ABSTRACT

Sanctions were the European Union’s (EU) immediate response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. These restrictive measures focus on specific individuals, entities, goods, services, and sectors. Out of a need for nuanced data, we map and analyze the entire set of EU sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 until today. We show and argue that the sanctions’ design has become increasingly comprehensive over the past months which reflects the EU’s geopolitical considerations in carving out a response to the unparalleled threat imposed by Russia. Our new, author-created dataset covers the complete track record of Council decisions, regulations, and annexes of these restrictive measures, and thereby offers fine-grained information on the transformation and design of EU sanctions against Russia and the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) more and more frequently adopts sanctions against third states in response to wrongdoings. Indeed, restrictive measures were the EU’s immediate reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. The major question for EU member states was, however, not whether the EU would sanction Russia, but which exact measures it would adopt.

The vast majority of EU sanctions are ‘smart’ measures (Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2020; Meissner Citation2023). Smart sanctions target specific individuals, entities or goods (Tostensen and Bull Citation2002) in order to avoid humanitarian implications for the target’s population (e.g. Allen et al. Citation2020; Meissner and Mello Citation2022). Against Russia, too, the EU imposes restrictive measures under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), which are focused on certain individuals, entities such as banks and a list of sectors and goods, for instance the oil sector or luxury goods (e.g. Van Bergeijk Citation2022). Yet, in this article, we show how the sanctions against Russia have evolved over the past months and are now the most comprehensive ones the EU has ever adopted autonomously. We argue that this increasingly comprehensive design reflects the EU’s geopolitical considerations in carving out a response to the unparalleled threat imposed by Russia.

In contributing to this special issue and the broader literature on sanctions, we provide a systematic account of the entire set of EU restrictive measures and their designs imposed on Russia since 2014 until today. Our new, author-created dataset (Meissner and Graziani Citation2022) covers the complete track record of Council decisions, regulations, and annexes of these restrictive measures. We thereby provide the, to date, most detailed data on EU sanctions imposed on Russia as existing datasets operate on the type of sanctions as the most granular basis of information (Felbermayr et al. Citation2020; Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2020; Meissner Citation2023; Weber and Schneider Citation2020). Our systematic data in combination with background talks with officials from EU member states’ permanent representatives and from the Council’s RELEX group in Brussels, allow us to analyze the sanctions’ design, and to assess whether Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine affected the considerations driving EU’s design choices. Indeed, we argue that the unparalleled threat of Russia’s war against Ukraine triggered geopolitical considerations to be a major driving force of the sanctions’ comprehensive design. Like other scholars in this special issue who address the impact of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine on the European integration process, on EU defense integration, and on the EU’s role as a strategic actor, we, thus, discern a noticeable transformation of EU’s sanctions decisions caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The article proceeds by, first, reviewing the existing literature on sanctions with a focus on specific designs and with a view to restrictive measures imposed on Russia. The second section develops a categorization of sanctions’ designs, and conceptualizes three potential drivers of these sanctions’ designs. Third, we introduce the data on EU restrictive measures imposed on Russia. In the fourth section, we empirically examine the design of EU sanctions against Russia. In the conclusion, we summarize the findings and reflect on future research steps.

State of the art

A vast array of research is available on sanctions (e.g. Biersteker et al. Citation2013; Hufbauer et al. Citation2007) and a growing body of literature examines EU restrictive measures (e.g. Giumelli Citation2011; Portela Citation2010). Yet, a majority of this scholarship relies on a dichotomous conceptualization of sanctions focusing on whether sender states adopt or do not adopt sanctions (Hafner-Burton and Montgomery Citation2008; Von Soest and Wahman Citation2015). Only recently scholarship has begun to pay explicit attention to the variation of sanctions’ types and designs (Hedberg Citation2018; McLean and Whang Citation2014; Meissner Citation2023; Portela Citation2016). Indeed, scholars identify sanctions’ designs and their variations as a research gap (Bapat et al. Citation2020, 451; Giumelli Citation2011, 23).

Among recent data collection efforts, new datasets have been created that cover EU restrictive measures (Felbermayr et al. Citation2020; Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2020; Meissner Citation2023; Weber and Schneider Citation2020). These new datasets provide rich empirical information on (EU) sanctions. Still, the most fine-grained level of information available in these datasets is the varying sanctions’ types while the specific designs of what individuals, entities, goods or sectors are targeted by those sanctions are unaccounted for.

Only few studies include or operate on information regarding nuanced sanctions’ designs such as the individuals listed or the entities and goods targeted (Hedberg Citation2018; Onderco and van der Veer Citation2021; Portela and van Laer Citation2022). Onderco and van der Veer (Citation2021) investigate firms’ responses to Russia’s countersanctions to the EU restrictive measures adopted in 2014 differentiating the sanctioned and non-sanctioned goods. Portela and van Laer (Citation2022) examine the impact of sanctions on blacklisted individuals thereby operating on concrete data regarding the individuals targeted by EU restrictive measures. Hedberg (Citation2018) includes detailed data on the commodities targeted by sanctions – more specifically, Russian countersanctions to EU restrictive measures – and the motivation for which those commodities were included or excluded in the sanctions package.

A growing body of literature devotes particular attention to the EU-Russia sanctions (e.g. Giumelli Citation2017; Portela et al. Citation2021; Szép Citation2020; Van Bergeijk Citation2022) and the Russian countersanctions following the 2014 EU restrictive measures in reaction to the annexation of Crimea (Hedberg Citation2018; Onderco and van der Veer Citation2021). Among the most discussed themes in this strand of the literature is an evaluation of the EU sanctions packages imposed on Russia and their likely (in-)effectiveness and consequences (e.g. Giumelli Citation2017; Van Bergeijk Citation2022); the salience and politicization of the sanctions (e.g. Karlović, Čepo, and Biedenkopf Citation2021); the (non-)alignment of third states with EU restrictive measures (Hellquist Citation2016); and the decision-making dynamics among EU member states in shaping the sanctions (Portela et al. Citation2021; Schoeller Citation2020; Szép Citation2020). Yet, a systematic and comprehensive account of the full record of EU sanctions imposed on Russia is missing.

In this article, we fill this gap of knowledge and research on the specific design of EU restrictive measures imposed on Russia by mapping, documenting and investigating the entire set of sanctions from 2014 until today. We thereby provide the, to date, most fine-grained data on EU sanctions.

Categorizing and analyzing the design of sanctions

In order to investigate the transformation and design of EU restrictive measures imposed on Russia between 2014 and 2022, in this section, we, first, develop a categorization of sanctions’ designs which reflects their entailed costs for the target and its population on a continuum between targeted and comprehensive. This continuum relies on the varying types of measures (Biersteker et al. Citation2013; Meissner Citation2023) that we combine with a specification of the scope of each sanction’s type (Biersteker et al. Citation2013). Second, by building on sanctions research (e.g. Giumelli Citation2011; Portela Citation2010), we conceptualize three potential drivers of these sanctions designs: humanitarian considerations; domestic considerations; and geopolitical considerations.

The design of sanctions on a continuum between targeted and comprehensive

Despite a flourishing research agenda on sanctions, there is no clear categorization of their designs. The EU imposes different types of sanctions in varying policy areas (Meissner and Mello Citation2022; Portela Citation2010). Even among restrictive measures adopted under the CFSP, the design of these measures varies significantly (Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2020; Meissner Citation2023). One dimension of sanctions’ design is their scope ranging between comprehensive and targeted. However, the literature displays a certain degree of confusion regarding the understanding of a targeted versus a comprehensive scope (Biersteker et al. Citation2013, 5; Meissner Citation2023).

As was recently proposed by scholarly research (Biersteker et al. Citation2013), a helpful indicator for classifying the design of sanctions – especially their scope – is the expected impact on the population in the target country. The expected impact reflects the sanctions’ scope on a continuum ranging between comprehensive and targeted (Biersteker et al. Citation2013). Comprehensive restrictions, on one extreme of this continuum, entail costs for the target’s entire population as a complete export ban, for example, would do (Von Soest and Wahman Citation2015, 965). Targeted sanctions, on the other extreme of the continuum, entail costs only for specific individuals, entities or firms (Hufbauer et al. Citation2007, 138; Von Soest and Wahman Citation2015, 965). The expected costs that arise out of the sanctions for the target population are, thus, an indication for the restrictions’ scope. Hence, in this article, we refer to the scope of sanctions as a continuum ranging between targeted, in an extreme case against one individual, and comprehensive, in an extreme case a complete, full-on embargo against a country and its population.

The variation within the continuum between a targeted and a comprehensive sanction’s design stems from the entailed costs for the target and its population, i.e. how much the sanction discriminates (Biersteker et al. Citation2013, 16). In specifying the costs for the target state, we rely on a combination of the sanction’s type and the sanction’s scope (Biersteker et al. Citation2013; Biersteker et al. 2020). According to Biersteker et al. (Citation2013, 17), we consider asset freezes and travel bans as the most discriminating and thus most targeted measures since they affect a limited number of natural persons; followed by an arms embargo and restrictions on dual-use goods; and restrictions on transport. Sectoral sanctions such as financial restrictions and export and import bans are considered least discriminating and thus most comprehensive since they affect large parts of the economy and society – more so than an arms embargo which is limited to weapons and military equipment (Biersteker et al. Citation2013). We build on this classification of sanctions’ types and combine it with a nuanced specification of the measures’ scope within each type. This specification is grasped by the specific target hit by the sanctions ranging between natural persons; followed by legal persons; products; product groups and sectors; to the entire population ( in online supplement). With this combination, we depict the sanctions’ entailed costs for the target on a continuum from targeted to comprehensive and their transformation over time.

Table 1. Types and targets and EU restrictive measures against Russia and the Russian-controlled territories (2014–2022).

Drivers of varying sanctions’ designs

A large bulk in the literature assumes and argues that sender state(s) adopt targeted rather than comprehensive sanctions due to humanitarian considerations (Biersteker et al. Citation2013; Hufbauer and Oegg 2000). Indeed, policy-makers shifted to targeted, ‘smart’ sanctions due to the humanitarian consequences of comprehensive measures in the 1990s (Tostensen and Bull Citation2002). Empirical research results confirm the unintended, negative effects of comprehensive sanctions (Meissner and Mello Citation2022). Humanitarian concerns are therefore likely to guide sender state(s) in designing sanctions packages. This should apply particularly to the EU as many scholars argue that the EU adheres to international norms and values including democracy, human rights, and the rule of law (Manners Citation2002; Sjursen Citation2006). According to theoretical considerations of the EU as a ‘normative power’ (Manners Citation2002), it has a strong commitment to uphold humanitarian principles and to export these through its external relations. CFSP restrictive measures are a particularly powerful tool of EU foreign policy. According to the perspective of the EU as an actor guided by humanitarian principles, we should assume that it seeks to avoid any negative, humanitarian effects for the target population. Unintended, negative consequences of sanctions can be expected to be greatest when the restrictions entail major costs for the target population at large (Meissner and Mello Citation2022). Thus, we can expect that if the EU is guided by humanitarian concerns it shall try to minimize the costs of restrictive measures for the target population and therefore adopt targeted sanctions against specific individuals and entities onlyFootnote5. Still, research indicates that the EU acts according to humanitiarian principles only under certain conditions and with varying measures (Saltnes Citation2017; Meissner Citation2021; Meissner Citation2023)Footnote7. Saltnes (Citation2017) puts forward a theoretical argument whereby the EU identifies the gravity of a norm violation and evaluates which measures are the most appropriate response to such a violation in a certain situationFootnote3.

Humanitiarian principles > minimize the costs of restrictive measures for the target population

As argued above, humanitarian principles are a potentially strong motive driving EU sanctions’ design decisions, but likely in combination with other conditions. One of these are domestic conditions. Indeed, a strand in the literature takes a perspective on the design of sanctions which relies on a domestic politics explanation (e.g. McLean and Whang Citation2014; Weber and Schneider Citation2020). McLean and Whang (Citation2014) are most pronounced in putting forward a theoretical model whereby decision-makers adopt a sanctions’ design in line with lobbying activities by affected interest groups. Similarly, Weber and Schneider (Citation2020) argue that policy-makers take into account domestic interest groups when they weigh different sanctions’ designs. Indeed, there is some evidence that business groups lobby policy-makers regarding sanctions although these lobbying activities seem to focus on subsequent implementation and compliance (Giumelli and Onderco Citation2021). Bĕlín and Hanousek (Citation2021) show that the EU carefully took into account business groups in the design of economic sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014. Under the condition of lobbying, we would therefore expect that decision-makers consider the potential costs arising from sanctions for domestic business groups and their nation state. According to such domestic considerations, policy-makers would try to minimize the costs of restrictive measures for these affected business groups by adopting an appropriate sanctions’ design that minimizes the costs for their respective state.

Domestic considerations > minimize the costs of restrictive measures for the sender state(s)

Recent advancements in sanctions’ research pay more attention to geostrategic considerations when policy-makers adopt and design restrictive measures (Hedberg Citation2018; Meissner Citation2023). Hedberg (Citation2018), for example, proposes a theoretical explanation for the design of Russian countersanctions against Europe, which she terms ‘differentiated retaliation’. Differentiated retaliation takes into account geostrategic concerns when decision-makers adopt sanctions in such a way that they choose a design which hurts the targeted states most (Hedberg Citation2018). Recent research (Meissner Citation2023), too, finds that geopolitical considerations are reflected in design decisions on sanctions. Under the condition of geopolitical concerns, decision-makers tend to opt for large scale sanctions which impose high costs on the target (see also Giumelli Citation2011). The underlying reason is that sanctions are meant to be an appropriate and proportionate response to the behaviour of the target state. Hence, when the actions of the target state pose a geopolitical or strategic threat to the (international) community, we can expect that decision-makers would maximize the costs imposed by sanctions for the target state. A comprehensive design of restrictive measures maximizes these costs for the target state.

Geopolitical concerns > maximize the costs of restrictive measures for the target state

Granular data on EU sanctions’ designs

In mapping, categorizing and analyzing EU restrictive measures imposed on Russia (2014–2022), we rely on a new, author-created dataset (Meissner and Graziani Citation2022). Our dataset tracks all restrictive measures imposed autonomously by the EU against Russia and the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine in the period between 2014 and 2022. It includes all amendments and derogations to the Council decisions, regulations and annexes, and therefore provides a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the sanctions that have been in place against Russia since 2014.

The units of analysis of the dataset are observations based on a type of restrictive measures imposed by the EU at a specific point in time according to a specific legal act. For each observation, we report the precise targets, i.e. individuals, entities, goods, and sectors. Drawing on the Council’s legal acts and the terminology used therein, we identified 10 sanctions types: arms embargo; asset freezes; export bans; export ban on dual-use goods; financial sanctions; import bans; restrictions on transport; restrictions on media; services bans; travel bans. in the online supplement illustrates the number of observations per year for each type of sanction. Consequently, each observation in the dataset refers to one of these sanction types, to one of the sanctioned territories (Russia or the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine), to a specific year between 2014 and 2022, and to a specific legal act, thus mapping how the restrictive measures have evolved over time. This results in a total of 310 observations (288 for Russia and 22 for the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine), with the first dating back to 17 March 2014, and the last to 21 July 2022.Footnote1 The online supplement reports in more detail our approach adopted in compiling the data.Footnote2

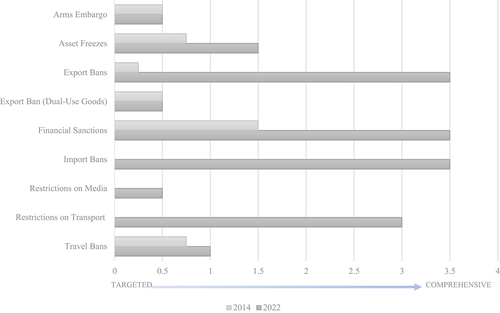

Figure 1. Design of EU restrictive measures against Russia (2014–2022)Footnote4.

Based on our dataset, we assess the design of EU restrictive measures through a combination of the sanctions’ type and their scope: for each observation in the dataset, we inductively locate the measure on a continuum between targeted and comprehensive using the information on the sanction’s type – asset freeze, travel ban, arms embargo, ban on dual-use goods, restrictions on media, restrictions on transport, sectoral sanction like financial restrictions, export ban, or import ban – in combination with the sanction’s scope – targeting natural persons, legal persons, entities, products, product groups, sectors, and the respective number where applicable. in the online supplement reports the assessment of the restrictive measures. We triangulate this data with information retrieved from background talks with staff members from EU member states’ permanent representatives and the Council’s RELEX group in Brussels.

Descriptive empirical results

The EU imposed its first sanctions on Russia – and the non-government controlled areas Crimea and Sevastopol – in 2014 as a response to the illegal annexation of Crimea. Throughout the years, and especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the EU’s restrictive measures have been progressively expanded through numerous sanctions packages (Van Bergeijk Citation2022). Additional sanctions were adopted in February 2022 against the non-government controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine. Over time, the number and the scope of the restrictive measures in place against Russia massively expanded and shifted from targeted towards more comprehensive. This section documents these developments.

The first CFSP restrictive measures imposed by the EU on Russia in 2014 were primarily targeted in design and increasingly escalated into economic restrictions in the technology and oil sectors. More specifically, the EU, in a first step in March 2014, imposed travel bans and asset freezes: The first 21 individual designations consisted of Russian and pro-Russian politicians and government members of Crimea, members of the Russian Federation Council and the State Duma who had supported the annexation of Crimea, as well as Russian commanders responsible for military units deployed in Crimea (Obs.1 and 2). In 2014, the list of persons targeted by asset freezes and travel bans was repeatedly expanded, resulting in a total of 130 natural persons and 28 legal persons being added over the course of that year. In a subsequent step, more comprehensive sanctions were adopted in July 2014, i.e. an arms embargo prohibiting the export and import of arms and related material (Obs. 22). This measure was supported by the prohibition to provide any form of associated services, in particular those concerning goods and technology listed in the Common Military List of the EU (Obs. 23). An export and services ban for dual-use goods and technology (with some derogations back then related to the aeronautics and space industry as well as to civil nuclear capabilities within the EU) were also among the restrictive measures imposed on Russia in July 2014 (Obs. 20 and 24). In a third step, and as part of its economic restrictions, the EU imposed an export ban related to technologies used in the oil industry in July 2014. Initially, this restriction did, however, not represent a proper ban, as exports were not completely prohibited – they required a prior authorization by the competent authorities (Obs. 21 and Annex II). In addition, the EU adopted financial sanctions that went beyond asset freezes (Obs. 32). In 2014, these targeted mainly five Russian banks (Annex III), three companies engaged in the military sector (Annex V), and three companies operating in the oil and gas industry (Annex VI). Overall, the restrictive measures in 2014 were primarily targeted combined with some more comprehensive sanctions in the technology and oil sector, so that costs for the general public in Russia were kept to a minimum.

In the period between 2015 and 2021, the number and scope of restrictive measures did not significantly change. The amendments to the Council regulations and decisions tackled four types of sanctions, namely asset freezes, travel bans, the arms embargo and services bans. As for the latter two, derogations were introduced in 2015 and 2017 allowing for the export and import of chemical substances needed for certain satellite launch operations and the ExoMars 2020 mission, along with related services (Obs. 56, 57, 75 and 76). With regard to asset freezes and travel bans, the amendments covered primarily adjustments to the lists of targeted persons: Between 2015 and 2021, asset freezes and travel bans were imposed, for instance, on natural and legal persons involved in the supply of gas turbines and power plants that aimed at establishing an independent power supply for Crimea (Obs. 68 and 69), or on persons participating in the organisation of Russian presidential elections in Crimea and of elections in the Donetsk and the Luhansk regions (Obs. 79, 80, 84 and 85).

Since the Russian recognition of the independence of the two separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk in February 2022 and the subsequent invasion of Ukraine, the restrictive measures against Russia have been massively expanded in number and scope. The sanctions’ increasing scope has also become costlier for the Russian population with restrictions in the economic, financial and transport sectors that affect the public’s every-day life. Over the past months, the EU has imposed travel bans on 967 individuals as well as asset freezes on 967 natural persons and on 50 legal persons. The targeted individuals include, for instance, Vladimir Putin and Sergey Lavrov, the majority of members of the State Duma, a significant number of businessmen and oligarchs, as well as family members of the targeted individuals (Obs. 118, 119, 144, 145, 226 and 227). Furthermore, in 2022 asset freezes were imposed, inter alia, on several Russian banks and financial institutions, on entities engaged in pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian propaganda, on companies engaged in the arms, petroleum, electronics and transport industry, as well as on legal persons supporting and/or benefitting from the Russian Government (Obs. 116, 183, 226 and 254).

From February to July 2022, the export, import and related services bans were extended to multiple core economic sectors: the military, defence and security sector (Obs. 122 and Annex VII); the oil and gas sector (Obs. 128 and 172, Annexes II and X); the aviation and space industry (Obs. 130 and Annex XI, which includes aircraft, spacecraft and related parts); the maritime industry (Obs. 158 and Annex XVI, which contains vessels as well as marine systems and equipment); the luxury industry (Obs. 178 and Annex XVIII, which includes, for instance, certain alcoholic beverages, perfumes, coats, carpets, household appliances and sports equipment); to goods and technology which could enhance the Russian industry (Obs. 205 and Annex XXIII). The sanctions’ design has been transformed and shaped in such a way that these economic restrictions increasingly concern the Russian population. Luxury goods such as alcoholic beverages or perfumes, for example, are under an EU export ban. For all export bans, some limited derogations are foreseen, most notably for humanitarian and/or medical purposes. In addition to these export bans, the sanctions packages imposed by the EU in recent months introduced import bans along with bans on related services for the iron and steel industry (Obs. 176 and Annex XVII), the gold industry (Obs. 273 and Annex XXVI), for goods generating significant revenues for Russia (Obs. 201 and Annex XXI, which includes, for instance, caviar, potassium chloride and wood), for coal and other fossil fuels (Obs. 194 and Annex XXII) and, with a transitory period of 6 to 8 months, for crude oil and petroleum products (Obs. 238 and Annex XXV). As for the latter, derogations were introduced for Bulgaria, Croatia and the Czech Republic, along with some exceptions related to oil delivered by pipeline.

As far as financial sanctions other than asset freezes are concerned, in 2022 they were massively expanded in their range and scope. The restrictive measures imposed in 2014 were extended to financial institutions with over 50% public ownership or control supporting Russia’s or the Central Bank’s activities and to legal persons controlled, with over 50% public ownership or with other economic relations with Russia or its Central Bank (Obs. 132 and Annexes XII and XIII). Moreover, additional financial sanctions were imposed against certain state-owned companies, as well as against Russian nationals, individuals residing in Russia (with limited derogations), legal persons established in Russia, the Russian government, the Central Bank of Russia, and the Russian Direct Investment Fund (Obs. 127, 133–136, 147, 150, 152, 179, 180, 216, 218 and Annex XIX). Additionally, 10 Russian banks were excluded from the SWIFT system (Obs. 151 and Annex XIV). Again, certain derogations are foreseen for the various financial sanctions, related, for example, to food security, humanitarian or medical purposes, as well as to the safeguarding of the EU’s financial stability. But overall these unprecedented financial sanctions imposed by the EU significantly restrict transactions between Russia, including Russian entities and citizens, and EU member states, entailing costs for the entire Russian population.

One last noteworthy development in recent months was the introduction of two new types of CFSP sanctions: Restrictions on the transport industry – most notably related to flights and aircraft (Obs. 146), to vessels (Obs. 199) and to road transport undertakings (Obs. 207) – and restrictions on media which prohibit the broadcast of content by certain Russian state-owned outlets (Obs. 153 and 231 and Annex XV). These sanctions, too, impose significant costs on larger parts of the Russian population, as they inhibit effective transport from and to EU territories. The entailed costs for the population are reinforced by measures in other policy fields which the EU explicitly refers to as ‘sanctions’ and which target the broader public: the full prohibition of Russian natural and legal persons in procurement contracts; the prohibition of contracts with Russian owned or controlled entities; the termination of participation of Russian public bodies in the European Commission’s funding schemes and grant agreements like Horizon Europe; and the suspension of the EU’s Visa Facilitation Agreement with Russia (Council Citation2022; European Commission Citation2022c). All of these measures directly or indirectly entail costs for the broader Russian population.

Consequently, the dataset’s observations clearly indicate that, overall, the scope of the EU’s sanctions against Russia has become more comprehensive over time and the entailed costs for the entire population have expanded. illustrates these developments: it positions the restrictive measuresFootnote6 on a continuum between targeted and comprehensive differentiating between 2014 and 2022. As can be inferred from , certain sanctions like the arms embargo and the export ban on dual-use goods remain rather targeted, as they address few specific sectors. Conversely, the scope of export and import bans has shifted: The measures adopted in 2014 provided for some limited restrictions for technologies related to the oil industry; whereas the restrictions imposed in recent months target core economic sectors, most notably the oil sector. They are thus likely to result in far-reaching consequences for the entire population (Biersteker et al. Citation2013, 17). For financial sanctions other than asset freezes, too, a clear shift along the continuum toward more comprehensive sanctions has occurred. While the sanctions adopted in 2014 targeted 11 banks and companies engaged in specific sectors, measures imposed over the last months affect not only 35 banks, financial institutions and companies, but also Russia as a whole, its government and Central Bank, along with Russian nationals and individuals residing in Russia. Moreover, the new restrictions introduced in 2022 concerning the transport industry, and particularly those related to the aviation sector, represent a clear development towards a more comprehensive sanction regime, likely to have a far-reaching impact on Russia’s population (Biersteker et al. Citation2013, 17). Travel bans and asset freezes remain individual sanctions targeting specific natural and legal persons. Nevertheless, especially as far as asset freezes are concerned, the nature and extent of the list of targets suggest that a shift along the continuum toward more comprehensive sanctions has occurred. The first travel bans and asset freezes imposed in March 2014 affected few specific individuals involved in the illegal annexation of Crimea. Over time, the list has been repeatedly extended (see figure 3) and encompasses, especially since February 2022, a significant number of natural and legal persons at the center of Russia’s political and economic activity. Above all, the freezing of assets of banks and financial institutions is likely to affect the entire population, which points to a more comprehensive scope of the sanctions.

Figure 2. Natural and legal persons targeted by asset freezes and travel bans (2014–2022).

Discussion of the empirical results

The empirical data clearly indicate that, overall, the design of EU restrictive measures against Russia shifted from targeted towards more comprehensive in 2022 compared to 2014. Drawing on the three potential drivers of sanctions’ designs – humanitarian, geopolitical, and domestic considerations – that we conceptualized in the theoretical section, we, in this section, analyze and discuss the shift from targeted to comprehensive sanctions through these three lenses.

The EU’s principled position is that restrictive measures shall pursue key objectives, i.e. democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, preserving peace and international security, and they should be designed in such a way that they minimize humanitarian consequences for the target population (European Commission Citation2022b, Citation2022e). Indeed, the vast majority of EU restrictive measures are targeted in design (Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2020) and especially the sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014 were predominantly targeted. They affected specific individuals and entities in addition to particular areas of the oil and technology sectors, while the costs for the general public were kept at a minimum. By adopting a targeted, ‘smart’ design, policy-makers, thus, minimized costs for the Russian population. As for the restrictive measures imposed since February 2022, the EU insists on their targeted nature and on the commitment to avoiding unintended consequences for the civilian population (European Commission Citation2022b). For this reason and in order to mitigate costs for the Russian population, the EU has manifold exceptions foreseen for certain types of sanctions (European Commission Citation2022e): Export bans and certain financial sanctions include, for instance, exemptions related to food security, humanitarian or medical purposes, as well as to the satisfaction of basic needs. Similarly, exceptions to the sanctions imposed on the Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine, among them Donetsk and Luhansk, related to humanitarian purposes were introduced in April 2022 (Council of the EU Citation2022). Humanitarian consideration are, thus, crucial for the EU when it makes design choices on sanctions and they are an important cornerstone in the set of restrictive measures against Russia.

Nevertheless, the gravity of Russia’s unprovoked military aggression of Ukraine resulted in the adoption of restrictive measures of unprecedented breadth and depth. The aim of these measures is to significantly weaken the Russian economy in order to ‘cripple the Kremlin’s ability to finance the war’ (European Commission Citation2022c). The increasing comprehensiveness of the sanctions imposed since February 2022 has led to concern about their unintended consequences for the Russian population (Moret Citation2022). The exact repercussions of the sanctions for Russia and its citizens are difficult to assess, not least because data and statistics on the Russian economy have become less transparent and harder to access since the beginning of the war (Milov Citation2022; Sonnenfeld et al. Citation2022). Nonetheless, some indicators can help to estimate the sanctions’ impact on Russia’s civilian population: sanctions targeting key economic sectors and industries resulted in output disruptions and related adverse effects on the labor market, along with a deterioration in the quality of life and in the living standards of Russian citizens (Milov Citation2022). Likewise, the comprehensive financial sanctions against Russian citizens and the unprecedented decision to sanction the central bank of a major economy are measures that will inevitably hurt the entire population (Moiseienko 2022; Moret Citation2022). The costs for the wider public were reinforced by restrictions in the transport sector which inhibit effective transport from and to the EU as well as by measures in other policy fields like educational issues (European Commission Citation2022c). Finally, the Council’s recent decision to suspend the Visa Facilitation Agreement with Russia (Council Citation2022) is yet another indication that minimizing costs for the target population may no longer be the EU’s priority. Hence, while the EU still pays strong attention to including humanitarian exemptions in its economic and financial sanctions against Russia and the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine, the comprehensive design adopted over the past months suggests that humanitarian considerations are no longer the main driving force for sanctions decisions.

The unprecedented comprehensive design of sanctions against Russia rather suggests that the EU, out of geopolitical considerations, seeks to maximize the costs for Russia and the Russian economy. Indeed, Russia’s unprovoked military aggression of Ukraine is clearly seen as an unprecedented threat to the international community, and the war’s geopolitical implications are a source of major concern for the EU (EEAS Citation2022). The EU is outspoken about the fact that it seeks to inflict the highest possible economic and political costs on Russia as a response to this significant threat (European Commission Citation2022c). This was made clear by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in her 2022 State of the Union Address when she spoke of the ‘toughest sanctions the world has ever seen’ which shall contribute to the outcome that ‘Russia’s financial sector is on life-support’ and ‘Russia’s industry is in tatters’ (European Commission Citation2022a). Compared to previous restrictive measures, the EU’s sanctions against Russia are designed in such a way as to maximize the costs for the target and to be punitive in nature (see also Moret Citation2022). This was confirmed by officials from member states’ permanent representatives in our background talks who observe a punitive rationale of the restrictive measures imposed on Russia – akin to the US’s approach towards sanctions – and quite in contrast to EU sanctions against other countries. The fact that the EU’s design choices and the accompanying Council Decisions were characterized by unprecedented swiftness and unity among the member states (background talks; Blockmans Citation2022; Moret Citation2022) indicates that the EU indeed pursued a rationale whereby it sought to explicitly and consciously maximize the costs for the target, i.e. Russia. Still, even if the sanctions against Russia are the most comprehensive ones ever adopted autonomously by the EU, they have not (yet) reached the extreme of a full-on embargo (Moiseienko 2022). The EU has (so far) been reluctant, for example, to adopt sanctions that could result in even higher costs for the Russian population like a complete travel ban for Russian citizens. This reluctance can be explained by the EU’s principled position to avoid humanitarian consequences and negative externalities for the broader population. However, the unprecedented breath and depth of the measures combined with the way their objectives are discursively framed suggest that EU sanctions aim at becoming increasingly comprehensive, costly, and punitive in order to be an appropriate response to Russia’s geopolitical threat in Europe and the world.

The comprehensive designs of the sanctions adopted by the EU over the past months implied majors costs and distributive consequences for the member states; suggesting that domestic considerations played a subordinate role in carving out a response to Russia. This was different in 2014 when the EU’s restrictive measures were much more targeted and affected a limited number of banks and companies in specific sectors and no import bans were in place. As was shown by Bĕlín and Hanousek (Citation2021), EU sanctions only had a minimal impact on European exports into Russia (see also Onderco and van der Veer Citation2021). Even though the 2014 sanctions resulted in distributive consequences among the EU member states (Giumelli Citation2017), some of the larger member states like Germany could absorb them and effects on the European economy were minimal (Schoeller Citation2020). This is different now, in 2022, where the unprecedented comprehensive sanctions, and especially the countermeasures, entail costs not only for Russia but also for EU member states. Again, in many respects it is too early to make an accurate prediction of the sanctions’ impact on the member states, not least because some of the more comprehensive sanctions, notably the import ban on Russian oil, have not yet become effective. But the close economic ties and ensuing dependencies between Russia and the EU until February 2022 (European Commission Citation2022d) imply that the breadth and depth of the imposed sanctions is likely to have negative externalities for the EU’s economies. Moreover, by having adopted these comprehensive measures, the EU accepted the risk of possible Russian retaliation (Moret Citation2022). Putin’s demand to pay for Russian gas in roubles or the suspension of gas deliveries via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline by the state-owned group Gazprom under the pretext of maintenance work are seen as examples for such Russian countermeasures (Sheppard, Ivanova, and Dempsey Citation2022; Strupczewski Citation2022). As was confirmed by staff members of the Council’s working party RELEX in background talks, the gravity of Russia’s aggression seems to have, at least to some extent, overshadowed national economic interests and domestic considerations. The European Commission’s unprecedented leading role in developing proposals for discussion and decision on the sanctions’ designs and their scopes since February 2022 is another indicator that domestic considerations played a subordinate role in recent sanctions decisions (background talks).

Conclusion

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, marked an unparalleled threat to the European and international order. The most recent developments, i.e. Russia’s declared annexation of Luhansk, Donezk, Cherson, Saporischschja (at the time of writing on 30 September 2022), indicate a continuing escalation. The EU’s response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine resulted in the by far most comprehensive sanctions it has ever adopted autonomously.

We document the entire set of EU restrictive measures imposed on Russia and the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine since 2014 and show the significant transformation of these sanctions from a rather targeted to an unprecedented comprehensive design in 2022. In order to explain this transformation, we conceptualized three potential drivers of EU sanctions design decisions: humanitarian, domestic, and geopolitical considerations. The EU’s principled position is to avoid humanitarian consequences for the sanctioned targets’ broader population and, indeed, this is reflected in the targeted design of the 2014 restrictive measures imposed on Russia and the humanitarian exemptions introduced in the 2022 set of sanctions against Russia and the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine. Yet, the priority of humanitarian considerations seems to have shifted in 2022 following the unprecedented threat imposed by Russia. The sanctions designs adopted in 2022 are, by far, much more comprehensive, entail major costs for the Russian economy and, thus, unintended consequences for the Russian population, and are punitive in nature. They reflect the EU’s geopolitical considerations to inflict major costs on Russia as a response to its military aggression against Ukraine. As a reaction to Russia’s continuing aggressive actions, the European Commission already announced an eighth sanctions package targeting further key economic sectors, including semiconductors and more goods generating significant revenues for Russia, as well as crucial services in architecture, engineering, judicial and IT-services (amongst other measures; Barigazzi and Kijewski Citation2022).

As sanctions are a major EU foreign policy tool, the empirical findings of this article contribute to the special issue’s key ambition of documenting and understanding the transformation of Europe after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Russia’s war on Ukraine likely transformed the priority foreign, security and defence policy has in the EU and our findings indicate that it transformed the way the EU employs sanctions. More specifically, we show that geopolitical considerations led the EU to adopt a more punitive rationale, maximizing the costs for the target – an approach it did not use to employ in previous restrictive measures. Unfortunately, current developments foreshadow a continuing escalation of the situation and an ongoing and even more intensive use of ever stronger sanctions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (106.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2023.2190105.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Our last check of EU restrictive measures against Russia was on September 27, 2022.

2. Our dataset documents restrictive measures adopted under the CFSP only. Where useful and appropriate in the context of this article, we also refer to ‘sanctions’ adopted in other EU policy fields.

3. The graph does not distinguish between observations introducing new sanctions and observations providing for derogations or amendments to the restrictive measures. For an overview of the amendments and derogations to the first Council decisions, regulations and annexes, please refer to the dataset.

4. Services bans were not included as they almost exclusively occur in conjunction with other sanction types (mostly with arms embargos, export bans and import bans).

5. We report the observations of EU restrictive measures against Russia without consideration of the measures imposed on the Russian-controlled territories in Ukraine. For an overview of the EU’s restrictive measures against the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine – Crimea, Sevastopol, Donetsk, and Luhansk – please refer to the dataset.

6. Services bans were not included as they almost exclusively occur in conjunction with other sanction types (mostly with arms embargos, export bans and import bans).

7. In and figure 3, we report EU restrictive measures against Russia without consideration of the measures imposed on the Russian-controlled territories in Ukraine. For an overview of the EU’s restrictive measures against the Russian-controlled areas in Ukraine – Crimea, Sevastopol, Donetsk, and Luhansk – please refer to the dataset and the online supplement.

References

- Allen, S. H., M. Cilizoglu, D. J. Lektzian, and Y. H. Su. 2020. “The Consequences of Economic Sanctions.” International Studies Perspectives 21: 456–564.

- Bapat, N. A., B. R. Early, J. Grauvogel, and K. Kleinberg. 2020. “The Design and Enforcement of Economic Sanctions.” International Studies Perspectives 21: 448–456.

- Barigazzi, J., and L. Kijewski 2022. “EU to Hit Russian Steel, IT Industry with Sanctions, but Spare Diamonds.” Accessed September 30 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-hit-russia-steel-it-industry-sanction-spare-diamond/.

- Bĕlín, M., and J. Hanousek. 2021. “Imposing Sanctions versus Posing in sanctioners’ Clothes: The EU Sanctions Against Russia and the Russian Counter-Sanctions.” In Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, edited by P. A. G. van Bergeijk, 249–263. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Biersteker, T., S. E. Eckert, M. Tourinho, and Z. Hudáková. 2013. Effectiveness of UN Targeted Sanctions: Findings from the Targeted Sanctions Consortium (TSC). Geneva: The Graduate Institute.

- Blockmans, S. 2022. Introduction. In: S. Blockmans (edited by): A transformational moment? The EU’s response to Russia’s war in Ukraine. CEPS – IdeasLab Special Report, 2–3.

- Council 2022. “Council Adopts Full Suspension of Visa Facilitation with Russia.” Accessed September 10 2022. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/09/09/council-adopts-full-suspension-of-visa-facilitation-with-russia/.

- Council of the European Union 2022. “EU Introduces Exceptions to Restrictive Measures to Facilitate Humanitarian Activities in Ukraine.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/04/13/eu-introduces-exceptions-to-restrictive-measures-to-facilitate-humanitarian-activities-in-ukraine/.

- EEAS 2022. “Taking Action on the Geopolitical Consequences of Russia’s War.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/taking-action-geopolitical-consequences-russia’s-war_en.

- European Commission 2022a. “2022 State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_5493.

- European Commission 2022b. “Commission Guidance Note on the Provision of Humanitarian Aid in Compliance with EU Restrictive Measures (Sanctions).” Accessed September 21 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/220630-humanitarian-aid-guidance-note_en.pdf.

- European Commission 2022c. “EU Sanctions Against Russia Following the Invasion of Ukraine.” Accessed September 12 2022. https://eu-solidarity-ukraine.ec.europa.eu/eu-sanctions-against-russia-following-invasion-ukraine_en.

- European Commission 2022d. “EU Trade Relations with Russia.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/russia_en.

- European Commission 2022e. “Humanitarian Aid. Frequently Asked Questions – as of 2 May 2022.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/faqs-sanctions-russia-humanitarian-aid_en.pdf.

- Felbermayr, G., A. Kirilakha, C. Syropoulos, E. Yalcin, and Y. V. Yotov. 2020. “The Global Sanctions Data Base.” European Economic Review 129 129: 103561. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103561.

- Giumelli, F. 2011. Coercing, Constraining and Signalling: Explaining Un and Eu Sanctions After the Cold War. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Giumelli, F. 2017. “The Redistributive Impact of Restrictive Measures on EU Members: Winners and Losers from Imposing Sanctions on Russia.” Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (5): 1062–1080. doi:10.1111/jcms.12548.

- Giumelli, F., F. Hoffmann, and A. Książczaková. 2020. “The When, What, Where and Why of European Sanctions.” European Security 30 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/09662839.2020.1797685.

- Giumelli, F., and M. Onderco. 2021. “States, Firms, and Security: How Private Actors Implement Sanctions, Lessons Learned from the Netherlands.” European Journal of International Security 6 (2): 190–209. doi:10.1017/eis.2020.21.

- Hafner-Burton, E. M., and A. H. Montgomery. 2008. “Power or Plenty: How Do International Trade Institutions Affect Economic Sanctions?” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (2): 213–242. doi:10.1177/0022002707313689.

- Hedberg, M. 2018. “The Target Strikes Back: Explaining Countersanctions and Russia’s Strategy of Differentiated Retaliation.” Post-Soviet Affairs 34 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2018.1419623.

- Hellquist, E. 2016. “Either with Us or Against Us? Third-Country Alignment with EU Sanctions Against Russia/Ukraine.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 29 (3): 997–1021. doi:10.1080/09557571.2016.1230591.

- Hufbauer, G. C., J. J. Schott, K. A. Elliott, and B. Oegg. 2007. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Karlović, A., D. Čepo, and K. Biedenkopf. 2021. “Politicisation of the European Foreign, Security and Defence Cooperation: The Case of the Eu’s Russian Sanctions.” European Security 30 (3): 344–366. doi:10.1080/09662839.2021.1964474.

- Manners, I. 2002. “Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?” Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (2): 235–258. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00353.

- McLean, E. V., and T. Whang. 2014. “Designing Foreign Policy: Voters, Special Interest Groups, and Economic Sanctions.” Journal of Peace Research 51 (5): 589–602. doi:10.1177/0022343314533811.

- Meissner, K. L. 2021. “Requesting Trade Sanctions? The European Parliament and the Generalised Scheme of Preferences.” Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (1): 91–107.

- Meissner, K. L. 2023. “How to Sanction International Wrongdoing: The Design of EU Restrictive Measures.” Review of International Organization 18: 61–85.

- Meissner, K. L., and C. Graziani. 2022. “Dataset: The Transformation and Design of EU Restrictive Measures Against Russia.” AUSSDA. doi:10.11587/Y0SMXO.

- Meissner, K. L., and P. Mello. 2022. “The Unintended Consequences of UN Sanctions: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Contemporary Security Policy 43 (2): 243–273.

- Milov, V. 2022. “Yes, It Hurts: Measuring the Effects of Western Sanctions Against Russia.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://www.globsec.org/news/yes-it-hurts-measuring-the-effects-of-western-sanctions-against-russia/.

- Moret, E. 2022. “Sanctions and the Costs of Russia’s War in Ukraine.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://theglobalobservatory.org/2022/05/sanctions-and-the-costs-of-russias-war-in-ukraine/.

- Onderco, M., and R. van der Veer. 2021. “No More Gouda in Moscow? Distributive Effects of the Imposition of Sanctions.” Journal of European Integration 59 (6): 1345–1363. doi:10.1111/jcms.13185.

- Portela, C. 2010. European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy: When and Why Do They Work. London, New York: Routledge.

- Portela, C. 2016. “Are European Union Sanctions „targeted“?” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 29 (3): 912–929. doi:10.1080/09557571.2016.1231660.

- Portela, C., P. Pospieszna, J. Skrzypczyńsk, and D. Walentek. 2021. “Consensus Against All Odds: Explaining the Persistence of EU Sanctions on Russia.” Journal of European Integration 43 (6): 683–699. doi:10.1080/07036337.2020.1803854.

- Portela, C., and T. van Laer. 2022. “The Design and Impacts of Individual Sanctions: Evidence from Elites in Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe.” Politics and Governance 10 (1): 26–35. doi:10.17645/pag.v10i1.4745.

- Saltnes, J. 2017. “Norm Collision in the European Union’s External Policies: The Case of European Union Sanctions Towards Ruanda.” Cooperation and Conflict 52 (4): 553–570. doi:10.1177/0010836717710528.

- Schoeller, M. G. 2020. “Tracing Leadership: The Ecb’s ‘Whatever It takes’ and Germany in the Ukraine Crisis.” West European Politics 43 (5): 1095–1116. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1635801.

- Sheppard, D., P. Ivanova, and H. Dempsey 2022. “Russia Cuts Gas Deliveries to Europe via Nord Stream 1.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/b193dc11-5069-41f5-ba86-2a83ea78f911.

- Sjursen, H. 2006. “The EU as a ‘Normative’ Power: How Can This Be?” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1080/13501760500451667.

- Sonnenfeld, Jeffrey, S. Tian, F. Sokolowski, M. Wyrebkowski, and M.Kasprowicz. 2022. “Business Retreats and Sanctions are Crippling the Russian Economy.” Accessed September 30 2022. 10.2139/ssrn.4167193.

- Strupczewski, J. 2022. “EU Payment in Roubles for Russian Gas Would Violate Sanctions Regime -Document.” Accessed September 21 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-payment-roubles-russian-gas-would-violate-sanctions-regime-document-2022-04-14/.

- Szép, V. 2020. “New Intergovernmentalism Meets EU Sanctions Policy: The European Council Orchestrates the Restrictive Measures Imposed Against Russia.” Journal of European Integration 42 (6): 855–871. doi:10.1080/07036337.2019.1688316.

- Tostensen, A., and B. Bull. 2002. “Are Smart Sanctions Feasible?” World Politics 54 (3): 373–403. doi:10.1353/wp.2002.0010.

- Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. 2022. “Sanctions Against the Russian War on Ukraine: Lessons from History and Current Prospects.” Journal of World Trade 56 (4): 571–586. doi:10.54648/TRAD2022023.

- Von Soest, C., and M. Wahman. 2015. “Are Democratic Sanctions Really Counterproductive?” Democratization 22 (6): 957–980. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.888418.

- Weber, P., and G. Schneider. 2020. “Post-Cold War Sanctioning by the EU, the UN, and the US: Introducing the EUSANCT Dataset.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 39 (1): 97–114. doi:10.1177/0738894220948729.