ABSTRACT

Since the US financial meltdown in 2008 that sparked a Eurozone crisis, the European Union has introduced new financial market initiatives that were intended to advance integration, bring stability, and create shared prosperity for EU members. Innovations included Banking Union, Capital Markets Union, and the European Fund for Strategic Investments. We find, however, that tensions between supranationalization and retaining national control in institutional design diminished incentives for full participation, particularly among the EU’s East Central European members. Uneven levels of foreign bank ownership between East and West Europe, disparities in the depth of capital markets, and varying institutional capacity have often led Eastern member states to opt out. Paradoxically, initiatives intended to advance integration and overcome developmental inequalities have instead compounded national fragmentation and restricted pathways to catching up for some of the EU’s less prosperous members. Thus, European financial integration was stalled by design.

1. Introduction

Since the European debt and currency crisis that the European Union (EU) brought largely under control by 2013, the raft of EU institutional initiatives around banking and finance can be construed as innovations to the Single Financial Market. Reforms were intended to advance market integration, improve the quality of bank oversight, and enhance both economic stability and prospects for growth. We argue, however, that even as European authorities, along with EU member states, tried to deepen integration and spur new dynamism, they also institutionalized competing priorities between supranationalism on the one hand and national control over finance on the other. Tensions within the design of Banking Union (BU), Capital Markets Union (CMU) and the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) limited the incentives for full participation among some EU members, particularly those in East Central Europe (ECE). This is because of underlying structural differences between East and West Europe. Economic and power asymmetries were manifest in disparate foreign bank ownership levels, the depth of capital markets, the strength of institutions, and the availability of development and private finance, among other indicators. The result by 2022 was that a number of countries, especially in the East, had opted out of the new integrative instruments. Or, operating from within the new framework, Eastern countries chose themselves to use national prerogatives at the expense of greater integration.

We argue that the European Single Financial Market was ‘stalled by design’ in 2022 because even if the overarching intention of post-crisis reform was not necessarily to limit integration, the apparent contradictions within institutional innovations did reflect competing interests. Similar to Calomiris and Haber’s study, Fragile by Design (Calomiris and Haber Citation2014), in which different national banking systems struggle to balance adequate credit provision against financial stability, we find that competing and sometimes conflicting impulses found their way into European financial reforms. For example, Banking Union supranationalized bank oversight, but retained strong roles for national supervisors, rules, and discretion (Donnelly and Asimakopoulos Citation2020; Fromage Citation2022; Högenauer, Howarth, and Quaglia Citation2023). Capital Markets Union sought to make raising funds across borders easier, but its supervision remained at the national level making that difficult in practice (Brenner Citation2022). The European Fund for Strategic Investments was intended to reinvigorate investment after the crisis but favored those with already well-capitalized development banks and private financing capacity, to the detriment of newer member states without those resources (Bruszt, Piroska, and Medve-Bálint Citation2022). Reliance on national development banks’ cooperation with the European Investment Bank (EIB) to boost investment remained an institutional hallmark of the von der Leyen Commission’s European Green Deal, as well.

The institutionalization of supranational structures with enduring national power did not disincentivize participation only among East Central European countries, however. In fact, there were segments of West European financial sectors and economies more broadly that stood to lose from the integrative push following the financial crisis. Intensified competition among financial services firms of varying kinds, mutualized deposit insurance, lost regulatory and supervisory forbearance, and the reduced influence of governments on banks that might have resulted from reforms were all threats to the West European status quo (Epstein Citation2017; Massoc Citation2021, Citation2022; Högenauer, Howarth, and Quaglia Citation2023). However, the focus of this article is on ECE because of the relative lack of crosscutting cleavages with West European countries, as well as minimal within-country variation on these issues. Whereas in Italy, Germany, Austria and other West European countries there were competing within-country interests around the desirability of supranational bank supervision (Epstein and Rhodes Citation2016), unified capital markets, and the role of development banks, in ECE, there was mostly skepticism of, or lack of interest in, the most recent financial instruments of the EU. Overall, the developmental divide between East and West Europe simply remained too significant for ECE to avail itself of the power and resources offered by BU, CMU or EFSI.

Thus, our ultimate outcome of interest is the intensified peripheralization of East Central Europe. For those ECE countries in the Eurozone and thus necessarily in Banking Union (the Baltic States, Slovenia, Slovakia, and soon Croatia in the Eurozone and Bulgaria in the BU) high levels of foreign bank ownership together with BU created an authority-resources mismatch, particularly with regard to the new resolution framework and the non-existence of a pan-European deposit insurance scheme. For non-Eurozone countries in ECE (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Romania), opting out of Banking Union allowed these EU members to retain greater supervisory control and discretion (particularly over foreign owned banks) than if they had joined. However, the exact modalities of peripheralization in different ECE countries depended upon their historically and politically contingent interpretation of European constraints and consequent choices.

In order to examine the extent to which the EU has introduced new problems in European integration even as it sought to solve others, we analyze each of the three policy initiatives – BU, CMU and EFSI – through the lens of East–West access and incentives to participate or opt out. Core-periphery dynamics in European financial regulation have been analyzed by scholars in areas such as the Banking Union’s variable appeal across the EU (Spendzharova Citation2014; Mérő and Piroska Citation2016), the proposed deposit insurance scheme’s uneven impact (Asimakopoulos Citation2018) or the EFSI’s more favorable distributional effect in the West and South compared to the Eastern member states (Bruszt, Piroska, and Medve-Bálint Citation2022; Mertens and Thiemann Citation2022). Ours is the first analysis, however, to pull together all major elements of the EU’s Single Financial Market and demonstrate its skewed impact and uptake across the Union. We would not expect, and do not find, uniform responses in ECE. Rather, we observe that some countries have used tensions built into the Single Financial Market to justify their own financial nationalism (Poland and Hungary) or to ringfence resources within their national markets when possible. Others, however, have chosen to integrate more aggressively into global financial markets, bypassing EU institutions altogether (as in the Baltics).

We begin each section by specifying the contradictory impulses embedded in BU, CMU and EFSI, which revolved around creating more supranational authority versus retaining national control over finance. We then highlight the disincentives for Eastern participation, given existing developmental disparities and the mismatch between the Single Financial Market’s newest institutions and Eastern policy priorities. In response to these mismatches, East Central European countries have lobbied unsuccessfully for greater inclusion, opted out of full participation or have themselves used national prerogatives that counter the integrative intentions of the innovation in question. The unintended consequence of financial reforms in response to the crisis has been a continuation and even an accentuation of financial fragmentation along national lines, as well as restricted pathways to catching up for the EU’s Eastern members.

2. Banking Union’s contradictions: Supranational authority with national vetoes

European authorities and EU member states began planning Banking Union in earnest by 2012 as the financial crisis in Europe was spinning out of control and doubts about the euro’s sustainability mounted. Some of the key problems that a banking union was projected to address included national-level regulatory and supervisory forbearance of banks, costly taxpayer-funded bailouts, powerful home biases in lending, politically motivated lending by banks to their own sovereigns and therefore linked vulnerabilities between governments and banks (Véron Citation2015; Epstein Citation2017; Högenauer, Howarth, and Quaglia Citation2023; Donnelly Citation2018; Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016). From the outset, banking union aimed to shore up the euro more than anything else, and as such was focused much more on the Eurozone than on the EU as a whole (Mérő and Piroska Citation2018).

With its formal operation beginning in 2014, Banking Union began supranationalizing bank oversight by introducing the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), located within the European Central Bank (ECB). As such, the ECB became the sole bank licensing authority for the Eurozone, in theory limiting national forbearance and potentially also paving the way for transnationalized bank ownership. Although proponents of BU hoped for increased competition among financial services providers and greater efficiencies through consolidation (that not all banks would survive), the largest multinational banks also stood to benefit from centralized oversight rather than negotiating with each member state’s supervisory authorities separately (Véron Citation2015).

By 2022, however, BU had fallen short of those aims. Ongoing economic uncertainty stemming from Covid-19, protracted bank recapitalization following the crisis, economic deterioration following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, continuing large exposures of banks to their sovereign’s debt, national political impulses and a Single Rulebook that preserved national biases in definitions of capital and allowed ringfencing had left market integration stalled. Transnationalized bank ownership and the breaking down of nationally fragmented banking markets had not transpired, and in fact had reversed in countries such as Poland and Hungary where governments, sometimes at the behest of local bank managers, had intervened to domesticate bank ownership for half of the sector (Naczyk Citation2014, Citation2022; Mérő and Piroska Citation2016). In addition, the lack of mutualized deposit insurance and national vetoes on the uses of resolution funds through the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), including as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) became the SRM funding backstop, meant that effectively, sovereigns were still potentially fiscally responsible for failing banks headquartered in their markets. Fiscal fragility stemming from bank failure was a core feature of the 2011–12 Eurozone crisis that by 2022 remained unresolved (Donnelly and Asimakopoulos Citation2020; Asimakopoulos Citation2018; Rehm Citation2022).

Given the contradictions outlined above, ECE was not fully incentivized to participate in Banking Union. The main structural difference between East and West Europe that encouraged Eastern members to opt out if they had the choice (that is, if they were not Eurozone members, or not in ERM II) were disparate levels of foreign bank ownership. Where foreign bank ownership levels were high, states were incentivized to maintain supervisory and regulatory control over banks, especially to keep resources within their own economies and particularly during the pandemic.

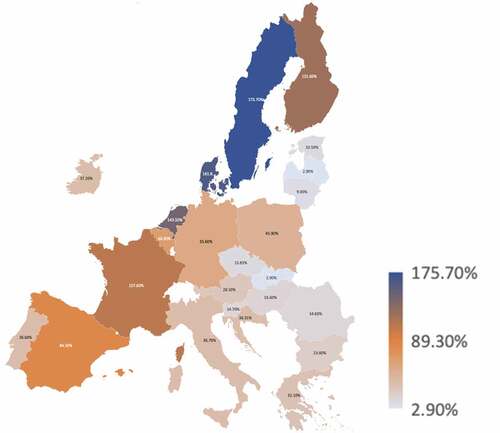

In most of Western Europe, and especially in the Eurozone’s four largest economies (Germany, France, Italy and Spain), foreign bank ownership levels remained low – by design. West European states had long viewed banks domiciled within their countries as critical to control over capital allocation, macroeconomic management, crisis response, sources of favorable credit, and instruments of power projection (Epstein Citation2014 and 2107; Massoc Citation2021, Citation2022). Unlike Eastern Europe during the postcommunist transition in the 1990s and 2000s that opened their banking markets to foreign investment, West European countries had been loath to give up national control, including over supervision, which only partially changed with Banking Union in 2014. Even given Poland and Hungary’s more recent insistence on achieving domestic control over half of their banking sectors, foreign bank ownership levels by 2017 were on average 67% for East Central European countries outside the Eurozone and 70% for those within (World Bank Citation2019, 9) (). By contrast, in Western Europe, foreign bank ownership levels were often below 20% or in the single digits, with the partial exceptions of Belgium, Luxembourg, Finland and Austria. But different from Eastern Europe, these countries achieved a balance of inward and outward investment, whereas most East Central European states were much more one-sided in their dependence on foreign investment.

Figure 1. Stock market capitalization as a percentage of GDP (As of Q4 2020) Source: “CEIC Leading Indicator”

Three features of BU elicited caution from ECE and also legitimated the call for reform from those that were part of BU by virtue of their Eurozone membership. The ‘small host’ problem, the desire among multinational banks and the ECB to ensure free flows of capital within financial groups, and the incomplete deposit insurance scheme all posed particular problems for ECE, whether the country in question was within or outside the Eurozone. Taken together, these features of BU threatened to decrease maneuverability for Eastern governments, regulators and central banks in directing and safeguarding their banking sectors. In sum, given disparate levels of foreign bank ownership between East and West, BU reinforced conflicts between multinational banks and European financial authorities on the one hand against East Central European hosts on the other.

The World Bank identified the first structural bias in BU as the ‘small host problem’ (World Bank Citation2019). A ‘small host’ in this case is a country in which multinational banks operate and these banks’ ‘subsidiaries are of systemic importance in the host country, but these foreign operations are not material for the parent bank and thus for the home country supervisory and resolution authority’ (p. 2). The small host problem pertains to both bank supervision as well as bank resolution, especially in times of crisis. They derive from asymmetries between the systemic importance of the subsidiary in the host country and the irrelevance of the host country operation for the overall functioning of the parent bank and thus the home supervisor. The smaller the host country, the more pronounced the asymmetry becomes. While small host problems are not unique to the EU, we find that the BU regulatory framework does little to alleviate the dilemmas of small and relatively poorer hosts in Eastern Europe.

The ‘small host’ issue also stems from path dependence in European banking markets. In some cases, the largest bank investors in ECE are also coming from relatively small, though extraordinarily wealthy, markets. A case in point in Austria, which had multiple multinational banking groups operating across the postcommunist world, in some instances for many decades. Although Austria itself is a small market (even if not as small as several Eastern states), it might still be the case that, given the overall scale of operations of any given banking group (Raiffeisen, for example), a single subsidiary in a small market does not create concern for the parent even if its financial health is in question. And yet that bank in the host country could generate substantial financial turmoil, given the smallness of the host market. Thus, it is not only market size in absolute terms that matters. Historical patterns of relative wealth and deprivation that allowed some countries to support their banks’ outward expansion (but not others) illustrates the economic inequality that authoritarian-minded leaders (particularly Viktor Orbán in Hungary) have argued justifies financial nationalism and sources of support outside the EU (Johnson and Barnes Citation2015; Camba and Epstein Citation2023).Footnote1

A second source of conflict that has incentivized ECE to opt out of Banking Union’s integrative intent was the desire among multinational banking groups, with the support of the ECB, to secure greater freedom to move capital and liquidity within their banking groups, at the expense of national authorities in host countries to harbor resources (ringfence) within their markets. A disagreement on this question emerged in 2020 as banks and supervisory and regulatory authorities were fashioning a response to the corona virus (European Systemic Risk Board Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Beck and Bruno Citation2022, 14–15). But in many ways, it was a replay of a similar conflict between ECE and multinational banking groups from 2008 to 2009, when regulatory measures in ECE effectively meant that ‘capital mobility in ECE was dead’, according to a West European banker at the time (Epstein Citation2017).

At issue in 2020 was the ECB’s recommendation that dividends, share buy-backs and other forms of remuneration to shareholders be restricted to make sure that banks were adequately capitalized given pandemic uncertainties. Although the European authorities as well as the European Banking Federation (EBF) preferred that these restrictions be implemented at the banking group level, a number of East Central European countries insisted that they be implemented at the national level instead. In other words, the ECB and EBF wanted banks to be able to move resources within their groups and across borders, whereas Eastern members wanted the resources to stay within their markets, restricting banks’ transfers out of their countries. ECE argued that given government funding to sustain economic activity through the pandemic, from which banks had gained, there was then no reason that subsidiary profits should be moved out of their economies during the crisis.

The dispute over bank-level versus national-level restrictions was significant because it showed the extent to which divisions existed along national lines, according to which countries had inward versus outward investment, that is, high versus low levels of foreign bank ownership in their markets. The dispute also clearly illustrated the ways in which some Eastern members were more concerned with safeguarding the health of national markets, even if the ECB (and ESRB) urged them to simultaneously be concerned with the strong functioning of the single market. In the event, it was ECE’s worry over their own national markets that prevailed, at the expense of Banking Union’s aim to break down national fragmentation. While BU was intended to limit or even eliminate national ringfencing of this kind, given the COVID-19 crisis, East European states nevertheless again reverted to a national approach. We must also point out, however, that ECE was not alone in displaying a national impulse. West European countries have on the whole been much less embracing of financial integration than the East, given their low tolerance of foreign takeovers in finance. Even if Ana Botín, President of the EBF and Chair of Santander, hoped for European resolution processes to make use of takeovers more forcefully,Footnote2 cross-national consolidation lagged in the West compared to the East.

Finally, although the lack of fully mutualized deposit insurance defeated a central purpose of BU for the whole of the EU by continuing to link state-bank financial fragility (Quaglia Citation2019), ECE again bore disproportionate risk. For countries within the Eurozone whose very small domestic financial markets were dominated by foreign-owned multinational banks, such as Slovakia, the Baltics states and since 2018 Slovenia when the country privatized large portions of the sector with foreign capital, the key problem these countries faced was a mismatch between supervisory powers, transferred to the ECB, and responsibilities for the consequences of supervisory decisions (Mérő and Piroska Citation2018). Supranational authorities were responsible for the supervision of their major banks, but national authorities might still bear the costs from ECB/SSM supervisory failures. At issue here was whether in a banking crisis the parent company would let a subsidiary go under. Subsidiaries, after all, can be let go by their parent banks without direct financial repercussions to the rest of the group (Epstein Citation2017, 65–66). Were this to happen, any gap between national deposit insurance and required resources to forestall insolvency would fall to the host government, which could put considerable financial strain on the host state. While such risks might appear to be low given the high reputational costs to a multinational banking group for letting a subsidiary fail, such risks are never zero.

This authority-resources mismatch was, of course, the case for all BU member states. However, it was more consequential for governments with small, open, foreign dominated banking sectors, especially in times of crisis. While they would enjoy the benefits of ECB’s liquidity creation and potentially the financial support of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the risk/responsibility mismatch was nevertheless larger for them. Meanwhile, their political power for advancing EU level reforms in this area remained limited. In the face of EU-wide non-action, ruling parties in Eurozone states have taken matters into their own hands. Slovakia, for example, argued for the prolongation of a bank levy citing the need to provide for financial stability (even if fiscal purposes also explained the levy). Implicitly acknowledging the fragile state of EDIS, the ECB welcomed the intended use of part of the collected funds for strengthening the Slovak Deposit Protection Fund and the Slovak Crisis Resolution Fund.Footnote3 The lack of mutualized deposit insurance explained further the reluctance among non-Eurozone members to cede any additional authority over bank oversight, and thus their reluctance to join BU. The Polish government, as another example, welcomed the initiative of the biggest commercial banks in Poland to create a protection scheme to help ensure their liquidity and solvency.Footnote4

As of June 2022, completing BU was effectively put on hold, although the Eurogroup agreed to more incremental processes.Footnote5 As was typically the case, one deadlock revolved around two large Eurozone states. Germany objected to EDIS while Italy rejected concentration charges on bank holdings of sovereign debt.Footnote6 While the literature focused on the preferences of various powerful actors behind the new proposals for EDIS, such as Germany, France, larger banks, and the ECB, there was little attention to the various proposals from small member states of the Eurozone and EU outside the Eurozone and Banking Union, who may nevertheless be positioned to eventually join both (Piroska, Gorelkina, and Johnson Citation2020).

Banking Union illustrated the paradoxical character of the Single Financial Market. Although BU enhanced supranationalism in significant ways, particularly through supervision as well as in some elements of standardized regulation and mutualized resolution, there were still many channels through which states could exercise national prerogatives and power. Tensions in banking union between supranationalism and national control alongside structural differences between many Western and Eastern economies, particularly in foreign bank ownership levels and imbalances in inward versus outward investment, limited the appeal of joining BU for those that were not compelled to. And for Eastern member states in the Eurozone, they experienced elevated risk from multinational banking groups and the absence of mutualized deposit insurance. Moreover, when given the opportunity, Eastern members, too, used national prerogatives to keep resources within their markets, even if that undermined capital mobility, bank efficiency, and the integrity of the single market according to the ECB and Europe’s largest banks.

3. Capital Markets Union and Eastern capital markets

CMU was launched in 2015 by the European Commission to supplement its effort to revitalize growth in the EU through the Junker Plan (Mertens and Thiemann Citation2017). As a complement to Banking Union, the launch of Capital Markets Union was intended to advance the EU’s Single Financial Market more broadly. Unlike BU, CMU pertained to the entire EU, not only the Eurozone. CMU was aimed at increasing the efficiency of savings allocation through harmonized and better developed capital markets. For the Commission, CMU’s key feature was investment promotion across Europe and was positioned to yield profit for both savers and investors through richer stock market options for SMEs. In addition to boosting investment, CMU also promised more effective crisis management that involved capital markets, not only banks, through a diversification of financial instruments (Sapir, Véron, and Wolff Citation2018). The ECB also supported CMU to restore its monetary steering capacity over the economy through capital markets when bank-based finance declines (Hübner Citation2016). In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, it seemed questionable to some whether these goals were best achieved through a push towards non-bank financial intermediation (Quaglia and Howarth Citation2018). Nevertheless, CMU received support in the highest European circles as the best solution to address these problems across the EU.

There is a growing literature detailing the origins of the Capital Markets Union, including its drivers and design (Endrejat and Thiemann Citation2019, Citation2020; Epstein and Rhodes Citation2018; Howarth and Quaglia Citation2021; Quaglia and Howarth Citation2018). In this section, we contribute to this literature by pointing out tensions in CMU’s supranational architecture, which achieves only limited harmonization of regulation in the market segments of investment firms and center counterparties, while leaving other market segments, namely insurance and pension, under national regulatory control (Brenner 2022). Moreover, even in the market segments where CMU promotes harmonized markets as it delegates supervisory powers to supranational bodies, the benefits of harmonization may be realized only by Western capital markets, which host most institutional investors and central counterparties, while Eastern market actors remain underserved by capital investors. The result is that CMU, instead of strengthening further capital markets integration across Europe, codifies national control to the detriment of supranational bodies and cross-border investment. This design stalls further integration as it disincentivizes some actors, in particular, Eastern member states, from fully supporting and participating in capital markets integration.

While CMU’s capacity to push European economic integration forward, increase growth, and stabilize European finance is stalled by design, it nevertheless legitimizes financial practices that also create imbalances within an emerging macro-financial regime (Braun, Gabor, and Hübner Citation2018). Marketization and securitization of finance have been associated with a number of negative consequences for social inequality, public provision of services, stability of finance, and democratic control over finance. Eastern member states with shallower capital markets are sheltered from many of these vulnerabilities. However, as CMU is the driving instrument of the EU Commission to boost growth, the Single Financial Market’s design becomes problematic for ECE as it does not increase available finance for them. However, Eastern member states’ responses to these conditions depend on their interpretation of these features that further defines their political actions. This also explains the diversity in national responses to CMU that we see across Eastern member states.

3.1. National control of capital market supervision

Since the launch of the CMU in 2015, key sectors in national capital markets remained predominantly under national regulatory control. CMU’s regulatory design sustained the status quo in the areas of pension funds, insurance funds, and investment funds, and built up only weak supranational structures for investment firms and central counterparties (Brenner 2022). Within the CMU framework, national supervisory control remained embedded in the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS), and in particular in the functioning of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) such as the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority (EIOPA), and European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA). In the case of the three ESAs, national control is exercised through National Competent Authorities (NCAs). ESAs are mandated to ensure the unification of regulation and supervision across European capital markets with a focus on micro-prudential risks. ESAs continuously update the single rule book, build a common supervisory culture that minimizes deviation in the implementation of the single rule book, delegate various tasks among NCAs, and peer-review NCAs’ practices to support supervisory consistency (Brenner 2022). ESAs also coordinate and share information with the European System Risk Board (ESRB), the macro-prudential regulator of the EU.

However, as Brenner (2022) points out, ESAs remain intergovernmental in their decision-making because their deliberation is informed by qualified majority voting, both in the case of technical standards (RTS) and their implementations (ITS). The European Commission’s capacity to turn ESAs’ technical guidance into binding regulation is constrained by its ability to do this only when such standards do not include policy choices or strategic decisions. As such, national control remains dominant, both in regulation and enforcement.

There is only one regulatory area in which the CMU framework established a stronger form of regulatory harmonization. In the case of central counterparties (CCPs), firms that provide cross-border clearance in the Eurozone for EU entities (Bulfone and Smolenska Citation2020), stronger harmonization is in place. Triggered by the ECB’s concerns about the consequences of Brexit dislocating major central counterparties dealing in euros outside the Eurozone, the European Commission advanced a new regulation on central counterparties in 2019 as part of the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) reform. However, even in this case of supervisory supranationalization, ESMA’s powers to supervise CCPs increased only in relation to those operating outside the EU (Hong Kong, Singapore, UK, and the US). At the same time, national authorities continue to retain supervisory powers over intra-EU CCPs (those headquartered in an EU member). As Bulfone and Smolenska (2020) argue, ‘this differentiated regime has emerged despite the fact that in its initial proposal the Commission, flanked by the ECB, had called for the establishment of a single supervisory framework for intra-EU and extra-EU CCPs.’ (p. 54.).

With continued national supervision in all other segments of capital markets (pension, insurance, and investment funds) CMU codifies a fragmented European market. Fragmentation continues to present administrative burdens for potential cross-border investors, which tend to seek opportunities in the better capitalized Western capital markets. Nothing in the current supervisory or regulatory structures encourages cross-border capital raising that would transcend the developmental divide between East and West Europe. Eastern capital markets remain underserved by equity investors due to a few key characteristics of their dependent market structures that we detail in the next section.

3.2. Dependent market economies

A common observation of the varieties of capitalism literature is that Eastern peripheral financial markets are bank-based. Local enterprises, which are mostly of small and medium size, seek financing in local bank subsidiaries of multinational banks (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012; Farkas Citation2016; Epstein Citation2017). Therefore, changes in capital markets – harmonized or otherwise – have no substantial impact on Eastern SMEs’ financing needs in the short to medium run. There is of course no denying the Eastern SMEs would benefit from access to more finance. Study after study reveals how important financial constraints are on the limited growth potential of Eastern SMEs (Bonin et al 2005; Nizaeva and Coskun Citation2019). However, a number of historical developments have contributed Eastern markets’ weak capitalization on an ongoing basis.

When it comes to dependent market economies in Eastern Europe, there is a documented lack of interest in Eastern stock markets from large corporations, both foreign and local (Nölke and Vliegenthart Citation2009). Although there are some domestic players of note in ECE, the fact that large corporations are mostly foreign owned has significantly diminished demand in capital market financing. Foreign owned corporations seek finance though their parent companies; their headquarters can more efficiently raise funding in Western capital markets than in host markets. Furthermore, although most large, locally owned corporations across Eastern Europe are listed on local stock exchanges, their financing through security issuing remains limited. They tend to prefer bank-based finance, retained earnings finance, or issue shares on the London Stock Exchange (see WizzAir).Footnote7 Low volumes of stock trading in Eastern markets make it difficult to attract private investors that would potentially fund SMEs.

CMU may, in theory, bring additional investment into these larger Eastern corporations. However, for that to materialize, harmonization of both national accounting and capital markets would be needed, and the former is not foreseen by the Commission. This is because even large (by Eastern standards) Eastern corporations demand comparatively small volumes of finance, which limits investor interest. The costs of investing are simply too high in light of likely returns which, in the larger scheme of things, are relatively small. This is even more true if investors face complicated national accounting standards, both at the level of the national stock exchange regulation, as well as at the level of national accounting standards of large corporations.

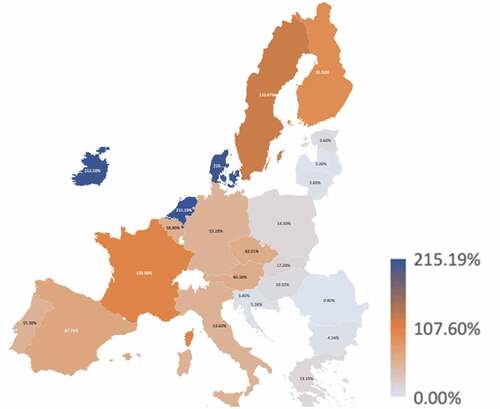

These two factors – little interest among SMEs in capital markets and small volumes of stock offerings by large corporations – result in remarkably low volumes of equities being traded in Eastern stock exchanges today. Because Eastern markets are so weakly capitalized, boosting their intermediation capacity is inadequate for increasing Eastern companies’ ability to access finance. shows the total market capitalization of listed companies across the EU. Market capitalization of a company refers to the value of that company’s shares of stock.Footnote8 Eastern stock markets offer much smaller opportunities for Eastern companies, to issue both shares and bonds, as a means of financing their business activities compared to Western stock markets ().

Figure 2. Corporate bond market capitalization as a percentage of GDP. Source:

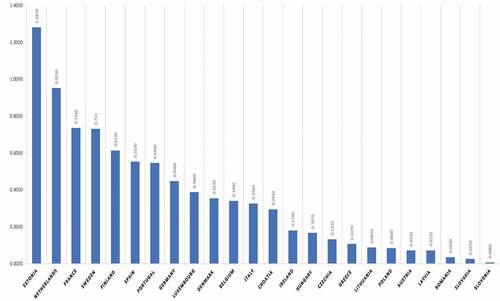

Figure 3. Private equity investment as a percentage of GDP, 2020.

3.3. Too few institutional investors in Eastern capital markets

There are two key sources of finance missing from East European economies that further explain the low capitalization of stock markets and portend a continuation of this trend. In ECE, there is (1) a very low extent to which pension funds invest in stocks, and (2) there are virtually no other domestic institutional investors. There are no provisions in the CMU action plan that would energize these markets leading to increases in local capitalization of stock exchanges. National control for these market segments remained firmly entrenched in the CMU legal framework.

The establishment of private pension funds in ECE has not been accompanied by a reform of the old pay-as-you-go systems (Orenstein Citation2005). Therefore, the capital-base of private pension funds remained limited. More recently, in ECE societies the personal responsibility for retaining an adequate pension increased and the volume of capital carried by private pension funds of Eastern Europe grew (Hassel, Naczyk, and Wiß Citation2019). Nevertheless, according to OECD studies, the degree of pension fund investment remained very low in the East compared to Western markets, though there is variability.Footnote9 Looking at the investment structure of private pension funds in ECE, the OECD finds that equity investment is very low: over 60% of total assets of private pension funds of the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Romania are in the form of bills and bonds. Further, in the Czech Republic, 20% of its private pension funds are in cash and deposits and only a small share is allocated to equities. It is only in Poland where a higher level of equity investment exists: over 80% of the assets of private pension funds are in equities, while only 20% of Romanian pension funds are.Footnote10

Except for Estonia, East European institutional investment (excluding pension funds) is negligible (). This is indeed striking, as private equity in ECE has had more than three decades of experience. Moreover, Eastern governments and the EBRD have been very active promoting it. Venture capital’s interest in Eastern Europe also remains low. Although this insight is missing from most recent analyses of the role of European structures, including from the European Investment Fund’s (EIF) efforts to steer investment (Cooiman Citation2021), it is nevertheless an important difference between East and West with consequences for the balance of private and public investment goals.

One explanation for the prevalence of low private equity investment volumes in Eastern markets is a national bias in most major investment forms in the EU. As we saw above, most major investors such as pension funds, insurance companies, and other investment funds remained under domestic supervisory control.

3.4. Uneven monetary policy through uneven capital markets

Capital Markets Union’s capacity to accelerate the transition from bank-based finance to market-based finance in Western Europe was one reason the European Central Bank (ECB) became an enthusiastic supporter of the Commission’s proposals. Hübner (Citation2016) convincingly argues that the key reason for the ECB’s enthusiasm for the CMU project was its expectation that it would be able to use more diverse monetary policy tools through more liquid capital markets to greater monetary policy effect. Due to the low interest rate environment of the post-GFC European economy, the ECB expected to regain influence through more similar, and thus better capitalized, financial markets to carry out its price stabilizing mandate (Hübner Citation2016).

However, it seems analysts at the ECB consistently overestimated the extent to which these expectations about more dynamic and diverse capital markets would materialize in Eastern Eurozone member states. Eastern member states such as the three Baltic states, Slovenia and Slovakia (with Croatia soon to join them) do not have, and will likely not develop, well-capitalized stock markets through which the ECB’s bond issuing/purchasing/selling programs can have significant effect on local money supply. The one-size-fits-all monetary policy again may have adverse effects on both Eastern and Western markets to the extent that CMU brings more diversity to economic conditions, rather than uniformity. This may further decrease non-Eurozone member states’ interest in joining the Eurozone.

3.5. Differentiated impact of CMU on Western and Eastern finance

CMU was proposed against the broader backdrop of changes in financial markets, in which short-term finance, including for banks, has introduced new sources of financial volatility (Braun, Gabor, and Hübner Citation2018; Hardie et al. Citation2013). Market-based banking in particular has different effects in Eastern versus Western Europe. As the literature argues, the transformation from bank-based to market-based banking invigorates capital markets, but is not without negative consequences, as well – especially in the form of volatility, with increased mismatches between short-term funds for banks being lent on longer-term contracts. CMU acts as a catalyst to these changes – potentially increasing the volatility of funding – but these uneven consequences are unaccounted for in the CMU design.

Since the 2000s, large multinational banks increasingly securitized both their assets and liabilities through stock markets resulting in the weakening of the distinction between bank-based and market-based finance (Hardie et al. Citation2013). Today, even more so than a decade ago, Hardie et al.’s (Citation2013) finding that in most developed Western economies, capital markets dominate obtains. Meanwhile, ‘patient’ or long-term sources of funding have become increasingly scarce. However, as demonstrated by Bethlendi and Mérő (Citation2020), the transformation of banks to stock market players through the securitization of their balance sheet is practically non-existent in Eastern Europe. Consequently, banks (mostly subsidiaries of large Western banks) do not appear on local capital markets, contributing to weak capitalization of Eastern markets in general. This is especially true for the securitization of mortgages, which is legally not prone to securitization in Eastern Europe (Bethlendi and Mérő Citation2020).

Marketization of finance is associated with a number of negative consequences for the economy. Hardie et al. (Citation2013) argued that through redefining the sources of credit, the time horizon of non-financial firms may be shortened, with implications for the organization of labor markets, welfare, education, innovation, and flexibility. Moreover, marketization of finance brings in new sources of volatility for the functioning of financial markets with herding, faster bubble formation, and hidden sources of financial risk through complex financial engineering (Braun, Gabor, and Hübner Citation2018). Through increased pressure to financialize everyday life, marketized finance has the potential to accelerate assetization of basic commodities, with housing playing a leading role (Birch and Muniesa Citation2020; Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2017). If financial crises are spawned by or result from crises in housing markets, negative social consequences can also follow, as was the case in the US financial crisis in 2008 and after.

A number of contradictions was evident from the depiction of CMU outlined above. CMU by 2022 was stalled by design in the sense that European institutions were paving the way for more cross-border capital raising while at the same time allowing national supervisory control of such processes. This limited CMU’s capacity to meaningfully diversify European sources of funding. At the same time, even before CMU was formally reintroduced as a policy priority in 2015, West European economies had already been undergoing a market-based transformation in which banks were no longer primarily dependent on local deposits for lending, relying increasingly on various kinds of capital markets to fund lending instead. While this increased the potential for volatility across the European economy, plans for CMU did nothing to address new vulnerabilities and could ultimately accentuate them. Finally, while Eastern bank-based markets were transitioning much more slowly or not at all to market-based finance, CMU’s neglect of ECE’s market specificities meant that while ECE might not suffer direct new vulnerabilities from CMU, CMU also provided very little to ECE in terms of new funding opportunities. And because of the realities of the East’s continued dependence on the West for capital, even if Eastern banks were not directly part of the market-based banking trend, the Western financial institutions on which they were dependent became vulnerable. Thus, the East would remain indirectly susceptible to volatility emanating from the West. The stalled design in turn incentivised Eastern regulators and businesses to seek solutions outside the EU regulatory framework, ranging from financial nationalism or exit to global financial markets.

4. Market-based investment and state-led development banking in Eastern Europe

CMU was initiated not only or even primarily as a supplement to Banking Union, but rather as an addition to the Junker Commission’s investment plan to boost growth and dynamism following the financial crisis. Aptly described by Mertens and Thiemann (Citation2018) as market-based but state-led, the Junker Plan’s new investment fund, the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), built on the collaboration of the European Investment Bank (EIB) and national development banks to deliver marketable investment projects that serve the interests of private financial investors across the whole EU, not only the Eurozone. As such, EFSI was predicated on the expectation that through capital markets harmonization, global private investors could be mobilized to invest in European development projects, designed with different risk-return profiles to accommodate investors’ demand. As such, EFSI complemented the BU and CMU-defined European Single Financial Market for private financial investors.

The von der Leyen Commission’s European Green Deal (EGD)’s investment plan, the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP), and its attached Just Transition Mechanism (JTM), follow the model of the Junker Plan’s EFSI with regard to their reliance on the EIB and national development banks. Introduced in 2020, SEIP was more ambitious than EFSI, insofar as its goal was to catalyze EUR 1 trillion of private investment dedicated to European projects. The EGD was also a correction to the Junker Plan, with more technical assistance to member states in creating investment pipelines.

Key elements of EFSI and SEIP tend to stall integration across the EU rather than furthering it, however, through theoretically deeper and more harmonized financial markets. Recently, Bruszt, Piroska, and Medve-Bálint (Citation2022) and Mertens and Thiemann (Citation2022) have highlighted the core-periphery dynamics of EFSI that we review here in order to pinpoint the sources of unevenness in Western and Eastern business access to finance within the EFSI-defined regulatory structure. We would expect to find similar disparities in the functioning of the SEIP in the near future. As in both Banking Union and Capital Markets Union, the EU’s new investment vehicles do not accommodate Eastern financial market conditions or less robust public funding institutions compared to the West. Thus, in development finance, we also find incentives for Eastern regulators to opt out, stalling further integration and East-West convergence.

First, in the EFSI framework, national development banks (NDBs) play a central role. They not only channel member states’ pledges to EFSI, but also design and implement investments in relation to EFSI. It is therefore not surprising that ‘the countries with the highest EFSI uptake were those with the most developed and active National Promotional Banks and Institutions.’Footnote11 This suggests that countries where development banks have less capacity and that manage smaller funds were, per EFSI design, less able to attract, not only European funding designated to remedy economic disparities, but also private finance, which is contingent on public funding. Development banks in the West have a long tradition going back to the 1980s of financing their operations through capital raised in stock markets (Naqvi, Henow, and Chang Citation2018). Accessing stock markets for raising funds at competitive rates is not a given for Eastern development banks, however, stemming from their limited administrative capacity. Moreover, their governments’ lower ratings on international markets as well as the lower capitalization of their own domestic stock markets hinder their capacity to raise funds. Although all EU members had equal access to EFSI funding, in fact wealthier countries with deep capital markets and prodigiously funded national development banks had a distinct funding advantage vis-à-vis public sources (Piroska and Mérő Citation2021).

Second, the EFSI Global Multiplier Effect of 15x favored projects in Western member states. The global multiplier was the ratio between EFSI-provided public funds and private investment. EFSI funds were only 1/15 of the total investment. As this multiplier was set very high, it means that EFSI funding was only available for projects that can attract private financing of this magnitude. A high multiplier directed EFSI investment to Western and Southern member states for three reasons: (1) financing abounds in core and even Southern countries compared to in Eastern member states; (2) private finance prefers less risky investments, which are again to be found in higher numbers in older EU members rather than in the Eastern periphery; and (3) thinner capital markets in the East make financing smaller Eastern projects less attractive for private investors.

Moreover, a new instrument developed by EFSI and national development banks, the Investment Platform, did not live up to its potential in Eastern member states (Bruszt, Piroska, and Medve-Bálint Citation2022). In principle, the Investment Platform should suit the financing of smaller or riskier projects because of its capacity to combine funding from several sources and optimize the allocation of risk between various investors. But according to the EFSI audit report, Investment Platforms developed slowly. Only one in Italy in the whole EU was created by the end of 2016, and only 35 by the end of 2017. Moreover, most of these Investment Platforms were located in France, Italy, Germany, and Spain, countries with already highly active and well-established national development banks. These countries accounted for the most significant volume of EFSI financing and the highest number of operations.Footnote12

Fourth and finally, although EFSI was created to supplement existing EU transfers aimed at market-correcting and investment boosting, due to EFSI’s distinctive rules compared to other EU instruments or that of national developmental funds, combining different sources of funding posed additional administrative burdens for member states (Nyikos et al. Citation2020). Because of the highly bureaucratic nature of EFSI financing, member states’ capacity to write fundable projects also determined their capability for securing EFSI approvals. These capacities were less available in Eastern member states than in the West. This was the case despite the availability of EFSI advisory services aimed at building up project preparation capacity along technical dimensions.

In sum, legal and procedural features of EFSI created relatively propitious lending conditions in Western and Southern member states, but disregarded the different institutional and private financial market conditions in Eastern Europe. While the SEIP’s additional technical assistance may have increased ECE administrative capacity, low degrees of securitization, shallow capital markets, and underfunded national development banks in ECE would continue to make it difficult for businesses in the Eastern periphery to avail themselves of EFSI resources.

5. Conclusions

This article outlined the uneven distributional consequences of reforms to the EU’s Single Financial Market since the Global Financial Crisis. Our focus concerned the EU’s banking and financial regulatory framework that affected the flow of capital as well as decision-making power across the Union. Reviewing Banking Union, Capital Markets Union, and the European Fund for Strategic Investments, we highlighted the dominance of Western interests in institutional design, which omitted consideration of Eastern financial market features. We have also detailed the contradictory nature of those designs, in which there was simultaneously a push for greater supranational authority alongside continuing national power.

The EU’s Single Financial Market, through omission of Eastern financial market specificities such as high levels of foreign bank ownership, weakly capitalized stock markets, and underfunded national development banks, did not increase the East’s private sector access to financial flows. Moreover, it incentivized the ringfencing of financial resources within Eastern markets, to the detriment of free capital flows, bank efficiency and the smooth functioning of the single market. Understandably, Eastern regulators, given the paradoxical nature of the single market’s institutional design and power asymmetries between East and West, sought to maintain national control when they could in order to insure themselves against financial instability as best they could – a position that was fully allowable under the newest rules. But the set of institutions under consideration here also created political incentives to seek funding opportunities outside EU markets. As such, the EU’s Single Financial Market failed to serve an enfranchising role for Eastern member states, which compounded fragmentation within the EU, rather than transcending it.

Eastern regulators, central bankers, and politicians interpreted European regulatory constraints differently, depending on their own national political discourses conditioned by historical and socio-economic experiences. Their agency in defining various accommodating strategies was also on display. We find a variety of regulatory and policy responses in the Eastern periphery, ranging from reasserted state control and cronyism (Hungary) to technocratic challenges to the EU’s one-size-fits-all policies in professional forums (Czechia) to technology-led marketization towards digital solutions for financial intermediation (in the Baltics). The Hungarian government’s responses were at one end of a nationalizing spectrum. Hungary domesticated bank ownership, politicized the central bank and invested it with broader powers, and pursued large-scale investment projects financed by Russia (including the Paks nuclear plant) and by China (for example, the Budapest-Belgrade railway line, the final étap of China’s Belt and Road Initiative). None was helpful to the EU integrative agenda. The Estonian and other Baltic governments, meanwhile, were building large fintech ecosystems to attract investors into digital financial services that were designed to circumvent the EU’s existing regulatory structures and priorities (e.g. Revolut). Though not nationalistic in a traditional sense, these developments increased potential volatility and instability in Baltic financial markets, but also in Europe more broadly.

By 2022, the EU’s Single Financial Market was stalled by design in the sense that although there had been a push during the most dangerous years of the European financial crisis to unify banking and capital markets, as well as to pursue new opportunities for growth and innovation, tensions between supranational empowerment and national control prevented deeper integration. These competing impulses had special implications for ECE because of ongoing structural inequalities between East and West Europe. Paradoxically, the EU’s post-crisis reforms created new problems of uneven access and inequality, even as it sought to solve others around bank oversight and availability of finance.

Acknowledgement

Dora Piroska would like to acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Jack Lambert Strosser.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. See also Marton Dunai, ‘The Bank of Viktor Orbán,’ Financial Times, 31 May 2022, p. 19.

2. See the interview with Ana Botín, ‘The banks are not complacent,’16 February 2022 from the ECB/Banking Supervision newsletter, available at: ‘The banks are not complacent’ (europa.eu). Accessed 20 June 2022. In the interview, she says that ‘we need to focus more on the sale of banks to sound players as part of the resolution process’ and that ‘the regulatory landscape significantly limits the benefits that large-scale cross-border consolidation could offer’ in reference to national prerogatives.

3. https://www.moodysanalytics.com/regulatory-news/Nov-04-20-ECB-Opines-on-Abolition-of-Special-Levy-on-Certain-Banks-in-Slovakia accessed at 27 October 2022.

4. https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/polish-banks-team-up-create-protection-scheme-2022-06-08/ accessed at 27 October 2022.

5. See the ‘Eurogroup statement on the future of the Banking Union as of 16 June 2022’: Eurogroup statement on the future of the Banking Union of 16 June 2022 – Consilium (europa.eu), accessed 28 June 2022.

6. Paola Tamma and Bjarke Smith-Meyer, ‘Finance ministers put banking union plans on ice,’ PoliticoPro, 16 June 2022: Eurogroup statement on the future of the Banking Union of 16 June 2022 – Consilium (europa.eu), accessed 28 June 2022.

7. https://www.lseg.com/markets-products-and-services/our-markets/london-stock-exchange/equities-markets/raising-equity-finance/market-open-ceremony/welcome-stories/london-stock-exchange-today-welcomed-wizz-air-holdings-plc. Accessed 27 October 2022.

8. Total market capitalization of a stock exchanges thus shows the extent (the total amount of finance available for companies) to which a stock exchange can operate as a financial intermediary linking investors to companies.

9. https://www.oecd.org/pensions/private-pensions/Pension-Markets-in-Focus-2019.pdf accessed 20 April 2022.

10. https://www.oecd.org/pensions/private-pensions/Pension-Markets-in-Focus-2019.pdf accessed 20 April 2022.

11. https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR19_03/SR_EFSI_EN.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2022.

12. https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR19_03/SR_EFSI_EN.pdf p.31. Accessed 15 January 2022.

References

- Asimakopoulos, I. G. 2018. “International Law as a Negotiation Tool in Banking Union; the Case of the Single Resolution Fund.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (2): 118–131. doi:10.1080/17487870.2018.1424631.

- Beck, T., and B. Bruno. 2022. The European Central Bank’s Close Cooperation on Supervising Banks in Bulgaria and Croatia, PE 699.521. Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) Directorate-General for Internal Policies.

- Bethlendi, A., and K. Mérő. 2020. “Changes in the Structure of Financial Intermediation – Eastern-Central European Developments in the Light of Global and European Trends.” Danube 11 (4): 283–299. doi:10.2478/danb-2020-0017.

- Birch, K., and F. Muniesa, Eds. 2020. Assetization: Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/12075.001.0001.

- Bohle, D., and B. Greskovits. 2012. Capitalist Diversity on Europe’s Periphery. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Braun, B., D. Gabor, and M. Hübner. 2018. “Governing through Financial Markets: Towards a Critical Political Economy of Capital Markets Union.” Competition & Change 22 (2): 101–116. doi:10.1177/1024529418759476.

- Brenner, D. 2022. Fortressing on Markets: Financial Supervision in the Capital Markets Union. (Doctor School of Political Science, Public Policy, and International Relations, Central European University.) Vienna, Austria.

- Bruszt, László, Dóra Piroska, and Gergő Medve-Bálint. 2022. “The EIB in the Light of European Integration Theories: Conserving the Tilted Playing Field.” In Deciphering the European Investment Bank: History, Politics, and Economics, edited by Lucia Coppolaro and Helen Kavvadia. London: Routledge.

- Bruszt, L., D. Piroska, and G. Medve-Bálint. 2022. “The EIB in the Light of European Integration Theories: Conserving the Tilted Playing Field “. In Coppolaro, Lucia, Kavvadia, Helen (Eds.). Deciphering the European Investment Bank: History, Politics, and Economics. London: Routledge.

- Calomiris, C., and S. Haber. 2014. Fragile by Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Camba, A. A., and R. A. Epstein. 2023. “From Duterte to Orbán: The Political Economy of Autocratic Hedging.” Journal of International Relations and Development. Forthcoming.

- Cooiman, F. 2021. “Veni Vidi VC – The Backend of the Digital Economy and Its Political Making.” Review of International Political Economy 1–23. doi:10.1080/09692290.2021.1972433.

- Donnelly, S. 2018. Power Politics, Banking Union and EMU. London: Routledge.

- Donnelly, S., and I. G. Asimakopoulos. 2020. “Bending and Breaking the Single Resolution Mechanism: The Case of Italy.” Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (4): 856–871. doi:10.1111/jcms.12992.

- Endrejat, V., and M. Thiemann. 2019. “Balancing Market Liquidity: Bank Structural Reform Caught between Growth and Stability.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 22 (3): 226–241. doi:10.1080/17487870.2018.1451751.

- Endrejat, V., and M. Thiemann. 2020. “When Brussels Meets Shadow Banking – Technical Complexity, Regulatory Agency and the Reconstruction of the Shadow Banking Chain.” Competition & Change 24 (3–4): 225–247. doi:10.1177/1024529420911171.

- Epstein, R. A. 2014. “When Do Foreign Banks ‘Cut and Run’? Evidence from West European Bailouts and East European Markets.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (4): 847–877. doi:10.1080/09692290.2013.824913.

- Epstein, R. A. 2017. Banking on Markets: The Transformation of Bank-State Ties in Europe and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Epstein, R. A., and M. Rhodes. 2016. “The Political Dynamics behind Europe’s New Banking Union.” West European Politics 39 (3): 415–437. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1143238.

- Epstein, R. A., and M. Rhodes. 2018. “From Governance to Government: Banking Union, Capital Markets Union and the New EU.” Competition & Change 22 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1177/1024529417753017.

- European Systemic Risk Board. 2020a. “Recommendations of the ESRB on Restrictions of Distributions during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Official Journal of the European Union May 27.

- European Systemic Risk Board. “System-wide Restraints on Dividend Payments, Share Buybacks and Other Payouts.” European System of Financial Supervision. June 2020b

- Fabio, Bulfone, and Agnieszka Smoleńska. 2020. “The Internal and External Centralisation of Capital Markets Union Regulatory Structures: The Case of Central Counterparties.” In Governing Finance in Europe, edited by Adrienne Héritier and Magnus G. Schoeller, 52–78, Edgal Elgar.

- Farkas, B. 2016. Models of Capitalism in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-60057-8.

- Fernandez, R., and M. B. Aalbers. 2017. “Capital Market Union and Residential Capitalism in Europe: Rescaling the housing-centred Model of Financialization.” Finance and Society 3 (1): 32–50. doi:10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1937.

- Fromage, D. 2022. “Multilevel (Administrative) Cooperation in the EU: The Unique Case of the Banking Union.” In Jacques Ziller, a European Scholar, edited by D. Fromage, 152-163. European University Institute .

- Hardie, I., D. Howarth, S. Maxfield, and A. Verdun. 2013 “Banks and the False Dichotomy in the Comparative Political Economy of Finance.” World Politics. Vol. 65: 4. 691–728. 10.1017/S0043887113000221.

- Hassel, A., M. Naczyk, and T. Wiß. 2019. “The Political Economy of Pension Financialisation: Public Policy Responses to the Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 1–18. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1575455.

- Högenauer, A., D. J. Howarth, and L. Quaglia. 2023. “The Persistent Challenges to Banking Union.” Journal of European Integration forthcoming

- Howarth, D. J., and L. Quaglia. 2016. The Political Economy of European Banking Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howarth, D., and L. Quaglia. 2021. “Failing Forward in Economic and Monetary Union: Explaining Weak Eurozone Financial Support Mechanisms.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (10): 1555–1572. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1954060.

- Hübner, M. (2016). Securitisation to the Rescue: The European Capital Markets Union Project, the Euro Crisis and the ECB as “Macroeconomic Stabilizer of Last Resort.” http://www.feps-europe.eu/en/publications/details/435

- Johnson, J., Barnes, A. 2015 “Financial Nationalism and its International Enablers: The Hungarian Experience.“ Review of International Political Economy 22 (3): 535–569 doi:10.1080/09692290.2014.919336

- Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2021. “When Do Banks Do What Governments Tell Them to Do? A Comparative Study of Greek Bonds’ Management in France and Germany at the Onset of the Euro-crisis.” New Political Economy 26 (4): 674–689. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1810214.

- Massoc, Elsa Clara. 2022. “Having Banks ‘Play Along’ state-bank Coordination and the state-guaranteed Credit Programs during the COVID-19 Crisis in France and Germany.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (7): 1135–1152. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1924839.

- Mérő, K., and D. Piroska. 2016. “Banking Union and Banking Nationalism – Explaining opt-out Choices of Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic.” Policy and Society 35 (3): 215–226. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2016.10.001.

- Mérő, K., and D. Piroska. 2018. “Rethinking the Allocation of Macroprudential Mandates within the Banking Union – A Perspective from East of the BU.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (3): 240–256. doi:10.1080/17487870.2017.1400435.

- Mertens, D., and M. Thiemann. 2017. “Building a Hidden Investment State? the European Investment Bank, National Development Banks and European Economic Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy 1–21. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1382556.

- Mertens, D., and M. Thiemann. 2018. “Market-based but state-led: The Role of Public Development Banks in Shaping market-based Finance in the European Union.” Competition & Change 22 (2): 184–204. doi:10.1177/1024529418758479.

- Mertens, D., and M. Thiemann. 2022. “Investing in the Single Market? Core-periphery Dynamics and the Hybrid Governance of Supranational Investment Policies.” Journal of European Integration 44 (1): 81–97. doi:10.1080/07036337.2021.2011261.

- Naczyk, Marek. 2014. “Budapest in Warsaw: Central European Business Elites and the Rise of Economic Patriotism since the Crisis.” SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at SSRN 2550496. 10.2139/ssrn.2550496.

- Naczyk, Marek. 2022. “Taking Back Control: Comprador Bankers and Managerial Developmentalism in Poland.” Review of International Political Economy 29 (5): 1650–1674. doi:10.1080/09692290.2021.1924831.

- Naqvi, N., A. Henow, and H.-J. Chang. 2018. “Kicking Away the Financial Ladder? German Development Banking under Economic Globalisation.” Review of International Political Economy 25 (5): 672–698. doi:10.1080/09692290.2018.1480515.

- Nizaeva, M., and A. Coskun. 2019. “Investigating the Relationship between Financial Constraint and Growth of SMEs in South Eastern Europe.” SAGE Open 9 (3): 2158244019876269. doi:10.1177/2158244019876269.

- Nölke, A., and A. Vliegenthart. 2009. Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism: The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe. World Politics. Vol. 61: 4. 670–702. 10.1017/S0043887109990098.

- Nyikos, G., A. Béres, T. Laposa, and G. Závecz. 2020. “Do Financial Instruments or Grants Have a Bigger Effect on SMEs’ Access to Finance? Evidence from Hungary.” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 12 (5): 667–685. doi:10.1108/JEEE-09-2019-0139.

- Orenstein, M. A. 2005. “The New Pension Reform as Global Policy.” Global Social Policy 5 (2): 175–202. doi:10.1177/1468018105053678.

- Piroska, D., Y. Gorelkina, and J. Johnson. 2020. “Macroprudential Policy on an Uneven Playing Field: Supranational Regulation and Domestic Politics in the EU’s Dependent Market Economies.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (3).

- Piroska, D., and K. Mérő. 2021. “Managing the Contradictions of Development Finance on the EU’s Eastern Periphery: Development Banks in Hungary and Poland.” The Reinvention of Development Banking in the European Union.

- Quaglia, L. 2019. “The Politics of an ‘Incomplete’ Banking Union and Its ‘Asymmetric’ Effects.” Journal of European Integration 41 (8): 955–969.

- Quaglia, L., and D. Howarth. 2018. “The Policy Narratives of European Capital Markets Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (7): 990–1009. doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.1433707.

- Rehm, M. 2022. “Delegation and Control: The ESM’s Role as Common Backstop for the SRF”. In Paper Presented at the Workshop on the Politics, 12–13. May: Law and Political Economy of European Banking Union. University of Luxembourg.

- Sapir, A., N. Véron, and G. B. Wolff. 2018. “Making a Reality of Europe’s Capital Markets Union.” 13.

- Spendzharova, A. B. 2014. “Banking Union under Construction: The Impact of Foreign Ownership and Domestic Bank Internationalization on European Union member-states’ Regulatory Preferences in Banking Supervision.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (4): 949–979. doi:10.1080/09692290.2013.828648.

- Véron, N. 2015. “Europe’s Radical Banking Union.” In Bruegel Essay and Lecture Series. Brussels: Bruegel. 5–61.

- World Bank. (2019). “Banking Supervision and Resolution in the EU: Effects on Small Host Countries in Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe.” Working Paper. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.