ABSTRACT

The world empire created by the Mongols in the thirteenth century was based upon a system of loyalties to different figures, families and institutions. This article explains some of the key “objects of loyalty” at the heart of the Mongol Empire and at a regional level. These loyalties, when acting in concert, served as the glue which bound the Mongol Empire together, but when they came into conflict, served to weaken and finally collapse the unity of the empire. Disagreements about the legacy and will of Chinggis Khan led to diverging loyalty decisions in succession struggles in the mid-thirteenth century and the breakdown of the empire into smaller khanates. This article will examine the system of loyalty as it functioned in the early thirteenth century and how it broke down in the late thirteenth century.

Loyalty is a concept that is often mentioned or implied in studies on the Mongol Empire, but it has rarely, if ever, been considered as its own topic. This article focuses on one aspect of loyalty in the early Mongol Empire of Chinggis Khan and his successors. The inspiration for this choice of topic was Thomas Welsford’s excellent work, Four Types of Loyalty in Early Modern Central Asia (2012).Footnote1 In this book, Welsford elaborates on categories of loyalty which show themselves in the transfer of power between two Chinggisid dynasties in the Uzbek Khanate which ruled much of Central Asia in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. As the Uzbek Khanate was also ruled by Chinggisids, there appeared to be many recurring themes and parallels which could be applied to the early Chinggisid Mongol empire. Analysing Welsford’s categories is beyond the scope of this article, however, it was in the hope of providing something similar for the early Mongol period that I began this research. Welsford’s work focuses mainly on the different Chinggisid pretenders to the Uzbek khanate, and their successes or failures in attracting the loyalty of key players in the region. When considering the early Mongol world however, it becomes readily apparent that there were, in fact, multiple claimants of loyalty, not just pretenders to the khanate. In order for such a large political entity to function correctly, there had to be more low-level loyalty obligations which tied the larger part of society into a coherent system. Determining the structure which linked the objects of loyalty is necessary for a clearer understanding of the general concept throughout the Mongol world. We will consider the system in its functionality, but also look at how it could break down. Even at the top of Mongol society, there were often several rival objects of loyalty, whether these be individuals, roles, institutions or even ideas. As we shall see, these claimants on loyalty often collided, leading to fractures that were sometimes papered over but could be easily re-opened.

In selecting the “objects of loyalty”, as I call them, I have tried to limit these to what our sources have decided are worthy of loyalty, though there may be many omissions of both sources and potential loyalty claimants within the sources I do use. The main works considered here are the works of the Persian historians Juvaini and Rashid al-Din and the anonymous Mongol work, The Secret History of the Mongols, where much of the discourse about loyalty in the contemporary Mongol world was created. Naturally other sources, such as European travel accounts and Armenian chronicles, are also considered to provide a wider scope of opinion outside the centres of Mongol power. Due to the lack of works focusing specifically on loyalty, this terminology is of my own creation. What do I mean then when I talk about an “object of loyalty”? At its most basic, this means whatever our sources describe as someone or something which people in the Mongol world should show loyalty to. For the purposes of this paper, these objects are narrowed down to expressions of political loyalty. Social and religious loyalties are not dealt with except insofar as they ramify or weaken other loyalty claims. There are many instances where both social norms, such as obedience to one’s father or respect for elders, and religious prescriptions, such as adherence to the shari’a, affect political loyalty obligations.

In order to categorise these objects of loyalty, I have broken them down into three sections: loyalty objects in the pre-imperial Mongol world, loyalty objects at the centre of the Mongol imperial system, and loyalty objects at the regional level in the Mongol Empire. For the first section, unfortunately our information on the pre-imperial Mongol world is limited to that produced during the empire, so we must be aware of the possible imperial retrojections of loyalty obligations. It is included to provide the cultural basis for loyalty in the Mongol imperial system and to show what changes were apparently introduced by Chinggis and his descendants. The loyalty objects I have included for this section are the rightful lord, the törü, and the khan. The second section includes objects which our sources put at the heart of power in the empire, the qa’an/qaghan, Chinggis or Chinggis’ legacy, the previous qa’an, the jasaq, the regent, the quriltai, and the aqa. At the regional level, we shall focus on the khan/khatun of the ulus, the garrison commander (tammachi), the military governor, and finally the darughachi. We must keep in mind that these loyalties are often entangled, and that ideally many of them existed at the same time, strengthening each other. For example, in this ideal world, one’s loyalty to the jasaq, as laid down by Chinggis and which codified the role of the quriltai, would lead to the acceptance of a successor chosen by the previous qa’an and ratified by the quriltai. As Chinggis’ legendary progenitor Alan Qo’a told her sons, many arrows together are stronger than one alone.Footnote2 When the system worked correctly, these loyalties were multiple arrows that formed together a stronger union. When too many of these loyalty objects pulled in different directions, the system was breakable.

Pre-Existing Loyalty Structures

The Mongol Empire did not enter a societal or political vacuum, nor did its establishment completely do away with existing social and political systems. In fact, the sources seem to indicate that they were often very keen to reinforce the norms which preceded Chinggis’ establishment of the empire. In this light the first and possibly most basic loyalty tie outside the family was that of a servant and “rightful lord”, as rendered in Igor de Rachewiltz’s translation of the Secret History of the Mongols (henceforth SHM) for the Mongolian tus qan.Footnote3 The obligation to stay loyal to this rightful lord is one of the most consistent themes permeating the SHM. As far as we can make out, these rightful lords were the heads of noble houses, whose lineage decided their prestige within Mongol societal hierarchy. The importance of this loyalty bond has been noticed before by authors such as Paul Ratchnevsky and Morris Rossabi and dealt with more in depth in articles by Michael Hope and by Caroline Humphrey and Altanhuu Hürelbaatar, where it is connected to the törü which will be discussed in the following section.Footnote4

The author of the SHM is keen to stress on multiple occasions (shown below) that one could not abandon one’s rightful lord and go over to Temüjin (later given the title Chinggis Khan) willy-nilly, only if their lord had failed in his lordly duties, thereby sundering the loyalty agreement between lord and servant. If we consider Temüjin’s treatment of two different servants, we can see this idea in action. The first is the treatment of one Kököchü, an equerry of Senggüm, the son of Temüjin’s erstwhile ally turned rival, To’oril (r. C. 1165–1203), the Ong Khan of the Kerait people who lived to the southwest of the Mongols. After Ong Khan and Senggüm’s defeat by Temüjin, the Kerait leadership fled. Kököchü tried an opportunist move, stealing Senggüm’s horse and possessions and going over to Temüjin. As so often in the Secret History, women provide the wise reaction to socially unacceptable actions, Kököchü’s own wife telling him he has failed in his loyalty obligations to his lord. Temüjin is no more accepting of Kököchü’s actions either, killing Kököchü personally for his betrayal.Footnote5 The reverse example is shown by another of the Ong Khan’s servants, Qadaq Ba’atur. Great praise is given by Temüjin to Qadaq Ba’atur of the Jirgin who fought against Temüjin for Ong Khan. Qadaq fights long after his lord has fled and when Temüjin questions him he states that he could not let his rightful lord be killed in front of him. Temüjin praises him as a worthy companion and incorporates him into his army.Footnote6

Many further examples of both loyal and disloyal servants exist, but it seems that there was an extra taboo on the “laying of hands” on one’s rightful lord. The five companions of Jamuqa, again a previous ally turned enemy, who handed him over to Temüjin found this out, with Temüjin stating that “Black skins and slaves have gone so far as to raise their hands against their lord”, and ordering his servants to “cut down to the offspring of their offspring these people who have raised their hands against their rightful lord!”.Footnote7 There are several other instances of this extreme punishment in the SHM, indicating the keenness of Temüjin and/or the author to reinforce the hierarchical structure which existed in the Mongolian steppe, before and after Temüjin’s rise to the khanate.Footnote8 This also echoes with the later strong punishments which were meted out on those who harmed a member of the Chinggisid house or even insulted a Chinggisid. Another institution which contributed to this hierarchical stratification of Mongol society was that of the bo’ol. This term, which has widely been translated to mean “slave”, looks to have in fact been more similar to “vassal”. Tatyana Skrynnikova has shown that this Mongol term was most commonly applied by both Rashid al-Din and the SH to elites on the Mongol steppe who were either forcibly or willingly submitted themselves to Temüjin, indicating that the term related more to political than social status.Footnote9 The most famous example of this institution was the bequeathing of the two brothers, Muqali and Buqa, by their father Gu’un U’a of the Jalayir to Temüjin early in his career.Footnote10 Muqali went on to serve the Chinggisids for many years as a general and administrator in northern China. Their fates were seen as bound to their suzerains, and breaking these bonds held dire consequences. However, these bo’ol came to hold many of the highest offices in the realm as long as they served their rightful lord loyally.

A second and more abstract object of loyalty is the törü. This concept is quite ill-defined for the early Mongol period, though both in the early Turk inscriptions and later in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it meant something like the rulers’ laws.Footnote11 The word is not used by Juvaini or Rashid al-Din, but features intermittently in the SHM, where it seems to mean accepted norms and customs. Caroline Humphrey and Altanhuu Hürelbaatar in their work on regret in the early Mongol world define it in one sense as “a number of sacred political-moral principles imminent in the new order”.Footnote12 In another work, these authors emphasise that the word törü, as it is used in the SHM, means something outside the will of man, and applies to the khan just as it applies to his servants. In this way it was different from the later jasaq, which was laid down by the ruler.Footnote13 As Igor de Rachewiltz has noted, when combined with the term “yeke”, it means “the great principle”, whereby lords and subjects were obligated by their oaths to provide for each other. The subject would provide loyalty, obedience and service, while the lord would provide protection, sustenance, and reward for their subjects.Footnote14 In this sense, the törü defines and reinforces the system of oaths which existed in early Mongol society.Footnote15 The word is also combined with the term yosun, meaning custom, which itself is often combined with the term yeke, used in similar instances as the phrase yeke törü.Footnote16 Given the similarity between these terms, they can both be described as providing a sort of set of norms that governed pre-imperial Mongol society, and presumably those of their Turkic neighbours as well. Loyalty to this set of principles would see lord and servant stay true to their personal bonds, knitting together Mongol society.

Scholars such as Pochakaev, Humphrey and Hürelbaatar have argued that the Chinggisids co-opted the törü, inserting themselves in between heaven and earth as creators and mediators of the törü. Indeed, the disappearance of the term and the prevalence of the Chinggisid jasaq in our later sources does seem to indicate that they were largely successful in being able to assimilate the ideas of the törü. However, as Humphrey and Hürelbaatar indicate, references to violation of the törü in the SHM mention lords’ failures to their subjects. Thus, Ong Khan apologises to Temüjin for his separation from him, and thereby the törü, while Ögedei (r.1229–1241), Chinggis’ successor (), in his summation of his four faults as a ruler, states that he punished his father’s great servant Doqolqu despite his constant adherence to the törü.Footnote17 In this light, subjects who were mistreated or underappreciated by their lords could argue adherence to the törü when switching allegiances. The above-mentioned example of Kököchü abandoning Senggüm was reprehensible due to Senggüm not violating the törü himself in his treatment of Kököchü. On the other hand, Temüjin is seen as well within his rights in finally breaking with Ong Khan due to his failure to stick with Temüjin. Granted, the SHM is legitimising Temüjin turning on a previous ally, but clearly this avenue of complaint was open to the subject at this time. Similarly, the leaders of a group called the Je’üriyet, vassals of the Tayichi’ut, Temüjin’s relatives and rivals, claim that their lords only harass them and are aggressive towards them, while Temüjin was generous and an able ruler of the ulus (pl. ulusut, areas of land and people groups), therefore they willingly submitted themselves to him.Footnote18 Michael Hope’s analysis of the oath system of the Mongols shows that verbal oaths were exchanged, with witnesses, to indicate the reciprocal nature of this contract, a sort of reaffirmation of törü principles.Footnote19 As written oaths took the place of verbal ones over the course of the thirteenth century, both subject and lord often had something concrete which they could point to in their disputes.Footnote20 This rarely resolved these disputes, but the reciprocity of these oaths did offer some protection against overbearing lords and any imposition of “absolutism”.Footnote21 Indeed, one could argue that loyalty to the törü, as representing high moral principles, required the servant to abandon his lord if his lord showed himself unworthy of these principles.

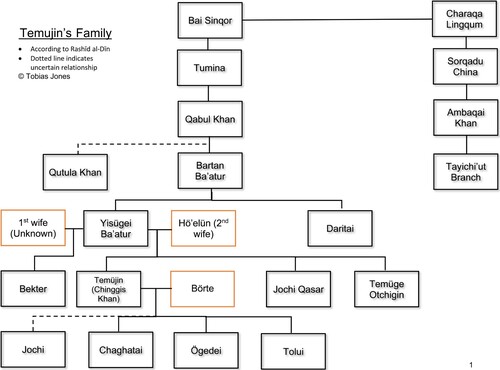

The position of khan in the pre-imperial Mongol world was not a consistently present one. This title seems to have been reserved for leaders who had united several different peoples, or key houses, under his leadership. Therefore, To’oril, who ruled over all the Kerait and their subjects, was called the Ong KhanFootnote22 in the SHM, while Temüjin’s father Yisügei does not receive this title, but rather is predominantly called ba’atur, or hero, though he was later “khanified” by Qubilai Qa’an’s (r.1260–1294) edict in 1284.Footnote23 Several of Temüjin’s Mongol ancestors before Yisügei are given the title khan (); Qabul, Temüjin’s great-grandfather, Qabul’s successor Ambaqai, forefather of Temüjin’s great rivals, the Tayichi’ut, and Qutula, perhaps the uncle of Temüjin’s father Yisügei.Footnote24 This title later became the imperial qa’an/qaghan, the khan of khans in the Mongol world.Footnote25 Temüjin himself only used the title “khan”, and it was his successor Ögedei who adopted the title qa’an. Peter Jackson and Igor de Rachewiltz argue that this adoption of the title used in the early Turk empire was influenced by the presence of Uighurs in the Mongol court familiar with Turk royal custom, conveying to the Chinggisids the more imperial status of this higher title.Footnote26

The title khan was not simply adopted however; it had to be conferred by a group of those with noble blood, e.g. the rightful lords as mentioned as the first object of loyalty. The khan himself had to come from noble birth, therefore Temüjin being of the Borjigin Mongols and a relative of the previous khans, Qabul and Qutula, was key to his elevation (). He also had to have proved his worth on the battlefield, showing that he possessed suu, or heavenly-bestowed good fortune.Footnote27 These attributes proved that he was worthy of the loyalty of the other noble houses, whose own acclamation of him brought their subjects under his rule. We can see this in the list of attendees on Temüjin’s elevation to khan, including the heads of the major houses of the Mongols, such as the Jalayir, Ikires, Ba’arin, and Jürkin.Footnote28 While the tie between subject and rightful lord formed the structure of Mongol society, the ties between these lords and an appointed khan were only made infrequently, when the need so arose. Therefore loyalty obligations had to be engendered first, before the title of khan could be bestowed.

Nor were these bonds automatically conferred on any successor. Qutula, one of Ambaqai’s chosen successors who was confirmed as khan by the Mongols and the Tayichi’ut, was supposedly succeeded by Yisügei (), but no such acclamation occurred for Yisügei, at least according to the SHM, nor did he receive the title “khan” during his lifetime.Footnote29 Here we begin to see the SHM’s attempts to pre-legitimate Temüjin. Even if his father had been khan, which we have seen was not the case, Temüjin would not automatically inherit his father’s position. The previous successions: Qabul > Ambaqai, Ambaqai > Qutula and theoretically, Qutula > Yisügei had not been from father to son, and Yisügei in fact had another son than Temüjin, Bekter, by another wife than Temüjin’s mother Höe’lün, so there were in fact many obstacles to potential succession, notwithstanding Temüjin’s young age on his father’s death. The hereditary nature of loyalty obligations only truly began with Temüjin’s descendants, as the SHM claims that later in life Temüjin had his lateral relatives, brothers and nephews, swear that they would recognise his son Ögedei as successor and keep the rule within his descendants.Footnote30 This may have been necessary due to the rivalry Temüjin had with both Bekter, his half-brother who Temüjin killed, and Jochi Qasar, Temüjin’s younger full brother who also at times rivalled him for power. Given these factors, we should be extremely wary of the SHM’s claims that the Tayichi’ut, as well as Yisügei’s younger brother Daritai, “abandoned” Temüjin when he was young.Footnote31 These were lords in their own right, and without any agreed-upon khan among them, they were free to act on their own. Without the ceremonies and oaths which accompanied formal acknowledgement of loyalty to a khan, there was no compunction on these lords, despite what our source tells us. Even Rashid al-Din acknowledges that there was no way for the Tayichi’ut to have known that God’s favour had fallen on Temüjin.Footnote32 In the SHM we see the author “imperialising” Temüjin before he had even been given the title “khan” and while he was yet a boy, despite the consistent aversion to child rulers in the Mongol world.

Imperial Innovations and Adaptations

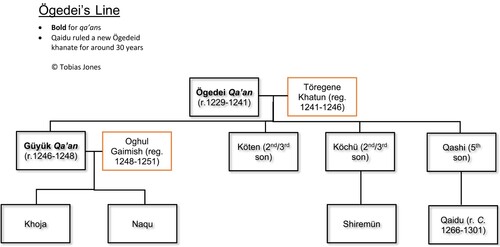

The most obvious candidate for loyalty in the imperial Mongol world was the “qa’an/qaghan” currently in power. I will explain the distinction between the sitting qa’an and the previous one in the next section, but for now let us focus on this character. Theoretically of course, everyone under Mongol dominion was loyal to the qa’an, whose position had been guaranteed by the great former leader of the Mongols, Chinggis Khan, and approved of by all the great men and women of the empire in a quriltai assembly. As we have seen in pre-imperial Mongol society, there were intermediaries between the khan and his people, and while much has been made of Chinggis’ “breakdown” of tribal structures in order to create institutions such as the keshig, the personal bodyguard of the qa’an, intermediary objects of loyalty were maintained, though perhaps often transferred from destroyed noble houses, such as the Tatars, to officials within the new Chinggisid military regime.Footnote33 It was only at the top level of Mongol society where certain figures owed their direct loyalty to the qa’an and the qa’an alone. John of Plano Carpini comments on the qa’an’s remarkable power over everyone, but this should not blind us to the structures that were in place which limited this power, and the figures within the Mongol world who commanded loyalty as well, sometimes on behalf of the qa’an, but also in opposition to him.Footnote34 One should also recognise that our sources often ascribe obligations of loyalty to contenders for the imperial position who eventually became qa’an, backdating these to further strengthen the legitimacy claims of their patrons. Juvaini therefore accuses Güyük’s (r.1246–1248) sons Khoja and Naqu () of “treachery”Footnote35 when contending for the throne with Möngke (r.1251–1258), who at the time had not yet been elected by the quriltai of 1251.Footnote36 We have already seen how Rashid al-Din claims that the Tayichi’ut should have followed Temüjin, despite the historian accepting that this sort of foresight was impossible.Footnote37 There are many such examples, nor is the backdating of loyalty unique to the Mongol world.

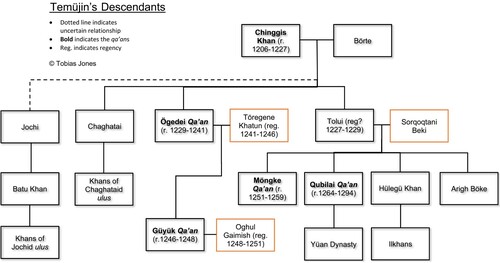

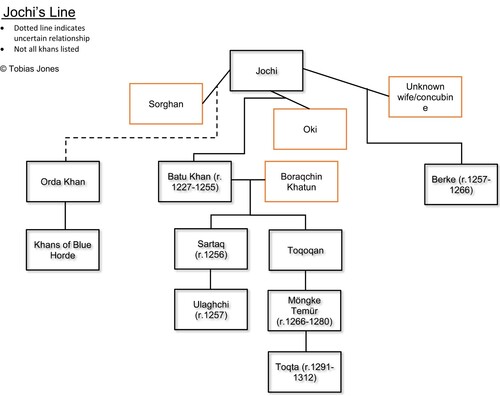

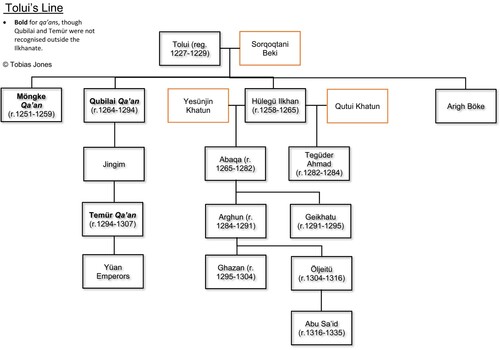

Once Chinggis Khan died in 1227, another figure was added to the list of objects of loyalty, that of Chinggis himself, but also the general role of the previous qa’an(s). Loyalty to the legacy of Chinggis as forefather and founder was shown in many ways. One of the key attributes required for succession in the Mongol world, even in the separate khanates which emerged after the breakup of the Mongol empire in 1259, was knowledge of the biligs, or wise sayings, of Chinggis Khan.Footnote38 Chinggis’ allocation of ulusut had long-term implications for the Mongol world. The Persian historian Vaṣṣāf states that in 1302/3 the khan of the ulus of Jochi (Chinggis’ eldest son, ), Toqto’a (r.1291–1312), was appealing to Chinggis’ original dispensation when claiming the lands of Arran and Azerbaijan then under the control of the Ilkhans of Persia.Footnote39 The great conqueror Temür (r.1370–1405) would create an empire and parcel it out to his sons in imitation of Chinggis in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote40 The issue of Chinggis’ laws and edicts will be dealt with in the following section on the jasaq. This practical, political legacy existed alongside a cult worship of Chinggis which developed over time. Herbert Franke has pointed out that even in Güyük’s reign, Güyük spoke of Chinggis being alive and ruler of the earth in his letter to Louis IX of France (r.1226–1270).Footnote41 Official worship of Chinggis as an ancestor was begun by Qubilai in Yuan China in the 1280s, while in Iran, under the supervision of the Ilkhans Ghazan (r.1295–1304) and Öljeitü (r.1304–1316) in the early fourteenth century (), the historian Rashid al-Din turned Chinggis into a “perfect sacred soul”.Footnote42

Much more could be said about Chinggis’ legacy, but one might imagine, given all this, that sitting qa’ans could or would not contravene Chinggis’ words or actions. However, in practice we do have some information about sitting qa’ans being able to make policy contrary to that of Chinggis, though it was not always well-received by other members of the Chinggisid house or influential noyans (military leaders). Here I will provide two examples of qa’ans contravening or changing the orders of Chinggis, given very different reviews by the sources depending on which qa’an performed such actions. Rashid al-Din gives a story where Ögedei after his succession, re-distributes troops which had belonged to Tolui’s (Chinggis’ youngest son, ) sons according to Chinggis’ dispensation to Ögedei’s own son Köten. This causes anger among some noyans, who complain of it to Sorqoqtani Beki, the mother of Tolui’s sons and thereby one of the aggrieved parties. Sorqoqtani is consistently portrayed in Toluid sources as an extremely wise woman who never wavers from the jasaq nor allows her sons to do so. She claims that this redistribution is well within Ögedei’s rights, as “both the army and ourselves are all the qa’an’s”.Footnote43 The Ögedeids do not always come across very well in our Toluid sources, which may be keen to stress Sorqoqtani’s wisdom in navigating a difficult situation, so let us consider another example in Möngke’s reign. Juvaini, one of Möngke’s eulogists, says that after his accession to power, Möngke revoked all paizas (medallions of authority) and yarlighs (written decrees) from the time of Chinggis Khan, Ögedei and Güyük (). Juvaini portrays this as simply Möngke establishing good governance.Footnote44 Neither Juvaini nor Rashid al-Din mention any opposition to this measure, despite the fact that it would have meant a serious limitation of the princes’ authority. Compare this to Güyük’s accession where Juvaini says that “every yarligh that had been adorned with the royal al-tamgha (red royal seal) should be signed again without reference to the Emperor”.Footnote45 Clearly then, lip service had to be paid to the legacy of Chinggis, but successive qa’ans did have some leeway with regard to individual policy.

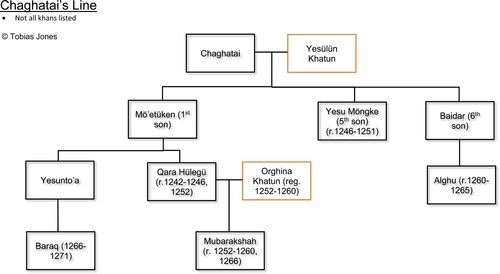

Whatever the case for Chinggis, “remaining loyal” to the other previous qa’ans seems to have been up to the individual qa’an himself. As can be seen, this decision was based on whether or not the qa’an in question wanted to associate himself with one or more of his predecessors. Each qa’an apparently had the choice to confirm the jasaqs of his predecessor or not. Ögedei reaffirmed the decrees of Chinggis, Güyük did the same for those of his father, while Möngke conspicuously did not do so for Güyük’s ordinances.Footnote46 Juvaini’s text shows how similar actions can be portrayed as good in one case and as incorrect in another. Güyük is criticised by Juvaini for installing his close friend Yesu Möngke () as khan of the Chaghataid ulus and removing Qara Hülegü, apparently the choice of both Chaghatai (Chinggis’ second son) and Ögedei.Footnote47 In order to portray Möngke’s justness in returning the khanate to Qara Hülegü upon his own accession, Juvaini claims that Möngke was merely observing the testament of Chinggis, and the desires of both Ögedei and Chaghatai.Footnote48 It is perhaps possible to read into this a clash between Chinggisid practice of filial succession and Mongol custom based on the principle of seniority, as Güyük justifies choosing Yesu Möngke over Qara Hülegü due to Yesu Möngke being a son of Chaghatai and Qara Hülegü only a grandson.Footnote49 Equally, perhaps Güyük was striving to justify his own position, given that he had been elected despite the apparent wishes of Ögedei that his grandson Shiremun would succeed him (). Indeed, when the Toluids took over, they accused Güyük and his supporters of betraying Ögedei’s wishes by ignoring Shiremun’s claim.Footnote50 In later years, the Ögedeid khan Qaidu (d. 1301, ) would claim loyalty to the will of Chinggis and Ögedei, indicating to his Toluid relatives that Chinggis had specifically indicated in his jasaq that succession was to remain in the House of Ögedei and subsequently fighting with his Toluid neighbours to restore the Ögedeid patrimony.Footnote51 In this we see Qaidu’s family loyalty as well as his avowed loyalty to the first great qa’ans, as Qaidu fostered and protected Ögedeid princes who he had enticed away from other khanates.Footnote52

Intricately tied specifically to the legacy of Chinggis Khan, but also to those of his successors, is the thorny concept of the jasaq (Chinggisid law).Footnote53 Much blood was spilled in the Mongol era over what the jasaq entailed, and this debate goes on today, thankfully with the liquid spilled being substituted by ink. Many of the great Mongolists of past and present have tackled this issue without much satisfactory resolution.Footnote54 The central debate revolves around whether or not there was any unified code of laws used by the Mongols and attributable to Chinggis. It is likely that individual jasaqs were noted down during Chinggis’ and his successors’ reign, but that no great law code was established at an early stage of the Mongol Empire. Presumably the existence of such a code would have made ignoring previously issued statutes more difficult. We have already seen that jasaqs had been overturned, and yarlighs and paizas revoked (7). This article will not delve further into this debate but rather consider how the jasaq itself was treated as an object of loyalty. In this manner it functioned as a sort of ideal loyalty by which people in the Mongol world could hold each other to account, and specifically was often used as a shield by those who acted against a member of the Chinggisid house whose power had become overbearing.Footnote55 Of course, the interpretation of the jasaq allowed for many claims of loyalty to it, often in complete opposition to each other. Some examples of this will help clarify the point.

The most notable division in the early Mongol empire was the split which occurred with Möngke’s enthronement. Each side lined up their arguments as to why the other had contravened the jasaq. The Jochids and the Toluids claimed that the Ögedeids’ execution of Chinggis’ daughter Al Altan without consultation of the entire Chinggisid family broke the jasaq and the yosun of the Mongols.Footnote56 Also included in their list of grievances against the Ögedeids is the above-mentioned refusal to act on Ögedei’s desire for Shiremun to succeed him. Given the terminology used, this looks not to have been a specific jasaq.Footnote57 According to Rashid al-Din, it was this breaking of Chinggis’ jasaq and contravention of Ögedei’s wishes which allowed the Toluids to break their vows of fealty to the house of Ögedei.Footnote58 Interestingly, Qubilai, Möngke’s younger brother and later qa’an, in his defence of Möngke’s actions, does not deny the fact that Möngke had pledged his fealty to Güyük after the latter’s enthronement.Footnote59 In this rationale, Chinggis’ jasaq supersedes that of Güyük, despite Möngke’s vows. The Ögedeids naturally had a different version of events. They claimed that Chinggis’ jasaq stipulated that rule of the Mongol Empire should remain in the Ögedeid house in perpetuity, and that Möngke had sworn, in writing, to uphold Güyük’s jasaq reinforcing Chinggis’ words.Footnote60 Juvaini himself acknowledges that it was widely believed that Chinggis had indeed done this, saying that many people wrote letters to Batu (r.1227–1255, ), ruler of the Jochid ulus and Möngke’s main supporter, complaining of Möngke’s selection as qa’an.Footnote61 The Ögedeids and Chaghataids would also soon experience the Toluids’ own contravention of the jasaq requiring a full consultation of the Chinggisid house before executing a member of that house, with Ögedeid princes such as Shiremün and Naqu and Chaghataid princes like Büri and Yesu Möngke () being done away with without trial. Of great importance here is the role of the quriltai, which will be analysed in the next section.

So far we have analysed appeals to the jasaq in the context of a succession struggle, but it was called on frequently in many situations as a justification for action. Berke, the khan of the Jochid ulus from 1257 to 1266 (), wrote in a letter to the Mamluk sultan Baybars (r.1260–1277) that Hülegü, the first Ilkhan (r. c. 1260–1265), had broken Chinggis Khan’s jasaq and this was Berke’s reason for going to war with Hülegü. Berke doubles down on his loyalty obligations, claiming that Hülegü had taken land in the Caucasus that belonged to the Jochids according to Chinggis’ stipulations, but also that he and his brothers fought Hülegü in the name of Islam.Footnote62 Hülegü had, after all, sacked Baghdad in 1258 and killed the last ‘Abbasid caliph, al-Musta’ṣim (r.1242–1258) and his family. Therefore Berke could justifiably say that he was loyal to both Chinggis’ jasaq and Islam in his conflict with his relative. Michael Hope has shown another situation where loyalty to the jasaq was called upon in a dispute. The Ilkhan Geikhatu (r.1291–1295, ) was deposed and executed by a group of commanders who claimed Geikhatu did not follow the jasaq. His nephew and eventual successor Ghazan (r.1295–1304) argued rather that the execution of a Chinggisid khan by non-Chinggisids ran contrary to the jasaq, and as Hope notes, to the yeke törü as explained above.Footnote63 Interestingly, Vaṣṣāf uses the term ta’arruż rasānīdanFootnote64 to describe the reprehensible action of the amirs towards Geikhatu, which can be roughly translated as “to lay one’s hands on”, echoing the sentiments expressed vis-a-vis the rightful lord in the SHM as noted above.Footnote65 Now the “rightful lords” were the Chinggisids, and laying hands on them carried serious penalties.

Loyalty to the jasaq remained a powerful ideal in Mongol khanates, with supposed concessions to Islam being protested in the realms of the Ilkhanate, the Jochid ulus and the Chaghataid khanate. The Persian historian Qāshānī provides us with a well-known protest of Ghazan’s general Qutlugh-Shah that the Mongols in the Ilkhanate were casting away the jasaq in favour of Islam.Footnote66 These protests had more dire consequences in the Jochid ulus, where the khan Özbeg (r.1313–1341, ) put to death those amirs who complained of Özbeg’s betrayal of the jasaq in his adoption of Islam as the religion of the ulus.Footnote67 Michal Biran has shown that while the supposed “first” Muslim khan of the Chaghataid ulus, Tarmashirin (r.1331–1334), was not deposed and executed simply because he was a Muslim; at least some of the sources on his reign, such as the traveller Ibn Battuta, believed it was his abrogation of the jasaq which caused his fall.Footnote68 The dichotomy of the jasaq and the Islamic shari’a would become a significant theme in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries due to the writings of the jurist Ibn Taymiyya who wrote several anti-Mongol fatwas under the Mamluk sultanate specifically targeting the jasaq and thanks to the work of Ibn ‘Arabshāh, whose polemic against the Turco-Mongol conqueror Temür (r.1370–1405) made reference to Temür’s adherence to the jasaq, rendering his Islam false.Footnote69 However, the jasaq and the shari’a often co-existed, so this discourse should not be overstated for the Mongol period; suffice it to say that the jasaq was always available as ideological backing for the actions of princes and noyans in the united Mongol empire and its successor states.

Another object of loyalty, which Juvaini claims was enshrined in the jasaq, was the institution of the quriltai.Footnote70 The quriltai was a consultative, judicial and seemingly legislative body which in imperial times was attended by the Chinggisid family, male and female, and major military and administrative figures in the Mongol world. It seems to have evolved from the congregations of Mongols which elected previous khans such as Ambaqai (), though the consultative assembly has had a long history both in Inner Eurasian society and elsewhere in the world.Footnote71 Given the attendance of many of the key figures of the Mongol Empire, for many this would have been the most representative institution capable of making decisions. Its role is an interesting one in the Mongol world as its legal and administrative resolutions were seen as binding as long as the quriltai itself was widely considered legitimate.Footnote72 Therefore, given the body’s apparent backing by the Chinggisid jasaq, loyalty to the decisions made here could be seen as the ultimate expression of Mongol loyalty. This loyalty to the quriltai seems to have been the centre of an ideological dispute which took place during Möngke’s succession to the empire.

The two issues were thus: Firstly, Batu, the son of Jochi and nominal senior among the Mongol princes in c. 1249 summoned a council in his own lands, at Ala Qamaq, where many, but not all Chinggisid princes and khatuns (royal women) were present.Footnote73 Batu’s reason for the meeting taking place in his lands was allegedly due to an illness. To date, all quriltais had taken place in the valley between the Onon and Kerulen rivers; the Mongols’ ancestral homeland. Batu seemingly only attended a quriltai in Mongolia to elect Ögedei in 1229, but did not turn up for Güyük nor Möngke’s accession, so if this was an excuse, he was at least consistent in its use. At this meeting, the princes successfully chose Möngke as the incumbent qa’an, though it was agreed that they should hold a quriltai in the proper location to officially elect him.Footnote74 Juvaini indicates some of the problems which emerged from this. Neither Güyük’s widow, the regent Oghul Gaimish, nor Güyük’s eldest sons, Khoja and Naqu, would accept the decision to choose Möngke. Indeed, the two key figures behind Möngke’s selection, Batu and Sorqoqtani Beki, pleaded with the Ögedeids to attend the upcoming quriltai to discuss the matter with the aqa and the ini (princes and commanders of the Mongol Empire).Footnote75

Neither does Juvaini use the term quriltai for the meeting at Ala Qamaq, but rather the Turkic term kangāch or other terms.Footnote76 While these terms have a similar meaning, Juvaini elsewhere uses the term quriltai for the assembly which took place in Mongolia in 1251, which may suggest he did not think Batu’s meeting was official. Given that he states, as above, that those present at Ala Qamaq agreed that another quriltai was required, they were fully aware that the decision of this assembly was not enough. The Ögedeids and Chaghataids who did not attend certainly did not believe it fulfilled the requirements of a legally binding quriltai and felt no need to adhere to its decision.

The second ideological standpoint with regards to the quriltai was that taken by the Toluids and Jochids after this event. Firstly, the discussion at Ala Qamaq, even though not given the official title, carried the weight of the joint agreement of the aqa and the ini, and the support of the aqa (most senior prince) of the Mongols, Batu. Representatives of every house were included, though not the most senior Ögedeid and Chaghataid princes or khatuns. This was Batu’s response to those who wrote him complaining of Möngke’s selection; the council had decided and the argument was over.Footnote77 Juvaini claims that those who had attended were shocked by the Ögedeids’ later attempts to counter this decision militarily, saying “none of them dreamt that the yasa of the World Emperor Chingiz Khan could be changed or altered”.Footnote78 Once this “coup” was subdued, the recalcitrant princes were forced to perform obeisance to Möngke before the official quriltai of 1251, giving his accession the semblance of legitimacy. The Yuánshǐ states that Menggeser, Möngke’s yarghuchi (chief judge) decreed it a capital offence to not attend the quriltai or to convene one illegitimately.Footnote79 For those Ögedeids and Chaghataids forced to attend, the situation was lose-lose, as many of them were executed after the quriltai at Möngke or Batu’s orders. The precedent had been set however, and when dissension broke out between Qubilai, Möngke’s eldest surviving brother, and Arigh Böke, the youngest of Tolui’s children, each of them held rival quriltais (). Arigh Böke held his in the appropriate location in Mongolia, and Qubilai in Shàngdū, with neither serving to sort out the succession, which would only be determined through years of war and the break-up of the united Mongol Empire.

Quriltais would continue to be held throughout the Mongol world, so the role of this institution did maintain some degree of significance. In another succession dispute, this time in the Ilkhanate, Ahmad Tegüder (r.1282–1284) complained to his nephew Arghun (r.1284–1291) of Arghun’s attempts to seize the throne, stating that he (Ahmad) had been properly elected and Arghun had not (). Arghun did not however, hold a rival quriltai, but overthrew his uncle and had his accession quriltai once the dirty work was done.Footnote80 However, of the Ilkhans, only Abaqa, Ahmad Tegüder, and Geikhatu were elected after a discussion in the quriltai.Footnote81 Ghazan and other rulers would continue to hold quriltais semi-annually, but they had lost much of their force. A lack of respect for tradition by failing to hold the quriltai was apparently one of the reasons for the overthrow of the Chaghataid khan Tarmashirin Khan in 1334, according to the traveller Ibn Battuta.Footnote82

At least two quriltais were held after the breakup of the Mongol empire that were attended by representatives of several different lines, attempting to once again show some vestige of the united character of Mongol rule and loyalty to Chinggis’ wishes. The first was in 1267, attended by members of three of the Mongol lines; the Jochids, represented by Berkecher, sent by the khan of the Jochid ulus Möngkë Temür (r.1266–1280); the Chaghataids, represented by their khan Baraq (r.1266–1271), and the Ögedeids, represented by Qaidu (, and ). Notably absent of course were the Toluid rulers of China and Iran, Qubilai and Abaqa, whose lands were targeted by the attendees. Michal Biran claims that this was not simply an anti-Toluid pact as there were conflicts between the three rulers represented immediately preceding and succeeding this meeting, but given that those who attended the quriltai agreed to attack Toluid lands and the very fact that the Toluids were not included would surely have been seen as signals of such an alliance from without.Footnote83 According to the Yuánshǐ, the princes sent a letter to Qubilai complaining of his becoming too Chinese, showing a lack of loyalty to Mongol tradition.Footnote84

Several decades later, another quriltai was held, supposedly finally uniting all the Mongol lands once again. In 1304 Öljeitü wrote to King Phillip IV le Bel of France (r.1285–1314), telling him that all parts of the Mongol world had been re-connected through postal stations and that he and his brothers stood behind the Qa’an Temür Öljeitü (r.1294–1307), Qubilai’s successor. Neither agreement nor peace lasted long after these two quriltais, nor were they quite the same affairs as they had been in the 1230s, but they represented a bygone era of unity and loyalty to the traditions of Chinggis and his successors. When showing loyalty to Chinggisid tradition was deemed important for later dynasties, quriltais were often convened. Amir Husayn used one to appoint himself head of the Ulus Chagatai and to appoint a puppet khan in 1364, while Temür convened a great quriltai in Samarqand in 1404, which was extensively described by the envoy Ruy de Clavijo.Footnote85 The symbolic nature of these assemblies was seen as a way of strengthening one’s legitimacy by showing loyalty to Chinggisid tradition and the legacy of Chinggis himself.

One of the instances in which quriltais were convened was to decide upon the succession to the khanate, as we have seen. One person who could convene such an assembly and ran the empire during the time it took to gather those who needed to be present was the regent. While this figure may appear to have limited importance as a sort of placeholder, in fact regents ruled the empire for about 10 years of the 53 year existence of the united Mongol empire (1206–1259) and indeed pursued their own policies and agendas. What is somewhat unclear is whether or not the regents ruled on behalf of the deceased monarch, or on behalf of the future ruler. The uncertainty of Mongol succession and the necessity of a quriltai to determine the next ruler seems to indicate that these people ruled on their predecessor’s behalf. These figures do not always have the best reputation in our sources, in part because most of them were women, who rarely receive praise for their leadership qualities in the Christian or Muslim historical tradition.Footnote86 However, the first regent of the empire seems to have been Tolui, Chinggis’ youngest son (), who ran things between Chinggis’ death and Ögedei’s accession (1227–1229).Footnote87 As regent, Tolui ordered or was party to the sending out of a plundering expedition without general consultation, in contravention of the jasaq.Footnote88 Ögedei’s blanket pardoning of past crimes on his accession in 1229 looks to have cleared Tolui’s name, but the Chinese sources also claim that Tolui wanted to delay the quriltai to choose a successor and only agreed after pressure from one of Chinggis’ respected ministers, Yeh-Lu Ch’u-ts’ai.Footnote89 According to the YS, it was Tolui as regent who was responsible for calling the quriltai, a function which was also performed by at least one other regent, Töregene Khatun. It is to the khatuns in their regency roles that we now turn.

Both Ögedei and Güyük’s regents were their wives, Töregene Khatun (1241–1246) and Oghul Gaimish (1248–1251) respectively (). As Bruno de Nicola has shown, both women had their own policies, often pursuing the election of one of their sons.Footnote90 Perhaps due to the issues which may have arisen during Tolui’s regency, sons of the former ruler no longer became the regents. This may have been in order to restrict them from seizing the entire resources of the empire and establishing themselves militarily without recourse to a quriltai.Footnote91 Töregene became regent in a sort of postal vote quriltai, whereby she sent letters to Chaghatai, the aqa, and the other princes requesting this role, outmanoeuvring another of Ögedei’s widows who thought to have assumed the role, Möge Khatun.Footnote92 She therefore earned loyalty by gaining the support of the key princes in the empire, as well as through the judicious use of gifts. It was Töregene who convened the quriltai which eventually selected her eldest son, Güyük, though Töregene largely held on to power until her death. Things changed somewhat with the regency of Oghul Gaimish. She was confirmed in her position as regent by Batu, by this point the aqa of the Mongols. However, it was Batu and not Oghul Gaimish who convened the quriltai to choose a successor. While it is often noted that Batu’s quriltai was illegitimate for its location and lack of key attendees, there may also be a procedural issue here. Batu was not the regent, and heretofore the convocation of a quriltai had been in the remit of these regents. However, Oghul Gaimish may have been delaying calling a quriltai due to the dissension between two of her own sons, Khoja and Naqu, and with Shiremün, Ögedei’s grandson and chosen heir.Footnote93

Loyalty to these figures was both weaker and more precarious than to the khans themselves. As the regents themselves did not have the backing of an election through the process of a quriltai, there was greater scope for action against their will. Töregene Khatun deposed two of Ögedei’s most influential officials, Chinqai and Maḥmūd Yalavāch, but was thwarted by her own son Köten, who gave them refuge and refused to hand them over.Footnote94 According to Juvaini, after both Güyük and Möngke’s accessions, the qa’ans had to recall the great deal of paizas and yarlighs which had been issued by numerous princes during Töregene and Oghul Gaimish’s rule.Footnote95 We must be wary of course of the sources’ tendency to exaggerate, but the actions of the qa’ans who succeeded these regents do tend to suggest that there was a stronger reaction to “abuses of power” when they were perpetrated by women.Footnote96 While Güyük did not harm his mother after taking power, her closest advisor, Fatima, seemed to take the full brunt of Mongol anger at some of Töregene’s policies, which included dispensing with long serving officials such as Chinqai. Fatima’s torture and brutal execution are described all too vividly by Juvaini and Rashid al-Din.Footnote97 Chinqai, who had served Chinggis, Ögedei, Güyük and Oghul Gaimish, was executed at the age of 83 by Möngke in 1252. Oghul Gaimish herself, and Shiremün’s mother Qadaqach were tried for witchcraft and executed after their sons opposed Möngke’s succession.Footnote98 Loyalty to a regent therefore could be extremely dangerous, even if the regent’s own choice for a successor was confirmed by the quriltai, such as Töregene’s manoeuvring on behalf of her son Güyük.

Another figure whose importance seemed to grow when a qa’an had not yet been chosen was the aqa. While this title was often added to personal names as a sign of respect, such as with the famous administrator Arghun Aqa, its technical meaning was “older brother”, and was nominally applied to the eldest Chinggisid descendant. Unfortunately this very clear cut definition does not stand up to an analysis of the sources, whose political leanings also muddy up the water. The only character who is consistently referred to as the aqa of the princes is Jochi’s son Batu. Both Juvaini and Rashid al-Din declare Batu as the eldest of the princes, though both patently state that Jochi had an older son, Orda (), who willingly stepped aside for Batu to succeed Jochi as khan of the Jochid ulus.Footnote99 Orda and his descendants continued to rule their own ulus to the east, eventually called the White Horde, and while theoretically under Batu and his descendants’ rule, they had their own khans who did not pay homage to Batu’s descendants.Footnote100 Beyond this discrepancy, it was Batu’s status as aqa which apparently conveyed the necessary weight to achieve Möngke’s succession in 1251, and both historians, as officials of Toluid regimes, were keen to stress this role’s importance.

Batu was arguably the key figure in the Mongol world in the 1240s and early 1250s and many of our sources, Persian, Armenian and Latin, attribute great power to him. It was with the death of Güyük and the transition of power from the house of Ögedei to the house of Tolui that Batu exerted his considerable influence. Rashid al-Din claimed that it was Batu’s inability to attend (due to illness) which delayed the quriltai to elect Güyük until 1246, 5 years after Ögedei’s death.Footnote101 However, the fact that the quriltai was in fact held, without Batu’s presence, but with plenty of Jochid representation, including Orda and Batu’s eventual successor Berke, this point seems overstated by Rashid al-Din. In the interregnum which followed Güyük’s death in 1248, Batu confirmed Güyük’s widow Oghul Gaimish as regent, just as Chaghatai had done previously for Töregene. Batu’s subsequent actions, however, would undermine the authority of the regent. If precedent was important, Tolui and Töregene, the two previous regents, had called the quriltais to elect Ögedei and Güyük respectively. But Batu not only called an assembly to discuss the succession himself, but also decided that it should come to him on account of his illness (possibly gout). Chaghatai, the great observer of the jasaq and technical aqa after Ögedei’s death, did not take these actions. Rashid al-Din claimed that Chaghatai died several months before Ögedei.Footnote102 Perhaps this is merely a mistake by Rashid al-Din, but doing away with Chaghatai does accomplish several things if we suspect the historian of a more elaborate historical plot to weaken Ögedeid legitimacy. Unlike Juvaini, who states that Töregene became the regent based on Chaghatai’s confirmation as well as other princes, Rashid al-Din claims that Töregene seized control of the khanate using trickery and without consulting the aqa and ini.Footnote103 Thus Töregene’s regency is called into question, and therefore also the quriltai which she summoned to elect Güyük, without the presence of Batu, the aqa.

Batu’s assembly at Ala Qamaq has already been discussed, but an important dimension of this meeting was the language used by Juvaini, and Rashid al-Din following him, to describe the authority of the aqa. According to Juvaini, Batu is the aqa and “whatever he commands, his word is law”.Footnote104 Rashid al-Din says the princes stated “Batu is the elder of all the princes, […] and we are subject to his command. We will in no way go against what he considers proper.”Footnote105 They indicate that the princes in fact gave written pledges, called möchalgas by Rashid al-Din, to obey the command of Batu. Batu had decided that Töregene’s selection of Güyük contravened Ögedei’s order that Shiremun should succeed him and therefore the Ögedeids should no longer be in full control of the succession. Instead, Möngke, eldest son of Tolui and the very wise Sorqoqtani Beki, who knew the jasaq well and never swerved from it, had the right to the khanate.Footnote106 While the princes in attendance seemingly accepted Batu’s directive to choose Möngke as the next qa’an, the fact that this “assembly”, majma’, was of a quite questionable nature due to the absence of important attendees and its location, meant that it functioned as a sort of primary before the true quriltai took place.Footnote107

However, Batu and Sorqoqtani Beki, the other figure who worked tirelessly to achieve Möngke’s election, now treated this decision as a fait accompli, due to its backing by the aqa and the fact that they could now claim that it was done in consultation with the aqa and ini of the Mongol Empire. Batu and Möngke had been able to entice certain members of the Ögedeid and Chaghataid houses with grievances against their own houses to break ranks and lend to Möngke the nominal backing of their lines. At this point, the Jochids and Toluids indicated to their recalcitrant relatives that their loyalty obligations were to the aqa and the assembly, using multiple tactics to try and force the Ögedeid and Chaghataid princes and their supporters to attend the upcoming quriltai. Juvaini claimed that both Batu and Sorqoqtani wrote to their kinsmen using a mixture of enticements and threats, but he also indicates that at other times they tried to persuade the other princes that there would in fact be a proper discussion about the succession with all the aqa and ini if only they would come to the quriltai.Footnote108 These mixed messages cannot but have confused the princes, and made them extremely wary. Their failed attempt to resist the Toluid coup could hardly have surprised the Jochid-Toluid party, who as we have seen (p. 13) claimed their shock as to the “alteration” of the jasaq of Chinggis.Footnote109 What specific jasaq of Chinggis they are referring to is not made clear by either Juvaini or Rashid al-Din, but given that they both follow the account of the struggle with a famous anecdote of Chinggis’ calling for unity between his sons, perhaps they meant some general admonition against infighting. The hypocrisy of the Toluid-Jochid claims was pointed out by the regent, Oghul Gaimish, who wrote to Möngke telling him that he had attended Güyük’s coronation and given his written word that he would choose a successor from Ögedei’s line, in fact a jasaq of Chinggis, Ögedei and Güyük’s. For having the temerity to point this out, Oghul Gaimish was tortured, put on trial while naked by Möngke’s jarghuchi (chief judge) Mengeser Noyan, wrapped in felt and cast into a river.Footnote110

Beyond ideological differences between the two sides, there seems also to have been some confusion for the Mongols as to which loyalty object demanded one’s obligations in a time of interregnum, the aqa or the regent. For comparison, perhaps we should turn to the previous possible holder of the title aqa, Chinggis’ second son Chaghatai. Chaghatai’s status as the oldest Chinggisid came about in 1227 when both his older brother Jochi and Chinggis himself died. Chaghatai was apparently significantly involved in achieving Ögedei’s accession. As we have seen in the YS, there may have been some disagreement over succession between Tolui and Ögedei, and Rashid al-Din also seems to allude to this, saying that only Chaghatai was friendly with both brothers, perhaps acting as a mediator, though he was adamant that they elect Ögedei according to his father’s wishes.Footnote111 In a more ceremonial sense, Chaghatai was physically involved in Ögedei’s accession, holding his right hand, while Tolui held his left, and Chinggis’ younger brother Temüge Otchigin took Ögedei by the belt.Footnote112 At Güyük’s coronation, the two who raised him to the throne were Yesu Möngke, Chaghatai’s eldest legitimate son, and Orda, the elder brother of Batu. While this may have been a necessity for Güyük given Batu’s absence from his quriltai, it may simply have been a statement of fact that Orda was in fact the aqa by this point.Footnote113

Beyond this ritual position, the role of aqa seems to have been largely advisory. The SH claims that in his role Chaghatai mainly functioned as the preeminent advisor to Ögedei during his reign, with Ögedei seeking his support and backing for key measures such as the creation of the yam (postal) system.Footnote114 However, there was at least one major disagreement between the two recorded by Rashid al-Din. Chaghatai reallocated lands in his ulus in Transoxiana which Ögedei had decreed were crown lands. Ögedei’s representative in the region, Mahmud Yalavach, reported this to Ögedei. Chaghatai wrote an apology to Ögedei, but was in fact granted the region in perpetuity, while Yalavach was berated by Chaghatai and reappointed to administer northern China by Ögedei.Footnote115 In the confrontation between qa’an and aqa, formalities were observed but it was the qa’an who backed down to his elder brother.

Chaghatai’s status as eldest prince became even more important after Ögedei’s death, however. According to Juvaini, people began to flock to Chaghatai’s court to pay him homage, seemingly in expectation that he would become the next qa’an, though his death not long after Ögedei precluded such a development.Footnote116 It may have been for this reason that Töregene Khatun was especially keen to get Chaghatai’s support for her regency. As far as we can tell from our sources, Chaghatai was content with Töregene as regent, and if he was planning to succeed, never got as far as convening a quriltai, if indeed this was within his purview. In sum, we do not have enough information as to the position of aqa to say with any great clarity what authority it entailed and what duties were expected, beyond the ceremonial aspect.Footnote117 It seems however, that Batu capitalised on Mongol respect for seniority and the divisions among the Ögedeid house to play the kingmaker, accentuating the loyalty obligations of the Mongols to their aqa, as opposed to the regent and the house of Ögedei.

Regional Loyalties

Now we move on to a group of characters who were objects of loyalty at a regional level. In this sense, they themselves had loyalty obligations to those people and institutions above them, those listed in the previous section. However, these more regional loyalties could and often did challenge the authority of figures at the heart of the empire, which could cause major issues given their ability to co-opt those below them and drain manpower and resources away from the empire. The most significant regional power was the khan/khatun of the ulus. During his lifetime, Chinggis had parcelled out both lands and peoples to his relatives as their emchu (in Persian sources īnjū), or private property. Sons, brothers, nephews, wives and daughters all got varying shares which were theirs and their descendants in perpetuity. Ideally, all of these characters would subordinate themselves to the qa’an in cases such as taxation and military affairs, but even with his immediate successor Ögedei, problems emerged between the central authority and the regional khans. The above-mentioned dispute between Ögedei and Chaghatai as to lands within Chaghatai’s ulus went the way of the regional khan. In his dealings with the khatun of Tolui’s ulus, Sorqoqtani Beki, Ögedei had mixed success. We have seen that he was able to transfer several thousand troops from her ulus to that of his son Koten, but Sorqoqtani ignored his yarligh ordering her to remarry Ögedei’s eldest son Güyük, which would have significantly strengthened the Ögedeid house.Footnote118 Ögedei and Batu also seemed to have waged something of a phony war in Mongol territories in the Middle East and the Caucasus, where officials from both competed to tax the settled population and to oust one another from power.Footnote119 These officials had to tread a fine line between Batu as the regional power, and the qa’an in Qara Qorum. Arghun Aqa for example, reported both to Batu and to the qa’an.Footnote120

The struggles between qa’an and khan of the ulus were often played out with regards to succession of the various ulusut. The qa’ans often tried to get their own man (or woman) as head of the ulus to guarantee that region’s cooperation. However, it seems unclear whether or not this was the prerogative of the qa’an or if this was to have been decided by the previous regional khan, or even by a quriltai.Footnote121 When both the qa’an and the regional khan agreed on their successor, clearly there was no issue. Juvaini claims that Chaghatai, khan of the Chaghataid ulus, and the ruling qa’an Ögedei (as well as Chinggis himself), agreed that Chaghatai’s grandson Qara Hülegü () would succeed him.Footnote122 Apparently, there was also agreement between Batu of the Jochid ulus and Möngke qa’an that Batu’s son Sartaq () should succeed him.Footnote123 However, once power struggles began, the qa’ans began to intervene more regularly. Güyük, in contravention of the wishes of Ögedei and Chaghatai, replaced Qara Hülegü with Chaghatai’s son Yesu Möngke, Güyük’s friend and ally, on the basis of seniority, Qara Hülegü only being a grandson. The disenfranchised Qara Hülegü naturally sided with Möngke in his struggle with the Ögedeids, and was rewarded for his loyalty by being restored to the rule of the ulus. Möngke assigned him to execute Yesu Möngke, though he died en route. Möngke then entrusted this task to Qara Hülegü’s widow, Orghina Khatun, and put the rule in the hands of her infant son Mubarakshah.Footnote124

Though the Mongols regularly stated they would not follow a child, Möngke ignored these customs yet again in the Jochid ulus, installing the young son of Sartaq, Ulagchi, with Batu’s wife Boraqchin Khatun as his regent.Footnote125 Ulagchi also died quickly after, and Batu’s younger brother Berke became the successor. We do not have any information about how this took place, though both Stefan Kamola and Anne Broadbridge have claimed that this was against Möngke’s wishes and a usurpation of Sartaq’s line respectively.Footnote126 However, at least according to Rashid al-Din, Berke’s involvement in Möngke’s coronation and further support led to a close working relationship in which Berke was superior to Möngke’s brother Hülegü. Even after he succeeded, the historian claims that Berke maintained overall good relations with the Toluids, at least until the suspicious deaths of Berke’s relatives who had accompanied Hülegü’s campaign to the west.Footnote127

The purge of the Ögedeid and Chaghataid houses by Möngke after his succession meant that the princes who remained were Toluid lackeys, at least for a time. During the succession struggle between Ariq Böke and Qubilai (1260–1264), the contenders vied for control of the Chaghataid ulus via puppet khans. This Toluid overbearance within the Chaghataid ulus and among the Ögedeid princes was cast off by those such as the Ögedeid khan Qaidu and the Chaghataid khan Du’a ( and ), who reasserted both the territorial claims of their houses and their own status within the Chinggisid house.Footnote128

Berke also had cause to resent the Toluids. His loyalty and support in Möngke’s succession was hardly appreciated by Hülegü, Möngke’s younger brother and commander in the western campaign, who executed his relatives and took control of lands that the Jochids felt were their own. Berke waited until Möngke’s death to act on these slights, eventually attacking Hülegü in 1262. By this point, Hülegü’s two brothers Qubilai and Ariq Böke were fighting for control of the khanate and Berke did not commit to either. Berke had presumably lost patience with his Toluid suzerains, who had allowed his family members to be killed and his lands to be taken without redress. His lack of support for the eventual qa’an Qubilai and his longstanding conflict with Hülegü saw the Jochid ulus exert its independence. Loyalties for troops who had served in the western campaign came down to individual lineage, not the faraway qa’an; therefore Jochid troops who had been stranded in what came to be the Ilkhanate either fled to their own territories, or went to support the Ilkhans’ other enemies, the Mamluks of Egypt. The system of hereditary control of troops meant loyalty bonds which were formed closer to home, not to a qa’an in Daidu. Once the regional khan saw no obligation to be loyal to the qa’an, the ulusut became their own entities, too powerful to be brought back into line by the ruler in Daidu.Footnote129

The next set of characters in our cast are the garrison commander (tammachi), military governor and darughachi.Footnote130 I will treat these roles jointly in order to deal with the often confusing nature of the three, with at times overlapping duties. This administrative web was not helped by the Mongol rulers, who at times doubled up on these positions, making things even less clear to those who owed their loyalty to these more regional figures. While this seems like a bureaucratic nightmare bound to lead to conflicts (which indeed it did), it certainly helped to limit the powers of officials and commanders who had significant freedom in areas not yet fully under Mongol control. What is also noticeable is the Mongols’ flexibility according to different situations. Both geographically and temporally, the Mongols adapted their administrative apparatuses according to need. At times all three roles seemed to function side by side, while in other areas of their empire such as Rus’, only the basqaq was in operation. In certain vassal states, even these figures seem to have been dispensed with, the local ruler being allowed to operate on his own as long as he fulfilled Mongol demands.

The first of these roles was the garrison commander, or tammachi. He was the head of the tamma troops, who were sent into a region to pacify it and further extend Mongol conquests, living in those lands and passing on their positions to their children. This was usually a large army; Chormaghun when sent to the regions of the Caucasus and Azerbaijan was accompanied by 4 tumens (units of 10,000 men), while Muqali in Chin lands had similar numbers.Footnote131 This role functioned in areas not within the ulusut, which were not completely subdued.Footnote132 It seems that primarily the commander had military duties, subduing such groups that were not yet in submission to the Mongols. Therefore, the noyan Chormaghun was appointed by Ögedei after Chinggis’ death to end Jalāl al-Dīn Khwārazmshāh’s resistance to the Mongols.Footnote133 Similarly, his successor Baiju was sent into Anatolia to achieve the submission of the rump Seljuk state there in the 1240s.Footnote134 In this role, they were the representatives of the qa’an, and dominant in the area they were assigned to. Those rulers who operated in the area subordinated themselves to these commanders in order to show their loyalty to the qa’an, though they still were usually made to submit in person to the qa’an. However, these figures’ authority went beyond solely the military sphere, and as quite often in the Mongol world, both military and administrative duties were expected of those holding positions of power. According to Armenian sources, these commanders had great freedom in action, allowed to convene quriltais, take censuses, give their seal of approval to merchants, appoint their own commanders and accept delegations from conquered populations.Footnote135 Rashid al-Din also states that they appointed their own shiḥnas in conquered territory.Footnote136

Apparently this freedom of action for the garrison commanders got out of hand. Juvaini claims that areas such as Azerbaijan and Tabriz suffered from the depredations of Baiju and Chormaghun.Footnote137 As the empire grew, the frontiers were pushed outwards and lands within Mongol control were put in the care of the military governors, who took over some of the duties of the garrison commanders, though the governors were still nominally subordinate to these commanders. Thomas Allsen pointed out that three “branch secretariats”, or xingsheng as they had been called in China, existed in northern China, Turkestan and Khurasan.Footnote138

For our case study we will look at Khurasan, which had previously been under the control of Chormaghun. One of the shiḥnas/basqaqs who had supported Chormaghun’s campaigns in the early 1230s was Chin Temür, who had been appointed to this role in Khwarazm by Jochi. In dealing with rebels neglected by Chormaghun, Chin Temür took over the administration of Khurasan, apparently without the approval of either Chormaghun or Ögedei. Ögedei had in fact sent another noyan, Tayir Bahadur, to pacify Khurasan, but Chin Temür rejected his takeover, instead sending messengers to Ögedei reporting on his own actions. Perhaps this alone would not have convinced the qa’an, but significantly, he also sent several amirs from Khurasan who had surrendered to him to pay obeisance to Ögedei. This delighted the qa’an, who had been apparently frustrated by Chormaghun’s failure to send any rulers to him. Chin Temür was rewarded with a paiza and al-tamgha confirming him in the governorship of Khurasan and Mazandaran. Ögedei ordered Chormaghun to relinquish control of the area. However, Chin Temür did not have it all his own way, with Ögedei appointing an amir of his own household, Kulbolad, as a partner to Chin Temür.Footnote139 A baffling situation, doubtless, and Ögedei did nothing to ease the situation, sending further new governors before the sitting governor had died or was removed, leading to often violent confrontations. Chormaghun and his amirs also pushed back, often refusing to hand over lands which Ögedei had decreed would be administered by the governor.Footnote140

We may look on this administrative nightmare with frustration, but these tactics seem to have been a mode of ensuring loyalty to the qa’an at the centre of the empire. Officials and noyans could not get any delusions of grandeur despite being far from imperial control, while they were often forced to return to Qara Qorum to plead their case or have the qa’an reaffirm their positions. This seems to have been the status quo under Ögedei, but things changed under the regency of Töregene Khatun and the appointment of Arghun Aqa to the governorship of Khurasan. Perhaps due to her own weaker position as regent, Töregene did not appoint anyone to “partner” Arghun Aqa and it was under Arghun that the power of the governor reached its zenith. Arghun was able to maintain control despite the changes in power in the imperial centre, and in fact his remit was increased to include all of Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Anatolia and the Caucasus.Footnote141 Both Güyük and Möngke had also entrusted Arghun with the collection of the yarlighs and paizas issued by the princes and khatuns during the interregna and the reigns of their predecessors.Footnote142 Arghun Aqa was responsible for taking censuses, collecting taxes, requisitioning the army and leading troops against rebellious territories. This naturally signalled a more marginal role for garrison commanders such as Eljigitei (Güyük’s replacement for Baiju) and Baiju. Their freedom was yet further curtailed by the arrival of Hülegü.

Once Möngke appointed Hülegü to command the armies of the west, he ordered that the troops which had until that point followed Baiju and Chormaghun be reassigned to Hülegü’s command. According to Rashid al-Din, it was Baiju’s overweening pride in his power that saw him executed by Hülegü.Footnote143 Nonetheless, it was to these military/administrative officials that many in the Islamic and Caucasian world owed their loyalties, given that they were the highest representatives of Mongol power in the area for the better part of 30 years. It was only with the coming of Hülegü in the late 1250s that a member of the Chinggisid house exerted direct control over the Mongol forces in the west. For the troops who had fought in these garrisons, their loyalties were much closer to those they served with and lived with, so it should come as no surprise that many of these groups did not accept Hülegü’s suzerainty and stuck with their local leaders.

The most famous of the rebel bands who did not accept the suzerainty of the Chinggisid khans were the Qara’unas troops, who became mercenaries-cum-bandits in the late thirteenth century based in the areas of Ghor and Ghaznin.Footnote144 This group, or rather collection of groups, had its origins in a garrison force sent by Möngke Qa’an to the regions of Badakhshan, Qunduz and the frontiers of Hindustan before Hülegü’s arrival. The force was later put under the command of a Tatar amir named Sali Noyan, who was sent out as a branch of Hülegü’s army. At first there seem to have been no problems, with Sali campaigning and apparently sending many Indian slaves to Hülegü. However, by the reign of Ghazan, one of Sali’s grandsons, Begtut, was commanding a Qara’unas troop in Khurasan, by which time the Qara’unas had long been independent of Ilkhanid control, often conducting raids on the realm.Footnote145 Our sources do not provide a clear picture as to why the Qara’unas served Hülegü loyally under Sali but were considered rebellious by Abaqa; but as Peter Jackson has noted, this issue became mixed up in the conflict with the Negüderis, another group which followed its commander rather than its khan.Footnote146 Negüder, according to Rashid al-Din, led a large group of Jochid troops, who had formed a part of Hülegü’s army, into exile in a similar region as the Qara’unas once Hülegü turned on the Jochid elements within his forces. Information about the character of Negüder is very sparse, with Marco Polo and Rashid al-Din’s main translator, Wheeler Thackston, erroneously associating him with a Chaghataid prince of the same name.Footnote147 Whatever the case may be, his followers were labelled with his name and were often lumped together with the Qara’unas; understandable given their similar location, aims and joint actions. It may have been under the influence of the Negüderis that the Qara’unas became an independent group, but one cannot ignore that the absence of a recognised qa’an presumably also played its part. Both groups at times served the Ilkhanids, at times the Chaghataids, while also acting as raiders and pillagers of their own volition.

These were not isolated incidents of tamma troops acting independently. Jackson has pointed out that there were others operating within the Ilkhanate, including the Jurma’is of Fars and Kirman, and the Ughanis of Kirman. Jurma had been a military official and Ughan was a Jalayir commander of a 1,000. These groups became “quasi-tribes” based on hereditary descent. In the decimal breakdown of the Mongol military, loyalties were the strongest to those officers closest to the troops. John of Plano Carpini and Juvaini both indicated the enforced unity through collective punishment of groups of 10 or 100 and punishment of disobeying one’s unit commander.Footnote148 Add to this the decades of living alongside the same troops and intermarrying with them over time and one can see the ties that bind. For the leaders of 1,000 or 10,000, the absence of a recognised great qa’an and the internecine warfare between Chinggisids seemed to erode their sense of loyalty to the Altan Urugh (golden lineage, referring to the Chinggisids). Qubilai apparently saw the possibilities for disloyalty through the rootedness of troops in such a system, and Marco Polo states that he shuffled his garrison troops to different regions every two years, as well as changing their commanders. This, combined with apparently good wages for the soldiers, helped the qa’an to ensure their loyalty.Footnote149

An interesting incident noted by Rashid al-Din occurred in 1290 can perhaps help us here. A group of Qara’unas under one Aladu Noyan had been in service to Amir Nawruz in Khurasan. They turned on their master, sacking Nawruz’s tent and making off with the goods. They then deserted their own commander Aladu, breaking off into different groups. Aladu then submitted himself to Prince Ghazan, who gave him lands and showed him favour. Later that year, several groups of Qara’unas were making trouble in the regions of Juvayn and Merv, so Ghazan sent the self-same Aladu to try to pacify these groups.Footnote150 Our author does not provide us a fitting end to the tale, and the Qara’unas continued to make trouble in Khurasan for the duration of the Ilkhanate; but what is notable here is that Ghazan could think of no better person to deal with the Qara’unas than one of their own commanders, hoping that their personal loyalty to him would sway the troops into submitting to Ghazan. These groups would also provide refuge and support to rebellious Ilkhanid princes and amirs such as Kingshü and Nawruz, proving a constant thorn in the side of the state that in fact outlasted the Ilkhanate itself. Loyalties in the Mongol world had clearly fractured far beyond the classical four khanates idea.

The final “Mongol” object of loyalty at the regional level was the darughachi.Footnote151 It was they who formed the link between the Mongol Empire itself and the submissive local rulers. This system was seemingly adapted from the Qara Khitai of Central Asia, who often ruled quite loosely over their territories, relying on local rulers complemented by these officials (called shiḥnas during Qara Khitai rule).Footnote152 These men were stationed in cities or provinces as a kind of colonial viceroy. It was to them that local officials reported and paid their taxes to. They often had a military presence to enforce Mongol rule as well.Footnote153 In certain parts of the Mongol Empire, such as the Rus’ principalities or Uighuristan, these figures were the only Mongol representatives present among the local population. Otherwise, paying tribute and delivering levies was the responsibility of the Rus’ princes or the Uighur idiqut (ruler). We have evidence of such figures in areas such as Rus’, Armenia, Iran, Central Asia, Korea and Northern China, in greater or lesser numbers, and they were largely maintained in the successor khanates.Footnote154