ABSTRACT

This article considers what it means to be queer, Chinese and diasporic in white settler-colonial Australian society. Considering the narratives of newly arrived young queer People’s Republic of China’s Chinese immigrants and older queer Chinese second-generation descendants of earlier China-born settler-immigrants, this paper asks specifically how these subjects negotiate the boundary of sexual other of whiteness and racial other of straightness. We interrogate the pernicious binary of the sexual other being white and racial other being straight and explore how queer Chinese migrants negotiate their racialised and queer existence. This article raises important questions on how the subjects’ elaborate display of Chineseness may run the risk of unintentionally reinforcing the very racialising and orientalising frames they seek to reject. We conclude with a call to recognise dominant structures and their impacts and reflect upon our resistance efforts where we do not end up unwittingly reproducing these structures. Instead, we need to consider how we may work to abolish such structures that hurt us all, albeit differently and unequally.

Introduction: What Does It Mean to Be Queer Chinese in Australia?

In a 2013 publication titled, ‘A Queer Comrade in Sydney’ media and cultural studies scholar, Bao Hongwei, wrote an engrossing account of his experiences as a Chinese gay man arriving from the People’s Republic of China to Australia. Through his autoethnography, Bao detailed how he was met with ‘curiosity and compassion’ each time he mentioned he was doing his doctoral research on queer Chinese culture. People were surprised to learn about the presence of gays and lesbians in China and found queerness to be instinctively antithetical to a communist regime, expecting only stories of suffering in ‘a terrible country’ (Citation2013: 134). In the face of these tendentious beliefs, Bao’s tactic was to wilfully disavow his Chineseness when he first arrived in Australia. Over time, however, Bao found that it was precisely because he was Chinese, as well as gay and English-speaking, that he became more interesting to others. Thus Bao made ‘international friends’ easily, more than ‘many of my colleagues from China’, he said. Among Bao’s many friends are Chinese from Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Australia. Once Bao realised that ‘China is not only the People’s Republic of China’ (Citation2013: 137) but may also be connected to diverse Chinese-speaking and non-Chinese-speaking people from various countries, Chineseness felt ‘less restrictive and repressive’ to him. At the end of the piece, Bao arrived at a queer diasporic subjectivity which he described as encompassing ‘joy and pain, liberties, constraints and ambivalences’ (Citation2013:138). Living between cultures can be painful, he acknowledged, but it can also be playful: one can ‘live in as well as out of identities’ and ‘even take pleasure in inhabiting identities without becoming too paranoid about it’ (Citation2013:139). In this narration, Bao provided what might be the first scholarly account of the entanglements of Chineseness and queerness in Australia.

Since Bao’s publication, a small body of scholarship on the Chinese queer diaspora in Australia has emerged. To our knowledge, there have been three PhD theses examining the health and sexual experiences of Chinese diasporic gay men in Sydney (Wong Citation2019), their life course, integration and engagement in Australian communities (Chen Citation2021) and Chinese queer women’s practices of digital intimacy in Australia (Li Citation2021). There are several journal articles on the use of social media and dating apps among young Chinese gay men and women in Australia (Yu & Blain Citation2019; Li & Chen Citation2021; Perez & Wynn Citation2023); an article looking at the transnational movement of queer women from China to Melbourne and other Australian cities (Kam Citation2020) and two others on queer Chinese international students in Australia (Wang & Gorman-Murray Citation2023; Zheng Citation2023). These scholarships clustering from 2019 attest to the phenomenon of queer emigration from China to Australia, contributing to the development of rising same-sex migration from Asia to Australia (Yue Citation2008). The cluster of work studying Australia’s queer Chinese diaspora can thus be situated within the broader literature on queer Asian Australian diasporic studies theorising queer diasporic identities and issues of sexual racisms, stereotypes, belonging and exclusion in the context of a predominantly white Australian gay scene (Caluya Citation2006, Citation2008; Perez Citation2023).

Against the background of existing studies, this paper is inspired by Sydney World Pride 2023 with its tagline being ‘presenting a truly global LGBTQIA + pride festival’. In the festival’s zealousness to celebrate cultural diversity and inclusion amongst global LGBTQIA + communities, we as Asian, ethnic Chinese queer migrants found ourselves suddenly caught up in a whirlwind of invitations to speak at various World Pride public events. Our ‘culturally exotic queerness’ suddenly became hyper visible and highly desired by white queer organisers to signal a global, multicultural dimension of Australian queer landscape. As admitted by Queer Chinese Voices organisers from Western Sydney University’s Institute for Australian and Chinese Arts and Culture and University of Sydney’s China Studies Centre, Queer Chinese Voices was the ‘first forum of its kind’ to profile voices of queer Chinese scholars and communities in celebration of Sydney World Pride. We took the opportunity to consider what it meant to be queer and Chinese in Australia in consideration of emerging and extant literature on Asian Australian queer diasporic studies and specifically, Australia’s queer Chinese diasporas. In focusing on the ‘queer Chinese diaspora’, our intent is not to yoke together heterogeneous individuals from diverse national and ethnic backgrounds. We acknowledge that Chinese diasporas encompass broader communities from other Chinese societies in East Asia and Southeast Asia. This paper, however, focuses on queer Chinese emigrants from mainland People’s Republic of China living in Australia. At the same time, the paper’s discussions do not seek to be generalisable since queer Chinese migrants from mainland China is also a highly diverse group.

The focus on queer PRC Chinese migrants in Australia is particularly significant in the historical and contemporary contexts of volatile Australia–China relations. According to official statistics collected during 2019–2020 on overseas-born Australian populations, China-born migrant-residents take third place after India-born and England-born migrants (ABS Citation2021). Other than the sheer large number of China-born migrant-settlers in Australia, it is worthwhile studying their migration and settlement experiences since the two countries’ fraught relationship has had its ebbs and flows. From British colonial occupation with the importation of Chinese indentured labourers (Lowe Citation2015) to racially biased White Australia Policy’s Immigration Restriction Act (1901–1958) expelling non-white migrants including Chinese migrants (Koleth Citation2010) to the Whitlam Government’s multiculturalism policy in 1973 welcoming non-European immigrants again (Koleth Citation2010) to contemporary contexts of rising China’s economic dominance and ethnonationalism through the Belt and Road Initiative (Kleven Citation2019) and China Dream (Wang Citation2014) to the most recent COVID-19 pandemic related anti-Chinese hate (Kassam & Hsu Citation2021), the two nations have indeed experienced fluctuating periods of tension and cooperation. It is against the backdrop of these historical and contemporary contexts that the paper seeks to understand the entanglements of queerness and Chineseness that newly arrived and earlier queer migrant-settlers of People’s Republic of China-origin in white-majority Australian society have to negotiate. We ask after how they navigate interwoven racialised and queer spaces, and assert a queer existence while being simultaneously impacted by racialisation in their host society and rising ethnonationalism in their home country.

In our earlier work on Southeast Asian queer migration (Quah & Tang Citation2023), our respondents, who have emigrated out of a Southeast Asian country and settled in a ‘Western’, predominantly white country such as Australia, the USA, the UK and Canada, related their isolation in queer spaces that are white and their fear of coming out in multicultural spaces that are straight. In this article, we examine how queer Chinese in Australia negotiate this seemingly rigid binary of queer spaces being too white and multicultural spaces perceived as anti-queer. We find what Jasbir Puar, queer theorist names as this ‘pernicious binary’ particularly generative for our thinking and discussion of what it means to be queer and Chinese in Australia:

This pernicious binary, the sexual other is white, the racial other is straight, … (Puar Citation2017: 6)

Referring to the case of Tyler Clementi’s suicide, Puar (Citation2017) illustrated how cultural discourses following the unfortunate end of the Rutgers University gay student were largely confined within this problematic binary. Tyler Clementi, a young gay Rutgers University undergraduate student committed suicide in 2010. Leading to his death, he was subjected to sex surveillance and cyberbullying by two fellow students of Asian migrant descent. The commentaries on the case were quickly and unsurprisingly framed as Asian homophobia with an inability to see the two Asian American students as anything else other than racialised, conservative, anti-queer non-white Other. The two Asian American students were assumed to be heterosexual and homophobic right away. The reductive portrayal of Asian minority populations as inherently homophobic in cultural narratives widely circulating on various media platforms arguably arose from deep-rooted white supremacist belief in racialised Asian subjects’ cultural inferiority and backwardness. Instead of asking important questions on structural conditions that lead to queer youth suicides, media attention was focused on the racialisation of the two perpetrators and consequently, led to anti-Asian, xenophobic backlash.

Reflecting on Puar’s (Citation2017) observation that the sexual other is always white and the racial other is persistently straight, this paper sets out to investigate if queer Chinese people residing in a predominantly white Australian society are similarly reduced to racialised objects to reinforce white supremacy and their sexuality is consequently rendered invisible and insignificant. While the paper is interested in finding out how queer Chinese people in Australia work out their sexuality in a relatively queer-hospitable society compared to their country of origin, it examines how they deal with and respond to the persistent racialisation they encounter at every turn of their queer existence in Australia. At the same time, this paper asks how the rising dominance of People’s Republic of China and Chinese ethnonationalism impact queer PRC Chinese diaspora’s negotiations of queerness and racialisation, and how the production of their queer and racialised selves in white Australian society in turn could have any bearing on PRC state’s ethnonationalist projects. To address these research questions, this paper considers two broad categories of queer PRC Chinese migrant-settlers – newly arrived, first-generation young queer Chinese immigrants and older, queer, second-generation descendants of earlier Chinese migrant-settlers. For the first group of newly arrived, first-generation young queer Chinese immigrants, this paper examines a specific cultural expression of wearing Hanfu at pride events. For the second group of older, queer, second-generation descendants of earlier Chinese migrant-settlers, this paper narrows its analytical gaze on the William Yang’s Claiming Heritage photography exhibition and his narrative accounts accompanying the photograph exhibits. Using these two sources of empirical data, this paper investigates specifically how the two generations of queer Chinese migrant-settlers within specific contexts negotiate the boundary of the sexual other of whiteness and the racial other of straightness. The discussion of their stories is not meant to be generalisable or representative of these two generations of queer Chinese migrant-settlers since we are cognisant of the vast diversity of queer Chinese migrant communities in Australia. The project is also not intended to be a population demographic study or case study analysis. Nevertheless, this paper makes a modest attempt to provide useful theoretical understandings into the entanglements of queerness, racialisation and ethnonationalism evident in the study’s selected migration stories spanning the two generations of queer Chinese migrant-settlers in Australia.

Stories of Newly Arrived Young Queer Chinese Migrants

It has been well reported that PRC’s central government has been relentless in stamping down LGBTIQA + activism and grassroots support efforts in mainland China over the past years (Chen & Wang Citation2019; Burton-Bradley Citation2021; Ni & Davidson Citation2021). At the Sydney's World Pride festival, a queer PRC Chinese national activist visiting on a tourist’s visa told us that their movement was under Chinese government’s surveillance. They received a text message by a Chinese government official during their Sydney visit ‘inviting’ them to meet for a ‘chat’ upon their return. Another queer Chinese activist also related how they felt compelled to leave China to continue agitating for reforms after their LGBTIQA + community advocacy efforts was shut down.

There has been an existing body of Chinese queer migration scholarship discussing queer Chinese emigration out of China in hope to escape repression, avoid surveillance in the public and private domains and in search for possibilities for fulfilment of sexual citizenship and accumulation of socio-economic and mobility capital (see, e.g. Yue Citation2016; Kam Citation2020; Choi Citation2022). In recent years, prominent and passionate queer activists had their non-profit organisations and activism work clamped down and found their local as well as overseas movements closely monitored by a web of state surveillance mechanisms (Burton-Bradley Citation2021; Ni & Davidson Citation2021). Leaving their homeland and becoming forcibly displaced seem inevitable out of fear of punitive measures including prosecution. There are also ordinary queer Chinese folks with mobility privileges, akin to queer migrants from other countries, who emigrate for more wriggle space to live out their queer existence and couplehood (Bao Citation2013; Yue Citation2016; Kam Citation2020; Choi Citation2022). One may assume that emigration under such conditions where the state denies one’s gender and sexuality variations and deprives one of equal access to sexual citizenship rights will probably lead to the diminishing of one’s national identity and affiliation. On the contrary, what we have observed is a rise of Chineseness in queer Chinese newly arrived and earlier settler migrants. This is perhaps unsurprising as scholars (see, e.g. Brown-Rose Citation2009; Malik Citation2014; May Citation2017) have observed that displaced people and migrants, in the face of unbelonging and othering in their destination country, become nostalgic about their country of origin, national and cultural identities. Nostalgia is then used as a defence and survival mechanism to retain a sense of self and cultural dignity, resist assimilation, fight back against cultural superiority and draw supportive resources from their ethnic communities.

In Ang’s (Citation2022) astute observation of the rise of Chineseness not just locally in China but also amongst Chinese diasporas, Ang argued that the heightening of global anti-Chineseness would only bring about a corresponding intensification of Chinese racialisation and nationalism. In response to China’s growing economic power, the rest of the world though eager to trade, regards its expanding influence with extreme caution and from time to time, retaliates with Sinophobia whenever their livelihood and financial standing are under threat. In line with what Ang (Citation2022) has argued, we observe the rise of self-racialisation and national pride among overseas Chinese migrants including queer Chinese migrants in the context of COVID pandemic related anti-Chinese hate and Sinophobia. It is interesting to observe that while queer Chinese individuals have suffered intense state surveillance, exclusion and multiple forms of debilitations as a result of Chinese government’s anti-homosexuality position, they leaned into their Chineseness as a shield to speak back at Sinophobia and proclaim their pride and nostalgia in their Chinese cultural, racial and national identities. Indeed, their diasporic sensibility gravitating towards the Chinese Communist Party’s active Han-centric racialisaton of Chinese self-identity and current Chinese president, Xi Jinping’s call for overseas Chinese to unite as a common Chinese race is not unique compared to other overseas Chinese migrants (To Citation2014; Chik Citation2021; Ang Citation2022). It is nevertheless surprising to observe from the outside, queer PRC Chinese’s seemingly contradictory negotiations. It is somewhat counterintuitive for queer Chinese to retreat into and increase their attachment and affinity to their Chineseness since PRC state’s ethnonational, heteropatriarchal state ideology that exacted administrative violence on them has forced many to flee for survival and a queer existence. It is these paradoxical ontologies that the study is interested to investigate amongst queer Chinese diasporas.

features a queer Chinese cisgender woman living in Australia dressed in Hanfu. She provided this photograph and an unpublished reflection article and permitted for these materials to be used and cited in the article. For the purpose of protecting her privacy and anonymity, we have, however, chosen to de-identify her. The Hanfu is for her instrumental in negotiating her double marginalisation across the multiple spaces she navigates. In Australia, she started wearing Hanfu to display her cultural pride after enduring years of overt and casual racism. As a Chinese queer person in Australia, her queerness has also been rendered invisible where queer spaces are predominantly white. At the same time, among Chinese communities in Australia and also in China, queerness has not been widely accepted and at times actively persecuted. Wearing Hanfu enabled her to reclaim her connections to Chineseness as a queer person. By wearing Hanfu at queer events and participating actively in local queer Chinese activism in Australia, she also sought to counter Orientalist understandings that Chinese histories, traditions and cultures are inherently anti-homosexuality. As explained in her reflection:

This is particularly important for queer individuals of Chinese descent residing in a predominantly white society, where I am often the only Chinese person among a group of white queer [peers] … Given such context, I have felt a sense of pride and motivation to amplify queer Chinese voices and challenge the Western-centric notion of queerness.

… the decision to wear Hanfu … during the Mardi Gras parade at Sydney World Pride was a conscious and premeditated choice that held personal significance in my journey of cultural reclamation. For a long time, I struggled with my cultural identity, feeling like I was caught between two worlds - too queer to fit into traditional Chinese culture, and too Chinese to be visible in the queer world. However, by embracing and publicly exhibiting Hanfu in queer spaces, I sought to challenge narrow definitions of queerness and Chineseness, while also celebrating my unique identity as a proud queer Chinese person.

To clarify, wearing Hanfu is not a recent phenomenon that has emerged in overseas Chinese diasporic communities. Hanfu movement originated in China in the first decade of the twenty-first century where young Chinese adults wear Han costumes ranging from Tang, Han and Ming dynasties in the spirit of racial nationalism and cultural revitalisation (Law & Qin Citation2022). According to Law and Qin (Citation2022), some Chinese cultural critics (e.g. Zhou Citation2008 and Wang Citation2010) suggest that the widespread young adult movement with more than 6 million members in 2020 (Li & Xiong Citation2021) reflects a deglobalised response towards rapid global and local changes brought forth by globalisation and China’s economic expansions. Wearing Hanfu is a form of protest against moral decline and could be seen as a retreat into ethnonationalism to valorise past histories, cultures and ways of life. In the empirical study Law and Qin (Citation2022) conducted, they seek to clarify that racial overtones, Han chauvinism, attachment to concepts of race and blood lines, othering of Manchurian subjects and concern over Han racial decline are not the most evident, important and prominent discourse in Hanfu movement. Instead, they observe that the movement is more of an expression of cultural and ethnic revitalisation in response to the ‘Mass Other’ – China’s new rich, poor and elderly. In Law and Qin (Citation2022) study, their Hanfu donning young Chinese respondents claimed that their Hanfu movement was more concerned with the decline in societal attitudes and ‘suzhi’ 素质 – moral character, citizenship, values and behaviour rather than contributing to Han identification and othering of Manchurian subjects (Law & Qin Citation2022).

In consideration of queer Chinese migrants donning on Hanfu as a deliberate display of their Chineseness, this paper argues that this is a form of voluntary self-racialising and seeks to examine its implications on white race making. This paper is interested to investigate if such voluntary self-racialising plays into the entrapment of racialisation and othering by the white imperialists. Here, we refer to Cheng’s (Citation2019) conceptualisation of ornamentalism where she theories the yellow woman and her ornamental Asiatic femininity. Cheng (Citation2019) argues the yellow woman is often the ‘ghost in the machine’ left untheorised and neglected in the discussion and critique of Western, white, masculine, agentic, individualistic and modern personhood. In fact, the yellow woman plays an equally important role as the black enslaved body in constructing and sustaining white male personhood. Cheng (Citation2019) brings to our attention ‘a different kind of flesh in the history of race making’ (Citation2019: 3) and uses ornamental personhood to explain the role the yellow woman plays in the making of modern white man personhood. The yellow woman, as Cheng (Citation2019) observes, is ‘encrusted by representations, abstracted and reified’, ‘persistently sexualised yet barred from sexuality, simultaneously made and unmade by the aesthetic project’ and ‘like the proverbial Ming vase, … at once ethereal and base … ’. Cheng (Citation2019) indicates that the yellow woman in her Asiatic femininity, decorative purpose ‘prosthetic humanness’, ‘aesthetic being’ and ornamental personhood speaks to the well-documented, long-standing racialising, sexualising, objectifying and dehumanising of Asian women (Citation2019:16). The latter have been delegated to the category of aesthetic non-living living thing in the making of modern Euro-American masculine personhood (Cheng Citation2019:22). In consideration of Cheng’s (Citation2019) theorisations, this paper suggests that young queer Chinese migrants donning in Hanfu at queer events unknowingly run the risk of conjuring the all too familiar decorative, ornamental personhood the yellow woman has historically and persistently through contemporary times been implicated in the making of Western modern personhood. It is hard not to consider how Chinese queer people in Hanfu parading alongside white modern queer constituents at pride events might reinforce long-standing stereotypes of Asiatic femininity as Oriental exotic, ornamental extravagant like the Japanese geisha and Chinese concubine, and consequently contribute to the construction of Western modern queerhood with their aesthetic ornamental presence. At a global pride event, they join other non-white queer subjects in their traditional clothes to form a perfect box-ticking diversity backdrop accentuating white queer subjects’ capital and privilege. While trying to reconcile the ‘sexual other’ and ‘racial other’ to demonstrate that the sexual other can be non-white and the racial other can be queer, they potentially reinforce their racial othering and the racial dominance of white straight and queer people. As Heinrich (Citation2013) argues, such well-intentioned ‘decolonial’ and ‘China and the West’ binary approaches unfortunately end up strengthening the colonial, imperial and orientalist frames that they seek to resist and critique (Citation2013: 36).

On another dimension, this paper suggests that queer Chinese subjects donning in Hanfu inevitably implicate themselves in self-racialising and hence at a broader level, contribute to Han dominance and marginalisation of Chinese racial minorities in their homeland. Without a doubt, the growing multi-million-member Hanfu movement reflects and at the same time, strengthens the Chinese state’s ethnonationalist agenda to impose an artificial state-constructed Han racial identity on Chinese populations and categorise them into a distinct racial hierarchy of Han dominant race and the other 55 officially recognised ethnic minority groups. In these expressions of Han-ness through the Hanfu movement, how might a local or diasporic participant understand the connections between these seemingly innocuous cultural practices and their complicity in reinforcing racial hierarchy of human lives and uneven distribution of life chances especially when Han-ness is a form of racial privilege earned at the expense of racial minorities’ ongoing subjugation? It appears even when queer Chinese migrants have managed to resist the Chinese government’s queerphobic agendas by escaping their homeland to pursue their queer lives, they would once again find themselves co-opted into the Chinese state’s China Dream – to be wealthy, to be powerful and to be respected (Wang Citation2014). By being part of this Chinese capacitation dream to promote Chinese national, economic and cultural pride albeit located overseas, they potentially implicate themselves in another life-diminishing form of state violence – the state’s racialisation of Chinese populations that place them in a racial capitalist hierarchy distributing life chances unevenly and unequally, affording ‘Han’ racial majority with more power and privileges, and marginalising the already debilitated racial minorities. While the Chinese government views homosexuality as a threat to their heteropatriarchal and ethnonationalist project and their anti-homosexuality stance has steadily driven young queer Chinese out of their motherland, these young queer Chinese diasporas through self-racialisation in the host country turn out to contribute significantly to Chinese government’s nationhood project from afar. Their self-racialisation project, initially meant to be a protective and defensive shield against their host society’s racial subjugation, inevitably strengthens the Chinese government’s ethnonationalism effort in uniting overseas Chinese diasporas. The Chinese central government has been steadfast in its nationhood project through systematically racialising its local and diasporic populations and stirring their sense of Chineseness to garner their support for China’s nationalist agendas, which include anti-European colonialism, anti-Japan invasion and anti-US domination. While the Chinese government has been openly espousing its anti-LGBTIQA + position and policy, ironically, their untapped and significant diasporic resources possibly lie within the queer Chinese migrant communities.

This is neither a critique nor an insistence of a certain way to be queer and Chinese. Like many displaced queer migrants, young queer Chinese migrants toggle between an uneasy but strong affinity with their homeland and heritage and an equally awkward alliance with ‘Western’ queer politics advocating rights recognition, marriage equality and pronoun use. As queer migrants with mobility privileges ourselves, we are compelled to reflect upon our own Chineseness as Singaporean-Chinese who have grown up reaping racial majority privileges oblivious to the racial subordination and violence Singaporean racial minority populations undergo in their everyday life. Our embodied Chineseness and its related racialised power and privileges already automatically implicate us in a racial and class hierarchy that make us complicit in reinforcing structures of inequalities against non-Chinese racial minorities in Singaporean society.

It is important therefore to clarify and emphasise that these reflections are not meant to police boundaries on what it means to be Chinese and queer. They are also not meant to police Chinese queer people’s appearances and dressings. They are however posed to challenge commonplace and generalised ideas of race and racism and encourage self and intra-community reflections on race work while being queer and Chinese. While completely in awe of queer Chinese people’s and communities’ activism efforts, we raise these questions for critical reflections and constructive conversations because we know very well that it is possible to be queer and racist at the same time. We know it well because we have been capitalist subjects in settler-colonial society like Australia and postcolonial society like Singapore reaping material privileges and accumulating mobility capital at the expense of continually dispossessed Indigenous and racial minority populations.

Stories of Second-Generation Queer Chinese Descendants of Earlier Chinese Settlers

More than a decade ago when we were both pursuing our doctoral studies in Sydney, we befriended a China-born PhD candidate and met her mother, Auntie Zhang on her visit to Sydney. One particular encounter with Auntie Zhang left a deep impression on us when she asked, ‘你们回国了吗?’ ‘(have you both returned to your motherland)?’ For a while, we thought she was referring to Singapore, our home country. We found out later in the conversation that by motherland, she was referring to China. We have never perceived China as our motherland and at that time, did not feel any connection with our migrant ancestry. We have primarily identified as ethnic Chinese born and raised in Singapore under the strong influence of Singaporean-Malay, Singaporean-Indian and other Southeast Asian cultures. We are in fact, the product of Singapore’s 1970s and 1980s aggressive nationhood project in establishing her postcolonial independence and carving out her world standing. Quite detached from our grandparents’ migration journeys from China, we, as third-generation foreign-born descendants of Chinese migrants, have very little knowledge of and affiliation with China and the specific localities our grandparents emigrated from. One could therefore imagine our surprise and disorientation when posed with Auntie Zhang’s question if we have returned to our motherland. On hindsight, Auntie Zhang’s question is reflective of the People’s Republic of China government’s decades of propaganda to unite Chinese diasporas around the world reminding them of their Chinese roots, urging them to 回国 (return to motherland) one day and be connected with their ancestral lands (Suryadinata Citation2017; Ang Citation2022).

One of the article’s author, Ee Ling was in fact a recipient of the PRC government’s outreach efforts to cultivate in overseas Chinese diasporas a strong affinity with their Chinese cultural heritage and identity. At the age of 19, Ee Ling was awarded a 1-year scholarship by the Chinese government to study Chinese literature in Beijing. Through Singapore’s Chinese Development Assistance Council (CDAC), part of a state initiative to encourage grassroots, self-help efforts within each ethnic community, the PRC government sponsored three scholarships annually for Singaporean Chinese to study Chinese language or literature in China as part of their cultural development initiatives. CDAC, a non-profit, self-help organisation set up to provide assistance schemes for the ethnic Chinese community, served as the point of contact for the PRC government to disperse the scholarships. The scholarship provided tuition fees, accommodation and stipends without expecting beneficiaries to fulfil any obligation in return. In retrospection, as a third-generation Singapore-born Chinese, Ee Ling has 回国 (return to motherland) under the facilitation of PRC-sponsored scholarship to advance her knowledge in Chinese literature and foster her ties with the ‘motherland’ where her paternal grandfather emigrated from. She also recalled the many Chinese clan meetings she attended with her second-generation migrant Chinese Singaporean father and late paternal grandfather who migrated in 1941 from China, Fujian 福建 province, Anxi 安溪 county, known as the country’s tea capital for producing the famous tea, Iron Goddess 铁观音. She remembered her mother telling her about the remittances her paternal grandfather had made to support family members stuck in struggling post-cultural revolution China. She had no idea that how her Chinese diasporic family and herself have been implicated in an intergenerational 回国 (return to motherland) project.

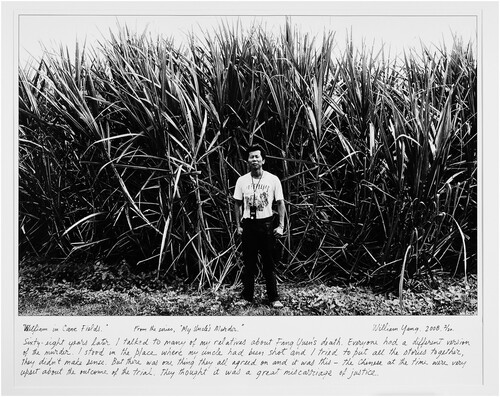

Walking through William Yang’s Claiming Heritage photography exhibition at Western Sydney University (Yang Citation2023), outcomes of the Chinese government’s relentless efforts to recall overseas Chinese and their foreign-born offsprings to return to their Chinese roots could be similarly observed. Even Australia-born second-generation descendants of Chinese migrant families like William Yang, an openly gay man, are not immune to the call to 回国 (return to motherland) since Yang’s photograph exhibits reveal his desire to 寻根(search for his Chinese roots) and journey to his ancestral village in China. Remarkably, Yang’s attachment to his Chinese remains salient despite his parents’ attempt to assimilate the family and gain access to opportunities in white Australian society. According to Yang’s autobiographical narratives, he grew up in a family environment where his father had taken on an Anglicised surname, Young, and his mother had wanted him and his siblings to be more ‘Western’. In his Australian Chinese photography exhibition at National Portrait Gallery, Australia in 2001, Yang’s narratives accompanying his Self-Portrait #1 () reveal:

I was born in North Queensland and grew up denying I was Chinese, with a sense of shame quite close to the surface. Partly because my mother thought being Chinese was a complete liability, a useless thing and she wanted me to assimilate into Australian culture …

Furthermore, Yang recounted alienation from his Chinese heritage when he experienced racial bullying in school at the age of 6. In one of his photograph exhibits, Self-Portrait #2, he narrated being called a derogatory term, ‘Ching Chong China man’ by his schoolmate (Yang Citation2023). He went home to ask his mother, ‘I’m not Chinese, am I?’ When his mother replied, ‘Yes’ in a stern and hard tone, the 6-year-old Yang decided that ‘being Chinese was like a terrible curse’ (Yang Citation2023).

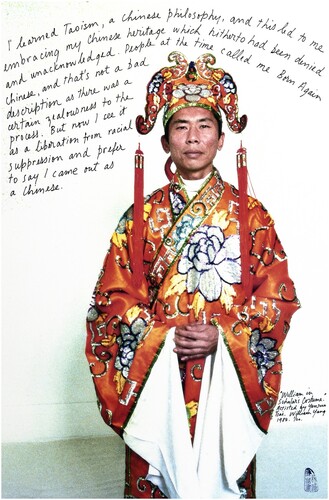

In another photograph exhibit (), Yang explained that he only began to embrace his Chinese identity when he was in his forties after he found Taoism:

I learned Taoism, a Chinese philosophy, and this led to me embracing my Chinese heritage which hitherto had been denied and unacknowledged. People at the time called me Born Again Chinese, and that’s not a bad description as there was a certain zealousness to the process. But now I see it as a liberation from racial suppression and prefer to say I came out as a Chinese.

Yang’s self-acceptance as a Chinese is described both as a rebirth and a self-disclosure, borrowing from the grammar and logic of Euro and US-centric Christian evangelical religiosity like ‘born again’ and normative Western queer discourse of ‘coming out’. Just like how queer people come out as homosexual in a heteronormative society, Yang eventually found courage to come out as Chinese. Coming out is itself a confessional practice with roots in Western Christianity. In this attempt to reclaim a Chinese heritage countering racial suppression by a predominantly white Australian society, a non-white migrant-settler like Yang ironically could only access the language and logic of a dominator culture. Yet, Yang, an openly gay man coming out as Chinese contributes to unsettling the dominant binary of ‘the sexual other is white and racial other is straight’. He shows how the sexual other could be non-white and the racial other could be non-straight.

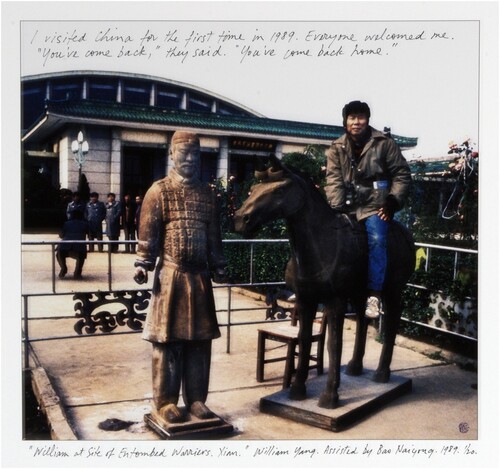

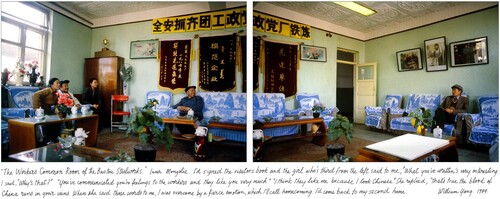

Subsequently, William Yang made a trip to his ancestral land in China. Yang’s coming out as Chinese and his 回国 (return to motherland) add credence to the Chinese government’s global ethnonationalism project recalling overseas Chinese diasporas and their offspring while purporting a homogenous Chinese ancestry and race group. This ethnonationalist state project is not only evident in Auntie Zhang’s question posed to us but could also be observed in Yang’s narratives on the local Chinese’s responses to his 回国 (return to motherland) ( and ):

I visited China for the first time in 1989. Everyone welcomed me. “You’ve come back,” they said. “You’ve come back home”.

I’ve signed the visitors’ book and the girl who’s third from the left said to me, “What you’ve written’s very interesting.” I said, “Why’s that?” “You’ve communicated your feelings to the workers and they like you very much.” “I think they like me because I look Chinese.” She replied, “That’s true. The blood of China runs in your veins.” When she said those words to me, I was overcome by a fierce emotion which I’ll call homecoming. I’d come back to my second home.

Yang saw his visit to China as a form of ‘homecoming’ with an intensity of emotions. Yet this newly-claimed homeland did not birth and nurture Yang. Neither does it celebrate Yang’s sexuality, only his diasporic identity. How is it that older Australia-born queer Chinese second-generation migrant descendants like Yang would develop such nostalgia for a culture and land that chooses to only welcome his Chinese diasporic being, foreign-ness and not his sexual personhood? Yang’s straightforward embrace of these contradictions occurs as Australia–China political relations continue to be volatile (Wade Citation2022) over China’s colonialism projects through its Belt and Road Initiative in Africa and Pacific Islands (Kleven Citation2019), and human rights violations against the Uyghurs and other racial minorities (Human Rights Watch Citation2021) and queer Chinese people (Chen & Wang, Citation2019; Burton-Bradley, Citation2021; Ni & Davidson, Citation2021).

Conclusion

This article is not meant to disparage and police various forms and expressions of queer Chinese diasporic existence in white settler-colonial societies. We acknowledge that queer Chinese migrants like any other migrants do what they need to survive and thrive in their various privilege and marginalisation contexts. What this article aims to bring forth is possible points of consideration where queer Chinese migrants may engage with in their place-making trajectories, settlement strategies and community activism practices.

Our observations show that queer Chinese diasporas like the newly arrived queer Chinese migrants and older queer second-generation Chinese migrant-settlers mentioned in this article, respond to the bifurcating forces of either the racial order or sexual order by attempting to merge and negotiate with both. However, in doing so, they run the risks of reinforcing the Chinese state’s racial capitalist, heteropatriarchal nationhood project. While attempting to resist whiteness and Western imperialism through ‘indigenising’ Chineseness, displaying ‘authentic’ Chinese heritage and coming out and proud as Chinese queer people in white queer spaces, they unknowingly contribute to Chinese state’s ethnonationalist project that involves minoritising and marginalising people categorised as non-Han Chinese. By seeking racial and queer justice in their current diasporic context, they in the end unintentionally implicate themselves in and become complicit with racial injustice projects back in their ancestral lands.

Troubling so, their enhanced display of Chineseness potentially plays into colonial, Western imperialist, racialised and orientalist frameworks in exoticising, othering and subjugating non-Western populations. The dominator’s logic and power remain unchecked despite queer Chinese migrant subjects’ attempts to ‘decolonise’, either by donning the Hanfu or making visits to ancestral lands, in order to reclaim their Chineseness. Furthermore, through these self-racialising tactics, these ‘indigenising’ efforts replicate a multicultural politics of recognition and representation emphasising tolerance, acceptance, inclusion and benevolence on the part of the dominator. By displaying their ‘cultural authenticity’ and using the language and logic of dominator culture such as ‘coming out’, these subjects are co-opted to service the dominant systems’ qualifying criteria for inclusion since the latter always demands subjugated minority subjects to demonstrate their cultural diversity for box-ticking diversity and inclusion exercises.

Ultimately, the rules for domination and oppression remain and minority subjects do not enjoy equitable access to life chances, rights and resources in both white settler-colonial Australian society and Han-Chinese majority society. The important question to consider then is: How may we, as we survive and fight against oppressive structures, not mobilise the very same structures to reinforce other communities’ oppressions and in fact, our own as well? The task is then to recognise dominant structures and their impacts and reflect upon our resistance efforts where we do not end up unwittingly reproducing these structures but instead, work to abolish them.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the de-identified Chinese queer woman for her consent to refer to her unpublished reflection article and both William Yang and her for their permission to reproduce their photographs in this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Quah Ee Ling

Dr Quah Ee Ling is Senior Lecturer in Culture and Society at the Western Sydney University. She is the author of Transnational Divorce: Understanding Intimacies and Inequalities from Singapore (Routledge 2020) and Perspectives on Marital Dissolution: Divorce Biographies in Singapore (Springer 2015).

Shawna Tang

Dr Shawna Tang is Senior Lecturer in Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sydney. She is the author of Postcolonial Lesbian Identities in Singapore (Routledge 2016) and co-editor of Queer Southeast Asia (Routledge 2022).

References

- Ang, I., 2022. On the Perils of Racialised Chineseness: Race, Nation and Entangled Racisms in China and Southeast Asia. Ethnic and racial studies, 45 (4), 757–777.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. Migration, Australia. ABS. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/2019-20 [Accessed 13 February 2024].

- Bao, H., 2013. A Queer ‘Comrade’ in Sydney. Interventions, 15 (1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2013.771012.

- Brown-Rose, J.A., 2009. Critical Nostalgia and Caribbean Migration. New York: Peter Lang.

- Burton-Bradley, R. 2021, October 7. China’s LGBT community caught up in Xi Jinping’s widening crackdowns on big tech, education and celebrities. South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/gender-diversity/article/3151504/chinas-lgbt-community-caught-xi-jinpings [Accessed 9 December 2023].

- Caluya, G., 2006. The (Gay) Scene of Racism: Face, Shame and Gay Asian Males. ACRAWSA e-journal, 2. Available from: http://www.acrawsa.org.au/journal/acrawsa 3-2. pdf [Accessed 7 September 2023].

- Caluya, G., 2008. The Rice Steamer: Race, Desire and Affect1 in Sydney's Gay Scene2. Australian geographer, 39 (3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180802270481.

- Chen, C.X. 2021. Chinese queer migrants in Australia: life course, social integration and community engagement. Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of New South Wales.

- Chen, X., and Wang, W. 2019, October 7. China has a Three No’s policy on homosexuality: No approval, no disapproval and no promotion. Scroll.in. Available from: https://scroll.in/article/939244/china-has-a-three-nos-policy-on-homosexuality-no-approval-no-disapproval-and-no-promotion [Accessed 9 December 2023].

- Cheng, A.A., 2019. Ornamentalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chik, H.M.F., 2021. Negotiating Authorities of Cultural Resource: Recent Scholarly Discussions on the State Ancestor-Worship of the Yellow Emperor. In: C.Y. Hoon, and Y.K Chan, eds. Contesting Chineseness: Ethnicity, Identity and Nation in China and Southeast Asia. Singapore: Springer, 25–40.

- Choi, S.Y., 2022. Global Multiple Migration: Class-Based Mobility Capital of Elite Chinese Gay Men. Sociology, 56 (5), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385211073237.

- Heinrich, A.L., 2013. ‘A Volatile Alliance’ Queer Sinophone Synergies Across Literature, Film, and Culture. In: H Chiang, and AL Heinrich, eds. Queer Sinophone Cultures. London: Routledge, 3–16.

- Human Rights Watch. 2021. ‘Break their lineage, break their roots’: China’s crimes against humanity targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting [Accessed 13 December 2023].

- Kam, L.Y.L., 2020. Coming Out and Going Abroad: The Chuguo Mobility of Queer Women in China. Journal of lesbian studies, 24 (2), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2019.1622932.

- Kassam, N., and Hsu, J. 2021. Being Chinese in Australia: Public opinion in Chinese communities. Lowy Institute. Available from: https://interactives.lowyinstitute.org/features/chinese-communities [Accessed 12 June 2024].

- Kleven, A. 2019. Belt and Road: colonialism with Chinese characteristics. The Lowry Institute. Available from: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/belt-road-colonialism-chinese-characteristics [Accessed 5 February 2024].

- Koleth, E. 2010. Multiculturalism: a review of Australian policy statements and recent debates in Australia and overseas. Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services, Research Paper No. 6. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2010-10/apo-nid22862.pdf [Accessed 16 February 2024].

- Law, A.M., and Qin, Q., 2022. Reflexive Han-Ness, Narratives of Moral Decline, Manchurian Subjects and “Mass” Societal Others: a Study of the Hanfu Movement in the Cities of Beijing, Chengdu, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Xi’an. Journal of current Chinese affairs. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221135082.

- Li, H. 2021. Queer diaspora and digital intimacy: Chinese queer women’s practices for using RELA and HER in Australia. Unpublished PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology.

- Li, H., and Chen, X., 2021. From “Oh, You’re Chinese … ” to “No Bats, thx!”: Racialized Experiences of Australian-Based Chinese Queer Women in the Mobile Dating Context. Social media + society, 7 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211035352.

- Li, X., and Xiong, X. 2021, 18 May. Hanfu costumes gaining tract in China. Global Times. Available from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1223759.shtml [Accessed 29 July 2021].

- Lowe, L., 2015. The Intimacies of Four Corners. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Malik, A., 2014. Remembering Colonial Pasts: Nostalgia, Memory, and the Making of a Diasporan Community. American review of Canadian studies, 44 (3), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2014.939427.

- May, V., 2017. Belonging from Afar: Nostalgia, Time and Memory. The sociological review, 65 (2), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12402.

- Ni, V., and Davidson, H. 2021, July 15. Outrage over shutdown of LGBTQ WeChat accounts in China. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/08/outrage-over-crackdown-on-lgbtq-wechat-accounts-in-china [Accessed 9 December 2023].

- Perez, R., 2023. In the Saunas I’m Either Invisible or Camouflaged: Colonial Fantasies and Imaginations in Sydney’s gay Saunas. Journal of contemporary ethnography, 52 (6), 824–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912416231175866.

- Perez, R., and Wynn, L.L., 2023. The Coloniality of Dating Apps: Racial Affordances and Chinese men Using gay Dating Apps in Sydney. International journal of communication, 17, 5149–5169. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/21068/4286.

- Puar, J., 2017. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity and Disability. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Quah, S.E.L., and Tang, S., 2023. Exploring Southeast Asian Queer Migrant Biographies: Queer Utopia, Capacitations and Debilitations. In: S Tang, and HY Wijaya, eds. Queer Southeast Asia: Itineraries, StopOvers and Delays. London, New York: Routledge, 33–46.

- Suryadinata, L., 2017. The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas. Singapore: ISEAS.

- To, J.J.H., 2014. Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese. Leiden: Brill.

- Wade, G. 2022. Australia-China relations. Parliamentary Library Briefing Book, Parliament of Australia. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook47p/AustraliaChinaRelations [Accessed 13 December 2023].

- Wang, Z., 2014. The Chinese dream: concept and context. Journal of Chinese political science, 19, 1–13.

- Wang, B., and Gorman-Murray, A., 2023. International Students, Intersectionality and Sense of Belonging: a Note on the Experience of Gay Chinese students in Australia. Australian geographer, 54 (2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2023.2174652.

- Wang, J. 王军, 2010. 网络空间下的 “汉服运动”: 族裔认同及其限度 [The “Hanfu movement” in cyberspace: ethnic identity and its limits]. 国际社会科学杂志: 中文版 International social science journal (Chinese edition), 1, 38–45.

- Wong, H. 2019. Chinese diasporic gay men in Australia: Intersectionality, social generations and health. Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of New South Wales.

- Yang, W. 2023. William Yang exhibition: Claiming Heritage. Western Sydney University, Institute for Australian and Chinese Arts and Culture. Available from: https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/iac/exhibitions2/william_yang_claiming_heritage [Accessed 16 June 2024].

- Yu, H., and Blain, H., 2019. Tongzhi on the Move: Digital/Social media and Placemaking Practices among Young Gay Chinese in Australia. Media international Australia, 173 (1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X19837658.

- Yue, A., 2008. Same-sex Migration in Australia: From Interdependency to Intimacy. GLQ: A journal of lesbian and gay studies, 14 (2), 239–262. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/241324.

- Yue, A., 2016. Queer Migration: Going South from China to Australia. In: The Routledge Research Companion to Geographies of Sex and Sexualities. London, New York: Routledge, 213–220. Available from: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.43249781315613000.ch24 [Accessed 09 December 2023].

- Zheng, H., 2023. ‘The Pandemic Helped Me!’ Queer International Students’ Identity Negotiation with Family on Social Media in Immobile Times. International journal of cultural studies, 26 (6), 714–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/13678779221144759.

- Zhou, X. 周星, 2008. 新唐装, 汉服与汉服运动——二十一世纪初叶中国有关 “民族服装” 的新动态 [Han Costume and the Han Costume Movement——the New Development of “Ethnic Clothing” in China at the Beginning of the 21st Century]. 开放时代 [Open times], 3, 125–140.