Abstract

In British India in 1943, a rapidly escalating Allied coal crisis resulted in the lifting of a six-year-old ban on women’s employment underground. Over 70,000 low-caste and adivasi (indigenous) women, battling the war-induced Bengal Famine, sustained production levels and prevented the monthly loss of 385,000 tons of coal between August 1943 and February 1946. Their employment sparked unprecedented outrage among the public, in the press, and in parliaments, generating a transnational discourse on Indian women workers for the very first time. Meanwhile the desperate colonial government disciplined miners through the threat of starvation, information that has so far remained concealed.

In mid-1943 India was highly charged politically just a year after the launch of the Quit India movement by the Indian National Congress, which had refused to support the British Second World War effort without consultation by the colonial government, while the Bengal Famine ravaged eastern India. South Asian studies of the 1940s have only recently begun to move away from elite-level politics, and labour historians have skipped the period altogether. Wartime and its mobilisation of manpower and materialFootnote1 are still mostly framed as a western story, although, over the last two decades, the role of empire has increasingly been emphasised.Footnote2 Gendered histories of wartime have largely focused on metropolitan women’s negotiations of the patriarchy. Ironically, considering the global context, the transnational links of empire have been ignored, as have the imperial patriarchies, femininities, and masculinities they generated. This article investigates a material crisis in a gendered imperial setting. As an Allied coal crisis rapidly intensified, the famous ‘Bevin Boys’ were conscripted to British coal mines in 1943. That same year, half a world away, in an episode now forgotten to history, Indian women too went beneath the surface to mine coal. In August 1943, the colonial government in India reversed a highly controversial regulation that had come into force barely six years previously – the prohibition of women’s work underground. Using official correspondence, parliamentary papers, statistics, newspapers, and letters, this article seeks to reconstruct this story of peripheralised women in a transnational moment.Footnote3

In early twentieth-century India, some 60,000 women worked in coal mines, which, after tea plantations, were the largest employers of women in the subcontinent. In 1937, after nearly half a century of debate, the colonial state expelled 40,000 women from underground work in perhaps the most significant protective labour legislation it would ever undertake. By 1943, an Indian economy strained by the demands of the Second World War was rapidly running out of coal. Few options remained but bringing women back into underground work in mines. In London, on Christmas Eve, civil servant Aubrey Dibdin scribbled in the margins of a file lying with the Economic and Overseas Department (E&O): ‘I should read this measure as an indication that the British Indian machine is coming unstuck’.Footnote4 Nearly all industrialised countries had either never had women working underground or had legislated against it, as Britain did in 1842. India was one of only two known countries (the other being Japan) where women worked below ground.Footnote5 Debates on its prohibition raged in parliaments, boardrooms, and newspapers, but least of all in mines themselves. Illiterate and marginalised by their gender and social status, India’s mining women were rendered doubly voiceless – they were women beneath the surface, literally and metaphorically. A majority were low-caste or adivasi. The term ‘adivasi’, meaning ‘original inhabitants’, came into use in the 1930s for indigenous South Asian communities distinct from caste Hindu society.Footnote6 They were problematically constructed as ‘aboriginal’ by the colonial government,Footnote7 and bore the brunt of aggressive forest and settlement policies.Footnote8 In early twentieth-century Bengal and Bihar, where 90 per cent of India’s coal was produced, women worked underground and on the surface in quarries. Mechanisation was low, so mines depended on manual labourers, more than a third of whom were women paid much lower wages than men. Since coalmining wages were among the lowest across Indian industries, the female breadwinning wage was critical. Male coal-cutters worked alongside female loaders, their wives or women to whom they were occupationally attached, who carried the coal to the surface. In a precarious labour market where most were agriculturalists who mined seasonally, women were a crucial reserve of cheaper-than-usual labour that allowed mine-owners to resist mechanising their operations.Footnote9

A discursive shift towards seeing women’s bodies as needing protection in the early twentieth century coincided with the formation of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1919 and a Labour government in Britain in 1924, creating transnational pressures on the Indian colonial government to enact protective legislation. For parliaments and the press, the mining woman embodied the exaggerated adverse effects of industrial working spaces on women’s birthing, mothering, and domestic practices:

It is entirely wrong that the mothers should have to spend their child-bearing periods in underground sunless, comparatively airless and hazardous conditions. The result has already shown itself to be a very lowered birth-rate and unhealthy womanhood and a stunted offspring. It is against all Indian traditions that motherhood should be submitted to such western, commercialised victimisation.Footnote10

Mine-owners reported astronomically high profits while accident and mortality rates rose constantly. In the House of Commons and the Legislative Assembly, labour leaders emphasised the miners’ desperate poverty:

I have been in the mine-fields, and found more destitution there than probably exists in any other centre in India. I saw women and children going about with bare rags on their backs … such utter misery and destitution … Everywhere you go in the mine-field you meet the spectre of poverty.Footnote11

Much of the rhetoric mirrored that in Britain when similar legislation was enacted in 1842.Footnote12 In India, British and Indian mine-owners initially strongly resisted any prohibition because without women workers, they would be forced to invest in labour-saving machinery. The former had larger mines conducive to mechanisation and could afford the capital investment, while the smaller Indian-owned mines could not and were heavily dependent on cheap female labour. As impetus for legislation grew, British capital recognised an opportunity to outdo their Indian competitors and mechanised operations beneath the surface. In 1928 they reversed their anti-regulatory stance to begin supporting the prohibition of women’s work underground – to the great distress of Indian capital.

For a colonial government notorious for its abuses and inhuman treatment, embracing this ‘progressive’ ideal drawn from western elite discourses around humanitarianism and gender roles became a way to earn plaudits on a global stage through its leading role in authoring the ILO Underground Work (Women) Convention. When prohibition was enforced in 1937 it was disruptive, dehumanising, and anything but humanitarian, excluding 40,000 women from the workforce, jeopardising single women’s survival, drastically lowering family incomes by over one-third, and allowing state and capital to skirt the question of improving mining conditions. The women were offered no rehabilitation, and given the isolation of mining settlements, few alternative sources of livelihood were available.Footnote13

Women resume work underground

The Second World War brought massive demands on India’s resources.Footnote14 In 1943, the colonial government had promised 25.5 million tons of coal to the British imperial war effort – ‘a larger quantity than has ever been made available before’.Footnote15 In December 1943, News Chronicle reported an estimated shortage of six million tons, primarily due to the drifting away of labour to better-paid work in war factories and military projects. The shortage threatened the operation of several industries in India that were keeping the Allied war effort afloat. The government was forced to introduce rationing and fine industries that exceeded their allotted coal quotas. Many industries switched to wood. Jute mills had been shut for a fortnight,Footnote16 threatening their contribution to the manufacture of parachutes, drums, and aerodrome runways.Footnote17 Electricity production had fallen. Railway coal stocks were adequate only for 15.7 days, when the safety level for a country that size was 30 days. Coal allocations were cut by 5 per cent to every industry, and by nearly 20 per cent to steel. To compound problems, industries located far from the coalfields suffered because the railways were running short and could not make the journeys necessary to fulfil demand. In Lahore, saw mills had to stop manufacturing military trucks; in Ishapore, 3.7 Howitzer production was interrupted, and in Madras, parachute cloth manufacture could continue only by borrowing coal from the bunker supply.Footnote18 To make matters worse, British and Indian mine-owners were adopting a ‘dog-in-the-manger attitude’ to keep production low because of the state-imposed excess profits duty.Footnote19

In crisis, the Indian government had suspended prohibition in the Central Provinces in August, in Bengal and Bihar in November, and in Orissa in December.Footnote20 The British Labour Ministry and the Foreign Office, anticipating backlash for the precedent this set for the neglect of international obligations, were most disturbed. Yet so serious was the coal crisis and so crucial to the war effort that the E&O decided it would not disapprove but ‘it would be well not specifically to approve it’.Footnote21 Secretary of State for India and Burma, Leo Amery, sent a strongly-worded telegram to Delhi reminding them that the ILO would have to be informed: ‘You might consider giving public recognition in some way to fact [sic] that such a retrograde measure could not be justifiable except under imperative necessities of war’.Footnote22Agents were charged with recruiting 40,000 women.Footnote23 By January 1944, 10,500 women were employed underground.Footnote24 By the end of that year, over 19,000 women were working underground, nearly 18,000 of whom were in Bengal and Bihar.Footnote25 By 1945, 22,517 worked underground and nearly 50,000 above ground ().

Table 1 WOMEN WORKERS IN INDIAN COAL MINES (1939–1947).

It was predicted that the employment of women underground would have a psychologically-important effect since men apparently preferred working ‘with their womenfolk’.Footnote26 In the many times social reformer Bhimrao Ramji (Babasaheb) Ambedkar, Labour Member in the Viceroy’s Executive Council, defended the decision, he maintained – and was widely quoted – that:

It is a mistake to suppose we could draw indefinitely on the 400,000,000 of India for work in the coal mines … The number of people who have a bias against work in the coal mines is very large.

The Indian worker is too poor not to depend on the earnings of his wife to supplement his income. At the same time he is a jealous husband. If his wife is to work, he must see that she works with him, and under his eyes…In short, if you want to get the miner to work, it is also necessary to provide work for his wife.Footnote27

This was supposedly more effective than increasing wages to match higher pay in military works. Viewed through the lens of exceptionalism, the crafting of an ‘Indian aboriginal worker’ as someone who preferred working in a ‘family unit’, for whom higher wages were not an incentive, and as essentially different from an ‘Indian worker’ type, created an ‘other’ doubly subject to the colonial state and capital. Take civil servant Aubrey Dibdin’s comment:

Roughly the position is that none but aboriginals will accept the conditions offered by India’s mine owners … If the conditions were less filthy they would get a better class of labour in the mines.Footnote28

Racial discrimination permeated into wage discussions, where ‘semi-aboriginals would have the less incentive to work consistently in the pits if by a week’s work they earned enough to keep them for a fortnight’ since they were ‘very feckle [sic] people’.Footnote29 These conclusions were based on conjecture.Footnote30 The mismatch in attitudes towards British and Indian labour was rooted in ideologies of race and empire, where imagined superiorities in terms of race and class translated into misguided, discriminatory, and harmful labour policies. The Indian Labour Department had asked in August 1943 whether the British government were considering allowing women to work underground in coal mines in Britain.Footnote31 The India Office consulted the Coal Division, which replied, ‘… I should imagine there is no question, and will not be any question, of employing women underground’.Footnote32 The difference drawn between Indian and British women is further evidence of the othering of colonised women. Employers had long played up this constructed separateness, often using the ‘backwardness’ of adivasis to resist regulation. It is unsurprising to see this report by an Indian government committee in the late 1930s:

[The coal trade in India is] a race in which profit has always come in first, with safety a poor second, sound methods an also ran [sic], and national welfare a dead horse, entered perhaps, but never likely to start.Footnote33

Since it was violating an international obligation, the Indian Labour Department was pressured into restricting women’s employment to loading work in galleries higher than six feet. They promised to employ welfare officers, including a female officer, and institute a cess on coal despatches for health, education, and general facilities.Footnote34 The Indian government took over statutory control of production and welfare.Footnote35 In February 1944, a welfare fund was instituted by ordinance and levied a cess on coal and coke despatches for housing and water supply.Footnote36 It might appear the government was trying to compensate for suspending the prohibition, although a closer look reveals gaping holes. A single female welfare officer was to be appointed when they estimated women workers in thousands. When the Women’s Publicity Planning Association, an international mouthpiece for women’s wartime activities, raised concerns, the E&O dismissed them. The Association was anxious that women were not exploited by being paid lower wages than men and hoped the government would institute compulsory medical examination as it had for men conscripted to mines in Britain.Footnote37 The E&O dismissed the gender wage gap as insignificant, saying ‘presumably’ there would be no difference this time. Examination was impracticable because of the shortage of doctors, and unnecessary, because, the E&O asserted, women were flocking to mines of their own volition.Footnote38

The people, the press, and the platform

The British and Indian governments would receive several letters of protest over the next three years:

Strong opposition to the employment of women underground has been voiced both in India and abroad, particularly from the women’s organisations. In the press and on the platform, in the Indian Legislature and in the Houses of Parliament, the measure has been vehemently criticised.Footnote39

In England, individuals wrote to Amery or their members of parliament (MP), whom they urged to question the measure.Footnote40 Thirteen people from Horsforth, Leeds signed an undertaking to ‘register an emphatic protest’ against ‘a blot on our national honour and a negation of the principles for which the war is avowedly being fought’.Footnote41 A Mrs. Wright from Highgate wrote to Amery: ‘Any Englishman having anything to do with this disgraceful measure, lowers the prestige and honour of his country, and shows himself unfit for office’.Footnote42 An E.E. Penfold from Chelsea sought assurance that no children would enter mines.Footnote43

The Birmingham Christian Action Fellowship condemned ‘this barbarous business’Footnote44 while the Churches of Christ, Great Britain and IrelandFootnote45 wrote ‘that the consciences of all Christian people will regard such a situation as intolerable’.Footnote46 Several unions passed resolutions and/or sent emphatic letters. At a political conference in Chester in January, a division of the National Union of Distributive and Allied Workers called for withdrawal of this ‘retrogressive step’.Footnote47 The Birmingham Fire Brigades Union adopted a resolution condemning the ‘distinction being drawn between English and Indian womenfolk … a further example of the shameful treatment meted out to the Indian peoples by the British Government’ and demanded immediate withdrawal. The fight against fascism depended on harnessing India’s full potential, possible only by giving her independence, they wrote.Footnote48 Other branches of the Union of Distributive and Allied Workers,Footnote49 the Fire Brigades Union,Footnote50 the Derby and District Trades Council,Footnote51 and the Clerical and Administrative Workers UnionFootnote52 expressed their strong disapproval. Local Labour Party branches pressed the National Executive to raise the issue.Footnote53

Women’s groups like the Bowes Park Women’s Co-operative Guild wrote to Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Amery calling it a ‘retrograde step in Civilisation and English Government’.Footnote54 The Women’s Section of the Wimbledon Labour Party wrote to their MPFootnote55 while the National Federation of Women’s Institutes wrote to the India Office.Footnote56 The National Council of Women of Great Britain expressed its objectionsFootnote57 while South Harrow Women’s Cooperative Guild protested against the ‘violation of the promises given to women for their sacrifices during this war’, adding, it ‘makes false the praises sung in that direction, particularly in regard to FREEDOM’.Footnote58 The Women’s Advisory Council on Indian Affairs consulted the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) and the National Council of Women in India (NCWI) and appealed for reconsideration after six months.Footnote59 The India Office was greatly amused by a ‘most entertaining reaction from some feminist organisation who recorded the view that it was rather a good thing that women should be given the same employment of men’.Footnote60 In India, the AIWC coordinated the response. In August 1943, they sent a telegram to the Indian government; letters from its Punjab,Footnote61 Hyderabad,Footnote62 and DelhiFootnote63 branches followed. In 1945, the AIWC declared 21 February as ‘Mines-Day’, and branches across the country passed resolutions.Footnote64 The Chicacole Ladies Recreation Club wrote to Viscount Wavell, the Viceroy of India.Footnote65 The NCWI sent a telegram to the Queen:

Humbly beseech Your Gracious Majesty intercede for securing cancellation of recent order drafting women for work underground in Indian Coal Mines contrary to League of Nations conventions and unknown in any Allied Country. Terrible conditions deterioration moral and physical reported. We respectfully appeal to Your Majesty as a woman prevent this horror towards several thousand unfortunate Indian women.Footnote66

The Queen’s Private Secretary did not reply.Footnote67

This transnational and highly emotional humanitarian campaign is akin to an inchoate global civil society advocating a certain idea of morality that had become bound up with women’s labour conditions. Newspapers, particularly those with socialist leanings, acted as conduits for information and mobilised public opinion. New Leader reported: ‘They did work that, in this country, is done by pit ponies. They were actually strapped to the coal wagons, which they were compelled to haul along the roads and up steep inclines’.Footnote68 The Manchester Guardian wrote about ‘ridiculously low’ wages, which had decreased by 45 per cent.Footnote69 India Today, organ of the India League of America, condemned the ‘alien government’.Footnote70 In India, Indian Nation and Patna Times heavily criticised the policy.Footnote71 Eastern Economist published a vitriolic article, describing ‘countrywide protest’.Footnote72 The Times of India consistently reported parliamentary debates and developments.

Reactions across India and Britain and different media show how much had changed since the first prohibition. In 1937, apart from a self-congratulatory government, there had been minimal reaction. Debates on prohibition had remained confined to state and capital, involving little articulation of public opinion. Between 1943 and 1946, the degree of censure and the diversity of participants escalated to unprecedented levels, and a discourse on Indian female labour emerges for the very first time in the public sphere. Independence movements and a greater role for women in public life contributed to this.Footnote73 For supporters of Indian nationalism, this became an issue on which the colonial state could be attacked, while the British Labour Party used it to criticise the Conservative government.

By framing them as ‘wives’ or ‘mothers’, the personhood of mining women was repeatedly denied by the state, capital, and interest groups. The colonial state saw women as ‘wives’, as inducements for male labour and not individual providers of labour power. Critics, on the other hand, with little to no awareness of ground realities, saw them as ‘mothers’ and played on emotive images of pregnant women and mothers with infants going underground. Miners themselves were neither able to nor invited to articulate their views in an elite Anglophone sphere that argued on the basis of abstract notions like ‘civilisation’ and ‘morality’. Women’s access to positions of recognition and power were restricted to the privileged from upper classes and castes, who were just as distanced from mining women’s realities as government officials. Considering limited labour organisation, the unions’ voice came from Britain, but expressed an opinion that, as we will see, would be anathema to the thousands who had taken to working in mines out of desperation. As the next section will demonstrate, the colonial establishment distorted and manipulated information.

Amery drafted an evidently ineffective letter to respond to this onslaught. While emphasising how vital Indian coal production was to the war effort, it placed the onus for the crisis on labour characterised as ‘semi-aboriginals and very unstable’. By saying that men shifted to employment in military works because husband and wife could work together and that, hence, re-employing women remained the only option to increase male labour, Amery glossed over the critical labour women as individuals were providing. He assured his critics that the ‘so reluctantly taken’ measure would be reconsidered in six months.Footnote74 The House of Commons became a testy battleground for Amery as soon as suspension became public knowledge, when Labour MPs Reginald Sorensen and feminist activist Edith Summerskill fired a volley of questions in January 1944.Footnote75

Meanwhile, an Estelle Blythe sent the government helpful information. Her MP had found that 25 per cent of underground workers in the USSR were women, ‘and the Soviet authorities were rather surprised at his surprise!’, Blythe wrote, since Soviet Russia ‘is the pattern for all workers’ it was surely not ‘so wicked’ for wartime India to be doing the same.Footnote76 Reassured by confirmation from Soviet War News, the government used this to prop up its defence.Footnote77 On 17 February, Sorensen led an adjournment motion in the Commons.Footnote78 The crux of the defence, led by Richard Austin ‘Rab’ Butler, former Indian Under-Secretary of State, lay in the exigencies of war:

…the most elementary and fundamental “rights of man” – as well as such more highly developed rights as are the subject of this Convention – are liable to have to be placed in pawn under the imperative necessities of war, and that winning the war is an essential prerequisite to avoiding worse things than the temporary suspension of this ban.Footnote79

Butler said that ‘the women have done a service in what they have undertaken for the war effort in India’, an angle nobody else pursued.Footnote80 The government’s inability to respond effectively was partly due to a fundamental misunderstanding of the gravity of the situation as confirmed by a private letter from Viceroy Wavell to Amery: ‘The coal position was so bad that something had to be done, and the decision hardly seemed to us here to be controversial’.Footnote81 In Delhi, nationalists frequently raised the issue in both houses of parliament.Footnote82 The major parliamentary intervention was in women’s representative Renuka Ray’s internationally-reported adjournment motion on behalf of the AIWC.Footnote83 Supporters of her motion revealed that the monthly average wage in the Jharia coalfields was 14 or 15 rupeesFootnote84 compared to 30 rupees in the neighbouring industrial town of Jamshedpur.Footnote85 The Muslim League criticised the Europeans for thinking of profit during war,Footnote86 while Congress members left the House in protest. Ray’s motion was defeated 41 votes to 23 despite support even from the Independents.Footnote87

This considerable pressure led the Indian government’s attempt to recruit at least 10,000 men.Footnote88 Meanwhile, it exempted mine-owners from excess profits taxes and introduced a scheme to regulate prices and distribution and provide bonuses on increased output.Footnote89 The first six-month deadline for reviewing the ban was approaching, but there was no question of re-imposition. It was estimated that women, while helping match production goals, were preventing the loss of 385,000 tons per month. Delhi wrote to London: ‘That absolute need could not be met by other methods of bringing labour underground’. Though a depreciation of 50 per cent and loans were introduced to encourage mechanisation, the Labour Department was convinced the coal industry could not survive without female labour. Footnote90

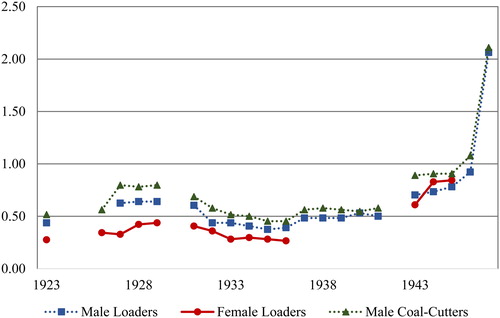

It is unsurprising, therefore, that when British Labour Minister Ernest Bevin was asked whether he would be reporting the continued non-observance of the Convention to the ILO, his response was negative.Footnote91 The suspension of prohibition became a thorn in the side of the colonial establishment. Labour Member Ambedkar, who defended the decision publicly, pressed the Executive Council to review it in private discussions. The government responded saying it ‘could take no risks and that it seemed to be established that women had played a very important part in maintaining output’, so they might have to be retained for the war’s duration. They worked out a system whereby at ‘reasonable intervals’ Ambedkar would demand a review and the Supply Member would make a performance of satisfying the Council of the need for employing women, the approval for which would be a foregone conclusion.Footnote92 A narrowing gender wage gap indicated the depth of the crisis ().

FIGURE 1. UNDERGROUND DAILY WAGES (RUPEES) IN EASTERN COAL MINES, 1923–1947.

Sources: Annual Reports of the Chief Inspector of Mines in India, 1923–1947

That women were a crucial reserve of mining labour is evidenced by the failure of all other measures to deal with the crisis. Official reports acknowledged women were ‘steadier in employment and often times more efficient than the men’.Footnote93 Efforts to import male labour from Gorakhpur proved ineffective. The War Transport Member said at an Executive Council meeting: ‘The Gorakhpur labourers were not miners but the women were and the women had saved the situation’.Footnote94 Those privy to the truth of the indispensability of women agreed that keeping quiet was the best way forward.Footnote95 India was not out of the woods until the end of the war in the Asian theatre.Footnote96 In Japan, an unprecedented 70,577 women were mining coal – though fewer than in India.Footnote97 If coal was needed, female labour would be too.

Meanwhile, parliamentary condemnation continued. In the Commons, it was labelled an ‘abominable form of industrial slavery’Footnote98 and ‘cold-blooded cruelty to expectant mothers’.Footnote99 In a landmark moment in Delhi, Renuka Ray’s cut-motion against the Labour Department on 13 March 1945 carried without division.Footnote100 She drew attention to ‘constant and insistent protest throughout the country’ and how the Indian government had ‘considerably shocked and offended world opinion’. In the defence, Ambedkar pointed out contradictions in the AIWC’s stand, quoting their 1935 report: ‘If these women are removed from underground work in the present condition, the distress will be so great in the miners’ homes that it will far outweigh the evils of allowing them underground’.Footnote101 That it had condemned prohibition not ten years previously, and was now vehemently advocating for it, shows how distanced even an Indian women’s organisation like the AIWC was from working women’s realities.

Repeated questioning prompted an investigation into maternity benefits legislation. Pregnant women were not prohibited from working in mines, but the Mines Maternity Benefit Act 1941 prohibited employment for four weeks following the child’s birth.Footnote102 If the mother had been continuously employed at the mine for six months, she could claim two-thirds of her ordinary income for four weeks each before and after birth.Footnote103 Claims were routinely dismissed, however, and not one payment had been made in state-owned collieries. Ray claimed children regularly worked underground, since there were no crèches or schools, and women continued to work until the ninth month and even after giving birth.Footnote104 In 1945, the Indian government passed what was in its opinion ‘very remarkable legislation’ by giving way ‘to much more drastic proposals’ on maternity benefits that it had spent decades vacillating on – a clear attempt to appease mining women. Pre-natal absence for ten weeks was made compulsory, and post-natal absence was raised from one to six months. During the seventh to ninth months, a four-hour shift limit was imposed. Benefit was payable from ten weeks before birth until six weeks after and increased from eight to twelve annas a day.Footnote105 From July, milk was supplied to mining women.Footnote106

That month, Amery lost his seat in the general election. On 1 November 1945, well after Japan’s defeat and with a Labour government in Britain, it was decided it was time to re-impose prohibition.Footnote107 An official rued that India would no longer be able to contribute to dealing with the worldwide shortage of clothing, which would extend clothes rationing in Britain.Footnote108 Viceroy Wavell admitted to Baron Pethick-Lawrence, the new Secretary of State for India and Burma, that it would cause a ‘considerable drop’ in raisings, but the whole thing had been ‘wrong in principle’, and the second prohibition was scheduled for 1 February 1946.Footnote109 It was time for this episode ‘to fade from the public memory’.Footnote110

Distortion, discipline, and deprivation

For the colonial establishment, the wartime imperative justified the relentless extraction of resources and pressure on what they saw as a dispensable mass of people. This was an episode rife with distortion, misrepresentation, and concealment of facts. Even those criticising the suspension of prohibition, however, were missing the point. Occasionally, hints of the terrible truth had bubbled up to the surface. Hidden in Amery’s letter defending the move was a mention of ‘food scarcity’ that had pushed workers to their villages ‘out of anxiety’ for their families, prompting labour shortage.Footnote111 In February 1944, the Manchester Union of Distributive and Allied Workers passed a resolution attributing the ‘deplorable situation, where thousands are allowed to starve, to the policy of those reactionary elements in this country who have always sacrificed the interests of the mass of the people to those of the privileged few’. It urged Amery be replaced for his constant belittling of a tragedy in the making.Footnote112 Bengal in 1943 was going through terrible famine that killed an estimated three to five million; this is today attributed to colonial wartime policies.Footnote113

The shortage of coal affected the running of the railways, which impacted the movement of food supplies, and this in turn worsened the famine.Footnote114 At least 60,000 cultivators had been forced to sell their land so as to afford black-market prices of rice.Footnote115 Crucially, the government offered a deal whereby those who went to coal mines would have their property restored to them.Footnote116 Many were dying of malnutrition-related diseases,Footnote117 so an increase in cost-of-living bonus, provision of food and consumer goods, and improvement in welfare facilitiesFootnote118 were not merely incentives in any ordinary labour market; nor were they comparable to other wartime labour situations. The context of a famine that put millions at risk with a colonial state that failed spectacularly in dealing with it should make us ask questions about how ‘voluntary’ mining work was. Famine and inflation likely have a greater impact on women, given their bargaining power for shared resources in families tends to be lower. The most shocking measures were exposed in an article, ‘Do Hardest Work, But Worst Paid’, in The Daily Worker. Mr Dange, leader of the All-India Trades Union Congress delegation to the World Conference, told the Daily Worker journalist that ‘[t]he miners are the worst-paid workers in India’. Furthermore, Dange stated, ‘[t]heir wages, which average 9 s. a week, including cheap rations and allowances, compares with 12 s. a week paid to war workers near the mine areas, whose working conditions are much easier’. ‘You may judge for yourself the truth of Mr. Amery’s assertion that work in the mines is entirely voluntary’, Dange continued. ‘When during the famine, miners began to leave the mines as their wages did not keep pace with the rising cost of food, the Government issues instructions that miners were not to be employed in other industries … In addition, workers who enlisted as miners and who absented themselves from work, forfeited their right to food supplies in the area.’Footnote119 Only when it was clear that ‘all prohibitions possible’ were not working, was improving working and living conditions considered.Footnote120 With a 233 per cent rise in living costs in 1944 over 1939, miners’ weekly wages should have been 7–15–2 rupees, but were raised only to 5–15–5 rupees (a 50 per cent increase over previous wages).Footnote121 In Britain, miners’ weekly wages had risen from £3.1 s.9d in 1939 to £5.13 s.– in 1944Footnote122 (an increase of nearly 83 per cent) with a 30 per cent increase in living costs.Footnote123 Dange described this as ‘conscription through starvation’, ‘a mode of serfdom’ where one pound of wheat, rice, or maize would be given daily only if the miner worked at least five days per week (there was no concept of sickness leave). Workers’ ration cards were in the hands of contractors who took advantage of this to sell their food on the black market. Girls over twelve were ineligible for rations and were expected to work at the colliery.Footnote124

No discussions in official records or newspapers reflect how serious the situation was. That for many women underground work in the mines was quite literally a matter of life and death was neither realised by government nor by those who criticised it. Hunger had always been a leitmotif of poorly-paid miners’ lives. Average calorific consumption in non-famine periods for a male miner was 2,694.39 calories against the 3,500 considered essential. Women almost definitely consumed fewer calories. While diets differed according to community or caste, they tended to be carbohydrate-heavy, protein-deficient, and ‘hopelessly insufficient’ in fats.Footnote125 This lower calorific intake undoubtedly contributed to low levels of productivity.Footnote126 By making the availability of rations conditional on work, the colonial government used a cruel, but not unprecedented, method of disciplining labour. In Nazi Germany, shortage of coal and labour were major concerns. It was recognised that extra calories, proteins, and fats were essential to increasing productivity. One of the most successful coercive practices, which went on to be recommended by the Armaments Ministry, was ‘performance feeding’, by which workers with below-average productivity had their rations docked.Footnote127 In British India, workers faced having to forfeit their entire rations for absenteeism – this was discipline by deprivation.

The urgency was due to the magnitude of the crisis, which was seldom admitted. In May 1944, a reply to a question in the Commons on coal supplies to Portugal revealed that India’s coal was not for internal use alone.Footnote128 News Chronicle published a letter about the arrival in Lisbon of a cargo of coal in a British ship from Calcutta.Footnote129 Coal was in fact being sent to the Middle East and the Mediterranean (under the Azores Agreement to Portugal, whose airfields were vital for the war).Footnote130 The London Coal Committee’s report reveals that India’s coal exports were ‘highly strategic and important’ as they were the most economical for deliveries in the Mediterranean.Footnote131 As a British colony, India was beholden to export obligations not of its making. Without Indian coal supply to these regions, South African coal would have been diverted from Europe, where it was being used to prosecute the war.Footnote132 Several essential wartime industries were in India and ran on Indian coal. So, the ILO accepted suspension with little noise.Footnote133 The India Office had sent a confidential note to its acting director which contained ‘information which might hearten our enemies, regarding the extreme gravity of the coal situation in India’.Footnote134 India’s coal crisis was not just its own, but was in fact an Allied crisis. This explains the desperation of the colonial government and why it concealed facts. So, while it claimed otherwise, in 1943–1944, there were 911 fatal accidents to mining women.Footnote135 Malaria plagued the coalfields, the sickness rate rising from 53.6 in 1942 to 81.6 in 1944 in Raniganj, and from 17.2 to 43.3 in Jharia.Footnote136 Despite promises otherwise, women were employed in seams less than five and a half feet high,Footnote137 while those working above ground were paid half as much as men.Footnote138

Reading against the grain of official sources, it is possible to detect mining women’s agency, such as from the Labour Department’s reluctance to reimpose the ban in January 1945 for fear of ‘causing discontent, with possibly serious repercussions’. At the Viceroy’s Executive Council meeting, the Food Member said:

The women wanted to work and at present were making money which they could not make elsewhere. If a plebiscite was taken it would become clear that they did not want any ban at all.Footnote139

Workers were anxious about the ban’s re-imposition and whether it would remove women’s eligibility for rice, clothing at concessional rates, and maternity benefits at enhanced underground rates.Footnote140 The total number of women working above and below ground in coal mines in 1946 was 77,294. In February, 22,517 underground women workers were ‘thrown out’.Footnote141

Only about 2,000-odd women found new employment.Footnote142 Great unrest began soon after, and the government’s response was revealing. In July, mines were required to build twenty-four-hour crèches, provide monthly medical examinations of children, and establish separate baths and lockers for women.Footnote143 As protests continued,Footnote144 provincial Labour Ministers approved a five-year programme to improve health, working conditions, and living standards. A Coalmines Wages Enquiry Committee was set up in October.Footnote145 A miners’ housing scheme was instituted, providing a subsidy of one-sixth of construction costsFootnote146 for 50,000 houses.Footnote147 As strikes continued into April 1947, the only initiatives that resolved them were ones aimed at women. A welfare work scheme to provide visual and craft education for miners’ families aimed to improve living standards and provide an income through organised cottage industries. It would be run exclusively by women who would be trained in social welfare work. A training course for crèche attendants was begun.Footnote148 Sites were requisitioned for vegetable gardens and farms where women were to be employed as gardeners.Footnote149 The Coalmines Labour Welfare Fund Act 1947 authorised further levies for dispensary services, maintenance, and housing.Footnote150 So, while we may not have mining women’s own accounts, these concessions indicate they played a major role in the unrest. This challenges the understanding of women workers as ‘docile’Footnote151 and is evidence of their successful resistance to the colonial establishment and to the construction of mines as masculine spaces.

Conclusion

Coal, a linchpin of the war effort, rested on the keystone of female labour. Yet discussions around them in public and official spheres divest women of control over their bodies. The treatment of women workers as objects who could be made to appear and disappear with ill-informed legislative decisions from Delhi or London, as well as impassioned pleas to rescue them from what was in many cases, their only chance of survival, acted to deny mining women agency and ownership over their labour power.

Mining women, by virtue of their occupation, were hidden beneath the surface. Further marginalised by their gender, social status, and location, their stories have so far been invisible. Assumptions about the marginality of women have ensured the pervasiveness of the myth that mines are masculine spaces – so much so that most people today are shocked women had any role at all to play in this industry, let alone as pivotal a role as they did during the Second World War. The colonial establishment’s cruel conduct and deliberate distortions were aided and abetted by such underlying assumptions. Yet the point remains that, at the time, this was not an obscure story. How and why did mining women disappear from the public sphere – from this transnational discourse that captured the imagination and empathy of a wide range of people the world over – as rapidly as they entered it? Distant from the frontline and at the outermost edges of the periphery, India’s mining women have been easily forgotten. The present looks just as precarious as the past for them. The postcolonial state has made sustained efforts to dispossess adivasis of their land and rights in the face of staunch indigenous struggle.

So, how does this story of female power fit with a war that tends to be remembered primarily in terms of western male failures and achievements? These were women who worked in trenches, in underground galleries, and in pits on the surface, in extreme heat and humidity, in the constant presence of explosives, in once thickly-forested lands that had been laid to waste. Sometimes they took their children with them. It is not difficult to find parallels with ‘conventional’ masculine experiences of warfare. But it should not be necessary to couch mining women’s contributions in male terms for them to be remembered. Experiences of the global Second World War were strongly gendered and racialised. That was the norm, not the exception.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Urvi Khaitan

Urvi Khaitan is a doctoral student in economic and social history at the University of Oxford. Her research interests lie in gender, labour, and empire in twentieth-century South Asia, and her doctoral thesis focuses on women in the South Asian wartime economy of the Second World War. Her MPhil dissertation, ‘Women Beneath the Surface: Coal and the Colonial State in India, 1920s–1940s’, on which this article is based, was awarded the Oxford University History Faculty’s 2019 Feinstein Prize.

Notes

1 A. Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (London: Penguin, 2007); D. Edgerton, ‘Controlling Resources: Coal, Iron Ore and Oil in the Second World War’, in The Cambridge History of the Second World War, vol. 3, Michael Geyer and Tooze (eds) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

2 A. Jackson, The British Empire and the Second World War (London: Hambledon, 2006); Y. Khan, The Raj at War: A People’s History of India’s Second World War (London: Vintage, 2016).

3 A similar approach is used in T. Pratt and J. Vernon, ‘“Appeal from this fiery bed …”: The Colonial Politics of Gandhi’s Fasts and Their Metropolitan Reception’, Journal of British Studies, 44:1 (2005), 92–114.

4 IOR/L/E/8/4892, A. Dibdin, Marginal Comments, 24 December 1943.

5 In 1944, it would be discovered that the USSR was also employing women underground. See below.

6 S. Dasgupta, ‘Introduction’, Indian Economic and Social History Review, 53:1 (2016), 2.

7 C. Bates, ‘Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: The Early Origins of Indian Anthropometry’, in The Concept of Race in South Asia, Peter Robb (ed) (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995), 219–59.

8 V. Damodaran, ‘Colonial Constructions of the ‘Tribe’ in India: The Case of Chotanagpur’, The Indian Historical Review, 33:1 (2006), 44–75; R. Guha, ‘The Prehistory of Community Forestry in India’, Environmental History, 6:2 (2001), 213–38.

9 U. Khaitan, ‘Women Beneath the Surface: Coal and the Colonial State in India, 1920s–1940s’ (MPhil diss., University of Oxford, 2019).

10 Women’s Indian Association, The Modern Review, November 1922, 659.

11 Chaman Lall’s speech in the Indian Legislative Assembly quoted in the House of Commons, HC Deb 14 May 1924 vol 173 cc1464–510.

12 J. Humphries, ‘Protective Legislation, the Capitalist State, and Working Class Men: The Case of the 1842 Mines Regulation Act’, Feminist Review, 7 (1981), 1–33.

13 Khaitan, 35–66.

14 S. Raghavan, India’s War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia (New York: Basic Books, 2016).

15 NAI 59/CF/43, E.C. Donoghue to Executive Council, 17 November 1943, 18.

16 IOR/L/E/8/4892, News Chronicle, 20 December 1943.

17 Indian Jute Mills Association, Report of the Committee (Calcutta: Reliance Printing Works, 1944).

18 IOR/L/E/8/4892, London Coal Committee, Report by Sub-Committee on the Indian Coal Situation.

19 News Chronicle, 20 December 1943.

20 NAI 59/CF/43, Telegram from Labour Department to Secretary of State for India Amery, 30 December 1943, 28.

21 IOR/L/E/8/4892, H.A.F. Rumbold, Secretary, E&O, 23 December 1943.

22 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Cypher telegram, 25 December 1943.

23 News Chronicle, 20 December 1943.

24 IOR/L/E/8/4892, C.F. Wood, Comment, 22 May 1944.

25 IOR/L/E/8/4892, H.C. Prior to Rumbold, 24 March 1944.

26 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Colliery Guardian, 31 December 1943; News Chronicle, 20 December 1943.

27 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Ambedkar’s statement on women in coal mines, 23 January 1944.

28 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Dibdin, Marginal Comments, 24 December 1943.

29 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Private Secretary to Under Secretary of State for India, 27 January 1944.

30 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Prior to Rumbold, 24 March 1944.

31 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Inward Telegram Secret, 22 August 1943.

32 IOR/L/E/8/4892, J.H. Wilson to W.R. Rayner, 28 August 1943.

33 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Manchester Guardian, 26 January 1944.

34 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Telegram, 31 December 1943.

35 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Telegram, 21 December 1943.

36 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Reuter Messages, 1 February 1944.

37 IOR/L/E/8/4892, D. Evans to Minister for India, 20 December 1943.

38 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Secretary, E&O to Evans, 31 December 1943.

39 NAI 59/CF/43, Donoghue to Executive Council, 8 October 1945, 58.

40 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Letters from: K. Kendall, undated; Commander Sir A. Southby, MP, 8 January 1944.

41 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Various signees to Amery, 29 January 1944.

42 IOR/L/E/8/4892, E. Wright to Amery, 22 January 1944.

43 IOR/L/E/8/4892, 2 February 1944.

44 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Christian Action Fellowship to Amery, 3 January 1944.

45 The Churches of Christ, Great Britain and Ireland was an organisation based in Bournemouth. It appears to have been a fellowship of churches.

46 IOR/L/E/8/4892, J.G. Clague to Amery, November 1944.

47 IOR/L/E/8/4892, H. Weate to Amery, 25 January 1944.

48 IOR/L/E/8/4892, F. Griffiths to Amery, 6 February 1944.

49 IOR/L/E/8/4892, L. Davies to J.D. Mack, undated.

50 IOR/L/E/8/4892, J. Changer to Amery, 18 April 1944.

51 IOR/L/E/8/4892, R. Cary to J. Noel-Baker, 15 March 1944.

52 IOR/L/E/8/4892, M.E. Good to Amery, 3 April 1944.

53 Labour Party Archives, LP/ID/IND/1/118-119, F.E. Johnson to J.S. Middleton, 11 March 1944.

54 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Bowes Park Women’s Co-operative Guild to Winston Churchill and Amery, 27 January 1944; to C.F. Wood, 17 February 1944.

55 IOR/L/E/8/4892, S.M. Lewcock to Sir John Power, 10 February 1944.

56 IOR/L/E/8/4892, F. Farrer to India Office, 19 April 1944.

57 IOR/L/E/8/4892, K. Cowan to Amery, 13 March 1945.

58 IOR/L/E/8/4892, C. Biskeborn to Amery, 15 March 1945.

59 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Lady Hartog to Amery, 10 February 1944.

60 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Rumbold to Prior, 14 January 1944.

61 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Council of State Debates, 24 February 1944.

62 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Telegram to Amery, 8 March 1945.

63 IOR/L/E/8/4892, S. Singh to Amery, 24 February 1945.

64 IOR/L/E/8/4892, R. Shigaokar to Amery, 8 March 1945; B. Satyavathi and Leelavathi to Labour Department, New Delhi, 17 March 1945.

65 IOR/L/E/8/4892, S. Bhai to Amery and Viceroy, 24 February 1945.

66 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Council of State Debates, 24 February 1944.

67 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Acting Private Secretary to the Queen to India Office Private Secretary, 28 January 1944.

68 IOR/L/E/8/4892, New Leader, 8 January 1944.

69 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Manchester Guardian, 26 January 1944.

70 NAI 48/2/44-Poll(I), India Today, Vol. V. No. 1, April 1944.

71 NAI 18/11/43-Poll(I), ‘Fortnightly press review of the Provincial Press Adviser, Bihar, for the second fortnight of November 1943’.

72 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Eastern Economist, 2 March 1945.

73 See T. Sarkar, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2001).

74 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Amery’s letters (several).

75 HC Deb 20 January 1944 vol 396 cc350–2.

76 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Letter from E. Blythe, 22 January 1944.

77 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Soviet War News, 11 January 1944.

78 HC Deb 17 February 1944 vol 397 cc491–502.

79 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Draft brief for debate in House of Commons on Employment of Women Underground in India.

80 HC Deb 17 February 1944 vol 397 cc491–502.

81 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Private letter from Viceroy Wavell to Amery, 10 February 1944.

82 Council of State Debates, 24 February 1944 and 21 February 1945.

83 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Legislative Assembly Debate, 13 March 1945.

84 One rupee was equivalent to 18d. T. Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857–1947 (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011), xviii.

85 In comparison, the fighting sepoy was paid 37–8–0 rupees per month, and had most needs taken care of: Khan, The Raj at War, 220.

86 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Hindustan Times, 9 February 1944.

87 NAI 48/2/44-Poll(I), India Today, Vol. V. No. 1, April 1944.

88 IOR/L/E/8/4892, The Mining Journal, 4 March 1944.

89 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Telegram from Indian Department of Information and Broadcasting to Amery, 28 March 1944.

90 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Prior to Rumbold, 24 March 1944.

91 HC Deb 12 October 1944 vol 403 cc1914–6.

92 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Private and secret letter from Wavell to Amery, 5 February 1945.

93 Labour Investigation Committee, Report on an Enquiry into Conditions of Labour in the Coal Mining Industry in India (Delhi: Manager of Publications, 1946) (LICR), 20.

94 NAI 59/CF/43, Minutes, Executive Council Meeting, 31 January 1945, 50.

95 IOR/L/E/8/4892, A.F. Morley, 23 April 1945.

96 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Iron and Coal Trades Review, 1 June 1945.

97 Edgerton, ‘Controlling Resources’, 137.

98 HC Deb 08 February 1945 vol 407 cc2209–10.

99 HC Deb 07 June 1945 vol 411 cc1067–9.

100 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Reuter Message, 13 March 1945.

101 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Legislative Assembly Debates, 13 March 1945.

102 IOR/L/E/8/4892, E&O, Note.

103 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Draft letter.

104 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Legislative Assembly Debates, 20 November 1944.

105 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Morley, 23 April 1945.

106 IOR/L/E/8/4892, ‘Commerce’, 7 July 1945.

107 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Reuter; The Times of India, 1 November 1945.

108 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Morley, 14 November 1945.

109 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Secret and private letter from Wavell to Lord Pethick-Lawrence, 29 October 1945.

110 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Morley, 14 November 1945.

111 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Amery’s draft letters.

112 Labour Party Archives, LP/ID/IND/1/112-117, J. Hallsworth to Middleton, 15 February 1944.

113 J. Mukherjee, Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

114 Raghavan, India’s War, 337.

115 News Chronicle, 20 December 1943.

116 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Telegram, 21 December 1943.

117 NAI 59/CF/43, Donoghue to Executive Council, 17 November 1943.

118 IOR/L/E/8/4892, News Chronicle, 20 December 1943; Colliery Guardian, 31 December 1943.

119 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Daily Worker, 9 February 1945.

120 Donoghue to Executive Council, 17 November 1943.

121 S.A. Dange, Death Pits in Our Land: How 200,000 Indian Miners Live and Work (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1945), 11.

122 HC Deb 31 May 1949 vol 465 cc150–1W.

123 Dange, Death Pits, 11.

124 Ibid., 14–15.

125 B.R. Seth, Labour in the Indian Coal Industry (Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Company, 1940), 234.

126 Edgerton, ‘Controlling Resources’, 137–8.

127 Tooze, The Wages of Destruction, 529–531.

128 HC Deb 11 May 1944 vol 399 c2111W.

129 IOR/L/E/8/4892, News Chronicle, 18 May 1944.

130 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Marginal Comments.

131 IOR/L/E/8/4892, London Coal Committee, Report.

132 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Morley, 14 November 1945.

133 IOR/L/E/8/4892, E.J. Phelan, Acting Director, ILO, to S.E. Runganadhan, High Commissioner for India, 15 March 1944.

134 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Runganadhan to Phelan, 18 January 1944.

135 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Daily Worker, 23 February 1945.

136 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Prior to Rumbold, 24 March 1944.

137 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Prior to W. Kirby, 27 September 1945.

138 IOR/L/E/8/4892, Morley, 23 April 1945.

139 NAI 59/CF/43, Donoghue to Executive Council, 25 January 1945.

140 LICR, 21.

141 IOR/L/E/8/4886, Review of Labour Situation in India (RLSI), February 1946.

142 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, March 1946.

143 IOR/L/E/8/4886, Department of Labour Notification, 23 July 1946.

144 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, September 1946.

145 IOR/L/E/8/4886, Press Communique, 16 October 1946.

146 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, October 1946.

147 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, December 1946.

148 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, January 1947.

149 LICR, 20.

150 IOR/L/E/8/4886, RLSI, February 1947.

151 The Times of India, 9 October 1928.