ABSTRACT

COVID-19 is regarded as a major driver for digital transformation of our society and potentially as a boost for further digital single market integration. From the current perspective, pandemics cannot be avoided, but fully enabled digital societies will be better prepared to cope with them in future. This will, however, require reliable digital infrastructures to be put in place and further developed. Member States of the European Union and the European Commission have worked for more than 30 years to realise a European Digital Single Market. One key element in this development has been the so-called ‘Large-Scale Piloting’ (LSP) approach. This paper will focus on implementation of the ‘Once-Only Principle’ Pilot (TOOP) as part of LSP and the adjoint Single Digital Gateway Regulation (SDGR). This paper will examine whether, and how these initiatives can foster further integration into a digital single market.

1 Introduction

As if looking through a magnifying glass, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for a fully functional European Digital Single Market (DSM). The latest development in this field is the concept of implementation of a ‘Digital Green Pass’ within the EU. This was described by Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel as an outcome of the discussion between leaders of the EU during the Summit of the European Council on 25/26 February 2021. Further details of the proposal for a Digital Green Pass were presented by the EC in March 2021. ‘The aim is to provide: (1) Proof that a person has been vaccinated, (2) Results of tests for those who could not get vaccinated yet, (3) Information on recovery from COVID-19. It will respect data protection, security & privacy. The Digital Green Pass should facilitate easier everyday lives for Europeans. The aim is to gradually enable them to move around safely in the European Union or abroad – for work or for tourism’ (Ursula von der Leyen, Citation2021).

This is a good example for emphasising that challenges for the DSM are manifold: political, legal, and technical. The Digital Green Pass that will become a Digital Green Certificate (European Commission , Citation2021c) foresees the need for (1) A common legal framework, (2) Mutual recognition of certificates across the EU, (3) Technical solutions on a national level to ensure functioning of such certificates, and (4) Alignments with data protection requirements. It therefore touches on all aspects relating to full implementation of the DSM. The challenges for accomplishing the DSM are linked to organisational, technical, legal issues, and to trust. These aspects are not unique for the DSM and are rooted in early stages of the common market of the EU (European Commission , Citation2021c).

The transition of the European Single Market into a Digital Single Market (DSM) became a core element of the political agenda of the European Commission (EC) over the last decade. The aim of which is to create a digital eco-system driven by services, citizens and businesses in a cross-border context in Europe. Several initiatives to support the agenda were started by the European Commission, Member States, and associated countries due to changing priorities at different political levels. In this paper, we will highlight weaknesses relating to the DSM, ESM, and more specifically related to the SDGR, the once-only principle (OOP), and options for improvement. A particular focus is set on technical and legal aspects, and on governance.

The DSM is one of the latest features of the ongoing digital transformation of the public sector, which not only provides for digitization but rather a radical, disruptive, experience for the otherwise rather path dependent civil service (Mergel, Edelmann, and Haug Citation2019). From changing the workforce through digital service teams (Clarke Citation2017), the way these teams work by changing from waterfall to agile collaboration methods (Dupont Citation2019) or ensuring in-house expertise with the correct mindset (Geraghty Citation2017) – while difficult on a national level, seems almost impossible in a context like the European Union.

The purpose of this paper is therefore an investigation of this Special Issue along the lines of the two hypotheses below, of:

H1: Existence of an institutionalised coordination body in hybrid multi-level governance architecture promotes resilience in or furthers EU single market integration.

H2: Presence of public-private interactions in hybrid governance architecture promotes resilience in or furthers EU single market integration.

In order to provide insights into these hypotheses with regard to digital aspects, we will examine the genesis of the European Digital Single Market. For this purpose, we consider relevant policy documents, high-level political declarations and most significantly, their implementation in so-called Large-Scale Pilots, including the most recently completed project, The Once-Only Principle Project (TOOP).

This study was conducted in the form of participatory action research (Clark et al. Citation2020), which commenced in late 2015 with preparatory work for the TOOP large-scale pilot within the framework of the EGOV Action plan steering group. Launching this project became possible, as the need to provide for integrated digital public services across European borders became apparent, in order to improve the poor ecosystem for the European Digital Single Market. The Estonian Ministry for Economy and Communication investigated the readiness for an external group of researchers at an Estonian university, to elaborate on how to build such an ecosystem on a pan-European level. This provided an ideal opportunity to study the genesis and integration of this new kind of Single Market.

Often, action-research is attributed and being less rigorous when it comes to scientific methodology, as it is driven by the context and its ‘applied’ nature (Davison, Martinsons, and Ou Citation2012), however, in turn, we also note that this makes it highly relevant and able to deliver new insights which otherwise would be hard to obtain (Baskerville & Myers Citation2004).

This method was selected, because action research relates to collaboration between researchers and members of organisations in order to solve organisational problems. The participative approach permits the involvement of action, evaluation, and reflection to implement changes in practice and is a good fit, together with piloting on a large scale. The observations and experiences were supplemented and triangulated with desk research. This desk research consisted of a literature review and analysis of a number of editions of the Eurobarometer (EB). As part of the desk research, the first outcome produced from the literature review was, that the number of scientific articles on the DSM is relatively low.

This paper has been set out as follows; following the introduction, first of all we present the background for the Digital Single Market. This contains a description of developments from the early stages of the European Union up until today, with a special focus on aspects of digital transformation. Secondly, we describe the specific approach of piloting on a large scale for a pan-European level and impacts on DSM. Finally, we provide analysis and conclusions based on the findings.

2 Digital single market – background

The Digital Single Market did not start from scratch. It is an essential part of the European Single Market, based on the four pillars of free movement; it allows goods, services, capital, and people to move between Member States. The coordination of the action plans is a good example of how an institutionalised coordination body has an impact on the execution of EU politics. As part of the analysis, we will show how the EC and Member States designed and shaped the DSM through setting up European action plans. During the 1990s, the European Commission and Member States recognised the importance of technological and digital developments. Therefore, preparation commenced for new online services. Starting by implementing Directive 1999/93/EC on a Community framework for electronic signatures , Citation1999). Next, the idea to support electronic and online services was picked up by the ‘eEurope 2002 Action Plan’ and ‘eEurope 2005 Action Plan’. These plans showed us that the attention of Member States but especially of the European Commission had shifted to aspects of digitalisation of the EU society. The focus of the action plans was to strengthen the digital infrastructure in Europe and increase potential users’ digital skills. Activities between the EC and the MS were coordinated via high-level groups. Besides this, the involvement of the EC pushed digitalisation ahead and ensured the continuity of the different action plans. The activities initiated by the plans created the basis for ‘eServices’ within the EU.

The next step occurred with the ‘i2010 eGovernment Action Plan’ of 2005, defining five primary objectives: (1) to provide trusted and innovative eGovernment services to all citizens and thus overcome ‘digital divides’, in an attempt to make digital Europe more inclusive; (2) to make these services effective and efficient; (3) to provide all public procurement online, and with 50% usage by 2010, which added an impact goal of having procurement available online; (4) to provide convenient, secure and authenticated online access, highlighting the need for secure identification; and (5) to strengthen democratic decision-making by using new ICTs.

The route to next steps into the Digital Single Market for the aforementioned plans was paved by the European Commission and Member States. The activities of the different parties were aligned by coordination in high-level group meetings. The plans were accompanied by ministerial declarations more than once. The 2009 ‘Malmö Declaration’ and 2010 ‘Digital Agenda’ were central elements to pushing digitisation of the EU further ahead. They established: (1) a plan to develop a digital single market; (2) enhanced interoperability and standardisation; (3) a new focus on creating trust and security; (4) high-speed and super-fast Internet access; (5) support for digital research; and (6) provisions for societal digital literacy. In general, we can conclude that one of the main aspects of these initiatives was setting up a cross-border and interoperable environment in Europe. In parallel, based on pilots on a large scale – initiated by the European Commission -, the EU facilitated the eIDAS Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23July2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC) passed in 2014.

This regulation, a key objective of the ‘2011–2015 eGovernment Action Plan’, replaced the ‘Electronic Signature Directive’ by incorporating citizen identification, electronic seals and thus providing a European framework for accepting and using foreign digital identities for citizens and businesses in cross-border eGovernment services (Krimmer and Webster Citation2021).

The ‘2017 Tallinn Declaration’ and the ‘2016–2020 eGovernment Action Plan’ fostered ongoing development of the ‘European Digital Single Market’. They enlarged the scope of the DSM by adding the OOP to the European digital landscape. Besides this, the coordination activities of EC and Member States already institutionalised were further formalised by setting up the ‘eGovernment Action Plan Steering Board’ in September 2016. The objective of the board is to Assist the Commission in relation to implementation of existing Union legislation, programmes, and policies; Assist the Commission in the preparation of legislative proposals and policy initiatives; Coordinate with Member States, exchange of views.

The Large-Scale Pilot TOOP (2017–2020) provides the technical infrastructure for trusted cross-border data exchange here, by implementing the so-called ‘Once-Only Principle’ (OOP). This principle essentially means that end-users, whether they are businesses or citizens, will not need to provide information more than once. There are two approaches to the OOP: (1) where a country implements it using a ‘tell us once’ approach, by sharing copies of the information with other government entities and thus avoiding multiple re-entries; and (2) where countries provide a data exchange layer where information is entered and also stored only once, resulting in this data being linked to only one authentic source rather than duplicate copies being made. Member States are committed to implementing the OOP principle nationally, and Article 14 of the Single Digital Gateway (SDG) regulation (, Citation2016) mandates a list of 21 services for both citizens and businesses that must be provided on a cross-border basis within the Digital Single Market (DSM) by the end of 2023. This requires heightened awareness of users and allocating new resources to overcome adoption barriers, let alone the need to comply with GDPR, which requires user consent for data collection and use.

This development was complemented and managed directly into the European Single Market (ESM) via legislative steps. The ESM is one of the critical elements of the European Union. Inspired by transformation of paper-based procedures and the general trend to design digital services, creating a European Digital Single Market (DSM) was the next logical step. The DSM was one of the core elements of Political Guidelines for the (European Commission Citation2015). Jean-Claude Junker said, ‘that we must make much better use of the great opportunities offered by digital technologies, which know no borders’ (European Commission Citation2014b, p. 7). The DSM became number 2 on the list of priorities for the European Commission. These priorities were picked up and continued by the next European Commission as part of its main concerns for 2019–2024. Furthermore, 14% of respondents in the questionnaire EB 500 named digital transformation of the economy and of society as one of the main challenges for the EU (QA 11, EB 94.1, Oct-Nov 2020).

Based on these goals, the EU recently launched essential integration initiatives to take steps towards the DSM in some specific areas of the single market. One of these areas is the field of services, on a national and especially on a supranational level. The intention is to engage public administrations on all levels, and to become more active in the use and provision of public services by digital means. With good reason, central public administrations are conservative by nature. Most public administrations are bureaucracies, and bureaucracies tend to resist change (Bannister Citation2001). As outlined by the previous Commission, the objective is to break up national or sectoral silos and create an integrated and interconnected version of the DSM. This also helped prepare us for the DSM.

To address the relevant aspects, this paper focuses on the Commission’s legislative act that aims to interconnect services on a national and European level. This is the Single Digital Gateway Regulation. Furthermore, it analyses the impact of projects initiated by the EC for development of the legal framework of the European Union and the digital future as it was described by the EC (see, by way of comparison, Paper 3 ‘Digital Single Market and the EU Competition Regime: An Explanation of Policy Change’ in this Special Issue and European Commission , Citation2021a). All these aspects together do the groundwork and build the conceptual framework for transforming the Single Market into the DSM.

2.1 Studying the digital transformation and creation of the digital single market

The programs and projects that were initiated pursued different goals. But there are common underlying themes and objectives, such as e.g. to speed up the digital transformation of European society with a particular focus on relevant e-Government aspects. E-Government presents a number of challenges for public administrators. Researchers proposed different models in their study of digital transformation, in an attempt to understand this process, including so-called stage models. The European Union has developed its own model, based on the traditional approach and further inspired by the SAFAD model (Statskontoret Citation2000) and experiences in the EU and Member States. The approaches of these models can be critically analysed from different angles (Meyerhoff Nielsen Citation2017) (Meyerhoff Nielsen, Citation2020).

Nevertheless, they provide an easy and descriptive way to understand these transformation processes. One very prominent concept was presented by Layne and Lee in 2001, and they clustered it into vertical and horizontal initiatives. Therefore, activities follow the traditional approach of four stages of a growth model for e-government: (1) cataloguing, (2) transaction, (3) vertical integration, and (4) horizontal integration. We will use this model, described along with further details in , to analyse transformation and integration into the DSM on a national and also an EU level.

Figure 1. Dimensions and stages of e-government development (Layne and Lee Citation2001).

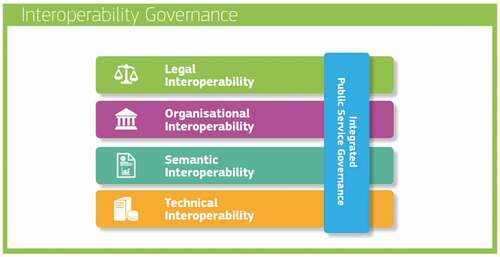

The EC launched the European Interoperability Framework (EIF) to ensure interoperability of the solution. As part of the EC funding programmes and adoption of the revised European Interoperability Framework in 2017, the EC addressed interoperability of public services at the EU level. The EIF is part of Communication (COM(2017)134) from the European Commission adopted on 23 March 2017. The EIF was undertaken in the context of the Commission’s priority to create a Digital Single Market in Europe (European Commission Citation2017). The EIF is designed in such a way as to give specific guidance on how to set up interoperable digital public services. It addresses interoperability issues on several layers, technical interoperability, semantic interoperability, organisational interoperability, legal interoperability, integrated public service governance, and interoperability governance. We can see how the different layers are interconnected with each other, in below:

Figure 2. Six Interoperability Layers – EIF (European Commission Citation2017).

The EIF is a particular kind of model that specifies the EC’s model presented for the EU in 2009, and further development of e-Government in the EU (European Commission Citation2012). It is based on experiences with the previous model and integrates not only technical but also policy and legal aspects and can therefore cover all kinds of cross-border and cross-sector aspects. This is a special case; most other approaches do not take these aspects into account and thus face organisational and/or legal issues during the implementation phase. The EIF can be viewed as stages of a development model that allows both top-down and bottom-up approaches. We must start bottom-up if the technical requirements are precise and the organisational, legal, and policy aspects can be defined during the implementation process. Firstly, top-down is only possible if the political and legal framework is set ahead of or at the latest during an early stage of the realisation phase. This option is a unique feature of the EIF. Therefore, the EIF model is a sound basis for developing digital services in Europe and beyond, where EU regulations, directives, or action plans often pave the way to new horizons. The EIF was used for several European projects, e.g. TOOP and e-SENS, to develop proper solutions and an architecture that is fitting for the expected results.

2.2 Description of different initiatives building the digital single market

A Digital Single Market can be understood as being an ecosystem in which citizens and businesses can assess online services under fair conditions for competition and personal data protection, irrespective of their nationality or place of residence (European Commission Citation2015). One of the barriers hindering development of the Digital Single Market is the lack of open and interoperable systems and services. Furthermore, most of the SMEs responding to questions in EB 486 (Q21, September 2020) named uncertainty about future digital standards as a barrier to digitalisation of their respective enterprise. Another issue the DSM must deal with, is the lack of trust between active data consumers and data providers. The analysis by Tkáč & Verner (2019) shows how perception of public services online is closely linked with recognition of trust-building mechanisms.

Besides this, there is a lack of common data portability infrastructures, as addressed in the Digital Market Strategy (Citation2015). One of the solutions of the EC suggested for overcoming these barriers, is to increase the number of online services. The requirements of businesses and citizens in cross-border settings can best be addressed by reusing existing building blocks of the Connecting Europe Facility programme, with further integration of existing platforms, portals, networks, and systems into one Single Digital Gateway (European Commission Citation2015).

The Single Digital Gateway Regulation coming into force had a significant impact on the DSM. It must be viewed as a game-changing event to implement cross-border services and the once-only principle in Europe. In addition, it created the legal framework for the OOP and set the timeframe for implementing it. Besides that, it addresses the issues and expectations of European citizens and companies relevant to data protection. The SDGR ensures that rights of the data subjects are respected, and is directly linked to the General Data Protection Regulation (‘Regulation (EU) , Citation2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation),’ 2016), e.g. Art. 14 SDGR.

The SDGR came into force in December 2018. It must be fully implemented by the European Commission, Members States, and EFTA countries within a transition period of five years by December 2023. Related to the model of Layne & Lee, the transition of SDRG creates different steps. The relevant actors must take stock of the different organisational and government levels, for how far on they are with implementing the OOP. The situation within countries is fairly heterogeneous (Mamrot and Rzyszczak Citation2021), and for most of them, there are still some steps to go until they reach the final stage, with full horizontal integration of systems. In the paragraphs which follow, we describe how the countries and EU level have evolved in the sense of increasing technological and organisational complexity, and at the same time developing the level of integration.

3 Large scale piloting in Europe

The approach of Large-Scale Piloting (LSP) has been used by the European Commission, Member States, and associated countries for several years. It can be regarded as a kind of specific ‘testbed’ for preparing for implementation of new procedures or for accompanying the implementation of new legislative instruments on a Europe-wide level and on a countrywide level. But not all projects initiated by the EC can be considered to be an LSP. A European LSP must fulfil specific requirements, as described in more detail in this paragraph, below.

LSP Definition

LSPs are targeted, goal-driven initiatives that propose approaches to specific real-life challenges (e.g. administrative, societal, or industrial). Pilots are autonomous entities that involve stakeholders from several sides. The entities involved represent governmental, administrative, research, industrial, and citizen communities. The focus is set on a Europe-wide and on a national level. Supply and demand sides are covered and contain all technological and innovation elements, tasks relating to the use, application, and deployment, as well as development, testing, and integration activities.

Large-scale validation is characterised by the fact that it will be possible to operate the functional entities implemented in the pilot under load and constraint conditions close to those for operational load, either with real traffic/request/processing loads or with simulated loads where full implementation is not possible. Demonstrations for operating the system across multiple sites, scalability to a large number of heterogeneous devices and systems, as well as with a large number of real end-users are anticipated. The LSP work plans must include feedback mechanisms to allow adaptation and optimisation of the technological and business approach to the particular use case, as well as a sustainability strategy for results of the projects (European Commission , Citation2021b). Furthermore, the involvement of private sector organisations and technical experts from Member States and associated countries ensured the flexibility required to develop or amend technical solutions (building blocks) of the LSPs. An LSP cannot be maintained by merely a small number of countries and organisations. By definition, more than six countries must participate in an LSP. As displayed in the table below, many more countries and a substantial number of organisations took part in all the LSPs. Besides this, as part of piloting activities within the project, the national infrastructures must be interconnected.

A first step towards LSPs on a Europe-wide level was created through work by the eGovernment group. Member States and the Commission identified a few key domains where common solutions had to be developed at the European level. In 2005, three topics were identified: eID, eProcurement and eHealth. With the financial support of the ICT CIP PSP programme, the Commission, respectively, launched the projects STORK, PEPPOL, and EPSOS in 2008 (European Commission Citation2014a). These projects had a specific mandate and a specific goal relating to one area, e.g. to support implementation of online procedures for public procurement and to showcase the fact such an implementation is technically possible. After successfully launching these projects, as a next step, further sector specific LSPs were initiated. The SPOCS project was commenced to support the transition of the Service Directive in 2009 and e-CODEX kicked off in 2010, to uncover and address the needs of the e-justice domain. Soon afterwards, the idea of initiating cross-sector projects gained momentum with the eventual launch of the e-SENS project. Research organisations, and SMEs became involved as partners in these projects’ public legal entities (Junger, Citation2021). As highlighted in the table below, governments, academia and companies were involved in all LSPs. Participation of public administrations ensured the direct involvement at the policy level of countries and speeded up the implementation of the solution within different countries. The engagement of companies guaranteed the technological background and flexibility for development of the architecture and solutions for market readiness. The participation of universities ensured the scientific background required. Besides this, one of the main recommendations, based on evaluating the Evaluation of the Sixth Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development 2002–2006 (2009), was to follow a new approach and the importance of combining top-down and bottom-up approaches. The table below gives an overview of how LSPs evolved from the beginning of 2008 until 2021. It is evident, the number of partners from several countries across Europe increased continuously. Furthermore, it shows that from the outset, participants from a wide range of countries were active and involved in the projects. Besides which, it is plain to see the scope of the LSPs was continuously widened from area-specific to cross-sector projects, with a strong policy background. The importance of the projects is also underlined by the budgets allocated for different projects. Further details about different LSPs launched by the European Commission, Member States, and associated countries can be found in the table in Annex 1.

This family of projectsFootnote1 led to a paradigm shift. To deliver user-friendly, burden-free digital public services, a change of practice was required between the different cornerstones of administration. Administrations must reuse common services and common building blocks, as much as possible (Junger; Citation2021). The European Commission, supported by Member States and associated countries, plays an important role and influences the direction of the digitalisation process in Europe via initiation of LSPs. With the initiation of an LSP and set for the focus of the LSP, the European Commission steers not just the project itself in a specific direction. As was demonstrated, e.g. by the projects e-CODEX, e-SENS, and TOOP, the results of an LSP can have a direct influence on a Europe-wide level, on Member States, and associated countries. Based on the feedback of members of EU projects, the European Commission has also changed its policy of co-financing the activities of project participants. First of all, the EC had co-financed 50% of project-related costs; with the program Horizon Europe, the EC received criticism from the project partners that this number is too low to ensure a ‘level playing field’ for partners, especially if they are non-profit organisations. The EC has increased co-financing rates to 100% for non-profit organisations and to 70% for all other partners (see, by way of comparison and for further details, Paper 5 ‘Investing in the Single Market? Core-Periphery Dynamics and the Hybrid Governance of Supranational Investment Policies’ in this Special Issue). As outcomes of the aforementioned projects, the blueprints for the European technical OOP infrastructure were delivered (TOOP), the basis for important CEF building blocks like eDelivery were provided (e-SENS), and the need for a robust legal framework for the e-Justice sector was highlighted (e-CODEX). The projects TOOP, e-SENS and e-CODEX in particular displayed the relationship of LPSs and European legal acts. The TOOP project has an influence on the implementing act for Art. 14 SDGR, the e-SENS project for the legal basis of the Connecting Europe Facility and the e-CODEX has a direct impact on e-Justice regulation. Besides which, the projects have prepared the implementation and increased the interest in solutions for cross-border data exchange.

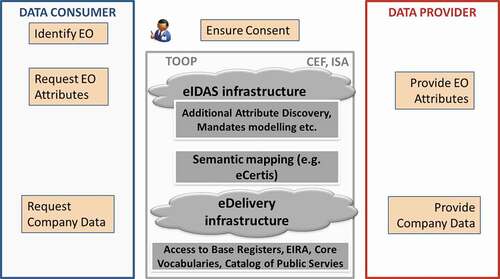

3.1 The once-only principle project

The OOP is a principle that promotes the idea that public administrations should collect information from citizens and businesses once only, and then share this information, keeping in mind regulations and other constraints. The Once-Only Principle Project (TOOP) is the LSP that aims to explore, demonstrate, and enable the OOP on a cross-border scale (Krimmer et al. Citation2017b). Furthermore, TOOP is required to support implementation of the SDGR on an EU-level as well as in Member States and associated countries. Therefore, the architecture has been aligned with SDGR provisions. The project commenced in January 2017 and will finish in 2021.

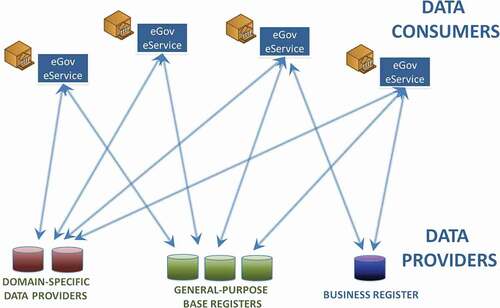

Most European countries started to implement the OOP on a national level, but its cross-border implementation remains fragmented and limited (Tepandi et al. Citation2020). The infrastructure enabling the OOP is in place in 22 out of 30 Member States and associated countries, but the solutions are at various stages of maturity and cover different scopes of information (Mamrot & Rzyszczak, Citation2021). This is quite similar to the e-Government level transformation within these countries. Related to the model introduced by Layne & Lee, most countries that have started to implement the OOP and the transition to e-Government remained between levels 2 and 3. This is also reflected in the architecture used there ().

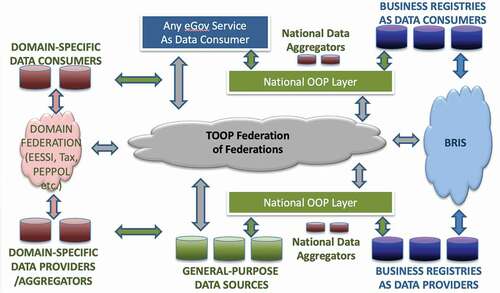

Also inspired by previous LSPs, the architectural approach within the TOOP project was changed from bilateral interconnections between different systems (Data Consumers and Data Providers) to an interconnection via one common infrastructure ().

Furthermore, TOOP follows a different approach than projects supporting traditional model(s) for digitalisation of administrative, primarily government services, into digital services. The project has a focus on a horizontal and multidimensional methodology. This is a deviation from other projects that are aligned with the flat and more vertical models for transition of governmental services. As a consequence of this comprehensive approach, TOOP has also added a further component to the infrastructure for implementation of the OOP on the technical and organisational side. The conceptual model including its architecture developed by TOOP is an example of secure federated architecture, as demonstrated in the figure below ().

Figure 5. The Conceptual Framework of the TOOP Project (Leontaridis Citation2018), (Krimmer et al. Citation2017a).

The TOOP project has concluded developments of the series of LSPs. It underlined the finding that a federated solution with centralised coordination proves to be more successful. Some of these aspects were taken up by the European Commission to sustain the project’s results; for other aspects, a specific non-profit organisation was established (Krimmer et al. Citation2021a).

3.2 COVID-19 and the digital green pass

The EU Digital COVID Certificate was launched in February 2021. The goal was to issue a digital certificate to act as a COVID pass for European citizens and residents. Holders of these certificates would not need to be subject to quarantine when travelling throughout the EU and across EEA countries. Technical development commenced immediately after the announcement in February 2021. The aim was to have certificates available from 1 July 2021. A first proposal for the digital green pass was presented as early as March 2021. The draft regulation for the certificate was presented in April 2021 and was adopted in June 2021 (Regulation (EU) 2021/953 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2021 on a framework for the issuance, verification and acceptance of interoperable COVID-19 vaccination, test and recovery certificates (EU Digital COVID Certificate) to facilitate free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019). The technical solutions developed mainly by private companies on behalf of the different Member States and associated countries are based on existing technical building blocks. As of October 2021, almost 600 million EU COVID Certificates have been issued across 43 participating states and 4 continents. This includes 27 EU Member States, 3 European Economic Area (EEA) countries, Switzerland, and 12 other countries and territories (European Commission, Citation2021d). The certificates of the different countries are, as required by Regulation (EU) Citation2021/953, interoperable with each other and accepted in all participating countries (European Union, Citation2021).

3.3 National case/X-road

Estonia provides a specific national case that is worthy of further analysis, as a fully digitalised country where the OOP has also already been implemented. Implementation is realised technically via the national ‘bus-system’ X-Road. The X-Road interconnects all national data providers and data consumers. The main characteristics of the X-Road, inter alia, are that it is open-source, autonomous, confidential, interoperable, and secure (Rashid Citation2020). As part of the SDGR implementation in Europe via an interface, X-Road will interconnect with the European technical layer. Therefore, a gateway between e-Delivery and X-Road that will enable data exchange between e-Delivery and X-Road ecosystems is used (‘X-Road Development Going Full Steam in 2020,’ 2020). The European solution is based on the technical building blocks provided by CEF, in particular e-Delivery and eID. Previous LSPs such as, e.g. e-SENS, consolidated these building blocks. Further development of X-Road is coordinated by the Nordic Institute for Interoperability Solutions (NIIS). One of the core tasks of NIIS is to ensure development and strategic management of X-Road. This is an exception within Member States with the assignment of the task to NIIS, because the sustainability and governance issues that very often appear for results are usually developed by public legal entities.

3.4 Building blocks, legal aspects, and related issues

Furthermore, there is a set of common and generic technical ‘building blocks’ developed within LSPs and handed over to the EC, or directly established by the EC. The EC recommends further development and reusing these building blocks. This ensures interoperability between different services and the opportunity to integrate them into other systems or platforms, e.g. to interconnect them with the portal ‘Your Europe’. Within the EC, it is the Connecting Europe Facility’s (CEF) responsibility to provide building blocks and to ensure their interoperability. CEF building blocks offer basic capabilities that can be used in any European project to facilitate delivery of digital public services across national borders (EC CEF Digital Citation2021). Widespread building blocks are e.g. e-Delivery and eID. The eID solution is strongly related to the eIDAS regulation (eIDAS Regulation, 2014). Setting up the regulation was a big step forward on the path to creating a common legal basis for the EU. But since the eIDAS Regulation came fully into force in September 2018, implementation of digital identity is recognised as being fragmented, even within the eIDAS framework and has not been harmonised across Member States. This leads to a few interoperability issues that can be described as follows:

Identity matching

The databases used by different administrations in Member States are primarily designed for specific cases or services. The register’s underlying structure is often set up before generic rules for exchanging eIDs, such as in the eIDAS regulation are established. Data schemes are strongly related to the services provided. This causes a gap of attributes that allows an automated exchange of information and mapping of identities. Different information is collected about citizens and businesses and may identify people and organisations in different ways. Some Member States (e.g. Germany) do not have persistent identifiers, or only provide such persistent identifiers as optional attributes, making things even more difficult. This causes a range of problems for matching the identity of a legal entity or of a natural person already on a national but especially on a supranational level.

Record matching

Identification in Europe occurs via eIDs notified under eIDAS. In this case, there is a record matching issue depending on the MS infrastructure. While using notified eIDs under the eIDAS Regulation, for the most part, will allow data providers to match an identity with a record (evidence requested) using the attributes of the natural person provided by the eIDAS minimum data set, in some cases, additional attributes are needed to ensure a match. This is based on a lack of interoperability and credentials defined in eID schemes of the MS.

The lack of a match with regulated electronic identity circuits falls under the auspices of national sovereignty and consequent lack of a sound legal basis. The EC, Member States, and associated countries picked this up via the SDGR Coordination Group (Schmidt et al. Citation2021).

4 Analysis & conclusions

COVID-19 initiated a big boost for digitalisation of services within Member States, associated countries, and on a Europe-wide level. Therefore, the pandemic situation must be viewed as a catalyst for digitalisation of the European Union that renewed or provided further impetus to digital sector integration in the single market. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown up weaknesses of digitalisation of administrative and industrial services, as if through a magnifying glass. The pandemic situation has clearly highlighted the need from a technical point of view for a strong content-agnostic interoperability layer at the European level, to enable the horizontal integration it requires. Besides that, the outcomes of LSPs have highlighted from an organisational perspective, that tasks should be differentiated between the EC and Member States, and that involvement of business, universities, and standardisation bodies is beneficial. The EC should become responsible for agenda-setting and the framework, while Member States and associated countries should be accountable for execution. To align and coordinate the activities of the parties involved – as described in H1 – an institutionalised coordination body is needed. This institutionalised coordination body will be the aforementioned eGovernment Action Plan Steering Board.

The most recent example that emphasized this need is the agreement of EU leaders to implement a ‘Digital Green Pass’. This passport will be a purely electronic certificate, issued by the different Member States and associated countries. The prework of the LSPs, especially of STORK and STORK2, the technical solutions developed, and networks established between different participants speeded up technical implementation. Furthermore, COVID-19 encourages swift implementation. The interoperability of the solutions developed by the different countries and that they were available within the announced timeframe was on the one hand caused by the boost given by COVID-19, and on the other hand was based on existing networks and technical building blocks. This highlights, as anticipated in H2, that public–private interactions further EU single market integration.

One result of analysing LSPs was discovering that in areas where a solid legal basis exists, the gaps in digitalisation are smaller than in fields with no or with only a weak legal framework. It has also been demonstrated that implementation of a sound legal basis boosts related technological developments. Furthermore, the need for amendments to existing legal frameworks such as the eIDAS regulation was highlighted in particular. A revision of the eIDAS regulation to cover existing gaps has been requested not only by the EC but also by Member States and several other stakeholders.

The architecture provided by TOOP is aligned with existing EU frameworks (EIRA, EIF), the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), Digital Service Infrastructures (DSIs), and building blocks consolidated by the LSP e-SENS. The architecture contributes to implementing OOP in public administrations, supports the interconnection and interoperability of national registries at the EU level, and aims to contribute to the implementation act of the SDGR. It is the next step towards a solution covering the gap between well-known models for the transition of Government into e-Government.

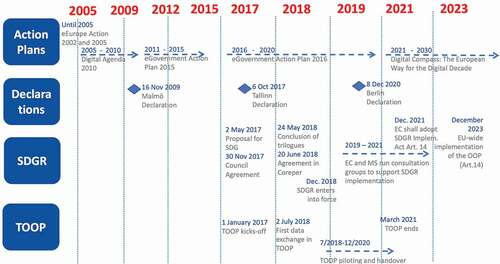

The analysis of outcomes of LSPs not only highlighted that piloting on a large scale is an appropriate instrument for bringing stakeholders together, to develop technical solutions and identify open issues. It has also shown us, that an LSP is probably the only approach for testing the transformation process on a national and supranational level. As described above, legal and technical issues such as record matching and identity matching problems were discovered within LSPs. Besides this, the LSPs and tests to interconnect different infrastructures showed us that most of the participating countries and/or organisations are in or are in-between phases 2 and 3 of the Layne & Lee model. Consequently, it may be considered worthwhile to propose a new cycle of LSPs, that focus on and have a new thematic context. Aside from the contemporary context, a new dimension should be added from the organisational side. This should reflect the perception of previous LSPs, especially the TOOP project, that it is crucial to continue and extend the involvement of vertical networks. Accordingly, vertical networks should be interconnected with existing horizontal networks, and the related structure should be institutionalised. On the one hand, this would be a step forward in using and reinforcing the network; on the other hand, the network can be extended thematically, and future LSPs could focus, e.g. on data ownership, data reorganisation, and data responsibilities (Krimmer et al. Citation2021b). The below gives an overview of how the activities related to Action Plans, Ministerial Declarations, the SDGR and the TOOP project were aligned.

Figure 6. Analysis of the Relationship between Egov Action plans, the relevant declarations, SDGR Implementation and the corresponding large-scale pilot TOOP.

Altogether, this shows that with the initiatives around the Actions Plans, Declarations and LSPs, the EC and LSPs have deepened integration of the single market and implementation of a DSM: While the Malmö declaration promoted interoperability as an important action item for the first time, the Egov action plan of 2016 provided impetus to the eGovernment Action Plan Steering Board to launch a Large-Scale Pilot on the topic of Once-only and thus furthered interoperability and the creation of an European digital ecosystem in the form the Digital Single Market. It was this steering group that ensured the coordination and success when forming such a large-scale pilot, as well as coordinating its efforts to build a bottom-up system created by the Member States, which would fulfil the ideas inscribed in the second principle of the Tallinn declaration furthering the Once-only principle. It was then this coordination, which allowed the Estonian presidency of the European Council to propose the Single Digital Gateway Regulation, paving the way to overcome the largest obstacle and as a consequence to become the strongest driver for integration of the Digital Single Market in the form of the technical system providing for SDGR article 14. This would not have been possible without the formal and informal coordination work of the eGovernment Action Plan Steering Board.

This clearly relates to and confirms the first of the two underlying hypotheses (H1), introduced at the beginning of this paper. We can thus further conclude that due to the fact that the European Commission has taken over and continues to maintain the building blocks, the European Commission has become a key player for implementation of electronic services in Europe and implementation of the DSM. Besides this, the EC (see, by way of comparison, Paper 3 ‘Digital Single Market and the EU Competition Regime: An Explanation of Policy Change’ in this Special Issue) changed its ex-post approach to digital competition with a new ex-ante regulatory regime. Furthermore, the European Commission plays a leading role in the involvement of all related and interested parties in the development process. The involvement of private sector organisations, like companies and standardisation bodies and public–private interactions within the context of the LSPs and beyond, additionally supports the aims. Private legal entities provide the necessary technical expertise and can help to solve resource issues, etc. Furthermore, they ensure that the results are ‘ready for market’, and that in line with existing standards, they guarantee interoperability and connectivity with other solutions and as anticipated in H2, promote resilience in EU single market integration.

Therefore, it is evident in a way that organisations like the European Commission and coordination bodies like the eGovernment Action Plan Steering Board, that are not profit-oriented are essential to provide a forum to involve all important key players and stakeholders, and the participation of private legal entities ensures that the market can adopt the results. The analysis and descriptions above confirm the underlying hypotheses H1 and H2. The Single Digital Gateway has already proven to be a driver for building a digital eco-system throughout Europe. But there is still much for us to explore, learn, and further examine, so it would also be beneficial to accompany setting up and implementation of the new version of the eIDAS regulation, and further exploitation of DSM and related aspects, from a scientific point of view.

Annex 1. Overview of Large-Scale Pilot Projects 2008 - 2021

Acknowledgments

The work for this article was supported in part by ERASMUS + Jean Monnet Network VISTA, Project number 612044-EPP-1-2019-1-NL-EPPJMO-NETWORK, Grant Decision no. 2019-1609/001-001, as well as by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement nos. 857622 and 959072.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. STORK, PEPPOL, EPSOS, SPOCS, e-CODEX, e-SENS.

References

- Bannister, F. 2001. “Dismantling the Silos: Extracting New Value from IT Investments in Public Administration.” Information Systems Journal 11 (1): pp. 65–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2575.2001.00094.x.

- Baskerville, Richard, and Michael D. Myers. 2004. “Special Issue on Action Research in Information Systems: Making IS Research Relevant to Practice: Foreword.” MIS Quarterly 28 (3): pp. 329–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/25148642.

- Clark, J. S., U. Kansas State, S. Porath, U. Kansas State, J. Thiele, U. Kansas State, M. Jobe, and U. Kansas State (2020). “Action Research Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=ebooks

- Clarke, A. (2017). “Digital Government Units: Origins, Orthodoxy and Critical Considerations for Public Management Theory and Practice”. Orthodoxy and Critical Considerations for Public Management Theory and Practice (July 12, 2017).

- Davison, R. M., M. G. Martinsons, and C. X. Ou. 2012. “The Roles of Theory in Canonical Action Research, Management Information Systems Research Center, University of Minnesota.” In MIS Quarterly (Minnesota: Management Information Systems Research Center, University of Minnesota), pp. 763–786.

- Directive 1999/93/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 1999 on a Community framework for electronic signatures, “e-Signature Directive Accessed 01 11 2021” (1999). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31999L0093

- Dupont, L. 2019. “Agile Innovation: Creating Value in Uncertain Environments.” Journal of Innovation Economics Management, no. 28: pp. 1–5.

- EC CEF Digital. (2021, March 9). “What Is a Building Block Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/CEFDIGITAL/What+is+a+Building+Block

- European Commission. (2012). “E.C., Public Services Online ‘Digital by Default or by De-tour?’ Assessing User Centric eGovernment Performance in Europe – EGovernment Benchmark 2012: EC (2012) E.C., Public Services Online ‘Digital by Default or by De-tour?’” Assessing user centric eGovernment performance in Europe – eGovernment Benchmark 2012. European Commission, Brussels.

- European Commission. (2014, March 31). “Information and Communication Technologies Policy Support Programme (ICT-PSP)”. European Commission Accessed 01 11 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/cip/ict-psp/index_en.htm

- European Commission. (2015). “A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe”.

- European Commission. (2017). “6 Interoperability Layers Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/nifo-national-interoperability-framework-observatory/solution/eif-toolbox/6-interoperability-layers#IOPL2

- European Commission (2021a) “Shaping Europe’s Digital Future’ Accessed 01 11 2021” https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/shaping-europe-digital-future_en

- European Commission. (2021b, March 4). “European Commission: Cordis: Programmes: Large Scale Pilots”. Publication Office/CORDIS Accessed 01 11 2021. https://cordis.europa.eu/programme/id/H2020_IoT-01-2016

- European Commission. (2021c, March 9). “Digital Green Certificates Factsheet [Press Release] Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/FS_21_1083

- European Commission. (2021d). “EU COVID Certificate: The Global Vaccine Passport Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://www.covidpasscertificate.com/europe-digital-green-pass/

- Geraghty, K. 2017. “Interview: Digital Transformation Requires a Different Mindset.” Governance Directions 69 (7): pp. 390–391.

- Junger, J.-F. 2021. “Introduction - The Once-Only Principle (TOOP).” In The Once-Only Principle (Vol. LNCS 12621), edited by R. Krimmer and A. Prentza, and Mamrot, S. Cham: Springer .

- Krimmer, R., A. Cepilovs, C. Schmidt, I. M. Põder, A. Prentza, L. Leontaridis, S. Mamrot, and A. Schindler (2021a). “The Once-Only Principle Project - Final Report Accessed 01 11 2021”. www.toop.eu

- Krimmer, R., A. Prentza, S. Mamrot, and C. Schmidt. 2021b. “The Future of the Once-Only Principle in Europe.” In The Once-Only Principle (Vol. LNCS 12621), edited by R. Krimmer, and A. Prentza, and Mamrot, S. Cham: Springer pp 225- 236 .

- Krimmer, R., T. Kalvet, M. Olesk, and A. Cepilovs. 2017a. “Position Paper on Definition of OOP and Situation in Europe (Updated Version).” Project Deliverable D2.14. doi:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3947903.

- Krimmer, R., T. Kalvet, M. Toots, A. Cepilovs, and E. Tambouris (2017b). “Exploring and Demonstrating the Once-Only Principle”. In C. C. Hinnant (Ed.), Proceedings of the 18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research. ACM Staten Island NY. https://doi.org/10.1145/3085228.3085235.

- Krimmer, R., and W. Webster (2021). “Trust, Security and Public Services in the Digital Age”. (forthcoming).

- Layne, K., and J. Lee. 2001. “Developing Fully Functional E-government: A Four Stage Model.” Government Information Quarterly 18 (2): pp. 122–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00066-1.

- Leontaridis, L. (2018). “TOOP Pilots and Architecture Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://www.toop.eu/sites/default/files/Day_1_20180924_TOOP_Pilots_Leontaridis.pdf

- Mamrot, S., and Rzyszczak K. 2021. “Implementation of the ‘Once-only’ Principle in Europe – National Approach.” In The Once-Only Principle (Vol. LNCS 12621), edited by R. Krimmer, and A. Prentza, and Mamrot, S. Cham: Springer pp. 9 - 37 .

- Mergel, I., N. Edelmann, and N. Haug. 2019. “Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews.” Government Information Quarterly 36 (4): p. 101385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.06.002.

- Meyerhoff Nielsen, M. 2020. “The Demise of eGovernment Maturity Models: Framework and Case Studies.” doi:https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.29704.24323.

- Meyerhoff Nielsen, M. 2017. “Governance Failure in Light of Government 3.0: Foundations for Building Next Generation eGovernment Maturity Models.” In Public Administration and Information Technology: Vol. 32. Government 3.0: Next Generation Government Technology Infrastructure and Services. edited by A. Ojo, and J. C. Millard, Vol. 32, pp. 63–109. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63743-3_4.

- Rashid, N. 2020. Deploying the Once-Only Policy: A Privacy-Enhancing Guide for Policymakers and Civil Society Actors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy school.

- Regulation (EU) 2021/953 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2021 on a framework for the issuance, verification and acceptance of interoperable COVID-19 vaccination, test and recovery certificates (EU Digital COVID Certificate) to facilitate free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2021 Accessed 01 11 2021). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R0953

- Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC Accessed 01 11 2021, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/910/oj

- Regulation (EU) “2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), GDPR Accessed 01 11 2021” (2016). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

- Schmidt, C., R. Krimmer, J. Lampoltshammer, , and Roßnagel, T., Schunck, C. H., and Mödersheim, S. (2021). “When Need Becomes Necessity” - The Single Digital Gateway Regulation and the Once-Only Principle from a European Point of View [Text/Conference Paper] Accessed 01 11 2021. http://dl.gi.de/handle/20.500.12116/36498

- Statskontoret. 2000. 24-timmmarsmyndighet: Förslag Til Kriterier För Statlige Elektronisk Förvaltning I Medborgarnas Tjänst: Statskontoret (2000) 24-timmmarsmyndighet: Förslag Til Kriterier För Statlige Elektronisk Förvaltning I Medborgarnas Tjänst, pp. 1–80. Stockholm: Statskontoret.

- Tepandi, J., E. Grandry, S. Fieten, C. Rotuna, G. P. Sellitto, D. Zeginis, D. Draheim, G. Piho, E. Tambouris, and K. Tarabanis (2020). “Towards a Cross-Border Reference Architecture for the Once-Only Principle in Europe: An Enterprise Modelling Approach”. In J. Gordijn, W. Guédria, and H. A. Proper (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing. PRACTICE OF ENTERPRISE MODELING: 12th ifip working conference, poem 2019 Luxembourg (Vol.369, pp. 103–117). SPRINGER NATURE. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35151-9_7.

- Ursula, von der Leyen. (2021). “Ursula Von der Leyen Tweet “Digital Green Pass” [Tweet]”. Twitter Accessed 01 11 2021. https://twitter.com/vonderleyen/status/1366346729289904128

- X-Road development going full steam in 2020 (2020, March 3). “Nordic Institute for Interoperability Solutions Accessed 01 11 2021”. https://www.niis.org/blog/2020/3/3/x-road-development-in-2020