ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to analyse conflicting landscape associations linked to nature parks. Drawing from an R&D project in one of the largest former wetlands in Denmark, we examine how diversified landscape perceptions and conflicting landscape preferences result from and condition the re-enchantment of nature parks for tourism development. The case study relies on various procedures. First, a combination of local accounts and fieldwork observations of tourism and landscapes. Second, interviews with tourists and local stakeholders on processes of engagement and disengagement with conservation, restoration, and re-wilding processes. Third, collaborative mapping with local stakeholders and citizens and their imaginaries of local nature. By combining literature reviews with findings from the case study, we derive different social imaginaries among tourism entrepreneurs, property owners, farmers, industrial actors, local citizens, and NGOs. Six conflicting landscape imaginaries are identified that, to varying degrees, may apply to other nature parks. Each approach holds different human-nature relations and views on what needs to be sustained locally, and what landscapes need to be developed. We conclude that conflicting positions and preferences over landscapes (geo-positionalities) may hinder interventions for sustainable transition, and that mapping these landscape positionalities may be useful for deliberation in tourism development initiatives.

1. Introduction

This paper deals with the rise of new conflicting landscape associations linked to nature-based tourism development. Tourism represents a type of commodification of nature (Büscher and Fletcher Citation2017; Katz Citation1998) whose economic importance has increased during recent decades (Margaryan and Fredman Citation2017; Matilainen and Lähdesmäki Citation2014; Rytteri and Puhakka Citation2016). The growth of tourism entails a number of classic negative impacts on biodiversity, local societies, farming, cultural heritage, and environmental degradation, given tourism’s structural violence to local people and the land (Buckley Citation2012; Büscher and Fletcher Citation2017). Yet, in rural areas such issues and standpoints often coexist with tourism as a strategy through which local development of peripheral communities (Bærenholdt and Grindsted Citation2021) is sought by highlighting the area’s rich natural resources and landscapes, among other ways.

Such paradoxes and dilemmas typically involve local conflicts, upholding different meanings and pressures on what to sustain and what to develop. In this paper we argue that while tourism is often acknowledged as a development strategy in peripheral communities, conflicting landscape imaginaries will arise not necessarily due to top-down planning or business-driven goals but be mutually co-dependent on structural as well as local driving forces.

Insofar as nature-based tourism has gradually been recognized as an important rural development strategy (Bærenholdt and Grindsted Citation2021; Salvatore, Chiodo, and Fantini Citation2018), a number of underlying pre-conditions and circumstances are fundamentally intertwined with multiscalar dynamics: urban centralization (Olesen and Richardson Citation2012), transformative urban-rural links including the decline of economic activity in rural areas (Dicken and Thrift Citation1992), agricultural and industrial dynamics (Van der Ploeg Citation2018), depopulation and ecological injustice (Rudolph and Kirkegaard Citation2019), counter-urbanization and relative income (Andersen et al. Citation2022), rearrangement of public institutional goods (schools, childcare, hospitals), deterioration of local retail functions, jobs, and social activities (Bærenholdt, Fuglsang, and Sundbo Citation2021), the increasing role of the experience economy (e.g. Sundbo and Sørensen Citation2013), and the reinvention of the importance of wetlands, nature, and more (Farstad et al. Citation2022; Krauss, Zhu, and Stagg Citation2021). However, conflicting landscape associations and their geo-positionalities when place developments are initiated have not been studied in nature parks, where efforts are directed at making tourism an integral part of rural development strategies, not least by enhancing biodiversity, climate, and nature conservation agendas.

Climate change (IPCC Citation2021), biodiversity, and the function of wetland carbon sinks (European Commision Citation2021; IPCC Citation2014) may be coupled with local nature tourism strategies in nature parks. Yet local responses in rural areas influenced by national or international policies may not resonate with such agendas. While EU and national policies (Danish Government Citation2023) recognize the need for nature restoration, i.e. of wetlands, bogs, marshes, and lowlands to mitigate the worst effects of global environmental change (Blondet et al. Citation2017), local communities may embrace them, oppose them, or even accelerate conflicts between local stakeholders when confronted with potential land use interventions.

Within this context, the paper follows the trend of nature-based tourism studies in examining local nature-based tourism development together with local actors characterized by family enterprises, often with hidden economic motives, and value-oriented goals (Fletcher et al. Citation2019; Lundberg, Fredman, and Wall-Reinius Citation2014; Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2021). We are also influenced by studies and strategies on greening tourism, and environmental consciousness, and we relate to studies and strategies on sustainable transition potentials (Haisch Citation2019; Kaae et al. Citation2019; Lundberg, Fredman, and Wall-Reinius Citation2014; Meged and Holm Citation2022; Saarinen and Gill Citation2019). Furthermore, we draw from political ecology and the social nature approach (Castree Citation2001; Castree and Braun Citation2006; Katz Citation1998; Van der Ploeg Citation2018) in which natural processes and landscape transformations are social in character.

Tourism strategies as perceived solutions to structural dynamics and strategies for local development also coincide with presumed sustainability paths. By way of illustration, Lordkipanidze, Brezet, and Backman (Citation2005), Fletcher et al. (Citation2019), and Holm, Cold-Ravnkilde, and Grindsted (Citation2020) examined the role of tourism actors and how such entrepreneurial actors impact land-use in different destinations and set sustainability targets. Different imaginaries of natural landscapes and how these relate to tourism’s role in nature park developments have been less explored (Benediktsson Citation2016; Hoogendoorn et al. Citation2019; Koninx Citation2019), particularly in relation to naturalization, denaturalization and renaturalization processes. Yet, as tourism extends into more nature-rich areas, among other means by commodifying them (Katz Citation1998; Rytteri and Puhakka Citation2016), there is an increasing need to understand the characteristics, possibilities, and role of nature-based tourism in natural restoration, conservation, or re-wilding efforts (Kaae et al. Citation2019). Local conflicting forces and views between stakeholders and their perception and preference on landscapes here unpack the structural impact on the environment (Bryan Citation2015; Büscher and Fletcher Citation2017; Jasanoff and Kim Citation2015). We therefore have an interest in understanding where existing local landscape positions may be opened for biodiversity and climate mitigation alongside the development of tourism in Danish nature parks. Consequently, we ask what characterizes different local actors’ various landscape positions for rewilding, preserving, restoring, or remanufacturing natural landscapes. We thus aim to produce knowledge for pertinent approaches in local nature park developments with combined tourism and biodiversity/climate mitigation agendas. The empirical basis consists of a case study on a four-year R&D project with diverse experience-related development efforts in the Danish Åmosen Nature Park (NPÅ), a rural, partly farming based nature area, the third largest peatland and the largest drained peatland in Denmark. NPÅ can be considered a case in point of conflicting viewpoints over what should be developed and what should be sustained in future land use transformations.

The paper proceeds in five sections. The following Section 1.1 sets out the concept and context of nature park. Section 2 explains the theoretical approach combining nature tourism studies with the production of nature theory. Section 3 explains the methods. The results section (Section 4) presents six conflicting landscape configurations and explains their characteristics in a nature park context. Finally, we discuss how nature tourism developments intertwine with a complex of conflicting landscape positions that, among other things, impact sustainable landscape transformations.

1.1. Research area – the case of Åmosen Nature Park

Denmark is a highly intensified agricultural country and multiple stressors intensify the need for land, not only due to demands from tourism and recreation (Salvatore, Chiodo, and Fantini Citation2018), industry and agriculture, urbanization, and more, but increasingly from mitigating climate change and biodiversity collapse, and the promotion of bioenergy, wind, and solar energy farms (Concito Citation2023; Rudolph and Kirkegaard Citation2019). In short, environmental sustainability and biodiversity agendas (e.g. EU Common Agricultural Policy) require policy-driven land use in transition (Arler et al. Citation2017; Gustafsson, Hermelin, and Smas Citation2019; Hermoso et al. Citation2022; IPCC Citation2014). Denmark is different from many other countries, as nature-rich areas and parks are often owned by private landowners, and planning restrictions are no different from areas outside nature parks, such as those concerning farming, building, nature protection, etc. (Ministry of the Environment Citation2022). Consequently, none of the Danish nature parks are solely natural landscapes but intertwined spaces of nature, infrastructure, housing, farming, cities, and services. By way of example, a nature park may be located within a Ramsar or NATURA 2000 site, but the same regulation applies outside the areas. Nature on public property is restricted by commercial tourism activities, and the same law applies within the parks. In contrast to a national park, nature parks are not benefited by either legislative power or finance by the Government. Thus a nature park operates as a volunteer organization with little authority or public funding (Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2020). Furthermore, nature parks are highly intensified landscapes in comparison to other European parks, and no nature park in Denmark subscribes to one of the 51 ecolabels of protective measures for parks (Ecolabel Index Citation2023; Holm Citation2017). NPÅ has around 1900 landowners. Approximately 97% of the total area of the nature park is privately owned. Some 2500 other citizens also live in the nearest surrounding area. The park and surroundings are characterized by a few exceptionally large property owners (of the total of about 1900), with farming and forestry as predominant activities. The case area has little tourism and limited accommodation, tourism entrepreneurs and commercialized attractions (Cold-Ravnkilde, Holm, and Grindsted Citation2021; Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2020). NPÅ estimates it receives around 10,000 visitors a year, of whom the majority are from the upland areas. Moreover, the area is subject to rural trends of industrial decline, job losses, high unemployment, and fewer highly educated people (Andersen et al. Citation2022). The area is gradually being depopulated, with regional urbanization taking place primarily in the larger cities in the vicinity of the area (see Appendix 1).

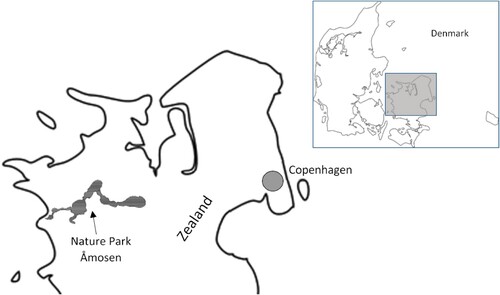

NPÅ is the third largest peatland and the largest drained peatland in Denmark with a 524 km2 watershed, lowlands, and carbon-rich soils and more than 8000 ha of land (see Appendix 2). With gradual drainage from the 1800s onwards, and most extensively between the 1930s and the 1960s, the biodiversity profile as well as the climate impact due to land drainage has changed dramatically in the case area.Footnote1 Nationally, such low-lying areas and wetlands contribute to half of the agricultural sector’s land-use-based greenhouse gas emissions in Denmark (Greve et al. Citation2020; Gyldenkærne and Greve Citation2015). Map 1 illustrates the case area of the nature park.

2. Theory

Three bodies of literature frame the theoretical approach. One is positioned within the stream of nature-based tourism studies (e.g. Benediktsson Citation2016; Hoogendoorn et al. Citation2019; Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2021), particularly focusing on studies linking sustainability agendas and rural community development (e.g. Bærenholdt, Fuglsang, and Sundbo Citation2021; Haisch Citation2019; Huijbens Citation2012; Kaae et al. Citation2019). Second, we draw from the social nature approach (Castree Citation2013; Katz Citation1998; Kirsch and Mitchell Citation2004) related to the production of nature and the political ecologies of naturalization, re-naturalization, and denaturalization (Castree and Braun Citation2006; Van der Ploeg Citation2018) and what Katz (Citation1998) has labelled ‘restoration’ versus ‘preservation’ strategies in her studies of nature park transformations. Finally, we draw upon Jasanoff’s concept of sociotechnical imaginaries from 2009 and re-articulated later by Jasanoff and Kim (Citation2013; Citation2015): the role of imagining the technological future (cultivated landscape, in this case) as a crucial constructive element in social life. It relates to collective beliefs about how society functions – these sociotechnical imaginaries as phenomena could be articulated and propagated by local, regional, and global actors (Jasanoff and Kim Citation2015).

We will argue that these three bodies of literature will help to explore the role and dynamics of conflicting images of landscapes within the same geographic area. We thus develop geo-positionalities inspired in Sheila Janasoff and Kim’s (Citation2009) work on imaginaries. Imaginaries are the blurred or intertwined way we see, understand, hope for and desire things around us, such as landscapes, typically conflicting with other utilization, economic, aesthetic, or symbolic agendas. Thus geo-positionalities refer to a positionality relating to imaginaries, hopes, visions, and desires over a landscape and a positionality relating to the geopolitics, motivation, or belief of transforming such landscapes. Hence, geo-positionalities hold collective imaginaries, sometimes conflicting over the same place.

Agriculture, forestry, and industrial demands often conflict with nature conservation (Van der Ploeg Citation2018) and tourism (Bostedt and Mattsson Citation1995; Citation2006). According to the production of nature theory (Castree and Braun Citation2006), such nature conflicts reside in economic utilization of natural entities, for instance where landowners seek profit from agricultural activities, as does the gradual tourist commodification of nature scenery (Kaltenborn, Haaland, and Sandell Citation2001).

Structurally, tourism entrepreneurs are often dependent on other local interest groups. Access to nature is a prerequisite for nature-based tourism companies but is often controlled by landowners. By way of illustration, Puhakka (Citation2008) identifies different discourses related to tourism in national parks in Finland, including integration of nature-based tourism and conservation versus practices that stress greater economic utilization of nature. Other local interest groups include local people and voluntary organizations, local planners, and politicians who may perceive nature tourism as an economic development potential, whereas other citizens find it a threat to their lifestyle and local aspirations (Matilainen and Lähdesmäki Citation2014).

However, in some areas the relation between tourism and nature conservation works well (Mace Citation2014; Margaryan Citation2012) and not all stakeholders in rural communities within tourism, farming and beyond seek high profits or follow the logic of mainstream management literature (Fletcher et al. Citation2019). Many nature-based tourism entrepreneurs, for instance, are driven by values such as being close to nature, authenticity, sustainability, and environmental responsibility (Genovese et al. Citation2017) and/or they seek alternative lifestyles or pursue personal interests (Haisch Citation2019; Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2021). Similar values thrive among stakeholders in recreational and nature sport activities, tourist guides, NGOs and even small farmers; they are manifest by actors often opposed to profit and growth (Lundberg, Fredman, and Wall-Reinius Citation2014; Saarinen and Gill Citation2019). In some cases, the aim of building a nature tourism enterprise is to maintain a life in the countryside, for example by turning a family farm into a nature holiday farm (Genovese et al. Citation2017).

The development of nature tourism also attracts external actors’ interests. In addition, university-based researchers may, as in the case of this article, be involved in nature tourism development initiatives in their own way for the benefit of plural jobs, ecological and social interests, often through funded research and development projects. Both researchers and their funders may have their own sets of interests and objectives (Grindsted Citation2018).

Thus, nature tourism development attracts and relies on a complex of actors who all have direct or indirect interests in nature tourism and in the nature and landscapes that are the core resources of nature tourism (Fredman and Tyrväinen Citation2010). Although different actors demand quite different landscapes and manipulated natures, tourism can be a practice of nature usage which supports preservation interests (Margaryan Citation2012), but also different tourism actors’ business approaches may coexist with industrial, forestry and agricultural production (Genovese 2017; Mace Citation2014).

Different degrees of locally based positions and observations of development potentials will thus be expected to be found among the nature tourism actors, even though they may all subscribe to a sustainability discourse (Lundberg, Fredman, and Wall-Reinius Citation2014; Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2021). As illustrated below, this can be the case in nature parks where different stakeholders all advocate for sustainability by targeting different landscape formations and their associated natures within the same park.

Drawing from Castree and Braun (Citation2006), we build our analysis on the understanding that different local actors have varying ways of utilizing rural landscapes as operand or operant values for different purposes, ranging from extensive land use to the transformation of landscape and the environment into added value. But emotional, experiential, aesthetic and intrinsic nature aspirations are also at stake (Benediktsson Citation2016). The resulting constructions of rural landscape positions and their associated nature(s) are also intimately related to the development of new and conflicting landscape uses. While conflicting landscape imaginaries often emerge when large investment efforts are to transform rural areas, in contrast to Iannucci, Martellozzo, and Randelli (Citation2022) we argue that the soft commoditization of nature as a leisure and tourism resource also results in the rise of new landscape imaginaries in an increasingly complex ‘landscape’ of conflicting local positions and preferences. We argue that mapping these geo-positionalities is important to identify options for new tourism-related ecologies and to avoid conflicting nature tourism development initiatives. Research and development efforts, such as our own, should also be aware of hidden or conscious landscape positions and preferences.

3. Methodology

The empirical material is based on a case study. The case is spatially delimited to the nature park’s area (see Map 1) but also integrates (more arbitrarily) actors operating in the immediate vicinity of the park. Furthermore, the case study took place over four years in an R&D project with diverse experience-related development efforts in the Danish Åmosen Nature Park. The R&D project aimed to study nature park and tourism development in the area, and how different actors position socio-natures in relation to the nature park.

Actors that have a direct relation to tourism development in NPÅ and an impact on it, including property owners, local citizens and visitors, private tourism and non-tourism entrepreneurs, relevant public, semi-public and voluntary organizations, are all part of the study. To include various conflicting landscape images and stakeholder interests in utilizing the landscape and nature in the park, we draw from the cultural-politics-of-nature approach to studying local citizens living with the landscapes (Castree Citation2014; Castree and Braun Citation2006). This approach is taken in order to become deliberately involved in getting a grounded understanding of how local practices and living with nature evolve among a diverse number of inhabitants in and around the park (Bryan Citation2015). The study follows three procedures. First, a combination of local accounts and fieldwork observations of the case area. Second, interviews with tourists and local stakeholders on processes of engagement and disengagement with conservation, restoration, and rewilding processes. Third, collaborative mapping with local stakeholders and citizens and their imaginaries of local nature – identity, preferences, and practise. We understand the methods to be partly supportive when each one reveals similar or controversial knowledge (Blondet et al. Citation2017; Bryan Citation2015; Chambers et al. Citation2022; Salvatore, Chiodo, and Fantini Citation2018).

3.1. Case area

The case area can be considered an extreme case in Flyvbjerg’s terminology (Flyvbjerg Citation2010) with an extraordinarily high number of conflicts over changes in nature use. In the late 1990s, the NPÅ area gained growing political attention to nature and culture restoration projects (Ministry of the Environment Citation2001). Reports by consultancies (e.g. COWI Citation2006) and national nature conservation agencies (Ministry of the Environment Citation2006) pinpointed the need for restoring the area, not least to preserve some of the best archaeological artefacts from the Mesolithic Stone Age in northern Europe (Aaby and Noe-Nygaard Citation2020; Lundhede, Hasler, and Bille Citation2013). Also, the Danish Forest and Nature Agency formed initiatives from 1999 to 2006 on wetland restoration simultaneously with initiatives transforming the area into a national park (Ministry of the Environment Citation2006). However, expert- and authority-driven nature preservation and rewilding for more wetlands conflicted with the parallel local process of becoming a national park. Many landowners found themselves marginalized and under-represented in the planning process (Ministry of the Environment Citation2006). As these landowners had major concerns with the nature restoration project and the nature park initiative, they formed a lobbying group, ‘the Association for the Conservation of Nature in Eastern Åmose’, that mobilized protests among national and local politicians (Holm, Cold-Ravnkilde, and Grindsted Citation2020). Both the wetland restoration and national park project fell apart. The 180 million DKK (€24.1 million) Finance Act (2006) was withdrawn a few days before enactment as the Government could not obtain a majority in Parliament. Irrespectively, processes of restoring peatland and wetlands in the bog failed, leaving local actors with a generalized asymmetry, mistrust, anxiety and division regarding both the conservation project and the national park initiative (Holm, Cold-Ravnkilde, and Grindsted Citation2020). The steering group of the initiative for creating a national park then chose to abandon their efforts in exchange for establishing a nature park on less conflictual ground as a voluntary private NGO initiative, receiving less attention from the public and national authorities. In 2014 they succeeded; the Åmose area became the first nature park in Denmark. These errors caused wetland restoration projects in and around NPÅ to be a taboo subject for many years to come, drawing an inflamed and divided line locally (Byrnak-Storm, Holm, and Grindsted Citation2022), including the aims of mixing nature park development with accessibility to land, trails, tourism, and nature restoration interests. Many landowners still back off in despair and mistrust when external units want to develop change processes, due to their experience with lack of influence, poor information, and little transparency during initial nature preservation and pilot park periods (Byrnak-Storm, Holm, and Grindsted Citation2022).

3.2. Fieldwork observations

Fieldwork can be considered a plethora of specific methods, each contributing to understanding an area (Grindsted, Møller, and Nielsen Citation2013). Fieldwork observations consisted of several visits, historical maps and desk research to obtain a detailed overview and history of the area. Such observations further consisted of field notes from a landowner trip in June 2022 with 35 landowners from the area. The landowners were exposed to different sites and topics, including tourism development, nature protection, accessibility and restrictions. Researchers undertook both participant observation and small interviews on each site on the landowners’ attitudes towards the area. Participant observation includes discussions among landowners and their stated opinions on the different sites. Field notes consist of reflective notes, for example, when a landowner talks about ‘wetland transformation’ with a fellow landowner for the first time.

3.3. Interview

The material consist of 15 in-depth qualitative interviews with local stakeholders, 6 focus group interviews (2019–2022), as well as short interviews with 79 tourists. Focus group interviews were held with specific interest groups such as horse riders. The semi-structured interviews were audio recorded. All respondents have given their consent and allowed us to publish quotations taken from the interviews.

The 15 respondents and 6 focus group interviews included actors with a direct relation to the nature park (). Based on a primary mapping of public, semi-public, and voluntary organizations, interviewees were selected on the basis of inputs from the nature park organization, business directories, and internet searches. The initial mapping was followed by a snowball selection of additional actors. However, because of the interviewee selection method, participants may be skewed towards the more ‘visible’ and progressive tourism and potentially tourism-interested actors. The interviews offered insights into how processes both materialize in the area and are constituted by the narratives through which the stakeholders engage in developing the nature park. Interview themes included the perceptions of NPÅ, its nature and landscapes, the development potential, respondents’ development focus and hopes for their area, attractions visited, their experiences, and the potential for and barriers to reaching their goals, including those imposed by the strategies of other actors (Cold-Ravnkilde, Holm, and Grindsted Citation2021; Holm, Cold-Ravnkilde, and Grindsted Citation2020). The questions opened up a discussion on what things the interviewees regarded as needing to be sustained (e.g. nature or socio-cultural conditions), what needed to be developed (e.g. re-naturalization, denaturalization), and whether and how the actors saw their own interests being realized in this context. The analytical approach was hermeneutical and abductive, involving a recursive process between data collection, data analysis, and the literature. Interviews, the landowner trip, and collaborative mapping were subject to thematic analysis (Silverman Citation2006). Using this process, we applied implicit and explicit meaning condensation and meaning categorization to the data, thereby identifying geo-positionalities of the nature park development materialized in six conflicting landscape imaginaries.

Table 1. Interviewees in the case study (Recording number and reference I1–I15).

3.4. Collaborative mapping

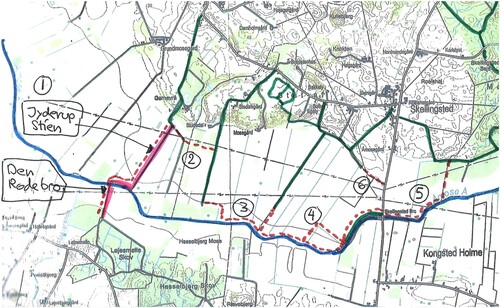

A total of 186 citizens participated in 11 workshops (2019–2022) at the location of the nature park secretariat, and at public nature park events. At such workshops, citizens mapped their own or others’ local stories from places in the nature park. The workshops were semi-structured and themes were developed collaboratively. Collaborative mapping methods covered different angles of events and experiences, ecological change, including struggles over resources, (in)justice, local meaning, and narratives. The respondents were asked to place figures on one or more of the six detailed maps of the nature park developed for the purpose, and write their experiences with specific places. Advocators of collaborative mapping suggest that such methods empower local communities and support bottom-up processes (Bryan Citation2015; Salvatore, Chiodo, and Fantini Citation2018). This way, the fieldwork interviews and collaborative mapping were not framed beforehand by established scientific concepts and approaches but sought to explore stakeholders’ and citizens’ perspectives and approaches that could be translated into conflicting landscape associations (Map 2).

Map 2. Collaborative mapping and collection of landscape representations. The map shows stories identified by locals including proposals for landscape modifications, such as new trails. Point 1 marks an existing public trail, point 2 a possible trail with stories of peat digging, and point 6 marks the former electricity masts installed by workers in the 1950s that became visible signs of progress locally.

4. Results

This section presents the landscape configurations of the nature park. It suggests how rurality, accessibility, usability, utilization, commodification, aesthetics, and different nature types are configured in the same physical landscape of NPÅ. We suggest that there are at least six conflicting nature park landscape configurations that can be identified by the ways in which they produce different types of nature. Each differs in terms of which landscape characteristics need to be developed and which need to be sustained, all of them claiming to care about nature, biodiversity, and nature protection. Thus, nature-based tourism initiatives may often hold certain landscape configurations and represent specific geo-positionalities that may mobilize or block incentives for rewilding, preserving, restoring, or remanufacturing natural landscapes in a nature park context.

4.1. Renaturing pristine natures – remoteness and wilderness as an attraction

The nature park as a remote destination holds connotations of re-naturalization to environmental qualities and aesthetics in which the remoteness becomes a particular quality. The nature park landscape celebrates what is remote, untouched, and unspoiled, whereby a rurality recentres around the landscape’s distinctive qualities. Citizens devoted to geo-positionalities celebrating the remoteness of the nature park point to quietness, dark sky, and slow living as an active anchor point, thus the landscape becomes associated with lifestyles that are contrasted with busy city life. Similarly, property owners, hunters and special segments of tourism actors celebrate and preserve environmental remoteness and inaccessibility as a distinctive local quality.

The quietness we have, a walk with the dog while listening to the birds in the spring, the beauty of riding in the sunset, watching the rabbits playing, seeing the owls and cranes … (pause) … living here for some time you become one with nature, you blend in. We bought our house in Åmosen [NPÅ, ed.], we first moved here because of the wild nature – the fact that you can ride in the wilderness we have. (Focus group interview)

If you are in the middle of the Store Åmose [the largest bog – ed.], you are far away from everything … It is one of the most remote areas that you can reach, and I almost get the feeling of being in a tundra [Scandinavian pristine bog landscape – ed.] … And this I believe is something we can also sell … Once we have made a little out of the tourism infrastructure and made it visible, I believe local tourist actors will see the business potential, and then more people would say we can create unique accommodation and nature experiences here. There are some areas we should have the courage to develop and some areas we should have the courage to fully protect. Because that is also a selling point that makes us unique. (Interview 4)

The pristine nature and remoteness, however, are not only celebrated by citizens living in the nature park, but also by tourists and those who advocate nature-based tourism development. For those actors, the remote landscape shapes various kinds of associated natures, including the ‘tundra’, the ‘bog’ and ‘marshland’ (Interview 27). The latter two, which exist in the nature park, hold aspirations to Nordic silence and lead to a certain agenda on what needs to be preserved and what restored. Thus, the bogs’ remoteness and unspoiled character (although heavily drained) should be further developed, such that the area becomes both re-naturalized and naturalized, e.g. with ‘wildlife’ and with as little visible remains of modern society as possible. It thereby establishes city-nature relations in which wild nature should be further developed, and human cultivations removed, to recover a feeling of untouched landscapes and celebration of wildlife (Interview 19).

Nevertheless, these aspirations seem to be constructions bounded in sustainability as ‘wilderness and pristine nature imaginaries’ that should be developed to restore nature by commodifying it as a tourism resource, and they are reinforced by actors with interests in developing tourism. For example, in line with the above, the nature park advertises itself as ‘the last wilderness on Zealand’ on the nature park’s website. Objectively, however, the nature park is exclusively composed of cultural/production landscapes (agriculture and forestry) crisscrossed by old and modern built environments, and visible as well as subterranean infrastructures. The main bog, for example (described as being in the tundra in the quote above), was drained and turned into farmland in the 1930s–1960s.

4.2. Recreational landscapes and naturalized consumerism

Those who advocate recreational landscape configurations associate rurality with landscape sceneries, and see the landscape as a site for nature-based activities, farm-based experiences, holidays, recreation, and sport. These actors find the development of recreational attractions and infrastructure a catalyst for nature-based consumerism of various sorts. The recreational landscape should further develop access to nature in the park, attractions, holiday activities, trails, and infrastructures that better facilitate nature-based tourism activities.

Advocates of this view include micro-tourism actors who draw up certain agendas that re-naturalize land resources towards political ecologies of accessibility by the ways in which they instrumentalize nature for tourism demands. As natural resources are inaccessible for many tourism operators, one farm holiday centre planted a small forest to provide better access to nature experiences for its visitors:

I had to plant a forest … My farm holiday centre is on intensive agricultural land with many large farms, but many property owners do not like tourists. One nearby property owner in particular found it inappropriate that my visitors occasionally entered his woods. Eventually I planted my own forest on six hectares. We made a horse trail, we have a horse drawn carriage to make little tours into the wood, and occasionally I pull the carriage with my tractor. I built a bird tower so that tourists can climb and see the landscape, the lake, the birds. That is popular, although many visitors do not know the name of the birds they watch. Sometimes we do have experts, but generally … We planted 25 different trees, most tourists are unable to distinguish between them, which is why we strive to have an expert from the nature park to guide visitors. (Interview 11)

Transforming the landscape from an agricultural resource into a resource that better accommodates experiences for tourists also implies criticism of the affects, scenery, and effects of industrial or monocultural farmlands. This perspective facilitates the primarily external interests of tourists (from the capital and major cities) and their consumer-based activities, potentially in conflict with local nature (com)modifications.

4.3. Culture-nature romanticism and pre-agroindustrial aesthetics – celebrating the hidden remains

The few actors advocating romanticism of the landscape connote specialized ‘objects of knowing’ that invite experiences arising from the history of the landscape. This refers both to the visible remains of small villages and dilapidated towns, in which the distinctiveness, materiality, and culture of the locale support the nature-based experience, and to the invisible cultural and historical remains in the landscape. Illustrating the latter, inhabitants of the nature park highlight the uniqueness of the archeological remains beneath the peat.

Some archeological remains are visible in the landscape, but most are not. The cultural history is not visible. Some of the world’s best preservation conditions for Mesolithic Stone Age remains are in the peat, you know. To experience findings from there, you need to visit the National Museum of Denmark. But it is far more interesting to visit the bog. The cultural remains make us unique, but only a handful know about the fantastic cultural remains that we have. Here you can imagine the Mesolithic Stone Age, how it may have looked, but also tell visitors that we stand in the middle of the best archeological remains in northern Europe from that period … This is the site that labels the archeological periods Maglemosetid and Kongemosetid, you know. I love to go out to the former peat industry that Carlsberg, among others, started … They found a whole intact settlement out there. There is so much you cannot see. The peat workers had pubs, schools and brothels out there, a whole industry. (Interview 16)

For advocators of preserving cultural remains, geo-positionalities of unsustainability reside in the immense drainage for agricultural production during the past century, and sustainability lies in restoring the previous wetlands for preserving cultural interests, biodiversity restoration (where relevant to this aim), and, to a lesser extent, climate mitigation. Visible remains, the local history, its previous production facilities (peat cutting, mills, etc.) uphold cultural politics of environmental romanticism celebrating pre-agricultural landscapes. This type of culture-environmental romanticism also relates to the connotations of the patchwork landscape – a mosaic of multilayered and multidimensional use from the many cultural time periods, creating a scenery of never-ending oscillation.

With the growing interest in nature tourism development, the landscape perspective gains momentum for commodification, according to which sustainability resides in preserving the history of the land and its artefacts for generations to come. Nevertheless, while the nature park’s visitor centre has an exhibition of (mainly) copies of the most important discovered remains from the Mesolithic Stone Age and the Viking Age, the heritage remains invisible, hidden, and uncommunicated to visitors.

4.4. Productive natures: agricultural and industrial modifications – denaturalizing the landscape

Deeply rooted in agricultural production and the history of the agro-industrial supply and growth regime, the nature park as an agricultural landscape resort finds resonance in local peasants’ and farmers’ habits. Over two generations or more, they and their families have succeeded in taming the bog, the forest and the wilderness to earn a living – and turn the wilderness into productive land. It is reflected in the sceneries of open crop fields, manor houses, estate landscapes, hunting tracks and farmland production of primary products. It is primarily large-scale property owners and farmers who uphold the preservation of agricultural farmland, but local citizens also describe the beauty of agricultural land and its aesthetics. According to this perspective, the history of taming the land is part of the production of wealth in the area. Such geo-positionalities find nature-based tourism represents a disturbance to farming, hunting and traditional rural landscapes, and other ‘productions’ challenge not only the ‘primary production’ but also the beauty and local identities built up for generations. Former industrial uses of the landscape (for peat, beet, brick, gravel, clay) have been replaced by progress and development of more efficient landscape management techniques together with farming. Thus, the use of lakes for processing water, for example, has become a contingent optimization issue. Both industrial and farming interests are rooted in ‘water and land use optimization’, requiring planning for the equilibrium of water balance, but they uphold conflicting strands and have diverse impacts on landscape qualities.

By way of illustration, as rainfall has increased during winter and is expected to further increase with local experiences of retaining wetland domestication challenges (including more frequent drought events that will occur in the summer), landowners have requested compensation for installing further drainage to avoid increased winter crop loss. Farmers wish to have a low water level during summer in order to drive heavy machinery. By contrast, industry demands process water from lake Tissø and the Åmose water system. With increasing summer drought periods, industrial parties have formulated interests in raising the water level for better security of supply (Interview 2). Thus, industrial needs for process water during summer drought periods further counterpose the interest of farmers, and industry may instrumentalize nature by restoring the wetland in the future. While industry and farmers display different landscape ‘efficiency’ interests, they both aim at capitalizing by optimizing land management.

While a few of the larger landowners see the potential for developing tourism offers as an additional commodification strategy, most landowners find it unattractive and a potential hindrance to their core business. Thus, their land is closed to tourism development initiatives and to the small-scale nature tourism entrepreneurs and other actors with tourism and leisure interests. In this landscape perception, the role of nature is determined by the possibilities of extracting economic operand value from its resources, and in this game, forestry, farming, and hunting rule while leisure and tourism interests (other than hunting) are not favoured.

The hunters, they pay, right! Then we talk business. The hunters are the only nature users that really pay. And they pay a lot! And of course, if there is an increased use of the land, people walking or mountain biking, or horse riders who do not pay a lot or nothing at all, then it takes from those that pay. Then they tell me: we don’t want to pay as much because there are always people walking around. And then I lose business. It is amazingly simple! And that is why I am sometimes against establishing new things. If money is involved, then everything is possible. (Interview 9)

4.5. Restoration of nature – the landscape as inherent nature

Proponents of this perspective, which is deeply rooted in associations with getting back to nature, strongly associate the land with their ‘home’. Here the rural landscape is perceived and valued as a refuge from the urban, its noise, and alienation from nature-based experiences. The rural environment has the positive connotations of grounding, health and wellbeing, purity, inherited sensory properties and nature-based living and resilience. The landscape as inherent manifest nature breaks away from what can be considered harmful or destructive in society; an imagined reality about the peaceful, idyllic, and unspoiled land where the dwellers re-connect and restore their relationship with nature. Similarly, these geo-positionalities of naturalization as an inherent process consider a physical landscape with special characteristics, traditions, and culture that values a set of qualities and assumptions much negated as irrelevant to urban life. Thus, citizens affiliated to the landscape as inherent nature explain their active dropping out of the increasing hypermodern acceleration in modern society as an active choice to recentre life politics. The land as home thus reconnects with nature, and those living there seek to distance themselves from any land changes and activity that could disturb the quietness of rural life and be associated with degrowth due to the ways in which the residents aim to protect wild animal life and habitats.

Our area is one of the few on the Island of Zealand where you can walk in a remote environment, where you can view the stars, and enjoy the feeling of being fully alone. At some point, the municipality planned streetlights in our village, but it would destroy the beauty of the place. We did not want it. (Participatory mapping)

The woods, trees, lakes, wildlife, and landscape may offer various life-centred interpretations for locals and visitors that host courses, therapies and events involving meditation, pantheistic celebrations, contemplative therapies, glamping, and other properties for communities of nature-based spiritualized people and the like. The more rewilding and nature restoration, the better. The other types of landscape preferences mentioned, except for the remoteness and wilderness landscape, threaten this refugium type of landscape interpretation. What is unsustainable resides in the city and society, whereas sustainable land transition must reconnect humans with nature.

4.6. Preservation of landscapes – the landscape as a reserve

Finally, the landscape and the nature park as a reserve come into play. This unmasks preservation versus restoration efforts with multiple and conflicting views over tourists´ access to and use of natural resources. Deeply rooted in cultural and environmental conservativism, existing landscapes need to be preserved and the idea that the landscape and its natural biotopes, culture, and values need to be kept safe from new intervention is prevalent. Respondents who associate themselves with such geo-positionalities are as diverse as property owners, small-scale farmers, NGOs and nature protectionists, biologists, and hunters. The diverse groups find that they preserve nature by hindering people’s access to land, from the perspective of biologists by having biotopes with no human intervention and from that of other locals by avoiding disturbance to animal life, etc.

We have many unique flowers and rare orchids, and birds in Åmosen. Once I had tourists in my garden, and they saw nothing and simply trod on rare plants. We protect the flowers and the unique landscape best by keeping the tourists away. (Interview 13)

By way of example, locals have reported that otters have reappeared in the lower part of the Åmose water system. Otters are rare animals in Denmark. Simultaneously, NPÅ aimed to develop recreational infrastructure and public access to parts of the water system for canoeing and kayaking. However, landowners and nature conservation actors were sceptical over the proposal and found themselves being protectors of the otter (and their land) and at the same time restricting tourist and visitor access to private property along the stream.

The preservation of land is a concept held most dominantly by environmental conservativism, in which the existing manipulated natures should be kept as they are, but restricted from access by others, and should be neither re-naturalized nor naturalized according to the will of external interests or authorities. It is the locals who preserve the landscape and its biodiversity and act best in the interests of nature.

5. Discussion

This study identified six conflicting landscape configurations in NPÅ, each of which is devoted to different geo-positionalities. Geo-positionalities, we argue, appear both as conflicting landscape positionalities over the same area and in relation to nature-based tourism as an incentive for remanufacturing nature.

Landscape configurations are dynamic and interchangeable over time, and we do not claim to cover the full spectrum of landscape views in the case area nor all land use controversies related to nature park developments. Rather, we argue that the conflicting landscape associations identified hold asymmetrical geo-positionalities that create stabilized yet dynamic ‘landscape lock-ins’. Inasmuch as local accounts differ from one another, each landscape configuration is promoted to exclude others in their pure form. Mutually defined as conflicting with other landscape accounts, they are dynamic and yet they stabilize, and if dominant may hinder more sustainable land transformations in terms of meeting IPCC and other external agendas (Hermoso et al. Citation2022; IPCC Citation2014; Krauss, Zhu, and Stagg Citation2021). The hegemonic landscape account is not in itself an anticipation of a transition into rewilding or becoming a wetland.

The root causes of different rural and policy-driven development strategies force nature tourism entrepreneurs, farmers, property owners and others to navigate between different conflicting landscape associations and changing social natures (Castree and Braun Citation2006; Mace Citation2014). This suggests how the different actors manoeuver and position themselves within different tourism demands, remanufacturing nature in accordance with consumed and commodified natures (Katz Citation1998), regardless of possible positive or negative environmental impacts (Büscher and Fletcher Citation2017).

Yet the multiscalar agendas and dynamics from outside – climate change and drivers for turning the area into a wetland (IPCC Citation2014; Krauss, Zhu, and Stagg Citation2021), biodiversity (Hermoso et al. Citation2022), tourism as a rural development strategy (Bærenholdt and Grindsted Citation2021), cultural heritage of national or tourism interests (Iannucci, Martellozzo, and Randelli Citation2022), and industrial and agricultural demands (Castree and Braun Citation2006; Van der Ploeg Citation2018) – all represent combinations within which they inevitably instrumentalize and provoke various landscape images. Aligned with the findings of Hoogendoorn et al. (Citation2019), this study shows that new tourism commodifications of nature operate in niches that, even when rewilding nature to better suit visitors’ tourism landscape expectations, legitimate the rise of counterpositions among locals. External forces, from tourism organizations, external companies, policy-driven nature restoration (Farstad et al. Citation2022), and scientists (Grindsted Citation2018), however profitable they are declared to be to locals, contradict local tourism development and expose the ambivalences of the locals living with tourism (Bærenholdt, Fuglsang, and Sundbo Citation2021; Büscher and Fletcher Citation2017; Huijbens Citation2012).

The different landscape accounts pinpoint that nature-based experiences may mobilize into new ‘landscapes’ and ‘natures’ whereby tourism instrumentalizes ‘nature’ into a set of different conflicts over various land uses and views on environmental sustainability agendas (Sørensen and Grindsted Citation2021). Commoditization of nature as a leisure and tourism resource also results in mobilization of new landscape imaginaries in an increasingly complex ‘landscape’ of conflicting local perceptions and preferences, we argue. Yet these accounts neither suppress nor devalue the variegated conflicting landscape configurations. Rather, the different accounts point towards instrumentalizations from tourism that accommodate rewilding, preserving, restoring, conserving, or remanufacturing natural landscapes when it comes to landscape development accounts in a Danish nature park context.

Although wilderness attractions and cultural remains mark restoration and preservation interests and associated natures (wetland and wilderness, respectively) (Katz Citation1998), the restored nature park agendas invite questions such as: preserving for whom and in whose interest? This marks local conflicts over coexisting landscapes, agricultural farmland versus minor biotopes or visitor sites, as re-nationalization of different productions (and associated co-existing natures). By way of illustration, a few minor tourism actors have an entrepreneurial approach that turns farmland into landscapes that better accommodate tourism demands; for instance, by converting farmland into forest and biotope reserves (Lykkebjerg, Kattrup, Åmosen naturcamp, and Tyrsgaard being examples).

Advocates of the growth of tourism sometimes recognize nature-based tourism as a driver for environmental improvement (Hoogendoorn et al. Citation2019), thus advocating for themselves as more sustainable land users, as tourists are said to demand landscapes of high recreational and natural value (Bostedt and Mattsson Citation1995; Genovese et al. Citation2017). Others, however, contrast such standpoints locally, as tourist demand conflicts with other value systems, practices, local community development strategies, farmland, nature conservation organizations or property owners (Kaltenborn, Haaland, and Sandell Citation2001; Matilainen and Lähdesmäki Citation2014).

The six conflicting landscape configurations identified are each counterproductive to the others, and all claim to uphold sustainable land management components that explain what needs to be sustained and what needs to be developed. Yet these are sometimes so indifferent and controversial to one another (or external to locals) as to hinder a common route for sustainable land transformation, if wetland transformations in accordance with the IPCC are to follow.

For future interventions on nature tourism and the like to avoid meeting lock-ins by locals, we suggest that the deliberate adoption of conflicting landscape visions be articulated (mapped, photographed, drawn) among local stakeholders and citizens, as this is where we understand many conflicting values and interests really do crystallize in a form of common ground with tacit values that will not be mentioned in normal participatory efforts.

We invite studies that critically scrutinize conflicting landscape configurations in other nature/national parks to examine both the extent to which they prove overlapping and identifiable with other contexts and where they lock in local accounts for sustainable landscape transformations, as well as where they mediate new transitional landscape formations. Similarly, for case studies exploring where conflicting landscape associations may blend together over time and mediate transition, we propose local stakeholder analysis that maps hidden conflicting landscape configurations as a way forward. By doing so we may also avoid misinterpreting the use of common value dominator concepts (‘wild’, ‘beauty’, ‘sustainable’) that may confuse us, in order to reach a consensus when meeting local positions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all that have been interviewed and/or supported this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Until the middle of the nineteenth century, bogs, peat, and wetlands occupied 20%–25% of the country. Today such areas cover less than 1%–3% (Ministry of the Environment Citation2022). Moreover, the area has more than 8,000 ha of lowlands and 2,802 ha of carbon-rich soil (>12% carbon), the third largest in Denmark. While no accurate emission estimates exist, COWI (Citation2006) found that Store Åmose emits 23,147 ton CO2e/year in a 1,413 ha site with carbon-rich soils and 18,702 ton CO2e/year in another 1,181 ha site. Emissions estimates for the entire drained wetland are rather uncertain, but could be 50–150,000 ton CO2e/year, as COWI (Citation2006) estimate that one ha emits 15–16 ton CO2e/year. This would be approx. 1/10 of the emissions from Copenhagen (1.1 Mt/ CO2e/year). Altogether Denmark has 300,000 ha of carbon-rich soils (>6% carbon) that emit 77.5 Mt CO2e/year (Greve et al. Citation2020; Gyldenkærne and Greve Citation2015).

References

- Aaby, B., and N. Noe-Nygaard. 2020. “Åmosens historie fra fortid til nutid.” Copenhagen University, Denmark. (In Danish). https://naturstyrelsen.dk/media/nst/Attachments/%C3%85mosenshistoriefrafortidtilnutid.pdf.

- Andersen, H. T., A. Egsgaard-Pedersen, H. K. Hansen, E. S. Lange, and H. Nørgaard. 2022. “Counter-Urban Activity Out of Copenhagen: Who, Where and Why?” Sustainability 14 (11): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116516.

- Arler, F., M. S. Jørgensen, E. M. Sørensen, and E. Sønderriis. 2017. “Prioritering af Danmarks areal i fremtiden: Afsluttende rapport fra projektet.” Fonden Teknologirådet. (In Danish).

- Benediktsson, K. 2016. “‘Scenophobia’, Geography and the Aesthetic Politics of Landscape.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 89 (3): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2007.00249.x.

- Blondet, M., J. de Koning, L. Borrass, F. Ferranti, M. Geitzenauer, G. Weiss, E. Turnhout, and G. Winkel. 2017. “Participation in the Implementation of Natura 2000: A Comparative Study of Six EU Member States.” Land Use Policy 66: 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.04.004.

- Bostedt, G., and L. Mattsson. 1995. “The Value of Forests for Tourism in Sweden.” Annals of Tourism Research 22 (3): 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00007-S.

- Bostedt, G., and L. Mattsson. 2006. “A Note on Benefits and Costs of Adjusting Forestry to Meet Recreational Demands.” Journal of Forest Economics 12 (1): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfe.2005.12.002.

- Bærenholdt, J. O., L. Fuglsang, and L. Sundbo. 2021. “A Coalition for ‘Small Tourism’ in a Marginal Place: Configuring a Geo-Social Position.” Journal of Rural Studies 87: 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.010.

- Bærenholdt, J. O., and T. S. Grindsted. 2021. “Mobilising for the Diffuse Market Town Hotel: A Touristic Place Management Project to Reuse Empty Shops.” In Mobilities and Place Management, edited by C. Lassen, L. H. Laursen, and G. R. Larsen. Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060903580649

- Bryan, J. 2015. “Participatory Mapping.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by T. A. Perreault, G. Bridge, and J. P. McCarthy. London: Routledge.

- Buckley, R. 2012. “Sustainable Tourism: Research and Reality.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2): 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.003.

- Büscher, B., and R. Fletcher. 2017. “Destructive Creation: Capital Accumulation and the Structural Violence of Tourism.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (5): 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1159214.

- Byrnak-Storm, N., J. Holm, and T. S. Grindsted. 2022. Borgerinddragelse i udvikling og forvaltning af større naturområder – evaluering af resultater. Roskilde University. (in Danish). https://forskning.ruc.dk/da/publications/borgerinddragelse-i-udvikling-og-forvaltning-af-st%C3%B8rre-naturomr%C3%A5d.

- Castree, N. 2001. “Social Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics.” In Social Nature – Theory, Practice and Politics, edited by N. Castree and B. Braun. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Castree, N. 2013. Making Sense of Nature. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203503461

- Castree, N. 2014. “The Anthropocene and Geography I: The Back Story.” Geography Compass 8 (7): 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12141

- Castree, N., and B. Braun. 2006. “Constructing Rural Natures.” In Handbook of Rural Studies, edited by P. Cloke, T. Marsden, and P. H. Mooney. London: SAGE. http://www.uk.sagepub.com/refbooks/Book211514.

- Chambers, J. M., C. Wyborn, N. L. Klenke, M. Ryan, A. Serban, N. J. Bennett, R. Brennan, et al. 2022. “Co-productive Agility and Four Collaborative Pathways to Sustainability Transformations.” Global Environmental Change 72: 102422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102422

- Cold-Ravnkilde, S., J. Holm, and T. S. Grindsted. 2021. Gæster på Nye Veje: Et Idékatalog til Fremtidens Naturpark. Roskilde University (In Danish).

- CONCITO. 2023. “Danmarks Arealer – Danmarks Fremtid.” Copenhagen. https://concito.dk/nyheder/rapport-danmarks-arealer-danmarks-fremtid (In Danish).

- COWI. 2006. “Teknisk Sammenfatning af Skitseprojekt for østlige Store Åmose.” Skov- og Naturstyrelsen og Kulturarvsstyrelsen. (In Danish).

- Danish Government. 2023. “Udtagning af Klima og Lavbundsjorde.” Minestry of Environment. https://mst.dk/natur-vand/vandmiljoe/tilskud-til-vand-og-klimaprojekter/udtagning-af-lavbundsjorder/ (in Danish).

- Dicken, P., and N. Thrift. 1992. “The Organization of Production and the Production of Organization: Why Business Enterprises Matter in the Study of Geographical Industrialization.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 17 (3): 279–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/622880.

- Ecolabel Index. 2023. https://www.ecolabelindex.com/ecolabels/?st=category,tourism.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment. 2021. “EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into our Lives.” https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779048.

- Farstad, F. M., E. A. T. Hermansen, B. van Oort, A. Grønlund, K. Mittenzwei, K. Brudevoll, and B. S. Grasbekk. 2022. “Explaining Radical Policy Change: Norwegian Climate Policy and the Ban on Cultivating Peatlands.” Global Environmental Change 74: 102517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102517.

- Fletcher, R., I. M. Mas, A. Blanco-Romero, and M. Blázquez-Salom. 2019. “Tourism and Degrowth: An Emerging Agenda for Research and Praxis.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27: 1745–1763. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1679822.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2010. “Fem Misforståelser om Casestudiet.” In Kvalitative metoder, edited by S. Brinkmann and L. Tanggaard, 463–487. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag. (in Danish).

- Fredman, P., and L. Tyrväinen. 2010. “Frontiers in Nature-Based Tourism.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 10 (3): 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.502365.

- Genovese, D., F. Culasso, E. Giacosa, and L. M. Battaglini. 2017. “Can Livestock Farming and Tourism Coexist in Mountain Regions? A New Business Model for Sustainability.” Sustainability 9 (2021): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112021.

- Greve, M. H., M. B. Greve, Y. Peng, B. F. Pedersen, A. B. Møller, P. E. Lærke, L. Elsgaard, et al. 2020. “Vidensyntese om kulstofrig lavbundsjord”. National Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug, Aarhus Universitet. (In Danish). https://pure.au.dk/portal/files/214394346/Vidensyntese_kulstofrig_lavbundsjord_3003_2021_rev.pdf.

- Grindsted, T. S. 2018. “Geoscience and Sustainability: In between Keywords and Buzzwords.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 91: 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.029.

- Grindsted, T. S., L. M. Møller, and T. T. Nielsen. 2013. “‘One Just Better Understands … .When Standing Out There’: Fieldwork as a Learning Methodology in University Education of Danish Geographers.” Review of International Geographical Education Online 3 (1): 8–25.

- Gustafsson, S., B. Hermelin, and L. Smas. 2019. “Integrating Environmental Sustainability into Strategic Spatial Planning: The Importance of Management.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (8): 1321–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1495620.

- Gyldenkærne, S., and M. Greve. 2015. “Teknisk Rapport – For bestemmelse af drivhusgasudledning ved udtagning/ekstensivering af landbrugsjorder på kulstofholdige lavbundsjorde.” Rapport Nr. 56, Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi – DCE. Aarhus University. (In Danish).

- Haisch, T. 2019. “Working Towards Resilience: Collective Agency in a Tourism Destination in the Swiss Alps.” In Resilient Destinations and Tourism: Governance Strategies in the Transition Towards Sustainability in Tourism, edited by J. M. Saarinen and A. Gill. London: Routledge.

- Hermoso, V., S. B. Carvalho, S. Giakoumi, D. Goldsborough, S. Katsanevakis, S. Lenontiou, V. Markantonatou, B. Rumes, I. N. Vogiatzakis, and K. L. Yates. 2022. “The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Opportunities and Challenges on the Path Towards Biodiversity Recovery.” Environmental Science & Policy 127: 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.10.028.

- Holm, J. 2017. Definitionsramme for bynær økoturisme. Roskilde University. (in Danish). https://forskning.ruc.dk/da/publications/definitionsramme-for-b%C3%A6redygtig-byn%C3%A6r-%C3%B8koturisme.

- Holm, J., S. Cold-Ravnkilde, and T. S. Grindsted. 2020. Borgernes Stemme: Udfordringer og ønsker til fremtidens naturpark. Roskilde University. (In Danish). https://rucforsk.ruc.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/68112302/Borgernes_stemme_rettet_v.4_lmfh.pdf.

- Hoogendoorn, G., D. Meintjes, C. Kelso, and J. Fitchett. 2019. “Tourism as an Incentive for Rewilding: The Conversion from Cattle to Game Farms in Limpopo Province, South Africa.” Journal of Ecotourism 18 (4): 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1502297.

- Huijbens, E. H. 2012. “Sustaining a Village’s Social Fabric?” Sociologia Ruralis 52 (3): 332–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00565.x.

- Iannucci, G., F. Martellozzo, and F. Randelli. 2022. “Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: A Dynamic Model in Between Tourism Exploitation and Landscape Decline.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 32: 991–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-022-00785-4.

- IPCC. 2014. 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands, edited by T. Hiraishi, T. Krug, K. Tanabe, N. Srivastava, J. Baasansuren, M. Fukuda, and T. G. Troxler. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#FullReport.

- Jasanoff, S., and S. H. Kim. 2009. “Containing the Atom: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Nuclear Power in the United States and South Korea.” Minerva 47: 119–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4.

- Jasanoff, S., and S.-H. Kim. 2013. “Sociotechnical Imaginaries and National Energy Policies.” Science as Culture 22 (2): 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2013.786990.

- Jasanoff, S., and S.-H. Kim. 2015. Dreamscapes of Modernity Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago: The Chicago University Press.

- Kaae, B. C., J. Holm, O. H. Caspersen, and N. M. Gulsrud. 2019. “Nature Park Amager – Examining the Transition from Urban Wasteland to a Rewilded Ecotourism Destination.” Journal of Ecotourism 18 (4): 348–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1601729.

- Kaltenborn, P., H. Haaland, and K. Sandell. 2001. “The Public Right of Access: Some Challenges to Sustainable Tourism Development in Scandinavia.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 9 (5): 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580108667412.

- Katz, C. 1998. “Whose Nature, Whose Culture? Private Production of Space and the Preservation of Nature.” In Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millennium, edited by N. Castree and B. Braun. London: Routledge.

- Kirsch, S., and D. Mitchell. 2004. “The Nature of Things: Dead Labor, Nonhuman Actors, and the Persistence of Marxism.” Antipode 36 (4): 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2004.00443.x.

- Koninx, F. 2019. “Ecotourism and Rewilding: The Case of Swedish Lapland.” Journal of Ecotourism 18 (4): 332–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1538227.

- Krauss, K. W., Z. Zhu, and C. L. Stagg. 2021. “Managing Wetlands to Improve Carbon Sequestration.” Eos 102. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO215004.

- Lordkipanidze, M., H. Brezet, and M. Backman. 2005. “The Entrepreneurship Factor in Sustainable Tourism Development.” Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (8): 787–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.02.043.

- Lundberg, C., P. Fredman, and S. Wall-Reinius. 2014. “Going for the Green? The Role of Money among Nature-Based Tourism Entrepreneurs.” Current Issues in Tourism 17 (4): 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.746292.

- Lundhede, T., B. Hasler, and T. Bille. 2013. “Exploring Preferences and Non-Use Values for Hidden Archaeological Artefacts: A Case from Denmark.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 19 (4): 501–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2011.652624.

- Mace, G. M. 2014. “Whose Conservation?” Science 345 (6204): 1558–1560. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254704.

- Margaryan, L. 2012. “‘Rewilding’ and Tourism: Analysis of an Optimistic Discourse on Nature Conservation.” Master Thesis, Wageningen University and Research Center.

- Margaryan, L., and P. Fredman. 2017. “Bridging Outdoor Recreation and Nature-Based Tourism in a Commercial Context: Insights from the Swedish Service Providers.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 17: 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.01.003.

- Matilainen, A., and M. Lähdesmäki. 2014. “Nature-Based Tourism in Private Forests: Stakeholder Management Balancing the Interests of Entrepreneurs and Forest Owners?” Journal of Rural Studies 35: 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.04.007.

- Meged, J. W., and J. Holm. 2022. “Urban Ecotourism and Regime Altering in Denmark.” In Handbook of Niche Tourism, edited by M. Novelli, J. M. Cheer, C. Dolezal, A. Jones, and C. Milano. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2001. “Åmosen - Vestjællands Grønne hjerte- Handlingsplan for naturgenopretning og beskyttelse af kulturmiljøet i den østre del af Store Åmose.” Danish Ministry of the Environment. (In Danish). https://www2.skovognatur.dk/udgivelser/2002/aamosen/af72.pdf.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2006. “Hvidsbog over høringssvar og ministerbesvarelser vedr. Skitseprojektering af naturgenopretningsprojekt I den østlige del af Åmosen.” Danish Ministry of the Environment (In Danish). https://naturstyrelsen.dk/media/nst/attachments/79356/hvidbog_samlet.pdf.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2022. “Opgørelse over antallet af § 3 registrerede arealer for de enkelte naturtyper samt fordeling på størrelseskategorier.” Danish Ministry of the Environment. (In Danish). https://mst.dk/media/114356/mose.pdf.

- Olesen, K., and T. Richardson. 2012. “Strategic Planning in Transition: Contested Rationalities and Spatial Logics in Twenty-First Century Danish Planning Experiments.” European Planning Studies 20 (10): 1689–1706. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.713333.

- Puhakka, R. 2008. “Increasing Role of Tourism in Finnish National Parks.” Fennia – International Journal of Geography 186 (1): 47–58. https://fennia.journal.fi/article/view/3711.

- Rudolph, D., and J. K. Kirkegaard. 2019. “Making Space for Wind Farms: Practices of Territorial Stigmatisation in Rural Denmark.” Antipode 51 (2): 642–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12428.

- Rytteri, T., and R. Puhakka. 2016. “The Art of Neoliberalizing Park Management: Commodification, Politics and Hotel Construction in Pallasyllästunturi National Park, Finland.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 94 (3): 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2012.00413.x.

- Saarinen, J., and M. A. Gill. 2019. “Introduction: Placing Resilience in the Sustainability Frame.” In Resilient Destinations and Tourism: Governance Strategies in the Transition Towards Sustainability in Tourism, edited by J. Saarinen and M. A. Gill, 3–12. London: Routledge.

- Salvatore, R., E. Chiodo, and A. Fantini. 2018. “Tourism Transition in Peripheral Rural Areas: Theories, Issues and Strategies.” Annals of Tourism Research 68 (3): 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.003.

- Silverman, D. 2006. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Sørensen, F., and T. S. Grindsted. 2020. Service- og oplevelsesorienterede forretningsmodeller i naturparker Karakteristika, muligheder og begrænsninger. Roskilde, DK: Roskilde Universitet.

- Sørensen, F., and T. S. Grindsted. 2021. “Sustainability Approaches and Nature Tourism Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 91: 103307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103307.

- Sundbo, J., and F. Sørensen. 2013. “Introduction to the Experience Economy.” In Handbook on the Experience Economy, edited by J. Sundbo and F. Sørensen. Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781004227.00005

- Van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. “Introduction to Part Fourteen: Rural Natures and their Co-Production.” In The SAGE Handbook of Nature: Three Volume Set, edited by T. Marsden. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473983007

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2