ABSTRACT

Drawing on the Core State Power framework, this paper assesses Germany’s ambiguous role in EU asylum policies from signing of the Maastricht Treaty to the present. It demonstrates that Germany has neither taken on the role of a leader nor pursued any consistent course regarding the institutional setup or content of EU asylum policies. However, this does not mean that Germany does not have any preferences in this area. Overall, German governments have supported whatever policy would decrease the country’s share of asylum-seekers vis-à-vis other European countries, in order to achieve two core goals: first, to avoid the material costs resulting from high numbers of asylum-seekers, a preference that is common among state elites; and second, to avoid audience/electoral costs resulting from the comparatively restrictive preferences of the public, especially when these are mobilised by right-wing populist parties.

Introduction

During the so-called ‘European refugee crisis’ of 2015, Germany played a unique role. On 31 August, German chancellor Angela Merkel suspended the Dublin Regulation for refugees coming to Germany from other member states (Der Spiegel, Citation2016) with a view to alleviating pressure on overburdened border countries and Hungary. While the Visegrad countries later criticised Merkel for having invited more asylum-seekers to Europe with her ‘open borders approach’ (Euobserver, Citation2015), the German chancellor was also internationally recognised as the person of the year by Time magazine and hailed as the ‘chancellor of the free world’ and the ‘de facto leader of the continent’ (Time, Citation2015). It remains a bone of contention whether Merkel’s behaviour was due to a misunderstanding caused by a tweet sent by the Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) on 25 August 2015 saying, ‘We are at present largely no longer enforcing Dublin procedures for Syrian citizens’ (BAMF, Citation2015) or to a desire to preserve European unity by alleviating the pressure on border countries (Thielemann Citation2018). Much more interesting is the fact that as soon as Merkel encountered a backlash in public opinion and faced possible electoral defeats, she made a U-turn in her policy, adopting a more restrictive approach towards asylum-seekers (Financial Times, Citation2017).

We argue that this inconsistent behaviour is in line with Germany’s long-term approach to EU asylum policymaking, which has been anything but consistent. Over almost three decades, Germany has only promoted European integration when it served its own interests. When there was nothing to gain for Germany, it even blocked further integration and policy change. We show that this can explain why Germany has not been considered a credible leader, neither during the 2015 crisis response nor during the current reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). While Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs, this issue, state that German governments have consistently preferred regulation over costly supranational capacity-building, we argue that, on the issue of asylum, Germany has been more interested in the content of policies than in the form of integration. German governments on both the right and the left of the political spectrum have supported more or less integration depending on whether building capacities at the EU level would help Germany keep the number of asylum-seekers low. This has been due to the high electoral costs attached to migration policies, especially when mainstream political parties face competition from far-right challengers. The politicisation of migration at the domestic level explains why the substance of policies in this area was more important for German governments than taking a consistent approach towards the integration of asylum policies at the EU level.

We consider EU asylum policies a ‘critical case’ (Yin Citation2018, 49) to test the Core State Power framework proposed by this special issue, since the state’s prerogative to decide on the entry and stay of non-citizens is closely linked to the concept of national sovereignty. In order to test the hypotheses set out in the introduction (Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs Citation2021), we base our case study on a qualitative content analysis (Schreier Citation2012) of original interviews with policymakers from the EU institutions, press articles and other documents, as well as secondary data. More information on the original data can be found in the online methodological annex.

In the first section, we consider why asylum policies can be considered a core state power. We then develop expectations on the origins of governmental preferences following the framework proposed by Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs, considering both the role of state elites, mass publics and political parties in formulating preferences, and go on to explain the preferences and positions of different German governments over time. Finally, we analyse Germany’s positions on EU decision-making procedures and substantive policy changes.

The form and extent of integration in EU asylum policies: supranational control of national capacities with limitations

Asylum policies are a clear example of a core state power. The capacity to decide on whether someone can benefit from the protection of another state is intimately linked to that state’s capacity to control who enters and stays in its territory. Moreover, the right to grant asylum also includes the power to grant fundamental and social rights. Therefore, it is not surprising that member states have been reluctant to give up their substantive sovereignty over asylum decisions and have tried to maintain these capacities at the national level. At the same time, the emergence of the Schengen area created new externalities that pushed for cooperation at the EU level. The removal of internal border controls generated concerns among member states, since they thought that asylum-seekers might abuse the system and lodge applications in several countries. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia leading to a surge in the number of asylum-seekers, the need for cooperation became more pressing. As a result, member states agreed to shift regulatory competences to the EU level as a way to ‘compensate’ for the potential negative effects of Schengen (Guild Citation2006; Lavenex Citation2001; Niemann Citation2006). In order to avoid potential secondary movements and ‘asylum shopping’, member states created a new system, whereby those that let asylum-seekers into their territory first would be responsible for them (Dublin Convention). In addition, secondary movements were also to be avoided by establishing common standards across the Schengen area: if all member states offered the same conditions and opportunities, there would be fewer incentives for asylum-seekers to move from one state to another (Thielemann and Armstrong Citation2013). This logic triggered the emergence of the CEAS, which created a set of rules covering: who qualifies as a refugee (Qualification Directive), what kind of reception should be offered to asylum-seekers (Reception Conditions Directive), and what procedures guide the determination process (Asylum Procedures Directive). Thus, the CEAS responded to the need to prevent potential externalities derived from Schengen and to create credible commitments to be supervised by supranational authorities (the European Commission and, eventually, the EU Court of Justice).

In principle, this policy area fits the ideal-type defining ‘supranational control of national capacities’ (see Table 1 in the introduction to the special issue; (Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs Citation2021)): Member states decided not to upload their substantive capacities in the area of asylum (i.e. deciding who qualifies as a beneficiary of international protection and where they should reside), but gave supranational actors the regulatory tools to supervise member states and ensure that they were working towards a common goal (namely, preventing secondary movements and ‘asylum-shopping’). As foreseen by Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs, this mixed mode of integration has led to a system that is unstable and unsustainable. By not uploading the capacity to decide on who deserves international protection and how to share responsibility among member states (i.e. redistributing risk), the CEAS has faced serious limitations, and contributed largely to the Schengen crisis of 2015–2016 and the unilateral border closures.

There are two main reasons why the design of the CEAS led to substantial gaps in its implementation. First, the CEAS did not emerge in an empty policy space; in the status-quo ante, the capacities of member states in relation to asylum were widely different. While Northern member states had already developed strong regulatory systems in order to respond to high numbers of asylum-seekers, Southern member states had been traditionally emigration countries and generally lacked any administrative and regulatory capacity in the area of asylum. Therefore, Northern member states used the process of EU harmonisation to upload their regulatory standards and avoid extensive implementation costs. In comparison, Southern member states had to catch up or, in many cases, develop asylum systems from scratch without the necessary administrative and budgetary means (Zaun Citation2017). As a result, the pre-existing inequalities in member states’ capacities led to large gaps in the implementation of the CEAS, which meant that, depending on where they landed, asylum-seekers faced an ‘asylum lottery’ – i.e. a very different chance of gaining asylum under extremely unequal material and procedural conditions (ECRE, Citation2012). Second, asylum cooperation has been said to follow suasion game dynamics (Betts Citation2003). This means that those who benefit from the status quo (i.e. those with lower numbers of asylum-seekers) can act as veto players and prevent any changes in the system. In contrast, those who are hosting many asylum-seekers will find it more difficult to shift their responsibility to other member states due to international norms (e.g. the Geneva Convention) and the unwillingness of non-hosts to accept more asylum-seekers in their territory (Zaun Citation2019).

As for the level and extent of integration, EU asylum policies have evolved significantly, from intergovernmental coordination outside the EU treaties to joint decision-making under the ordinary legislative procedure (Ripoll Servent and Zaun Citation2020). This policy area can, therefore, be considered fully supranationalised formally; informally, we have witnessed a dominant bias towards the Council in decision-making. First, member states set the core of this policy area during its initial stage (1990s, early 2000s), which makes it difficult even now for supranational institutions to move away from the status quo. Second, asylum has become increasingly politicised at the domestic level, which has led to more ideological contestation inside the European Parliament and even on the Commission. Politicisation has also empowered the European Council, to the point where there can be no reform of the CEAS without its consent (Ripoll Servent Citation2019; Ripoll Servent and Trauner Citation2015). This informal prevalence of member states’ voices underlines the weaknesses of integration in a CSP area, and makes it all the more important to understand the role played by a central country like Germany in asylum decision-making.

Therefore, in the case of EU asylum policies, the ideal-type ‘supranational control of national capacities’ translates into an absence of redistributive risk- and responsibility-sharing. These dynamics are not driven by an integration logic or a general anti- or pro-EU stance, but by a substantive logic. What matters is not so much the extent and shape of integration, but its content, which in general has been marked by negative attitudes towards migration and a wish to decrease the number of immigrants (Bonjour, Ripoll Servent, and Thielemann Citation2018; Geddes Citation2000).

Origins of governmental preferences

State elites

The Core State Power framework presented in the introduction (Freudlsperger and Jachtenfuchs Citation2021) considers that state elites decide on the form and extent of integration depending on the trade-off between the material costs of integrating further and the status quo costs of not doing so. In the case of asylum, state elites comprise officials from the Interior Ministry, as well as regional (Länder) and local authorities responsible for the distribution and living conditions of asylum-seekers. While there is a potential for conflict between different levels of governance in a federal system (see Hellmann et al. Citation2005), Interior Ministry officials have tended to dominate policy-making on EU-related policies. In general, these officials tend to hold restrictive positions on asylum and prioritise security (Guiraudon Citation2000; Lavenex Citation2001, pp. 89–90).

This position reflects concerns about two types of material costs linked to integration. First, in respect of regulatory costs (hypothesis 1.1), Germany’s geographical position within Europe can be expected to make state officials favour uploading regulatory competences to the EU level in order to reduce the risk of secondary movements. In addition, given that Germany has been a long-term immigration country with strong asylum regulations, we should expect the German Interior Ministry to seek to upload national standards in order to avoid major implementation costs (Zaun Citation2016, Citation2017). Second, when it comes to capacity-building costs (hypothesis 1.2), more integration could potentially raise questions about the function of state elites. Following bureaucratic logic, therefore, state officials can be expected to limit any erosions of their core functions (e.g. deciding on who qualifies as a refugee), while at the same time ensuring that German administrations can cope with the number of asylum applications by promoting solutions that reduce the number of asylum-seekers in their territory (Interview_MS_1). Hence, we can expect state elites to prefer regulatory policymaking over EU-level capacity building. Only when the costs are prohibitive (e.g. serious disruptions at the EU’s external borders) would they advocate the creation of European capacities (e.g. a European Asylum agency).

Mass publics

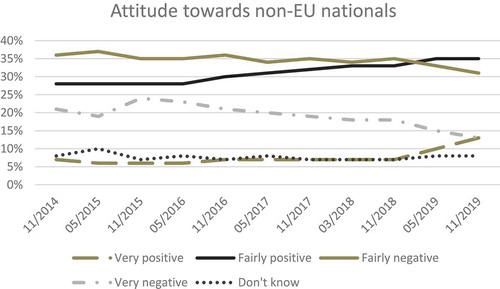

In the area of asylum, the preferences of state elites have long been overshadowed by the role of the public. demonstrates that the German public has held mostly negative attitudes towards immigrants from outside Europe since the asylum crisis, i.e. between 2014 and 2019. Roughly 35% of Germans have been fairly negative and around 20% very negative towards third-country nationals. Only between 5–10% are very positive about third-country nationals. Yet, between 28–35% have fairly positive attitudes towards these migrants, which highlights that, while attitudes towards third-country nationals are more negative than positive, they are not particularly strongly negative.

Figure 1. Positive and negative attitudes towards third-country nationals in Germany 2014–2019 (Source: Eurobarometer, Citation2019a)

Data from the German Longitudinal Election Study from June 2016 (Hambauer and Mays Citation2018, 144) suggest that voters supporting different political parties were equally hesitant about Germany’s ability to host refugees and the benefits migrants bring to society. 60.1% of CDU/CSU voters, 58.1% of SPD voters, 61.3% of FDP voters and 56.3% of Die Linke voters either did not believe that Germany could shoulder these refugees, or were uncertain about this. Only supporters of the Greens were comparatively optimistic, with 55.6% believing that Germany could successfully absorb them. When considering whether the arrival of these migrants/refugees was beneficial for Germany, roughly 74.6% of CDU/CSU voters, 71% of SPD voters, 76.3% of FDP voters, 63.1% of Green voters and 65.9% of Die Linke voters either believed that it was not, or were divided on this issue. The data suggest that the public is generally critical of immigration and prefer immigrant numbers to decrease rather than increase, regardless of which political parties they support.

Concerning European integration, Lahav (Citation2016, 1173) showed that ‘the European public is polarized over whether the EU or national governments should make immigration policy’. These trends largely hold for attitudes in Germany. An overview of Eurobarometer surveys shows that opinion is split on whether the EU should decide on the rules for political asylum. gives a good overview of support for EU integration of asylum policies since its inception in the Maastricht Treaty until full communitarisation in 2004.

Figure 2. Public attitudes in Germany on integration of asylum policies at the EU level 1992–2004 (Source: Eurobarometer, Citation2004)

highlights that, in the crisis and post-crisis years, support for a common European migration policy was consistently above 80% in Germany. While migration is more encompassing than asylum, it is certainly a good proxy in the absence of any recent Eurobarometer surveys on asylum policies. Moreover, forced migration was certainly the most relevant type of migration between 2014 and 2019. This number even exceeded the earlier peak in 1993, when support for a common asylum policy was just below 80%.

Figure 3. Public attitudes in Germany on a common European migration policy (Source: Eurobarometer, Citation2019b)

Taken together, show that attitudes towards EU asylum policymaking partly reflect the numbers of asylum applications in a given year (see ). When asylum-seeker numbers in Germany are high (e.g. in 1992, post-2014), the German public prefers more cooperation, and when numbers decrease (e.g. in 1999/2000), the German public tends to favour national policymaking. This suggests that taking an instrumental approach to European integration in asylum policies is not characteristic only of elites, but that the German electorate also sees the integration of EU asylum policies as a means of reducing the number of asylum-seeker in Germany. These preferences are apparently not affected by the ethnicity of the refugee population, since in the early 1990s Germany was receiving asylum-seekers mainly from the former Yugoslavia, while most of the asylum-seekers in 2015/16 were from the Middle East and Africa, especially Syria, Iraq and Eritrea.

Figure 4. Number of asylum applications per year (Source: OECD, Citation2020)

Political parties

While post-functionalists have focused on mass politics as a constraining factor for further integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), we argue that voter preferences are partly constitutive of government positions (hypothesis 2.2). Hence, we expect that voter preferences generally drive governments to reduce asylum-seeker numbers through redistribution at the EU level and to oppose policies that force them to take in higher shares of asylum-seekers. At the same time, we expect governments to purposefully mobilise voters to support their policies and not to be merely passive recipients of policy positions. Indeed, some research has suggested that the gap between positive and negative attitudes towards migration is probably smaller than expected, which offers a chance for voter mobilisation (hypothesis 2.1). Kitschelt (Citation1997, 4–19) has suggested that anti-immigrant attitudes are not necessarily the result of higher numbers of immigrants (demand-side), but are usually based on right-wing populist parties mobilising these attitudes (supply-side). Previous research showed that those who were more attached to a national identity and feared losing their religion, language and traditions tended to support more restrictive positions on migration, and hence national rather than EU immigration policies (Ivarsflaten Citation2005; Luedtke Citation2005). Therefore, the presence of populist and/or radical parties that use nativist ideologies reinforces anti-migrant and Eurosceptic discourses (Ivarsflaten Citation2008). This trend has been particularly problematic for mainstream parties (Volksparteien), which have often lost voters to emerging challengers on the fringes of the ideological spectrum. The reaction of many mainstream parties, particularly those on the centre-right, has been to copy the ideas and messages of these challengers (Bale Citation2008; Meguid Citation2005; van Spanje and de Graaf Citation2018). Therefore, we expect that the presence of challenger parties will politicise the issue of migration and turn it into a core issue in electoral contests. The more governmental parties feel themselves (electorally) threatened by fringe challenger parties, the more they will support EU policies that minimise the number of asylum-seekers in Germany.

Domestic actor constellations and the role of political parties in Germany’s formulation of positions on EU asylum policies

The empirics support our expectations regarding the consistency of positions across political parties and the relevance of right-wing populist challengers. During the past 30 years, governments composed of different political backgrounds attempted to convince their voters that they were trying to reduce migration. During the early 1990s, with a coalition between the CDU/CSU and the FDP dominating German politics, the main aim was to find ways of reducing the number of asylum-seekers. Indeed, the increasing use of pejorative terms for asylum-seekers and refugees (Asylanten) coupled with the restrictive discourse that was coming from extreme right-wing parties such as the Republikaner, which was copied by some government actors, led to a rising extreme-right movement and arguably contributed to the recurrent attacks on asylum-seeker reception centres and migrants’ homes. This, in turn, transformed the issue of asylum into a major electoral concern, which led the CDU to adopt a more restrictive position and push for the downgrading of the right to asylum from a constitutional to a mere legal principle. In 1993, with the support of the SPD, the CDU introduced the notion of safe countries of origin and transit in the German Basic Law (Art. 16) (Angenendt Citation1997, pp. 91–120; Bosswick Citation2000; Crage Citation2016).

Electoral concerns also undermined any significant liberalisations when the SPD came into power in 1998. Although the number of asylum-seekers had been decreasing for some time, reverting the change in the Basic Law was seen as being too unpopular to implement (Bosswick Citation2000, 55). The SPD-Green coalition therefore maintained the status quo, thereby reinforcing the message that the number of migrants in Germany should be kept low. This policy can be largely explained by the economic downturn of the early 2000s and the introduction of the Agenda 2010 by Chancellor Schröder (cf. Hess and Green Citation2016). And so, although the SPD-Green coalition did produce a change in the migration culture of Germany (notably with the reform of nationality law), the changes made in asylum law were more limited. In a very few areas, such as gender-related persecution, Germany became a front-runner after honour crimes and cases of female genital mutilation received significant public attention (Brabandt Citation2011). Besides, some of the changes introduced in the 2005 Immigration Law (by then under Merkel’s first Grand Coalition) reflected new provisions largely adopted as an adaptation to the 2004 EU Qualification Directive; notably, the new law included non-state actors as potential sources of persecution, an issue on which Germany had been increasingly isolated since the late 1990s. However, Germany had strategically used a veto on this issue in the Council negotiations in order to water down EU asylum legislation in other areas. Overall, as one of the countries taking a clear stance on providing fewer rights to subsidiary protection holders compared to refugees and not systematically recognising war refugees, Germany became one of the major ‘breaksmen’ in the process of harmonising asylum policies with a high level of protection (Zaun Citation2017, pp. 148–149). Nationally, the Grand Coalition introduced further amendments to the 1993 Welfare Act, and reduced the reception conditions and access to welfare provisions for asylum-seekers (Crage Citation2016).

In sum, despite changes in the governmental coalitions, there was continuity in the effort to maintain the status quo, and even a push for further restrictions to keep asylum-seeker numbers low. Indeed, over the last fifteen years of the Grand Coalition, the SPD and CDU (and to some extent the CSU) aligned their positions more closely in the area of migration, making the Grand Coalition particularly costly for the SPD in electoral terms (Schmidtke Citation2016). These dynamics became particularly evident after 2015, when the renewed increase in numbers again brought the issue of restriction to the top of the electoral agenda. The shift of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) from a Eurosceptic into a far-right anti-immigration party contributed to the politicisation of the issue of asylum. In a way, the situation after the 2015–2016 crisis was similar to the one Germany found itself in during the 1990s (the political usage of asylum in negative terms contributing to a rise in xenophobic attitudes and attacks against migrants). This created a rift in the Christian-democratic family – with the CDU opting for more moderate positions while the CSU tried to regain the space lost to the AfD by moving to the right (Dilling Citation2018). Indeed, we need to understand German internal politics and the difficulties in maintaining the Grand Coalition (and especially the coalition between the CDU and CSU) to explain the position held by Germany in EU negotiations after 2015 (hypothesis 2.1). Notably, Merkel’s position in the negotiations on the Dublin reform in June 2018 was clearly weakened when Interior Minister Seehofer (CSU) demanded a clear commitment from the German chancellor to return asylum-seekers to Italy (BBC, Citation2018).

Germany’s positions on EU asylum policies at the level of integration and policy substance

Extent of integration: the procedural merry-go-round

Germany has played a rather ambivalent role when it came to the voting procedure in the area of asylum policies (Zaun Citation2017, pp. 64–71). In the early 1990s, when Germany became the main destination country for asylum-seekers in the EU and was facing rising right-wing extremism, its government took the lead in pushing for the communitarisation of asylum policies. The successive Kohl governments (CDU-FDP coalitions) hoped that communitarising asylum policies would help distribute asylum-seekers more evenly. However, due to resistance from the United Kingdom, asylum policies remained purely intergovernmental in the Maastricht Treaty (Henson and Malhan Citation1995, 139).

During the negotiations over the Treaty of Amsterdam, the German government (still led by Helmut Kohl in a CDU-FDP coalition) stopped promoting full communitarisation. Propelled by the criticism of the Länder, which were empowered through the principle of subsidiarity in the Maastricht Treaty and played a central role in the reception of asylum-seekers, Germany became a major critic of qualified majority voting (QMV) in this area. With the numbers of asylum applicants clearly on the decline (104,4355 in 1997 as opposed to 438,190 in 1992, see Council 2009/14,863 ADD 4: 13), ‘the Länder were unwilling to dilute national sovereignty to an extent that could enable European decision makers to reverse that trend’ (Hellmann et al. Citation2005, pp. 151–153). The Amsterdam Treaty, therefore, maintained the principle of unanimity in the Council (Art 67.II) and established a shared right of initiative between the Commission and the member states. The EP was only consulted (Art. 67.I), and only tribunals with no judicial remedy under national law were able to request preliminary rulings from the EU Court of Justice (Art. 68). Amsterdam, however, proposed a special form of treaty revision in which, after five years, the Council could unanimously decide on the application of the co-decision procedure (and QMV), thus conveying more powers to other EU institutions.

This procedure was adopted in 2005, during the negotiations of the Constitutional Treaty. Again, the German government, this time under the SPD/Green coalition, became one of the main blockers in this area (Brabandt Citation2011, p. 175; Deutscher Bundestag, Citation2003a, p. 6036). A coalition of the Convention members Joschka Fischer (foreign minister, Green party), Erwin Teufel (prime minister of Baden-Württemberg, representing the Bundesrat; Christian Democrat), Jürgen Meyer (representing the Bundestag; Social Democrat), backed by German chancellor Gerhard Schröder, wrote a letter to Convention President Giscard d’Estaing suggesting the possibility of keeping a national veto on questions of immigration and asylum. They feared that QMV would lead to a renewed increase in the inflow of asylum-seekers into Germany, which would have a negative impact on the German labour market – a possibility already suggested by the Bavarian Prime Minister Edmund Stoiber (Euobserver, Citation2003; Financial Times Deutschland, Citation2003).

Interestingly, here the UK became the most fervent supporter of QMV in this area. In the early 2000s, the UK was experiencing a peak in asylum applications, partly attributed to its more liberal policies regarding cases of non-state persecution compared to Germany and France. Like Germany previously, the UK arguably overestimated the actual openness of its asylum system (Interview Consultant_1/2013), but felt that, by further harmonising policies and increasing the EU’s capacity to take quicker decisions, this would lead to the adoption of more ambitious policies, alleviate the pressures on its own asylum system, and ensure a more equal distribution of asylum-seekers (Fella Citation2006, 634). Germany and the UK eventually agreed on a package deal: asylum policies were to be fully communitarised in the Constitutional Treaty, as suggested by the UK. However, following the German position, labour migration policies would still be decided under unanimity (Ibid). As the Constitutional Treaty did not pass, asylum policies shifted to co-decision in 2005, whereas labour migration policies remained intergovernmental until the conclusion of the Lisbon Treaty.

This section has highlighted that EU member states adopt an instrumental approach to the integration of asylum policies, supporting it only when it helps to decrease their asylum-seeker numbers. This occurs regardless of whether they are supposedly pro-integrationist (Germany) or Eurosceptic (UK). As expected by hypothesis 2.2, the changing position of the German government also largely reflects the positions of the public on the integration of asylum policies (see ). The increased support for joint asylum policies in 2003 can be explained by Chancellor Schröder mobilising voters in favour of the issue in preparation for the package deal with the UK, which highlights once again that governments are not passive recipients of voter preferences, but mobilise voters pro-actively (hypothesis 2.1).

Content of integration: the legislative merry-go-round

Germany also followed an erratic approach on the substance of the CEAS. As seen above, after the introduction of the Schengen area (1985/1990) some member states felt that asylum policies should be coordinated at the EU level. This drive for integration came mostly from member states in the Centre and North-West of Europe, including Germany, which was a strong supporter of asylum harmonisation to address secondary movements but did not have a broader vision of how to shape and design a truly European Asylum System. While in theory successive German governments promoted deeper integration and a high level of standards, they soon realised that these standards were, in fact, not the most generous in the EU. During the CEAS negotiations, the German government was determined to ‘upload’ its positions in the first (and, indeed, also in the second) phase of the CEAS, usually citing its long-standing expertise, which had made it something of a role model (Interview PermRep_1/2012; Interview MS_1/2012). In practice, this meant that German negotiators were not ready to adopt more liberal policies that had proven successful in other member states, nor even to seek a compromise (Zaun Citation2016, Citation2017). This attitude demonstrated to other member states that strong regulators such as Germany were not pursuing strong protection standards, but only a redistribution of asylum-seekers towards those countries perceived as more restrictive (Interview Consultant_1/2013).

As set out in hypothesis 1.1, Germany generally preferred a regulatory approach to EU level capacity-building. This changed only after 2015, when it became clear that border countries were not properly implementing the CEAS and that this was leading to significant secondary movements towards Germany (as well as other traditional destination countries). Germany and like-minded states such as the Netherlands and Sweden became supporters of EU level capacity-building through the introduction of an EU Asylum Agency, which would intervene when member states failed to implement the CEAS (Interview PermRep_1/2019; Interview PermRep_2/2019). However, contrary to what hypothesis 1.2 proposes, these traditional destination countries did not perceive the introduction of the EU Asylum Agency as a significant sovereignty transfer; contrary to Southern border countries or even CEE member states, they perceived the chance of having to face an intervention in their domestic system as highly unlikely (Interview PermRep_3/2019; see also Ripoll Servent Citation2018).

The German government did not only play this ambivalent role in the area of asylum policy harmonisation, but also regarding the physical redistribution of refugees. In 1994, German negotiators promoted a quota scheme, based on GDP and population size, along the lines of its national Königsteiner Schlüssel, which determines how asylum-seekers are distributed across the German Länder (Council of the European Union, Citation1994). Clearly, the German government was looking for a way to have other member states take a larger share of asylum-seekers; while destination countries such as the Netherlands were clearly in favour of this, other member states, such as France and the UK, resisted the idea, since they were receiving fewer applications (Boswell Citation2003). Given the generalised opposition to a distribution key, German negotiators soon had to abandon the idea, and the responsibility principle established in the Dublin Convention remained in place.

The Dublin Convention was only slightly amended in the Dublin II Regulation (Council Regulation 343/2003/EC), which included new criteria for attributing responsibility in the processing of asylum applications, such as hosting family members of an applicant. When Dublin II was to be reformed into Dublin III in the late 2000s, border countries were already facing larger inflows of asylum applications. Having previously been countries of emigration rather than immigration, these countries were easily overwhelmed by the inflows of asylum-seekers subsequent to the Arab Spring in 2011. They therefore promoted the idea of suspending transfers under the Dublin procedure in situations of high influx (Interview PermRep 1_2012). This would allow border countries to avoid having to take back asylum-seekers that had transited onwards towards Northern European countries so as not to overload their asylum systems even further.

At the time, Germany was among the member states that most decisively defended the status quo and opposed a suspension of transfers. It even persisted in this approach when transfers to Greece were no longer automatically possible, following the ECtHR judgment of MSS vs Greece in 2011 (Application No. 30,696/09) and the CJEU judgment of NS vs Secretary of State in 2012 (joined Cases C-411/10 and C-493/10). This was mainly driven by the rationale that Northern member states, which were still receiving the lion’s share of asylum applications, did not want to give up the powerful tool that was Dublin (Interview PermRep_2/2012). Arguably, keeping the first-country-of-entry principle and not allowing a suspension of transfers were the only means to discipline border countries, which would otherwise have no incentive to stop secondary movements. However, border countries were deeply disappointed that the traditional destination countries would not show any solidarity. In their view, the Northern countries were the ones attracting asylum-seekers and were thus partly to blame for the situation in the border countries themselves (Interview PermRep_3/2012). The Dublin III Regulation eventually included an early-warning system (a compromise introduced by the Polish Presidency in 2013) for situations of mass influx. However, since the system can only be triggered after an intricate procedure in the Council, it has never been applied – not even in the 2015 crisis.

Having blocked any solidarity mechanism in Dublin III, Germany made again a U-turn in 2015, when the overburdening of border countries was clearly visible and leading to self-relocations among asylum-seekers towards North-Western/Central European countries. While Germany generally presented its support towards the Relocation Decisions and subsequent debates about a permanent quota system as a means of showing solidarity with the overburdened border countries, the timing suggests that the actual aim was to stop asylum-seekers from self-relocating to Germany (Zaun Citation2018). Some of the Visegrad countries were clearly aware of this. According to one JHA Counsellor (Interview PermRep_1/2016), while the Relocation Decisions were measures that would help border countries to some extent, any permanent system was mainly considered a policy to support traditional destination countries, including Germany. As the German Chancellor was considered responsible for the high inflow of asylum-seekers, the Visegrad countries were not keen to show any solidarity with Germany. When the numbers of asylum-seekers were again in decline, the German government became more silent on refugee quotas, which shows how, in the absence of pressure on its asylum system, Germany had no incentive to continue supporting the border countries.

How does Germany compare to other EU member states?

As the case of the UK demonstrates, prioritising substantive outcomes (fewer asylum-seekers) at the expense of a consistent position on EU integration is not solely a German phenomenon, but characteristic of a policy area where governments have little room to manoeuvre and where pro-migrant policymaking is likely to be punished by the electorate. Indeed, Germany’s opportunistic behaviour in EU asylum policies reflects the rule rather than the exception: over time, most member states have adopted a similar approach. EU integration on asylum policies was initiated in the late 1990s by asylum-seekers – including the Netherlands, France, the UK and Sweden in addition to Germany – that hosted many asylum-seekers. These countries had fully functional asylum systems and felt that other countries, especially those in the South of Europe (but also those soon to join the EU) received fewer asylum-seekers only because they did not have asylum systems as generous as theirs. Hence, they hoped that a common EU asylum policy would ensure a more even distribution of asylum-seekers (Zaun Citation2017). The decision of the border countries to accept the Dublin regime might appear more puzzling, but Thielemann and Armstrong (Citation2013) have argued that it was the price they had to pay to be included in the Schengen club. However, the behaviour of the border countries has shifted over time and become more aligned to that of the Northern countries: those that continue to face high numbers of asylum-seekers (notably Greece and Italy) repeatedly ask for more solidarity; in contrast, countries like Spain, which receives fewer asylum-seekers, can often be found aligning themselves with those that want to prevent redistribution (Zaun Citation2017, p. 199, Citation2018, 54).

This ‘not in my backyard’ approach has become intrinsic to the CEAS, which explains the failure to find alternative solutions to the current Dublin system. Since the reform of the CEAS was proposed in 2016, ten Council presidencies have attempted to reach some kind of agreement – including Germany between July and December 2020. All have had to accept defeat and face the fact that no national government is ready to openly accept more asylum-seekers in its territory. The Visegrad states have visibly opposed the adoption of refugee quotas since 2016, because they want to avoid any policy that might increase their share of asylum-seekers (Zaun Citation2018). However, they alone cannot form a blocking minority, which means that a wider range of countries are equally unsupportive of offering more solidarity to frontline member states.

Conclusion

The article has demonstrated that Germany (like most member states) follows a ‘not in my backyard approach’. As member states consider refugee protection a zero-sum game in which every potential gain for another member state could entail a loss for themselves, they do not behave cooperatively but are focused on their individual goals. This situation does not provide fertile ground for sustainable integration. Indeed, it underlines the fact that asylum continues to be perceived as a ‘burden’ – a material cost to be avoided. As a result, the politicisation of asylum (and more generally, migration) means that governments pay an audience cost if they are perceived as supporting policies that lead to higher numbers of asylum-seekers – especially if such governments have to compete with far-right and populist parties mobilising migration for electoral purposes. Hence, we have argued that the position of governmental actors will be intimately linked to how much they can use the EU to build policies that benefit Germany (i.e. that limit the number of asylum-seekers).

This analysis of Germany’s actor constellations underlines the importance of substance when explaining the German process of preference formation. It highlights that the demands of public opinion, together with the strategies of the political parties involved, are constitutive of successive German governments’ positions on EU asylum policies. Voter preferences transcend the notion of a permissive consensus or a constraining dissensus (see hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2.; paper1), since governments’ positions seem to closely follow voter preferences on substantive matters (i.e. the number of migrants) more than they do on European integration. Indeed, voter and political parties’ preferences seem to align strongly with state elites, as both aim to restrict migration and both consider EU integration a tool for ensuring that Germany does not have to bear the ‘burden’ alone.

We have also demonstrated that Germany has had a strong preference for regulatory policymaking over the past 30 years (hypothesis 1.1). However, since the asylum crisis, which entailed significant increases in the number of asylum applications and material as well as audience costs in Germany, the German government has pushed for EU level capacity-building through the adoption of a European Union Asylum Agency that will enforces the CEAS in (border) countries with low capacities (hypothesis 1.2).

These shifting views on capacity-building make Germany inconsistent and unreliable when it comes to the process of integration in the area of asylum. This behaviour has caused it to lose credibility and has prevented it from acting as a leader when needed (as in the 2015–2016 crisis or during the German presidency of 2020). Other countries have identified Germany’s strategy as opportunistic and inconsistent; this means that potential allies do not trust Germany to back them in the long term, and that Germany’s inconsistency makes potential opponents more confident that their efforts to block changes they consider undesirable will be successful. This only contributes to missing opportunities for reforming the EU’s asylum system into a sustainable integration project.

Biographical note

Natascha Zaun is an Assistant Professor in Migration Studies at the European Institute at LSE.

Ariadna Ripoll Servent is a Professor of European Integration at the Department of Social Sciences and Economics at the University of Bamberg, Germany and a Visiting Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Angenendt, S. 1997. Deutsche Migrationspolitik im neuen Europa. Opladen: Leske + Budrich. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-92281-6.

- Bale, T. 2008. “Turning Round the Telescope. Centre-right Parties and Immigration and Integration Policy in Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (3): 315–330.

- BAMF. 2015. #Dublin-Verfahren syrischer Staatsangehöriger werden zum gegenwärtigen Zeitpunkt von uns weitestgehend faktisch nicht weiter verfolgt, available at: https://twitter.com/bamf_dialog/status/636138495468285952?lang=de

- BBC. 2018. Merkel ally offers to quit over migrants. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe–44674945

- Betts, A. 2003. “Public Goods Theory and the Provision of Refugee Protection: The Role of the Joint-Product Model in Burden-Sharing Theory.” Journal of Refugee Studies 16 (3): 274–296.

- Bonjour, S., A. Ripoll Servent, and E. Thielemann. 2018. “Beyond Venue Shopping and Liberal Constraint: A New Research Agenda for EU Migration Policies and Politics.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (3): 409–421. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1268640.

- Bosswick, W. 2000. “Development of Asylum Policy in Germany.” Journal of Refugee Studies 13 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1093/jrs/13.1.43.

- Boswell, C. 2003. “Burden-Sharing in the European Union: Lessons from the German and UK Experience.” Journal of Refugee Studies 16 (3): 316–335. doi:10.1093/jrs/16.3.316.

- Brabandt, H. 2011. Internationale Normen und das Rechtssystem: Der Umgang mit geschlechtsspezifisch Verfolgten in Großbritannien und Deutschland. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Council of the European Union. 1994. Draft Council Resolution on burden-sharing with regard to the admission and residence of refugees, Pub. L. No. 7773/94 ASIM 124.

- Crage, S. 2016. “The More Things Change … Developments in German Practices Towards Asylum Seekers and Recognised Refugees.” German Politics 25 (3): 344–365. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1193159.

- Der Spiegel.. (2016, August 24). Two Weeks in September: The Makings of Merkel’s Decision to Accept Refugees. Spiegel Online. Retrieved from: https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/a-look-back-at-the-refugee-crisis-one-year-later-a-1107986.html

- Deutscher, B. 2003a. Bundestagsplenarprotokoll. 15.Wahlperiode, 17. Sitzung. Document Number 15/70. Berlin. Retrieved from: http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btp/15/15070.pdf

- Dilling, M. 2018. “Two of the Same Kind?: The Rise of the AfD and Its Implications for the CDU/CSU.” German Politics and Society 36 (1): 84–104. doi:10.3167/gps.2018.360105.

- ECRE. 2012. Asylum Lottery in the EU in 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2013, from http://www.ecre.org/component/content/article/56-ecre-actions/294-asylum-lottery-in- the-eu-in-2011.html

- Euobserver. 2003. Convention ready to adopt European Constitution.

- Euobserver. 2015. Orban: Migrant crisis is Germany’s problem. EUobserver. Retrieved from https://euobserver.com/migration/130101

- Eurobarometer 2004. For each of the following areas, do you think that decisions should be made by the (NATIONALITY) government, or made jointly within the European Union? Rules for political asylum European Union (from 03/1992 to 10/2004), October 2004, Public Opinion. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/chartType/lineChart//themeKy/10/groupKy/296/savFile/112

- Eurobarometer. 2019a. Please tell me whether each of the following statements evokes a positive or negative feeling for you. Immigration of people from outside the EU European Union (from 11/2014 to 11/2019), November 2019, Public Opinion. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/chartType/lineChart//themeKy/59/groupKy/279/savFile/646

- Eurobarometer (2019b). What is your opinion on each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement, whether you are for it or against it. A common European policy on migration., November 2019, Public Opinion. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/chartType/mapChart//themeKy/29/groupKy/180/savFile/895

- Fella, S. 2006. “New Labour, Same Old Britain? the Blair Government and European Treaty Reform.” Parliamentary Affairs 59 (4): 621–637. doi:10.1093/pa/gsl030.

- Financial Times Deutschland. 2003. Stoiber lehnt Vorschlag für Europäische Verfassung ab.

- Financial Times, G. (2017). Merkel changes tack to put refugee crisis back on campaign agenda. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/d41e28cc-8bcb-11e7-9084-d0c17942ba93

- Freudlsperger, C. & M. Jachtenfuchs. 2021. “A member state like any other? Germany and the European integration of core state powers.„ Journal of European Integration 43(2), doi: 10.1080/07036337.2021.1877695

- Geddes, A. 2000. Immigration and European Integration: Towards Fortress Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Guild, E. 2006. “The Europeanisation of Europe’s Asylum Policy.” International Journal of Refugee Law 18 (3/4): 630–651. doi:10.1093/ijrl/eel018.

- Guiraudon, V. 2000. “European Integration and Migration Policy: Vertical Policy-Making as Venue Shopping.” Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (2): 251–271. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00219.

- Hambauer, V., and A. Mays. 2018. “Wer wählt die AfD? – Ein Vergleich der Sozialstruktur, politischen Einstellungen und Einstellungen zu Flüchtlingen zwischen AfD-WählerInnen und der WählerInnen der anderen Parteien.” Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12 (1): 133–154. doi:10.1007/s12286-017-0369-2.

- Hellmann, G., R. Baumann, M. Bösche, B. Herborth, and W. Wagner. 2005. “De-Europeanization by Default? Germany’s EU Policy in Defense and Asylum.” Foreign Policy Analysis 1 (1): 143–164. doi:10.1111/j.1743-8594.2005.00007.x.

- Henson, P., and N. Malhan. 1995. “Endeavours to Export a Migration Crisis: Policy Making and Europeanisation in the German Migration Dilemma.” German Politics 4 (3): 128–144. doi:10.1080/09644009508404417.

- Hess, C., and S. Green. 2016. “Introduction: The Changing Politics and Policies of Migration in Germany.” German Politics 25 (3): 315–328. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1172065.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- Ivarsflaten, E. 2005. “Threatened by Diversity: Why Restrictive Asylum and Immigration Policies Appeal to Western Europeans.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 15 (1): 21–45. doi:10.1080/13689880500064577.

- Ivarsflaten, E. 2008. “What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?: Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1177/0010414006294168.

- Kitschelt, H. 1997. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Lahav, G. 2016. “Public Opinion toward Immigration in the European Union: Does It Matter?” Comparative Political Studies 37 (10): 1151–1183. doi:10.1177/0010414004269826.

- Lavenex, S. 2001. The Europeanisation of Refugee Policies: Between Human Rights and Internal Security. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Luedtke, A. 2005. “European Integration, Public Opinion and Immigration Policy: Testing the Impact of National Identity.” European Union Politics 6 (1): 83–112. doi:10.1177/1465116505049609.

- Meguid, B. M. 2005. “Competition between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051701.

- Niemann, A. 2006. Explaining Decisions in the European Union.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. 2020. International Migration Database, June 2020. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=MIG

- Ripoll Servent, A., and F. Trauner. 2015. “Asylum: Limited Policy Change Due to New Norms of Institutional Behaviours.” In Policy Change in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice: How EU Institutions Matter, edited by F. Trauner and A. Ripoll Servent, 35–52. London: Routledge.

- Ripoll Servent, A. 2018. “A New Form of Delegation in EU Asylum: Agencies as Proxies of Strong Regulators.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1111/jcms.12652.

- Ripoll Servent, A. 2019. “Failing under the ‘Shadow of Hierarchy’: Explaining the Role of the European Parliament in the EU’s ‘Asylum Crisis’.” Journal of European Integration 41 (3): 293–310. doi:10.1080/07036337.2019.1599368.

- Ripoll Servent, A., and N. Zaun. 2020. “Asylum Policy and European Union Politics.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1057.

- Schmidtke, O. 2016. “The ‘Party for Immigrants’? Social Democrats’ Struggle with an Inconvenient Electoral Issue.” German Politics 25 (3): 398–413. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1182992.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Thielemann, E. 2018. “Why Refugee Burden-Sharing Initiatives Fail: Public Goods, Free-Riding and Symbolic Solidarity in the EU.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1111/jcms.12662.

- Thielemann, E., and C. Armstrong. 2013. “Understanding European Asylum Cooperation under the Schengen/Dublin System: A Public Goods Framework.” European Security 22 (2): 148–164. doi:10.1080/09662839.2012.699892.

- Time. 2015. Person of the year: chancellor of the free world. Retrieved from: https://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-2015-angela-merkel/

- van Spanje, J., and N. D. de Graaf. 2018. “How Established Parties Reduce Other Parties’ Electoral Support: The Strategy of Parroting the Pariah.” West European Politics 41 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1332328.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications. Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Zaun, N. 2016. “Why EU Asylum Standards Exceed the Lowest Common Denominator: The Role of Regulatory Expertise in EU Decision-making.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (1): 136–154. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1039565.

- Zaun, N. 2017. EU Asylum Policies: The Power of Strong Regulating States. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zaun, N. 2018. “States as Gatekeepers in EU Asylum Politics: Explaining the Non-adoption of a Refugee Quota System.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 44–62. doi:10.1111/jcms.12663.

- Zaun, N. 2019. “Member States as ‘Rambos’ in EU Asylum Politics: The Case of Permanent Refugee Quotas.” In The New Asylum and Transit Countries in Europe during and in the Aftermath of the 2015/2016 Crisis, edited by V. Stoyanova and E. Karageorgiou, 211–232. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

List of Interviews

Interview Consultant_1/2013, 24 March 2013

Interview MS_1/2012, 16 October 2012

Interview PermRep_1/2012, 30 March 2012

Interview PermRep_2/2012, 29 March 2012

Interview PermRep_3/2012, 13 April 2012

Interview PermRep_1/2016, 6 October 2016

Interview PermRep_1/2019, conducted 1 April 2019

Interview PermRep_2/2019, conducted 3 April 2019

Interview PermRep_3/2019, conducted 21 May 2019