ABSTRACT

As the politicization of European integration is channeled through the media, it fundamentally implies a discursive power distribution between actors and institutions based on who and what type of argument is promoted. Scholars have started to hypothesize who will benefit from this expansion of debates to wider publics, predominantly using media logics to conclude with the notion of ‘discursive intergovernmentalism’: where media spotlights enter, executives benefit. In this paper, we contribute to these nascent studies into the discursive empowerment of actors and institutions, by adding a critical notion. Taking our cue from Critical Discourse Analysis, we argue that media output should not only be theorized based on news values, but equally by accounting for existing institutional power (im)balances. To evaluate this argument, we draw on new intergovernmentalist theory, and empirically delve into the Spanish and Dutch media coverage of the (run-up to the) July 2020 NextGenerationEU recovery package.

1. Introduction

The politicization of European integration is arguably one of the most crucial developments constituting the future development of the European Union. Whether it concerns effects on the democratic credentials of the EU (De Wilde and Lord Citation2016), the efficiency of EU decision-making (Bressanelli, Koop, and Reh Citation2020), or the future level and nature of European integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Citation2015), this ‘increase in polarization of opinions, interests or values and the extent to which they are publicly advanced towards the process of policy formulation within the EU’ (De Wilde Citation2011, 566) is assumed to have fundamental consequences. In essence, politicization refers to the expansion of the scope of conflict surrounding EU integration in the mass-mediated public sphere (Gheyle, Citation2019; Oleart, Citation2021; Haapala and Oleart Citation2022). As Statham and Trenz (Citation2013, 3) argue, politicization ‘requires the expansion of debates from closed elite-dominated policy arenas to wider publics, and here the mass media plays an important role by placing the contesting political actors in front of a public’.

Hence, whether politicization leads to enhanced democratic legitimacy, to a deepening of European integration, or to their opposite outcomes, to a large extent depends on who exactly is discursively empowered by politicization and which arguments prevail. Given the (national) media’s role as an interface between political elites and the general public, the media is not only a platform through which political conflicts are translated (presented by journalists who contribute to framing ‘Europe’ in the public sphere), yet also a power-distributing tool. Media coverage is not neutral: it empowers some actors, institutions, and arguments over others, thereby contributing to some solutions over others (Börzel and Risse Citation2019; Schuette Citation2019). Some see an agonistic public sphere that discursively empowers a plural group of actors, including non-executive ones (such as civil society organisations or diverse political parties), as vital for generating communicative power that can keep in check the administrative power of executive actors (Conrad and Oleart Citation2020).

In this context, scholars have attempted to hypothesize who will be discursively empowered through politicization, and what kinds of arguments prevail. The most recent attempt hereof is presented by De Wilde (Citation2019), who concludes with the notion of ‘discursive intergovernmentalism’. Confronting media logics or ‘news values’ with the mechanisms of the grand theories of EU integration, De Wilde hypothesizes that media coverage alters the balance of power between key actors and institutions, by ‘strengthening the hand of member state governments over other actors, and continuously reconstruct[ing] the image that the EU is primarily an intergovernmental organization, with the European Council as the most important political body’ (De Wilde Citation2019, 1203). He therefore states that we should connect the study of changing institutional power balances with a look at how mass media represent actors and arguments, and how this in turn affects those institutional power struggles.

Our aim in this paper is to contribute to these analyses of discursive empowerment, by adding a critical outlook on media power, and particularly on who and what we expect to see during politicized episodes. Our starting point, inspired by Critical Discourse Analysis (Van Dijk, 2021; Wodak and Meyer Citation2001), is that the media does not only shape and strengthen power (im)balances between EU institutions, but are crucially also shaped by it. Rather than the media empowering certain actors and arguments in a one-way fashion, we argue that there is a feedback loop between actually-existing institutional power balances, and how they are reflected and represented in the media. Hence, stating expectations about who and what will be reflected in media output, and the intricate relationships between them, is not sufficiently comprehensible by looking at media logics alone, but should be complemented with an analysis of actually-existing political and power balances.

Translating this to the EU context, however, is not straightforward, as questions of power (im)balances are complex and changing over time. On paper, power is dispersed over various institutions, without one being able to dominate another. What is more, depending on the area or the nature of a problem to be solved by common European response, different actors and institutions come to the fore. In particular in the post-Maastricht era, observations have been made about two types of Europe (Van Middelaar Citation2017): one ‘supranational’ Union with a predominant focus on economic and internal market affairs, steered mainly by the European Commission, the Council of the EU, and the European Parliament. And an ‘intergovernmental union’ (Fabbrini Citation2016) when it comes to areas of core state powers, such as foreign affairs or macro-economic governance. Here, the Member States retain a firm grip through unanimity, and with the European Council in the driving seat (Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Citation2015).

In order to evaluate our argument that media output and discursive empowerment will reflect actually-existing power (im)balances at EU level, we zoom in on a particular politicized episode, namely the European recovery response to the COVID-19 crisis. The features of this episode, widely perceived as a crisis, and thematically on the nexus of macro-economic governance and health policy, make it a prime subject for analysis through a new intergovernmentalist framework (Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Citation2015) . By tracking the discussion around the European Recovery package in the Spanish and Dutch mainstream media, and by performing a qualitative content and discourse analysis of one quality newspaper per country (El Pais and De Volkskrant), we analyze who is given a voice and from what perspective, and whether this discursively reflects the politics and power (im)balances as theorized by the new intergovernmentalist literature.

2. Theorizing discursive empowerment

2.1. The limits of media logics

Studying media representation of EU debates is not of a recent nature, and overlaps largely with the study of the Europeanization of domestic public spheres (Koopmans and Statham Citation2010). Yet the aim of these studies was mostly empirical: study who inhabits the public sphere to see if some processes of Europeanization are ongoing, attached to normative considerations on the EU’s democratic deficit. The study by Koopmans (Citation2007) is exemplary in this respect: he acknowledges that EU integration affects the relative opportunities for different actors, but thought it as an empirical question who exactly would be empowered. He argued this will correlate with the authority of the EU in the area in question, and with different types of media logics across countries. Eventually, his large-scale study found that the ‘only actors that are systematically overrepresented in all types of Europeanization [of public spheres] are government and executive actors’ (Koopmans Citation2007, 199). The same reasoning applies to studies on the politicization of EU integration, which have initially been concerned with measuring degrees and levels of salience, actor expansion, and polarization, rather than theorizing who will be empowered (Hutter et al. Citation2016).

Against this background, the study by De Wilde (Citation2019) marks a new step, in that it not only acknowledges that only some actors and arguments will be empowered, but that we should be able to theorize which ones. His contribution looks at what happens when we link insights on media logics and news values (such as status, valence, relevance, identification, cfr. O’Neill and Harcup Citation2019) to the mechanisms of the three ‘grand theories’ – neofunctionalism, liberal intergovernmentalism, and postfunctionalism. This confrontation leads to a variety of expectations. From a neofunctionalist perspective, for example, the hypothesis is that supranational executives will benefit most from media attention, while debates would be framed more frequently in citizen/public terms, with more references to democracy. From the perspective of intergovernmentalist theory, national executives (mostly in the European Council) would benefit, implicitly strengthening a narrative about what ‘our’ national interest is. In postfunctionalist reasoning, media is hypothesized to strengthen the question which identity conflicts are represented, while opening up room to circumvent rather than constrain dissensus.

Yet there are some lingering issues in De Wilde’s analysis. First, in his conclusion, these varied outcomes are merged into one overarching outcome of ‘discursive intergovernmentalism’, stating that ‘media coverage favors member state governments, reconstructing European politics decidedly toward a form of discursive intergovernmentalism’ (De Wilde Citation2019, 1208). Yet exactly why the balance swings to intergovernmentalism is not explicated. Indeed, there is an admission further on that media coverage also creates opportunities for EU actors, introducing the term of ‘new supranational entrepreneurship’. In doing so, there arguably is a reconstruction of the classic neofunctionalist-intergovernmentalist debate, now updated with media logics incorporated, but without a definitive argument on which theory applies when. Concretely, this leaves open questions, such as: if there is an executive strengthening, of which executives? National leaders? The President of the EU Council? Supranational executives? And how do inter-institutional and inter-state relationships look like?

This undergirds a more fundamental point: the limit of relying on media logics or news values to hypothesize what and who will be covered in mass media, is that it assumes that journalists and media are quasi-independent from overarching power relationships. Taking our cue from Critical Discourse Analysis, we want to add a critical notion, stressing that media output not only shapes power, but is also shaped by it. The media is part of a broader field of power relationships, not immune to it. Taking such a perspective should therefore allow us to state expectations about media output by looking at actually-existing power (im)balances, instead of focusing on journalistic objectives. To evaluate this argument in an EU context, we need to highlight a particular analytical framework on EU power balances, and a fitting case. For the former, we turn to new intergovernmentalist thinking.

2.2. New intergovernmentalism: integration without supranationalization

Arguably the most important shift in the balance of power in post-Maastricht European Union politics is the strengthening and growing involvement of the European Council and other intergovernmental fora. Theorized in frameworks such as ‘deliberative intergovernmentalism’ (Puetter Citation2012), ‘new intergovernmentalism’ (Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter Citation2015) or ‘intergovernmental union’ (Fabbrini Citation2016), these contributions share the key argument that core intergovernmental forums of EU governance (mainly the European Council, but also Euro Summits, the Eurogroup and specialized Council constellations such as ECOFIN and Foreign Affairs Council) have become the main catalysts of policy integration in new areas of EU activity since Maastricht: economic governance, foreign and security policy, justice and home affairs, and social and employment matters – all areas close to ‘core state powers’ (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2016). Crucially, integration in these areas did not occur through supranationalization (with competence transfers to independent supranational actors), but outside the community framework and strictly controlled by national leaders and ministers.

While this perspective on changing power balances in the EU has been set in motion post-Maastricht, it has received additional clout and urgency in the post-Lisbon era. First, the 2009 Lisbon Treaty for the first time recognized the European Council as a formal and independent institution of the European Union (with its own President and Secretariat), which is viewed by some as the codification of informal practices already ongoing (Fabbrini and Puetter Citation2016). Secondly, the series of politicized crises that plagued the EU since 2008 constituted ‘event politics’ instead of more traditional ‘rule-based politics’ (Van Middelaar Citation2017), which required a leadership and urgency that seemingly only national governments could bring. Crucially, these crises are not seen as causes of these power shifts, but as the context in which pressure builds to such an extent that the underlying dynamics come to the fore.

In this changed landscape, it is hence first and foremost the European Council that has been lifted to the position of EU political executive where power and authority resides. It no longer only gives long-term impetus, but is involved in all aspects of EU decision-making. Obviously, such a changing role has repercussions for other institutions. The epicenter of decision-making has moved towards a relationship between the European Council (and Euro Summits) and specialized Council formations like ECOFIN (or the Euro Group) or the Foreign Affairs Council. The latter now hold more informal meetings, scheduled alongside European Council meetings. In this intergovernmental system, there is hardly any influential role for the European Parliament, and neither did national parliamentary control receive upgrades (Fabbrini Citation2016).

The inter-institutional relationship that has received most attention is that of the changing role of the European Commission (EC) in this development. While some have argued that the Commission is, as a result of the increasing power of the European Council, in decline (Majone Citation2014), most scholars rather identify a changing relationship. For example, Bocquillon and Dobbels (Citation2014) find that the post-Lisbon balance of power can best be described with the term ‘competitive cooperation’. Even though the European Council seems to be in a hierarchically superior position, both institutions depend on and are highly influenced by each other. The European Council has indeed become a ‘power center’ but is ‘not connected to the grid’, so it needs to cooperate with the European Commission. Nugent and Rhinard (Citation2016) argue along the same lines that a Commission decline is overstated. It has never had a fully free hand in agenda-setting, with cross-influences for legislative proposals a permanent feature. Post-Lisbon, the EC has adapted to the increasing role of the European Council quite well, seeking out complementary roles rather than conflictual ones, focusing on where it can support the European Council in its deliberations and searches for solutions (Fabbrini Citation2016). Thaler (Citation2016) finds confirmation hereof in the field of energy policy: instead of seeking influence through procedural rights, it seeks close inter-institutional coordination with the European Council. All of this backs up the observation made by Van Middelaar (Citation2017), who admits that the role of the Commission changed, but remains crucially important as future initiative taker, contributing with expertise to the European Council, formulating options as solutions, and hence still having a big hand in eventual outcomes.

Finally, the politics of this intergovernmental union also takes on particular shape. In this new intergovernmentalist constellation, the focus on policy coordination necessarily implies deliberation, and searching for unanimity. However, in these areas of high salience, and especially when pressure builds for solutions to be found – in times of crisis – patterns of hierarchy and domination appear. Fabbrini (Citation2016) shows in the case of the Euro crisis that unbridgeable differences were resolved through the unilateral leadership of a group of Member States (Germany and France). Yet others, like Puetter (Citation2016) do not see this phenomenon as an attack on the norm of consensus that so characterizes the new intergovernmentalist EU. In other words, conflict is bound to ensue, followed by patterns of domination, yet the end result (for now) remains an institutional framework where policy coordination is based on consensus-oriented decision-making.

3. Methodology and data set

Our theoretical and empirical point of departure is that questions about the power-distributing role of media discourse can be better studied by taking the perspective of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). Far from being a ‘natural’ form of representation of the political world, CDA scholars (Van Dijk Citation2001; Fairclough Citation2000; Wodak and Meyer Citation2001) view discourse as a social practice. Following Fairclough (Citation1995, 54–55) this means that language and discourse is ‘socially shaped, but is also socially shaping – or socially constitutive.’ Thus, a CDA perspective looks at discourse as not only shaping power relations but also reflecting them. CDA pushes towards the study of discourse in order to ‘analyze hidden, opaque, and visible structures of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in language’ (Wodak and Meyer Citation2001, 10). The ‘critical’ aspect hence means to make explicit what often remains latent, to show that particular representations reflect a power project, and could have been different. It also focuses on what is missing, on which elements are prioritized and which are backgrounded.

To evaluate the argument that institutional power balances will constitute the discursive representation in the mass media, we choose a case that typifies new intergovernmentalist thinking, namely the European recovery response to the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. After five months of highly visible political conflicts, government leaders agreed to a European recovery package called NextGeneration EU in July 2020. This was interpreted by some commentators as a ‘Hamiltonian’ moment for the EU, as the crisis was acknowledged as a European one that required a beyond the nation-state policy approach illustrated by the mutualisation of debt (Sandbu Citation2020), thereby ‘crossing the rubicon’ for EU integration.

For several reasons, this episode seems best analysed from a new intergovernmentalist perspective. First, it is a strongly politicized crisis, that required urgency and leadership to solve common problems in areas where no script is available. In the past, it was indeed national leaders, and the European Council, in particular, that were seen as the only actors possible to provide legitimacy to such a search (Van Middelaar Citation2017). Secondly, the policy area is on the intersection of economic governance (which is commonly associated as part of the ‘intergovernmental union’) and health policy, which is largely a domestic competence of high salience. Both undergird the observation that common solutions have to be found in areas where EU Member States are reluctant to transfer competences to the supranational level, and hence where the politics of intergovernmental union should prevail.

To further our aims from a CDA perspective, we perform the analysis in three steps. A first step implies uncovering the general discursive aspects of our dataset. To do so, we coded two elements. First, the images accompanying the media articles, coding which type of actor is being portrayed, such as Member State representatives, supranational actors, or civil society actors. We presume that this visualization is a good indication for who is represented as the key political actors in the discussion. Secondly, we inductively coded the general discursive theme of the articles based on the title and lead paragraph of the article (which we see as setting the scene for the article itself, and for the reader). This is not a framing analysis, but a straightforward coding of the main theme of the article. For example, when the lead mentions that two countries are fighting over recovery money, and that the European Commission is presenting a compromise offer, we code this as ‘intergovernmental conflict’ and ‘supranational solutions’.

In a second step of the analysis, we look deeper into aspects of the discourse that may reveal the power relations between actors as presented. We do this, first, by looking at the role allocation of actors: when the different actors (as coded in the visual representation) are given standing, how are they presented? What role are they given in the bigger scheme of things and how are they portrayed? Secondly, we also look at the main locus of politics: either explicitly or implicitly, where is the key centre of decision-making presented to be? In a third and final step, we look at the dominant conflict framing, looking at which arguments are well-represented, and how this grants a discursive advantage to some actors over others. In all three of these subsections, we also devote particular attention to what is excluded from sight because of the focus on the particular findings.

We perform this analysis on quality mainstream media articles, as these are central to the way in which ‘Europe’ is talked about and framed (Diez Medrano Citation2003) in the national public spheres, and they are a central space that sets the acceptable range of discourses. As it is our aim to test whether media representation reflects institutional power balances, the most important selection criterion of country cases is that the conflict was highly visible domestically. We therefore chose Spain and the Netherlands, because its governments were among the most prominent actors during the European Council, broadly representing two contrasting perspectives about what the EU should do in response to Covid-19.

For each country, we chose a leading mainstream news outlet, El PAÍS and De Volkskrant, respectively, on the basis that they play a similar role in the public spheres of Spain and The Netherlands. While the selection of these news outlets does not represent the national public sphere, they are considered to be crucial ‘framers’ of European issues, having an influence on the coverage in other media spaces. In terms of timing and number of articles, we analyzed all the articles related to the European recovery talks between mid-March 2020 (when measures against Covid-19 started to take place) and the end of July 2020, which includes the run-up to the July European Council summit as well as its aftermath. 108 articles were found for El PAÍS, and 70 for De Volkskrant, all based on a keyword list revolving around ‘corona recovery fund’. Quotes of these articles below are translated by ourselves.

4. The European recovery package in the Spanish and Dutch mainstream media

4.1. Visual representation of actors and general discursive themes

The quantitative results of our content analysis indicate an overwhelming visual and discursive dominance of executive actors in the media coverage of EL PAÍS and De Volkskrant. This is illustrated by the visual representation and the general discursive themes.

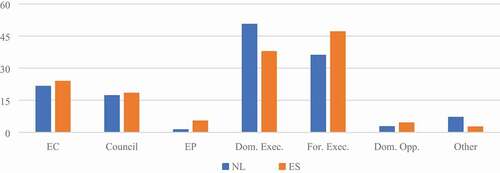

In terms of the visual representation of actors, shows the percentage of images where particular actor types are represented, which we take as an indication of who the main protagonists of the discussion according to the news outlets are.Footnote1 For example, in the Dutch media, domestic and foreign executives are present in, respectively, 50% and 36% of all images. What is also clear is the similarity in the coverage: both domestic and foreign government representatives are widely present in the visuals. Add to this the European Council as the umbrella of executive leaders, and the absence of actors from the European Parliament, or any type of domestic opposition, and we can confirm, on a general level, one aspect of the new intergovernmentalist framework, namely that intergovernmental actors are the leading actors. Media consumers hence receive the main idea that the European Union consists of government leaders having to find solutions together.

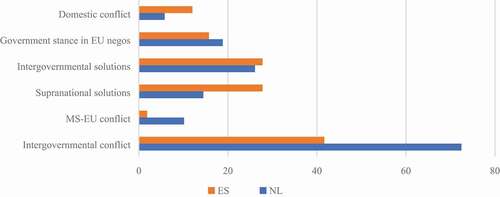

A second broad look at the dataset concerns the general discursive themes covered. This is a rough sketch of what the main topic of an article is all about – the perspective the journalist takes to enter into talks of the EU recovery fund. As shows, there is a predominant focus on the theme of ‘intergovernmental conflict’. In De Volkskrant more than 70% of articles, either in the title or the lead of the article, approaches the topic from the point of view of Member States being in conflict with each other over what to do. In El Pais this is less emphasized – with more emphasis on Member States looking for solutions as well – but the general picture remains the same: the view is one of the EU being dominated by intergovernmentalist actors who clash with each other, drawing the conflict lines around country lines.

This conclusion is strengthened by looking at other related themes: ‘MS-EU conflict’ refers to a country being in conflict or disagreement with ‘the EU level’ (mainly the EC or the European Council President); ‘intergovernmental solutions’ refers to government actors themselves finding or proposing solutions; and ‘government stance in EU negotiations’ implies a closer look at ‘the national position’ articulated by the domestic government. So, purely on the basis of this broad thematic coding, we can see that an intergovernmental logic is discursively strengthened, as Member States, their positions and clashes are the key angle of how to approach the recovery talks.

What is absent is as revealing as what is present. There is hardly any sign of the European Parliament, first of all, which again reflects new intergovernmentalist frameworks. While having a strong co-decisional role in supranational politics, it is almost completely absent in intergovernmentalist areas, not only in presence, but also in terms of accountability relationships (Crum Citation2018). Likewise, opposition actors from within Member States, or even from civil society organizations are near invisible. This relates to the finding that domestic conflict between parties (or between executive and non-governmental actors) or even transnational conflict along ideological lines is not how this recovery package is approached. Instead of, for example, social-democratic against liberal views on how to handle this recovery are aired, we see that country lines are conflict lines, again strengthening the idea that each country has a national interest and identity, which then clash on the European stage.

4.2. Role attribution and locus of politics

Following this dominant intergovernmental conflict theme, we dig deeper into the roles of some of the actors involved in it, and where their conflicts are mostly settled. The first observation is that of the Member States as defenders of the national interest, fighting in the European arena. Through particular word usages, the conflict is emphasized as a spectacular fight between Member States. In Dutch article titles, there was mention of a ‘Dutch middlefinger towards the South’ (Peeperkorn Citation2020a); Dutch executives holding a ‘rearguard fight’ against Southern Member States (Hofs Citation2020); an ordinary ‘bar fight’ about the European recovery package (Peeperkorn Citation2020b). This conflict is seemingly not frowned upon, as a Dutch journalist concludes a European Summit by saying that Rutte’s ‘haggling’ was not nice to see, but understandable (Peeperkorn Citation2020c). Most tellingly perhaps, a Dutch journalist claimed at that same occasion: ‘It was a magnificent battle in the European arena’ (Giesen Citation2020a). The Member States as gladiators fighting in the European Colosseum: the European Council.

Indeed, in this entire episode, the European Council is portrayed as the main locus of politics where decisions are being made, together with preparatory Eurogroup and ECOFIN meetings. In both country datasets, numerous referrals to ‘Brussels’, ‘Europe’ or the ‘EU’ in fact tend to refer to the European Council, equating the EU with intergovernmental logics. This is yet another sign that the terms of the debate were set by national governments, and that the primary ‘locus of EU politics’ remains predominantly the ‘EU Council’ or simply ‘Member States’.

Those institutions with a European mandate – which are largely invisible from this discussion – are seemingly also embroiled in this intergovernmental conflict. For instance, EL PAÍS reported on the exclusion from the recovery fund negotiations of the European Parliament and the European Central Bank (ECB) by German and Dutch Prime Ministers Merkel and Rutte because

several governments believe that the socialist David Sassoli [President of the EP] would try to tip the balance to benefit Southern countries. (… .) The choreography of the meetings reveals, however, the distrust of capitals such as Berlin or The Hague towards the institutions or organizations to which the defense of the common interest is attributed. Diplomatic sources say that during the March summit Merkel even tried to leave Lagarde [President of the ECB] out of the group of presidents, whose stance in favor of a massive European fiscal response is also aligned with the South (De Miguel Citation2020a).

Yet, not all national governments are given the same importance, given that some have a more expansive role. In line with new intergovernmentalist theory, patterns of domination occur with more powerful Member States ploughing the way forward, especially Germany and France, and blocs of countries pitted against each other, here a Northern alliance (personified by Dutch PM Mark Rutte) and a Southern alliance (personified by Italian PM Conte or Spanish PM Sanchez). Yet while domination is a key feature of politics in new intergovernmental theory, so is constant deliberation and the eventual resolution of conflict. The discursive themes of media coverage also fittingly alternate between conflict and solutions. And just as in conflict, in solutions, there are dominating relationships. In both newspapers, personal portraits of Merkel appear. In de Volkskrant, the German Chancellor is presented as ‘the safest pair of hands’ to handle this crisis (Peeperkorn Citation2020d). Similarly, in El País, Merkel is presented as the dealmaker between the Northern and Southern governments, exemplified by the following excerpt:

Merkel did not hide her impatience at the immobility of a self-described frugal bloc that refused to take a single step that would satisfy the rest of the partners. And she got to have some bitter squabbles, particularly with Frederiksen [Danish Prime Minister]. But she considered it over with once the blockade was discarded and all parties were able to enter into the essential bargaining to reach an agreement. The Chancellor later shared with the Danish Prime Minister some chocolate bonbons as a diplomatic nod of reconciliation and a sign that the altercations between the members of the European Council are like those of footballers: they are forgotten once off the field. (De Miguel Citation2020b)

The role of the European Commission deserves particular attention in new intergovernmentalist thinking. Looking at the images where Commission President Von der Leyen appears (about 10 times in the Dutch sample, 18 times in the Spanish sample), she is mostly portrayed either as accompanying European Council President Charles Michel (rubbing elbows or leading the line) or in between government leaders. Especially in this second type of image – in between Merkel, Macron, Rutte and Conte – the role of the Commission as mediator is stressed. Instead of (or in addition to) proclaiming the European common interest aspects of a future deal, she is often portrayed as a broker between the conflicting coalitions – seemingly replicating the role of Charles Michel. Beyond ‘competitive cooperation’, it looks more like a tandem, with the Commission operating with the same logic as the European Council. When reporting on what the Commission is set out to do, this assisting function also becomes clear, as she tries to bridge differences between Member States with her proposals, and framework agreements reached by the European Council should be further elaborated by the Commission, again in close cooperation with the Member States.

4.3. Conflict framing

In both the Spanish and Dutch media, there is a dominant conflict line: financial prudence versus solidarity. The Dutch government, together with Denmark, Austria, and Sweden were mostly stressing that receiving recovery money comes with certain obligations and conditionalities. They argued that countries that have shown financial prudence over the years should not give blank cheques to those who haven’t. Contrary to that are voices (with Southern governments in the lead) that the Dutch government (and others) should show solidarity to Member States who are hardest hit, without thinking too much about conditionalities, as this was an unforeseeable crisis.

This conflict hence tended to portray the Northern governments coalition as attempting to minimize the European recovery fund, as it is perceived as benefiting mainly Southern European countries, the most affected initially by the global pandemic. An example of this framing is present in the following excerpt:

“Disgusting”. The Portuguese Prime Minister, António Costa, chose that word without thinking to discredit the idea of the Dutch Minister of Finance, Wopke Hoekstra, suggesting that some countries were asking for money to face the pandemic because they were wasteful. The emphasis of the adjective used by Costa, which he even repeated, described the disgust of the South of Europe towards the attitude of The Hague, erected as the leader of the hawks, of abusing the tale of the ant and the grasshopper in order to prevent the creation of Eurobonds to face the greatest emergency that the continent has experienced since the Second World War. (Pellicer Citation2020a)

Again, it is interesting to look at the specific word usages involved: the coalition led by the Dutch government was branded as ‘the Frugal Four’, literally meaning ‘sparing or economical as regards money’. This Frugal Four was pitted against a Southern camp, that was hence portrayed as always spending (too much) money, and hence unworthy of receiving ‘Dutch’ money. At some point, de Volkskrant tried to tackle these myths, with one article heading ‘Are the Netherlands really the “cheapskate” of Europe?’ (Frijters and Van Uffelen Citation2020) and another running the numbers on the stereotypes on Northern and Southern countries (Bakker and Van der Ploeg Citation2020). Yet in doing so, they inadvertently reproduce the image that the conflict is a zero-sum game where Member States clash with each other, and that economic reasons are the only legitimate ones for integration.

What further strengthens the intergovernmental logic is the implicit focus on ‘one’ national interest. The Dutch government does not want to engage in any kind of blank cheque, because they have shown financial prudence, and don’t want to be responsible for ‘Italian’ or ‘Spanish’ debt through bad management. Even the solidarity argument is framed from this national interest lens: one country has to help another country in order to save itself. In a Dutch article, a French executive is quoted arguing that ‘it is not in the Dutch interest that the Italian state goes bankrupt’ (Giesen Citation2020b), showing that solidarity is again framed from the perspective of the national interest: work together, because it is good for your country and your economy. ECB President Christine Lagarde, was similarly quoted in EL PAÍS saying that ‘solidarity is a matter of self-interest’ (Pellicer Citation2020b).

Even the (few) articles in which the articles are narrated through a domestic conflict lens tend to be viewed along the intergovernmental ‘frugal vs south’ lens. For instance, EL PAÍS reports that ‘Sánchez asks PP [main Spanish opposition party] for “patriotism” to support the Government position in Europe’ (Cué Citation2020), and a headline from 26 June 2020 read ‘The Partido Popular joins the “frugal” club’ (Pérez Citation2020). Likewise, in De Volkskrant, the few articles focusing on domestic conflict are about D66, the Dutch government coalition partner, who wanted the government to show more solidarity to other countries (Brouwers Citation2020). In this way, the domestic and intergovernmental conflict perspectives are intertwined, to the point that domestic conflict is reproduced as a competition between opposition and government to better represent the ‘national interest’ in the intergovernmental struggle between the ‘frugal’ and the ‘Southern’ governments.

Finally, the emphasis on this conflict, and the implicitly strengthened view of national interests, crowds out other possible conflict lines. Only in exceptional occasions we see different angles. Pepe Álvarez, Secretary-General of the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), the second biggest Spanish trade union, fought the intergovernmental bargaining frame in order to introduce a transnational EU solidarity angle, arguing that ‘the European trade unions, without distinction between Northern and Southern countries, we had reached a unanimity without precedent (…) in which we demanded the increase of the own resources of the European Union and massive financing for investment backed through common debt’ (Álvarez Citation2020). Similarly, Commission representatives, such as current Vice-President Frans Timmermans, also operate as discursive entrepreneurs to reframe the recovery fund beyond intergovernmental bargaining. Timmermans emphasizes the relevance of the recovery fund for Europe, and relates it to ongoing policies, such as when Timmermans connects the recovery fund to the Green New Deal and argues the following: ‘Either we find together a collective solution at the European level to the coronavirus crisis or all countries will fail individually’ (De Miguel Citation2020c). However, while this discourse is present exceptionally, it remains marginal across the Spanish and Dutch media coverage of the recovery fund analyzed.

5. Conclusion: discursive intergovernmentalism at the expense of EU democracy?

If mass media output not only shapes, but is also shaped by existing power balances in the EU, then media coverage of the politics surrounding the European recovery package should show clear new intergovernmentalist features. Taking our cue from Critical Discourse Analysis, we hence performed a qualitative content and discourse analysis of the media coverage of Dutch and Spanish mainstream newspapers during the five months of corona recovery talks at European level. Analyzing the visual representation of actors, the discursive themes, the role allocation of actors, the locus of politics, and the dominant conflict framing, we broadly confirm the existence of new intergovernmentalist characteristics reflected in media output, and hence the existence of a ‘discursive intergovernmentalism’ in this area of EU politics.

Through a visual dominance, a thematic focus on intergovernmental bargaining, and a conflict framing in terms of zero-sum games and ‘solidarity in the national interest’, national executives are presented as the leading actors, the ‘gladiators’ deliberating, discussing, and entering into conflict about their (shared or different) national interests, in the main European arena: the European Council. The politics of new intergovernmentalism clearly come to the fore, through an alternation of deliberation (and consensus-seeking) and conflict, and dominating relationships in both modes of interaction. Beyond a ‘competitive cooperation’, the relationship between the European Commission and the European Council looked more like a tandem, with the Commission President taking up similar mediating roles than that of the Council President. Ultimately, what we saw in the NextGenEU negotiations, both in terms of its discursive coverage as well as the institutional dynamics around it, reflected more business as usual than a fundamental break with traditional EU policy-making (see also Miró Citation2021).

Crucially, we are not arguing that journalists are not seeing the ‘objective reality’ that there are more actors involved than those covered by them, and that it is their ’subjective’ coverage that provides national executives with the discursive power. What we empirically establish here is the discursive reflection of power relations in the EU, which are further solidified here as a strengthening of national executives in EU policy and decision-making. In this way, there is a dialectical interaction between the way in which EU politics is covered by the media (and the ‘national interest’ media logics) and the intergovernmental institutional dynamics, in which they shape and reinforce each other. The more intergovernmental discourse, the easier it is for national leaders to legitimise increasingly intergovernmental institutional dynamics.

From a normative democratic perspective, these findings also bear further consideration. The reflection of existing institutional power balances in this case further cements and solidifies the Union as only a Union of Member States, where intergovernmental conflict reigns supreme. This is, as we have shown in our analysis, to the detriment of perspectives from the domestic opposition, the European Parliament, or any type of non-governmental actor. Of course, given the dual chains of accountability in the EU (a Member State route, and a direct European route via the EP) we would not, from a normative perspective, demand that discussions are only framed in European terms, and as transnational conflict (Kinski and Crum Citation2020). Member State interests will always play a role in a Union of states. Yet it is more a question of prioritization and balance, which we argue here is skewed and biased towards one side: the intergovernmentalist one. Transnational coalition-making is complicated, because media coverage situates the idea of the ‘national interest’ at the center of the discussion, strengthening the position of the respective governments vis-à-vis those actors that may contest them.

In general, the impact of politicization on EU democracy is therefore qualified. We see a process of Europeanization of the Spanish and Dutch mainstream media, as both news outlets broadly converge around the way in which the EU recovery package is discussed, yet there is very little European-we-ness. Europeanization is combined with a framing that pits member states against each other or against the EU, rather than witnessing domestic or transnational conflict (De Wilde and Lord Citation2016). Normatively speaking, it is good news that EU politics becomes increasingly intertwined with national politics. However, if the way in which politicization takes place is exclusively empowering and even legitimising further intergovernmentalism, it ought to be nuanced. To correct this bias, our approach suggests that instead of demanding from journalists that they cover all possible views, an institutional fix in the form of, for example, increasing the weight of European and national parliaments vis-à-vis the European Council and the European Commission.

Acknowledgement

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their pointed and very helpful comments. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Political Science Workshops of the Low Countries (3-4 June 2021), and the UACES Annual Conference 2021 (6-8 September 2021). We thank the participants for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. As labels for actor categories, we use the institution represented. For example, when Merkel and Macron are visualized individually, they are labelled as representing their own country (domestic and foreign executives). When they are visualized together with other leaders in the European Council, it is coded as ‘Council’.

References

- Álvarez, P. 2020. “Europa responde.” EL PAÍS, July 24. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-07-24/europa-responde.html

- Bakker, M., and J. Van der Ploeg. 2020. “Wat Klopt Er van de Vooroordelen over Noord- En Zuid-Europa?.” De Volkskrant, June 19. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/wat-klopt-er-van-de-vooroordelen-over-noord-en-zuid-europa~be759a28/

- Bickerton, C. J., D. Hodson, and U. Puetter. 2015. “The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post‐Maastricht Era.” Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (4): 703–722. doi:10.1111/jcms.12212.

- Bocquillon, P., and M. Dobbels. 2014. “An Elephant on the 13th Floor of the Berlaymont? European Council and Commission Relations in Legislative Agenda Setting.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (1): 20–38. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.834548.

- Börzel, T. A., and T. Risse. 2019. “Grand Theories of Integration and the Challenges of Comparative Regionalism.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (8): 1231–1252. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1622589.

- Bressanelli, E., C. Koop, and C. Reh. 2020. “EU Actors under Pressure: Politicisation and Depoliticisation as Strategic Responses.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (3): 329–341. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1713193.

- Brouwers, A. 2020. “Jetten Zet het Europadebat in Nederland op Scherp.” De Volkskrant. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/jetten-zet-het-europadebat-in-nederland-op-scherp~b92b3dc6/

- Conrad, M., and A. Oleart. 2020. “Framing TTIP in the Wake of the Greenpeace Leaks: Agonistic and Deliberative Perspectives on Frame Resonance and Communicative Power.” Journal of European Integration 42 (4): 527–545. doi:10.1080/07036337.2019.1658754.

- Crum, B. 2018. “Parliamentary Accountability in Multilevel Governance: What Role for Parliaments in post-crisis EU Economic Governance?” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (2): 268–286. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1363270.

- Cué, C. 2020. “Sánchez pide al PP “patriotismo” para apoyar la posición del Gobierno en Europa.” EL PAÍS, June 14. https://elpais.com/espana/politica/2020-06-14/sanchez-pide-unidad-y-patriotismo-para-reconstruir-el-pais-tras-la-pandemia.html

- De Miguel, B. 2020a. “Merkel y Rutte dejan al Parlamento Europeo fuera de la gestión de la crisis del coronavirus.” EL PAÍS, April 6. https://elpais.com/internacional/2020-04-06/merkel-y-rutte-dejan-al-parlamento-europeo-fuera-de-la-gestion-de-la-crisis-del-coronavirus.html

- De Miguel, B. 2020b. “La crisis que hizo cambiar a Merkel.” EL PAÍS, July 7. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-07-21/la-crisis-que-hizo-cambiar-a-merkel.html

- De Miguel, B. 2020c. “Timmermans: “La propuesta de España contra la crisis puede ser la base para el acuerdo europeo”.” EL PAÍS, July 7. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-04-20/timmermans-la-propuesta-de-espana-contra-la-crisis-puede-ser-la-base-para-el-acuerdo-europeo.html

- De Wilde, P. 2011. “No Polity for Old Politics? a Framework for Analyzing the Politicization of European Integration.” Journal of European Integration 33 (5): 559–575.

- De Wilde, P., and C. Lord. 2016. “Assessing actually-existing Trajectories of EU Politicisation.” West European Politics 39 (1): 145–163. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1081508.

- De Wilde, P. 2019. “Media Logic and Grand Theories of European Integration.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (8): 1193–1212. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1622590.

- Diez Medrano, J. 2003. Framing Europe: Attitudes to European Integration in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fabbrini, S. 2016. “From Consensus to Domination: The Intergovernmental Union in a Crisis Situation.” Journal of European Integration 38 (5): 587–599. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1178256.

- Fabbrini, S., and U. Puetter. 2016. “Integration without Supranationalisation: Studying the Lead Roles of the European Council and the Council in post-Lisbon EU Politics.” Journal of European Integration 38 (5): 481–495. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1178254.

- Fairclough, N. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Essex: Longman.

- Fairclough, N. 2000. New Labour, New Language? London: Psychology Press.

- Frijters, S., and X. Van Uffelen 2020. “Is Nederland Echt de Vrek van Europa?.” De Volkskrant, April 10. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/is-nederland-echt-de-vrek-van-europa~bc31d9e8/

- Genschel, P., and M. Jachtenfuchs. 2016. “More Integration, Less Federation: The European Integration of Core State Powers.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (1): 42–59. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782.

- Gheyle, N. 2019. “Trade policy with the lights on: The origins, dynamics, and consequences of the politicization of TTIP.” Doctoral dissertation, Ghent University.

- Giesen, P. 2020a. “Het Was Een Schitterend Gevecht In de Europese Arena.” De Volkskrant, July 24 . https://www.volkskrant.nl/columns-opinie/het-was-een-schitterend-gevecht-in-de-europese-arena~b18ea0aa/

- Giesen, P. 2020b. “Franse Minister van Financiën: ‘Het Is Niet in Jullie Belang Dat Italië Wegzinkt in Een Enorme Depressie’.” De Volkskrant, April 19. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/franse-minister-van-financien-het-is-niet-in-jullie-belang-dat-italie-wegzinkt-in-een-enorme-depressie~bd0d8aeb/

- Haapala, T., and Á. Oleart. 2022. Tracing the Politicisation of the EU. London: Palgrave.

- Hofs, Y. 2020. “Rutte En Hoekstra Voeren Achterhoedegevecht Tegen Transferunie.” De Volkskrant, March 27. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/rutte-en-hoekstra-voeren-achterhoedegevecht-tegen-transferunie~baba7c03/

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- S. Hutter, E. Grande, and H. Kriesi, edited by. 2016. Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316422991.

- Kinski, L., and B. Crum. 2020. “Transnational Representation in EU National Parliaments: Concept, Case Study, Research Agenda.” Political Studies 68 (2): 370–388. doi:10.1177/0032321719848565.

- Koopmans, R. 2007. “Who Inhabits the European Public Sphere? Winners and Losers, Supporters and Opponents in Europeanised Political Debates.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (2): 183–210. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00691.x.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham, Eds. 2010. The Making of a European Public Sphere: Media Discourse and Political Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Majone, G. 2014. Rethinking the Union of Europe Post-Crisis. Has Integration Gone Too Far? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Miró, J. 2021. “Debating Fiscal Solidarity in the EU: Interests, Values and Identities in the Legitimation of the Next Generation EU Plan.” Journal of European Integration 44 3 307–325.

- Nugent, N., and M. Rhinard. 2016. “Is the European Commission Really in Decline?” Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (5): 1199–1215. doi:10.1111/jcms.12358.

- O’Neill, D., and T. Harcup. 2019. “News Values and News Selection.” In ‘The Handbook of Journalism Studies’, edited by K Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch. New York: Routledge 213–228 .

- Oleart, A. 2021. Framing TTIP in the European Public Spheres: Towards an Empowering Dissensus for EU Integration. London: Palgrave.

- Peeperkorn, M. 2020a. “Hoekstra Stribbelt Tegen bij Steunpakket EU: ‘Een Nederlandse Middelvinger Naar het Zuiden’.” De Volkskrant, March 24. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/hoekstra-stribbelt-tegen-bij-steunpakket-eu-een-nederlandse-middelvinger-naar-het-zuiden~b94cd15b/

- Peeperkorn, M. 2020b. “‘Kroegruzie’ over Europees Hulppakket Tegen Coronacrisis Slaat Diepe Wonden.” De Volkskrant, April 10. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/kroegruzie-over-europees-hulppakket-tegen-coronacrisis-slaat-diepe-wonden~b8c91c7b/

- Peeperkorn, M. 2020c. “Het Gesteggel van Rutte in Europa Was Niet Mooi, Maar Wel te Begrijpen.” De Volkskrant, July 21. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/het-gesteggel-van-rutte-in-europa-was-niet-mooi-maar-wel-te-begrijpen~b2c964ac/

- Peeperkorn, M. 2020d. “Europees Herstelfonds Na Corona Is Zelfs voor Merkel Een Flinke Klus.” De Volkskrant, July 1. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/europees-herstelfonds-na-corona-is-zelfs-voor-crisisleider-merkel-een-flinke-klus~b2415ce3/

- Pellicer, L. 2020a. “Rutte, el más duro de los ‘halcones’.” EL PAÍS, March 29. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-03-28/rutte-el-mas-duro-de-los-halcones.html

- Pellicer, L. 2020b. “La UE acuerda desbloquear las ayudas de medio billón de euros contra la crisis del coronavirus.” EL PAÍS, April 10. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-04-09/la-ue-acuerda-desbloquear-las-ayudas-de-medio-billon-de-euros-contra-la-crisis-del-coronavirus.html

- Pérez, C. 2020. “Los populares se apuntan al club de los ‘frugales’.” EL PAÍS, June 26. https://elpais.com/espana/2020-06-25/los-populares-se-apuntan-al-club-de-los-frugales.html

- Puetter, U. 2012. “Europe’s Deliberative Intergovernmentalism: The Role of the Council and European Council in EU Economic Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.609743.

- Puetter, U. 2016. “The Centrality of Consensus and Deliberation in Contemporary EU Politics and the New Intergovernmentalism.” Journal of European Integration 38 (5): 601–615.

- Sandbu, M. 2020, “EU Crosses the Rubicon with Its Emergency Recovery Fund.” Financial Times, 22 July 2020. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/bd570dde-3095-4074-bd37-18003f2bd3c2 (accessed 30 July 2020)

- Schuette, L. A. 2019. “Comparing the Politicisation of EU Integration during the Euro and Schengen Crises.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15 (4): 380–400. doi:10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1036.

- Statham, P., and H. J. Trenz. 2013. The Politicization of Europe. Contesting the Constitution. London: Routledge.

- Thaler, P. 2016. “The European Commission and the European Council: Coordinated Agenda Setting in European Energy Policy.” Journal of European Integration 38 (5): 571–585. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1178252.

- Van Dijk, T. 2001. “Multidisciplinary CDA: A Plea for Diversity.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by R. Wodak and M. Meyer. London: Sage.

- Van Middelaar, L. 2017. De Nieuwe Politiek van Europa. Groningen: Historische Uitgeverij.

- Wodak, R., and M. Meyer, eds. 2001. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.