Abstract

This article examines the main trends in Canadian aid policies from the 2006 election of the Conservatives under Stephen Harper to their defeat in 2015. It finds that the Harper government increasingly instrumentalized Canadian foreign aid, reorienting it to benefit Canadian interests, to the detriment of poverty reduction abroad. This was part of a broader foreign policy that sabotaged Canada’s ability to use its soft power to influence the global order.

Introduction

The Conservative government of Stephen Harper (2006–2015) increasingly instrumentalized Canadian foreign aid. This was not a new phenomenon—successive Canadian governments always used official development assistance (ODA) for self-interested reasons—nor was it unique to Canada. However, the Harper government, in initiative after initiative, consistently reoriented aid to benefit Canadian interests, to the detriment of poverty reduction abroad, which is its legally mandated central purpose. The two goals are not necessarily incompatible because Canada would benefit from a stable, prosperous world, but the Harper government did not adopt such a long-term perspective. Quite the opposite, it embraced an often very limited view of Canadian interests, including those of Canadian private sector companies. Such an approach not only harmed poverty-reduction efforts, but also was part of a broader foreign policy that sabotaged Canada’s ability to use its soft power to influence the global order—another component of national self-interest.

This article examines the main trends in Canadian aid policies from the 2006 election of the Harper Conservatives to their defeat in 2015, examining in turn the four main components of the instrumentalization: first, the securitization of aid, whereby it was heavily influenced by security considerations, rather than poverty reduction, often under what was called the “whole-of-government approach”; second, the increased alignment with Canadian foreign policy by focusing aid on specific countries and instrumentalizing nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); third, the commercialization of foreign aid; and, fourth, policy coherence and institutional changes, notably the abolition of the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The article then turns to some important counterevidence regarding aid budgets, the untying of aid, and assistance to the poorest countries and vulnerable populations. A final section summarizes the findings and places them within global trends.

Readers should keep in mind that I am assessing trends, that is to say changes. I argue that instrumentalization increased significantly under the Harper government, but not that it was new or that all, or even most, aid was instrumentalized. Billions of dollars in Canadian aid continued to be spent quite altruistically, making important development contributions around the world. Dedicated staff at CIDA—which became part of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) in 2013, which was then renamed Global Affairs Canada (GAC) after the Liberals were elected in 2015—continued to labour tirelessly to help fight poverty and inequality, despite strong pressure from the highest levels to subordinate aid to narrowly defined self-interest.1

The securitization of aid

The first strong foreign aid trend to emerge under the Harper government was its securitization, notably in the central place of Afghanistan as a prime recipient of Canadian ODA, linked to the presence of Canadian troops in Kandahar, where Canada assumed responsibility for the Provincial Reconstruction Team in 2005. During the 2005–2006 fiscal year, the Liberals’ last year in power, Canada disbursed $101 million in aid to Afghanistan. The following year, Canada spent $229 million, rising to $345 million in 2007–2008, at which point aid to Afghanistan constituted eight percent of Canada’s total aid budget.2

Afghanistan’s position at the top of Canada’s list of aid recipients pointed towards two dimensions of the broader phenomenon of the securitization of aid: the choice of recipients and aid modalities. First, the prioritization of Afghanistan—and other countries, such as Iraq and Sudan—reflected Western countries’ preoccupation with “failed and fragile states,” a central concern inherited from the foreign policy of the previous Liberal government of Paul Martin. From this perspective, such countries constituted a “problem” for Canada and its allies because of their instability and their hosting of criminal and even terrorist organizations. When a country adopts this view, aid becomes more self-interested because poverty is not perceived as a scourge to be eliminated for moral or even economic reasons, but rather a threat to donors’ own security.

Second, the modalities of aid delivery in Afghanistan and especially Kandahar, where half of Canadian aid to that country was to be directed, were securitized. Whereas, initially, Canadian aid was closely aligned with the priorities of the Afghan government and delivered in close cooperation with multilateral actors, in Kandahar after 2007 aid often responded to the priorities of the Canadian Forces, articulated by the Canadian government and imposed on the various components of Canadian foreign policy. This was justified by invoking a whole-of-government approach, which promoted policy coherence to achieve synergies among the various official Canadian actors, including the military, diplomats, and CIDA officials. In practice, this approach aligned Canadian aid with Canadian security interests. A significant amount of aid was spent on projects aimed at winning local hearts and minds, in other words, to garner support for the presence of Canadian troops. For instance, aid was used to try to win villagers’ support by building them a school or a clinic, theoretically making them less likely to support the Taliban.

This logic, however, had several fundamental flaws. It underestimated the complexity of the situation on the ground and the reasons why Kandaharis might not want to ally themselves with Canadian Forces whose presence in their village was only temporary. It also overestimated the ability of gifts to change people’s attitudes towards a foreign occupation of their territory and to alter their views of their own interests, as well as miscalculated how beneficial having a new building in a village would be without the provision of necessary equipment or personnel, especially if the security situation made using the building dangerous. Moreover, cooperation between Canadian civilian and military personnel proved difficult, notably because of significant differences in institutional cultures, timeframes, and priorities. Because about 90 percent of the Provincial Reconstruction Team’s personnel and budget came from the Department of National Defence, the latter was able to impose its perspective on Foreign Affairs and CIDA. In sum, the whole-of-government approach in Afghanistan was dominated by a security viewpoint, to the detriment of development, and the strategy was relatively inefficient on both counts. In 2011, Canada transferred responsibility for the Kandahar Provincial Reconstruction Team to the United States and withdrew its combat troops from Afghanistan. Relatedly, it significantly reduced its foreign aid to the country.

The Harper government’s focus on stand-alone programming, rather than close integration with the Afghan government and other donors, was further illustrated by its 2008 decision to establish three branded “signature projects,” which contradicted the lessons of more than a half-century of foreign aid. Consequently, results proved disappointing. The government’s own evaluation of its development program in Afghanistan concluded that the rehabilitation of the Dahla Dam and irrigation canals in Kandahar—the most prominent signature project—achieved the “most outputs…but there is no evidence that the system is being effectively operated, which may lead to a rapid deterioration if no follow-up is provided.”3 The government also recognized that another Canadian signature project had failed—the elimination of polio.4 In fact, the report concluded more generally that “Counter-insurgency and stabilization approaches failed to address long-term development requirements” and that “implementation of the development Program [sic] in Kandahar showed that long-term development cannot be accomplished with an emphasis on short-term implementation strategies, which sped up project delivery considerably, but failed to ensure sustainable, long-term development results in more than a few areas.” Neither of these conclusions will surprise anyone with a modicum of knowledge about aid effectiveness.5

To be sure, the experience in Afghanistan is not typical of CIDA programming. In other places where the Canadian government has adopted a whole-of-government approach, especially in Haiti and South Sudan, the experience has been less dominated by security actors and interests.6 Afghanistan, because of its prominent place in Canadian foreign policy at the time, illustrates well the securitization trend, which has nonetheless waned since the withdrawal of Canadian troops.

New priorities and partnerships

Starting in 2009, the Harper government adopted a more proactive foreign policy, which was reflected in the aid program. In that year, Minister for International Cooperation Bev Oda announced new lists of priority countries and themes, substituting for the ones adopted in 2005 under the Martin government. The government dropped several poor African countries and replaced them with ones in Latin America and the Caribbean, most of which are middle-income countries and many of which have important trade linkages with Canada. This marked the beginning of the recommercialization of Canadian aid.

The minister also replaced the priority sectors for aid—which were governance, health, basic education, private sector development, and environmental sustainability—with three “themes”—food security, the future of children and youth, and sustainable economic development. These themes were broader than the “sectors” that they replaced. Almost immediately, one could observe an important increase in CIDA programming under the first two themes. The third theme was the vaguest and had the least clear short-term impact, but it played an important role in subsequent years.

In 2010, CIDA announced the “modernization” of its mechanisms for funding development NGOs. Previously, Canada had been a world leader in the way it provided grants to NGOs—the process was often based on long-term, trust-based relationships, and was buttressed by periodic evaluations of the organizations’ programs.7 In the 1990s, however, the Canadian government began to increase its control over the NGOs’ activities.8 As of 2010, NGOs seeking CIDA grants could no longer submit projects that they developed with their partners in the Global South, in line with their expertise and priorities. Instead, the NGOs had to wait for a call for proposals and respond to Canadian government geographic and sectoral priorities, reflecting a subcontracting mindset.9 Not only did this place NGOs in direct competition with one another, but no general calls for proposals were issued after 2011. These years of unpredictability and the drying up of funding hurt planning, imperilled NGOs’ relations with their Southern partners, and even brought several NGOs to the edge of bankruptcy.

The devaluing of civil society and the role of NGOs as development actors in their own right was amplified by the growing politicization of NGO funding. Several organizations that criticized Canadian aid policies, especially those relating to the Middle East or the extractive sector—such as Alternatives, the Canadian Council for International Co-operation, KAIROS, and the Mennonite Central Committee—did not have their funding renewed or else saw it cut substantially. In parallel, critical development and environmental NGOs were subjected to crippling in-depth audits by the Canada Revenue Agency, which put their tax-exempt status at risk.

In early 2015, Minister of International Development Christian Paradis announced a new Civil Society Partnership Policy that promised to reverse some heavily criticized policies and practices. Although it has the potential to vastly improve the government’s often fraught relationship with the NGO sector, no tangible impact could be discerned in the remaining time that the Harper government was in power. No new general call for proposals was announced and the tax audits continued unabated, while the minister continued to focus his public statements on the role of the private sector, rather than civil society, in development. The private sector and development had been a prominent theme since the early 2010s, while Oda was Minister for International Cooperation. During that period, CIDA set up a special fund for NGO projects that included the participation of a Canadian mining company. The promotion of the extractive industry’s involvement in development is examined in greater detail below because the role of the private sector merits its own section.

Finally, it is worth underlining that the government justified most of these new initiatives by alleging their greater effectiveness, even though—with the exception of eliminating tied aid—none of them had a clear positive impact of effectiveness and several had a negative one. Moreover, the very act of frequently changing policies and priority countries and themes contributes to volatility and unpredictability, which, in turn, reduce aid effectiveness.10

The Canadian private sector and Canadian aid

Even before CIDA was created in 1968, Canadian aid was linked to Canadian commercial interests through the choice of recipient countries, the type of assistance provided, and the “tying” of the majority of aid to the purchase of goods and services in Canada, which meant that billions of aid dollars never left the country. In 1978, CIDA established an Industrial Cooperation Program, aptly known as CIDA-INC, which sought to support the involvement of the Canadian private sector in development. From its founding until 2005, the program spent more than $1 billion, but the results were disappointing. According to an internal CIDA evaluation, only 15.5% of the projects supported between 1997 and 2002 were “considered successful.”11 In 2009, the government transferred the program to the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, suspending it in 2012 following a police investigation into financial irregularities.12 That same year, an official evaluation made a single recommendation: that the department “not restart the INC Program in its current form.”13

CIDA priority areas announced in 2002 and 2005 by Liberal governments included the private sector. However, it was not explicitly on the Conservatives’ 2009 list, but subsumed under the “sustainable economic growth” theme. Although the Harper government “untied” aid (as explained below in the counterevidence section), it simultaneously reintroduced commercial interests through the back door by emphasizing the involvement of the Canadian private sector in development. In justifying the importance of the private sector, the government conflated Canadian companies with those based in developing countries—the importance of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the Global South was invoked to justify the use of ODA to support multinational corporations based in Canada. For instance, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development held hearings on the role of the private sector in development. Many witnesses testified to the importance of the local private sector, whereas the committee’s report, adopted in 2012, recommended, among other things, that CIDA funds be set aside for cooperation with the Canadian private sector, and made no mention of its previous disastrous efforts through CIDA-INC.14 Simultaneously, other government development initiatives sought to support Canadian companies, especially in the extractive sector.15

It is in that context that CIDA announced three new projects in 2011, cofunded by three Canadian mining companies and implemented by Canadian NGOs: one in Peru (Barrick Gold and World Vision Canada), another in Burkina Faso (IAMGOLD and Plan Canada), and the third one in Ghana (Rio Tinto Alcan and World University Service of Canada). CIDA allocated $6.7 million to these projects, in addition to $20 million for an Andean Regional Initiative for Promoting Effective Corporate Social Responsibility.16

These programs mostly benefitted communities affected by Canadian mining activities, acting as an incentive to allow Canadian companies to open and operate mines in their lands. The programs thus constituted an indirect subsidy to the Canadian private sector in the name of development. Despite government statements on the innovative nature of those partnerships, the projects followed the traditional NGO aid model. Although the Canadian companies provided some funding, they did not contribute any expertise or knowledge specific to the private sector. This is not surprising because—in the words of Pierre Gratton, the president of the Mining Association of Canada, which represents the industry—“We’re miners, we’re not in the business of social and community development that the NGOs are experts at.”17 Journalist Marco Oved of The Toronto Star visited all three project sites and found lacklustre results.18 Although Paradis recognized that the projects had some weaknesses, he signalled that this type of funding would be expanded.19

These projects did not seek to improve the practices of the Canadian extractive sector, which is often associated with human rights abuse and environmental degradation, among other problems.20 Canadian mining companies are by far the worst in the world on those counts, according to an unpublished study by the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada.21 In fact, two of the three companies involved in the CIDA partnerships—Rio Tinto and Barrick Gold—are on a Swiss organization’s list of the 10 mining companies with the worst reputations in the world.22 In addition, an American NGO has placed Barrick Gold on its list of the world’s top ten “corporate criminals” (regardless of sector) because of the environmental damage it has caused.23

These Canadian companies’ charitable endeavours, funded by the Canadian aid program, are side activities that can distract public attention from the issue of accountability for their actions. Moreover, CIDA provided funding to at least one NGO that was created by extractive companies themselves: it granted $4.5 million in 2011 to the Lundin Foundation (then called Lundin for Africa), set up by the Lundin Group of Companies, followed by another $2.8 million in 2012 for a joint program with the NGO Engineers without Borders.24

One can observe a concerted effort by successive ministers responsible for Canadian aid—who sometimes appear to be ministers of industry or trade—to rehabilitate the reputation of Canadian companies and promote their interests. For instance, Oda declared in April 2012 that “There’s nothing wrong with the private sector, and particularly our Canadian private sector. They’re responsible. They’re good.”25 Soon afterwards, a major scandal erupted at SNC-Lavalin, an important CIDA partner, and it was then barred from obtaining contracts with CIDA and the World Bank for a 10-year period. A review of Canada’s aid program, carried out by other donor countries and published in June 2012, reminded the Canadian government that “there should be no confusion between development objectives and the promotion of commercial interests.”26 Nonetheless, Oda’s successor, Julian Fantino, repeated in November 2012 that “Canadian companies have shown themselves to be socially responsible,” while emphasizing corporate financial interests: “And most importantly: This has contributed to your bottom line.”27 He raised the ante on private Canadian interests the following month, asserting in an interview not only that “We have a duty and a responsibility to ensure that Canadian interests are promoted,” but also that “Canadians are entitled to derive a benefit” from Canadian foreign aid.28 His successor, Christian Paradis, continued to place great emphasis upon the private sector.29

Policy coherence and the abolition of CIDA

In 2013, when the Harper government abolished CIDA and transferred its functions to the newly renamed DFATD, it did so mainly in the name of policy coherence.30 The government claimed it wanted to improve coordination among the various components of foreign policy, thereby increasing its effectiveness—an announcement that could potentially be good news for poor people around the world. In fact, soon after the decision was announced, Minister of International Cooperation Fantino stated that one of the central goals of the merger was “to put development on equal footing with trade and diplomacy.”31 One supporter of the merger, Scott Gilmore, stated that it “means that those trade commissioners are now going to understand how to make their trade deals more pro-poor, and how they can use tariff reductions, for example, in sub-Saharan Africa as a major catalyst for agricultural growth.”32 However, there are strong reasons to believe that the absorption of CIDA into DFATD, in the name of policy coherence, actually further marginalized development issues.

Even before DFATD swallowed up CIDA, the latter was having trouble defending its poverty-reduction mandate. As mentioned earlier, Fantino himself repeatedly emphasized the “need” for Canadians to benefit from Canadian foreign aid. In a heavily redacted version of a March 2013 internal review of CIDA programming obtained by The Globe and Mail, the “bottom line” for each country (when not completely blanked out) usually invoked Canadian commercial interests to justify current or increased aid levels, and made no reference to development needs or poverty reduction.33 Critics of CIDA’s absorption into DFATD worried that the new institutional arrangement would further reduce Canada’s commitment to development issues.

If one is to judge by the Global Markets Action Plan, DFATD’s only policy paper released after the merger, the development perspective is far from being “on an equal footing with trade and diplomacy,” and, in fact, has no influence on other components of foreign policy. Published in November 2013, the plan presents “economic diplomacy” as the Canadian government’s overarching foreign policy goal and promises to “ensure that all Government of Canada diplomatic assets are harnessed to support the pursuit of commercial success by Canadian companies and investors.”34 It contains no mention of any benefit for poor people or developing countries. It refers to Canadian foreign aid only once, expressing the desire to “leverage development programming to advance Canada’s trade interests.”35 That is not to say that Canadian trade cannot sometimes benefit the Global South as well. Not once, however, is that case made, nor is it ever suggested that such concerns played any part in developing this plan. Despite Gilmore’s optimism, there is no mention that trade deals, tariff reductions, or any such policies will help reduce poverty abroad.

Perhaps in response to this important lacuna, Minister of International Development Christian Paradis—who was appointed soon after CIDA’s abolition—made a speech in December 2013 entitled “Development as an Integral Part of Canadian Foreign and Trade Policy.” Like Fantino before him, even he, whose primary remit was international development, emphasized how the plan and the various components of foreign policy “[contribute] to Canada’s prosperity.” He did include a throwaway sentence on how, “[by] stimulating the economy in these countries and helping them create an environment conducive to investment, we are contributing to the well-being of people living in poverty.”36 However, such short, rare, facile, and eminently debatable statements hardly suggest that poverty reduction was a motivator, especially when his speech and the plan itself both focused almost exclusively on benefits to Canadian companies and investors.

Policy coherence within the new DFATD, as was the case under the whole-of-government approach in Kandahar, was thus more likely to detract from development than to promote it, at least under the Harper government—an argument made recently in this journal by Michael Bueckert as well.37

Counterevidence

Some evidence can be marshalled against my claims of the growing instrumentalization of Canadian aid. In this section, I assess the possible counterevidence related to increased aid spending, as well as a greater emphasis on poverty, poor countries, and vulnerable populations within existing aid programs.

Aid spending

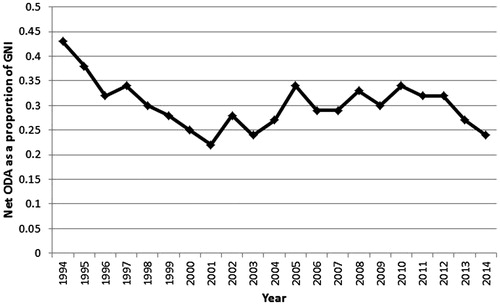

The relative generosity of Canada’s aid program has varied greatly over the years. ODA as a proportion of gross national income (GNI) increased from 0.1% in 1962 to a record high of 0.54% in 1975, albeit not especially close to the official 0.7% target. After the election of the Liberals under Jean Chrétien in 1993, it fell by half—from 0.45% to 0.22% in 2001, a level not seen since 1965. Nonetheless, in line with global trends after the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals and security concerns related to the September 11, 2001 al-Qaeda attacks, Canadian aid spending bounced back to a peak of 0.34% in 2005 and again in 2010.38

During its first few years in power, the Harper government remained steadfast to Liberal promises to increase the ODA budget on an annual basis, to double the total amount compared to that of 2001, and to double aid to Africa. It constantly repeated its commitment to these goals and emphasized its accountability for its promises and its reliability, as well as its generosity.

In 2011, however, once it had reached these targets, the government announced an aid budget freeze, followed by official cuts and an apparently deliberate policy to underspend the budget. As a result, the ODA/GNI ratio fell to 0.24% in 2014—below the OECD average of 0.29% and lower than in 2006 when the Harper Conservatives were first elected (see ). Canadian generosity under the Conservatives was thus more of a temporary performance, related mainly to accountability for prior promises, rather than an actual long-term commitment.

The untying of aid

As mentioned above, tied aid must be spent on goods and services in the donor country, rather than where best value for money can be obtained. This practice benefits the donor country, but increases the costs of aid delivery and can be considered harmful to the recipient country. Nonetheless, tied aid was a staple of many countries’ aid programs, and Canada tied a higher proportion of its aid than most of its donor peers: a minimum of half of aid to Africa and least-developed countries in other regions, two-thirds of its aid elsewhere, and 90 percent of its emergency food aid.

Recognizing that tying aid to the purchase of Canadian goods and services was more expensive and thus less effective, and having been influenced by European countries’ untying of aid, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien began to reduce the proportion of tied aid in 2002. The Harper government completed the task, fully untying food aid in 2008, followed by aid in all other sectors in 2012.39 The rationale for untying aid, however, was contradicted by the recommercialization of aid in other forms, described above.

A focus on poverty, poor countries, and vulnerable populations

During the early years of the Harper government, an opposition-supported initiative sought to reduce self-interest in Canadian aid and reorient aid towards poverty reduction in the Global South. In 2008, in the context of a minority government, Parliament adopted a private member’s bill, the Official Development Assistance Accountability Act, which defined for the first time Canadian aid’s core objective: that it be “provided with a central focus on poverty reduction.” Moreover, according to the provisions of the act, “Official development assistance may be provided only if the competent minister is of the opinion that it (a) contributes to poverty reduction; (b) takes into account the perspectives of the poor; and (c) is consistent with international human rights standards.”40

The new legislation had the potential to reduce the instrumentalization of aid, but its impact was minimal. The government declared that all of its development projects were already in line with the act, and did not seem to take it into account in its new initiatives. It would appear that the amendments adopted during the bill’s passage weakened it to the point that it could not ensure its central objective, and thus proved useless in protecting and reinforcing Canadian aid’s focus on poverty.

A common indicator of altruism is the proportion of bilateral aid that is spent in low-income countries, on the assumption that they need it the most, whereas aid to middle-income countries generally signals the prioritization of commercial ties. By this metric, the Harper government was actually less self-interested than its recent Liberal predecessors. The former spent a significantly higher proportion of its aid in low-income countries (37 percent) during its first nine years in power (2006–2014) than the Liberals did (24 percent) during their last nine (1997–2005). This increase was in line with the trend among Western donors between the same periods (increasing from 25 percent to 31 percent), but the Liberals were one percent below the average and the Conservatives six percent above it.41

Some caution should be injected into the interpretation of these aggregate figures. Under the Harper government, the proportion of aid that was not officially allocated by country income level in the aid statistics decreased from 48 percent to 41 percent compared to the proportion of aid allocated by the Liberals in their final years. This means that seven percent could have been simply recoded from “unallocated” to “low income,” without a shift in spending. Still, this amount is sufficient to account for barely half of the 13 percent increase. Thus the reallocation of aid to low-income countries under the Conservatives is significant and suggests an increase in altruism. Nonetheless, a closer examination of what the money was spent on would be required before reaching a definitive judgement. After all, more money could have been spent on, for instance, supporting Canadian mining companies in poor African countries without that constituting greater altruism.

Another observable trend under the Harper government was the increased emphasis on humanitarian assistance in public pronouncements and press releases. Aid statistics bear out this observation: during the last nine years of Liberal governments, Canada committed seven percent of its aid budget to humanitarian assistance, doubling it to 14 percent in the first nine years of Conservative rule. By way of comparison, the total amount committed by Western governments between the same two periods increased at less than half of Canada’s rate, from eight percent to 11 percent of total aid disbursements.

Emergency aid, by definition, is directed towards vulnerable populations in dire need of urgent assistance. As such, it could be taken as an indicator of altruism. These figures could indicate that the Harper government was less self-interested than the Liberals or the average Western donor, at least in its concern for people in emergency situations. But one can debate the extent to which the emphasis on humanitarian assistance actually reflects a degree of altruism. It can also be interpreted as a particular government spin on what foreign aid should be used for, namely, to help victims in short-term need, rather than reduce poverty in ways that reduce vulnerability to disasters and otherwise prevent future needs from emerging. In other words, an emphasis on victims can be at the expense of empowering poor people, enabling them to escape poverty and making them less in need of short-term assistance. This emphasis also reflects a simplistic, often Christian view of charity—sending food, water, tents, and blankets to the needy, rather than questioning the reasons for poverty and inequality, and taking action to reduce inequality and transform power structures over the long term.

A final indicator of the Conservative government’s altruism could be its emphasis on women and children. For instance, it committed $3.5 billion to the Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH), announced by Harper at the 2010 G8 Summit. Although the Conservative government was trying to assert Canada’s global leadership in this area, this leadership did not inspire much “followership.”42 This is due, in part, to a Johnny-come-lately attempt to steal the spotlight from countries that had already been active in MNCH for a longer period of time, and partly because of Canada’s refusal to use any of its funds to support abortion services, even where they were legal, and its reluctance to support contraception—both of which are important elements of women’s sexual and reproductive health. Still, the Harper government used the Muskoka Initiative to try to convince the Canadian public that it was strongly concerned about the fate of vulnerable populations. This concern was epitomized by a summit held in Toronto in May 2014 under the theme “Saving Every Woman, Every Child: Within Arm’s Reach.” As with humanitarian assistance, the Conservatives’ approach to MNCH emphasized the short-term ‘saving’ of innocent victims, rather than tackling the systemic causes of gender inequality or poor health care that are linked to underlying poverty.43 The same observation can be made of the Harper government’s official priorities for the “Post-2015 Development Agenda,” which included MNCH; child, early, and forced marriage; and child protection.44

Focusing on the most vulnerable is a laudable objective, but the prominence and framing of these issues, as well as the approach taken, were rather problematic. The focus on women and children, as with the emphasis on victims of disasters, can also be interpreted as a rather superficial performance of concern, rather than its embodiment, addressing causes rather than symptoms. The optics were aimed at domestic voters, seeking to put a kinder, gentler face on Conservatism.45 As stated by Ilan Kapoor, foreign aid is “inherently contradictory and aporetic, with both its economic and symbolic pursuits integral to donor practice.”46 He argues that the altruistic “gift” obscures the self-interested “grift.” One can make a similar point, inspired by John Cameron’s recent work, that “doing good” distracts attention from the more basic ethical imperative to “do no harm,” including that by the Canadian extractive industry.47

Conclusion

This article’s final section provides some limited evidence of Canadian altruism under the Harper government’s aid initiatives. The untying of aid stands out as the strongest case of a new aid policy that benefitted developing countries and not Canada, but this is contradicted by the other forms of support given to Canadian companies. Although it was under a Conservative government that Parliament passed a law defining the primary purpose of aid to be poverty reduction, this occurred in the context of a minority government that managed to defang the legislation to the point that it did not make a difference. Compared to the Liberal governments under Chrétien and Martin, the Conservative government under Harper did spend a higher proportion of aid in the poorest countries and on humanitarian assistance, and placed greater emphasis on women and children. Still, this cannot be taken as incontrovertible evidence of altruistic intentions because the impact on the poor depends greatly on the objectives and modalities of aid. Moreover, the old-fashioned charitable approach to aid actually reduces the likelihood of the kind of transformative change that is required to reduce, and eventually perhaps eradicate, poverty, rather than merely alleviating short-term suffering.

In other respects, this article shows how the Harper government’s various new aid initiatives demonstrate a high degree of instrumentalization of development assistance in order to pursue the government’s interests and priorities other than those of its partners in civil society or in the Global South. This is well illustrated by the securitization of aid to Afghanistan during the Harper Government’s early years in power. Starting in 2009, despite the progressive elimination of tied aid, one can observe the recommercialization of ODA, seeking increasingly to benefit Canadian companies and investors, notably in the extractive sector, in spite of poverty reduction being legally defined as the main purpose of Canadian aid. The desire to instrumentalize aid is epitomized by the folding of CIDA into DFATD, which facilitated the use of foreign aid for self-interested reasons, already visible in the Global Markets Action Plan. The Conservatives also sought to transform Canadian NGOs into apolitical subcontractors instead of independent development actors with a legitimate advocacy role. These initiatives were motivated by an ideological affinity for the private sector and electoral considerations, and sometimes by disdain for aid’s potential to transform the lives of the poor, seeking instead to alleviate poverty rather than reduce or eliminate it.48 As a result, the Conservative government increasingly subjected ODA to its whims and thus hampered aid effectiveness. Inasmuch as that harmed Canada’s reputation and reduced the country’s influence on the world stage, it also potentially sabotaged Canada’s foreign policy goals over the long term.

These trends were not entirely new; in most cases, they built on previous governments’ initiatives, notably the Liberals’. They were not unique to Canada either; promoting the private sector is currently in fashion in international development. Many Western countries are seeking to use ODA to support their security or commercial interests, including in the mining sector. This integration of aid, trade, and investment increasingly resembles the practices of China and other ‘emerging’ countries, even if these practices contradict the basic definition of ODA, namely its focus on socioeconomic development in recipient countries. Australia, soon after Canada, also placed its aid agency under its Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and cut its aid budget more drastically.49

Still, several other countries, especially European ones, are going in the opposite direction. The British government, for instance, under a Conservative-led government, not only met but also enshrined the 0.7% of GNI aid target as a legal obligation, despite having a fiscal deficit much greater than Canada’s.50 The United Kingdom also has much stronger legislation on the purpose of aid than Canada, prohibiting commercial considerations from influencing aid allocation—though British aid allocation patterns still reflect former colonial ties and security interests. In 2015, moreover, several other European countries began to divert significant amounts of their overseas aid budgets to finance the resettlement of refugees at home.51

The instrumentalization of Canadian aid was facilitated by the whole-of-government approach and policy coherence, but the latter are not necessarily obstacles to a Canadian foreign policy that could do much more to favour development in the Global South. Nothing prevents the Liberal government under Justin Trudeau, or any future government, from using those tools to help reduce poverty, but a change of government does not in itself guarantee a change in direction towards a less self-interested Canada.

Notes on contributor

Stephen Brown, teaches in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Acknowledgements

A shorter version of this article was previously published as “Le gouvernement Harper et l’aide au développement,” Nouveaux Cahiers du socialisme, no. 13 (Winter 2015): 237–45. The author is grateful to the journal for permission to expand on it here in English. He also thanks the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for funding his research, the Centre for Global Cooperation Research at the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany) for hosting him while he wrote this article, as well as Dave Thomas and Anna Zalik for their very helpful suggestions, and Thomas Collombat for his editorial guidance.

Disclosure statement

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Notes

Notes

1 On CIDA’s resistance to instrumentalization, see Bueckert, “CIDA and the Capitalist State.”

2 Canadian International Development Agency, Statistical Report on International Assistance, Fiscal Year 2005–2006, Fiscal Year 2006–2007 and Fiscal Year 2007–2008.

3 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. Synthesis Report, 29. For more information on the Dahla Dam, see Baranyi and Paducel, “Whither Development,” 113–14; Watson, “Canada’s Afghan legacy: Failure at Dahla Dam”; and Paul Watson, “Canada’s Afghan legacy: Plan for Kandahar Dam.”

4 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, Synthesis Report, 36.

5 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, Synthesis Report, 5 and 48. It is now widely accepted in development circles, among practitioners and academics, that short-term projects almost always have a limited impact. For more sustainable outcomes, sustained, broader efforts that address underlying problems are required, not bandaid solutions. For more in-depth analysis of Canada’s development endeavours in Afghanistan, see Brown, “From Ottawa to Kandahar” and Joya, “Failed States and Canada’s 3D Policy.”

6 Baranyi and Paducel, “Whither Development.”

7 Morrison, Aid and Ebb Tide, 21.

8 Brodhead and Pratt, “Paying the Piper,” 114.

9 Brown, “CIDA’s New Partnership.”

10 On the issue of aid effectiveness under the Harper government, see Brown, “Aid Effectiveness.”

11 Canadian International Development Agency, Executive Report on the Evaluation, 17.

12 Munson, Past Failure.

13 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, Evaluation of the Investment Cooperation (INC) Program.

14 House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Driving Inclusive Economic Growth.

15 Goyette, “Charity Begins at Home.”

16 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, Minister Oda announces initiatives. The Canadian government also created the Canadian International Institute for Extractive Industries and Development, housed at the University of British Columbia and later renamed the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute, to which CIDA (now subsumed into Global Affairs Canada) is contributing $25 million.

17 Quoted in Mackrael, “Ottawa signals shift.”

18 Oved, “After the gold rush”; Oved, “Ghana”; Oved, “Fool’s Gold.”

19 Mackrael, “Ottawa urges development.”

20 See, for instance, the special issue on “Canadian Mining Companies Invade the Global South,” Canadian Dimension 45, no. 1 (2011); Abadie, “Canada and the Geopolitics of Mining Interests”; Campbell, “Peace and Security in Africa”; Campbell, “Regulation & Legitimacy”; Gordon and Webber, “Imperialism and Resistance”; North et al., Community Rights and Corporate Responsibility; and Butler, Colonial Extractions, as well as the extensive research conducted by MiningWatch Canada (http://www.miningwatch.ca).

21 Cited in Whittington, “Canadian Mining Firms.”

22 RepRisk, Most Controversial Mining Companies.

23 Global Exchange, Top 10 Corporate Criminals List. See also Arnold, “Mining, CIDA partnership,” 7.

24 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, “Minister Oda Announces Canadian Partnerships”; Global Affairs Canada, International Development Project Browser. A member of this group of companies, Lundin Petroleum, has been accused of complicity with war crimes and crimes against humanity in Sudan (see Sunderland, “Oil companies accused”).

25 Cited in Shane, “Budget to be Balanced.”

26 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canada, 11.

27 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, “Minister Fantino’s Keynote Address.”

28 Quoted in Mackrael, “Fantino Defends CIDA’s Corporate Shift.”

29 For a more in-depth analysis of the use of ODA to promote Canadian commercial interests, see Blackwood and Stewart, “CIDA and the Mining Sector”; Brown, “Undermining Foreign Aid”; and Bodruzic, “Promoting International Development.”

30 This section is adapted from Brown, “When Policy Coherence.”

31 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, “Today, the Honourable Julian Fantino.”

32 Quoted in Mackrael, “Ottawa’s Elimination of CIDA.”

33 Kim Mackrael, “Commercial Motives.” See also Canadian International Development Agency, Reviewing CIDA’S Bilateral Engagement.

34 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, “Global Markets Action Plan,” 4, 6.

35 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, “Global Markets Action Plan,” 14.

36 Global Affairs Canada, “Statement by Minister Paradis.”

37 Bueckert, “CIDA and the Capitalist State.”

38 These figures provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Query Wizard.

39 Global Affairs Canada, Development Priorities. See also Brown, “Aid Effectiveness,” 471–2.

40 Official Development Assistance Accountability Act.

41 The figures from this paragraph and the following two were calculated by the author, based on data from OECD, Query Wizard, extracted December 23, 2015.

42 Black, “The Muskoka Initiative,” 243; see also Brown and Olender, “Canada’s Fraying Commitment,” 166–70.

43 For more in-depth critiques of the Muskoka Initiative and the Toronto “vanity” summit, see a series of blogs by the McLeod Group at http://www.mcleodgroup.ca/tag/maternal-health. On Canada’s MNCH Initiative more broadly, see Tiessen, “Walking Wombs.”

44 Global Affairs Canada, “Post-2015 Development Agenda.”

45 See Brown, “Canada’s Development Interventions.”

46 Ilan Kapoor, The Postcolonial Politics of Development, 90.

47 Cameron, “Revisiting the Ethical Foundations.”

48 See Audet and Navarro-Flores, “The Management of Canadian Development Assistance”; Black, “Between Indifference and Idiosyncrasy.”

49 Wroe, “AusAid Swept under Foreign Affairs Control.”

50 Anderson, “UK Passes Bill.”

51 Deen, “Development Aid.”

Bibliography

- Abadie, Delphine. “Canada and the Geopolitics of Mining Interests: A Case Study of the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Review of African Political Economy 38, no. 128 (2011): 289–302.

- Anderson, Mark. “UK Passes Bill to Honour Pledge of 0.7% Foreign Aid Target.” The Guardian. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/mar/09/uk-passes-bill-law-aid-target-percentage-income.

- Arnold, Rick. “Mining, CIDA Partnership in Peru is Pacification Program, Not Development.” Embassy, Mar. 7, 2012.

- Audet, François, and Olga Navarro-Flores. “The Management of Canadian Development Assistance: Ideology, Electoral Politics or Public Interest?” In Rethinking Canadian Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, Molly den Heyer and David R. Black, 179–192. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2014.

- Baranyi, Stephen, and Anca Paducel. “Whither Development in Canada’s Approach Toward Fragile States?” In Struggling for Effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, 108–34. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

- Black, David. “Between Indifference and Idiosyncrasy: The Conservatives and Canadian Aid to Africa.” In Struggling for Effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, 246–68. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

- Black, David R. “The Muskoka Initiative and the Politics of Fence-mending with Africa.” In Canada Among Nations 2013. Canada-Africa Relations: Looking Back, Looking Ahead, edited by Yiagadeesen Samy and Rohinton Medhora, 239–51. Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2013.

- Blackwood, Elizabeth, and Veronika Stewart. “CIDA and the Mining Sector: Extractive Industries as an Overseas Development Strategy.” In Struggling for Effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, 217–45. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

- Bodruzic, Dragana. “Promoting International Development through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Canadian Government’s Partnership with Canadian Mining Companies.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21, no. 2 (2015): 129–45.

- Brodhead, Tim, and Cranford Pratt. “Paying the Piper: CIDA and Canadian NGOs.” In Canadian International Development Assistance Policies: An Appraisal, 2nd ed., edited by Cranford Pratt, 87–119. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996.

- Brown, Stephen. “Aid Effectiveness and the Framing of New Canadian Aid Initiatives.” In Readings in Canadian Foreign Policy: Classic Debates and New Ideas, 3rd ed., edited by Duane Bratt and Christopher J. Kukucha, 467–81. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Brown, Stephen. “Canada’s Development Interventions: Unpacking Motivations and Effectiveness in Canadian Foreign Aid.” In Canada Among Nations 2015. Elusive Pursuits: Lessons From Canada’s Interventions Abroad, edited by Fen Osler Hampson and Stephen M. Saideman, 139–159. Waterloo, ON: Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2015.

- Brown, Stephen. “CIDA’s New Partnership with Canadian NGOs: Modernizing for Greater Effectiveness?” In Struggling for Effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, 287–304. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

- Brown, Stephen. “From Ottawa to Kandahar and Back: The Securitization of Canadian Foreign Aid.” In The Securitization of Foreign Aid, edited by Stephen Brown and Jörn Grävingholt, 113–37. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Brown, Stephen. “Undermining Foreign Aid: The Extractive Sector and the Recommercialization of Canadian Development Assistance.” In Rethinking Canadian Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, Molly den Heyer and David R. Black, 277–95. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2014.

- Brown, Stephen. “When Policy Coherence is a Bad Thing.” Blog Entry, Centre for International Policy Studies, University of Ottawa. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.cips-cepi.ca/2014/02/03/when-policy-coherence-is-a-bad-thing/.

- Brown, Stephen, and Michael Olender. “Canada’s Fraying Commitment to Multilateral Development Cooperation.” In Multilateral Development Cooperation in a Changing Global Order, edited by Hany Besada and Shannon Kindornay, 158–88. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Bueckert, Michael. “CIDA and the Capitalist State: Shifting Structures of Representation under the Harper Government.” Studies in Political Economy 96 (2015): 3–22.

- Butler, Paula. Colonial Extractions: Race and Canadian Mining in Contemporary Africa. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

- Campbell, Bonnie. “Peace and Security in Africa and the Role of Canadian Mining Interests: New Challenges for Canadian Foreign Policy.” Labour, Capital and Society 37, no. 1 and 2 (2004): 98–129.

- Campbell, Bonnie. “Regulation & Legitimacy in the Mining Industry in Africa: Where does Canada Stand?” Review of African Political Economy 35, no. 117 (2008): 367–85.

- Cameron, John D. “Revisiting the Ethical Foundations of Aid and Development Policy from a Cosmopolitan Perspective.” In Rethinking Canadian Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, Molly den Heyer and David R. Black, 51–65. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2014.

- Canadian International Development Agency. “Reviewing CIDA’S Bilateral Engagement. Countries of Focus and Modest Engagement Partners: Qualitative Assessment.” Accessed December 23, 2015. https://www.dropbox.com/s/8fe4en6edwofa2p/CIDA%20atip%20countries%20of%20focus.pdf.

- Canadian International Development Agency. Statistical Report on International Assistance, Fiscal Year 2005–2006, Gatineau, QC: CIDA, 2008.

- Canadian International Development Agency. Statistical Report on International Assistance, Fiscal Year 2006–2007. Gatineau, QC: CIDA, 2009.

- Canadian International Development Agency. Statistical Report on International Assistance, Fiscal Year 2007–2008. Gatineau, QC: CIDA, 2010.

- Canadian International Development Agency. Executive Report on the Evaluation of the CIDA Industrial Cooperation (CIDA-INC) Program. Gatineau, QC: CIDA, 2007.

- Deen, Thalif. “Development Aid on the Decline, Warns New Study.” Inter Press Service. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/12/development-aid-on-the-decline-warns-new-study/

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. “Evaluation of the Investment Cooperation (INC) Program,” September 2012. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.international.gc.ca/department-ministere/evaluation/2012/inc_pci12.aspx?lang=eng.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. Global Markets Action Plan: The Blueprint for Creating Jobs and Opportunities for Canadians through Trade. Ottawa: DFATD, 2013.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. “Minister Fantino’s Keynote Address to the Economic Club of Canada Titled ‘Reducing Poverty—Building Tomorrow’s Markets,’” November 23, 2012. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/acdi-cida.nsf/eng/NAT-1123135713-Q8T.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. “Minister Oda Announces Canadian Partnerships in International Development,” December 23, 2011. http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/ACDI-CIDA.nsf/eng/NAT-1222104721-LJ6.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. “Minister Oda Announces Initiatives to Increase the Benefits of Natural Resource Management for People in Africa and South America,” September 29, 2011. http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/acdi-cida.nsf/eng/car-929105317-kgd.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. Synthesis Report—Summative Evaluation of Canada’s Afghanistan Development Program. Fiscal year 2004–2005 to 2012–2013. Gatineau, QC: DFATD, 2015.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. “Today, the Honourable Julian Fantino, Minister of International Cooperation Issued a Statement Following the Release of Economic Action Plan 2013,” March 21, 2013. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/acdi-cida.nsf/eng/ANN-321154018-R3R.

- Global Affairs Canada. “Development Priorities.” Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.international.gc.ca/development-developpement/priorities-priorites/aidagenda-planaide.aspx?lang=eng.

- Global Affairs Canada. “International Development Project Browser.” Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.international.gc.ca/development-developpement/aidtransparency-transparenceaide/browser-banque.aspx?lang=eng.

- Global Affairs Canada. “Post-2015 Development Agenda—Government of Canada Priorities”. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.international.gc.ca/development-developpement/priorities-priorites/mdg-omd_consultations.aspx?lang=eng.

- Global Affairs Canada. “Statement by Minister Paradis: Development as an Integral Part of Canadian Foreign and Trade Policy.” Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.international.gc.ca/media/dev/speeches-discours/2013/12/05a.aspx?lang=eng.

- Global Exchange. “Top 10 Corporate Criminals List.” Accessed August 26, 2013. http://www.globalexchange.org/corporateHRviolators.

- Gordon, Todd and Jeffery R. Webber. “Imperialism and Resistance: Canadian Mining Companies in Latin America.” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 63–87.

- Goyette, Gabriel C. “Charity Begins at Home: The Extractive Sector as an Illustration of Changes and Continuities in the New De Facto Canadian Aid Policy.” In Rethinking Canadian Aid, edited by Stephen Brown, Molly den Heyer, and David R. Black, 259–75. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2014.

- House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development. 2012. Driving Inclusive Economic Growth: The Role of the Private Sector in International Development. Ottawa, Public Works and Government Services Canada.

- Joya, Angela. “Failed States and Canada’s 3D Policy in Afghanistan.” In Empire’s Ally: Canada and the War in Afghanistan, edited by Jerome Klassen and Greg Albo, 277–305. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013.

- Kapoor, Ilan. The Postcolonial Politics of Development. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Mackrael, Kim. “Commercial motives driving Canada’s foreign aid, documents reveal.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/commercial-interests-taking-focus-in-canadas-aid-to-developing-world/article16240406/.

- Mackrael, Kim. “Fantino defends CIDA’s corporate shift.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/fantino-defends-cidas-corporate-shift/article5950443.

- Mackrael, Kim. “Ottawa signals shift in foreign-aid policy toward private sector.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ottawa-signals-radical-shift-in-foreign-aid-policy/article5582948.

- Mackrael, Kim. “Ottawa urges development of foreign-aid mining projects.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ottawa-appoints-first-mining-counsellor-in-more-than-a-year/article23238251.

- Mackrael, Kim. “Ottawa’s elimination of CIDA brand signals end of a foreign-aid era.” The Globe and Mail. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ottawas-elimination-of-cida-brand-signals-end-of-a-foreign-aid-era/article12878309.

- Morrison, David R. Aid and Ebb Tide: A History of CIDA and Canadian Development Assistance. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1998.

- Munson, James. “Past failure not deterring CIDA minister from business partnership model.” iPolitics. Accessed December 23, 2015. www.ipolitics.ca/2012/12/04/past-failure-not-deterring-cida-minister-from-business-partnership-model.

- North, Liisa, Timothy David Clark, and Viviana Patroni, eds. Community Rights and Corporate Responsibility: Canadian Mining and Oil Companies in Latin America. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006.

- Official Development Assistance Accountability Act, S.C. 2008, c. 17. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/O-2.8/FullText.html.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Canada. Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Peer Review 2012. Paris: OECD, 2012.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Query Wizard for International Development Statistics.” Accessed December 23, 2015. http://stats.oecd.org/qwids.

- Oved, Marco Chown. “After the gold rush.” Toronto Star. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2014/12/01/burkina_faso_after_the_gold_rush.html.

- Oved, Marco Chown. “Fool’s Gold: The limits of tying aid to mining companies.” Toronto Star. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2014/12/15/fools_gold_the_limits_of_tying_aid_to_mining_companies.html.

- Oved, Marco Chown. “Ghana: Canadian aid project goes off the rails.” Toronto Star. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.thestar.com//news/world/2014/12/08/ghana_canadian_aid_project_goes_off_the_rails_1.html.

- RepRisk. Most Controversial Mining Companies of 2011. Zurich: RepRisk, 2012.

- Shane, Kristen. “Budget to be Balanced on Backs of Poor, Say Critics.” Embassy, April 4, 2012: 5.

- Sunderland, Ruth. “Oil companies accused of helping to fuel Sudan war crimes.” The Guardian. Accessed August 26, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jun/13/oil-fuelled-sudan-war-crimes.

- Tiessen, Rebecca. “‘Walking Wombs’: Making Sense of the Muskoka Initiative and the Emphasis on Motherhood in Canadian Foreign Policy.” Global Justice 8, no. 1 (2015): 1–22.

- Watson, Paul “Canada’s Afghan legacy: Failure at Dahla Dam.” Toronto Star. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2012/07/14/canadas_afghan_legacy_failure_at_dahla_dam.htm.

- Watson, Paul. “Canada’s Afghan legacy: Plan for Kandahar dam was dropped when mission ended, U.S. says.” Toronto Star. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2012/07/25/canadas_afghan_legacy_plan_for_kandahar_dam_was_dropped_when_mission_ended_us_says.html.

- Whittington, Lee. “Canadian mining firms worst for environment, rights: Report.” Toronto Star. Accessed August 21, 2013. http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2010/10/19/canadian_mining_firms_worst_for_environment_rights_report.html.

- Wroe, David. “AusAid swept under Foreign Affairs control.” Sydney Morning Herald. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/ausaid-swept-under-foreign-affairs-control-20130918-2tztf.html.