ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic has spurred a discussion about the role of the European Union (EU) in the governance of cross-border health threats. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is another major global health challenge that requires international collective action to be resolved. By using survey data from experts on AMR from 29 European countries, this paper investigates the support for an increase in the power of EU over AMR. Based on insights from collective action theory, we hypothesize that experts who believe that other countries free ride, will be more supportive of EU as a Leviathan in the European response to AMR. The results show that the experts generally were strongly in favor of expanding the authority of the EU over AMR. Furthermore, in line with theoretical expectations, experts who think that other countries free ride, are particularly supportive of more EU power over AMR.

Introduction

The role of the European Union (EU) in the response to cross-border health threats is currently at the heart of debates over European integration. This paper highlights the heterogeneity of preferences regarding the role of the EU in European health governance among experts in European public health policy. We explore the potential for an increase in the role of the EU in relation to the ‘silent pandemic’; antimicrobial resistance (AMR). As we will argue in this paper, the capacity of the EU to coordinate the efforts of its member states in addressing a significant public health issue like AMR is a critical case of functional integration to overcome collective action dilemmas.

Overuse of antibiotics in the health care and the agriculture sectors contributes to increasing prevalence of multi-resistant bacteria–super bugs–and AMR, causing some 700 000 deaths globally every year. If left unrestrained, AMR may cause as much as 10 million deaths annually and globally by 2050 and have economic ramifications on par with the financial crisis of 2009 (O’Neill Citation2014; Jonas et al. Citation2017).

While the science on how to prevent the emergence of multi-resistant bacteria is clear – reduce the use of antibiotics and improve infection protection and control (IPC) and hospital hygiene – political and institutional circumstances prevent the international collaboration to address AMR effectively and comprehensively. The governance and execution of a concerted, collective strategy to tackle AMR has proven to be extraordinarily challenging.

Indeed, this cross-border problem has the characteristics of an international collective action problem: there is little incentive for individual states to reduce the use of antibiotics. Governments even have incentives to free ride, i.e. to avoid efforts to reduce overuse in the pursuit of their short-term national interests (Laxminarayan et al. Citation2013; Hoffman et al. Citation2015; Jørgensen et al. Citation2016); for instance, the administrative effort to increase surveillance is considerable and costly, and allowing for extensive use of antibiotics may reduce sick days among the labor force. Thus, many scholars point to the need for a binding agreement enforced by an upper-level formal authority – a Leviathan for AMR is required to drive behavioral change (Padiyara, Inoue, and Sprenger Citation2018).

A key problem is thus that existing global governance arrangements on AMR rest solely on voluntary arrangements (Ruckert et al. Citation2020). The Global Action Plan, for example, invites WHO members to develop and implement National Action Plans but there is no formal sanctioning system in place to punish non-complying states (Baekkeskov et al. Citation2020). By contrast, the EU exercises some coercive power in the AMR field. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) grants the EU authority to regulate the use of antibiotics in the agricultural sector. In 2006, the EU introduced a ban for using antibiotics for growth promoters in farming.Footnote1 A more recent example is the EU’s ban on prophylactic use of antibiotics in farming (More Citation2020). In the public health sector, however, where ‘national competence’ is the constitutional norm, EU policy measures are restricted to informal mechanisms, such as surveillance of antibiotic resistance and antibiotics use; promotion of prudent use of antibioticsFootnote2; and information to the general public (e.g. the annual European antibiotic awareness day).Footnote3

In this paper, we analyse the support among AMR experts in the EU member states for a further increase in the power of the EU in the AMR field. Previous health emergencies in Europe have resulted in various kinds of policy reforms, as decision-makers realize the need for cooperation and collective action for mutual benefit (Brooks, de Ruijter, and Greer Citation2021). However, we argue that the cross-border nature of AMR will not necessarily by itself generate support for a transfer of power to the EU. Instead, prior theoretical and empirical work on collective action problems point to the role of perceived free riding as an important impetus for institutional change. As argued in seminal work by Yamagishi (Citation1986, Citation1988), actors who experience that co-players do not cooperate will support institutional solutions to the free rider problem.

We investigate how AMR experts in the EU member states assess the potential role of EU as a powerful actor – a Leviathan – in the AMR area, and more specifically which factors that influence whether they want the EU to have more power over AMR. There are several reasons why experts are particularly relevant in AMR policy. First, unlike citizens and even parliamentarians, experts have detailed knowledge about the nature of the AMR problem. While there is certainly merit in surveying parliamentarians or citizens in related surveys, national experts possess the knowledge and experience required to make good assessments of the AMR problem and various strategies to contain it.

Secondly, AMR experts constitute an epistemic community in the AMR sector. Senior national AMR experts in different countries, particularly in the EU, are frequently in contact with each other. The rather technical nature of the AMR problem may give such epistemic community leverage in the EU policy process (Zito Citation2001).

Third, AMR is a low-saliency political issue; it ranks low on most governments’ agenda and it does not to any significant extent shape voter preferences. AMR is also an issue which is primarily addressed by expert agencies such as public health institutes or agencies that tend to enjoy a high level of autonomy. These circumstances make the role of AMR experts more important compared to most other policy areas (Eckhard and Ege Citation2016; Yesilkagit and Van Thiel Citation2008).

Fourth, the experts are the operative agents in the AMR work. As senior public servants in the national public health agencies, they participate in national and cross-national governance arrangements to coordinate the AMR work. In sum, we argue that the attitudes of experts can have major ramifications on international policy development.

We hypothesize and test a potential relationship between belief about free riding among countries in Europe as regard to AMR and support of granting EU with more formal power over AMR. We make use of data generated by a web-survey to experts working on human or animal aspects of AMR in 29 European countries . In the survey, we gauge the experts’ views on giving the EU more power in the area of AMR and to what degree they believe that collaboration in the AMR field is obstructed by other countries not doing their part of the collective effort.

The analysis shows that most experts in both the public health and the veterinarian sectors are in favor of an increased EU power in the AMR field. Moreover, using panel data regression techniques, we confirm a link between free riding and support for more EU power to address AMR; experts believing that other countries fail to do their part in the fight against AMR are more positive towards an increase in EU power to tackle AMR. Our results also show that free riding has a stronger impact on the preference to increase the EU’s power among those who work in the human sector compared to the animal sector.

The following section outlines the theoretical context of the argument we pursue in the paper. Following a brief review of collective action theory, we explore the argument that experience of free riding makes actors more inclined to support institutional solutions to collective action problems. The theoretical analysis is followed by a presentation of the data and method used and of our empirical results. The paper closes with a discussion on the implication of the findings for European public health policy integration.

The struggle to govern antimicrobial resistance: insights from collective action theory

Cross-border health problems highlight the need for international cooperation and coordinating mechanisms that can promote collective action. In the mid-19th century, cross-border spread of disease gave rise to initial steps towards European integration to fostering the public health sector. (Fidler Citation2001). Today, the debate about the role of the EU in reducing the cross-border spread of disease illustrates the persistent need for international institutions to promote collective action (Brooks, de Ruijter, and Greer Citation2020).

Collective action problems occur when there is a conflict between the self-interest of individuals and collective interests, often preventing pareto-optimal (Olson Citation1965). These dilemmas come in different forms. Some collective action dilemmas involve multiple actors. Public goods are non-excludable resources not subject to subtraction. Since they are ‘open access’, they tend to be under-produced. That is the main argument in Mancur Olson’s seminal 1965 book The logic of collective action. Rational actors will not contribute to the provision of public goods unless there is ‘coercion or some other special device’ (Olson Citation1965, 3). Thus, the provision of public goods requires third-party interventions to be resolved.

Another type of collective action dilemmas is common goods. They are non-excludable and rival resources, and thus subject to subtraction. The dilemma here is that common resources tend to be overused, eventually causing a breakdown in provision. In Garett Hardin’s classic (Citation1968) article ‘The tragedy of the commons’, herdsmen’s overuse of a common grassland is used to illustrate the need for third-party interventions such as regulation or privatization.

Critique against the first-generation theories of collective action can be summarized in two brief points: first, that the theory is incorrect, and second, that it is irrelevant (Ostrom Citation1998; Biel and Thøgersen Citation2007; Jagers et al. Citation2019). Elinor Ostrom questioned the rationalistic approach in the early literature and saw a need for a behavioral, ‘bounded rationality’ theory of collective action (Ostrom Citation1998, Citation2000). A second group of critics argued that many current collective action problems are different from those studied by Hardin and Olson; they are essentially large-scale problems, traversing jurisdictional borders and generations (Biel and Thøgersen Citation2007; Jagers et al. Citation2019). These critics maintained that micro-level, deductive theories are of little help in understanding this type of large scale, complex, and socially embedded collective action problems.

As a result of this controversy, an extensive scholarship on the drivers of cooperation and defection in collective action situations has emerged, most prominently including studies of small-group interaction in public goods games or case studies of governance of ‘the commons’ (Ostrom Citation1990, Citation1998; Ostrom and Walker Citation2003). A key finding is that appropriators of common-pool resources, in contrast to the rational choice standard prediction, may cause actors to make credible commitments, thus overcoming the free-rider problem without relying on coercive external enforcement. Elinor Ostrom and her co-workers’ extensive studies of ‘the commons’ found ample support for the theory that free-rider problems can be solved in the absence of external enforcement (Ostrom Citation1990, Citation1998).

Numerous laboratory public good experiments have demonstrated the pitfalls of reliance on assumptions of rationalistic, utility-maximizing behavior. High levels of initial cooperation are observed in most types of public good games, signifying the failure of the zero-sum prediction of collective action (Fehr and Schmidt Citation2006; Gächter and Herrmann Citation2009). Another important finding which also challenges the rational choice prediction is that people generally are inclined to invest in costly punishments of free riders, should such a sanctioning system be available (Fehr and Gächter Citation2000).

Large-scale public health challenges, such as AMR or the containment of communicable diseases or pandemics, share the underlying conflict between individual and collective gain. The emerging scholarship on such large-scale dilemmas highlights stressors for cooperation such as anonymity, heterogeneity, lack of accountability, uncertainty, and cognitive limitations like difficulties with relating to people that you will never meet. These features have led researchers to the conclusion that large-scale dilemmas cannot be addressed without upper-level political institutions with significant coercive powers (Jagers et al. Citation2019; Harring, Jagers, and Löfgren Citation2021).

An additional aspect of large-scale dilemmas is that the underlying conflict between individual and collective gain operates both among individuals and among states. The main difference between the individual-level and state-level dilemmas is that in the latter, the interest of millions of individuals in any given jurisdiction is pursued by a small number of elected representatives and their administrators (Jagers et al. Citation2019). To understand this aspect of large-scale collective action, we need a behavioral theory of collective action applicable to politicians, public servants, and experts who make decisions affecting other people on a larger scale.

Such cases of ‘deputy’ based large-scale collective action are characterized by a combination of attributes of large-scale and small-scale dilemmas. Stressors known from large-scale collective action such as uncertainty and complexity are likely to influence the decision-making of politicians and experts, too. At the same time, the decision-making arrangements are more like small-scale interaction. Political leaders or experts from different countries bargaining over, for example, a new international treaty, interact multiple times and may (start to) know each other very much like the interaction enacted in repeated public good games. This suggests that similar cooperation-inducing mechanisms may be activated as those triggering cooperation and defection in small-scale dilemmas.

Free riding and institutions for collective action

As pointed out above, a key research result on the provision of public goods concerns the willingness of subjects to invest in costly punishments of free riders if such institutions are available. In an influential article in American Economic Review in 2000, Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter (Citation2000) show that people are inclined to invest in punishment even if it is costly and does not generate any private gains for the punisher, and that the credible threat of punishment can sustain levels of cooperation at high levels. However, prior to the work of Fehr and Gächter, Toshio Yamagishi had made important contributions to the theoretical and empirical study of institutional solutions to the free rider problem in small groups (Yamagishi Citation1986, Citation1988). His research was not focused on subjects’ usage of costly punishments or institutions for sanctioning, but rather on whether, and why, people would like to put such instruments in place.

In Yamagishi’s (Citation1986, Citation1988) pioneering research on public goods games, subjects were playing a standard repeated game. However, the experimental setup offered participants the opportunity to change the rules of the game by contributing to a sanctioning system that punished free riding behavior. Yamagishi found that high-trusting subjects contributed more in the initial public good game, while low-trust subjects invested more in the sanctioning systems. He concluded that free riding plays a role in building support for an institutional solution to collective action dilemmas; when people realize that individual behavioral change is an insufficient driver of collective action, it triggers a motivation to create a sanctioning system. By contributing to an institution that punish free riders and rewards cooperates, the net total benefit for the group can be increased (Yamagishi Citation1986, Citation1988).

Findings from laboratory public good experiments also demonstrate the prevalence of free riding as an impetus to support third-party interventions in the form of a leader. In a public goods experiment, Samuelson and Messick (Citation1995) gave subjects the opportunity to transfer their decision-making over the harvest of a common pool to a leader with the right to decide on behalf of the entire group. Based on this and other results they argue that people are willing to change the rules of the game if they notice overuse of the common good.

Findings also indicate that a costly sanctioning system can help gain support and contribute to increasing levels of contribution (Ostrom Citation1998; Gächter and Herrmann Citation2009). Thus, Gürerk and his associates compared the provision to a repeated laboratory social dilemma situation public good in the presence and absence of a sanctioning system. They found that overall levels of contribution were higher when a sanctioning´ system was in place. Importantly, they also noticed that participants began contributing to the sanctioning system after they had experienced free riding (Gürerk, Irlenbusch, and Rockenbach Citation2006).

In sum, theories of collective action point to factors that influence the support of an institutional solution to the free rider problem in small groups. In particular, numerous laboratory collective action experiments show that free riding increases individual support for third-party intervention to promote collective action. We argue that this research can help us understand certain types of large-scale action situation. If the decision-making arrangements are similar to small-scale interaction – repeated interaction between a limited number of actors – it is likely that free riding will trigger the same kind of mechanisms as have been found in small-scale collective action, i.e. that defection generates a preference for third-party intervention.

Two hypotheses about free riding and EU power over AMR

In this paper, we conceive instruments for sanctioning in public good games as equivalent to the EU as a Leviathan that can enforce collective action on the other. Our analysis will test the assumption that when humans see instances of free riding, they want institutions in place to prevent that behavior. Thus, the theory predicts that AMR experts who perceive free riding to be prevalent among other countries, will be more supportive of EU power in the area of AMR.

H1: If AMR experts believe that other countries free ride, they will support an increase of EU power over AMR.

Furthermore, Yamagishi’s model (Yamagishi Citation1986) predicts an increase in the support of a sanctioning system in the face of free riding if such institutions are absent. In the veterinarian sector, the EU already exercises formal authority in the AMR field. Thus, hypothetically, experts in this sector do not see more EU power as the solution to the free rider problem, at least not to the same extent as their colleagues in the public health sector. Since the EU lacks formal authority in the public health sector AMR policy, the theory predicts perceptions of free riding to be more strongly linked to support for more EU power among experts in this sector.

H2: The effect of free riding on support for an increase in EU power over AMR will be stronger among human side experts, as compared to experts in the animal sector.

Survey, variables, and Statistical methods

The survey

The survey data for this paper was generated by an online survey distributed to experts working with AMR in the EU member states, Norway and the UK. The sample was identified by asking relevant authorities in 29 countries to identify professionals involved in AMR-related work. We proceeded as follows:

We identified national authorities with responsibility for AMR in the target countries by scrutinizing EU documentation about ongoing AMR collaboration, asking country experts in our networks and by searching the web.

We approached the identified authorities and asked for the e-mail addresses to experts in charge of work on AMR in the human and/or animal sector.

We contacted the officials in charge via e-mail and informed about the research project and the survey. We asked them to provide us with e-mail addresses to AMR experts employed in their respective organizations. If they were unwilling to provide us with e-mail addresses, we gave them the option to assist us by distributing a link to the survey to AMR employees in their organization. We sent up to three reminders if we did not receive a response to our request.

The procedure resulted in 205 e-mail addresses to experts working with AMR in 21 countries.Footnote4 People in 17 countriesFootnote5 accepted to forward the survey to AMR employees in their respective authority. For nine countries, we both obtained e-mail addresses to some experts and assistance in distributing the survey to other officials.

We launched the survey in October 2020. We sent an e-mail with an individual link to the e-mail addresses. We also sent out an e-mail with a ‘shareable’ link to the contact persons who had agreed to forward the survey. After at least three reminders, we closed the survey in February 2021.

The share of respondents who started to take the survey and completed more than 80% of all question was 72%. About 20% completed less than 50% of all questions. In total, 151 respondents started taking the survey and 115 completed it. Out of these 115 respondents, 62 are experts in the animal sector and 53 in the human sector. About 57% work in a public agency, 20% in department/ministry while the remaining 22% answered ‘other’ organization. Most of the respondents have an educational background in veterinary medicine (49%), medicine (23) or natural science (10). About half of the respondents work more than half time with work related to AMR.

Variables

In this paper, we test whether free riding increases the support for a third-party institution charged with formal authority to enforce collective action. The equivalent of such institutions is an increase in supranational control in the EU, since that would make it possible to impose sanctions on countries that do not fulfill their obligations to the Union. To assess respondents’ support for more EU power in the AMR field, the survey included the following question: ‘What do you think about the current authority of EU over AMR policy on the [human/animal] side? EU authority over AMR policy should … ’. The response alternatives were (1) decrease, (2) remain the same, and (3) increase. In the analysis of data, the variable was dichotomized (decrease and remain = 0, increase = 1) as only two respondents selected the ‘decrease’ response alternative.

To assess the perception of free riding by other countries, respondents were asked to answer to which extent they agreed to the following statement. ‘Cooperation among the European countries in the AMR field is difficult because … Some countries are not doing their part in reducing the AMR problem’. The response scale ranged from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (7).

To assess respondents' concern about the AMR situation in Europe, the following question were asked: ‘In your opinion, and not considering your own country, how serious is the problem of AMR in Europe today?’. The response scale ranged from ‘Not at all serious’ (1) to ‘Very serious’ (7).

The survey included a question to measure concerns about the AMR situation in the country the respondent works in. It was phrased: ‘In your opinion, how serious is the problem of AMR in your country today?’. Like the question about the situation in Europe, the 7-point scale went from ‘Not at all serious’ to ‘Very serious’.

To assess respondents’ view on obstacles in relation to international AMR cooperation, the survey asked about their opinion on the following statement: ‘Some countries lack the necessary expertise on AMR’. The response scale ranged from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (7).

To account for differences in the composition of survey respondents in different countries, the survey consisted of several questions about respondent’s education and work. The empirical analysis of this paper makes use of questions about in which type of organization they work (public agency, department/ministry or other), how much they work with AMR (100%, more than 75%, 50–74%, 25–49%, or less than 25%) and their educational background (medicine, veterinary medicine, natural sciences, social sciences, or other).

The models also control for the country and the survey version. The country a respondent works in is included as level one in the hierarchical panel analysis. A variable on ‘survey distribution version’, i.e. direct or indirect distribution, is included in the regression to rule out that the outcome of the analyses is the result of differences in how the surveys were distributed.

Statistical methods

To find the most appropriate statistical technique to test our hypotheses, considering the hierarchical structure of the data, we performed the Hausman test. Based on the result of the test, we make use of random effect panel data models. To study the potential difference between experts in the human and animal sector, we analyze interaction terms between the free riding variables and all other variables in the model.

Results

Descriptive results

The EU is popular among the experts surveyed, at least in terms of their support of giving the EU more power in the AMR field. Of 120 responses, only two experts – both in the veterinarian sector – were in favor of decreasing the power of EU over AMR. The remaining 61 animal side experts were divided between 19 being in favor of the EU remaining the same power and 42 in favor of increasing EU power in AMR. On the human side, 10 were in favor of the same power and 45 of increasing EU power. Thus, in total, 87 want more EU power, 29 want to keep EU power as it is, and two want to decrease EU power in the AMR field.

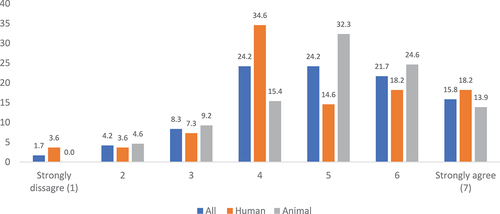

shows the distribution of responses to the free riding question among all respondents and divided between human and animal side respondents. Most respondents think that some countries are not doing their due part of the work to address the AMR problem. The mean on the 7-point scale is 4.9 (95% confidence interval (C.I.) 4.7–5.2). The difference between human and veterinarian side respondents is quite small. The mean is 4.8 (C.I. 4.4–5.2) for the human side and 5.0 (C.I. 4.7–5.4) for the animal side. More human side respondents choose the middle category (34,6%), as compared to animal side respondents (15,4%).

Figure 1. Perceptions of free riding among all, human side and animal side respondents, respectively (percent).

First, we consider the simple bivariate association between free riding and support for more EU power in the AMR field. Among the 19 respondents who strongly agreed (response alternative 7) to the statement that some countries are not doing their part in reducing the AMR problem, all but one are in favor of giving EU more power in this area (95%). Also, among the respondents who selected six on the same scale, 19 out of 26 respondents favor more EU power over AMR (73%).

Let us now look at respondents who do not agree as much to the statement that some countries are not doing their part, i.e. those who selected the response alternatives 1–5 on the seven-point-scale. Out of these 75 respondents, 64% (n = 48) are in favor of more EU power over AMR. The ‘pro-EU’ group is still in majority, albeit with a much lower share as compared to those who selected 6 or 7 on the response scale.

These bivariate results suggest a relationship between beliefs about free riding and attitudes towards more EU power over AMR. The next section will consider this link further, taking into account the hierarchical structure of the data as well as controlling for potential confounders.

Regression analysis

includes results for two random effect panel data models, the value on the dependent variable is one if the expert thinks that EU authority over AMR policy should increase and the panel data indicator variable is the country where the expert works (n = 29).Footnote6

Table 1. Coefficients from a random effect panel data model where the dependent variable is one if a bureaucrat thinks that EU authority over AMR policy should increase. Standard deviations in the parentheses.

Model 1 shows an association between the perception that other countries are not doing their part to address the AMR problem and supporting more EU power in this area. The association is highly significant and positive under control for several confounders. Thus, for each step on the scale, the probability to wishing increase EU power in the AMR-related question increases by about 7 percentage points if a bureaucrat believes that free riding happens, indicating that the impact of perceived free riding on support for increased EU power over AMR is sizeable.

Another finding, significant on the 0.10-level, is that respondents working in the human sector are more in favor EU power over AMR, as compared to respondents in the veterinarian sector. In fact, the probability of supporting more EU power increases by 15 percentage points if an expert is working in the human sector.

The variable measuring perceived AMR situation in the own country and perception about the prevalence of MR expertise of their countries are not significantly related to support for increasing EU power over AMR. The same results are found for the variables measuring respondents’ characteristics such as place of work and work time devoted to AMR; these factors are not significantly related to support an increase in EU power.

In Model 2, we add a variable measuring the perceived severity of the AMR problem in Europe to investigate if the link between beliefs about free riding and an increase in the support for more EU power in the AMR field is the result of a concern about the AMR situation in Europe. If adding this variable to the model removes or substantially reduces the association between our focal variables, this would indicate that experts want more EU power because they think free riding exacerbates the AMR problems in Europe. The coefficient is insignificant, indicating that the general severity of AMR in Europe does not have any significant impact on the support for more EU power in the AMR field. Furthermore, the coefficient for the association between perceived free riding and the outcome variable increase in EU power is unaffected by the inclusion of this variable.

reports the interaction terms where ‘other countries free-ride’ interacts with all other explanatory variables. A statistically significant interaction term reveals that there is a heterogeneous effect of the perception of free riding on the support for increased power for the EU. For example, if the interaction term between perceived free riding and perceived seriousness of the AMR situation in the own country is positive, the effect of free riding on the support for the EU is stronger among those that perceive the AMR situation in their own country to be severe.

Table 2. Results from a random parameter model with interaction terms with the variable ‘other countries free ride’. Standard deviations in the parentheses.

However, only two of the interaction terms are statistically significant. First, the effect of perceived free riding on the support for increased power to the EU is stronger among those who work in the human sector compared with those who work in the animal sector. This result confirms our second hypothesis that the AMR human side experts will be more in favor of an increase in EU power over AMR than their colleagues in the animal sector. Secondly, while the total effect on more EU power is negative if an expert believes that other countries lack of expertise, the effect of free riding on the support for the EU is a stronger among those who believe that other countries lack of experience.

Conclusions

AMR is a major challenge to global health. In order to avoid the tragedy of a post-antibiotic era a massive reduction in the human and veterinarian use of antibiotics is urgently needed. The dilemma is that AMR requires that all countries – or at least the vast majority – join forces in this global struggle, despite the risk of free riding which is present is almost all cases of international cooperation.

In the absence of a much-needed binding global framework on AMR, the EU has a significant role in European AMR coordination. However, while the EU exercises formal authority to regulate veterinarian use of antibiotics, it lacks regulatory power over antibiotic prescription and consumption on humans (EU, 2005). An important question is thus if an increase of the EU power over AMR would be supported by key actors in the member states.

The descriptive results of the paper demonstrate that experts active in AMR across the European continent generally tend to support more EU power over AMR. In our e survey of 120 AMR experts in the EU member countries, 87 want to transfer more power to the EU in this area. These findings highlight the perceptions of a strategically placed epistemic community – a group of networked national AMR experts – and their potential influence on the policy process in the EU (Haas Citation1992). There is a debate about the mechanisms by which such networks may influence on policy and how the knowledge of experts is used by policy-makers (Galbreath and McEvoy Citation2013; Kourtelis Citation2021). In the case of AMR, epistemic communities of experts can bring about EU policy innovation by defining members states’ interests and thereby influence the actions by national politicians (Adler and Haas Citation1992). Furthermore, the Covid crisis has challenged traditional assumptions about the role of the EU in European health policy, which potentially could increase the policy impact of epistemic communities (Zito Citation2001).

One decisive factor for the extent to which experts want more EU power is what they think about other countries’ contribution to the solution of the problem. Experts are more in favor of increasing EU power over AMR if they think that other countries are not doing their fair share, i.e. free riding, in the fight against AMR. The impact is sizeable; for every step on the seven-point-scale measuring belief about free riding, the likelihood of wanting to increase EU is increased by 7 percentage points. The data thus provide firm support for the first hypothesis; free riding drives support for an increase of EU power in the AMR field.

The second hypothesis is also supported. It predicts that the effect of free riding on support for more EU power will be stronger among experts in the (human) public health sector compared to those who work in the animal sector. There is a significant interaction between the free riding variable and the human sector variable. An interpretation of this result could be related to what was previously discussed; the veterinarian sector is already highly regulated by the EU and experts in that sector might have doubts as to whether giving Leviathan even more power would change the AMR situation for the better.

Another finding is that the link between free riding and support for more EU power over AMR is decupled from the public servants’ sense of the severity of the AMR problem. This finding challenges the narrative of previous theoretical accounts on free riding and support for institutions for collective action. Yamagishi (Citation1988) emphasizes that the demand for such institutions is the result of the recognition that the problem cannot be resolved effectively without some institutional control. That having been said, the fact that the perceived severity of the AMR problem does not seem to account for the association between free riding and support for the EU may indicate that experts want the EU to have power, not necessarily because they fear AMR but more because they dislike free riding.

As already stated, European AMR governance involves some unique traits in the focus on international and multisectoral collaboration. Yet, it also speaks to the broader literature on European integration (Wiener, Börzel, and Risse Citation2019). We believe that theories of neofunctionalism, starting with Haas (Citation1958), provide a fruitful lens for making sense of the integrative aspects of European AMR governance. EU legislation concerning the use of antibiotics to animals (most recently amended in 2022), the several networks for sharing best practices and harmonizing policy alignments (Brown et al. Citation2020), and the current development of a ‘European Health Union’ (Anderson, Forman, and Mossialos Citation2021) certainly speak to functional spillovers between and within states, to increasing European-level transactions and allegiances, and high levels of regulatory complexity.

The AMR problem traverses the domestic–international distinction. Each country has distinctive challenges in relation to AMR, and therefore various reasons for joining the integrative efforts at within the European level, which alludes to intergovernmentalism (Nugent Citation2006) rather than neofunctionalism. While the issue of AMR, and more specifically whether AMR experts prefer more EU-level authority when other countries free-ride, clearly evokes the wider question of European integration, we believe a fruitful avenue for further research would be to describe and explain how and why AMR governance is an example of these important paradigms.

An important question is the extent to which the findings of this paper travel to other kinds of cross-border health threats. The role of the EU in response to European health emergencies is under development, as well as under academic scrutiny and debate. Many argue that the Covid-19 pandemic has provided momentum for an expansion of EU authority in the public health domain. There are also signs of an improvement in the capacity of the EU to handle a state of ‘constant emergency’, as the EU has learned from previous health emergencies (Wolff and Ladi Citation2020).

In this paper, we point to the need to consider heterogeneity of preferences among key actors when analyzing the potential for EU health policy expansion. As pointed out before, the window of opportunity provided by Covid-19 will be closed if member states do not see the benefit of such transfer of power (Brooks, de Ruijter, and Greer Citation2020). It is likely that different actors across Europe may draw different conclusions from previous interactions over the management of European health emergencies. When it comes to the lessons learnt from Covid-19, some may point to examples of coordination and cooperation, such as the joint purchasing of Covid vaccine, which stands in contrast to experience of competition among member states over scares 2009 A(H1N1) vaccine deliveries (van Schaik, Jørgensen, and van de Pas Citation2020; Wolff and Ladi Citation2020). Others may highlight incidences of state-centric ‘Corona nationalism’, such as closed boarders and competition over medical equipment (Bump, Friberg, and Harper Citation2021). It is not self-evident that the former conclusions will translate into action. On the contrary, the experience of defection may signify the need of an institutional solution to the free rider problem and thus pave the way for long-term EU cooperation for mutual benefit.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was provided by the Swedish Research Council grant number 2018-01330 and the Centre for Antibiotic Research (CARE), at the University of Gothenburg. We are grateful for the constructive and helpful comments by the reviewers. We would like to thank LORE at the University of Gothenburg for their excellent research assistance in administrating the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003, EU (2005).

2. E.g. the Antimicrobial Resistance and causes of Non-prudent use of Antibiotics (ARNA) project, funded by the EU. The project’s objective is to promote prudent use of antibiotics in the EU,

4. Belgium (13), Bulgaria (7), Estonia (4), Finland (59), France (27), Greece (16), Ireland (7), Italy (9), Latvia (1), Lithuania (6), Luxemburg (10), Poland (7), Portugal (2), Romania (2), Slovenia (5), Spain (3), Sweden (3), the Czech Republic (3), Germany (3), the UK (6), Austria (3).

5. Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Germany, Hungary, and France.

6. In all the regressions, the standard errors are adjusted for the 29 clusters in the panel indicator variable ‘country’.

References

- Adler, E., and P. M. Haas. 1992. “Conclusion: Epistemic Communities, World Order, and the Creation of a Reflective Research Program.” International Organization 46 (1): 367–390. doi:10.1017/S0020818300001533.

- Anderson, M., R. Forman, and E. Mossialos. 2021. “Navigating the Role of the EU Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) in Europe and Beyond.” The Lancet Regional Health–Europe 9, 100203. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100203.

- Baekkeskov, E., O. Rubin, L. Munkholm, and W. Zaman. 2020. “Antimicrobial Resistance as a Global Health Crisis.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford Encyclopedia of Crisis Analysis Oxford University Press. Oxford Research Encyclopedias.

- Biel, A., and J. Thøgersen. 2007. “Activation of Social Norms in Social Dilemmas: A Review of the Evidence and Reflections on the Implications for Environmental Behaviour.” Journal of Economic Psychology 28 (1): 93–112. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2006.03.003.

- Brooks, E., A. de Ruijter, and S. L. Greer. 2020. “COVID-19 and European Union Health Policy: From Crisis to Collective Action.” In Social Policy in the European Union: State of PlayFacing the Pandemic, edited by B. Vanhercke, S. Spasova, and B. Fronteddu. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) and European Social Observatory (OSE), 33-52.

- Brooks, E., A. de Ruijter, and S. L. Greer. 2021. “Another European Rescue of the Nation-State?” Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. edited by Greer, Scott L., King, Elizabeth J., Peralta, Andre, and Fonseca, Elize Massard de. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Brown, H. L., J. L. Passey, M. Getino, I. Pursley, P. Basu, D. L. Horton, and R. M. La Ragione. 2020. “The One Health European Joint Programme (OHEJP), 2018–2022: An Exemplary One Health Initiative.” Journal of Medical Microbiology 69 (8): 1037. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.001228.

- Bump, J. B., P. Friberg, and D. R. Harper. 2021. “International Collaboration and Covid-19: What are We Doing and Where are We Going?” bmj 372, n180. doi:10.1136/bmj.n180.

- Eckhard, S., and J. Ege. 2016. “International Bureaucracies and Their Influence on Policy-making: A Review of Empirical Evidence.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 960–978. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1162837.

- Fehr, E, and S Gächter. 2000. “Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments.” The American Economic Review 980–994.

- Fehr, E., and S. Gächter. 2000. “Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments.” American Economic Review 90 (4): 980–994. doi:10.1257/aer.90.4.980.

- Fehr, E., and K. M. Schmidt. 2006. “The Economics of Fairness, Reciprocity and Altruism–experimental Evidence and New Theories.” Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity 1: 615–691.

- Fidler, D P. 2001. “The Globalization of Public Health: The First 100 Years of International Health Diplomacy.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79: 842–849.

- Gächter, S., and B. Herrmann. 2009. “Reciprocity, Culture and Human Cooperation: Previous Insights and a New Cross-cultural Experiment.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364 (1518): 791–806. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0275.

- Galbreath, D. J., and J. McEvoy. 2013. “How Epistemic Communities Drive International Regimes: The Case of Minority Rights in Europe.” Journal of European Integration 35 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.692117.

- Gürerk, Ö., B. Irlenbusch, and B. Rockenbach. 2006. “The Competitive Advantage of Sanctioning Institutions.” Science 312 (5770): 108–111. doi:10.1126/science.1123633.

- Haas, E. 1958. Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces, 1950-1957. California: Stanford University Press.

- Haas, P. M. 1992. “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination.” International Organization 46 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1017/S0020818300001442.

- Hardin, G. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162 (3859): 1243–1248.

- Harring, N., S. C. Jagers, and Å. Löfgren. 2021. “COVID-19: Large-scale Collective Action, Government Intervention, and the Importance of Trust.” World Development 138: 105236. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105236.

- Hoffman, S. J., G. M. Caleo, N. Daulaire, S. Elbe, P. Matsoso, E. Mossialos, Z. Rizvi, and J.-A. Røttingen. 2015. “Strategies for Achieving Global Collective Action on Antimicrobial Resistance.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93 (12): 867–876. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.153171.

- Jagers, S. C., N. Harring, Å. Löfgren, M. Sjöstedt, F. Alpizar, B. Brülde, D. Langlet, A. Nilsson, B. C. Almroth, and S. Dupont. 2019. “On the Preconditions for Large-scale Collective Action.” Ambio 49(7), 1282-1296. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01284-w.

- Jonas, O. B., A. Irwin, F. C. J. Berthe, F. G. Le Gall, and P. V. Marquez. 2017. “Final Report. Drug-resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future: Vol. 2.” In HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative. Washington DC. World Bank Group.

- Jørgensen, P. S., D. Wernli, S. P. Carroll, R. R. Dunn, S. Harbarth, S. A. Levin, A. D. So, M. Schlüter, and R. Laxminarayan. 2016. “Use Antimicrobials Wisely.” Nature News 537 (7619): 159. doi:10.1038/537159a.

- Kourtelis, C. 2021. “The Role of Epistemic Communities and Expert Knowledge in the European Neighbourhood Policy.” Journal of European Integration 43 (3): 279–294. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1739031.

- Laxminarayan, R., A. Duse, C. Wattal, A. K. M. Zaidi, H. F. L. Wertheim, N. Sumpradit, E. Vlieghe, et al. 2013. “Antibiotic Resistance—the Need for Global Solutions.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 13 (12): 1057–1098. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9.

- More, S. J. 2020. “European Perspectives on Efforts to Reduce Antimicrobial Usage in Food Animal Production.” Irish Veterinary Journal 73 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/s13620-019-0154-4.

- Nugent, N. 2006. The Government and Politics of the European Union (6th Ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Neill, J. 2014. “Review on Antimicrobial Resistance.” Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations

- Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- Ostrom, E. 1998. “A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action: Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1997.” The American Political Science Review 92 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/2585925.

- Ostrom, E. 2000. “Collective Action and the Evolution of Social Norms.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (3): 137–158. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.137.

- Ostrom, E., and J. Walker. 2003. Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons for Experimental Research. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Padiyara, P., H. Inoue, and M. Sprenger. 2018. “Global Governance Mechanisms to Address Antimicrobial Resistance.” Infectious Diseases: Research and Treatment 11: 1178633718767887.

- Ruckert, A., P. Fafard, S. Hindmarch, A. Morris, C. Packer, D. Patrick, S. Weese, K. Wilson, A. Wong, and R. Labonté. 2020. “Governing Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review of Global Governance Mechanisms.” Journal of Public Health Policy 41 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1057/s41271-019-00190-5.

- Samuelson, C. D., and D. M. Messick. 1995. “When Do People Want to Change the Rules for Allocating Shared Resources.” In Social Dilemmas: Perspectives on Individuals and Groups ed. David A. Schroeder. Westport, CT: 143–162.

- van Schaik, L., K. E. Jørgensen, and R. van de Pas. 2020. “Loyal at Once? The EU’s Global Health Awakening in the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of European Integration 42 (8): 1145–1160. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1853118.

- Wiener, A., T. A. Börzel, and T. Risse. 2019. European Integration Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wolff, S., and S. Ladi. 2020. “European Union Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic: Adaptability in Times of Permanent Emergency.” Journal of European Integration 42 (8): 1025–1040. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1853120.

- Yamagishi, T. 1986. “The Provision of a Sanctioning System as a Public Good.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1): 110. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.110.

- Yamagishi, T. 1988. “The Provision of a Sanctioning System in the United States and Japan.” Social Psychology Quarterly 51 (3): 265–271. doi:10.2307/2786924.

- Yesilkagit, K., and S. Van Thiel. 2008. “Political Influence and Bureaucratic Autonomy.” Public Organization Review 8 (2): 137–153. doi:10.1007/s11115-008-0054-7.

- Zito, A. R. 2001. “Epistemic Communities, Collective Entrepreneurship and European Integration.” Journal of European Public Policy 8 (4): 585–603. doi:10.1080/13501760110064401.