ABSTRACT

Rural and small town New Zealand is undergoing significant demographic and economic transitions. Steady out-migration, economic change and population aging since the 1980s/1990s catalysed the ‘zombie town’ discourse. This parallels the rise of rural multiculturalism as a new multi-ethnic demographic makeup is distinctly visible due to diversification of immigration policies responding to regional labour and skills shortages, amenity migrations, and counterurbanisation. While having the potential to restore regional economic and cultural vibrancy, these changes lead to issues related to integration challenges for migrants as well as tensions in host communities regarding diminishing rural amenities, lifestyles, and exhaustion of the limited rural infrastructure base. Some of these dynamics have gained new momentum due to COVID-19-induced disruptions, e.g. border closure. These are occurring at the same time as broader economic, environmental and planning policy shifts disrupt rural realities and opportunities. This commentary presents initial evidence from a larger study and discusses emerging discourses related to regional New Zealand in five thematic areas – demographic disruptions and new mobilities, emerging small town realities beyond economic migration, impacts of COVID-19, economic development, and the changing governance and planning landscape. In particular we highlight the need to recognise the emerging rural multiculturalism in small town planning and development, which received little attention in the past due to planning’s historical ‘large city’ bias and other local constraints.

Introduction

Rural and small town Aotearoa New Zealand has experienced significant demographic, economic and structural changes in the last five decades (Brabyn Citation2017; Spoonley Citation2020), which have significantly transformed rural and small town livelihoods, and the role that these areas play within broader New Zealand society. At one level, rural New Zealand experienced visible demographic transitions as the population aged, and historical urbanisation trends led to rural depopulation throughout much of the late twentieth century. In parallel, more liberal immigration policies since the 1990s (Liu et al. Citation2022), combined with recent local labour and skills shortages in primary and secondary industries in regional areas, have diversified their relatively homogeneous demographic makeup by attracting international migrants to these sectors. At another level, local governance and economic restructuring (Conradson and Pawson Citation1997, Citation2009; Pawson and Scott Citation1992; Scott and Pawson Citation1999) and new environmental regulations (Watson and Perkins Citation2022) have compounded the challenges the regions have faced since the 1970s following the neo-liberal reforms and the associated erosion of subsidies (Cloke and Le Heron Citation1994; Le Heron and Pawson Citation1996). Against this backdrop, this commentary makes a modest attempt to highlight two major sets of issues: one, the diverse interplay between the social and economic impacts of migration and cultural diversity in small, rural communities and secondly, the challenges these places face in areas of development, planning and governance.

The commentary stems from the authors’ involvement in a recently initiated multi-country project exploring immigrant retention capacities of small and mid-sized cities in Australia, Canada and New Zealand.Footnote1 International migration to these countries is typically perceived as an urban phenomenon, with most immigrants settling in conventional ‘gateway’ cities (Zhang and Crothers Citation2013; Friesen Citation2012). Despite proactive immigration policies, such as skill-based visa schemes to complement regional skill shortages (McDonald Citation2017), smaller and remote centres have usually struggled to attract and, even more so, retain immigrants due to these places failing to meet their long-term needs (Stump Citation2019). At a different level, there have been claims of new rural/regional revival through internal and amenity migration (Argent et al. Citation2010) and particularly counterurbanisation in recent time (Klocker et al. Citation2021),Footnote2 which are mostly because of community reactions to various emerging crises in large centres resulting from increasing housing unaffordability (Costello Citation2009) and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic (Dadpour and Law Citation2022; McManus Citation2022).

Although certain types of international (e.g. seasonal and temporary labour) migration have been deemed increasingly desirable due to their potential contribution to regional economies, immigrant experiences have been unequal in the intersections of gender, national identities and legislation that determine the ‘continuum of migration status and associated rights’ shaping both migrants’ performances in everyday settings and treatment to them in workplace (Collins Citation2020; Collins and Bayliss Citation2020). A more conservative perception is that immigrants are disrupting the ‘non-cosmopolitan’ image of the regional areas with their diverse cultural and spatial consumptions, which have often triggered anti-immigrant sentiments and political actions (Pritchard and McManus Citation2000; Strijker, Voerman, and Terluin Citation2015) which have had flow-on effects on immigrant acceptance, social tension and integration challenges. Recent studies have alluded to the perceived negative impacts new mobilities have on regional towns as they put pressure on the limited health and education services of small towns, which then generates uneasiness and tension in the existing communities (Crommelin et al. Citation2022). Despite the visible concentration of immigrants diversifying, contributing to and to some extent being disruptive to the region, how to plan in them with a focus on immigrant-led multiculturalism is not well understood and is a debate this commentary opens up the conversation about.

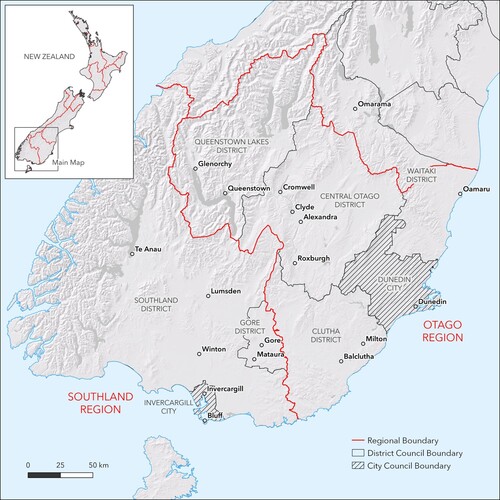

This commentary primarily relies on secondary literature – government, non-government and industry reports and online and offline media articles based in New Zealand to support the claims about its changing regional areas. It also uses qualitative evidence that we gathered through semi-structured interviews and participant observations from the Otago and Southland regionsFootnote3 (see ) during June 2021 to May 2022. These regions and selected settlements within them were selected for study because of the significant changes apparent within them in recent decades, including demographic shifts, economic revival and the in-migration of new residents from overseas and urban areas. Twenty-five migrants of Samoan, Malay and Filipino backgrounds employed in the meatwork and freezing, dairy and agricultural and hospitality sectors were interviewed to understand their post-arrival and subsequent settlement experiences in the Otago-Southland regional towns. Following qualitative analysis of both the primary and secondary data, findings were organised in five thematic areas under two broad categories – (1) Small town mobilities and emerging multiculturalism and (2) Planning and development challenges in small towns. While the first three themes illustrate how the regions are experiencing changes and the degree to which they are experiencing unprecedented multiculturalism and ethnic diversity, the second set of themes illustrate the nature of regional economic development and various planning and governance changes. Looking forward, we argue that the demographic changes observed in these regions go beyond the ‘precarious rural cosmopolitanism’ discourse (Woods Citation2018a, Citation2018b) in European and Australian case studies and there is a need to recognise the increasing rural multiculturalism in development and planning to ensure more inclusive and sustainable small town futures. As such, we see rural and small town futures as being mediated through the interplay between economic and policy and shifts, occurring in parallel and in conjunction with changes linked to demographic change and in-migration in particular.

Small town mobilities and emerging multiculturalism

Theme 1: demographic disruptions and new mobilities

In common with many other OECD countries, the rural and small town population in New Zealand is aging, and these places are witnessing a rising median age, a falling birth rate and a growing inability to fill employment gaps, as an increasing percentage of the population retires. In parallel, nearly a third of small towns have experienced depopulation, while 85% of towns are ageing in demographic terms (Jackson and Brabyn Citation2017; Brabyn Citation2017).

The growing local employment crises have prompted local communities and local authorities to explore options to retain youth in their localities and attract new migrants. The town of Otorohanga, in the central North Island of the country, embarked on a youth retention scheme following the recognition that as more people retired, labour market gaps could not be filled by the shrinking school leaving population, particularly as so many young people left the town on completion of their schooling. This led to a local program that combines trades training with pastoral care and job placement in local industries and businesses to encourage school leavers to stay in the town and receive pastoral support to assist them with issues such as financial management, study skills and preparation for the workforce (OECD Citation2017).

Other places have actively sought to attract international migrants to address labour force shortages which can no longer be addressed locally. Our initial research established that these initiatives are often industry led. Factories such as meat-packing plants in the Southland Region for example, have set up migrant support programs to attract new workers and settlers to their towns and industries, often from single islands in the Pacific, such as Samoan workers moving to the small town of Balclutha. Similar trends were observed in Mataura and Winton, where large concentrations of Malay and Filipino migrants were drawn to the meatwork and dairy industries respectively. In other cases, local or regional authorities have set up migrant support and settlement schemes to encourage both labour in-migration and retention (Tohill Citation2017, Citation2018).

In addition to industry-led migration support schemes, it is equally apparent that rural New Zealand has experienced a significant level of cultural and ethnic diversity in the last two decades as a result of conscious choices made by foreigners to move and settle in rural New Zealand where employment gaps exist, particularly following changes in the migration rules to allow in a more diverse range of immigrants (Rawlinson et al. Citation2013; Friesen Citation2015). This is most apparent in sectors such as the dairy and horticulture industry but also in the hospitality and small-town retail sectors, where opportunities have attracted significant numbers of migrants from SE Asia, the Pacific Islands, South Africa and South America (Friesen Citation2017).

These changes are clearly leading to more diversified national and regional populations (Friesen Citation2015). In turn, examination of data from our study area in Southland and Otago suggests that the ethnic population of the country and the study regions has changed significantly in recent years (see ).

Table 1. The composition of the resident population (in numbers and %) in terms of ethnicity, 1996, 2018 and 2023 estimate.Table Footnotea

The net result is a significant change in rural and small town society from one dominated almost exclusively by people of European descent and Māori to a far more diverse social and cultural mix which has not been without tensions. Challenges migrants have experienced have been partially offset by the role faith-based and other support groups play in helping to provide a ‘sense of home’ for new communities while also trying to encourage integration.

Theme 2: more than farming realities, beyond just labour migration

The neo-liberal reforms and the associated loss of farm subsidies and access to the previously guaranteed UK market from the 1970s, dealt a severe blow to New Zealand farming which took many years to recover from and caused severe economic and social distress in rural New Zealand (Bell Citation2014). Gradually, over time, consolidation of farming units, corporatisation and the growth in significance of dairy, viticulture and the fruit industry has seen significant growth in the sector. In parallel, the establishment of new markets and intensification have led to clear evidence of rural and agricultural revival. Arguments about a move from productivist to multi-functional agriculture hold some merit, particularly in areas which have diversified into new economic activities such as wine tourism, niche market production and lifestyle activities (Perkins, Mackay, and Espiner Citation2015). In the Australasian context, it has been noted that such transitions are also accompanied by increasing consumption-based activities, amenity migration and environmental and heritage protection (Holmes Citation2006). Of parallel significance, productivity changes have been noted in rural South Island as a result of the high returns which the dairy industry has been able to secure as a result of high demands from Asia. Significant intensification and industrialisation of dairy production and processing have been locally referred to as agricultural ‘super-productivism’, which has generated high demand for labour and niche skills (Roche and Argent Citation2015; Mackay and Perkins Citation2019).

Growing labour demand when overlain by population aging and outmigration has created workforce shortages which, as our emerging research shows, is partially being filled by new, international migrants. However, at present, the sector is struggling from historic debt as well as a host of legislative (e.g. freshwater, planning, etc.) reforms that are underway which require the sector to reduce its carbon footprint and its impact on river health. Historically high availability of freshwater has sustained New Zealand’s energy and economy, including agriculture, horticulture, tourism, and forestry (Land and Water Forum Citation2015). But increasing stressors from climate change, contamination and consumption in water-dependent industries, particularly the meat and dairy industries represents a key challenge to freshwater quality (Armoudian and Pirsoul Citation2020). Rising tensions with the state over these issues are increasing social stress in the country, compounding the long-term challenges which the sector faces.

In parallel, from 2000 onward, the Otago and Southland regions have experienced significant levels of ethnic diversity due to the arrival of new migrants of minority ethnic backgrounds, who were both filling the gaps left by historic population contraction and also by newly expanded economic activities. Our study participants, the Malay, Samoan and Filipino communities took on interesting life courses since their arrival at Mataura and Roxburgh, Balclutha and Invercargill respectively. Initially, they took on the typical labour migration pathway by being drawn to the primary (e.g. agriculture) and secondary functions (e.g. dairy, meat processing and freezing works, agricultural machinery, etc.). Over time, these communities have diversified their engagement in other sectors (e.g. hospitality and healthcare) as they could reskill themselves because of the availability of local training infrastructures, in this case, the Southern Institute of Technology ((a)), which is the Australian TAFEFootnote4 equivalent. Overall, from a place-based perspective, these communities were found to rely on the opportunities offered by the region that include multiple small towns and farming districts.

Figure 2. (a) The Southern Institute of Technology at Invercargill; (b) The church at Mataura now converted into Mataura Masjid (mosque). Source: Authors.

Greater ethnic diversity in small towns has warranted support for migrants through formal education in the labour sector as well as cultural support for newcomers to feel welcome. Local Councils, various local organisations, such as Great South, Multicultural Councils, Reach and Teach, Mar Colombia and local churches are providing a range of services (e.g. counselling, financial advice, language training, organising cultural events, etc.) so immigrants and refugees can comfortably settle in. Notably, these communities also have self-organised non-formal initiatives that provide tailored support based on faith. For example, Filipino community members in Invercargill have formed groups based on church denominations which encourage various cultural and recreational activities. The dispersedly located Malay communities in the region have recently purchased a church at Mataura and converted it into a mosque ((b)). Malay families from Mataura, Invercargill, Roxburgh and Queenstown use the mosque for monthly social gatherings and to avail religious education for their children.

Theme 3: COVID-19 and counterurbanisation

While it is potentially too early to fully gauge the impact which COVID-19 has had on urbanisation patterns, it is apparent that pre-existing processes of counterurbanisation have been extended. High costs of urban living, the ability of increasing numbers of people, even in state employment (e.g. the Ministry for the Environment) to work remotely and the extension of fibre networks have been linked to relocation of individuals from the cities for several years. COVID-19 and the requirement that many people had to work remotely have extended this practice. Preliminary evidence from Stats NZ estimates suggests that in the period up to March 2022, Auckland actually lost people for the first time ever (a modest fall of 0.1% after an average growth of 1.8% for many years), while smaller places in what are perceived as attractive areas are still growing (Stats NZ Citation2022). At the same time, during 2020/21, skills shortages in the agricultural sector became visible due to COVID-19 related entry restrictions on seasonal migrants (Collins Citation2021). This signalled the weakness of New Zealand’s immigration regime that historically promoted high levels of temporary mobility without adequate long-term settlement and inclusion opportunities in regional areas. Similar stresses were evident in hospitality and tourism sectors in places like Queenstown and Invercargill due to short supply of skilled workforce. Many migrant workers in Southland who were on temporary work visas were left in limbo as Immigration NZ stopped processing visa applications for skilled residency and (Steyl Citation2021). Later in 2021, a one-off resident visa for onshore migrants induced some certainty as employers could retain skilled staff (Williams Citation2021).

Particularly in the South Island, places, which have suffered from economic loss associated with COVID-19 pandemic, are now regenerating their spaces in new ways by reimagining themselves beyond being just the hinterland of major urban hubs (e.g. Queenstown) for both temporary (e.g. tourism- and education-related) and long term mobilities. For example, Timaru (Canterbury region) in the South Island, which is much like a transit hub between Christchurch and Dunedin, is now reimagining tourism with new and more effective administrative arrangements and place promotion tactics, supported by extra-local funding (Perkins and Mackay Citation2022).

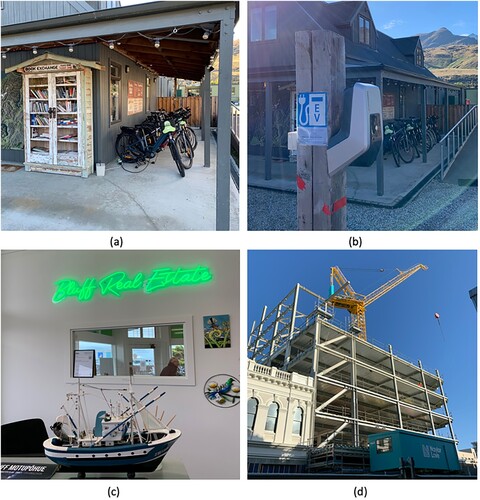

Our fieldwork during 2021–2022 shows new infrastructure developments for promoting sustainable tourism in the Otago and Southland regions. For example, remote places like Glenorchy have equipped their small commercial hubs with electric bike sharing services ((a)) and new electric vehicle EV charging stations ((b)). After the first phase of COVID-19, waves of in-country migration took place (Olsen Citation2020). It was also evident in our interviews with local business operators at Bluff, Glenorchy and Oamaru, where people from large urban centres (e.g. Auckland, Christchurch and Queenstown) relocated by June 2021. To cater to these new migrant needs, for example, in Bluff, a local cafe took on the new entrepreneurial role of the local real estate agent ((c)). Invercargill, a somewhat secondary hub in relation to Queenstown or Dunedin, is transforming rapidly with the regeneration of its city centre ((d)), including a 513 hectares industrial master plan (in progress), one of the most significant infrastructure projects the city has seen in recent times (Harding Citation2022).

Planning and development challenges in small town

Theme 4: small town economic development realities

As is common in most OECD countries, small towns are following highly divergent trajectories. One group, the traditional and often more remote service and extractive towns – based on farming, timber, mining and fishing have generally experienced economic and population loss as resources have run out, farming was mechanised and populations have contracted. Another group – either because of proximity to the cities or their location in areas of natural beauty have boomed as a result of tourism, retirement and second homes (Perkins, Mackay, and Espiner Citation2015). In the latter case, places such as Queenstown have struggled to manage growth, supply enough affordable housing, and address genuine labour force gaps. COVID-19 did, however, deal a severe blow to tourism-dependent towns, which may either prove to be short or long-term in nature. In the case of the small tourism dependent towns on the West Coast of the South Island, there are reports of a 20% loss of population because of near disappearance of international tourism (Development West Coast Citation2021).

For the first group of towns, the term ‘zombie towns’ (Eaqub in Laird Citation2014) is now used in the country which reflects on both the significant losses and often physical dilapidation which these places now display and the popular perception regarding non-urban New Zealand (Laird Citation2014). This reality has been a cause of political concern and helped motivate a degree of state investment in rural/regional New Zealand from the Provincial Growth Fund, which allocated $1 billion per annum to projects in these areas from 2018 to 2020 (Connelly, Nel, and Bergen Citation2019). This amount was significantly reduced following the political change in 2020. While it would be difficult to argue that the Fund reversed the fortunes of zombie towns and struggling rural areas, support for new tourism ventures, cycle trails, infrastructure and tree planting will have had some selective impact. That said, many areas, particularly those with large Māori populations, are underperforming in economic terms through historical disadvantage and the lack of new investment, which exacerbates the difference between the ‘boom’ towns of Otago and the northern Bay of Plenty and the more marginalised areas of Northland and East Cape.

There is significant contribution of the growing migrant proportions visible in Otago and Southland to local economic development. The Regional Seasonal Scheme (RSE scheme), which allows a set number of agricultural workers, primarily from Pacific Island states to gain short-term and often seasonal work visas was crucial to the development of the horticulture and viticulture industries in Central Otago which has helped support struggling rural economies (Keen Citation2009). Temporary work visas became important in places like Queenstown’s hospitality industry. Recognising the role of migrants in the regional economy, various employment sectors learned the treatment of migrants in workplace settings through programs which were actively supported by government agencies and key regional economic development actors, such as Great South in Invercargill. As our interviews revealed, there was a greater emphasis on community development alongside economic through assembling support networks both horizontally and vertically, within territorial boundaries and nationwide to connect ministries, local governments, local and international NGOs, faith-based groups and even migrants’ own groups.

Theme 5: governance and planning reforms and challenges

Local government reforms from the 1980s reduced the number of local authorities, which is frequently cited as a cause for the loss of identity, voice and access to governance channels in rural and small towns in New Zealand (Nel Citation2014). A major challenge for local government in the country is that, unlike the case in many other parts of the world, in economic terms, they are largely self-funded entities which require them to meet local service needs almost entirely from the local rate base. This causes severe stress in smaller centres when required to meet national guidelines in terms of service provision. It also inhibits local capacity to respond to broader issues of economic and social change (Nel Citation2014; Jackson, Nel, and Connelly Citation2020).

To some degree and with significantly varying degrees of success, the gap mentioned above is partially addressed through local business and community actions. Such actions include the role farming communities play in fundraising to provide social and sports facilities in their nearest service centre, community-led effort to fund health facilities following downscaling of state support, such as happened in the town of Lawrence, or private sector initiatives to attract business to towns, the promote main-street revival and town promotion, such as in Tirau and Reefton (Nel, Connelly, and Stevenson Citation2019). Other actions include small town and town centre development initiatives and marketing in places such as Oamaru and Timaru driven by local business and community action (Perkins et al. Citation2019; Levy et al. Citation2021).

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), the key legislation guiding planning in New Zealand, in principle, with its primary focus on managing ‘effects’ (Gurran, Austin, and Whitehead Citation2014; Memon and Gleeson Citation1995; Perkins and Thorns Citation2001) of resource use, has limited recognition of the benefit of ‘urban’ planning and development in the last three decades, let alone that of regional small- and mid-sized centres. The more recent National Policy Statement on Urban Development NPS-UD, introduced in 2016, primarily focuses on Tier 1 and Tier 2 urban environments, reinforcing the historical neglect of urban planning in small towns (MoHUD Citation2021). An ‘urban environment’ in the NPS-UD has an explicit reference to places with urban attributes and with ‘a housing and labour market of at least 10,000 people’ (MoHUD Citation2021). Within this national policy environment, places like Bluff, Mataura, Roxburgh, or Lawrence, with a few hundred to thousands of populations, slip through the cracks of such definitions and miss appropriate planning interventions.

In 2023, the new Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA) will replace the RMA (MfE Citation2022). An exposure draft of the NBA was released in June 2021 for public consultation and later in November 2022 the bill was released for further submissions from stakeholders (e.g. NZPI, local governments) (Parliamentary Counsel Office Citation2022). Under the NBA, there will be a mandatory set of national policies and standards, and the existing 100-plus RMA council planning documents will be reduced to about 14 based on catchment boundaries (Parker Citation2021). Recent research shows that within this centralised resource management regime under the NBA, small towns and their local governments may suffer due to reduced local institutional autonomy, the distancing of elected representatives, and fewer opportunities for community participation (Kenneally Citation2021).

In parallel, the ongoing freshwater management policy shifts have significant implications for small towns creating uncertainty around water allocation for farmers (Watson and Perkins Citation2022), whose survival is crucial for the sustenance of many town centres that thrive on the agricultural function of the catchments. The 2017 ground breaking acknowledgement of the river system (e.g. Whanganui River) as a ‘legal person’ accords certain ‘guardianship and governance rights, but not property rights’, to Māori, who traditionally owned the river. Māori continue to agitate for the right to ‘own’ their water resources amid the government’s water law reform (Macpherson Citation2019). While the arrangement is supposed to bring significant changes to the conventional ways the environment and rivers are managed, the government must find ways to strengthen and maintain local community support in regional areas (O’Donnell and Macpherson Citation2019).

Looking forward

The commentary has highlighted five thematic areas to recognise the interplay between the social and economic impacts of migration in regional New Zealand, the increasing cultural diversity and their implications for economic development, which will also be shaped by the nationwide changing planning and governance landscape. Looking forward, we caution about a few challenges. To begin, given the limited nature of state intervention, the weak financial status of many local governments, and the reality that market forces will selectively favour different regions and economic activities, it is unlikely that the gap between the boom towns and regions and the zombie towns and their hinterlands will close at any time soon. Then, farming areas and communities are in for hard times as debts mount, environmentally related restrictions (e.g. new freshwater governance) are mandated and future risks, such as climate change, plant and animal disease, biosecurity and zoonotic tensions (Lal et al. Citation2015) are experienced, and responses negotiated. Furthermore, small town differences will likely grow given the boom some places (such as Invercargill) have experienced, despite the COVID-19 setback, the nature of local government funding and limited state support. Overlying this, the population of rural and small-town New Zealand is likely to age significantly, and many areas will continue to experience population and economic loss. That said, in many of the more productive areas such as Waitaki and Invercargill, population loss is being addressed by the arrival of new migrants from diverse ethnic backgrounds. This will require receiving areas to be more tolerant towards newcomers and provide appropriate support and retention programs to maintain economic vitality and liveability. Yet, within a more centralised planning regime, with only 14 regional plans to govern the whole country, many small towns may find themselves further disempowered and excluded in the post-RMA era and, therefore, will struggle to devise migrant-inclusive, ethnically diverse localised economic and spatial plans. On top, some of their sheer smallness in terms of having a very low population base compared to major urban areas often puts them as the outlier in the national urban planning and policy agenda.

Recognising the preceding interplay of forces which will collectively shape rural areas and small towns, we also argue that a particularly important reality and line of research going forward will be the investigation of the significance of the new wave of rural multiculturalism that has taken place since the post-1990s diversified immigration policies primarily in response to the regional skill shortages. While migrants’ contribution to small town sectors are well acknowledged (Trafford and Tipples Citation2012), their diverse lived experiences and how small towns shape those is little understood. Future research should take empirical place-based approaches to examine the immigrant and newcomer led ‘actually occurring small town cosmopolitanism’ (after Woods Citation2018b). It is worth noting that cosmopolitanism flourishing in New Zealand’s non-metropolitan settings is not new as the regions have been sites of exchanges and transits in the past through European’s arrival to the country in the 1800s and successive major waves, including the significant ones after the World Wars. This followed a long history of Māori movement through and occupation of these areas for trade, settlement, and family reunion. Against this backdrop, it is being evident that in recent times the new mobilities could best be described as a rise in rural multiculturism and multi-ethnicity in southern New Zealand. This poses an opportunity to theorise what multiculturalism means in terms of (minority ethnic) migrants’ rights and belonging to the country where since the 1970s, the government has moved to create a society that is more biculturalFootnote5 in practice and yet when many disputes (e.g. over land and resource access) between the Crown and Māori are still not settled yet. This means, for new migrants in New Zealand, the actually occurring rural cosmopolitanism is more than just the ‘silent bargain’ for economic necessity over social integration that are observed elsewhere (Torres, Popke, and Hapke Citation2006; Schech Citation2014; Woods Citation2018b). New Zealand’s version of rural cosmopolitanism should therefore be understood as a ‘decolonial’ and ‘cultural’ project as much as it is considered a ‘political and ethical’ project elsewhere (Woods Citation2018b). Planning in New Zealand’s rural and small towns needs to recognise planning for the growing multiculturalism and ethnic diversity and how these then translate into areas of economy, environment, and the ‘Treaty’.Footnote6 All these are unique challenges ahead; however, these may give an opportunity to develop a new agenda for small town planning and urbanism that better caters to the unique realities New Zealand’s regions face.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to two anonymous reviewers for detailed guidance and Laura Crommelin for her astute editorial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The first author is the co-applicant and New Zealand lead of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) funded Partnership Development Grant to undertake a comparative study on immigration to small and mid-sized cities in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The second author is a ‘collaborator’ in this project. The project is novel in that it goes beyond the consideration of economic drivers underpinning international migration to small and mid-sized cities, to examine how life course and place-based factors influence the experiences and decision-making of immigrants (see details in CERC Citation2022).

2 There have been different interpretations of coutnerurbanisation (see McManus Citation2022). Following Klocker et al. (Citation2021), this commentary associates counterurbanisation with population mobility to rural areas.

3 New Zealand’s local government system comprises two complementary sets of local authorities – regional and territorial authorities, i.e. the city and district councils. Regional council jurisdictions are demarcated based on the catchment boundaries () and their functions overlap with those of territorial councils. In contrast, city councils serve a population of more than 50,000 in a predominantly urban area.

4 Technical and Further Education TAFE NSW is Australia’s largest vocational education and training provider based in New South Wales.

5 In New Zealand the term bicultural refers to Māori and non-Māori with an acknowledgement that Māori as tangata whenua (the people of the land with special relationship to the land) should have equal rights, protection and status.

6 The Treaty of Waitangi were written and signed by around 500 rangatira (Māori tribal chiefs) and representatives of the British Crown in 1840. The Treaty thus put in place a partnership between Māori and the British Crown.

References

- Argent, Neil, Matthew Tonts, Roy Jones, and John Holmes. 2010. “Amenity-Led Migration in Rural Australia: A New Driver of Local Demographic and Environmental Change?” In Demographic Change in Australia's Rural Landscapes: What Does It Mean for Society and the Environment?, edited by G. Luck, R. Black, and D. Race, 23–44. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Armoudian, M., and N. Pirsoul. 2020. “Troubled Waters in New Zealand.” Environmental Communication 14 (6): 772–785. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1727547.

- Bell, Claudia. 2014. “When the Farm Gates Opened: The Impact of Rogernomics on Rural New Zealand.” New Zealand Sociology 29 (2): 135–136.

- Brabyn, Lars. 2017. “Declining Towns and Rapidly Growing Cities in New Zealand: Developing an Empirically-Based Model That Can Inform Policy.” Policy Quarterly 13: 37–46.

- CERC. 2022. “SSHRC Awards Partnership Development Grant to Support Research into Migration Potential of Small and Mid-Sized Cities.” CERC in Migration and Integration, June 17. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.torontomu.ca/cerc-migration/news/2022/06/partnership-development-grant-for-small-and-mid-sized-cities-research/.

- Cloke, Paul, and R. Le Heron. 1994. “Agricultural Deregulation: The Case of New Zealand.” In Regulating Agriculture, edited by P. Lowe, T. Marsden, and S. Marsden, 104–126. London: Fulton.

- Collins, Francis L. 2020. “Legislated Inequality: Provisional Migration and the Stratification of Migrant Lives.” In Intersections of Inequality, Migration and Diversification - The Politics of Mobility in Aotearoa/New Zealand, edited by R. Simon-Kumar, F. L. Collins, and W. Friesen, 65–86. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Collins, Francis L. 2021. Temporary Migration in Invercargill and Queenstown amidst the COVID-19 Global Pandemic, CaDDANZ, Capturing the Diversity Divident of Aotearoa/New Zealand, Brief No. 12. Hamilton: University of Waikato.

- Collins, Francis L., and T. Bayliss. 2020. “The Good Migrant: Everyday Nationalism and Temporary Migration Management on New Zealand Dairy Farms.” Political Geography 80: 102193. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102193.

- Connelly, Sean, Etienne Nel, and Samuel Bergen. 2019. “Evolution of New Regional Development Interventions in New Zealand: An Analysis of the First Year of the Provincial Growth Fund.” New Zealand Geographer 75 (3): 177–193. doi:10.1111/nzg.12233.

- Conradson, David, and Eric Pawson. 1997. “Reworking the Geography of the Long Boom; the Small Town Experience of Restructuring in Reefton, New Zealand.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 29 (8): 1381–1397. doi:10.1068/a291381.

- Conradson, David, and Eric Pawson. 2009. “New Cultural Economies of Marginality: Revisiting the West Coast, South Island, New Zealand.” Journal of Rural Studies 25 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.06.002.

- Costello, Lauren. 2009. “Urban–Rural Migration: Housing Availability and Affordability.” Australian Geographer 40 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1080/00049180902974776.

- Crommelin, Laura, Todd Denham, Laurence Troy, Jason Harrison, Hulya Gilbert, Stefanie Dühr, and Simon Pinnegar 2022. “Understanding the Lived Experience and Benefits of Regional Cities.” AHURI Final Report. doi:10.18408/ahuri7126301.

- Dadpour, Rana, and Lisa Law. 2022. “Understanding the ‘Region’ in COVID-19-Induced Regional Migration: Mapping Cairns across Classification Systems.” Australian Geographer 53 (4): 425–443. doi:10.1080/00049182.2022.2059128.

- Development West Coast. 2021. Glacier Country Report. Development West Coast. Greymouth: Development West Coast.

- Friesen, Wardlow. 2012. “International and Internal Migration Dynamics in a Pacific Gateway City: Asian Migrants into and out of Auckland.” New Zealand Population Review 38: 1–22.

- Friesen, Wardlow. 2015. “Beyond the Metropoles: The Asian Presence in Small City New Zealand.” Asia New Zealand Foundation, October 28. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Beyond-the-Metropoles-The-Asian-presence-in-small-city-New-Zealand.pdf.

- Friesen, Wardlow. 2017. “Migration Management and Mobility Pathways for Filipino Migrants to New Zealand.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 58 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1111/apv.12168.

- Gurran, Nicole, Patricia Austin, and Christine Whitehead. 2014. “That Sounds Familiar! A Decade of Planning Reform in Australia, England and New Zealand.” Australian Planner 51 (2): 186–198. doi:10.1080/07293682.2014.890943.

- Harding, Evan. 2022. “Masterplan a Work in Progress for Massive Industrial Development Near Invercargill.” Stuff, July 29. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/129402620/masterplan-a-work-in-progress-for-massive-industrial-development-near-invercargill.

- Holmes, J. 2006. “Impulses towards a Multifunctional Transition in Rural Australia: Gaps in the Research Agenda.” Journal of Rural Studies 22 (2): 142–160. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.006.

- Jackson, Natalie, and Lars Brabyn. 2017. “The Mechanisms of Subnational Population Growth and Decline in New Zealand 1976-2013.” Policy Quarterly 13: 22–36.

- Jackson, Tony, Etienne Nel, and Sean Connelly. 2020. “A Comparison of Resource Equalization Processes for Subnational Rural Governance and Development: Case Studies of England, Scotland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.” In Open Government: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, edited by Information Resources Management Association, 2140–2172. Information Resources Management Association, USA: IGI Global.

- Keen, Donna. 2009. “The Interaction of Community and Small Tourism Businesses in Rural New Zealand.” In Small Firms in Tourism: International Perspectives, edited by R. Thomas, 139–152. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Kenneally, Joshua. 2021. “Local Democracy & Resource Management Reform.” Master of Planning Thesis published by School of Geography. University of Otago.

- Klocker, Natascha, Paul Hodge, Olivia Dun, Eliza Crosbie, Rae Dufty-Jones, Celia McMichael, Karen Block, et al. 2021. “Spaces of Well-Being and Regional Settlement: International Migrants and the Rural Idyll.” Population, Space and Place, e2443. doi:10.1002/psp.2443.

- Laird, Lindy. 2014. “Zombie Town Jibe a Wake-Up Call.” The Northern Advocate, September 29, 2014. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/northern-advocate/news/zombie-town-jibe-a-wake-up-call/JF5S2JPMET7NN2VCJRBWE7IFPQ/.

- Lal, Aparna, Adrian WT Lill, Mary Mcintyre, Simon Hales, Michael G. Baker, and Nigel P. French. 2015. “Environmental Change and Enteric Zoonoses in New Zealand: A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 39 (1): 63–68. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12274.

- Land and Water Forum. 2015. The Fourth Report of the Land and Water Forum. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/assets/WRC/Council/Policy-and-Plans/HR/S32/E3/Land-and-Water-Forum-2015-The-Fourth-Report-of-the-Land-and-Water-Forum.pdf.

- Le Heron, R. B., and E. Pawson, eds. 1996. Changing Places: New Zealand in the Nineties. Auckland: Longman Publishing Group.

- Levy, D., R. Hills, H. C. Perkins, M. Mackay, M. Campbell, and K. Johnston. 2021. “Local Benevolent Property Development Entrepreneurs in Small Town Regeneration.” Land Use Policy 108: 105546. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105546.

- Liu, Linagli, Robert Didham Sally, Xiaoan Wu, and Zhihan Wang. 2022. “The Making of an Ethnoburb: Studying Sub-Ethnicities of the China-Born New Immigrants in Albany, New Zealand.” Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 56: 426–458. doi:10.1007/s12124-021-09672-2.

- Mackay, M., and H. C. Perkins. 2019. “Making Space for Community in Super-Productivist Rural Settings.” Journal of Rural Studies 68: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.012.

- Macpherson, E. J. 2019. Indigenous Water Rights in Law and Regulation Lessons from Comparative Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McDonald, Peter. 2017. “International Migration and Employment Growth in Australia, 2011–2016.” Australian Population Studies 1 (1): 3–12. doi:10.37970/aps.v1i1.8.

- McManus, Phil. 2022. “Counterurbanisation, Demographic Change and Discourses of Rural Revival in Australia During COVID-19.” Australian Geographer 53 (4): 363–378. doi:10.1080/00049182.2022.2042037.

- Memon, P. Ali and Brendan J. Gleeson. 1995. “Towards a New Planning Paradigm? Reflections on New Zealand's Resource Management Act.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 22 (1): 109–124. doi:10.1068/b220109.

- MfE (Ministry for the Environment). 2022. “Overview of the Resource Management Reforms.” Last updated June 20. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/rma/resource-management-system-reform/overview/.

- MoHUD (Ministry of Housing and Urban Development). 2021. “Implementing the National Policy Statement on Urban Development.” December 21. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.hud.govt.nz/urban-development/national-policy-statement-on-urban-development/implementing-the-national-policy-statement-on-urban-development/.

- Nel, Etienne. 2014. “Responding Changing Fortunes: The Experience of Small Town New Zealand.” In Engaging Geographies: Landscapes, Lifecourses and Mobilities, edited by M. Roche, J. Mansevlet, R. Price, and A. Gallagher, 63–86. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing.

- Nel, Etienne, Sean Connelly, and Teresa Stevenson. 2019. “New Zealand's Small Town Transition: The Experience of Demographic and Economic Change and Place Based Responses.” New Zealand Geographer 75 (3): 163–176. doi:10.1111/nzg.12240.

- O’Donnell, E., and E. Macpherson. 2019. “Voice, Power and Legitimacy: The Role of the Legal Person in River Management in New Zealand, Chile and Australia.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 23 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1080/13241583.2018.1552545.

- OECD. 2017. Engaging Employers in Apprenticeship Opportunities: Making It Happen Locally. OECD Publishing.

- Olsen, Brad. 2020. “Kiwis Shifting from Cities to the Regions.” November 24. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.infometrics.co.nz/article/2020-11-kiwis-shifting-from-cities-to-the-regions.

- Parker, David. 2021. “RMA to Be Repealed and Replaced.” Media released on February, 2021. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/rma-be-repealed-and-replaced.

- Parliamentary Counsel Office. 2022. Natural and Built Environment Bill. Released on November 2022. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2022/0186/latest/whole.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_natural_resel_25_a&p=1#LMS501892.

- Pawson, Eric, and Gary Scott. 1992. “The Regional Consequences of Economic Restructuring: The West Coast, New Zealand (1984–1991).” Journal of Rural Studies 8 (4): 373–386. doi:10.1016/0743-0167(92)90051-7.

- Perkins, Harvey C., and Michael Mackay. 2022. “The Place of Tourism in Small-Town and Rural District Regeneration Before and during the COVID-19 Era.” The Journal of Rural and Community Development 17 (1): 17–31.

- Perkins, Harvey C., Michael Mackay, and Stephen Espiner. 2015. “Putting Pinot Alongside Merino in Cromwell District, Central Otago. New Zealand: Rural amenity and the Making of the Global Countryside.” Journal of Rural Studies 39: 85–98. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.03.010.

- Perkins, H. C., M. Mackay, D. Levy, M. Campbell, N. Taylor, R. Hills, and K. Johnston. 2019. “Revealing Regional Regeneration Projects in Three Small Towns in Aotearoa—New Zealand.” New Zealand Geographer 75 (3): 140–151. doi:10.1111/nzg.12239.

- Perkins, Harvey C., and David C. Thorns. 2001. “A Decade on: Reflections on the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Practice of Urban Planning in New Zealand.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 28 (5): 639–654. doi:10.1068/b2744.

- Pritchard, Bill, and Phil McManus. 2000. Land of Discontent: The Dynamics of Change in Rural and Regional Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Rawlinson, Philippa, Rupert S. Tipples, Isobel J. Greenhalgh, and Suzanne Trafford. 2013. Migrant Workers and Growth of the Dairy Industry in Southland, New Zealand, Centre of Excellence in Farm Business Management – One Farm Management. Lincoln: Lincoln University.

- Roche, M., and N. Argent. 2015. “The Fall and Rise of Agricultural Productivism? An Antipodean Viewpoint.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (5): 621–635. doi:10.1177/0309132515582058.

- Schech, S. 2014. “Silent Bargain or Rural Cosmopolitanism? Refugee Settlement in Regional Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40: 601–618. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.830882.

- Scott, Gary, and Eric Pawson. 1999. “Local Development Initiatives and Unemployment in New Zealand.” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 90 (2): 184–195. doi:10.1111/1467-9663.00060.

- Spoonley, Paul. 2020. The New New Zealand: Facing Demographic Disruption. Auckland: Massey University Press.

- Stats NZ. 2019. “2018 Census Place Summaries.” Accessed November 7, 2021. http://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/.

- Stats NZ. 2021. “1996 and 2018 Census.” Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.stats.govt.nz/topics/census.

- Stats NZ. 2022. “National Population Estimates.” Accessed July 30, 2022. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/national-population-estimates-at-31-march-2022/.

- Steyl, Louisa. 2021. Migrants Tire of Life in Limbo. https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/the-southland-times/20210902/281479279517433.

- Strijker, Dirk, Gerrit Voerman, and Ida Terluin, eds. 2015. Rural Protest Groups and Populist Political Parties. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Stump, Talia. 2019. “The Right Fit: Attracting and Retaining Newcomers in Regional Towns.” City to Country Project. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.34596.01927.

- Tohill, Mary-Jo. 2017. “Clutha District Failing to Attract Permanent Residents to Fill Hundreds of Jobs.” August 28. Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.stuff.co.nz/southland-times/news/95863549/clutha-district-failing-to-attract-permanent-residents-to-fill-hundreds-of-jobs.

- Tohill, Mary-Jo. 2018. “Silver Fern Farms Finegand Still Looking at Worker Accommodation Options.” October 23. Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.stuff.co.nz/southland-times/news/108032258/silver-fern-farms-finegand-still-looking-at-worker-accommodation-options.

- Torres, R. M., E. J. Popke, and H. M. Hapke. 2006. “The South's Silent Bargain: Rural Restructuring, Latino Labor and the Ambiguities of Migrant Experience.” In Latinos in the New South, edited by H. A. Smith, and O. J. Furuseth, 37–68. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Trafford, Sue, and Rupert Tipples. 2012. A Foreign Solution: The Employment of Short Term Migrant Dairy Workers on New Zealand Dairy Farms. L. University. https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10182/9064/Foreign%20solution%20-%20the%20employment%20of%20short%20term%20migrant%20dairy%20workers%20on%20New%20Zealand%20dairy%20farms%202012.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1.

- Watson, Niall, and Harvey C. Perkins. 2022. “The Politics of Water Governance in Central Otago, New Zealand: Struggling with a Nineteenth Century Legacy.” New Zealand Geographer 78 (1): 98–103. doi:10.1111/nzg.12333.

- Williams, Guy. 2021. One-Off Migrant Visa Decision Welcomed by Leaders. https://www.odt.co.nz/regions/queenstown/one-migrant-visa-decision-welcomed-leaders.

- Woods, Michael. 2018a. “Rural Cosmopolitanism at the Frontier? Chinese Farmers and Community Relations in Northern Queensland, c.1890–1920.” Australian Geographer 49 (1): 107–131. doi:10.1080/00049182.2017.1327785.

- Woods, Michael. 2018b. “Precarious Rural Cosmopolitanism: Negotiating Globalization, Migration and Diversity in Irish Small Towns.” Journal of Rural Studies 64: 164–176. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.014.

- Zhang, Zhiheng, and Charles Crothers. 2013. “Chinese Entrepreneurial Niches in the Immigrant and the Non-Immigrant Gateway Cities New Zealand.” New Zealand Sociology 28 (1): 83–100.