ABSTRACT

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine sent shockwaves through Europe and led to rapid policy changes concomitant with variations in citizen perceptions. This article analyses how EU public opinion on security and defence matters has reacted to the war: what patterns of change and continuity can be detected, what differences are visible between Member States, and how might those be explained? Our analysis draws on big data-based sentiment analysis of news sources, reflecting a widely recognized connection between media coverage and public opinion – especially during crisis times – and complementing more traditional measurements of citizen perceptions such as opinion polls. Broadly speaking, we find that the invasion has heightened rather than fundamentally altered underlying trends. Our article contributes to a growing literature on the acceptability of European integration in security and defence, showing that publics are generally supportive of it, and regard it as complementary to NATO.

1. Introduction

As European integration has deepened, public opinion on the EU has increasingly come into the spotlight. Yet when it comes to the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), further research into public acceptability of integration is still needed (Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra Citation2021; Michaels and Kissack Citation2021). After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, filling this gap has become even more imperative. Preliminary survey research has shown that the invasion has accelerated a shift in perceptions that was already underway, with publics increasingly expressing their anxiety about European security and perceiving the world as being ‘in a pre-war rather than post-war state’ (Krastev and Leonard Citation2022).

Given that sentiment analysis of media outlets has been found to be especially informative during crises and historical turning points (Herbst Citation1998; Kepplinger Citation2007), in this article, we turn to big data-based analysis of security-related news to study the run-up to and immediate aftermath of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Our analysis thus complements more traditional measurements of citizens’ perceptions, such as opinion surveys, and ultimately contributes to the growing body of literature on public opinion and acceptability in the EU.

This study examines the impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine on the volume and tone of security-related news in the EU and its Member States, contemplating several potential explanations for variations in these effects, based on geographical and historical factors. We examine in detail a number of EU Member States, including those that have made historical changes to their security and defence policies following the invasion (i.e. Finland, Sweden and Denmark).

We find that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a watershed moment for public perceptions of EU security and defence, but rather than overturning existing trends, the invasion has accelerated many of them. Our results confirm there is broad acceptability among the public for EU efforts in security and defence. Although baseline support was already high, the Russian invasion has driven significant increases in CSDP support among many Member States, including most Russia-bordering countries, as well as several traditionally neutral or otherwise reluctant Member States.

This article commences by examining the literature on EU integration and politicization in CFSP and CSDP, the use of media to understand public opinion, and determinants of national perceptions of CSDP. Section three explains the data and methods employed, while section four describes the results. These findings and their implications are discussed in detail in section five, which also includes reflections on limitations and future research avenues. A final section wraps up with conclusions.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Integration and politicisation in CFSP and CSDP

Interest in the role of public opinion in EU integration has increased progressively since the first direct elections to the European Parliament in 1979. Previously perceived as an elite-driven project, the EU has undergone a remarkable process of politicisation at the public level. However, in their seminal article on the shift from a ‘permissive consensus’ to a ‘constraining dissensus’ in European integration, Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) do not deal with the external dimension of its main levers (e.g. trade liberalisation via the single market), nor with the EU’s CFSP. Following a neofunctionalist understanding of politicisation (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009, 6), it may be argued that CFSP in particular – and even more so the narrower CSDP, which is the focus of this article – has not reached a sufficient degree of integration for public opinion to come into play (De Wilde and Zürn Citation2012; Grande and Hutter Citation2016; Zürn Citation2014).

One alternative explanation for the omission of CFSP from discussions on the shift from a ‘permissive consensus’ to a ‘constraining dissensus’ is based on a different logic: in sensitive issues of foreign policy, a constraining dissensus was inherently present from the outset, thus preventing integration in the first place. In a nutshell, ‘the “permissive consensus” … never applied to CFSP’, at least in the sense that ‘political conflict has always been part of CFSP’ (Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra Citation2021, 325–326). This view echoes some of the basic tenets of liberal intergovernmentalism, which pays scant attention to public opinion, but explains the relatively slow progress in constructing a truly ‘European’ foreign policy through state preferences shaped by key national stakeholders.

Much research has been conducted on EU Member States’ tendency to keep their cards close to their chest in matters concerning security and defence, their reluctance to pool resources and their difficulties in nurturing a shared strategic culture (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen, and Rittberger Citation2015; Schmidt and Zyla Citation2011). NATO membership has often been regarded as a substitute for strong EU cooperation on security and defence, leaving the EU to concentrate on market integration (Damro Citation2012) and take external security largely for granted.

However, proponents of further EU security and defence integration appear to have the wind in their sails. Schilde, Anderson, and Garner (Citation2019) find that ‘pooling national sovereignty over defence is more popular over time than any other EU-level policy’ (155), and they speculate that ‘Europeans may be more supportive of the use of force at the European than the national level’ (166). The authors even claim that this favourable stance ‘is based on knowledge about the consequences and costs of such policy’ (165). This suggests that not only is there no constraining dissensus regarding joint EU efforts in this realm, but deep support that goes well beyond an uninformed permissive consensus, even if the issue area is not highly salient on a day-to-day basis. It would seem, therefore, that politicisation does not necessarily imply major contestation, and can be conducive to ‘more integrated institutional practices and policies, particularly in security and defence’ (Barbé and Morillas Citation2019, 754; see also Beck and Grande Citation2007; Wiener Citation2014).

Several recent articles and edited volumes address the domestic politicisation and contestation of EU external action more broadly (Costa Citation2019; Góra, Styczyńska, and Zubek Citation2019; Johansson-Nogués, Vlaskamp, and Barbé Citation2020; Müller, Pomorska, and Tonra Citation2021; Thomas Citation2021). However, Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra (Citation2021, 339) observe that ‘research on the contestation and politicisation of EU foreign policy as well as security and defence cooperation is in its infancy’ (see also Michaels and Kissack Citation2021). At a critical moment when the EU faces the return of inter-state warfare to the European continent, it is even more essential to devote our attention to this dimension of acceptability.

2.2. Media and public opinion

According to Michaels and Kissack (Citation2021, 15), ‘a combination of public beliefs and perceptions can be evaluated by looking at opinion polls or the framing of policy issues by the media, campaign groups and epistemic communities’. These proposed methods are similar to the four types of data suggested by Kepplinger (Citation2007, 12) to estimate public opinion: polls, media reports, expert analysis and the impressions people retain from their discussions with others. Media are particularly relevant during crisis times:

People who generally mistrust the validity of opinion polls, those without regular access to opinion polls, and those facing the beginning of a crisis rely first and foremost on media coverage to make estimates about public opinion (Herbst Citation1998). Thus, media coverage can act as a surrogate for public opinion

Ample literature supports the existence of a strong link between media coverage and public opinion (Entman Citation1993; McCombs and Shaw Citation1972). Eurobarometer data also demonstrate that television, internet websites, radio and the written press – in that order – are the public’s preferred news sources for European political matters (European Commission Citation2021c, 49). Although the emergence of online social networks has been remarkable, only a relatively low percentage of Europeans (23%) list them as one of their favoured sources (European Commission Citation2021c, 49).

At the same time, some EU Member States are experiencing a decline in media freedom, while critical, independent sources remain considerably active. This evolution may weaken the impact of traditional news media in favour of online social networks. In fact, the six worst-performing EU countries in the latest World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (Citation2022) – from better to worse, Cyprus, Poland, Malta, Hungary, Bulgaria and Greece – exhibit the same feature: their populations mention online social networks among their preferred sources to follow European political matters much more often than the EU average (European Commission Citation2021c, 54). However, it is still almost always a minority of these populations that list social media among their favoured sources.Footnote1 This seems to support the claim that social media has not eroded the agenda-setting role of traditional news media (McCombs and Valenzuela Citation2021).

2.3. National determinants of CSDP perceptions

Significant variations in public opinion across Member States may form stumbling blocks in EU security and defence integration. Interrelated factors such as geographical location, historical legacy and neutrality status determine perceptions of insecurity and strategic cultures (Biehl, Giegerich, and Jonas Citation2013), which in turn impact the acceptability of both national policies (e.g. defence spending) and EU initiatives (e.g. CSDP missions and operations).

Historical and geographical proximity to Russia stands out as a key variable. Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, many EU Member States that used to be part of the Soviet Union or its sphere of influence felt vindicated in their narratives and predictions about Russian behaviour (Daniel and Eberle Citation2021). Understandably, countries sharing a land border with RussiaFootnote2 – perhaps chief among them, Poland and the Baltic states (Lau Citation2022; Orenstein Citation2023) – have always expressed greater concerns about the risk of overt Russian aggression, as well as other forms of Russian interference. However, sensitivities differ, not just between East and West but between former Warsaw Pact members, and even between Russia-bordering countries more specifically – a group that comprises the sui generis case of Finland, a traditionally neutral country.

A foreign policy based on neutrality – which after World War II was maintained or adopted by Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden – has been found to have a sizeable negative effect on support for CFSP and CSDP (Peters Citation2014; Schoen Citation2008). Nevertheless, the origin (self-imposed or coerced), legal codification, practices and societal perceptions of neutrality differ widely. In many Member States, the principle of neutrality has started to lose ground, to varying degrees. Sweden and Finland saw a shift from broader neutrality to a narrower policy of ‘military non-alignment’, construed as non-membership of mutual defence alliances (Beyer and Hofmann Citation2011). This status has also been effectively abandoned as a result of their respective NATO applications on 18 May 2022. More generally, traditionally neutral Member States have found various ways to accept and live with the inclusion of a mutual defence clause in Article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union (Cramer and Franke Citation2021), while also overcoming many of their objections to the advancement of the EU’s CSDP (Beyer and Hofmann Citation2011; Devine Citation2011). Denmark, a non-neutral and staunchly Atlanticist country, was in fact the only one to opt out of CSDP (Pedersen Citation2006). However, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered a referendum in Denmark on 1 June 2022, in which voters decided to abolish the opt-out.

3. Methods

In this study, we rely on big data-based sentiment analysis to examine citizen perceptions through news media. Especially since the turn of the century, there has been an increase in the application of quantitative, automated sentiment analysis to large corpora of texts, often in conjunction with qualitative methods of Critical Discourse Analysis applied to small text samples (Smirnova, Laranetto, and Kolenda Citation2017). Scholars have used sentiment analysis to infer public opinion on recent crises in specific EU countries (Backfried and Shalunts Citation2016), as well as to analyse official rhetoric and strategic documents on security and defence (Gavras, Mader, and Schoen Citation2022; Molnár and Takács Citation2021). However, to our knowledge, no study had previously relied on sentiment analysis of news media to comprehensively research crises-induced changes in public perceptions of CFSP/CSDP. This research design holds vast potential as a time-sensitive, cost-effective and – in our article’s case – big data-based complement to opinion polls and surveys (see Chaban and Elgström Citation2023).

In order to examine citizen perceptions through news media, we utilized the open-access Global Database of Events, Language and Tone (GDELT). GDELT collects data from more than 150,000 news sources, in over 100 languages, which are machine-translated into English (Guo and Vargo Citation2017; Leetaru, Perkins, and Rewerts Citation2014). News items are machine-coded to identify their tone, location, theme, source and actors, among others. Since the advent of event studies in the late 1970s, important progress has been made in the use of this type of data. The speed of machine coding (Gerner et al. Citation1994) has enhanced its attractiveness, while natural language processing – and its application to discursive analysis – has made hard-to-measure variables easier to capture (Alker et al. Citation1991). Moreover, automated coding has been proven to perform better than subject-matter experts, given that the former covers a far larger amount of information than that which an individual can process (King and Lowe Citation2003).Footnote3 In terms of accuracy, machine coding has been shown to be comparable to human coding (King and Lowe Citation2003; Schrodt Citation2010).

For this study, we drew on GDELT to create a new dataset spanning the period from 3 November 2021, to 1 May 2022. The bottom limit captures the run-up to the Russian invasion: although troop movements had taken place before this date, on November 3, the Ukrainian Defence Ministry confirmed the presence of 90,000 Russian troops near the Ukrainian border, thus marking the beginning of the final escalation (Reuters, November 3, 2021). The upper limit was fixed at the day of commencing the analysis. To explore public opinion on the EU’s CSDP in each Member State, we extracted data on all news coded with the theme ‘National security’ as per the Economic Policy Uncertainty Taxonomy.Footnote4 Missing values were replaced by zeros for volume, and by the previous day’s value for tone. Thereafter, from this initial extraction, we created a subset of news items on security that mention the EU, by using a free-text search to separate out the news items including within their text any of the following terms: ‘the EU’, ‘European Union’, ‘European Commission’, ‘European Parliament’, ‘European Council’, ‘European Defence Agency’, ‘the EDA’, ‘European External Action Service’ and ‘the EEAS’.Footnote5

We thus generated two datasets (one full, covering all news on security in all 27 Member States; and one subset, covering all news on security mentioning the EU in all 27 Member States) that represent the full population of news over the time period covered. For both of these, we extracted the total number of daily news items (which we refer to as ‘volume’) and the average tone used in those news items each day (‘tone’). Regarding volume, we are not counting events but news items: hence, the same event may be (and often is) reported on more than once by different news sources. Regarding tone, this value represents the average sentiment in the daily news items, as coded through GDELT’s own algorithm.Footnote6 We furthermore calculated the difference between the tones of all security news, on the one hand, and security news including the EU, on the other. This value, which we call ‘tone differential’, reveals which of the two datasets is more positive or negative in tone and to what extent. For both datasets, we extracted volumes, tones and tone differentials for the news published in individual Member States.

In order to gauge the effects of potential national determinants of public opinion for the period under study, we hand-coded and constructed variables based on whether a Member State shares a border with Russia, as well as on its relationship with the main pillars of Euro-Atlantic security: CSDP and NATO.Footnote7 These variables combine into five different categories of Member States (leaving aside the 16 countries belonging to a baseline category labelled as ”EU-rest”), which are shown in and are used to structure the subsequent analysis. Three of these categories are made up of single countries, reflecting their respective characteristics prior to the invasion: Finland, Sweden and Denmark. In what follows, we refer to the other two categories as ‘neutral EU countries’ (G1) and ‘Russia-bordering EU and NATO members’ (G2).

Table 1. Categories of EU Member States based on our selected variables.

4. Results

4.1. News volume before and after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

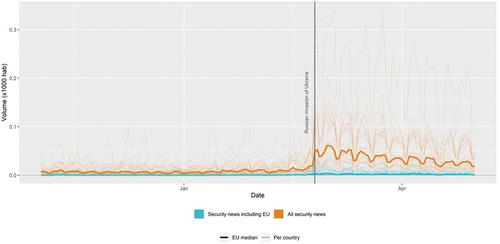

shows the population-weighted volume of all security news, as well as security news including mentions of the EU, from 3 November 2021 to 1 May 2022. We can observe a clear increase in news volume around the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Despite following a slight downward trend since the invasion date, the volume post-invasion is significantly higher than the volume pre-invasion.Footnote8 This is true both for all security news and for the subset of security news mentioning the EU – which represent a relatively small portion of the total. There is a large degree of variation between Member States, which we explore further below.

Figure 1. Volume per 1000 inhabitants of security news, by Member State and across the EU (November 2021-May 2022).

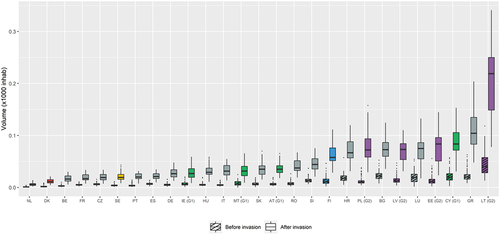

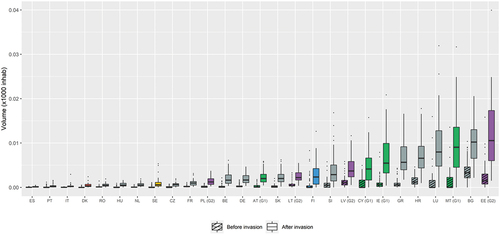

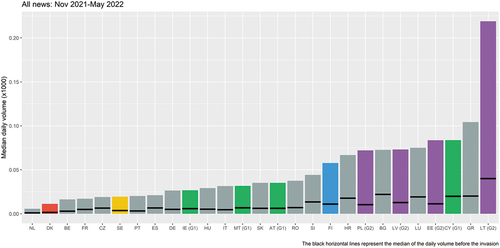

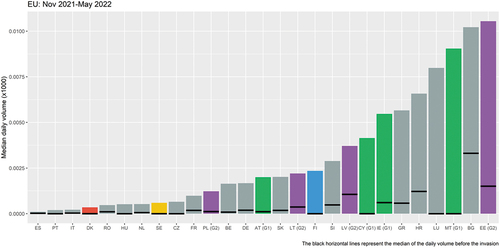

The two following figures present the population-adjusted volume per country of all news articles on security () and those mentioning the EU (). Member States are ordered by their median population-adjusted volumes after the invasion (from small to large), represented in columns. Within each column, the black horizontal lines represent the median pre-invasion volume in each Member State.Footnote9 Columns are colour-coded to reflect the country categories in . As both figures show, news volumes increase after the invasion in every country – often notably.

Figure 2. Daily volume per 1000 inhabitants of all news on security, before and after the invasion, by EU Member State.

Figure 3. Daily volume per 1000 inhabitants of news on security mentioning the EU, before and after the invasion, by EU Member State.

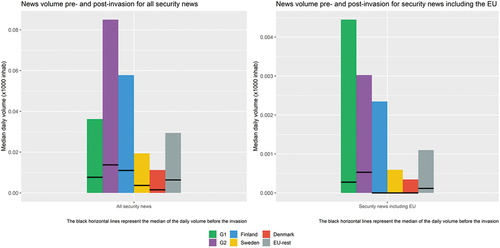

Country categories are explored more explicitly in , which condenses the data presented in .

Figure 4. Daily volume per 1000 inhabitants of security news, before and after the invasion, by country categories.

Based on the above, we observe a number of notable volume trends, both generally and within our selected categories. First, the volume of all security news, as well as of security news mentioning the EU, experienced a drastic increase in all Member States following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Second, in the post-invasion phase, neutral EU countries (G1) tend to present relatively high population-weighted volumes of security news mentioning the EU, while this was less the case before the invasion. This is due to unusually large spikes in Cyprus and Malta. Third, Russia-bordering EU and NATO members (G2) tend to present the highest population-weighted news volumes among our selected country categories, especially when considering all news on security after the invasion. Latvia leads the EU in population-weighted volume of all security news, both before and after the invasion, while Estonia leads in population-weighted volume of security news mentioning the EU after the invasion. Fourth, whereas there were relatively few news pieces on security with EU mentions in Finland prior to the invasion, this volume jumped remarkably after the invasion. And lastly, Sweden and Denmark present relatively low population-weighted volumes in both news sets, both before and after the invasion.

4.2. News tone before and after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

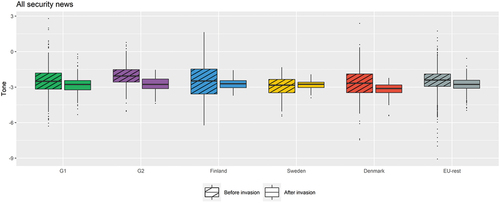

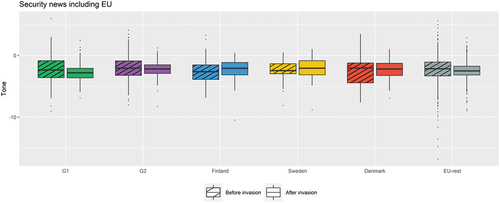

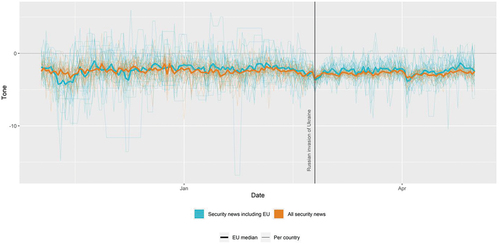

As can be inferred from , the tone of security news is generally negative. Our data confirm that, on average, that is the case in all 27 EU Member States between 3 November 2021 and 1 May 2022. Although tones declined slightly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, tone negativity was already prevalent before. The tone of the subset of news including EU mentions, however, is less negative than that of the full set of security news, both before and after the invasion.

Figure 5. Tone of all security news vs tone of security news mentioning the EU, by Member State and across the EU (November 2021-May 2022).

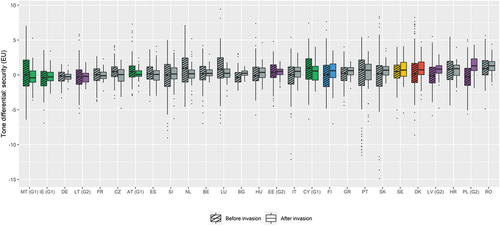

llustrates more clearly how the tone of news on security with EU mentions varied following the invasion, relative to the tone of all security news. Overall, the tone differential became more positive in 17 out of the 27 EU Member States. This positive shift is much more prevalent among the selected countries from : eight out of eleven experience a positive shift in their tone differentials, with the only exceptions being three neutral countries – Austria, Cyprus and Malta. Poland experiences the most significant positive shift overall. arranges countries according to their tone differential after the invasion, from most negative to most positive.

Figure 6. Tone differential of security news mentioning the EU, relative to all security news, before and after the invasion, by EU Member States.

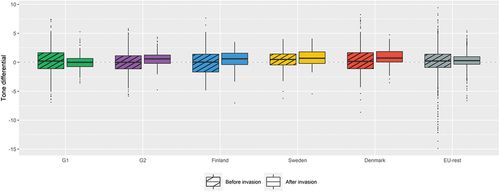

We explore country categories more explicitly in . The figure shows that tone differentials generally become more positive within our selected categories than among the remaining 16 EU countries (”EU-rest”), which collectively experience only a modest increase. The only exception are neutral EU countries (G1), where the aggregate differential decreases, albeit slightly.Footnote10

Figure 7. Tone differential of security news including the EU, relative to all security news, before and after the invasion, by country categories.

Based on the above, the most notable tone trends, both generally and for selected country categories, are the following. First, news tones have become even more negative after Russia’s invasion, both in the case of all security news and in the case of security news mentioning the EU, but tone differentials in favour of the latter have become even more positive. In five Member States, the absolute tone of news on security mentioning the EU in fact increased after the invasion. Four of these fall into the selected categories: Ireland (G1), Poland (G2), Finland and Sweden. Second, neutral EU countries (G1) showed great heterogeneity in tone differentials before the invasion. After the invasion, the dispersion decreases within this group due to falls in tone differential positivity in 3 out of the 4 countries. Third, Russia-bordering EU and NATO members (G2) were among the countries with the least positive tone differentials before the invasion, but overall, this group experienced a significant positive spike after February 24. This is due to Poland and Latvia going from 24th and 22nd to 2nd and 4th, respectively, in the EU-27 ranking of tone differential. And lastly, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark are among the EU countries with the most positive tone differentials post-invasion, due to significant increases in all three countries – particularly in Finland and Denmark, whose respective tone differentials were barely positive before the invasion.

5. Discussion

In this section, we will dissect our findings in more detail, discussing how they relate both to the existing literature and to recent survey data on CSDP acceptability among the public. We first focus on trends present in our entire period of study. In a second step, we interpret the most significant variations triggered by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

5.1. General trends

A first takeaway is that there are large differences between Member States in their daily, population-weighted volumes of news, both on security broadly, and on security including EU mentions. This was to be expected, given the different strategic cultures and threat perceptions among EU Member States. News items on security mentioning the EU are a relatively small portion of all security news, which might show that Member States still frame their respective security concerns primarily in national terms, and/or that EU media outlets devote significant attention to extra-EU security matters.

To illustrate this, we explore volume trends per country category. Volume trends among neutral countries are difficult to interpret, which goes to underline how diverse neutrality experiences are. Austria appears consistently around the centre of the EU-27 spectrum, while the other neutral countries undergo marked shifts across the two news sets and/or over time. For their part, Russia-bordering EU and NATO countries almost always produce high volumes of security news, both in general and with EU mentions. These countries allocate great importance to security and defence matters, given their histories of subordination or even subjugation to foreign powers, most recently the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, Finland falls among the centre of the pack in terms of news volumes, whereas Sweden and Denmark consistently produce lower volumes of news on security.

A second major finding is that vast volume differences are not mirrored in news tones, which are rather homogenous across EU Member States. A key factor explaining this lack of variance, and the negative overall tone, is that most of the events that attract media attention do so for unpropitious reasons (Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019). Even though there is great heterogeneity in the security concerns of EU Member States, by definition they are always painted in a negative light, and they tend to crowd out other security news with a more positive tone.

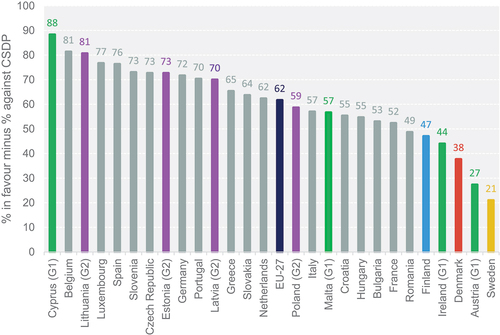

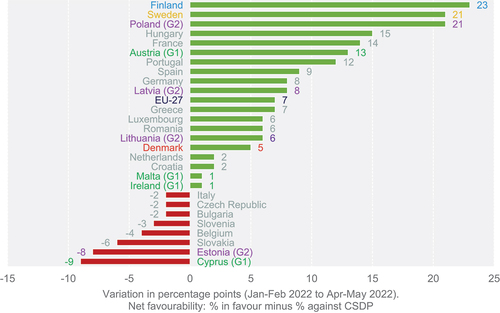

It is noteworthy, however, that news tones are generally more positive – or less negative – when the EU is mentioned, which is one of the most important findings of our study. This appears to capture the widespread and steady favourability towards CSDP among the European public (Schilde, Anderson, and Garner Citation2019). According to data collected prior to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine by Standard Eurobarometers 94, 95 and 96 (European Commission Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2022b),Footnote11 net favourability towards CSDP (i.e. percentage in favour of it minus percentage against it) was overwhelmingly positive in every single EU Member State. The overall number for the EU – stemming from aggregate, non-population-weighted data – is 62 percentage points (see ). In other words, a ‘permissive consensus’ toward CSDP seems to be present (Genschel, Leek, and Weyns Citation2023; Fiott Citation2023), but with a twist: it is not a function of negligible popular interest, as the following sub-section will show more clearly, and as Schilde, Anderson, and Garner (Citation2019) already suggested. Moreover, in line with traditional neofunctionalist predictions (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009, 6), public acceptability appears to accompany security and defence integration. Although it remains modest and mostly intergovernmental in nature, integration in this area continued to progress during our period of study, for example through the adoption of the Strategic Compass in March 2022, as well as common measures to counter the Russian aggression (e.g. arms deliveries under the so-called ‘European Peace Facility’) (see Fiott Citation2023).

Figure 8. Net favourability towards CSDP by EU member state in the run-up to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Source: own calculations, based on an average of data from QB6.2 in Standard Eurobarometers 94, 95, and 96 (European Commission, Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2022b).

Eurobarometer data () nevertheless show large differences between Member States, including remarkable heterogeneity among neutral EU countries (G1)Footnote12 and mostly above-average favourability among Russia-bordering EU and NATO members (G2). We also observe that five of the eleven countries examined in detail in this study – Finland, Ireland, Denmark, Austria and Sweden – are among the EU members showing the lowest net favourability towards CSDP. However, according to this survey data, net CSDP favourability is not close to being negative in any EU Member State. Even in Denmark, the only country that opted out of CSDP, net favourability towards this policy was distinctly positive before the Russian invasion. Our media-based data () complements these surveys by showing even more clearly that despite the opt-out, Denmark is by no means an outlier in its perceptions on CSDP: mentions of the EU clearly improve the tone of security news. The Danish case underlines that it is misleading to blame popular opinion for lack of progress in EU security and defence integration (Schilde, Anderson, and Garner Citation2019). The misalignment between popular preferences and actual policy in Denmark was eventually resolved in a referendum on 1 June 2022, with Danish voters deciding to abolish the CSDP opt-out by margins that echo Eurobarometer data: 67% in favour and 33% against.

5.2. The impact of the 2022 Russian war against Ukraine

When examining news volumes on security and defence matters, both in the overall set and the subset of news mentioning the EU, Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine stands out as a watershed moment: volumes jump in every single EU country ().

We probed whether volume shifts from the pre-invasion to the post-invasion period were dependent on belonging to selected country categories. A first takeaway is that, comparatively, the volumes of news on security with EU mentions are on the higher end in neutral Member States; however, neutral countries remain highly heterogenous as a group (see ). Their relatively high volumes may indicate either greater interest in furthering the EU’s CSDP in the absence of NATO security guarantees, or rather concerns about how a stronger CSDP resulting from the invasion may be made compatible with their respective neutrality policies.Footnote13

Second, the population-adjusted volumes of Russia-bordering EU and NATO countries increased more than the average, but only when considering all news on security. This suggests that these countries are particularly concerned about the Russian threat, but are not as prone as others to framing it as an EU matter (although Estonia is a clear exception, as shows).

Finally, out of the three EU countries where the clearest shifts in security and defence policy have taken place in 2022 – Finland, Sweden and Denmark – only Finland experienced a remarkably large volume spike, in security news mentioning the EU. Among these three, Finland is the only one sharing a border with Russia. This may also explain why its pre-invasion population-weighted volume was already higher than the Swedish and Danish ones, when considering the full set of security news.

In terms of tone, our research has also produced several relevant results, if somewhat more inconclusive. A first finding is that the tone of news articles on security decreased after the invasion, both when considering the full set and the subset mentioning the EU. This is not surprising, since post-invasion, these news items cover matters with even stronger negative connotations (e.g. deaths, wounded, displacements, destruction of physical infrastructure) – as is always the case during high-profile violent conflicts.

However, it is noteworthy that the tone of news on security mentioning the EU decreased slightly less than the tone of security news as a whole. Before the invasion, security news with mentions of the EU were already largely more positive in tone than security news in general. After the invasion, this difference between the news sets has become more accentuated: only five countries present negative tone differentials (see ). These findings suggest that EU efforts on security and defence in the context of the war are viewed rather positively, cushioning the decline in news tones on security. From a theoretical standpoint, this underscores that an increase in ‘mass politicisation’, which ‘the literature normally measures in terms of the appearance of [an] issue in newspapers and other mass media’ (Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra Citation2021, 336), does not necessarily imply a spike in contestation and could actually facilitate European integration in security and defence (Barbé and Morillas Citation2019).Footnote14

Our findings align quite closely with recent Eurobarometer data from a survey conducted in April-May 2022 (European Commission Citation2022a). In the EU, net favourability towards CSDP increased by 7 percentage points relative to the previous Eurobarometer survey, carried out just before the invasion (European Commission Citation2022b). See below.

Figure 9. Evolution in net CSDP favourability, before and after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Source: own calculations, based on January-February 2022 data from Standard Eurobarometer 96 (European Commission, Citation2022b, QB6.2) and April-May 2022 data from Special Eurobarometer 526 (European Commission, Citation2022a, QC14.2).

That being said, Eurobarometer data do not always match our tone differential data. In Austria, Cyprus and Malta (three neutral EU countries), our media-based data show that post-invasion, including mentions of the EU has a less positive effect on the tone of overall security news than it did pre-invasion (see , which show this group as an outlier – the only one where tone differentials decrease in positivity). Survey-based Eurobarometer data, however, show a fall in net CSDP favourability in Cyprus, but not in Austria and Malta (see ). Once again, neutral countries prove to be the most difficult to interpret among our selected country categories.

Conversely, Russia-bordering EU and NATO members followed a more discernible trend: all of them experienced significant positive shifts in their tone differentials (see ). The case where this is most visible is Poland, whose tone differential went from clearly negative (24th among the EU-27) to second most positive overall. Eurobarometer data () confirm this, showing that Poland is tied with Sweden as the second country experiencing the largest spike in net CSDP favourability.

Finland and Sweden also experienced significant positive shifts in their respective tone differentials. In fact, those two countries are the only ones where the tone of security news mentioning the EU increased in absolute terms after the Russian invasion (see , in Appendix 1). This matches Eurobarometer data (), where Finland ranks first overall, and Sweden is tied for second, in terms of increase in net CSDP favourability. All of this suggests that Finland and Sweden do not perceive their recent NATO applications as a substitute for CSDP, or as otherwise undermining the role that the EU should play in security and defence. On the contrary: they seem to treasure CSDP more than ever. A modest but perhaps not anecdotal rise in tone differential, as well as in net CSDP favourability, can also be perceived in Denmark. This may have had an impact on the outcome of the recent Danish referendum on CSDP opt-in, although baseline support was already high.

5.3. Limitations and avenues of further research

Our research design holds some limitations. First, our GDELT-based dataset does not include social media. This is a caveat worth considering, although it bears repeating that even in the EU Member States that perform worst in terms of press freedom, only a minority of the population (except in Malta) lists social media among their favoured sources to follow European political matters. Second, we lack information on the number of media sources in each country, and how that might correlate with the volume of news items per country. For example, it may be the case that there is a minimum number of news outlets per country, and that countries with small populations might therefore be more inclined to show proportionally higher volumes of news items. Third, media attention is limited by definition (Schrodt Citation2010). That is, if other issues take precedence in the news (e.g. domestic political upheaval), increases in news volumes on security matters may be smaller than what might be expected given changes in the external security of a country. And fourth, the way in which GDELT assigns a tone value to each news piece obscures its degree of ‘tone polarization’. For instance, within the same article, a quote or segment with a clearly positive tone may offset one with a clearly negative tone, thereby resulting in an overall value close to 0, which may be wrongfully interpreted as hesitancy or even indifference.

Beyond these limitations, which are inherent to the use of GDELT as the data source for this study, we also identify avenues of further research. First, while GDELT does not code the tone polarization within individual news items, the tone dispersion within all news produced in each country can be calculated (see ). These national-level differences have not been explored due to space constraints. Second, our subset of news on security mentioning the EU may include potential confounders (e.g. selected news pieces may also mention NATO, which may affect their respective tones). For this reason, as well as others mentioned above, the tone differential between this subset and the general population of news on security matters is an informative, but imperfect way of estimating CSDP favourability. Although opinion polls on CSDP favourability generally lend credence to our findings, further research would be needed to completely isolate potential confounding effects. Third, this study focused on two potential national determinants of perceptions: bordering Russia and relations with the main pillars of Euro-Atlantic security. Further research might explore other potential factors, such as military expenditure or the role of defence industries.

6. Conclusion

This article set out to study acceptability of EU security and defence integration among the EU public, a field where research is still ‘in its infancy’ (Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra Citation2021, 339). We investigate trends in media coverage before and after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine through a big data analysis of security-related news. Our GDELT-based dataset spans from 3 November 2021 to 1 May 2022. This research design complements more traditional measurements of citizens’ perceptions, such as opinion surveys. We build on literature suggesting that sentiment analysis of media outlets can be especially informative during crises and historical turning points (Herbst Citation1998; Kepplinger, Citation2007).

We consider several national determinants of public opinion, namely: 1) sharing a land border with Russia, and 2) stance vis-à-vis the main Euro-Atlantic security and defence arrangements (the EU’s CSDP, and NATO). These two variables are selected because of their outsized influence on debates around security and defence within the EU. Based on them, we closely track the evolution of eleven Member States, divided into five different categories reflecting their respective characteristics before the invasion: broadly neutral countries (Austria, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta); Russia-bordering EU and NATO members (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland); as well as Finland, Sweden and Denmark, which represent single-country categories.

Our results show that media attention towards security matters increased sharply across the EU after the Russian invasion, and even more so in most of our selected countries – especially in Russia-bordering EU and NATO Member States. However, not all countries report on security-related events in the same way. Some (e.g. Poland) present large increases in population-adjusted volume of security news, but not when considering specifically those pieces mentioning the EU. For others (e.g. Finland), the opposite is true.

Not surprisingly, the tone of news articles on security is negative overall, but less so whenever the EU is mentioned. While the tone of all security news grew even more negative after the invasion, the tone differential becomes slightly more positive. We gather from this that EU contributions to security and defence are generally – and increasingly – viewed favourably, suggesting that ‘mass politicization’ (Biedenkopf, Costa, and Góra Citation2021) in this realm can enhance the prospects of European integration (Barbé and Morillas Citation2019). This matches public opinion data showing that net CSDP favourability was already positive in every Member State before the Russian invasion (see also Schilde, Anderson, and Garner Citation2019), and increased in most of them after it. In Member States whose security and defence policies have undergone historical changes following the invasion (i.e. Finland and Sweden through their NATO applications, and Denmark through its CSDP opt-in), our data underscore that CSDP and NATO are regarded as complementary.Footnote15 All in all, our data provide further evidence that the much-discussed dichotomy between Europeanists and Atlanticists, while relevant (Costa and Barbé Citation2023), can sometimes be deceptive (Gavras et al. Citation2020).

Despite a series of limitations, our study has produced some noteworthy results. We have observed that the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has been a watershed moment for public perceptions of EU security and defence. However, rather than overturning existing trends, the invasion has accelerated many of them. Overall, we hope these findings and related research avenues can contribute to the growing body of literature on public opinion and acceptability in the EU.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mateu Tomi Marin for his excellent research assistance during the project. They also appreciate the feedback received from participants in the WC25 panel “A strategic European Union in a ‘smaller’ world: interconnectedness, contestation, and resilience” at the ISA 2022 Annual Convention (Nashville, 28 March - 2 April, 2022), participants in the ENGAGE General Assembly (Barcelona, 13-14 June, 2022) and participants in the SB-S03 panel “A strategic European Union in a contested world: interconnectedness, strategy, and resilience” at EISA PEC 2022 (Athens, 1-4 September, 2022). Finally, they are grateful to fellow contributors to this special issue, as well as two anonymous reviewers, for their most helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The only exception being Malta, where 55% of respondents do so (European Commission Citation2021c, 54).

2. For the sake of simplicity, hereinafter we will refer to these countries simply as those sharing a border with Russia, although another EU Member State (Sweden) has a maritime border with Russia.

3. Note also that errors in event databases are not limited to coding errors. Other potential error sources include news selection by reporters and editors, which is non-comprehensive and non-random by definition, as well as generic ontologies combining events that may not always belong together. These types of errors are common to all sorts of event databases, whether they rely on automated or human coding. In spite of this, the effectiveness of models using automatically-coded event data has been demonstrated (Schrodt Citation2010, 20–21).

4. This theme covers the following terms: national security, war, military conflict, terrorism, terror, 9/11, defence spending, military spending, police action, armed forces, base closure, military procurement, saber rattling, naval blockade, military embargo, no-fly zone, military invasion (Economic Policy Uncertainty Index Citation2012).

5. GDELT codes actors using actor and entity dictionaries. However, these dictionaries are highly state-centric, due to the focus of the original creators of the database (Schrodt Citation2012), which makes actor coding one of the most limited aspects of the GDELT Events database. Many private sector, non-governmental, or intergovernmental actors are not included in the actor or entity dictionaries. We thus decided to carry out a free-text search for the EU-related terms.

6. GDELT uses the Global Content Analysis Measure (GCAM) algorithm to code sentiment. This algorithm uses a sentiment dictionary based on Scherer’s Type of Affective States (‘STAS’), which reflects moods, emotions, interpersonal positions and attitudes towards a certain topic.

7. Our categories of traditionally neutral countries are based on Cramer and Franke (Citation2021, 41), with the exception of Cyprus, which is not covered in their study. We group Cyprus with the neutral countries (G1) because its prospects to join NATO are currently non-existent, due to Turkey’s guaranteed veto. Cyprus remains the only EU country not involved in NATO’s Partnership for Peace.

8. Volume waves both before and after the invasion are due to dips on weekends, when media tend to produce fewer news pieces.

9. , included in Appendix 1, represent the data in the form of box plots.

10. , in Appendix 1, represent the tone data per category for all security news and for security news mentioning the EU, respectively.

11. The fieldwork for these Eurobarometers was conducted in February-March 2021 (Standard Eurobarometer 94), June-July 2021 (Standard Eurobarometer 95), and January-February 2022 (Standard Eurobarometer 96). Although two of them precede our period of study, all three have been considered for robustness.

12. Cypriot neutrality is a product of external pressures exerted by Greece and Turkey since Cypriot independence, and the country’s subsequent history of occupation and de facto division. Given the lack of a path to NATO membership, Article 42.7 TEU is particularly valuable to Cyprus, as it is the only mutual defence clause available to it.

13. These concerns are particularly prominent in Malta (driving its decision not to join the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation, activated in 2016) which may be a reason why following the invasion it moved from 21st to 3rd in the EU rankings of population-weighted volume of security news mentioning the EU (see Figure 3).

14. Our article complements other research (Genschel, Leek, and Weyns Citation2023; Fiott Citation2023) in showing that publics may be more inclined than national elites (Schilde, Anderson, and Garner Citation2019), to pursue a cooperative and integrationist security and defence strategy when faced with exogenous geopolitical shocks.

15. EU-27 leaders also emphasized this general principle in their March 2022 Versailles Declaration (European Council Citation2022, 3).

References

- Alker, H. R., G. Duffy, R. Hurwitz, and J. C. Mallery. 1991. “Text Modeling for International Politics: A Tourist’s Guide to RELATUS.” In Artificial Intelligence and International Politics, edited by V. M. Hudson, 97–126, Boulder: Westview Press.

- Backfried, G., and G. Shalunts. 2016. “Sentiment Analysis of Media in German on the Refugee Crisis in Europe.” In Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management in Mediterranean Countries, edited by P. Díaz, N. Bellamine Ben Saoud, J. Dugdale, and C. Hanachi, 234–241. Cham: Springer.

- Barbé, E., and P. Morillas. 2019. “The EU Global Strategy: The Dynamics of a More Politicized and Politically Integrated Foreign Policy.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32 (6): 753–770. doi:10.1080/09557571.2019.1588227.

- Beck, U., and E. Grande. 2007. Cosmopolitan Europe. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Beyer, J. L., and S. C. Hofmann. 2011. “Varieties of Neutrality: Norm Revision and Decline.” Cooperation and Conflict 46 (3): 285–311. doi:10.1177/0010836711416956.

- Biedenkopf, K., O. Costa, and M. Góra. 2021. “Introduction: Shades of Contestation and Politicisation of CFSP.” European Security 30 (3): 325–343. doi:10.1080/09662839.2021.1964473.

- Biehl, H., B. Giegerich, and A. Jonas, edited by. 2013. Strategic Cultures in Europe: Security and Defence Policies Across the Continent. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Chaban, N., and O. Elgström. 2023. “Russia’s War in Ukraine and Transformation of EU Public Diplomacy: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal of European Integration.

- Costa, O. 2019. “The Politicization of EU External Relations.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (5): 790–802. doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.1478878.

- Costa, O., and E. Barbé. 2023. “Chasing a Moving Target: EU Actorness and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration.

- Cramer, C. S., and U. Franke, edited by. 2021. Ambiguous Alliance: Neutrality, Opt-Outs, and European Defence. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/ambiguous-alliance-neutrality-opt-outs-and-european-defence/.

- Damro, C. 2012. “Market Power Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (5): 682–699. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.646779.

- Daniel, J., and J. Eberle. 2021. “Speaking of Hybrid Warfare: Multiple Narratives and Differing Expertise in the ‘Hybrid warfare’ Debate in Czechia.” Cooperation and Conflict 56 (4): 432–453. doi:10.1177/00108367211000799.

- Devine, K. 2011. “Neutrality and the Development of the European Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy: Compatible or Competing?” Cooperation and Conflict 46 (3): 334–369. doi:10.1177/0010836711416958.

- De Wilde, P., and M. Zürn. 2012. “Can the Politicization of European Integration Be Reversed?” Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (s1): 137–153. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02232.x.

- Economic Policy Uncertainty Index. 2012. “Term sets by category of EPU.” https://www.policyuncertainty.com/categorical_terms.html

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” The Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- European Commission. 2021a. “Standard Eurobarometer 94.” https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2355

- European Commission. 2021b. “Standard Eurobarometer 95.” https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2532

- European Commission. 2021c. “Media Use in the European Union: Report.” https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2775/726029

- European Commission. 2022a. “Key challenges of our times: The EU in 2022 (Special Eurobarometer 526).” https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2694

- European Commission. 2022b. Standard Eurobarometer 96. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2553

- European Council. 2022. “Informal meeting of the Heads of State or Government: Versailles Declaration.” https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/54773/20220311-versailles-declaration-en.pdf

- Fiott, D. 2023. “In Every Crisis an Opportunity? European Union Integration in Defence and the War on Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration.

- Gavras, K., M. Mader, and H. Schoen. 2022. “Convergence of European Security and Defense Preferences? A Quantitative Text Analysis of Strategy Papers, 1994–2018.” European Union Politics 23 (4): 662–679. doi:10.1177/14651165221103026.

- Gavras, K., T. J. Schotto, J. Reifler, S. Hofmann, C. Thomson, M. Mader, and H. Schoen. 2020. “NATO and CSDP: Party and Public Positioning in Germany and France.” NDC Policy Brief 11. https://www.ndc.nato.int/download/downloads.php?icode=651.

- Genschel, P., L. Leek, and J. Weyns. 2023. “War and Integration: The Russian Attack on the Ukraine and the Institutional Development of the EU.” Journal of European Integration.

- Gerner, D. J., P. A. Schrodt, R. A. Francisco, and J. L. Weddle. 1994. “Machine Coding of Event Data Using Regional and International Sources.” International Studies Quarterly 38 (1): 91–119. doi:10.2307/2600873.

- Góra, M., N. Styczyńska, and M. Zubek, edited by. 2019. Contestation of EU Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy: Actors, Arenas and Arguments. Copenhagen: Djøf Publishing.

- Grande, E., and S. Hutter. 2016. “Introduction: European Integration and the Challenge of Politicisation.” In Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics, edited by S. Hutter, E. Grande, and H. Kriesi, 3–31. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316422991.002.

- Guo, L., and C. J. Vargo. 2017. “Global Intermedia Agenda Setting: A Big Data Analysis of International News Flow.” The Journal of Communication 67 (4): 499–520. doi:10.1111/JCOM.12311.

- Herbst, S. 1998. Reading Public Opinion: How Political Actors View the Democratic Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- Johansson-Nogués, E., M. C. Vlaskamp, and E. Barbé. 2020. “European Union Contested: Foreign Policy in a New Global Context.” Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33238-9.

- Kepplinger, H. M. 2007. “Reciprocal Effects: Toward a Theory of Mass Media Effects on Decision Makers.” Harvard International Journal of Press/politics 12 (2): 3–23. doi:10.1177/1081180X07299798.

- King, G., and W. Lowe. 2003. “An Automated Information Extraction Tool for International Conflict Data with Performance as Good as Human Coders: A Rare Events Evaluation Design.” International Organization 57 (3): 617–642. doi:10.1017/S0020818303573064.

- Krastev, I., and M. Leonard. 2022. The Crisis of European Security: What Europeans Think About the War in Ukraine. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the-crisis-of-european-security-what-europeans-think-about-the-war-in-ukraine/.

- Lau, S. 2022. “‘We Told You so!’ How the West Didn’t Listen to the Countries That Know Russia Best.” POLITICO. March 9. https://www.politico.eu/article/western-europe-listen-to-the-baltic-countries-that-know-russia-best-ukraine-poland/

- Leetaru, K. H., T. K. Perkins, and C. Rewerts. 2014. “Cultural Computing at Literature Scale: Encoding the Cultural Knowledge of Tens of Billions of Words of Academic Literature.” D-Lib Magazine 20 (9–10). doi:10.1045/september2014-leetaru.

- McCombs, M. E., and D. L. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1086/267990.

- McCombs, M. E., and S. Valenzuela. 2021. Setting the Agenda: Mass Media and Public Opinion. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley.

- Michaels, E., and R. Kissack. 2021. “Evaluating the National Acceptability of EU External Action: Conceptual Framework for the ENGAGE Project.” ENGAGE Working Paper Series. https://www.engage-eu.eu/publications/evaluating-the-national-acceptability-of-eu-external-action

- Molnár, A., and L. Takács. 2021. “Strategic Communication of EU CSDP Missions – Measuring the Eu’s External Legitimacy.” Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 15 (3): 319–334. doi:10.1108/TG-11-2020-0314.

- Müller, P., K. Pomorska, and B. Tonra. 2021. “The Domestic Challenge to EU Foreign Policy-Making: From Europeanisation to de-Europeanisation?” Journal of European Integration 43 (5): 519–534. doi:10.1080/07036337.2021.1927015.

- Orenstein, M. 2023. “Transformation of Europe After Russia’s Attack on Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration.

- Pedersen, K. 2006. “Denmark and the European Security and Defence Policy.” In The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy, edited by A. J. K. Bailes, G. Herolf, and B. Sundelius, 37–48, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, D. 2014. “European Security Policy for the People? Public Opinion and the Eu’s Common Foreign, Security and Defence Policy.” European Security 23 (4): 388–408. doi:10.1080/09662839.2013.875531.

- Reporters Without Borders. 2022. “World Press Freedom Index.” https://rsf.org/en/index

- Schilde, K. E., S. B. Anderson, and A. D. Garner. 2019. “A More Martial Europe? Public Opinion, Permissive Consensus, and EU Defence Policy.” European Security 28 (2): 153–172. doi:10.1080/09662839.2019.1617275.

- Schimmelfennig, F., D. Leuffen, and B. Rittberger. 2015. “The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization and Differentiation.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (6): 764–782. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1020835.

- Schmidt, P., and B. Zyla. 2011. “European Security Policy: Strategic Culture in Operation?” Contemporary Security Policy 32 (3): 484–493. doi:10.1080/13523260.2011.626329.

- Schoen, H. 2008. “Identity, Instrumental Self-Interest and Institutional Evaluations: Explaining Public Opinion on Common European Policies in Foreign Affairs and Defence.” European Union Politicss 9 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1177/1465116507085955.

- Schrodt, P.A. 2010. “Automated Production of High-Volume, Near-Real-Time Political Event Data.” APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1643761

- Schrodt, P.A. 2012. CAMEO: Conflict and Mediation Event Observations, Event and Actor Codebook. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University.

- Smirnova, A., H. Laranetto, and N. Kolenda. 2017. “Ideology Through Sentiment Analysis: A Changing Perspective on Russia and Islam in NYT.” Discourse & Communication 11 (3): 296–313. doi:10.1177/1750481317699347.

- Soroka, S., P. Fournier, and L. Nir. 2019. “Cross-National Evidence of a Negativity Bias in Psychophysiological Reactions to News.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (38): 18888–18892. doi:10.1073/pnas.1908369116.

- Thomas, D. C. 2021. “The Return of Intergovernmentalism? De-Europeanisation and EU Foreign Policy Decision-Making.” Journal of European Integration 43 (5): 619–635. doi:10.1080/07036337.2021.1927013.

- Wiener, A. 2014. A Theory of Contestation. Berlin: Springer.

- Zürn, M. 2014. “The Politicization of World Politics and Its Effects: Eight Propositions.” European Political Science Review 6 (1): 47–71. doi:10.1017/S1755773912000276.