ABSTRACT

This paper reports the findings of the first systematic literature review (SLR) of studies on the intercultural approach as captured by two inter-connected articulations: interculturalism (IC) and intercultural dialogue (ICD). Initially, 16,582 available peer-reviewed articles and book chapters published over the period 2000–2017, were identified. After removing duplicates, 11,712 unique studies provided the basis for this SLR. The contents of the publications that met specified inclusion criteria and explicitly discussed the conceptual underpinnings of IC and its related ICD concept (N = 351) were analysed. Despite a more salient position in recent diversity governance discussions, IC and ICD have remained largely constrained by a lack of conceptual clarity and theoretical precision. This SLR, therefore, examines how IC and ICD have been accounted for, defined, and conceptualised across a broad-ranging literature spaning multiple disciplines. The findings indicate that the key conceptual and philosophical foundations of the intercultural idea are framed around interaction, dialogue, exchange and transformation. The SLR articulates four dimensions as the key constituents of the overall intercultural framework and no significant divergence between them was found between various definitions of IC and ICD. IC provides the conceptual foundations that enable an ICD articulation around intercultural exchange and dialogue across differences.

Introduction

The question of understanding and responding to new forms of super-diversity is emerging as a key socio-political challenge polarising contemporary multicultural societies everywhere (Mansouri Citation2017; Modood Citation2014; Vertovec Citation2007; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). This renewed polarisation follows a period during the second half of the last century that saw post-colonial rights-based approaches gaining ground over traditionally assimilationist approaches (Bouchard Citation2011; Cantle Citation2012). Renewed debates over the extent of recognition of minority claims presents significant challenges to migration and diversity studies and related academic fields. Two prominent approaches in this field have particularly been the subject of intense academic and philosophical debate for more than four decades. The first of these is multiculturalism (MC), a pro-diversity approach, that recognises and accomodates cultural rights, equality, and justice for migrant groups (Levrau Citation2018; Modood Citation2014). The second – and more recent approach – is interculturalism (IC), a contact-based approach to diversity management that emphasises intergroup interaction, exchange and dialogue (Zapata-Barrero Citation2019). This paper focuses on IC and the related concept of intercultural dialogue (ICD), and presents a systematic review of research around its philosophical underpinnings and conceptual articulations across disciplines. Yet, before we do this we need to contextualise IC within political, historical and conceptual debates.

The Political and Historical Context

The intercultural approach is not altogether new. In fact, it predates the current diversity management debate with the ‘intercultural’ notion itself arising well before the concept was formulated a decade or so ago into the European version largely addressed in Western scholarship (Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). And while the European version of IC emphasises the notion of contact and exchange, at the micro level, between citizens and groups with civil society (Levrau Citation2018), Canadian IC, especially as articulated in Quebec, is primarily ‘based on the understanding of the predominance of francophone culture’, and aims ‘to build and integrate other cultural communities into a common public culture based on the French language, while respecting diversity’ (Ghosh Citation2011: 7). This diversification of IC interpretations and approaches is further highlighted in the context of the post-colonial Latin American context, where a different version of IC, interculturalidad, has long existed in education (Solano-Campos Citation2013). However, the earliest mention of contemporary IC, and one that this paper is concerned with, dates back to the early 1980s (Council of Europe Citation2008; Modood Citation2014) when it emerged as a possible diversity policy instrument in Canada, with the particular purpose of maintaining Québécois national identity (Bouchard and Taylor Citation2008; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). A few decades later, IC began to gain more international prominence in immigrant integration studies and diversity governance circles. This re-emergence was accelerated with the release of the 2008 Council of Europe White Paper (Council of Europe Citation2008; Delany-Barmann Citation2010; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017).

The political and socio-cultural context within which the White Paper emerged in Europe was characterised by rising levels of anti-migrant feelings, perceived lack of integration of minorities and more salient security threats brought about through the so-called global war on terror. Since then, a large body of multi-disciplinary research has appeared, much of which focuses on whether the IC approach is theoretically distinct from, if not superior to, its MC counterpart (Cantle Citation2012; Kymlicka Citation2012; Meer and Modood Citation2012; Taylor Citation2012). In terms of disciplinary framing, much of the current debate is concentrated in the fields of international relations, migration studies, education, and other related disciplines.

While IC research has expanded over the last two decades, it remains a little understood concept with its theoretical distinctiveness still somewhat unclear (Ganesh and Holmes Citation2011; Meer and Modood Citation2012; Phipps Citation2014). In addition, there has been no agreement on its conceptual boundaries, in relation to other concepts and theories, most notably, MC (Levrau and Loobuyck Citation2013; Modood Citation2017). Nevertheless, the intercultural approach has gained ground in the literature, particularly following the articulation of ICD in Europe, with its focus primarily on the applied and practical policy implementations compared to the more general and abstract articulations within IC (Council of Europe Citation2008; Holmes Citation2014; Phipps Citation2014; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation, UNESCO Citation2013; Wiater Citation2010). The Council of Europe White Paper and various UNESCO documents on ICD are often cited as the basis for policy discussions, whereas much of the scholarly discussion deals with IC’s theoretical foundations. Yet, there remains a great deal of overlap between ICD and IC, with the former being approached as a policy and practice manifestation of the latter (Mansouri and Zapata-Barrero Citation2017; Rattansi Citation2011; Wiater Citation2010).

All of the overlaps, lack of theoretical distinctness and conceptual boundaries surrounding IC suggest the urgent need for a systematic and robust review of the diverse intercultural literature in order to provide a more precise and nuanced understanding of the intercultural approach, its theoretical underpinnings as well as its potential application. Therefore, this systematic literature review (SLR) aims to clarify the current knowledge base around the IC/ICD framework, focussing on associated misconceptions and lack of conceptual clarity. In doing so, this SLR maps and synthesises current research in this area with a focus on academic research outputs published between 2000 and 2017.

Theoretical Context

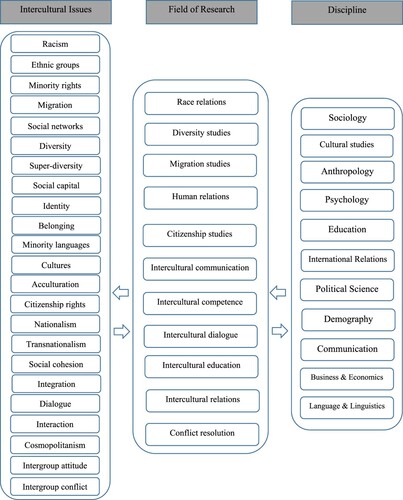

In general terms, the intercultural idea aims to address a number of critical questions about how people relate to one another, and how these interactions are framed, shaped and enacted in everyday situations. More substantively, other key relevant questions relate to how individuals and groups of people from different cultures interact with one another; how they live well together despite differences pertaining to language, culture, religion, ethnicity and other socio-cultural orientations; how they resolve conflicts arising from cross-cultural misunderstandings; and how their daily encounter with diversity shapes their attitudes, behaviours and experiences. To-date, researchers have grappled with these and other related questions across many disciplines – including education, sociology, language, geography and demography, communication, psychology, business and economics, political science and others. An array of fields of research has evolved over the last few decades attempting to account for and analyse intercultural issues. Among these are intercultural education, intercultural communication, intercultural relations, intercultural competence, intercultural understanding, intercultural conflict, cultural studies and cosmopolitanism. IC and ICD are the most recent and prominent conceptualisations, falling within this multidisciplinary domain, and particularly focusing on providing a distinct approach to the governance of super-diversity – a phenomenon reflecting complex socio-cultural expressions of identity and attachments (Vertovec Citation2007; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017).

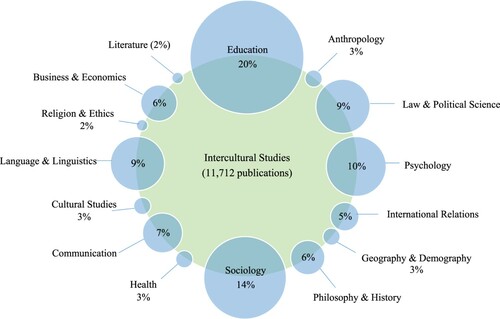

presents a conceptual diagram of the broad intercultural approach in the literature. The size of each circle indicates the relative number of intercultural research outputs produced within respective disciplines as reported in the systematic search in this SLR.

Each of the disciplines in approaches interculturalism from its unique perspective. For example, intercultural research in education mainly focuses on intercultural skills and competencies from pedagogic perspectives, while sociological and political studies focus on the governance of super-diversity. Similarly, communication research focuses on dialogue and inter-personal interaction while social psychology studies tend to emphasise the salience of intergroup contact and attitudes in intercultural relations. Other disciplines, including cultural studies, human geography, business management, linguistics and others have also their own areas of focus, including interculturality in the context of cultural heritage, urban design, workplace, and language use. A comprehensive classification of intercultural studies is beyond the scope of this SLR, however, the disciplinary breadth screened within this SLR clearly shows the wide-ranging multi-disciplinarity that characterises various intercultural ideas (See ).

Intercultural Theory

The emergence of intercultural theory has to be understood within various key conceptual debates. First, research on migrant integration and the dynamics of diversity management has traditionally placed a dichotomous wedge in discourses on identity versus diversity, assimilation versus multiculturalism, and exclusion versus inclusion (Joppke Citation2005; Portes and Vickstrom Citation2011). However, the recent talk of a backlash on MC and the renewed migration debate necessitate new theorising that transcends fixed analytical categories and traditional conceptual dichotomies. Our analysis of the IC literature explores whether its emphasis on bridging cultural differences and building intercultural relationships, can provide the basis for a robust and innovative approaches to ‘super-diversity’.

Second, social cohesion and intercultural contact have recently emerged as the two interlinked thematic benchmarks of the intercultural approach. A perceived deficit in social cohesion served as the motivation for the search for a new approach to diversity governance while contact offered the potential to bridge gaps across contours of cultural differences. This connection between IC and broader social cohesion agendas is increasingly reflected in the diverse multidisciplinary approaches to all matters IC as can be seen in , extracted from this SLR.

Third, interest in intercultural approaches to diversity management grew from global security concerns, particularly in a post-9/11 climate of the perceived weakening of social cohesion, and a consequent resurgence of xenophobic nationalism, racism, and violent extremism (Cantle Citation2012; Council of Europe Citation2008; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). These manifestations of inter-group tensions have stimulated academic and policy debates focused on articulating alternative policy approaches that emphasise common ground and shared values within culturally diverse societies. This alternative perspective argues for approaching cultural and ethnic difference as a neutral demographic attribute and thus avoiding extreme positions of previous approaches, such as assimilation and (superficial accounts of) MC, where difference is either simplistically problematised or merely celebrated. Traditionally, much of the policy debates and related theorising around the management of diversity has indicated the increasing difficulty of achieving social cohesion in culturally diverse societies (Portes and Vickstrom Citation2011; Putnam Citation2007). In this context, an intercultural framework emphasising shared values and social contact was predicted to engender enhanced inter-personal interaction and engagement, potentially dispelling misunderstandings, stereotypes, and intergroup prejudice (Levrau and Loobuyck Citation2013). By engaging members of diverse groups in a respectful dialogue process, the goal of bridging differences and realising a shared vision becomes more attainable (Ngada and Zúñiga Citation2003; Putnam Citation2007).

In addition, a theoretical distinction of the intercultural approach has been its relational notion of social contact – a well-established theory in social psychology – underlining the significance of interpersonal and intergroup relationship in shaping society (Donati Citation2009; Levrau and Loobuyck Citation2013; Ngada and Zúñiga Citation2003). Particularly, the contact hypothesis holds that positive interaction between members of different groups has the potential to reduce intergroup prejudice, foster positive attitudes and promote tolerance (Allport Citation1954; Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2005). Such interaction, emphasising reciprocity, exchange and dialogue between members of different cultures, lies at the heart of an intercultural approach to managing diversity (Bouchard and Taylor Citation2008; Zapata-Barrero Citation2016). Taking a step further, this SLR identifies four distinct dimensions that have been articulated in relation to IC and ICD in the studies analysed.

Interculturalism and Intercultural Dialogue

Apart from the issues rasied above, this SLR needs to be contextualised within an intercultural theory that has often been described in social science as an approach that prioritises interaction among individuals from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds. Normatively, it seeks to achieve the goals of fostering social cohesion through ‘exchange and interpersonal relations, using … the “technique of positive interaction” to ensure a favourable public environment for intercultural contact’ (Zapata-Barrero Citation2016: 155).

In the literature, IC and ICD are seen as closely interrelated conceptualisations within the broader field of intercultural theory. Indeed, some scholars have used both interchangeably, with dialogue being premised on conducive societal conditions (Besley and Peters Citation2011; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). Yet, at a deeper conceptual level, much of the intercultural literature also discusses the two concepts separately (for example, IC: Abdallah-Pretceille Citation2006; Bouchard Citation2011; Taylor Citation2012; ICD: Ganesh and Holmes Citation2011; Wiater Citation2010). IC, in this context, signifies a theoretical perspective that emphasises the need for cross-cultural interaction and communication, and is seen as containing the epistemological tools necessary for addressing super-diversity (Zapata-Barrero Citation2016). ICD, on the other hand, features more prominently in policy debates and has been referred to as a particular application, or to use Cantle’s words as ‘an instrumental part of interculturalism’ (Cantle Citation2015: 84).

The important feature that connects IC and ICD remains the emphasis on and adherence to dialogue as an interactive process for bridging differences. In both conceptualisations, dialogue is seen as the vehicle through which the desired interaction is achieved within conditions that include local settings, macro policies and leadership (Besley and Peters Citation2011; Ganesh and Holmes Citation2011; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017).

Multiculturalism and Interculturalism

This SLR also speaks to a growing concern within IC literature for more clarity around its conceptualisation and definition. Blair (Citation2015) has pointed to the lack of a universally accepted definition of IC and many other scholars have added that this lack of conceptual precision means that it is difficult to connect it to other related concepts such as MC, cosmopolitanism or transnationalism (Downing Citation2015; Levey Citation2012; Meer and Modood Citation2012; Uberoi and Modood Citation2013). These and other scholars argue that many of these concepts are discursively fluid and carry meanings that are multifarious, incorporating multiple themes and policy rhetoric at the same time. Specifically, some scholars have depicted IC as an ‘updated version’ of MC (Lentin Citation2005: 394) while others hold that it is conceptually and practically altogether distinct from MC (Bouchard Citation2011; Cantle Citation2012; Hadjisoteriou, Faas, and Angelides Citation2015; Taylor Citation2012; Zapata-Barero Citation2016). According to this argument, IC emphasises the need for a new politics of intercultural engagement, active citizenship and social engagement, moving away from the politics of recognition that is central to the philosophical underpinings of MC (Benhabib, Citation2002). Indeed, many scholars describe IC as a midway proposition between assimilation and MC, which are at the two ends of the diversity management continuum (Corrie Citation2014; DesRoches Citation2014).

The literature that we review is embedded within the broad diversity management debates, in which IC has been intertwined with the increasingly politicised MC discourse. IC was formally introduced in the 2008 Council of Europe White Paper, which highlighted the failure of social integration policies, the saliency of hyper-securitised agendas, and particularly a perceived ‘backlash’ against MC at the political and ideological levels (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2012; Council of Europe Citation2008; Meer and Modood Citation2012). However, its invocation as a potential conceptual and policy alternative has received mixed reviews in academe, policy and practice (Mansouri and Aber Citation2017). Proponents of IC have pointed to a growing dissatisfaction with MC as the key justification and rationale for seeking alternative approaches aimed at addressing new challenges pertaining to super-diversity (Cantle Citation2012). The circulating public anti-MC rhetoric alleges that MC policies have contributed, directly or indirectly, to segregated ethno-cultural divisions, rising racism, xenophobic sentiments, growing socio-economic inequalities, and surging international terrorism (Meer and Modood Citation2012). Modood (Citation2017) argues that such critiques, as well as others levelled against MC, are methodologically and conceptually difficult to sustain when examined against empirical realities. Moreover, the two competing concepts (MC and IC) seem to operate at different levels in terms of engagement and governance. Many scholars contend that the conceptual distinction between MC and IC remains vague and that the supposed differences around their implementation are imprecise and confused (Guilherme and Dietz Citation2015; Mansouri and Aber Citation2017; Meer and Modood Citation2012). Still, others see a clear distinction between the two concepts, with IC perceived as promoting mutual cultural exchange with an emphasis on social cohesion and shared values, and recognising the problematic recognition of the existence of majority/minority dynamics (Bouchard Citation2011; Cantle Citation2012; Zapata-Barrero Citation2017). Whether these characteristics are indicative of mutually exclusive policy paradigms or complementary approaches towards the diversity agenda remains an ongoing policy and theoretical debate in diversity governance (Mansouri and Aber Citation2017; Mansouri and Zapata Barrero Citation2017). However, there appears to be substantial level of overlap between both approaches, as we show later in this SLR.

Recently, discussions have started to emerge attempting to elucidate more clearly the distinct theoretical foundations of each approach and focusing on their potential complementarities (Levrau and Loobuyck Citation2013). For example, although MC and IC have elements of dialogue and relationality, the precise level of such interaction varies between these approaches (Meer and Modood Citation2012; Parekh Citation2006; Taylor Citation1994). While dialogue and relationality within the broad MC framework are predicated to take place at the macro-level, within IC they have greater impetus at the micro-level where the emphasis is more on individual cross-cultural interaction and engagement (Modood Citation2014). To generate even more clarity about the distinctive elements of IC in its own right and in comparison to other concepts such as MC, this SLR systematically consults the IC literature from across a wide range of academic disciplines within the social sciences and humanities as depicted in and . This SLR aims to provide a more precise conceptual understanding of the philosophical assumptions behind IC as well as its key drivers and conditions.

Research Questions

The aim of this SLR is captured in three research questions: (1) What is the current state of research on intercultural issues? (2) How has the intercultural approach to diversity, particularly IC and ICD, been framed and conceptualised in the broad literature? (3) What are the key dimensions defining the intercultural approach as articulated and employed in multi-disciplinary intercultural debates?

Methods

Research Design

The present SLR uses descriptive and qualitative methods to review systematically relevant research on intercultural issues. SLR, as opposed to a traditional literature review, allows for the consideration of all relevant existing evidence related to a specific research question (Glasziou et al. Citation2001; Petticrew and Roberts Citation2008). SLR applies rigorous searches, analyses and interpretation of all available evidence pertaining to a specific research question based on unbiased and reproducible study protocols (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic Citation2015; Petticrew and Roberts Citation2008). SLR findings can provide strong conceptual foundations for future research directions on the topic reviewed.

Current research on all things ‘intercultural’ indicates persisting conceptual imprecision regarding the exact meanings and definitions of the intercultural notion as embodied in the concepts of IC and ICD (Modood, Citation2017). Despite substantial research emerging over the last two decades, these intercultural concepts remain in need of further conceptual elaboration and articulation (Gropas and Triandafyllidou Citation2011; Levey Citation2012). The findings of this SLR, therefore, aim to provide conceptual clarity for future theorising and potential policy application. Drawing on the contact theory and inter-group contact literatures, our research applies an inductive approach to framing the data analysis. The size of our sample also allowed us to match thematic categories with outputs extracted from a wide-ranging literature.

Data Collection

Search strategy: data sources and search key

outlines the review protocol for this SLR, incorporating all the relevant features used in standard systematic reviews. Seven electronic databases (Scopus, Web of Sciences, PsychInfo, ERIC, Political Science Complete, EconLit, and Urban Studies Abstracts) were searched using a specific search key composed of terms relating to intercultural issues. These databases were considered the most appropriate for this study, as intercultural issues are anchored mainly in social sciences and humanities. Therefore, the searches were restricted to relevant subject areas, including the broad disciplines associated with social sciences, arts and humanities, business, accounting and management, psychology, health and economics. Keywords were selected to identify references of the word ‘intercultural’ and its variant ‘inter-cultural’ either as a single word or hyphenated in a combination phrase such as intercultural dialogue or intercultural competence (Hoskins and Sallah Citation2011). Three other words, ‘cosmopolitanism’, ‘diversity’, and ‘cultural diversity’, were also used to identify potentially relevant articles, due to their theoretical proximity to intercultural issues (Donald Citation2007; Noble Citation2009). The search was qualified further by adding the context in which the word or phrase was used (definition, conceptualisation, theory, framework, policy or practice).

Table 1. Systematic literature review protocol.

While there exists significant grey literature on intercultural approach to diversity, the purpose of this SLR was to examine current knowledge around the concepts of IC and ICD, therefore restricting the search to academic publications. An initial extensive search showed that a general intercultural approach has been used at various levels and in various domains, both in research and policymaking. Therefore, our main goal was to examine what is currently known about IC and ICD, as applied in these domains. Thus, we ask ‘how has the “intercultural” been conceptualised in the literature’? and ‘how has it been articulated and employed in multidisciplinary intercultural debates’?

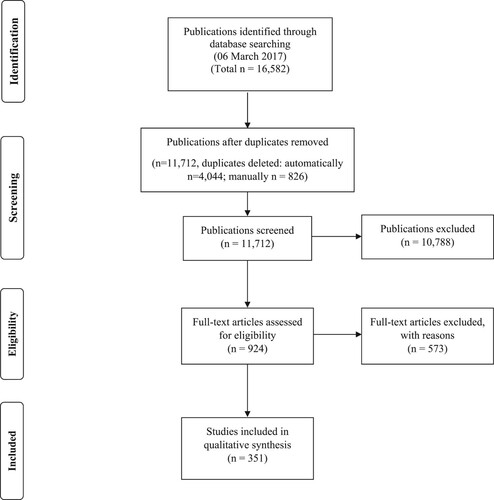

We performed a search by title and abstract in the seven databases, using the search key: (intercultur* OR inter-cultur* OR cosmopolitan* OR ‘intercultural dialog*’ OR ‘intercultural comptenc*’ OR ‘intercultural communication’) AND (defin* OR concept* OR theor* OR framework OR policy* OR practice). The electronic searches were conducted on 6 March 2017, and resulted in 16,582 publications (see ). During the primary search, irrelevant studies from non-social science disciplines were removed.Footnote1 The numbers of publications by database are: Scopus = 5,982; Web of Science = 2,856; PsycINFO = 2,627; ERIC = 2,305; Political Science Complete = 2,300; EconLit = 283; Urban Studies Abstracts = 229.

Selection and Eligibility

All publications from the electronic search were imported into EndNote and merged into a single global database. In EndNote, all duplicates were automatically identified and removed. The remaining publications were then screened for missing duplicates that were manually removed before the studies passed to the next stage of screening. Overall, 11,712 unique publications were identified during the preliminary search. Publication period was restricted to the period 2000–2017. We acknowledge here that some works on intercultural issues (6.5 per cent of the overall output) were published much earlier, notably Floyd Allport’s seminal research on inter-group contact in the 1950s. However, we believe that much of this work is strongly reflected in the more contemporary literature captured by this SLR. Only articles published in academic journals and book chapters fully available in English were included. Studies with abstracts in English but full-text in non-English language were excluded. A two-stage screening was applied to these publications.

Title and abstract screening

In the first stage, the titles and abstracts of all studies were screened manually and automatically. Automatic searches were conducted within EndNote for the titles and abstracts, with the purpose of identifying studies that were not relevant to the research theme. Keywords such as ‘climate’, ‘environment’, ‘gender’, ‘sex’, ‘language immersion’, ‘Internet’, ‘digital’, ‘virtual culture’, ‘Music/film’, ‘Global politics’, ‘global security’, ‘international relations’, ‘international law’ were used to locate studies for relevance. The studies automatically identified were marked for exclusion if their titles and abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria. To retain potentially relevant studies with these keywords, three researchers manually screened the titles and abstracts of all the marked studies (n = 10,459).

The screening was undertaken separately to ensure reliability and credibility of the inclusion/exclusion process. To ensure screening uniformity, a 10 per cent sample (n = 228) was randomly selected from the remaining studies (n = 2,281). All three researchers screened this sample and a lead reviewer compared each reviewer’s screening result for disagreements and inconsistencies (92 per cent agreement rate). Disagreements were resolved through discussions among the reviewers. Any study with an exclusion keyword that met the inclusion criteria was included for further screening. Altogether, 7,368 studies were identified based on the exclusion keywords and 2,510 studies manually screened did not meet the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, 913 studies were excluded because of language (non-English) or publication-type criteria. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 924 studies from the electronic search sample were retained for full-text screening (see ). Before moving to full-text screening and data extraction, the review criteria were further clarified among the research team. To determine the final list of studies retained for full-text screening, the lead reviewer checked the abstracts of all studies that the two reviewers included for further screening.

Full-text screening

In the second stage of screening, a double-blind, full-text screening of all eligible publications (n = 924) was conducted by two reviewers. This full-text screening was conducted based on the following criteria. (1) Studies that explicitly discussed the key intercultural issues and concepts outlined in the research questions were included.Footnote2 A study was excluded if it mentioned the word ‘intercultural’ but did not engage with intercultural concepts or issues. (2) Studies were included if intercultural issues/concepts were the main theme of the study. In other words, a major part (at least one third) of the included study should address intercultural issues/concepts. (3) A study was excluded if the ‘intercultural’ concept it addressed did not align with a social science domain pertaining to the interaction of people from different cultural, religious, ethnic, or national backgrounds. (4) Finally, only studies whose full texts met the main inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in were included.

Two reviewers screened the full texts of each publication with the goal of identifying and extracting information relevant to the research questions of this study regarding the conceptual and policy underpinning of ‘intercultural issues’ in the context of ‘super-diversity’. A third reviewer compared the results of the full-text screening. A good agreement rate of 73 per cent was obtained (see Hallgren Citation2012). Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the two double-blind reviewers and the third researcher. The final sample of publications included for the final content review was 351 (see ), including journal articles and book chapters.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The qualitative content analysis of the final outputs was conducted in two sequential stages. One reviewer conducted a comprehensive screening of the 351 publications, aimed at extracting information pertinent to the research questions. After data extraction, a second reviewer verified the data to ensure accuracy and consistency with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The relevant data extracted from each publication included:

Title, author(s), and year of publication;

Type of publication (journal article, book, or book chapter);

Type of the report (theoretical or empirical);

Country under study;

Study period;

Definitions of key terms (IC and ICD) if provided;

Publication’s research focus (conceptualisation, policy, practice, or a combination);

Research method employed (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method);

Main ‘intercultural issue’ topic addressed in the publication (such as, ICD, IC, intercultural understanding, interfaith/interreligious dialogue, interculturality, intercultural awareness, intercultural education, intercultural competency, intercultural communication, cosmopolitanism, and/or cultural diversity);

Evaluation of IC/ICD within the publication (outright rejection, negative critique, neutral, positive critique, or outright acceptance).

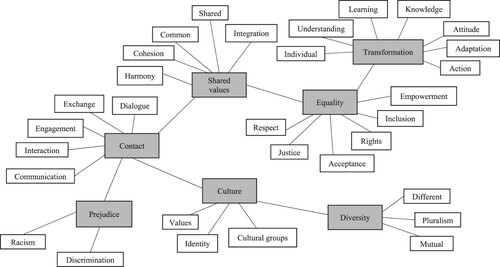

Coding

The extracted definitions for IC and ICD were coded drawing on Allport’s intergroup contact theory (Allport Citation1954; Pettigrew Citation1998). Seven themes were inductively used as pivots in analysing the codes; these were contact, diversity, culture, shared value, equality, prejudice, and transformation. Data for each definition were then separately entered in NVivo for coding. Based on the data, we identified a total of 39 relevant codes for ICD and 37 for IC. Our threshold criterion was to include a code if at least three publications mentioned the word in a definition. After comparing the coded data with the seven thematic categories, we concluded that one dimension – prejudice – did not meet the threshold criterion for the definition of ICD, and was therefore dropped. The other six dimensions fitted the data in describing the identified definitions’ structures (see ). The definitions were summarised using five levels of coding each related to five questions: how IC/ICD is conceptualised; what it intends to achieve (purpose); how it is framed; what level of focus it has; and what and how many components each definition has.

Table 2. Coding the conceptualisations of interculturalism and intercultural dialogue.

Analysis

Due to the widespread variation in the objectives, study focus, methods, including study design and analytical approaches, a narrative synthesis – an approach that utilises words and text in summarising and synthesising study findings – rather than a meta-analysis was considered the appropriate approach to summarise and review the studies included (Mays et al. Citation2005; Popay et al. Citation2017). All of the 351 studies were imported into NVivo for content analysis. The analysis involved a synthesis of the conceptualisations, relationships, methods of analysis, key findings and conclusions of the current research, based on the data extracted from the list of studies selected for inclusion in this SLR. Definitions of IC and ICD provided were particularly analysed in more detail, in order to clarify the intercultural notion.

Results

Description of the Studies

Country and publication year

describes the studies analysed in this review, with most of the studies (90 per cent) being journal articles published after 2005, and geographically covering the six continents. Furthermore, more than a third (131/351) of the publications focused on a single country, with another third (115/351) having no geographic reference. The remaining publications focused on a specific region(s) as the unit of analysis.

Table 3. Systematic literature review: publications reviewed in this study.

Method and scope of the study

Of the 351 publications reviewed, 195 were theoretical in nature or dealt with policy reviews, while 153 articles reported empirical findings. Most of the latter (142 of 153 studies) applied qualitative methods, with only 11 studies based on quantitative surveys. The studies varied in terms of their practical relevance in current debates on diversity governance. While 87 articles discussed the conceptual underpinnings of IC/ICD, the rest examined the way these are understood and implemented in policy and practice.

Thematic focus

Overall, the studies included in this SLR exhibited eight main thematic focus areas. Almost 70 per cent focused on three themes: interculturalism (83 articles), ICD (82 articles), and intercultural education (79 articles). Interculturality and interreligious dialogue were two other themes examined in 33 and 26 studies respectively. Additional 34 studies dealt with cultural diversity, intercultural competency, and intercultural communication as the main themes. All of these studies discussed IC, ICD or both, as the main theme or as a sub-theme of the overall narrative.

While the extent of coverage given to IC and ICD varied across studies, two distinct views on the intercultural framework were identified. Roughly, 10 per cent rejected or criticised IC/ICD as an alternative to MC, whereas 66 per cent argued that the intercultural approach offers a new/better paradigm for thinking about and/or managing diversity. An additional 17 per cent of the studies saw the latter as potentially useful but needing conceptual precision, while 7 per cent were neutral in their assessment.

Articulations of IC and ICD

An increasing number of studies have examined IC and ICD over the last decade on the basis of conceptualisations and framings that emerged after the Council of Europe’s Citation2008 White Paper. They discussed the intercultural framework in relation to ‘super-diversity’ and the potential of IC/ICD in its governance. In 153 studies, definitions were provided for either IC (74 articles) or ICD (67 articles) with only 12 publications providing definitions for both concepts.

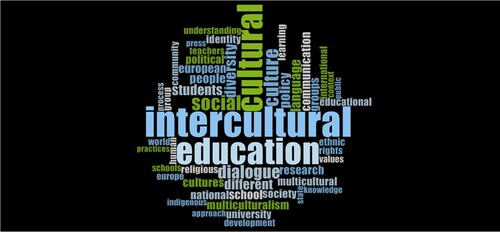

A qualitative analysis using NVivo generated a word cloud of the 50 most frequent words in the sample. The full-text of all 351 studies were browsed to find the frequency of mentions of intercultural issues using the keywords ‘intercultural’, ‘interculturalism’ and ‘intercultural dialogue’. All three alternative searches returned the same result, with terms such as intercultural, culture/al, education, social, and dialogue featuring most frequently ().

Thematic Analysis

Using Allport’s intergroup contact theory (Allport Citation1954; Pettigrew Citation1998) a particular thematic pattern can be constructed from the definitions of IC and ICD contained in the reviewed studies. reports this thematic pattern, anchored in the notion of contact and six other interrelated themes – diversity, culture, shared value, equality, prejudice, and transformation. Lahdesmaki and Wagener (Citation2015) have used a related semantic analysis on the conceptualisation of ICD using the White Paper document. Yalaz and Zapata-Barrero (Citation2018) have also used similar thematic analysis in mapping and examining migration research. This SLR uses the occurrences of words related to the six themes across the included publications. The emerging pattern indicates that contact is the underlying conceptual basis of IC and ICD. Similarly, the management of cultural diversity in the absence of prejudice is seen as the target of the intercultural approach, with respect, equality and shared values afforded greater emphasis, and individual transformation considered the ultimate goal.

Defining Interculturalism

The SLR identified and examined 114 definitions of IC either explicitly and distinctly provided or paraphrased creatively across 74 different scholarly outputs. Of these, 27 articles provided a set of unique definitions, and 27 articles used either direct quotes or paraphrased definitions already provided by other authors. Twenty articles provided both their own definitions and quotes or paraphrases. Some of the sources for these quotes and paraphrased definitions were publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria for this SLR (for example, publications other than journal articles and book chapters). While the majority (67 per cent) of the cited definitions were from various authors, the rest (33 per cent) cited definitions provided by eight different authors. The most frequently cited definitions were those of the Council of Europe (Citation2008) and Bouchard and Taylor (Citation2008), quoted eight and five times respectively. Other definitions that were cited at least twice included those provided in Cantle (Citation2012), Powell and Sze (Citation2004) and Rattansi (Citation2011).

Below, we summarise the definitions using five levels of coding: conceptualisation, purpose, framing, focus, and component of IC. and report the coding results, with values indicating the number of definitions in which a given code representing concepts, words, ideas or phrases appears.

Table 4. Framing, focus and components in the definitions of interculturalism.

Table 5. Conceptualisation and purpose of interculturalism.

Framing, focus and components

The way IC is framed in academic literature in relation to conceptualisation and policy articulation varies considerably. In this SLR, a majority of the definitions framed IC as a practical approach (25 definitions), a concept or theoretical framework (19 definitions) or a public policy (13 definitions; see ). Another 29 definitions framed it as an abstract idea, political ideology, personal perspective, attitude or skill, as an instrument or tool, as a model, paradigm, attempt, or as a process. Twelve definitions use a variety of framings while no specific framing was provided in 32 definitions.

While almost all of the 75 articles defined IC as something related to diverse cultures, the level of focus varied across the definitions (see ). Of those that specified the focus of the given definition, the majority (58/87 definitions) indicate cultures, cultural groups or groups as the focus of the intercultural framework. In 22 definitions, IC was described in reference to individuals, communities, people, citizens and societies. Four other definitions indicated cities, students or young people as the levels of focus.

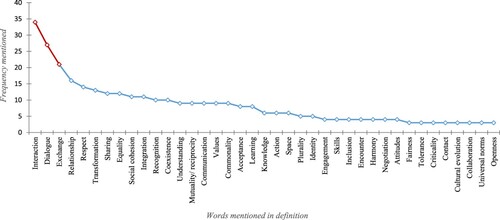

Another defining factor in the conceptualisation of IC relates to its key components or constituent elements with at least 39 such components identified in this SLR. As indicated in , three words – interaction, dialogue and exchange – appeared more frequently than any other word, as the key components of IC, appearing in 33, 27 and 21 definitions respectively. Overall, the list can be classified into four broad components:

Relational, including words such as interaction, dialogue, exchange, relationship, communication; total appearances: 125;

Normative, including words such as equality, recognition, acceptance, inclusion, respect; total appearances: 62;

Transformative, including words such as transformation, understanding, learning, knowledge, attitude; total appearances: 62; and

Integrative, including words such as sharing, social cohesion, integration, coexistence, mutuality, reciprocity; total appearance: 83.

Purpose and conceptualisation

A recurring aspect in this SLR is the representation of IC as a normative basis of social policy with specific objectives. Ninety-nine references were identified across the articles as having definitions explicitly articulating what IC seeks to achieve in society. summarises a list of 21 objectives, classified into four broad goals, corresponding to the four components listed above.

Corresponding to the integrative component are four objectives focused on the promotion of social cohesion, common or shared values, cultural identity, facilitation of social integration and fostering peaceful coexistence (mentioned in 41 definitions). Closely related to the normative component are eight social justice objectives usually associated with MC. These include the promotion of social inclusion and equality; acceptance and respect of difference; elimination of racism/discrimination and creation of a fair and just society that empowers cultural minorities (mentioned in 28 definitions). Fifteen definitions focused on transformative objectives, including the expansion of knowledge and skills, and the promotion of mutual understanding that lead to individual and cultural transformation. Finally, another 15 definitions focused on structural issues corresponding to the relational components. These include the management of diversity, creation of space for democratic pluralistic society, reconciliation of universal values and cultural diversity, and encouragement of participation/engagement in society by overcoming institutional and relational barriers.

Across the 75 articles with definitions, 136 different discursive conceptualisations of IC were identified. Based on their similarities and emphases, classifies these into 19 distinct conceptualisations. The most frequently articulated of these is the conceptualisation of IC as a ‘dialogue or exchange between cultures’ (53 definitions). This in turn was described in various ways, including ‘proactive engagement’, ‘bi-directional interaction’ and ‘relationship’ among other categorisations.

IC has been invoked several times in discussions around the new global reality of diversity/super-diversity (Cantle Citation2012; Zapata-Barrero Citation2015). In this SLR, 30 definitions conceptualising IC as a framework for thinking about diversity were identified. These framings identify IC as an approach/policy for addressing/managing diversity; a framework for remedying the defects of multiculturalism; or as a theorisation for negotiating coherence/universality and diversity.

Furthermore, a set of 34 definitions uniquely conceptualised IC in relation to social cohesion, commonality and co-existence. In these definitions, IC is perceived as a process for communicating and sharing across difference; as a vision for creating social cohesion or common political culture; or as a framework for the coexistence of people from different cultural backgrounds.

Finally, two sets of definitions conceptualised IC in terms of the multicultural notion of inclusivity. Twenty-eight definitions described IC as recognition, acceptance and respect of cultural pluralism and difference; as an initiative towards social inclusion; or as a framework for reducing prejudice and discrimination. Another 15 definitions associated IC with the pluralist transformation of society or described it as a framework for promoting cultural competency (knowledge, skills, and critical thinking).

Defining Intercultural Dialogue

This SLR examined 95 different definitions of ICD contained across 67 articles. Sixteen articles provided unique self-initiated definitions and 41 articles used either direct quotes or paraphrases of definitions provided in other sources. In 10 articles, the authors provided their own operational definitions on the basis of paraphrased/quoted sources. The most referenced definition of ICD was once again the one provided in the 2008 Council of Europe White Paper. It was cited 32, 17 times in direct quotes and 15 times in paraphrases.

Below is a summary of the key ICD definitions using a coding strategy similar to the one employed in the conceptual analysis of IC. and report a summary of the coding results.

Table 6. Framing, focus and components in the definitions of ICD.

Table 7. Conceptualisation and purpose of ICD.

Framing, focus and components

Our analysis indicates that the literature on ICD draws heavily on the Citation2008 Council of Europe White Paper in terms of framing and focus (see ). A majority of the definitions frame ICD as a dialogue, conversation or form of communication (n = 29), or as a process (n = 20). Another 23 definitions framed it as an approach, method, means, tool/instrument, or as a policy/strategy, with four definitions depicting it as an abstract concept. Seven definitions used a variety of framings, while no specific framing is present in 20 definitions.

Individuals, groups or cultures were prominent as the levels of focus of ICD (80 definitions), although a few definitions indicated other specific subjects as the targets (see ). Thirty-five definitions depicted ICD as focusing on individuals/persons, while groups and cultures were the domains of focus in 27 and 18 definitions respectively. Twenty-three definitions describe ICD specifically in relation to communities, religions, citizens, students, and society at large. Five other definitions used the vague individualised reference ‘participants/interlocutors’.

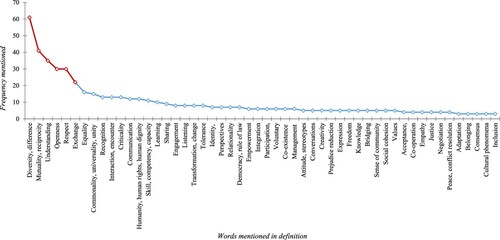

This SLR reveals the use of more concepts in the definitions of ICD than in IC. At least 52 components were identified in 96 definitions, even though the word ‘dialogue’ itself was not included in order to avoid redundancy. indicates six concepts – diversity/difference, mutuality/reciprocity, understanding, openness, respect, and exchange – that featured prominently, appearing more than 20 times each. Categorising this list into the four broad components mentioned above yields the following:

Relational, including key terms such as exchange, communication, interaction, engagement; total appearances: 94;

Normative, including terms and notions such as diversity/difference, respect, equality, recognition, tolerance; total appearances: 151;

Transformative, including words such as understanding, openness, criticality, skills, learning, transformation; total appearances: 137; and

Integrative, including key terms such as mutuality/reciprocity, human rights, commonality, sharing, integration, coexistence; total appearances: 151.

Purpose and conceptualisation

In more than half of the definitions (n = 57, 60 per cent), ICD was articulated in terms of normative social purposes or objectives. These are summarised into 23 specific objectives, classified into four broad goals corresponding to the four components listed above (see ).

Closely related to the normative component, ICD is linked in the reviewed studies to a range of multicultural goals characterised by respectful recognition of difference, tolerance, and social inclusion, among others (mentioned in 51 definitions). Four objectives relate to the integrative component, and focus on the search for consensus or commonality that ensure cohesion and peaceful coexistence (mentioned in 30 definitions). Twenty definitions linked ICD to its transformative component in the form of knowledge and skills enhancement, mutual adaptation and development of new cultural perspectives. Finally, at a more structural level, in 17 definitions, ICD was associated with the goal of creating conditions for reciprocity and interactive engagement, promoting democratic culture, and balancing diversity with social cohesion.

Across the 67 articles, we identified 85 definitions that provide 27 unique conceptualisations of ICD (see ). Two conceptualisations that frequently stood out related to a ‘dialogue based on mutual understanding, respect and acceptance’ (n = 30) and an ‘open dialogue, exchange, or interaction between members of different cultures’ (n = 36).

In the rest of the conceptualisations, ICD was described in terms of inclusivity, relationality, structural utility and integrative and transformative capacity. Forty-three definitions described it as fair expression, interaction or communication; as an encounter allowing for the retention of cultural identity; as a dialogue acknowledging equality between cultures; and as a dialogue fostering mutual understanding, among others. Another five definitions articulated ICD as a ‘tool for relationship between cultures’ or as a ‘framework for bridging differences across cultures’.

In 28 definitions, ICD was conceptualised as a diversity management tool that operates within a human rights framework. Specifically, it was conceived as a framework for thinking about difference; an approach for managing diversity; an approach for negotiating cohesion; and a dialogue for addressing democracy and human rights. Unlike in the case of IC, only 13 definitions emphasised the integrative aspect of ICD. In these definitions, it was conceptualised as a framework for peaceful coexistence; a process for sharing across differences; a framework for social integration; an inclusive alternative to multiculturalism; and as a communication that leads to consensus or universal norms. Finally, 16 definitions highlighted the transformative nature of ICD. The conceptualisations varied from its description as dialogue leading to attitudinal change to dialogue promoting creativity and knowledge, and from being an approach for critical self-reflection to a basis for an examination of existing cultures including one’s own culture.

Discussion

In light of the growing academic and policy debates around the utility and conceptual clarity of IC/ICD as a framework for diversity governance, this SLR mapped and analysed scientific evidence around these concepts on the basis of studies published between 2000 and 2017. Starting with a total list of 16,582 outputs, we identified 351 publications that met our inclusion criteria, with articles and book chapters published in more than 15 countries, and covering a diversity of themes related to IC and ICD.

Our analysis examined the broader intercultural framework by first looking at how it has been understood and framed within academic and philosophical debates, noting that intercultural ideas more broadly are not new in social sciences and humanities. In sociological research for example, scholars have studied intercultural understanding, particularly within education settings and in relation to cultural differences since the early twentieth century (Brown Citation1939). However, IC, and more specifically ICD, in its current form, emerged more prominently only after it was initially adopted in public policy discussions (Council of Europe Citation2008). Particularly since the turn of the century, both concepts have been framed in relation to the management of community relations in the context of ‘super-diversity’, with contact and interaction being suggested as inherent to the intercultural approach (Cantle Citation2012; Zapata-Barrero Citation2016). Most of the studies analysed in this SLR trace the root of the IC debate to the Council of Europe Citation2008 White Paper. However, much of the discussions that ensued since have been framed in terms of acceptance or rejection of the IC/ICD framework as an alternative to either assimilation or MC (Agustín Citation2012; Joppke Citation2018). Among the studies we analysed, although 83 per cent at least partially accepted IC/ICD, 10 per cent rejected it as an adequate diversity governance framework.

While noting the salience of the intercultural/multicultural debate, our goal in this SLR was to elucidate the wide-ranging and overarching level of overlap in the literature on the intercultural framework itself. Thus, our analysis closely examined the way studies framed, conceptualised and located the conceptual focus and policy purpose of IC/ICD. While the definitions of IC and ICD showed some overlap, the main findings of this SLR can be summarised as follows:

IC is conceived as an approach or framework for contact, dialogue and interaction between individuals and cultures that involve proactive exchange and bi-directional engagement involving both minority and majority groups.

IC is also viewed as a potential basis for managing super-diversity by encouraging cross-cultural contact, mutual learning and exchange across differences. Its main purpose is promoting shared values, fostering social cohesion and nurturing an ethos that prioritises recognition of difference and peaceful coexistence.

ICD in particular is understood as a process-driven framework that encourages open dialogue and meaningful interaction based on mutual understanding, respect and acceptance of cultural differences. Its main purpose is the recognition, respect and acceptance of difference, as well as fostering deeper understanding of diverse perspectives and practices in the context of possible public contestation of claims around cultural and religious rights. In this sense, it is a more grounded concept that aims to build integrative affinities within diverse societies.

Following from the above, ICD can then be viewed as a basis for engendering transformative (positive) change among individuals and by extension their communities. At the individual level, ICD emphasises behavioural transformation and cultural attitudinal change that can, in theory, challenge existing hierarchical relations between groups (Cantle Citation2015; Bouchard and Taylor Citation2008; Barrett Citation2013).

Generally, the analysis of the various definitions of IC and ICD yielded four key conceptual dimensions – relational, integrative, normative and structural/transformative – that can be considered as key philosophical assumptions framing and constituting the intercultural framework (Barrett Citation2013). These partially correspond to Zapata-Barrero’s three ‘normative policy drivers’ and Berry’s framework of the ‘core elements and linkages’ (Berry Citation2016; Zapata-Barrero Citation2016). In proposing his ‘contractual’, ‘cohesive’, and ‘constructivist’ strands as distinct perspectives of IC, Zapata-Barrero (Citation2016: 167) conceives the intercultural paradigm as an ‘interplay between tradition, cohesion and innovation’. In Berry’s framework, the main goal of the Canadian multicultural policy is to foster ‘mutual acceptance’ through three programmes – cultural support, social intercultural contact, and intercultural communication. The framework accommodates many of the components of IC we identified, including mutuality, understanding, contact, interaction, communication, acceptance, learning, participation and integration (Berry Citation2016).

Yet, Berry (Citation2016: 413) also distinguishes between three aspects of managing diversity: ‘the multiculturalism principle; the integration principle; and the contact principle’. These distinctions are consistent with what emerged in the literature. Along with a transformative element, the relational (contact), integrative, and normative (in Berry’s classification, the multicultural) aspects prominently featured as the key constituents of an intercultural approach to diversity (for example, Abdallah-Pretceille Citation2006; Bouchard and Taylor Citation2008; Taylor Citation2012; Zapata-Barrero Citation2016).

Relational Dimension

The relational dimension highlights the communicative aspect of the intercultural framework, where relationships through contact are considered the fundamental ethos (Council of Europe Citation2008; Joppke Citation2018). The findings of this SLR corroborate the conception that dialogic exchanges and interactions are the most important features of an intercultural approach, often depicted in ICD terms. We have identified contact and dialogue as well as concepts related to these, such as interaction, relationship, communication and exchange, as consistently recurring themes in both IC and ICD. These individual-level, inter-group, and cross-cultural relationships and communications are considered vital for achieving desired social goals of equality, social inclusion, and social cohesion in a culturally diverse society (Broome and Collier Citation2012). The Council of Europe (Citation2011, para. 1) has further emphasised the need for contact and interaction:

rather than ignoring diversity (as with guest-worker approaches), denying diversity (as with assimilationist approaches) or overemphasising diversity and thereby reinforcing walls between culturally distinct groups (as with multiculturalism), interculturalism is about explicitly recognising the value of diversity while doing everything possible to increase interaction, mixing and hybridisation between cultural communities.

Integrative Dimension

An intercultural approach places emphasis on social cohesion and integration as the ultimate goals of diversity policies (Barret Citation2013). As identified in this SLR, the conceptualisation of the intercultural approach as a two-way integration and adaptation process distinguishes it from how integration is espoused in assimilation and to some degree in MC policies. In this regard, IC and ICD are conceived as having bi-directionality in the process of engagement and mutual adaptation between minority and majority groups, thus allowing cultural maintenance as well as adaptation (Berry Citation2016). Some scholars, however, argue that rather than simply ensuring cultural maintenance and adaptation, an intercultural framework, in its integrative dimension, can lead to the creation of new synergetic ‘third cultures’ (Evanoff Citation2006). According to this notion, the rules that are absent but necessary for governing cross-cultural interactions can be constructed through dialogue, whereby cultures are negotiated, contested and reconstructed, leading to the creation of a ‘third culture’ (Evanoff Citation2004; Kramsch Citation1998).

In addition to social cohesion and integration, the concepts of co-existence, sharing and mutuality emerged as integral components of the IC and ICD frameworks. The emphasis in all of these concepts lies in the reciprocal requirements that the intercultural approach engenders, as individuals negotiate and adapt to the requirements of living with difference.

Transformative Dimension

A key feature of the intercultural approach depicted in the literature is an emphasis on its transformative capacity. The goal of the dialogue and interactive exchange that take place in intercultural relationships is transformative change enabled through knowledge, learning, and understanding. Yet, such change should not be associated solely with minority groups adopting the majority culture. Instead, IC offers platforms for bi-directional transformation, where both minority and majority group members are willing to participate in mutual exchange and cross-cultural adaptation. Thus, the dialogic interaction and mutual adaptation processes in IC and ICD would be effective only if majorities are willing to engage meaningfully with members of minority groups (Baumeister Citation2003). The ‘questioning of one’s identity in relation to others is an integral part of the intercultural approach’, thus implying the potential for both sides of the dialogue or exchange to emerge transformed (Abdallah-Pretceille Citation2006). However, in the current context of asymmetrical power relations between majorities and minorities in many societies, achieving the conditions for genuine bi-directional transformation remains a challenge (Baumeister Citation2003).

Normative Dimension

Our findings indicate that the IC framework in its normative aspect, shares a great deal with the multicultural perspective that has also been defined as emphasising ‘an appreciation of the value of cultural diversity for a society, and a need for mutual acceptance and accommodation that promotes equitable participation’ (Berry Citation2016: 416–417). In most studies, the normative notions of respect, mutual understanding and acceptance of diversity and difference are understood as the core foundations of IC that are vital for its integrative and transformative objectives (Bouchard and Taylor Citation2008; Cantle Citation2012; Ponciano and Shabazian Citation2012).

In consistently portraying IC and ICD in terms of intergroup relationships, the literature represented the intercultural approach as a framework for contact and peaceful coexistence. Writing before the millennium, Michael James [not reviewed here] noted that critical ICD requires that participants should ‘adopt an attitude of openness towards each other’s cultural perspectives; … come to understand each other’s perspectives; and … communicate under conditions which they mutually can accept as fair’ (James Citation1999: 590). Since then, research on intercultural approaches has expanded, with scholars calling for a more theoretical depth and conceptual clarity around what distinguishes IC/ICD from alternative normative approaches to diversity (Guilherme and Dietz Citation2015). This SLR has partly responded to these calls, laying potential groundwork for further empirical examination of IC/ICD.

Conclusion

In this SLR, the focus was mainly on peer-reviewed publications examining the different ways in which IC and ICD have been conceptualised across disciplines. Thus, a large body of the grey literature has not been included, making this the main limitation of the SLR. Further studies exclusively focused on these works should make a significant contribution to our study. Furthermore, the choice of ‘intercultural’ as the main search term reflects recent and current research pertaining to diversity management policies, excluding earlier related work on the inter-group theory, particularly the pioneering work on the inter-group contact hypothesis (Allport and others). However, this and other related works were cited extensively in the literature we reviewed, and it should be noted that systematic reviews of the contact hypothesis have been previously conducted (Miles and Crisp Citation2014; Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2008). Moreover, the exclusion of international literature not published in English represents another significant constraining factor in this SLR particularly as it excludes the influential body of work built on the work of Alfonso Ortiz that has emerged across Latin America. Similarly, much of the literature from other parts of the world including Asia and Africa will have been missed if it was not published in English, either originally or through translation. Again, this represents a significant handicap in terms of conducting a genuinely comprehensive SLR that reflects the world’s major intellectual traditions in intercultural matters.

Nevertheless, this SLR was undertaken on the basis of an extensive systematic search of the accessible literature defined within specific temporal and thematic confines. The findings of this SLR are clear in pointing to an intercultural approach to diversity, conceptualised as IC and ICD, that is predicated on interactive contact and mutually transformative dialogue between individuals and groups across difference. The surveyed literature reflects the conceptual challenge to precisely locate and define IC as a distinct approach particularly as it engages related concepts and theories, most notably MC. While further research is needed to deepen the theoretical grounding of the IC framework, this SLR has attempted to synthesise current research in the area, clarifying that the intercultural approach represents at least four dimensions – relational, normative, integrative, and transformative – where much of the reported IC research appears to have converged. Our research indicates that despite the explosion of IC research, there has been limited attempts to integrate IC with previous inter-group and relational theories. Future research should address this limitation and further investigate this theoretical link. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the majority of IC and ICD research has been theoretical, with limited applied and qualitative analysis. Thus, more empirical research based on quantitative data is urgently needed to examine the utility and practical applicability of the intercultural approach within everyday encounters.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the helpful comments by Ricard Zapata-Barrero, Vince Marotta, and anonymous reviewer on an earlier manuscript of this article. We are also grateful to Tuba Boz, Natalia Pereira and Scheherazade Bloul for excellent research assistance, and Jenny Lucy for helpful editorial assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanuel Elias

Dr Amanuel Elias is a Research Fellow at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, at Deakin University, Australia. He received Masters in Economics from Monash University and PhD in Economics from Deakin University. Dr Elias’ interdisciplinary research focuses on race relations, ethnic inequalities and cultural diversity.

Fethi Mansouri

Professor Fethi Mansouri is the Director of the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation at Deakin University, Australia. He holds the UNESCO Chair in comparative research on Cultural Diversity and Social Justice and an Alfred Deakin Research Chair in migration and intercultural studies. His research interests focus on migration, comparative refugee research, global Islamic politics, multiculturalism and intercultural relations.

Notes

1 The following disciplines were included: social sciences, arts and humanities, business, management and accounting, psychology, economics, econometrics and finance, nursing, decision sciences, health professions, and multidisciplinary.

2 Some of the relevant concepts were intercultural dialogue, interculturality, interculturalism, intercultural education, intercultural communication, intercultural relations, intercultural competence, and interfaith/interreligious dialogue.

References

- Abdallah-Pretceille, M., 2006. Interculturalism as a Paradigm for Thinking About Diversity. Intercultural Education, 17 (5), 475–483.

- Agustín, ÓG, 2012. Intercultural Dialogue Visions of the Council of Europe and the European Commission for a Post-Multiculturalist Era. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 29.

- Allport, G.W., 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

- Banting, K., and Kymlicka, W. 2012. . Is There Really a Backlash Against Multiculturalism Policies? New Evidence from the Multiculturalism Policy Index. Working Paper 2012-4.

- Barrett, M. 2013. Introduction – Interculturalism and Multiculturalism: Concepts and Controversies. Council of Europe Publishing. F-67075, Strasbourg Cedex.

- Baumeister, A., 2003. Ways of Belonging: Ethnonational Minorities and Models of ‘Differentiated Citizenship’. Ethnicities, 3 (3), 393–416.

- Benhabib, S., 2002. Transformations of Citizenship: The Case of Contemporary Europe. Government and Opposition, 37 (4), 439–465.

- Berry, J., 2016. Diversity and Equity. Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 23 (3), 413–430. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-03-2016-0085.

- Besley, T., and Peters, M.A., 2011. Interculturalism, Ethnocentrism and Dialogue. Policy Futures in Education, 9 (1), 1–12.

- Blair, K., 2015. Young Adults’ Attitudes Towards Multiculturalism in Australia: Tensions Between the Multicultural State and the Intercultural Citizen. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 36 (4), 431–449.

- Boell, S.K., and Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., 2015. On Being ‘Systematic’ in Literature Reviews. In: L. P. Willcocks, C. Sauer, and M.C. Lacity, ed. Formulating Research Methods for Information Systems. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 48–78.

- Bouchard, G., 2011. What is Interculturalism? McGill Law Journal, 56 (2), 395–468.

- Bouchard, G., and Taylor, C., 2008. Building the Future: A Time for Reconciliation. In: T. Das Gupta, C.E. James, C. Andersen, G. Galabuzi, and R.C.A. Maaka, ed. Race and Racialization, 2E: Essential Readings. Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 302–317.

- Broome, B.J., and Collier, M.J., 2012. Culture, Communication, and Peacebuilding: A Reflexive Multi-Dimensional Contextual Framework. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 5 (4), 245–269.

- Brown, F.J., 1939. Sociology and Intercultural Understanding. The Journal of Educational Sociology, 12 (6), 328–331.

- Cantle, T., 2012. Interculturalism: The New Era of Cohesion and Diversity. London: Springer.

- Cantle, T., 2015. Implementing Intercultural Policies. In: R. Zapata-Barrero, ed. Interculturalism in Cities: Concept, Policy and Implementation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 76–95.

- Corrie, J., 2014. The Promise of Intercultural Mission Transformation. An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies, 31 (4), 291–302.

- Council of Europe. 2008. White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue. Living Together as Equals in Dignity. Accessed 20 August 2019. Available from: https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/intercultural/source/white%20paper_final_revised_en.pdf.

- Council of Europe. 2011. Intercultural City: Governance and Policies for Diverse Communities. Accessed 7 April 2019. Available from: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/culture/cities/Interculturality_en.pdf.

- Delany-Barmann, G., 2010. Teacher Education Reform and Subaltern Voices: From Política to Práctica in Bolivia. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 9 (3), 180–202. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2010.486276.

- DesRoches, S.J., 2014. Québec’s Interculturalism: Promoting Intolerance in the Name of Community Building. Ethics and Education, 9 (3), 356–368.

- Donald, J., 2007. Internationalisation, Diversity and the Humanities Curriculum: Cosmopolitanism and Multiculturalism Revisited. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 41 (3), 289–308.

- Donati, P., 2009. Beyond the Dilemmas of Multiculturalism: Recognition Through ‘Relational Reason’. International Review of Sociology, 19 (1), 55–82. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700802613947.

- Downing, J., 2015. European Influence on Diversity Policy Frames: Paradoxical Outcomes of Lyon’s Membership of the Intercultural Cities Programme. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38 (9), 1557–1572. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2014.996241.

- Evanoff, R.J., 2004. Universalist, Relativist, and Constructivist Approaches to Intercultural Ethics. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28 (5), 439–458.

- Evanoff, R.J., 2006. Integration in Intercultural Ethics. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30 (4), 421–437.

- Ganesh, S., and Holmes, P., 2011. Positioning Intercultural Dialogue – Theories, Pragmatics, and an Agenda. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 4 (2), 81–86.

- Ghosh, R. 2011. The Liberating Potential of Multiculturalism in Canada. Ideals and realities [Special Edition, spring]. Canadian issues, 3–8.

- Glasziou, P., et al., 2001. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: A Practical Guide. University Press: Cambridge.

- Gropas, R., and Triandafyllidou, A., 2011. Greek Education Policy and the Challenge of Migration: An ‘Intercultural’ View of Assimilation. Race Ethnicity and Education, 14 (3), 399–419.

- Guilherme, M., and Dietz, G., 2015. Difference in Diversity: Multiple Perspectives on Multicultural, Intercultural, and Transcultural Conceptual Complexities. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 10 (1), 1–21. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1015539.

- Hadjisoteriou, C., Faas, D., and Angelides, P., 2015. The Europeanisation of Intercultural Education? Responses From EU Policy-Makers. Educational Review, 67 (2), 218–235.

- Hallgren, K.A., 2012. Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8 (1), 23.

- Holmes, P., 2014. Intercultural Dialogue: Challenges to Theory, Practice and Research. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14 (1), 1–6. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2013.866120.

- Hoskins, B., and Sallah, M., 2011. Developing Intercultural Competence in Europe: The Challenges. Language and Intercultural Communication, 11 (2), 113–125. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2011.556739.

- James, M.R., 1999. Critical Intercultural Dialogue. Polity, 31 (4), 587–607. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2307/3235237.

- Joppke, C., 2005. Exclusion in the Liberal State: the Case of Immigration and Citizenship Policy. European Journal of Social Theory, 8 (1), 43–61.

- Joppke, C., 2018. War of Words: Interculturalism v. Multiculturalism. Comparative Migration Study, 6 (1), 11. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0079-1.

- Kramsch, C., 1998. Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kymlicka, W., 2012. Comment on Meer and Modood. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33 (2), 211–216.

- Lahdesmaki, T., and Wagener, A., 2015. Discourses on Governing Diversity in Europe: Critical Analysis of the White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 44, 13–28.

- Lalander, R., 2010. Between Interculturalism and Ethnocentrism: Local Government and the Indigenous Movement in Otavalo-Ecuador. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 29 (4), 505–521.

- Lentin, A., 2005. Replacing ‘Race’, Historizing the ‘Culture’ in the Multiculturalism. Patterns of Prejudice, 39 (4), 379–396.

- Levey, G.B., 2012. Interculturalism vs. Multiculturalism: A Distinction Without a Difference? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33 (2), 217–224.

- Levrau, F., 2018. Introduction: Mapping the Multiculturalism-Interculturalism Debate. Comparative Migration Studies, 6 (1), 13.

- Levrau, F., and Loobuyck, P., 2013. Should Interculturalism Replace Multiculturalism? A Plea for Complementarities. Ethical Perspectives, 20 (4), 605–630. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2143/EP.20.4.3005352.

- Mansouri, F., ed. 2017. Interculturalism at the Crossroads: Comparative Perspectives on Concepts, Policies and Practices. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Mansouri, F., and Arber, R., 2017. Conceptualizing Intercultural Understanding Within International Contexts: Challenges and Possibilities for Education. In: F. Mansouri, ed. Interculturalism at the Crossroads: Comparative Perspectives on Concepts, Policies and Practices. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 25–46.

- Mansouri, F., and Zapata-Barrero, R., 2017. Postscript: What Future for Intercultural Dialogue? In: F. Mansouri, ed. Interculturalism at the Crossroads: Comparative Perspectives on Concepts, Policies and Practices. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 317–329.

- Mays, N., Pope, C., and Popay, J., 2005. Systematically Reviewing Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence to Inform Management and Policy-Making in the Health Field. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 10 (1, Suppl.), 6–20.

- Meer, N., and Modood, T., 2012. How Does Interculturalism Contrast with Multiculturalism? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33 (2), 175–196.

- Miles, E., and Crisp, R.J., 2014. A Meta-Analytic Test of the Imagined Contact Hypothesis. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 17 (1), 3–26.

- Modood, T., 2014. Multiculturalism, Interculturalisms and the Majority. Journal of Moral Education, 43 (3), 302–315. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2014.920308.

- Modood, T., 2017. Must Interculturalists Misrepresent Multiculturalism? Comparative Migration Studies, 5 (15), 1–17. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-017-0058-y.

- Nagda, B.R.A., and Zúñiga, X., 2003. Fostering Meaningful Racial Engagement Through Intergroup Dialogues. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 6 (1), 111–128.