ABSTRACT

Although the hotspot approach has been one of the key EU responses to the 2015 migration crisis, it has not received much systematic attention from EU scholars. Addressing this research gap, this article examines the establishment and implementation of the EU hotspot approach in Italy and its operational reliance on EU agencies. Building on and extending the conceptual framework of the European Administrative Space (EAS), we show how Frontex and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) have strengthened both their independent administrative capacity and integration within the EAS. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the role of EU agencies within the Italian hotspots, we also discuss two important yet widely neglected features of administrative governance, namely the level of precision of the agencies’ mandate and interagency cooperation. Our analysis draws on a broad range of primary sources as well as nineteen semi-structured expert interviews.

Introduction

From its outset, the development of a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) has been dominated by interest diversity among member states and strategic uncertainty that prevented a supranationalisation of asylum standards and enforcement mechanisms (Scipioni Citation2018; Den Heijer, Rijpma, and Spijkerboer Citation2016; Bendel and Ripoll Servent Citation2018). The 2015–2016 so-called migration crisis has brought these and deficiencies of the CEAS to the fore.Footnote1 Many scholars have analysed the EU’s crisis management from the perspective of what it means for European integration (Schimmelfennig Citation2018; Biermann et al. Citation2019; Scipioni Citation2018). Transcending this intergovernmentalist/supranational focus, this article is more concerned with the organizational structure of the EU’s hotspot approach, one of the key crisis measures in the context of the CEAS (e.g. Horii Citation2018). In particular, we ask who has done what and how in the context of establishing the EU hotspot approach. We will show that the establishment of hotspots and its operational reliance on EU agencies have strengthened the EU’s executive-administrative order (Curtin Citation2009; Trondal Citation2010). The creation of EU hotspots has been driven by and for EU executive actors. The Commission, the European Council and the Council have been responsible for setting up the policy framework and strengthening mandate, resources and interagency cooperation of EU Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) agencies. Specifically, the highly underspecified hotspot approach provided EU agencies with considerable room for manoeuvre and flexibility, turning them into key actors on the ground.

To understand the organizational structure of crisis governance and the range of agency discretion, this article builds on and extends the research on the EU’s executive order and administrative governance (Trondal Citation2010, Citation2014; Trondal and Peters Citation2013; Curtin Citation2009). Empirically, we will discuss the case of EU hotspots in Italy focusing on the specific role of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) therein. We have chosen the Italian hotspots for the following reasons: First, to avoid a ‘moving target’ problem, the hotspot approach is one of the few key measures the EU has actually managed to adopt and implement in the wake of the migration crisis. Other measures such as the reform of the Return Directive or the Dublin regime are still pending due to divergent preferences among EU member states. Second, while there exist informative but atheoretical studies by the European Parliament (e.g. Neville, Sy, and Rigon Citation2016; European Court of Auditors Citation2017), human rights groups (e.g. Amnesty International Citation2016; Human Rights Watch Citation2016) or academic blog entries (e.g. Maiana Citation2016), the hotspot approach has received little attention from EU scholars (with the notable exception to the work of Scipioni Citation2018).Footnote2 Given the predominant role of executive actors, notably EU agencies, and the sidelining of parliaments, this research lacuna is particularly unfortunate. In addition to the relevant academic literature, our analysis draws on a broad range of primary sources, including the EU and national policy documents, legal texts as well as nineteen semi-structured expert interviews with officials from EU-institutions, EU agencies, international organizations, NGOs and EU member states.Footnote3

We will proceed as follows: First we introduce the executive-administrative governance literature, notably the concept of the European administrative space (EAS). Building on and extending the EAS concept, we then show how the mandates and resources of Frontex and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) have been expanded post-migration crisis allowing them to strengthen their operational role within the Italian hotspots. This will be followed by a section on the growing integration between supranational and national executives (vertical), and between the EU agencies (horizontal) in the course of implementing the hotspot approach.

The role of EU agencies within the EU’s executive order

EU scholars have widely analysed both the 2015 migration crisis and EU agencies through the theoretical lenses of intergovernmentalism and supranationalism (e.g. Hooghe and Marks Citation2019; Börzel and Risse Citation2018; Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Citation2015; Scipioni Citation2018). Classical theories of EU integrations have offered important insights with regard to EU crisis management but struggle to understand the role of JHA agencies combining elements of national and supranational forces (Rijpma Citation2012; Ansell and Trondal Citation2018; Everson, Monda, and Vos Citation2014). While supranational scholars tend to underrate the role of Frontex and EASO, intergovernmentalist accounts often ignore them in their analysis at all (Schimmelfennig Citation2018; Biermann et al. Citation2019). This is particularly problematic in times of crisis, when policy-makers often resort to hybrid organizations that provide the flexibility needed to respond to varied and competing demands (Pollak and Slominski Citation2021; Brandsen and Karré Citation2011; Zeitlin Citation2016). Building on the insights of the executive-administrative governance literature may help us to grasp the hybrid structure of the EU’s hotspot approach and its strong reliance on EU agencies. In particular, we extend the concept of the European administrative space (EAS) that mainly focuses on institutional independence and integration (Trondal Citation2014; Trondal and Peters Citation2013). With regard to the former, we deal not only with the material resources of EU agencies but also take into account their strengthened and broad mandate (see also Wonka and Rittberger Citation2010). With regard to the latter, we examine not only the vertical relationship between EU agencies and the competent national authorities but also shed light on the growing horizontal interagency relations within the hotspots (see also Thatcher and Stone Sweet Citation2002; Benz, Corcaci, and Doser Citation2016).

The EU’s executive power consists of both a political and an administrative (bureaucratic) level. Given its multilevel structure, the EU has a plurality of executive actors that operate on and across different governance levels including the European Council, the Council, the Commission and national governments (i.e. political executive) and EU agencies (i.e. administrative-executive) (Curtin Citation2009; Curtin and Egeberg Citation2008; Trondal Citation2010). As we will show in the empirical section, it was the political executive who granted considerable powers to the administrative-executive through non-binding and vaguely worded instruments (see Abbott and Snidal Citation2000). The administrative-executive has then used this enhanced institutional independence to strengthen its integration within the EU’s administrative space.

2.1. Independent administrative capacity: resources and mandate

The EAS requires the institutionalization of independent administrative capacity at the EU level, notably the establishment of permanent and separate institutions that are essential to act relatively independently of national governments (Trondal and Peters Citation2013, 296). Most accounts of the EAS have only focussed on the financial and personnel resources of agencies.Footnote4 However, to assess the independent administrative capacity of an agency it is also important to examine its mandate that determines what an agency actually does with its resources in the post-delegaion phase (see also Wonka and Rittberger Citation2010).

The debate about the regulatory scope of EU agencies has been shaped by the ‘anti-delegation’ or Meroni doctrine of the European Court of Justice, which states that the EU legislative institutions can delegate only ‘clearly defined executive powers’ to EU agencies (Lenaerts Citation1993, 41). Despite these restrictions, scholars have long observed various struggles within EU institutions to loosen the constraints of the Meroni doctrine and expand the powers of EU agencies in order to cope with functional needs that come with the increasing complexity of the EU’s tasks (Majone Citation2002; Vos Citation2016). In addition, EU agencies may also increase their powers by stealth (Majone Citation2005; Thatcher and Stone Sweet Citation2002, 5; Sandholtz and Stone Sweet Citation2012). This process of ‘regulatory seizure’ is particularly palpable in cases when agencies are allowed to operate and experiment on the basis of broad mandates without proper substantive guidance (Sabel and Zeitlin Citation2010; Ossege Citation2016; Blanc and Ottimofiore Citation2017; Pollak and Slominski Citation2009).Footnote5 Operating within these broad zones of discretion, EU agencies can effectively punch above their envisaged role of a mere supporter or coordinator of national authorities (Thatcher and Stone Sweet Citation2002; Groenleer Citation2009).

2.2. Vertical and horizontal integration of the EAS

The growing regulatory mandates and resources of EU agencies do not automatically translate into a coherent and effective administrative space. To avoid a fragmented system of overlapping or even counteracting administrative actors, a functioning EAS requires some degree of internal integration. Previous research has already found evidence for integration within the Commission as well as between the Commission and EU agencies (Egeberg, Trondal, and Vestlund Citation2015; Peterson Citation2017; Kassim and Peterson Citation2011). The interaction between administrative actors is particularly intense when it comes to the implementation of EU law. Here, EU agencies play an important role in improving the Commission’s monitoring capacity and facilitating the effective and uniform enforcement of EU law at the national level (Scholten Citation2017; Everson, Monda, and Vos Citation2014; Groenleer, Kaeding, and Versluis Citation2010). Establishing close relations with national authorities also provides EU agencies with vital information that further reinforces their independent regulatory capacity (see above). An integrated and coherent EAS does not only depend on vertical integration but also requires adequate cooperation among EU agencies. In fact, recent scholarship indicates that interagency relations among EU JHA have increased in recent years, especially after the 2015 migration crisis (see Citation2021).

The EU hotspot approach: strengthening the mandate and resources of EU agencies

EU asylum, migration and border policies are widely dominated by intergovernmental bargaining and weak EU legislation that leave important implementation powers and operational capacity with the member states (Monar Citation2010; Lavenex, Lehmkuhl, and Wichmann Citation2009). The 2015 migration crisis has also evoked and reinforced a persistent diversity of national interests. While Northern EU states are determined to stick to the current Dublin regime and are unwilling to agree to a burden-sharing scheme for allocating migrants, overwhelmed Southern frontline states have at times embarked on a non-registration and ‘waving through’ policy (interview 4). This approach, in turn, led Northern states to remind frontline states of their legal obligation and responsibility to process asylum seekers according to the Dublin rules (e.g. Perkowski Citation2016; Lavenex Citation2018; Ceccorulli Citation2019). While the migration crisis created an urgency to resolve these tensions and to demonstrate problem-solving capacity, the EU was not able to undertake major legislative reforms (Kriesi Citation2016; Buonanno Citation2017; Martin Citation2019).Footnote6 This is not to say that the EU has remained entirely inactive. In fact, the EU has mainly resorted to legally nonbinding executive decisions strengthening administrative actors, notably EU agencies, such as Frontex or EASO in terms of mandate, resources and integration with other administrative actors.

3.1. Enhancing the mandate of Frontex and EASO through executive soft law and practice

The EU’s inability to embark on a comprehensive legislative reform process opened a window of opportunity for executive actors to adopt ‘practical and flexible tools’ to tackle the EU’s migration crisis (interview 2). In May 2015, the Commission announced a ‘new’ hotspot approach in which the EU agencies Frontex and EASO are supposed to play a prominent role in swiftly identifying, registering and fingerprinting incoming migrants with the aim to strengthen compliance with EU law by Southern frontline states and avoid ‘secondary movements’ towards North-Western Europe (European Commission Citation2015a, 6; Hammargård and Olsson Citation2019, 11; Niemann and Speyer Citation2018).Footnote7 Three months later, in June 2015, the Commission’s hotspot approach and the upgrading of EU agencies were broadly endorsed by the European Council, the highest executive authority in the EU. At the same time, the European Council also invited the Commission to specify these broad objectives, in close cooperation with the hosting member states, and draw up a road map on the legal, financial and operational aspects of these hotspot facilities (European Council Citation2015). The Commission then further elaborated the hotspot approach in another legally non-binding ‘Explanatory Note’ setting out the way in which the hotspot approach is implemented in practice (European Commission Citation2015b).

Considering the mandate of the agencies, the Explanatory Note makes clear that Frontex along with the authorities of the host state should carry out fingerprinting and registrating in EURODAC to determine the identity and nationality of irregular migrants. Frontex is also tasked to support the debriefing of migrants to understand routes with the view to contribute to investigations into smuggling networks and criminal analysis. These findings are expected to feed into the agency’s intelligence and risk assessment. In addition, EASO supports host states through the deployment of asylum support teams,in particular, with expert know-how regarding the asylum process (European Commission Citation2015b).

Both the Commission and the European Council were careful to frame the legally non-binding hotspot-approach as a ‘quick’ and ‘flexible’ crisis response mechanism within the existing boundaries of EU law that is legitimized by its ‘results’ (interview 2 and 4). While the Explanatory Note has strengthened the mandate of Frontex, it did so in a soft and vague manner leaving the agency with considerable leeway in how to interpret and implement it (interview 19). One year later, in September 2016, the EU legislature adopted the Frontex recast regulation (2016/1624; which was again amended by regulation 2019/1896). While the regulation has hardened the executive soft law in terms of obligation, it has not improved the level of precision of the pre-existing framework (see Abbott and Snidal Citation2000). In fact, it mainly reiterates previous soft law provisions (e.g. Art. 82,016/1624) or consolidate the broad executive mandate by prescribing that it is the responsibility of the Commission – along with the host member state and the relevant EU agencies – to establish ‘the terms of cooperation’ at the hotspot area (Art.18(3) 2016/1624; Art 40(3) 2019/1896). This means that further substantive specifications regarding the tasks of Frontex in the hotspots can, if at all, only be found in EU executive soft law documents, such as the Explanatory Note or operational plans for Joint Operations.Footnote8

In contrast, since the EU legislature has so far not been able to amend EASO’s founding regulation (439/2010), EASO’s mandate within the hotspot approach have been shaped by executive hard and soft law only. In fact, the main hotspot-related tasks of EASO are enshrined in Council Decision 2015/1523, Council Decision 2015/1601, the Commission’s Explanatory Note and in the operating plans the agency concluded with Italy. Like in the case of Frontex, EU policy-makers were of the opinion that a legislative approach would have been too uncertain and time-consuming (interviews 1, 2 and 9). To circumvent a lengthy and contentious legislative process, the Council opted for a broad mandate suggesting that ‘EASO should step up and increase activities without providing any further specifications’ (interview 9). The lack of political guidance has provided significant leeway for Frontex and EASO to experiment within the hotspots (see also Sabel and Zeitlin Citation2010). Both agencies have acquired considerable operational and discretionary powers that went beyond a mere supporting role. This has been further intensified by Italy’s inability to properly process the incoming migrations. In the absence of a sufficiently precise legal framework, Frontex ‘took the lead and carried out fingerprinting on their own’ (interview 2). In particular, Frontex used its broad zone of discretion and provided incoming migrants with information on relocation and national laws in order to facilitate registration and identification processes (interviews 5 and 15). Similarly, EASO has also used its vaguely worded mandate and moved beyond a supporting role within Italian hotspots. The EASO regulation makes clear that the agency should have ‘no direct or indirect powers’ in relation to an individual asylum decision (recital 14,439/2010). However, EASO has gradually developed into a key actor in the asylum process. For instance, EASO has informed incoming migrants about asylum and relocation procedures and played an important role in the pre-identification of potential cases for family reunification” (interview 9; Italian Ministry of Interior Citation2016). What is more, EASO also has conducted asylum interviews, established relevant facts of individual cases that were crucial for the final asylum decisions (interview 5). While these informal practices clearly contradict EASO’s founding regulation, they are partly reflected in the legally non-binding Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) which give EASO an (at least) indirect role in relation to individual asylum decisions (Italian Ministry of Interior Citation2016; interview 19; Dutch Council for Refugees Citation2016).Footnote9

3.2. Growing resources for Frontex and EASO

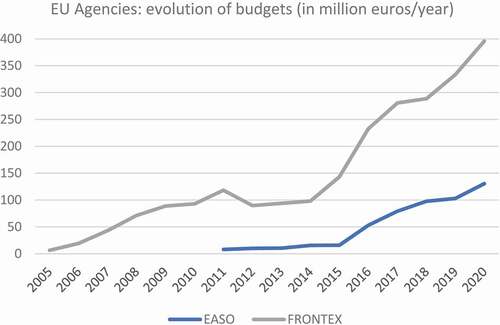

The budget and staff of both Frontex and EASO have constantly increased since their inception. Frontex has experienced a particularly significant growth in its budget, which has risen from merely 6.2 million euros (2005) to 395.6 million euros (2020). Likewise, albeit to a lesser extent, EASO’s budget has risen from eight million euros (2011) to 130.4 million euros (2020) (see ). The 2015 migration crisis has contributed significantly to the sharp rise of the agencies’ resources. By comparing the initial with the revised commitment allocations for both agencies in the 2014–2020 Multiannual Financial Framework, we observe that the EU has been willing to raise funding for the agencies during the migration crisis. Both Frontex and EASO used these additional fundings to provide experts as well as technical and financial resources within the hotspots. In the case of Frontex, we observe an increase from the initial allocation of 628 million euros to 1,638 million euros, whereas EASO grew from the initial allocation of 109 million euros to 456 million euros (European Parliament Citation2018, 15).

Figure 1. Frontex and EASO evolution of budgets.

In the multiannual EU financial framework (2021–2027), EU aims to increase the Frontex budget to around €9.4 billion in total (Bossong Citation2019, 2) and by 2027, its staff is expected to create a standing force of 10,000 border guards (Art. 5(2) 2019/1896 Frontex Regulation). Likewise, EASO’s annual budget is also envisaged to increase to 174.8 million euros in 2023 (EASO Citation2020a, 37).

Strengthening agency integration in the European administrative space

The 2015 Explanatory Note made clear that the hotspot approach is a platform for relevant EU agencies, such as Frontex, EASO, Europol or FRA ‘to intervene, rapidly and in an integrated manner’ in frontline states during a migration crisis (European Commission Citation2015b, 2–3). Hence, it was important to highlight the necessity of ‘operational coordination’ among various administrative actors within the hotspot approach. It has been the responsibility of the newly created EU Regional Task Force (EURTF) in Catania to ‘improve inter-agency cooperation and information exchange, and to enable concerted action from the moment of disembarkation of migrants and to channel these persons through the appropriate asylum or return procedures’ (European Commission Citation2015b, 7). To ensure permanent operational coordination among these different administrative actors, it has been considered as ‘essential’ that officers from Frontex, EASO, Europol, the Commission and Italian authorities (Guardia di Finanza, Italian Coast Guard and Police) are present in this EURTF (interview 12). If necessary, also other agencies such as Eurojust or FRA may deploy staff to the EURTF. The EURTF has to build close links to relevant national authorities, the coordination structures, in particular, the International Coordination Centre for Frontex Joint Operations, as well as to liaise with international actors, such as Interpol, the International Organization for Migration, UNHCR and relevant NGOs (European Commission Citation2015b, 3–4).

4.1. Administrative cooperation between EU and Italian authorities

To make the hotspot approach work, an effective cooperation between the EU and Italian administrative actors has been considered essential. While the EU and Italian political executive actors have set the stage with their vaguely designed hotspot design, EU agencies and Italian administrative officals have reinforced the operational cooperation in border management. With regard to the former, a 2015 Council Decision (2015/1523) required Italy to present a ’roadmap’ to the Commission with ‘adequate measures’ to enhance the capacity, quality and efficiency of their systems in the areas of asylum, first reception and return (Article 8). Accordingly, the Italian Ministry of the Interior adopted such a roadmap (Ministry of the Interior [Italy] Citation2015), which not only aimed at improving the problem-solving capacity of the Italian asylum and border procedures but also at ensuring Italy’s compliance with the relevant EU acquis (Maccanico Citation2015).

The close interaction between the Council, the Commission and the Italian Ministry of the Interior has continued at the operational level. Officials from DG Home have regularly travelled to Rome setting up the hotspot procedures and coordinating the day-to-day interaction between EU institutions and Italian authorities (interview 2). At the same time, DG Home has also attended the weekly meetings at the EURTF, which served as an important interface between various EU and Italian bureaucrats. In particular, the task of DG Home was interpreted as monitoring not only the common setup of the hotspot approach and the coordination of EU agencies, but also the compliance of Italy with existing EU rules (interview 3, 4 and 12). The EU hotspot approach can thus be considered as a way of centralizing EU law enforcement without directly challenging the administrative autonomy of the member state concerned.Footnote10

In particular, the EU aimed to overcome Italy’s slow and fragmented system of registration, by enhancing the coordination efforts among Italian authorities, and between them and relevant EU institutions (interview 11; Neville, Sy, and Rigon Citation2016; EASO Citation2020b, 5). Frontex officers supported Italian authorities during migrant disembarkation and also organized training sessions to improve its technical skills. To achieve the target of a 100% fingerprinting rate, the Commission also expected Italy to set up a ‘solid legal framework’ and ‘allow the use of force for fingerprinting‘ (European Commission Citation2015f, 2).

Likewise, EASO has strengthened its cooperation with officials from the Italian Ministry of the Interior with the view to streamline and harmonize Italy’s asylum system (interview 9, 10 and 19). Cooperation between EASO and Italy has already started in 2013. While at the beginning EASO supported Italy in areas, such as data collection and analysis, Country of Origin Information (COI), the Dublin system, the reception system and emergency capacity, and the strengthening of the independence of the judiciary, as well as further professional development of the National Asylum Commission, the support has been extended in the course of the 2015 migration crisis and has increasingly become an operational dimension and includes information provision at hotspots and involvement in file preparation. In the 2019 Operational Plan, the EASO’s focus shifted even more on reducing the backlog of asylum requests, supporting the quality and standardisation of asylum procedures, develop an integrated asylum information system (Sistema Unico Asilo) and implement the national and EU legal frameworks in the field of asylum (EASO Citation2020b, 5; interview 10 and 19). To facilitate this, the EASO established offices at the Department of Public Security (Dipartimento della Pubblica sicurezza) and the Department of Civil Liberties and Immigration (Dipartimento per le Libertà civili e l’Immigrazione) within the Italian Interior Ministry to coordinate with competent Italian authorites.

The Commission’s leverage over Italy stems not only from EU law or political agreements but also has a significant financial dimension. Combining its monitoring function with its competence of managing both the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and Internal Security Fund (ISF) budgets,Footnote11 the Commission has powerful sticks at its disposal to ensure the compliance of frontline member states, such as Italy (interview 2 and 3; European Court of Auditors Citation2019). These powers also played a role in enforcing the legally non-binding hotspot rules. As a former Commission official put it: ‘If Italy wishes to apply for these funds and is not complying with the EU’s [hotspot] rules, well, this could be a problem that the Commission may address’ (interview 4).Footnote12

Italian authorities have initially been reluctant to implement the EU hotspot approach (Neville, Sy, and Rigon Citation2016). Many officials perceived the involvement of EU agencies at hotspots as a form of monitoring and an undue interference in Italian sovereignty (interview 4 and 10). In particular, despite the objective of strengthening its border management and asylum system, hotspots were regarded as a completely new ‘foreign’ concept that would create difficulties for local street-level bureaucrats (interview 16). Even the then Minister of the Interior Angelino Alfano joined the chorus of criticism complaining that ’hotspots and hubs are nice English words that must be translated into legal norms‘ (Camera dei Deputati Citation2016, 33, translation by the authors). However, as it turned out, most tensions between Italian and EU institutions have eased over time. While the hotspot approach has provided Frontex and EASO with the opportunity to monitor Italian authorities’ compliance with EU rules, the close cooperation among them has ultimately convinced Italian officials ‘that it is better to follow the EU’s standard procedures, as they benefitted the overall Italian border and asylum management” (interview 9). Overall, the cooperation between Italy and EU agencies has not only been strengthened but also proved to be beneficial for both sides. On the one hand, Italy’s border and asylum management has significantly improved, notably with regard to registration and reducing the backlog of asylum claims that reduced the political pressure both domestically and from other EU states (interview 9, 10 and 11). As a result, the Commission closed the infringement procedures against Italy (European Commission Citation2016). On the other hand, the hotspot approach has allowed Frontex and EASO not only to strengthen their role in implementing the EU’s asylum and border acquis but also seized the opportunity to collect first-hand intelligence, which, in turn, improved the EU’s understanding of migration flows and security threats (interview 8).

4.2. The intensification of interagency relations

Early on, the Commission conceived the hotspot approach as a platform for relevant EU agencies, such as Frontex or EASO ‘to intervene, rapidly and in an integrated manner’ through operational and flexible tools that would allow swift responses to fast-moving situations (European Commission Citation2015b, 2–3).Footnote13 Cooperation among JHA agencies has been on the political agenda for nearly a decade.Footnote14 Mainly based on executive soft law, it was politically encouraged by the Council and the Comission and codified through bilateral agreements between the respective EU agencies. Prior to the hotspot approach, cooperation between Frontex and other EU agencies existed but was punctual and limited (interview 11). Following the first Working Arrangement in 2012, Frontex and EASO have intensified their cooperation in the wake of the 2015 migration crisis that is reflected in the conclusion of two further cooperation plans (Frontex-EASO Citation2017, Citation2019).

Both cooperation plans and the establishment of EU hotspots not only strengthened the role of individual agencies but also introduced the element of coordination among EU JHA agencies (interview 9 and 12). This linked-up approach designed for the post-disembarkation process envisaged a division of labor between Frontex (border control, identification and registration) and EASO (asylum procedures) with the view to make these administrative procedures more efficient and bring them in line with EU law. What is more, it turned out that both border checks and the assessment of asylum claims should not be treated as ‘completely separated procedures’ (interview 12). In fact, information collected by both agencies in the hotspots has increasingly been shared and used for intelligence, common reporting (e.g. on secondary movements) and their respective risk analysis (e.g. see the operational project ‘Processing Personal Data for Risk Analysis’ (PeDRA), (Frontex Citation2017): 29, interview 12). Frontex has also provided multilingual cultural mediators to facilitate registration and debriefing that have then also been used by EASO (interview 11 and 12). Moreover, Frontex and EASO have also strengthened the interoperability of their IT systems, notably in the areas of return (see also Frontex-Frontex-EASO Citation2019).

The plans have not only served as a basis for interagency cooperation, but also codified existing cooperation that has already been happening on the ground (interview 12 and 19). Frontex has often taken a proactive role in assessing operational procedures, developing policy responses and coordinating directly with EASO officials (interview 12). Moreover, Frontex and EASO officials have mutually assisted and ‘complemented each other’s work perfectly’ (interview 11 and 19). For example, families and unaccompanied minors who were eligible for relocation often refused fingerprinting. To overcome this problem, Frontex officers requested their EASO colleagues to explain the importance of identification and fingerprinting to these migrants. It was reported that in some cases, Frontex officers have bypassed Italian authorities and referred asylum seekers directly to EASO officers (interview 15).

Conclusion

Although the hotspot approach has been one of the key EU responses to the 2015 migration crisis, it has not received much systematic attention by EU scholars. Addressing this research gap, this article examined the establishment and implementation of the EU hotspot approach in Italy. Given the interest diversity and regulatory uncertainty among policy-makers, European political executives have set up a soft and vague hotspot framework that significantly enhanced the power of administrative actors, such as Frontex and EASO. Building on and extending the conceptual framework of the EAS literature, we showed how Frontex and EASO have strengthened both their independent administrative capacity and integration within the EAS. In particular, the extension of the EAS framework allowed us to include two important yet widely neglected features of administrative governance into the analysis, namely the level of precision of the agencies’ mandate and interagency cooperation. This approach enriches not only the literature on the EAS but also offers a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of how Frontex and EASO have contributed to the EU’s management of the migration crisis.

As the case of the hotspots demonstrates, legislative institutions both at the EU and national level have not played much of a role in shaping the trajectory of policy-making in times of crisis. Instead, executive actors have resorted to soft law and broad administrative mandates as means to depoliticise contentious issues and to overcome gridlock. We showed how Frontex and EASO used their broad mandates and growing resources to strengthen their integration within the EAS and in particular to promote their bilateral interagency cooperation. These developments have enhanced their monitoring role and discretionary power on the ground, which, in turn, reinforced direct forms of administration within the EU's multilevel governance system.

This crisis-driven agencification of the EAS also raises broader questions of the location of power within the politico-administrative order. Given the numerous crises in the last decade and their complex and contentious management, it seems likely that ‘lower level’ actors like EU agencies will continue to play an important part in the EU’s governance architecture (see also Pollak and Slominski Citation2021). Accordingly, issues such as power distributions and coordination between and within governance levels, their implications for policy content and accountability will remain on the scholarly agenda for the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under the project number P30703-G29. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For the purpose of this article, we use the term ‘migrants‘ for individuals who leave Southern Mediterranean countries on boats travelling irregularly towards Europe. By using the term migrant, we do not exclude the possibility that he or she may be a refugee or asylum seeker (for a similar approach see Human Rights Watch Citation2009, 22). Similarly, we use the term ‘crisis’ because the events have been perceived as an emergency that has to be dealt with (e.g. Boin, Ekengren, and Rhinard Citation2013). We do not engage with the debate whether the migration crisis has been ‘real’ or ‘socially constructed’.

2. Other disciplines are, however, a bit more prolific, including ethnographic research (Tazzioli Citation2018a), law (Casolari Citation2016; Fernández-Rojo Citation2019; Fernández-Rojo Citation2021; Ziebritzki and Nestler Citation2017; Tsourdi Citation2017), science and technology studies and European data infrastructures (Pelizza Citation2020), critical border studies (Papoutsi et al. Citation2019) or critical geography literature on migration (Tazzioli Citation2018b).

3. The interviews were conducted in Rome, Vienna or via phone in the period between February 2019 and January 2020 (see Annex 1).

4. Both financial and personnel resources have increased significantly in the last decades. Together, the 44 EU agencies have a total budget of 1.2 billion Euro (2016) and roughly 5,500 staff (Deloitte Citation2016, 3).

5. For the purpose of this article we conceive the mandate of an EU agency not necessarily in the form of a regulation but also in legally non-binding formats of Council conclusions, Commission Communications or other EU soft law.

6. In late 2015, the Commission launched legal procedures against Croatia, Greece, Malta, Hungary and Italy for not registering migrants and refugees in the EU-wide fingerprint database, Eurodac (European Commission Citation2015c). Ensuring proper implementation of existing EU law was part of the lowest common denominator consensus among EU member states (European Council Citation2018; European Commission Citation2015a, Citation2017; The Guardian Citation2015).

7. These measures were complemented by an increase of EU financial support (which partly funded the new tasks of the Frontex and EASO) and the promise (which never materialized) to strengthen the relocation of incoming migrants, a measure which was intended to show some solidarity with frontline member states (Trauner Citation2016; D’Angelo Citation2019).

8. For a similar approach in the field of EU return policy see (Slominski and Trauner Citation2021).

9. In February 2016, the Italian Ministry of the Interior in close collaboration with the European Commission, Frontex, Europol, EASO, UNHCR and IOM drafted SOPs, which defined various practices and responsibilities of actors within the hotspots. Due to its lack of legal obligation, enforcement of SOP provisions has remained a constant point of criticism by human rights NGOs.

10. While Northern member states have a strong interest in monitoring and enforcing the implementation of EU law, Southern member states are more concerned that imposing strong enforcement mechanisms might impinge their sovereignty.

11. For the period 2014–2020, Italy received 387.7 million euros under the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund and 266 million euros under the Internal Security Fund (European Commission Citation2018, 9).

12. See also European Commission, Progress Report on the Implementation of the hotspots in Italy, COM(2015) 679, 15 December 2015 and European Commission, Italy – State of Play Report, COM(2016) 85 ANNEX 3, 10 February 2016.

13. E.g. to reassure security check and return of illegal migrants, reinforcing implementation of readmission agreements and provide for international protection, the JHA Agencies appeared to be the best actor.

14. Following the JHA Council in October 2013, the Commission brought together officials from EU member states, the European External Action Service as well as numerous agencies such as Frontex, EASO, FRA, Europol or the European Maritime Agency with the view to strengthen interagency cooperation in EU border management (European Commission Citation2013). EU agencies in particular have been expected to play a stronger role in gathering and sharing of information of personal data as well as migration and smuggling routes (interview 7).

References

- Abbott, K.W., and D. Snidal. 2000. “Hard and Soft Law in International Governance.” International Organization 54 (3): 421–456. doi:10.1162/002081800551280.

- Amnesty International. 2016. “Hotspot Italy: How Eu’s Flagship Approach Leads to Violations of Refugee and Migrant Rights.“ London, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/EUR3050042016ENGLISH.PDF

- Ansell, C, and J Trondal. 2018. “Governing Turbulence: An Organizational- Institutional Agenda.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1 (1): 43–57. doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvx013.

- Bendel, P., and A. Ripoll Servent. 2018. “Asylum and Refugee Protection: EU Policies in Crisis.” In The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs, edited by A Ripoll Servent and F. Trauner, 59–69. London, UK: Routledge.

- Benz, A., A. Corcaci, and J. W. Doser. 2016. “Unravelling Multilevel Administration. Patterns and Dynamics of Administrative Co-ordination in European Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 999–1018. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1162838.

- Bickerton, C., D. Hodson, and U. Puetter. 2015. “The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post-Maastricht Era.” Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (4): 703–722. doi:10.1111/jcms.12212.

- Biermann, F., N. Guérin, S. Jagdhuber, B. Rittberger, and M. Weiss. 2019. “Political (Non-)reform in the Euro Crisis and the Refugee Crisis: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Explanation.” Journal of Europen Public Policy 26 (2): 246–266. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1408670.

- Blanc, F., and G. Ottimofiore. 2017. “The Interplay of Mandates and Accountability in Enforcement within the EU.” In Law Enforcement by EU Authorities. Implications for Political and Judicial Accountability, edited by M. Scholten and M. Luchtman, 272–304. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Boin, A., M. Ekengren, and M Rhinard, eds. 2013. The European Union as Crisis Manager: Patterns and Prospects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Börzel, T., and T. Risse. 2018. “From the Euro to the Schengen Crisis. European Integration Theories, Politicization, and Identity Politics.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 83–108. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310281.

- Bossong, R. 2019. “The Expansion of Frontex Symbolic Measures and Long-term Changes in EU Border Management.” In SWP Comment 2019. Berlin: German Institute for International and Security Affairs 1–8.

- Brandsen, T., and P.M. Karré. 2011. “Hybrid Organizations: No Cause for Concern?” International Journal of Public Administration 34 13 : 827–836. doi:10.1080/01900692.2011.605090.

- Buonanno, L. 2017. “The European Migration Crisis.” In The European Union in Crisis, edited by D. Dinan, N. Nugent, and W.E. Paterson, 100–130. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Camera dei Deputati. 2016. “Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sul Sistema di accoglienza, di identificazione ed esupulsione, nonché sulle condizioni di trattenimento dei migranti e sulle risorse pubbliche impregnate, 2016, Relazione sul sistema di identificazione e di prima accoglienza nell’ambito dei centri «hotspot». XVII Legislatura.” 3 May 2016, Doc. XXII-bis, N. 6, Stabilimenti tipografici Carlo Colombo, Rome.

- Casolari, F. 2016. “The EU’s Hotspot Approach to Managing the Migration Crisis: A Blind Spot for International Responsibility?” The Italian Yearbook of International Law 25: 109–134. doi:10.1163/22116133-90000109a.

- Ceccorulli, M. 2019. “Back to Schengen: The Collective Securitisation of the EU Free-border Area.” West European Politics 42 (2): 302–322. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1510196.

- Curtin, D. 2009. Executive Power of the European Union. Law, Practices, and the Living Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Curtin, D., and M. Egeberg. 2008. “Tradition and Innovation: Europe’s Accumulated Executive Order.” West European Politics 31 (4): 639–661. doi:10.1080/01402380801905868.

- D’Angelo, A. 2019. “Italy: The ‘Illegality Factory’? Theory and Practice of Refugees’ Reception in Sicily.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2213–2226. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468361.

- Deloitte. 2016. “How Do EU Agencies and Other Bodies Contribute to the Europe 2020 Strategy and to the Juncker Commission Agenda?.“ Accessed 27 02 2022.https://www2.deloitte.com/be/en/pages/public-sector/articles/EU_agencies_network.html

- Den Heijer, M., J. Rijpma, and T. Spijkerboer. 2016. “Coercion, Prohibition, and Great Expectations: The Continuing Failure of the Common European Asylum System.” Common Market Law Review 53 (3): 607–642.

- Dutch Council for Refugees. 2016. “The Implementation of the Hotspots in Italy and Greece.” Amsterdam, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/HOTSPOTS-Report-5.12.2016.pdf

- EASO. 2017. “EASO Enhances Support to Italian Asylum System.” https://www.easo.europa.eu/easo-enhances-support-to-Italian-asylum-system

- EASO. 2020a. “Multi-annual Programming 2021-2023.” Work Programme 2021, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/SPD2021-2023-adopted-by-MB_29.09.2020.pdf

- EASO. 2020b. “Amendment to the Operational and Technical Assistance Plan Agreed by EASO and Italy.” 11 December 2019, Valetta Harbour & Rome, https://easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Amendment%20to%20EASO%20Operating%20Plan%20for%20Italy%202020_0.pdf

- Egeberg, M., J. Trondal, and N. M. Vestlund. 2015. “The Quest for Order: Unravelling the Relationship between the European Commission and European Union Agencies.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (5): 609–629. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.976587.

- European Commission. 2013. “Communication on the Work of the Task Force Mediterranean.” COM(2013) 869 final

- European Commission (2015a). “A European Agenda on Migration.” COM(2015) 240 final, Brussels.

- European Commission (2015b). “Explanatory Note on the “Hotspot” Approach.” 15 July 2015, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2015/jul/eu-com-hotsposts.pdf

- European Commission (2015c). “Implementing the Common European Asylum System: Commission Escalates 8 Infringement Proceedings.” IP/15/6276, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-6276_en.htm

- European Commission. 2015f. “Progress Report on the Implementation of the Hotspots in Italy.” COM(2015) 679final, Brussels.

- European Commission. 2016. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. Annex 4, First Report on Relocation and Resettlement.” COM(2016) 165 final. Brussels, 16 March 2016.

- European Commission (2017). “Commission Contribution to the EU Leaders’ Thematic Debate on a Way Forward on the External and the Internal Dimension of Migration Policy.” COM(2017) 820 final.

- European Commission. 2018. “Progress Report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration.” Brussels, 16.5.2018, COM(2018) 301 final

- European Council. 2015. “European Council Meeting.” (25 and26 June 2015 Conclusions, Brussels.

- European Council. 2018. European Council Meeting. Brussels: Conclusions. 28 June 2018.

- European Court of Auditors. 2017. “Special Report EU Response to the Refugee Crisis: The ‘Hotspot’ Approach.” Report No. 6, Luxembourg.

- European Court of Auditors. 2019. “Asylum, Relocation and Return of Migrants. Time to Step up Actionto Address Disparities between Objectives and Results.” Report No. 24, Luxembourg.

- European Parliament. 2018. “EU Funds for Migration, Asylum and Integration Policies, Budgetary Affairs.” April 2018, PE 603.828, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/603828/IPOL_STU(2018)603828_EN.pdf

- Everson, Michelle, C. Monda, and E. Vos, edited by. 2014. “EU Agencies in between Institutions and Member States.” In Alphen aan den Rijn. Kluwer Law International.

- Fernández-Rojo, D. 2019. “Frontex, Easo and Europol: From a Secondary to a Pivotal Operational Role in the Aftermath of the “Refugee Crisis.” Caught You Red-Handed, 9 April 2019. Retrieved from https://caughtredhanded.ideasoneurope.eu/2019/04/09/frontex-easo-and-europol-from-a-secondary-to-a-pivotal-operational-role-in-the-aftermath-of-the-refugee-crisis/

- Fernández-Rojo, D. 2021. “EU Migration Agencies. The Operation and Cooperation of FRONTEX, EASO and EUROPOL.” Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Frontex. 2017. “Annual Activity.” Report 2016, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2017/aug/eu-frontex-activity-report-2016.pdf

- Frontex-EASO. 2017. “Cooperation Plan 2017-2018.“ Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Easo-frontex-cooperation-plan.pdf

- Frontex-EASO. 2019. “Cooperation Plan 2019-2021.“ Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/easo-frontex-cooperation-plan-2019-2021.pdf

- Groenleer, M. 2009. The Autonomy of the European Agencies. Delft: Eburon.

- Groenleer, M., M. Kaeding, and E. Versluis. 2010. “Regulatory Governance through Agencies of the European Union? the Role of the European Agencies for Maritime and Aviation Safety in the Implementation of European Transport Legislation.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (8): 1212–1230. doi:10.1080/13501763.2010.513577.

- The Guardian (2015). “Angela Merkel Wants to ‘Drastically Reduce’ Refugee Arrivals in Germany.” 14 December 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/14/angela-merkel-wants-to-drastically-reduce-refugee-arrivals-in-germany

- Hammargård, K., and E-K. Olsson. 2019. “Explaining the European Commission’s Strategies in Times of Crisis.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32 (2): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09557571.2019.1577800.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2019. “Grand Theories of European Integration in the Twenty-first Century.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (8): 1113–1133. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711.

- Horii, S. 2018. “Accountability, Dependency, and EU Agencies: The Hotspot Approach in the Refugee Crisis.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 37 (2): 204–230. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdy005.

- Human Rights Watch .2009. “Pushed Back, Pushed Around.“ Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/09/21/italy/libya-migrants-describe-forced-returns-abuse

- Human Rights Watch. 2016. “Greece: Refugee ‘Hotspots’ Unsafe, Unsanitary.“ 19 May, Accessed 27 02 2022. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/19/greece-refugee-hotspots-unsafe-unsanitary

- Italian Ministry of Interior. 2015. “Roadmap Italiana.” settembre 28 2015, Rome, https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2015/nov/italian-Roadmap.pdf

- Italian Ministry of the Interior. 2016. “Standard Operating Procedures Applicable in Italian Hotspots .” http://www.libertaciviliimmigrazione.dlci.interno.gov.it/sites/default/files/allegati/hotspots_sops_-_english_version.pdf

- Kassim, H., and J. Peterson. 2011. “Political Leadership in the European Commission.” paper presented at the 12th Biennial Conference of the European Union Studies Association, Boston, MA, 3–5 March 2011.

- Kriesi, H.-P. 2016. “The Politicization of European Integration.” Journal of Common Market Studies, Annual Review 54: 32–47. doi:10.1111/jcms.12406.

- Lavenex, S. 2018. “Failing Forward’ Towards Which Europe? Organized Hypocrisy in the Common European Asylum System.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (5): 1195–1212. doi:10.1111/jcms.12739.

- Lavenex, S., D. Lehmkuhl, and N. Wichmann. 2009. “Modes of External Governance: A Cross-national and Cross-sectoral Comparison.” Journal of European Public Policy 16: 813–833. doi:10.1080/13501760903087779.

- Lenaerts, K. 1993. “Regulating the Regulatory Process: ‘Delegation of Powers’ in the European Community.” European Law Review 18 (1): 23–49.

- Loschi, Chiara, and P. Slominski. 2021. ”Interagency Relations and the EU Migration Crisis: Strengthening of Law Enforcement Through Agencification?” In The Role of EU Agencies in the Eurozone and Migration Crisis. Impact and Future Challenges, edited by J. Pollak, and P. Slominski, 205–227, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Maccanico, Y. 2015. “The Italian Roadmap 2015 Hotspots, Readmissions, Asylum Procedures and the Re-opening of Detention Centres.“ Accessed 27 02 2022. www.statewatch.org/news/2015/dec/no-279-Italian-Road-Map-2015.pdf

- Maiana, F. 2016. “Hotspots and Relocation Schemes: The Right Therapy for the Common European Asylum System? EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy.“ Accessed 27 02 2022. https://eumigrationlawblog.eu/hotspots-and-relocation-schemes-the-right-therapy-for-the-common-european-asylum-system/

- Majone, G. 2002. “Delegation of Regulatory Powers in a Mixed Polity.” European Law Journal 3 (3): 319–339. doi:10.1111/1468-0386.00156.

- Majone, G. 2005. Dilemmas of European Integration: The Ambiguities and Pitfalls of Integration by Stealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, C. W. 2019. “Electoral Participation and Right Wing Authoritarian Success – Evidence from the 2017 Federal Elections in Germany.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 60: 45–271. doi:10.1007/s11615-018-00148-4.

- Ministry of the Interior [Italy]. 2015. “Roadmap Italiana.” 28 September 2015, Rome, http://www.asgi.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Roadmap-2015.pdf

- Ministry of the Interior [Italy]. 2016. Standard Operating Procedures, February 2016., http://www.libertaciviliimmigrazione.dlci.interno.gov.it/sites/default/files/allegati/hotspots_sops_-_english_version.pdf

- Monar, J. 2010. “Experimentalist Governance in Justice and Home Affairs.” In Experimentalist Governance in the European Union, edited by C. Sabel and J. Zeitlin, 237–260. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Neville, D., S. Sy, and A. Rigon. 2016. “On the Frontline: The Hotspot Approach to Managing Migration”. Brussels: Study for LIBE Committee.

- Niemann, A., and J. Speyer. 2018. “A Neofunctionalist Perspective on the ‘European Refugee Crisis’: The Case of the European Border and Coast Guard.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1111/jcms.12653.

- Ossege, C. 2016. European Regulatory Agencies in EU Decision-Making. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Papoutsi, A., J. Painter, E. Papada, and A. Vradis. 2019. “The EC Hotspot Approach in Greece: Creating Liminal EU Territory.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2200–2212. DOI:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468351.

- Pelizza, A. 2020. “Processing Alterity, Enacting Europe: Migrant Registration and Identification as Co-construction of Individuals and Polities.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 45 (2): 262–288. doi:10.1177/0162243919827927.

- Perkowski, N. 2016. “Deaths, Interventions, Humanitarianism and Human Rights in the Mediterranean ‘Migration Crisis.’.” Mediterranean Politics 21 (2): 331–335. doi:10.1080/13629395.2016.1145827.

- Peterson, J. 2017. “Juncker’s Political European Commission and an EU in Crisis.” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (2): 349–367. doi:10.1111/jcms.12435.

- Pollak, J., and P. Slominski. 2009. “Experimentalist but Not Accountable Governance? the Role of Frontex in Managing the EU’s External Borders.” West European Politics 32 (5): 904–924. doi:10.1080/01402380903064754.

- Pollak, J., and P. Slominski, edited by. 2021. In The Role of EU Agencies in the Eurozone and Migration Crisis. Impact and Future Challenges. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rijpma, J.J. 2012. “Hybrid Agencification in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice and Its Inherent Tensions: The Case of Frontex.” In The Agency Phenomenon in the European Union: Emergence, Institutionalisation and Everyday Decision-making, edited by M. Busuioc, M. Groenleer, and J. Trondal, 84–102. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Sabel, C. F, and J. Zeitlin, eds. 2010. Experimentalist Governance in the European Union: Towards a New Architecture. Oxford: UniversityPress.

- Sandholtz, W., and A. Stone Sweet. 2012. “Neo-Functionalism and Supranational Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of the European Union, edited by E. Jones, A. Menon, and S. Weatherill, 18–33. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, F. 2018. “European Integration (Theory) in Times of Crisis. A Comparison between the Euro and the Schengen Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (7): 969–989. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1421252.

- Scholten, M. 2017. “Mind the Trend! Enforcement of EU Law Has Been Moving to ‘Brussels’.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (9): 1348–1366. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1314538.

- Scipioni, M. 2018. “De Novo Bodies and EU Integration. What Is the Story behind EU Agencies’ Expansion?” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (4): 768–784. doi:10.1111/jcms.12615.

- Slominski, P., and F. Trauner. 2021. “Reforming Me Softly – How Soft Law Has Changed EU Return Policy since the Migration Crisis.” West European Politics 44 (1): 93–113. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1745500.

- Tazzioli, M. 2018a. “Containment through Mobility: Migrants’ Spatial Disobediences and the Reshaping of Control through the Hotspot System.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16): 2764–2779. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1401514.

- Tazzioli, M. 2018b. “The Temporal Borders of Asylum. Temporality of Control in the EU Border Regime.” Political Geography 64: 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.002.

- Thatcher, M., and A. Stone Sweet. 2002. “Theory and Practice of Delegation to Non-Majoritarian Institutions.” West European Politics 25 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/713601583.

- Trauner, F. 2016. “Asylum Policy: The EU’s Crisis and the Looming Policy Regime Failure.” Journal of European Integration 38 (3): 311–325. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1140756.

- Trondal, J. 2010. An Emergent European Executive Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Trondal, J. 2014. “The Rise of the European Public Administration: European Capacity Building by Stealth.” In Beyond the Regulatory Polity? the European Integration of Core State Powers, edited by P. Genschel and M. Jachtenfuchs, 166–186. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Trondal, J., and G.P. Peters. 2013. “The Rise of European Administrative Space: Lessons Learned.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (2): 295–307. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.746131.

- Tsourdi, E. 2017. “Hotspots and EU Agencies: Towards an Integrated European Administration?” EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy. Accessed 27 02 2022. https://eumigrationlawblog.eu/hotspots-and-eu/

- Vos, E. 2016. “EU Agencies and Independence.” In Independence and Legitimacy in the Institutional System of the EU, edited by D. Ritleng, 206–228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wonka, A., and B. Rittberger. 2010. “Credibility, Complexity and Uncertainty: Explaining the Institutional Independence of 29 EU Agencies.” West European Politics 33 (4): 730–752. doi:10.1080/01402381003794597.

- Zeitlin, J. 2016. “Experimentalist Governance in Times of Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 39 (5): 1073–1094.

- Ziebritzki, C., and R. Nestler. 2017. “‘Hotspots’ an der EU-Aussengrenze. Eine rechtliche Bestandaufnahme.” MPIL Research Paper Series No. 2017-17, Max Planck Institute for comparative and International law.

Appendix

Annex 1. List of Interviews and their institutional affiliations.