ABSTRACT

The V4’s opposition to common internal migration policies has often been explained through their lack of affectedness by migration and their anti-immigrant publics. Yet, the V4 have taken a key role in external EU migration policies and become the third largest donor under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Through this theory testing case study, we argue that international standing and reputation, as well as an attempt to remain both responsive to their electorates and responsible towards their European partners, were key motivations in adopting this role. Our evidence suggests that the V4 supported external and border policies to demonstrate cooperativeness and responsibility to those European partners who had previously criticised their lack of solidarity. They did so in the external dimension, as this area was much less salient for their domestic audiences, allowing them to also remain responsive to domestic voters as well.

Introduction

‘Once your worldly reputation is in tatters, the opinion of others hardly matters.’ (Wilhelm Busch)

In the past decade, the waning of a ‘permissive consensus’ towards Europeanisation has become increasingly obvious. Nowhere is this more apparent in the EU than in the area of migration and asylum. Member States have controversially discussed issues of refugee distribution and reception, which has not only produced a long-standing deadlock of the asylum reform but even entailed a questioning of the use of qualified majority voting and thus primary EU law in this area (Zaun Citation2022).

Especially the Visegrád group (V4), consisting of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, has become notorious for opposing mandatory refugee quotas during the 2015 asylum crisis (Biermann et al. Citation2018; Gruszczak Citation2021; Koß and Séville Citation2020) and blocking the comprehensive reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) in 2018 (Zaun Citation2022). The V4 were led by populist governments who engaged in both anti-immigration and anti-EU rhetoric during domestic election campaigns (Gruszczak Citation2021; Koß and Séville Citation2020). It has been argued that the governments of the V4 adopted this obstructive approach for two reasons. First, to prove their point that the EU was weak and incompetent in finding solutions to the ‘refugee crisis’, and second, to demonstrate a strong defence of their national sovereignty and voter interests against intrusion from the outside (Öniş and Kutlay Citation2020; Zaun and Ripoll Servent Citation2022). The V4’s motives for opposing EU asylum policies post-2015 have been extensively studied (Gruszczak Citation2021; Koß and Séville Citation2020; Vaagland and Chmiel Citation2023); however, we know much less about the consequences of such contestation-processes on the inter-governmental and trans-governmental relationships between Member States within EU institution and whether the V4 perceive the ensuing reputational losses as a problem. While the rule of law crisis in Poland and Hungary would certainly suggest that the V4 hardly have any regard for saving their own reputation and should be a ‘least likely case’ (Gerring Citation2007, 115) for states caring about their reputation, we argue in this paper that the V4 have not become entirely uncooperative on EU migration policies and that they have even been among the frontrunners of intensified cooperation in the external dimension of EU migration policies, e.g. by contributing significantly to the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF Africa).

The V4 group’s support for such external measures is indeed puzzling for two reasons: First, the V4 do not benefit from the envisaged aim of the EUTF Africa of reducing irregular migration to Europe, as the V4 have almost no immigration from the beneficiary countries of the EUTF Africa. Moreover, these countries have no track record of being donors of development aid (Chmiel Citation2018, 14). Yet, the EUTF Africa is precisely an aid instrument that aims to support African countries’ development to address the root causes of migration (cf. Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2022). Second, their decision to contribute to EU funds stands in stark contrast to their populist governments’ anti-EU rhetoric, which was especially visible during the 2015/16 asylum crisis (Koß and Séville Citation2020). Hungary, for example, spent 3.1 million Euro on internal anti-immigration and anti-EU campaigns during the migration crisis (Köves Citation2018, 251) while simultaneously pledging more than three times that amount (9.4 million Euro) to the EUTF Africa (European Commission Citation2017). Against this background, the paper addresses the following specific research question: Why did the V4 support external EU immigration policies (especially but not exclusively under the EUTF Africa) after 2015?

We argue that their main reason was to compensate for their obstructive behaviour in the internal dimension of EU migration policy. More specifically, we engage with Peter Mair’s (Citation2009) idea of politicians needing to be both responsive and responsible in policymaking: While, of course, as right-wing populist governments they needed to be responsive to their voters’ anti-immigrant preferences and prevent any of the policies that would potentially mean that these countries would have to take in more refugees, their representatives at the EU level also needed to be responsible in that they needed to provide alternative narratives of how they felt the ‘EU migration crisis’ was to be addressed. To not lose credibility but maintain a coherent image, the governments then needed to prove through their action that they indeed stood by their word that migration to the EU was rather something to be addressed in the external than the internal dimension by providing significant financial support for this strategy which would make the V4 rank third as donors to the EUTF Africa. This was done to particularly mend their relationship with border countries to whom they repeatedly denied solidarity in the internal dimension. Cooperation on the EUTF Africa was unproblematic with regard to their responsiveness, as EU migration-development policies were entirely depoliticised (cf. Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2022) and therefore not contested at all among their publics.

Methodologically, we build a theory testing case study, formulating and testing hypotheses delineated from two theoretical approaches that highlight states’ balance of internal and external pressures. We raise expectations for V4 actions based on a theory on states’ needs to demonstrate internal responsiveness as well as external responsibility (Mair Citation2009), combined with the contrite tit-for-tat model which theorizes that states will attempt to regain good standing with other states when this is lost.. In terms of data, our analysis relies on 12 original interviews conducted between April 2020 and May 2022 with decision-makers from EU institutions and the V4, as well as civil society organisations in the V4 (see at end of document). As per agreement with our interviewees and due to the sensitivity of the issue in the V4, we refer to them exclusively as experts to ensure their anonymity. Moreover, we draw on 14 official joint statements from the V4, EU documents, press, as well as official development assistance (ODA) and immigration statistics.

Table 1. List of interviewees.

In the following, we present our theoretical framework which leans on game theoretical accounts of why states cooperate as well as Peter Mair’s (Citation2009) ideas on responsiveness and responsibility, and we present hypotheses for why the V4 supported an externalisation of migration, and contributed significantly to the EUTF, in the context of being in bad standing. Finally, we review the evidence and discuss the V4’s motivations for cooperating with the EU in the field of migration.

Theoretical framework: responsiveness and responsibility and how standing matters to EU member states

Mair’s (Citation2009) has argued that democratically elected governments need to be both responsive to voters and responsible in their actions. Being responsive is being part of their democratic accountability and contributes to the input legitimacy of their actions: ultimately, the government is representing ‘the people’ of its country and therefore needs to take their preferences into consideration, not least if it wants to ensure re-election. Responsibility refers to the adoption of policies and measures that are (potentially) effective and justified, i.e. that (also) have output legitimacy (Scharpf Citation1999). Mair’s (Citation2009) argues that achieving both at the same time is increasingly difficult for policymakers.

With the increase in Eurosceptic sentiment and the end of the ‘permissive consensus’ on the one hand and the high level of integration on many EU policy areas, the responsiveness versus responsibility (R&R) dilemma has also gained more prominence in EU studies (Lefkofridi and Nesi Citation2020; Verzichelli Citation2020). For populist governments, like those of the V4 in 2015/2016, the pressure to act responsive is particularly high. The main feature of populists is their self-proclaimed ‘hyper-responsiveness’, resulting from the fact that they criticise the ‘corrupt [Brussels] elite’ and present themselves as representatives of the will of ‘the pure people’ (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017, 6). Populists therefore arguably care mainly if not only about ‘input legitimacy’ of their policies. However, once they are in government, they will also be assessed on the success and the effectiveness of their policies, which suggests that they cannot entirely deny responsibility and adopt policies that go against the best interest of their own countries. Zaun and Ripoll Servent (Citation2022) have demonstrated that populist governments do sometimes act against the best interest of their countries, e.g. when Interior Minister Salvini blocked the Dublin IV reform to underline the EU’s inability to address the migration management crisis. They argue, however, that such an approach is only adopted when the costs of non-adoption of a policy are low, and the electoral gains of blocking are potentially high. We argue that the reputational costs or persistent blocking are indeed too high for any member state and that therefore member states that have repeatedly acted obstructive, need to signal cooperativeness at some point and in some areas. Put differently and in line with the R&R literature (Lefkofridi and Nesi Citation2020; Mair’s Citation2009; Verzichelli Citation2020): policymakers cannot act irresponsible all the time and they cannot always prioritise responsiveness and voter mobilisation over responsibility, i.e. effective policy outputs and good and productive relations with other EU member states. This would undermine their preferences when it comes to other policy areas, including distributive ones from which they benefit substantially such as cohesion policies or the COVID-19 recovery fund (Astrov and Holzner Citation2021, 14). They will hence show cooperativeness occasionally and especially when it is possible without antagonising their voters, i.e. in areas their voters do not care much about and that would not negatively affect their substantive agenda or the government’s standing in the public. Politicisation can be defined as making political decisions an objective of public discussion (Hackenesch, Bergmann, and Orbie Citation2021; Zürn Citation2014) and in the case of the V4, we expect that issues that would entail public discussions would be avoided:

H1:

The V4 governments seek to cooperate at the EU level on issues of low politicization domestically.

This means that, in a nutshell, governments both care about their standing among their domestic audience and voters and among other EU member states. Hence, V4 governments can largely antagonise the EU, but they cannot do so all the time, as they need to save enough of their reputation to ensure ongoing cooperation.

While much of the EU literature on reputation has taken a ‘logic of appropriateness’ lens and studied member state interaction from a more constructivist perspective (Adler-Nissen Citation2014, Citation2016; Lewis Citation2010), we take a more rationalist perspective and argue that reputation building has the aim of presenting oneself as a reliable cooperation partner to ensure continued cooperation. Indeed, International Relations’ scholars have argued that states need to present themselves as reliable partners if they are generally interested in cooperation. Fierce and persistent opposition may be associated with reputational loss, especially in a system like the EU, in which compromise and cooperation have been the norm (Novak, Rozenberg, and Bendjabballah Citation2020). States therefore need to demonstrate that they are ready to compromise and make constructive suggestions to policymaking to maintain a reputation of being cooperative. Being considered cooperative and constructive is particularly important for small states (like the V4) which have little material influence and, thus, rely on soft power and reputation to affect policy (Nye Citation1990). Their governments therefore may decide to forgo the short-term advantages of following their preferences on a single issue if it allows them to keep alive cooperation itself in the long-term (Keohane Citation1997). This is an alternative to neo-realism, which explains foreign policy in light of state goals and the relative power between states (Waltz Citation1979). Neo-realist accounts would explain investments in official development assistance as a way to achieve foreign policy goals, or as a way to limit migration to increase border security.

Novak, Rozenberg, and Bendjabballah (Citation2020) show that conflict resolution and compromise continue to be a norm in Council decision-making, even in instances where there are very large discrepancies in the interests. This arguably supports the idea of a tit-for-tat game applying in the EU context. The weakness of the tit-for-tat model is that it is an ideal form in which one defection from one player causes the whole system to unravel (Kydd Citation2015). The contrite tit-for-tat model is more flexible as it explains that in repeated cooperation, such the EU, states can signal contrition regarding their previous defection in order to restore their ‘good standing’ and to ensure the continuation of the system. States in contrition can invest in cooperation to regain ‘good standing’ (Signorino Citation1996) in one policy decision, to make up for costs accrued in a previous policy decision. They will seek to strategically invest in an issue-area where the specific actors with which they had lost good standing have great and homogenous interests. We also expect that they will try to compensate in policy areas rather close to those where they have previously incurred reputational losses to make a clear link between their contrition and their previous non-cooperation. They will try to support actors they have previously antagonised by helping them on issues that these specifically care about.

Hence, we expect that:

H2:

When the V4 show contrition for not cooperating in the field of asylum policy, they seek to invest in cooperation with the exact same actors they have lost ‘good standing’ with.

The states that the V4 arguably must make amends with include the border states Greece and Italy to whom they have repeatedly denied solidarity, including in the context of the second relocation decision which they have challenged before the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU Citation2020). There is evidence suggesting that V4 policymakers to an extent saw the need to support these countries, even through relocation, but that they were more critical towards supporting top destinations like Germany (or Sweden) as they had, according to the V4, self-inflicted problems, resulting from their too liberal approach to migration (Zaun Citation2018, 55–56).

In addition to the contrition strategy outlined above, states can attempt to regain good standing, or rather avoid bad standing, by redirecting the EU’s focus. By strategically ‘re-framing’ the problems under discussion (Daviter Citation2007; Rhinard Citation2017), they can attempt to move the negotiations away from the solutions they are unwilling or unable to compromise on, due to responsiveness to their domestic audiences. Re-framing entails changing the problem definition and thereby the perceived appropriate solutions to said problem (Rein and Schön Citation1996).

Indeed, there are different potential ‘problems’ that member states could identify regarding immigration to Europe: One problem is the unequal distribution of refugees which could be solved through redistribution of refuges. Another problem could be the high inflow of refugees to begin with for which solutions should rather be looked for in the external dimension, i.e. through border protection, external deals (like the EU-Turkey statement or the UK’s Rwanda deal) or through leveraging aid to ‘address the root causes of migration’ as suggested by the EUTF Africa (European Commission Citation2020). States like the V4 that are unhappy with the former problem definition can therefore be expected to try and shift the focus to the second problem definition.

For groups of small states to succeed in influencing policy, it is better to actively participate in policy formation, rather than in simply forming joint oppositional positions (Garai Citation2018). If, for instance, the EU moves away from discussions on the internal redistribution of refugees and towards externalisation and borders, the pressure on the Visegrád group regarding refugee distribution will diminish and their reputation will benefit. Moreover, by pushing for (alternative) solutions, they can be viewed as active and constructive partners in EU negotiations. This allows the V4 to both ease pressures towards them and restore their reputation as cooperative and constructive. Reframing therefore has a host of benefits, especially if it allows them to focus on policies that are not controversial in their domestic arenas and that hence don’t undermine the V4 governments to act response as well.

H3:

In issue areas where the V4 suffer from bad standing, they will attempt to reframe the issues.

Supporting the EUTF Africa as contrition strategy

We will now discuss the empirical evidence for the V4 contributing the EU’s external migration policy as a contrition strategy. The contrition strategy is a (possible) response to having lost good standing, and we therefore need to identify what caused the position of bad standing for the V4, before we analyse factors suggesting the contributions to the EUTF Africa are a result of contrition.

In 2015, the number of first-time asylum applicants in the EU more than doubled compared to previous years (Eurostat Citation2016). More than half of the 1.2 million asylum seekers who arrived in 2015 were Syrian, Afghan, and Iraqi (Eurostat Citation2016). As many of them travelled through Turkey into Greece or across the Mediterranean to Italy, these two border states bore the initial hosting burdens (UNHCR Citation2015). On 23 April 2015, the European Council held a special meeting on migration, at which point it had become an issue of growing concern for the Member States (European Council Citation2015b). One month later, the European Commission proposed the European Agenda on Migration, which, among several measures to address the growing number of immigrants, suggested the activation of an emergency system to better distribute asylum seekers among Member States (European Commission Citation2015). In a joint letter offered on 19 July 2015, the V4 advocated for voluntary emergency resettlement options (Joint statement Citation2015d). Even so, in September 2015, the European Council decided, by majority vote, to adopt two emergency relocation mechanisms, one, which was voluntary and based on pledges, and another one, which was based on mandatory, quota-based relocation (European Council Citation2015a). Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia heavily opposed quota-based relocation. While being opposed as well, Poland under its Christian Democrat government voted in favour of quota-based relocation, yet, the right-wing populist Law and Justice government taking over in November 2015, later joined Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia in criticising the adoption of quota-based relocation and opposing any attempts of making such a scheme permanent (Fomina and Kucharczyk Citation2016). In December 2015, Hungary and Slovakia, supported by Poland, formally requested that the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) annul the 2015 Council decision on emergency relocation, arguing that quota-based relocation should have never been adopted under qualified majority voting for being such a sensitive issue. This request was dismissed by the court on 6 September 2017 (CJEU Citation2017).

In June 2017, the European Commission announced that, despite their repeated calls for action, the V4, with the exception of Slovakia, remained in breach of their legal obligations to the relocation scheme and had shown disregard for their commitments to Greece and Italy and other Member States (European Commission Citation2017). Slovakia had accepted a few asylum seekers at this point and made promises to be more cooperative in the future (Euractiv Citation2018). By December 2017, there had been no changes in the relocation numbers to Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic, so the European Commission referred them to the CJEU for not accepting their share of the mandatory asylum seeker quotas (CJEU Citation2020). We see clear evidence of strained relations between the V4 and the EU as a result of the former’s refusal to cooperate on relocation. The V4 was in a position of bad standing vis-à-vis the European Commission and the specific Member States that shouldered the main burden of hosting asylum seekers.

Just one week after the European Commission referred the V4 to the CJEU for not taking in their share of relocated asylum seekers in December 2017 (European Commission Citation2017), the V4 increased their contribution to the EUTF Africa more than ten-fold (Interview 12). The fund was established two years prior, in November 2015, at the Valletta summit. Together with the EU-Turkey Statement, the EUTF Africa was one of the main policy instruments designed as a response to the 2015 crisis (Bøås Citation2021; Spijkerboer Citation2021; Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2022).

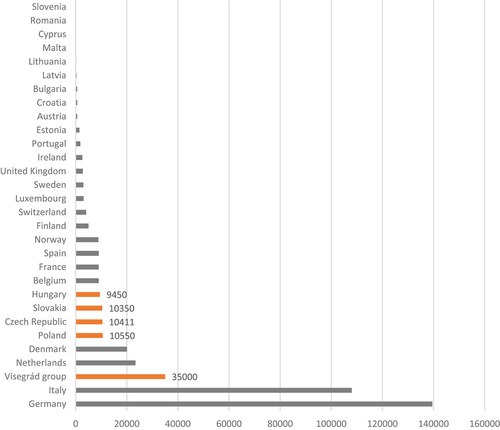

When the EUTF Africa was first established, the V4 made a joint contribution of 3 million Euros (European Commission Citation2016), which was the minimum amount needed for the V4 to secure voting rights in the fund (Interview 11). Their original contribution was a little more than the V4’s Central and Eastern European neighbours and in line with their previous engagement in the area of development policies (Interview 2). However, after they, as we argue, wanted to make up for their bad standing caused by the relocation issue, each of the V4 increased their funding significantly which eventually made them one of the top ten contributors to the fund, ranked only after only Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

Indeed, the timing of this significant increase in contributions suggests that the V4 made these contributions in order to mend their reputation which had severely suffered after the Commission initiated an infringement procedure for non-implementation of the second relocation decision and hence for a lack of solidarity with Italy and Greece. By 2017, the effects of the migration management crisis in Europe had largely waned, and the increase can therefore not necessarily be understood as a response to an intensification of migratory flows.

Moreover, the contributions coincided with a serious depletion of the North of Africa Window of the EUTF Africa (Euroactiv Citation2017). This depletion caused concerns for Italy, which had invested large sums in the fund and relied on cooperation with North African states to limit immigration. Italy was one of the main actors the V4 wanted to demonstrate contrition towards, and according to our hypothesis 2 we should therefore expect the V4 to contribute specifically to policies they care about, i.e. the North of Africa Window. In their initial contributions to the EUTF Africa in 2015, only Slovakia and the Czech Republic specified which of the three regions related to the fund they wanted to contribute to. Hungary and Poland did not provide specific information about where they wanted to invest, and their contributions were ultimately given to the regions that Slovakia and the Czech Republic supported (Interview 11). This, again, suggests that at the time the V4 contributed to go along, but did not have any strategic interests in the EUTF Africa. In , the contributions are listed by year and target region. When the V4, in 2017, decided to increase their contributions, the V4 all contributed to the North of Africa region, which we consider evidence for our hypothesis. Indeed, the increase in funding was preceded by a conflict between the V4 and Italy in which the V4 had partly recognised the need to show more solidarity with Italy, while criticising it for it for its lax approach towards irregular migration. A few months prior to the increased donations, in July 2017, the V4 Prime Ministers addressed a letter to Italian Prime Minister Gentiloni, acknowledging the burden on Italy, committing the V4 to providing certain forms of assistance to Italy, but also encouraging Italy to close its borders to illegal migrants (Joint statement Citation2017c). Gentiloni responded that Italy would not take lessons from the V4, and that Italy had the right to demand solidarity from other Member States (Ansa Citation2017). In December, the heads of government of the V4 and Italy met in Brussels to resolve matters, and the solution that was decided upon was a 36 million Euro donation to Italian led operations in Libya via the EUTF (Il Sole 24 ore Citation2017b). The increased contributions to the North of Africa region of the EUTF were viewed, by Italy and the European Commission, as the V4 attempting to make up for a lack of solidarity along the internal dimension (Interview 12). As one Italian newspaper put it: ‘In making its donation yesterday, the Visegrád Group hopes to express European solidarity with economic aid, rather than by taking refugees’ (Il Sole 24 ore Citation2017a). European Commission President Juncker praised the V4’s increased contributions to the fund, saying their donations were ‘proof that the Visegrád countries are fully aligned when it comes with solidarity with Italy and with others’ (Euroactiv Citation2017).

Table 2. V4 pledges to the EUTF by region (European Commission Citation2016, Citation2021).

These findings indeed suggest that the V4 made their donations to the EUTF Africa with a view of appeasing the EU and especially the member states most affected by their lack of solidarity. They tried to make up for a lack of solidarity in the internal dimension and refugee distribution by providing more solidarity in the external dimension and regarding the ‘root causes of migration’ and border protection, the latter being the focus of the North African window (Pacciardi and Berndtsson Citation2022). This was a window that especially Italy, being located in close proximity to North Africa, cared about and that recently had experienced resource depletion. This supports our second hypothesis, suggesting that for contrition, EU member states need to make amens with those member states which have specifically suffered from previous uncooperative behaviour in order to potentially regain good standing. While certainly other member states, including Italy, would not completely forget about the V4’s previous behaviour, especially the European Commission did acknowledge the gesture. Several Italian newspapers mentioned the donations by the V4 and reported that Gentiloni thanked the group, but that the countries still remained distant on the issue of relocation (see Il Sole 24 ore Citation2017b).

In many of the EU’s documents, the V4 are, moreover, listed as a group. This was a strategic move insisted upon by the V4 governments, as explained by one of our informants:

[The V4] wanted to have proper visibility for this project, for it was quite a lot of money. So, [the V4 governments] discussed with the Commission how to do it and then, well their final proposition was to have their special line for Visegrád countries, but at the same time to count this common contribution quartered, to be counted once more in individual contributions. (Interview 10)

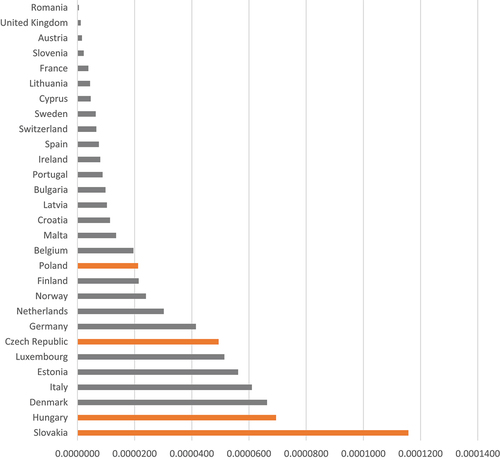

This was arguably a smart move, because as a group they ranked third among the contributors and so would be really perceived as one of the top donors to the EUTF Africa, whereas individually they only ranked fifth to eighth. At the same time, they were often perceived as a bloc in this policy area, as they also had incurred their reputational losses as a group when opposing intra-EU solidarity. illustrates the new contributions of the V4 compared to other Member States. Controlling for GDP, Slovakia and Hungary even become the biggest donors under the EUTF Africa altogether (European Commission Citation2021; see figure in Appendix).

Figure 1. Contributions to the EUTF in thousands of euros (European Commission Citation2021).

We do not find any evidence that supports a neo-realist explanation of V4 actions (Waltz Citation1979). There is no evidence that the V4 would follow self-serving goals by contributing to a policy that aims at reducing migration. With the exception of Hungary, none of the V4 nations experienced increased immigration in 2015 from the countries that the EUTF covers, and Hungary was able to reduce migration dramatically within several months through the approach described above (cf. Zaun Citation2018). In 2015, the V4, combined, only processed a total of 186.195 asylum applications (174.435 of which were in Hungary) (Eurostat Citation2022). In 2017, the year the V4 increased its funding to the EUTF, the total number was down to 7.410 asylum applications (Eurostat Citation2022). The timing and geographical focus (on Africa from which the V4 experienced very little illegal migration (MAC (Citation2018), 90)) of the EUTF suggests that the V4’s contributions were not motivated by a desire to minimise the number of immigrants to the V4. Indeed, one expert even argues that their new commitment ‘didn’t arise from for example a common strategy on external migration, because there is none’ (Interview 6). So, again, it was not substantive goals which the V4 pursued, rather their contribution was purely symbolic and aimed at making up for previous uncooperative behaviour.

Moreover, we do not find any evidence suggesting that the V4’s support for external policies was founded on any existing development strategy, i.e. they did not even have a substantive interest in contributing to African development. In fact, the V4’s sudden interest in an external strategy for North Africa came as a surprise to many observers (Interview 6; Chmiel Citation2018). The V4 had little presence in the region (Interview 1). For example, only Poland of the V4 had an embassy in the North of Africa window recipient-country Tunisia (Chmiel Citation2018, 9). Moreover, the V4 have historically never been a significant contributor to development. The ODA provided by the V4 ranks fairly low among contributors in the EU. In 2018, for instance, out of the 26 member states, Poland was ranked as number 12, the Czech Republic 15, Hungary 17, and Slovakia 19 (OECD Citation2024). Finally, the countries that usually provide similar levels of development aid to the V4 are Slovenia, Latvia, Austria, and Romania. These countries all rank among the 10 least contributing countries to the EUTF Africa (see ). Normally, one would expect the V4 to make contributions at a similar level. This suggests that the V4 are new to being top contributors to development aid, indicating a change in their policy.

Figure 2. Contributions to the EUTF as a share of GDP (European Commission Citation2021).

Supporting the external dimension of migration policy as a re-framing strategy

There is evidence suggesting that the V4 engaged in strategic re-framing of migration policy by systematically endorsing externalisation (of which the EUTF Africa is one example), and by persistently opposing internal solutions. We argue that their systematic endorsement of external solutions should be understood as a strategy to regain a position of good standing in the EU by shifting the focus away from a policy they could not accept if they were to be responsive to their constituents.

The V4 have consistently opposed the idea that the mandatory, quota-based relocation of asylum seekers from Italy and Greece could be a solution to the migration crisis since the European Commission initially proposed it in May 2015. The V4 challenged relocation on five grounds: 1) Its adverse effects making it an ineffective tool to address the migration crisis; 2) its divisiveness; 3) the use of the qualified majority when adopting such a decision; 4) the implications of such a policy for national sovereignty; and 5) its incentivisation of migration and serving as a pull-factor. For instance, in their joint statements, the V4 argued that relocation was ineffective and even a pull-factor creating more immigration (Joint statement Citation2015d, Citation2016b, Citation2017a). In response to the European Commission’s proposal in April 2015, the V4 wrote, ‘We do not deny the spirit of solidarity, but we firmly argue the contradictory effects and pull factors of a possible mandatory redistribution scheme for asylum seekers’ (Joint statement Citation2015d). In July 2017, the V4 wrote that mandatory relocation had not had the desired effects, because it had not contributed to easing the migratory pressure to Europe (Joint statement Citation2017b).

The V4 also argued that relocation created a division in Europe: ‘[The] introduction [of relocation] has even led to unnecessary divisions among the Member States’ (Joint statement Citation2016). Furthermore, the V4 criticised the decision-making procedure, claiming that majority voting undermined the adoption of unifying solutions (Joint statement Citation2018). Finally, the V4 argued against relocation because it challenged the sovereignty of the Member States (Joint statement Citation2016, Citation2018). They asked that the establishment of EU migration policy tools, such as Frontex should balance EU powers and Member States’ sovereign competences (Joint statement Citation2016).

While discouraging the use of relocation, the V4 framed strengthening the borders and comprehensive external policies as the most relevant tools with which to address the migration crisis (Joint statement Citation2015c, Citation2016a; Citation2016b). In a joint statement (Citation2016), the V4 ask the EU to adopt viable and constructive measures instead of imposing relocation. At the same time, they emphasised that they were committed to supporting any results-oriented and effective solutions (Joint statement Citation2016), thereby signalling again that relocation was neither result-oriented nor effective but also that they were cooperative. The V4 consistently expressed their conviction that providing steady and sustainable conditions in the countries of origin in terms of economic and social development and, thus, the prospect of future prosperity is crucial in the efficient management of the migration crisis (Joint statement Citation2015c). They considered the protection of the external border to be a prerequisite for a functional EU asylum and migration policy as such, as well as being integral to securing Schengen (Joint statement Citation2015c). In June 2015, the V4 explicitly recommended a systematic and geographically comprehensive approach to addressing increased immigration (Joint statement Citation2015d). Ahead of the Valetta summit in November 2015, the V4, with the exception of Poland, which was changing governments at the time, made a joint statement in which they reiterated their commitment to cooperation with third countries. They also welcomed the Valetta Summit and promised to contribute financially in this regard (Joint statement Citation2015c).

To show consistency and thus increase their credibility, the V4 not only framed external policies as the best solution to the ‘problem’ of migration, they also invested financially in external policies. A Czech expert explained that the Czech Republic would continue funding projects in third countries:

To give some more ratio to our commitment to the external approach, we will keep providing strong financial assistance to third countries. And let us hope that, after this, we will not be seen as the black sheep of the union, not willing to take people in the framework of the relocation decision. (Interview 1)

Even Hungary, the most vocal EU opponent domestically, was identified as having a very active delegation in Brussels, constructively proposing alternative solutions to quotas at the EU level, especially in the external dimension (Interview 6). The V4 were strategic in making policy suggestions that were constructive and that were agreeable to all, in an attempt to change their image among EU actors. One interviewee put this as follows: ‘From the very beginning, we did push this [external] approach, emphasising the role of “root causes” and that we are ready to be active in this field and that we can prove it by our actions’ (Interview 1). Another one explained that the V4 governments’ biggest interest was to be ‘as active as possible in the areas identified by the Commission, or by the most important Member States’ (Interview 10). In our review of the data, we could not find any instances of the V4 explicitly supporting internal European solutions such as redistribution, nor did we find any cases of the V4 opposing externalisation of migration control.

Instead of laying low in the policy field where they were perceived as highly uncooperative by other Member States, the V4 made migration policy a priority in their communications and were very active in the EU negotiations, developing suggestions and showing initiative. For example, immigration was very often addressed in their joint statements in the 2015–2017 period. Of 34 joint statements in the period from July 2015 to December 2017, one-third explicitly focus on migration. Among these, migration is often listed as the first issue on the agenda. Furthermore, at least one of the V4 governments placed a Seconded National Expert in the European Commission to work on migration policy after 2015 (Interview 1). The V4 made concrete migration policy suggestions to the EU ahead of Council meetings, and they initiated their own migration-related programmes. The V4 proposed ‘flexible solidarity’ (Joint Statement of the Heads of Governments of the V4 Countries Citation2016) as an alternative to mandatory quotas. Ahead of the December 2015 Council, the V4 asked the Council to focus on the root causes of migration, and they launched the Friends of Schengen Group (Joint statement Citation2015e). The Friends of Schengen group, though being a voluntary, informal ad-hoc group open to all member states, consisted of only the V4 and it wanted to contribute to securing the EU’s external borders in order to safeguard Schengen. This highlights again that the V4 signal to other member states and the EU institutions how much they care about the EU and its acquis, and that there questioning of internal solidarity is not the same questioning cooperation within the EU in general. One informant suggested that the V4 viewed ‘engagement in the external dimension as our gesture of solidarity.’ (Interview 10).

One element of the V4’s support of external migration policies can be said to have more direct substantive benefits for the group and thus lends support to a rational choice explanation. They proposed closer cooperation with the Western Balkans with a few to shifting the focus to the EU’s (immediate) borders (Joint statement Citation2015a; Citation2015b; Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Citation2015e; Citation2016a). For instance, they suggested to provide the Western Balkans with bilateral support in the practical handling of migration issues (Joint statement Citation2016). The V4’s focus to the Western Balkan route makes sense substantively, as these are countries in the V4’s immediate neighbourhood with which they cooperate, and migration flows through these countries would also pass through Hungary (Frontex, Citation2024).

The V4’s support of Frontex and the European Union Agency for Asylum (EASO) is, however, very much in line with their strategy of supporting external policies as an act of solidarity, rather than seeking immediate gains. They nominated an additional 75 experts (300 experts in total) to Frontex and to EASO, to strengthen border management (Frontex Citation2016; Joint statement Citation2015c). However, the V4 themselves signal that securing the border is the responsibility of each state. During the orchestrated migration crisis on the Polish-Belarus border in 2021, Poland refused the offer of assistance from Frontex and EASO, and instead demonstrated strong willingness to secure its border independently (Vaagland and Chmiel Citation2023).

There is clear evidence that the V4 faced severe pressure at the EU level to adopt a more constructive approach and that they could not simply adopt the anti-EU and anti-immigrant rhetoric they used in the domestic arena. One of our interviewees suggests:

[…] You can see, in the Polish media and in the Hungarian media, this Euroscepticism, but then, once the Minister comes into the Council and is part of the meeting, he or she has to have arguments in the discussion. And it is not sufficient to say that ‘we are opposing’. (Interview 6)

This suggests that the V4 needed to adopt an alternative approach to the migration issue in Europe, rather than being inactive and simply opposing what the other Member States suggest. Representatives of V4 Member States were indeed fully aware that other Member States and representatives from the EU institutions considered them the ‘black sheep’ of EU migration policy (Interview 1; Interview 8). Hence, the Visegrád governments wanted to be viewed as constructive by suggesting policies that they could adopt without antagonising their constituencies and contribute to, thus shifting the debate away from quotas (Interview 1).

To conclude on the strategy of reframing, we find evidence to support hypothesis 3. The V4 did engage in reframing of migration policy, a policy area where they suffered from bad standing. Their reframing strategy consisted of being very active in the discussions on migration in the EU, by prioritising this issue area in their communications where they systematically opposed internal measures and consistently supported external policies. Furthermore, they increased the credibility of their framing of the external dimension as the relevant solution to migration by investing in external policies both financially and in terms of personnel, even though they themselves do not directly benefit from these policies.

Choosing issues of low domestic salience

Existing literature has documented how immigration in general, and relocation in particular was highly politicized in the V4 countries after 2015 (Gruszczak Citation2021; Koß and Séville Citation2020; Vaagland and Chmiel Citation2023). As populist governments, highly responsive to public sentiment, we argue it was impossible for the V4 governments to rebuild their good standing by compromising with the EU on issues that were highly contentious among their constituents. According to our hypothesis 1, the V4 governments would therefore look for an alternative issue area to cooperate in order to regain good standing, while simultaneously targeting the specific actors they have fallen out with (hypothesis 2). Development policy ‘has often been portrayed as a technocratic, low-salience’ issue area (Hackenesch, Bergmann, and Orbie Citation2021, 4). Indeed, in the particular case of the EU, the nexus between migration and development policy in the EUTF Africa, entailed a depoliticization of EU external migration policy (Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2022). It is difficult to prove lack of politicisation, i.e. the inexistence of public discussions. However, online searches (conducted in all four V4 languages) did not identify any discussions on the EUTF Africa in the V4 countries. The lack of discussion on the topic is surprising, given the large amount of funds allocated. Important stakeholders in development aid could potentially bring the issue of migration-related development policies forth for discussion at the domestic arena. In the case of the V4, relevant NGOs expressed unwillingness to critique the V4’s spending on the EUTF Africa, afraid it might jeopardize their relationship with the V4 government which were their main donors (Interview 5).

While it is hard to prove the absence of a public discussion or debate, we did not find any evidence for the V4’s contribution to the EUTF Africa being publicly discussed within their constituencies. This suggests that the issue had low salience in these countries. While the issue of refugee quotas was very salient among the V4’s publics (Gruszczak Citation2021), the link with development in the EUTF Africa allowed for a depoliticization of external migration policies, thus making it almost a non-topic for the V4’s publics. Our interviews were not surprised that we could not find traces of V4 donations to the EUTF Africa in the news as this is something the government would probably like to keep hidden, as it would be unpopular to spend so much money on an EU fund (Interview 5 and Interview 6). Another interviewee put it this way ‘Why not anything in Polish media [on EUTF Africa donations]? Because there never is anything about EU development funding in Polish media. This is something nobody cares about. It is very un-politicized issue in Poland.’ (Interview 3). The V4 funding to the EUTF Africa was so large that in Slovakia it entailed an increase of the annual ODA budget (Interview 5). Even still, it was never broadcasted by the government or the NGOs (Interview 5).

To conclude, we find support for hypothesis 1. The V4 decided to contribute in the external dimension to counteract reputational losses accrued by refusing to cooperate on internal dimension of EU migration policy, and that they defined externalisation as the relevant approach because this was an issue-area that entailed little attention, and little controversy among constituents.

Conclusion

Our analysis suggests that even populist governments care about their international standing and want to regain good relations in the EU so much so that they employ strategies to achieve this. We find evidence that supports our expectation that the populist governments of the V4 contributed to the EUTF Africa specifically, and the external dimension of EU migration policy in general, to mend their reputation within the EU which had suffered from their persistent blocking of solidarity measures in the internal dimension of EU migration policy. While the V4 were clearly responsive to their constituencies when opposing EU internal measures on EU migration policies, especially regarding refugee distribution (Vaagland and Chmiel Citation2023), they were also responsible in that they did not entirely neglect their relationship with other EU member states, but they were well aware that they needed the EU and could not jeopardize this cooperation regime over their opposition to refugee redistribution. While refugee redistribution was a ‘no-go’ for their constituents, we find that external migration policies and especially development-migration policies that would address the ‘root causes of migration’ were likely rather uncontested and not salient among the V4’s publics. Hence, their governments could use these policies to be responsible and signal ‘good will’ to their European partners by making contributions in EU development-migration that were unusually high for them.

In our analysis, we have found evidence for all our three hypotheses: As internal EU migration policies were too controversial and too salient among their publics, the V4 invested in EU cooperation in issue areas that were not politicised domestically at all, (H1) namely development policies and border management. Their investments overlapped specifically with the interests of the actors they were in bad standing with, such as Italy and the European Commission, which suggests that they used the EUTF Africa to make up for their previous reputation losses in the context of refugee relocation (H2). Finally, the V4 engaged in a reframing campaign to shift the focus of EU migration policies towards the external dimension (H3). To lend further credibility to their commitments in the external dimension, they provided substantial funding in this dimension.

While it is certainly not a requirement for the V4’s strategy to improve their reputation that the member states and the European institutions accept their moves and hold the V4 in a better regard, it is still relevant to consider if the V4 were successful. Our answer is that they were, at least in parts. Regarding the contrition strategy which targeted the European Commission and specific Member States, it is difficult to know how these actors truly perceive the V4’s efforts, except for media reports suggesting that the European Commission president did, indeed, signal gratitude (Euroactiv Citation2017). However, regarding their re-framing strategy, we can certainly conclude that the V4 have indeed been very successful. The concept of ‘flexible solidarity’ coined by the V4 had significant impact on the development of EU migration policy (Vara Citation2022). In the substantial reform of European migration policy known as the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, the external dimension has been underlined as a very important feature (European Parliament Citation2021). Furthermore, any form of quota-based relocation seems to have been abandoned in the latest drafts (ECRE Citation2022). The V4’s argument that relocation created ‘a division in Europe’ was early on adopted by European Council President Donald Tusk (The Guardian Citation2017). Their undivided support for the ‘root causes’ frame contributed to its success in the EUTF Africa (Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2022), especially after they had challenged both the solidarity frame of the border countries and the responsibility frame of the traditional refugee receiving countries in North-Western Europe.

In fact, it is quite striking that the V4 have been able to push their alternative frame of externalisation so prominently in EU migration policy since 2015 that one could say that this is the essence of all post-2015 migration policy. Indeed, all the EU’s main ‘achievements’ in this area since the migration management crisis have been made in the external dimension of EU migration policies. These include, the EUTF Africa, the strengthening of Frontex and bilateral deals such as the EU-Turkey Statement (Niemann and Zaun Citation2023). While the EU has certainly de facto always tried to curb migration to its shores, it also tended to have a component that was much more human rights and standards focused (Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Kaunert and Léonard Citation2012; Thielemann and Zaun Citation2018). This component seems to have entirely disappeared and liberalizations of migration policies no longer figure as an important feature of EU migration policies. We would suggest that this is another indication for the framing and negotiation success of the V4: As they blocked all other policies, including those on refugee redistribution, they significantly contributed to this externalisation trend, as externalisation remained as the only viable option that was left for member states.

Perhaps, this paper can be the start of a new line of research on the importance of good standing in EU politics. Such an agenda could seek to describe the scope of such strategies, and to answer, when, if ever, reputations are too damaged to engage in reputation mending strategies. Hungary stands out as a potential case to test the latter. Having obstructed EU efforts for Ukraine, and with its ongoing Rule of Law Crisis, Hungary has severely damaged its reputation among EU Member States and in several policy areas, perhaps beyond the point of repair. As the member state where democratic backsliding has gone furthest, Hungary might indeed be a case of a country which decreasingly cares about how it is perceived by other (democratic) states, in line with the quote by Busch ‘Once your worldly reputation is in tatters, the opinion of others hardly matters.’

Ethical declaration

The project and the data collection has been approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT). All participants in this study have provided informed, written consent.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincerest gratitude to Daniela Movileanu who assisted us with the media searches in Italian. We also thank Jon Hovi for his excellent advice, and the reviewers for their thorough consideration and recommendations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karin Vaagland

Karin Vaagland is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Geneva, she conducted this research as a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo, and at Fafo research institute.

Natascha Zaun

Natascha Zaun is a Professor in Public Policy at Leuphana University Lüneburg.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2014. “Stigma Management in International Relations: Transgressive Identities, Norms, and Order in International Society.” International Organization 68 (1): 143–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000337.

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2016. “Towards a Practice Turn in EU Studies: The Everyday of European Integration.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (1): 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12329.

- Ansa. 2017, July 21. “Italy Takes No Lessons, Says Gentiloni after Visegrad ‘Close ports’ Call on Migrants.” https://www.ansa.it/english/news/2017/07/21/italy-takes-no-lessons-gentiloni-after-close-ports-call_83940215-1881-4047-9b84-c1f038ccb9c4.html.

- Astrov, V., and M. Holzner. 2021. “The Visegrád Countries: Coronavirus Pandemic, EU Transfers, and Their Impact on Austria.” wiiw Policy Notes 43, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Wiener Institut für Internationale Wirtschaftsvergleiche.

- Biermann, F., N. Guérin, S. Jagdhuber, B. Rittberger, and M. Weiss. 2018. “Political (Non-) Reform in the Euro Crisis and the Refugee Crisis: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Explanation.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (2): 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1408670.

- Bøås, M. 2021. “EU Migration Management in the Sahel: Unintended Consequences on the Ground in Niger?” Third World Quarterly 42 (1): 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1784002.

- Chmiel, O. 2018. “The Engagement of Visegrad Countries in EU-Africa Relations.” German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 24.

- Court of Justice of the European Union. 2017. “Press Release No 91/17 Luxembourg, 6 September 2017 Judgement in Joined Cases C-643/15 and C-647/15 Slovakia and Hungary V Council 16.”

- Court of Justice of the European Union. 2020. “Press Release No 40/20 Luxembourg, 2 April 2020 Judgment in Joined Cases C-715/17, C-718/17 and C-719/17 Commission V Poland.” Hungary and the Czech Republic.

- Daviter, F. 2007. “Policy Framing in the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 14 (4): 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701314474.

- ECRE (European Council on Refugees and Exiles). 2022, June 24. “ECRE Editorial: End Game of French Presidency – Passing on a Partial Reform.” https://ecre.org/ecre-editorial-end-game-of-french-presidency-passing-on-a-partial-reform/.

- Euractiv. 2018, July 23 “Visegrad Nations United Against Mandatory Relocation Quotas.” https://www.euractiv.com/section/justice-home-affairs/news/visegrad-nations-united-against-mandatory-relocation-quotas/.

- Euroactiv. 2017, December 15. “Money can’t Buy You Friends.” https://www.euractiv.com/section/justice-home-affairs/news/the-brief-money-cant-buy-you-friends/.

- European Commission. 2015, May 13. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.” https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-09/communication_on_the_european_agenda_on_migration_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2016. “EUTF Annual Report.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/default/files/eutf_2016_annual_report_final_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2017, June 14. “Relocation: Commission Launches Infringement Procedures Against the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland.” Press Statement. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/DA/IP_17_1607.

- European Commission. 2020. “Annual Report 2020 EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.” Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2841/494128.

- European Commission. 2021. “EUTF Annual Report.” https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/default/files/eutf-report_2020_eng_final.pdf.

- European Council. 2015a, September 22. “Council Decision 2015/1601.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015D1601&from.

- European Council. 2015b, April 23. “Special Meeting of the European Council, 23 April 2015 – Statement.” Press Release. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/04/23/special-euco-statement/.

- European Parliament. 2021, April 7. “The External Dimension of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum: A Focus on Prevention and Readmission.” Briefing. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)690535.

- Eurostat. 2016, March 4. “Record Number of Over 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2015.” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6.

- Eurostat. 2022. “Asylum Applicants by Type of Applicant, Citizenship, Age and Sex - Annual Aggregated Data Online Data Code.” Accessed March 5, 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYAPPCTZA__custom_2591430/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=b763d021-c2c0-462a-b678-8664e425e34d.

- Fomina, J., and J. Kucharczyk. 2016. “The Specter Haunting Europe: Populism and Protest in Poland.” Journal of Democracy 27 (4): 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0062.

- Frontex. 2016. “Annual Information on the Commitments of the Member States to the European Border Guard Teams and the Technical Equipment Pool.”

- Frontex. 2024. “Migratory Routes.” Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.frontex.europa.eu/what-we-do/monitoring-and-risk-analysis/migratory-routes/migratory-routes/.

- Garai, N. 2018. “Challenges Faced by the Visegrad Group in the “European Dimension” of Cooperation.” International Issues & Slovak Foreign Policy Affairs 27 (1–2): 4–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26592067.

- Gerring, J. 2007. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gruszczak, A. 2021. ““Refugees” as a Misnomer: The Parochial Politics and Official Discourse of the Visegrad Four.” Politics & Governance 9 (4): 174–184. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i4.4411.

- The Guardian. 2017, December 11. “EU Could ‘Scrap Refugee Quota scheme’.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/11/eu-may-scrap-refugee-quota-scheme-donald-tusk.

- Hackenesch, C., J. Bergmann, and J. Orbie. 2021. “Development Policy Under Fire? The Politicization of European External Relations.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13145.

- Helbling, M., and D. Kalkum. 2018. “Migration Policy Trends in OECD Countries.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (12): 1779–1797. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1361466.

- Il Sole 24 ore. 2017a, December 15. “Il summit di Bruxelles. Dai Paesi di Visegrad 35 milioni di aiuti da utilizzare per la Libia.” Print edition.

- Il Sole 24 ore. 2017b, December 14. “Redistribuzione dei profughi, Gentiloni: con i paesi del blocco Visegrad ancora distanze.” https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/redistribuzione-profughi-gentiloni-i-paesi-blocco-visegrad-ancora-distanze-AEsXzCSD?refresh_ce=1.

- Joint statement. 2015a, December 3. “Joint Statement of the Visegrád Group Countries.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2015b, December 17. “Joint Statement of the Visegrád Group Countries.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2015c, November 12. “Joint Statement of the Visegrád Group Countries La Valletta.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2015d, June 19. “Statement of the Heads of Government of the Visegrad Group Countries.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2015e, November 11. “V4 Ministers in Joint Article: We Offer You Our Helping Hand on the EU Path.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2016, February 15. “Joint Statement on Migration.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/calendar/2016/joint-statement-of-the.

- Joint statement. 2017b, July 19. “Joint Statement by the Prime Ministers of V4 Countries on Migration.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2017c, July 19. “V4 Joint Letter to the Prime Ministers of Italy.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint statement. 2018, June 26. “Joint Declaration of Ministers of Interior.” https://www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/official-statements.

- Joint Statement of the Heads of Governments of the V4 Countries. 2016. https://www.visegradgroup.eu/calendar/2016/joint-statement-of-the-160919.

- Kaunert, C., and S. Léonard. 2012. “The Development of the EU Asylum Policy: Venue-Shopping in Perspective.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (9): 1396–1413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.677191.

- Keohane. 1997. “International Institutions: Can Interdependence Work?” Foreign Policy 110 (110): 82–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1149278.

- Koß, M., and A. Séville. 2020. “Politicized Transnationalism: The Visegrád Countries in the Refugee Crisis.” Politics & Governance 8 (1): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i1.2419.

- Köves, M. 2018. In Phantom Menace: The Politics and Policies of Migration in Central Europe, edited by J. Kucharczyk and J. Mesežnikov, 243–262.

- Kydd, A. 2015. International Relations Theory: The Game Theoretic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lefkofridi, Z., and R. Nesi. 2020. “Responsibility versus Responsiveness … to Whom? A Theory of Party Behavior.” Party Politics 26 (3): 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819866076.

- Lewis, J. 2010. “Strategic Bargaining, Norms, and Deliberation.” In Unveiling the Council of the European Union, edited by D. Naurin and H. Wallace, 165–184. Basingstoke: Games Governments Play in Brussels.

- MAC (Migration Analytical Centre). 2018. Migration Trends in the Visegrad Group. Report. Migracyjne Centrum Analityczne. https://www.gov.pl/attachment/50e18e76-ae9c-4849-8f1b-d8bb80f0373e.

- Mair’s. 2009. “Representative versus Responsible Government.” MpifG Working Paper No. 9/8. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2017. “What is Populism?” In Populism: A Very Short Introduction, edited by C. Mudde and C. R. Kaltwasser, 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Niemann, A., and N. Zaun. 2023. “Introduction: EU External Migration Policy and EU Migration Governance.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 49 (12): 2965–2985. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2193710.

- Novak, S., O. Rozenberg, and S. Bendjabballah. 2020. “Enduring Consensus: Why the EU Legislative Process Stays the Same.” Journal of European Integration 43 (4): 475–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1800679.

- Nye, J. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2024. “Net ODA Statistics.”. Accessed March 5, 2024. https: //data.Oecd.org/oda/net-Oda.Htm

- Öniş, Z., and M. Kutlay. 2020. “The Global Political Economy of Right-Wing Populism: Deconstructing the Paradox.” The International Spectator 55 (2): 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2020.1731168.

- Pacciardi, A., and J. Berndtsson. 2022. “EU Border Externalisation and Security Outsourcing: Exploring the Migration Industry in Libya.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (17): 4010–4028. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2061930.

- Rein, M., and D. Schön. 1996. “Frame-Critical Policy Analysis and Frame-Reflective Policy Practice.” Knowledge and Policy 9 (1): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02832235.

- Rhinard, M. 2017. “Strategic Framing and the European Commission.” In The Routledge Handbook of European Public Policy, edited by N. Zahariadis and L. Buonanno, 308–322. London: Routledge.

- Scharpf, F. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic?. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Signorino, C. S. 1996. “Simulating International Cooperation Under Uncertainty. The Effects of Symmetric and Asymmetric Noise.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 40 (1): 152–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002796040001008.

- Spijkerboer, T. 2021. “Migration Management Clientelism: Europe’s Migration Funds as a Global Political Project.” Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, online first. 48 (12): 2892–2907. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1972567.

- Thielemann, E., and N. Zaun. 2018. “Escaping Populism–Safeguarding Minority Rights: Non‐Majoritarian Dynamics in European Policy‐Making.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (4): 906–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12689.

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2015, December 8. “The Year of Europe’s Refugee Crisis.” https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2015/12/56ec1ebde/2015-year-europes-refugee-crisis.html.

- Vaagland, K., and O. Chmiel. 2023. “Parochialism and Non-Co-Operation: The Case of Poland’s Opposition to EU Migration Policy.” Journal of Common Market Studies, Online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13544.

- Vara, J. S. 2022. “Flexible Solidarity in the New Pact on Migration and Asylum: A New Form of Differentiated Integration?” European Papers 7 (3): 1243–1263. https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/613.

- Verzichelli, L. 2020. “Back to a Responsible Responsiveness? The Crisis and Challenges Facing European Political Elites: The 2017 Peter Mair Lecture.” Irish Political Studies 35 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2019.1677393.

- Waltz, K. N. 1979. Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Zaun, N. 2018. “States as Gatekeepers in EU Asylum Politics: Explaining the Non‐Adoption of a Refugee Quota System.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12663.

- Zaun, N. 2022. “Fence-Sitters No More: Southern and Central Eastern European Member States’ Role in the Deadlock of the CEAS Reform.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (2): 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1837918.

- Zaun, N., and O. Nantermoz. 2022. “The use of Pseudo-Causal Narratives in EU Policies: The Case of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (4): 510–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881583.

- Zaun, N., and A. Ripoll Servent. 2022. “Perpetuating Crisis as a Supply Strategy: The Role of (Nativist) Populist Governments in EU Policymaking on Refugee Distribution.” Journal of Common Market Studies, 61 (3): 653–672. online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13416.

- Zürn, M. 2014. “The Politicization of World Politics and its Effects: Eight Propositions.” European Political Science Review 6 (1): 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773912000276.