ABSTRACT

Melbourne, like many cities of the global north, is growing rapidly through migration. Many migrants find home on the urban fringe in Master Planned Estates. This settlement is encouraged by urban policy, but there is a need to understand and respond to the needs of the multitude of religious communities. This paper traces the development of places of worship on the fringe of western Melbourne and the possibilities for expression of faith on the periphery of established settlement. It illustrates, in particular, how places of worship are often either spatially disconnected from the communities which they seek to serve, or not fit for purpose in failing to meet the requirements of religious and cultural activity. The transformation of land into commercialisable units of housing, or commerce invites an improvisational response on behalf of religious communities. Overall the study finds that the rudimentary consideration of places of worship in greenfield development is a touchstone of the difficulties that the Australian planning system faces in encompassing the diversity of the community. The ‘superdiverse’ migrant body with its transnational economic, cultural, and religious connections represents a dynamic shift and complication of the suburbs that are all too often dismissed for a supposed homogeneity.

Practictioner points

The growth of urban populations on the fringe of Melbourne is constituted by a diverse population that has religious needs. The form of urban development does not cater to this and, in response, there are innovative responses to establish places of worship that mean they can be disconnected from the people they serve.

There needs to be more consideration on behalf of planners and policymakers on how to respond to the spatial needs of the multiplicity of religions in greenfield urban development – so that places of worship are integrated into new communities.

Introduction

Rockbank, in the City of Melton, lies 30 kilometres from central Melbourne. Travelling on the train to the outer western suburbs, one passes through remnant grasslands, a landscape of thistles and rocks on a volcanic plain, the bent arms of excavators breaking the flat horizon. Greenfield housing development takes place in the form of Master Planned Estates (MPE). This is an unexpected setting for a panoply of places of worship – often hidden away in old farmhouses, industrial precincts, and community buildings scattered across the plains. This study traces the development of places of worship on the fringe of Melbourne and the possibilities for expression of faith in the built environment. It illustrates, in particular, how these places of worship are often either spatially disconnected from the communities which they seek to serve, or not fit for purpose in failing to meet the requirements of religious and cultural activity. Drawing on the case of the Hindu Sri Durga Temple, it also shows how religious communities respond to the challenges of establishing a place of worship.

Multiculturalism has come to be celebrated in public life in Australia. However, in practices like urban planning, many of the cultural and religious dynamics inherent to a ‘multicultural’ population continue to go unnoticed or are purposefully overlooked (Sandercock and Kliger Citation1998). This is particularly visible in MPEs such as those developed in Rockbank (Roggenbuck Citation2019). MPEs most regularly lie on the fringe of Australian cities and are often the first home for settling migrants, drawn by the affordability of house and land packages that enable home ownership. This is the case in the Local Government Area (LGA) of the City of Melton where 30% of inhabitants were born overseas, with half of them having arrived in the last five years (Profile.id Citation2020). In MPEs, rates of migration are even higher than in established areas of the municipality. This inherent diversity of MPEs challenges the stereotypical portrayal of suburban development as spaces of ‘banality and sameness’ (Johnson Citation2010, 379) Instead, on the fringe of Melbourne, we find the suburban clustering of migrant populations in diverse ‘ethnoburbs’ (Li Citation2009), of which the construction of places of worship are a material signifier.

Urban Planning, which emerged from religious reformist movements such as the Methodist temperance societies, has become increasingly secularised in the 20th and 21st centuries. The provision of social services was key to the foundation of urban planning, in its religious beginnings through charity, and from the Second World War through the policies of the Welfare State. Model towns such as Port Sunlight (1888) and Bournville (1893) in Great Britain, produced by industrialists such William Lever and George Cadbury, were conceived with the ‘pillars of church, work, and community in an attempt to improve the spiritual and physical well-being of workers’ (Cheshire Citation2010, 359). These towns became templates of planned urban communities and spawned the formalisation of urban planning as a discipline. Today, the character and motivation of urban planning have become overwhelmingly a lever of economic growth: ‘[planning] has been outsourced, privatised, marketised, and stripped of the knowledge and confidence that informed its founders’ (Gleeson and Low Citation2000, 24). Migration is an important component of the growth ideology, crudely by increasing the size of the economy, but also by encouraging the settlement of highly skilled and educated workers to promote innovation within the Australian economy. Since revoking the White Australia policy in 1973, Australia has looked to migrants from diverse backgrounds to bolster work markets.

The process of post-industrialisation has led to a focus on encouraging ‘knowledge workers’ in skilled migration programs. In 2004–2005, 65% of permanent visas were granted under skilled migration schemes (Productivity Commission Citation2006, 15). With the world economy increasingly intermeshed and reliant on mobile and transferable workers, cities like Melbourne are competing for the pool of skilled labour. The associated migration and movement of people is diverse not only in origin but also in terms of the status and purpose of people’s stay (Vertovec Citation2007). The diversity of communities and religions to which newly arrived migrants may belong, presents a need for negotiation and forward thinking, on behalf of migrants, who navigate a planning system ill-equipped to resolve their needs. When the land for development into MPEs is rezoned from rural and agricultural to residential, its value soars, impeding the ability of migrant religious communities to fund and construct places of worship at a suitable scale. The prohibitive cost and possibilities of community opposition to places of worship (Dunn Citation2005; Villaroman Citation2012) often lead religious communities to establish their places of worship ahead of the construction of residential areas. The disjunction of time and place, where existing communities lack places of worship, and large facilities stand isolated in rural plains is the dialectic that the study aims to unravel.

Outer-urban MPEs are exemplary means by which market-driven developers produce a holistic affordable housing product for mortgaged consumption. McGuirk and Dowling define MPEs as ‘large-scale, integrated housing developments produced by single development entities that include the provision of physical and social infrastructure […] predominantly located on the “growth frontier” or city fringe’ (McGuirk and Dowling Citation2007, 22). The City of Melton, the focus municipality of this study, features an array of MPEs both completed and in planning.

Over the last four decades, developers of such MPEs have sought to provide a complete ‘packaged environment’ (Freestone Citation2010), in what can be viewed as a recasting of the utopian planning visions of the nineteenth-century communities of place (Johnson Citation2010), exemplified in the type of place branding of many MPEs. In assessing the positive aspects of MPEs, Johnson (Citation2010) points to the ‘environmental utopianism’ realised in MPEs, along with the positive experience of residents gaining social status through property ownership. However, the implications of MPE developments have been debated also in terms of privatisation of public space, socio-spatial polarisation, and a commodified image of ‘community’ (Cheshire, Walters, and Wickes Citation2010; Thompson Citation2013). Critical voices describe, amongst others, a marketed ‘aesthetics of community’ (Cheshire, Walters, and Wickes Citation2010, 362) that does not differentiate community members and their varying cultural attachments (Roggenbuck Citation2019, 186). Other scholars point to the complexities of the processes and factors involved in greenfield development (McGuirk and Dowling Citation2007). The continued presence of government actors in the development of MPEs, for instance, prevents a simplified dichotomy of private and public actors – a simplification that McGuirk and Dowling (2009) see as all too common in analyses undertaken essentially as a critique of ‘neoliberal planning’. In the state of Victoria, public actors play a role in greenfield development through the Victorian Planning Authority – formed in 2006 as the Growth Areas Authority – who sets strategic goals through its Precinct Structure Plans. These plans provide the guidelines for private developers, which are incorporated into the planning scheme of the relevant planning authority – most commonly the local government – and to which development has to conform.

When considering the cultural characteristics of MPEs, the literature identifies the marketing of an ‘Australian Dream’ projecting White exclusivity even when, in reality, they produce cultural diversity (Kenna Citation2007; Nicholls, Maller, and Phelan Citation2017; Roggenbuck Citation2019; Tewari and Beynon Citation2017). In their study of Point Cook, another Melbourne outer suburban area, Tewari and Beynon (Citation2017) explore the significance of homeownership amongst migrant communities. Homeownership evokes pride among communities, the authors argue. Heeding this, Roggenbuck (Citation2019) further suggests that home ownership also allows for important cultural practice, such as religious festivities, to take place privately and is a key desire fulfilled by large housing in MPEs, discussed further below.

Questioning the supposed secularising outcome of globalisation for urban and suburban areas, Casanova (Citation2013) underlines innovative and adaptive religious responses to changing social contexts which, in the case of migrant religions, emerge from ‘new transnational religious dynamics’ (Casanova Citation2013, 123). Engaging with this transnational diffusion of religious cultures, Dwyer, Gilbert, and Shah (Citation2013) provide a typology of places of worship to demonstrate capacities for religious innovation and adaption in suburban settings. In London, they describe so-called semi-detached, ethnoburb, and edge-city forms of places of worship. The semi-detached form, exemplified through an Anglican church, attempts to reproduce ‘distinctive and discrete places’ (Dwyer, Gilbert, and Shah Citation2013, 411) of religion in suburban space, reviving the traditional Anglican parish division of space in suburbs. To illuminate the ethnoburb form, the authors use the case of the West London Islamic Centre, which combines the functions of mosque, community centre, and gym. The ethnoburb mode references Li’s (Citation2009) work on ethnic concentrations in suburbs that retain transnational linkages of commerce, family, and culture. Dwyer et al. highlight the religious component of these networks and the ‘cosmopolitanism’ of worshippers that find their fulcrum at the Islamic centre. Finally, the edge-city form describes the establishment of large places of worship at the ‘edge’ of the city, which relies on motorised transportation networks to connect the place of worship with a metropolitan-scale public. In the Edge City, Garreau (Citation1992) describes the contemporary form of urban development not revolving around an existing urban core but placed on the backbone of high-speed road infrastructure. The mobility produced by the highways allows for rapid movement between functions and land uses.

In Dwyer et al.’s, example of the edge-city place of worship becomes accessible to mobile worshippers throughout and even beyond metropolitan London. Dwyer, Tse, and Ley (Citation2016) expand on the conception of ‘edge-city’ religiosity in an examination of the development of a ‘Highway to Heaven’ in Richmond, Canada. In this instance, special zoning regulations for places of worship were enacted to create a buffer between agricultural and urban land, resulting in an agglomeration of diverse places of worship on the edge of the city, similar to what we find in Melbourne. In the case of Richmond, however, this is actively encouraged through planning policy.

In Australia, Bugg (Citation2012) has also focused on the fringe of the city, describing conflicts of land use in establishing minority places of worship in peri-urban space. In her study of Camden LGA in Sydney, she highlights a ‘discourse of incompatibility in which embedded within this understanding of zone and character is a particular Anglo-Australian sense of place that excludes the possibility of minority religious facilities’ (Bugg Citation2012, 279). The defence of heritage values in landscapes was deployed to argue for the incongruence of a Hindu place of worship in a rural area. The majority Anglo-Australian communities in metropolitan Sydney defend lifestyle uses of land, such as hobby farms and horse-riding, to challenge the ability of minority groups religious groups to establish places of worship. Lobo (Citation2020) has discussed the aesthetics of anxiety in terms of affect theory in suburban Melbourne.

Previous studies of the interaction between minority places of worship and the planning system in Australia have identified how the underlying secular worldview of planning is challenged by the religious needs of communities (Bugg Citation2012; Ibrahim Citation2013) and that the supposedly neutral and technical activity of planning is imbued with values that conflict with minority religions particularly Islam, which can be politically contentious (Dunn Citation2005; Sandercock Citation2000; Villaroman Citation2012). Scholars argue the way in which ‘prescriptive classifications such as zones, use restrictions and design controls are in fact social as well as spatial practices’ (Bugg Citation2012, 279).

In the Victorian planning system, places of worship are a subcategory of the broader places of assembly. The land of MPEs within the Urban Growth Boundary is zoned as Urban Growth Zone, a category of land use that allows for places of worship but only with referral to the Victorian Planning Authority to ‘ensure that future plans for the land are not compromised’ (Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Citation2015, 5) and to maintain the strategic use of land as developed in Precinct Structure Plans for future MPE development. The guidelines for Precinct Structure Plans have no explicit reference to the planning of places of worship (Growth Areas Authority Citation2013).

The parallel and competing development of MPEs and the religious infrastructure of the communities that make their home within MPEs is the tension this paper is interested in uncovering. The next section introduces the case study of Sri Durga Temple and the methods employed. Followed by findings of the study and a discussion of the implications for planning in a greenfield context.

Materials and methods

The empirical study of this study has been designed around qualitative research methods, employing ethnographic means to study the Hindu communities of the Sri Durga Temple in Rockbank. Whilst this community and its specific place of worship is at the centre of the study, I have also engaged with other religious communities in Melton and my findings will be punctuated with their experiences (Falzon Citation2009). My focus was on the strategies and means of establishing a place of worship on Melbourne’s fringe and both the challenges and opportunities this presents for minority religious groups. The outer-suburban concentration of religious infrastructure has been explored and studied in other cities of the global North, this study provides a unique account of the dynamics of religious practice in greenfield suburban development in Melbourne. The study speaks to the means of religious expression in the ‘super-diverse’ city.

Since 2019, I have been a member of the Melton Interfaith Network (MIN)– a network of religious groups, aiming to encourage and enable social cohesion and capacity building across faiths. From the context of MIN, I am familiar with the challenges faced by many religious groups in the City of Melton and have chosen the Hindu Sri Durga Temple as a specific case study site for its significance to migrants of Indian heritage, who are the predominant migrant group to the area with 3.8% of the population being Indian born (ABS Citation2019). Relationships built in MIN have enabled me to pursue ethnographic research methods, including a combination of participant observations, and interviews with key religious representatives, community members, and relevant council employees. Whilst a case study like this, by necessity, produces ‘concrete and context dependent knowledge’ (Flyvbjerg Citation2011, 302), similar processes and dynamics of suburban religious infrastructure have been witnessed in other cities of the global north, including Richmond (Canada) and London (Dwyer, Gilbert, and Shah Citation2013 Dwyer, Tse, and Ley Citation2016;).

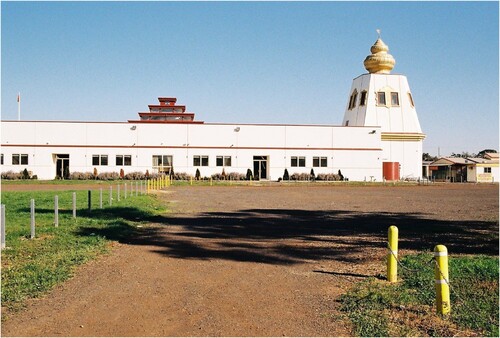

In the 2016 census, Hinduism was the second fastest-growing religion in Australia in percentage growth (behind Sikhism) and had the greatest number of new adherents, with a 60% growth from 2011 growing from 275,535, to 440,300. In Australia, 92% of Australian Hindus live within Greater Capital City Areas and 81% were born overseas. There is a great capacity for natural growth with a median age of 31 (ABS Citation2018). The development of the Sri Durga Temple mirrors the growth in the population of Hindus in the west of Melbourne. It lies nestled on the Hopkins Road exit of the Western Freeway, 30 Kilometers from Melbourne’s CBD. The City of Melton represents the western edge of the Urban Growth Boundary, and in all senses, the temple is on the fringe of the city. The southern edge of the expansive temple grounds is taken by the freeway, the north is currently farmland in the process of being subdivided into suburban housing in the Deanside Village MPE.

To speak of Hinduism, it must be clear to distinguish the diversity of adherents to the religion in Rockbank there are presently three Hindu temples (Mandir) serving distinct communities: ()

Figure 1. Sri Durga Arts/Cultural and Educational Centre (Inc), Temple honouring Durga goddess, Hindi Language based.

My initial understanding of the issues surrounding places of worship formed at meetings of the Melton Interfaith Network (MIN) and local events that I attended. These events took place in the neighbouring local government areas of the City of Melton and the City of Wyndham and were usually attended by a mix of religious community leaders, local government diversity employees, and other community members. At these events, I participated actively and documented them photographically. I established contacts and developed an awareness of the experiences and positions of different actors, the infrastructures of worship, and the dynamics of religious expression; this awareness is not easily formulated or recorded but was crucial for my subsequent analyses (DeWalt and DeWalt Citation2011).

In addition to the many informal conversations I held at these events and other occasions, I also arranged five semi-structured in-depth interviews with key actors, identified through my participation in MIN. Interviews lasted 30–40 min and took place on the telephone or online through Zoom. Interviews were considered as an appropriate research method to enable these key actors to disclose their self-understanding of their perspectives and experiences in the context of their religious practices (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009, 27). ( and )

Table 1. List of interviewees.

Table 2. Events attended.

Findings

In researching the establishment and the spatial distribution of places of worship in the outer suburban areas of western Melbourne, it became clear that the factor of scale plays an essential role. I identified three ‘scales’ of places of worship as religious communities respond to their growth and needs. These three scales of worship reflect the relative size of the congregation and its ability to gather. Moreover, these scales have a temporal element, both in the use of spaces at certain times for worship and the developmental scale of the community as it outgrows the limitations of the smaller scales. The scales include: (1) The home. A religious group often begins its practice from private homes, creating a space for worshipping within the home and holding religious activities for small groups; (2) Provisional place of worship. The use of intermediary provisional space in either council venues, sharing places of worship with another religious group, or using a makeshift building; (3) Designated Place of worship. When a religious group constructs its own place of worship.

To be clear, the three identified scales provide a heuristic means of analysing how religious groups find space to worship. In reality, they are not distinct, but entangled in complex ways, and often function in parallel. A home temple, for instance, is not dismantled simply because a larger venue is acquired. As the results will illustrate also, there is the movement of religious groups between scales and, correspondingly, across space.

Worshipping at home

The most personal place of worship is that of worshipping at home, where members of a religion create a devotional space within the home. The Bhutanese Hindu Interviewee 4 describes the importance of home worshipping, for members of the community:

Every morning and every evening before the dinner, they will pray to god and worship god. Most of the family members in my community make a small home temple in living areas or where they have got space, like in different bedrooms, and they make a small home temple and they pray there. It is really, really important for my culture actually and for the religion (Interviewee 4)

We have got quite a number of people who are actually practising their religion in their own homes … they don't have the facilities to do that … going through the process of applying for land in order for them to build [a place of worship]. It's not an easy process for somebody who is recently arrived from somewhere else, and they have other challenges to look at anyway. So, looking for places of worship, they would rather look for alternatives and these alternatives would be perhaps to do it in their own homes (Interviewee 1)

The mobility issues faced especially by elderly people, including an inability to drive or access to a car and barriers to using public transport, further contribute to the importance of being able to worship at home ‘elderly people … they can't use the transportations, you know, and they have got a home temple’ (Interviewee 4)(Hartt, DeVerteuil, and Potts Citation2023). The range of barriers outlined is a reason why worshipping at home is an alternative that minority religious groups seek to maintain their practice of faith.

The larger housing of suburban areas and MPEs is attractive to those migrant community groups who form multigenerational households ‘We normally live in a joint family. We have got that practice and that habit since the ages’ (Interviewee 4). As Roggenbuck states for prospective buyers ‘the ability to accommodate guests is mentioned as a key requirement for the house’ (Roggenbuck Citation2019, 192) either for specific festivities, or longer-term stays from family members, also from overseas. Visits of up to a year from family members are common under the sponsored family stream of the visitor visa. The larger and relatively affordable housing of the outer suburbs allows for this practice. Relating these findings back to the literature discussed in the introduction, the above section provides an account of how the ‘super-diversity’ of religious communities has an impact on their religious practice. The ability of different minority religions to self-advocate and raise funds reflects the social capital that they hold. This also identifies that particular groups may need specific types of support. Interviewee 1 interfaith officer at the City of Melton employee describes the importance of proactively ‘identifying minority religions’ as an ongoing task for the council and through outreach to provide better support. It also demonstrates that the housing of MPEs affords a level of flexibility at the scale of home worshipping.

Limitations onf the size of residences mean that the practice is necessarily within a small group. Interviewee 3 from the Sri Durga community describes early private home gatherings in the late 1990s for Bhajan (devotional music such as chanting) between small family groups, from which a core group gathered funds to purchase the land for the Sri Durga Temple. While remaining integral to daily religious practice, worshipping at home is the minimal scale of religious practice. The home limits the possible size of the congregation, which impedes the social aspect of religious practice and the importance of gathering as a community for mutual support. Once exceeding the space of the home, religious communities seek to expand their religious practice in the use of provisional spaces, such as community facilities, temporary buildings, and sharing a space with other religions.

Provisional place of worship

Community facilities operated by the City of Melton are frequently used by religious groups as provisional places of worship. They afford a bigger space than private homes and a level of flexibility with the size of the hired venue dependent on the size of the gathering. For instance, a religious group may hire a smaller space for regular worship and a larger hall for a special festival or celebration. While the provisional spaces of worship may resolve the problem of capacity for a gathering, the multipurpose nature of these venues and their competing use by the whole spectrum of community organisations and individuals, presents new challenges.

Interviewee 2, a City of Melton employee in Diversity and Intercultural Development, recounts how religious organisations

often called me and said, look, we want to hire, for example, x y z buildings for an ongoing basis, as long as we want. I said, sorry, you know, council policy does not actually allow that because we want to be equitable and inclusive and also fair to everyone.

The use of community facilities requires improvisation to arrange a multifunctional space into a sacred space. Idols set up in these spaces are often image representations of gods, rather than the statues found in designated places of worship. Interviewee 1 notes that this temporary arrangement has its limitations: it is difficult to make the available space fit for purpose and to generate the specificity of a sacred space, even – as he says – for the relatively austere arrangements common in Christianity:

It's not even ideal, to be very honest, for even a Christian organisation to use a community hall, for example. Yeah, because it doesn't have the features of like crosses, you know, objects of significance for that particular religion. So today it was used by the Christians, tomorrow is used by another church, that has no consistency. You can't put your objects of worship in that particular area. So, it is not suitable, but people are using it as an as alternative because they don't have anywhere else to go. (Interviewee 1)

The location of these facilities can present further difficulties, with Interviewee 1 noting: ‘Halls, in some cases, they are not available in places that are easily accessible’. The Botanica Springs Children’s and Community Centre in the south of the City of Melton, which has limited public transport connections, provides a concrete example. For religious groups, access is thus an issue both in terms of securing hire for a provisional place of worship and in terms of location and transportation to these places. Indeed, for Interviewee 2, access to a place of worship presents ‘the number one challenge’ for minority religious groups.

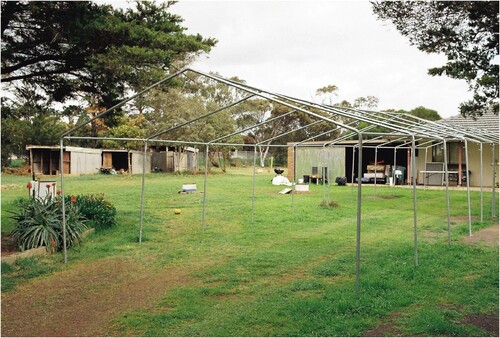

The construction of a permanent place of worship is often a long process for migrant faith communities. A common strategy is to purchase land and use a provisional place of worship until funds can be raised for a fully-fledged construction. In the case of the Sri Durga temple, it took 15 years of fundraising from the initial purchase of land by four founding families to the beginning of construction of the prayer hall. In these intervening years, a provisional temple was erected with limited space for worshippers. Interviewee 3 recalls: ‘We had a huge 30 acres of land, but a very small temple – only a shed, a tin shed – which can host only 40–50 people’.

A further example of provisional places of worship is the sharing of established places of worship. This sharing practice is common when groups share religions but speak different languages. Members of the Bhutanese Hindu community are frequent visitors to Sri Durga. Interviewee 4 explains: the ‘Holy Book is same, the gods are the same, everything is the same’, apart from the language ‘we have Nepali language, they have Hindi language’. In Melton, this can see up to three groups using the same place of worship with services in shifts on a Sunday. Differences in language and culture remain important for diasporic religious communities, Interviewee 1 notes there ‘are Christians, but they might not want to join with the bigger Christian organisation because they want to do it in their own vernacular language’. For migrant groups, religion can be an important moment of ‘cultural retention and reproduction’ (Frederiks Citation2016, 17) and a means by which continuity in one’s identity can be maintained in a new country. Language clearly plays an essential role in this. Interviewee 1 describes the overarching aim for a ‘truer form of multiculturalism that allows people to have those places to celebrate and not share’.

Independent place of worship

The availability of land in Melton is a cause of contention. On the one hand, its relative affordability in MPE housing developments draws buyers to the area. On the other, the demand for large parcels of land from property developers creates difficulties for religious groups in raising sufficient funds to purchase land of significant size to construct a place of worship. Large plots of land are required due to needs beyond the footprint of the building itself. Interviewee 1 explains:

The design of major places of worship is that they need not only the building itself, they also need parking. For vehicles, and sometimes they have outdoor activities. So, they would require large pieces of land. (Interviewee 1)

The popularity of festivals has the potential to cause future conflict as the surrounding area is being developed into the ‘Deanside Village’ MPE. Interviewee 5 from the Sri Durga community has concerns over the planning of Rockbank and expects future problems as the Precinct Structure Plan envisions residential development to surround the temple (VPA Citation2018, 8): ‘we have large festivals throughout the year, many times there is a road congestion, even on the freeway. and there is a lot of problem in the parking’ (Interviewee 5). From the perspective of Interviewee 5, it would have been preferable to have open space adjoining the temple, allowing the temple to extend festivals out into public space, or for temporary parking use at peak times.

The popularity of festivals at Sri Durga’s is a feature of its ability to cater to a religious public spread throughout the metropolitan area. Whilst daily visitors generally come from within the City of Melton and adjoining areas, weekend and festival visitors travel from throughout the metropolitan area to reach the temple. The temple’s location right at the freeway exit means ‘people can come straight away, take exit and come to temple so it’s easy to come’ (Interviewee 3). The temple’s freeway access reflects the edge city place of worship typology of Dwyer, Gilbert, and Shah (Citation2013, 2016; Garreau Citation1992) The connection to the freeway network gives the temple a greater catchment for a religious community. For Sri Durga, like in Dwyer et al.’s conception, ‘the edge-city location provides a means of accommodating a dispersed and mobile faith community’ (Dwyer, Gilbert, and Shah Citation2013, 416) the affordability of the land at the time of purchase and connectivity provided by the freeway offsets limitations of the isolated location.

Interviewees 2, 3 and 5 all highlight how Sri Durga makes the surrounding MPEs more attractive for Indian buyers. Interviewee 3 believes the majority of housing ‘blocks are being sold to Indian community … because the people want to be close to temple, to be true. This is it. So, I think these developments are selling fast because of the temple playing a very key part’ (Interviewee 4). A result of the increasing urbanisation of the land surrounding Sri Durga is the development of an ‘ethnoburb’ (Li Citation2009), with a concentration of Indian residents in the area. Future challenges will be how Sri Durga manages to combine functions of the ‘ethnoburb’ place of worship, whilst serving the larger metropolitan area.

Although it is well served by freeway infrastructure, the immediate access to the temple is presently a problem due to the short section of dirt road from the freeway exit to the entrance of the temple. Council employee Interviewee 2 explains that ‘when you build a place of worship in that remote part of the city, the infrastructure becomes your responsibility’. Interviewee 3 from the perspective of the Sri Durga, however, would like to see more support from other actors. ‘We have to wait for years until those developers, you know, and council and Vicroads build the road’ (Interviewee 3) The frustration is echoed by Interviewee 5. The gravel road and lack of footpath reduce the utility of the bus stop, a product of community advocacy, near the temple. Interviewee 3 sees this as a problem particularly for elderly members and children trying to access the temple. The public bus was initially only a Sunday service, but now runs each day – to note the rhythm of the place of worship attendance doesn’t align with traditional Sunday service, the temple sees use throughout the week.

We had a campaign. and now have a bus that stops really close to the temple … it took a long time, but it happened. Yeah. But it would have been much easier if we had more government support, at least consideration. – (Interviewee 5)

Discussion

As the previous section finds, faced with a lack of a defined process for the establishment of places of worship, religious groups in a suburban context find novel means of maintaining religious practice by adapting space to their needs. The three ‘scales’ of the findings are a simplification of the processes of religiosity in order to foreground the phases of development of a religious group and demonstrate specific needs at each scale and challenges faced.

The results demonstrate that along these scales, issues of access, transport, and financing limit the ability of religious groups to realise their goals. The search for affordable land can remove the place of worship from its community. The planning system in its current form doesn’t anticipate the religious needs of communities. An unresolved tension is how to realise in space the claims of diverse religious groups. The current response sees a fragmentation of space with the religious component of urban life as a ‘fringe’ phenomenon.

In the example of Sri Durga as an ‘edge-city’ style place of worship, it caters to a community that is widely spread throughout Melbourne and beyond. A means of collapsing time–space is the temple’s connection to high-speed freeway networks to connect with a community beyond the local government area. As the surrounding areas develop, it will be interesting to see how Sri Durga manages its metropolitan-level significance with the developing ‘ethnoburb’ around it. A further element in the discussion of time–space is the use of digital technologies to further expand the reach of services and events. At events, I witnessed the use of video-calling to connect with family members in Melbourne and overseas. Another aspect of technological integration is the use of the Sri Durga Facebook page to organise and inform the community. This has been particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic with livestreams of services being held on the platform and updates on current guidelines and developments, along with the connection to community services including food distribution run by the temple.

The form of community presented by MPE development is an undifferentiated ‘universal’ idea of community and is reflective of the form of multiculturalism, whose norm is defined by White culture. Due to this, I argue MPE developments as a whole are inflexible to the religious needs of particular migrant communities. The prioritisation of a simplified packaged environment, with reproducible housing products, doesn’t respond to the specificity of religious communities who are moving into the housing development. The housing of MPEs has the flexibility to arrange home temples and incorporate a religious space within the home. Outside the private sphere of the home, there is a missing consideration and understanding of religious affiliations of communities. While other studies on barriers to the establishment of minority places of worship have focused on community opposition (Bugg Citation2012; Dunn Citation2005; Ibrahim Citation2013) my goal was to demonstrate how the spatial imaginary of MPE development, with its legacy in utopian Christian religious urban planning, is unable to adjust and respond to the diversity of community.

There remains an array of challenges in the practice of minority religion and more research is required to elaborate how religious groups can be supported through the developmental ‘scales’ identified. The single case study of Sri Durga Temple along with reflections from field work and involvement with MIN does not encompass the entire complexity of religious practice in the City of Melton. Whilst the study attempted to augment the case study of Sri Durga temple with the experiences of other religious groups, the study does not provide an exhaustive account of the dynamics of minority religions within the City of Melton or Melbourne more generally. The concept of ‘super-diversity’ from the literature is a constant reminder of the complications of simply collapsing aspects of identity under umbrella terms such as Hindu and foregrounding the diversity within diversity.

At its most fundamental, currently, as it is, the planning system at both state and local level is reactive to the needs of minority religious communities and does not foresee or anticipate their spatial needs. The policy implications emerge from the challenges presented in the findings and revolve around the issues of access, suitability, and transport, and in the designing of precinct structure plans.

The use of community centres as a place of worship is a common intermediary stage in a religious community’s development. As shown in this study, there is high demand for these spaces from a range of actors and they are the primary form of social infrastructure delivered in precinct structure plans with public access. More clarity on the responsibility of council and developers to provide these spaces and access to community centres could provide security to religious groups. Furthermore, an awareness of their use for religious activity may be reflected in design guidelines and the inclusion of specific features to better enable religious activity in community centres. This could be storage space for idols or facilities for religious ceremonies such as access to water for Islamic Wudu ablution before prayer.

As shown in this study, the location of places of worship can be isolated from the communities they seek to serve. An added complexity is the need for land at a range of scales. Not all groups will grow to the size of Sri Durga, and their varied needs will need to be considered. A challenge therefore is arranging and forecasting land of a suitable size for evolving migrant religious groups. The form of strategic planning in growth areas by the Victorian Planning Authority through Precinct Structure Plans could have a more explicit focus on places of worship as a necessary community facility and thereby ensure that places of worship are considered in the development process.

Religious diversity has spatial needs. The study has reasserted the importance of minority religion and its relationship to urban form. It found the form of development fostered by MPEs should better respond to the needs of religious communities to ‘commune’ or gather together. The task of urban planning will be to reacquaint itself with ‘the spiritual’ in the city, which is increasingly a complex multiplicity of spiritualities.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the guidance and support given by Dr Irene Håkansson without which the work would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Census Reveals Australia’s Religious Diversity on World Religion Day. Accessed May 24. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/mediareleasesbyReleaseDate/8497F7A8E7DB5BEFCA25821800203DA4?OpenDocument.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2019. 2016 Census QuickStats: City of Melton. Accessed May 24, 2020. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA24650?opendocum.

- Bugg, L. B. 2012. “Religion on the Fringe: The Representation of Space and Minority Religious Facilities in the Rural–Urban Fringe of Metropolitan Sydney, Australia.” Australian Geographer 43 (3): 273–289.

- Casanova, J. 2013. “Religious Associations, Religious Innovations and Denominational Identities in Contemporary Global Cities.” In Topographies of Faith: Religion in Urban Spaces, edited by I. Becci, M. Burchardt, and J. Casanova. Leiden: Brill.

- Cheshire, L., P. Walters, and R. Wickes. 2010. “Privatisation, Security and Community: How Master Planned Estates are Changing Suburban Australia.” Urban Policy and Research 28 (4): 359–373.

- Department of Environment Water Land and Planning. 2015. Planning Practice Note 47: Urban Growth Zone. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/97307/PPN47-Urban-GrowthZone_June-2015.pdf.

- DeWalt, K., and B. DeWalt. 2011. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Dunn, K. M. 2005. “Repetitive and Troubling Discourses of Nationalism in the Local Politics of Mosque Development in Sydney, Australia.” Environment and Planning: Society and Space 23 (1): 29–50.

- Dwyer, C., D. Gilbert, and B. Shah. 2013. “Faith and Suburbia: Secularisation, Modernity and the Changing Geographies of Religion in London’s Suburbs.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (3): 403–419.

- Dwyer, C., Justin Tse, and David Ley. 2016. “‘Highway to Heaven’: The Creation of a Multicultural, Religious Landscape in Suburban Richmond, British Columbia.” Social & Cultural Geography 17 (5): 667–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1130848.

- Falzon, M. 2009. Multi-Sited Ethnography: Theory, Praxis and Locality in Contemporary Social Research. London: Routledge.

- Fincher, R., K. Iveson, H. Leitner, and V. Preston. 2014. “Planning in the Multicultural City: Celebrating Diversity or Reinforcing Difference?” Progress in Planning 92: 1–55.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2011. “Case Study’.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by K. Denzin and Y. Lincon. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Frederiks, M. 2016. “Religion, Migration, and Identity: A Conceptual and Theoretical Exploration.” In Religion, Migration and Identity: Methodological and Theological Explorations, edited by M. Frederiks and D. Nagy, 9–29. Leiden: Brill.

- Freestone, R. 2010. Urban Nation: Australia's Planning Heritage. Clayton South: Csiro Publishing.

- Garreau, J. 1992. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. New York: Anchor.

- Gleeson, B., and N. Low. 2000. “‘Unfinished Business’: Neoliberal Planning Reform in Australia.” Urban Policy and Research 18 (1): 7–28.

- Growth Areas Authority. 2013. Precinct Structure Planning Guidelines: Part Two. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.vpa.vic.gov.au/wp-content/Assets/Files/PSP%20Guidelines%20-%20PART%20TWO.pdf.

- Hartt, M., G. DeVerteuil, and R. Potts. 2023. “Age-Unfriendly by Design: Built Environment and Social Infrastructure Deficits in Greater Melbourne.” Journal of the American Planning Association 89 (1): 31–44.

- Ibrahim, M. S. 2013. “Is the Urban Godless? An Analysis of Mosque Planning Applications in Melbourne.” Master's thesis, University of Melbourne, Australia.

- Johnson, L. C. 2010. “Master Planned Estates: Pariah or Panacea?” Urban Policy and Research 28 (4): 375–390.

- Kenna, T. E. 2007. “Consciously Constructing Exclusivity in the Suburbs? Unpacking a Master Planned Estate Development in Western Sydney.” Geographical Research 45 (3): 300–313.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2009. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Li, W. 2009. Ethnoburb: The New Ethnic Community in Urban America. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Lobo, M. 2020. “Recomposing Aesthetic Anxiety and Perforating Suburban Infrastructures: Informal Religious Meeting Places in Melbourne.” Fabrications 30 (2): 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2020.1749221.

- McGuirk, P. M., and R. Dowling. 2007. “Understanding Master-Planned Estates in Australian Cities: A Framework for Research.” Urban Policy and Research 25 (1): 21–38.

- Nicholls, L., C. Maller, and K. Phelan. 2017. “Planning for Community: Understanding Diversity in Resident Experiences and Expectations of Social Connections in a New Urban Fringe Housing Estate, Australia.” Community, Work & Family 20 (4): 405–423.

- Productivity Commission. 2006. “Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth.” Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/migrationpopulation/report/migrationandpopulation.pdf.

- Profile.id.com.au. 2020. Birthplace City of Melton Community Profile. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://profile.id.com.au/melton/birthplace.

- Roggenbuck, C. 2019. “Diverse Lived Experiences of Community in Masterplanned Estates: A Case Study of Filipino and Indian Migrants in Wyndham.” Urban Policy and Research 37 (2): 185–198.

- Sandercock, L. 2000. “When Strangers Become Neighbours: Managing Cities of Difference.” Planning Theory & Practice 1 (1): 13–30.

- Sandercock, L., and B. Kliger. 1998. “Multiculturalism and the Planning System, Part One.” Australian Planner 35 (3): 127–132.

- Tewari, S., and D. Beynon. 2017. “Master Planned Estates in Point Cook–The Role of Developers in Creating the Built-Environment.” Australian Planner 54 (2): 145–152.

- Thompson, C. 2013. “Master-Planned Estates: Privatization, Socio-Spatial Polarization and Community.” Geography Compass 7 (1): 85–93.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Victorian Planning Authority. 2018. Melton C147 Precinct Structure Plan Kororiot. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://vpa-web.s3.amazonaws.com/wpcontent/uploads/2018/02/MeltonC147IncorpDocKororoitPrecinctStructurePlanDecember2017ApprovalGazetted-Part-1.pdf.

- Villaroman, N. G. 2012. “Not in My Backyard: The Local Planning Process in Australia and Its Impact on Minority Places of Worship.” Religion and Human Rights 7 (3): 215–239.