking the two sides of the border that a cross-border regional integration dynamic has been generated (Matthiessen 2005; Schmidt Citation2005. For a recent assessment, see Persson and Persson Citation2021). In order to anticipate the effects induced by the construction of the Öresund bridge, the municipalities and regions located on the Danish and Swedish sides of the strait decided to create a political platform termed Öresundskomiteen (Öresund Committee) in 1993. Composed of members representing local and regional authorities (their number has varied over time, from 20 to 36), its role consisted in boosting CBC through a series of projects such as the Øresund regional development strategy (Ørus) focusing on innovation and entrepreneurship or Orestat providing cross-border regional statistics (Persson and Persson Citation2021). This work was complemented by a number of specific bi-national initiatives and specialized organizations such as Øresunddirekt (a common information centre about working, living and studying in the Öresund region), or Medicon Valley Alliance (a Danish-Swedish life science cluster). The objective was to strengthen the dynamics of cross-border integration at the economic, cultural and scientific levels, and to enhance the region’s visibility and attractiveness nationally and internationally. It is in this context that an ambitious strategy of place-branding was launched, centred on the human capital of the region and mobilizing the figure of the physical bridge as a symbol of an open and creative region (Hospers Citation2006). This highly symbolic initiative, aimed at giving a new meaning to the border, made a strong impression in the region and contributed to setting up the Öresund region as an exemplary CBC in Europe (Löfgren Citation2008). At the same time, the early 2000s were marked by a sharp increase in the number of cross-border commuters, the integration of labour markets and to a lesser extent of residential markets, as well as an intensification of business networks and cultural interactions. In 2008, when the financial crisis hit the Danish economy, more than 25,000 commuters were crossing the border daily. The period that followed was marked by a slowdown in the dynamics of functional integration and led regional players to question the raison d'être of their cooperation.

Lacking political support, especially on the Danish side where local politicians no longer saw the added value of CBC very clearly, the Öresund Committee gradually lost its capacity for action in the early 2010s (Persson and Persson Citation2021). Anxious to give Copenhagen an attractive image in a context of heightened economic competition between large cities in northern Europe to attract investment and skilled jobs, the Danish local elites undertook to restructure the CBC around a renewed place-branding strategy. This centred on the image of ‘Greater Copenhagen’ and with a focus on economic growth. Whilst the cross-border dimension of the new initiative was seen as a means of acquiring a competitive critical mass on the Danish side, the expectations in terms of CBC were different on the Swedish side and related to the removal of barriers linked to the border and the implementation of a single labour market. After some hesitation on the part of the Swedish stakeholders in the face of the affirmation of Copenhagen's leadership, a new cross-border governance structure, officially called the Greater Copenhagen and Skåne Committee, was created in 2016. Its ability to instil a new dynamic of growth and integration within the cross-border region has nevertheless been challenged from the outset by the revival of the national border.

The rebordering dynamics

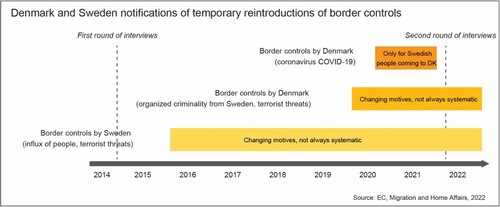

The rebordering dynamic that has impacted the Öresund region revolves around three successive waves of border controls that unfolded between 2015 and 2021 (). The first shock started in autumn 2015 with the reintroduction of border controls by the Swedish police in the context of what has been called the ‘European refugee crisis’. Supposedly to facilitate checks, a metal fence was installed on a platform at Hyllie station (), the first stop on the Swedish side when crossing the border using the Öresund bridge. From January 2016, transborder transporters like the Danish State Railways DSB asked security companies to inspect all travellers IDs at Copenhagen airport train station in order to comply with the Swedish government request not to transport any humans without valid identification into Sweden (Wissing Madsen Citation2017). In 2017, systematic checks ceased and were replaced by random checks. Sweden has nevertheless prolonged until today the possibility to perform temporary border controls within the framework of the Schengen Border Code by regularly requesting extensions and referring to special emergency situations. These have evolved from an ‘Unprecedented influx of persons’, to a ‘Continuous large influx of persons seeking international protection’ and later to a ‘Serious threat to public policy and internal security’ (European Commission Citation2022). As acknowledged by a CBC stakeholder from the City of Malmö:

When the Swedish government introduced the border controls on the refugees coming from Denmark to Sweden in 2015, this was a shock. It was social-democrat government that took that decision and in the Swedish context, this was something big.Footnote3

The second rebordering shock came in November 2019, with the reintroduction of border controls by Danish national authorities following shootings and a bomb attack in Copenhagen blamed on criminal gangs from Sweden. Introduced initially for a period of six months, these border controls have subsequently been the subject of regular requests for extensions by Denmark (European Commission Citation2022). In this case, as in the previous one, the practice is aligned with the strategy followed by many other EU member states that prolong internal border controls in the Schengen Area beyond their maximal duration ‘by shifting from one legal basis to another’ (De Somer Citation2020, 180).

Lastly, the third rebordering shock occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, several waves of border controls have been introduced, mainly by the Danish government. These checks only targeted people coming from Sweden and wishing to travel to Denmark, and entry was limited only to travellers with a reason deemed valid (such as those living or working in Denmark). As, at the same time, Danes could freely travel to Sweden for shopping or to stay in their summer house, this asymmetrical control of border crossings generated a great deal of frustration and resentment among the Swedish population, who felt they were being treated like second-class residents.Footnote4 In December 2020, Sweden also closed its border with Denmark for a short period in an attempt to counter the arrival of a new variant of the COVID-19 virus.

While each of these three rebordering shocks presents specific characteristics and dynamics, the partial overlap of the resulting border control measures suggests the existence of an overall dynamic and a substantial change in the behaviours and perceptions of the Öresund region’s inhabitants. The cumulative effect of the various temporary border closures has in fact contributed to reinforcing ‘us’ versus ‘them’ sentiments between people on both sides of the Öresund.Footnote5 As noted by a stakeholder interviewed:

You have to remember that we had already implemented the Passport Union in 1953. We had the free movement of people long before the EU. So it was very tough for Nordic people to realize that we were frontrunners of cross-border cooperation and now we are closing our borders. It was almost a shock that this is happening in the Nordics. The most important aspect is the loss of trust in the idea of living in an integrated cross-border region.Footnote6

The way Sweden and Denmark have dealt with the refugees and the policies they have implemented have contributed to split the two countries. Sweden is somewhat following Denmark now. We are doing what Denmark did ten years ago. Migration policies are polarizing the relationships between the two countries.Footnote7

Data collection and methods

Stakeholder interviews

The data used for this research was collected during two rounds of interviews. The first round was carried out in April–May 2014 as part of a project that focused, among other things, on the changing significance of European borders.Footnote8 Seven years later, the opportunity to conduct a new series of interviews arose, making it possible to carry out a comparative analysis.Footnote9

The selection of interviewees was based on a two-step procedure. First, an initial group of actors was identified using a positional approach: the analysis of documents produced by the Öresund Committee (annual reports, briefs and press releases) made it possible to retrieve the key organizations as well as the people who represent them. Second, a group of complementary actors was obtained using a snowball sampling approach: at the end of each interview, the interviewee was asked to name a few important stakeholders in their eyes. The actors who were nominated at least three times by the first set of interviewees constituted the second group of interviews. In all, the CBC actors thus identified belonged to the public sector (i.e. institutional actors), the private sector (i.e. economic actors) and the civil society sector (i.e. non-profit organisations). The list of actors interviewed in 2014 was re-used for the 2021 interviews. While the organizations targeted remained the same to a large extent (although sometimes with name changes), the people representing them have practically all changed due to a high turnover in elective or managerial positions. In order to favour the comparability of the data, new organizations created after 2014 or organizations that had not been included during the first round of interviews were not considered.

During the interviews, the collection of data reflecting actors’ meaning concerning the Danish-Swedish border followed a three-step procedure. First, actors were asked to state their understanding of the national border at the time, using keywords or short descriptions. These keywords could relate to ideas, images, facts or experiences that they associate with the border. The objective was to leave as much freedom as possible for people to express their opinion. The only constraints were in the short format of the desired descriptions and their number being limited to six. Second, interviewees were asked to rate the importance of their keywords on a three-point scale. The underlying assumption was that the different aspects of the border described by a respondent would not necessarily have the same salience. Lastly, actors were asked to associate their keywords to a set of generic concepts suggested by the interviewer. Each keyword could be related to up to four concepts. By asking the actors to interpret the significance of their keywords themselves using pre-conceived categories, the idea was to rely on their understanding of what the border means in order to link lower-order semantic units (the keywords) to higher-order units (abstract concepts). It was also a way to build a consistent dataset about actors’ border discourse and cope with the variations characterizing the spontaneous answers of the interviewees and the diversity of the discursive registers mobilized (sometimes familiar, sometimes at a technical or expert level). This interview protocol first introduced in 2014 was scrupulously reproduced during the interviews carried out in 2021. As a complement, open-ended questions were asked in order to provide additional insights into the unfolding of the rebordering dynamic and its impact on CBC.

The definition of the concepts used as pre-conceived categories to interpret the meaning of actors’ keywords plays a key role, insofar as it partly influences the analysis of their mental representations and therefore the results of the research. The criteria determining the choices are as follows: (i) The selected set of concepts needs to cover the different general meanings of the border using broad analytical categories (i.e. higher-order semantic units); (ii) the meanings attached to an open border and those that stem from a closed border should be considered in a balanced way; (iii) the ambivalent dimension of borders (both enabling and constraining) should also be taken into consideration; (iv) the number of concepts must remain limited in order not to overburden the survey protocol. Based on a literature review dealing with the changing meaning of borders from a CBC perspective, eight concepts were retained (indicated in italics below). The first four concepts are derived from the paper by Herzog and Sohn (Citation2014), who consider the ambivalent meanings of debordering and rebordering dynamics for local CBC stakeholders. According to these authors, when a border is open, it can either be seen as a connection (or an interface) between two entities or as a threat (in the sense that the open border generates territorial anxieties). In the same vein, when a border is controlled or closed, it can either be seen as a protection or as an obstacle (the two opposing meanings of a barrier). In order to complete this list of broad descriptors, four supplementary concepts were added based on a review of seminal papers (notably Newman Citation2006; O’Dowd Citation2002; Van Houtum and Van Naerssen Citation2002): borders as opportunities, markers of identity, symbolic places and sources of conflict. Beyond the selection of the concepts mobilized, which cannot avoid having a certain arbitrary dimension, what ultimately matters is the fact that the same list of concepts was used during the two interview campaigns.

presents the basic statistics relating to the two sets of data collected during the interviews. Between 2014 and 2021, it should be noted that there are ultimately few variations in the indicators used. Although the number of respondents was slightly lower in 2021, the overlap rate with 2014 is 90 per cent. In other words, in a large majority of cases, the interviews focused on the same organizations involved in CBC. Given the specificities of the latter in Europe, institutional actors constitute the majority group. These were generally civil servants, managers, advisors or planners, working in local and regional public administrations and involved in CBC. These actors represented 70 and 76 per cent of respondents in 2014 and 2021, respectively. The rest of the respondents comprised economic actors (e.g. cross-border infrastructure managers, representatives of chambers of commerce and industry and of industrial alliances) as well as civil society actors (e.g. representatives of professional associations, non-profits foundations involved in cross-border issues). The average number of keywords mentioned and the average number of concepts attributed to each keyword are relatively stable between the two dates.

Table 1. Parameters of data collected during interviews in 2014 and 2021.

Measurements and analytic methods

The analysis of ideational changes in the way actors frame the border is based on two complementary methods. The first is an inductive content analysis. The objective is the identification of themes that emerged, or were reinforced, as part of the mental representations of the stakeholders following the rebordering dynamic (or alternatively the disappearance or diminution of themes that were present before border controls were reintroduced). It is therefore a question of examining the data collected during the interviews – in particular the keywords expressed by the actors to describe the meaning of the border – and of carrying out coding in order to identify a limited number of content-related categories (Krippendorff Citation1980). Such categories emerge from raw data through repeated examination and comparison, and this approach is especially useful when there is not enough former knowledge about the phenomenon being studied (Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008). The keywords collected in 2014 and 2021 were coded into 13 categories. The comparison of the weighted occurrenceFootnote10 of keywords per category before and after the rebordering dynamic makes it possible to classify the categories according to five trajectories: appearance (a new category in 2021), increase (a category more important in 2021 than in 2014), stability (more or less the same importance), diminution (a category less important in 2021 than in 2014) and disappearance (a category no longer significant in 2021).

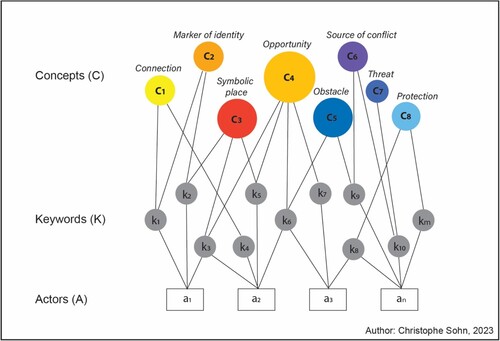

The second method is semantic network analysis as previously introduced. The data collected can be organized according to a three-mode network composed of actors (A), keywords (K) and concepts (C). The set A = {a1, … ,an} corresponds to the CBC actors interviewed. The set K = {k1, … ,km} corresponds to the descriptions provided by the actors concerning their understanding of the border. Lastly, the set C = {c1, … ,c8} corresponds to the eight predefined concepts with which the actors were asked to associate their keywords. is a schematic representation of the socio-semantic network in the form of a restricted tripartite graph, where the actors interviewed are linked to the keywords they expressed and the keywords are linked to the preconceived concepts according to the free associations defined by the actors. By definition, the restricted tripartite network prohibits direct links within each entity A, K and C.

The study of the significance of the border is based on the bi-modal KC network made up of keywords and concepts, and derived from the previously mentioned tri-modal network.Footnote11 The KC network depicts the aggregation of the mental representations of the actors interviewed, and it corresponds to the collective level mentioned before. The comparison between the two KC networks of 2014 and 2021 is facilitated due to their structural properties, which are similar ().

Table 2. Structural properties of the KC networks.

To extract the underlying meaning embedded in the the KC networks – or in other words, the overall meaning of the border for the Öresund CBC stakeholders in 2014 and 2021 – we apply social network analysis approaches and measurements.Footnote12 The main method we use aims to detect the role played by the concepts in the semantic networks. Based on earlier work identifying the pathways for meaning circulation within a text (Paranyushkin Citation2011) and further developed by Shim, Park, and Wilding (Citation2015) and Nerghes et al. (Citation2015), we take into consideration two main centrality measurements in order to characterize the roles of the concepts within the KC networks: degree centrality and betweenness centrality (Freeman 1979). Degree centrality refers to the number of edges (direct links) a concept has with keywords. It measures the popularity of a concept within a certain domain or thematic area (i.e. a set of closely affiliated keywords). Betweenness centrality measures connectivity; that is, the extent to which a node can play a ‘brokerage’ role within the entire network. The higher this is, the more influential its role as a bridge for communication between different thematic areas that compose the network (Nerghes et al. Citation2015).

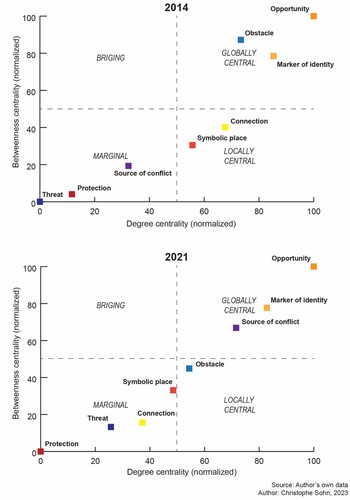

By crossing the two measurements of centrality, we obtain a categorization of the role of concepts into four types (). First, concepts that obtain high scores for the two centrality indices are globally central. In other words, they are highly connected (i.e. popular) and serve as bridge between different thematic areas at the scale of the semantic network. Second, concepts with high degree centrality and low betweenness centrality are locally central. They play a strong connective role, but their popularity is limited to a specific thematic area. Third, concepts that benefit from low degree centrality and high betweenness centrality play a bridging role. They connect different thematic areas, but are not popular. Lastly, concepts that present low degree centrality and low betweenness centrality are considered marginal. They do not play a significant role in the relational structure of the semantic network. In the empirical analysis, all centrality measurements were normalized, hence ranging between 0 and 100, to favour readability and to avoid biases due to differences in the density and size of the KC networks.

Table 3. Role of concepts in semantic networks.

Results

The evolution of the border’s framing

This first section is dedicated to an inductive content analysis of the keywords mentioned by the stakeholders in 2014 and 2021. The objective is to present the different framing categories mobilised by the actors and how they have evolved with the rebordering dynamic. presents the framing categories (shown in italics hereafter) identified according to the five trajectories presented earlier.

Table 4. Evolution of framing categories.

The categories that appear in 2021 refer to shortcomings associated with the border and the existence of a common identity. The first framing category can be related to the rebordering dynamic, as the keywords suggest. The ‘lack of trust’ or the fact that the border is depicted as ‘a regression of the EU spirit’ or a ‘political disappointment’ illustrates the extent of disenchantment experienced by the local stakeholders. For its part, referring to the border in terms of a common identity points to the place branding strategy that was initiated by the Öresund Committee and became a central focus for the CBC for Greater Copenhagen after 2015.

The framing categories that increase in their importance between 2014 and 2021 are issues, opportunities and the rigidity of the border. The two first categories regroup a significant proportion of keywords and point to the traditional ambivalence of borders, with on the one hand, the border being seen as ‘a risk’, ‘uncertainties’ or ‘problems’, and on the other, as offering ‘complementarities’, ‘possibilities’ or ‘new experiences’. In a context of rebordering, the increase of occurrences in the opportunity category may seem counter-intuitive. In reality, this fact shows the awareness of the actors as to the advantages that the border can offer when these are no longer taken for granted but called into question by the rebordering dynamic. As noted by a stakeholder interviewed: ‘border controls made us realize how important the cross-border opportunities are for the region.’Footnote13 Although less salient, increasing references to the rigidity of the border are another effect of the experienced rebordering dynamic.

The only category that remained stable between 2014 and 2021 refers to the materiality of the border (e.g. ‘water’). This stability can be explained by the lack of evolution of the spatial configuration of the borderline and its physical appearance between the two dates considered.

The framing categories for which the weighted occurrences diminish refer to the border in terms of a connection (both on a material and metaphorical level), the differences it highlights (e.g. ‘different cultures’ or ‘different laws and regulations’), the obsolescence of the border (e.g. ‘out of date’, ‘not really a border’ or ‘less relevant’), the fact that it is a barrier and to integration (e.g. ‘common labour market’ or ‘an integrated region’). The decline of the allusion to the border as a bridge seems to be a direct consequence of the reintroduction of border controls, as in practice the crossing of the border has become more difficult. At first glance, the diminution of descriptions relating to differences appears more surprising, insofar as real and perceived differences between the two sides of the border have not decreased between 2014 and 2021, quite the contrary with the reintroduction of border controls. By examining the keywords in detail, it seems that actors operated a shift in their framing: instead of simply pointing to the existence of differences, some of them preferred to mention the existence of issues, a way of highlighting their negative assessment of the developments that characterize the border. Such a substitution effect between framing categories might also explain the small diminution of keywords referring to the border as a barrier (preferably framed as issues in 2021).

Lastly, the framing categories that have disappeared refer to CBC and the proximity between the two sides (e.g. ‘brother/sister nations’). These categories in fact appear much less relevant with the reintroduction of border controls and mobility restrictions.

The relationships between concepts within the border’s semantic networks

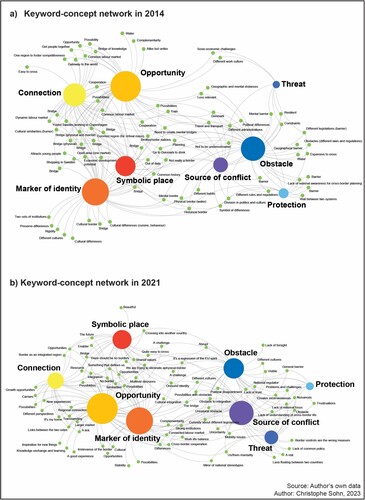

In this second section, we delve into the semantic network analysis of the Oresund’s border multiple aspects. In order to grasp the ways the different concepts associated with keywords relate one to another, and to identify changes induced by the rebordering dynamic, we have represented the graphs of the KC networks for 2014 and 2021 (see ).

As bipartite graphs, two types of nodes are represented: the keywords in green and the concepts in other colours. For the latter, warm colours (yellow to red) represent ‘positive’ or enabling meanings from a CBC perspective, whereas cold colours (blue to violet) represent ‘negative’ or constraining aspects. The size of the nodes representing the concepts corresponds to their degree centrality; in other words the number of associations with keywords mentioned by the stakeholders interviewed. Lastly, the network spatialization (i.e. the relative position of the nodes in the graph) is based on the ForceAltlas 2 algorithm, which works according to an attraction-repulsion principle: nodes repulse and edges attract (Jacomy et al. Citation2014). In essence, the spatial layout depends on the connections between nodes. Hence, the stronger the co-occurrences between two concepts (i.e. the fact that they are associated with the same keywords), the closer they appear in the graph.

The comparative analysis of the two graphs allows us to highlight the extent to which the closure of the border between Denmark and Sweden has changed the collective mental representations of CBC stakeholders. In 2014, the border as a connection and as an opportunity are closely related. The linking of the two sides of the border thanks to the Öresund bridge is associated with possibilities, such as the creation of a ‘common labour market’ or the promotion of ‘one region to foster competitiveness’. The same goes for the border as a marker of identity and as a symbolic place which are linked to common keywords such as ‘bridge’, a ‘cultural border’ or ‘cultural differences’. It should be noted that the existence of cultural differences on either side of the border is associated with questions of identity and symbolism and is not presented as an obstacle or a source of conflict. Opportunity and marker of identity show the highest degree centrality. These are the most popular concepts with actors, i.e. the ones they cite most often. The concepts that reflect negative aspects are located apart. The border as an obstacle and as a source of conflict are close, whereas the concepts of threat and of protection appear marginal and somewhat isolated. Obstacle is also important from a degree centrality perspective.

In 2021, the centrality of the concepts as well as their relative position appears to have changed. Opportunity is now closely related to marker of identity, whereas the border as a symbolic place, and particularly its meaning as a connection, appear disconnected and weaker. This latter change can clearly be attributed to the rebordering dynamic experienced since 2015. Despite these shifts in relative position within the semantic network, opportunity and marker of identity remain the most popular concepts in 2021. Among the concepts that depict negative aspects for CBC, one can note that obstacle, source of conflict and threat are closely related, whereas protection remains marginal and separate. One significant change is the increase of the degree centrality of source of conflict, and to a lesser extent threat. The rebordering dynamic experienced in the Öresund region rendered these concepts more popular among CBC stakeholders.

The changing role of the border’s concepts

This last section examines the roles of concepts within the KC semantic networks in 2014 and 2021 in order to deepen our understanding of the impact of rebordering on actors’ mental representations. represents the position of each concept according to the four types presented in .

In 2014, opportunity, marker of identity and obstacle are the three globally central concepts, which means that their influence spans the entire network. It is interesting to note the ambivalent understanding of the border by the CBC stakeholders. In addition to its ‘positive’ aspects, related to the opportunities it offers (e.g. the border as a bridge, a common labour market or differences in culture), obstacles are also considered to be a central feature (e.g. different rules and legislation, a physical barrier or mental distances). Marker of identity for its part refers mainly to the bridge. The border as a connection and as a symbolic place are locally central, which means that their influence is limited to a thematic area in the semantic network. Other meanings do not rely on these concepts to connect together. Lastly, source of conflict, protection and threat are marginal concepts that do not play a significant meaning circulation role in the network of 2014.

In 2021, after the series of border closures, opportunity and marker of identity are still considered globally central, whereas obstacle has become locally central, replaced by source of conflict as a third global concept. The stability of opportunity and marker of identity as central concepts for the entire semantic network underline the resilience of such meanings in the mental representations of CBC stakeholders, despite the border closures. These two concepts are at the core of the regional identity of the Öresund region and its image. The growing importance of source of conflict together with the relative decline of obstacle in the mental representations of the CBC actors can be interpreted as a substitution effect triggered by the rebordering dynamic. With the reintroduction of border controls, certain aspects related to border-induced differences (such as legislative and political differences) have become sources of conflict. Diverging views concerning the measures to be implemented to fight the pandemic have played a role in polarizing feelings and identities. As noted by a Swedish stakeholder:

Before the pandemic, we had different legislations, regulations and taxes, but we coped with that as long as you could go to the other side. But when the politicians decided to close the border, we saw these feelings of ‘us’ against ‘them’ coming back. This nationalistic mentality is the most dangerous aspect.Footnote14

Conclusions

This study sought to contribute to the literature on CBC in a context of rebordering. In particular, it aimed to show the extent to which the reintroduction of border controls within the Öresund cross-border region is changing the meaning that local stakeholders give to the national border within the framework of their regional cooperation. In doing so, the study also sought to highlight the utility of semantic network analysis for identifying ideational changes in the mindset of actors concerning the role and significance of borders.

Different ideational shifts were identified with regard to the impact of rebordering on CBC actors’ border discourse. First, the content analysis of keywords mentioned by the CBC actors to describe what the border means to them shows an increase in references to shortcomings related to the border and the disappointment resulting from the reintroduction of border controls. There is a clear increase in the occurrences of keywords referring to the border as being an issue, as well as to its rigidity. At the same time, keywords pointing to the border as a connection and as being obsolete have diminished, whereas framings referring to CBC and to proximity (between the two sides of the border) have disappeared. Alongside these altogether expected descriptions, it should be noted that the opportunities offered by the border and the presence of a common regional identity are more often highlighted by the actors interviewed in 2021 than in 2014. The rebordering dynamic therefore seems to have brought to the fore the ambivalent dimension of the border, conceived both as a constraint and as an opportunity.

Second, and in order to deepen our understanding of the conceptual changes that occurred in the mental representations of CBC actors following the border closure, a semantic network analysis was carried out. The objective was to capture the meaning of the border in its multiplicity – namely, a relational perspective as to the overall significance of the border in which its different understandings are articulated to each other. Beyond the frequency of each concept, its presence or its absence, we argued that it is the relations between them that matter. Hence, whereas in 2014 the concept of opportunity was closely linked to that of connection, after the reintroduction of border controls, border-related opportunities became associated with the question of the regional identity of the Öresund region. This change of association can be interpreted in different ways. On the one hand, it denotes a decrease in the importance given to the connective role of the border, which seems to be a direct effect of its closure and the increased difficulties in crossing it in recent years. The downplaying of the meaning of the border as a connection is particularly significant for the Öresund region, because the bridge has been one of the key drivers that has underpinned CBC and the integration of the two sides of the border over the last two decades (both in a functional and a symbolic way). On the other hand, the association between border-related opportunities and the question of a common regional identity can also be seen as one of the consequences of the change in orientation of CBC as promoted by the Greater Copenhagen Committee. Greater Copenhagen's revamped place branding strategy developed from 2016 could therefore have played the role of a confounding factor in the vision of the border as an opportunity to strengthen regional identity. Another significant ideational shift at the level of semantics is the increasing importance of the concept depicting the border as a source of conflict, evolving from a marginal role in 2014 to globally central in 2021. The fact that the border is seen more as a source of conflict than an obstacle reflects an increase in divergences and a certain polarization of feelings, which are directly linked to the rebordering experienced. It is this development that arouses the most concern on the part of CBC stakeholders, understandably because it is a direct threat to the cross-border integration process of the Öresund region and the promotion of a shared vision for its future development. In the end, it is as if the temporary closure of the border had heightened the awareness of the actors as to the importance of the opportunities linked to the border for the economic growth and the attractiveness of the cross-border region, but also of the constraints – in particular, the challenges and divergences that it is likely to institute and reproduce.

As far as the impact of these ideational changes on CBC is concerned, we can only speculate at this stage. On the one hand, there is a source of hope that the actors will invest in the field of the CBC in a renewed way because the border is still perceived as an opportunity for the Öresund region, in spite of the challenges encountered. This alludes to a certain form of ideational resilience with regard to the way in which the border is understood despite the rebordering experienced. In addition, the successive border closures have made actors aware of certain shortcomings, as well as of the changes that appear necessary from now on, so that such situations do not recur in the future. Political willingness to further remove border obstacles and strengthen cross-border regional integration could therefore give new impetus to the CBC in the years to come. On the other hand, the future trajectory of the CBC will also depend on the longer or shorter persistence of visions that see the border as a source of conflict and as a threat. Unfortunately, our study does not allow us to state whether the prominence gained by these aspects is temporary or lasting.

With regard to the use of semantic network analysis as a suitable method to grasp borders’ multiplicity, the results obtained confirm that the representation and analysis of the relationships between concepts constitutes a meaningful approach to study actors’ border discourses and identify ideational shifts. Moreover, the convergence of the results between semantic network analysis and content analysis underlines the robustness of the former. Of course, the proposed method does not aim at replacing in-depth qualitative ethnographic viewpoints. Those methodologies remain essential when it comes to delving into the complexities of border-making processes and providing contextualized and in-depth understandings of what borders mean. The analysis of semantic networks mobilizing ad hoc data collected via interviews with actors offers an alternative way to come to grips, in a comprehensive and relatively simple manner, with the evolution of ideas and discourses not yet formalized in text documents. Beyond these advantages, there are also limitations that need to be acknowledged and that could be tackled in future research.

A first shortcoming in our analysis of ideational changes in border discourses relates to the use of diachronic analysis to capture what is essentially a dynamic process. Using two ‘snapshots’ is of course not sufficient to assess the durability of the changes identified. To know whether we are looking at temporary variations or more profound shifts, a third campaign of interviews carried out in a few years would be necessary. In addition, there is also the question of the period considered. Depending on the moments chosen to carry out the interviews, the mental representations of the actors may vary due to the influence of current affairs events or other phenomena. Although it is in fact difficult to assess the contextual sensitivity of the analyses performed, some additional insights gained through open-ended questions during the interviews make it possible to check the validity of the analyses. A second limitation relates to the identification of the actors interviewed. If, in our study, the saturation of the targeted policy domain seems satisfactory (most of the important organizations were able to be included in our survey), the question of the gap between the mental representations of individuals and the official views assumed by the organizations they represent is posed. Given the high turnover in executive positions, we did in fact interview different individuals representing the same organizations between 2014 and 2021. Hence, individuals’ understanding of the meaning of the border may be influenced by factors that have nothing to do with the border closures, but with personal aspects, such as people's private and professional trajectories, particular experiences that give a unique tone to their understanding of the border, etc. A third issue points at the existence of confounding variables that may distort the association made between the rebordering dynamic and the ideational changes in actors’ discourses. For instance, the effects attributable to the border closures and those that emanate from the events that led to these decisions (i.e. the ‘European refugee crisis’, cross-border crime and the COVID-19 pandemic) could not be distinguished in the context of this exploratory study. The same goes for other events that may have impacted the ways actors understand the border such as the relaunch of CBC under the impetus of the Greater Copenhagen initiative. Lastly, a fourth limitation relates to the influence of methodological choices on the results (Carley Citation1993). In particular, the definition of the set of concepts mobilized and the coding approach chosen in order to associate keywords with concepts definitely influenced the results. The identical reproduction of the survey and the analysis protocol between the two dates observed nevertheless makes it possible to guarantee the internal validity of the results. With regard to their external validity, more studies of this type considering different contexts would be needed, which this paper ultimately calls for.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the persons interviewed in the Öresund region in 2014 and 2021. Their participation in the interviews and their responses to the questions posed were an invaluable source of information that made this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There are obviously many text documents likely to reflect the meaning of the border from the point of view of CBC actors dating from before the reintroduction of border controls. Due to some institutional inertia, more recent documents published after the border closures are, however, still scarce, which makes the use of these sources of information problematic.

2 In this paper, we use the name ‘Öresund region’ to refer to the geographical entity, although some actors — especially on the Danish side — prefer the more recent name of ‘Greater Copenhagen’. As noted by Christer Persson (interviewed on 11 November 2021), Greater Copenhagen stands more as a place brand and organization, whereas the Öresund region entails a larger idea.

3 Interview with a CBC officer at the City of Malmö, 8 November 2021.

4 Interview with an executive of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Southern Sweden, 8 November 2021.

5 Interview with an officer of the City of Malmö, 8 November 2021.

6 Interview with an executive of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Southern Sweden, 8 November 2021.

7 Interview with the executives of the Öresund Institute, 7 December 2021.

8 Hidden to preserve double-blind peer-review.

9 Concerning research ethics, all interviews were conducted within the framework of informed consent. The two interview campaigns were conducted within the framework of the X and Y projects and approved by the ethical committee of [Z] (names of projects and institution are hidden for peer-review purposes).

10 The weighted occurrence corresponds to the sum of the keywords taking into account their stated importance (i.e., 1, 2 or 3).

11 KC networks were preferred to the version transformed into concept-by-concept (CC) networks in order to be able to include the keywords in the graphs. The relational structure of the concepts is similar in the KC and the CC graphs.

12 Two types of network analysis software were used: UCINET for statistical analysis (notably the centrality measures) and Gephi for the visual representation of graphs.

13 Interview with an executive of the Oresund Institute, 7 December 2021.

14 Interview with an executive of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Southern Sweden, 8 November 2021.

References

- Agnew, J. 2008. “Borders on the Mind: Re-Framing Border Thinking.” Ethics & Global Politics 1 (4): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3402/egp.v1i4.1892.

- Andersen, D. J., M. Klatt, and M. Sandberg. 2012. The Border Multiple: The Practicing of Borders Between Public Policy and Everyday Life in a Re-Scaling Europe. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Andersen, D. J., and E.-K. Prokkola. 2021. Borderlands Resilience: Transitions, Adaptation and Resistance at Borders. London: Routledge.

- Andersen, D. J., and M. Sandberg. 2012. “Introduction.” In The Border Multiple. The Practicing of Borders Between Public Policy and Everyday Life in a Re-Scaling Europe, Border Regions Series, edited by D. J. Andersen, M. Klatt, and M. Sandberg, 1–19. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Anderson, J., and L. O’Dowd. 1999. “Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance.” Regional Studies 33 (7): 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078648.

- Axelsson, L. 2022. “Border Timespaces: Understanding the Regulation of International Mobility and Migration.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2027260.

- Balibar, E. 2002. Politics and the Other Scene. London: Verso.

- Blyth, M. 2002. Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Böhm, H. 2021. “The Influence of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Czech-Polish Cross-Border Cooperation: From Debordering to Re-Bordering?” Moravian Geographical Reports 29 (2): 137–148. https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2021-0007.

- Böhm, H. 2023. “Five Roles of Cross-Border Cooperation Against Re-Bordering.” Journal of Borderlands Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.1948900.

- Brambilla, C. 2015. “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept.” Geopolitics 20 (1): 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884561.

- Carley, K. 1993. “Coding Choices for Textual Analysis: A Comparison of Content Analysis and Map Analysis.” Sociological Methodology 23: 75–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/271007.

- Carley, K., and M. Palmquist. 1992. “Extracting, Representing, and Analyzing Mental Models.” Social Forces 70 (3): 601–636. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579746.

- Casella Colombeau, S. 2020. “‘Crisis of Schengen? The Effect of two ‘Migrant Crises’ (2011 and 2015) on the Free Movement of People at an Internal Schengen Border (2011 and 2015) on the Free Movement of People at an Internal Schengen Border’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (11): 2258–2274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1596787.

- Celata, F., R. Coletti, and A. Stocchiero. 2017. “Neighborhood Policy, Cross-Border Cooperation and the Re-Bordering of the Italy–Tunisia Frontier.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 32 (3): 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1222872.

- Danowski, J. A. 1993. “Network Analysis of Message Content.” In Progress in Communication Sciences XII, edited by G. Barnett, and W. Richards, 197–222. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- De Somer, M. 2020. “Schengen: Quo Vadis?” European Journal of Migration and Law 22 (2): 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12340073.

- De Sousa, L. 2013. “Understanding European Cross-Border Cooperation: A Framework for Analysis.” Journal of European Integration 35 (6): 669–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2012.711827.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1): 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- European Commission. 2022. ‘Member States’ Notifications of the Temporary Reintroduction of Border Control at Internal Borders Pursuant to Article 25 et Seq. of the Schengen Borders Code’. European Commission. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/schengen-area/temporary-reintroduction-border-control_en.

- Evrard, E., B. Nienaber, and A. Sommaribas. 2020. “The Temporary Reintroduction of Border Controls Inside the Schengen Area: Towards a Spatial Perspective.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 35 (3): 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1415164.

- Freeman, L. 1978. “Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification.” Social Networks 1 (3): 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7.

- Gülzau, F. 2023. “A “New Normal” for the Schengen Area. When, Where and Why Member States Reintroduce Temporary Border Controls?” Journal of Borderlands Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.1996260.

- Herzog, L. A., and C. Sohn. 2014. “The Cross-Border Metropolis in a Global Age: A Conceptual Model and Empirical Evidence from the US–Mexico and European Border Regions.” Global Society 28 (4): 441–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2014.948539.

- Hooper, B. 2004. “Ontologizing the Borders of Europe.” In Cross-Border Governance in the European Union, edited by B. Hooper, and O. Kramsch, 209–229. London: Routeledge.

- Hospers, G.-J. 2006. “Borders, Bridges and Branding: The Transformation of the Øresund Region Into an Imagined Space.” European Planning Studies 14 (8): 1015–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310600852340.

- Ierna, C. 2012. “‘La Notion Husserlienne de Multiplicité: Au-Delà de Cantor et Riemann’. Translated by Claudio Majolino.” Méthodos 12 (April), https://doi.org/10.4000/methodos.2943.

- Jacomy, M., T. Venturini, S. Heymann, and M. Bastian. 2014. “ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software.” PLOS ONE 9 (6): e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

- Jones, R. 2012. Border Walls: Security and the War on Terror in the United States, India, and Israel. London: Zed Books.

- Kajta, J., and E. Opiłowska. 2022. “The Impact of Covid-19 on Structure and Agency in a Borderland. The Case of Two Twin Towns in Central Europe.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 37 (4): 699–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.1996259.

- Kaucic, J., and C. Sohn. 2022. “Mapping the Cross-Border Cooperation ‘Galaxy’: An Exploration of Scalar Arrangements in Europe.” European Planning Studies 30 (12): 2373–2393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1923667.

- Klatt, M. 2020. “The So-Called 2015 Migration Crisis and Euroscepticism in Border Regions: Facing Re-Bordering Trends in the Danish–German Borderlands.” Geopolitics 25 (3): 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1557149.

- Koch, K. 2018. “Geopolitics of Cross-Border Cooperation at the EU’s External Borders.” Nordia Geographical Publications 47 (1), https://nordia.journal.fi/article/view/71008.

- Kolossov, V., and J. Scott. 2013. “Selected Conceptual Issues in Border Studies.” Belgeo 1 (November), https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.10532.

- Krichker, D. 2021. “Making Sense of Borderscapes: Space, Imagination and Experience.” Geopolitics 26 (4): 1224–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1683542.

- Krippendorff, K. 1980. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Lara-Valencia, F., and J. P. Laine. 2022. “The Covid-19 Pandemic: Territorial, Political and Governance Dimensions of Bordering.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 37 (4): 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2022.2109501.

- Leifeld, P. 2017. “Discourse Network Analysis.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Networks, edited by J. N. Victor, A. H. Montgomery, and M. Lubell, 301–326. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Löfgren, O. 2008. “Regionauts: The Transformation of Cross-Border Regions in Scandinavia.” European Urban and Regional Studies 15 (3): 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776408090418.

- Mahoney, J., and K. Thelen. 2010. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Matthiessen, C. W. 2004. “The Öresund Area: Pre- and Post-Bridge Cross-Border Functional Integration: The Bi-National Regional Question.” GeoJournal 61 (1): 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-005-5234-1.

- Medeiros, E., M. Guillermo Ramírez, G. Ocskay, and J. Peyrony. 2021. “Covidfencing Effects on Cross-Border Deterritorialism: The Case of Europe.” European Planning Studies 29 (5): 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1818185.

- Molema, M. 2021. “Bright Ideas, Thick Institutions. Post-Industrial Development Theories as Drivers of Cross-Border Cooperation.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 36 (1): 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2018.1496467.

- Montaldo, S. 2020. “The COVID-19 Emergency and the Reintroduction of Internal Border Controls in the Schengen Area: Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste.” European Papers 5 (1): 523–531.

- Murphy, A. B. 2022. “Taking Territory Seriously in a Fluid, Topologically Varied World: Reflections in the Wake of the Populist Turn and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104 (1): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.2022987.

- Nerghes, A., J.-S. Lee, P. Groenewegen, and I. Hellsten. 2015. “Mapping Discursive Dynamics of the Financial Crisis: A Structural Perspective of Concept Roles in Semantic Networks.” Computational Social Networks 2 (16): 1–29.

- Newman, D. 2006. “The Lines That Continue to Separate us: Borders in our `Borderless’ World.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph599xx.

- Noferini, A., M. Berzi, F. Camonita, and A. Durà. 2020. “Cross-Border Cooperation in the EU: Euroregions Amid Multilevel Governance and Re-Territorialization.” European Planning Studies 28 (1): 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1623973.

- O’Dowd, L. 2002. “The Changing Significance of European Borders.” Regional & Federal Studies 12 (4): 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004774.

- OECD. 2013. Regions and Innovation: Collaborating Across Borders. Paris: OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation.

- Opiłowska, E. 2021. “The Covid-19 Crisis: The End of a Borderless Europe?” European Societies 23 (sup1): S589–S600. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1833065.

- Paasi, A. 1998. “Boundaries as Social Processes: Territoriality in the World of Flows.” Geopolitics 3 (1): 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650049808407608.

- Paranyushkin, D. 2011. ‘Identifying the Pathways for Meaning Circulation Using Text Network Analysis’. Nodus Labs. https://noduslabs.com/research/pathways-meaning-circulation-text-network-analysis/.

- Perkmann, M. 2007. “Policy Entrepreneurship and Multilevel Governance: A Comparative Study of European Cross-Border Regions.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (6): 861–879. https://doi.org/10.1068/c60m.

- Persson, C, and H.-Å. Persson. 2021. The Oresund Experiment. Making a Transnational Region. Ystad: Ängavången AB.

- Peyrony, J., J. Rubio, and R. Viaggi. 2021. ‘The Effects of COVID-19 Induced Border Closures on Cross-Border Regions: An Empirical Report Covering the Period March to June 2020.’ Luxembourg: European Commission, Mission Opérationnelle Transfrontalière. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2776342537.

- Prokkola, E.-K. 2019. “Border-Regional Resilience in EU Internal and External Border Areas in Finland.” European Planning Studies 27 (8): 1587–1606. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1595531.

- Radil, S. M., J. Castan Pinos, and T. Ptak. 2021. “Borders Resurgent: Towards a Post-Covid-19 Global Border Regime?” Space and Polity 25 (1): 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2020.1773254.

- Rajaram, P. K., and C. Grundy-Warr. 2007. Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge (Vol. 29). Borderlines, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rumford, C. 2008. Citizens and Borderwork in Contemporary Europe. London: Routledge.

- Schmidt, T. D. 2005. “Cross-Border Regional Enlargement in Øresund.” GeoJournal 64 (3): 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-006-6874-5.

- Scott, J. W. 2012. “European Politics of Borders, Border Symbolism and Cross-Border Cooperation.” In A Companion to Border Studies, edited by T. M. Wilson, and H. Donnan, 83–99. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Segev, E. 2021. Semantic Network Analysis in Social Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Shim, J., C. Park, and M. Wilding. 2015. “Identifying Policy Frames Through Semantic Network Analysis: An Examination of Nuclear Energy Policy Across Six Countries.” Policy Sciences 48 (1): 51–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-015-9211-3.

- Sohn, C. 2016. “Navigating Borders’ Multiplicity: The Critical Potential of Assemblage.” Area 48 (2): 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12248.

- Stoffelen, A. 2022. “Managing People’s (in)Ability to be Mobile: Geopolitics and the Selective Opening and Closing of Borders.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (1): 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12486.

- Svensson, S. 2022. “Resistance or Acceptance? The Voice of Local Cross-Border Organizations in Times of Re-Bordering.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 37 (3): 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1787190.

- Vallet, E. 2016. Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity? London: Routledge.