ABSTRACT

Although there are various legal tools to make European integration more flexible, the EU and its member states uphold long-term arrangements of de facto differentiation circumventing EU law. This article assesses their role in the EU’s system of differentiated integration. To that end, it advances a model based on rational choice theory, outlining the steps and conditions under which tolerated arrangements of de facto differentiation can emerge. This is illustrated in three case studies in Economic and Monetary Union (EMU): (1) Sweden’s de facto opt-out from EMU; (2) Kosovo’s adoption of the euro as sole legal tender, and (3) the Fiscal Compact. Data was gathered via document analysis and 11 expert interviews. The article concludes that de facto differentiation may constitute a viable alternative and useful means to make EU integration more flexible if strong national demand for differentiation meets the need for discretion or timely, pragmatic action.

Introduction

European integration is more differentiated than meets the eye. It is well known that the European Union (EU) allows or mandates member states to opt out of EU policy if preferences or administrative capacities diverge and encourages third states to opt in to facilitate trade or future accession (Leuffen, Rittberger, and Schimmelfennig Citation2022; Gänzle, Leruth, and Trondal Citation2020; Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020). Differentiation is usually established via a legal mechanism that follows certain rules and procedures. But the EU also harbours differentiation arrangements that are untouched by EU law, such as Sweden’s informal opt-out from Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) or the original Schengen Agreement. The literature refers to differentiation created by circumventing EU law as de facto differentiation (Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2019; Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020; Hofelich Citation2022).

While the EU is known for sometimes strategically turning a blind eye to temporary breaches of its own rules (Kleine Citation2013), engaging in long-term arrangements that circumvent and arguably undermine EU law appears dubious. For one, the EU, and in particular its supranational institutions, should be expected to oppose any circumvention of the law they created and are tasked to protect. Moreover, it is unclear why states choose de facto differentiation in the first place. It lacks the legal security provided by other means to deviate from EU policy and can be challenged by the EU (Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2019). Finally, the EU has become known as a system of differentiated integration in which legal opt-outs/ins are a viable option (Leuffen, Rittberger, and Schimmelfennig Citation2022). What, then, is the purpose of de facto differentiation considering the existence of legal alternatives to accommodate states’ divergent preferences in the EU?

To address this question, this article advances a rationalist model explaining the emergence of such arrangements and explores the expectations generated by this model in three case studies in EMU. It concludes that despite the apparent downsides, de facto differentiation may bring unique benefits to both the differentiation-seeking state(s) and the EU. It provides additional flexibility, is less visible, and allows for timely and unbureaucratic solutions. Thus, de facto differentiation fulfils a distinct purpose as a pragmatic alternative to the legal solutions available in the EU – although it raises normative concerns.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section briefly summarises the literature and outlines both concept and typology of de facto differentiation based on (1) non-compliance; (2) unilateral opt-ins; and (3) integration outside EU law. The subsequent section advances a model inspired by rational choice theory, which describes the steps and conditions under which de facto differentiation can become an arrangement tolerated by the EU. The final section presents the results of three case studies covering each type of de facto differentiation in EMU: (1) Sweden’s de facto opt-out from EMU; (2) Kosovo’s adoption of the euro, and (3) the Fiscal Compact as an international treaty outside EU law.

Literature, concept, and typology of de facto differentiation

De facto differentiation builds on Schimmelfennig and Winzen’s (Citation2020) concept of differentiation as an unequal increase or reduction in the centralisation level, policy scope, or membership of the EU. Here, differentiation is used as an umbrella term for differentiated integration and differentiated disintegration. The distinction between de jure and de facto differentiation lies in whether the respective opt-outs or other derogations are enshrined in EU law or not (ibid: 16).

In the literature, de facto differentiation has received some mention but mostly in passing. Beginning with Andersen and Sitter’s (Citation2006) closely related concept of deviant integration, the circumvention of EU law or non-compliance have been conceived as alternative ways to achieve differentiation. Holzinger and Schimmelfennig (Citation2012) acknowledge that member states may choose non-compliance over negotiating differentiation to avoid costly policy obligations while meeting the same ends. Howarth (Citation2010) finds evidence for this in EU industrial policy, for example in deliberate breaches of the EU’s limit of state aid. The most prominent example is Sweden’s de facto opt-out from the final stage of EMU (Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2019). More recently, de facto differentiation has also been put in context with Poland and Hungary’s ongoing violations of the EU’s rule of law principles (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2019).

Eriksen’s interpretation of de facto differentiation is slightly different (Eriksen Citation2019), as it refers to informal groupings distinguishable by different levels of integration. For example, he mentions the Eurogroup, an informal body of the EU Council comprising the eurozone finance ministers. Since the financial crisis hit Europe, Eriksen contends that non-Eurogroup states have been ‘downgraded to a secondary status,’ thus establishing de facto differentiation (ibid: 77). This assessment is grounded in the measures taken by eurozone countries outside the EU legal framework such as the Fiscal Compact which exacerbated differentiation in EMU.

The hitherto scant literature understands de facto differentiation as a form of circumventing EU rules or laws, be it via non-compliance, undermining decision-making structures, or deepening integration outside EU law. In an attempt to consolidate the literature, Hofelich (Citation2022) has developed an encompassing typology. On that basis, de facto differentiation can be defined as a deliberate and enduring circumvention of the EU legal framework, which leads to an unequal increase or reduction of the centralisation level, policy scope, or membership of the EU.

Type 1: deliberate and enduring non-compliance

Sczepanski and Börzel (Citation2021) recently found likeness in the intent behind non-compliance and differentiation as both serve to accommodate the heterogeneity of preferences, power, or capacity. It is, however, important to note that there are two significant differences. First, non-compliance is usually more temporary.Footnote1 Second, while non-compliance can be due to either a lack of capacity or divergent preferences (Tallberg Citation2002), if it lasts long enough to be considered differentiation, it is almost always a matter of preferences. Rationalists assert that this is because states weigh the costs of compliance (e.g. interest group preferences) against the costs of non-compliance (e.g. sanctions) and will remain non-compliant until the balance tilts in favour of the latter (cf. Downs, Rocke, and Barsoom Citation1996). Because states witnessing only capacity issues face far fewer compliance costs, they shift resources to ensure compliance in time before being hit with non-compliance costs (Börzel, Hofmann, and Panke Citation2012).

Thus, only the wilful protraction of non-compliance can be considered a type of de facto differentiation. If this is then tolerated by the EU, the practical outcome mimics that of de jure differentiation in that EU law applies unequally across member states. For example, Sweden’s opt-out from EMU in non-compliance with the Treaties affects businesses and citizens no differently than Denmark’s legal opt-out. The same applies to the EU’s toleration of Slovakia’s non-compliance with secondary law concerning pharmaceutical exports (Zhang Citation2021).

Type 2: unilateral opt-ins

The second type of de facto differentiation is related to external horizontal differentiation which describes the partial adoption of the acquis by non-member states (Leuffen, Rittberger, and Schimmelfennig Citation2022). Most research in that area deals with opt-ins that are induced by the EU, either as part of requirements for non-EU members of the European Economic Area (EEA) or policy alignment targets of EU neighbourhood policy (cf. Lavenex Citation2015).

In contrast to such de jure opt-ins mandated by bilateral agreements, de facto opt-ins are understudied (but see Cianciara and Szymanski Citation2020). These are unilateral steps taken without explicit approval or any legal basis provided by the EU. In most cases, they take the benign shape of adopting standards or norms to facilitate trade or future accession to the EU. But there is also potential for free-riding by accessing collective goods designed to be restricted to member states. If unilateral opt-ins directly affect the territorial scope of an EU policy, they can be considered de facto differentiation. This applies to Kosovo and Montenegro’s unilateral adoption of the euro, which expands the eurozone although only in usage, not governance of the common currency.

Type 3: integration outside EU law

To escape legislative deadlock, EU integration occasionally proceeds in the form of intergovernmental treaties rather than expanding EU law. Of course, EU member states regularly conclude international treaties among each other and with third parties. But for this to equate de facto differentiation, the centralisation level, policy scope or membership of the EU must be affected. This is most prominently reflected in the 1985 Schengen Agreement and, more recently, in the Fiscal Compact which expands not only the EU’s fiscal policy provisions but also the Commission and ECJ’s oversight.

De facto differentiation as a rational choice

What is the purpose of de facto differentiation, considering that there are legal alternatives for the EU to accommodate states’ divergent preferences? To address this question, this article advances a theoretical model based on rational choice theory (c.f., Snidal Citation2002; Pollack Citation2006). Rationalism is the ontological basis of most theories used to explain differentiation, including neofunctionalism, liberal intergovernmentalism, or rational institutionalism. The grand theories of European integration and their derivative mid-range theories, however, hardly account for possibilities or even incentives for states or institutions to circumvent EU law. Inspiration can be drawn from studies of non-compliance in the EU, where a crude cost-benefit analysis is employed to explain compliance and enforcement (cf. Hofmann Citation2018).

In the absence of theories covering the whole spectrum of de facto differentiation, rational choice theory appears well suited to explain what is, in essence, the result of decisions made by states and EU institutions. To use a meta-theory like rationalism in this context, several conceptual concessions must be made and clarified. First, rational choice theory assumes unitary actors. In this case, two such actors can be assumed, a differentiation-seeking state on the one side and the EU comprising all remaining members and its supranational institutions on the other. Second, actors are expected to make decisions in order to maximise or satisfy their utility. Third, these decisions are subject to a set of institutional or societal constraints which influence the costs and benefits rational actors weigh when making decisions. Finally, rationalism may contain normative properties, prescribing what rational actors ought to do. But here it is instead applied as a positive theory generating expectations about actors’ decision-making.

From a rationalist perspective, the existence of de facto differentiation in the EU is puzzling. On the surface, utility advantages over de jure differentiation are not immediately discernible. Instead, there are costly side-effects for both involved actors.

The differentiation-seeking state’s costs of de facto differentiation differ depending on the type. Types 1 and 2 create an ambiguous legal situation at best. Because there is no legal basis, the EU can challenge such arrangements (Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2019). At worst, states involved in type 1 may suffer from all the negative consequences of non-compliance. Most notably, the Commission’s infringement procedure may incur financial penalties. Further, bad press associated with court cases can decrease citizens’ satisfaction with their government (Chaudoin Citation2014). While these costs might not amass in tolerated arrangements of de facto differentiation, non-compliant states still diminish their reputation among other member states (Downs and Jones Citation2002). Similarly, states pushing for further integration outside EU law according to type 3 risk gaining a divisive image. For instance, the establishment of the ESM during the eurozone crisis sparked fears of creating a new core EU-17 that would side-line the remaining non-euro states (Avbelj Citation2013). In comparison, the costs of de jure differentiation are limited. Studies have shown that even states with several opt-outs neither lose influence nor credibility in the Union if they play a constructive and active role (cf., Adler-Nissen Citation2009). But if blocking deeper integration becomes habitual and demanding legal opt-outs the default policy, states risk being considered an ‘awkward partner’ like the UK (George Citation1990).

For the EU as a whole, and in particular its supranational bodies, de facto differentiation is an especially heavy burden to bear. All three types undermine EU law, albeit to varying degrees. Founded as a ‘community of law’ and in absence of a full-fledged supranational executive authority, the integrity of its legal framework is crucial to ensure order within the Union. Moreover, de facto differentiation adds to the generally undesired fragmentation of policy areas. Despite its widespread de jure application, differentiation is still but a tolerated practice, as uniform integration remains the norm (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020, 35).

Against that backdrop, the costs of de jure differentiation appear lower. A rationalist perspective provides two possible propositions of which one must be true for both actors to explain the existence of tolerated arrangements of de facto differentiation nonetheless:

P1: The presumably more desirable de jure option may be unavailable while de facto differentiation provides still more utility than no differentiation.Footnote2

P2: Inherent benefits of de facto differentiation trump the utility gained from choosing de jure or no differentiation.

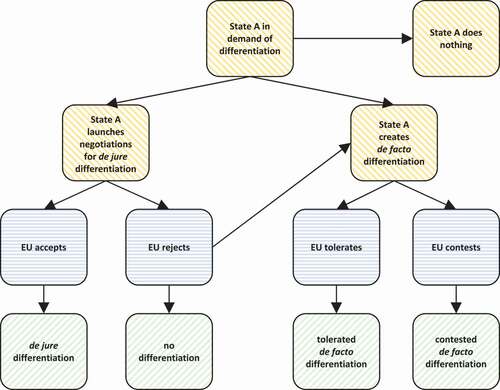

To assess these presumptions systematically, it is important to understand how de facto differentiation can be established and under what conditions the respective decisions are made. This is modelled in which outlines the process beginning with state A experiencing demand for differentiation, followed by the actions available to A and its counterpart, the EU.Footnote3 First, each actor’s preference orderings must be clarified.

Assuming state A to be in demand for differentiation, this is conventionally seen as a result of divergent preferences, capacity, and/or dependence (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020, 24–30). The origins of such divergence from the EU norm are traditionally explained by engaging with integration theories (cf. Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2019) or by taking cues from the schools of institutionalism (cf. Verdun Citation2015). The nature and strength of this demand likely affect the state’s decision-making. Facing strong demand, regardless of its origin, it is unlikely that the state ‘does nothing’ in response. In this case and taking into account the costs of de facto differentiation, state A’s preference ordering is:

de jure differentiation > de facto differentiation > no differentiation.

While individual states may prefer differentiation in some areas, the EU as a collective, and certainly its supranational institutions, generally aim for uniform integration. This is i.a. because differentiation renders supranational policy-making more complex and less efficient (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020, 35–36). The prevalence of unanimous decision-making despite qualitative majority voting in the EU Council further suggests that member states, too, mostly prefer uniform integration. It is common practice in EU policy-making that initial differences among member states and between EU institutions are settled in the so-called trilogues ahead of Council votes (e.g. Novak, Rozenberg, and Bendjaballa Citation2021). If uniform integration was not the default preference, this effort could be spared, and each member state be provided with the exemption it desires in the manner of DI. Finally, the EU can be safely expected to avoid any undermining of the legal framework it created and is tasked to preserve. Thus, the EU’s preference ordering is:

no differentiation > de jure differentiation > de facto differentiation.

Assuming high demand for differentiation, the model shows two pursuits of action available to state A. One is to launch negotiations with the EU about de jure differentiation if this is the more desirable solution (P1). At this point, the outcome is largely in the hands of the EU, as shown by the supply and demand model developed by Holzinger and Tosun (Citation2019). Dependent on various factors such as the bargaining power of A, expected negative externalities and the institutional context, the EU may concede to de jure differentiation (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020, 30–37). If this is denied but high demand for differentiation requires action, A can still proceed to create de facto differentiation.

In general, states can establish de facto differentiation independent of the EU’s consent. Of course, non-compliance, unilateral opt-ins and integration outside the EU are by nature practices that require no involvement of the EU, which is not to say that de facto differentiation cannot result from an agreement between the two actors. If A expects de facto differentiation to yield most utility (P2), it can establish it right away without sounding out the availability of de jure differentiation.

The only possible actions left to the EU after A has initiated de facto differentiation is to either tolerate or contest it by taking legal or political action. The extent to which de facto differentiation is contestable depends on the type but is also highly case specific. In case of type 1, the EU has at its disposal the entire arsenal of legal measures to enforce compliance such as financial sanctions. Types 2 and 3 can only be met with political pressure, for instance by making future membership of third states contingent on revoking type 2 de facto differentiation. The repercussions of taking legal or political action feed into the EU’s calculation of utility (P1, P2).

Ultimately, and to reiterate the rationalist propositions advanced earlier, two paths can lead towards tolerated de facto differentiation. It can either be a second-best choice if de jure differentiation is unavailable or offer certain advantages that make it the more desirable solution to high demand for differentiation. The following case studies put both to the test.

De facto differentiation in Economic and Monetary Union

Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was established as part of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and comprises a set of policies aimed at the economic convergence of EU member states. Integration in EMU is a three-staged process at the end of which states are entitled to adopt the euro. Because full participation is further contingent on the fulfilment of five economic convergence criteria, EMU is by default a differentiated policy area.Footnote4 In addition, EMU is also home to all three types of de facto differentiation.

This section presents three case studies corresponding to each type of de facto differentiation: (1) Sweden’s de facto opt-out from EMU (non-compliance), (2) Kosovo’s unilateral adoption of the euro (unilateral opt-in), and (3) the Fiscal Compact (integration outside EU law). Each is a long-lasting instance of de facto differentiation clearly tolerated by the EU and, thus, suitable to assess the underlying mechanisms.

The case studies serve as a plausibility probe for the two theoretically grounded propositions. They provide empirical illustrations of the proposed mechanism and examine what factors inherent to de facto differentiation might make it a utility enhancing arrangement or second-best choice. Remaining within the limits of a single policy area was more than a simple matter of space and feasibility. The restriction to cases within EMU increases the comparability of the three otherwise rather distinct types of de facto differentiation.

Qualitative data were gathered using both primary and secondary sources. This involved evaluating publicly available documents such as press statements, reports and other official data issued by the EU and the respective differentiation-seeking state(s). For cases (1) and (3) a significant body of research could also be drawn upon. In addition to that, a total of 11 interviews were conducted with experts from both sides, covering each case. Interviewees include former or still active national or EU officials, members of parliament, ministers, public administrators, researchers and other experts.

Sweden’s de facto EMU opt-out

Sweden joined the EU in 1995, and although the public at the time was sceptical of replacing the Swedish krona with the euro, the government refrained from negotiating a legal opt-out like Denmark and the UK did before. According to the Treaty of Maastricht, this meant that Sweden became obliged to adopt the euro once the convergence criteria are met. However, the Swedish government had always been hesitant towards the euro and voters ultimately rejected it by referendum in 2003. Since then, successive Swedish governments have deliberately left one of EMU’s convergence criteria unfulfilled – joining ERM – and tie a future adoption of the common currency to another decision by referendum.

Against that backdrop, this case can be seen as de facto differentiation on the basis of non-compliance. This point is driven home by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) annual convergence reports which consistently stress that ‘Sweden has been under the obligation to adopt national legislation with a view to integration into the Eurosystem since 1 June 1998. As yet, no legislative action has been taken by the Swedish authorities […]’ (European Central Bank Citation2020). The Swedish government, however, maintains the position that membership in the ERM is voluntary – and, therefore, by extension the adoption of the euro (Campos, Coricelli, and Moretti Citation2016).

Despite being at odds concerning the legality of Sweden’s de facto opt-out, it is to this day clearly tolerated (interviews 1–4). Only in the immediate aftermath of the 2003 referendum, statements of EU officials and eurozone governments suggested some (very mild) backlash (cf. Spiteri Citation2003; BBC Citation2003). Very soon, however, the issue disappeared entirely from public debates in Brussels, Stockholm, and other parts of the EU. Several factors indicate that this is because de facto differentiation has been the preference of both Sweden and the EU all along.

With the clear result of the referendum, the Swedish government had no other choice but not to adopt the euro. Choosing no differentiation (no opt-out) would have been political suicide and made a mockery of democracy. The de jure opt-outs given to Denmark and the UK, however, raise the question why Sweden never pursued a similar solution. Instinctively, one might posit that Sweden did not deem it likely to receive a formal opt-out. After all, Denmark and the UK were in the favourable bargaining position of possessing veto power in the Maastricht Treaty negotiations.

Immediately after the referendum this seemed plausible. In that regard, a statement by former Commission spokesman on economic and monetary affairs Gerassimos Thomas after the referendum is indicative. He pointed out Sweden’s treaty obligations but left it to the member states to decide whether Sweden should be given an opt-out, adding that it was ‘the view of the Commission that no more opt-outs should be given’ (cited in Scally Citation2003). Moreover, Sweden would soon have had to negotiate not only with 14 but 24 member states after the 2004 enlargement round. If such negotiations had failed and Sweden had faced a decisive ‘no’ from the EU, the political necessity not to adopt the euro would have become harder to carry out.

Soon after the referendum, the Lisbon Treaty negotiations bestowed upon Sweden the same veto power to formalise its opt-out from EMU. Again, the Swedish government refrained, although other member states used their veto power to gain some concessions. Seyad (Citation2008) speculates that this signified an implicit political commitment to adopt the euro once public opinion springs in line. This corresponds with the then conservative government’s pro-euro attitude. Previously, some senior officials of the Social Democrats sought to seize this moment, but the majority in the party leadership and in parliament simply did not deem the issue important enough to make demands (interview 3). In other words, this de facto arrangement was considered adequate to meet demand for differentiation in EMU and the potential advantages of de jure differentiation negligible.

More than adequate, de facto differentiation may, in fact, have had a distinct benefit. Several scholars attest Swedish governments to follow a ‘politics of low visibility’ (cf. Lindahl and Naurin Citation2005). This approach serves the purpose to preserve the image of a cooperative, integration-friendly member state rather than an awkward partner with opt-outs. Indeed, since the referendum, the euro has been a non-issue in Swedish domestic politics and public discourse (interviews 1–4). A rare exception was conservative PM Fredrick Reinfeldt’s plea for the euro in 2009, which failed to spark a serious debate (Reinfeldt Citation2009). In addition to keeping its de facto opt-out under the radar, Sweden succeeds to cover it up with reliability and committed cooperation in other policy areas (Brianson and Stegmann Mccallion Citation2020). Hardly possible with a de jure opt out, the lower visibility of de facto differentiation allows Sweden to have the best of both worlds.

Faced with Sweden’s decision for de facto differentiation, the EU was left to decide whether to tolerate or to contest it. In principle the Commission could have taken Sweden to court for violation of the Treaties, but this was and remains politically impossible. Trying to force Sweden to adopt the euro against citizens’ democratically expressed will would likely have destabilised the Union and stoked Eurosceptic sentiments not only in Sweden but across Europe. Thus, the EU’s first preference of uniform integration was unavailable.

Left with de facto or de jure differentiation, the costs of the former actually seemed lower. Either way, the EU would have to concede to more differentiation in EMU, but offering a de jure opt-out at the time appeared riskier for the EU. In view of the impending accession of ten new member states which might make similar demands, the EU was arguably prudent to not openly make any more concessions with regards to the common currency.Footnote5

Interestingly, interview data (3, 4) suggests that the Swedish opt-out has been a two-way bargain from the beginning. Apparently, the Swedish government and the Commission verbally agreed that to secure public support for EU membership in the 1994 referendum, the euro issue should be left aside, and Sweden never be pushed to adopt it against its will. The EU conceded to this because expanding membership to Scandinavia was a prime objective at the time. The Commission, however, insisted on the informality of this agreement because it was unwilling to cede further opt-outs from EMU.

In summary, this case corresponds with P2. De facto differentiation arguably provides most utility for both Sweden and the EU. For Sweden, the low visibility of this arrangement allows the government to uphold the role as a decidedly pro-integration member and to continue using the krona. The EU saves face, being spared from having to concede to additional legal opt-outs from EMU, and it can live with the relatively few negative externalities the situation has produced.

Kosovo’s de facto EMU opt-in

Kosovo formally adopted the euro as its sole official currency in January 2002.Footnote6 This step is rooted in decisions made after the war with Serbia had ended in June 1999. Following several periods of hyperinflation in the 1990s, trust in the previously shared dinar was low, and a stable currency was necessary to rebuild the country after the ravages of war. Thus, the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) quickly passed regulation allowing the use of the Deutsche Mark (DM) and other currencies as legal tender. The DM soon became the de facto currency, as it was already in wide circulation and foreign aid mostly delivered in cash (Svetchine Citation2005). With the impending cash changeover in the eurozone, Kosovo followed suit, supported again by UNMIK regulation.Footnote7

The adoption of the euro by non-EU states expands the eurozone, even if only in the use and not in the governance of the common currency. Therefore, this case can be seen as de facto differentiation by unilateral opt-in. The unilateral nature of the adoption of the DM and later the euro was made clear by then German Bundesbank President Ernst Welteke. At a 2001 press conference, he explained that these steps required no participation of the Bundesbank and that there were no inquiries concerning the central bank’s approval (Bundesbank Citation2001a).

To this day, the EU has never explicitly criticised Kosovo for its de facto opt-in (interview 5). Instead, ECB directives helped to facilitate the transition, albeit unintentionally (interview 7). For instance, regulation was passed that facilitated the logistics of switching to the euro outside the eurozone.Footnote8 In general though, the EU strictly opposes unilateral euroisation (interview 6, 7). In November 2000, an ECOFIN council report clarified that “any unilateral adoption of the single currency (…) would run counter to the underlying economic reasoning of EMU in the Treaty, which foresees the eventual adoption of the euro as an endpoint of a structured convergence process (ECOFIN Citation2000). This position was seconded by an EU Commission report following the same argumentation (European Commission Citation2002).

For Kosovo, the initial decision to adopt the DM created a lock-in effect in that the impending replacement of legacy currency with the euro almost necessitated the young Balkan state to follow suit (interviews 5–10). In principle, Kosovo could have replaced the DM with any other publicly traded currency or created its own. While the former would have posed at least logistical issues related to the import and exchange of coins and banknotes, the latter would have put Kosovo’s fledgling economy at risk because it was largely import-oriented and, thus, benefited from the stability of the DM. Consequently, the adoption of the euro was nearly inevitable, leaving open only the question of how to do it.

As the euro is technically reserved for EU members, a de jure solution for Kosovo could only have mimicked the bilateral treaties between the EU and the microstates Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City. These allow and regulate the use of the common currency, including an allocated quota to mint coins. Whether such an arrangement could have been reached is highly questionable. The microstates’ historically close relationships with their larger EU neighbours facilitated these treaties (interview 7, 8), and so did, probably, their very sound economic indicators. In all these regards, Kosovo was lacking.

But in view of plans to join the EU in the future, a legal agreement might have been beneficial for Kosovo. Granting membership to a unilaterally euroised state would set a precedent and pose certain legal and political obstacles. The progress made since suggests, however, that the unilateral use of the euro does not (yet) pose an issue for eventual EU integration (interview 9). Indeed, neither Kosovo’s Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the EU (Council of the Council of the European Union Citation2015), nor the Commission’s annual report on its implementation mention the country’s use of the euro (European Commission Citation2020). The ECB’s annual reports on the international role of the euro acknowledge its status in Kosovo but do not criticise it (European Central Bank Citation2020). However, interviews with EU Commission and ECB officials suggest that unilateral euroisation might become an issue in the future, as shown by the current membership negotiations with Montenegro (interview 6, 7). Yet, Kosovo never approached the EU about a de jure opt-in.

Kosovo’s decision to unilaterally adopt the euro has been tolerated by the EU ever since. It should be noted that the EU does not possess legal means to undo it. The Treaties’ provisions that bind the adoption of the euro to fulfilling the convergence criteria apply only to their signatories. Moreover, the euro is a freely traded currency and any state, in principle, may adopt it as legal tender. However, the EU’s political power over membership candidates is significant and could be used to prevent unilateral euroisation.

But the EU has had little to gain from building up political pressure since the negative externalities of Kosovo’s use of the euro are marginal. Due to the small size of Kosovo’s economy, its use of the euro hardly affects the eurozone (interview 6, 7, 9). Moreover, the ECB bears no responsibility for Kosovo (Bundesbank Citation2001b, interview 7). And lastly, the issue of granting EU membership to a state already using the euro lay far in the future at the time, and still does today. The consequences of contesting or formalising the opt-in seemed far worse. Denying war-torn Kosovo access to the euro would not only have sent a devastating message in and around the EU, it would also have undermined the EU’s foreign policy objective of Western Balkan allegiance to Europe and medium-term integration in the EU (Keil and Arkan Citation2015).

With ‘no differentiation’ out of the picture, de jure differentiation as offered to the four microstates would have been problematic as well. Officially extending EMU to third states irrespective of the fulfilment of the convergence criteria would have further eroded the conditionality of eurozone membership and might have attracted other states seeking access to the euro (interview 8, 9). Kosovo’s contested statehood was and is another obstacle, as e.g. Spain or Greece might have objected to signing a bilateral treaty with a state they do not recognise (interview 10).

Against that backdrop, de facto differentiation was arguably the best solution for the EU. It serves the purpose of maintaining monetary stability in Kosovo without incentivising the unilateral adoption of the common currency in general. The EU also maintains the option to impose upon Kosovo the fulfilment of the Maastricht criteria if accession talks with Kosovo eventually intensify.

To sum up, for Kosovo the decision to unilaterally adopt the euro corresponds with P1. While de jure differentiation would have given Kosovo at least more legal security with regards to future EU accession, the de facto solution suffices to meetthe primary objective of monetary stability. For the EU, tolerating Kosovo’s choice has arguably been the best available option in line with P2. It helped stabilise Kosovo’s economy and cast a positive light on the EU without actively promoting the euroisation of third states.

The treaty on stability, coordination and governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (Fiscal Compact)

The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (TSCG) is commonly referred to as the Fiscal Compact, after the title of the third and most significant section of the treaty. The TSCG is an intergovernmental treaty signed in March 2012 by all EU member states except the UK and Czechia. It formed a major part of the EU’s response to the sovereign debt crisis that hit Europe in 2009. The TSCG expands the Stability and Growth Pact and contains several measures to ensure and enforce fiscal discipline, establish closer economic policy coordination and institutionalise the governance of the eurozone. All eurozone states are bound to implement these measures, while other signatories may opt-in.Footnote9 The Commission assumes the task to monitor compliance and shares the right with other contracting parties to bring non-compliant states before the ECJ. The final say over enforcement lies, however, with the signatory states (Dehousse Citation2012).

The TSCG can be seen as a case of de facto differentiation by integration outside of EU law as it clearly expands the scope and centralisation level of the EU. It is somewhat special because the Commission actively participated in its establishment. However, the Commission was adamant to include a clause in the treaty that foresees transposition into EU law after five years. As yet, no notable steps have been taken in that regard, and, according to the EU Council, the current state of the TSCG as an international treaty works just fine (interview 11). In that regard it should be noted that interview data gathered by Laffan and Schlosser (Citation2015) suggest that the treaty is perceived by the EU as toothless and largely symbolic (‘no one cares about it’).

But why, then, was the Fiscal Compact pushed through ‘in a rush’ (ibid)? At the time, governments and the EU institutions faced immense pressure from businesses and the citizenry to present timely solutions to the eurozone crisis. Crucially, voters were losing trust in the EU and their own governments as the financial and labour markets began to flounder. Doing nothing would have shown weakness and inability to address a financial crisis the EU and in particular EMU were widely blamed for. Against that backdrop, the eurozone states and the EU institutions sought to respond by deepening integration.

The solutions proposed, however, would have required amendments to the Treaties. Met with immediate resistance from the UK and later Czechia, uniform integration was no longer on the table, leaving only differentiated integration. Not only unwilling to participate in the Fiscal Compact, the Cameron government demanded concessions that went far beyond a simple de jure opt-out.Footnote10 Even conceding to all British demands and granting de jure opt-outs, the lengthy process of Treaty reform that requires majorities in all national parliaments and, in some cases, even referenda rendered a quick solution within EU law unfeasible (interview 11).

Eager to present a quick crisis response, the other EU members and the Commission decided to circumvent the British veto by concluding a separate treaty outside EU law (Verdun Citation2015). For the EU, the TSCG being an international treaty rather than a piece of EU legislation meant that the supranational institutions would have to accept that member states remained in control of fiscal policy. Especially for the Commission this was a clear downside, somewhat remedied by the clause mandating its later transposition into EU law. And so, Commissioner Oettinger stated that the TSCG was a ‘good, second best solution’ (Volkery Citation2011). For the signatory states, the TSCG being an intergovernmental treaty was no problem. So much so, that even though all EU member states have by now signed the treaty, its transposition into EU law is not even on the agenda.

Two related rationalist explanations can be advanced. First, surrendering their power of enforcement provides no utility to the signatory states. Second, following the tradition of the EU’s other fiscal policy instruments, the member states may even prefer the Fiscal Compact being toothless. Perhaps considering the by now largely symbolic nature of the TSCG, one could even argue that the EU, too, prefers its lower visibility outside the acquis over having to deal with a nearly dead piece of legislation within the legal framework of EMU.

To sum up, the TSCG confirms P2 for the signatory states while for the EU institutions it was a second-best choice (P1). But only thus could a timely and pragmatic solution be reached and conceding to the UK’s outlandish demands be averted. Even now, while the EU institutions likely still prefer it being integrated in EU law, the absent progress in that regard suggests that the Fiscal Compact is not important enough and that the signatory states prefer its status as an international treaty outside the EU legal framework.

Conclusion

Seen through the lens of the rationalist model developed in this article, the three case studies reveal a clear purpose of de facto differentiation within the EU’s system of differentiated integration. Of course, the findings of this article are not fully generalisable as data is limited to three cases within one policy area. Still, even across all three types of de facto differentiation and very different cases, a clear pattern has become visible. Most often more than just a second-best option, it may serve to make EU integration more flexible when strong national demand for differentiation meets the need for discretion or timely, pragmatic action.

The added flexibility shows – to varying extent – in all three cases. If public opinion shifts, Sweden can still initiate the adoption of the euro at any time without having to overturn a legal opt-out, while the EU can in principle try to coerce Sweden into doing so. Kosovo can use the euro without having to comply with the convergence criteria, while the EU’s monetary policy remains unaffected, and it can change the terms of this arrangement as part of future accession negotiations. Finally, the TSCG’s intergovernmental structure offers a lot more leeway in enforcement than if it were integrated in EU law.

The lower visibility is another beneficial factor found in all cases. Sweden’s de facto opt-out is more suitable to preserve the image of an integration friendly core member state rather than an ‘awkward partner’ with opt-outs, and the EU saves face by not having to officially concede to more deviations in EMU. Similarly, by simply tolerating Kosovo’s unilateral adoption of the euro, the EU did not officially sanction euroisation in third states, which could have attracted other states to follow. And the now largely symbolic and defunct Fiscal Compact is perhaps best left for dead outside than within EU law.

Lastly, the unbureaucratic nature of de facto differentiation may be more efficient when urgency demands swift action. This was certainly the case of the TSCG conceived as a remedy to a crisis that necessitated swift action. Even conceding to the British demands and instating de jure differentiation by reforming the Treaties would arguably have taken too long and risked being rejected in national parliaments and referenda.

These findings cast a largely positive light on de facto differentiation, but it is important to stress that there is a serious caveat. While the cases studied in this article were rather benign, each instance of de facto differentiation not only undermines the uniformity of integration but, crucially, erodes the EU’s legal foundations in the respective policy area. This poses several normative questions regarding European integration. For example, what are the implications for the EU – a community of law – if its own legal framework is regularly and purposefully circumvented? And how much de facto differentiation can the EU bear without compromising its foundations? Addressing these questions exceeds the pursuit of expanding academic knowledge. If left unanswered, the EU and the integration project as such risk losing credibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Schimmelfennig and Winzen (Citation2020, 55) found de jure differentiation to last on average several years, while infringement procedures are usually closed after just over a year (Hofmann Citation2018). In order to place de facto differentiation in the same category, short-term deviations from the norm cannot be considered.

2. The term ‘no differentiation’ was chosen for its applicability in all types and cases of de facto differentiation. It can either refer to the status quo (no integration) or uniform integration.

3. Less realistic or more drastic options were omitted. For instance, a state seeking an opt-out from a certain policy could challenge its legality in court. The likelihood of winning such cases at the ECJ is very low, especially if it concerns a long-established policy. Theoretically, a state might choose to leave the EU rather than comply with a certain policy. It is, however, unlikely that taking this option precedes attempts to negotiate a de jure opt-out or to establish de facto differentiation.

4. The five criteria include pre-defined rates of inflation and long-term interest, a maximum of 3% annual budget deficit to GDP, a 60% limit of overall debt to GDP, and participation in the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) which pegs national currencies to the Euro.

5. With hindsight, this expectation has proven wrong. Poland, Czechia, and Hungary have basically copied the Swedish approach.

6. Montenegro has also unilaterally adopted the euro despite not being a member of the EU.

7. See UNMIK/DIR/2001/24: https://unmik.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/regulations/02english/E2001ads/ADE2001_24.pdf

8. See for example guideline ECB/2001/8 which allowed Kosovo’s Central Bank to frontload €100m in cash ahead of 1 January 2002,

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32001O0008&qid=1614092665179.

9. Denmark and Romania have chosen to opt-in and to comply with the entire set of measures. Bulgaria maintains a partial opt-in and is only bound to the fiscal measures.

10. See for example: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/dec/09/david-cameron-blocks-eu-treaty.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2009. “Behind the Scenes of Differentiated Integration: Circumventing National opt-outs in Justice and Home Affairs.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1080/13501760802453239.

- Andersen, S. S., and N. Sitter. 2006. “Differentiated Integration: What Is It and How Much Can the EU Accommodate?” European Integration 28 (4): 313–330. doi:10.1080/07036330600853919.

- Avbelj, M. 2013. “Differentiated Integration – Farewell to the EU-27?” German Law Journal 14 (1): 191–211. doi:10.1017/S2071832200001760.

- BBC. 2003. EU Regrets Sweden’s Vote on Euro, September 15. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/3110492.stm

- Börzel, T. A., T. Hofmann, and D. Panke. 2012. “Caving in or Sitting Out? Longitudinal Patterns of non-compliance in the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (4): 454–471. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.607338.

- Brianson, A., and M. Stegmann Mccallion. 2020. “Bang-a-boomerang? Sweden, Differentiated Integration and EMU after Brexit.” In Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in a post-Brexit Era, edited by S. Gänzle, B. Leruth, and J. Trondal, 146–164, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Bundesbank. 2001a. Protokoll der Pressekonferenz der Deutschen Bundesbank am 25, June 2001. https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/680776/de35209f604e001e9982c5387be15775/mL/2001-06-28-pressekonferenz-46366-download.pdf

- Bundesbank. 2001b. “Protokoll der Pressekonferenz Im Europäischen Haus in Berlin Am 17.” DM-Bargeld-Umtausch in Osteuropa und der Türkei. July 2001. https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/680800/12531884e5cb14797c8b12a138dbf961/mL/2001-07-17-pressekonferenz-46216-download.pdf

- Campos, N. F., F. Coricelli, and L. Moretti. 2016. “Sweden and the Euro: The Neglected Role of EU Membership.” SIEPS European Policy Analysis 2016: 15.

- Chaudoin, S. 2014. “Promises or Policies? An Experimental Analysis of International Agreements and Audience Reactions.” International Organization 68 (1): 235–256. doi:10.1017/S0020818313000386.

- Cianciara, A. K., and A. Szymanski. 2020. “Differentiation, Brexit and EU-Turkey Relations.” In Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in a post-Brexit Era, edited by S. Gänzle, B. Leruth, and J. Trondal, 182–202, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Council of the European Union. 2015. “Stabilisation and Association Agreement.” https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10728-2015-REV-1/en/pdf

- Dehousse, R. 2012. “The Fiscal Compact: legal uncertainty and political ambiguity, Notre Europe Policy Brief.” https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/fiscalpact_r.dehousse_ne_feb2012_01-1.pdf

- Downs, G.W., D.M. Rocke, and P.N. Barsoom. 1996. “Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?” International Organization 50 (3): 379–406. doi:10.1017/S0020818300033427.

- Downs, G.W., and M.A. Jones. 2002. “Reputation, Compliance, and International Law.” The Journal of Legal Studies 31 (S1): 95–114. doi:10.1086/340405.

- ECOFIN. 2000. “2301st Council Meeting, Brussels 7 November.” https://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/ecofin/ACF717B.htm

- Eriksen, E. O. 2019. Contesting Political Differentiation - European Division and the Problem of Dominance. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- European Central Bank. 2020. “Convergence Report.” https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/convergence/html/ecb.cr202006~9fefc8d4c0.en.html

- European Commission. 2002. “The Euro Area in the World Economy – Developments in the First Three Years.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52002DC0332&from=EN

- European Commission. 2020. “Commission Staff Working Document – Kosovo 2020 Report.” https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/kosovo_report_2020.pdf

- Gänzle, S., B. Leruth, and J. Trondal. 2020. Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in a post-Brexit Era. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- George, S. 1990. An Awkward Partner. Britain and the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hofelich, T.C. 2022. “De Facto Differentiation in the European Union – Circumventing Rules, Law, and Rule of Law.” In Routledge Handbook of Differentiation in the European Union, edited by B. Leruth, S. Gänzle, and J. Trondal, 66-80. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge .

- Hofmann, T. 2018. “How Long to Compliance? Escalating Infringement Proceedings and the Diminishing Power of Special Interests.” Journal of European Integration 40 (6): 785–801. doi:10.1080/07036337.2018.1500564.

- Holzinger, K., and F. Schimmelfennig. 2012. “Differentiated Integration in the European Union: Many Concepts, Sparse Theory, Few Data.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (2): 292–305. doi:10.1080/13501763.2012.641747.

- Holzinger, K., and J. Tosun. 2019. “Why Differentiated Integration Is Such A Common Practice in Europe: A Rational Explanation.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 31 (4): 642–659. doi:10.1177/0951629819875522.

- Howarth, D. 2010. “Industrial’ Europe: The Softer Side of Differentiated Integration.” In Which Europe? The Politics of Differentiated Integration, edited by K. Dyson and A. Sepos, 233–250, Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Keil, S., and Z. Arkan. 2015. The EU and Member State Building – European Foreign Policy in the Western Balkans. Oxon: Routledge.

- Kleine, M. 2013. Informal Governance in the European Union – How Governments Make International Organizations Work. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Laffan, B., and P. Schlosser (2015). “The rise of a fiscal Europe? Negotiating Europe’s new economic governance.” EUI Research Report. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/36482/FBF_RR_2015_01.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Lavenex, S. 2015. “The External Face of Differentiated Integration: Third Country Participation in EU Sectoral Bodies.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (6): 836–853. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1020836.

- Leruth, B., S. Gänzle, and J. Trondal. 2019. “Exploring Differentiated Integration in a Post-Brexit European Union.” Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (5): 1013–1030. doi:10.1111/jcms.12869.

- Leuffen, D., B. Rittberger, and F. Schimmelfennig. 2022. Integration and Differentiation in the European Union – Theory and Policies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lindahl, R., and D. Naurin. 2005. “Sweden: The Twin Faces of a Euro-Outsider.” European Integration 27 (1): 65–87. doi:10.1080/07036330400029983.

- Novak, S, O Rozenberg, and S. Bendjaballa. 2021. “Enduring Consensus: Why the EU Legislative Process Stays the Same.” Journal of European Integration 43 (4): 475–493. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1800679.

- Pollack, M.A. 2006. “Rational Choice and EU Politics.” In The SAGE Handbook of European Union Politics, edited by K.E. Jørgensen, M.A. Pollack, and B. Rosamond. London: SAGE Publications.

- Reinfeldt, F. 2009. “Swedish PM Reignites Euro Debate.” Euractiv, September 1. https://www.euractiv.com/section/euro-finance/news/swedish-pm-reignites-euro-debate/

- Scally, D. 2003. “Vote Seen in Brussels as euro-sceptic Snub.” The Irish Times, September 16. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/vote-seen-in-brussels-as-euro-sceptic-snub-1.376091

- Schimmelfennig, F, and T. Winzen. 2019. “Grand Theories, Differentiated Integration.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (8): 1172–1192. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1576761.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and T. Winzen. 2020. Ever Looser Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sczepanski, R., and T. Börzel. 2021. “Two Sides of the Same Coin? The Effect of Differentiation on Non-compliance with EU Law.” paper presented at ECPR General Conference 2021, https://ecpr.eu/Events/Event/PaperDetails/56826

- Seyad, S.M. 2008. “The Lisbon Treaty and EMU, SIEPS European Policy Analysis, Issue 4 2008.” https://www.sieps.se/en/publications/2008/the-lisbon-treaty-and-emu-20084epa/

- Snidal, D. 2002. “Rational Choice and International Relations.” In Handbook of International Relations, edited by W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, and B.A. Simmons. London: SAGE 85–111.

- Spiteri, S. (2003). “Solbes: All EU Countries Expected to Join the Euro.” EU Observer, September 15. https://euobserver.com/economic/12691

- Svetchine, M. 2005. “Kosovo Experience with Euroization of Its Economy.” https://www.bankofalbania.org/rc/doc/M_SVETCHINE_en_10164.pdf

- Tallberg, J. 2002. “Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management, and the European Union.” International Organization 56 (3): 609–643. doi:10.1162/002081802760199908.

- Verdun, A. 2015. “A Historical Institutionalist Explanation of the EU’s Responses to the Euro Area Financial Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (2): 219–237. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.994023.

- Volkery, C. 2011. “The Birth of a Two-Speed Europe.” Der Spiegel, November 9. https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/split-summit-the-birth-of-a-two-speed-europe-a-802703.html

- Zhang, Y. 2021. “Limits of Law in the Multilevel System: Explaining the European Commission’s Toleration of Noncompliance Concerning Pharmaceutical Parallel Trade.” Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (4): 1001–1018.