ABSTRACT

This article explores enlargement discourses as a way to gauge the broader dynamics of European integration since the historical Eastern accession round. Studying debates in the national parliaments of France, Germany, Hungary, and Poland between 2004 and 2017, we use qualitative frame analysis to discern three types of political discourse on EU widening: normative discourses stress the EU’s soft power and its moral obligation towards candidate countries; pragmatic discourses concentrate on conditionality and enlargement as a stabilisation tool; and institutional discourses emphasize efficiency and state capacity. Our findings point to a diminished relevance of the external projection of EU values and practices and instead a stronger introspective emphasis on democratic quality and internal consolidation. Overall, discourses on EU enlargement thus mirror a broader shift in the perceived nature and direction of European integration.

Introduction

European integration has been marked since its inception by an underlying tension between widening and deepening. These two dimensions are variously viewed as complementary, with European Union (EU) enlargement facilitating the extension of sectoral integration, or as competing, whereby the addition of new members threatens the political and socio-economic cohesion of the Union (Kelemen, Menon, and Slapin Citation2014). Studies examining political conflict around European integration regard enlargement as a ‘constitutive issue’ that touches the fundamental features of the EU polity (Braun, Hutter, and Kerscher Citation2016). This is particularly true for the Eastern enlargement of 2004/07, which sparked renewed interest in the relationship between widening and deepening and its implications for the nature and future of European integration. Debates on EU enlargement thus offer a window into the broader dynamics and motivations driving the European integration process. By positioning themselves on the depth and rationale of the Union’s engagement with accession candidates, political actors in member states reveal contrasting visions and priorities about the EU’s internal functioning and its engagement with its immediate neighbourhood.

Early analyses of the Eastern enlargement offered an optimistic take on the EU’s ability to promote ‘democratisation by integration’ (Dimitrova and Pridham Citation2004). At the same time, scholars expressed apprehension before the long-term sustainability of externally driven democratic reforms (Sadurski Citation2004; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004; Vachudova Citation2005). Recent trends of democratic backsliding among newer member states and candidate countries alike (Sedelmeier Citation2014; Kelemen Citation2017; Bieber Citation2018) appear to confirm these initial concerns. Yet while an extensive literature has evaluated the political and institutional impact of the Eastern enlargement (Best Citation2010; Hertz and Leuffen Citation2011; Toshkov Citation2017; Zhelyazkova, Kaya, and Schrama Citation2017), there is little systematic analysis of enlargement debates concerning the remaining candidate countries. The limited literature in this field consists largely of case studies, which restrict the ability to draw conclusions that go beyond the reasons driving individual countries to support (or oppose) further enlargement (Ker-Lindsay et al. Citation2017; Töglhofer and Adebahr Citation2017; Wunsch Citation2017). Our study seeks to fill this gap by asking two main research questions: how have political discourses on enlargement developed after 2004? And to what extent does this evolution indicate a broader transformation of European affairs?

Focusing on the national parliaments of four member states – France, Germany, Hungary, and Poland – our study analyses the main motifs underpinning political discourses on enlargement in the post-2004 period. National parliaments have become important intermediary actors linking the European sphere to domestic concerns and particularities. Although their direct influence on the EU’s enlargement process remains limited, they represent a forum for debate and position-taking that integrates domestic public opinion on enlargement and constrains the behaviour of national executives at the European level. By mapping political discourses on enlargement across four different institutional contexts and combining founding members with more recent entrants, we seek to establish broader patterns of discursive framing and to examine the linkages between national discourses on enlargement and the overall direction of European integration.

Our empirical analysis builds on a comprehensive, original dataset of over 350 hand-coded statements from 120 plenary debates on enlargement towards the Western BalkansFootnote1 held in our four selected countries between 2004 and 2017. We employ qualitative frame analysis to differentiate and unpack three categories of political discourse: normative discourses comprise an emphasis on democracy promotion and historical commitment; pragmatic discourses address issues of conditionality and stabilisation; and institutional discourses focus on internal consolidation and administrative efficiency. Across all four countries, pragmatic discourses dominate, with a smaller share of discourses related to institutional matters, and only a marginal proportion of normative discourses. The national parliaments of founding members France and Germany focus primarily on the institutional impact of further widening and the importance of strict conditionality. Hungarian Members of Parliament (MPs) view enlargement mainly as a stabilising tool as well as, somewhat idiosyncratically, a means to promote the rights of Hungarian minorities in the neighbourhood. Among Polish MPs alone, we find an emphasis on the theme of democracy promotion. Overall, our findings show a clear prevalence of concerns relating to institutional efficiency and full compliance with membership requirements that dominates over a more marginal discourse related to the external projection of EU values and a historical commitment to candidate countries.

Our study makes several contributions to the literatures on EU enlargement and European integration more generally. First, we posit EU enlargement as a core policy and a driving factor of the integration process. We demonstrate that debates on widening mirror the more general state and transformation of European integration, with a notable discursive emphasis post-2004 away from an ambition to export EU values beyond its borders towards a focus on internal consolidation and procedural matters. Second, we speak to a growing interest in the role of national parliaments in EU studies by exploring divergences and common patterns regarding how national parliamentarians in four widely varying contexts position themselves in debates on EU widening. By connecting a discourse-based analysis of enlargement debates to the shifting institutional balance in the area of widening, we provide insights into more general changes in the dynamics of European integration and the EU’s engagement with its neighbourhood.

We begin by articulating our approach within the broader literature on the role of national parliaments in European integration and discourse-based studies of EU enlargement. We then proceed to unpack enlargement discourses from a theoretical perspective and derive the framing categories that guide our empirical analysis. Next, we provide an overview of our research design and data. Our empirical section uses qualitative frame analysis to distil and substantiate different political discourses related to EU enlargement towards the Western Balkans. We conclude by reflecting on the political implications that national parliamentary discourses on enlargement hold for our understanding of the current state and future of European integration.

A discourse-based approach to national parliaments and EU enlargement

European integration has proceeded through a succession of enlargement rounds, gradually extending membership from the initial six to temporarily 28 EU member states.Footnote2 The addition of new member states implies a thorough transformation of their political and economic structures, but also of the EU itself (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2005; Sjursen Citation2012). Each enlargement round has been accompanied by institutional reform and an ongoing reflection on the EU’s ambitions as well as its limitations (Cameron Citation2004). EU enlargement is therefore not merely the most prominent among the EU’s external policies, but lies at the very core of the EU’s changing identity. As a result, enlargement is among the most contested dimensions of European integration.

Contestation was particularly high around the EU’s Eastern enlargement, which was historical in its magnitude, but also in its symbolic nature. Whereas previous enlargement rounds had each added a small number of generally well-prepared new members, the ‘big bang’ accession of 2004/2007 comprised ten post-communist countriesFootnote3 that had only recently transitioned towards democratic governance and market economies. The stark political and socio-economic divergence between old and prospective new member states triggered anxieties over the impact of such a major transformation to the EU’s membership. Economic concerns including the influence of the Central and Eastern European (CEE) accession upon labour markets, social welfare systems, and the redistribution of EU structural funds featured prominently in both political and academic discussions (Gábor Citation2006; Kandogan Citation2000; Kvist Citation2004). Identity was also a major issue of debate: whereas some feared that the Eastern enlargement would further complicate the emergence of a common European identity (Fuchs and Klingemann Citation2002), others contested the existence of a cultural divide between Eastern and Western Europe on empirical grounds (Laitin Citation2002).

Against this backdrop, we seek to map the evolving perception of EU enlargement as a political project in the post-2004 period. Since the historical Eastern enlargement round, both popular support for further widening and elite commitment towards admitting new members have further dwindled, giving way instead to a growing nationalisation (Hillion Citation2010) and politicisation of enlargement-related questions (Bélanger and Schimmelfennig Citation2021). Institutionally speaking, these developments have empowered member states in the bargaining process over future accessions (Ker-Lindsay et al. Citation2017; Wunsch Citation2017), relegating the previously dominant European Commission to the side-lines. Although national governments take centre-stage during the membership negotiations themselves, national parliaments hold a formidable veto power given the need for each of them to ratify any new accession treaty. Moreover, they hold a crucial communication function vis-à-vis citizens when it comes to articulating national perspectives on EU-level policy-making.

We therefore focus our empirical analysis on enlargement debates in national parliaments as important arenas connecting EU-level debates to domestic public opinion. The role of national parliaments in EU governance has recently garnered growing interest (Kinski Citation2020; Winzen Citation2022). Following a relative decline in their relevance due to the strengthening of EU-level competences, national parliaments have been able to forge new roles for themselves, acting as ‘multi-arena players’ (Auel and Neuhold Citation2017) that combine powers of scrutiny, networking, and gatekeeping related to subsidiarity (Sprungk Citation2013). Studies of national parliamentary activity in the EU context frequently address the variation in the uptake of new competences granted in particular by the Lisbon Treaty (Auel and Christiansen Citation2015). Empirical comparisons between parliamentary behaviour in different member states tend to conclude that such variation is related less to differences in institutional strength, but rather to party politics (Auel and Raunio Citation2014) as well as distinct motivations driving national parliamentarians to become active in EU-level affairs (Auel, Rozenberg, and Tacea Citation2015; Borońska-Hryniewiecka Citation2021). Similarly, the common distinction between ‘working’ and ‘debating parliaments’ was not found to explain differences in the frequency or the main topics of national parliaments’ EU-related plenary debates (Auel and Raunio Citation2014, 24).

Adopting a discourse-focused approach, our study takes a somewhat different perspective: rather than striving to explain variation in parliamentary behaviour, we focus on unpacking the substance of national parliamentary debates in the field of EU enlargement. Discourse-based analysis has featured prominently in the study of EU enlargement. Studies have focused on the discursive reasoning used to justify the accession of the ten CEE countries (Sjursen Citation2002, Citation2012), highlighting the ‘rhetorical entrapment’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2001) that led some initially sceptic member states to consent to their accession. Moreover, contested narratives such as the post-communist region’s ‘return to Europe’ (Bélanger Citation2014) or the EU as a ‘promotor of peace’ (Schumacher Citation2015) have been prominently discussed among scholars. Other studies explore debates on European identity and borders referring to the European Neighbourhood Policy (Christiansen, Petito, and Tonra Citation2000; Góra and Zielińska Citation2019) and analyse the European Commission’s discursive construction of Europeanisation processes in the EU’s neighbourhood (Jones and Clark Citation2008; Sekulić Citation2020). More recent articles have examined what motivates current discourses in the European Parliament on a privileged partnership for Turkey (Türkeş-Kılıç Citation2020), investigated the public-elite gap in discourses on enlargement in candidate countries (Kortenska, Steunenberg, and Sircar Citation2020) and explored the role of citizens’ discourses as constraints and opportunities for future enlargements (Dimitrova and Kortenska Citation2017). In substantive terms, previous studies have focused on identity-related arguments (Terzi Citation2021) or highlighted the growing relevance of security concerns in enlargement discourses (Góra Citation2021).

Our study concentrates on disentangling political discourses voiced in enlargement debates relating to the Western Balkans, which are currently the most promising candidates for EU accession. At the same time, several Western Balkan countries have experienced episodes of democratic backsliding in recent years, some of which are still ongoing (Crowther Citation2017; Bieber Citation2018, Citation2020; Richter and Wunsch Citation2020). Political discourses on enlargement towards this set of countries therefore promise to provide wide-ranging insights into the main priorities and concerns voiced at member state level towards the prospect of further EU widening. Although Turkey equally represents an interesting case, its size and Muslim background set it apart from the Western Balkans region, resulting in a stronger scepticism among member states that has translated into the search for alternatives to enlargement (Sjursen Citation2012; Türkeş-Kılıç Citation2020).

Framing EU enlargement as a political project

Our study adopts a discourse-oriented perspective to explore enlargement-related debates as a window into the wider process of European integration. Proponents of discourse analysis contend that discourses create meaning over social and physical phenomena and eventually determine political decisions (Hajer and Versteeg Citation2005). In the context of European integration, Diez has suggested that ‘the power of discourse is that it structures our conceptualizations of European governance’ (Diez Citation1999, 605). By framing support for or opposition to a further widening of the EU in a certain way, political actors partake in the construction of a specific understanding of EU enlargement in the wider context of European integration. It is these underlying frames or ‘patterns of justification’ (Hoeglinger, Wüest, and Helbling Citation2012) that we focus upon in our analysis.

To guide our empirical analysis, we build on previous efforts to distinguish different types of discourses on EU widening and relate these to distinct master frames, which we derive from the existing literature on EU enlargement. Up until the 2004 enlargement, the EU’s enlargement discourse has been viewed as widely inclusive, with arguments mainly relying on stability, prosperity, and security (Christiansen, Jorgensen, and Wiener Citation1999) as well as ‘norms of belonging’ (Terzi Citation2021). More recently, a contrasting logic emphasizing the strategic dimension of enlargement as a way to ward off threats in the immediate neighbourhood has surfaced (Terzi Citation2021, 147). Schmidt (Citation2012, 174–8) has broadly distinguished normative discourses that understand the EU as a values-based community from pragmatic discourses that view enlargement as a means to guarantee stability. Sjursen similarly differentiates pragmatic approaches articulated around utility and rational calculations, ethical-political justifications that emphasize values, and moral approaches focused on universal principles (Sjursen Citation2002, 494–5).

Building on these insights, our own approach conceptualizes three possible types of political discourses related to enlargement. We qualify as normative discourses those relating to the external projection of EU values, most prominently in the form of democracy promotion. This type of framing underpinned much of the academic debate on the EU’s ‘big bang’ enlargement, with early evaluations ranging from an optimistic embrace of the EU as a ‘transformative power’ (Grabbe Citation2006) and the promise of ‘democratisation by integration’ (Dimitrova and Pridham Citation2004) to analyses highlighting how reluctant member states were shamed into accepting the eventual accession of the Central and Eastern European candidates once the issue shifted from one of rational bargaining towards norm-based arguments emphasizing the shared liberal values of member states and accession candidates (Schimmelfennig Citation2001).

We contrast such approaches with pragmatic discourses that emphasize compliance and stabilisation. These issues have come to the fore as enlargement has extended to countries with lower economic and especially democratic standards than those prevalent among member states, resulting in increasingly formalised conditionality and an emphasis on strict monitoring of domestic reforms by the EU (Sedelmeier Citation2008; Levitz and Pop-Eleches Citation2010; Gateva Citation2015). In contrast to normative discourses, which highlight democratisation as a positive outcome of the EU accession process, pragmatic discourses treat democratisation as secondary to concerns about protecting the EU against political risks such as destabilisation or declining democratic quality stemming from the enlargement region. Specifically, scholars have voiced scepticism over the continued effectiveness of the EU’s approach beyond the CEE setting, with problems ranging from ‘fake compliance’ (Noutcheva Citation2009) and an insufficient normative appeal of EU conditionality (Freyburg and Richter Citation2010) to the lack of effective incentives for democratic change (Börzel and Schimmelfennig Citation2017). In parallel, growing concerns over democratic backsliding and illiberal trends among new entrants have overshadowed the earlier positive evaluations of post-accession compliance (Greskovits Citation2015; Kelemen Citation2017; Sedelmeier Citation2014). Recent findings from the Western Balkans region point to similar authoritarian trends among current candidate countries (Bieber Citation2018, Citation2020) and highlight the gradual decoupling of levels of formal compliance with membership requirements from effective democratic quality (Richter and Wunsch Citation2020).

Finally, we explore institutional discourses that focus inwardly on the enlarged EU’s institutional efficiency. Institutional discourses are grounded in a binary understanding of widening vs. deepening, whereby enlargement can prevent or threaten the EU’s internal consolidation (Cameron Citation2004; Kelemen, Menon, and Slapin Citation2014; Toshkov Citation2017). Despite overall positive findings on the compliance record of new member states (Toshkov Citation2008; Dimitrova Citation2010; Sedelmeier Citation2012) and their administrative integration into EU structures (Toshkov Citation2017), the wake of the CEE accession brought mounting concerns over the EU’s ‘integration capacity’ (Börzel, Dimitrova, and Schimmelfennig Citation2017; Börzel and Schimmelfennig Citation2017) and an emerging ‘enlargement fatigue’ (O’Brennan Citation2014).

Research design and data

We leverage an original dataset of hand-coded statements from national parliamentary debates on EU enlargement to conduct our empirical analysis. Given our objective to distil broad discursive trends, we selected four EU member states that vary regarding their historical ties with the EU, their parliamentary models, and their prevalent views on enlargement. France and Germany are two founding member states and important decision-makers in EU politics. France historically tends to favour a deepening of European integration among a smaller circle of countries, resulting in a growing hesitancy towards admitting further members (Wunsch Citation2017). The French Assemblée nationale is viewed as a comparatively weak parliament, in contrast to the institutional strength of the German Bundestag (Sprungk Citation2013). In substantive terms, Germany was initially a strong advocate of the Eastern enlargement, but has seen growing scepticism towards further widening among both its population and its political elites (Töglhofer and Adebahr Citation2017). Hungary and Poland, in turn, represent two new member states with own recent experience in accession negotiations. Hungary has adopted a broadly supportive view of further enlargement that contrasts with its more Eurosceptic stances in other policy areas (Huszka Citation2017). The correspondence of a strong parliamentary majority for the governing Fidesz party throughout much of our period of investigation and its formally moderate powers lead us to expect the Hungarian Országgyűlés to adopt a discourse that mirrors government policy. Finally, Poland is considered a strong supporter of enlargement and particular in favour of deepening the EU’s relations with its Eastern neighbours (Szymański Citation2007; Góra and Styczyńska Citation2015). The Polish Sejm holds moderate scrutiny powers, but has been shown in practice to be less active in European affairs even than formally weaker parliaments such as the French one (Borońska-Hryniewiecka Citation2021).

By exploring the underlying themes that characterize parliamentary debates on enlargement in four different member states, we propose to revisit and substantiate some of the previous insights into these countries’ positioning in the debate on EU widening. Besides, the joint examination of old and new member states is a valuable contribution per se, as most discourse-oriented studies of European integration privilege comparisons between older member states (Hutter, Braun, and Kerscher Citation2016; Koopmans and Statham Citation2010). Our analytical focus thus lies on establishing the dominant discursive patterns at the national level, rather than on teasing out possible ideological divergences in discourse based on party affiliation as highlighted by previous studies (Olszewska Citation2021; Bélanger and Wunsch Citation2022).

For the selection of debates, we searched the four parliaments’ online archives and identified all plenary protocols with any reference to enlargement-related topics. In a second step, we used political claim-making analysis (PCA) (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999) to capture individual statements defining an actor’s position about a (potential) candidate’s EU accession.Footnote4 We included all claims relating to actual EU membership and candidacy as well as Stabilisation and Association Agreements. Unlike machine learning techniques, our dataset results from a comprehensive coding process based on a detailed qualitative assessment of the plenary protocols, with each parliamentary debate examined and hand-coded by trained country experts. The benchmark for a statement to be included in the dataset was relatively high, since it had to contain both a position and at least one argument justifying the speaker’s stance on EU enlargement. Accordingly, this coding scheme does not capture every single mention of the Western Balkans in the four national parliaments, but focuses instead on actual substantive arguments on EU enlargement. As a result, the statements contained in the dataset allow us to understand how enlargement is discussed, rather than to survey the mere frequency with which it is mentioned. Our dataset captures 353 statements on the political dimension of enlargement from 120 plenary protocols (see for overview).

Our empirical mapping of different enlargement discourses relies on qualitative frame analysis. By scrutinizing how actors use political frames to justify their views on further widening, we analyse their particular understanding of enlargement and the construction of European integration in a broader sense. We aggregate the keywords coded to each statement in our dataset to one or more of the master frames presented in the theoretical section. As described above, the frame typology is set up deductively in relation to the established literature on European integration and EU enlargement to avoid subjectivity in the frame identification. provides an overview of the keywords corresponding to the previously identified master frames.

Table 1. Frames at aggregate level.

Taking the Eastern enlargement round as a starting point, our empirical analysis encompasses the period from 2004 to 2017. This timeframe broadly corresponds to the EU’s engagement with the Western Balkans since the formal awarding of a membership perspective for the region at the Thessaloniki Summit in June 2003. Although Croatia successfully concluded its accession negotiations and joined the EU as a member state in 2013, overall progress towards EU accession has been sluggish throughout most of the Western Balkans. The remaining countries of the region are either waiting to be recognized as official accession candidates (Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo), to see talks opened (Albania and North Macedonia), or making only very timid progress in the negotiations (Serbia and Montenegro). Besides the slow pace of domestic reforms and growing concerns about democratic backsliding, the limited advancement of the enlargement process in the Western Balkans is also due to a strengthened conditionality that has raised the benchmark for the countries from the region in comparison to previous accession candidates. Taking these broad context factors into account, our empirical section maps political discourses on enlargement in our selected national parliaments since the historical Eastern enlargement.

Mapping political enlargement discourses

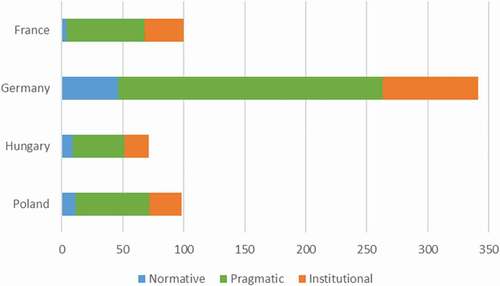

Our study seeks to identify and unpack divergent political discourses on EU enlargement since the ‘big bang’ accession of 2004. We begin by assessing broad discursive trends across our dataset, before delving more in-depth into the qualitative distinctions within each of the discursive categories we identified. Observing the distribution of different types of discourses across our four country cases (see ), two findings stand out: first, we note a clear dominance of pragmatic discourses in all four countries included in our study. These account for over 60% of statements analysed, while institutional discourses amount to around a quarter to a third of all statements. Discourses based on normative arguments, in turn, remain marginal in all settings. Second, there is an important discrepancy in the absolute number of statements coded for each of our national parliaments (see Table A1). Whereas the numbers are comparable for France, Hungary, and Poland, our dataset contains more than three times as many statements made in the German Bundestag. Two interpretations may explain this unequal distribution: on the one hand, the German Bundestag formally holds the greatest scrutiny powers of the four included parliaments, which can be expected to translate into a higher level of overall activity when it comes to debating EU-related issues. In Hungary and Poland, national parliaments were still growing into their new role in the post-accession period, which may lead to a lower level of involvement despite reasonably well-developed formal powers (Borońska-Hryniewiecka Citation2021). On the other hand, enlargement has been particularly salient in Germany both among elites and in public opinion (Töglhofer and Adebahr Citation2017), in contrast to a lower perceived relevance in France (Wunsch Citation2017), likely translating into a different degree of intensity of parliamentary debate.

The similarity in relative salience of different discourse types across four otherwise rather different member states points to a shared concern regarding further enlargement that characterizes national parliamentary discourses in the post-2004 period. We interpret the common emphasis upon compliance and conditionality along with institutional concerns to reflect a broader shift towards internal consolidation that has characterized the EU’s activity during the recent period of constitutional crisis in the lead-up to the Lisbon Treaty and the ensuing decade of polycrisis. Whereas the Eastern enlargement was couched in a grand narrative of ‘European reunification,’ the Western Balkan accession lacks such a unifying theme.

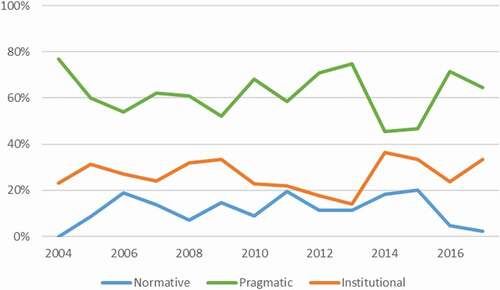

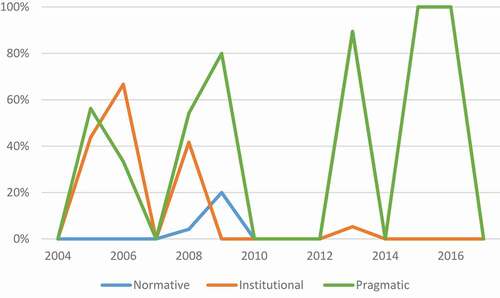

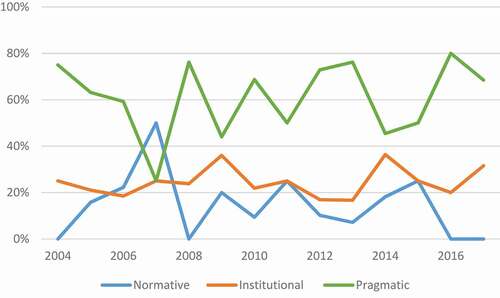

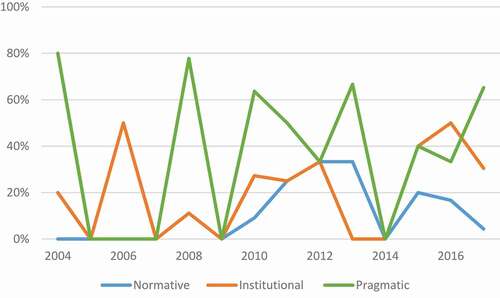

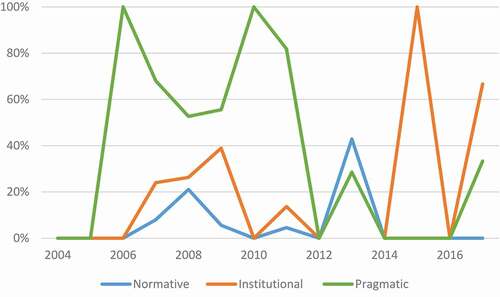

Regarding temporal variation, we observe a brief downturn of pragmatic statements and a corresponding uptick in institutional concerns in the immediate wake of the Croatian accession (). Normative concerns remain marginal throughout the period, but are entirely absent in 2004 and drop to near insignificance again at the end of the observed period. Overall, however, we note a striking stability in discursive patterns at the aggregate level, with no notable temporal trends in the relative salience of different types of discourse. Changes over time in individual national parliaments (see appendix Figure A1-A4) are more plausibly explained by the structure of our dataset, with certain years containing few or even no statements for a given category, than by any systematic variation at the national level. This limited cross-country and temporal variation leads us to devote the remainder of our empirical discussion to unpacking the specific discourses that underpin our broader categories, leveraging the qualitative depth of our dataset to illustrate recurrent themes in parliamentary debates and highlight country-specific differences regarding the prevalent motifs underpinning our three broad types of enlargement discourses.

Normative discourses

Normative discourses relate to value-based justifications for further enlargement or refer to the moral obligation to live up to previous commitments made to the Western Balkan region. They focus outwardly on the significance of enlargement for the target countries and on the broader symbolic importance of pursuing EU accession.

We identify a discourse on enlargement as ‘soft power’ that corresponds most closely to the classical ‘transformative power’ optimism in the lead-up to the Eastern enlargement. It is most prominent in Poland, underlining the country’s unusually strong pro-enlargement stance. Completing enlargement towards the Western Balkans, in this view, is ‘the best signal that the European Union is able to modernize the region of its immediate neighbourhood, and thus actually play a role, also in international politics’ (Poland, Krzysztof Szczerski, 2007).Footnote5 Still, even in Poland we find growing scepticism regarding the EU’s ability to successfully democratise its neighbourhood:

The European Union has today lost the ability to take responsibility for its neighbourhood, be it through the instruments of the neighbourhood policy or through an instrument that has so far been highly praised, including within the Union itself, namely the enlargement policy. (Poland, Konrad Szymański, 2017)

A second type of normative discourse focuses on enlargement as moral obligation, with the EU under a ‘political and moral obligation to help’ ensure the successful completion of enlargement (France, Jean-Pierre Dufau, 2008). This view characterizes the French discourse centred on the longue durée, with claims that ‘Europe has a historic mission towards this region’ (France, Dominique de Villepin, 2005) but can also be found in Polish and Hungarian parliamentary debates. In the post-communist context, the Western Balkans accession is qualified as ‘natural for historical reasons’ (Poland, Mateusz Piskorski, 2007), resulting in a ‘historical […] responsibility [to] take a proactive, supportive role in breaking down the obstacles to the accession of the Western Balkan countries’ (Hungary, Ferenc Gyurcsány, 2006).

Pragmatic discourses

Pragmatic discourses view enlargement as a tool to achieve a specific purpose. The framing of enlargement as a stabilisation tool soberly stresses the role of enlargement as a ‘catalyst for reforms in the countries of Southeast Europe’ (Germany, Michael Georg Link, 2013) and reassures the EU’s efforts to ‘move as much as possible towards stability and democracy in the region’ (Hungary, Kinga Göncz, 2008). This type of discourse focuses more instrumentally on enhancing the rule of law and democratic quality as a way to limit the risks the region may otherwise pose to the EU, articulating an expectation that democratic consolidation will ‘contribute to the political, economic and institutional stabilisation of the Balkan region’ (Hungary, Imre Vejkey, 2017).

A distinct of pragmatic discourse emphasizes strict conditionality as a cornerstone of membership negotiations with the Western Balkans. The focus here lies on the candidate countries’ ability to live up to the formal accession requirements, with statements frequently referring to the experience of the ‘big bang’ enlargement to caution against lowering the bar for current aspiring member states. This type of discourse appears across all four case studies, with a less prominent emphasis in Poland. Parliamentarians insist that the Eastern accession was a one-time experiment and that ‘we must not make another big bang, but must assess each country according to its own progress’ (Germany, Thomas Silberhorn, 2012). Others emphasize the need for ‘very strict conditions’ (Hungary, Zsolt Németh, 2010), ‘rigour’ and a ‘process of constant evaluation’ (France, Bernard Cazeneuve, 2013) of the accession criteria. Moreover, MPs reiterate that enlargement must remain an ‘open process’ (Germany, Oliver Luksic, 2009) and there ‘should not be any kind of automatism’ (Germany, Peter Beyer, 2009) when deciding over the admission of future EU entrants. Instead, candidate countries must ‘meet the appropriate criteria, tailored to their specific situation’ (Poland, Karol Karski, 2009).

Finally, a distinct pragmatic discourse focuses not on what enlargement can bring to candidate countries, but views enlargement as a tool to promote national interests. This discourse is specific to the Hungarian context, where parliamentary debates stress the need to ensure comprehensive minority rights protection for ethnic Hungarians, especially in Serbia. Statements highlight that ‘the expansion of the rights of the Hungarian community is possible now and not after the accession to the EU’ (Hungary, Szávay István, 2017). Improving democratic standards throughout the accession process thus becomes transactional, with one MP claiming that ‘it is in our national interest in particular to strengthen democratic rights and human and minority rights in the country, as the situation of our minority relatives there will also improve’ (Hungary, Dorosz Dávid, 2010).

Institutional discourses

Institutional discourses focus on the internal consequences of any future enlargement and insist upon the need to protect the EU’s achievements from any threats that may result from an expansion of its membership. We find such discourses concentrating on the EU’s internal consolidation to be of greatest concern to France and Germany. A discourse on institutional efficiency stresses the risk that further enlargement may undermine the functioning of EU institutions. A German MP, incidentally of Croatian origin, qualified the EU’s institutional capacity as ‘decisive’ (Germany, Josip Juratovic, 2011) alongside the established Copenhagen criteria that shape enlargement-related decisions. Echoing this sentiment, a French MP insisted that ‘the pace of enlargement will in any case take into account the ability of the European Union to integrate new member states, the Union having to maintain and deepen its own development’ (France, Alain Joyandet, 2008).

As a variant of the discourse on institutional efficiency, a discourse centred on the need for internal consolidation prior to any further enlargement round pits deepening and widening more explicitly against one another, with enlargement framed as a direct threat to the EU’s achievements to date. In the wake of the CEE accession, a French MP cautioned against giving the impression of any ‘flight forward on the question of enlargement,’ recommending instead to reflect ‘on the articulation of the enlargement process with the demands of a deepening of the European construction’ (France, Philippe Douste-Blazy, 2005).

Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis of post-2004 enlargement discourses in the national parliaments of four member states highlights the prominence of compliance-related concerns and institutional efficiency that have largely eclipsed more positive political frames relating to democracy promotion or the EU’s transformative power. Mirroring the growing hostility among European citizens towards the admission of further member states, our data confirm that parliamentarians across a range of different national contexts appear to share growing concerns over the impact of any further enlargement. It is striking that pragmatic discourses on enlargement to prevail across the board, irrespective of the more positive views on the admission of further countries that tend to prevail in recent entrants Hungary and Poland.

The salience of discourses on conditionality and integration capacity points to a growing juxtaposition of widening and deepening: from a focus on the external projection of values and practices leading up to the ‘big bang’ accession, post-2004 enlargement discourses have shifted towards greater introspection that prioritizes institutional efficiency and full compliance with membership requirements. Whereas earlier enlargements eventually became intertwined with institutional reform and an expansion of sectoral cooperation, resulting in a parallel process of widening and deepening, this no longer seems to be the case. Instead, widening is increasingly viewed as an alternative to deepening and therefore meets growing opposition by those member

states eager to ensure a closer cooperation among current member states.

In sum, debates on EU enlargement have shifted from tentative optimism about the EU’s transformative potential towards a growing wariness of the Union’s ability to bring lasting change to its neighbours in recent years. Mounting concerns about democratic quality and rule of law violations are central to this shift and have led to a tightening of conditionality towards the remaining candidate countries. With national parliaments wielding an effective veto power in decisions on future accessions, the reticence we note in national parliamentary debates implies stark political consequences: it is likely that the ‘big bang’ Eastern enlargement as a grouped accession of an entire region will remain an exception in the history of European integration.

Beyond their immediate relevance for the enlargement process, these findings signal a wider transformation the EU’s engagement with third countries, with optimism over the EU’s ability to project its values and practices beyond its borders giving way to a more pragmatic approach. Following the completion of the Eastern enlargement in 2004/2007, the focus has moved towards introspection and restoring the EU’s ability to maintain consensus and solidarity in challenging times. Ultimately, our analysis of enlargement discourses points to a changed understanding of the EU’s role in the world, with the preservation of its unique model of integration taking precedent over the desire to export values and practices beyond its borders.

Authors’ note

Both authors have contributed equally to the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Frank Schimmelfennig, Marie-Eve Bélanger, Marc S. Jacob, Agnieszka Ciancara, Mila Mikalayev as well as two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The Western Balkans hold a formal membership perspective and encompass (potential) candidate countries Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Republic of North Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia. We exclude Turkey from our discussion given that its quality as a very large and Muslim candidate country has triggered greater reluctance towards its admission in many member states that would risk dominating observed discursive patterns.

2. The total number of EU member states has dropped back to 27 following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal on 31 January 2020.

3. In addition to Malta and Cyprus that also joined the EU in 2004.

4. Further information on the coding process including tests on inter-coder reliability is available online: [reference to be added following review].

5. All direct quotations are authors’ translations of the original statements coded in our dataset.

References

- Auel, K., and T. Raunio. 2014. “Debating the State of the Union? Comparing Parliamentary Debates on EU Issues in Finland, France, Germany and the United Kingdom.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 20 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1080/13572334.2013.871482.

- Auel, K., and T. Christiansen. 2015. “After Lisbon: National Parliaments in the European Union.” West European Politics 38 (2): 261–281. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.990693.

- Auel, K., O. Rozenberg, and A. Tacea. 2015. “To Scrutinise or Not to Scrutinise? Explaining Variation in EU-Related Activities in National Parliaments.” West European Politics 38 (2): 282–304. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.990695.

- Auel, K., and C. Neuhold. 2017. “Multi-arena Players in the Making? Conceptualizing the Role of National Parliaments since the Lisbon Treaty.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (10): 1547–1561. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1228694.

- Bélanger, M.-E. 2014. “Europeanization as a Foundation of the European Construction.” In Europeanization and European Integration, edited by R. Coman, T. Kostera, and L. Tomini, 29–49. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bélanger, M.-E., and F. Schimmelfennig. 2021. “Politicization and Rebordering in EU Enlargement: Membership Discourses in European Parliaments.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (3): 407–426. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1881584.

- Bélanger, M.-È., and N. Wunsch. 2022. “From Cohesion to Contagion? Populist Radical Right Contestation of EU Enlargement.” Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (3): 653–672. doi:10.1111/jcms.13280.

- Best, E. 2010. The Institutions of the Enlarged European Union: Continuity and Change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bieber, F. 2018. “Patterns of Competitive Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans.” East European Politics 34 (3): 337–354. doi:10.1080/21599165.2018.1490272.

- Bieber, F. 2020. The Rise of Authoritarianism in the West Balkans. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Borońska-Hryniewiecka, K. 2021. “National Parliaments as ‘multi-arena Players’ in the European Union? Insights into Poland and France.” Journal of European Integration 43 (6): 701–716. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1800672.

- Börzel, T.A., and F. Schimmelfennig. 2017. “Coming Together or Drifting Apart? The EU’s Political Integration Capacity in Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 278–296. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1265574.

- Börzel, T.A., A. Dimitrova, and F. Schimmelfennig. 2017. “European Union Enlargement and Integration Capacity: Concepts, Findings, and Policy Implications.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 157–176. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1265576.

- Braun, D., S. Hutter, and A. Kerscher. 2016. “What Type of Europe? The Salience of Polity and Policy Issues in European Parliament Elections.” European Union Politics 17 (4): 570–592. doi:10.1177/1465116516660387.

- Cameron, F. 2004. “Widening and Deepening.” In The Future of Europe: Integration and Enlargement, edited by F. Cameron. London, New York: Routledge, 1–17 .

- Christiansen, T., K.E. Jorgensen, and A. Wiener. 1999. “The Social Construction of Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 6 (4): 528–544. doi:10.1080/135017699343450.

- Christiansen, T., F. Petito, and B. Tonra. 2000. “Fuzzy Politics Around Fuzzy Borders: The European Union’s `Near Abroad’.” Cooperation and Conflict 35 (4): 389–415. doi:10.1177/00108360021962183.

- Crowther, W. 2017. “Ethnic Condominium and Illiberalism in Macedonia.” East European Politics and Societies 31 (4): 739–761. doi:10.1177/0888325417716515.

- Diez, T. 1999. “Speaking ‘Europe’: The Politics of Integration Discourse.” Journal of European Public Policy 6 (4): 598–613. doi:10.1080/135017699343496.

- Dimitrova, A., and G. Pridham. 2004. “International Actors and Democracy Promotion in Central and Eastern Europe: The Integration Model and Its Limits.” Democratization 11 (5): 91–112. doi:10.1080/13510340412331304606.

- Dimitrova, A.L. 2010. “The New Member States of the EU in the Aftermath of Enlargement; Do New European Rules Remain Empty Shells?” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (1): 137–148. doi:10.1080/13501760903464929.

- Dimitrova, A., and E. Kortenska. 2017. “What Do Citizens Want? and Why Does It Matter? Discourses among Citizens as Opportunities and Constraints for EU Enlargement.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 259–277. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1264082.

- Freyburg, T., and S. Richter. 2010. “National Identity Matters: The Limited Impact of EU Political Conditionality in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (2): 263–281. doi:10.1080/13501760903561450.

- Fuchs, D., and H.-D. Klingemann. 2002. “Eastward Enlargement of the European Union and the Identity of Europe.” West European Politics 25 (2): 19–54. doi:10.1080/713869598.

- Gábor, J. 2006. “Exporting or Pulling Down?” European Journal of Social Quality 6 (1): 82–108.

- Gateva, E. 2015. European Union Enlargement Conditionality. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Góra, M., and N. Styczyńska. 2015. “The EU Enlargement Policy in the Polish Political Discourse after 2004.” In The European Union – A New Start?, ed. Second International Conference of the European Studies Department, Sofia, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”.

- Góra, M., and K. Zielińska. 2019. “Competing Visions: Discursive Articulations of Polish and European Identity after the Eastern Enlargement of the EU.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (2): 331–356. doi:10.1177/0888325418791021.

- Góra, M. 2021. “It’s Security Stupid! Politicisation of the EU’s Relations with Its Neighbours.” European Security 30 (3): 439–463. doi:10.1080/09662839.2021.1957841.

- Grabbe, H. 2006. The EU’s Transformative Power: Europeanization through Conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greskovits, B. 2015. “The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe.” Global Policy 6 (S1): 28–37. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12225.

- Hajer, M., and W. Versteeg. 2005. “A Decade of Discourse Analysis of Environmental Politics: Achievements, Challenges, Perspectives.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 7 (3): 175–184. doi:10.1080/15239080500339646.

- Hertz, R., and D. Leuffen. 2011. “Too Big to Run? Analysing the Impact of Enlargement on the Speed of EU decision-making.” European Union Politics 12 (2): 193–215. doi:10.1177/1465116511399162.

- Hillion, C. 2010. The Creeping Nationalisation of the EU Enlargement Policy. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies (SIEPS).

- Hoeglinger, D., B. Wüest, and M. Helbling Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2012. “Culture versus economy: The framing of public debates over issues related to globalization“. Political Conflict in Western Europe, 229–253.

- Huszka, B. 2017. “Eurosceptic yet pro-enlargement: The Paradoxes of Hungary’s EU Policy.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17 (4): 591–609. doi:10.1080/14683857.2017.1367462.

- Hutter, S., D. Braun, and A. Kerscher. 2016. Constitutive Issues as Driving Forces of Politicisation. Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, A., and J. Clark. 2008. “Europeanisation and Discourse Building: The European Commission.” European Narratives and European Neighbourhood Policy. Geopolitics 13 (3): 545–571.

- Kandogan, Y. 2000. “Political Economy of Eastern Enlargement of the European Union: Budgetary Costs and Reforms in Voting Rules.” European Journal of Political Economy 16 (4): 685–705. doi:10.1016/S0176-2680(00)00021-5.

- Kelemen, R.D., A. Menon, and J. Slapin. 2014. “The European Union: Wider and Deeper?” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (5): 643–646. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.899115.

- Kelemen, R.D. 2017. “Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union.” Government and Opposition 52 (2): 211–238. doi:10.1017/gov.2016.41.

- Ker-Lindsay, J., I. Armakolas, R. Balfour, and C. Stratulat. 2017. “The National Politics of EU Enlargement in the Western Balkans.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17 (4): 511–522. doi:10.1080/14683857.2017.1424398.

- Kinski, L. 2020. “What Role for National Parliaments in EU Governance? A View by Members of Parliament.” Journal of European Integration 43 (6): 717–738. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1817000.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 1999. “Political Claims Analysis: Integrating Protest Event and Political Discourse Approaches.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 4 (2): 203–221. doi:10.17813/maiq.4.2.d7593370607l6756.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 2010. The Making of a European Public Sphere: Media Discourse and Political Contention. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kortenska, E., B. Steunenberg, and I. Sircar. 2020. “Public-elite Gap on European Integration: The Missing Link between Discourses among Citizens and Elites in Serbia.” Journal of European Integration 42 (6): 873–888. doi:10.1080/07036337.2019.1688317.

- Kvist, J. 2004. “Does EU Enlargement Start a Race to the Bottom? Strategic Interaction among EU Member States in Social Policy.” Journal of European Social Policy 14 (3): 301–318. doi:10.1177/0958928704044625.

- Laitin, D. 2002. “Culture and National Identity: ‘The East’ and European Integration.” West European Politics 25 (2): 55–80. doi:10.1080/713869599.

- Levitz, P., and G. Pop-Eleches. 2010. “Monitoring, Money and Migrants: Countering Post-Accession Backsliding in Bulgaria and Romania.” Europe-Asia Studies 62 (3): 461–479. doi:10.1080/09668131003647838.

- Noutcheva, G. 2009. “Fake, Partial and Imposed Compliance: The Limits of the EU’s Normative Power in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (7): 1065–1084. doi:10.1080/13501760903226872.

- O’Brennan, J. 2014. “‘On the Slow Train to Nowhere?’ the European Union, ‘Enlargement Fatigue’ and the Western Balkans.” European Foreign Affairs Review 19 (2): 221–241. doi:10.54648/EERR2014011.

- Olszewska, N. 2021. “Eurosceptic, but Still in Favour of Enlargement: EU Accession Discourses in Hungary and Poland along Cultural Differentiation.” Paper presented at the IPSA Conference on 12 July 2021, virtual conference.

- Richter, S., and N. Wunsch. 2020. “Money, Power, Glory: The Linkages between EU Conditionality and State Capture in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (1): 41–62. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1578815.

- Sadurski, W. 2004. “Accession’s Democracy Dividend: The Impact of the EU Enlargement upon Democracy in the New Member States of Central and Eastern Europe.” European Law Journal 10 (4): 371–401. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2004.00222.x.

- Schimmelfennig, F. 2001. “The Community Trap: Liberal Norms, Rhetorical Action, and the Eastern Enlargement of the European Union.” International Organization 55 (1): 47–80. doi:10.1162/002081801551414.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and U. Sedelmeier. 2004. “Governance by Conditionality: EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (4): 661–679. doi:10.1080/1350176042000248089.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and U. Sedelmeier, eds. 2005. The Politics of European Union Enlargement: Theoretical Approaches. Oxon: Routledge.

- Schmidt, V.A. 2012. “European Member State Elites’ Diverging Visions of the European Union: Diverging Differently since the Economic Crisis and the Libyan Intervention?” Journal of European Integration 34 (2): 169–190. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.641090.

- Schumacher, T. 2015. “Uncertainty at the EU’s Borders: Narratives of EU External Relations in the Revised European Neighbourhood Policy Towards the Southern Borderlands.” European Security 24 (3): 381–401. doi:10.1080/09662839.2015.1028186.

- Sedelmeier, U. 2008. “After Conditionality: Post-accession Compliance with EU Law in East Central Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (6): 806–825. doi:10.1080/13501760802196549.

- Sedelmeier, U. 2012. “Is Europeanisation through Conditionality Sustainable? Lock-in of Institutional Change after EU Accession.” West European Politics 35 (1): 20–38. doi:10.1080/01402382.2012.631311.

- Sedelmeier, U. 2014. “Anchoring Democracy from Above? The European Union and Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Romania after Accession.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (1): 105–121. doi:10.1111/jcms.12082.

- Sekulić, T. 2020. The European Union and the Paradox of Enlargement the Complex Accession of the Western Balkans. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sjursen, H. 2002. “Why Expand?: The Question of Legitimacy and Justification in the EU’s Enlargement Policy.” Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (3): 491–513. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00366.

- Sjursen, H. 2012. “A Certain Sense of Europe?” European Societies 14 (4): 502–521. doi:10.1080/14616696.2012.724576.

- Sprungk, C. 2013. “A New Type of Representative Democracy? Reconsidering the Role of National Parliaments in the European Union.” Journal of European Integration 35 (5): 547–563. doi:10.1080/07036337.2013.799944.

- Szymański, A. 2007. “The Position of Polish Political Elites on Future EU Enlargement.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 23 (4): 548–560. doi:10.1080/13523270701674624.

- Terzi, Ö. 2021. “Norms of Belonging: Emotion Discourse as a Factor in Determining Future “Europeans”.” Global Affairs 7 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1080/23340460.2021.1927794.

- Töglhofer, T., and C. Adebahr. 2017. “Firm Supporter and Severe Critic – Germany’s two-pronged Approach to EU Enlargement in the Western Balkans.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17 (4): 523–539. doi:10.1080/14683857.2017.1397961.

- Toshkov, D. 2008. “Embracing European Law.” European Union Politics 9 (3): 379–402. doi:10.1177/1465116508093490.

- Toshkov, D. 2017. “The Impact of the Eastern Enlargement on the decision-making Capacity of the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 177–196. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1264081.

- Türkeş-Kılıç, S. 2020. “Justifying Privileged Partnership with Turkey: An Analysis of Debates in the European Parliament.” Turkish Studies 21 (1): 29–55. doi:10.1080/14683849.2019.1565941.

- Vachudova, M.A. 2005. Europe Undivided: Democracy, Leverage and Integration after Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Winzen, T. 2022. “The Institutional Position of National Parliaments in the European Union: Developments, Explanations, Effects.” Journal of European Public Policy. 29(6): 994–1008. 1–15 (online first).

- Wunsch, N. 2017. “Between Indifference and Hesitation: France and EU Enlargement Towards the Balkans.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 17 (4): 541–554. doi:10.1080/14683857.2017.1390831.

- Zhelyazkova, A., C. Kaya, and R. Schrama. 2017. “Notified and Substantive Compliance with EU Law in Enlarged Europe: Evidence from Four Policy Areas.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (2): 216–238. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1264084.

Appendix

Table A1. Number of political statements on enlargement by country, 2004–2017.