ABSTRACT

This article explores the policy failure of the NSW ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ (implemented through State Environmental Planning Policy (Exempt and Complying Development Codes) 2008 (Codes SEPP)). The Code came into full effect (across all NSW LGAs) on the 1st of July 2020 following a number of deferral periods since its formal adoption in 2018. The Code was intended to address Sydney's ‘missing middle’, notably medium density housing to address affordability and the relative imbalance in available housing typologies between polarised market choices; the detached suburban house on a remote (greenfields) lot, and the apartment in a high density metropolitan centre. The policy ultimately failed to deliver the intended diversity it had seemingly promised. This article explores technical, legislative, political and economic factors contributing to the Code's limited application, as well as actions that further curtailed housing diversity, counter to the Code's intent.

Practitioner pointers

This article explores a number of factors contributing to the failure of the NSW ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ to deliver greater supply and housing diversity.

The Code was intended to address Sydney's ‘missing middle’, notably to increase the delivery of medium density housing types to improve affordability and address the imbalance in available housing types between polarised market choices; the detached suburban house on a remote (greenfields) lot, and the apartment in a high density metropolitan centre.

It was formally adopted in 2018 but only came into full effect (across all of NSW) on the 1st of July 2020 following several deferral periods that excluded its application to a number of objectionable local councils.

The policy not only failed to deliver the housing diversity it was intended to promote but initiated actions by local government authorities that further curtailed housing supply and diversity beyond the Code’s scope.

Introduction

Much was anticipated from the NSW Low Rise Housing Diversity Code.Footnote1 The Code promised more affordable alternatives between polarised choices; the detached suburban house on a remote (greenfields) suburban lot, and an apartment in a high density metropolitan centre.Footnote2

The middle ground between these polarised choices is increasingly being referred to as the ‘missing middle’, both internationally and here is Australia. The Code was designed to address the ‘missing middle’ by promoting ‘housing choice and diversity’, facilitating affordability through ‘Increased housing supply’ and housing types that ‘provide private open space, in most cases at ground level, which allows families to socialise, play, garden and exercise in their own home’.Footnote3 Accordingly the Code was intended to address the ‘middle’ in terms of housing type (low and mostly attached housing types with gardens) and affordability.

The Code promised to cut approval periods for small housing projects to several weeks under an ‘as of right’, state legislated ‘complying development’ approval process (CDCs), which can be assessed by public or private certifiers. This alternate approval path offered a welcome alternative to development applications (DAs) which are subject to increasingly protracted and uncertain approvals by local councils.

However, the implementation of the Code was fraught from the start with controversy that undermined its effectiveness and which contrary to its intent curtailed housing diversity. To understand why requires an understanding of the Code, the possibilities for its application, economics and, as always, politics.

Our office, Redshift Architecture & Art, has been researching the Code and the potential for its application since NSW Planning published the draft late in 2016, across 2 deferral periods since its inception in 2018 and the end of the final deferral period, 1 July 2020. The Code is now in full effect across all local government areas (LGAs) but remains largely ineffective and accordingly few projects have been approved under the Code.

The code

The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code provides the opportunity to undertake duplexes, dual occupancies, row housing (terraces) and a housing type [rather ambiguously] referred to as a ‘manor house’; essentially a triplex or fourplex apartment building. Under the Code, these housing types can be approved as (state based) complying development (called CDCs) or more conventional development applications (DAs) under local council approval.

Dual occupancies are generally permitted in most ‘R2 – low density residential’ zones as well as ‘R3 – medium density residential’ zones. The opportunity for dual occupancies in R2 and R3 zones (as conventional DAs) remains unchanged since prior to the Code’s inception but the Code permitted their approval as complying development; subject to compliance with the Code.

The possibility of row housing, permitted under the Code as complying development, is limited to sites with very broad frontages, more commonly available in greenfield or brownfield sites where subdivision of ‘superlots’ is possible. This opportunity was also available prior to the Code’s implementation through preexisting provisions of the NSW complying development provisions that permitted attached forms of housing for lots greater than or equal to 6 m width.

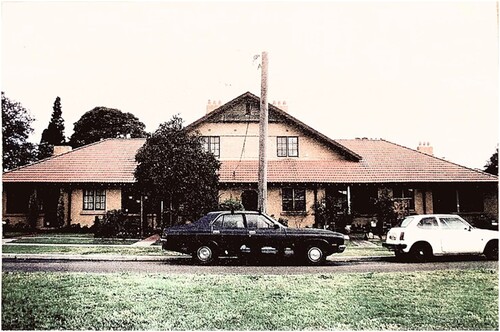

It is the manor house, that offered the greatest opportunity for the redevelopment of single suburban lots as triplexes or fourplexes to address Sydney’s ‘missing middle’. Manor houses bear some reference to ‘big house’ types that can be found in Daceyville; built around 1912 for the Housing Board (refer ). These were progressive housing types encompassing a variety of two, three and four dwellings under a single roof, usually with individual front doors to the street. Subsequently, more speculative projects were built in the 1940s; the Art Deco ‘4-packs’ that continue to pepper Sydney’s middle and inner ring suburbs like Randwick and Ashfield (refer ).

Manor houses, by definition are ‘a building containing 3 or 4 dwellings, where: (a) each dwelling is attached to another dwelling by a common wall or floor, and (b) at least 1 dwelling is partially or wholly located above another dwelling, and (c) the building contains no more than 2 storeys (excluding any basement).’Footnote4 They are generally permitted in zones where either ‘multi dwelling housing’ or ‘residential flat buildings’ are permitted with consent.

Figure 1. A typical ‘Big Cottage’ in Daceyville (1912), containing 4 dwellings under one roof, each with a front door to the street as a prospective model of a ‘manor house’.

The manor house () offered an opportunity not otherwise possible under the narrow definition contained in local environmental plans (LEPs) for ‘multi-dwelling housing’ (which are defined as attached housing types ‘where no part of a dwelling is above any part of any other dwelling’) and ‘residential flat buildings’ which are generally reserved for the medium to higher density zones. The manor house could be configured as either an apartment building or a conglomerate form that could include (attached) town houses types. The Code contains provisions for solar access and engagement with the street, in a way that most townhouse developments with their internally concealed entries and circulation driveways do not.

Figure 3. Author’s prototype design for a fourplex Manor House as Complying Development under the NSW Low Rise Housing Diversity Code.

The greatest potential for manor houses were the middle ring suburbs of Sydney where single lots are available with frontages of 15 metres (the minimum required by the Code) and with the added benefit of proximity and convenience to public transport, amenities and the city. It is the manor house that held the greatest opportunity to fulfil the ‘missing middle’ by offering diversity and affordability of dwelling types akin to a ‘house and garden’ at a more affordable ‘entry point’ than the free standing house.

Unfortunately, opportunities for manor houses have been marginalised, largely through local council intervention (as outlined under the subsequent heading ‘Council Intervention’). There are however further technical factors that contributed to the Code’s limited application.

Opportunities and limitations

Technical factors contributing to the limited application of the Code and manor houses in particular include:

Based on our own feasibility testing, the closer to the inner suburban ring you get, the better the feasibility for redevelopment under the Code, as the greater value of the completed project has the greatest potential to cover the project costs despite higher land purchase costs over a relatively consistent building cost.

Inner-ring suburbs, which could potentially offer more viable conditions for redevelopment do not typically have suitable sized lots due to their typically finer subdivision pattern.

Most middle-ring residential lots that have the required 15 m frontages can only support three unit manor houses. Manor houses for four units require sites with much rarer frontages approaching 18 metres, or dual frontages (corner site or rear lane). The limit of two (as duplexes) or three unit manor houses has implications on feasibility (refer further points below).

Developers assess and value sites on the basis of their development potential. The FSR (floor space ratio) equivalent for a manor house is typically about 0.45:1 to about 0.52:1.Footnote5 Any ‘R3 – medium density residential’ zones with permissible floor space ratios in excess of about 0.7:1 are not viable for the limited yield of only 3 or 4 units. Accordingly the feasibility of any sites with the capacity for a higher development yield will be compromised by significantly higher land purchase costs. This is an issue for LGAs such as Ku-ring-gai, which despite permitting manor houses in its R3 zones allow significantly higher FSRs.

Large swathes of Sydney’s middle ring suburbs (such as Campsie, Bexley and Kingsgrove) which would be well suited to ‘missing middle’ development do not have suitably sized lots, as frontages rarely exceed 15 m rendering their compliant zones ineffective for any form of development under the Code without costly and more complex consolidation.

Interrogating the context of the remaining opportunities (where permissibility and site availability more broadly align – outlined below) development does not ‘stack up’ financially, as total development costs exceed the resulting development value.Footnote6

The only significant LGA that retains broad site availability under the Low Rise Housing Diversity Code is Canterbury Bankstown (as it has large areas that are suitably zoned, is well serviced, and about as close to the city as any other potentially suitable LGA with compliant lot sizes). However, even there, the feasibility of building only three apartments to replace a single home (as outlined above) is not feasible except to small scale local builder/developers who are quite happy to exchange builder’s margin (the profit they would ordinarily attain building the project for someone else) for the profit on their own self directed development projects.

The limited potential to excise a profit from such projects (as outlined above) limits the potential for investors and a broader segment of the construction industry to back such projects. These limitations undermine the potential for the Code to more broadly and meaningfully contribute to housing supply.

Council intervention

Since the Code’s inception, several councils have amended their LEPs to limit its application. In order to prohibit the possibility of manor houses in particular, councils amended their R2 general residential zones (or similar) to delete ‘multi dwelling housing’ from the permissible land use tables. This is true of Lane Cove Council, Hurstville Council, and more recently Ryde Council, with Sutherland Council signalling a similar intent.Footnote7

In the context of the above limitations, sourcing suitable sites is very difficult, but there is a broader underlying problem relating to councils like Hurstville and Ryde, that actively deleted ‘multi dwelling housing’ from their land use tables as this also denied permissibility for townhouses (multi dwelling housing – via conventional DA approval) across broad areas of their LGAs.

While the technical, financial and site availability factors appear to have had a direct impact on the practical application of the Code, the greater concern resulting from the ad-hoc amendments to council LEPs, curtailed housing diversity beyond simply the Code’s limited application. The consequences of broad council reaction against the Code indirectly triggered a reversal of the Code’s purpose and intent by prohibiting other previously permitted housing types.

Conclusion

The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code was designed to deliver social and economic benefits to broader populations by improving affordability and housing diversity. It promised a genuine alternative to the currently polarised choice between the detached suburban house on a remote suburban lot, and an apartment in a high density metropolitan centre. It could have also consolidated populations closer to existing centres for environmental efficiency.

The protectionist policies of the councils that acted against the policy, presumably (though without significant evidence) that they were acting on behalf of their constituents, not only undermined the effectiveness of the Code, but engineered a reversal of its value and intent by curtailing diversity beyond areas of the policy’s intended application. What is not clear is why NSW Planning was complicit in approving LEP amendments that undermined the Code following the significant work it had invested in preparing and establishing it.

The greatest concern is perhaps not limited to the Code but a broader despair which is that sensible urban policies to enact social, economic and environmental reform for broad benefit were undermined by local interests. This poses far more serious questions about our capacity to address more significant challenges in the face of our existential environmental crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 NSW ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ implemented through State Environmental Planning Policy (Exempt and Complying Development Codes) 2008 (Codes SEPP).

5 Undertaken through our own investigations to translate Gross Floor Area as defined by the State Environmental Planning Policy (Exempt and Complying Development Codes) 2008 versus the definition applied to the LEP Standard Template definition (which excludes external wall thicknesses in its calculation).

6 Assessment undertaken through our own repeated testing/feasibilities in seeking suitable sites for a demonstration project.

7 By way of example, a comparison between the R2 Land use table across dates following the Code’s application to the Ryde Council LGA [https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/2021-02-01/epi-2014-0608#pt-cg1.Zone_R2 (01/02/2021) versus https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/2021-01-22/epi-2014-0608#pt-cg1.Zone_R2 (22/01/2021)] identifies the deletion of ‘multi dwelling housing’ from the Permitted with Consent table.