ABSTRACT

The Russian aggression against Ukraine brought energy security to the top of the European policy agenda. Existing literature suggests that the prioritization of energy security would come at the expense of climate policy. We argue that the EU’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine may constitute a departure from this pattern. Our assessment shows a higher level of coherence of objectives and instruments between energy security and climate objectives than the EU’s energy policy responses to previous crises with Russia, notably the gas supply crisis of 2009 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. While some uncertainty about final outcomes remains, we argue that change in several contextual conditions helps explain coherent policy outputs and make coherent outcomes more likely on the occasion of the present crisis.

1. Introduction

Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine brought energy security to the top of the EU agenda. On the one hand, the EU decided to gradually phase out Russian fossil fuel supplies to reduce Russia’s revenues that support its war chest (European Commission Citation2022e; European Council Citation2022a; Citationb; Citationc). On the other hand, Russia sharply reduced gas flows to Europe (Zachmann, Sgaravatti, and McWilliams Citation2022). As Russia was until 2021 the top supplier of coal, oil, and natural gas to the EU (Eurostat Citation2022), the beginning energy divorce brought about turbulence for the EU energy system and skyrocketing energy prices (European Commission Citation2022e, Citation2022a).

The energy security crisis has unfolded at a crucial time for the implementation of the EU’s climate-neutrality objective adopted in 2021. Synergies between energy security and decarbonisation exist – generally based on the reconfiguration of energy systems from imported fossil fuels towards renewable and nuclear energy and energy efficiency (Jewell, Cherp, and Riahi Citation2014). However, conflict may also arise, e.g. if imported fossil fuels are replaced by more emissive domestic sources or infrastructure policies consolidate carbon-intensive consumption patterns (Froggatt and Levi Citation2009). The likelihood of conflicts is especially acute when the two problems are perceived as working at different timescales (Adelle, Pallemaerts, and Chiavari Citation2009). Hence, hasty reactions to sudden energy security shocks might carry higher risks of creating inconsistency with long-term climate objectives. For the EU, several works have suggested that prioritizing energy security has in the past comes to the detriment of climate objectives (Dupont and Oberthür Citation2012; Strambo, Nilsson, and Månsson Citation2015).

Here, we investigate the extent of climate policy integration (CPI) into the EU’s response to the 2022 energy security crisis compared to previous crises with Russia – namely the 2009 supply disruption and the 2014 annexation of Crimea, attempting to explain change (or lack thereof) in CPI over time. Such a diachronic comparison will allow us to analyze under what conditions an energy security emergency is more or less likely to trigger policy responses that integrate climate considerations. To identify explanatory conditions, we draw on different theoretical standpoints including constructivism, rational choice, and historical institutionalism, grouping several explanatory variables for CPI under macro-conditions of ideational, material, and institutional nature and figuring out to what extent their evolution over time correlates with changes in the EU’s response to energy security crises.

We empirically focus on CPI into the EU’s external energy policy (EEP) response to energy security crises, as EEP lies at the core of the contentious intersection between climate and energy security. As external energy dependence and contestation of EU-Russia energy relations have risen over the last two decades (Krickovic Citation2015), EU EEP has traditionally been preoccupied with securing sufficient fossil fuel supplies (in particular, natural gas) (Tichý Citation2021). Meanwhile, climate policy targets have increasingly accentuated the need to drastically reduce and even phase out fossil fuel consumption and imports. The EU’s 2009 commitment to reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80–95% by mid-century only left room for limited residual fossil fuel consumption (European Commission Citation2011c), which was further reduced by the establishment of the 2050 climate-neutrality objective in late 2019 (European Commission Citation2018b).

We argue that the EU’s EEP response to the 2022 crisis shows a higher level of CPI compared to previous crises. EEP’s functional interrelations with climate mitigation have been recognized to a larger extent than in the past. Measures have taken climate priorities more into consideration and have tried to maximize synergy and minimize conflict between climate and incumbent energy security objectives. We argue that change in several contextual conditions – including threat perception, material interests, and policy and institutional frameworks – helps explain such higher level of CPI compared to previous crises.

Our work contributes to two strands of literature. First, we advance EEP literature by analyzing EEP through a climate lens. While climate/sustainability has formed an important element of the ‘energy trilemma’ alongside competitiveness and security (European Commission Citation2006), energy policy literature has so far addressed EU EEP mainly through the lenses of a tension between commercial and geopolitical objectives (e.g. McGowan Citation2008; Kuzemko Citation2014). Second, we contribute to a growing body of literature addressing the impact of crises and turbulence on climate policy and commitments. This literature has evolved from considering that the prioritization of other objectives is detrimental to climate objectives (Skovgaard Citation2014) to an appreciation of more complex interactions (Eckert Citation2021; Von Homeyer, Oberthür, and Jordan Citation2021). Yet, these latter contributions are still short of systematic assessments of specific policy areas. Our work fills this gap by applying the analytical concepts and instruments developed by CPI literature to EU EEP.

We pursue our argument in three main steps. First, we establish an analytical framework that (1) conceptualizes CPI into EEP and (2) introduces several explanatory conditions for CPI. Second, we assess CPI in the EU’s EEP outputs contrasting 2009 and 2014 with 2022. Third, we explore to what extent our assessment correlates with the evolution of various explanatory conditions. Finally, we discuss our findings and conclude, including reflections on possible future trajectories.

2. Conceptualising CPI in external energy policy

2.1 Conceptualizing CPI

Based on Lafferty and Hovden’s (Citation2003) definition of environmental policy integration (EPI), we define CPI as the incorporation of climate policy objectives across policy sectors. Policy integration was first conceptualized by Underdal (Citation1980) as occurring where a policy’s constitutive elements ‘are brought together and made subject to a single, unifying conception’ (Underdal Citation1980, 159). With the rising salience of cross-sectoral issues such as climate change, a demand for integrating them within sectoral policies emerged, giving rise to thematic conceptualizations of integration such as environmental or climate policy integration (EPI/CPI) (see Lafferty and Hovden Citation2003; Adelle and Russel Citation2013).

Literature on EPI and CPI has found different strengths of policy integration. Accordingly, weak CPI would merely require climate objectives to be considered in sectoral decision-making without mandating their reflection in relevant outputs and outcomes. In contrast, strong CPI would entail that climate objectives receive ‘principled priority’ (Lafferty and Hovden Citation2003), so that sectoral policies are fully aligned with climate priorities. Over the years, CPI has significantly advanced in the EU, even though not evenly across policy fields (Oberthür and von Homeyer Citation2022).

Whereas integration concerns all stages of policymaking (Underdal Citation1980), our analysis focuses on policy outputs. Literature on EPI and CPI has established the policymaking process itself as an important aspect of policy integration (notably considering aspects such as problem definition, or stakeholder involvement) in addition to policy outputs and outcomes (e.g. Selianko and Lenschow Citation2015; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). In line with our objective to investigate change in actual policy, however, we focus on coherence in outputs.

Based on the relevant literature (e.g. Nilsson et al. Citation2012), we propose focusing on coherence at two levels: policy objectives and instruments. Regarding objectives, the main question is whether and to what extent climate goals are recognised as guiding the sectoral policy under consideration. Actual levels of CPI may span a range from the absence of any mention of climate change and the exclusive pursuit of the incumbent objective (in our case: energy security) to the full recognition of climate as a central policy objective. Assessing CPI at the level of objectives reveals whether policy integration has been pursued intentionally, as it may also occur accidentally (Collier Citation1995), carrying the risk of trade-offs being ignored.

As for policy instruments, strong CPI would entail that sectoral policies fully align with the EU’s long-term climate objectives. The EU first established the political objective of an 80–95% emission reduction by mid-century in 2009. In 2019, it then agreed the 2050 climate neutrality objective. As such, building up on a previously adopted operationalization of CPI (Dupont and Oberthür Citation2012), we investigate the extent to which responses to energy security crises helped bridging the gap between the EEP status quo prior to the crisis and an ideal EEP that fully internalizes long-term climate objectives. An EEP response showing strong CPI would take policy instruments misaligned with climate objectives in line with long-term climate targets. A response showing weak CPI would fail to do so, but nevertheless move the status quo closer to a trajectory consistent with long-term climate targets. A response showing no CPI would maintain the status quo or go in the opposite direction.

Finally, we wish to highlight three caveats regarding our assessment framework. First, the framework focuses on the aggregate EU level, zooming in on the horizontal dimension of coherence (coherence between policy areas). While this can be considered problematic as EEP is largely under the competence of member states, a ‘creeping EU competence’ has been emerging (Mayer Citation2008), reinforced by energy crises (Batzella Citation2021). Second, our assessment focuses on long-term, structural response measures. Short-term emergency measures such as the temporary re-activation of coal power plants could lead to an increase in emissions (IEA Citation2022a), while energy rationing or the suspension of certain economic activities could lead to emission reductions (McWilliams and Zachmann Citation2022). However, we do not include emergency reactions in our assessment but focus on structural measures that shape the compatibility with climate objectives in the longer term. Third, we make use of the Commission’s own projections on emission reduction pathways to measure the alignment of policy instruments to climate objectives. These projections change over time. As such, our results might need to be reassessed in the future as new projections will be released.

2.2 Explanatory conditions

To explain the results of our assessment, we investigate important contextual factors that may enable or constrain CPI. While policy integration may be understood as an agency-driven process (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016), we build up on literature’s identification of factors likely to affect policy integration (e.g. Lenschow Citation2002; Jordan and Lenschow Citation2010) by enabling relevant actors to pursue CPI. To this extent, we focus on broader ideational, material, and institutional conditions that shape outcomes. Such broader conditions may not only help explain past outcomes but are also likely to shape their future development and stability.

First, ideas and narratives inform actors’ framing of problems. Problem framing – defined as a pre-existing cognitive representation which bounds actors’ rationality (Daviter Citation2007) – often serves as an indicator of integration or coherence at the input level (Underdal Citation1980; Selianko and Lenschow Citation2015; Kurze and Lenschow Citation2018). As such, it affects the prospect of CPI in policy outputs, in focus here. The framing of both the EEP incumbent objective (energy security) and the emerging objective (climate mitigation) can be expected to be relevant. If energy security is framed as a matter of external dependence, a resource-poor energy consumer such as the EU would be more likely to resort to climate-compatible domestic resources such as renewable energy sources (RES) and nuclear. Hence, we investigate whether external dependence constituted a relevant concern in the EU energy security discourse in the runoff to the different crises. Similarly, the perception of climate change as a security threat may support CPI in energy security responses, since it may address timescale inconsistencies as a major source of incoherence between climate objectives and more pressing problems (Levin et al. Citation2012). We hence investigate the level of securitization of climate change by relevant EU actors (European Commission, EU Council) – namely whether it has been ‘established as an existential threat, with a saliency sufficient to have substantial political effects’ (Buzan, Waever, and De Wilde Citation1997, 25).

The second group of variables considers the role of material interests in affecting the level of CPI in EEP (on the role of material interests in explaining policy integration, see Lenschow Citation2002). The costs and competitiveness of different energy resources may affect the extent to which the response to an energy security crisis aligns with climate objectives. In particular, we may expect higher levels of CPI where economic and other costs of fossil fuels are higher than climate-friendly alternatives such as renewable energy and energy savings, and vice versa.

Third, we appraise whether the international and domestic policy and institutional context are more or less favourable to CPI. Historical institutionalist accounts posit that institutions and past policy decisions create path dependencies and constrain actors’ options (Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Hence, stringent climate policy frameworks are expected to steer responses to energy security crises toward coherence with climate objectives. Frameworks at two levels appear to be particularly important for our purposes. First, the multilateral climate regime may support CPI in EEP to varying extents, not least given the long-standing EU leadership ambitions in this respect (Oberthür and Dupont Citation2021). Second, the level of ambition, priority and stringency of EU domestic climate policy, as not least visible in medium- and long-term climate targets, may affect CPI in EEP. Finally, we expect coherence to be affected by the strength of inter-departmental coordination mechanisms (Lenschow Citation2002; Lafferty and Hovden Citation2003; Selianko and Lenschow Citation2015). As historical institutionalism posits that critical junctures can challenge path dependencies (Hall and Taylor Citation1996), the varying severity of energy security crises may also affect CPI in policy responses. We therefore expect that a more severe energy security crisis may be correlated with higher levels of CPI, as it would strengthen the case for significantly reducing imports of fossil fuels. In contrast, mild crises might not lead to rethinking the role of fossil fuel imports.

2.3 Sources and methodology

Our analysis combines qualitative and quantitative methods, given the heterogeneity of the empirical material. It is primarily based on a content analysis of key EU documents, including Communications of the European Commission, Conclusions of relevant Council formations, legislation and legislative proposals, and declarations of political leaders. These documents allow us to identify and assess the level of CPI in objectives and instruments employed in response to the energy crises in focus. They also provide a suitable basis for analysing evolving norms, ideas and rules over time. We in particular focus on EU documents that constitute a direct reaction to the different energy crises and relate to the EU’s EEP. Furthermore, we base ourselves on existing literature and analysis, in particular for the investigation of ideational, policy and institutional factors. We quantitatively complement this focus on EU documents by employing official data regarding EU decarbonisation trajectories as a point of reference and open databases from Eurostat and Entsog in order to identify supporting data on the alignment of relevant policy instruments to climate objectives. These data also support our inquiry on the role of material interests included in our explanatory framework.

3. CPI in EU responses to energy security crises

3.1 Background: three crises and EU responses

Over the last decade, the EU has faced three major energy-relevant crises with Russia. In January 2009, Russia cut gas supplies through Ukraine as a result of a pricing dispute between the two countries. At that time, Russian gas accounted for 42% of EU imports, 80% of which transited through Ukraine. The disruption caused the EU to be deprived of 20% of their gas supplies, and 30% of imports, unevenly distributed across certain Eastern member states. The crisis-exposed weaknesses in the access to information and infrastructure capacity (European Commission Citation2009). As a result, the EU reformed its legislation on the security of gas supply (Regulation (EU) 994/2010) and adopted a screening instrument for intergovernmental agreements (IGA) on gas (Decision 994/2012/EU). To support route diversification, it reformed the Trans-European Network-Energy (TEN-E) Regulation supporting cross-border energy infrastructure (Regulation (EU) 347/2013), and allocated about EUR 1.4 bn in funding to new gas infrastructure under the European Economic Programme for Recovery (EEPR, Regulation (EU) 663/2009)

Renewed concerns over supply security emerged in 2014. Following the ousting of Ukraine’s then President Viktor Yanukovych, Russia annexed Crimea and supported the separation of territories in eastern Ukraine. The crisis did not impact energy flows from Russia, but a degradation in EU-Russia relations encouraged a reassessment of EU energy security risks associated with dependence on Russian gas. The Commission presented a European Energy Security Strategy (EESS) including security stress tests (European Commission Citation2014a). A new gas security package was adopted in 2017, including the introduction of intra-EU gas solidarity measures and a strengthening of the IGA Decision (Decision 2017/684/EU). Further initiatives included the LNG and storage strategy (European Commission Citation2016) and the EU’s first energy diplomacy action plan (Council of the EU Citation2015).

Finally, in 2022, a major energy security crisis in Europe resulted from the collapse of EU-Russia relations, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February. In 2022, Russian supplies were reduced from 40% to 9% of EU imports (Zachmann, Sgaravatti, and McWilliams Citation2022). Early on during the crisis, the European Council asked the Commission to prepare a roadmap for a mid-term phase-out Russian gas imports – then introduced as RePowerEU (European Commission Citation2022e) - while embargoes were adopted on imports of Russian coal, crude oil and oil products. The European Commission presented in May 2022 the RePowerEU Communication, including a set of short to mid-term actions on energy savings, renewable energy deployment and electrification, international energy relations and industrial transition (European Commission Citation2022e).

3.2 CPI in policy objectives

Across the crises, EEP responses showed a rising appreciation of functional interrelations between energy security and climate, with a sharp increase in the prominence of climate objectives in the response to the 2022 crisis. In the first EEP Communication following the 2009 crisis, climate was relegated to sparse references and diluted within a broader concept of ‘sustainability’ (European Commission Citation2011b). No interrelation was recognized, even though the link between energy and climate issues had been established in a 2006 Green Paper (European Commission Citation2006) and the Climate and Energy Package of 2008 (Skjærseth Citation2016). Some slight change occurred in the response to the 2014 crisis. The EESS framed energy security as ‘inseparable from other objectives’ including ‘competitiveness’ and ‘sustainability’ (European Commission Citation2014a, 1), however without references to long-term climate objectives. In both the 2009 and 2014 responses, the European Commission entrepreneurially identified synergies between energy security and the objective of deepening the internal market integration (Maltby Citation2013), but left climate objectives aside. A similar framing was reflected in legislation. For instance, the Security of Supply Regulation of 2010 entirely focused on the buildup of gas infrastructure redundancies (art. 6.1 of Regulation (EU) No. 994/2010). The Decisions introducing a screening of IGAs on gas exclusively focused on their compatibility with the internal market acquis. The 2013 reform of the TEN-E framework required eligible cross-border gas infrastructure projects to pursue just one out of multiple possible objectives (Art. 4.2b of Regulation (EU) No. 347/2013).

In contrast, decarbonization became a key objective to be pursued in response to the 2022 energy security crisis. The European Commission responded to the crisis with the RePowerEU plan, which fully recognized functional interrelations of energy security with the climate agenda. ‘Fast-forwarding the energy transition’ and the ‘swift implementation of the Fit for 55 proposal’ – notably a legislative package presented in 2021 to align EU legislation to the 2050 climate neutrality objective (European Commission Citation2021a) – were framed as the main, structural solution to the crisis.

3.3 CPI in policy instruments

The assessment of CPI in policy instruments requires an appropriate delimitation of the policy area in question and its related instruments. In the absence of a specific definition of EU EEP, we can distinguish four main fields of EU EEP on the basis of literature on EEP (e.g. Herranz-Surralles Citation2015) and energy security (e.g. Deese Citation1979; Cherp and Jewell Citation2011), as well as of EU documents on international energy relations (European Commission Citation2011b): energy diplomacy, referring to dialogue initiatives with energy producers; source substitution, referring to the promotion of alternative energy supplies; demand reduction, referring to the promotion of energy efficiency; and supply route diversification, referring to the support to energy connectivity with third countries.

Energy diplomacy: The dialogues with energy partners, which intensified in the aftermath of each crisis, contained more references to climate in 2022 than in the previous crises, although the record is mixed. Azerbaijan is a particularly illustrative case as the lynchpin of the EU’s Southern Gas Corridor initiative – a flagship diversification initiative launched by the 2008 Strategic Energy Review (European Commission Citation2008). In the context of this initiative, no reference to climate considerations was found in energy diplomacy efforts with Azerbaijan (European Commission Citation2011a). In contrast, a Memorandum signed on the Southern Gas Corridor expansion in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis referred to the EU’s active pursuit of gas demand reduction, restating the commitment to the 1.5°C objective of the Paris Agreement and dedicating significant room to clean energy cooperation. This included ‘future-proofing’ gas cooperation with references to a conversion to future clean hydrogen trade and cooperation in the field of the reduction of fugitive methane emissions, flaring and venting (European Commisson Citation2022g).

A similar trend can be observed with other suppliers. In the context of the degradation of EU-Russia relations following the 2014 crisis, an EU-US Joint Statement supported additional imports of US LNG into Europe, without mentioning climate issues (European Commission Citation2018c). During the 2022 crisis, an EU-US Joint Statement confirmed EU interest in additional supplies of US LNG, recalling the 1.5°C commitment and a commitment to decarbonising and future-proofing the gas supply chain (European Commission Citation2022b). The same shift took place with energy diplomacy initiatives in the Eastern Mediterranean region. In contrast to the EU-Egypt Strategic Partnership of 2018 (European Commission Citation2018d), the trilateral partnership of 2022 – with the addition of Israel – recalled climate commitments and did not refer to the establishment of new gas infrastructure, pushing for the optimization and decarbonisation of existing logistical chains (European Commission Citation2022c).

The case of Russia shows, however, a different picture. Crises translated into a loss of cooperation opportunities to decarbonise Russia’s energy sector. The crisis of 2009 brought additional focus on gas security in the EU-Russia Energy Dialogue – a structured technocratic exchange between EU and Russian energy officials launched in 2000 and covering all aspects of energy cooperation. At the same time, the dialogue governance was restructured to better reflect the emergence of the climate agenda, while a Partnership for Modernisation with a prominent green energy dimension was also introduced in 2010 (Larionova Citation2015). The crisis in 2014, however, resulted in a suspension of the Energy Dialogue that only left in place gas crisis management mechanisms (European Council Citation2014a). Similarly, the 2022 crisis translated into the end of any cooperative effort on climate and energy.

Source substitution and demand reduction: To assess the extent of CPI in source substitution and demand reduction policies responding to energy security crises, we measure whether responses to crises drove instruments promoting RES deployment (the EU Renewable Energy Directive and subsequent amendments) and energy efficiency (the Energy Efficiency Directive and subsequent amendments) closer to a strong CPI benchmark for 2030, with respect to pre-crises projections (see supplementary materials for sources and methodology).

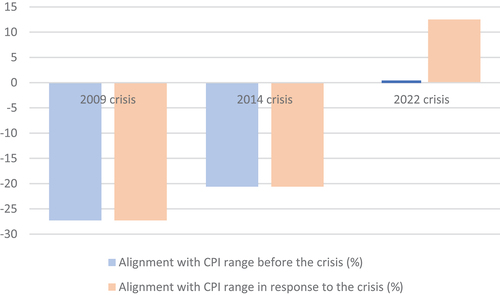

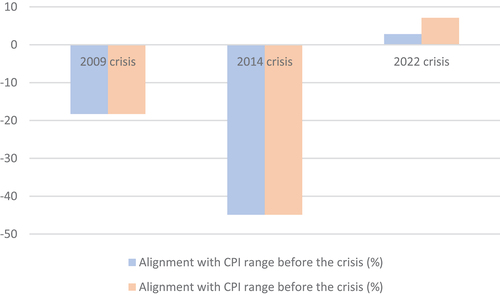

In contrast to past crises, the acceleration of RES deployment and demand reduction was pitched as the central response to the 2022 crisis. In the aftermath of the 2009 crisis, renewable energy and energy efficiency targets for 2020 agreed in 2008 (Council of the EU Citation2009) were not raised. Similarly, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, member states did not upgrade the 2030 renewables and energy efficiency targets (European Council Citation2014b) proposed by the Commission right before the annexation (European Commission Citation2014b). All in all, the two crises were not understood as a reason or an opportunity to upgrade climate commitments and take them closer to a strong CPI range (see ). In contrast, in direct response to the 2022 crisis, the Commission proposed to raise the 2030 RES deployment target contained in the Fit for 55 package of 2021 from 40 to 45%, and the energy savings target from 9% to 13%, with the stated objective of displacing up to 89.8 Mtoe of imported gas by the end of the decade (European Commission Citation2022e). If implemented, the reaction to the 2022 crisis would take RES deployment and energy savings on a pathway even more ambitious than the one predating the crisis, already consistent with a strong CPI range ().

Figure 1. CPI in EU response to energy security crises – resource substitution.

Figure 2. CPI in EU response to energy security crises – demand reduction.

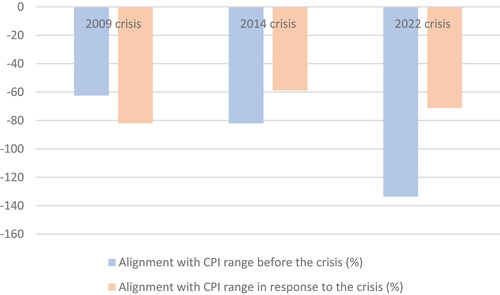

Diversification: Similarly, we assess the extent of CPI in route diversification by assessing gas import capacity additions against capacity pathways that are in alignment with long-term emissions reduction objectives. The assessment of capacity additions is based on the lists of EU Projects of Common Interest (PCI), adopted biennially via EU delegated regulations and allowing specific cross-border projects to access EU funding and benefit from administrative fast-tracking (Regulation (EU) 347/2013). Given the long lifetime of such infrastructure, additions exceeding a CPI range can be considered harmful with climate objectives as they contain the risk of asset stranding or carbon lock-in (Dupont and Oberthür Citation2012).

Based on this, the diversification component of the response to the 2022 crisis was overall more coherent with climate objectives than in past crises (), although still not fully in line with CPI (weak CPI). The first PCI list following the 2009 crisis (Delegated Regulation (EU) No 1391/2013) foresaw the addition of almost 84 Mtoe in alternative gas import capacity in the EU region served by Russian gas (Supplementary material, Table SM10). This accounts for a significant disconnection with demand projections incorporating EU long-term climate objectives (). Most of this support was maintained in the first PCI list following the 2014 crisis (Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/89), for about 43.7 Mtoe (Supplementary material, Table SM10). To be sure, the overall addition of supported gas import infrastructure in 2022 is not significantly lower than in responses to the previous crisis. The RePowerEU plan foresaw the addition of about 51.2 Mtoe of import capacity (European Commission Citation2022e). However, the net additions of gas infrastructure turned negative as additional import capacity was outbalanced by the withdrawal of 204.8 Mtoe of pipeline import capacity from Russia resulting from the decision to phase out all Russian fuel imports (Supplementary material, Table SM10). Additional pipeline infrastructure will also be required to be hydrogen-ready based on Regulation (EU) 2022/869, while floating storage and regasification units – accounting for up to 24.1 Mtoe of additional import capacity (European Commission Citation2022e) – can be leased or sold once no longer needed, which mitigates the risk of asset stranding or carbon lock-in.

Figure 3. CPI in EU response to energy security crises – gas diversification.

3.4 Results

Overall, our assessment indicates that the EU’s EEP response to the 2022 crisis displayed a significant improvement in CPI compared to previous crises. Action to maximize synergies between energy security and climate objectives was central in the EU response to the 2022 crisis, especially regarding import substitution and demand reduction, as the Commission proposed to bring RES and energy efficiency objectives CPI ranges. Conflicting solutions were present in the context of energy diplomacy and infrastructure policy, where – similarly to past crises – the 2022 crisis triggered a wave of gas diplomacy and gas infrastructure investment. Nevertheless, these measures were dwarfed by the decision to phase out Russian gas supplies, so that net additions would turn negative and take import capacity closer to demand reduction patterns. In addition, gas initiatives were accompanied by the recognition of trade-offs and action aimed at minimizing them.

Table 1. Presence of explanatory conditions: sources: own assessment based on analysis in the text.

4. Conditions for change

Ideas and narratives. Energy security framings in EU discourse were not particularly supportive of CPI across the different crises, and underwent no substantial change over time. No crisis took place in a context where supply security was seen as a matter of external dependence per se, as most EU EEP documents predating the different crises supported the increase in energy dependence on supplier countries other than Russia (European Commission Citation2008; Citation2011b, Citation2016). While a certain shift in tone could be detected when the notion of ‘strategic autonomy’ entered the EU parlance especially in the second half of the 2010s, this concept was dominantly applied to the areas of security and defense (European Council Citation2013; EEAS Citation2016) and later to ‘science, technology, trade, data, investment’ (Borrell Citation2020), remaining poorly connected to fuel dependence. All in all, in the few years preceding the 2022 crisis, energy security underwent a deprioritization (European Commission Citation2017) – losing prominence in EU energy policy documents and initiatives (European Commission Citation2019) – rather than a reframing.

In contrast, climate threat perceptions were more favourable to CPI in 2009 and 2022 – although to a larger extent in the latter case – than in the runoff to the 2014 crisis. Dupont (Citation2019) suggested that in the runoff to the 2009 supply disruption security language around climate change was adopted by the Commission and reproduced by the Council. These institutions framed climate change as a serious threat to international security. In contrast, towards the 2014 Crimea crisis, the European Commission’s continued attempts to frame climate change in security terms fell on less fertile ground in the Council (Dupont Citation2019). Securitization of climate rose again – and to a larger extent than in the first securitization wave of the late 2000s - towards the 2022 crisis. The Commission highlighted that climate change magnifies ‘the risks for instability in all forms’, warning of ‘large-scale irreversible climate impacts’ (European Commission Citation2018a, 2) affecting ‘security and prosperity in the broader sense’ (ibid.: 3). In this phase, the Council contributed to securitizing the climate discussion, repeatedly defining climate change as an existential threat requiring extremely and unprecedently urgent action (Council of the EU Citation2018a, 3; Citation2018b, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020; European Council Citation2019).

The material context. The material context was more favourable to CPI in 2022 than during previous crises. Both the crises of 2009 and 2013–14 unfolded against a context of relatively stable gas prices. Spot market prices in Europe did not exceed 30 EUR/MWh for the whole period, while most long-term contracts were still indexed to oil products. In contrast, the 2022 crisis took place against the background of highly volatile gas markets. The Dutch TTF Gas Futures index – the main reference for gas prices in Europe – fluctuated between 160 and 350 EUR/MWh from fall 2021 throughout 2022, while fundamentals point towards a ‘tighter for longer’ gas market outlook (IEA Citation2022b). Although to a lesser extent than gas, coal saw a similar rise in prices (IEA Citation2022a). At the same time, EU carbon prices were much higher in the early 2020s and clean energy alternatives have become more affordable and competitive than in previous crises (Lazard Citation2021). This context should favour responses privileging the fast deployment of alternative, clean energy sources over gas supply diversification to a larger extent than in the past.

The policy and institutional context. The institutional and policy context in 2022 was more favourable to CPI than in previous crises. The international climate regime lacked a stringent multilateral agreement during 2009 crisis, but the international community was gearing up for new negotiations in Copenhagen, driving renewed climate ambitions of the EU (Dupont and Oberthür Citation2012; Dupont Citation2019). Similarly, the international community and the EU were on the road to the Paris Agreement during the second crisis in 2014. The third crisis of 2022 then unfolded in the context of the 2015 Paris Agreement – strongly supported by the EU (Oberthür and Dupont Citation2021) – which set the objective of keeping global warming below 2°C and as close as possible to 1.5°C, requiring a downward revision of the role of fossil fuels in many energy transition pathways (European Commission Citation2018b). Domestically, the von der Leyen Commission taking office in 2019 put climate at the top of the EU policy agenda through the launch of the European Green Deal (Čavoški Citation2020). The strengthened 55% emission reduction target for 2030 and the 2050 climate-neutrality objective became collectively binding in 2021 via the European Climate Law – therefore reducing timescale inconsistencies that typically prevent CPI (Adelle, Pallemaerts, and Chiavari Citation2009). CPI was also strengthened, as the Climate Law obliged the Commission ‘to assess the consistency of any draft measure or legislative proposal (…) with the climate neutrality objective’ and the interim targets (art. 6.4 Regulation 2021/1119; see also Oberthür and von Homeyer Citation2022). A robust inter-departmental coordination between climate and energy policy emerged in 2014 when a Commission Vice-President overseeing a single Commissioner for Climate and Energy was installed (Bürgin Citation2020). Coordination was further reinforced under the Von der Leyen Commission which included an Executive Vice-President in charge of the Green Deal who at the same time led DG CLIMA and was hierarchically superior to the Commissioner for Energy in charge of DG ENER.

Finally, a certain congruence exists between the magnitude of the crises and CPI in the response. The relatively short 2009 crisis had a traumatic impact on a limited number of EU countries. However, it did not have a systemic economic effect on the continent (European Commission Citation2009), and its political fallout was limited. The 2014 crisis had political significance but very limited repercussions on energy security. In contrast, the 2022 crisis had both a systemic impact on Europe’s energy security architecture and economy, and was accompanied by a serious political crisis.

summarizes the analysis of explanatory conditions. The results indicate that a constellation of favourable material conditions, climate securitization, and institutional and policy context may be sufficient for the policy response to energy security crises synergizing with climate objectives. We can therefore speculate that these conditions matter, and assuming they continue makes us confident that the observed outcome will also be further implemented. However, we cannot, on the basis of our results, say to what extent they may be necessary or sufficient. Notably, some (sub)conditions are clearly not sufficient, as they did not correlate with CPI outcomes in the 2009 and 2014 crises. This is the case of climate securitization (2009, also in combination with a semi-ambitious international climate regime and a medium-strong crisis) and strong bureaucratic coordination (2014, with a semi-ambitious international climate regime). Finally, an energy security framing as a matter of dependence on external supply does not seem to be a necessary condition for CPI, as it was not present when CPI was detected.

5. Conclusion

The EU’s response to the 2022 energy crisis with Russia has resulted in more CPI in the EEP policy response than in past crises. The interrelation between EEP’s energy security objectives and climate objectives was fully recognized in the reaction to the 2022 crisis. Furthermore, synergies between energy security and climate objectives were actively pursued at the instrument level, especially in the substitution of imported energy with domestic sources, while remaining trade-offs with energy diplomacy and diversification were recognized and addressed, in contrast to the past.

Shifts in underlying ideational framings, material conditions, and political and institutional context help explain the increased CPI in the 2022 crisis – and enhance confidence that it will continue to shape the EU’s EEP as the present crisis evolves further. Notably, a rise in climate threat perceptions, a less competitive outlook for fossil fuels, and more stringent internal and external climate policy regimes have favoured CPI. In contrast, previous energy security crisis seeing low CPI in their response had also been severe and managed in close inter-institutional coordination. While these aspects have therefore not been sufficient for bringing about CPI in EEP, they may well contribute to a more favourable overall constellation. Hence, tighter inter-institutional coordination may arguably have contributed to stronger CPI in response to the 2022 crisis when the other aforementioned conditions were more favourable. Similarly, the severity of an energy security crisis or a favourable energy security framing may in itself not necessarily lead to domestic climate-compatible solutions but may do so if stringent policy frameworks constrain a resorting to polluting domestic alternatives such as coal or shale gas. While the dust has not settled yet, the enhanced conditions increase confidence that CPI will remain a prominent feature of EU EEP in the evolving response to the present crisis and beyond.

This study contributes to EEP literature by exploring EEP’s interplay with climate objectives. Our results suggest that climate mitigation has come to be recognized as deeply interrelated with energy security, while past energy security crises that only led to advances in the internal market integration agenda rather than the climate agenda. In this regard, further research is welcome to explore the entrepreneurial role of the European Commission in integrating different objectives into sectoral policies over time. In addition, as a contribution to literature on climate policy in times of crisis, our findings on the hard case of EEP suggest that the EU may have sufficiently entrenched climate priorities to make future reversals unlikely even in the face of problematic junctures, but further analysis may be required to probe and confirm this conclusion.

Nevertheless, a rapidly evolving context imposes limits in reaching firm conclusions. A European dash for non-Russian fossil fuels from developing countries risks undermining EU climate diplomacy efforts to motivate developing nations to decarbonise before reaching a more advanced industrial stage. Furthermore, for new gas infrastructure additions to minimize risks of carbon lock-in or asset stranding, sufficiently flexible import schemes will need to be adopted, in line with climate-compatible patterns of demand reduction. In this respect, gas exporters’ insistence on signing long-term supply contracts might constitute a risk. This especially calls into question the role of member states, whose energy security policies might diverge from the RePowerEU plan (see supplementary material, table SM10). This may call for further analysis of national-level diversification and energy diplomacy initiatives, exploring coherence from a vertical perspective and adds a caveat to the positive overall assessment of CPI in the EU’s EEP response to the current energy security crisis.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2023.2190588.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelle, C., M. Pallemaerts, and J. Chiavari. 2009. “Climate Change and Energy Security in Europe: Policy Integration and Its Limits.” SIEPS Report ( 4/2009). https://www.sieps.se/en/publications/2009/climate-change-and-energy-security-in-europe-policy-integration-and-its-limits-20094/.

- Adelle, C., and D. Russel. 2013. “Climate Policy Integration: A Case of Déjà Vu?” Environmental Policy and Governance 23 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1002/eet.1601.

- Batzella, F. 2021. “The Role of the Commission in Intergovernmental Agreements in the Field of Energy. A Foot in the Door Technique?” Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (4): 745–761. doi:10.1111/jcms.13129.

- Borrell, J. 2020. “Why European Strategic Autonomy Matters.” European External Action Service, 3 December 2020. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/why-european-strategic-autonomy-matters_en.

- Bürgin, A. 2020. “The Impact of Juncker’s Reorganization of the European Commission on the Internal Policy-Making Process: Evidence from the Energy Union Project.” Public Administration 98 (2): 378–391. doi:10.1111/padm.12388.

- Buzan, B., O. Waever, and J. De Wilde. 1997. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Candel, J.J.L., and R. Biesbroek. 2016. “Toward a Processual Understanding of Policy Integration.” Policy Sciences 49 (3): 211–231. doi:10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y.

- Čavoški, A. 2020. “An Ambitious and Climate-Focused Commission Agenda for Post COVID-19 EU.” Environmental Politics 29 (6): 1112–1117. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1784010.

- Cherp, A., and J. Jewell. 2011. “The Three Perspectives on Energy Security: Intellectual History, Disciplinary Roots and the Potential for Integration.” Energy Systems 3 (4): 202–212. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2011.07.001.

- Collier, U. 1995. Energy and Environment in the European. Union: The Challenge of Integration. Avebury.

- Council of the EU. 2009. “Conclusions.” 8434/09. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/misc/107136.pdf

- Council of the EU. 2015. “Conclusions on Energy Diplomacy.” 10995/15. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10995-2015-INIT/en/pdf.

- Council of the EU. 2018a. “Conclusions.” 6125/18. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6125-2018-INIT/en/pdf

- Council of the EU. 2018b. “Conclusions.” 12901/18. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12901-2018-INIT/en/pdf

- Council of the EU. 2019a. “Conclusions.” 6153/19.

- Council of the EU. 2019b. ‘Conclusions.” 12796/1/19. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12796-2019-REV-1/en/pdf

- Council of the EU. 2020. “Conclusions.” 5033/20. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5033-2020-INIT/en/pdf

- Daviter, F. 2007. “Policy Framing in the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 14 (4): 654–666. doi:10.1080/13501760701314474.

- Deese, D. A. 1979. “Energy: Economics, Politics, and Security.” International Security 4 (3): 140–153. doi:10.2307/2626698.

- Dupont, C. 2019. “The Eu’s Collective Securitisation of Climate Change.” West European Politics 42 (2): 369–390. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1510199.

- Dupont, C., and S. Oberthür. 2012. “Insufficient Climate Policy Integration in EU Energy Policy: The Importance of the Long-Term Perspective.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 8 (2). doi:10.30950/jcer.v8i2.474.

- Eckert, S. 2021. “The European Green Deal and the Eu’s Regulatory Power in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1111/jcms.13241.

- EEAS. 2016. “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe.” https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf

- ENTSOG. 2022. “Capacity Map Dataset.” https://www.entsog.eu/maps#transmission-capacity-map-2010.

- European Commission. 2006. “European Strategy for Sustainable, Competitive and Secure Energy.” COM/2006/105. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52006DC0105&from=EN

- European Commission. 2008. “Second Strategic Energy Review.” COM(2008)781.

- European Commission. 2009. “The January 2009 Gas Supply Disruption to the EU: An Assessment.” SEC(2009)977. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52009SC0977&from=EN

- European Commission. 2011a. “Joint Declaration on the Southern Gas Corridor.” 13 January 2011. http://gpf-europe.com/upload/iblock/bb6/20500c15d01.pdf.

- European Commission. 2011b. “On Security of Energy Supply and International Cooperation.” COM(2011)539. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2011/EN/1-2011-539-EN-F1-1.Pdf

- European Commission. 2011c. “A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050 - Impact Assessment.” COM(2011)112. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0112:FIN:EN:PDF

- European Commission. 2014a. “European Energy Security Strategy.” COM(2014)330. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52014DC0330.

- European Commission. 2014b. “A Policy Framework for Climate and Energy in the Period from 2020 to 2030.” COM(2014)15. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0015.

- European Commission. 2016. “On an EU Strategy for LNG and Storage.” COM(2016)49. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=COM/2016/49.

- European Commission. 2017. “Third Report on the State of the Energy Union.” COM(2017)688. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2017-11/third-report-state-energy-union_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2018a. “A Clean Planet for All.” COM(2018)773. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0773

- European Commission. 2018b. “In-Depth Analysis in Support of the COM(2018)773.” https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/depth-analysis-support-com2018-773-clean-planet-all-european-strategic-long-term-vision_en.

- European Commission. 2018c. “Joint US-EU Statement Following President Juncker’s Visit to the White House.” 25 July 2018. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/164062/joint%20us-eu%20statement%2025%20july%202018-en.pdf

- European Commission. 2018d. “Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership on Energy Between the European Union and the Arab Republic of Egypt 2018-2022.” https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2018-04/eu-egypt_mou_0.pdf.

- European Commission. 2019. “The European Green Deal.” COM(2019)640 .https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN.

- European Commission. 2021a. “Fit for 55: Delivering the Eu’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality.” COM(2021)550. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/chapeau_communication.pdf.

- European Commission. 2021b. “Proposal for a Directive on Energy Efficiency (Recast).” COM(221)558. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0558.

- European Commission. 2022a. “External Energy Engagement in a Changing World.” JOIN(2022)23. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=JOIN%3A2022%3A23%3AFIN&qid=1653033264976

- European Commission. 2022b. “Joint Statement Between the European Commission and the United States on European Energy Security.” 25 March 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_22_2041

- European Commission. 2022c. “Memorandum of Understanding Related to Trade, Transport and Export of Natural Gas to the European Union Between the European Union, the Arab Republic of Egypt, and the State of Israel.” https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/MoU%20EU%20Egypt%20Israel.pdf

- European Commission. 2022e. “RePowereu Plan.” COM(2022)230. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN&qid=1653033742483.

- European Commisson. 2022g. “Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership on Energy.” 18 July 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_4550

- European Council. 2013. “Conclusions.” EUCO 217/13. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-217-2013-INIT/en/pdf

- European Council. 2014a. “Conclusions.” EUCO 147/14. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-147-2014-INIT/en/pdf.

- European Council. 2014b. “Conclusions.” EUCO 169/14. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-169-2014-INIT/en/pdf.

- European Council. 2019. “Conclusions. EUCO 29/19.” https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41768/12-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf

- European Council. 2022a. “Conclusions.” EUCO 21/22 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/56562/2022-05-30-31-euco-conclusions.pdf

- European Council. 2022b. “Conclusions.” EUCO 1/22. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-1-2022-INIT/en/pdf

- European Council. 2022c. “Versailles Declaration.” https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/54773/20220311-versailles-declaration-en.pdf

- Eurostat. 2022. “Imports of Natural Gas by Partner Country.” https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do

- Froggatt, A., and M.A. Levi. 2009. “Climate and Energy Security Policies and Measures: Synergies and Conflicts.” International Affairs 85 (6): 1129–1141. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2009.00853.x.

- Hall, P.A., and C.R. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x.

- Herranz-Surralles, A. 2015. European External Energy Policy: Governance, Diplomacy and Sustainability. In SAGE Handbook of European Foreign Policy, K.E. Jrgensen, A.K. Aarstad, E. Drieskens, K. Laatikainen, and B. Tonra edited by, 913–927. SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781473915190.n63.

- IEA. 2022a. “Coal 2022 – Analysis and Forecast to 2025.” https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/91982b4e-26dc-41d5-88b1-4c47ea436882/Coal2022.pdf.

- IEA. 2022b. “Gas Market Report, Q4-2022.” https://www.iea.org/reports/gas-market-report-q4-2022.

- Jewell, J., A. Cherp, and K. Riahi. 2014. “Energy Security Under De-Carbonization Scenarios: An Assessment Framework and Evaluation Under Different Technology and Policy Choices.” Energy Policy 65: 743–760. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.051.

- Jordan, A., and A. Lenschow. 2010. “Environmental Policy Integration: A State of the Art Review.” Environmental Policy and Governance 20 (3): 147–158. doi:10.1002/eet.539.

- Krickovic, A. 2015. “When Interdependence Produces Conflict: EU–Russia Energy Relations as a Security Dilemma.” Contemporary Security Policy 36 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1080/13523260.2015.1012350.

- Kurze, K., and A. Lenschow. 2018. “Horizontal Policy Coherence Starts with Problem Definition: Unpacking the EU Integrated Energy-Climate Approach.” Environmental Policy and Governance 28 (5): 329–338. doi:10.1002/eet.1819.

- Kuzemko, C. 2014. “Ideas, Power and Change: Explaining EU–Russia Energy Relations.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (1): 58–75. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.835062.

- Lafferty, W., and E. Hovden. 2003. “Environmental Policy Integration: Towards an Analytical Framework.” Environmental Politics 12 (3): 1–22. doi:10.1080/09644010412331308254.

- Larionova, M. 2015. “Can the Partnership for Modernisation Help Promote the EU–Russia Strategic Partnership?.” European Politics and Society 16 (1): 62–79. doi:10.1080/15705854.2014.965896.

- Lazard. 2021. “Levelized Cost of Energy, Levelized Cost of Storage, and Levelized Cost of Hydrogen.” Lazard Insights, 28 October 2021. https://www.lazard.com/perspective/levelized-cost-of-energy-levelized-cost-of-storage-and-levelized-cost-of-hydrogen/

- Lenschow, A. 2002. Environmental Policy Integration: Greening Sectoral Policies in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Levin, K., B. Cashore, S. Bernstein, and G. Auld. 2012. “Overcoming the Tragedy of Super Wicked Problems: Constraining Our Future Selves to Ameliorate Global Climate Change.” Policy Sciences 45 (2): 123–152. doi:10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0.

- Maltby, T. 2013. “European Union Energy Policy Integration: A Case of European Commission Policy Entrepreneurship and Increasing Supranationalism.” Energy Policy 55: 435–444. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.12.031.

- Mayer, S. 2008. “Path Dependence and Commission Activism in the Evolution of the European Union’s External Energy Policy.” Journal of International Relations and Development 11 (3): 251–278. doi:10.1057/jird.2008.12.

- McGowan, F. 2008. “Can the European Union'‘s Market Liberalism Ensure Energy Security in a Time of '‘Economic Nationalism”?“ Journal of Contemporary European Research 4 (2): 90–106. doi:10.30950/jcer.v4i2.92.

- McWilliams, B., and G. Zachmann. 2022. “European Natural Gas Demand Tracker.” Bruegel Dataset, 7 December 2022. https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-natural-gas-demand-tracker.

- Nilsson, M., T. Zamparutti, J.E. Petersen, B. Nykvist, P. Rudberg, and J. McGuinn. 2012. “Understanding Policy Coherence: Analytical Framework and Examples of Sector-Environment Policy Interactions in the EU.” Environmental Policy and Governance 22 (6): 395–423. doi:10.1002/eet.1589.

- Oberthür, S., and C. Dupont. 2021. “The European Union’s International Climate Leadership: Towards a Grand Climate Strategy?” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (7): 1095–1114. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1918218.

- Oberthür, S., and I. von Homeyer. 2022. “From Emissions Trading to the European Green Deal: The Evolution of the Climate Policy Mix and Climate Policy Integration in the EU.” Journal of European Public Policy 0 (0): 1–24. doi:10.1080/13501763.2022.2120528.

- Selianko, I., and A. Lenschow. 2015. “Energy Policy Coherence from an Intra-Institutional Perspective: Energy Security and Environmental Policy Coordination Within the European Commission.” European Integration Online Papers 19 (2). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2554322.

- Skjærseth, J. B. 2016. “Linking EU Climate and Energy Policies: Policy-Making, Implementation and Reform.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 16 (4): 509–523. doi:10.1007/s10784-014-9262-5.

- Skovgaard, J. 2014. “EU Climate Policy After the Crisis.” Environmental Politics 23 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.818304.

- Strambo, C., M. Nilsson, and A. Månsson. 2015. “Coherent or Inconsistent? Assessing Energy Security and Climate Policy Interaction Within the European Union.” Energy Research & Social Science 8: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.04.004.

- Tichý, L. 2021. “A Comparison of the EU External Energy Relations with Angola and Tanzania.” International Politics 58 (2): 301–319. doi:10.1057/s41311-020-00253-5.

- Underdal, A. 1980. “Integrated Marine Policy: What? Why? How?” Marine Policy 4 (3): 159–169. doi:10.1016/0308-597X(80)90051-2.

- Von Homeyer, I., S. Oberthür, and A.J. Jordan. 2021. “EU Climate and Energy Governance in Times of Crisis: Towards a New Agenda.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (7): 959–979. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1918221.

- Zachmann, G., M. Sgaravatti, and B. McWilliams. 2022. “European Natural Gas Imports.” Bruegel Dataset, 20 september 2022. https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-natural-gas-imports.