ABSTRACT

Child-friendly cities are places that support opportunities for children’s play and community connection in safe urban environments. A dominant practice in urban planning and design has been to separate people and their activities spatially (i.e., residential zones, learning zones, play zones) and this coincided with the remaking of cities around private vehicular travel which together necessitated carving out safe spaces for children play. This has meant that children’s play has been geared towards permanent equipment in fenced-off playgrounds or more formal educational settings. However, the inclusion of temporary play spaces in cities to support community engagement in the local environment is growing to combine urban design, play and community wellbeing initiatives. This paper documents the experiences of stakeholders of a temporary play space in an inner-city suburb of an Australian city. This work includes key perspectives of the architects and designers and local council members to evaluate how a 12-week activation of a temporary play space came into being and what can be learnt from this collaboration.

1. Introduction

The majority of the world’s children play in the cities where they live as they engage in their local environments (Malone Citation2015; Schlesinger et al. Citation2020). A dominant practice in urban planning and design has been the principle of functional zoning. This prevailing methodology has produced settlements characterised by separating and distributing different functions and activities across space – residential zones, learning zones and play zones (Henket Citation2022). Since the early twentieth century, this approach has privileged the design of cities around private vehicular travel, which necessitated carving out safe spaces for children to play. This segregation has meant that children’s play has been geared towards permanent equipment in fenced-off playgrounds. In contrast to the controlled permanence of modernist zoning, temporary play spaces in cities are a way to enact play-making, transforming areas that may not usually be thought of as play spaces (Bustamante et al. Citation2019). When designing temporary play spaces for children, key design principles are considered to ensure areas have access for community engagement through active play (Bustamante et al. Citation2019). This paper reports on developing a temporary play space in an inner-city suburb of an Australian city. The analysis of this temporary play space draws on both childhood education and architectural and urban design perspectives. Here, we use the term temporary playspace as a neutral term to invoke the relationship between an urban site, its resources and the broader context of place.

Temporary play spaces have been shared during the Covid-19 pandemic as a movement within cities was restricted in many countries (Russell and Stenning Citation2020). City councils became more responsive as the Covid-19 restrictions meant that outside contact with others in public spaces was imperative. These principles informed our project’s initial conception, space design and enactment to address the research question: What are stakeholders’ experiences in the design and delivery of a temporary urban playspace for children?

Underpinning the above question is de Certeau’s (Buchanan Citation2001) work that aimed to theorise ‘daily life in terms of empowerment’ for its participants (87). Two concepts are relevant to this study; strategies that reduce unpredictable elements creating an unyielding space and tactics that deliberately push through restrictive boundaries to subvert and change the order (Buchanan Citation2001). In cities, strategies are used by the people who have authority (developers, governments, etc.) to present the appropriate way of using space. However, people use tactics to subvert and creatively engage with their city in different and creative ways.

2. Background

Child-friendly cities are places that support opportunities for children's play and community connection in safe urban environments, although there is no single definition due to the diversity of cities (Malone Citation2015; Malone and Rudner Citation2017). United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), aligned with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, views child-friendly cities as places where children thrive in safe and supportive urban environments (UNICEF Citation2018). The sustainable development goals (SDGs) include several child-focused indicators related to play, learning and community. For example, SDG Target 4.1 refers to learning and quality education for children; specifically, SDG Target 4.2 relates to early childhood development. Moreover, child-friendly cities invoke children’s rights to citizenship (Smith Citation2015).

For urban designers, the design of urban spaces is seen as improving places for the people who inhabit the space (Carmona et al. Citation2010). Urban sociologist Oldenburg (Citation1991; Citation2002) argued that in cities, opportunities for gathering in urbanised areas for families and their children as they travel to and from their daily activities can be understood as a third place. This third place is defined as the spaces where people connect in and with their communities, the first place being the home, and the second place work (Carmona et al. Citation2010; Oldenburg Citation2002). It is the third place where people gather in cities and informally meet to drink coffee, shop, eat, socialise on the street (Oldenburg Citation1991; Citation2002) and, in this case, play. These third places enable sociability between people as they engage in informal activities, including play, that create a connection to place and people (Elshater Citation2017; Mehta and Bosson Citation2009). In these broader urban studies, notions of play have been seen to be an important way to reconceptualise the city. For example, Stevens (Citation2001) examined how urban spaces both encourage and allow for play – for both adults and children. This work points to more recent approaches and practices in Urban Design that have seen urban play as a performance generated by creative art practices. These practices emphasise the importance of urban play and highlight new modes of urban occupation that generate – if only temporarily – new sense-making in existing urban spaces (ON/OFF Collective Citation2017).

Malone's (Citation2013; Citation2016) study in an Australian regional city included a master-planned community (MPC) using input from children as ‘project advisors’ to find out their relationship to place and include their contributions in the design of the urban development. Imperative areas from the children's perspectives that support their play included places that: protect nature, create communities, allow active movement, promote learning, are safe and clean, value children and have pathways (Malone Citation2013). This study had genuine input from children aged between 4- and 11-years-old and demonstrated children's connection to place through access to and affordances of the play spaces.

Following these specific studies in Australia, in a related and broader socio-ecological analysis of child-friendly and sustainable cities, Malone and Rudner (Citation2017) emphasise the importance of freedom, mobility and risk. Rather than play, they focus on Children's Independent Mobility (CIM) across different communities in order to gain knowledge and assess the broad range of children's urban experience. They conclude the importance of understanding both the local and community contexts of the life-worlds of children. Rudner's (Citation2017) work has illuminated how urban designers and planners can learn how to engage children in planning processes. They argue that professionals often do not see children as equal or ‘legitimate’ stakeholders in either policy or practice, going on to argue that the key to alleviating this issue is to better educate planners about ethically engaging with children.

The diversity of childhood life-worlds and specific communities is evident in studies of play across the globe. For example, in the city of Cairo, Elshater's (Citation2017) study advocated for bottom-up principles in the consultation process that involve children, teenagers and their families in the planning of their neighbourhoods to support child-friendly cities. Their study took place over 12 months with 10–17-year-olds and their parents. Methods included interviews and workshops with officials that aimed to give voice to younger members of the community to hear their perspectives on ways to improve the spaces they inhabit. This study found urban design dimensions and the ‘users’ needs and attitudes in third places’ need to be considered to design child-friendly spaces (446).

Krishnamurthy's (Citation2019) study on public urban spaces that support child-friendly cities in The Netherlands looked at four different neighbourhoods in one city. The research investigated three urban spaces: the street, green spaces and play spaces through observations, interviews with parents and workshops with primary-aged children. The research found that there were key elements that supported child-friendly cities; central was how children's and families’ needs and interests were considered and articulated, which was a ‘bottom-up’ co-planning and design. Play spaces require thoughtful planning for children of different ages, as infant's and toddler's play differs from older children's play (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). Designated play spaces were valued in all neighbourhoods, although places for parents to wait or engage in were found to be absent (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). Undesignated play spaces with easy access were valued by children, and these incidental spaces invited imaginative explorations as they transformed the space. Traffic safety was a central concern for all families, and car-free zones were suggested by parents (Krishnamurthy Citation2019).

In America, temporary play spaces named Playful Learning Landscapes (PPL) encompass urban design and the science of learning (Umstattd Meyer et al. Citation2019). This is an approach related to Play Streets that require the temporary closure of roads in residential areas and involve minimal installations and flexibility (Umstattd Meyer et al. Citation2019). Nonetheless, PPL aim to provide opportunities for families, children and adults, to engage and interact in stimulating environments in the cities where they live with a focus on active play (Umstattd Meyer et al. Citation2019). Time in these spaces can include interactions with the place, objects, and people in the community where they can engage in play activities in the urban setting. Children's learning happens in formal schooling but also occurs all the time, including time and engagement in the city landscapes (Schlesinger et al. Citation2020). Thus, infusing playful learning uses multiple approaches focused on child-directed play, which includes free play, guided play, and games designed for children of various ages (Weisberg et al. Citation2016). Designing the space and any objects to support learning outcomes for children needs to: promote active play; engage children; be meaningful for the community and be socially interactive and joyful (Hassinger-Das et al. Citation2021).

PPL combine learning through play and architectural design (Bustamante et al. Citation2019) was the genesis for the temporary play space reported in this paper alongside loose parts theory (Nicholson Citation1971). Nicholson's (Citation1971) theory of loose parts was used in the design to create an environment where children ‘invent, construct, [and] evaluate’ using open-ended materials that move and change in response to their play needs (31).

3. Context of place

The 12-week activation of the playspace we are reporting on was located in a suburb 6 km from a major Australian city. The geographical region is a decile 3 (1 lowest and 10 highest possible decile) for socioeconomic status according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2018). The location was a square that had already been identified by the local council as a ‘problem area’ because of the consistent use by vulnerable community members who frequently engaged in behaviour that included drug taking (including injectables), drinking, public urination, vandalism of local businesses and confronting people passing by. The space was located between a main shopping mall and train station, and the local council acknowledges it was a space where local business owners and residents did not always feel safe.

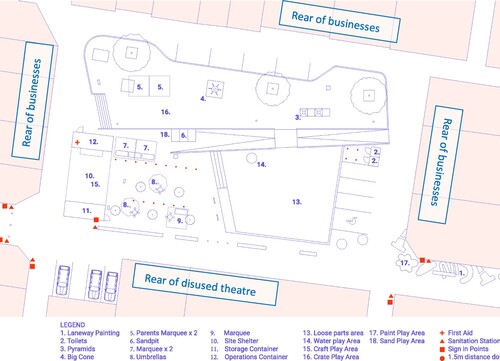

The space was rectangular with one long side of the space enveloped by a tall brick wall of an old disused theatre, and the other three sides had the rear of buildings that operated businesses onto the adjoining streets (see ). This boundary created a square with an internalised green space encircled on all four sides by roads providing access to the rear of businesses for loading, logistics and public car parking. This meant there was no business activity facing onto the space; the back doors allowed access to rubbish bins and traffic. Access to the square was via an east–west laneway to the main pedestrianised shopping mall, or via two north–south laneways that terminate at the square. As a result of this configuration, there are no view lines from the adjacent streets into the space and people had to walk down narrow laneways to access the square. In the past, the local council had attempted several upgrades of the square in response to resident and local business feedback wanting the space to be activated. These upgrades had included formal landscaping works, installed public art and organised one-off events (e.g., cinemas, markets).

4. Materials and methods

The paper is drawn from a qualitative case study (Yin Citation2018) to gain insights into the design principles used to create a temporary playspace for children and families in an urban area. This was an exploratory case study with a goal to develop pertinent insights for further inquiry (Yin Citation2018) into these types of urban activations. We are not aiming for broad representation, or replicability, but to learn from the stakeholders’ perspectives in this particular project. The data collection reported here began after the temporary playspace had been operating for a 12-week period in 2021. The study’s participants included architects, designers and council staff involved in the design of the space, and an online survey with parents who had attended with their children (reported in Young et al. Citationunder review). As this research was conducted after the 12-week playspace had commenced there is no observational data involving children, families and people in the space (we have reported on the views of the families who visited the site elsewhere, see Young et al. Citationunder review). The educational properties of the space, including loose parts play and early childhood teacher candidates participating in the space have been studied by the academics responsible for this part of the project (see McLaren et al. Citation2021; Citation2022; Citation2023).

This paper focuses on the perspectives of stakeholders involved in the design of the space, drawn from interviews with the architects, designers and council members involved in the temporary activation of the square (see ). The study used semi-structured interviews conducted and recorded over Zoom to gain participants' perspectives (Yin Citation2018). An interview protocol as developed (see Appendix) to focus the discussion on the main research question – What are stakeholders experiences in the design and delivery of a temporary urban play space for children? – and yet open enough for participants to elaborate on relevant topics (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). These five interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed by the second author (approximately 75 min per interview, led by the first author). For the purposes of this paper, we are drawing on the evidence reported from five stakeholder’s interviews with a lens to inform future design collaborations of temporary playspaces for children and families.

Table 1. Participants and professional roles.

5. Analytical method

Data were analysed using both deductive and inductive phases (Gray Citation2021; Yin Citation2015). The deductive phase drew on the literature and coding aligned to design principles, collaborations, places for active play and community input (Bustamante et al. Citation2019; Nicholson Citation1971). The inductive phase then identified further aspects of the phenomenon of interest (i.e., entry into the space, safety, signage) assigning codes to areas where participants repeatedly discussed or responded directly to the research question (Saldaña Citation2021). To maintain the reliability of coding two authors independently coded and any inconsistencies encountered were discussed and resolved. In the analysis, we followed Saldaña’s (Citation2021) coding principles to ensure the qualitative codes were identified and grouped together ‘according to similarity and regularity’ (13). The validity of these codes – i.e., the evidence of the code’s description in the data itself – was established by blind review: the first author made the preliminary analysis codes and the second author then applied these codes to a subset of the data.

More specifically the textual data from the interviews were coded using Saldaña’s (Citation2021) strategies of concept coding focused on a word or short phase to suggest a broader meaning that linked to the literature and/or themes of the project. Also, descriptive coding that summarised ‘the basic topic of a passage of qualitative data’ (Saldaña Citation2021, 134). Our analysis then developed themes that supported a coherent and meaningful pattern in the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). These themes have three key criteria: (1) themes directly and distinctly respond to the main research question; (2) each theme had boundaries that encompassed the codes identified in the first cycle of data analysis (i.e., faithful to the raw data) and; (3) the themes provide a narrative that clearly aligned to what participants told us. The two researchers named the themes when a coherent and meaningful pattern in the data that were relevant to the research question was defined (Braun and Clarke Citation2021).

6. Findings and discussion

The research findings illustrate five themes to consider when designing urban temporary play spaces for children and families. The first two themes address the preparatory phases of the project: (1) activation of the idea and (2) collaboration. The remaining three themes speak to the design of the space in relation to: (3) branding and wayfinding, (4) elements of the physical space and (5) safety.

6.1. Activation of an idea

6.1.1. From the council perspective

The council recognised the urban location of the playspace, between a busy shopping mall and train station, was ideal for accessibility as families go about their daily routines. In the past, the council had directed funds to upgrade the space with, paved pathways, a water fountain, Astroturf and seating to rejuvenate this ‘derelict and rundown’ area as it was viewed as ‘a dead urban space’. However, they understood that this had done little to invite people to be in the space and they wanted to further transform the space from dormant to active and bring new visitation. The council highlighted the intention to bring people into the space people who live in the local government area (LGA), but also those who were from the outside of the area. An expression of interest (EOI) was advertised to community members to submit ideas to take over the space for three months. The council would provide a small stipend (AU $7,000) and pay for infrastructure such as, closing the street and cleaning the space. The EOI asked for a pitch that would activate the space and needed to include the university located in the LGA in some way to support council’s partnership that aims to harness the knowledge and resources of the tertiary institution. The council members interviewed believed that to activate the space would not be difficult, although could also see that it also ‘doesn’t take much for it to become pretty dead and uninviting’. The EOI was open for community members, urban planners or placemakers to invigorate this urban space.

6.1.2. From the architect’s perspective

The architect’s engagement came from a different perspective as they were already aware of the PPL (Bustamante et al. Citation2019) conceptual framework as a method to create a safe and unique play experience for children and families in urban areas. The architect was on a study tour and heard a presentation at the Conscious Cities Festival (The Centre for Conscious Design Citation2019) focused on PPL and this view of designing cities in child-friendly ways aligned with the architect’s philosophy that the public space is one where the community has the right to encounter and engage with in their daily interactions with their cities. This developed the architect’s understandings about designing temporary playspaces in urban environments to activate a location by creating a place where families want to bring their children to play. PPL resonated with the architect as she knew that families spend a huge amount of time outside of formal learning (i.e., child-care and school) and the potential of urban spaces in cities to offer learning through play. This is the third place (Oldenburg Citation1991; Citation2002) where families and children can connect to others in the community. The architect’s philosophy behind the temporary playspace was to ‘not treat the city as a consumptive process, but actually talk about reintegrating human life back into public space’. This approach to urban design is articulated as the ‘public realm’ that is concerned with the physical space and the social activity that takes place (Carmona et al. Citation2010). This was the foundation of the submission to the council’s EOI to pitch the temporary playspace.

The perspectives above indicate that activating new play spaces through community and stakeholder consultation and co-design between parties is extremely effective. PPL is a valid alternative to top-down perceptions that result in funding infrastructure such as surface treatment, fountains, seating and other similar urban nodal points – a ‘build it, and they will come’ approach. In this context, funding temporary play spaces may be more cost-effective than adding new fixed elements to an already dead space rather than redeeming it through playful activation.

6.2. Collaborations

What became apparent from the five interviews was the centrality of collaboration in the design and maintenance of the space. When the architects gained the right to activate the space, this created the initial collaboration between the architects and the council as the two key stakeholders. The architect is responsible for the design and build, the council creating the boundaries around the physical space, financial support and attention to safety. The architects stated they did not have rigid ideas about what shape the playspace would take and the whole process ‘was a very organic and iterative’ over the year of planning, cancellations due to Covid-19 pandemic and the 12-week activation. The collaboration with a local graphic design team created the branding strategy that generated interest before and during the playspace activation (see 3. Branding and Wayfinding). Additional collaborators were involved in two main ways:

the build – through donations of paint from a paint company, materials and labour from a local hardware chain, material donations from local businesses (i.e., tyres from local car yards and materials for loose parts play).

the activation – partnerships were actively researched and developed by the architect team throughout the 12-week activation. These consisted of various workshops conducted for children led by specialists in the community (i.e., knitting workshops, parkour classes, gardening workshops). The local university was invited into the project as the pedagogical experts, where the academic staff consulted as skilled play advisors and early childhood students conducted placements in the space, due to Covid-19 restrictions not permitting them to go into early childhood centres for practicum. Materials were bought out each day by the university team of early childhood academics and students that aligned with the design team’s philosophy of tactics and agency meaning the architectural and pedagogical approaches were rooted in similar values. The pedagogical element of the programme is reported elsewhere by the academic staff involved (McLaren et al. Citation2021; Citation2022; Citation2023).

The context was not merely a matter of an architect as an expert intervening by devising and providing a series of workshops over time. The process – perhaps, partly the result of Covid-19 – was complex. As the architects noted, a critical success factor in the process was its organic and iterative nature. The build, the provision of materials and quite different workshops resulted from an organic, fluid and iterative process, a dynamic rather than a static process – a process which was itself playful.

6.3. Branding and wayfinding

Initial stimulus for the design strategy came from the architect’s engagement with Australian artist Jeffrey Smart. A large body of Smart’s paintings drew inspiration from the urban environments through bold colours that make visible the everyday objects in industrial landscapes (National Gallery of Australia Citation2021). The architect wanted to use the concept of industrial objects in the play landscape. The space in question from the architect’s perspective was ‘too dormant’ and ‘there's not enough activity there’ and so central to the pitch was to create a space that was inviting, safe and engaging for families to want to spend time in the physical space (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). The architect’s philosophical view had an overarching principle that they did not want to over-design the space, fortuitously, because having a limited budget meant that the design brief was restricted by costs.

Local graphic designers joined the project – pro bono as with the architects – in the branding of the playspace. Branding fostered an awareness of the space to encourage community participation (Gibson Citation2009). Two colours were chosen for the design because it was easier to reproduce and more cost-effective. After the graphic designers surveyed the area, to see what sort of posters were around at the time, they decided on the blue for the colour of the local football team and orange to link to the custom-made traffic cone being used as a focal point in the playspace. The designer stated that the chosen two colours, typography and illustrations needed to be ‘bold and iconic’ so when people saw the posters, they would know what it represented. They stated that using photos of the location could not achieve this as the space was not appealing so illustrations were needed to create an ‘almost like a utopian version of what the event would end up being’. They wanted everything to feel tailored to the event and so the typography and illustrations were custom designed.

The illustrator created images that would entice people into the location and were ambiguous to invite people to be curious about what was happening in the space (see ). As the space had not yet been built, they were feeding off the architect’s vision of the playspace. In the graphics, they added a hint at the location, with children and adults, dogs, traffic cones, through visuals that gave a hint of playfulness and energy. The illustrations of adults and children were blue and orange characters, to be ‘culturally and ethnically fluid’. The designers stated that they wanted everyone to feel welcome in the space so leaving enough for people to imagine themselves in the space was needed. This was important for the designers as they know the location has a ‘complete spectrum of backgrounds’ and they did not want it to be tokenistic and the focus was on inclusivity. The design aim was for people to see the branding and imagine a welcoming space for everyone. In the design, they wanted one significant illustration concept for the large main poster to post up in and around the suburb. Elements of this key illustration were used for the website and promotional brochures and stickers (see ).

Integrating branding with wayfinding is a key practice for designers (Gibson Citation2009). The design concept of wayfinding includes signage through images, graphics and iconography to make places visible to the public. The designers in this project knew that the space presented a challenge, because although the location had three laneways as entry points there was an unknown element to going down that laneway, making it difficult to pull people down into the space. Successful wayfinding is a dialogue between people and the design signalling a way to something (Gibson Citation2009). Wayfinding signage design plays a vital role in making places legible using symbolism and images that offer universal signposts to communicate to diversity in language and culture. Wayfinding in design communicates to people how to move through a space and the signage and directional elements are signals. The graphic designer stated that this was not achieved in the way they thought was needed due to lack of funding and time. Ideally, they would have liked ‘a big illuminated electric sign’ in the shopping mall but would have been happy with a simple A-frame (a small board with the branding) at the end at the end of each alleyway’ to lure families into the space. The designers explained that the alleyways were only two meters wide, and some had rubbish bins making them less inviting for parents and this could mean people think ‘This doesn't seem right’, or ‘I'm not going down there’. Initially, there was talk of the alleyways being painted in the branding colours and illustrations to offer entry points into the space. Council staff reported that they did want to ‘change the identity of this dead space’ although because of the limited funding, this was not achieved.

The above process went beyond providing instrumental wayfinding signage. It can be seen that guided by several images, sources, and references, the architects and the graphic designers designed holistically an appropriate urban iconography for the place. This new iconography was achieved by integrating a series of symbols, images, colours and tones for the project. This process was inclusive, considering the community's diversity and critical aspects of the communities’ life, such as the local football team.

6.4. Elements of the physical space

The space, as described above (see ), had a lack of passive surveillance from the surrounding businesses as the perimeter of the space was bounded by the backs of the building. This was a key issue in the design concept so people would feel comfortable in the space to want to enter and then linger. The architects of this temporary playspace referenced the work of Jacobs (Citation1961), an American urbanist who termed the concept eyes on the street, defined as a form of natural surveillance where people create safety as the community are watching and witnessing each other in everyday activities in cities. The architects stated that when we are in community spaces in cities ‘we want to know that we're safe and that someone can see us’ and so a core design principle was to make the space visible and inviting for families and children to play. When people are in the urban environments it provides informal surveillance that can contribute to families perception of safety for their children’s play (Krishnamurthy Citation2019).

The architects addressed the lack of shelter in the space, as adults stay longer in spaces where there are places for them to gather (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). The design needed to create shelter in the space for the diverse weather conditions in the autumn-winter months when the playspace was active. The architect worked with the council to create an infrastructure that doubled as shelter and storage. Two shipping containers were used to store the materials, and a proprietary site shelter structure frequently used on construction sites was attached to each container to cover the area creating a place for shelter. The architects costed other options, like hiring a scaffold and using shade cloth to have a more bespoke solution for shelter; however, this was too expensive. This covered area was only approximately 10% of the whole space providing some shelter and creating the illusion of another space.

The architects wanted to create an object as a focal point in the space to transform the ordinary into something other than a functional object in the landscape. To demonstrate this, the architects designed a play beacon in the form of a giant traffic cone to represent a well-recognised symbol of change, used in this space as a signal to play. The graduate architect stated that when you see a ‘traffic cone you know something's changed, or to stop or to take notice’ and this became symbolic to the nature of the project. The cone was designed 15 times larger than you would usually see creating a large timber frame structure of 3.8 m in height. This cone shape was securely attached to the ground and topped with a cylinder of orange Perspex with a solar light inside. The architects outsourced the build to a set designer and a small team came to install it, with an engineer signing off on a final safety check.

This play beacon was designed so children could go inside and build onto the sides with plastic milk crates, wooden pallets and pieces of the material provided. The graduate architect stated that the cone became more playful and a lot more interesting when the children turned it into something else, and it stopped looking like a traffic cone. It could be transformed into a rocket ship, or a lantern, or anything else entirely. In the design process there were many different iterations that did not happen due to safety; (i.e., putting stairs inside and different heights), or funding (i.e., the small budget meant materials were limited) but it still created a central focal point as a play beacon. It was a permanent fixture for the whole three months residency. All participants in this study discussed how this play beacon became a symbol of the play space, a metaphor for something distorted or not quite as it should, to distract us from the day-to-day and invite us to play.

A sand pit was built in another area of the site, many other items would be taken out from the shipping containers when the university team was facilitating the space, these consisted of loose parts materials in the form of; blocks, PVC pipes, tyres, barrels, milk crates, buckets, carts, a small water tank, that would get packed away into two shipping containers that remained on site.

The elements bought into the physical space suggest an urban approach that can be designated as a bricolage. Again, echoing the processes of play itself, it can be seen that the space was not overly designed or pre-determined by the design experts involved in the project; the resultant space was not the exclusive provision and introduction of objects into the space. This space was different each day, a collision of found materials highlighted by the play beacon, a giant traffic cone which could be transformed through children's imagination and play in different ways.

6.5. Safety

Infrastructure was needed to maintain the space and the council was aware that there were issues that were ‘a reflection of social problems in the area’. There is pressure to diminish anti-social behaviour in urban areas (Elshater Citation2017). Prior to the temporary playspace, the council noted that the area was not family friendly and had been a concern for a long time, stating that, ‘quite a bit that goes on there’. The area was used by people who would be either be drinking or drug taking and there was a great deal of litter around the space. The council did not want to just move people along and remove them from the space, because they were as much entitled to this space as anyone else. Although they were clear that ‘obviously if they are doing something illegal then this is not okay’ and they aimed to make the space available for other community members (i.e., a key driver of the funded temporary activation of the space).

Two main resources were offered by the council to support the 12-week activation: cleaning and traffic control. Both are vital for families to feel safe and want to stay in public spaces (Elshater Citation2017) and play spaces that are clean are valued by children and families (Krishnamurthy Citation2019; Manouchehri, Burns, and Rudner Citation2021). The council supplied initial cleaning, by the way of steam and spray cleaning of the surfaces. There were daily needle pick-ups, and rubbish collection services came through every morning to empty the bins.

Traffic is known to be a major concern for families in city play spaces (Elshater Citation2017; Krishnamurthy Citation2019) and was a central consideration in the design from the architects and council perspectives of this current study. There is a public road that wrapped the full permitter of the square that must be crossed to enter and exit the play space. This road allowed traffic access to the buildings for the businesses backing on to the square. The architects made it clear that when the council closed off the road it signalled to families that this was a safe active space, rather than a mixed-use space.

The key themes we identified in the interview data underscore the temporality and informality of the project, and the fact that it came into being by people agreeing to change their view of a public space and how it was used by community (Buchanan Citation2001). The architect’s vision for the space and the council’s ongoing support meant that families and children had the opportunity to play in an urban space that was not before considered for such exploration. On the days, the activation took play the space invited children and families to see the possibilities for playing. On the ‘off days’, the space reverted back to a relatively unsafe location; by agreeing together to carve out space for play, it was transformed by the designers for families and children to engage. It had a deliberate subtext of practicing democratic and public life together post COVID-19, demonstrating to children that they are part of public life and their capacity to change and shape it (Mouratidis Citation2021). Based on the findings, we can position specific learnings for partnerships between councils and community members (in this case architects) to ignite a vision for the transformation of space. However, these collaborations rely on the individual business in the community to engage with the initial idea and advance the project through good-will, expertise, and skills, underscoring the complexity of achieving an endeavour like this in the community. In addition, the limited funding meant that some parts of the activation could not be realised.

7. Conclusion

The findings illustrate that approaches to considering urban play spaces are informed by professional and experiential knowledge, and the influences designers bring to conceptualising the possibilities of temporary transformations of space. Council perspectives centred around making the square more inviting, simultaneously addressing socially ‘undesirable’ use of the space. The principal architect’s perspective, however, focused on reintegrating human life into the space. Collaboration across the project ensured both the council and architects’ vision for the temporary space was realised. Wider collaboration in the project involved local university academics and students, council staff, local expertise and volunteering for the construction of the space (e.g. painting walls).

Further local expertise was co-opted in inviting graphic designers – who, like the architects were also local residents and knew the space well – whose conceptualisation of branding and wayfinding promoted inclusion and a sense of (re)discovery. Wayfinding not only serves to signal the possibilities of a space but serves the practical function of encouraging people to engage with an otherwise unfamiliar or unnerving place. This becomes particularly important in a location where there are not ‘eyes on the street’ (Jacobs Citation1961); creating an invitation to place was important in this project, achieved by the distinct design of an oversized cone as a signal for something other than the mundane and a beacon for play. Practical provisions such as shelter and storage for play resources were also considered in the design and development of the temporary playspace. Practical issues need to be accounted for in the design, budget and delivery, as cleaning of the space and safety considerations – e.g., limiting car access – are essential for public engagement.

Our data have shown how designers and council staff conceived of then reflected on a temporary play space as a third place (Oldenburg Citation1991; Citation2002) for the community to gather and children to play. An element of designing spaces that did not arise in our interview data was how or why children should be involved as ‘legitimate stakeholders’ (see Rudner Citation2017), enabling a bottom-up approach to co-planning (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). The missing collaboration, as reported by the architects in this study, was consultation with children and families during the pre-design phase of the project (Derr and Tarantini Citation2016; Krishnamurthy Citation2019). Incorporating families and children in the design process gives voice to community and promotes collaboration (see Bustamante et al. Citation2019). These voices are valuable as families have a great deal of insight on ways to engage their children, and children have a strong connection to place through their ‘high levels of place attachment, place knowing and stewardship’ (Malone Citation2016, 25). Moreover, children have rights as full citizens of any city (Smith Citation2015). The playspace reported this paper was always in the process of being designed and re-designed as the participants became the constructors of the space. As we strive to make cities more liveable, the inclusion of temporary play spaces where children and their families can play on their way to daily activities allows playfulness to be part of community engagement (Bustamante et al. Citation2019). Future research would benefit from understanding how consultation with children and families in the design process, with specific details of children’s perspectives of the space and the affordances this type urban playspace offers for their play engagement (beyond the scope and ethics approval for our case study). The design principles in this project had a deliberate open and unfixed characteristic to invite the children and families to co-construct the play landscape on their visits (Malone Citation2015; Schlesinger et al. Citation2020). This requires councils to rethink cities spaces by reimagining ways to transform areas for play and learning. It was the collaboration between designers, council, and other community stakeholders that enabled the activation of this urban space into a community play environment.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with ethical approval by the University Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent for participation was gained from all the participants prior to data collection, making clear their involvement was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time. Participants have been named by their professional roles for anonymity as prescribed by the research ethics approval. This project took place on traditional lands of the Kulin Nation. We offer our respect to the Elders of these traditional lands, and through them to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as custodians of country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. “Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA).” [Technical Paper]. Commonwealth of Australia. www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012016.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196.

- Brinkmann, Svend, and Steinar Kvale. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousan: Sage.

- Buchanan, Ian. 2001. Michel de Certeau: Cultural Theorist. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Bustamante, Andres S., Brenna Hassinger-Das, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Roberta M. Golinkoff. 2019. “Learning Landscapes: Where the Science of Learning Meets Architectural Design.” Child Development Perspectives 13 (1): 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12309.

- Carmona, M., S. Tiesdell, T. Heath, and Taner Oc. 2010. Urban Places-Urban Space: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Oxford: Architectural Press and Routledge.

- The Centre for Conscious Design. 2019. “The Centre for Conscious Design.” https://theccd.org.

- Derr, Victoria, and Emily Tarantini. 2016. ““Because We Are All People”: Outcomes and Reflections from Young People's Participation in the Planning and Design of Child-Friendly Public Spaces.” Local Environment 21 (12): 1534–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1145643.

- Elshater, Abeer. 2017. “What Can the Urban Designer Do for Children? Normative Principles of Child–Friendly Communities for Responsive Third Places.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (3): 432–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2017.1343086.

- Gibson, David. 2009. The Wayfinding Handbook: Information Design for Public Places. Princeton Architectural Press. Electronic resource.

- Gray, David E. 2021. Doing Research in the Real World. 5th ed. London: Sage.

- Hassinger-Das, Brenna, M. Jennifer Zosh, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, S. Andres Bustamante, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2021. “Translating Cognitive Science in the Public Square.” Trends in Cognitive SciencesCognitive 25 (10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.07.001.

- Henket, Hubert-Jan. 2022. “Modernity, Modernism and the Modern Movement.” In Back from Utopia: The Challenge of the Modern Movement, edited by Hubert-Jan Henket and Hilde Heyne. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Krishnamurthy, Sukanya. 2019. “Reclaiming Spaces: Child Inclusive Urban Design.” Cities & Health 3 (1–2): 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2019.1586327.

- Malone, Karen. 2013. ““The Future Lies in our Hands”: Children as Researchers and Environmental Change Agents in Designing a Child-Friendly Neighbourhood.” Local Environment 18 (3): 372–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.719020.

- Malone, Karen. 2015. “Children’s Rights and the Crisis of Rapid Urbanisation.” The International Journal of Children’s Rights 23 (2): 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02302007.

- Malone, Karen. 2016. “Children’s Place Encounters: Place-Based Participatory Research to Design a Child-Friendly and Sustainable Urban Development.” In In Geographies of Children and Young People, edited by Tracey Skelton, 1–30. Singapore: Springer.

- Malone, Karen, and Julie Rudner. 2017. “Child-Friendly and Sustainable Cities: Exploring Global Studies on Children’s Freedom, Mobility, and Risk.” In Risk, Protection, Provision and Policy, edited by Claire Freeman, Paul Tranter, and Tracey Skelton, 1–26. Singapore: Springer.

- Manouchehri, B., E. A. Burns, and J. Rudner. 2021. “Creating a Child-Friendly Neighborhood: Iranian Schoolchildren Talk About Desirable and Undesirable Elements in Their Neighborhoods.” Children, Youth and Environments 31 (3): 74–97. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.31.3.0074.

- McLaren, M.-R., J. Grimes, S. Jobson, and A. Munari. 2022. “Extraordinary in the Ordinary: Complexities of belonging in the City.” Reggio Emilia Australia Learning Exchange Symposium.

- Mclaren, M.-R., J. Grimes, S. Jobson, A. Munari, and C. Scott. 2023. “The response-ability of a public pop-up playspace: Deep listening at Mini Maddern in inner-city Melbourne.” The Challenge 27 (1): 5–9.

- McLaren, M.-R., J. Walsh, S. Jobson, C. Scott, N. Nehma, and P. Mascarenhas. 2021. “Playspaces in Public Places: The Ethical and Social Challenges of a Pop-Up Urban Playspace in Melbourne, Australia.” Play 2021, Birmingham, UK.

- Mehta, Vikas, and Jennifer K. Bosson. 2009. “Third Places and the Social Life of Streets.” Environment and Behavior 42 (6): 779–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509344677.

- Mouratidis, K. 2021. “How Covid-19 Reshaped Quality of Life in Cities: A Synthesis and Implications for Urban Planning.” Land Use Policy 111:105772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105772.

- National Gallery of Australia. 2021. Jeffrey Smart. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia.

- Nicholson, Simon. 1971. “How NOT to Cheat Children: The Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape Architecture 62 (1): 30–34.

- Oldenburg, R. 1991. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. New York: Marlowe.

- Oldenburg, R. 2002. Celebrating the Third Place: Inspiring Stories About the “Great Good Places” at the Heart of our Communities. New York: Marlowe.

- ON/OFF Collective. 2017. Co-Machines: Mobile Disruptive Architecture. Berlin: Onomatopee.

- Rudner, J. 2017. “Educating Future Planners About Working with Children and Young People.” Social Inclusion 5 (3): 195–206. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i3.974.

- Russell, W., and A. Stenning. 2020. “Beyond Active Travel: Children, Play and Community on Streets During and After the Coronavirus Lockdown.” Cities & Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1795386.

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 4th ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Schlesinger, Molly A., Brenna Hassinger-Das, Jennifer M. Zosh, Jeremy Sawyer, Natalie Evans, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2020. “Cognitive Behavioral Science Behind the Value of Play: Leveraging Everyday Experiences to Promote Play, Learning, and Positive Interactions.” Journal of Infant, Child & Adolescent Psychotherapy 19 (2): 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1755084.

- Smith, K. 2015. “Citizenship: Childhood and Youth Citizenship.” In Handbook of Children and Youth Studies, edited by J. Wyn and H. Cahill, 357–376. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4451-15-4_64.

- Stevens, Q. 2001. Play in Urban Public Spaces. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

- Umstattd Meyer, M. R., C. N. Bridges, T. L. Schmid, A. A. Hecht, and K. M. Pollack Porter. 2019. “Systematic Review of how Play Streets Impact Opportunities for Active Play, Physical Activity, Neighborhoods, and Communities.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6609-4.

- UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund. 2018. Child Friendly Cities Initiative.

- Weisberg, Deena Skolnick, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, Audrey K. Kittredge, and David Klahr. 2016. “Guided Play.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 25 (3): 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416645512.

- Yin, Robert K. 2015. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. London: Sage.

- Young, S., Church, A., Maskiell, A., Raisbeck, P. & Eadie, T. under review. “Temporary Spaces Designed for Children: A Case Study of Parent Reports on an Urban Pop-Up Play Space.”

Appendix. Interview prompts for key stakeholders

Transforming urban places for children’s play: A study of community wellbeing

45–60 min interviews to be held online (ZOOM) and audio recorded.

What led to your initial engagement in [this] project?

What were the aims of the [this] project from your perspective?

How important is the location of [this] Square to you?

What was the value of stakeholder partnerships to the project?

From your perspective, what was the impact of Covid-19 on your planning and delivery of the project?

How do you think the design principles respond to children’s play and creativity?

From your perspective, how did children and families engage with the space?

Has the process of [this project] changed the way you think about including play in the public realm?

From your perspective, what lessons can be learnt that might inform the transformation of urban spaces for children in the future?

How do you think a space like [this] contributes to community wellbeing?

What safety mechanisms and/or other logistics need to be considered for this type of project?

What learnings can be taken and applied to future sites or similar transformations of public places?

From your perspective, how does [this project] and other similar events/activations help to build stronger communities within [this] City?