ABSTRACT

This article analyses how the administrative-bureaucratic or staff support structures available to Members of the European Parliament (Secretariat officials, political group advisors and parliamentary assistants) changed in response to the formal development of the European Parliament into a legislature or parliamentarisation. Providing a temporal perspective, the aim is to explain bureaucratisation (as the processes whereby non-elected officials carry out elected representatives’ duties and tasks) as it presents in the EP today. Based on interviews and other data, findings show that while changes to administrative-bureaucratic structures have not always been timely to EP’s parliamentarisation, they strengthened the EP’s administrative capacity incrementally. Arguing that administrative and political structures develop differently at given moments and infringe upon another, the article discusses the consequences of staff support for democracy. The analysis shows that the diversity of administrative structures is a source for maintaining democratic control in parliament and limiting bureaucratisation.

Introduction

As a source of knowledge, bureaucracies are an important asset for running democratic government (Peters Citation2015). Yet, a large part of the European public thinks of the European Union’s (EU) bureaucracy as undemocratic (e.g. European Commission Citation2018, 7). This perception is linked to the cost of political delegation and bureaucratisation. Simply defined, bureaucratisation is the process whereby non-elected officials carry out duties and tasks of elected representatives (Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman Citation1981, ch. 1; Ellinas and Suleiman Citation2012, 89; Meier and O’Toole Citation2006, 12). It is related to the term politicised competences, which describe the shrinking distance between politicians and civil servants (e.g. Romanyshyn and Neuhold Citation2013). Bureaucratisation requires attention because the actions of unelected officials do not have the same legitimacy as the actions of those chosen by the people (Meier and O’Toole Citation2006, 12).

Balancing the cost and benefits of bureaucracy – defined here as unelected officials and administrators – is one of the many challenges democracies face. In examining this challenge for the EU institutions, scholarly discussion has focused on the largest bureaucracy – the European Commission. In the aftermath of the Lisbon Treaty, several scholars have raised questions on delegation and the bureaucratisation of policy-making in the parliamentary context. Studying the European Parliament (EP), researchers found that legislative staff do not merely implement parliamentarians’ decisions but also engage in tasks relevant to policy and politics, such as drafting amendments and proposing compromises (Dobbels and Neuhold Citation2013). These findings, combined with unfavourable public opinion, show the continued importance to raise questions on the role of bureaucracy in democratic systems.

Compared to previous studies, this article adopts a temporal perspective on the development of administrative structures. It is asked how the parliamentarisation of the EP – understood as the formal institutionalisation of the EP into a legislature with representative, budgetary, scrutiny and law-making functions (Rittberger Citation2012, 45–49) – has affected the administrative-bureaucratic or staff support structures in the EP, namely the staff of the Secretariat, the staff of political groups and the personal staff of MEPs. A historical institutionalist analysis is adopted, stressing the need to study bureaucratisation as a process that unfolds over time (Pierson Citation2003).

Taking a long-term perspective on the administrative players of the EP is pertinent for a couple of reasons. For the first three decades of the EP (as the Common Assembly and Parliamentary Assembly), administrative players were permanently based in parliament. Members were nominated in national parliaments and came to the EP monthly. While political leadership offers a crucial vehicle for the democratic control of bureaucracy (Page and Wouters Citation1994), in the EP, it was limited by the part-time nature of the job of its members. These starting conditions might have given administrative players leeway to develop their functions and influence the way administrators interact with policy-makers today. A temporal analysis can also enrich our understanding of institutional change since outcomes (e.g. reforms of administrative structures) can occur at a considerable distance from the appearance of a central cause (e.g. parliamentarisation) (Orren and Skowronek Citation1994; Sewell Citation1996). Adopting a temporal perspective, the article provides an empirical contribution by contextualising the development of bureaucratisation beyond the Lisbon Treaty. The article also shows the relevance of studying administrative structures in their own right to further our understanding of the quality of democracy in parliament.

Based on interviews, primary and secondary data, findings show that the EP’s bureaucratic structures have been reshaped incrementally but not always promptly following parliamentarisation. Reforms have altered the balance between elected officials and administrators while maintaining the latter’s legitimacy. From a period when the Secretariat’s administrators had leeway, support became more balanced. The source of advice has diversified between staff in the Secretariat, political groups and MEPs’ offices. Staff support provision has also become fairer, as both individual members and collective bodies (committees, party groups, the plenary, etc.) have access to services. While the recast of administrative structures has not always been timely with the EP’s political evolution into a fully-fledged legislature, it has followed the path of parliamentary (administrative) autonomy as initially charted in the 1950s. The absence of timely reforms has had more consequences on the EP’s efficacy than the legitimacy of administrative actions.

In the following, the article reviews the literature on the EP administration, given its approach to bureaucratisation and explains time dimensionality concerning the development of the politico-bureaucratic relationship in the EP. What follows is the presentation of empirical data and a discussion. In conclusion, the main findings, limits and avenues for further research are outlined.

Parliamentary staff and bureaucratisation

This article’s conceptualisation of bureaucratisation follows the understanding of bureaucracy as the ensemble of non-elected actors employed in the Secretariat, political groups, and MEPs’ offices. Consequently, bureaucratisation is defined as the process whereby non-elected actors carry out elected representatives’ duties and tasks (Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman Citation1981, ch. 1). The term politicised competences has been used to describe the shrinking distance between politicians and civil servants (Romanyshyn and Neuhold Citation2013). These are broadly the same phenomena questioning the action legitimacy of unelected officials (Meier and O’Toole Citation2006, 12). In this article, I use the concept of bureaucratisation as it signifies a temporal process (Torstendahl Citation2001, 1410).

While relatively unexplored compared to its American counterparts, administrative actors in parliament are a growing research area in Europe. Most of the research has been focused on comparing MPs’ work as elected representatives and the work done by staff as unelected actors working in parliament. Bureaucratisation has been assessed from the view of task delegation, considering premises of rational behaviour and principal-agent models. To a lesser extent, research has looked into administrators’ descriptive characteristics and behavioural attitudes. A clear-cut understanding of the extent of bureaucratisation has so far proved elusive, which shows scope for continued research. Part of the problem is that the EP’s administration is diversified and active in several policy areas that are differently politicised (e.g. given the influence that the treaties confer to the EP or societal interest). In the following, I explore how bureaucratisation has been analysed so far, but first, a review of EP’s administrative-bureaucratic structures is provided.

Parliamentary administrative structures

The EP’s administration or bureaucracy consists of three actors sharing an unelected status: the staff or officials employed in the Secretariat, political advisors of party groups and MEPs’ assistants. In 2020, there were 5,351 Secretariat staff, 1,282 group staff and 3,287 MEP assistants (European Union Citation2020; European Parliament Citation2020). Secretariat staff are recruited through competitive tests formalising a Weberian-style bureaucracy in neutrality requirements, professionalism and a hierarchical career structure. Political advisors tend to be recruited via competitions organised at the level of individual political groups. The majority are either members or sympathisers of a party (Ruiter Citation2019, 170). Assistants are recruited directly by MEPs and work either in parliament or the constituency. Compared to Secretariat’s staff, political advisors and assistants’ employment is less secure and dependent on electoral volatility, where job security is generally greater for the former.

Different working conditions mean that the legitimacy of Secretariat staff is derived from their civil service status. In contrast, the legitimacy of political advisors and MEP assistants depends on political trust to the group and MEP. Given the different legitimacy sources, staff in the EP are interdependent in assisting MEPs (Neunreither Citation2002), and a balance between them needs to be struck to preserve democratic legitimacy (Provan Citation2001). So far, research has focused on understanding the role of committee officials employed in the Secretariat. Less attention has been given to political groups advisors and parliamentary assistants.

Bureaucratisation

Delegation

The majority of studies has looked at bureaucratisation from the point of task delegation. Dobbels and Neuhold (Citation2013) developed a typology specifying the production, service and steering roles of the EP Secretariat. The production role (e.g. offering knowledge, advice and skills to politicians) represents the lowest level of involvement in policy-making compared to the service role (e.g. procedural advice and briefings) and steering role (e.g. drafting agendas, writing reports and proposing compromises). Bureaucratisation can be discerned when staff carry out politicised tasks beyond a production role. Such behaviour has been observed on non-salient issues and politically sensitive dossiers (Dobbels and Neuhold Citation2013; Romanyshyn and Neuhold Citation2013; Neuhold and Dobbels Citation2015; Högenauer, Neuhold, and Christiansen Citation2016; Coremans and Meissner Citation2018). On the other hand, Winzen (Citation2011) and Neuhold and Radulova (Citation2006, 57) observed that MEPs have a high degree of discretion and maintain the overall system’s equilibrium by adjusting relations between experts, bureaucrats and interest groups. Ruiter (Citation2019) reached similar conclusions for political group advisors highlighting that they engage in politically influential activity only to the extent to which they pursue the party group interest.

Attitudes

Another strand of literature looks at staff’s involvement given their attitudes and behaviour, mostly based on organisation theory. While the body of literature published by Neuhold and co-authors highlights the policy- and politics- conditions for bureaucratisation, Egeberg et al. (Citation2013) show that parliament’s organisation affects how staff perform their tasks. A concrete example involving Secretariat officials is provided in Kuehnhanss et al. (Citation2017), who found that higher levels of organisational identification translate into risk-averse behaviour where staff tries to minimise policy failures endangering the EP. One infers that changes to the organisation (e.g. strategies, missions statements, and career ladders) lead to changes in staff support. Consequently, organisational reforms inculcating administrators with mission statements emphasising responsiveness to political authority can minimise the negative effects of bureaucratisation (see Meier and O’Toole Citation2006, 10).

Scholars looking at staff’s sources of information and how these potentially impact the quality of advice provided to MEPs have also adopted an attitudinal inquiry line. Marshall (Citation2012) found that, as an information source, lobbyists undermine staff independence. Laurens (Citation2018, 138) concluded that consulting lobbyists provide staff with an overview picture that ultimately helps them devise compromises. Egeberg et al. (Citation2013, 510) reached similar conclusions, showing that political group advisors are more likely to pay attention to lobby groups and sectoral interests than party group officials who put the party line first (also Ruiter Citation2019, 15). Despite different attitudes towards information sources, Egeberg et al. (Citation2013, 511) conclude that both staff groups can provide professional advice, which can be politicised or non-politicised depending on MEPs’ requirements (Provan Citation2001; Winzen Citation2011). These studies show how attitudes such as inclination towards certain sources of information influence the unfolding of bureaucratisation and the type of support staff provide.

Descriptive representativeness

In a sociological study, Michon (Citation2014) looked at the personal capital of French parliamentary assistants. He found that they form an epistemic community with its own identity and norms of behaviour, hinting that bureaucracy can be an issue for democracy regarding staff descriptive (un)representativeness. Pegan (Citation2015, 192) observed that gender affects how staff perform some tasks, notably female staff report higher frequencies on administrative tasks and lower frequencies on policy-shaping tasks. On the other hand, Egeberg et al. (Citation2013) found little evidence supporting the hypothesis that staff’ s nationality, gender or education affect their decision-making behaviour. These studies are insightful insofar they give cues on staff’s descriptive nature. Unlike in North America, where research shows that race and gender contribute to the nature of advice staff provide (e.g. Wilson Citation2013), this inquiry line remains underdeveloped in Europe.

Summing up, the literature has mainly concentrated on studying political-bureaucratic relationships given task delegation and attitudes. These are two of the images through which bureaucratisation manifest itself. Other possible indicators remain unexplored, including the rate of personnel circulation between political and administrative careers (cf. Alexander Citation2020) and the intensity of partisan appointments (Torstendahl Citation2001). Moreover, most of the studies focus on the post-Lisbon era, neglecting past developments. The following section introduces a temporal perspective to the study of administrative structures in the EP.

A temporal perspective

This article leans on historical institutionalism to bring temporality at the centre of the research investigation of EP’s administrative-bureaucratic structures. The guiding assumption is that events that have shaped the EP into a legislature are connected to changes in the EP’s administrative-bureaucratic organisation. Most of the recent research holds such an assumption but has focused on the Lisbon Treaty changes. For example, Coremans and Meissner (Citation2018) explored the EP trade committee’s policy capacity before and after the Lisbon Treaty. Dobbels and Neuhold (Citation2013) hypothesised that the Lisbon Treaty would increase Secretariat officials’ importance in policy-making. In common with this literature, the article builds on the assumption that the EP’s parliamentarisation has affected administrative structures and explores the effects of other events besides the Lisbon Treaty.

The purpose is to observe how the EP’s bureaucracy developed formal attributes (e.g. organisation, recruitment and working conditions; see Egeberg et al. Citation2013) given EP’s parliamentarisation starting from the 1950s when the EP’s predecessor was established. Parliamentarisation stands for the formal institutionalisation of the EP as a legislature through the gain of representative, budgetary, scrutiny and law-making functions (Rittberger Citation2012). The EP exercised some of these functions already in the 1950s (i.e. the control, deliberation and consultative roles), but a ‘push’ towards a legislature happened in the 1970s when it obtained budgetary powers and European elections made possible direct citizen representation. Other moments in the EP’s parliamentarisation can be identified in the introduction and the extension of decision-making procedures.Footnote1 These events are treated as critical junctures or opportunities for generating change.

In historical institutionalism, preferences are historical products, meaning that past developments influence present choices (Pierson Citation2000; Thelen Citation2003). From a historical-institutionalist perspective, starting arrangements are particularly relevant because they can be historically foundational, initiate path-dependency and lock-in future developments (Orren and Skowronek Citation1994; Pierson Citation2000). In this interpretation, when rather than what has happened is critical for the evolution of an institution. The EP’s foundational period has provided specific conditions for the organisations of administrative-bureaucratic structures. In the absence of permanent MEPs, the EP’s Secretariat operated relatively unchecked and had the opportunity to develop leeway from MEPs’ control, which could affect the balance between the different sources of administrative support in parliament (Camenen Citation1995; Costa Citation2003).

Theorising change

To explain how parliamentarisation might have impacted administrative-bureaucratic structures since the foundational period, it is useful to turn to the writings on the temporal separation between causes (parliamentarisation) and outcomes (changes to administrative structures and bureaucratisation) (Pierson Citation2003). Temporal separation means a time separation between the onset of a cause and the main effect’s development with changes occurring at different speeds or sequence.

Analyses based on historical institutionalism predict that change results from continuous processes or after a build-up of stress to a critical level that punctuates a stability period or equilibrium. In a continuous process, changes are incremental and cumulative over time, introduce partial alternations to existing institutions without replacing old ones (Schickler Citation2001). These outcomes consolidate an institution through a logic of increasing returns to an initially set path. Gradual change can also occur through conversion, where existing institutions are altered to serve new purposes (Thelen and Mahoney Citation2010). In the event of critical junctures, change can be rapid and highly visible (i.e. the threshold effect model), or it can occur with some distance from the tipping point (i.e. casual chain model) (Jervis Citation1997). In the latter scenario, changes are perceived as unintended or by-products because they have not been (rationally) planned by those implementing and planning a process or event. While critical junctures break stability periods, they can induce path-dependent processes where outcomes triggered by a process at one point in time reinforce themselves as times goes by from the original event (Collier and Collier Citation1991).

Building on the temporal separation between causes and outcomes, the question is, how has parliamentarisation changed administrative structures set in the 1950s: Did administrative structures change promptly, breaking path-dependency or have they changed incrementally following parliamentarisation?

Theorising democratic consequences

Events shaping the EP into a legislature have foremost targeted the EU’s political workings. They have influenced how the EP organises its political structures, for instance, the competence division among committees. As a matter of functionality, one would expect administrative-bureaucratic changes to parallel the course of EP’s political workings. One benefit of such development is that political and administrative-bureaucratic structures work in tandem, where the latter ideally support EP’s political capacity to strengthen democratic government. However, a historical-institutionalist explanation predicts that political and administrative institutions can follow different evolutionary paths creating a time gap between outcomes. As Orren and Skowronek (Citation1994, 321) explain, institutional arrangements are underpinned by different temporal orders and change because they are bound up with what goes on in other institutions. To theorise such an alternative, the article adopts a layered view of institutions, where institutions are made of arrangements which (can) operate following different logics and abrade on one another (Orren and Skowronek Citation1994).

Applied to this article, the EP’s institutional order is conceived as the ensemble of EP’s political structures (e.g. committees, party and MEPs) and administrative-bureaucratic structures (Secretariat, party group and MEPs staff). Following Orren and Skowronek (Citation1994, 321), institutional arrangements such as the EP are underpinned by different temporal orders, meaning that EP’s political and bureaucratic arrangements have their own histories, change at different times and varying rates. Building on this assumption allows asking how has parliamentarisation shaped bureaucratisation or the relationship between political and administrative-bureaucratic structures to learn about the effects on democratic government.

Summing up, based on historical institutionalism, the article assumes that parliamentarisation shaped the EP’s administrative-bureaucratic organisation either incrementally (path-dependency explanation) or transformationally (punctuated equilibrium explanation). Adopting a layered view of institutions, it is assumed that different temporal orders underpin political and administrative-bureaucratic structures. The latter permits discussing administrative-bureaucratic changes and bureaucratisation in the context of democratic government.

Data

The article builds on interviews, primary and secondary resources. To avoid self-selecting evidence, which is sometimes present in political science research leaning on history (Kaiser, Leucht, and Rasmussen Citation2009), resources are corroborated whenever possible. Among primary resources, I consulted the annual budgets of the EC/EU and EP reports. For earlier accounts on staff support structures, I draw on reports with archival data (e.g. Piodi Citation2008). Semi-structured interviews with eleven individuals were conducted in 2012, 2013 and 2015 (listed at the end). Respondents included two secretary generals, four directors, two middle managers, one high official of a political group and two parliamentary assistants. Three respondents listed as employees in the EP Secretariat had also worked in political groups. Three respondents were retired. All the others were in EP’s active service, except for one who worked in the European Commission. The respondents were selected considering their experience, long-term career in the EP and snowballing. Interview data were analysed with content analysis.

EP administration

The following section presents the EP’s administrative arrangements from the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) until the establishment of the Directorate-General for Research (DG EPRS) in 2014. The ECSC is treated as the foundational period with several contingencies for organising administrative-bureaucratic structures. The choice in the period is assumed to have impacted any future developments following parliamentarisation.

Foundational period

Two ideas circulated for the administrative organisation of the Common Assembly in the 1950s (Guerrieri Citation2008, 191). One solution predicted that the administration of the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe would become the administration of the ECSC Common Assembly. A second solution envisaged creating a separate administration, which could be either temporarily seconded from national institutions or permanent. The outcome was a compromise, as seen in the High Authority, which included intergovernmental and supranational aspects of administrative organisations (Seidel Citation2010, 9).

The intergovernmental aspect consisted of a temporary service of clerks seconded from national parliamentary administrations every time the Common Assembly was in session. By 1957, 101 officials were seconded from national parliaments for meetings in Strasbourg (Piodi Citation2008, 14). These temporary clerks took care of running sessions, minutes and stenographic services (Guerrieri Citation2008, 850). In addition, every national delegation received support from their respective national parliaments, which is a common practice for inter-parliamentary assemblies.

In 1953, the Common Assembly agreed on the employment of the first permanent staff and the basic conditions for its Secretariat’s workings (Guerrieri Citation2008, 191, Citation2012, 849). By the end of the ECSC, 132 permanent staff were employed in four services: committees, studies, information and documentation, general services and administration (Piodi Citation2008, 17). The number of staff began to swell, while an immutable number of representatives (78) met between once and five times a year. The supranational organisation also included political group secretariats, which were financed from the Assembly’s budget (Guerrieri Citation2015, 395; Krumrey Citation2018, pp. 124–125). This was a departure from previous practices in inter-parliamentary assemblies in which delegations were assisted by national parliamentary administrations, and added to the parliamentary administrative organisation of the ECSC.

Changes to EP administrative structures

By the 1970s, the EP administrations underwent a series of changes. With the adoption of the Staff Regulation in 1956, a permanent European civil service was institutionalised (Page Citation1997, 7; Seidel Citation2010, 30–31). The regulation was reformed for the first time in 1962 to regulate the employment of temporary staff, which formalised the position of political group employees. Following the Rome Treaty, the Secretariat was restructured from four into five services (Piodi Citation2008, 16–17), which persisted until the reform Rising the game in 2003 (Kungla Citation2007).

Parliamentary reports received limited attention from members, which gave administrators leeway (CitationInterviews A; CitationB; CitationC; CitationF; CitationG; Camenen Citation1995; Costa Citation2003; Guerrieri Citation2012, 850). For instance, the former Secretary-General Priestley reminisced: ‘I remember a time before 1979 when the Secretariat was writing the reports, and you were lucky if the members read them’ (CitationInterview A). Different reasons can explain the relative autonomy that administrators exercised in the period before 1979. For one, the Secretariat’s autonomy stemmed from the physical absence of members with a dual representative mandate in national parliaments and the EP. Some MEPs had a low interest in European affairs, limited ambition to control an organisation’s service, which had little formal power to influence the EU or did not have the expertise to engage in the technical matters put forward to the Assembly. Former Secretary-General Vinci, who started his career in the EP in the 1960s as a junior official in the committee for public health, remembered that members had very limited knowledge on the technical aspects of the Community policies (CitationInterview C):

Economic integration involved some difficult technical aspects. The parliamentarian had great difficulties in understanding these technicalities. When the Common Agriculture Policy became operational [1962], common prices had to be fixed. Who knew how to do it? The parliamentarian had no idea, and it was the official, whose advantage was to be a technician, that knew what common prices meant. The European officials, who stayed in Luxembourg 365 days a year, knew much more than parliamentarians, who came to the EP for five weeks per year. And because many things were being done on a technical level, there was less politics and members were less interested in the Communities.

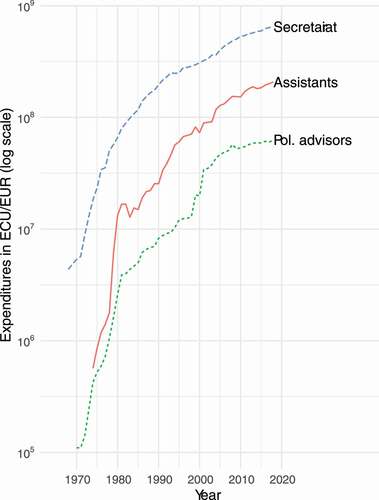

The EP Secretariat’s importance can also be explained by the relative weakness of political group staff and MEPs parliamentary assistants. Financial resources for these administrative structures were comparatively low to the Secretariat until the first direct elections (). While the Secretariat employed at least two officials per committee, most political groups’ advisors worked concurrently in more than one committee ().

Table 1. Number of staff per committees in 1977

In contrast, Secretariat’s committee services were established already in the 1950s, which allowed administrators to gain and accumulate technical and policy knowledge that is today associated with the production role of committee staff (Guerrieri Citation2012, 850). For example, in some cases, such as setting agricultural prices, the policy was technical, and Secretariat staff took a steering role (CitationInterviews C; CitationG). On salient issues such as the Community budget, where the EP’s control functions increased substantially in the 1970s, Secretariat staff played at least a production role drawing up documents (CitationInterview A; CitationC; CitationD; Priestley Citation2008, 13). The adoption of two budgetary treaties directed a significant amount of human resources towards the Budgets committee’s staffing, which in 1977 included seven administrators (). On the other hand, the staff of other committees ranged from two to five administrators.

‘A moment of disorientation’

The first direct elections in 1979 and the formal legislative empowerment of the EP that took off in the 1980s were expected to affect the delivery and nature of support from unelected officials (CitationInterviews E; CitationI; Provan Citation2001). With directly elected MEPs and a larger quantity of work with possibilities to impact legislation, a democratically accountable parliament required less administrative initiative and more interest and awareness from MEPs to draft legislation (CitationInterviews B; CitationE; CitationG; CitationI). For instance, Pier Virgilio Dastoli, parliamentary assistant to MEP Spinelli from 1977 to 1986 and subsequently temporary agent in the EP, witnessed this evolution (CitationInterview E):

From the moment the EP acquired a legislative role, the officials of the parliament had to change the way they were working. With the Single [European] Act, the cooperation procedure, the Maastricht Treaty and all subsequent treaty changes the work of the members and officials became more detailed from the point of view of legislation. Therefore, we [officials] could no longer allow ourselves to have a fantasy approach. The texts that we were writing were texts that later on were transformed into law.

However, the Provan report in the early 2000s signalled that legislative assistance was not keeping pace with parliament’s evolution (Provan Citation2001, 4). Support for MEPs required a clearer ‘distinction between the political sphere (occupied by group staff and members’ advisors) and a high-quality and non-partisan civil service (secretariats, research services, legal advisors)’, which would make the democratic control over the bureaucracy easier to attain (Provan Citation2001, 10). For instance, a Secretariat official recounted the situation reigning in the EP in the 1990s in the following manner (CitationInterview I):

After parliament had acquired new functions, there was a moment of disorientation. The members needed some time to adapt. Then, the parliamentarians started to take political initiatives as it was their right. And maybe when they did, there was a disconnection with respect to the Secretariat. The Se cretariat was destabilised, and as a result, it did not provide the immediate technical support, which was needed. But this lasted for a very short time because then it became clear that the Secretariat was to follow the members’ political initiative and offer them duly and immediate assistance.

Modernisation

The Provan report highlighted the changing nature of the EP into a legislature required from the Secretariat to strengthen its reputation of high-quality and non-partisanship (Provan Citation2001, 5). Addressing issues in the Provan report proceeded incrementally over a long period starting in 2003 with the reform ‘Rising the game’ (Kungla Citation2007). The reform united under the same directorate procedural and research services for committees, following a policy domain organisation. For example, nowadays, the directorate covering economic policies consists of committee secretariats and a unit responsible for studies in the economic policy domain. Secretariat’s support for committees was streamlined as procedural and research support are since then provided from Brussels.Footnote2 A decade after Rising the game, the new Directorate-General for Research (DG EPRS) was set up in 2014. Among its duties, was also the assistance of individual members (European Parliament Citation2013, 13–14 CitationInterview H).

The latest changes to the administrative support system are about parliamentary assistants. In 2001, the Provan report recommended that MEPs view parliamentary assistants as political advisors (Provan Citation2001, 4, 8–9). While MEPs received an allowance for individual assistance since 1974, parliamentary assistants’ role developed towards an administrative rather than a political one. Even when the allowance for personal assistance increased, their posts remained less prestigious than positions in the Secretariat and political groups because they were not formalised in the Staff regulations (CitationInterviews J; CitationK). The integration of personal assistants in the Staff regulations was put on the agenda in 1998, 2001 and 2008, when an assistant statute was finally agreed upon. Alongside the set-up of DG EPRS in 2014, this was important for guaranteeing legislative assistance to individual members compared to collective bodies (e.g. committees and political groups). Since 2008, the EP has been incrementally changing rules for the recruitment of assistants also to respond to media criticism of the transparency of information (CitationInterview K; OCCRP Citation2015).

Overall, parliamentary assistants’ growing profile has raised concerns among political groups over their primacy in providing legislative and political support. These concerns relate to the traditional nature of representation in Europe, where political groups are a source of political stability, policy-making and linkage between elites and citizens. Consequently, attempts to strengthen the organising abilities of MEPs beyond the party group can be interpreted as weakening the traditionally strong functions of parties in Europe (CitationInterview J).

These ‘anxieties’ pale to some extent when looking at the recruitment of senior officials in the Secretariat from political groups’ lines, which can be seen to strengthen party groups (CitationInterview C). Indeed, by the late 1990s, ‘politically tainted’ recruitment became apparent at the level of the EP’ s Secretary-General and to some extent the Director-General and Director level (Camenen Citation1995, 149; Guerrieri Citation2012, 853; CitationInterviews C; CitationG). Four of the previous five Secretaries-General had occupied the post of Secretaries-General in a political group, and the last three had also served in an EP’s presidential cabinet. This type of politicised career was, for instance, described by a respondent (CitationInterview G):

In the 1980s, political groups were increasingly saying: “Careful, we need to be aware that there is a political split there and we cannot leave these tasks to apolitical administrators in the parliament. We want to have our own people in the administration.” So, in the beginning of the 1990s political groups became directly osmosing into the administration. As long as they had a certain amount of years and qualifications, they could just move. So a person working for a political group would move to the Secretariat.

While several appointments in the Secretariat have a political character, some respondents believed that politicised recruitment does not automatically favour one political group over another (CitationInterview A; CitationJ). With some uncertainty over the consequences of such appointments, this is an area that might generate changes in the future. Admittedly, the Provan report recommended that movement from one administrative structure to another should entail a ‘one-way ticket’ (Provan Citation2001, 10). However, this recommendation has not so far appeared in the Staff Regulations.

Genesis, change and historical institutionalism

In the model of representative democracy, the process of governance is unattainable without administrators or a bureaucracy. One challenge facing democratic institutions such as the EP and their political leaders is establishing administrative autonomy and strengthening administrative capacity so that administrations remain adept in the face of new challenges. Another one is to control the bureaucracy so that administrators do not replace democratically chosen representatives but become a source of political strength. The division of responsibility between political and administrative structures is key to the quality of democracy but subject to evolving processes and events that disturb any balance previously attained.

The foundational period of the EP during the ECSC set the conditions for the development of administrative structures as the EP acquired the competences of a legislature. The initial organisation included temporary (seconded) services from national parliaments, permanent Secretariat services and party group secretariats. Considering that one of the contingencies involved an administrative organisation under the Council of Europe, the Secretariat guaranteed the EP independent administrative capacity, which ensured autonomy from other institutions already in the beginning.Footnote3 Administrative autonomy was further strengthened when seconded services from national parliaments were replaced with permanent Secretariat services. The foundational period can broadly be considered as setting a path towards EP’s administrative autonomy as a parliament.

While the EP exacted administrative autonomy through the Secretariat’s services already in the 1950s, it spent far more time developing autonomous capacity for its various political structures, namely committees, political groups and individual MEPs. Moreover, changes were not always timely, meaning they occurred with some distance from the critical events defining EP’s formal parliamentarisation. The case of the Secretariat and the development of a pluralistic market of support illustrate this point. While the organisation of the Secretariat kept pace with the introduction of budgetary prerogatives in the 1970s, it no longer provided the expected assistance following the EP’s legislative empowerment in the late 1980s and 1990s. Indeed, interview respondents described a ‘moment of disorientation’ between MEPs’ needs and the support they received. Solutions to weaknesses concerning research and legislative support in the Secretariat were implemented incrementally over two decades, starting in the early 2000s with Rising the game and continued in the 2010s with the modernisation of research services.

Another example showing the discontinuity of administratisinceve organisation from EP’s formal parliamentarisation and development of its political structures is the development of pluralistic sources of administrative support within parliament. Unlike executive administrations, which serve one political master, parliamentary administrations serve members from different political leanings. Setting up Weberian conditions for impartial and neutral services, such as the one for the EP’s Secretariat, is one element providing fair support in parliament. Making available resources for assistance in the manifestation of party group secretariats and personal assistants on an equal basis is another element since these structures provide different-natured advice to MEPs than the Secretariat. Today, the EP is serviced by various well-resourced administrative support structures: the Secretariat, party group staff and MEPs’ personal assistants. However, the development of a pluralistic market of staff support within parliament occurred incrementally and was discontinued from EP’s formal parliamentarisation. Indeed, neither direct elections nor treaty changes appear to be directly associated with party group secretariats and assistants’ reforms. While political groups developed their secretariats from the very beginning guaranteeing support for MEPs groups, personal staff became a relevant source only later.

While incremental, changes to the Secretariat and the diversification of staff structures professionalised the EP administrative-bureaucratic organisation and strengthened EP’s administrative capacity. Today, the EP is among the best-resourced parliamentary administrations worldwide alongside the US Congress. The Secretariat’s reform and the consolidation of a pluralistic market of staff support can be seen as a continuation of early efforts establishing the EP’s autonomy insofar they have upgraded the EP’s autonomy vis-a-vis other institutions with internal autonomy whereby all political actors are appropriately resourced.

The delayed response to EP’s parliamentarisation was not detrimental to the EP’s exercise of democratic control over its bureaucracy. When bureaucratic-administrative structures reformed, changes accommodated the preceding shifts in the political climate, meaning that parliamentarisation as an exogenous event has had a marked, albeit delayed, effect on bureaucratisation. Since changes to the political order preceded modifications to the administrative one, the sequence was favourable for the exercise of democratic control over the administration. Concerning administrative capacity, reforms created some tensions between administrative structures. For instance, the set-up of a directorate-general for research and the statute for parliamentary assistants emphasise support for MEPs as individuals over their collective membership in political groups. According to some interviews, empowering individual MEP over collective bodies, such as political groups, can disrupt the representative model of democracy, where parties carry important linkage and policy-making functions. The outstanding question is whether a timely adaptation of research services and individual MEP support services would have eased some of these tensions or whether these tensions are inevitable and part of a democratic system.

Overall, the early EP’s period set its administrative organisations on a path towards a parliamentary model guaranteeing administrative autonomy from outside organisations. Later changes were incremental and built EP’s internal administrative capacity for committees, party groups and MEPs. Changes were path-dependent since they enhanced the EP’s autonomy vis-a-vis other institutions with internal autonomy where all political actors are appropriately resourced.

Conclusion

Following the Lisbon Treaty, several researchers have turned to analyse the role of administrative players in the parliamentary context of the EU. This article has also looked at administrative-bureaucratic structures but adopted a temporal perspective. It has theorised the temporal connection between the EP’s formal developments into a legislature and outcomes connected to administrative structures: the staff of the Secretariat, political groups, and MEPs’ offices. In addition, this article theorised that administrative and political structures follow different evolutionary paths with consequences for democratic government.

The findings show that the EP’s formal empowerment required time to affect the EP’s administrative structures but that incremental changes followed a path towards administrative autonomy and capacity. The recast of administrative structures, which has not always been timely with the EP’s parliamentarisation, has not affected the legitimacy of administrative actions. The analysis also showed that the diversity of administrative structures helps keep a balance between elected and non-elected officials and is a source of democratic control.

The article followed the formal development of powers conferred to the EP by treaties. Historical accounts show that the EP played a symbolic power and used its competences ingeniously even when it was formally a weak player among EU institutions. Therefore, when exploring bureaucratisation, we would benefit from studies applying theory to cases when the EP and its leadership attempted to exert influence outside their formal means and the role of administrative players in these events. The relative importance of treaties and procedures under which the EP operates could equally be put under consideration. In theoretical terms, this means there is a need to problematise the critical junctures in the EP’s parliamentarisation.

Finally, this article’s empirical part suggests that temporal order theorisation can be enriched with other approaches to institutional theory. For instance, the forming period of ECSC in the early 1950s and the EP’s development of administrative structures following models seen in parliamentary systems is a good laboratory to test sociological institutionalism assumptions such as isomorphism and rational choice ideas of functional adaptation. Similarly, we would enrich our understanding of the balance between the Secretariat, political group secretariats and MEP personal staff by looking at rational choice explanations of bargaining. Given public opinion and media reporting, the latter appears to be the most interesting avenue for future research. In all cases, weaving institutionalists perspectives together will enrich our understanding of change and transformation. Therefore, further work should integrate questions on the nature of changes, their temporality, and underlying causes. Such questioning can lead us to examine exogenous events such as parliamentarisation and the turning points generated endogenously.

Acknowledgments

I thank Victoria Dear Tolmie.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Enlargements are not considered because they have neither altered the formal nature of representative democracy nor affected parliament’s formal organisation (e.g. Pegan Citation2017). Nevertheless, they are important for understanding the informal realms of organisations in terms of culture – an unexplored issue for the EP.

2. Before Rising the game, research units were based in Luxembourg, while committees and plenaries were in Brussels and Strasbourg, which led to a poorly visible research division (CitationInterview H).

3. See Trondal (Citation2017) for a discussion on autonomy and capacity.

Interviews

- Interview A (2012). Julian Priestley, EP Secretary General 1997-2007. Luxembourg, 11 October 2012.

- Interview B (2012). Guy Vanhaeverbeke, EP Honorary Director. Luxembourg, 14 October and 11 November 2012.

- Interview C (2012). Enrico Vinci, EP Secretary General 1986-1997. Luxembourg, 21 October 2012.

- Interview D (2012). Theo Junker, EP Honorary Director. Luxembourg, 23 October 2012.

- Interview E (2012). Pier-Virgilo Dastoli, Assistant to Altiero Spinelli and Former EP Secretariat Staff. Brussels, 19 November 2012.

- Interview F (2012). EP Official and Former Group Advisor. Brussels, 6 December 2012.

- Interview G (2013). Micheal Contes, MEP Assistant. Brussels, 18 September 2013.

- Interview H (2013). Alfredo De Feo, EP Director. Brussels, 19 September 2013.

- Interview I (2013). EP Official and Former Group Advisor. Brussels, 12 November 2013.

- Interview J (2013). Robert Fitzhenry, EPP Head of Communication, 20 September 2013.

- Interview K (2015). EP Director. Brussels, 22 April 2015.

References

- Aberbach, Joel, Robert D. Putnam, and Bert Rockman. 1981. Bureaucrats and Politicians in Western Democracies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Alexander, D. A. (2021). The Committee Secretariat of the European Parliament: administrative mobility, expertise and keeping the legislative wheels turning. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27(2), 227-245.

- Camenen, François-Xavier. 1995. “Administration et autorité politique au Parlament Européen.” Revue française d’administration publique 73: 143–155.

- Collier, Ruth B., and David Collier. 1991. Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Coremans, Evelyn, and Katharina L. Meer. 2018. “Putting Power into Practice: Administrative and Political Capacity Building in the European Parliament’s Committee for International Trade.” Public Administration 96 (3): 561–577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12400.

- Costa, Olivier. 2003. “Administrer le Parlament européen: Les paradoxes d’un secrétariat général incontrournable, mais faible.” Politique européenne 11 (3): 143–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/poeu.011.0143.

- Dobbels, Mathias, and Christine Neuhold. 2013. “The Roles Bureaucrats Play: The Input of European Parliament (EP) Administrators into the Ordinary Legislative Procedure: A Case Study Approach.” Journal of European Integration 35 (4): 375–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2012.689832.

- Egeberg, Morten, Å. Gornitzka, J. Trondal, M. Johannessen et al. 2013. “Parliament Staff: Unpacking the Behaviour of Officials in the European Parliament.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (4): 495–514. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.718885.

- Ellinas, Antonis, and Ezra Suleiman. 2012. The European Commission and Bureaucratic Autonomy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- European Commission. 2018. Europeans and the EU Budget. Standard Eurobarometer 90. Luxembourg: European Commission.

- European Parliament. 1977. Directory of the Departments and Political Groups of the European Parliament. Luxembourg: Secretariat of the European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2013). Parliamentary Democracy in Action. 15 January 2014. URL: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/the-secretary-general/resource/static/files/2013/parliamentary-democracy-in-action–en—-summary.pdf.

- European Parliament (2020). Assistants. 15 May 2020. URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/assistants?letter=Z&name=&assistantType=&searchType=BY_ASSISTANT.

- European Union (2020). Definitive Adoption of the EU’s General Budget for the Financial Year 2020. Official Journal of the European Union, L 57, 27 February 2020.

- Guerrieri, Sandro. 2008. “The Start of European Integration and the Parliamentary Dimension: The Common Assembly of the ECSC (1952-1958).” Parliaments, Estates and Representation 28 (1): 183–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02606755.2008.9522283.

- Guerrieri, Sandro. 2012. “Una Burocracia Parlamentaria Supranacional: La Secretaria General Del Parlamento Europeo (1952-1979).” In Las Cortes de Cádiz y la Historia Parlamentaria, edited by Repeto D. García, 845–856. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz.

- Guerrieri, Sandro. 2015. “The Genesis of a Supranational Representation. The Formation of Political Groups at the Common Assembly of the ECSC, 1952-1958.” In European Parties and the European Integration Process, 1945-1992, edited by Lucia Bonfreschi, Giovanni Orsina, and Antonio Varsori, 393–410. Brussels: Peter Lang.

- Högenauer, Anna-Lena, Christine Neuhold, and Thomas Christiansen. 2016. Parliamentary Administrations in the European Union. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jervis, Robert. 1997. System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kaiser, Wolfram, Brigitte Leucht, and Morten Rasmussen. 2009. The History of the European Union. New York, London: Routledge.

- Krumrey, Jacob. 2018. The Symbolic Politics of European Integration. Cham: Palgrave.

- Kuehnhanss, Colin R., Z. Murdoch, B. Geys, B. Heyndels et al. 2017. “Identity, Threat Aversion, and Civil Servants’ Policy Preferences: Evidence from the European Parliament.” Public Administration 95 (4): 1009–1025. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12348.

- Kungla, Tarvo. 2007. “Rising the Game: Administrative Reform of the European Parliament General Secretariat.” In Management Reforms in International Organizations, edited by Michael W. Bauer and Christoph Knill, 71–85. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Laurens, Sylvain. 2018. Bureaucrats and Business Lobbyists in Brussels. London: Routledge.

- Marshall, David. 2012. “Do Rapporteurs Receive Independent Expert Policy Advice? Indirect Lobbying via the European Parliament’s Committee Secretariat.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (9): 1377–1395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.662070.

- Meier, Kenneth J., and Laurence J. O’Toole. 2006. Bureaucracy in a Democratic State. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Michon, Sébastien. 2014. Les équipes parlementaires des eurodéputés. Paris: Larcier.

- Neuhold, Christine, and Mathias Dobbels. 2015. “Paper Keepers or Policy Shapers? the Conditions under Which EP Officials Impact on the EU Policy Process.” Comparative European Politics 13 (5): 577–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2014.7.

- Neuhold, Christine, and Elissaveta Radulova. 2006. “The Involvement of Administrative Players in the EU Decision Making Process.” In EU Administrative Governance, Ed. by Herwig C. H. Hofmann and Alexander H. Türk, 44–73. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Neunreither, Karlheinz. 2002. “Elected Legislators and Their Unelected Assistants in the European Parliament.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 8 (4): 40–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330200870004.

- OCCRP (2015). Journalists Sue European Parliament in Historic Freedom of Information Drive. 13 December 2015. https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/4622-journalists-sue-european-parliament-in-historic-freedom-of-information-drive-2.

- Orren, Karen, and Stephen Skowronek. 1994. “Beyond the Iconography of Order: Notes for a “New Institutionalism”.” In The Dynamics of American Politics, edited by Lawrence C. Dodd and Calvin Jillson, 311–330. Boulder: Westview.

- Page, Edward C. 1997. People Who Run Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Page, Edward C., and Linda Wouters. 1994. “Bureaucratic Politics and Political Leadership in Brussels.” Public Administration 72 (3): 445–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1994.tb01022.x.

- Pegan, Andreja (2015). ‘An Analysis of Legislative Assistance in the European Parliament’. PhD thesis. University of Luxembourg.

- Pegan, Andreja. 2017. “The Bureaucratic Growth of the European Union.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 13.2: 1209-1234.

- Peters, B. Guy. 2015. “Policy Capacity in Public Administration.” Policy and Society 43.3-4: 219–228.

- Pierson, Paul. 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011.

- Pierson, Paul. 2003. “Big, Slow-Moving, and … Invisible.” In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer, 177–207. New York: Cambridbe University Press.

- Piodi, Franco. 2008. The European Parliament 50 Years Ago. Luxembourg: European Parliament.

- Priestley, Julian. 2008. Six Battles that Shaped Europe’s Parliament. London: John Harper Publishing.

- Provan, James. 2001. Legislative Assistance to Members - a Rethink. PE 309.022/BUR/REV. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Rittberger, Berthold. 2012. “Institutionalizing Representative Democracy in the European Union: The Case of the European Parliament.” Journal of Common Market Studies 50: 18–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02225.x.

- Romanyshyn, Iulian, and Christine Neuhold. 2013. “The European Parliament’s Administration: Between Neutral and Politicised Competences.” In Civil Servants and Politics. A Delicate Balance, edited by Christine Neuhold, Sophie Vanhoonacker, and Luc Verhey, 205–228. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruiter, Emmy (2019). ‘The Politics of Advice in the European Parliament: Understanding the Political Role of Group Advisors’. PhD thesis. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20190313er.

- Schickler, Eric. 2001. Disjointed Pluralism: Institutional Innovation and the Development of the U.S. Congress. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Seidel, Katja. 2010. The Process of Politics in Europe: The Rise of European Elites and Supranational Institutions. London: Tauris.

- Sewell, William H. 1996. “Three Temporalities: Toward an Eventful Sociology.” In The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences, edited by Terrence J. McDonald, 245–280. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Thelen, Kathleen. 2003. “How Institutions Evolve.” In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer, 208–240. New York: Cambridbe University Press.

- Thelen, Kathleen, and James Mahoney. 2010. “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change.” In Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, edited by Kathleen Thelen and James Mahoney, 1–37. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. 2001. “History of Bureaucratization and Bureaucracy.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, 1410–1415, Amsterdam, Oxford and Waltham: Elsevier.

- Trondal, Jarle. 2017. “The Rise of Independent Supranational Administration: The Case of the European Union Administration.” In The Rise of Common Political Order, edited by Jarle Trondal, 69–91. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Wilson, Walter C. 2013. “Latino Congressional Staffers and Policy Responsiveness: An Analysis of Latino Interest Agenda-setting.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 1 (2): 164–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2013.785959.

- Winzen, Thomas. 2011. “Technical or Political? an Exploration of the Work of Officials in the Committees of the European Parliament.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 17 (1): 27–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.545177.