ABSTRACT

‘The term encounter has been used in various disciplines to indicate a bringing together of difference (people, groups, ideas, etc.) with an aim of some form of positive or beneficial outcome’ [Standish, K., 2021. Encounter Theory. Peacebuilding, 9 (1), 1–14.]. Allport [Allport, G.W., 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books] suggests that contact between different groups might lead to a positive change and the reduction in stereotypes, but later research shows that often conflict is more likely to arise. Nonetheless, while contact might presuppose co-existence and thereby, the enduring presence of conflict, encounter ‘is much more than that and involves a space where being with is the outcome itself’ (Standish 2021: 40). It is my contention that the ambivalent nature of the encounters that occur in the Calaisian space generates a layered level of dislocation for those who are entering this space. By definition 'ambivalent’ implies that feelings and reactions are mixed or contradictory. It argues that the ambivalence of these encounters shape not only people of the move’s experiences but also the discourses around them, leading to constant tensions and shifting allegiances, and ultimately the maintenance of the status quo.

Introduction

It is a weekday afternoon in Calais in April 2023. Care4Calais volunteers are visiting the camp sites to give tea and coffee to people who are in the different settlements around Calais beach and its environs, providing them with services such as haircuts, charging points for their mobile phones, some English books should they wish to read, and games should they wish to destress. In Calais centre, Secours Catholique (SC), a charity organisation, has a dedicated space in Calais to welcome individuals and families travelling to the UK and who need access to a safe space, a moment of respite alongside food and drinks, and to charging points, opens its doors in the early afternoon. The men and youths are in the larger section of the building, which includes a sleeping area, a communal area where they play games, watch films or learn French, an outside space where they can play football, basketball or just sit and a communal shower space next to an area where food and drinks are available. Here, humanitarian organisations, agencies and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), such as the Red Cross, ECPAT and Terre d’Asile also operate. The Red Cross enables anyone wishing to do so to find missing family members. ECPAT looks after the unaccompanied minors and tries to provide them with support while they are in Calais, while Terre d’Asile, as its name suggests, provides services for those who wish to claim asylum in France itself. The women’s (and children’s) side is a space inaccessible to men. It is overseen by female volunteers with SC while organisations such as Refugee Women’s Centre (RWC) and Project Play (PP) cater to other needs: RWC will find clothing, accommodation and provide the immediate services needed by the newly arrived women and children, while PP is solely focused on the children, providing them with games, and activities. In the absence of PP volunteers, who on other days provide these services to children in Lune Plage and safehouses scattered around Calais and Dunkirk, SC has its own stock of games, toys, and resources to keep the children occupied. The charities have referral processes in place, they also have a network of safe houses and other accommodation where the newly arrived families can be housed temporarily until they leave. Calais is thus the site of daily encounters between those who have arrived into this transit space before they attempt their crossing to the United Kingdom, the different humanitarian agencies operating in the area, the local government and ultimately, the French nation. Yet, these encounters can be ambivalent as local and national authorities treat the new arrivals in a different way from the humanitarian agencies and charities operating in Calais. For instance, in January 2023 there were ‘at least 71 evictions in 13 living sites’, during which 14 arrests were made and ‘at least 113 tents’ were stolen (HRO Citation2023). Evictions are carried out very frequently by the local police at the behest of the local government, leading to the newly arrived feeling that on the one hand they are receiving aid, and on the other, they are dehumanised within the same nation, such that their encounters with the French are ambivalent ().

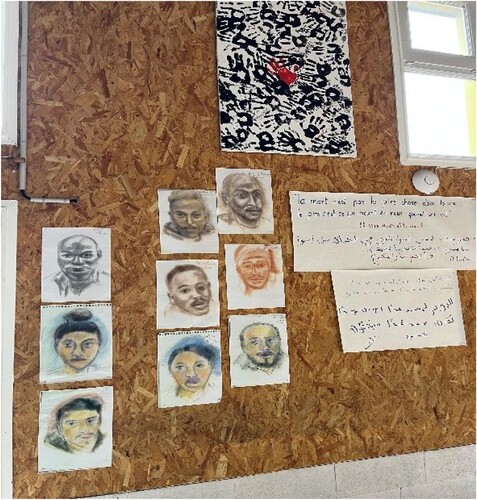

Figure 1. Secours Catholique, Men’s side. Portraits drawn by a volunteer.

In Old French, the word ‘encontre’ meant ‘a meeting, fight, and opportunity’ the difference here being that the space of engagement presents both a challenge (or fight) but also a chance, possibility or opening of some kind’ (Standish Citation2021: 3). Accordingly, peacebuilding theorist Katerina Standish offers ‘encounter theory’ as a means of conceptualising these engagements. For her, ‘The term encounter has been used in various disciplines to indicate a bringing together of difference (people, groups, ideas, etc.) with an aim of some form of positive or beneficial outcome’ (Standish Citation2021: 3). Gordon Allport (Citation1954) suggests that contact between different groups might lead to a positive change and the reduction in stereotypes, but later research has proven that often conflict is more likely to arise (Paolini and Rubin Citation2010). Nonetheless, while contact might presuppose co-existence and thereby, the enduring presence of conflict, encounter ‘is much more than that and involves a space where being with is the outcome itself’ (Standish Citation2021: 40). Helen W. Wilson further explains that: ‘If encounters have the capacity to destabilise then they also come with risk and vulnerability; they can be as violent as they can be nurturing’ (Citation2017: 606). Wilson’s definition enables us to envisage encounters not only as predicated upon difference but as also conducive to a reframing of the notion as simultaneously fragile and violent, while always evoking change and transformation.

This essay reflects the nature of the word ‘migrant’ and the connotations that it has, as opposed to the term ‘exilés’, which is employed by the charities and third sector to refer to the new arrivals. Given the connotations associated with ‘migrants’ as I discuss in this paper, I refer to such individuals as new arrivals, people on the move or people in transit, only using ‘migrants’ when I am quoting from individuals who have employed the word. It is my contention that the ambivalent nature of the encounters that occur in the Calaisian space generates a layered level of dislocation for those who are entering this space. By definition ‘ambivalent’ implies that feelings and reactions are mixed or contradictory. There is a degree of uncertainty that marks ambivalence, a ‘neither this nor that’ that reflects the very positionality of new arrivals as they are in transit in Calais, and thus not belonging to France or to the UK, and having left their homes behind, not to their home country either. Their view of France is also ambivalent as it varies according to who is interacting with them, and even the compassion that is demonstrated towards them might be politicised (Fassin Citation2005) and a remnant of colonial power structures (Fuchs et al Citation2014; Becker Citation2020). In broad terms volunteers would seem to represent the Levinasian (Citation1961) hospitable side of France, whereas the local authorities and indeed, some of the citizens themselves, offer the opposite, but in quotidian practices, this divide is not always clear, with frictions also occurring between the new arrivals and the organisations providing aid. Focusing on the ambivalent nature of these encounters enables a critical analysis of the nature of hospitality and aids in demonstrating how the liminality and the in-betweenness of the camp are reflected in the mixed feelings that people on the move evoke in others along with their own view of the nation-state.

This essay takes as its point of departure the fact that encounters are processes that are ongoing, and ambivalent encounters, in particular, affect those involved in a range of manners. The study sets up the context of the Calais Jungle and its various iterations, and the people transiting through, before engaging with the complexities of the local authorities’ and the French nation-state’s encounters with them. It then shifts to a discussion of everyday encounters, to investigate how humanitarian organisations work to support the new arrivals but are also limited by their own resources, which can create tensions with the people they are actively trying to support. Thus, bolstered by empirical observations and interviews with key stakeholders in Calais, this essay offers the notion of ambivalent encounters as a way of conceptualising the tensions within the Calaisian space and to consider how these offer a productive means of understanding the constantly shifting terrains of political and ideological inequities that permeate such a space.

Methodology and Limitations

In April 2023, I undertook fieldwork in Calais to observe the provisions in place for young people in Calais.Footnote1 During this time, I observed the work done by SC, RWC and PP, as RWC took care of the families who are arriving with minors, and SC supported them as they arrived on the premises in Calais city centre, looking after men and women and families, providing them with food and respite, while PP organised activities for children. The transient nature of Calais as a migratory space, made it difficult to predict access to interviewees as often the people whom I met one afternoon might have left by the next day. Moreover, arrivals into Calais were often in trying circumstances (being saved from boats, arriving after days or months travelling without a break), so that I could not feasibly and ethically interview anyone as soon as they arrived, so as not to increase their discomfort and to ensure that I was adopting a trauma-informed approach to interviews (Steele and Malchiodi Citation2012; Bent-Goodley Citation2019), thereby avoiding retraumatisation (Alexander Citation2012). I was able to interview three Syrian siblings who had been in Calais for two weeks as they had not been able to cross to the UK, despite three attempts. They were in a better space mentally to engage with my questions and as such I was able to gain some insight into their experiences of Calais, with permission from their father. Moreover, the representatives of the different organisations were constantly on the move, with little time to conduct extended interviews about their daily experiences. Nonetheless, an RWC representative took the time to respond to my questions. My own observations of the work accomplished by the humanitarian organisations and the new arrivals also inform this paper. During my time in Calais, it was not possible to interview local authorities or engage with them, which presents another limitation to this study. Instead, in this paper I discuss the rhetoric deployed by the mayor in her open letter in the national magazine, Le Point, and her deployment of tools such as an inbox for local residents to reveal information on squatters, who are, more often than not, people on the move. This study is therefore not an exhaustive analysis of all the actors at play in Calais. Rather, it offers a more conceptual framework to think about what I call the ambivalent encounters, which I develop following Standish’s notion of ‘encounter theory’, that take place within this space, and the tensions present. Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s notion of ‘strange encounters’ (Citation2000) and Emmanuel Levinas’s notion of hospitality (Citation1961), alongside Standish’s theory, I articulate ambivalent encounters as a new way of conceptualising the frictions, tensions and understandings that occur within the transitory space of Calais, as different actors operate in a fraught environment with their own agendas in place.

The Calais Jungle and ‘Migrants’

The Calais Jungle officially lasted between April 2015 and October 2016. ‘The population included 20 cultural groups and expanded to between 7000 (government data) and 10,000 people’ (Anghel and Grierson Citation2020: 490). On the eve of national elections in 2016, the French state wanted to demonstrate its capacity to eradicate the ‘public problem’ of people on the move by making them disappear along with ‘any trace of their local inscription and their installation in France’ (Agier et al. Citation2018: 8). Though the French state declared that the Calais Jungle was now defunct, this was far from being the case. Only a few months later, it was evident that individuals and families were still coming to Calais with the intention of crossing the Channel to reach the UK. In fact, the origins of the migration crisis at the Franco-British border started in 1990 (Agier et al. Citation2018: 9). The French Red Cross ‘opened a centre for migrants in Sangatte, close to the Euro Tunnel entrance’ in 1999 (Reinisch Citation2015: 515) but this closed down in 2002, testifying to the constant struggle between the humanitarian agencies and charities operating in the area and the local and national authorities who shut them down, and thereby the longstanding ambivalence of their encounters with people on the move. Nowadays, Calais and Dunkirk still have unofficial camps (Anghel and Grierson Citation2020), or ‘jungles’ (Millner Citation2011; Davies et al. Citation2017) that continue to be the temporary homes of individuals and families waiting to cross the Channel. They are not allowed to have tents and their sleeping bags are regularly confiscated by the police as the authorities want to prevent the establishment of another camp (Care4Calais Citation2023; HRO Citation2023). Yet this approach has not deterred people seeking to cross over to the UK.

Though at one point, the Calais Jungle was seen as a potential ‘city’ (Hanappe Citation2018), and as vibrant and homely (Katz Citation2017), the Calais refugee camp as an entity does not exist anymore: many smaller temporary settlements that pop up reflect

the appearance of ever new forms of informal settlements related to the increased mobility of “irregular migrants” across the continent, but also the frequent decision of the authorities to allow for these transient arrangements to emerge and, accordingly, abandon their inhabitants to their destiny, in the hope that they will move elsewhere, quickly and invisibly. (Martin et al. Citation2020: 744)

As we have seen with the highly contested Rwanda scheme and the Illegal Migration Bill, Calais continues to be the point of frictional encounters between those seeking to cross, the French nation-state, which receives considerable sums from the UK government to stop the small boats, and the end point, which is the UK. Since most are in Calais for the precise goal of getting to the UK, Calais and thus, France, is a transitory space. The French nation-state only offers help if the new arrivals wish to claim asylum and since those who are in Calais are there predominantly to reach the UK, France chooses to not give them adequate aid, according to the RWC representative I interviewed. While in the past RWC and other charities used to fight for additional aid for the families seeking to cross, now they are struggling to get access to water and sanitation for the constantly moving camps. Thus, French and international charities are often at odds with local government and the state to protect the human rights of the new arrivals who are constantly marginalised. Per the representative of RWC, before the dismantling of the Calais Jungle in 2016 and the surge in the number of small boats whose owners offer to depart every time the weather is clement, families used to stay for ‘two to three months at a time’. Lorries being the main way through which the crossings to the UK took place meant that only two to three people could depart on board some lorries, so that often those who arrived stayed for months, until it was their turn to leave. RWC used to be able to form longer relationships with the families and individuals who stayed for two to three months. Since the state-mandated dismantling of the Calais Jungle (Agier et al. Citation2018), the dynamic in Northern France and the encounters of so-called ‘migrants’ with the French nation are transitory and often ambivalent and friction prone.

The term ‘migrant’ itself is imbibed with negative connotations. Bridget Anderson argues that the word ‘migrant’ does not denote simply a person crossing national borders into other nation-states. By and large, the term ‘migration’ itself ‘signifies problematic mobility’, so that ‘not all mobility is subject to scrutiny, but “migration” already signals the need for control and in public discourse is often raced and classed’ (Anderson Citation2017: 1532). Nation-state centred understandings of migration are conducive to ‘migrants’ being perceived as ‘intruders who disturb and endanger the alleged cultural homogeneity and social equilibrium of the imagined community of national citizens’ (Scheel and Tazzioli Citation2022: 3). France has a long history of discrimination against ‘migrants’ and immigrants, since it strongly believes in its ‘Français de souche’ rhetoric that promulgates the notion that so-called ‘real’ French people are descendants of a homogeneous community that needs to be protected (Noiriel Citation1988, Citation2001, Citation2007). In so doing, France often pits ‘migrants’ as enemies who must be eliminated. This sentiment reached one of its peaks with the destruction of the Calais Jungle in 2016, after photographs shared around the world made Calais a ‘key element in the representation of the so-called “migration crisis” in Europe’ (Queirolo Palmas Citation2021: 496). It is this image of Calais that has prompted the local authorities, and the Mayor, in particular, to actively create a hostile environment for the new arrivals and deter others from coming to Calais, thereby generating ambivalent encounters.

Encountering the Nation

In November 2022, Natacha Bouchart, Mayor of Calais, published an open editorial entitled: ‘Migrants: le coup de colère de la maire de Calais/ Migrants: the anger of Calais’s mayor’ in Le Point, in which she argues that ‘l’Etat n’est pas à la hauteur/The State does not measure up’ (Bouchart Citation2022), underlining the tensions between local and national governance. Yet people in transit often just see Calais and associate it metonymically to the French nation-state. While she cites her achievements in terms of the provisions she put in place at the height of the crisis that attracted so much attention to Calais worldwide, Bouchart bemoans the fact that despite the dismantling of the Jungle, it is still not seen as the dynamic and vibrant town it is. Instead, a new camp often appears overnight and this provokes in the local inhabitants ‘des inquiétudes compréhensibles quant à la sécurité et la sérénité qu’ils sont en droit d’attendre/ understandable worries in terms of peace and security, which they have the right to expect’ (Bouchart Citation2022). Thus, while some local volunteers work to help the new arrivals, others treat them as a threat to their peace and security, highlighting at the basic level the ambivalence of the new arrivals’ encounters with the locals. Bouchart argues that they do not want anything from France given that their aim is to reach the UK, and thus, they ‘ne doivent plus pouvoir séjourner comme bon leur semble sur notre territoire/should not be able to stay as they wish on our territory’ and that the onus should be on the UK to ensure that they shoulder the responsibility and create laws that make the UK less attractive and to tackle the hidden labour markets which will enable them to work illicitly (Bouchart Citation2022). In this way, the encounters in play within this paradigm are layered as nations are also ambivalent towards each other: they have reciprocal agreements, claim an entente cordiale but rather than sharing the responsibility for those who are crossing the Channel, they lay the blame at each other’s feet for the presence of people seeking to cross to the UK. Bouchart ends her piece with an invitation to the French President and Prime Minister to work together with her to create policies that will ensure that the people involved are housed in special closed centres away from border zones such as Calais. This appeal to the President and Prime Minister also highlights the extent to which Calais’s Mayor is battling on her own and how local governance can be isolated from national governance wherein Bouchart’s problems are seen as local rather than national, although it was Calais’s image as representative of France’s migration crisis that led to the dismantling of the Calais Jungle in the first place.

Bouchart seems to accept that all people on the move who are in Calais are determined to cross to access what they see as the Eldorado of the UK (Bouchart Citation2022). From her article, those who are seeking shelter in Calais should not be her town’s problem, or, indeed, France’s problem. In her text, ‘migrants’ are a homogeneous group of people who only have one aim in crossing to the UK: earning money. The difference in her attitude is seen when La Voix du Nord (Citation2022) reported that Bouchart ‘welcomes Ukrainian migrants in the Calais town hall’. The contradiction in her behaviour is stark. The Ukrainians, too, were waiting to cross to the UK, they, too, were not France’s problem, but they were civilly welcomed and embraced as people who were fleeing from the conflict in Ukraine, whereas many of the people on the move sojourning in Calais who also hail from countries where wars and conflict are raging (Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Eritrea for instance), per my own observations, are unequivocally rejected.Footnote4 The very fact that the Ukrainians were treated differently by virtue of their country of origin underscores the problems that French society has had with people of colour being present on its territory (Fassin Citation2010). Bouchart went as far as asking Calais’s inhabitants to report any ‘migrant’ squatter through an email address specifically created for this purpose (Elle Citation2022), thereby encouraging French citizens to treat them as others who do not belong and who should be excluded not only from France but also from human compassion.

In this treatment of strangers entering Calais, there are parallels to be drawn with Sara Ahmed’s notion of Strange Encounters (Citation2000), and in particular in the way that the stranger is defined by lack of recognition. For Ahmed, it is through the hailing of the other as different from the self that the subject recognises itself and begins to, in a Hegelian sense, ‘dwell in the world’ (Ahmed Citation2000: 24). Difference becomes the yardstick by which the other is judged as belonging or not. The good citizen is defined as a white man protecting the women and children against the ‘figure of the loitering stranger’ (Ahmed Citation2000: 31), and the latter then becomes a danger and someone to be rejected. Embedded in this notion is the fact that the stranger ‘allows the protection of the domestic, social and national space from the outsider inside, the stranger neighbour by projecting danger onto the outsider’ (Ahmed Citation2000: 37). For this to happen, the stranger must come ‘too close to home’, so that the line is crossed and the enforcement is legitimated. Within such spaces, any violence perpetrated against the stranger is condoned and justified as protection. Thus, in the context of Calais, Bouchart feels justified in calling on the citizens to identify strangers, and, in the name of protecting the good citizens of Calais, to report them to the authorities, who in turn, feel vindicated in violently evicting people on the move, though the extent to which this email inbox was in use and not a simple performative gesture is unknown. The contrast with the welcome experienced by the Ukrainians escaping conflict and seeking passage to the UK is plainly visible and is emblematic of the ambivalent encounters within the Calaisian space. While some strangers are deemed worthy and do not evoke fear or the need for protection, others are automatically segregated as threats. These ambivalent encounters enable us to see the very contradictions that are in play in the French nation-state and highlight the society’s deep-seated fear of otherness as detrimental to Frenchness.

It would seem that France has a problem with individuals who come from elsewhere and are hypervisible (Kistnareddy Citation2021), either due to their skin colour or due to their religion, as we have seen with the usual problems around Muslim women and the veil (Ivekovic Citation2004). The immigrant population, which is settled already faces a range of issues around who counts as French and who belongs (Weil Citation1991; Nielson Citation2020). Though France opened its borders to Algerians, Moroccans, Francophone Caribbean and Reunionese individuals in the aftermath of the Second World War in order to rebuild its economy, its hospitality was lacking insofar as it did not welcome them and treated them as workers who would eventually leave (Rosello Citation2008). Often the immigrant workers were ghettoised into marginal spaces just outside cities, such as the Parisian banlieues (Wacquant Citation2008). In this paradigm, too, the French nation-state was ambivalent in its encounter with the other: on the one hand the workers were needed, and on the other, they were not welcome. The French nation-state took decades before enabling those who arrived earlier to bring their families to France, and for the most part still refers to children born to immigrants as ‘second-generation immigrants’ (Simon Citation2003; Sicard Citation2011) rather than the French nationals they are legally. Difference, rather than perceived as a positive attribute, is understood as a threat to social cohesion and to personal safety, as Bouchart herself states in her article in Le Point. Bouchart asserts that her duty is to ensure the safety of the residents, implying that ‘migrants’ are a source of danger. But what differentiates them from the Ukrainian ‘migrants’? Their origins and their skin colour. Such discrimination is at odds with France’s constitution which stipulates that there will not be a ‘distinction de race [race-based distinction]’ (1958, Article 1). Yet, on a daily basis, encounters local authorities in Calais evict people from the makeshift camps and confiscate their belongings (HRO Citation2023), or show indifference, as Marielle Macé (Citation2017) observes in the case of the ‘migrants’ who set up camp on the Quai d’Austerlitz in Paris, or, in the case of the humanitarian organisations and charities that operate in and around Calais and Dunkirk, an engagement with difference that tries to be respectful, compassionate and humane. However, the latter can also create ambivalent experiences for people on the move. For instance, the siblings I interviewed found themselves in temporary accommodation an hour away from Calais by bus, and in a former mental health hospital with bars on the windows, prompting the young people to tell me that they did not want to be where ‘crazy’ people stay. While the humanitarian organisations are doing their best to find somewhere adequate for families, they might also create situations that can be perceived as violent by the recipients insofar as the family ultimately decided that sleeping bags on the beach would be better than the accommodation they were given, especially given the connotations of bars on windows and the trauma of their own escape from war in Syria.

In her theorisation of what she terms ‘encounter theory’, Standish argues that ‘Encounter Theory is an engagement of difference (with people, identities or ideas) and a commitment to non-violent appreciation of discord that may arise from such engagements – not the outcome of engagement itself’ (Standish Citation2021: 7). For Standish, then, the processual capacity of encounters shifts the focus to its ongoing nature and while the endpoint is not the significant element, the positive experiences of the encounter is central to mutual understanding. Though there might be disagreements, encounters are fundamentally empowering. By contrast, I would argue that the particularity of what I call the ambivalent encounters in Calais fosters a feeling of being further marginalised in the new arrivals by exacerbating their dislocation and generating anxiety. Thus, the issue faced by Calais’s people on the move is the ‘stuckness’ in which they find themselves due to the ambivalence that is exhibited towards them. The establishment of:

the tent city and encampment are portrayed as spaces where the migrant is denied the capacity to move—a space of stuckness in which access to mobility is entirely decoupled from the subject position of the migrant. Yet when the encampment or tent city takes on the qualities of a stable, autonomous community, resembling a functioning city (thereby making the refugee a de facto resident rather than migrant), it is promptly destroyed by the hegemonic state. (Anam Citation2020: 407)Footnote5

While discussing Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the positioning and ontological identity of refugees, Lyndsey Stonebridge argues that the latter ‘opened up a space – at once historical, political, and imaginative – for thinking and being between nation states’ (Stonebridge Citation2018: 19). I would contend that Calais’s people in transit, amongst whom a large number are given asylum in the UK (23,841 people (including dependants) in 2022 alone, while many are still awaiting decisions (Home Office Citation2023)), have a particular status ‘being between nation states’ and their marginality allows us to envisage what it means to be rejected as human beings who exist in that liminal space ‘between nation states’. France, it would appear, feels justified in not enabling would-be asylum seekers (in the UK) to install themselves for any prolonged period of time since their aim is not to stay. France would give asylum and deliver services for those who wish to stay, but the use of France as a point of departure to the UK gives the French nation-state a reason for not providing them with the basic necessities and for the local authorities to evict them if they begin to establish what looks like a new camp. Both the frequent evictions I outlined in the introduction to this essay and the absence of local authorities’ support are reasons why the ‘camps’ are mobile and change locations regularly, which in turn also impedes the establishment of spaces where charities and local organisations can offer continuous and sustained support, as the representative of the RWC suggests in our interview.

Interestingly, usually camps, ‘As spaces that fall within the remit of humanitarian protection and aid, and outside the national order of things, […] are simultaneously within and outside the law’ (Sanyal Citation2014: 559). In the case of Calais’s unofficial camps, local authorities police them because they are not given recognition as camps, and instead, are perceived as the illegal occupation of public spaces where individuals and families who do not belong, and indeed, do not wish to belong in France, spend a small amount of time until they obtain passage on small boats to the UK. Accordingly, then, Bouchart feels vindicated in asking the local residents to report anyone who is caught illegally occupying a space which is visible to the local residents, as discussed earlier. While Oren Yiftachel (Citation2009) has theorised the existence of ‘gray spaces’ as the transgressive margin between the space of the camp and the space of the host territory, in Calais what we see is that the unofficial camps themselves become ‘gray spaces’ that exist between the UK and France and where the occupiers are denied rights by both nations. Othered by both France and the UK, they experience ‘Living conditions that create feelings of otherness or powerlessness’ and ‘mirror the corporeality of affects, which is intimately connected to the lived environment and position of the individual in the current socio-political context’ (Seppala et al. Citation2019: 94). Indubitably, people who create unofficial camps while waiting to cross over to the UK are left to their own device or to the good graces of humanitarian agencies and charities rather than the nation-states that divest themselves of their responsibility as upholders of human rights.

Everyday Encounters

Upon arrival in Calais, people on the move most often meet humanitarian agency workers and volunteers rather than local authorities. Standish articulates the core sentiment in ‘encounter theory’ as reliant on ‘recognition and appreciation’, ‘creating bonds of understanding and rehumanisation via the encounter of otherness’ (Citation2021: 8). I would argue that the humanitarian agencies and organisations operating in Calais exhibit a deliberately compassionate and voluntarily non-hierarchical interaction with the newly arrived to mitigate the negative reception of the nation-state, thereby establishing themselves as the opposite of the inhospitable nation-state. They do this first of all by focusing on the solidarity, and therefore equality, aspect of their endeavour, rather than the ‘charity’ facet, which by definition involves being in a superior position, and secondly, by not using the word ‘migrant’, instead replacing it with the term ‘exilé/ exile’.

Indeed, l’Auberge des Migrants, and, particularly the warehouse it cites as its main address, already tackles the horizontal nature of its relationship with those who are stopping in Calais on their way to the UK from its very threshold. Home to no less than eight different charities working with those who arrive in Calais (including Human Rights Watch, Refugee Women’s Centre, l’Auberge des Migrants, Project Play, Infobus, Refugee Communal Kitchen and others), the warehouse is used to stock their resources, and serves as a base of operations for the volunteers (see ).

shows the home-made sign at the entrance of the warehouse, which explicitly defines their work not as charity but as solidarity with those who are in need. In casting the work that the different agencies are accomplishing in this space as ‘solidarity, not charity’, I suggest that they are beginning the work of redefining their own encounter with the individuals and families whom they are helping as a compassionate one enabling the weary travellers to feel human and be treated as such again. Secours Catholique also operates on the same basis: their doors are open every afternoon between 13:30 and 17:00 during the week, for the women’s side, and the same hours except on a Tuesday, when it is closed, for the men’s side. Many of those arriving in Calais or who have been there for a while make their way to Secours Catholique’s premises to shower, eat, socialise, and seek help. Other organisations like Care4Calais, provide services in the different camps every afternoon all year round, with mornings used by all to prepare for their afternoon activities. Per my observations, the humanitarian agencies and charity organisations in Calais exhibit traditional hospitality insofar as they extend an open welcome and treat everyone who comes to use their services as human beings rather than as trespassers.

Hospitality has two distinctive aspects according to Emmanuel Levinas: the ethical and the political. Ethically, the self is morally compelled to welcome the stranger into the private space of the home. Politically, the self should welcome the stranger into the public nation-home. These equations rely heavily on the function of the home: ‘the privileged role of the home does not consist in being the end of human activity but in being its condition, and in this sense, its commencement’ (Levinas Citation1961: 152). The home as a space where the welcome is practised and lived is central to the existence and ‘coming to oneself’ of the self (Levinas Citation1961: 156). Thus, for Levinas, the dweller gains their identity through the home and also through the giving of hospitality inside the home. Though Levinas does highlight the woman’s role in creating this hospitable home space and has been criticised for this (Critchley Citation2004), hospitality as reliant on both the self that offers it and the other who receives it is crucial to my understanding of ambivalent encounters here. Indeed, insofar as in French the term ‘hôte’ refers both to the host and to the guest, the interconnections between the two are intricately underlined and symbiotic. On a more concrete and basic level, the humanitarian organisations offering hospitality in Calais welcome the strangers who are here for a short period of time with an open heart, and in doing so, they fulfil the ethical responsibility incumbent on the Levinasian self. Due to the short span of time that people in transit spend in Calais, there is no time or leeway to exert control or work their own agendas into the aid they provide. Since the nation-state and the local authorities evict or hold a negative discourse, humanitarian agencies who work closely to provide basic necessities and treat them well are automatically cast into the ally position, though as I mentioned earlier, there are also times when there are frictions. There is also an ontological aspect to this as these organisations exist by default to welcome and provide services for those who are arriving in Calais. Were there to not be individuals and families crossing to the UK through Calais and Dunkirk, these organisations would also lose their raison d’être. By contrast, the nation-state and the local authorities, realise another political responsibility which is at odds with political hospitality: the necessity to curb the crossings as the UK government has paid them to do, for the former, while also attempting to change the local landscape and the view of Calais as a ‘migrant’ space instead of a city in its own right for the latter. Thus, in the case of Calais, the ethical and political realms of hospitality are at odds and therein partially lies the reason behind the ambivalent encounters that those who are travelling through experience. While the nation dehumanises, the humanitarian response rehumanises and creates the bonds and understanding needed to outweigh the chilly reception they receive from the local authorities. Yet there is also an issue with the fact that each of these see people in transit as passive and having no say in their own perception, in their own humanity, so that their positions of power create further ambivalence for people on the move.

Moreover, it is important to note that the term ‘refugié/ refugee’ is rarely deployed in both cases. This is because the refugee is recognised as such under particular circumstances as defined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. Though many of the people travelling through Calais hail from conflict zones, there are also, of course, some who originate from countries which are currently considered to be safe. For instance, while I was in Calais, there was one young woman from Nepal who was only crossing to the UK to join her brother and his family but she was the only one out of hundreds who came through SC while I was conducting fieldwork. Thus, I would argue that the use of the term ‘migrant’ to identify all those who are crossing through Calais by the local authorities and the nation is deeply problematic as it creates an erroneous perspective wherein all of them are treated as socio-economic illegal ‘migrants’, instead of the refugees that many of them are, as evidenced by the number who are granted asylum as noted earlier. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), thus, also clearly differentiates between the migrant’s liberties and the lack of freedom and protection for refugees. International migrants choose mobility for reasons such as:

pursuing work or education opportunities, or to reunite with family. Migrants in this sense of the word—unlike refugees—continue in principle to enjoy the protection of their own government, even when they are abroad. If they return, they will continue to receive that protection. (UNHCR Citation2023)

UNHCR recommends that —except in very specific contexts (notably statistical: see below)— the word migrant should not be used as a catchall term to refer to refugees or to people who are likely to be in need of international protection, such as asylum-seekers. To do so risks undermining access to the specific legal protections that States are obliged to provide to refugees. (UNHCR Citation2023)

These distinct responses to the individuals and families arriving in Calais are also underlined in the terms deployed by the nation and the humanitarian agencies and organisations. While Bouchart and the local authorities refer to them as ‘migrants’, all the volunteers I encountered during my fieldwork used the term ‘exilés/exiles’ to highlight the fact that the people involved have been wrenched from their homes and are suffering. In the Archaeology of Knowledge, Michel Foucault claims that although

discourses are composed of signs … what they do is more than use these signs to designate things. It is this more that renders them irreducible to the language (langue) and to speech. It is this “more” that we must describe and reveal. (Citation1972 [2002]: 54; emphases in original)

I am equally particularly interested in the equation of the exile with the refugee in Houvenaghel et al.’s definition. For Eva Hoffman, ‘“Exiled” is a strong marker of identity, a handy and rather sexy sobriquet’ (Hoffman Citation2013: 55). Hoffman’s judgement of ‘exiled’ as a ‘sexy sobriquet’ is significant as it underlines the fact that there is a certain degree to which the exiled are romanticised and given a status which is somewhat enviable (at least in the context of Jewish exiles which she focuses on). At its foundation, ‘Exile [is] usually thought of as political circumstances, in which one leaves a nation, or is expelled by the state’ (Hoffman Citation2013: 57), but the ‘exile’ as a figure has been idealised and thus, crucially, Hoffman advocates for the use of ‘migrant literature’ to focus on the lack of bearing and the constant feeling of not belonging that marks work written by those who cannot effectively go home again.Footnote7 While I understand Hoffman’s position, particularly in terms of the romanticisation of the exiled writer, I would argue that the connotations of ‘migrant’ in public and political spheres currently have different valences from the ones that she identifies in her study. In employing the term ‘exilés’ instead of ‘migrants’, humanitarian organisations and charities operating in Calais are effectively reminding us that it is a position occupied by the bereft. Nonetheless, there is a danger that this term, too, becomes reified and begins to have connotations within this setting in the long run. From my observations and interactions with people in transit in Calais, very few understand French, so that whether they are being referred to as ‘migrant’ or ‘exilé’ does not make a difference to them. They are there only briefly and as such this distinction in nomenclature is a choice made by the humanitarian organisations without the input of people on the move, who are ultimately excluded.

This will to change others’ perspectives is also made evident in the Preface to the book published by l’Auberge des Migrants, Le ‘Live’ de la Jungle, which showcases lived experiences of people on the move in Calais and those who work with them, and wherein François Guennoc observes that: ‘dans ces récits il y a la compassion, l’amour, mais aussi la culpabilité vis-à-vis de la façon dont les exilés ont été traités/in these accounts, there is compassion, love, but also guilt for the way the exiled have been treated’ (Auberge des Migrants Citation2021, ‘Preface’). I would suggest that the culpability that the volunteers experience vis-à-vis those whom they welcome is also linked to the ambivalence of the latter’s encounter with the local authorities and the mistreatment they undergo in terms of lack of provision, evictions and so on. Thus, the way that humanitarian workers ethically respond to people in transit, and how they call them, functions as a means of compensating for the lack of care and Levinasian hospitality of the nation-state itself. While the nation-state dehumanises people on the move and casts them as ‘migrants’ and as such, as not worthy of help by virtue of them choosing to leave their country for various reasons (the definition of ‘migrant’ at its core), the humanitarian organisations respect them as human beings and offers them compassion and understanding. Though there is a binary at play since the French nation-state has shifted to a position of repression and rejection, with the humanitarian organisations fitting into the opposite, the latter also create situations of ambivalence. The set up of the humanitarian organisations has been established to cater for basic needs for a limited time, after which they are expected to leave. Thus, while people in transit can find momentary compassion, local authorities, the nation-state and ultimately the humanitarian organisations all work within a system and structure that is transitory such that hospitality is time-limited.

Conclusion

The ambivalent encounters I have examined in this essay enable us to comprehend the complex negotiation of space and belonging for people on the move in Calais. While the French nation demonstrates its commitment to the Refugee Convention by giving asylum to those who seek it in France, it reneges on its responsibility towards those who are focused on reaching the UK, thereby creating inhospitable conditions for them and fostering a hostile environment for those who are seeking temporary refuge. Nonetheless, while people in transit may be caught between opposite affective experiences, it was quite clear that the work undertaken by human rights workers and volunteers does make a difference to their well-being. As an observer, I witnessed the urgency and the humanity of the work accomplished by these individual agencies first-hand, and especially how they work together to ensure that new arrivals’ immediate needs are met. Unlike in the case of the local authorities or that of the nation-state, there are no boundaries of race, nationality, or class. If gender does matter inasmuch as women were separated at the Secours Catholique facilities, it is often to respect the fact that many of the women who are crossing are Muslim and cultural factors are being valued. The vulnerability of women and children in such dire circumstances are also being considered. The humanitarian agencies do as much as they can to cater to, at the very least, their basic needs. Though they may have their own agendas, they create the necessary bonds and moments that permit people on the move to not forget that they are human, no matter how much political discourses would like this fact to be forgotten. Nevertheless, the fact is that the French nation-state’s stance on people on the move, the treatment the latter experience and the work accomplished by the humanitarian organisations exist within the same yin-yang binary, and they each have an agenda: the former to show that they are not encouraging illegal migration, the latter that their activism and their aid work is crucial to people on the move. They are ultimately two sides of the same coin and they need each other to solidify their chosen position in this fraught political discourse, or, dare I say, camp.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ashwiny O. Kistnareddy

Dr. Ashwiny O. Kistnareddy is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Refugee Studies Centre, ODID, University of Oxford. She is also a Sir William Golding Research Fellow at Brasenose College and lectures at Christ Church College, University of Oxford. She has a monograph, Refugee Afterlives: Home, Hauntings and Hunger forthcoming in August 2024.

Notes

1 A chapter on my work specifically on young people’s provisions and charities working closely with them will appear in my forthcoming monograph.

2 Interview conducted 20 April 2023.

3 Interview conducted on 13 April 2023.

4 A recently published study also reveals that the majority of English Channel crossers are fleeing armed violence (Byline Times Citation2023). In fact, ‘well over half the recent migrants come from the top 15 countries globally hit by explosive weaponry’ (Byline Times Citation2023).

5 See also Global Politics Unbound (Citation2023).

6 HRO have maintained a detailed log of the evictions in both Calais and the neighbouring town, Grande Scynthe, since January 2020.

7 See also Mardorossian (Citation2002) who discusses this evolution from the perspective of Caribbean literature, whereas Hoffman’s focus is on Jewish writers in exile.

References

- Agier, M., et al., 2018. La Jungle de Calais. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Ahmed, S., 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London: Routledge.

- Alexander, P.C., 2012. Retraumatization and Revictimization: An Attachment Perspective. In: M. P. Duckworth and V. M. Follette, eds. Retraumatization: Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention, 191–220. Abingdon: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Allport, G.W., 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

- Anam, N., 2020. Encampment as Colonization: Theorizing the Representation of Refugee Spaces. Journal of Narrative Theory, 50 (3), 405–436.

- Anderson, B., 2017. Towards a New Politics of Migration? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40 (9), 1527–1537.

- Anghel, R., and Grierson, J., 2020. Addressing Needs in a Liminal Space: The Citizen Volunteer Experience and Decision-Making in the Unofficial Calais Migrant Camp-Insights for Social Work. European Journal of Social Work, 23 (3), 486–499.

- Ansoni, F., 2020. Deterritorialising the Jungle: Understanding the Calais Camp Through its Reorderings. EPC: Politics and Space, 38 (5), 885–901.

- Auberge des Migrants, 2021. Le “Live” de La Jungle. Rinxent: Editions Mer du Nord.

- Becker, B., 2020. Colonial Legacies in International Aid: Policy Priorities and Actor Constellations. In: C. Schmitt, ed. From Colonialism to International Aid, Global Dynamics of Social Policy, 161–185. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-38200-1_7.

- Bent-Goodley, T.B., 2019. The Necessity of Trauma-Informed Practice in Contemporary Social Work. Social Work, 64 (1), 5–8.

- Bouchart, N. 2022. Migrants: Le coup de colère de la maire de Calais. Available from: https://www.lepoint.fr/politique/migrants-le-coup-de-colere-de-la-maire-de-calais-16-11-2022-2498068_20.php#11 [Accessed 20 April 2023].

- Byline Times. 2023. Majority of English channel migrants fleeing armed violence, Study reveals. Available from: https://bylinetimes.com/2023/06/29/majority-of-english-channel-migrants-fleeing-armed-violence-study-reveals/ [Accessed 29 Jun 2023].

- Care4Calais. 2023. What we do. https://care4calais.org/about-us/what-we-do/ accessed 27 April 2023.

- Critchley, S., 2004. Five Problems in Levinas’s View of Politics and the Sketch of a Solution to Them. Political Theory, 32 (2), 172–185.

- Davies, T., Isakjee, A., and Dhesi, S., 2017. Violent Inaction: The Necropolitical Experience of Refugees in Europe. Antipode, 49 (5), 1263–1284.

- Elle. 2022. Calais: la maire appelle à la délation des migrants. Available from: https://www.elle.fr/Societe/News/Calais-la-maire-appelle-a-la-delation-des-migrants-2616126 [Accessed 21 April 2023].

- Fassin, D., 2005. Compassion and Repression: The Moral Economy of Immigration Policies in France. Cultural Anthropology, 20 (3), 362–387.

- Fassin, D., 2010. Les Nouvelles Frontières de la Société Française. Paris: La Découverte.

- Foucault, M., 1972 [2002]. The Archaeology of Knowledge (Trans: Sheridan A M). London, NY: Routledge.

- Fuchs, A., Dreher, A., and Nunnenkamp, P., 2014. Determinants of Donor Generosity: A Survey of the Aid Budget Literature. World development, 56, 172–199.

- Global Politics Unbound. 2023. On stuckness. Available from: https://globalpoliticsunbound.com/2023/04/07/in-conversation-on-stuckness/ [Accessed 25 Jun 2023].

- Hanappe, C., 2018. De Sangatte à Calais, Habiter les « Jungles ». In: M Agier, ed. La Jungle de Calais. Paris: PUF, 69–107.

- Hoffman, E., 2013. Out of Exile: Some Thoughts on Exile as a Dynamic Condition. European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe, 46 (2), 55–60.

- Home Office. 2023. How many people do we give protection to? 23 February 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-december-2022/how-many-people-do-we-grant-protection-to [Accessed 4 May 2023].

- Houvenaghel, E.H., García Manso, M.L., et al., 2020. Exile and Migration. Romance studies, 38, 63–67.

- Human Rights Observers. 2023. Monthly Observations. Available from: https://humanrightsobservers.org/monthly-observations/ [Accessed 27 April 2023].

- Ivekovic, R., 2004. The Veil in France: Secularism, Nation, Women. Economic and Political Weekly, 39 (11), 1117–1119.

- Katz, I., 2017. Between Bare Life and Everyday Life: Spatialising the New Migrant Camps in Europe. AMPS: Architecture Media Politics Society, 12, 1–21.

- Kistnareddy, A.O., 2021. Migrant Masculinities in Women’s Writing: (in)Hospitality, Community, Vulnerability. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- La Voix du Nord. 2022. Quand Natacha Bouchart accueille des migrant ukrainiens en mairie de Calais. Availabrl from: https://www.lavoixdunord.fr/1146987/article/2022-03-01/calais-quand-natacha-bouchart-accueille-des-migrants-ukrainiens-en-mairie [Accessed 20 Apr 2023].

- Levinas, E., 1961. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, trans. A. Lingus. La Haye: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Macé, M., 2017. Sidérer, considérer: Migrants en France. Paris: Verdier.

- Mardorossian, C., 2002. From Literature of Exile to Migrant Literature. Modern Language Studies, 32 (2), 15–33.

- Martin, D., Minca, C., and Katz, I., 2020. Rethinking the Camp: On Spatial Technologies of Power and Resistance. Progress in Human Geography, 44 (4), 743–768.

- Millner, N., 2011. From “Refugee” to “Migrant” in Calais Solidarity Activism: Re-staging Undocumented Migration for a Future Politics of Asylum. Political Geography, 30, 320–328.

- Nielson, S.P., 2020. Beaches and Muslim Belonging in France: Liberty, Equality, but not the Burkini!. Cultural Geographies, 27 (4), 631–646. doi:10.1177/1474474020918907.

- Noiriel, G., 1988. Le Creuset Français. Histoire de L'immigration (Xixe – xxe Siècle). Paris: Seuil.

- Noiriel, G., 2001. État, Nation et Immigration. Vers une Histoire du Pouvoir. Paris: Belin.

- Noiriel, G., 2007. Immigration, Antisémitisme et Racisme en France (Xixe – xxe Siècle): Discours Publics, Humiliations Privées. Paris: Fayard.

- Paolini, S.J.H., and Rubin, M., 2010. Negative Intergroup Contact Makes Group Memberships Salient: Explaining why Intergroup Conflict Endures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36 (12), 1723–1738.

- Queirolo Palmas, L., 2021. “Now is the Real Jungle!” Institutional Hunting and Migrants’ Survival after the Eviction of the Calais Camp. EPD: Society and Space, 39 (3), 496–513.

- Reinisch, J., 2015. ‘Forever Temporary’: Migrants in Calais, Then and Now. Political Quarterly, 86 (4), 515–522.

- Rosello, M., 2008. Postcolonial Hospitality: The Immigrant as Guest. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Sanyal, R., 2014. Urbanizing Refuge: Interrogating Spaces of Displacement. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (2), 558–572.

- Scheel, S., and Tazzioli, M., 2022. Who is a migrant? Abandoning the Nation-state Point of View in the Study of Migration. Migration Politics, 1 (2), 1–23. https://scipost.org/MigPol.1.1.002/pdf.

- Seppala, T., Nykanen, T., Koikkailanen, S., et al., 2019. In-Between Space/Time: Affective Exceptionality During the “Refugee Crisis” in Northern Finland. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 19, 1–19.

- Sicard, F., 2011. Enfants Issus de L'immigration Maghrébine: Grandir en France. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Simon, P., 2003. France and the Unknown Second Generation: Preliminary Results on Social Mobility. International Migration Review, 37 (4), 1091–1119.

- Standish, K., 2021. Encounter Theory. Peacebuilding, 9 (1), 1–14.

- Steele, W., and Malchiodi, C.A., 2012. Trauma-Informed Practices with Children and Adolescents. London: Routledge.

- Stonebridge, L., 2018. Placeless People: Writing, Rights and Refugees. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- UNHCR. 2023. Migrant. UNHCR glossary of terms. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/glossary/#m [Accessed 22 Jun 2023].

- Wacquant, L., 2008. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge: Polity.

- Weil, P., 1991. Immigration and the Rise of Racism in France: The Contradiction in Mitterand’s Policies. French Politics and Society, 9 (3/4), 82–100.

- Wilson, H.F., 2017. On the Paradox of “Organised” Encounter’. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 38 (6), 606–620.

- Yiftachel, O., 2009. Critical Theory and Gray Space: Mobilization of the Colonized. City, 13 (2/3), 247–263.