ABSTRACT

Banking Union was a major policy response to the financial crisis that began in 2007 and the subsequent Eurozone crisis. Moral hazard has frequently been presented as a major cause of these crises. Therefore, Banking Union can be understood as a response to moral hazard in relation to banks and sovereigns. Yet, moral hazard was an acknowledged and supposedly managed problem prior to these events. Paradoxically, moral hazard has been used to justify contradictory policy options to safeguard European financial system stability, such as decentralized institutional arrangements for banking supervision but also a centralized system coordinated by the European Central Bank (ECB). To address this paradox, this paper investigates moral hazard as a political concept. Based on a comparison of how central bankers from the Bundesbank and the ECB understand and use the moral hazard concept, this paper argues that moral hazard is closer to the realm of politics than expertise.

Introduction

European Banking Union was presented by a range of national, European and international policymakers as a potential institutional development to reduce moral hazard for banks and sovereigns, which was frequently described as a major cause of the international financial crisis (IFC) that began in 2007 and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone (e.g. De Grauwe Citation2011). In Banking Union, with the conferral of supervisory tasks to the European Central Bank (ECB), the latter acquired a significant responsibility to ensure financial stability in the Union (Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 of 15 October Citation2013). Clearly, moral hazard was an acknowledged and supposedly managed problem prior to these crises. However, this management was principally at the national and not at the supranational level. The use of the moral hazard concept has justified, over time, significantly different institutional frameworks to safeguard financial stability in the EU. Prior to the IFC what was perceived as the central risk in relation to moral hazard in the financial sector was ex ante explicit coordination at the EU level. This belief justified the decentralised arrangements for banking supervision (Dyson Citation2000, 20–22). The ubiquitous use of the moral hazard concept in official explanations for different and often contradictory policy options is surprising. This puzzling ubiquity is also to be found in opposed preferences on Banking Union. For example, while the German government and the Bundesbank presented divergent positions from those of the ECB on almost all issues related to Banking Union (see, for example, Wasserfallen et al. Citation2019), the officials of both central banks also placed considerable emphasis on the need to prevent moral hazard. To address this paradox, this paper argues that moral hazard is a political concept: the precise meaning of moral hazard is contested and policymakers try to influence other actors’ beliefs on moral hazard to achieve negotiated policy outcomes in line with their preferences.

This paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we situate our analysis in relation to existing studies focused on the importance of ideas and notably moral hazard in shaping the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) project and briefly review the academic literature on moral hazard. In the third section, we elaborate on our theoretical framework which combines elements of sociological institutionalism and strategic constructivism and the mixed methods that we apply to demonstrate different usage of the moral hazard concept in our two central bank case studies: the Bundesbank and the ECB. In the fourth section, we summarise the results of our empirical analysis demonstrating differences in how Bundesbank and ECB officials understand the moral hazard concept with regard to Banking Union-related issues. In the fifth section, we provide a summary of the discursive strategies employed by these central bankers to try to influence others’ beliefs on moral hazard. In the final section, we conclude.

State of the art: the centrality of moral hazard in shaping EMU

German ordoliberal views shaped the institutional design and rules of the EMU project (Dyson and Featherstone Citation1999; Dyson Citation2021) and preoccupation with moral hazard is a core element of German ordoliberal ideas (Bonatti and Fracasso Citation2013; Bulmer Citation2014; Siems and Schnyder Citation2014). A substantial body of academic literature exists demonstrating the longstanding importance of the ordoliberal tradition for the Bundesbank – notably the need for sound money and to prevent moral hazard (Marsh Citation1992; McNamara Citation1998; Dyson Citation1994). Considerable literature also exists demonstrating the importance of the Bundesbank mandate and design as a model for the mandate and design of the ECB (Dyson Citation1994; Howarth Citation2004; Howarth and Loedel Citation2005). In addition, Hallerberg (Citation2014) identifies the Stability and Growth Pact as the model of fiscal regulation designed to prevent moral hazard. Thus, there is extensive literature indicating that preventing moral hazard has been a governing principle in the foundation of the monetary, fiscal, and (as noted above) financial pillars of EMU. A number of scholars have also emphasized the importance of moral hazard in shaping EMU reform and other policies in the context of the post-2007 financial and economic crises (e.g. Dyson Citation2014, 43–45). More specifically, some authors point to the role of moral hazard arguments in the strengthening of fiscal policy rules and austerity (Blyth Citation2013), the demise of the Eurobond (Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015), or the policy outcomes of Banking Union (Schäfer Citation2016; Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016). The transformative power of the moral hazard concept in relation to EMU is therefore significant.

Moral hazard has been a fertile source of research since the 1970s and the subject of vivid interest of leading neoclassical economists curious about what happens with optimal states in situations of imperfect information (e.g. Arrow Citation1963; Holmström Citation1979; Stiglitz Citation1983). Nonetheless, moral hazard is characterized by fuzzy economic knowledge (Leaver Citation2015). Neoclassical economists have been productive in constructing models of moral hazard – in which the existence of moral hazard is assumed – but the empirical research on moral hazard is relatively less extensive (Lane and Phillips Citation2000, 3), and inconclusive. Furthermore, the empirical evidence of moral hazard in environments with imperfect information is inconsistent (e.g. Dam and Koetter Citation2012; Lane and Phillips Citation2000; Noy Citation2008). Hence, this paper also aims to fill a gap in the academic literature by contributing to explain the power of the moral hazard concept in shaping debates on major EU institutional change, despite the lack of precise knowledge on moral hazard in this context. If moral hazard is not an obvious and well-known fact but is characterized by uncertainty, then its transformative power must rest on the use of ideational elements.

Theoretical framework and methods

This paper aims to answer the following research question: How can we best explain the ubiquity of the moral hazard concept in justifying divergent positions regarding financial stability and the elements of Banking Union? Carstensen and Schmidt (Citation2016, 321) have developed the claim that ‘ideas matter’ in politics by conceptualizing ideational power, that is, ‘the capacity of actors (whether individual or collective) to influence other actors’ normative and cognitive beliefs through the use of ideational elements’. Ideational power implies that ideas are not dominant or significant per se but become so (or not). Theories that take ideas seriously present distinct sets of conditions under which ideas become dominant. For example, a number of studies using sociological institutionalism focus on the role of ideational consensus. For instance, McNamara (Citation1998) examines the role of a new ideational consensus in the success of the European Monetary System (and the adoption of the EMU project). According to McNamara, the development of a neoliberal consensus among European policy-making elites since the mid-1970s allowed for a convergence in policy preferences and made the creation of a system based on German price stability possible. However, of particular relevance to the analysis here, other theories – such as strategic constructivism (Jabko Citation2006) – are helpful to explain the power of certain ideas when no ideational consensus is present and policy preferences are divergent. Here, ideas are strategic resources at the disposal of actors to influence others and help them achieve certain goals. According to Jabko (Citation2006), the ambiguity of the concept of the ‘market’ allowed the promoters of Europe to bring together actors with diverse motivations and to build the single market and monetary union. The ambiguity of concepts often presents an opportunity to policymakers (e.g. Crespy and Vanheuverzwijn Citation2019). However, the strategic property of concepts is not limited to their ambiguity – that allows actors to construct and reconstruct concepts depending on contexts and changing circumstances; concepts are also strategically framed in policy discourses to persuade others of the validity, adequacy, or necessity of a particular policy action or to discredit and resist alternatives (Hay and Rosamond Citation2002; Howarth and Rommerskirchen Citation2013). For example, Blyth (Citation2013) argues that the dominant narrative in Europe on the financial crisis as ‘a sovereign debt crisis’ was a strategic construct aimed at helping policymakers to face a material constraint – a European banking system ‘too big to bail’ – and to legitimize the choice of austerity.

Before formulating our hypothesis to explain the wielding of the moral hazard concept with regard to financial stability and Banking Union, we need to clarify and justify which actors will be investigated in this paper, namely top Bundesbank and ECB officials. There are four main reasons to justify this selection of actors. First, central bankers played a crucial role in shaping and legitimizing the institutional design of EMU. The ability of EU central bankers to build a professional consensus around the ‘sound money’ paradigm was a necessary condition for the creation of the Eurozone (Dyson and Featherstone Citation1999). We expect the role of central bankers to be important with regard to EMU reforms despite the Bundesbank’s clear loss of influence since 1999 (Dyson Citation2010). To investigate the ideational power of central bankers is all the more relevant in the context of Banking Union as they possessed both policy authority and technical knowledge in relation to financial markets. Second, the comparison of a national central bank (NCB) with the ECB is of analytical interest as it allows us to determine the relevance of the cleavage ‘national versus supranational’ in relation to so-called technocratic institutions. Despite the independence of Eurozone central banks and the position of NCB governors on the ECB’s Governing Council as experts rather than national representatives, nothing in the treaties prevents NCB governors from representing institutional and/or national preferences. Indeed, a small body of literature exists that demonstrates a certain alignment between national government and NCB governor preferences or a perception of such an alignment on major institutional reforms (Howarth Citation2007). We might also expect that NCB positioning on Eurozone developments would reflect/align with national government economic priorities. Third, there are several reasons to compare the German NCB with the ECB with regard to preferences on Banking Union specifically: even though the ECB was set up in emulation of the Bundesbank’s mandate and design, the ECB and the Bundesbank presented significantly divergent positions on almost all issues related to Banking Union. The two central banks had markedly different institutional interests with regard to Banking Union – the Bundesbank was set to lose supervisory powers while the ECB was set to gain them (Epstein and Rhodes Citation2016). However, fourth, the different positioning of the Bundesbank and ECB also reflected the greater influence of ordoliberalism in the former (Dyson Citation2010).

To explain the ubiquity of the moral hazard concept in justifying divergent positions regarding financial stability and Banking Union we test the following hypothesis that can be drawn from strategic constructivism:

Bundesbank and ECB officials strategically used the ambiguity of the moral hazard concept to legitimize policy options on Banking Union in line with their institutional preferences and tried to persuade other actors to accept and adopt their understandings of the concept.

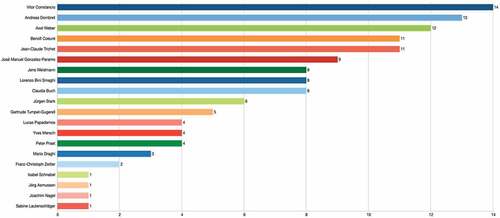

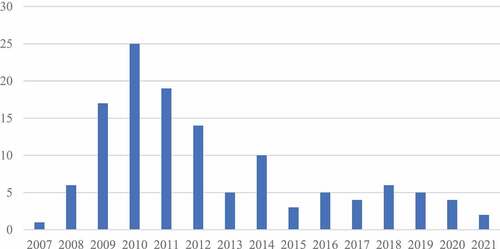

The testing of this hypothesis requires us to identify what moral hazard means to Bundesbank and ECB officials and how these central bankers try to influence discursively the beliefs of others on moral hazard and Banking Union-related issues. To do this, a selection of speechesFootnote1 – available on the respective institutional websites – was made based on the following cumulative criteria: there is at least one occurrence of the term moral hazard in the document; the date of the document is equal or superior to 01.01.2007; and the topic of banking supervision or financial stability is present in the document.Footnote2 The result is a corpus of 126 documents: 44 speeches of six Bundesbank Executive Board members and 82 speeches of fourteen ECB Executive Board members in office between 2007 and 2021.Footnote3 We place our detailed data in . respectively describe the distribution of speeches by speaker and by year (see the on-line appendix for a full list of speeches).

To identify meanings of moral hazard in our case studies, we first created a dataset of moral hazard occurrences in their textual context – 1 sentence before and after. To infer meanings from these occurrences and compare various sorts of similarities and differences in how moral hazard is understood between cases, we used a mixed method that combines inductive quantitative and qualitative text analysis techniques. On the one hand, we looked at the semantic fields of moral hazard (word clouds, synonymous and antonymous concepts); on the other hand, we manually coded the descriptions of moral hazard according to four main dimensions: ‘what it is’, ‘what causes it’, ‘what it does’, and ‘how to deal with it’. The analysis is made using the software MAXQDA. This text analysis has been combined with the organisation of four interviews (one with a Bundesbank official and three with ECB officials).Footnote4 In addition, this paper investigated the discursive strategies employed by officials from the two central banks to try to influence others’ beliefs on moral hazard. To do so, we used an expanded dataset of moral hazard occurrences (5 sentences before and after). From this dataset, we surveyed expressed positions on financial stability, and examined two types of discursive strategies: argumentation-oriented analysis and legitimation – which focuses on the construction of arguments and legitimacy of positions – (Van Leeuwen Citation2007) and discursive self- and other- presentation – which focuses on the representation of social actors and the creation of difference (Van Leeuwen Citation1996; Reisigl and Wodak Citation2000). The empirical results are presented in the next two sections.

Comparing meanings of Moral Hazard

Semantic fields of moral hazard in the corpus

To determine the semantic field of moral hazard by case study, we focused on three types of word-relations: words that are frequently used around moral hazard; words described as having the same or similar general sense as moral hazard; and words described as having an opposite meaning to moral hazard. present the word clouds of moral hazard respectively in the case of the Bundesbank and the ECB. The top 5 most frequently used words next to moral hazard in speeches from the Bundesbank are: risk, systemic, problem, reduce, and important. The top 5 most frequently used words next to moral hazard in speeches from ECB are: bank, risk, create, avoid, and reduce. There are similarities and differences in these results. In both cases, moral hazard is strongly associated with the word ‘risk’, which refers to the possibility of something (most usually) bad. Thus, moral hazard relates to something uncertain (and unwelcome). There are three noteworthy differences in Bundesbank and ECB usage. First, the emphasis on ‘something bad’ appears stronger in the case of the Bundesbank, where the word ‘problem’ is relatively more often used next to moral hazard. Second, moral hazard appears as something relatively more specific in terms of actors in the case of the Bundesbank. The frequency of the words ‘systemic’ and ‘important’ suggests that moral hazard relates more often to actors like ‘systemic financial institutions’ or ‘systemically important financial institutions’ (SIFIs), while in the case of the ECB, moral hazard seems to relate more frequently to all banks. Third, ECB officials appear more confident in their capacity to control moral hazard than policymakers of the Bundesbank. The frequency of the words ‘create’ and ‘avoid’ in relation to moral hazard suggests a form of control over moral hazard, while in the case of the Bundesbank we found only the word ‘reduce’.

Figure 3. The word cloud of moral hazard in the case of the Bundesbank, by frequency of words.

Figure 4. The word cloud of moral hazard in the case of the ECB, by frequency of words.

The second type of word-relations we are interested in comparing are synonyms (see ). In both cases, moral hazard is similar to ‘adverse incentives’ or ‘wrong incentives’, ‘risk appetite’ or ‘appetite for risk’, ‘disincentives’, ‘risky behaviour’ or ‘risk-taking behaviour’, and ‘too big to fail’. Thus, moral hazard is considered both as a type of incentive and as a type of behaviour. These synonyms present in both central banks’ speeches suggest nuances in terms of allocation of blame: with incentives and ‘too big to fail’, the subject is passive; while in the case of behaviour, the subject is active. In addition, in both case studies we found instances where moral hazard is close to the realm of morality and justice: as, for example, with moral temptation and unfair burden sharing (in the case of the Bundesbank), and anti-social behaviour and sheer greed (in the case of the ECB). When it comes to differences, it seems that moral hazard is more strongly related to ideas of market imperfection in the case of the ECB than in the case of the Bundesbank; also, in the case of the ECB, moral hazard is more about ‘risk beyond the right level’ rather than risk per se.

Table 1. List of close synonyms, by case study.

Finally, the last type of word-relations we are interested in comparing are antonyms (see ). In both cases, moral hazard is the opposite of correct, right, or appropriate incentives, of caution or prudence, and of accountability or internalization of externalities. When it comes to differences, there is more variety in the case of the ECB: moral hazard is not something that can be qualified as an ‘exogenous shock’ or that is characterized by stability.

Table 2. List of anti-concepts (antonymous), by case study.

Descriptions of moral hazard in the corpus

To identify how Bundesbank and ECB policymakers understand moral hazard, we complement the analysis of the semantic fields with a coding exercise: each occurrence of moral hazard has been coded in relation to the four dimensions mentioned in the previous section (the results are presented in ). A first conclusion that can be drawn from these results is that, in both cases, policymakers put relatively more emphasis on policy prescriptions (157 coded segments in ‘how to deal with it’) and causes (131 coded segments in ‘what causes it’), than on its essence (49 coded segments in ‘what it is’) and effects (34 coded segments in ‘what it does’). This suggests that the heart of the policy debate about moral hazard with regard to financial stability and the elements of Banking Union is centered on the potential solutions to moral hazard, not its meaning. The observation that ‘what moral hazard is’ is not often explicit in the speeches of central bankers implies a certain professional consensus around its meaning, allowing policymakers to take the concept for granted in their communication.

Table 3. What it is, by case study.

Table 4. What actions or behaviours / what incentives, by case study.

Table 5. Whose actions or incentives, by case study.

Table 6. What causes it, by case study.

Table 7. What it does, by case study.

Table 8. How to deal with it, by case study.

However, we found sixteen ways to answer the question ‘what is moral hazard?’ (see ). In the case of the Bundesbank, the most frequent answer is ‘a situation in which there are incentives for a reckless action’; in the case of the ECB, the most frequent answer is ‘the fact of acting recklessly’. When comparing these two answers, both elements of consistency and variance can be found: while ‘a reckless action’ is a common element and represents the outcome, it is a potential outcome in the case of the Bundesbank versus an actual outcome in the case of the ECB. The results of ‘what moral hazard is’ strongly point towards specific actions or behaviours, and incentives for a specific conduct. It is therefore of interest to also look more closely into what, and whose, actions, behaviours, and incentives (see ). Here again, we found elements of consistency and variance. All specified actions or behaviours are reckless in a sense (be it because ‘willing to take risks’, or ‘lacking in prudence or caution’, or ‘irresponsible, disregard for consequences or danger’, or ‘lack of care or consideration for others’). However, in the case of the Bundesbank, the most frequent answer with regard to the type of action is ‘taking risks or more risks’, while the most frequent answer in the case of the ECB is ‘taking too much risks’. This result confirms the preliminary conclusion found in the subsection on semantic fields, namely that for the ECB moral hazard is mostly about exceeding an appropriate level of risk, while for the Bundesbank moral hazard is mostly about increasing risk. Another significant element of variability is the case of ‘(not) monitoring’, present in the case of the Bundesbank and absent in the case of the ECB. For policymakers of the Bundesbank, moral hazard seems to be linked to a large extent to the absence (or the inefficiency) of incentives to monitor. This understanding of moral hazard places blame on those who are supposed to supervise, not on those taking more risks. When it comes to the question of who is subject to moral hazard, financial market participants are largely cited as the actor most prone to moral hazard in both cases.Footnote5 However, while moral hazard principally regards SIFIs in the case of the Bundesbank, it concerns (all) banks in the case of the ECB.

When looking for answers to ‘what causes moral hazard’, we found that all causes seem to relate to something that reduces the exposure to consequences (see ). In the case of the Bundesbank, the most frequent causes of moral hazard relate to financial sector characteristics and activities, namely too big to fail financial institutions and the securitization of credit risk. While ECB officials also put strong emphasis on too big to fail financial institutions as a cause of moral hazard, the securitization of credit risk is almost non-existent in their speeches. Instead, central bankers from the ECB most frequently discuss different types of public intervention as a potential source of moral hazard (e.g. supportive measures in bad times, bailouts, ex ante mechanisms, etc.). It is worth mentioning that ‘asymmetry of information’ – one of the most typical causes cited in the economic literature – is almost never cited in the dataset as a source of moral hazard.

The analysis of effects of moral hazard brings additional information when it comes to how policymakers understand the concept (see ). In both cases, the most frequent cited effect of moral hazard is instability. However, there are also significant differences: in the case of the Bundesbank, we found a strong emphasis on the ‘unfair distribution of costs’ (absent in the case of the ECB); and in the case of the ECB, we found an emphasis on the ‘distortion of market efficiency’ (absent in the case of the Bundesbank). In both cases, moral hazard is considered as a collective problem. Yet, Bundesbank officials seem relatively more worried about the effect of moral hazard on social justice, while ECB officials seem relatively more worried about the effect of moral hazard on the efficiency of markets.

The last dimension under scrutiny are policy prescriptions (see ). In both cases, the most frequent cited solution to the problem of moral hazard is ‘to regulate the banking sector to make it safer’; ‘the internalization of costs within the private sector’ is also relatively frequent in both cases. However, there are significant differences. For example, in the case of the Bundesbank, solutions like ‘criteria to be eligible [for support]’ and ‘the respect of the principle of liability’ are relatively frequent (while absent in the case of the ECB). In the case of the ECB, solutions like ‘conditionality’, a monetary policy of ‘leaning against the wind’, and ‘sanctions or penalty’ are relatively frequent (while absent in the case of the Bundesbank). It is also worth stressing that, while not being the most frequent answers, central bankers of the ECB mentioned the need to develop a pragmatic attitude when dealing with moral hazard and acknowledged the need for further research.

Elucidating the moral hazard concept by interviewing

When asked if moral hazard was the main cause of the IFC, three of four central bank officials interviewed answered that it was indeed one of the causes. Among the central bankers who answered yes, moral hazard was described as either excessive risk taking by financial actors because of a public bail-out expectation (interviews 1 and 2), or as inappropriate behaviours by investors in relation to ethical and moral standards because of adverse incentives – lack of regulation plus greedy investors (interview 3). In the case of the interviewee who answered no, the justification is the following: the excess of credit that gave way to the crisis was mostly because of financial deregulation not because of moral hazard. Moral hazard played a role during the crisis but not as a cause. It played a role in the sense that when sometimes banks are very close to bankruptcy and you give them liquidity, they might have incentives to take more risks, making the crisis worst (interview 4). The four interviews reveal a significant degree of variation in how interviewees understand moral hazard: there is not a consensus on whether moral hazard was a cause of the IFC, nor is there a consensus on what was the source of moral hazard in this context – expectation of public bail out versus lack of regulation and greediness.

When directly asked about the meaning of moral hazard, the interviewees provided quite different answers (see answers’ transcriptions in the on-line appendix): in the first answer, moral hazard is defined in relation to its cause (i.e. not having to account for possible adverse consequences); in the second answer, moral hazard is defined in relation to its consequences (i.e. negative effects on others); in the third answer, moral hazard is defined in relation to normative standards (i.e. inappropriate behaviour); and in the fourth answer, moral hazard is defined in relation to the action per se (i.e. ‘take the money and run’). Each of these definitions of moral hazard would lead to different policy prescriptions.

In sum, answers to ‘what moral hazard means?’ for policymakers are not straightforward, even in the context of communications from central bankers on financial stability topics. Understandings of moral hazard by case studies differ in several aspects: (1) the scope of actors (some banks versus all banks), (2) the nature of the reckless action to count as moral hazard (potential versus actual), (3) the degree of risk to qualify as a reckless action (an increase in risks versus exceeding a right level of risks), (4) the emphasis on the securititzation of credit risk as a cause of moral hazard, (5) the degree of importance of the principle of liability, (6) the type of collective problem (social justice versus market efficiency), and (7) what should be the basis for an appropriate solution to moral hazard (a selection of the type of actor versus a selection of the type of action). The absence of a shared belief on moral hazard among EU central bankers is also illustrated by the material from the interviews.

Discursive strategies around Moral Hazard

Review of bundesbank and ECB officials’ positions

Unsurprisingly, most of the positions expressed by central bankers on how to best achieve financial (and macroeconomic) stability relate to the main components of Banking Union: supervision, resolution, regulation (e.g. on capital requirements), and deposit guarantee schemes (see ). The question of whether the main components of Banking Union contribute to reducing or increasing moral hazard, and hence whether they contribute to stability or instability, arises. Both Bundesbank and ECB officials approach regulation and deposit guarantee schemes in similar terms with regard to their effect on moral hazard. On the one hand, prudential rules for banks are described by both central bank officials as a suitable means to reduce moral hazard (and hence as a suitable means to achieve financial stability); on the other hand, the risk of moral hazard resulting from a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) is acknowledged in both cases, especially in relation to ‘legacy issues’ – that the danger of providing insurance coverage for banks with longstanding problems (Mersch Citation2016; Dombret Citation2018). However, despite this agreement on EDIS as a potential source of moral hazard, its effect on financial stability is disputed: only ECB policymakers are in favour of EDIS, and of not postponing its establishment (e.g. Constâncio Citation2016b; Mersch Citation2016).

Table 9. Positions on financial stability, by case study.

Bundesbank and ECB policymakers disagreed on other components of Banking Union in terms of their effect on moral hazard. On resolution, while both policymakers from the Bundesbank and the ECB welcome the establishment of a private bail-in regime – to lower the need of public bail-outs – as an effective means to reduce moral hazard, they disagree on how to achieve this objective. In particular, in the case of the ECB, officials supported the creation of a Single Resolution Fund (SRF) financed ex ante by contributions from the private sector as an appropriate mechanism to reduce moral hazard (e.g. Constâncio Citation2011a, Citation2011b); whereas Bundesbank officials opposed the SRF and considered it not only as incapable of solving the moral hazard of banks but also as a potential new source of moral hazard (e.g. Weber Citation2010). While Bundesbank and ECB officials appear more aligned on the need for the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) as a means to reduce moral hazard, officials at the two central banks placed emphasis on different channels. For example, ECB officials stressed the need to reduce the moral hazard resulting from the information asymmetry between a non-supervisory central bank and national supervisors (Lautenschläger Citation2014). Bundesbank officials placed emphasis on reducing the moral hazard of SIFIs, and the moral hazard resulting from biased national supervision (Weidmann Citation2017).

In sum, officials from both central banks find that moral hazard is both pervasive and ambiguous in the context of Banking Union. In some cases, there is a professional consensus among officials from the two central banks on whether a certain component of Banking Union contributes to reduce or increase moral hazard, even though this consensus does not necessarily translate into an agreement on what is best in terms of financial stability. In other cases, a doubt exists on whether a certain component of Banking Union contributes to reducing or increasing moral hazard. The next sub-sections review the discursive strategies employed by central bankers to strengthen their positions and to weaken alternative positions (). at the end of this section provides a summary of the main discursive strategies employed by central bankers to legitimize their positions).

Table 10. Main discursive strategies around moral hazard to legitimise positions.

ECB discursive strategies

Policymakers from the ECB employ several discursive devices to strengthen their positions and to weaken alternative positions. Based on illustrative statements, we provide a summary of the most frequent discursive devices used by central bankers from the ECB to influence others’ beliefs about moral hazard. To give strength to their arguments and build legitimacy around their positions, one of the most frequent devices employed by ECB officials is to play on the complexity of the social world and to present their positions as responding to this complex reality. Policymakers from the ECB emphasize the difference between theory and practice, notably in terms of the efficiency of markets (e.g. Bini Smaghi Citation2011a), rational preferences (e.g. Tumpel-Gugerell Citation2011), and perfect information (e.g. González-Páramo Citation2009a). In contrast to a simplified theoretical situation in which markets are efficient, agents rational, and information perfect, ECB officials stress that they are facing a complex reality, made of dilemmas and trade-offs. Moral hazard is often discursively constructed as being at the heart of such difficult choices, where no easy solutions are available to policymakers. See, for example:

‘On the one hand, we must avoid doing the job of others, taking away their incentive to adopt measures within their competence, thus creating moral hazard. On the other hand, we cannot hide behind principles and rules designed for a theoretical situation which no longer corresponds to the reality, and cannot give up fulfilling our responsibilities to avoid much worse situations’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011a, 10).

If the positions of ECB policymakers respond to a complex reality characterized by difficult choices, the alternative positions must be in line with theoretical models that present easy choices or ignore empirical evidence and developments. The framing of alternative positions in such ways is used by ECB officials to weaken their opponents’ arguments about moral hazard:

‘The proof that this system does not encourage moral hazard lies in the fact that countries in distress wait until the last moment before subjecting themselves to the Fund’s conditionality’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011a, 7).

‘Inaction based on fear of complications is rooted in the belief that there is no need to change existing arrangements, even when all evidence and analysis point to the need to act. But this complacency is motivated by arguments that often find no support in reality’ (Draghi Citation2019, 3).

Another common (and related) discursive device employed by ECB officials is to portray their positions as being moderate or balanced, and to portray the alternative positions as extreme or lacking in judgment:

‘In crises, extreme solutions — activism with full discretion on the one hand, and total lack of action on the other — may seem easy to some, but such solutions are mistaken’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011a, 10).

‘This requires striking the right balance between insuring against crises, curbing risk-taking behaviour and mitigating moral hazard with a strong incentive framework’ (Coeuré Citation2014, 3).

With regard to moral hazard, ECB officials also tend to strengthen their position and to weaken alternatives by referring to knowledge. They construct legitimacy around their positions by presenting them as being in conformity to academic research, and in accordance with the positions of figures of authority in the field of macroeconomics, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

‘Influential research literature claims that liquid stock markets help foster corporate governance and hence reduce moral hazard’ (Trichet Citation2010, 3).

‘Finally, many, including the staff of the IMF, have supported the idea of a European Resolution Authority responsible for crisis management and resolution, probably combined with a European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Fund’ (Constâncio Citation2011b, 4).

On the contrary, alternative positions are described as being based on limited academic knowledge – that is, areas where economic analysis is not extensive, conclusive, or where a relatively high degree of uncertainty remains:

‘Moral hazard and policy instrument instability pose questions to which we are not in a position to [provide] a firm answer at this point in time. I would like to see these questions studied and debated in eminent academic institutions like this’ (Trichet Citation2009, 8).

‘The literature on whether adding banking supervision to monetary policy creates conflicts of interest is not well developed. The concern is that a central bank which is also in charge of supervision would turn into a supervisor with access to central bank liquidity. As recently pointed out by Stefan Gerlach, it could then occasionally relax its monetary policy, potentially generating an inflationary bias impairing its credibility, and also contribute to more risk-taking by banks (moral hazard), and in turn breed future financial instability. The central bank could in particular be inclined to continue lending to weak banks for fear that winding them up would trigger losses. Although this literature is not conclusive, we take such concerns extremely seriously’ (Coeuré Citation2013, 4).

An additional discursive device used by ECB officials to strengthen their positions and weaken the alternatives is to play around the boundaries of legitimacy. On the one hand, they recognize the acceptability of certain principles expressed by their opponents in relation to moral hazard:

‘There is no question that moral hazard issues need to be taken very seriously into account when central banks decide on measures to support the banking system in a situation of financial turmoil’ (González-Páramo Citation2008, 16).

‘In a financial crisis which is partly derived from excessive public debt, monetary policy should avoid covering the liabilities of fiscal policy and printing money to finance the public debt, thereby coming to the aid of the fiscal authorities and allowing them to postpone the adjustment — again a problem of moral hazard’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011a, 7).

On the other hand, they present the alternative positions as illegitimate because the issue justifying such positions is currently being addressed:

‘This is not a new issue. It has been dealt with in the context of the IMF and consists of attaching strong conditions, in terms of structural and fiscal policies, to any financial support that is provided to a country in difficulty. Financial support is disbursed only according to precise milestones, linked to compliance with the conditions contained in the programme. There is no need for Europe to reinvent the wheel’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2010, 5).

‘To protect against such effects both the regulation proposed by the European Commission and the ECB’s Opinion on this regulation call for a governance structure that strictly separates the monetary functions from the supervisory functions’ (Coeuré Citation2013, 4).

‘The European Commission’s proposal sets out a clear roadmap towards a single EDIS, which I strongly welcome. It already provides safeguards against moral hazard and ensures that banks pay for their own risks’ (Constâncio Citation2016a, 3).

Furthermore, to weaken alternative positions on moral hazard, ECB officials often describe moral hazard as a type of concern as opposed to a type of problem. This rhetorical device can be interpreted as a kind of euphemism since it aims to attenuate or mitigate moral hazard: the formulation ‘concerns of moral hazard’ implicitly indicates that moral hazard is a cause for worry, which – after reassurance – might be unnecessary. This framing of moral hazard poses a specific relationship between ECB officials and their opponents: ECB officials play the role of a trusted figure who is there to reassure, while opponents play the role of worried children who need reassurance.

To strengthen their positions, ECB officials also emphasize the conformity of such positions to the legal mandate of the institution – in particular, to the primary objective of price stability – and to the tradition it embodies. ECB officials tend to legitimize their positions by presenting them not in rupture but in continuity with the past:

‘Here, we have to be especially vigilant to shield monetary policy from attempts to engross it into inappropriate financial stability tasks; for such attempts may turn out to be disguised aspirations to drag the well-established paradigms of monetary dominance towards the realm of fiscal dominance’ (Praet Citation2012, 4).

‘If the ECB had not provided liquidity, there would have been bailouts, abrupt debt reduction and thus a deepening of the recession — and this would have made our mandate of ensuring price stability much more difficult’ (Lautenschläger Citation2014, 2).

Finally, in parallel to discursive strategies aimed at constructing arguments and the legitimacy of positions, ECB officials also employ strategies to construct in-groups and out-groups and to label social actors more or less positively or negatively. To strengthen their position, ECB officials tend to emphasize their membership of the group of central banks. As a member of this group, the ECB acts as (any) other central bank:

‘In response to these tensions, the ECB and other central banks have undertaken a variety of liquidity management operations in order to support the interbank money market’ (González-Páramo Citation2008, 16).

‘Not only the ECB, but all the central banks of developed countries have implemented measures geared to the difficulty of the situation’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011a, 10).

Unsurprisingly, ECB officials tend to label the ECB positively. In particular, the ECB is portrayed as a modern and innovative protector or guardian, as the ‘only game in town’, and – on one occasion – as a scapegoat:

‘This new programme is a clear example of how far the ECB fulfils contemporaneously the role as a stability guardian and as crisis manager’ (Asmussen Citation2012: 4).

‘It follows logically from the points I have just made that the central bank, as the only player that has no liquidity constraints, can and should help to overcome a liquidity crisis by injecting additional cash into the system’ (González-Páramo Citation2009b, 2).

‘The ECB, for example, was reprimanded for having exacerbated the Irish crisis in November 2010, after demanding for a long time that the government swiftly adopt the necessary measures for fiscal consolidation. Recently, a former Irish Prime Minister has even had the honour of front page headlines when he reproached the ECB for not having sufficiently monitored the Irish banking system when it is well known that in Europe the powers of prudential supervision are the responsibility of the national authorities, a competence that you do not want to give up’ (Bini Smaghi Citation2011b, 4).

Bundesbank discursive strategies

Similarly, top Bundesbank officials employ discursive devices to strengthen their positions and to weaken alternative positions. We summarise here the most frequent discursive devices used by German central bankers to influence others’ beliefs about moral hazard. In contrast to what was found in the case of the ECB, it is worth stressing that Bundesbank officials never describe moral hazard as a type of concern but as a kind of problem. This rhetorical device can be interpreted as a kind of hyperbole in that it aims to emphasize or exaggerate moral hazard: formulations such as ‘the problem of moral hazard’ or ‘die Moral Hazard Problematik’ are often used by Bundesbank policymakers and implicitly indicate that moral hazard needs to be taken (more) seriously to be solved. This framing of moral hazard allows German central bankers to present themselves as responsible actors, while they depict opponents as irresponsible actors.

ECB officials are not alone in playing the card of conformity to academic knowledge to construct legitimacy around their positions. To strengthen their positions in relation to moral hazard, Bundesbank officials also present themselves as being in conformity with economic knowledge, be it theoretical or empirical:

‘I would like to draw your attention again to general economic theory as this enables us to identify fundamental problems that are well known to an economist’ (Weber Citation2008, 4).

‘The empirical results of a paper by Mora and Sowerbutts at the conference indicate that this is not only a theoretical reflection, but a present mechanism in the securitisation market’ (Ibid).

To further contest the claim that moral hazard is ‘only’ or ‘mostly’ something theoretical, German central bankers often refer to moral hazard as a type of phenomenon – ‘Die Moral Hazard Phänomen’ – and provide concrete examples:

‘At the microeconomic level, it is above all wrongly set incentives that contributed to the emergence of the financial crisis, be it due to a lack of transparency, inadequate regulatory frameworks or the phenomenon of moral hazard so familiar to us economists’ (authors’ translation; Weber Citation2009, 3).

‘The dramatic waning of enthusiasm for reform on the part of the Berlusconi government following SMP purchases of Italian government bonds shows how quickly a country’s will to reform can evaporate when budget constraints are eased’ (Weidmann Citation2015a, 6).

Another discursive device used by Bundesbank officials to strengthen their positions and challenge alternatives is to emphasize the credibility (or lack thereof) of different policy options. When it comes to moral hazard, credibility appears as a crucial criterion to assess the efficiency of proposals. Bundesbank officials often present alternative positions as unbelievable and inefficient:

‘However, since failure still cannot be ruled out entirely, minimising moral hazard ultimately requires a system that allows an orderly restructuring of SIFIs. Only then will it be possible to credibly bail-in investors and thus impose the necessary market discipline on SIFIs’ (Weber Citation2011, 5).

‘There is a nice aphorism on this issue by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the author of The Black Swan: “The main difference between government bailouts and smoking is that in some rare cases the statement ‘this is my last cigarette’ holds true”. […] Governments might promise to refrain from bailouts in order to prevent moral hazard behaviour. But when financial stability is at stake, they have an incentive to deviate from their previous commitment’ (Weidmann Citation2016, 3).

In addition to the argument constructed around the question of credibility, Bundesbank policymakers often frame their positions as being fair in terms of distribution of costs and benefits:

‘As a key requirement, a new regime would have to allow supervisors to choose restructuring over bailing-out and thus avoid unfair burden sharing and moral hazard’ (Weber Citation2010, 8).

‘And as Governor Carney said last year in Davos: “To make the system fairer, the days when banks privatised gains but socialised losses must end”’ (Weidmann Citation2015b, 8).

Bundesbank officials also tend to frame their positions as prudent, placing great value on the fact of being cautious or vigilant when dealing with moral hazard:

‘That is why discretionary scope needs to be used responsibly. Exceptions should be confined to rare, clearly defined instances. Otherwise, the seeds of growing risk in the future would be sown under the guise of protecting systemic stability’ (Buch Citation2014, 5).

‘But what happens in the transitional phase if, during the build-up phase, the resolution fund needs larger funds for resolution after the bail-in? For this case too there must be a plan B’ (Nagel Citation2014, 7).

Finally, Bundesbank officials also construct the legitimacy of their positions by reference to conformity to past and guiding principles, notably ordoliberal ones, and frame alternative positions as contrary to such fundamental principles:

‘This requires preserving the cornerstones on which the European Monetary System is based: the principle of a country’s own financial responsibility (no bail-out) and, in order to safeguard confidence in stability, the requirement that the central bank refrain from monetary government financing, i.e. the financing of government tasks and deficits by the central bank’ (authors’ translation; Zeitler Citation2011, 15).

‘This implicit state insurance, however, invalidates a fundamental principle of the market economy. A principle that Walter Eucken summed up in one sentence: “who has the benefit must also bear the cost”. This principle of liability is the basis of a functioning market economy. If it does not apply, the behaviour of actors changes and moral hazard arises’ (authors’ translation; Dombret Citation2014, 3).

In parallel to discursive strategies aimed at constructing arguments and the legitimacy of positions, Bundesbank officials also employ strategies to construct in-groups and out-groups and to label social actors more or less positively or negatively. For example, Bundesbank officials refer to a group of ‘knowledgeable economists’ (Bundesbank Quotes 7). In particular, moral hazard is described as something well-known by economists – thus creating a distinction between ‘knowledgeable economists’ versus others and implying a consensus among credible economists on moral hazard. At times, Bundesbank officials emphasize their membership in this group of economists, a strategy that aims to weaken alternative positions by implicitly stating that they are based on ignorance:

‘[…] or the phenomenon of moral hazard so familiar to us economists’ (authors’ translation; Weber Citation2009, 3).

‘Economists call this phenomenon moral hazard’ (authors’ translation; Dombret Citation2012, 2).

Finally, Bundesbank officials also frequently mention ‘taxpayers’, which are labelled as innocent victims.Footnote6 By framing their positions as a means to protect taxpayers, they construct legitimacy and strengthen their positions:

‘First, the costs of stabilisation are not borne by those who caused the crisis but by the taxpayers (although there might be a certain overlap, of course)’ (Weber Citation2010, 3).

‘The objective of regulatory reforms, then, is not to upset the financial industry, but to strengthen the resilience of the banking sector and to prevent the taxpayer from bailing out banks in the future — which is in my view crucial for the public support of our market economy’ (Weidmann Citation2016, 3).

Conclusion

Our text analysis and the material from the interviews demonstrate that the precise meaning of moral hazard is contested and that there is a certain professional dissensus about the concept of moral hazard in EU central banking. We found that for Bundesbank officials moral hazard is often something close to: ‘the risk that SIFIs may take more risks, in response to financial sector characteristics and activities that reduces the exposure to consequences and violates the principle of liability, which poses a problem of social justice, and that requires a selection of which actors are worthy of support’. In the case of the ECB, we found that moral hazard is often something close to: ‘the risk that banks take excessive risks, in response to public intervention that reduces the exposure to consequences, which poses a problem of market efficiency, and that requires conditional support’. These reconstructed definitions are indicative of different properties to qualify something as moral hazard. In particular, Bundesbank officials tend to label ‘moral hazard’ situations where the possibility of increased risk-taking arise, while ECB officials tend to label as moral hazard situations where excessive risks have been taken. This difference is crucial because it changes the universality of moral hazard: in the case of the ECB, moral hazard is presented as something more restricted than in the case of the Bundesbank. As a conclusion, it is also worth stressing that, contrary to ECB officials, central bankers from the Bundesbank emphasized the securitization of credit risk as a cause of moral hazard. This might be interpreted as a sign that German central bankers were less complacent with regard to the financial sector and more inclined to blame the financial sector for the international financial crisis than central bankers from the ECB.

In our review of discursive strategies, we found common and specific strategies: in both cases, despite defending opposed positions, conformity to academic knowledge and continuity with the past is claimed by central bankers. While ECB officials tended to emphasize the complexity of the social world and the value of moderate positions; Bundesbank officials tended to emphasize the value of credible, prudent, and fair positions. Moreover, while ECB officials tended to minimize the risk of moral hazard and to present it as something mostly theoretical, central bankers from the Bundesbank tended to exaggerate moral hazard and to present it as an empirical phenomenon. The analysis of positions and discursive strategies on moral hazard presents evidence of a ‘battle of ideas’ between top Bundesbank and ECB officials.

The empirical analysis of how Bundesbank and ECB officials understood and made use of the moral hazard concept with regard to Banking Union-related issues provides evidence in favour of our hypothesis: we found elements to conclude that there is a professional dissensus on what moral hazard is and that a discursive battle between Bundesbank and ECB officials to influence the beliefs of others in relation to moral hazard and Banking Union took place. Moral hazard is not a technical concept but a political one: its meaning is contested and appears to stem from distinct influences of ordoliberal ideas and different institutional interests and preferences on the construction of Banking Union. The power of the moral hazard concept in this context of central bank positioning on Banking Union does not lie in an ideational professional consensus but rather in its ambiguity which can serve to promote different preferences and specifically the Bundesbank’s caution on and the ECB’s stronger support for the construction of Banking Union. The different use of the moral hazard concept also demonstrates an important development in the politics of central banking in the Eurozone, and specifically how the Bundesbank and the ECB have grown apart in their conceptions of what the role of a central bank should be.

Interviews

Bundesbank official, Frankfurt am Main, 24 March 2022.

ECB official, online via WebEx, 22 March 2022.

ECB official, online via WebEx, 25 March 2022.

ECB official, online via WebEx, 25 March 2022.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors benefitted from the feedback of academic colleagues and practitioners participating in the 12-13 May 2022 workshop ‘The Politics, Law and Political Economy of European Banking Union’ at the University of Luxembourg. Funding for this workshop came in part from the Erasmus+ programme and the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence/Robert Schuman Initiative at the University of Luxembourg. Funding for the research that resulted in this publication came from David Howarth’s CORE project funded by the Luxembourg Fonds National de la Recherche: C19/IS/13712846/BEEBS/. We would also like to thank the University Association for Contemporary European Studies (UACES) and the James Madison Charitable Trust for their generous doctoral research travel grant which in part funded Laura Pierret to conduct the interviews referenced in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2022.2156501

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The data was collected in mid-October 2021.

2. The website of the Bundesbank allows for a topical search: the topics of ‘banking supervision’ and ‘financial stability’ were selected. In the case of the ECB, the topical selection was made through a keyword search (i.e. ‘banking supervision’ and ‘financial stability’) in the dataset of all speeches from 01.01.2007, with an occurrence of moral hazard.

3. The six Bundesbank officials were: Dombret, Weber, Weidmann, Buch, Zeitler and Nagel. The fourteen ECB officials were: Trichet, Draghi, Papademos, Schnabel, Praet, Constancio, Coeuré, Gonzáles-Paramo, Asmussen, Bini Smaghi, Stark, Tumpel-Gugerell, Mersch, and Lautenschläger. Four of the ECB officials (Schnabel, Asmussen, Stark and Lautenschläger) were Germans.

4. Disclaimer: the interviews represent the interviewees’ personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the central bank.

5. This result applies specifically to the topics of the selected documents (i.e. banking supervision and financial stability).

6. ‘Taxpayers’ as a group are also present in ECB speeches but appear with greater relative frequency in Bundesbank speeches.

References

- Arrow, K. 1963. “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care.” The American Economic Review 53 (5): 941–973.

- Asmussen, J. 2012. ‘Stability Guardians and Crisis Managers: Central Banking in Times of Crisis and Beyond’, Distinguished Lecture delivered at the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, 11 September; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120911.en.html

- Bini Smaghi, L. 2010. “ ECON Committee Hearing on Improving the Economic Governance and Stability Framework of the Union, in Particular in the Euro Area,” Intervention, Brussels, 15 September; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2010/html/sp100915.en.html

- Bini Smaghi, L. 2011a. “Policy Rules and Institutions in Times of Crisis”, Speech Delivered at the Forum for EU-US Legal Economic Affairs, Rome, 15 September; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp110915.en.html

- Bini Smaghi, L. 2011b. “Whither Europe after the Crisis?”, Speech delivered at the inauguration of the Academic Year 2011 IMT, Lucca, 11 March; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp110311.en.html

- Blyth, M. 2013. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bonatti, L., and A. Fracasso. 2013. “The German Model and the European Crisis.” Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (6): 1023–1039. doi:10.1111/jcms.12067.

- Buch, C. 2014. “Presentation of the 2014 Financial Stability Review”, Speech Delivered at the Unveiling of the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Financial Stability Review, Frankfurt, 25 November; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/presentation-of-the-2014-financial-stability-review-666642

- Bulmer, S. 2014. “Germany and the Eurozone Crisis: Between Hegemony and Domestic Politics.” West European Politics 37 (6): 1244–1263. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.929333.

- Carstensen, M., and V. Schmidt. 2016. “Power Through, over and in Ideas: Conceptualizing Ideational Power in Discursive Institutionalism.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 318–337. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534.

- Coeuré, B. 2013. “Monetary Policy and Banking Supervision”, Speech Delivered at the Symposium: Central Banking: Where are We Headed?, Frankfurt, 7 February; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2013/html/sp130207.en.html

- Coeuré, B. 2014. “Investing in Europe: Towards a New Convergence Process”, Speech delivered at the Economist Roundtable with the Government of Greece, Athens, 9 July; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140709.en.html

- Constâncio, V. 2011a. “The Governance of Financial Stability in the Euro Area”, Speech delivered at the “ECB and its Watchers XIII” conference, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, 10 June; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp110610_1.en.html

- Constâncio, V. 2011b. “A European Solution for Crisis Management and Bank Resolution”, Speech delivered at Riksbank and ECB Conference on Bank Resolution, Stockholm, 14 November; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp111114.en.html

- Constâncio, V. 2016a. “Presentation of the ECB Annual Report 2015 to the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament”, Introductory remarks, Brussels, 7 April; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2016/html/sp160407_1.en.html

- Constâncio, V. 2016b. “Challenges for the European Banking Industry”, Lecture delivered at the Conference on “European Banking Industry: what’s next?” organized by the University of Navarra, Madrid, 7 July; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2016/html/sp160707_1.en.html

- Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 of 15 October 2013 “Conferring Specific Tasks on the European Central Bank Concerning Policies Relating to the Prudential Supervision of Credit Institutions (2013) OJ L”. Available at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/1024/oj/eng (Accessed 18 October 2022).

- Crespy, A., and P. Vanheuverzwijn. 2019. “What ‘Brussels’ Means by Structural Reforms: Empty Signifier or Constructive Ambiguity?” Comparative European Politics 17 (1): 92–111. doi:10.1057/s41295-017-0111-0.

- Dam, L., and M. Koetter. 2012. “Bank Bailouts and Moral Hazard: Evidence from Germany.” The Review of Financial Studies 25 (8): 8. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhs056.

- De Grauwe, P. 2011. “A Less Punishing, More Forgiving Approach to the Debt Crisis in the Eurozone.” CEPS Policy Brief, no. 230.

- Dombret, A. 2012. “Aktuelle Aspekte der Finanzstabilität: Neue Abwicklungsregeln Für Banken”, Rede im Institut für Kreditwesen anlässlich der Münsteraner Bankentage 2012, Münster, 21 May; available 21 May 2012 at https://www.bundesbank.de/de/presse/reden/aktuelle-aspekte-der-finanzstabilitaet-neue-abwicklungsregeln-fuer-banken-710658

- Dombret, A. 2014. “Das Streben nach Stabilität Regeln und Märkte im Spiegel der Krise”, Rede beim Münchner Seminar des ifo-Instituts, Munich, 27 January; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/de/presse/reden/das-streben-nach-stabilitaet-regeln-und-maerkte-im-spiegel-der-krise-710744

- Dombret, A. 2018. “Now or Later? Completing the European Banking Union”, Lecture delivered at the Graduate Institute Geneva, Geneva, 20 February; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/now-or-later-completing-the-european-banking-union-711604

- Draghi, M. 2019. “Policymaking, Responsibility and Uncertainty”, Acceptance Speech for the Laurea Honoris Causa from the Università Cattolica, Milan, 11 October; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2019/html/ecb.sp191011~b0a4d1e7c5.en.html

- Dyson, K. 1994. Elusive Union. London: Addison-Wesley Longman.

- Dyson, K. 2000. The Politics of the Euro-Zone: Stability or Breakdown? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dyson, K. 2010. “German Bundesbank: Europeanization and the Paradoxes of Power.” In Central Banks in the Age of the Euro, edited by K. Dyson and M. Marcussen, 131–160. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dyson, K. 2014. States, Debt, and Power: ‘Saints’ and ‘Sinners’ in European History and Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dyson, K. 2021. Conservative Liberalism, Ordo-liberalism, and the State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dyson, K., and K. Featherstone. 1999. The Road to Maastricht. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Epstein, R., and M. Rhodes. 2016. “The Political Dynamics behind Europe’s New Banking Union.” West European Politics 39 (3): 415–437. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1143238.

- González-Páramo, J M. 2008. “Whither Liquidity? Developments, Policies and Challenges’, Speech Delivered at the ECB 28th” Nomura Central Bankers Seminar, Tokyo, 14 April; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2008/html/sp080414.en.html

- González-Páramo, J. 2009a. “Financial Market Failures and Public Policies: A Central Banker’s Perspective on the Global Financial Crisis”, Speech delivered at the XVI Meeting of Public Economics, Granada, 6 February; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp090206.en.html

- González-Páramo, J M. 2009b. “Managing Risk: The Role of the Central Bank in a Financial Crisis”, Speech delivered at Risk Europe 2009, Frankfurt, 4 June; available 4 June 2009 at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp090604.en.html

- Hallerberg, M. 2014. “Why Is There Fiscal Capacity but Little Regulation in the US, but Regulation and Little Fiscal Capacity in Europe? the Global Financial Crisis as a Test Case.” In Beyond the Regulatory Policy? the European Integration of Core State Powers, edited by P. Genschel and M. Jachtenfuchs, 87–104. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hay, C., and B. Rosamond. 2002. “Globalization, European Integration and the Discursive Construction of Economic Imperatives.” Journal of European Public Policy 9 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1080/13501760110120192.

- Holmström, B. 1979. “Moral Hazard and Observability.” The Bell Journal of Economics 10 (1): 74–91. doi:10.2307/3003320.

- Howarth, D. 2004. “The ECB and the Stability Pact: Policeman and Judge?” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (5): 832–853. Spring. doi:10.1080/1350176042000273568.

- Howarth, D. 2007. “Running an Enlarged euro-zone – Reforming the European Central Bank: Efficiency, Legitimacy and National Economic Interest.” Review of International Political Economy 14 (5): 820–841. doi:10.1080/09692290701642713.

- Howarth, D. 2012. “Unity and Disunity among Central Bankers in an Asymmetric Economic and Monetary Union.” In European Disunion: The Multidimensional Power Struggles, edited by J. Hayward and R. Wurzel, 131–145. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Howarth, D., and P. Loedel. 2005. The ECB: The New European Leviathan. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Howarth, D., and L. Quaglia. 2016. The Political Economy of European Banking Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howarth, D., and C. Rommerskirchen. 2013. “A Panacea for All Times: The Politics of the German Stability Culture.” West European Politics 36 (4): 750–770. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.783355.

- Jabko, N. 2006. Playing the Market: A Political Strategy for Uniting Europe, 1985-2005. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Lane, T., and S. Phillips. 2000. “Does IMF Financing Result in Moral Hazard?” IMF Working Paper, no. 00/168.

- Lautenschläger, S . 2014. “Banking Supervision – A Challenge”, Speech Delivered at the Deutsches Institut Für Wirstchaftsforschung, 8 September, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. Hamburg. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2014/html/sp140908.en.html

- Leaver, A. 2015. “Fuzzy Knowledge: An Historical Exploration of Moral Hazard and Its Variability.” Economy and Society 44 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1080/03085147.2014.909988.

- Marsh, D. 1992. The Bundesbank: The Bank that Rules Europe. London: Heinemann.

- Matthijs, M., and K. McNamara. 2015. “The Euro Crisis’s Theory Effect: Northern Saints, Southern Sinners, and the Demise of the Eurobond.” Journal of European Integration 37 (2): 229–245. doi:10.1080/07036337.2014.990137.

- McNamara, K. 1998. The Currency of Ideas: Monetary Politics in the European Union. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Mersch, Y. 2016. “Grasping the New Normal of Banking Industry – A View from a European Central Banker”, Speech delivered at the European Financial Congress, Sopot, 14 June; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2016/html/sp160614.en.html

- Nagel, J. 2014. “Europäische Bankenunion: Ein neues Kapitel der Bankenaufsicht”, Rede bei der Stiftung Kreditwirtschaft der Universität Hohenheim, Stuttgart, 16 January; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/de/presse/reden/europaeische-bankenunion-ein-neues-kapitel-der-bankenaufsicht-710740

- Noy, I. 2008. “Sovereign Default Risk, the IMF and Creditor Moral Hazard.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money 18 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2006.06.001.

- Praet, P. 2012. “Monetary Policy at Crisis Times”, Lecture delivered at the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, 20 February; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120220.en.html

- Reisigl, M., and R. Wodak. 2000. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Anti-Semitism. London: Routledge.

- Schäfer, D. 2016. “A Banking Union of Ideas? the Impact of Ordoliberalism and the Vicious Circle on the EU Banking Union.” Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (4): 961–980. doi:10.1111/jcms.12351.

- Siems, M., and G. Schnyder. 2014. “Ordoliberal Lessons for Economic Stability: Different Kinds of Regulation, Not More Regulation.” Governance 27 (3): 377–396. doi:10.1111/gove.12046.

- Stiglitz, J. 1983. “Risk, Incentives and Insurance: The Pure Theory of Moral Hazard.” The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 8 (26): 4–33. doi:10.1057/gpp.1983.2.

- Trichet, J-C. 2009. ‘Systemic Risk’, Clare Distinguished Lecture Delivered at the, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, 10 December; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp091210_1.en.html

- Trichet, J-C. 2010. “What Role for Finance?”, University lecture delivered at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, 6 May; https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2010/html/sp100506.en.html

- Tumpel-Gugerell, G. 2011. “Asset Price Bubbles: How They Build up and How to Prevent Them?”, Speech delivered at the alumni event of the Faculty of Economics at the University of Vienna, Vienna, 3 May; available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2011/html/sp110503.en.html

- Van Leeuwen, T. 1996. “The Representation of Social Actors.” In Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by C.R Caldas-Coulthard and M. Coulthard, 32–70. London: Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T. 2007. “Legitimation in Discourse and Communication.” Discourse & Communication 1 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1177/1750481307071986.

- Wasserfallen, F., D. Leuffen, Z. Kudrna, and H. Degner. 2019. “Analysing European Union Decision-Making during the Eurozone Crisis with New Data.” European Union Politics 20 (1): 1. doi:10.1177/1465116518814954.

- Weber, A. 2008. “‘Risk Transfer: Challenges for Financial Institutions and Markets’ Dinner Speech at the Joint Bundesbank-CEPR-CFS Conference ”, Frankfurt, 11 December; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/702734/53e83cd15a434c858a525a4b88a6bcd2/mL/2008-12-11-weber-dinner-speech-at-joint-bundesbank-cepr-cfs-conference-download.pdf

- Weber, A. 2009. “Finanzmarktkrise – Herausforderung für die Wirtschaftswissenschaften?”, Constance, 16 October; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/688944/368e73e844320ecddd60781a4f8ccdfb/mL/2009-10-16-weber-finanzmarktkrise-herausforderung-fuer-die-wirtschaftswissenschaften-download.pdf

- Weber, A. 2010. “Making the Financial System More Resilient – The Role of Capital Requirements”, Speech delivered at Financial Services Ireland, Dublin, 10 March; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/702758/d095510830e7494673158f0cce72fb73/mL/2010-03-10-weber-role-of-capital-requirements-download.pdf

- Weber, A. 2011. “Lessons Learnt: The Reform of Financial Regulation and Its Implications”, Speech delivered at the UCL Economics and Finance Society, London, 10 March; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/702802/3fffb0f26b568fa26d2ee1c65515b408/mL/2011-03-10-weber-reform-of-financial-regulation-download.pdf

- Weidmann, J. 2015a. “Financial Market Integration from a Central Banking Perspective”, Speech delivered at Eurörsentag 2015, Frankfurt, 23 July; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/financial-market-integration-from-a-central-banking-perspective-666892

- Weidmann, J. 2015b. “Heading for Stability and Prosperity – Bringing the Euro Area Back on Track”, Keynote speech given at the City of London Corporation, London, 12 February; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/heading-for-stability-and-prosperity-bringing-the-euro-area-back-on-track-666722

- Weidmann, J. 2016. “Dinner Speech”, Delivered at the 6th Frankfurt Finance Summit, Frankfurt, 11 May; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/dinner-speech-667106

- Weidmann, J. 2017. “The Financial Crisis, Then Years on – What Have We Learned?”, Speech delivered at Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, 22 May; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/the-financial-crisis-ten-years-on-what-have-we-learned–667372

- Zeitler, F-C. 2011. “Stärkung des Vertrauens – Was bleibt nach Basel III zu tun?”, Speech, Munich 5 April; available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/689062/363f7aee33cd2997bc8ca6a0139a8de6/mL/2011-04-05-zeitler-was-nach-basel-iii-zu-tun-ist-download.pdf