Abstract

In their invaluable annual survey of public opinion polls for Challenge, the authors have found that the economy was the number one issue for voters—specifically jobs. Donald Trump clearly exploited these concerns on an almost daily basis. Additionally, voters believe job losses were often the result of trade. They also believe lower taxes on American business would bring back jobs. These results, whether one agrees or not, are a likely guideline for Trump’s policy priorities as president.

Public opinion on the economy and trade played an important role in Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 election. Trump emphasized the connection between these issues, and his vocal criticism of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) likely contributed directly to his success, particularly among Midwestern voters in key swing states. If Trump keeps his campaign promises, he will likely pursue a threefold approach to international trade: renegotiating agreements, particularly with China and Mexico, to create more favorable terms for the United States; ending discussion of new trade agreements; and changing the tax system to incentivize American companies to return to the United States.

This article examines in particular what public opinion during the 2016 presidential election is likely to mean for trade policy during the administration of President Donald Trump. Understanding the background of these electoral circumstances provides insight into the new administration’s overall attitudes toward international trade agreements and their likely efforts in shaping new trade policy for the United States.

Public opinion on the economy and trade policies played an important role in Trump’s victories in both the Republican primary and the general election. Jobs and the economy were the top issues for many voters, and Trump emphasized these issues—particularly the connection between job loss and international trade—throughout his campaign. Trump’s vocal criticism of free trade agreements, especially the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), likely contributed directly to his success, particularly in Midwestern swing states and among Republican voters, where anti-trade attitudes were especially strong. The role of trade-related attitudes in this election is particularly of note because there have been dramatic and partisan shifts in public opinion on this topic in recent years.

Given the importance of these issues to Trump’s ascension to the White House, we anticipate the new administration will pursue these policies as promised.

ECONOMY AND JOBS A TOP ISSUE, TO TRUMP’S ADVANTAGE

Consistent with historical trends (e.g., Gallup Citation2015; Lynch Citation1999) and across a variety of polls, jobs and/or the economy was the top issue for many voters in both the primary and general elections (e.g., CBS/NYT Citation2016b; Edison Citation2016; Gallup Citation2015; Pew Research Center Citation2016b).Footnote1 Negative evaluations of the economy and American job prospects frequently correlated with voting for or intent to vote for Trump.

In February 2016, during the primary season, 92 percent of Republicans said that presidential candidates’ positions on the economy would be extremely or very important in determining their vote for president. Another 80 percent of Republicans said employment and jobs would be extremely or very important (Gallup Citation2016a). In the same month, Republican primary voters were most likely to rank jobs and the economy as the most important issue in deciding who to support in the primaries (Quinnipiac Citation2016a).

Beyond Republicans, Americans more generally also shared this focus, throughout the primary and general election cycle. In May 2015, 86 percent of Americans said the economy, more than any other issue, would be extremely or very important to their 2016 vote for president (Gallup Citation2015). Just over a year later, in June 2016, 84 percent of registered voters again said the economy was very important to their vote choice (Pew Research Center Citation2016a). Additionally, the importance of the economy seemed to grow as the general election drew nearer. In September 2016, nearly a third (32%) of registered voters identified the economy and jobs as the single issue that would be most important to them in their presidential vote choice, selected more than any other issue; in the week before the election, that number had grown to 38 percent of voters (CBS/NYT Citation2016b).

However, identifying “the economy” generally as a top concern or issue can mean a variety of different, more specific concerns. Previous polling shows that when registered voters who list the economy as an important presidential voting issue are asked to explain more specifically in their own words what they mean, a plurality (about one-third) say something related to jobs specifically, such as job loss, creation, or outsourcing (KFF/PSRA Citation2008). The 2016 election followed this trend. Asked shortly before the 2016 election to choose from a list of specific economic issues (rather than “the economy” generally), 43 percent of registered voters (and roughly equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats) said that “the job situation” would be among the two most important economic issues in their presidential vote choice (Pew Research Center Citation2016b). An additional 16 percent identified global trade as a top-two issue in their vote choice.

Throughout his campaign, Trump responded to these concerns and repeatedly emphasized economic issues, to great effect in both the primary and general elections: Americans who negatively evaluated the economy or their personal financial situation were more likely to vote for Trump than those who offered positive evaluations.

For example, in the primary season, Republican voters who strongly agreed with the statement “I feel as though I’m falling further and further behind economically” were more likely to say they preferred Trump (46%) to Cruz (26%) or Kasich (23%) (Quinnipiac Citation2016b). In polling conducted in the days leading up to the general election (Edison Citation2016), 62 percent of Americans said the national economy was in not good or poor condition. Of those who said this, nearly two-thirds (62%) ultimately voted for Trump. Similarly, among those who said their financial situation was worse today compared to four years ago, 77 percent voted for Trump.

Trump also mirrored interpretations of “the economy” generally as about job loss or opportunity specifically, and he consistently connected concern for jobs with the perils of international trade. Repeatedly throughout his campaign (and since his election), Trump noted the decline of U.S. manufacturing jobs and other employment opportunities and frequently attributed these losses to NAFTA and other trade deals.Footnote2 Trump’s stance on free trade agreements ultimately proved important to his success in both the Republican primary and the general election, as discussed next.

FREE TRADE, LOST JOBS, AND MIDWESTERN VOTERS

Since the post–World War II era, the Republican Party has generally been the party of free trade (Hunt Citation2016). NAFTA was originally proposed and negotiated by Republican President George H. W. Bush, and in 1993, it was passed by Congress with significantly more Republican than Democratic votes in favor (Civic Impulse Citation2017a). More recently, Republican elected officials in Congress voted nearly unanimously in favor of trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and Korea in 2011 (Civic Impulse Citation2017b, Citation2017c, Citation2017d). The 2012 Republican national platform further emphasized international trade as “crucial for our economy,” saying that such trade “means more American jobs, higher wages, and a better standard of living” (RPP Citation2012). Skepticism against free trade was, until recently, largely “relegated to the fringes of the Republican Party” (Appelbaum Citation2016).

Trump, however, positioned himself loudly and clearly against existing free trade deals, with especially harsh criticism for NAFTA and for U.S. trade relationships with Mexico and China. Trump’s vocal criticism of free trade policy, among other stances, led to his often being described by some as antiestablishment, “an anti-Republican Republican,” or “starting a trade war—with the Republican Party” (e.g., Sullivan and Johnson Citation2016). While this made waves within the party establishment, it resonated with Republican party voters: nearly 7 in 10 (68%) of Republican registered voters thought free trade agreements were a bad thing for the United States (Pew Research Center Citation2016c). According to ABC exit polling during the Republican primaries, a majority of Republican voters believed that trade takes away U.S. jobs, and Trump won these voters “by large margins in Michigan, Mississippi, Illinois, and North Carolina, while essentially tying with Kasich in Ohio” (Holyk Citation2016). As a result, noted the New York Times, “Mr. Trump has set the agenda, and no [Republican] presidential candidate is carrying a free-trade banner” (Hunt Citation2016).

In the general election, Trump’s position on NAFTA and trade deals again proved influential. One-third (33%) of the public and nearly half of Republicans (47%) said that, over the past ten years, trade agreements have hurt individuals in their own community (Politico/HSPH Citation2016) (Table ). In the months leading up to the general election, those who believed that past free trade agreements such as NAFTA (specifically mentioned in the survey question) had hurt their community were far more likely to say, across a variety of questions, that free trade policies hurt the United States, have lost U.S. jobs, and have lowered U.S. wages (Politico/HSPH Citation2016) (Table ). Overall, nearly half of registered voters said free trade agreements generally have been a bad thing for the United States (Pew Research Center Citation2016c).

TABLE 1 Perceived Impact over the Past Ten Years of Free Trade Agreements on Individuals in Own Community, 2016, by Party Identification and Region (%)

TABLE 2 Views of Trade Policies, 2016, by Perceived Effect of Free Trade on Own Community (%)

As shown above, negative evaluations of the current economy and free trade corresponded with voting for Trump. In national exit polling during the general election (Edison Citation2016), slightly more voters overall said international trade took away U.S. jobs (42%) rather than created them (39%). Among those who believed international trade took away U.S. jobs, nearly two-thirds (64%) voted for Trump.

But Trump’s trade-related advantage was clearest in the Midwest. In the months leading up to the general election, people in the Midwest (53%) were twice as likely to say that free trade agreements hurt their communities than were people in any other region of the country (27% Northeast, 27% South, 26% West) (Politico/HSPH Citation2016) (Table ).Footnote3 Four of the six states that flipped from Barack Obama in 2012 to Donald Trump in 2016 were in the Midwest (Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin).Footnote4

In Michigan (50%), Wisconsin (50%), and Ohio (48%), far more voters thought international trade took away rather than created U.S. jobs; Trump won 58 percent to 69 percent of the voters who held this view (Edison Citation2016) (Table ). In Pennsylvania, a non-Midwestern state that also flipped to Trump, this belief was even stronger: 53 percent said international trade takes away U.S. jobs, and nearly two-thirds (64%) of Pennsylvanians who shared that belief voted for Trump (Edison Citation2016).

TABLE 3 Views of 2016 Voters on the Impact of International Trade on U.S. Jobs, by State (%)

In sum, during the 2016 election, considerable portions of the American public believed that free trade agreements have had negative impacts on Americans and American jobs. Nearly six in ten (59%) registered voters said either the job situation or global trade were the two most important economic issues to their vote for president (Pew Research Center Citation2016b). These attitudes were particularly prevalent in key Midwest swing states, and these attitudes consistently corresponded with support for Trump, including in these same Midwest swing states.

This combination of economic and job concerns, Trump’s conspicuously vocal anti-NAFTA stance, and the public’s view of the (negative) impact of free trade agreements all contributed to Trump victories in both the primary and general elections. This is particularly striking given that the public’s attitudes on free trade have shifted dramatically in recent years.

CHANGES IN TRADE-RELATED PUBLIC OPINION

In two trade-related areas, there have been significant changes in public attitudes in recent years. First, general opinion toward free trade and free trade agreements has varied considerably over recent years, including a notable partisan shift in evaluations of free trade. Second, attitudes toward free trade have also varied over time depending on the partner country.

Public and Partisan Evaluations of the Impact of Free Trade

As this article demonstrates, public belief in the harmful impacts of free trade agreements played an important role in the Republican primary as well as in the general presidential election. However, two key observations are important. First, the American public distinguishes between trade’s impact on the U.S. economy generally and on U.S. jobs specifically. Second, beliefs about the negative effects of trade are growing—particularly among Republican voters. Historically, both the general public and Republican voters were more supportive of free trade agreements than they are today.

Generally speaking, Americans are more positive about international trade’s impact on the U.S. economy than they are about trade’s impact on U.S. jobs and wages. For example, while 59 percent of Americans say international trade is good for the U.S. economy overall, only 40 percent say it is good for creating U.S. jobs, and even fewer (35%) say it is good for American job security more generally (Chicago Council Citation2016). Similarly, in 2015, 58 percent of Americans said free trade agreements have been a good thing for the United States, but a plurality said these same agreements lower American wages (46%) and lead to U.S. job losses (46%) (Pew Research Center Citation2015).Footnote5

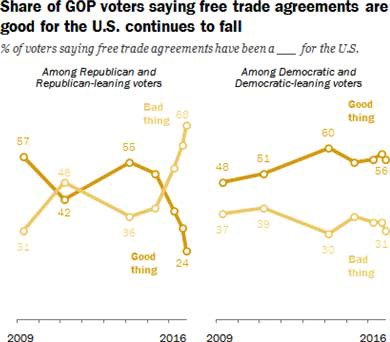

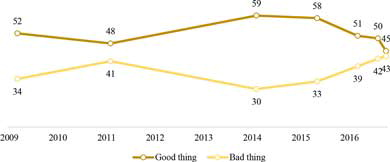

Increasingly, Americans are more likely to express skepticism over international trade. For example, the proportion of Americans who believe that free trade agreements with other countries is a good thing for the United States has steadily declined, from a peak of 59 percent in 2014 to 45 percent just before the 2016 presidential election (Figure ) (Pew Research Center Citation2016c).Footnote6

FIGURE 1 American Opinion on Impact on U.S. of Free Trade Agreements. % of voters saying free trade agreements have been a ___ for the U.S.

Similarly, Americans are also more likely now than in the past to believe that these deals cost U.S. jobs (Table ). In 1996, roughly equal proportions of registered voters believed that U.S. trade with other countries leads to U.S. job losses (42%) or job creation (39%) (CBS/NYT Citation1996). By 2003, a majority (53%) of the public said that trade with other countries loses U.S. jobs (TIPP/IBD/CSM Citation2003). By 2016, that number grew to 60 percent, including 75 percent of those who said they would vote for Trump (CBS/NYT Citation2016a).

TABLE 4 Registered Voters’ Views of Whether U.S. Trade with Other Countries Creates or Loses More U.S. Jobs, 1996, 2016 (%)

Though it appears the general public as a whole has grown more skeptical of international trade deals, an examination by partisanship reveals a different story: as shown in Figure (Pew Research Center Citation2016c), Republicans and Democrats differ markedly on the impact of trade on the U.S. generally, a difference that has developed rapidly in recent years.Footnote7

This partisan divide is also prevalent in evaluations of the impact of trade on U.S. jobs specifically. As Tables and show, “since 2006, Democrats have become more optimistic, and Republicans less optimistic, about the impact of trade” (Smeltz, Kafura, & Wojtowicz Citation2016). In 2006, equal numbers (38%) of both parties said trade has been good for creating U.S. jobs, but by 2016 Republicans were less likely to believe this (34%) and Democrats were significantly more likely (47%) (Table ) (Chicago Council Citation2016). Similarly, in 2006, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to say that trade leads to U.S. job losses, but by 2016, the parties had switched (Table ) (Pew Research Center Citation2006, Citation2015). Republicans are now more likely than Democrats to hold negative beliefs about the impact of trade on American jobs and the economy.Footnote8

TABLE 5 Republican and Democratic Opinions on Whether International Trade Has Been Good for Creating Jobs in the U.S., 2006, 2016 (%)

TABLE 6 Republican and Democratic Opinions on International Trade on Leading to Job Loss in the U.S., 2006, 2015 (%)

These findings illustrate the notable shifts not only in American views of free trade overall, but especially in partisan views.

Country-Specific Attitudes

Another notable shift in public opinion on trade policy is in public attitudes toward trade with specific countries. In general, American views on international trade depend on the country with whom America is trading. These views vary both within and between political parties.

Throughout his campaign, Trump focused much of his criticism of trade agreements on China and Mexico (e.g., Ehrenfreund Citation2016; Newport Citation2016). Here again his views reflected those of his own party’s constituents, as Republican voters were most seriously concerned about trade issues with those two countries specifically, more so than with other trading partner countries (Politico/HSPH Citation2016). In fact, Trump outperformed previous Republican presidential candidates in counties that lost jobs to Mexico and China (Cerrato, Ruggieri, and Ferrara Citation2016).

As is frequently the case in a variety of issues (e.g., Hetherington and Rudolph Citation2015), the political parties were (and are) polarized in their attitudes about the effect of free trade with specific countries, especially China and Mexico. As Figure shows, there were significant differences both within and between parties on attitudes toward free trade with specific countries. More than six in ten Republicans believe that free trade with China (64%) and Mexico (61%) has hurt the United States. In contrast, 38 percent of Democrats believe that free trade with China hurts the United States., and only 17 percent believe that free trade with Mexico hurts the United States(Politico/HSPH Citation2016) (Figure ).

The current focus on China and Mexico highlights an interesting change in American attitudes about the economic relationship between the United States and other countries. While attitudes toward China and Mexico are relatively hostile today, these negative opinions were historically focused on other countries, especially those viewed as a threat to the United States at the time.Footnote9

For example, in 1991, more than three-fourths (77%) of the American public believed that Japan was an economic threat to the United States, and many expressed negative attitudes toward Japan: nearly 7 in 10 (69%)Americans said that Japan had taken unfair advantage of the United States (Times Mirror/PSRA Citation1992). By 2016, however, the proportion of the public that considered Japan an economic threat had declined sharply to 24 percent (Gallup Citation2016b), and so had hostile attitudes toward the relationship with Japan: only 21 percent of Americans now think that trade with Japan hurts the United States (Politico/HSPH Citation2016).

Furthermore, similar to the Trump administration’s proposed sanctions, tariffs, and other proposed policies restricting or affecting trade with Mexico and China, both the Bush I (Sanger Citation1992) and Clinton (Destler Citation2005) administrations threatened restrictions on trade with Japan—a country perceived as an economic threat to the United States at the time (see also Brainard Citation2001).

Economic threats can be perceived for many reasons. Today, China’s threats are often described in terms of the U.S.-China trade deficit, outsourced manufacturing jobs, U.S. debt held by China, and the sheer size of China’s population and economic power, among others (e.g., Flowers Citation2016; Pew Research Center Citation2012). While Mexico has a different relationship to the U.S. economy, at the time of NAFTA’s original negotiation, trade unions and other groups were deeply opposed due to concerns that Mexico would pose a similar economic threat to the United States, particularly in the form of job loss and outsourcing (Destler Citation2005)—an argument also made frequently and famously during the presidential campaign of Ross Perot. As this article argues, and as Trump’s rhetoric indicates, similar concerns, arguments, and perceptions about the loss of jobs and wages to Mexico and other countries arose again during the 2016 election.

American opinion toward international trade depends on the specific country or trading partner. These country-specific attitudes also can change dramatically over time, and likely are related to the perceived threat that a country poses to the American economy.

EXPECTATIONS

Donald J. Trump’s election to the White House was not based on the nationwide popular vote, where he in fact trailed Democrat Hillary Clinton by nearly three million votes (Cook Political Report Citation2017). Rather, several important factors helped Trump secure the White House. As discussed in this article, the economy, jobs, and foreign trade played central roles in the election. These issues were of particular importance to Republican voters and voters in key Midwest swing states. Ultimately, Trump won an overwhelming proportion of the Republican vote (Edison Citation2016), garnering roughly two million more votes than Mitt Romney in 2012 and more overall than any Republican candidate in history (Cook Political Report Citation2017; Roper Citation2017). He also won major swing states, including Pennsylvania and key states in the Midwest.

What are these election results likely to mean for the trade policies of the Trump administration? Given the nature of his victory, where he did not win the overall popular vote but did win these two particular groups of voters, President Trump is likely to pay particular attention to the views of his Republican constituents and to residents of these key swing states, which will be critical to his 2020 reelection campaign.

Indeed, considerable literature in political science demonstrates the tendency of elected officials to be more responsive to voters of their own party or other subconstituencies, rather than the broader public or their constituency as whole (Bishin Citation2010; Egan Citation2013; Kastellac et al. Citation2015). Additionally, Americans are more likely to contact elected officials from their own party, likely influencing elected officials’ perceptions of their district’s opinion as consistent with the official’s own views (Broockman and Ryan Citation2016) and potentially exacerbating ongoing polarization.

Shortly before Trump’s inauguration, 55 percent of Trump voters considered withdrawing from or negotiating better terms for NAFTA to be an extremely or very important priority for his first 100 days (Politico/HSPH Citation2017). Therefore, we can expect the Trump administration to pursue withdrawing from or significantly renegotiating NAFTA and other trade deals, even when such actions might conflict with the preferences of the American public at large.

Prior polling also suggests that the debate on the Trans-Pacific Partnership is unlikely to proceed: a large majority (63%) of those who have heard of the proposed agreement oppose it (Politico/HSPH Citation2016). Among those who have heard of the TPP and thought past trade hurt their community, 92 percent oppose Congress’s approving the TPP (Politico/HSPH Citation2016) (Table ). Based on this data, President Trump’s recent decision to end U.S. involvement in the TPP (White House Citation2017b) comes as no surprise.

One final implication for Trump administration trade and economic policy is this: nearly two-thirds (63%) of the public—including 91 percent of those who said they had voted for Donald Trump—believe that lowering U.S. corporate taxes would be effective at bringing jobs back to the United States (Politico/HSPH Citation2017). Therefore, this approach is likely to be a part of President Trump’s trade and tax policy agenda when the overall issue is addressed.

In conclusion, attitudes toward the economy and international trade—combined with Trump’s uniquely (among Republican candidates) critical stance on NAFTA—played a key role in Donald Trump’s electoral victory. This is particularly notable considering the changes in American attitudes on trade in recent decades.

Given the importance of these trade issues in his primary and general election victories, we expect him to pursue these policies during his presidency. If Trump keeps his promises to his voters, he is likely to pursue a threefold approach to international trade: renegotiating trade agreements, particularly with China and Mexico to make the deals more favorable to the United States; ending discussion of new trade agreements and any consideration of the TPP treaty (the latter being already accomplished in the first month of his presidency); and changing the tax system to provide strong incentives for American companies to come back to the United States.

While the broader implications of the Trump administration’s agenda are not fully known, they are likely to have a significant impact, whether substantively or symbolically, on both those who profit from and invest in international trade, as well as those who are hurt by it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Tiffany Chan, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, for her research assistance, and Alton B.H. Worthington, University of Michigan, for his feedback on this manuscript.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert J. Blendon

Robert J. Blendon, Sc.D., is a professor at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Logan S. Casey

Logan S. Casey, Ph.D., is research analyst in public opinion.

John M. Benson

John M. Benson, M.A., is managing director at the Harvard Opinion Research Program at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Notes

One limitation of the following analysis is that, since the reported data come from different polls and polling organizations over several decades, the denominators vary. For example, in some cases, the data describe registered voters, while in other cases they describe likely voters or the general public. Often these variations are based on when the poll was conducted relative to an election: as an election grows nearer, polls are often more likely to focus on registered or likely voters. We identify these samples for clarity throughout the text. When making comparisons over time, we only report large changes (e.g., ≥10 points) that would be less subject to the impact of differences in sampling (i.e., the differences are large enough that they would not be due to sampling). As a result, we do not expect that these sampling differences should result in meaningful differences in the substantive interpretations of data patterns (i.e., our general arguments here) but rather only small differences in point estimates.

See, for example, “Trade Deals Working for All Americans” as a top issue on the Trump White House’s website: “For too long, Americans have been forced to accept trade deals that put the interests of insiders and the Washington elite over the hard-working men and women of this country. As a result, blue-collar towns and cities have watched their factories close and good-paying jobs move overseas, while Americans face a mounting trade deficit and a devastated manufacturing base” (White House Citation2017a).

“Midwest,” defined by the U.S. Census 4-Region division, includes: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

The remaining two are Pennsylvania, another state significantly affected by the loss of manufacturing and other jobs, and Florida.

During the 2016 presidential election cycle, that 58 percent of Americans who said free trade agreements have been a good thing for the United States rapidly declined to 45 percent in just under 18 months (May 2015–October 2016) (Pew Research Center Citation2015, Citation2016c). We present the 2015 data point here because in 2016, Pew did not ask questions about trade’s impact on job loss or wage rates.

Pew Research Center data on this topic extends back to 1997, but with considerable variation in question wording, which affects responses and reduces comparability. Here we present only questions with the wording: “In general, do you think that free trade agreements between the U.S. and other countries have been a good thing or a bad thing for the United States?”.

It is important to note that these data cover only the years of the Obama administration, and it is therefore possible that recent changes in opinion on trade are mainly partisan: in other words, it should not be surprising that Democrats became more positive and Republicans more negative about trade and trade policies pursued by a Democratic administration. While the strength of polarization is certainly part of the story, particularly under President Obama (see Jones Citation2015), the idea that voters’ evaluations of policies change depending on the party in power (or elite cue-taking more generally) does not alone account for historical intraparty divisions on this issue, such as Democratic voters and constituencies (e.g., labor and the environment) taking vocal antitrade positions under President Bill Clinton, who ultimately supported NAFTA and pushed for free trade expansion during his presidency (e.g., Destler Citation2005; Ifill Citation1992). Additionally, Table shows that Democrats also held more positive views on free trade than Republicans, even under a Republican president (Bush II).

Importantly, while in recent years Republican voters have become more negative than Democrats about the impact of trade deals, Republican voters have also become more negative than their own party leaders, as discussed above.

This is consistent with recent work (Mansfield and Mutz Citation2009; Sabet Citation2014, Citation2016) illustrating the influence of symbolic attitudes and feelings on the formation of public opinion about international trade: “Like all political issues, trade is associated with symbols that correspond directly to longstanding symbolic attitudes, triggering an automatic affective shortcut. Most notably, international trade represents a transaction with a ‘foreign other.’ Thus, it should evoke a gut-level response based on general, stable, and early learned predispositions such as attitudes toward out-groups or foreignness. To put it in the language of heuristics, the difficult and complex question—‘What do I think about trade?’—is displaced by the much easier question: ‘How do I feel about it?’” (Sabet Citation2016, 7). Attitudes toward trade with a particular country are not simply attitudes about trade but attitudes about that country as well.

REFERENCES

- Appelbaum, B. 2016. “On Trade, Donald Trump Breaks with 200 Years of Economic Orthodoxy.” New York Times, March 10. Available at https://nyti.ms/2kbuOQp, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Bishin, B. 2010. Tyranny of the Minority: The Subconstituency Politics Theory of Representation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Brainard, L. 2001. “Trade Policy in the 1990s.” Brookings Institution. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/trade-policy-in-the-1990s/, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Broockman, D., and T. J. Ryan. 2016. “Preaching to the Choir: Americans Prefer Communicating to Copartisan Elected Officials.” American Journal of Political Science 60, no. 4: 1093–1107.

- CBS News/ New York Times Poll (CBS/NYT). 1996. (survey dates February 22–24). Available at http://www.realclearpolitics.com/docs/2016/CBS_NYT_July_2016.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016a. July 14 (survey dates July 8–12). Available at http://www.realclearpolitics.com/docs/2016/CBS_NYT_July_2016.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016b. November (survey dates October 28–November 1). Available at https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/3213875/Poll.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Cerrato, A., F. Ruggieri, and F. Ferrara. 2016. “Trump Won in Counties that Lost Jobs to China and Mexico.” Washington Post, December 2. Available at http://wpo.st/Dc-W2, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Chicago Council on Global Affairs/GfK Custom Research Poll (Chicago Council). 2016. (survey dates June 10–27). Available at https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/ccgasurvey2016_america_age_uncertainty.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Civic Impulse. 2017a. H.R. 3450—103rd Congress: North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act. Available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/103/hr3450, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2017b. H.R. 3078—112th Congress: United States-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement Implementation Act. Available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr3078, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2017c. H.R. 3079—112th Congress: United States–Panama Trade Promotion Agreement Implementation Act. Available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr3079, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2017d. H.R. 3080—112th Congress: United States-Korea Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act. Available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr3080, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Cook Political Report. 2017. “2016 Popular Vote Tracker.” Available at http://cookpolitical.com/story/10174, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Destler, I. 2005. American Trade Politics, 4th ed. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

- Edison Research National Exit Poll (Edison). 2016. November (survey date November 8). http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Egan, P. 2013. Partisan Priorities: How Issue Ownership Drives and Distorts American Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ehrenfreund, M. 2016. “The Mystery of Why Donald Trump Focuses So Much on Trade.” Washington Post, September 27. Available at https://wpo.st/Pvdb2, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Flowers, A. 2016. “Why Critics of Free Trade Are Talking China, not NAFTA.” Five Thirty Eight, August 18. Available at http://53eig.ht/2byh5NB, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Gallup Poll. 2015. May 15 (survey dates May 6–7). Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/183164/economy-trumps-foreign-affairs-key-2016-election-issue.aspx, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016a. February 1 (survey dates January 21–25). Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/188918/democrats-republicans-agree-four-top-issues-campaign.aspx, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016b. December 7 (survey dates November 28–29). Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/199115/fewer-japan-economic-threat.aspx, accessed February 15, 2016.

- Hetherington, M., and T. Rudolph. 2015. Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Holyk, G. 2016. “Foreign Policy in the 2016 Presidential Primaries Based on the Exit Polls.” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, April 7. Available at https://shar.es/19b2vn, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Hunt, A. 2016. “Trump Targets Free Trade, and G.O.P. Follows Suit.” New York Times, February 21. Available at https://nyti.ms/2k4JE7W, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Ifill, G. 1992. “THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: The Democrats; With Reservations, Clinton Endorses Free-Trade Pact.” New York Times, October 5. Available at https://nyti.ms/1r9uBgi, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Jones, J. 2015. “Obama Approval Ratings Still Historically Polarized.” Gallup. February 6. Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/181490/obama-approval-ratings-historically-polarized.aspx, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Kaiser Family Foundation/Princeton Survey Research Associates Poll (KFF/PSRA). 2008. March survey dates February 7–16). Available at https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2008/03/7751_topline.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Kastellac, J., J. Lax, M. Malecki, and J. Phillips. 2015. “Polarizing the Electoral Connection: Partisan Representation in Supreme Court Confirmation Politics.” Journal of Politics 77, no. 3: 787–804. doi:10.1086/681261

- Lynch, G. 1999. “Presidential Elections and the Economy 1872 to 1996: The Times They Are a ‘Changin or the Song Remains the Same?” Political Research Quarterly 52, no. 4: 825–44.

- Mansfield, E., and D. Mutz. 2009. “Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest, Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety.” International Organization 63, no. 3: 425–57.

- Newport, F. 2016. “American Public Opinion on Foreign Trade.” Gallup. April 1. Available at http://www.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/190427/american-public-opinion-foreign-trade.aspx?g_source=Polling%20Matters&g_medium=sidebottom&g_campaign=tiles

- Pew Research Center Poll (Pew Research Center). 2006. December 19 (survey dates December 6–10). Available at http://www.people-press.org/2006/12/19/free-trade-agreements-get-a-mixed-review/, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2012. September 18 (survey dates Apr 30–May 13). Available at http://www.pewglobal.org/2012/09/18/u-s-public-experts-differ-on-china-policies/, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2015. May 27 (survey dates May 12–18). Available at http://www.people-press.org/2015/05/27/free-trade-agreements-seen-as-good-for-u-s-but-concerns-persist/#survey-report, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016a. July 7 (survey dates June 15–26). Available at http://www.people-press.org/2016/07/07/2016-campaign-strong-interest-widespread-dissatisfaction/, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016b. October 6 (survey dates September 1–4). Available at http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/10/ST_2016.10.06_Future-of-Work_FINAL4.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2016c. October 27 (survey dates October 20–25). Available at http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2016/11/03170033/10-27-16-October-political-release.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Politico/Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Poll (Politico/HSPH). 2016. September (survey dates August 31–September 4). Available at https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2016/10/POLITICO-Harvard-Poll-Sept-2016-Trade-and-Health.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2017. January (survey dates December 16–20, 2016). Available at https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2017/01/POLITICO-Harvard-Poll-Jan-2017-Trumps-First-100-Days.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Quinnipiac University Poll (Quinnipiac). 2016a. February (survey dates February 10–15). Available at https://poll.qu.edu/national/release-detail?ReleaseID=2323, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ___. 2016b. April 5 (survey dates March 16–21). Available at https://poll.qu.edu/national/release-detail?ReleaseID=2340, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Republican Party Platforms (RPP). 2012. 2012 Republican Party Platform. Provided online by G. Peters and J. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. August 27. Available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=101961, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (Roper). 2017. “Popular Votes 1940–2012.” Available at https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/polls/us-elections/popular-vote/, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Sabet, S. 2014. “What’s in a Name? Investigating the Effect of Prejudice on Individual Trade Preferences.” Presented at the 109th Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August, Chicago, IL.

- ______. 2016. “Feelings First: Non-Material Factors as Moderators of Economic Self-Interest Effects on Trade Preferences.” Under review at International Organization. Available at http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ssabet/files/sabet_feelings_first_.pdf, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Sanger, D. 1992. “BUSH IN JAPAN; A Trade Mission Ends in Tension as the ‘Big Eight’ of Autos Meet.” New York Times, January 10. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/10/us/bush-in-japan-a-trade-mission-ends-in-tension-as-the-big-eight-of-autos-meet.html?pagewanted=all, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Smeltz, D., C. Kafura, and L. Wojtowicz. 2016. “Actually, Americans Like Free Trade.” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, September 7. Available at https://shar.es/19bGZM, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Sullivan, S., and J. Johnson. 2016. “Donald Trump Starts a Trade War—with the Republican Party.” Washington Post, June 30. Available at http://wpo.st/A3DZ2, accessed February 15, 2017.

- Times Mirror Center for the People, the Press & Politics/Princeton Survey Research Associates Poll (Times Mirror/PSRA). 1992 (survey dates May 28–June 10; survey question: USPSRA.070892.R50NN2). Cornell University, Ithaca, NY: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL (subscription database; distributor). Accessed February 15, 2017.

- TIPP/Investor’s Business Daily/Christian Science Monitor Poll (TIPP/IBD/CSM). October 2003 (survey dates October 6–10; survey question: USTIPP.03OCT.R41). Cornell University, Ithaca, NY: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, iPOLL (subscription database; distributor).Accessed February 15. 2017.

- The White House. 2017a. “Trade Deals Working for All Americans.” Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/trade-deals-working-all-americans, accessed February 15, 2017.

- ______. 2017b. “Presidential Memorandum Regarding Withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations and Agreement.” January 23. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/23/presidential-memorandum-regarding-withdrawal-united-states-trans-pacific, accessed February 15, 2017.