ABSTRACT

The public politicisation of European integration indicates a growing demand for public communication of supranational politics. This paper highlights that the messages the European Commission sends to its citizens do not meet this demand. A text analysis of almost 45,000 press releases the Commission has issued during 35 years of European integration rather indicates an extremely technocratic style of communication. Benchmarked against large samples of national executive communication, public political media, and scientific discourse, the Commission used and notably continues to use very complex language, specialized jargon, and a nominal style that obfuscates political action. This appears disadvantageous in a politicized context and more research on the reasons for this apparent communication deficit is needed.

1. Introduction

European integration is increasingly politicized in the public sphere. Public opinion on the European Union (EU) diversifies, public media engages critically with European decisions, and political parties compete over or even fundamentally challenge political cooperation in Europe. In these increasingly controversial public debates, the European Commission is a key addressee.

Where populists demonise an unelected Brussels elite, they do speak about the European Commission. Where partisan actors ravage about the neoliberal or socialist biases of European integration, they do speak about the policies proposed, defended, and partially implemented by the Commission. And where national governments look for a scapegoat to blame for policy failures, they do speak about the Commission (Gerhards, Offerhaus, and Roose Citation2009; Heinkelmann‐Wild and Zangl Citation2019). Explicit or implicit arguments about the European Commission thus feed back into how the wider public perceives European integration.

The Commission, however, is not only at the receiving end of these debates. Politicization is a discursive process (De Wilde Citation2011). The Commission has opportunities and resources to influence how its own image is construed in public debates. Media selection logics often disadvantage European messages (e.g. Trenz Citation2008), but since the 1990s, the Brussels press corps has been growing and is particularly attentive to the Commission (Meyer Citation2009; Raeymaeckers, Cosijn, and Deprez Citation2007). And while national executives are often preferred, public media do feature the Commission particularly in policy domains in which it holds competences (Koopmans and Erbe Citation2004). The Commission itself has repeatedly paid lip service to ‘better communication with European citizens’ and invested in organizational resources, strategies, and professional staff to this end (Brüggemann Citation2008; Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2018). Yet and still, the image of a detached technocracy sticks. Why?

This article argues that the lacking clarity of the Commission’s own public communication is part of the answer to that question. I first discuss the growing societal demand for public justification of European decision-making and highlight message clarity as a necessary condition for effective communication from the Commission to a politicized public. Yet, the Commission’s ambiguous institutional roles create mixed incentives for supplying such clear communication. Against this background, I provide a text analysis of the 44,978 press releases the Commission has issued between 1985 and 2020, generating three descriptive insights. First, this public communication from the Commission is notably harder to understand than political communication from national executives or public media reports on politics and rather resembles scientific discourse. Second, this technocratic way of communication is independent of the policy topics the Commission communicates about. Third, and most importantly, this has hardly changed over almost 35 years of European integration – a period in which both the Commission’s political competences and the public EU politicization grew markedly. In light of increasingly controversial public debates about European decision-making, thus, the Commission suffers from a remarkable behavioural ‘communication deficit’. This calls for more research into the organisational obstacles and/or strategic motives behind the cautious communication of Europe’s key supranational institution.

2. The demand for clear public communication from the Commission

Why care about the public communication of the European Commission? Intergovernmentalists traditionally see the Commission as a mere member state agent which operates in downstream, low-stake policy areas of little immediate relevance to the wider public (Keohane, Macedo, and Moravcsik Citation2009; Moravcsik Citation1998). Other accounts argue that the very purpose of delegating competences to the Commission lies in explicitly removing them from the quirks of public discussions that would impede cross-national consensus (Bartolini Citation2006; Majone Citation2002). A third set of readings, however, sees the Commission as a prime witness for lacking public accountability of EU decision-making (Featherstone Citation1994; Follesdal and Hix Citation2006; Tsakatika Citation2005). These readings suggest that the Commission’s decidedly political powers warrant being answerable to the wider public.

While the Commission probably oscillates between these extremes (Christiansen Citation1997), its political role in the integration of Europe has unquestionably grown over time (e.g. Hooghe and Marks Citation2001; Pollack Citation1997; Tsebelis and Garrett Citation2000). The Commission controls seizable leeway in areas of exclusive EU competence, such as competition policy or external trade. But also in the day-to-day integration through law (or ‘integration by stealth’ as some observers have it, Majone Citation2005) in conjunction with national governments and the European Parliament, the Commission controls precious power resources. As a stakeholder hub, it is a focal player in the informal stages of the policy cycle (Hartlapp, Metz, and Rauh Citation2014; Princen Citation2009). In the formal stages, the Commission’s choices matter as well. The number of policy areas with EU legislative competence has more than doubled between the 1987 Single European Act and the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon. In constantly around half of these policy areas, the Commission holds the exclusive right of legislative initiative (Biesenbender Citation2011). This first-mover advantage often allows the Commission to exert significant influence over the choices that its co-legislators in the Council and the EP ultimately take (Blom-Hansen and Senninger Citation2021; Rauh Citation2021b; Tsebelis and Garrett Citation2000). The Commission thus has some say in areas that can and do become rather salient for European citizens – think employment and social affairs, consumer protection, environmental policy, migration, or public health, for example.

The Commission also uses these powers extensively. Between 1990 and 2019, it has prepared, drafted, and formally tabled a total of 12,523 legislative proposals.Footnote1 Legislative production has slowed down since the heydays of the internal market programme, but the Commission still proposes 250 to 300 laws per year. The probability that these proposals become binding law has been constantly higher than 85% (Boranbay-Akan, König, and Osnabrügge Citation2017). In sum, its informal and formal agenda-setting powers as well as the high extent to which it uses them suggest that the Commission has quite some clout over the rules that govern Europe’s almost 500 million citizens.

Such growing political authority is likely to result in public politicisation (Zürn, Binder, and Ehrhardt Citation2012). The more supranational institutions can and do take collectively binding decisions, the more a broadening set of societal actors will learn that their vested interests are affected. And because many dissatisfied societal actors will air their demands in public arenas, controversial debates become visible to the wider public, thus affecting public opinion on European governance.

Public politicization does not necessarily grow linearly. It often requires ‘discursive opportunities’ such as policy crises, treaty reforms, referenda, or specific settings of domestic political competition (De Wilde and Zürn Citation2012; Hutter and Grande Citation2014). But there is clear evidence that European decision-making faces an increasing risk of becoming scrutinized in the public domain (Rauh Citation2021a). Media visibility of the EU, both in its means and its peaks, has increased over the last decades of European integration (Boomgaarden et al. Citation2010). There are also episodes of pronounced public protests against EU policies (Dolezal, Hutter, and Becker Citation2016; Uba and Uggla Citation2011). And European integration is now frequently a salient and often also divisive issue during partisan election campaigns (Hutter and Grande Citation2014). Average EU support among citizens decreased mildly over the last decades but the underlying distributions flatten out, suggesting moves towards a more polarised public opinion (Down and Wilson Citation2008).

The Commission thus cannot rely on the ‘permissive consensus’ that has characterized the infancy of European integration anymore. European decision-making has rather ‘shifted from an insulated elite to mass politics’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009, 13). What the Commission does (and what it does not do) is today much more likely to become debated in the public domain. Public support cannot be taken for granted. It rather has to be earned (Meyer Citation1999 aptly speaks of ‘meritocratic legitimacy’).

This is what makes the Commission's communication to the European public highly relevant. After all, public politicization is a discursive struggle (De Wilde Citation2011). We know that societal acceptance of institutions beyond the nation state is the product of communicative acts of de-legitimation and re-legitimation (Gronau and Schmidtke Citation2016; Schmidtke Citation2019; Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019). And we also know, that elite communication affects public support of such institutions (Dellmuth and Tallberg Citation2021; Gabel and Scheve Citation2007; Neuner Citation2018; Steenbergen, Edwards, and de Vries Citation2007). While the Commission can neither fully control public debates nor the actors mobilizing for or against European integration therein, it can at least try to meet public criticism by justifying and defending its role and choices in European politics.

Theories of democracy, accountability, or the public sphere offer a myriad of yardsticks to assess the quality of such political communication. Here, however, I focus on clarity as the most basic but also necessary condition for reaching an increasingly politicized public. This rests on three interrelated arguments.

First and foremost, message clarity indicates audience orientation. In traditional technocratic discourse, the Commission addresses a narrow set of audiences with high levels of background knowledge, such as representatives in the Council, Members of the European Parliament, or sectoral interest groups. For such knowledgeable audiences, it can resort to technical language, specialized vocabulary, and very condensed representations of decision-making processes. Public account giving, in contrast, addresses mostly non-specialists and is geared to clarify what the political executive does and why for all possibly affected audiences, independent of their level of background knowledge (Bovens Citation2007). The more the Commission wants to address the general public, thus, the better understandable its messages have to be.

Second, message clarity affects journalistic selection. Brussels journalists emphasize high workloads, an overabundance of information, and criticize EU institutions for a lack of focus and clear political lines (Statham Citation2008, 407–8). Journalists dislike information that is ‘complex’, ‘boring’, ‘abstract’, or ‘too institutional’ as it lets them ‘struggle to present EU issues in a comprehensible way that is attractive for the audience’ (Raeymaeckers, Cosijn, and Deprez Citation2007, 112–3). Especially, the Brussels’ jargon is flagged as an obstacle to journalistic work (Mancini et al. Citation2007, 125–7). As one journalist put it, ‘half of my work is to translate it [a press release] into normal words’ (Gleissner and de Vreese Citation2005, 227). Clearer communication, then, should increase the likelihood that journalists relay the message into the wider public sphere. This is confirmed by a recent study of public communication by the European Central Bank (Ferrara and Angino Citation2021): The clearer the press materials from the institution are, the higher the likelihood that it is actually featured in public media the following day.

Third, clarity affects how citizens perceive and process messages from the Commission. Journalistic writing relies heavily on the material that is originally provided by EU institutions (Lorenz Citation2017) so that citizens receive parts of the Commission’s original messages rather directly. Experimental evidence shows that message clarity has political effects at this stage as well (Bischof and Senninger Citation2022). On the one hand, citizens recall clearer messages more easily. On the other hand, citizens use language clarity (or, inversely, complexity) as a heuristic to assess their social distance to the message sender. Thus, if the Commission wants to increase EU knowledge among the public while avoiding anti-elite sentiment, clear language is key from this perspective as well.

To be sure, clarity does neither equal more emotional or more radical communication nor does it imply ‘dumbing down’ the often-complex political realities of European decision-making. But it means explaining these realities better for an increasingly attentive laymen audience beyond the directly involved stakeholders in the inter- or supranational realm. The more the Commission wants to give account to a broader public, the more accessible its language must be, the less specialized jargon it should use, and the more it must clarify what it is actually decided and done in Brussels. The public politicisation of EU decision-making indicates that there is a growing societal demand for such clear public justifications of supranational powers. But can we expect the Commission to meet this demand?

3. The supply of public communication from the commission

Again, the Commission’s ambiguous nature between being an apolitical technocracy and a political executive comes into play. Historically, Europe’s central executive did not have much of an appetite for public engagement (Brüggemann Citation2008; Gramberger Citation1997; Meyer Citation2002). When Jean Monnet, architect of the technocratic approach to European integration and first president of the Commission’s predecessor, met Emanuele Gazzo, founding director of the first European press agency, he had supposedly asked for stopping the publication activities immediately (reported in Brüggemann Citation2008, 120–1). The conviction that clear public communication was a risk rather than an opportunity stuck in the highest Commission echelons even during the takeoff of the internal market programme, the high period of the integration-through-law approach. Pascal Lamy, at the time Chef de Cabinet of Commission president Delors, stated that ‘the people weren’t ready to agree to integration, so you had to get on without telling them too much about what was happening’ (quoted in Ross Citation1995, 94).

But pronounced shocks of public EU politicization have slowly challenged this. The Delors Commission interpreted the rejection of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty in Denmark and its near failure in France as a public relations disaster. It therefore devised a marketing strategy to promote European integration advantages but hardly adapted its day-to-day approach to public communication (Brüggemann Citation2008, 123–4). Not acknowledging that political authority entails rising public scrutiny fired back quickly. When corruption allegations surfaced in 1996, the Santer Commission completely underestimated the public fallout. As one Commission spokesperson said: ‘we used to deal mainly with militant EU supporters. Now we are faced with more sceptical journalists who look at the Commission like a national government’ (quoted in Meyer Citation2009, 621).

Subsequent Commission presidents took public communication more seriously in response. Romano Prodi took responsibility for the spokesperson's service and developed it into a fully fledged Directorate-General (Brüggemann Citation2008, 139 pp.). It pursued a more pro-active approach, recognising that ‘an information and communication strategy matching real needs is a precondition for the success of the European Union’s initiatives’ (ibid.: 11). Commission communication, in Prodi’s view, should ‘improve perceptions of the European Union, its institutions and their legitimacy by enhancing familiarity with and comprehension of its tasks, structure and achievements’ (ibid, own emphasis). Public communication, in this reading, should indeed clarify how and to what ends supranational political authority is exercised.

The 2004 Barroso Commission even tasked a Commission vice-president with public communication. The outspoken Margot Wallström pushed her ‘Plan D’ (‘democracy, dialogue, and debate’) against internal resistance. Besides improved consultations, it proposed more centralized quality control of the Commission’s outbound communication via publications, websites, and press releases. In the wake of the failed constitutional referenda in France and the Netherlands, however, Commission president Barroso took the view that citizens did not care so much about how European decisions are produced and suggested a focus on a ‘Europe of results’.

These anecdotes initially illustrate the stickiness of the Commission’s self-perception of being primarily a detached and expertise-driven agency. This is also evident in Commission officials’ attitudes. In an exploratory study, Bes (Citation2017) finds that around half of the interviewed Commission officials do not see the need to adapt their institutional role conceptions in response to EU politicization in their home country. Brussels journalists also systematically complain that the information from the Commission does not present EU issues in a way that is understandable to their audiences (Raeymaeckers, Cosijn, and Deprez Citation2007 esp. 111–3; see also: Terzis and Harding Citation2014). As Meyer (Citation1999, 628) puts it, a ‘technocratic mindset’ prevails in the Commission so that ‘after months or years of experts’ work, potential public reactions are often properly considered only a few days before the proposal’s planned adoption’.

However, the historical overview also suggests strategically motivated learning. The Commission stepped up its communication efforts especially when pronounced politicization shocks threatened further political integration (cf. Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2018). Also in day-to-day policy making, public politicisation seems to create strategic incentives for proactively communicating to the European citizen. De Bruycker (Citation2017) finds that European elites, including Commission officials, stress public interest advantages especially when the issues they regulate attract civil society attention. Policy studies also indicate that Commission officials engage in strategic public communication when the issues they plan to regulate are publicly salient (Hartlapp, Metz, and Rauh Citation2014: Ch. 9; Rauh Citation2016).

But, of course, the general public is not the only audience the Commission has to please. After all, it is first and foremost accountable to the EU member state governments who nominate and possibly withdraw ‘their’ Commissioners. Institutional accountability to the wider citizenry is indirect at best and has only mildly improved through the investiture procedure, the possibility for censure motions in the EP, and the thus far hardly successful attempts to establish the Spitzenkandidaten process (Christiansen Citation2016; Hix Citation1997; Hobolt Citation2014; Wille Citation2013).

These mixed accountabilities may let the Commission refrain from taking clear public stances when vested national interests are affected. Public communication may then be rather driven by institutional risk-management vis-á-vis member state governments rather than the politicized public (Van der Veer and Haverland Citation2018). The Commission may thus also try to avoid clear stances on publicly contested issues so as not to add further fuel to the flames. During the Eurocrisis, for example, the public messages of Commissioners from countries with higher levels of Euroscepticism were less clear than those of their counterparts with more Europhile public discourses at home (Rauh, Bes, and Schoonvelde Citation2020).

In sum, the ambiguous institutional roles of the European Commission provide mixed incentives for communicating to the wider public in a clear manner. On the one hand, the Commission seems to have learnt that politicization entails more intense public scrutiny, rendering clear communication to the wider public politically important. On the other hand, a pervading technocratic mindset, multiple accountabilities, and the resulting strategic caution may dampen more outspoken public communication. Which of these two logics prevails in an aggregate judgment over time?

4. Commission press releases

To study this question empirically, I focus on the Commission’s efforts to send its messages to and through traditional public media. TV, radio, or the printed and online press are still key sources of political information for majorities of European citizens (Directorate-General for Communication Citation2018). The Commission addresses these media not the least with its press releases. For three reasons, these documents are particularly suited to gain a consistent, long-term, and policy-independent picture on the Commission’s willingness to send clear messages to the public.

First, unlike white, green, or other SEC papers, stakeholder consultations or working group meetings to communicate with traditional stakeholders directly, press releases are intentionally produced documents meant to convey a message to and through public media. They initially address journalists as possible multiplicators, but according to internal guidelines, they should be written with European citizens as the ‘intended receivers’ in mind (Lindholm Citation2008, 44). Typically, a press release is drafted by a policy desk official and then reviewed by the political Cabinets of the responsible Commissioners. The Commission’s spokesperson’s service finalises the text, again in interaction with the political Cabinets. Thus, a press release reflects the Commission’s chosen balance of policy, political, and communicative considerations.

Second, press releases allow us to observe the Commission’s preferred messages before journalistic selection or framing sets in. Media logics are often biased to national actors and frames, conflictual events, and negativity more generally (e.g. Trenz Citation2008). Press releases thus do not necessarily equal what the wider public ultimately hears from the Commission. But they do tell us what the Commission actually wants the wider public to hear. Press releases are meant to influence and to shape public discussion of a given topic, ideally in the direction the Commission deems most preferable. They are distributed prior to the Commission’s daily midday briefing where the Brussels’ press corps gathers in large numbers (Raeymaeckers, Cosijn, and Deprez Citation2007, 111) and they are written with anticipating possibly critical questions from this crowd (Lindholm Citation2008, 37, 44). Press releases are first written in English and are then translated directly to other EU languages (under the same IP document number, usually on the subsequent day at the latest, ibid: 45) and nowadays also feature directly on the top-level website of the Commission.

Third and finally, press releases are the most long-standing public communication channel of the Commission. While the Commission has recently invested heavily in social media (Özdemir and Rauh Citation2022), this channel does not allow studying long-term change and it remains unclear which segments of the wider public the Commission actually reaches on these platforms. With press releases, in contrast, the institution has had ample experience to learn how to work with this particular format and we can observe it over long time periods. Press releases thus allow us to examine the Commission’s audience orientation over those time periods in which both its political competences and the public politicisation of the EU increased markedly.

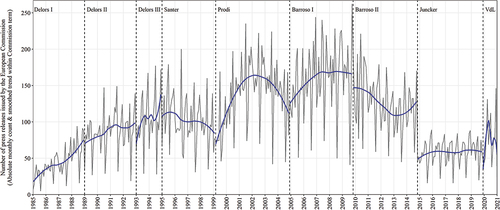

For these reasons, I have collected all 44,978 English-language press releases that the Commission has published between 17 January 1985 and 8 January 2021 from the official archives.Footnote2 The corpus published with this article offers headline, lead, and main text of each release with basic metadata. plots the monthly number of press releases that the Commission has issued over the last 35 years.

Besides regular August lows – a typical summer break pattern observable in most timelines of Brussels’ activity – this perspective highlights that press release output varies from one Commission term to the next. This is consistent with the view that public communication is a conscious choice of the Commission’s political leadership. Especially the strategic learning after the Santer fiasco in 1999 shows. Prodi’s prioritization of communication is reflected in an increase from around 100 to around 150 monthly press releases. The Barroso Commission sustained this but issued fewer press releases during its second term. But especially the marked drop during the Juncker Commission catches the eye. The self-declared ‘political Commission’ fell back to slightly more than 50 press releases per month which, however, coincides with an increasing output of social media messages from the Commission (Özdemir and Rauh Citation2022). In the first year of the Von der Leyen (VdL) presidency, press release output seems to have mildly increased again.

This raw amount of public information is not proportional to the growth of the Commission’s political competences. While press release output increased prior to Maastricht (1992), it stagnated afterward and was also not affected by the further authority transfer in the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam. The comparatively modest additional authority transfers in the Treaty of Lisbon (2009) were followed by even less public communication of Europe’s central agenda setter. Press release output is also not proportional to the Commission’s legislative production. During Barroso’s second term, for example, the ratio of press releases to Commission proposals for binding European law was around seven to one. During Juncker’s term this ratio dropped to two to one. And, strikingly, the major declines in press release output occurred in periods that saw pronounced peaks of EU politicisation, for example, in the wake of the Eurocrisis, the Schengen crisis, or the Brexit debate. These observations raise doubts about whether the Commission’s supply of public information matches the growing societal demand.

However, more communication does not necessarily reflect better public information. More communication can also create political confusion (Adler and Drieschova Citation2021) or may blur, defuse, or even obfuscate political responsibilities (Moretti and Pestre Citation2015). It is thus not (only) the quantity but (also) the quality of the Commission’s outbound communication that matters.

5. The clarity of Commission messages in comparative perspective

As argued above, the most basic dimension distinguishing public account giving from technocratic discourse is language clarity as indicated by more accessible language, by less specialized jargon use, and by better clarification of what it is actually decided and done in Brussels. I thus extract three indicators from the original corpus of press releases that tap into each of these pathologies of technocratic discourse.

First, I measure language accessibility with the Flesch-Kincaid reading ease score (Flesch Citation1948; Kincaid et al. Citation1975). The intuition is that high grammatical and syntactic complexity increases the cognitive effort needed to decipher the message. The score combines sentence length (in words) and average word length (in syllables). It is often mapped onto the average text complexity demanded at different levels of the US education system. This absolute interpretation builds on student samples from the 1970s and is thus contested. However, it still holds in relative terms: reading ease scores show a substantial and robust positive association with how contemporary respondents assess the understandability of political texts (Benoit, Munger, and Spirling Citation2019).Footnote3

Second, jargon is a typical pathology of technocratic discourse. Jargon refers to highly specialized terminologies used only in narrow expert circles. Inversely, my measure for familiar vocabulary follows the intuition that words used more frequently in the English language more generally are better known to the average citizen, rendering a text easier to understand. To approximate average general word usage, I use the Google Books corpus (Michel et al. Citation2010) as the broadest accessible representation of the overall English language. From there I extract the average language frequency of the words that the Commission uses in its public press releases. The higher the value, the more common the word choice of the Commission is when compared to the overall English language. Here, I also build on the tools and validations offered by Benoit, Munger, and Spirling (Citation2019).Footnote4

Third, I want to learn whether the Commission clarifies what is actually decided and done politically, i.e. the action orientation of its political communication. Linguists measure the degree of agency a text expresses (or obfuscates) along its verbal (or nominal) style (Biber, Conrad, and Reppen Citation1998, 65 pp.). Texts focussing on human actions contain many verbs. Texts that focus on abstract and impersonalized objects, states, and processes, in contrast, contain many nouns. Everyday language is characterised by a verbal style, while a nominal style prevails especially in academic prose. Critical linguists and discourse analysts alike blame technocratic discourse particularly for promoting a nominal style and the frequent nominalisation of verbs (e.g. Fairclough Citation2003: Ch. 8; Fowler et al. Citation1979; Moretti and Pestre Citation2015, 89; Thibault Citation1991): such syntactic reductions condense information strongly, by removing grammatical subjects and temporal order contained in verbal constructions. They thus blur rather than clarify political action and choice. Following these arguments, I measure the verbal style of the Commission’s public communication by its verb-to-noun ratio.Footnote5

These indicators tell us whether the Commission increasingly uses its press releases for clarifying supranational politics also for the ordinary European citizens – or whether it remains stuck in its technocratic legacy. Yet, they are hard to interpret in absolute terms. A fair assessment on where the Commission’s communication is located between technocratic discourse and public account giving thus requires sensible benchmarks.

The most telling comparisons are press releases from national executives. Like the Commission, national governments and their departments draft, defend, and implement collectively binding rules. But unlike the Commission, national governments are more directly accountable to citizens as they must face them in regular elections. Being constrained by language and data availability, I focused on the governments of the United Kingdom and Ireland and scraped all official press releases from their different departments that are available in publicly accessible online archives. This generated a total of 92,070 full texts of national executive press releases published in the 2001–2021 period.

I furthermore collected data tapping into the extremes of expert- and public-oriented communication. Regarding expert-oriented language, I scraped 2,332 abstracts published in five top political science journals between 2013 and 2020. Like Commission press releases, political science abstracts condense complex political phenomena into short messages. Unlike press releases, however, they explicitly target a highly specialized expert community rather than the general public.

Contrasting the Commission’s communication to more public-oriented language, I focus on the politics sections of public print media, i.e. the kind of texts that should relay Commission messages to the public. Like the Commission’s press releases, also these outlets describe, summarise, and evaluate political decision-making. But unlike for Commission press releases, we can be sure that they are written to be accessible to the general public. I therefore extracted the random text samples from political sections of broadsheet and tabloid newspapers (57,765 and 22,160 paragraphs, respectively) provided in the British National Corpus (BNC Consortium Citation2007).

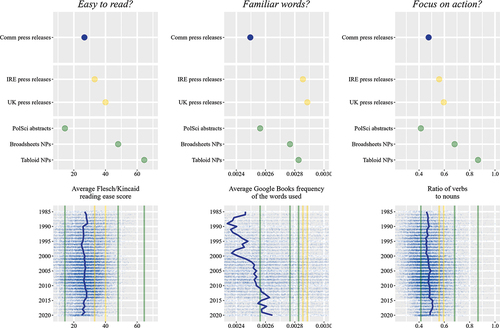

These encompassing corpora of political communication give us reasonable indicators and benchmarks to assess to what extent the Commission’s public communication is oriented towards reaching the general public. presents the comparative results.

The upper panel shows the aggregated mean values for our three language indicators across the different written registers of political communication. Communication from the Commission is consistently less clear than that of national executives. This initially holds in relative, statistical terms as judged by bootstrapped standard errors (too small to be visible here). But these differences are also substantial in absolute terms. For example, if we take the original reading ease scale at face value, the average press release from the UK government is about as demanding as high school texts. Commission’s press releases, in contrast, end up in the realm of text for university graduates.

In addition, the language that the Commission feeds into the public debate is significantly and substantially less accessible than the language that citizens usually experience when consuming political news from tabloid but also from broadsheet newspapers. In fact, the Commission’s public communication is consistently closer to the way that political scientists communicate with each other. Regarding the measure for familiar words as opposed to jargon, the Commission performs even worse than political scientists, on average. What the Commission feeds into the public debate, thus, is very different from the political language that European citizens usually encounter. The press releases from the Commission rather resemble specialized academic prose and require much more cognitive effort and background knowledge than the communication from national executives or political reporting in public media.

The annual averages of these indicators in the lower panel of highlight that this has hardly changed over time. Both, the reading ease and the indicator for verbal style actually stagnate over the 35 years of European integration observed here. Only the use of jargon decreased somewhat over time. Yet, this change is modest at best. The Commission’s communication has caught up with contemporary political science language, but its vocabulary is still much more specialized than that in national executives’ communication or public political news. In sum, press releases from the European Commission have been and are still located on the lower end of a scale between technocratic discourse and public account giving.

One may see these comparisons as unfair. As noted, some observers argue that member states have delegated primarily technical issues to the Commission. This may suggest that the Commission’s language is simply less clear because it communicates about issues that are more complex by some objective measure. While I doubt that complex policies cannot be communicated clearly as well, this view suggests that the observed mean differences are spurious and may solely hinge on the fact that national and supranational communication covers different topics.

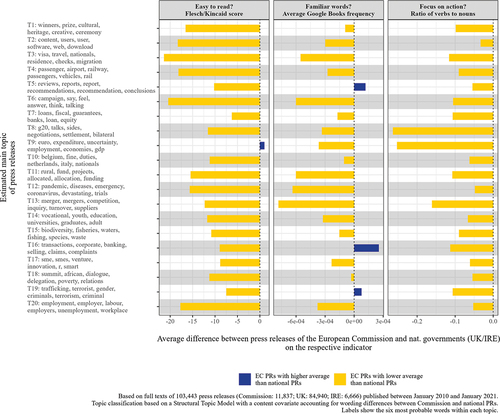

To control this, I follow the text matching intuition advanced by Roberts, Stewart, and Nielsen (Citation2020). I restrict the corpus of Commission press releases to the period for which I also have press releases from the UK and IRE governments and pooled the three data sets. On this joint corpus of 103,443 press releases, I then estimated a k = 20 structural topic model (Roberts et al. Citation2014) which accounts for possibly systematic differences in word choice between national and supranational texts (e.g. country names and ‘ministers’ as opposed to ‘European Union’ or ‘commissioners’ are unsurprisingly much more common in national messages, see Appendix B for detail). I am largely agnostic to the actual meaning of these ‘topics’ here. But the approach allows comparing message clarity of the Commission to that of national executives when both types of actors speak about similar themes as indicated by similar word clusters.

In a first step, I thus classified each individual press release with the topic that had the highest prevalence (the estimated theta parameter) given the words used therein. shows the respective mean differences between the Commission and national executives by this estimated main topic of individual press releases.

The message is clear. Even when focusing roughly on the same topics as national press releases, the Commission’s public communication is almost always less accessible. This holds no matter whether we look at language complexity, word familiarity, and particularly the expression of action. Four minor exemptions (of 60 comparisons in total) exist on individual topics and specific indicators, but these incidences are comparatively small, and they are clearly exceptions to the rule. On all other main topics and across the three indicators, the public communication of the Commission is much closer to technocratic discourse than national executive communication is.Footnote6

Still, the aggregate picture might be skewed by the overall distribution of topics beyond the main one in the communication of both types of actors. In a second step, I thus applied the topical inverse regression matching approach (TIRM) suggested by Roberts, Stewart, and Nielsen (Citation2020: esp. pp. 891–3). Along coarsened exact matching, this constructs a population of documents in which the overall distribution of all 20 estimated topics within the texts is equal and independent of whether they have been written by national or Commission officials. The resulting sample is notably smaller (82,132 press releases), suggesting that the distribution of topics indeed differs between national and supranational executive communication. Nevertheless, this balanced sample replicates the key finding (Appendix B): even if varying topic distributions are accounted for, the Commission’s communication performs worse on all three clarity indicators. These differences are statistically very robust and equal the absolute differences found in the larger sample above. The patterns uncovered here are thus not driven by somehow inherently more complex topics – they rather reflect the Commission’s generally more technocratic style of communicating to the European public.

6. Conclusions

Judged along almost 45,000 press releases and benchmarked against large samples of expert- and citizen-oriented texts, the public communication of the European Commission must be qualified as highly technocratic. The Commission’s public communication is characterised by grammatically complex language, by specialized jargon, and by an unusually nominal style that gives preference to abstract process over temporally identifiable courses of action. Strikingly, this has hardly changed over the more than 35 years of European integration observed here – a period in which the Commission’s political competences but also its politicisation in public debates grew markedly. These findings thus re-enforce pathologies of technocratic communication that were also detected in the Commission’s public speeches (Pansardi and Tortola Citation2021) or its social media posts (Özdemir and Rauh Citation2022). This also adds to different recent findings suggesting that especially the proponents of the liberal order beyond the nation state fail to send clear political signals to the wider public (Bischof and Senninger Citation2018; De Wilde Citation2020; Schoonvelde et al. Citation2019).

The technocratic style of communication that the Commission cultivates is probably well suited to address its traditional and highly specialized stakeholders in the Council, the European Parliament, or sectoral interest groups. But it is questionable whether it suffices in a context in which public opinion on the EU polarises, seizable shares of European citizens vote for Eurosceptic parties, and different domestic politicians blame Europe for policy failures. In this context, the Commission's technocratic style of communication is at least a missed chance: it reduces the likelihood that journalist conveys the message, it leaves room for interpretation and framing to other actors, and it decreases the chance that citizens will understand how the Commission uses its political powers. Technocratic communication thus plays all too easily into the hands of those who want to construct the image of a Brussels elite that is detached from the European citizen.

The literature as well as direct conversations with Commission officials and Brussels’ journalists suggest three possible explanations that future research should explore. First, the Commission’s communication may be related to deeply rooted organisational identities and self-reassurance in a politicized context (von Billerbeck Citation2020). Second, the Commission’s complex outbound communication may also be a function of bureaucratic infighting and consensus-seeking across different interests and policy stances within the organisation itself (Hartlapp, Metz, and Rauh Citation2014: Ch. 9; Meyer Citation1999; Rauh Citation2016). And third, complex communication may indicate strategic caution and institutional risk management, especially in contexts of pronounced conflicts in the Council of Ministers or the wider public (Van der Veer and Haverland Citation2018). Deliberately obfuscating political stances would then be an attempt to defuse controversial debates (Rauh, Bes, and Schoonvelde Citation2020; Schimmelfennig Citation2020). The data and methods offered here can assist testing these explanations in more targeted research designs, e.g. by tracking and contextualising variation within policy areas over time or by comparing the communication of the Commission to that of other EU institutions.

Thus far, however, the arguments and aggregate results presented here suggest that the Commission’s outbound communication has not adapted to the increasingly politicized public debates on multi-level governance in the European Union.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (344.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Earlier versions have been presented at the Global Governance colloquium of the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre, at the DVPW IB Sektionstagung 2020, the ‘Connected_Politics’ seminar (University College Dublin, October 2020), the workshop ‘(Self-) Legitimation of International Organizations in Disruptive Times’ (GIGA Hamburg, December 2020), and the International Studies Association (March 2021). I am very grateful for the constructive feedback from these audiences and benefitted furthermore from comments by Mathias Beermann, Pieter De Wilde, Christian Kreuder-Sonnen, Niklas Krösche, Bernd Schlipphak, Henning Schmidtke, and Laura Shields. I am also indebted to Serra Erkenci for her assistance in identifying and scraping the national press releases.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2022.2134860

Data Availability Statement

A full replication package- including the text corpora as well as the R scripts for collecting press releases and reproducing the reported results - is provided permanently via the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UGGXUF. The readme file in this archive provides further detail on replication.

Notes

1. Legislative proposals for directives, regulations, and decisions (excluding amendments). Count data based on information scraped from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/statistics/legal-acts/1990/commission-proposals-statistics-by-type-of-act.html (accessed: 24 April 2020).

2. The scraper harvests the results of a manually invoked search for document type ‘Press releases’, author ‘European Commission’ since 1985 in the EU’s RAPID data base (http://europa.eu/rapid/search.htm, scraped on 17 May 2019). In between, the Commission has revamped its archive, now called ‘Press Corner’, from which all remaining documents have been scraped (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/advancedsearch/en; 8 January 2021) This returns the population of all ‘information-presse’ (IP) documents available in the Commission’s archives (see Appendix A for more detail). The full machine-readable corpus together with all scripts replicating the subsequent analyses is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UGGXUF

3. The linguistic literature offers numerous alternative reading ease scores such the Gunning fog formula, Dale-Chall, Lix, or SMOG. However, I stick with the Flesch/Kincaid score for three reasons. First, virtually all alternatives are also weighted indices of word and sentence lengths (with differences in weighing and measuring word length). Second, the Flesh formula shows the highest correlation with comprehension in school reading tests when compared to the other alternatives (DuBay Citation2007). And most importantly, it has been recently validated for understandability of decidedly political text snippets (Benoit, Munger, and Spirling Citation2019).

4. To account for possible long-term changes in the English language, the approach matches each document to the Google Books corpus of the decade in which it was issued. Given a highly skewed distribution, word frequencies are expressed relative to the most common English word ‘the’.

5. Calculated as f(Verbs)/(f(Nouns)+f(Verbs)). Part-of-speech tagging relies on the spacy language models (Honnibal and Montani Citation2020) via the respective R wrapper (Benoit and Matsuo Citation2020).

6. While caution is warranted when interpreting these inductively generated topics substantively, the figure provides some hints that these differences in message clarity persists also in areas that were strongly politicized in a European integration context. For example, the most probably words for topic 3 are ‘visa’, ‘travel’, ‘nationals’, ‘Schengen’, ‘residence’, and ‘migration’ thus pointing to migration policy. As another example, Topic 12 is denoted by ‘pandemic’, ‘diseases’, ‘emergency’, ‘coronavirus’, ‘trials’ thus potentially marking press release related to COVID-19. But also in these potentially salient issue areas, Commission communication is significantly harder to understand than that of national executives.

References

- Adler, E., and A. Drieschova. 2021. “The Epistemological Challenge of Truth Subversion to the Liberal International Order.” International Organization 75 (S2): 359–410. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000533.

- Bartolini, S. 2006. “Should the Union Be “Politicised”? Prospects and Risks.” Notre Europe, Policy Paper 19.

- Benoit, K., and A. Matsuo. 2020. “Spacyr: Wrapper to the ‘Spacy’ ‘NLP.” Library. R package version 1.2.1, 2020.

- Benoit, K., K. Munger, and A. Spirling. 2019. “Measuring and Explaining Political Sophistication through Textual Complexity.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (2): 491–508. doi:10.1111/ajps.12423.

- Bes, B. J. 2017. “Europe’s Executive in Stormy Weather: How Does Politicization Affect Commission Officials’ Attitudes?” Comparative European Politics 15 (4): 533–556. doi:10.1057/s41295-016-0003-8.

- Biber, D., S. Conrad, and R. Reppen. 1998. Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Biesenbender, J. 2011. “The Dynamics of Treaty Change - Measuring the Distribution of Power in the European Union.” European Integration Online Papers (Eiop) 15 (5): 1–24.

- Bischof, D., and R. Senninger. 2018. “Simple Politics for the People? Complexity in Campaign Messages and Political Knowledge.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 473–495. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12235.

- Bischof, D., and R. Senninger. How Simple Messages Affect Voters’ Knowledge and Their Perceptions of Politicians - Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey Experiment. 2022. OSF Preprint. doi:10.31219/osf.io/cgz4k.

- Blom-Hansen, J., and R. Senninger. 2021. “The Commission in EU Policy Preparation.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (3): 625–642.

- BNC Consortium (2007) British National Corpus, XML edition, 6 March 2007, available at https://ota.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repository/xmlui/handle/20.500.12024/2554 (accessed March 2021).

- Boomgaarden, H., R. Vliegenthart, C. De Vreese, and A. Schuck. 2010. “News on the Move: Exogenous Events and News Coverage of the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (4): 506–526. doi:10.1080/13501761003673294.

- Boranbay-Akan, S., T. König, and M. Osnabrügge. 2017. “The Imperfect agenda-setter: Why Do Legislative Proposals Fail in the EU decision-making Process?” European Union Politics 18 (2): 168–187. doi:10.1177/1465116516674338.

- Bovens, M. 2007. “Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework.” European Law Journal 13 (4): 447–468. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Brüggemann, M. 2008. Europäische Öffentlichkeit durch Öffentlichkeitsarbeit?: Die Informationspolitik der Europäischen Kommission. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91058-1.

- Christiansen, T. 1997. “Tensions of European Governance: Politicized Bureaucracy and Multiple Accountability in the European Commission.” Journal of European Public Policy 4 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1080/135017697344244.

- Christiansen, T. 2016. “After the Spitzenkandidaten: Fundamental Change in the EU’s Political System?” West European Politics 39 (5): 992–1010. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1184414.

- De Bruycker, I. 2017. “Politicization and the Public Interest: When Do the Elites in Brussels Address Public Interests in EU Policy Debates?” European Union Politics 18 (4): 603–619. doi:10.1177/1465116517715525.

- Dellmuth, L. M., and J. Tallberg. 2021. “Elite Communication and the Popular Legitimacy of International Organizations.” British Journal of Political Science 51 (3): 1292–1313. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000620.

- De Wilde, P. 2011. “No Polity for Old Politics? A Framework for Analyzing the Politicization of European Integration.” Journal of European Integration 33 (5): 559–575. doi:10.1080/07036337.2010.546849.

- De Wilde, P. 2020. “The Quality of Representative Claims: Uncovering a Weakness in the Defense of the Liberal World Order.” Political Studies 68 (2): 271–292. doi:10.1177/0032321719845199.

- De Wilde, P., and M. Zürn. 2012. “Can the Politicization of European Integration Be Reversed?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (S1): 137–153.

- Directorate-General for Communication (2018) Media use in the European Union: report, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, available at https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2775/116707 (accessed January 2022).

- Dolezal, M., S. Hutter, and R. Becker. 2016. “Protesting European Integration: Politicisation from Below?” In Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics, edited by S. Hutter, E. Grande, and H. Kriesi, 112–134. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Down, I., and C. Wilson. 2008. “From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus: A Polarizing Union?” Acta Politica 43 (1): 26–49. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500206.

- DuBay, W. H. (2007) Smart Language: Readers, Readability, and the Grading of Text, available at https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED506403 (accessed July 2022).

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, M. 2018. “Self-legitimation in the Face of Politicization: Why International Organizations Centralized Public Communication.” The Review of International Organizations 13 (4): 519–546. doi:10.1007/s11558-017-9287-y.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. Basingstoke: Routledge.

- Featherstone, K. 1994. “Jean Monnet and the “Democratic Deficit” in the European Union.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 32 (2): 149–170.

- Ferrara, F. M., and S. Angino. 2021. “Does Clarity Make Central Banks More Engaging? Lessons from ECB Communications.” European Journal of Political Economy Online First.

- Flesch, R. 1948. “A New Readability Yardstick.” Journal of Applied Psychology 32 (3): 221–233. doi:10.1037/h0057532.

- Follesdal, A., and S. Hix. 2006. “Why There Is A Democratic Deficit in the EU: A Response to Majone and Moravcsik.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (3): 533–562.

- Fowler, R., B. Hodge, T. Trew, and G. Kress. 1979. Language and Control. London: Routledge.

- Gabel, M., and K. Scheve. 2007. “Estimating the Effect of Elite Communications on Public Opinion Using Instrumental Variables.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 1013–1028. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00294.x.

- Gerhards, J., A. Offerhaus, and J. Roose. 2009. Wer ist verantwortlich? Die Europäische Union, ihre Nationalstaaten und die massenmediale Attribution von Verantwortung für Erfolge und Misserfolge. Politische Vierteljahresschrift Sonderhefte Band 42 529–558. ‘Politik in der Mediendemokratie’

- Gleer, M., and C. H. de Vreese. 2005. “News about the EU Constitution: Journalistic Challenges and Media Portrayal of the European Union Constitution.” Journalism 6 (2): 221–242. doi:10.1177/1464884905051010.

- Gramberger, M. R. 1997. Die Öffentlichkeitsarbeit der Europäischen Kommission 1952 - 1996: PR zur Legitimation von Integration? 1st ed. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Gronau, J., and H. Schmidtke. 2016. “The Quest for Legitimacy in World Politics – International Institutions’ Legitimation Strategies.” Review of International Studies 42 (3): 535–557. doi:10.1017/S0260210515000492.

- Hartlapp, M., J. Metz, and C. Rauh. 2014. Which Policy for Europe?: Power and Conflict inside the European Commission. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heinkelmann‐Wild, T., and B. Zangl. 2019. “Multilevel Blame Games: Blame-shifting in the European Union.” Governance Online First.

- Hix, S. 1997. Executive Selection in the European Union: Does the Commission President Investiture Procedure Reduce the Democratic Deficit? European Integration Online Papers (Eiop) 1 21: available at http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/1997-021a.htm

- Hobolt, S. 2014. “A Vote for the President? the Role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament Elections.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (10): 1528–1540. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.941148.

- Honnibal, M., and I. Montani (2020) spaCy: Industrial-Strength Natural Language Processing, 18 March 2020, available at https://spacy.io/ (accessed March 2020).

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2001. Multi-Level Governance and European Integration. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- Hutter, S., and E. Grande. 2014. “Politicizing Europe in the National Electoral Arena: A Comparative Analysis of Five West European Countries, 1970–2010.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (5): 1002–1018. doi:10.1111/jcms.12133.

- Keohane, R., S. Macedo, and A. Moravcsik. 2009. “Democracy-Enhancing Multilateralism.” International Organization 63 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1017/S0020818309090018.

- Kincaid, J. P., R. Fishburne, R. Rogers, and B. Chissom. 1975. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. Memphis, TN: Naval Technical Training Command.

- Koopmans, R., and J. Erbe. 2004. “Towards a European Public Sphere?” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 17 (2): 97–118.

- and M. Lindholm. 2008. “A Community Text Pattern in the European Commission Press Release? A Generic and Genetic View.” Pragmatics 18 (1): 33–58. doi:10.1075/prag.18.1.03lin.

- Lorenz, H. 2017. “News Wholesalers as Churnalists?” Digital Journalism 5 (8): 947–964. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1343649.

- Majone, G. 2002. “The European Commission: The Limits of Centralization and the Perils of Parliamentarization.” Governance 15 (3): 375–392. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.00193.

- Majone, G. 2005. Dilemmas of European Integration: The Ambiguities and Pitfalls of Integration by Stealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mancini, P., Allern, S., Baisnée, O., Balčytienė, A., Hahn, O., Lazar, M., Raudsaar, M., et al. 2007. Context, News Values and Relationships with Sources - Three Factors Determining Professional Practices of Media Reporting on European Matters AIM Research Consortium, ed. Reporting and Managing European News: Final Report of the Project ‘Adequate Information Management in Europe’, 2004-2007, Bochum/Freiburg: Projekt Verlag, 117–154. https://www.vdu.lt/cris/handle/20.500.12259/46557

- Meyer, C. 1999. “Political Legitimacy and the Invisibility of Politics: Exploring the European Union’s Communication Deficit.” Journal of Common Market Studies 37 (4): 617–639. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00199.

- Meyer, C. 2002. “Europäische Öffentlichkeit als Kontrollsphäre: Die Europäische Kommission.” In die Medien und politische Verantwortung. Berlin: Vistas.

- Meyer, C. 2009. “Does European Union Politics Become Mediatized? the Case of the European Commission.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (7): 1047–1064. doi:10.1080/13501760903226849.

- Michel, J., Y K. Shen, A P. Aiden, A. Veres, M K. Gray, J P. Pickett, D. Hoiberg, et al. 2010. “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books.” Science 331 (6014): 176–182. DOI:10.1126/science.1199644.

- Moravcsik, A. 1998. The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Moretti, F., and D. Pestre. 2015. “Bankspeak: The Language of World Bank Reports.” The New Left Review 92: 75–99.

- Neuner, F. G. (2018) Elite Framing and the Legitimacy of Global Governance. Ph.D. dissertation. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University of Michigan.

- Özdemir, S. F., and C. Rauh. 2022. “A Bird’s Eye View: Supranational EU Actors on Twitter.” Politics and Governance 10 (1): 133–145. doi:10.17645/pag.v10i1.4686.

- Pansardi, P., and P. D. Tortola. 2021. “A “More Political” Commission? Reassessing EC Politicization through Language.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies Online First.

- Pollack, M. 1997. “Delegation, Agency, and Agenda Setting in the European Community.” International Organization 51 (1): 99–134. doi:10.1162/002081897550311.

- Princen, S. 2009. Agenda-Setting in the European Union. Houndmills: Palgrave.

- Raeymaeckers, K., L. Cosijn, and A. Deprez. 2007. “Reporting the European Union.” Journalism Practice 1 (1): 102–119. doi:10.1080/17512780601078894.

- Rauh, C. 2016. A Responsive Technocracy? EU Politicisation and the Consumer Policies of the European Commission. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

- Rauh, C. 2021a. “Between neo-functionalist Optimism and post-functionalist Pessimism: Integrating Politicisation into Integration Theory.” Theorising the Crises of the European Union. edited by N. Brack and S. Gürkan, available at 119–137.Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Theorising-the-Crises-of-the-European-Union/Brack-Gurkan/p/book/9780367431402.

- Rauh, C. 2021b. “One agenda-setter or many? The varying success of policy initiatives by individual Directorates-General of the European Commission 1994-2016.” European Union Politics 22 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1177/1465116520961467.

- Rauh, C., B. J. Bes, and M. Schoonvelde. 2020. “Undermining, Defusing, or Defending European Integration? Assessing Public Communication of European Executives in Times of EU Politicization.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (2): 397–423. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12350.

- Roberts, M. E., B. M. Stewart, and R. A. Nielsen. 2020. “Adjusting for Confounding with Text Matching.” American Journal of Political Science 64 (4): 887–903. doi:10.1111/ajps.12526.

- Roberts, M., B M. Stewart, D. Tingley, C. Lucas, J. Leder‐Luis, S K. Gadarian, B. Albertson, et al. 2014. “Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Responses.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 1064–1082. DOI:10.1111/ajps.12103.

- Ross, G. 1995. Jacques Delors and European Integration. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, F. 2020. “Politicisation Management in the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (3): 342–361. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1712458.

- Schmidtke, H. 2019. “Elite Legitimation and Delegitimation of International Organizations in the Media: Patterns and Explanations.” The Review of International Organizations 14 (4): 633–659. doi:10.1007/s11558-018-9320-9.

- Schoonvelde, M., A. Brosius, G. Schumacher, and B. N. Bakker. 2019. “Liberals Lecture, Conservatives Communicate: Analyzing Complexity and Ideology in 381,609 Political Speeches.” PLoS ONE 14 (2): [e208450]. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208450.

- Statham, P. 2008. “Making Europe News.” Journalism 9 (4): 398–422. doi:10.1177/1464884908091292.

- Steenbergen, M. R., E. E. Edwards, and C. E. de Vries. 2007. “Who’s Cueing Whom?: Mass-Elite Linkages and the Future of European Integration.” European Union Politics 8 (1): 13–35. doi:10.1177/1465116507073284.

- Tallberg, J., and M. Zürn. 2019. “The Legitimacy and Legitimation of International Organizations: Introduction and Framework.” The Review of International Organizations 14 (4): 581–606. doi:10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7.

- Terzis, G., and G. Harding. 2014. “Foreign Correspondents in Belgium Brussels Correspondents’ Struggle to Make the Important Interesting.“ In Mapping Foreign Correspondence in Europe, edited by G. Terzis, 19-36. New York: Routledge.

- Thibault, P. J. 1991. “Grammar, Technocracy, and the Noun.” In Functional and Systemic Linguistics: Approaches and Uses, edited by E. Ventola, 281–306. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Trenz, H. 2008. “Understanding Media Impact on European Integration: Enhancing or Restricting the Scope of Legitimacy of the EU?” Journal of European Integration 30 (2): 291–309. doi:10.1080/07036330802005516.

- Tsakatika, M. 2005. “Claims to Legitimacy: The European Commission between Continuity and Change.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 43 (1): 193–220.

- Tsebelis, G., and G. Garrett. 2000. “Legislative Politics in the European Union.” European Union Politics 1 (1): 9–36. doi:10.1177/1465116500001001002.

- Uba, K., and F. Uggla. 2011. “Protest Actions against the European Union, 1992-2007.” West European Politics 34 (2): 384–393. doi:10.1080/01402382.2011.546581.

- Van der Veer, R. A., and M. Haverland. 2018. “Bread and Butter or Bread and Circuses? Politicisation and the European Commission in the European Semester.” European Union Politics 19 (3): 524–545. doi:10.1177/1465116518769753.

- von Billerbeck, S. 2020. “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall:” Self-Legitimation by International Organizations.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (1): 207–219. doi:10.1093/isq/sqz089.

- Wille, A. 2013. The Normalization of the European Commission: Politics and Bureaucracy in the EU Executive. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zürn, M., M. Binder, and M. Ehrhardt. 2012. “International Authority and Its Politicization.” International Theory 4 (1): 69–106. doi:10.1017/S1752971912000012.