ABSTRACT

Melbourne is renowned for its urban waterways management. With the introduction of the Healthy Waterways strategy 2018–2028, decision-makers aimed to involve the community more collaboratively. However, the reality of doing so is complex, and outcomes have not always been as intended. We identify three dilemmas that limit the effectiveness of community collaboration, drawing on a study of how communities were involved in the governance of the Melbourne waterways of Merri Creek and Moonee Ponds Creek. The dilemmas are that: resources are stretched; a lack of focus and unclear responsibilities can undermine efforts; and the effectiveness of engagement practices is uncertain and depends on context. We argue that these dilemmas make community collaboration challenging and limit its potential for co-benefits. However, there is an opportunity to develop shared visions and goals that motivates ongoing action, drawing on the strengths of the community and choosing methods more purposefully with consideration of constraints, ensuring that the aims are both achieved and legitimate. This allows for the integration of fragmented resources, capacities, roles, and benefits into a central vision, fostering collaborative principles of transparency, responsibility, ownership, and accountability.

Practitioner pointers

Poor resource management, lack of focus, and sometimes inappropriate methods can undermine the effectiveness of community engagement.

To resolve these issues, we suggest a vision-oriented approach that leverages what the community is good at and applies shared-purpose-based methods.

We suggest institutional, methodological, policy and structural changes in the decision-making context to support community engagement.

1. Introduction

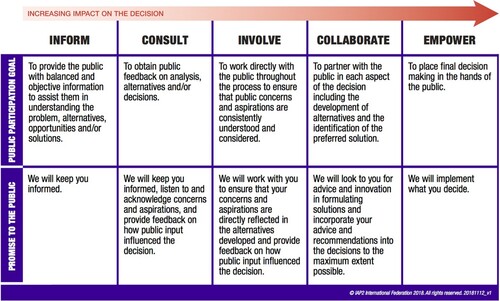

This article reports on a study of community engagement for urban waterways governance, in the context of Melbourne, Australia. Drawing on literature review, case study, and policy review, it identifies three dilemmas in how engagement is implemented, and a set of practical recommendations to overcome such dilemmas.

Urban waterways are rivers, wetlands, streams, watersheds, estuaries, and bays within the boundaries of cities (Melbourne Water Citation2018a). They provide benefits as multi-purpose corridors amidst the urban environment and connect people with nature. They play a vital, multi-functional role in addressing societal challenges and mitigating climate change while providing essential ecosystem services, such as flood control and water purification, that promotes sustainability and urban resilience. Many cities worldwide are setting long-term goals to expand these benefits of urban waterways by involving the catchment community in their management and governance. Importantly, the Onondaga Creek Revitalisation Plan-Syracuse, New York (Moran, Perreault, and Smardon Citation2019), River Aire, Leeds, United Kingdom (Bokhove et al. Citation2020) and Kallang Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters Programme, Singapore (Iftekhar et al. Citation2019) emphasize that successful community engagement has the potential to generate broader benefits by leveraging community knowledge and capacity, and fostering socio-cultural benefits, to create a flourishing natural environment.

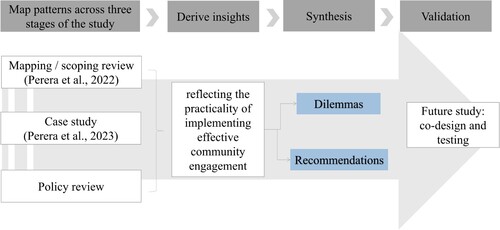

Within the domain of urban waterways governance, community engagement represents a concerted effort to bring local residents into place-based decision-making processes and other management efforts focusing on these environments (Ariana and Judy Citation2021). This participatory approach seeks to foster a sense of ownership and to activate involvement among community members, transcending mere procedural involvement. Importantly, not all community engagement is equal, and a common measure to distinguish different engagement activities is the ‘level of engagement’, which refers to the degree of involvement and participation of community members in making decisions. A commonly applied standard is the IAP2 (International Association for Public Participation) Spectrum of Public Participation, represented in . This tool evolved from the ‘ladder of participation’ which was proposed by Arnstein (Citation2019); (Arnstein Citation1969). The ladder describes different modes of community engagement and the level to which community members are engaged in the decision-making processes (Bowen et al. Citation2014; Stuart Citation2017).

Figure 1. IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation, Source: IAP2 (IAP2 Citation2019).

In urban waterways management, the effectiveness of community engagement is contingent upon establishing robust social connections, ensuring procedural fairness, and fostering collaborative synergies (Butcher et al. Citation2019; Chen, Qian, and Zhang Citation2015). Genuine effectiveness is discerned not merely by the level of community participation but by the depth of commitment and responsibility instilled within the resident demographic (Measham et al. Citation2011; Glackin and Dionisio Citation2016; Moran, Perreault, and Smardon Citation2019). Research findings consistently underscore that outcomes which are achieved through inclusive decision-making processes are more likely to be sustainable and perceived as successful in the long term (Moran, Perreault, and Smardon Citation2019; Dillon et al. Citation2016). True effectiveness in community engagement thus necessitates a comprehensive understanding of diverse perspectives, an appreciation of diverse opinions, and the formulation of solutions that harmonise the range of needs and preferences of the community (Cernesson et al. Citation2005). Building on the growing recognition of the effective role that communities can play, it has been argued that with the increasing complexity and uncertainties in governing waterways, involving the local community in decision-making for its governance has become essential for a resilient future (Angela et al. Citation2016; Glackin and Dionisio Citation2016; Dunn, Bos, and Brown Citation2018).

In this paper, we synthesize the findings from a study of urban waterways management (UWM) in Melbourne Australia that includes three phases (literature review, case studies, and policy review), exploring effective community engagement interplays in UWM and urban planning. We do not propose a one-size-fits-all approach but instead, draw attention to introducing practical and systematic methodologies that can enable more effective community engagement for urban waterways management (CEUWM). Our proposals can benefit urban planning and UWM practitioners and policymakers concerned with facilitating transformative change in collaborative-adaptive community involvement. We think the suggested approaches, methods and policy changes inform better planning practices and provide insights for planning, design, and sustainability scholarship.

2. History of involving the community in governing Melbourne's waterways

Many Western countries, as suggested by Ross, Baldwin, and Carter (Citation2016), incorporated statutory requirements in environmental governance practices in the 1960s. In the United States, from 1969, pioneering institutions were legally enacted to involve the community in development activities (Glasson, Therivel, and Chadwick Citation2012; Bond et al. Citation2020). These initiations were followed by Australia and New Zealand in the early 1970s (Bush, Miles, and Bainbridge Citation2003; Fogg Citation1981). As a rapidly growing city, Melbourne, Australia, is renowned for its urban waterways, and communities are becoming more involved in urban waterways management. With the introduction of collaborative urban waterways governance in 2018, locally through the Healthy Waterways Strategy 2018–2028 (Melbourne Water Citation2018b), those (legally) responsible for managing the waterways now include urban planners, water managers, engineers, and local government officials.

Initiatives such as this were designed to involve the community more collaboratively, to enable broader, localized knowledge and inputs, to better deal with the complexity of water governance (Melbourne Water Citation2018a). More details about this are available in the Annexures of this article. Other community engagement efforts in Melbourne have focused on issues like raising awareness about water conservation, pollution prevention, and the preservation and restoration of natural ecosystems (Melbourne Water Citation2018b; Healthy Waterways Strategy Citation2023). As a result, waterways managers within municipal governments and water management organizations have worked with the community for clean-up campaigns, citizen science programs, project development, master planning, strategy formulation, policymaking, and habitat restoration (Melbourne Water Citation2018a; Coleman et al. Citation2016; Prosser, Morison, and Coleman Citation2015).

Reframing CEUWM in Melbourne is essential. This is because, firstly, current approaches to community engagement have often overlooked important population segments and have lacked focus, which in turn leads to unequal representation, a lack of shared responsibility and ownership, and unclear long-term outcomes (Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023; Melbourne Water Citation2018b; Goodwin Citation2022; Malekpour, Tawfik, and Chesterfield Citation2021). Secondly, there is a growing interest and commitment in the governance of urban waterways from diverse community actors, which has not been leveraged as productively as it could (Goodwin Citation2022; Pexton and Nagato Citation2019; Coleman et al. Citation2016). Both of these points represent a missed opportunity. A third point also exists, which is that a failure of many engagement strategies is caused by a lack of planning, and understanding and long-term funding for strategies, leading to on-the-ground practices and outcomes that are largely ineffective in terms of achieving policy outcomes, regardless of the higher-order engagement aims of policy (Perera et al. Citation2022).

3. Method

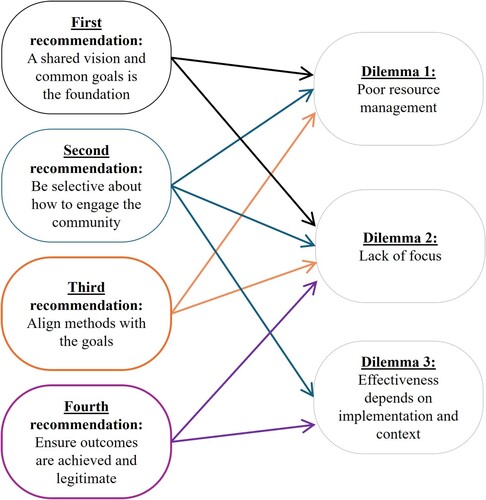

The method here synthesizes the insights derived from three stages of this study of CEUWM in Melbourne, Australia. The first two stages of the study were published. First, the review of academic literature (Perera et al. Citation2022), and second, the case studies that explored the lived reality of community engagement strategies in Melbourne (Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023). In this article, we draw on the insights from these research activities, but also add a third stage involving policy review. shows the three stages of the research. Findings of each stage of the study highlight three dilemmas that limit effective CEUWM. To overcome the identified dilemmas, we propose four recommendations that should be practically applicable to practitioners and policymakers.

3.1. Literature review

The literature review was based on an analysis of 51 peer-reviewed scholarly works selected from an electronic database, i.e., ‘Scopus’, and analysed using the Values, Rules, Knowledge (VRK) framework (Colloff, Gorddard, and Dunlop Citation2018), through a three-step approach (Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien Citation2010; Arksey and O'Malley Citation2005):

Search publications,

Screening through inclusion and exclusion criteria,

Analyse through the VRK framework.

The documents were searched through a keyword search in ‘Scopus’ (see ), resulting in 316 articles. These articles were further screened out to 51 articles through a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

o Studies focus on our research contexts, i.e., urban waterways/NBS governance/community participation,

o Peer-reviewed articles, conference papers and literature reviews

o Published in the English language.

Exclusion criteria:

o Not relevant to the research contexts,

o In the research context but in political contexts of developing or least developed countries

o Non-peer-reviewed articles, such as dissertations, books, research reports and theses (grey literature).

Table 1. Systematic literature review key search terms extracted from our paper Perera et al. (Citation2022).

A detailed description of each step used in this method can be found in our scoping review paper (Perera et al. Citation2022). Key outcomes derived from the review include: mapping the factors restricting or enabling effective CEUWM; outlining the evidence for what is referred to as the ‘intention-implementation gap’; and the misalignment between planned and implemented engagement, affected by institutional and social aspects. These insights provide inputs into the synthesis of this paper.

3.2. Case study

What was identified as the intention-implementation gap in the literature review, and the factors contributing to it, were further studied empirically with a focus on the governance of Merri Creek and Moonee Ponds Creek, both in Melbourne, Australia. This included twenty-three semi-structured interviews with state, regional and local government experts (n = 10), community groups and individuals (n = 10), and academic experts (n = 3). Interviews were conducted between May 2022 and December 2022 and lasted between 30 and 90 min each. With formal consent, the interviews were held online or in person. The analysis process involved coding interview data using open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Creswell Citation2013; Nowell et al. Citation2017), within the conceptual frame of the VRK heuristic. Details of the interviews and case study were published in the article by Perera, Moglia, and Glackin (Citation2023). Through this, we broadened the knowledge of the lived reality of engagement. Case study findings were critical in defining dilemmas and recommendations in relation to how to achieve effective CEUWM. See Annexures for case study data.

3.3. Policy review

To triangulate and enrich insights from the literature review and case study, findings were further put into context and complemented by drawing on industry reports, policy documents and organizations’ annual reports. This review was conducted in two stages. The first was the empirical study, where the literature reviewed was related to each case. Second, the policies and regulations related to CEUWM were analysed in a broader context to understand how such policies and guidelines shape the community engagement practice. In this stage, we analysed how policies and guidelines shape, enable or limit the chances of effective community engagement.

4. Results

We identify three key themes in the data across the literature review, case study, and policy review. These relate to:

resource allocation;

implementation of engagement processes; and

the governance of engagement activities.

Below, we report on these three themes for the three research methods.

4.1. Literature review

Here we report on selected insights from the literature review. More extensive insights can be found in Perera et al. (Citation2022).

4.1.1. Resource allocation

We find in the academic literature that a ‘top-down’ approach for allocating resources (Hart et al. Citation2022), combined with using inconsistent or inadequate key performance indicators (KPIs), means that even when policy encourages the practice of high levels of participatory community engagement (as per the IAP2 framework), decision-makers generally do not adequately resource such practices and instead tend to focus on relatively lower levels of engagement (Hart Citation2016; Angela et al. Citation2016).

Literature furthermore suggests that uncoordinated or scattered allocation of resources can pose challenges to effective CEUWM. For example, when resources are dispersed among several agencies, organizations, stakeholders, or community groups, this can lead to fragmented efforts, lack of economy of scale, and thereby reduce the productivity of final outputs, which in turn can lead to less meaningful community engagement (Productivity Commission Citation2020; Rushforth and Ruddell Citation2015).

Relating to the need for prioritization of community engagement activities, several of the reviewed articles highlighted some tasks that the community can carry out well, and by doing so generate co-benefits, such as providing context-based knowledge to identify issues, solutions, hands-on activities, monitoring and policy development (Rees Catalán Citation2015; Vall-Casas et al. Citation2021; Reed et al. Citation2018; Fratini et al. Citation2012; Buntaine, Zhang, and Hunnicutt Citation2021).

Academic literature also highlights that whilst effective resource allocation (Brown et al. Citation2016; Marlow et al. Citation2013; Wolch, Byrne, and Newell Citation2014) is critical for achieving positive outcomes (which are subjectively defined by the community), there is sometimes a disjoint between legislative powers and institutional, community responsibilities in relation to an outcome, and the allocation of resources to help support that outcome (Hardy Citation2022). In other words, whilst legislative responsibilities and powers may have been delegated to key institutions, influential and powerful organizations still tend to control resource allocations to help achieve such outcomes.

4.1.2. Implementation

As community groups and government agencies embrace community collaboration, they adopt a range of methods for putting such intentions into action. It is noted within the academic literature that there is a large diversity of methods being applied. For example, this includes public meetings and workshops, stakeholder advisory group discussions, surveys and questionnaires, online engagement platforms, co-design sessions, and partnerships and collaborations (Schwermer, Barz, and Zablotski Citation2020; Dyer et al. Citation2014). It is also observed that institutional decision makers tend to choose between such engagement methods on the basis of being easily implemented within the bureaucratic framework, even if it is unclear whether such methods are the most effective or most inclusive approaches (Rădulescu, Leendertse, and Arts Citation2022). Literature also suggested the use of more active engagement methods, such as citizens science and Citizens’ Jury are not very commonly applied in practice (Bonney et al. Citation2020; Dhakal and Chevalier Citation2016).

There is also a tendency by decision-makers to view community engagement as a panacea without considering its function more deeply, leading to stretched resources as staff become involved in time-consuming engagement activities that sometimes fail to align with strategic goals (Desouza and Bhagwatwar Citation2012; Bonney et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, both the decision-makers and the communities significantly failed to achieve the targeted goals and purposes of their engagements (Quick and Feldman Citation2011; Agyeman and Erickson Citation2012; Head Citation2022). For instance, Head (Citation2022) discusses how superficial engagement efforts often result in unmet objectives, emphasizing the need for deeper, more meaningful participation and feasible goal setting.

4.1.3. Governance

The importance and effectiveness of multi-level decision-making in urban waterways governance is a common theme in academic literature. This approach, involving collaboration among diverse actors, including bicycle networks, conservation volunteers, friends groups, developers and construction firms, local residents and businesses, was acknowledged for its capacity to facilitate positive outcomes across social, economic, ecological, and technical dimensions (Rijke et al. Citation2012; Vall-Casas et al. Citation2021; Bos and Brown Citation2013).

However, efforts to integrate multi-level decision-making through adaptive governance systems, as highlighted by Rijke et al. (Citation2012), tend to fall short of waterways managers’ expectations. To address such issues, it has been suggested to clearly define the shared rights and responsibilities of multi-stakeholders to ensure legitimacy and avoid power dynamics (Rijke et al. Citation2012; Glaas et al. Citation2022; Lupp et al. Citation2021).

Some authors further highlighted that government agencies sometimes transfer tasks to communities based on convenience rather than to align with strategy or shared goals (Uittenbroek et al. Citation2022; Reed et al. Citation2018; Rees Catalán Citation2015). The findings show that agencies should clearly define the community's role and tasks, ensuring alignment with both their strategic objectives and shared goals (Reed et al. Citation2018; Dillon et al. Citation2016).

4.2. Case study

Here, we report on selected insights from the case study. More extensive insights can be found in Perera, Moglia, and Glackin (Citation2023).

4.2.1. Resource allocation

From case study interviews, we found that the allocation of resources by government organizations varies depending on factors such as urgency, the scale of the project, financial capacity, stakeholder priorities, legislatively defined roles and responsibilities, and accessibility to external resources.

In Melbourne, state government agencies are key players, as they have significant resources allocated to urban waterways management and are crucial in policy development, planning, regulation, and implementation of UWM initiatives. Similarly, in this context, local governments are also important actors as they allocate resources for waterway maintenance, infrastructure development, conservation, and community engagement activities. We found that all government agencies allocate resources based on their priorities, motivations and objectives, such as economic considerations, regulatory requirements, and top-down strategic goals, rather than implementing based on shared goals and achieving environmental and community priorities. For example, an urban planner from LGA mentioned:

Even in our organisation, I have seen how resource [financial, expertise knowledge, machinery and tools, etc.] allocation mainly follows our own priorities. Economic gains, regulatory demands, and top-down goals usually take the lead. Unfortunately, this can mean that environmental and community interests get overlooked. It’s a real challenge to push for a balance that truly benefits our local waterways and the people who rely on them.

We partially fund their [community group] existence [due to the failure in managing priorities]. So, they run a range of projects and programs for us […] So, we sit down and say, this is how much we would like to grant you, and you should spend it for these projects.

4.2.2. Implementation

The case studies provided evidence that the adopted level of community involvement, as per the IAP2 framework (see ), varies considerably, being lower in some activities (like strategy formulation and promoting behavior changes), while higher in others (i.e., hands-on activities, citizen science programs, and vision developments). Factors such as institutional interest, benefits, capabilities and potential conflicts or risks shape the varying levels of engagement in different activities. However, this contrasts with common expectations and preferences within the community. To illustrate this issue, a community leader mentioned that:

In my experience, many individuals express a preference for engaging in decision-making actions like providing feedback on designs, plans, or issues, as opposed to being involved in activities such as strategy formulation or policymaking. They [i.e., community members] seem to have more passion and confidence in contributing to decisions that directly impact their needs and expectations.

We need different tools/methods for different community groups and use the right tools/methods with the right groups. […] We really need community driven approaches to understand their senses and emotions attached to waterways in deciding what and how they experience and connect with the place we will create in future beyond just providing solutions.

Not surprisingly, given the above, the case study findings indicate that community involvement is unfortunately not always very effective due to limited awareness, lack of communication, and/or not accounting for legislative or practical constraints, requirements and capabilities. This was explained by one of the council officers:

We can’t use every data collected by community groups, as they are not realisable. They haven’t followed our technical standards or our supervision. So, such efforts have mostly been wasted.

Most of the trees we planted were dead by now or had not been monitored or maintained well. […] We remove weeds and collect litter from the waterways, but some councils have not given enough priority or action taken to stop where they come from or introduce solid solutions. Sometimes, I feel we are wasting our time and hard work we invested for this.

In terms of methods, we found that engagement practitioners tend to assume that using recommended methods, e.g., workshops and co-design sessions, will achieve a targeted level of engagement in practice. However, this does not necessarily follow. In fact, self-reported levels of engagement varies for the same methods, highlighted by the different views being reported. To highlight one perspective, a regional waterways manager mentioned:

In our journey, we've conducted numerous co-design workshops, training sessions, and pop-up meetings across the planning and implementation stages. These efforts have significantly enhanced the effectiveness and success of the engagement process.

We have been to a bunch of meetings and workshops, but honestly, we have not seen any real solutions yet. It feels like the officials love to chat and discuss things, but when it comes to making decisions, they are pretty slow. That is why we are not going to as many meetings now; it just seems like a waste of our time.

Within the case studies we identified, especially based on interviews with local government officers, that there are limitations of using only formal methods, such as limited representation of the community, lack of authenticity, resource intensity, and that, almost by instinct, engagement officers instead often opt for using informal methods such as talks on site, breakfasts, cultural celebrations, or coffee discussions. These types of methods are mostly practised outside, or in addition to, official community engagement plans.

We found that municipal officers also developed informal methods to connect with the community more intimately, increasing trust-building before engaging in more formal ways, thereby overcoming some of the limitations of more formal methods. To illustrate this common perspective, a Local Government Agency officer emphasized:

We have found that getting to know the community on a personal level really helps build trust before introducing formal participation. So, before we dive into the formal methods, we make sure to connect with them in more relaxed settings. It is a way for us to overcome some of the challenges that come with sticking only to formal methods.

4.2.3. Governance

We found that policies and guidelines on community engagement plans in urban waterways governance tended to be government controlled, leaving community members with little or no influence over the process. A Local Government Agency officer explained:

As government officers, we follow set policies and tools recommended by the legislation and consultants, like IAP2.

We use them to decide which communities to engage in, choose suitable methods, and plan how to involve the community in different initiatives. […] We mostly make decisions based on what we want from them and who we want to engage with the most.

No acceptable outcomes were gained compared to how much time was spent. It needs to focus more on what must be achieved at a high priority rather than implementing projects to benefit a few stakeholders. […] Most decisions they made benefited real estate developers [private sector developers] or institutions’ needs, but less [for] the well-being of the natural environment.

4.3. Policy review

Here, we report on selected insights from a review of relevant policy documents and grey literature in relation to the case studies.

4.3.1. Resource allocation

Resources for community engagement, financial or otherwise, generally come from state and local government. Melbourne Water, a state government owned statutory authority, plays a key role in managing rivers, creeks, and catchments (Hart, Francey, and Chesterfield Citation2021; Loo and Clarke Citation2017). The state government’s Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water, and Planning (DELWP) also play a key role in terms of setting state-wide policies for water management (Hart, Francey, and Chesterfield Citation2021; Loo and Clarke Citation2017; DELWP Citation2017).

With limited resources, it becomes essential that coordination can support adequate economy of scale, yet our review of policy documents indicates that resource allocations (mainly human, technical, and financial) vary between councils or other local government agencies according to their priorities, capabilities and statutory roles (City West Water Citation2020; Melbourne Water Citation2021-Citation2022). The review of policy documents also highlights the nature of fragmented urban waterways management policies across local, state, and regional levels in Melbourne (Department of Sustainability and Environment Citation2012; Victorian Auditor-General Citation2017a; Melbourne Water Citation2018a). This disjointed governance landscape limits the opportunity for critical mass and restricts resource allocation for any given task, thus impeding the effectiveness of community engagement practices. This is not surprising given that the range of institutions have their own priorities, approaches, and communication channels as top-down institutions, and seemingly tend to find it difficult to establish a unified, efficient, clear, and collaborative community engagement strategy (Victorian Auditor-General Citation2017b; Loo and Clarke Citation2017).

4.3.2. Implementation

We found that some policies and guidelines may make community engagement more difficult, in light of insights from the case studies and literature. For example, the Public Engagement Framework developed by Victorian State Government (Citation2021) gives a very broad space for decision-makers to define how the community could be involved. It provides a diverse set of principles and recommendations to follow, yet provides limited practical guidance on how to implement participatory processes in practice. These principles and recommendations could lead to some engagement officers ending up ‘ticking boxes’ rather than developing a workable strategy.

4.3.3. Governance

Government agencies and representatives are encouraged to use more participatory methods that promote inclusivity and justice for diverse community voice representation (State of Victoria Citation2020; Victorian State Government Citation2021). However, the most frequently followed frameworks and heuristics, such as the IAP2 (Citation2019) and Public Engagement Framework 2021–2025 (Victorian State Government Citation2021), instead encourage the use of methods that align with a chosen level of participatory engagement, which have minimal considerations given to enable the effectiveness of community engagement in setting and delivering shared goals and justice.

We found in policy documents and industry reports that, due to a lack of clarity about what community members should and could be purposefully involved in, there is a common lack of integration of engagement outputs into policies or governance (Loo and Clarke Citation2017; DEPI Citation2013; Department of Sustainability and Environment Citation2012). Furthermore, while legislation like the Local Government Act (State of Victoria Citation2020) mandates community engagement across a range of key business functions, these are largely limited to very high level strategies (asset management, 4-year council and financial plans, revenue raising etc.) and, significantly, full authority is given to Local Government Authorities to decide who, when and for what purposes to engage. This is in contrast with case study findings where we found that community participants tend to engage in participatory activities in good faith, believing that activities will lead to something tangible, such as citizen science programs, community clean-up events and revegetation and habitat restorations (Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023).

Regarding legal responsibility, while legislation such as the Victorian Local Government Act does promote engagement, it only does so with relation to high level planning and finance processes, and does not enforce the level at which engagement should occur; potentially allowing further tokenistic ‘box-ticking’ exercises. We could find no legal mandate for community to participate in more focused and reflective practice, nor a requirement for training or knowledge of bureaucratic or technical systems, likely leaving many community participants unaware of the legal or institutional priorities and responsibilities of overall urban planning or environmental governance (including budget limitations), or the limitations on capabilities and resources needed for implementation.

In the context, interestingly, there is also a policy imperative to align with the Victorian Government’s legislative and policy commitments, that prioritize supporting the aspirations and rights of Traditional Owners in the governance of waterways. This shows a requirement to facilitate community collaboration with Traditional Owners, and their knowledge systems, as a crucial part of such efforts (State Government of Victoria Citation2024).

5. Synthesis

Insights and findings from the three research activities were synthesized based on:

mapping common and contrasting patterns;

deriving insights from three methods, and;

synthesising the insights to identify and develop the dilemmas and recommendations.

As a common methodology across the three stages, we used the coding and thematic analysis to map and identify insights, while the thematic synthesis technique was used for synthesizing all the findings (Thomas and Harden Citation2008; Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

5.1. Three dilemmas

Here, we outline three dilemmas associated with community engagement in urban waterways management.

5.1.1. Dilemma 1. Poor resource management

Whilst our results indicate widespread resources available for community engagement, these are thinly spread across a multitude of activities and tasks, with often an unclear sense of purpose. This is problematic because we found in the case studies that legislative, knowledge and social constraints are associated with involving the community in most actions, including some technical tasks that government agencies are capable of doing (Goodwin Citation2022; Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023). The fragmentation in resource allocation, is recognized as leading to dispersed efforts, lacking economies of scale, potential productivity loss, and undermining meaningful community engagement (Productivity Commission Citation2020; Rushforth and Ruddell Citation2015).

Given the need for strategic focusing of activities, the literature review however identified that a top-down approach in resource allocation risks failing to prioritize or even recognize the need for community engagement (Hart et al. Citation2022; Yarra Citation2016). The case study confirmed a strongly top-down approach in the allocation of resources. The policy review also highlighted that fragmentation in the governance of waterways tends to limit the opportunity for achieving the strategic focus, and critical mass required for enabling effective CEUWM.

There is also a disconnect between legal mandate and responsibility, and the allocation of resources to fulfil such responsibilities (City West Water Citation2020; Melbourne Water Citation2021–Citation2022). The case study sheds light on the variable nature of institutional resource allocation, driven by factors like urgency, project scale, politics, finances, and stakeholder priorities. The policy review highlighted the disparities in resource allocations among councils and local government agencies, shaped by distinct priorities, capabilities, and statutory roles. This series of issues underscores the intricate social-institutional dynamics influencing resource distribution and explains why resources are generally stretched rather than insufficient.

Planning documents highlight diverse priorities, approaches, and communication channels among groups, hindering the establishment of a unified and collaborative community engagement strategy (Victorian Auditor-General Citation2017b; Loo and Clarke Citation2017).

The ‘top-down’ resource allocation approach in community engagement practices and UWM policy emphasizes collaborative principles and targets over innovative co-management of resources (Hart et al. Citation2022). This emphasis on collaboration, coupled with the lack of legislative powers to support collaborative governance models, like catchment management committees (which are in practice controlled by high-powered organizations), exacerbates resource-related challenges. The inadequacy of resources results not only from insufficiency but also from the failure to strategically allocate resources, prompting a rushed demonstration of engagement without meaningful consolidation of efforts.

5.1.2. Dilemma 2. Lack of focus

It is clear from our results, especially from the literature and the case study, that community engagement is not a panacea for urban waterways governance, especially when its implementation is often inadequate (Raitakari, Juhila, and Räsänen Citation2019; Smith Citation2008; Hart et al. Citation2022). The literature underscores a tendency of widespread superficial understanding of engagement, overlooking its inherent complexities, meaning it’s viewed a bit like a silver bullet without consideration for the difficulties of ‘doing it well’. In the same vein, government agencies, motivated by expediency, frequently delegate tasks to communities without strategic alignment (Bajracharya and Khan Citation2020; Howard Citation2017).

The lack of focus also extends to a common lack of clarity as to legal or institutional priorities and responsibilities, as well as legislative and policy commitments (for example, in relation to traditional owners’ aspirations and rights). Such contextual background is critical as a foundation for designing effective participation mechanisms and needs to be both clearly communicated as well as embedded into goals and visions.

The case study findings further highlight that community engagement sometimes can be aimed simply at fulfilling bureaucratic and or regulatory goals (box-ticking exercises) rather than inviting the community to fulfil more substantive roles in shaping waterways governance. This becomes particularly problematic if such goals are not clear for participants from the outset.

But what should the roles and responsibilities of the community be? Reviewed policies expose ambiguities in the definition of community roles and responsibilities, lacking clarity and legal mandates, thereby meaning that government institutions may choose to ignore the community at will. Without clear and well-resourced roles, responsibilities, or tasks for the community, we argue that this quickly becomes impractical as resources become stretched, motivation for participation erodes, and engagement becomes limited.

What we found was that the current process of developing visions and goals (a critical role for the community) allowed diverse communities to share their needs and aspirations, as identified in relevant policy documents (Melbourne Water Citation2018a), and this has improved the level of collaboration. However, we also found in the case studies that community inputs, especially their aspirations and perspectives, were not adequately reflected in the adopted visions, goals or KPIs.

5.1.3. Dilemma 3. Effectiveness depends on implementation and context

As a third dilemma, we argue that the way that engagement activities are implemented needs to be carefully attuned to context (place, culture, values, institutions, available knowledge, etc). If not, effectiveness of the implementation is significantly at risk.

Related to this dilemma is a tendency to over-rely on formal methods, whilst not recognizing that informal methods can play a key role in processes like trust-building and building an understanding of context. Informal methods can build a foundation for further engagement, and more formal approaches.

This shows the limits of a more simplistic approach, perhaps commonly adopted by decision-makers, of selecting engagement methods based purely on perceived higher levels of participation (as per the IAP2 framework in ), is dangerous, as it fails to acknowledge the need for contextualizing approaches, and the need for more informal methods for building the foundation for engagement in trust building exercises.

Relating to the importance of building the foundation for engagement, in the case studies, we found that the decision-making process had deficiencies in terms of transparency, empowerment and the legal standing of the community in waterways governance.

A symptom of failing to contextualize methods or failing to acknowledge social and relational foundations of engagement (as we observed in our case studies), is that community critiques the engagement approaches based on their lived experience and/or the limits of perceived outcomes.

5.2. Recommendations

As a synthesis and discussion, and to address the identified dilemmas, here we outline four recommendations:

Develop a shared vision and goals as a foundation for engagement,

Be selective about how to engage with the community,

Align methods with goals, and

Ensure outcomes are achieved and legitimate.

These four recommendations, outlined below, holistically address the three dilemmas that we have outlined by focusing limited resources on a smaller set of agreed tasks, thereby winding back engagement levels for areas that are less crucial and expand on tasks with more chance of success and benefit. The way that each of the recommendations addresses the three dilemmas is outlined in .

5.2.1. First recommendation: a shared vision and common goals is the foundation

We suggest that a mechanism to overcome many of the issues outlined in this article, and to lay the foundation for engagement, is to develop a shared vision and associated goals as a foundation for ongoing engagement activities.

A shared vision is a collective goal or aspiration that unites diverse stakeholders around a common purpose so that everyone is connected (Steins and Edwards Citation1999; Murphy et al. Citation2022). It acts as a guiding process, motivating individuals and communities to collaborate and work towards a desired common future (Murphy et al. Citation2022). Further, clear vision and goals provide a clear direction to reframe the roles and responsibilities of actors and more effective use of resources.

We suggest three considerations for developing shared visions and goals for urban waterways management. First, engaging communities in decision-making processes, such as developing shared visions and goals, needs to be based on higher levels of participation (as per the IAP2 framework, see ) to foster motivation and responsibility. Participatory visioning and goal setting holds immense power as it empowers individuals and communities to shape their future (Pelling et al. Citation2023; West and Michie Citation2020). Involving all relevant stakeholders ensures diversity of perspectives, fosters inclusivity, and promotes transparency and accountability (Correia et al. Citation2023). Participants feel a sense of ownership and commitment, leading to increased motivation and cooperation (Nourikia and Zivdar Citation2020). Additionally, participatory goal setting enhances the relevance and feasibility of objectives, aligning them with the real needs and aspirations of the people involved (Pelling et al. Citation2023). As a result, it drives more effective decision-making, resource allocation, and implementation, ultimately leading to sustainable development, stronger partnerships, and positive societal transformations (West and Michie Citation2020; Pelling et al. Citation2023; Cernesson et al. Citation2005).

Second, this process must align with the values and aspirations of the local community and should be based on ongoing conversation with them. Recognizing and incorporating the cultural, social, and economic aspects and values of the community will enhance the vision’s relevance and acceptance (Hardy Citation2022; Rădulescu, Leendertse, and Arts Citation2022). To support this ongoing conversation, it is important that there are supporting communications that allow the community to be regularly updated on how their contributions are being used to realize the shared vision.

Third, the shared vision and goals should be regularly monitored, updated and be adaptive and practical for the most significant social-ecological changes (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. Citation2000; Davies and Dart Citation2005). Doing this using participatory methods helps ensure these are shared visions, goals, and even associated metrics for monitoring progress, developed in a transparent and legitimate fashion (Hardy Citation2022; Wamsler et al. Citation2020). The learning that this supports has the potential for identifying newly emerged root causes and new patterns of systems behavior that may change the early predictions and provide a platform for community to evaluate and redirect the management actions they are involved with (Pelling et al. Citation2023). Also, monitoring and celebrating progress and achievements helps reinforce the vision and goals and motivate and inspire communities and other stakeholders (Hanlon, Olivier, and Schlager Citation2017). Therefore, integrating participatory monitoring and changes in the visions and goals supports maintaining motivation and impact.

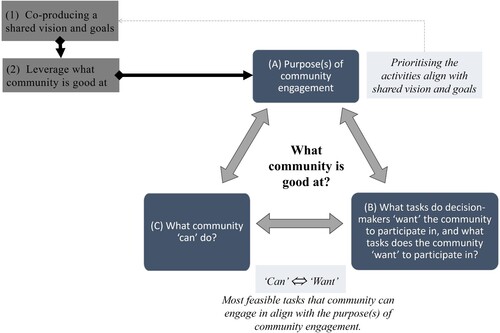

5.2.2. Second recommendation: be selective about how to engage the community

As per dilemmas 1 and 2, it is clear from our research that resources are stretched, many community engagement activities have historically lacked sufficient focus, and effectiveness of engagement requires careful consideration of context (which in turn is often resource intensive). This makes it a rather daunting task to effectively engage with the community collaboratively in every task and role in the management of urban waterways. In fact, it is questionable whether this is necessary at all. This highlights that there is an opportunity to consider the strengths of the community to prioritize efforts on tasks and activities that the community should be involved with.

We also note that as a way to reduce the fragmentation of resources, developing a shared vision (as per recommendation one) can act synergistically with recommendation two to help prioritize resource use more effectively towards key activities.

We identified a dilemma associated with legislative, knowledge, social and funding constraints, which limits the range and scope of activities that communities should be involved in. Therefore, engaging the community in too many roles and tasks in an ad hoc way leads to overwhelmed communities and erosion of motivation. This highlights the need to prioritize what the community should be involved in collaboratively. This would involve developing medium and long-term goals on reframing their tasks and expanding the investments on human, institutional, financial, and technological capacity building.

The literature review also highlighted the need for prioritizing engagement activities that the community can carry out well. However, the insights derived from case studies show that, in practice, the community was invited to collaboratively engage in a large range of diverse activities, irrespective of the strengths, capacities, or willingness of the community.

Therefore, we instead suggest an approach for engagement that leverages what the community can best contribute to in the immediate and medium-term periods. This should consider the available practical resources, i.e., human, financial and technical. The monitoring and evaluation processes highlighted in recommendation 1 can enrich the emergent understanding of such considerations.

To achieve this, we recommend some updates of community engagement plans, which we have seen as at least partially lacking in local policies, regulations, and practices. First, these need to clearly define the purpose of community engagement (see recommendation 1 about developing a shared vision), prioritizing activities or tasks that the community are involved in around these goals (see ). To ensure meaningful and effective engagement in this stage, the community must perceive their involvement as worthwhile and motivated that their inputs will be represented in outcomes (Cernesson et al. Citation2005).

Figure 4. A demonstration of the process proposed to inform the selection of tasks and activities the community should engage in for UWM.

Whilst it is important to focus efforts on what the community is good at, we also acknowledge the need to avoid cherry-picking engagement activities that reinforce existing power structures. To alleviate this risk, the focus of engagement activities should be a joint decision (as per recommendation 1), including not just government or bureaucratic decision-makers, but also community participants. This involves consideration of what government agencies and the community ‘want’, the shared vision, and what community ‘can’ do effectively, meaningfully and feasibly.

Prioritization of community engagement efforts need to consider feasibility. Feasibility here is based on what the community ‘can’ do out of what they ‘want’ to engage in (see appendices for application of this method based on interview data). By ‘can’, we mean the community’s skills, capacities and associated capabilities to contribute meaningfully and effectively to contribute what is ‘wanted’ (Uittenbroek et al. Citation2022). Different community groups or individuals can share their capabilities for implementing a common vision, including time, money, skills, knowledge, information, legal competencies, and influence (Cernesson et al. Citation2005; Vall-Casas et al. Citation2021; Choe and Schuett Citation2020).

We suggest that the prioritization of community engagement activities should be shaped both by consideration of shared goals and visions (see recommendation 1) as well as feasibility. In order to sustain the agency and collaborative culture in the decision-making processes, we suggest the prioritization process should be applied as an adaptive and evolving process (Lindsay Citation2018; Fratini et al. Citation2012; Folke et al. Citation2005). In other words, based on periodical evaluations of impact and feasibility as well as an emergent understanding of the social-ecological system. Whilst this prioritization process may add further bureaucracy, it should also end up prioritizing efforts more effectively towards higher impact activities.

This step may narrow the focus of community participation in the short term. However, we argue it could be a very significant step that could better enable effective community engagement in the long term; and as a way of building motivation and satisfaction within the community.

In addition, establishing participatory approaches and governance models, such as co-decision-making and co-sharing, can enhance the capabilities of human, institutional and technological capacities in the medium and long term (see 5.2.4 for more details).

5.2.3. Third recommendation: align methods with the goals

Once shared visions, goals, and tasks are defined as per recommendations 1 and 2, communities should be actively involved with the set tasks through appropriate participatory methodologies. Knowing that participatory methodologies have strengths and weaknesses (Cernesson et al. Citation2005), it follows that methods need to be chosen carefully to align with the shared vision and goals, but also accounting for context.

The analysis from the policy review indicates that the selection of engagement methods is legitimized to ensure that principles and the appropriate level of engagement is achieved (Victorian State Government Citation2021; Victorian Audtor-General Citation2015). By extension, this also means that the community members should have some degree of freedom in choosing how they would like to be involved. We also noticed a common tension in the choice of methods, between prioritizing diversity/inclusivity of community involvement versus achieving a shared vision and goals.

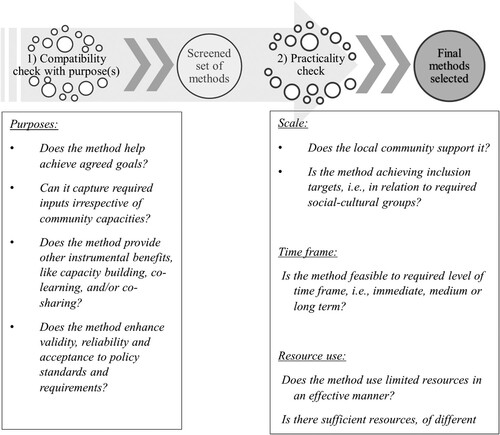

To address this, we suggest that the choice of appropriate methods can follow a two-dimensional approach; leveraging the effectiveness of formal methods, and making them more transparent, transformative and productive (see ) to reduce bureaucratic and organizational biases.

Figure 5. A guideline proposed to choose the best method(s) suited to reach the purpose of community engagement.

The process involves aligning methods with goals and visions and evaluating the practicality of methods. We suggest discussing why the chosen methods should be used and how they facilitate the achievement of agreed goals. Here, decision-makers may consider testing methods recommended by policies and guidelines; either formal or informal.

Chosen methods can be further screened across four perspectives: being, the purpose, scale, timeframe, and resource use. If timelines and resourcing allows, decision-makers should seek inputs and feedback from the communities or community leaders for the assessment, which would both inform the community about resources and limitation, and target the engagement more effectively, particularly in terms of resource use (Cernesson et al. Citation2005; Kiss et al. Citation2022; Raynor, Doyon, and Beer Citation2017).

5.2.4. Fourth recommendation: ensure outcomes are achieved and legitimate

As community motivation is fragile, and because of the importance of not wasting people’s time and resources, it is critical that when the community is engaged, that there is real potential for achieving legitimate impacts, such as influencing decisions or policy. Therefore, once the community engagement plans have been developed, including by describing the roles and responsibilities of communities and how they should be involved, there is a need to ensure that the outcomes are monitored and evaluated, to promote learning.

We also argue that greater focus needs to be put on implementation, social dynamics, understanding place, and context, as the effectiveness of poorly implemented engagement efforts that do not account for context and social dynamics, is highly uncertain.

If outcomes are not sustainability achieved, there may be a need to strategically prioritize dispersed resources and make necessary regime changes to boost the participatory and transformative capacities facilitating shared visions and goals, tasks, and methods. We also note that once agreed visions, goals, roles, and methods are in place, it is easier to mobilize limited and additional resources (Goodwin Citation2022; Kahui Citation2022; Cernesson et al. Citation2005).

Here, we also note the importance of flexibility and adaptability. For example, an event such as an acute river flood may impact the need for changes in outcomes in terms of delays or raising new focuses to achieve instead of giving priority to achieving already set outcomes.

5.2.5. Strategic resource allocation

A key part of ensuring that outcomes are achieved is to prioritize and manage the resources and to use the most effective methods, as per recommendations 1–3 (Wiset et al. Citation2023; Head Citation2007). This approach allows the allocation of resources for the most viable and transformative community engagement actions and methods to engage the community. Under this approach, decision-makers can target resources towards the most impactful actions or best options, leading to achieving the intended purposes successfully (Head Citation2007; Hardy Citation2022). This practice allows for efficiently mobilizing available resources for the best outcomes and expanding the capacities and resources for the next medium or long-term transformations (Ojha et al. Citation2016). We also note that, as identified by interview informants, the strategic prioritization should also consider investments in capacity, for example by enhancing skilled labor and financial assets.

5.2.6. Legitimacy building

We note that most of the communities, even for community groups like ‘friends of’ groups, have limited or no legal access to intervene in crucial decisions or influence the final stages in the decision-making process (Perera, Moglia, and Glackin Citation2023; Hardy Citation2022). This may, in many instances, be appropriate, but it is worth considering potential changes in community engagement and planning policies and regulations that would allow, to a greater extent, that the diverse community representatives could participate in decision-making (Tirumala and Tiwari Citation2022; Hölscher and Frantzeskaki Citation2020).

Parallel to the changes in policies and regulations, in the context of the case studies, we suggest that there is a need to change local-level governance arrangements to provide the opportunity for communities to have more open and transparent access to be involved in critical steps or decisions we defined above recommendations, as well as an arrangement that legally empowers them to be self-sustained under common rules (Bowen et al. Citation2014; Rees Catalán Citation2015; Goodwin Citation2022).

Further, the insights discussed in the dilemmas revealed that resources are inadequate individually (organizations, groups, committees), and some agencies have enough financial, human and technical resources, while others are lacking (Loo and Clarke Citation2017). It indicates that individual contributions to manage complex issues like urban waterways governance and community engagement are not enough, and it needs more collaborative agreements with clearly stated and empowered through legislation. We see that a governance arrangement without legal responsibilities and power will result in idling financial and human resources and eroding motivation.

In the case studies, we note that the current catchment management committees need to be upscaled into a more special-purpose organization with government organizations’ active representation or perhaps a central body that prepares plans, guides, and monitors the implementation. If so, we suggest such a central body should be empowered with legally assigned roles and responsibilities on preparing urban waterways management plans, cooperating with all other partnered and related agencies’ consensus as a planning authority and guiding and monitoring implementing agencies to execute the common plan. This cooperative body could represent community leaders or champions who can represent diverse communities to link the community into decision-making more effectively and inclusively.

6. Conclusions

Waterways managers in Melbourne introduced a collaborative approach for governing waterways, that recognizes the importance of engaging and involving communities and stakeholders in decision-making processes fostering broader benefits for people and nature. This participatory approach aims to address water-related challenges while fostering a sense of ownership, responsibility, and stewardship among the community members and other partners.

Consequently, policymakers and practitioners often intend to reimagine structural, institutional, policy and decision-making environments to be more inclusive and collaborative. However, many collaborative efforts have achieved less than what they set out to do, largely because decision-makers are bound by institutional complexities, budgets, and organization constraints. This means that not enough attention has been paid to the reality of effectively implementing community engagement processes.

Here we discussed three key dilemmas that we identified in collaborative community engagement practice in UWM in the Melbourne Metropolitan region. We stressed that: resources are stretched; the community is often asked to engage in all aspects of governance and become fatigued; adopted engagement methods are often not fit for purpose;, and effectiveness is highly uncertain when efforts are not made to account for context and social dynamics. As such, we recommended four interconnected strategies to overcome these dilemmas, i.e., there is a need to:

Develop, monitor and evaluate progress towards a shared vision and goals through a participatory decision-making process. This should motivate communities in their endeavors towards a shared vision that everyone is responsible for.

Appraise and focus on the strengths of the community in terms of transformative potential and environmental stewardship to define how to engage community.

Choose purposefully and practically viable engagement methods by aligning with the specific purpose(s), goals and productivity rather than attempting to maximize the participatory level of engagement.

Ensure the desired outcomes are achieved, and the decision-making processes and arrangements are legally enacted to deliver them. A consensus model of governance arrangement and guidance on resource allocation and decision-making that is more targeted.

It is noted that the co-sharing and coordination of resources between the partners through consensus can mitigate resource inadequacy in the long term. At the same time, these arrangements can help to integrate the fragmentation of resources, capacities, roles and benefits into a centred purpose and foster collaborative principles, including transparency, responsibility, ownership and accountability.

To achieve these, we suggest that there is a need for policy changes. Specifically, the local-level community engagement policies should give more attention to enabling clarity and transparency in engagement processes, co-sharing resources, and engaging the community to prepare community engagement plans and actions as a legal requirement. Further, structural governance changes should be revisited to create an institutional space where all the partners can participate in decision-making from project initiation all the way to implementation.

These recommendations need to be further tested, in conjunction with monitoring and evaluation frameworks, so that we can build up the evidence base needed to transform urban waterways governance to be more collaborative and transformative, thereby enabling a range of co-benefits.

Supplement material

Download MS Word (626.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the volunteers who participated in the interviews by providing their valuable time, interest, knowledge, and expertise for the success of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data synthesized in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions and ethical considerations relating to anonymous participation in the interviews.

References

- Agyeman, Julian, and Jennifer Erickson. 2012. “Culture, Recognition, and the Negotiation of Difference Some Thoughts on Cultural Competency in Planning Education.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 32: 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X12441213.

- Angela, Dean, Fielding Kelly, Newton Fiona, and Ross Helen. 2016. Community Engagement in the Water Sector: An Outcome-Focused Review of Different Engagement Approaches. Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities (Melbourne, Australia). www.watersensitivecities.org.au.

- Ariana, Dickey, and Bush Judy. 2021. Sustaining Collaborative Governance: Literature Review and Case Studies”. https://doi.org/10.26188/17149769.v1

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O'Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 4 (35): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Arnstein, S. R. 2019. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 85 (1): 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388.

- Bajracharya, Bhishna, and Shahed Khan. 2020. “Urban Governance in Australia: A Case Study of Brisbane City.” In New Urban Agenda in Asia-Pacific: Governance for Sustainable and Inclusive Cities, edited by Bharat Dahiya, and Ashok Das, 225–250. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-6709-0_8.

- Bokhove, Onno, Mark A. Kelmanson, Thomas Kent, Guillaume Piton, and Jean-Marc Tacnet. 2020. “A Cost-Effectiveness Protocol for Flood-Mitigation Plans Based on Leeds’ Boxing Day 2015 Floods.” Water 12 (3): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12030652.

- Bond, Alan, Jenny Pope, Monica Fundingsland, Angus Morrison-Saunders, Francois Retief, and Morgan Hauptfleisch. 2020. “Explaining the Political Nature of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): A Neo-Gramscian Perspective.” Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 11–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118694. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652619335644.

- Bonney, Patrick, Angela Murphy, Birgita Hansen, and Claudia Baldwin. 2020. “Citizen Science in Australia’s Waterways: Investigating Linkages with Catchment Decision-Making.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 27 (2): 200–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2020.1741456.

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G., M. T. Farvar, J. C. Nguinguiri, and V. A. Ndangang. 2000. Co-Management of Natural Resurces: Organising, Negotiating, and Learning-by-Doing. Heidelberg, Germany: Kasparek Veriag.

- Bos, J. J., and R. R. Brown. 2013. “Realising Sustainable Urban Water Management: Can Social Theory Help?” Water Science and Technology 67 (1): 109–116. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2012.538.

- Bowen, Patricia, John Conallin, Robyn Watts, Anthony Conallin, Josh Campbell, Ian Wooden, Nicole McCasker, Lee Baumgartner, Sasha Healy, and Roger Knight. 2014. “Stakeholder Engagement and Adaptive Governance in the Monitoring, Evaluation and Adaptive Management of Environmental Watering in the Edward-Wakool System.” 7th Australian Stream Management Conference, Townsville, Queensland. https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/10029501/7ASM_p39_Bowen.pdf.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brown, Helen L., Darren G. Bos, Christopher J. Walsh, Tim D. Fletcher, and Sharyn RossRakesh. 2016. “More Than Money: How Multiple Factors Influence Householder Participation in At-Source Stormwater Management.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 59 (1): 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.984017.

- Buntaine, Mark T., Bing Zhang, and Patrick Hunnicutt. 2021. “Citizen Monitoring of Waterways Decreases Pollution in China by Supporting Government Action and Oversight.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (29): 637–670. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015175118.

- Bush, Judy, Barb Miles, and Brian Bainbridge. 2003. “Merri Creek: Managing an Urban Waterway for People and Nature.” Ecological Management & Restoration 4 (3): 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-8903.2003.00153.x.

- Butcher, John R., David J. Gilchrist, John Phillimore, and John Wanna. 2019. “Attributes of Effective Collaboration: Insights from Five Case Studies in Australia and New Zealand.” Policy Design and Practice 2 (1): 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1561815.

- Cernesson, Flavie, J. M. Echavarren, B. Enserink, Nicole Kranz, Josefina Maestu, Pierre Maurel, Erik Mostert, et al. 2005. Learning Together to Manage Together. Improving Participation in Water Management. Osnabrück: University of Osnabrück, Institute of Environmental Systems Research.

- Chen, M., X. Qian, and L. Zhang. 2015. “Public Participation in Environmental Management in China: Status Quo and Mode Innovation.” Environmental Management 55 (3): 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0428-2.

- Choe, Y., and M. A. Schuett. 2020. “Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Social and Environmental Changes Affecting Everglades National Park in South Florida.” Environmental Development 35: 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100524.

- City West Water. 2020. Annual Report 2020. Footscray, Victoria: City West Water.

- Coleman, Rhys, Rachael Bathgate, Nick Bond, Darren Bos, Tim Fletcher, Belinda Lovell, Peter Morison, and Christopher J. Walsh. 2016. “Improving Waterway Management Outcomes Through Collaborative Research: Insights from the Melbourne Waterway Research-Practice Partnership.” In Proceedings of the 8th Australian Stream Management Conference, Leura, New South Wales, 31 July – 3 August 2016.

- Colloff, M. J., R. Gorddard, and M. Dunlop. 2018. “The Values-Rules-Knowledge Framework in Adaptation Decision Making: A Primer.” CSIRO Land and Water 57: 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.12.004.

- Correia, Diogo, José Eduardo Feio, João Marques, and Leonor Teixeira. 2023. “Participatory Methodology Guidelines to Promote Citizens Participation in Decision-Making: Evidence Based on a Portuguese Case Study.” Cities 135: 104210–104213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104213.

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Davies, Rick, and Jess Dart. 2005. The ‘Most Significant Change’ (MSC) Technique: A Guide to Its Use”. UK: CARE International. https://resources.peopleinneed.net/documents/192-mscguide.pdf.

- DELWP. 2017. Integrated Water Management Framework for Victoria | An IWM Approach to Urban Water Planning and Shared Decision Making Throughout Victoria. Melbourne: Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (Land The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Water and Planning). www.delwp.vic.gov.au.

- Department of Sustainability and Environment. October 2012. Improving our Waterways: Draft Victorian Waterway Management Strategy. Melbourne: Department of Sustainability and Environment. www.dse.vic.gov.au.

- DEPI. 2013. Improving Our Waterways Victorian Waterway Management Strategy. Edited by Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI).

- Desouza, K. C., and A. Bhagwatwar. 2012. “Citizen Apps to Solve Complex Urban Problems.” Journal of Urban Technology 19 (3): 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2012.673056.

- Dhakal, K. P., and L. R. Chevalier. 2016. “Urban Stormwater Governance: The Need for a Paradigm Shift.” Environmental Management 57 (5): 1112–1124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0667-5.

- Dillon, P., R. Bellchambers, W. Meyer, and R. Ellis. 2016. “Community Perspective on Consultation on Urban Stormwater Management: Lessons from Brownhill Creek, South Australia.” Water (Switzerland) 8 (5): 170–189. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8050170.

- Dunn, G., J. J. Bos, and R. R. Brown. 2018. “Mediating the Science-Policy Interface: Insights from the Urban Water Sector in Melbourne, Australia.” Environmental Science and Policy 82: 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.02.001.

- Dyer, J., L. C. Stringer, A. J. Dougill, J. Leventon, M. Nshimbi, F. Chama, A. Kafwifwi, et al. 2014. “Assessing Participatory Practices in Community-Based Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Community Engagement from Southern Africa.” Journal of Environmental Management 137: 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.11.057.

- Fogg, Alan. 1981. “Public Participation in Australia.” The Town Planning Review 52 (3): 259–266. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40103458.

- Folke, Carl, Thomas Hahn, Per Olsson, and Jon Norberg. 2005. “Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30 (1): 441–473. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511.

- Fratini, C. F., G. D. Geldof, J. Kluck, and P. S. Mikkelsen. 2012. “Three Points Approach (3PA) for Urban Flood Risk Management: A Tool to Support Climate Change Adaptation Through Transdisciplinarity and Multifunctionality.” Urban Water Journal 9 (5): 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2012.668913.

- Glaas, Erik, Mattias Hjerpe, Elin Wihlborg, and Sofie Storbjörk. 2022. “Disentangling Municipal Capacities for Citizen Participation in Transformative Climate Adaptation.” Environmental Policy and Governance 32 (3): 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1982.

- Glackin, Stephen, and Maria Rita Dionisio. 2016. “‘Deep Engagement’ and Urban Regeneration: Tea, Trust, and the Quest for co-Design at Precinct Scale.” Land Use Policy 52: 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.01.001.

- Glasson, John, Riki Therivel, and Andrew Chadwick. 2012. Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment. London, UK: Routledge.

- Goodwin, David. 2022. “Melbourne's Birrarung: The Missed Opportunity for Collaborative Urban River Governance.” Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal 16 (2): 32–52. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v16i2.4.

- Hanlon, J., T. Olivier, and E. Schlager. 2017. “Institutional Adaptation and Effectiveness Over 18 Years of the New York City Watershed Governance Arrangement.” Environmental Practice 19 (1): 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660466.2017.1275709.

- Hardy, Scott D. 2022. “Power to the People: Collaborative Watershed Management in the Cuyahoga River Area of Concern (AOC).” Environmental Science & Policy 129: 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.12.020.

- Hart, Barry T. 2016. “The Australian Murray–Darling Basin Plan: Challenges in Its Implementation (Part 1).” International Journal of Water Resources Development 32 (6): 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2015.1083847.

- Hart, Barry T., Matt Francey, and Chris Chesterfield. 2021. “Management of Urban Waterways in Melbourne, Australia: 1. Current Status.” Australian Journal of Water Resources 25: 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2021.1954281.

- Hart, Barry T., Matt Francey, Chris Chesterfield, Dom Blackham, and Neil McCarthy. 2022. “Management of Urban Waterways in Melbourne, Australia: 2 – Integration and Future Directions.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 28: 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2022.2103896.

- Head, Brian W. 2007. “Community Engagement: Participation on Whose Terms?” Australian Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361140701513570.

- Head, Brian. 2022. Wicked Problems in Public Policy: Understanding and Responding to Complex Challenges.

- Healthy Waterways Strategy. 2023. “Healthy Waterways strategy 2028–2028: Port Phillip and Westernport Victoria.” Healthy Waterways Strategy. Last Modified 03.2023. Accessed 09.02.2022. https://healthywaterways.com.au/.

- Hölscher, Katharina, and Niki Frantzeskaki. 2020. “Transformative Climate Governance: A Capacities Perspective to Systematise, Evaluate and Guide Climate Action.” In Palgrave Studies in Environmental Transformation, Transition and Accountability. 1st ed., edited by Beth Edmondson. Cham.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howard, Tanya M. 2017. “‘Raising the Bar’: The Role of Institutional Frameworks for Community Engagement in Australian Natural Resource Governance.” Journal of Rural Studies 49: 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.11.011.

- IAP2. 2019. “The International Association for Public Participation - IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum.” International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). Accessed 14.06.2022. https://iap2.org.au/resources/spectrum/.

- Iftekhar, Md Sayed, Joost Buurman, Tommy Kevin Lee, Qihui He, and Enid Chen. 2019. “Non-Market Value of Singapore's ABC Waters Program.” Water Research 157: 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.03.004.

- Kahui, Viktoria. 2022. “Giving Waterways Groups a Role in Regional Freshwater Policy.” New Zealand Economic Papers 57: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/00779954.2022.2150277.

- Kiss, Bernadett, Filka Sekulova, Kathrin Hörschelmann, Carl F. Salk, Wakana Takahashi, and Christine Wamsler. 2022. “Citizen Participation in the Governance of Nature-Based Solutions.” Environmental Policy and Governance 32 (3): 247–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1987.

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O'Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lindsay, A. 2018. “Social Learning as an Adaptive Measure to Prepare for Climate Change Impacts on Water Provision in Peru.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 8 (4): 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-017-0464-3.

- Loo, S. E., and A. Clarke. 2017. “Chapter 14 – The Victorian Waterway Management Strategy.” In Decision Making in Water Resources Policy and Management, edited by Barry T. Hart, and Jane Doolan, 245–264. Melbourne: Academic Press.

- Lupp, Gerd, Aude Zingraff-Hamed, Josh J. Huang, Amy Oen, and Stephan Pauleit. 2021. “Living Labs—A Concept for Co-Designing Nature-Based Solutions.” Sustainability 13 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010188.

- Malekpour, Shirin, Sylvia Tawfik, and Chris Chesterfield. 2021. “Designing Collaborative Governance for Nature-Based Solutions.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 62: 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127177.

- Marlow, David R., Magnus Moglia, Stephen Cook, and David J. Beale. 2013. “Towards Sustainable Urban Water Management: A Critical Reassessment.” Water Research 47 (20): 7150–7161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2013.07.046.

- Measham, Thomas G., Carol Richards, Catherine J. Robinson, Silva Larson, and Lynn Brake. 2011. “Genuine Community Engagement in Remote Dryland Regions: Natural Resource Management in Lake Eyre Basin.” Geographical Research 49 (2): 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2011.00688.x.