ABSTRACT

About one third of the Pama-Nyungan languages of Australia employ pronominal cross-referencing, yet systematic typological patterns of non-subject argument registration remain unexamined. We analyze this variation from two perspectives by surveying 22 Pama-Nyungan languages. Firstly, we survey which kinds of case-marked arguments can be cross-referenced by these pronominal systems. From this perspective, we find that a number of nominal expressions marked with so-called ‘local’ cases (e.g. locative, allative, ablative, etc.) can be cross-referenced when instantiating certain argument relations. Secondly, we find striking cross-linguistic predictability in how such relations, which we descriptively group as ‘locational’, are morphologically integrated into the pronominal paradigms. We show that the variation can be captured by two major parameters: firstly, whether locational cross-referencing utilizes the same form as another non-subject series, or whether locational cross-referencing is serviced by a unique series formally built off another non-subject series. In this latter case there is further variation as to which other non-subject series provides the base for the dedicated locational series. These parameters result in six surface pattern types, and we show that each of the patterns is instantiated in languages of the survey.

1. Introduction

About one third of Pama-Nyungan languages exhibit a type of split argument marking referred to as ‘affix-transferring’ by Capell (Citation1972) or ‘double-marking’ by Nichols (Citation1986, p. 75), henceforth ‘DM’. These languages all share pronominal enclitics (also referred to as ‘bound pronouns’) that cross-reference the person, number and some information about the grammatical role of a participant. Bound pronouns are exemplified in (1), a sentence from Warlmanpa (Ngumpin-Yapa). In this clause, the subject argument has two formal realizations: a nominal marked with ergative case, and a bound pronoun =pala which registers a third-person dual subject argument. Like in many DM languages, the nominal is grammatically optional, but the bound pronoun is obligatory under most conditions (see Meakins (Citation2015b) for an analysis of these conditions in two Ngumpin-Yapa languages). The object argument in (1) is not expressed by a free pronoun, but is registered by the bound pronoun =ju.

The languages we are concerned with in this paper are also notable for the fact that the bound pronouns do not strictly appear to cross-reference the case categories evinced in the nominal case-marking system but rather index grammatical relations that need to be established on somewhat independent grounds (Hale, Citation1973; Simpson, Citation1991, p. 101). One reason (amongst others) is that case markers in Australian languages frequently exhibit polysemy between ‘grammatical’ and ‘semantic’ roles (Simpson, Citation2023).Footnote2 A classic example of this is the ergative case which prototypically marks a subject of a transitive clause but also has a ‘semantic-like’ function in marking so-called ‘instrumental’ roles in many Australian languages. In early grammatical descriptions this was treated as a formal case-syncretism; two underlying case categories being expressed by homophonous case forms. However, many other cases exhibit some form of this ‘double-life’. The same kind of functional polysemy underlies various grammarians’ decisions to distinguish between ‘dative’ and ‘purposive’ cases or, of particular relevance to us here, between a (grammatical) ‘accessory’ case and a (semantic) ‘locative’ case as in descriptions of a number of Western Desert and neighbouring languages (e.g. Pintupi: Hansen & Hansen, Citation1978; Walmajarri: Hudson, Citation1978). In DM languages, cross-referencing is typically taken as the primary, if not sole evidence of the distinction: ergative, dative and accessory relations are typically cross-referenced while instrumental, purposive and locative relations are not. Nevertheless, cross-referencing is rarely this regular or straightforward and the distinction between grammatical and semantic roles appears to be more gradient than categorical.Footnote3 As such, there is still little consensus on whether or not these properties truly point towards widespread syncretisms in underlying relational distinctions present in different languages or whether these types of phenomena can adequately be described as predictable types of polyfunctionality of single case categories.

In his seminal work on the grammatical structure of Australian languages, Blake (Citation1987, p. 100) identified that many Australian languages with bound pronouns permit cross-referencing of certain other case relations beyond ‘core’ syntactic categories of A, S and P and the well-known ‘dative’ (sometimes referred to as the ‘oblique’ category). Indeed, as will be illustrated, the grammatical cleft extends further: if this analysis were extended, one would potentially have to innovate further relational labels for the cross-referenced equivalents for locative, ablative, allative, perlative and comitative cases. While our own position would not be aligned with this approach, the objective of this paper is not to advance this debate further.

Instead, we simply follow the trend in more recent descriptive Australianist linguistics in taking the polyfunctional view and readily treating single case markers, like the locative, as having both syntactic and non-syntactic roles (e.g. Mangarla: Agnew, Citation2020, pp. 88–94; Meakins & McConvell, Citation2021, p. 513). Thus we will use a single set of terms for spatial case markers and refer to contexts in which they are cross-referenced as instantiating a ‘locational argument’ while remaining agnostic as to whether there is good, language-specific evidence for proposing additional independent case relations in the relevant language.

Our primary focus in this paper is instead the analysis and comparison of the formal paradigms with which various nominal expressions marked with local cases can be cross-referenced (‘locational arguments’ for short). Our key observation from this survey is that cross-referencing of locational arguments utilizes a series of bound pronouns that are strikingly of just two types: they are either lumped with another series of bound pronouns or are formed via an increment to some other series of bound pronouns. To briefly exemplify, consider (2), two utterances from Nyangumarta. In (2a), a dative-marked participant is cross-referenced with =ji, and in (2b), a locative-marked participant is cross-referenced with =ji: the same form =ji is used for dative and locative arguments.

Initial comparative approaches to bound pronouns have largely focussed on their syntactic properties (Jones, Citation2011, pp. 149–151; McConvell, Citation1980). In this paper, we present an analysis of the paradigmatic relationships between bound pronouns registering non-subject arguments in a survey of DM Pama-Nyungan languages of Australia. First we overview the languages of the survey (§1.1), and introduce how grammatical relations are analyzed in these languages (§1.2), with particular emphasis on the bound pronominal systems. Section 2 analyzes the kinds of spatial case markers that can mark cross-referenced locational arguments. Section 3 analyzes the formal paradigms of locational bound pronouns and their relationship to other series of non-subject bound pronouns. Section 4 discusses the geographic and genetic distributions of the patterns, and Section 5 displays the interaction between bound pronoun registration and reflexivization.

1.1 Languages of the survey

This survey focuses on the Pama-Nyungan languages of Australia which exhibit a type of split argument marking initially referred to as ‘affix-transferring’ by Capell (Citation1972) but perhaps best characterized as ‘DM’ by Nichols (Citation1986, p. 75).

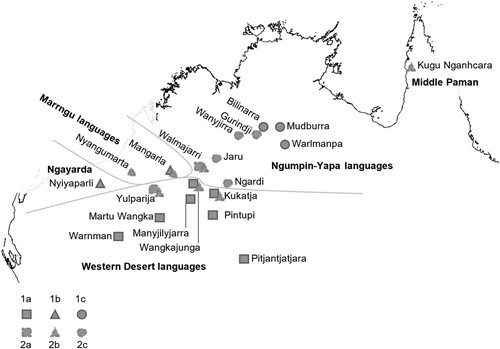

While such languages make up almost a third of the Pama-Nyungan stock, only a fraction of those languages permit cross-referencing of local case-marked referents. Such languages are constrained to languages of the Western Desert and Ngumpin-Yapa subgroups, as well as some neighbouring languages within the Ngayarda and Marrngu subgroups. The only exception to this that we are aware of is that of Kugu Nganhcara, a Middle Paman language spoken on Cape York Peninsula. While we surveyed all languages with some form of DM, no other languages showed clear evidence of cross-referencing of local case-marked arguments.Footnote5 The specific languages surveyed in this paper include:

Marrngu: Mangarla and Nyangumarta

Middle Paman: Kugu Nganhcara

Ngayarda: NyiyaparliFootnote6

Ngumpin-Yapa: Bilinarra, Gurindji, Jaru, Mudburra, Ngardi, Walmajarri, Wanyjirra and Warlmanpa

Western Desert: Kukatja, Manyjilyjarra (and modern day Martu Wangka), Pintupi, Pitjantjatjara, Ngaanyatjarra, Wangkajunga, Warnman, Yankunytjatjara and Yulparija

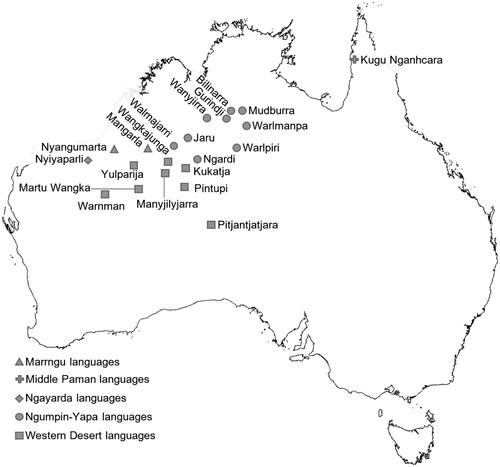

The (approximate) geographical distribution of these languages is given in .

Figure 1. Approximate locations of the Pama-Nyungan languages surveyed in this paper which can cross-reference at least one type of nominal expression marked with local case. (e.g. locative, allative, elative, etc.)

The data for these languages are primarily drawn from grammatical descriptions, except for Ngardi and Kukatja, where supplementary data come from the first author’s fieldwork. The analytical depth of published grammars of all surveyed languages naturally varies somewhat. Because bound pronominals are a core aspect of the grammars of these languages, each grammatical description presents an analysis of the bound pronominal system. However, because the non-core grammatical relations are less well-studied, some grammatical descriptions do not overtly recognize some of the features we discuss in this paper. As such, we explicitly flag the cases where we can infer these features on the basis of the data presented in the description.

Before detailing the bound pronominal systems, we briefly overview other pertinent grammatical aspects of these languages. Broadly speaking, the languages of the survey exhibit free word order (thus often analyzed as non-configurational languages: Hale, Citation1983), as well as null anaphora. The only syntactically obligatory elements of a verbal clause are the predicate and bound pronominals; nominals and other word classes are optional. This is exemplified in (3), a Mangarla clause comprising only a verbal predicate and bound pronouns.

Free word order is demonstrated in (4). In (4a), the subject nominal is clause-final, and in (4b), the subject nominal is clause-initial. Specifically, ‘free’ word order in this context refers to grammatical relations not being the determining factor of constituent order. Word order in most, if not all, of these languages is subject to pragmatic constraints (see Simpson, Citation2007; Simpson & Mushin, Citation2008), in addition to any language-specific syntactic processes that may be present.

Bound pronominals typically occur in ‘second position’ (that is, following the first word or first phrase). Some languages have ‘auxiliary bases’ which either contribute TAM information or otherwise provide a syntactic base for the bound pronouns to encliticize to. In languages lacking auxiliary bases, bound pronouns typically encliticize to an initial ‘phrase’ or ‘constituent’.

1.2 Bound pronouns and grammatical relations

One of the key criteria for determining what the set of ‘grammatical relations’ are among Pama-Nyungan DM languages is the possibility for a case-marked expression to be cross-referenced by a bound pronoun. To exemplify, consider the analysis of grammatical relations in Ngardi (Ngumpin-Yapa), shown in . The primary criteria for identifying grammatical relations in Ngardi are: (a) case marking on nominals; and (b) the pronominal enclitic series used to cross-reference the argument.

Table 1. Grammatical relations of Ngardi (Ennever, Citation2021, p. 502).

In (5), the indirect object ‘dog’ has an overt nominal kunyarr marked with dative case, and is cross-referenced by the oblique series bound pronoun =rla. However, there are (language-specific) conditions on the occurrence of these bound pronouns and nominals within a given clause. As noted earlier, overt nominals are optional, as in (6) where there are no overt nominals. For the pronominal enclitics, generally only animate participants are registered by the bound pronouns (though there are a number of other constraints which vary across the particular languages). In (7), the object ‘two coolamons’ is not cross-referenced, in part because the referent is not animate. As such, the treatment of grammatical relations in these languages utilizes a combination of these criteria, rather than a single criterion. Finally, some languages have further syntactic tests which can be used to independently motivate grammatical relations. These are typically language-specific tests relating to control properties of various types of relativized or subordinate clauses (see, for example Simpson, Citation1991, pp. 314–317 on tests for ‘objecthood’ in Warlpiri).

The number of bound pronominal series varies across languages, however all languages in this survey minimally have a subject and non-subject series (with many languages distinguishing different types of non-subjects, commonly a distinction between an object and a dative/oblique series). The pronominals distinguish person (1, 2, 3), number (typically singular, dual, plural) and clusivity of non-singular first-person referents (for some languages, the system is analyzed as minimal, unit augmented, augmented). An example paradigm, from Western Mudburra (Ngumpin-Yapa) is given in , which demonstrates typical distinctions made in these paradigms.

Table 2. Western Mudburra bound pronominal paradigm (Osgarby, Citation2018, p. 122).

In the Western Mudburra bound pronoun paradigm, there is a primary distinction between subject and non-subject. The grammatical relations subsumed by the ‘non-subject’ series in Mudburra include not just the ‘object’, but indirect objects (marked by dative case); ‘inherent location’ (marked by locative case) and ‘inherent destination’ (marked by allative case) relations (Osgarby, Citation2018, p. 141). The DM languages surveyed in this paper are similar to Mudburra in that they allow cross-referencing of NPs in a select number of local cases (e.g. locative and allative cases) by the bound pronouns. The cross-referencing of the allative case marking of the second singular free pronoun nyuntu in Manyjilyjarra in (8) is illustrative:

The third-person singular in many DM languages is often exceptional within these paradigms. In the case of Mudburra, third-person singular is syncretic between subject and object (being null), while all other non-subjects are marked with =rla. Alternative analyses of this paradigmatic structure in other languages instead posit three series: subject, object and oblique, where the object and oblique series are syncretic in all person/number values except third-person singular (e.g. Ennever, Citation2021).

The constraints on cross-referencing of local cases across DM languages have not previously been the subject of typological analysis, and as such the patterns are not well understood. From the available sources, it is clear that different languages variously limit the number of local cases which may be cross-referenced by bound pronouns (if any); as well as placing various restrictions on cross-referencing generally based on hierarchies of animacy. For example, Nyangumarta only cross-references locative NPs when they are animate, irrespective of the semantic role the NP may be assigned (e.g. accompaniment, goal, source, etc. (Sharp, Citation2004, p. 130)). Variation is observed not only in the number and type of local cases cross-referenced but also with respect to the types of syncretisms that occur within the bound pronouns (i.e. locative bound pronouns being syncretic with object forms, with dative forms, with distinct forms, etc.).

2. Non-subject arguments

We begin by exploring the types of case marking appearing on locational arguments which can be cross-referenced in the surveyed languages. This section lays out the types and competition between cross-referencing of local case-marked arguments in the surveyed Pama-Nyungan languages. Section 2.1 outlines the types of local cases able to be cross-referenced cross-linguistically, and §2.2 surveys language-internal rankings of these cross-referencing patterns.

2.1 Case-marked relations which can be cross-referenced

In this survey, we will not labour on the ergative, absolutive and dative cases, for which the cross-referencing properties are the topic of much existing discussion in the literature, whether in relation to topics of the nature of ‘deep syntax’ (Austin & Bresnan, Citation1996; Hale, Citation1983; Simpson, Citation1983); ‘split ergativity’ (Bittner & Hale, Citation1996; Hale & Keyser, Citation1993; Meakins, Citation2015a); or applicative-like dative relations (Browne, Citation2021b; Simpson, Citation1991). Instead, we will focus on other cases which instantiate non-subject relations, cases typically treated as ‘local’ or ‘semantic’ in nature (Simpson, Citation2023). In this paper, we are exclusively interested in the formal and paradigmatic aspects of how these cases are cross-referenced by bound pronominal paradigms, regardless of the productivity or frequency of the cross-referencing within a given language. Before turning to our analysis, we note that, for reasons of space, this paper does not tackle the fascinating accompanying questions of: (i) which types of predicates select for locational arguments and (ii) what the relationship is between the semantic content of the spatial case and the argument-relating functions it can serve. Sadly, we must leave this topic to future research.

The non-core cases which are identified as being cross-referenced (by some bound pronominal form) in at least one surveyed language include: locative, allative, ablative (or elative), perlative, avoidance and comitative; henceforth grouped as ‘local cases’ for brevity. Note that while we refer to the common case categories in the nominal domain, we generally avoid labelling any series of bound pronoun as strictly marking any one ‘local case’ category, for the reasons outlined in §1.2.Footnote7 We instead use the term locational to refer to a bound pronoun series that may cross-reference nominal expressions in various local cases, and gloss such bound pronoun forms with ‘lct’ (locational). For ease of comparison, we have standardized the source materials to precisely this terminology. As the survey reveals, sometimes the function of the series extends to other ‘core’ grammatical relations (e.g. object). Here we transparently refer to the series via a term which reflects the polyfunctionality, i.e. ‘object/locational’ and gloss it via an appropriate shorthand: o/l.Footnote8

There is significant variation across the surveyed languages as to which local case suffixes can mark locational arguments, as shown in . DM languages excluded from this survey, such as Warlpiri, prohibit the registration of any local cases. A strong tendency found in the survey is that languages which allow cross-referencing of locational arguments permit cross-referencing of those marked with the locative case. Beyond the locative case, Ngardi (Ennever, Citation2021, pp. 508–509), Mudburra (Osgarby, Citation2018, pp. 141–149), Nyangumarta (Sharp, Citation2004, p. 361) and Manyjilyjarra (Burgman, Citation2008, p. 111) all permit locationals marked with the allative. Kukatja permits the allative, the ablative and the perlative (albeit rarely) (Ennever, fieldnotes). Jaru permits the allative and ablative (Tsunoda, Citation1981, pp. 112–117), Mangarla permits the allative, ablative and genitive (Agnew, Citation2020, p. 418), while Wanyjirra permits the allative, ablative and rarely, the comitative (Senge, Citation2015, pp. 315, 318–320).Footnote9 Note that not all languages share the same local case categories presented here (case categories not instantiated in a given language are marked ‘—’ in the table). For those languages lacking a particular nominal case category, the function of that case form is typically subsumed by another local case.Footnote10 The only exception to this hierarchy is Kugu Nganchara, the sole Middle Paman language in this survey. In Kugu Nganchara, the only local case which can mark a cross-referenced nominal expression is the ablative (Smith & Johnson, Citation1985, Citation2000, p. 393).

Table 3. Possibility for cross-referencing of local case-marked NPs in surveyed languages (a dash indicates there is no distinct case form).

From these patterns, we can derive the implicational hierarchy given in (9), which predicts the kinds of nominal phrases marked with local cases which can be cross-referenced in languages of the survey (that is, the ability of a given case to be cross-referenced predicts that all cases higher on the hierarchy can be cross-referenced in a given language).

This case hierarchy can also be extended to the grammatical productivity of these case suffixes: a given case has a more semantically diverse array of functions to those lower on the hierarchy. For example, cross-referenced locatives occur with a greater number of predicates and encode arguments which occupy a semantically more diverse array of functions than cases to the right on the hierarchy.

This phenomenon can be neatly demonstrated in Ngardi (Ennever, Citation2021). The locative case marks the grammatical relation of subjunct, as well as static location, temporal location and mental states, and additionally has a subordinating use. The allative case can mark subjuncts, inanimate goals, changes of state, and has a subordinating use. The ablative marks origin of movement, or reason/cause. Thus there is a clear cline along the hierarchy in which cases become less semantically diverse, becoming more specialized.

2.2 Registration competition

The hierarchy given in (9) predicts the kinds of local cases which can be cross-referenced within a given language. However, within a given language the registration of non-subject relations (including local cases) competes against registration of other non-subject relations (e.g. Hale, Citation1973, pp. 336–337 for Warlpiri). That is, if there are multiple non-subject arguments in a clause, typically only one can be cross-referenced by the bound pronouns (some other factors take precedence, e.g. inanimates are generally not cross-referenced).

For example, in Gurindji, if a (direct) object and indirect object are both present in a clause, only the indirect object can be cross-referenced (Meakins & McConvell, Citation2021, p. 289). This is exemplified in (10) where the object is third-person dual, and the indirect object is second-person singular. In this clause, the only non-subject bound pronoun is =ngku, cross-referencing the indirect object. The object argument ‘two girls’ is unregistered in the pronominal complex.

In this survey we find that animate locational arguments are cross-referenced in preference to object and ‘indirect object’ relations (as observed by Tsunoda, Citation1981, pp. 146–147 for Jaru). Thus we consistently find the following hierarchy across languages regarding which non-subject argument will be registered in the case of competition:

To exemplify, consider the Jaru sentences in (12). In (12a), the first-person free pronoun is an indirect object argument in the dative, and the second-person singular is a locational argument in the locative. The bound pronominal =nggula cross-references the locative case-marked argument, and the dative case-marked indirect object/oblique is not cross-referenced. This is despite indirect object arguments being registered when there are no locational arguments being registered, as in (12b), where the two indirect object arguments are both cross-referenced (two dative arguments can be cross-referenced if one is third-person singular and the other is not).

Similarly, the locative bound pronoun takes precedence over the object bound pronoun in the Ngardi example (13a). Here the first-person singular object is not cross-referenced, since it is blocked by the cross-referencing of the locational argument; in contrast in (13b), the first-person singular object is cross-referenced with =yi since there is no other non-subject pronominal outranking it.

The ordering of this hierarchy is the inverse of Blake’s case hierarchy which predicts the kinds of grammatical relations which can be registered by a language. Where in Blake’s hierarchy, objects outranked obliques which in turn outrank relations encoded by local cases, the language-internal competition hierarchy situates the latter at the top of the hierarchy, with local case-marked relations outranking obliques, which in turn outrank objects, as reiterated in (14)–(15) (recalling that subject bound pronouns are not in competition with non-subject bound pronominals). Unfortunately, there are no clear data on competition between multiple locational arguments within a clause.

3. Patterns of local case referencing

Having introduced the range of local case markers which can mark cross-referenced nominal expressions, we now turn to the paradigmatic relationships between non-subject pronominal enclitics.

In most of the surveyed languages, the various local cases able to be cross-referenced are cross-referenced by the same pronominal series.Footnote13 The variation in patterns of local case cross-referencing can be parameterized along two axes. The first axis relates to whether locational arguments are cross-referenced with bound pronoun forms which are syncretic with or parasitic to another series. By ‘syncretic’, we refer to patterns where the series of bound pronouns used to mark locationals are shared with another series. This is exemplified in (16), where the plural object pronominal in (16a) is =jananya (glossed ‘o’ by Jones), which is the same form used in (16b) (glossed ‘acs’ accessory by Jones), where it cross-references a locative case-marked expression.

By parasitic, we refer to forms within a paradigm which are augmented from or are ‘parasitic upon’ another part of the paradigm (Matthews, Citation1972, Citation1991). The term ‘parasitic’ has previously been primarily invoked in the formal analysis of the inflectional paradigms of verbs, and is relatively widespread in Australia (Koch, Citation2014, p. 158). For example, consider the present and future inflectional forms in the Warburton Ranges variety of Western Desert, shown in . For these verbs, the present inflection form is transparently built off the future inflection form, i.e. the form of the present for these conjugations is fut+la. Morphologically analogous formations in nominal case in Australian languages have typically been referred to as ‘compound case’ (Schweiger, Citation2000) while here we extend the analogy of ‘parasitism’ to bound pronominal forms.Footnote14

Table 4. Sample verbs from the Warburton Ranges variety of Western Desert (data adapted from Koch, Citation2014, p. 155).

The second axis relates to the function of this other (non-locational) series: specifically, whether it is used for cross-referencing ‘objects’, ‘indirect objects’ or a single ‘non-subject’ series. The intersection of these two axes results in six distinct pattern types, each of which is attested by at least one language in the survey, as shown in and discussed in the following subsections.

Table 5. Pattern types of local case cross-referencing in relation to other non-subject series.

Most languages utilize just one of these patterns (that is, most languages in this survey have only zero or one distinct locational series). We now discuss each pattern in turn, before concluding this section with discussion of the languages which each utilize two patterns.

3.1 Pattern 1a: Locational series syncretic with object series

In a number of Western Desert languages, primarily those located in the north of their distribution (Kukatja, Wangkajunga, Manyjilyjarra (and modern day Martu Wangka) and Pintupi), local cases are cross-referenced with the same series which cross-references object relations, as exemplified in the paradigm of Kukatja non-subject bound pronouns shown in . While documentation is scant for Warnman (spoken around Jigalong), examples of locative cross-referencing of this type are also discernible in published materials (Burgman, Citation2003, p. 36).

Table 6. Non-subject bound pronouns in Kukatja (Valiquette, Citation1993, pp. 453–454).

In this paradigm type, unmarked (absolutive) NPs in object functions as well as certain locative NPs (namely those with animate referents) are registered in the bound pronoun by a single set of forms, barring the third singular.Footnote15 For example, the Kukatja first singular bound pronoun =rni can cross-reference absolutive NPs with the role of direct object as in (17a), and absolutive NPs with the role of primary object in a double object construction as in (17b).Footnote16

In (18), the same pronominal form (=rni) cross-references locative arguments with otherwise canonical intransitive (18a), transitive (18b) or ditransitive (18c) predicates.

A sole distinction is to be found in the third singular, shown in (19), where there is a contrast between a zero form =∅ object bound pronoun (19a) and an overt =lu locational bound pronoun (19b).Footnote18

3.2 Pattern 1b: Locational series syncretic with dative series

A second pattern paradigm involves locational bound pronouns which are syncretic with a series dedicated to cross-referencing dative NPs, while object NPs are cross-referenced by a discrete series of bound pronouns. This pattern is found in a number of languages in Western Australia and can be illustrated with the Nyangumarta non-subject paradigm given in . For these languages, the locational and dative arguments are cross-referenced identically for all persons and numbers, except for the third singular where there is a contrast between the two. Other languages exhibiting this pattern of syncretism include the Marrngu languages as well as Nyiyaparli (Battin, Citation2019, p. 18) within the Ngayarda subgroup, a neighbouring subgroup which by and large lacks bound pronouns.

Table 7. Non-subject bound pronouns in Nyangumarta (Marrngu) (Sharp, Citation2004, p. 91). Forms with ‘=’ are phonologically bound to a verbal host, and forms with ‘#’ are phonologically independent pronouns, but still syntactically bound to the post-verbal position.

In Nyangumarta, first-person singular =ji cross-references dative and locative arguments, as in (20a) and (20b) respectively.

Again, a sole distinction is found in the third singular, shown in (21), where datives are cross-referenced with =lu (21a) while locational arguments are cross-referenced with =lV (21b).

The object series is distinct from the dative/locational series, exemplified in (22) where the first-person singular object form is =nyi, as opposed to dative/locational =ji exemplified in (20).

3.3 Pattern 1c: Locational series syncretic with non-subject series

The third type of paradigmatic syncretism involving locational arguments involves local case cross-referencing that is syncretic with both object and oblique (dative) cross-referencing. This is the situation in the Ngumpin-Yapa languages Mudburra and Warlmanpa. In these languages, the bound pronouns essentially distinguish a subject series from a non-subject series, where the non-subject series (typically glossed ‘ns’) cross-references arguments which may appear in three or four different case relations: accusative, dative, locative (and allative or ablative). This is exemplified by the bound pronoun paradigm for Mudburra in . Here again, the 3sg series of bound pronouns provides the exception to the syncretic pattern. For all three languages, the 3sg subject and object are syncretic (with a null form), and other relations are marked with =rla.

Table 8. Non-subject bound pronouns in Mudburra (Osgarby, Citation2018, p. 118)a.

The various functions of these non-subject forms can be exemplified with the Mudburra 2sg=ngku in (23): it can cross-reference locational complements (23a) (Osgarby’s ‘inherent location’); (direct) objects (23b); and benefactive adjuncts (23c).

Bilinarra (a Ngumpin-Yapa language) is tentatively included in this survey, despite not being analyzed by Meakins and Nordlinger (Citation2014) as a language of this type. Meakins and Nordlinger (Citation2014, p. 242) do, however, explicitly identify the possibilities for at least third singular =rla to cross-reference (animate) nominals affixed with ‘spatial case suffixes’ and provide examples of this kind, as shown in (24). Further fully analogous examples of locational cross-referencing involving Pattern 1c can also be identified throughout the grammar (e.g. Meakins & Nordlinger, Citation2014, pp. 232–234).

3.4 Pattern 2a: Locational series parasitic to object series

We now turn to patterns in which the locational series is transparently formed via an increment to another series, constituting a type of parasitic formation (Matthews, Citation1972). In these formations, one series is used as a structural base for another, to which an unanalyzable ‘increment’ is added. The resultant formation is said to be ‘parasitic’ on the base form, which itself is syntactically and semantically inert. To exemplify, consider the non-subject bound pronouns of Yulparija, shown in . In this paradigm, the locative series is formally a sequence of the object series (for the same person/number combination) followed by an increment ra. For example, the first-person singular object form is =ja, and the first-person singular locative form is =jara. Again, however, third singular remains an exception to the overall paradigmatic pattern: in Western Desert languages we typically find a 3sg locational form =lu which diverges from the otherwise consistent pattern.

Table 9. Non-subject bound pronouns in Yulparija (Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, Citation2008).

The examples in (25) illustrate the distinct first singular bound pronoun forms for objects (25a), datives (25b) and locatives (25c), where the locative bound pronoun is formally ‘parasitic’ on the object bound pronoun form.

3.5 Pattern 2b: Locational series parasitic to dative series

Pattern 2b involves the formation of the locational series as a formal increment to a dative series of bound pronouns. Western Desert languages Yulparija, Wangkajunga and Pintupi exhibit bound pronoun series that are parasitic formations on the series. These parasitic series are not a generalized ‘locational’ series, instead they are labelled as ‘ablative’ (Yulparija, Wangkajunga) and ‘avoidance’ (Kukatja, Pintupi) series. An example from Wangkajunga is given in (26), where the third-person plural dative form is janampa, and the third-person plural ‘ablative’ form is janampa + lura.

As noted earlier, these languages provide an exception to our generalization that languages do not distinguish multiple series of locational bound pronouns, since these series operate in addition to a ‘locational’ series of bound pronouns in these languages.

Very curiously, Kugu Nganhcara (Middle Paman) also exhibits Pattern 2b but is something of a geographic and typological outlier. Again, the relevant parasitic series is not a generalized ‘locational’ series (it cannot cross-reference locative NPs) but is dedicated to the cross-referencing of certain ablative case-marked NPs (Smith & Johnson, Citation1985, pp. 103, 108–109; Citation2000, p. 393). Contrast, for example, the use of third singular dative bound pronoun -ngu and the (parasitic) third singular ablative bound pronoun -ngu + rum as illustrated in (27).

Crucially, this is the only ‘locational’ series of bound pronouns in Kugu Nganhcara; there is no other series of bound pronouns which can cross-reference any other types of local case-marked NPs. Thus Kugu Nganhcara is the only language in the survey that is exclusively of Pattern 2b (Kugu Nganhcara). This pattern type is otherwise an additional type to Patterns 1a, 1b or 2a (as summarized in §3.7).

3.6 Pattern 2c: Locational series parasitic to non-subject series

shows a final discrete pattern type which involves a locational series being formed via an increment to a syncretic object/dative series. This is the pattern found in a number of Ngumpin-Yapa languages – namely members in the centre of the subgroup’s areal distribution (Jaru, Ngardi, Wanyjirra and Gurindji). Specifically, a ‘locational’ series is formed via the addition of an increment -rla to a polyfunctional object/dative series. Again, there is a singular exception in the third singular. For third-person singular, three bound pronouns are distinguished: object, dative and locational. Note also that an ‘expected’ compound form *=rlarla is avoided via a process of haplology, typically resulting in the form =rla–nyVnta for these languages. Pattern 2c is illustrated with the Ngardi bound pronoun system shown in .

Table 10. Non-subject bound pronouns in Ngardi (Ennever, Citation2021, pp. 297–298).

Table 11. Two series of bound pronouns for locational case cross-referencing in Wangkajunga (Jones, Citation2011, pp. 140–141).

In Ngardi, the first singular bound pronoun =yi encodes objects, (dative) indirect objects and (dative) possessors, shown in (28a–c) respectively.

In contrast to =yi, the bound pronoun =yirla cannot mark any of the relations in (28) but instead can be used to encode various locational relations, as illustrated with the accompaniment relation in (29).

The locational bound pronoun paradigms in Ngumpin-Yapa languages Jaru, Ngardi, Walmajarri and Gurindji are unique among Pama-Nyungan languages in that they present an additional type of homophony. For these languages, a two-participant sequence of an object/dative bound pronoun followed by the third-person singular dative -rla is homophonous with a single-participant locative argument.Footnote20 This type of homophony is illustrated by the examples presented in (30) involving the same imperative predication ma-nta warlu ‘get/grab wood’. In (30a), a single object/dative pronoun =yi is used, which is either interpreted with benefactive or possessive semantics, i.e. ‘wood for me’, or ‘my wood’. In (30b), a single locational bound pronoun =yirla is used, which is interpreted as an animate source ‘wood from (near) me’. Finally, in (30c), a homophonous but discrete two-member bound pronoun =yi=rla is used. Both pronouns in this complex are necessarily interpreted as dative arguments: the first as a dative possessor ‘my wood’ and the second a dative benefactive =rla ‘for him’.

3.7 Hybrid patterns

In addition to the discrete pattern types identified in §3.1–§3.6, some surveyed languages exhibit multiple series being used to cross-reference locational relations. Mangarla (Marrngu) exhibits a hybrid 1b/2b system; the northern Western Desert languages exhibit hybrid 1a/2b systems; and Walmajarri (Ngumpin-Yapa) exhibits a hybrid 2a/2b pattern. These are now discussed in turn.

Firstly, as noted, Mangarla (Marrngu) exhibits a hybrid pattern, with variation occurring between Patterns 1b and 2b. That is, locational arguments are indexed by a series that is formally linked to the dative series, but there is inter-speaker variation regarding whether that link is one of syncretism (1b) or ‘parasiticism’ (2b). Like Nyangumarta, Mangarla distinguishes an object and a dative series of bound pronouns. In some contexts, select local case-marked arguments are cross-referenced by the dative series of bound pronouns (in which case the bound pronouns are labelled ‘oblique 1’), i.e. conforming to Pattern 1b, as shown in (29a), reglossed as obl/lcti. However, in other contexts, an increment -rla to the obl/lct series can be used to indicate co-reference with NPs in local cases (a series labelled ‘oblique 2’, reglosssed as obl/lctii) as shown in (29b). Note that this latter strategy is structurally identical to how the Western Ngumpin languages Ngardi and Jaru add an increment –rla to their object/dative series in the formation of their locational series (Pattern 2b).Footnote22

In terms of explaining the variation, Agnew provides the hierarchy repeated here in (32), suggesting that the higher ranked roles are more likely to alternate between Patterns 1b and 2b, whereas the lower ranked roles are more likely to only allow Pattern 1b.

Secondly, the northern Western Desert languages possess both a polyfunctional object/locational series (Pattern 1a) which cross-references objects and certain relations in (at least) locative and allative cases; as well as an additional series of bound pronouns which is parasitic on a basic oblique bound pronoun form, and is labelled either ‘ablative’ (Wangkajunga: Jones, Citation2011, p. 141; Yulparija: Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, Citation2008) or ‘avoidance’ (Pintupi: Hansen & Hansen, Citation1978, p. 119; Kukatja: Valiquette, Citation1993, p. 454), i.e. Pattern 2b. Interestingly, in Wangkajunga and Yulparija, the available evidence indicates that these bound pronoun forms do not consistently cross-reference particular cases, as examples of seemingly co-referent ‘dative’ NPs are found, further reinforcing that there isn’t a simple correspondence between a single case relation and pronominal cross-referencing. The forms of the ‘object/locational’ and ‘ablative’ series in Wangkajunga are given in , and illustrated in (33). Notably, all these paradigms fit into the patterns presented in this paper: the ‘locational’ series is syncretic with the object forms (Pattern 1a), and the ‘ablative’ series is parasitic to the indirect object series (Pattern 2b).

Table 12. Non-subject bound pronouns in Walmajarri (Hudson, Citation1978, pp. 60–62).

Lastly, Walmajarri (Ngumpin-Yapa) exhibits an interesting combination of Patterns 2a and 2b, in which the object and dative bound pronoun series are distinct from each other, and both series can serve as the base in the formation of a locational series via a -rla increment, as shown in . Both are observed cross-referencing locative-marked nominal expressions, however the parasitic formation with the object series as the base is reported to be more common (Hudson, Citation1978, p. 63).Footnote24

The variability in selection of locational i or locational ii in the pronominal complex in Walmajarri is illustrated in (34), where (34a–b) exhibit the series incremental to the dative series (s 2b), and (34c–d) exhibit the series incremental to the object series (Pattern 2a). Note that in (34a) and (34c) we have clear evidence of the same case-marked (free) pronoun (ngau-nga) being cross-referenced by bound pronouns from the two different series (lcti and lctii).

To summarize the discussion of hybrid patterns, we demonstrate two main findings: firstly, each hybrid pattern involves Pattern 2b; and secondly, each hybrid pattern demonstrates the same nominal case marking being cross-referenced by different bound pronominal series. We now turn to the distribution of pattern types, which sheds further light on these hybrid patterns.

4. Distribution of pattern types

Having introduced the types of patterns found in the surveyed languages, as well as languages which exhibit hybrid patterns, we now turn to the distribution of the patterns found, which are overviewed in and . These tables are suggestive that there may be a weak genetic component to the distribution of pattern types. Broadly speaking, Ngumpin-Yapa languages exhibit Patterns 1c or 2c; Marrngu 1b; and Western Desert 1a. What is particularly striking, however, is that even within a closely related language grouping there is nevertheless considerable, and structurally diverse, variation. Within Ngumpin-Yapa, for example, only Patterns 1a and 1b are unattested. While a range of patterns is attested for the cross-referencing of locational arguments in the subgroup, it is notable that just one language in Ngumpin-Yapa – Warlpiri – eschews all and any forms of cross-referencing of local case-marked expressions.Footnote25

Table 13. Surveyed languages categorized by pattern type.

Table 14. Surveyed languages categorized into genetic subgroup with corresponding pattern type.

Conversely, the distribution of the use of parasitic formations (i.e. (2a–c)) appears to have a strong areal component; being spread across Western Ngumpin languages and the adjacent northern Western Desert languages (Yulparija, Wangkajunga, Kukatja) and Mangarla (Marrngu). The areal distribution of parasitic formations is clearly seen in , where the parasitic formation, especially 2b, is found at the intersection of the language groups. Notably, 2b is not used exclusively in any surveyed language, and is only found in these hybrid systems at the intersection of language groups. Arguably then, one might hypothesize that it is these parasitic patterns which may have developed more recently and spread areally rather than the syncretic patterns which appear to have a more traceable genetic component. However, further evaluation of the diachrony of these systems must await more careful analysis of the forms involved, taking in a wider view of their possible origins.

5. Reflexivization

In this section, we turn to a final topic pertinent to non-subject pronominal enclitics: reflexivization. For many double-marking Pama-Nyungan languages, there is a specific bound pronoun series used when the object or indirect object is coreferent with the subject, regardless of the person/number of the referent.Footnote26 This bound pronoun is typically referred to as the reflexive, although it is often also used for reciprocal events. The Warlpiri examples in (35) involve objects and (dative) indirect object illustrative of reflexives, both of which use the invariant reflexive enclitic =nyanu.

A less well-known type of reflexivization is found in some Ngumpin languages and the northern Western Desert languages Yulparija. For these languages there is a discrete locational reflexive clitic which must be used if a locational bound pronoun is co-referent with the clausal subject. The form of the locational reflexive/reciprocal is clearly compositional, comprising the simple reflexive and the increment -rla with the variable presence of a linking element -ngku-, shown in . The morphological composition of the reflexive bound pronoun followed by an increment rla is consistent with the formation of locational bound pronouns in each language. For the Ngumpin-Yapa languages, this is Pattern 2c, the addition of an increment to a syncretic object/dative case form. For Yulparija, the locational is an increment to the object form (which is distinct from a dative form), i.e. Pattern 2a. Note that the -ngku- component in the formation of the locational reflexive is widely treated as an ‘epenthetic’ in addition to -rla but its obligatoriness differs across languages (Ennever, Citation2021, p. 309; Meakins & McConvell, Citation2021, p. 355; Senge, Citation2015, p. 330; Tsunoda, Citation1981, p. 152).Examples of the local reflexives are given in (36)–(38).

Table 15. Comparison of object/dative and locational reflexive pronominal forms.

The appearance of body part terms in (36) and (38) are a type of partitive reflexive construction widely found in Australian languages (Gaby, Citation2023).Footnote27 In (37), the reflexive enclitic -nyunungkurla is cross-referencing an unexpressed locative argument of the verb yuwa- ‘put’. What is interesting here is the sensitivity to the local case marking of the (unexpressed) ‘whole’. Partitive reflexive constructions typically involve situations where the body part is situated as the direct object of a transitive predicate rather than as an oblique relation within ditransitive clauses as shown in (36) and (38). This is exemplified in (39), where the direct object takka ‘hand’ is in absolutive case (indicating it is the object of a transitive verb), and the reflexive bound pronominal =nyanu is used to indicate that the object is coreferent with the subject.

When the part appears in the locative we have a situation in which the (typically unexpressed) whole is also in the locative case. While the reflexivization of locative body part terms as illustrated in (36)–(38) may seem somewhat unusual, what we have is actually a consistent pattern in which (for certain languages) locational arguments are available for reflexivization. Malngin (Ngumpin-Yapa) appears unusual in that there is evidence of regular reflexivization when the part appears in the locative:

Walmajarri also represents an interesting case in which locative arguments appear to be able to be reflexivized, but the reflexive form used is the same as that used for dative or absolutive object arguments. Thus compare the unreflexivized and reflexivized non-subject argument of jangku-ma- ‘respond’ in (41).Footnote28 In (38a), the locative complement of jangku-ma- is registered with the locative bound pronoun as it is not coreferent with the subject; and in (38b), the unrealized locative complement is registered with the object/oblique reflexive bound pronoun =nyanu, as the complement is coreferential with the subject.

Outside of the Ngumpin languages discussed above, no other languages surveyed exhibited evidence of locatives triggering reflexivization reflected in bound pronominals. Thus, compare the examples from Mudburra (42), Nyiyaparli (43) and Yankunytjatjara (44), where the locative-marked event participant is coreferential with the subject, but no reflexive bound pronominal is used. Whether locative-triggered reflexivization is restricted to the languages we have identified or whether the pattern extends further but has just been overlooked or is under-represented in the published data remains an open question.

6. Conclusion

It has been nigh on 50 years since Capell (Citation1972) first collated and synthesized the major parameters of typological variation amongst the so-called ‘affix-transferring’ languages within the Pama-Nyungan language family. Despite further influential work by Blake (Citation1987) on case marking and cross-referencing, a clear view of the full paradigmatic possibilities of ‘DM’ languages largely failed to materialize. Thanks in large part to the recent addition of in-depth grammatical descriptions of key languages, this paper goes someway to bringing some of the formal complexities and intricacies of cross-referencing systems in Pama-Nyungan languages into greater clarity.

Specifically, we have provided the first in-depth survey of the paradigms of non-subject bound pronominals in double-marking Pama-Nyungan languages, with a focus on the cross-referencing of locational arguments – that is, the cross-referencing of nominal expressions which are marked with spatial case marking (locative, allative, etc.). Despite being a cross-linguistically uncommon type of cross-referencing (Haspelmath, Citation2013; e.g. Lichtenberk, Citation1997), we found a range of paradigmatic variation in how such relations can be cross-referenced. We explored the design space of this system from two perspectives. Firstly, we considered what kinds of case suffixes can encode cross-referenced locational arguments. Secondly, we considered the paradigmatic relation between types of non-subject bound pronouns, in particular the morphological correspondence between locational bound pronouns and object/oblique bound pronouns.

In terms of the kinds of non-subject relations that can be cross-referenced, we demonstrated that there is a rich array of local cases, with inter-language variation being predictable along an implicational hierarchy. Typically, only one non-subject relation can be cross-referenced within a clause, demonstrating an aspect of grammatical structure in which locational arguments interact with more canonical grammatical relations of object and oblique grammatical relations. In fact, in the languages which allow local case to be cross-referenced, the locational argument is consistently favoured over other non-subject grammatical relations in cases of competition.

We have also highlighted that some languages which privilege select local case-marked terms as ‘arguments’ in the bound pronoun complex can also subject them to the types of syntactic processes typically associated with object or dative arguments. Within the bound pronoun this manifests most clearly in the replacement of ‘locational’ bound pronouns with reflexive bound pronouns when the non-subject term is co-referential with the clausal subject. The presence of both ‘object/dative’ as well as ‘locational’ reflexive forms has generally gone underappreciated in the typological literature on bound pronoun systems.

Now that the strikingly regular occurrence of these locational arguments in DM languages of northern Australia has been demonstrated, we anticipate ample scope for further research into the nature of these locational arguments, their diachronic development and their complex interactions with other grammatical relations.

Ethics approval

The Ngardi data cited in this paper were given ethics approval by the University of Queensland Research Ethics Committee, Approval Number 2018002400. The Kukatja data cited in this paper were given ethics approval by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Project ID 27309.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank, in particular, the Ngardi, Kukatja and Warlmanpa people who shared their languages with us. We would also like to thank the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language for financially supporting our fieldwork. We are grateful to Alan Dench and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on this paper. Of course, any remaining errors are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are either openly available from the referenced resources in the public domain, or available from the corresponding author, TE, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Ennever

Thomas Ennever is a PhD student at Monash University working on the documentation and analysis of Australian Aboriginal languages in collaboration with the Kutjungka people of Balgo, Mulan and Billiluna in Western Australia.

Mitchell Browne

Mitchell Browne is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Macquarie University. His research focuses on the documentation and description of Australian Aboriginal languages, in particular, Warlmanpa, in collaboration with speakers and community members.

Notes

1 The glosses used throughout this paper follow those of the Leipzig Glossing rules <http://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php> with the addition of: ACS accessory; ACT actual; AUG augmented; CAT catalyst; CONT continuous; D/L dative/locative; DUAL dual; DUB dubitative; EU euphonic; EXCL exclusive; F father; FEW few; GRP group; HORT hortative; HYP hypothetical; IMM immediate; IPFVSBJV imperfective subjunctive; IR irrealis; ITER iterative; LCT locational; LINK linker; M mother; MIN minimal; MR1 modal root 1; MR2 modal root 2; NFUT non-future; NPST non-past; NS non-subject; O object; O/L object/locational; PA pa-epenthetic; PAIR pair; POT potential; PRS present; QUES question; REAL realis; RECOG recognitional; REFL reflexive; RR reflexive/reciprocal; S subject; SER serial; SOURCE source; TEMP temporal; UA unit-augmented.

2 The other major reason why bound pronouns clearly don’t index the case categories of the nominal system can be found within the encoding of core grammatical relations. In languages like Warlpiri, for example, the subject series of bound pronouns cross-references ergative and unmarked (absolutive) case-marked subjects while the non-subject series cross-references unmarked objects and various dative case-marked relations (Hale et al., Citation1995, p. 1432).

3 In many instances, animacy clearly plays an obscuring role – higher animates are more likely to be cross-referenced but are also more likely to appear in certain roles (e.g. possessor and benefactive relations); see Blake (Citation1987, p. 38). Languages also vary as to whether various syntactic properties can be used to distinguish grammatical relations (e.g. the ability to control certain types of relative or complementized clauses).

4 Note that while Sharp (Citation2004, p. 250) labels a series of bound pronouns ‘dative/locative’ she only glosses members of this series in examples with ‘d’. We have reglossed such instances as ‘d/l’ to make it clear that such forms are readily able to cross-reference arguments in both dative and locative cases.

5 While this may mean that locational cross-referencing primarily arose in just one contiguous area of Pama-Nyungan, we must acknowledge that, especially in light of locational cross-referencing in Kugu Nganhcara, we may be dealing with an ‘absence of evidence’ rather than clear evidence of its non-occurrence. Certainly, many DM languages spoken in NSW had already undergone more significant degrees of language shift at their time of documentation as compared to other Pama-Nyungan languages spoken in the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

6 Note that the validity of a Ngayarda subgroup has not been clearly established (Dench, Citation1998). We tentatively follow the classification argued in O’Grady and Laughren (Citation1997), in which Nyiyaparli is classified as a Ngayarda language.

7 Some exceptions to this are situations where a series of bound pronouns exclusively cross-reference just a single case (e.g. ‘dative’ in Western Desert languages); in these contexts we follow the source material and will refer to the cross-referencing of ‘dative’ arguments. Note however that there are a range of dative case-marked nominals that aren’t cross-referenced, i.e. there are dative ‘adjuncts’ in these languages too.

8 More specifically, the key reglossings found in the examples in this paper are as follows: Manyjiljarra (Marsh, Citation1976): o > o/l; Nyangumarta (Sharp, Citation2004): d > d/l and 3sg.loc>3sg.lct, Jaru (Tsunoda, Citation1981): loc > lct, Gurindji: o-io > lct. Reglossings of Mangarla and Walmajarri are more complex and are described in the body of the text. Glossings for Mudburra and Ngardi are unchanged. Glossing for Kukatja is the first author’s.

9 Pintupi represents the most extreme instantiation of this generalized ‘spatial oblique’ cross-referencing in which the locative bound pronoun indexes not just locative case-marked NPs but NPs with a full set of additional local case suffixes (labelled “relators” by Hansen and Hansen (Citation1978, pp. 71–89)) which are analyzed as ‘inner suffixes’ to a zero ‘nominative’ case. Such inner suffixes include: -wana ‘along’ (cf. ‘perlative’), -kutu ‘toward’ (cf. ‘allative’) and –tjanu ‘origin’ (cf. ‘ablative’). Hansen and Hansen’s ‘nominative’ case analysis is somewhat supported by the ability for the locative series to cross-reference unmarked nominatives in a range of thematic roles in which local case marking would otherwise be expected. In Hansen’s terms the ‘accessory case’ can sometimes surface ‘in the bound pronoun only’ in apparent case-disagreement with the ‘nominative’ case analysis of the case-marked nominals (Hansen & Hansen, Citation1978, pp. 59–60).

10 For example, in contemporary Warlmanpa, the perlative is extremely rare (Browne, Citation2021a, pp. 129–130), and the typical function of the perlative (‘motion around’) is subsumed by the locative case.

11 We have reglossed the complex predicate here since the source morphemically separates the inflecting verb wung- but leaves it unglossed.

12 Blake’s (Citation1987, p. 101) hierarchy has ‘benefactive etc.’ in the position of our term ‘benefactive/locationals’, which he explains as follows: “benefactive etc. stands for benefactive, comitative (syntactic locatives), and cross-referenced allatives and ablatives (which need labels to distinguish them from their non-cross-referenced counterparts where the two are opposed)”.

13 The only exceptions to this generalization are the northern Western Desert languages which have two non-subject, non-object series of bound pronouns. One series is used for most of the ‘locational’ type arguments described here (and is typically labelled ‘accessory’) while the other appears to be less well-understood. It is variously glossed as an ‘ablative’ series (as for Yulparija and Wangkajunga), or an ‘avoidance’ series (as for Kukatja and Pintupi). While such a case label is a good approximation of the semantics of this series of bound pronouns, rarely do such bound pronouns co-occur with nominals inflected with corresponding case suffixes. In Yulparija, for example, the so-called ‘ablative’ series is in fact only attested ‘co-expressing’ a dative case-marked argument (Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, Citation2008, pp. 26–27). Some additional comments on these bound pronouns in Western Desert languages are made in §3.5 and §3.7.

14 As one reviewer rightly points out, the analogy is imperfect in one respect. The ‘compounding’ of the bound pronoun forms is not fully linearized. That is to say, the ‘increment’ involved in the formation of ‘locational bound pronouns’ is not always directly adjacent to its ‘inert’ host but can appear non-contiguously with it. We hasten to add that this is an even more general property of the pronominal complex. Individual ‘bound pronouns’ can themselves be split up into person and number formatives and rendered non-contiguous under certain conditions in some languages – see McConvell (Citation1980) for details. In the limited Australianist literature on parasitic bound pronouns, the relevant phenomenon has been referred to as involving “non-subject enclitic augmentation” (McConvell & Laughren, Citation2004, p. 161).

15 And, for certain speakers, allative or perlative case-marked NPs.

16 In (17b), the case frame of yuwa- is of the type {erg gives abs, abs}, where both primary and secondary objects appear as unmarked (absolutive) nominals. The primary object (the recipient) is cross-referenced here as an object/locational bound pronoun.

17 Note here that it may appear that =rni is cross-referencing an absolutive object NP since =rni cross-references both locative NPs and absolutive NPs. Indeed, if the elided argument kuka ‘meat’ were to be a nominal that were inalienably possessed, then =rni could be analyzed as cross-referencing an unmarked (absolutive) free pronoun ngayu – i.e. the (inalienable) possessor of an object relation. However, kuka ‘meat’ in Kukatja is an alienable possessum and, as such, a bound pronoun marking the possessor NP ngayu-ku ‘1sg-dat’ would be expected to be the 1sg.dat bound pronoun =tju. Therefore, rather than marking a possessor relation, =rni necessarily marks a source relation ngayu-ngka ‘from me’.

18 In this paper this series of bound pronouns is glossed ‘o/l’ for all person and numbers, with the exception that the third singular =lu is glossed 3sg.l (the zero ‘object’ form is generally not glossed).

19 One reviewer queried the role of the genitive suffix on the free pronoun here. In Mudburra – as in nearby languages (see Browne, Citation2021a, p. 95 for discussion) – the genitive stem is required for locative case suffixation for non-third-person free pronouns (i.e. the locative case cannot attach to the underived root nyunu) (Osgarby, Citation2018, p. 257).

20 Interestingly, this is also parallel to the homophony of the clitic sequence -rla-jinta in Warlpiri, which either marks two separate dative arguments or a single dative argument (with ‘conative’ semantics) (Hale et al., Citation1995, pp. 1438–1439; see Nash, Citation1996, p. 131).

21 Note that benefactive/possessive readings are not morphosyntactically distinguished in Ngardi. Crucially, both readings are still interpreted as requests for wood to be brought, i.e. ‘bring it here’. This is readily distinguished from the meaning of (30c) in which an addressee is directed to take some wood.

22 The ‘obl/lctii’ is also analyzed in some Mangarla clauses as registering additional (generally unexpressed) dative arguments (Agnew, Citation2020, pp. 210–220).

23 The ‘ablative’ bound pronouns in Jones (Citation2011) by and large do not co-occur with overt case-marked NPs. They are found in a range of contexts familiar to the functions of a general ‘locational’ bound pronoun in many of the languages surveyed: i.e. they co-occur with predicates of motion, locution and fear. Unlike the locational bound pronouns, ablative bound pronouns are always interpreted with a meaning of separation (or departure) rather than accompaniment, hence Jones’ use of the term ‘ablative’.

24 As one reviewer rightfully points out, Hudson (Citation1978, pp. 63–66) identifies a number of factors which govern the choice between the two series, which include such constraints as compatibility with other bound pronouns in complex pronominal clusters and propensity for individual series to co-occur with specific predicate-types.

25 Furthermore, while certain (cross-referenced) dative objects can sometimes be replaced with allative marked NPs with the same predicates in Warlpiri, these ‘locational arguments’ never trigger cross-referencing in the bound pronoun (Simpson, Citation1983, p. 154; Citation1991, pp. 324–325). Some ‘apparent’ exceptions are noted by Simpson in a footnote referencing Mary Laughren (Simpson, Citation1991, p. 324, fn. 10), suggesting an avenue for further research.

26 For some other Pama-Nyungan languages, reflexivization is a transitivity-altering process in which all subjects are assigned absolutive case (e.g. Nyangumarta).

27 The registration of the possessor or ‘whole’ in the bound pronoun constitutes what is variously referred to as ‘external possession’ (Payne & Barshi, Citation1999) or ‘possessor raising’/‘possessor ascension’ (Chappell & McGregor, Citation1995).

28 Note that the predicate jangku-ma- in Walmajarri obligatorily takes an addressee in the locative case.

References

- Agnew, B. (2020). The core of Mangarla grammar [PhD dissertation]. The University of Melbourne. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/241927

- Austin, P., & Bresnan, J. (1996). Non-configurationality in Australian Aboriginal languages. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 14(2), 215–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00133684

- Battin, J. (2019). Topics in Nyiyaparli morphosyntax [Honours thesis]. Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.25911/5f4e23a4974d8

- Bittner, M., & Hale, K. L. (1996). Ergativity: Toward a theory of a heterogeneous class. Linguistic Inquiry, 27(4), 531–604. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178953

- Blake, B. J. (1987). Australian Aboriginal grammar. Croom Helm.

- Browne, M. (2021a). A grammatical description of Warlmanpa, a Ngumpin-Yapa language spoken around Tennant Creek (Northern Territory) [PhD dissertation]. University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/d0fcbc2

- Browne, M. (2021b). On the integration of dative adjuncts into event structures in Yapa languages. Languages, 6(136). https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030136

- Burgman, A. (2003). Warnman sketch grammar. Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

- Burgman, A. (2008). Manyjilyjarra sketch grammar. Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

- Burridge, K. (1996). Yulparija sketch grammar. In W. McGregor B (Ed.), Studies in Kimberley languages in honour of Howard Coate (pp. 15–69). Lincom Europa.

- Capell, A. (1972). The Affix-Transferring Languages of Australia, 10(87), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1972.10.87.5

- Chappell, H., & McGregor, W.B. (Eds.) (1995). The grammar of inalienability: A typological perspective on body part terms and the part-whole relation (Vol. 14). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Dench, A. (1998). What is a Ngayarta language? A reply to O’Grady and Laughren. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 18(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268609808599560

- Ennever, T. (2021). A grammar of Ngardi: As spoken. In F. Tjama, M. Yinjuru Bumblebee, D. Mungkirna Rockman, P. Yalurrngali Rockman, Y. Nampijin, D. Yujuyu Nampijin, M. Mandigalli, K. Padoon, P. P. Napangardi, P. Lee, N. Japaljarri, M. Moora, M. Mudgedell, & P. Smith (Eds.), A grammar of Ngardi (pp. 764). De Gruyter Mouton. https://www.degruyter.com/document/isbn/9783110752434/html.

- Gaby, A. (2023). Reflexives and reciprocals. In C. Bowern (Ed.), The Oxford guide to Australian languages (pp. 360–377). Oxford University Press.

- Goddard, C. (1985). A grammar of Yankunytjatjara. Institute for Aboriginal Development.

- Hale, K. L. (1973). Person marking in Walbiri. In S. Anderson, & P. Kiparsky (Eds.), Festschrift for Morris Halle (pp. 308–344). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Hale, K. L. (1983). Warlpiri and the grammar of non-configurational languages. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 1(1), 5–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00210374

- Hale, K. L., & Keyser, S. J. (1993). On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. The view from building 20. MIT: A Festschrift for Sylvain Bromberger, 53–108.

- Hale, K. L., Laughren, M., & Simpson, J. H. (1995). Warlpiri. In J. von Stechow J, J. Jacobs, W. Sternefeld, & T. Venneman (Eds.), Syntax. An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 1430–1451). Walter de Gruyter.

- Hansen, K. C., & Hansen, L. E. (1978). The core of Pintupi grammar. Institute for Aboriginal Development.

- Haspelmath, M. (2013). Argument indexing: A conceptual framework for the syntactic status of bound person forms. In D. Bakker, & M. Haspelmath (Eds.), Languages across boundaries: Studies in memory of Anna Siewierska (pp. 197–226). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Hudson, J. (1978). The core of Walmatjari grammar. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Ise, M. (1999). Grammatical sketch of the Malngin language [Master of Arts]. Hokkaido University.

- Jones, B. (2011). A grammar of Wangkajunga: A language of the Great Sandy Desert of North Western Australia. Pacific Linguistics.

- Koch, H. (2014). The reconstruction of inflectional classes in morphology. In R. Pensalfini, M. Turpin, & D. Guillemin (Eds.), Language description informed by theory (Vol. 147, pp. 153–190). John Benjamins.

- Lichtenberk, F. (1997). Head-marking and objecthood. In J. L. Bybee, J. Haiman, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), Essays on language function and language type, dedicated to T. Givón (pp. 301–322). Benjamins.

- Marsh, J. L. (1976). The grammar of Mantjiltjara [MA thesis]. Arizona State University.

- Matthews, P. (1972). Inflectional morphology: A theoretical study based on aspects of latin verb conjugation. Cambridge University Press.

- Matthews, P. (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- McConvell, P. (1980). Hierarchical variation in pronominal clitic attachment in the eastern Ngumbin languages. In B. Rigsby, & P. Sutton (Eds.), Papers in Australian Linguistics No 13: contributions to Australian linguistics, (pp. 31–117). Pacific Linguistics.

- McConvell, P. (1996). Gurindji grammar [Unpublished manuscript].

- McConvell, P., & Laughren, M. (2004). The Ngumpin-Yapa subgroup. In C. Bowern, & H. Koch (Eds.), Australian languages: Classification and the comparative method (Vol. 249, pp. 169–196). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Meakins, F. (2015a). From absolutely optional to only nominally ergative: The life cycle of the Gurindji ergative suffix. In F. Gardani, P. Arkadiev, & N. Amiridze (Eds.), Borrowed morphology (pp. 189–218). De Gruyter. http://www.degruyter.com/view/books/9781614513209/9781614513209.189/9781614513209.189.xml.

- Meakins, F. (2015b). Not obligatory: Bound pronoun variation in Gurindji and Bilinarra. Asia-Pacific Language Variation, 1(2), 128–162. https://doi.org/10.1075/aplv.1.2.02mea

- Meakins, F., & McConvell, P. (2021). A grammar of Gurindji: As spoken. In V. Wadrill, R. Wavehill, D. Danbayarri, B. Wavehill, T. D. Ngarnjal, L. J. Kijngayarri, B. Ryan, P. Nyurrmiari, & B. Bulngari (Eds.), A grammar of Gurindji (pp. 660). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110746884

- Meakins, F., & Nordlinger, R. (2014). A grammar of Bilinarra: An Australian Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory: Vol. 640. De Gruyter Mouton.

- Nash, D. (1996). Pronominal clitic variation in the Yapa languages. In W. McGregor B (Ed.), Studies in Kimberley languages in honour of Howard Coate (pp. 117–138). Lincom Europa.

- Nichols, J. (1986). Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language, 62(1), 56–119. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1986.0014

- O’Grady, G., & Laughren, M. (1997). Palyku is a Ngayarta language. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 17(2), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268609708599549

- Osgarby, D. (2018). Verbal morphology and syntax of Mudburra: An Australian Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory [MPhil]. University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.14264/uql.2019.96

- Payne, D. L., & Barshi, I. (1999). External possession: What, where, how and why. In D. L. Payne, & I. Barshi (Eds.), External possession (pp. 3–31). John Benjamins.

- Richards, E., & Hudson, J. (2012). Interactive Walmajarri–English dictionary: With English–Walmajarri finderlist (2nd ed.). Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL).

- Schweiger, F. (2000). Compound case markers in Australian languages. Oceanic Linguistics, 39(2), 256–284. https://doi.org/10.1353/ol.2000.0022

- Senge, C. (2015). A grammar of Wanyjirra, a language of northern Australia [PhD dissertation]. Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.25911/5d77867908aac

- Sharp, J. (2004). Nyangumarta: A language of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Pacific Linguistics.

- Simpson, J. H. (1983). Aspects of Warlpiri morphology and syntax [PhD dissertation]. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/15468

- Simpson, J. H. (1991). Warlpiri morpho-syntax: A lexicalist approach (Vol. 23). Kluwer Academic.

- Simpson, J. H. (2007). Expressing pragmatic constraints on word order in Warlpiri. In A. Zaenen, J. H. Simpson, T. H. King, J. Grimshaw, & J. Maling (Eds.), Architectures, rules, and preferences; variations on themes by Joan W. Bresnan (pp. 403–427). CSLI Publications.

- Simpson, J. H. (2023). Semantic case. In C. Bowern (Ed.), The Oxford guide to Australian languages (pp. 226–242). Oxford University Press.

- Simpson, J. H., & Mushin, I. (2008). Clause-initial position in four Australian languages. In I. Mushin, & B. Baker (Eds.), Discourse and grammar in Australian languages (pp. 25–57). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Smith, I., & Johnson, S. (1985). The syntax of clitic cross-referencing pronouns in Kugu Nganhcara. Anthropological Linguistics, 27(1), 102–111.

- Smith, I., & Johnson, S. (2000). Kugu Nganhcara. In R. M. W. Dixon (Ed.), Handbook of Australian languages, (pp. 357–489). Australian National University Press.

- Tsunoda, T. (1981). The Djaru language of Kimberley, Western Australia. Pacific Linguistics.

- Valiquette, H. (1993). A basic Kukatja to English dictionary. Luurnpa Catholic School.

- Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre. (2008). Yulparija sketch grammar. Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

- Willis, D. (2010). Not just Any Old auxiliary! The semantics and pragmatics of Walmajarri’s clitic system [Honours thesis]. University of Queensland.