ABSTRACT

The compact city agenda aims to deliver sustainable future urban form. However, as with all planning, there is contestation. While built form and housing have primacy, cities need space for hard and soft infrastructural systems, including natural systems that, until recently, have been taken for granted but are diminishing through poorly planned densification. Nowhere is this more evident than in the suburbs, where lot-by-lot redevelopment is significantly reducing open space and tree canopy. Infill developments are not producing the benefits expected from compact cities; they are increasing strain on the grey, blue, and green infrastructure. This paper highlights limited intent in local planning regulations to promote anything other than business as usual, which, in the Australian context, is single lots becoming 2–4 subdivisions. While planning schemes can regulate negative externalities, they do not consider this when taken as a whole, across a redeveloped neighbourhood predominantly consisting of housing, and are not using the redevelopment opportunities to build a more resilient future for local areas. This paper builds on the Australian greyfield literature by showing how statutory amendments can promote precinct scale development, working across multiple lots to deliver housing concurrently with greater levels of amenity for existing and future residents.

KEY POINTS:

Infill housing development on single lots is reducing local amenity while not making the fullest use of the land for housing supply. Site assembly precincts are critical for higher yield, higher amenity, urban redevelopment.

Strategic policy alone will not deliver the solutions; statutory mechanisms for doing so are critical.

This paper presents a fully worked statutory response to the issue, highlighting the method for developing the scheme and the future work necessary for delivering site-assembly precincts at council level.

1. Introduction

Australian state capital cities have defined the proportion of new housing to be achieved within the existing urban boundary, with, for example, Melbourne aiming for 71% infill housing, Brisbane 60% and, Perth 47% (DELWP Citation2017b; GSC Citation2018; WAPC Citation2018).

These policies, as well as market pressures to recapitalise the value of large, low-density, land parcels, have seen significant increases in dwelling densities across all state capital middle-ring municipalities, i.e., the established, built-out, areas where new buildings must necessarily be infill redevelopment housing. For the census years 2006–2021, the average dwelling increase was 20% across middle-ring Melbourne councils, 27% across Sydney councils, and 24% across Perth councils (Glackin, Moglia, and White Citation2024) which show that cities, and importantly, suburbs, are becoming more compact. However, as we will demonstrate, the form of compactness is not ideal.

While redeveloping middle-ring municipalities have contributed to the volume of higher density units, with for Melbourne, roughly 50% of high-rise being outside of the CBD (DELWP Citation2018), a far more insidious outcome is landowner-led incremental redevelopment (Puustinen, Krigsholm, and Falkenbach Citation2022). These are the small, lot-by-lot redevelopments which, though small in scale, account for significant proportions of redevelopment nationally; at nearly 50% of building activity in Melbourne 2006–2014, while only producing 20% of housing net increase (Newton and Glackin Citation2014), making them incredibly inefficient, particularly at a time when housing demand has never been higher (Bleby and Kwan Citation2024). Furthermore, due to the uncoordinated nature of these redevelopments, with planning limited purely to the single lot, the cumulative negative externalists, such as tree canopy removal and near complete build-out, is leading to poor outcomes when considered at the city scale.

Research into these ‘urban greyfields’, i.e., middle ring suburbs going through incremental redevelopment (Newton Citation2010), has shown that land assembly policies combined with precinct scale planning, can increase the volume of housing while reducing the negative externalities of small lot redevelopments. While an extensive literature exists on how to best optimise these smaller sites (Newton et al. Citation2021), little has been published on how to statutorily operationalise the site assembly and precinct scale redevelopment that the greyfields literature promote. This is largely due to the jurisdictional variance in Australian planning regimes across states, combined with the overly technical nature of administering planning regimes, both of which act to prevent its inclusion as academic literature other than at a macro-overview of statutory trends (Hirt Citation2014; Talen Citation2012).

This article addressed this gap by focusing on the statutory mechanisms required to promote land-assembly and precinct scale planning for incremental, but coordinated, housing growth. It argues that, while urban infill is occurring reasonably rapidly, its uncoordinated nature is not producing the volume of housing required, while concurrently eating away at local amenity. As the impactful aspect of planning, where policies are implemented in law, a forensic assessment of planning instruments is required to show how to move forward in this regard. Due to the practical need to work within a jurisdictional framework, this article will focus on the Victorian Planning Provisions. The aim not being to provide a canonical answer to the issue, but to illustrate the mechanism used in one jurisdiction, allowing it to be translated to other state planning frameworks.

The article subsequently explores the nature of landowner-led incremental redevelopment mentioned above. Following this it presents an overview of the Victorian Planning Provisions and the planning instruments available under them. Thereafter, the article presents an assessment of the options for implementation, followed by the actual tools used for an amendment. The discussion comments on the practical outcomes and the work needed to move greyfield precinct scale regeneration from a novel planning approach to a widely accepted planning process capable of drastically improving Australian suburban outcomes into the future.

2. The contested nature of density

56% of the global population currently live in cities, with estimates that by 2050 will become roughly 70% as urban population doubles (World Bank Citation2023). The United Nations has indicated that the urban form best suited to a sustainable future is a compact one (UN Habitat Citation2020). However, it has also expressly stated that compactness needs to address all functional aspects of an urban environment, not simply increasing population densities (UN Habitat Citation2017). This point is spoken to by many critics of compact urbanism, who, while realising that future urban form will be more compact, point to the range of issues that can arise from poorly considered policies, including overcrowding, gentrification, and ecological pressures (Haarstad et al. Citation2023; C. McFarlane Citation2023), and that compact cities generate inequities and are largely resisted for fear of outpricing, congestion, and infrastructural overuse (Wikki and Kaufmann Citation2022). This speaks to the paradox of the compact agenda; in that it promotes the very issues that led to the rise of urban planning in the first place, i.e., negative externalities of crowding, noise, and pollution (Bibri, Krogstie, and Kärrholm Citation2020). There is therefore some debate about compact form and its priorities. Even when considering something as simple as a tree, which is generally accepted as a positive and welcome feature of an urban environment, the space it uses is contested by blue and grey infrastructure, human and building safety (Roman et al. Citation2021), and, of particular importance to this article, residential development, which was shown to reduce tree canopy by 2.8% over 4 years in one Melbourne council alone (Hurley et al. Citation2019). Compactness is therefore a contested space, needing far more consideration than simply the addition of new dwellings.

Exploring the form that residential infill takes locally, illustrates a common redevelopment typology, albeit a large one, on a single lot. In this instance, the near complete removal of permeable surfaces and the site dominated by driveway and two-storey housing can be seen. Minimal space has been retained for vegetation, including canopy trees, most likely to address statutory requirements for private open space and car parking provision. When taken on its own this simply appears as a redevelopment set out to maximise yield within the building envelope defined by a planning regime. But when the volume of these developments across significant parts of suburbia is considered, it becomes a cumulative issue, compromising the quality of an urban environment.

Figure 1. Housing redevelopment maximising housing yield with no permeable open space. Source: Authors.

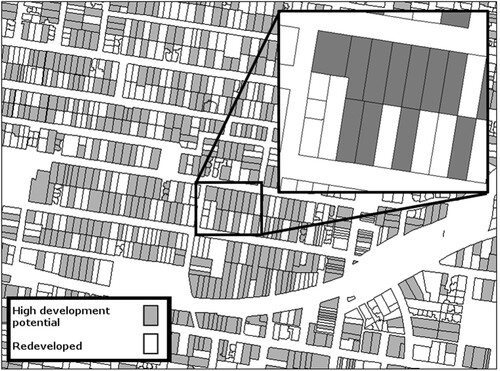

shows a suburban area in eastern Melbourne. Council rates data provides financial metrics on Land Value (LV) and Capital Improved Value (CIV). By dividing CIV by LV an index of 0–1 is created. This index shows the proportion of value in the land alone. The work of Newton and Glackin (Citation2014), who showed that values > = 0.7 are undercapitalised and highly re-developable, identifies which lots have been recently redeveloped or improved and which lots are immediately re-developable. The lighter land parcels (comprising 37% of the lots) have been redeveloped or significantly improved to raise their capital improved value. The outcomes for these lots are similar to those of , with near-100% building and driveway surface, tough typically with fewer net dwellings; more in the range of 1–2 or 3, being the subdivision average net increase for this area (Newton and Glackin Citation2014). The darker parcels (63% of the lots) are where the dwelling is worth, at most, 30% of the total value, meaning that the land is, at a minimum, 70% of the total value, which indicates market pressure to redevelop.

Figure 2. A suburb of Melbourne showing all subdivisions, the pervasiveness of high redevelopment potential (in grey) and an inset illustrating the potential for lot-consolidation. Source: Authors.

While not every landowner will want to redevelop, with the Australian housing turnover being at roughly 6% annually (Bloxham, McGregor, and Rankin Citation2010), over twenty years it is expected that almost all land to change hands, which, particularly with these market pressures, could see the majority of land parcels in this area change from single dwellings on large lots to smaller, more compact units on similarly smaller lots. As one can imagine, with density increases of approximately 300%, this type of development outcomes places a heavy strain on the grey, blue, and green infrastructure in an area originally planned for leafy, highly porous, suburban built form (See Hurley et al. Citation2019; Witheridge Citation2024 for volume losses in Melbourne).

This presents the issue of how to manage the contestation between market-led, planning-supported, residential density increases, and the various other systems that allow the city to function, such as urban forestry, drainage, general localised amenity, and so forth. But it also presents an opportunity. Returning to , the inset shows a collection of abutting lots, each of which has high redevelopment potential. If these landowners could be incentivised to sell (or develop) their land jointly, and land assembly was supported by a planning regime that promoted higher densities with greater open space and improved blue/green/grey infrastructure provision, then a balance between the residential and other spatial/planning requirements outcomes could be achieved. Plus, given the reasonably low level of a net increase in typical redevelopment patterns, this system could also begin to incentivise medium-density development, which is largely absent in the Australian context (Parolek Citation2020), and deliver drastically needed new housing; with Victoria (Melbourne) alone needing an additional 2.2 million dwellings by 2051, or 80,000 per year (Victorian Government Citation2023).

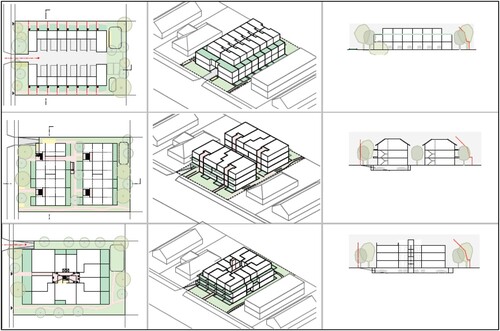

As illustrated by , with a four-lot amalgamation (each lot about 600 m2), development can respond to the regulations’ boundary conditions (front, rear, and side setbacks), allowing for greater interior massing, providing for higher densities over smaller building footprints with reduced site coverage and greater financial returns, while also providing increased permeable surface area and potential for deep-root soil planting on the development site. Given that most single, small-lot development (producing lots <500 m2) maximise non-permeable surface area, while also removing most existing canopy trees, the reduction to site coverage and increase to site permeability and provision for deep-root tree canopy tree planting is a site and ‘precinct additionality’; in that the development positively affects amenity outcomes for the site and surrounding area through greater open space, flood mitigation and increased shade. Furthermore, given the additional massing, density and financial returns, there is also the capacity for the development to achieve precinct additionality for the wider neighbourhood, by utilising some of the additional profits to implement contextually appropriate alterations to the surrounding streetscape and public spaces, to improve walkability or other key localised policy, such as the ‘20-minute city’ policies of Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 (DELWP Citation2017b).

Figure 3. A 4-lot assembly with medium density housing typology and deep root areas allowing for landscaping. Source: Authors.

While this represents an opportunity for better suburban redevelopment outcomes, it does not fit within existing regulations, nor fit to existing subdivision patterns. Site assembly is the only way to achieve typologies such as these, and so site assembly, and the rewards that flow from it, becomes the basis of the underlying regulation.

3. Method and context

With the aim of ultimately rezoning land to promote site assembly, and using a co-design approach to ensure political viability and community acceptance (Glackin and Dionisio Citation2016) the method consisted of four key tasks: (a) precinct identification based on state and local policy priorities, redevelopment potential and multi-criteria analysis; (b) whole of government, community engagement and precinct landowner and resident workshops; (c) precinct and dwelling design optioning, including statutory and financial feasibility; (d) testing statutory responses and encoding the outcomes into the planning regime. Prior to these tasks, and to reduce the chance of project failure due to the lack of political will and policy, as encountered by Rokem and Allegra (Citation2016), McClure and Baker (Citation2018), and the host of applied urban research that fails industry acceptance, a prolonged stakeholder engagement exercise, involving State and municipal government was required, which led to the project’s inclusion in key metropolitan planning strategy (DELWP Citation2017b), the Victorian Planning Provisions (VPP), specifically Section 16.01-1R of the State Planning Policy Framework (Housing Supply – Metropolitan Melbourne) and the Municipal Housing Strategy (MCC Citation2022). This created the policy support for the project, legitimising state and municipal budget and staff time on the project, as well as going some way to ensure the longevity of the project through to fruition and implementation.

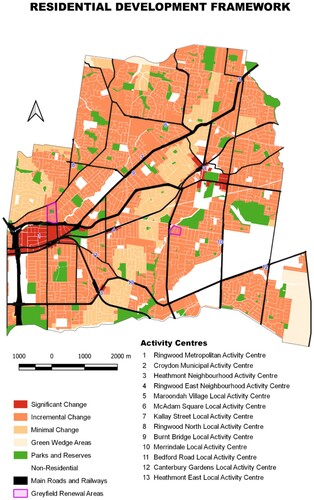

The methodology aimed to ensure alignment with the local spatial planning framework, which in relation to housing at the municipal level is the Residential Development Framework Plan (). During the process of preparation of the Housing Strategy for City of Maroondah, locations were identified with areas of significant, incremental, and minimal change. The greyfield precincts identified were within significant or incremental change area. Clause 16.1 of the Maroondah Planning Scheme lists the location for housing and mixed-used development opportunities and include greyfield precincts.

Figure 4. Maroondah residential framework, illustrating the strategic vision. Source: MCC (Citation2022).

The first task used a multicriteria analysis tool (See Glackin Citation2012, for full system specification), comprised of financial data for house and land value, housing stock age, as well as locational and demographic attributes relevant to redevelopment, such as access shops and public transport, to define areas of high redevelopment potential; i.e., areas with clusters of under-capitalised land with good access to services. This provided mapping data for the initial discussions with council and community members.

To ensure that the multicriteria analyses considers the local context, variables were weighted based on the community priorities identified through range of community consultation activities at the municipalities. In relation to housing, the Maroondah residents wanted the housing now and, in the future, to be close to public transport and the local shops, parks and playgrounds. These community priorities were in line with the findings of the Maroondah Liveability Wellbeing and Resilience Strategy 2021–2031. The strategy identified the communities desire for development of 20-Minute Neighbourhoods and proximity of housing near the facilities and community services, parks and playgrounds, shops and businesses, accessibility and amenities, open space and green space, public transport, walkability, all contribute to liveability in Maroondah. Variables for these community priorities were assigned a higher weightage in undertaking multicriteria analyses.

In addition to considering community priorities for the allocation of appropriate weighting for multicriteria analyses for precinct selection, internal discussions with several Council teams were undertaken to understand community infrastructure issues and opportunities and the capital works programme to help identify priorities precincts.

One of the actions in the Maroondah Housing Strategy refresh 2022 recommends greyfields renewal based on appropriateness of location and the owner interest.

The second task used the first output to jointly work with council and community members to define the location of pilot areas as well as the localised needs of each site, under the assumption that each area should have at least one, if not two or three, factors that needed addressing in terms of contestation of space. This process required a whole of local government response, to capture the varied needs of each local area across sectors, such as parking, canopy tree loss, flooding, service access and, so forth. Similarly, to capture the varied responses from the community, a community advisory group was pursued, necessarily comprising the interests, values and concerns of the areas, including representatives from nature and sustainability groups, real estate agents, developers, and affordable housing advocates. The aim of these joint, and iterative, processes was to finally settle on two pilot precincts, ensuring that they were viable in terms of community and political acceptance, and advanced local policy, in that the proposal would support contextually appropriate local area improvement. The full process, including the iterations based on the following task, can be found in Newton et al. (Citation2021).

The third task was, in a similar charettes and co-design approach taken in Murray et al. (Citation2013), to iterate on stakeholder suggestions to begin designing the pilot precincts to incorporate local area improvements, as well as to test the existing statutory context and financial limitations of housing typologies, new open space requirements and the range of other precinct needs relative to planning requirements and financial feasibility. The product of this stage provided the site coverage and permeability, building heights and setbacks, off-street car parking, open space and landscaping parameters, as well as costed local area improvements, becoming the evidence base on which the statutory planning mechanism could be set.

The final task was to find the best path to planning implementation; using the complete set of data produced from community and stakeholder engagement, iterative design and feasibility work, and further stakeholder engagement with state planning regulators, as well as the political elements of state and local planning (councillors and ministers), to provide a codified solution to land assembly, increased dwelling increase, and precinct additionality simultaneously.

3.1. Context

The core partner municipality was Maroondah City Council; 25 kilometres east of central Melbourne. With a population of 115,043 (ABS, 2022), and an area covering 61 km2, it abuts a semi-rural municipality to the east and north and is an archetypical Australian suburban municipality, built along train lines and arterial roads, and with most of its residential stock built in the 1950s–1970s. The average lot size varies from 600 to 850 m2 depending on the suburb, with small pockets of semi-rural 4000 + m2 lots.

Regarding planning regulation, as a federation, and outside of nation-building funding programs for large infrastructure, each Australian state is in control of its own urban and regional planning, with the formation and policing of planning schemes left largely to councils, though approval of the scheme rests with the state and is contingent upon adherence to state directives. State planning authorities create the templates for these schemes and provide the legislative planning instruments available to councils for the implementation of their planning policies. Furthermore, many states also control the overarching directives of the planning scheme, ensuring that local policies speak directly to state policies. As such, Maroondah City Council conforms to the Victorian Planning Provisions (VPP), which are the set of planning instruments available to planners, and to the Victorian State Planning Framework, which sets the states key agendas and priorities (Rowley Citation2017).

Australian planning instruments are prescriptive and largely non-discretionary, setting explicit use and built-form outcomes (England and McInerney Citation2019). A product of this is that zones are nearly universally based on higher-order divisions of use, such as industrial, commercial, recreation, and residential. Allowing for the natural variance across jurisdictional boundaries and urban morphologies, the former land use zones are treated reasonably consistently; defining industrial and commercial use and form that concurs with federal safety codes and the Australian character for commercial buildings. The system for encoding residential zones however is vastly different with, for example, floor (to land) space ratios, and definitions of density (e.g., low-density residential) being typical in New South Wales and Queensland, and numerical density definitions (e.g., R12 – for residential at 12 units per hectare) being typical for Western Australia.

The Victorian planning instruments for residential land use are mainly zones. The General Residential Zone (GRZ) has a maximum height of 11 m (3 stories) with potential to varied to 4 storeys and allows for modest incremental residential infill. The Neighbourhood Residential Zones (NRZ) has a maximum height is 9 m (2 stories) and aims to minimise change in areas deemed sensitive for a range of potential reasons (e.g., heritage and/or environmental characteristics). The Residential growth Zone (RGZ) aims generally for a maximum of 4 stories (13.5 m), though heights and setbacks can be altered significantly in schedules and separate provisions to accommodate the local ‘growth’ context. Other zones exist that can accommodate residential, such as the Mixed-Use Zone and Activity Centre Zone, but prioritise supportive mixed-use development over purely residential. Low Density Residential Zone and Township Zone are typically reserved for semi-rural and rural and regional contexts.

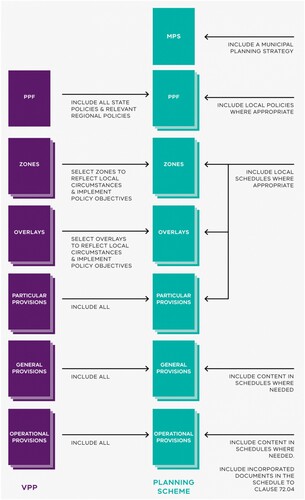

Additionally, Victoria also has a system of ‘overlays’, which are additional instruments for specific contexts, such as protecting and enhancing site and design characteristics, managing land (e.g., through applying development contribution or incorporated plans), altering car parking provision and so forth. While the zones focus on land-use first and then built form, overlays prioritise built and natural form. In terms of cross jurisdictional translation, South Australia has a similar planning instrument (PlanSA Citation2024), but overlays speak more to the Special Control Areas in Western Australia (for example, Department of Planning Lands and Heritage Citation2022, Part 5) and Development Control Plans of New South Wales (for example, City of Sydney Citation2024). An overview of the Victorian planning scheme, including additional specific and general provisions in built form, is provided for clarity and reference in .

Figure 5. A graphical overview of the Victorian planning scheme (DTP Citation2022), showing state input (left to right) as the Victorian Planning Provisions, and municipal input (right to left) to build the local planning scheme. MPS is the Municipal Planning Strategy which is informed by the PPF, the (State) Planning Policy Framework, containing the state level strategies, aims and priorities that councils must speak to in their local plans.

The current residential zones were established by the Minister for Planning in 2014 after a seven year, highly debated, review (DTPLI Citation2014). This review aimed to reduce community concern regarding over-development and locate larger developments in locations deemed appropriate, as well as reform the existing zones to meet new state planning objectives. A report on the roll-out of the new zones found that the ‘growth zone’ was underutilised while the ‘neighbourhood zone’ was being overused for protectionism, to the point where redevelopment was largely limited to transit routes only (DELWP Citation2016). A recent statement by the Victorian Premier (Victoria’s Housing Statement), and in reference to a dire housing shortage, notes the need for an addition 800,000 homes over the period 2024–2034, with the chief levers being planning and partnership reform, which suggests that state authorities clearly recognise the need for new planning tools and approaches to increase housing density. Additionally, state planning authorities have recently released the results of the Future Homes program (DTP Citation2023a), which provides apartment building designs for lots of approximate 1000 m2 or greater (i.e., an assembled site) that accommodate open space and deep root planting zones for improved landscaping outcomes, but purely on site, rather than at a precinct scale. The Future Homes program formed part of Victoria’s Housing Statement and has since been incorporated into the Particular Provision of the VPP. The Future Homes provisions provide for the construction of 4–5 storey apartment buildings within a range of accessible locations (e.g., within 800 m of a railway station or metropolitan, major or neighbourhood activity centre), subject to a streamlined assessment process. Future Homes developments are prohibited from locations within a Heritage or Neighbourhood Character Overlay. These recent designs, and the Future Homes program overall, indicate the need for housing, planning reform and the increased awareness of the benefits of site assembly within the Victorian planning community and throughout Australian capital cities more broadly.

4. Results

As the focus for this article is the statutory planning aspect of the research, this will be the focus for this section. However, background research outcomes leading to this point, and following the methodology section, will be briefly presented for scene setting.

4.1. Non statutory outcomes

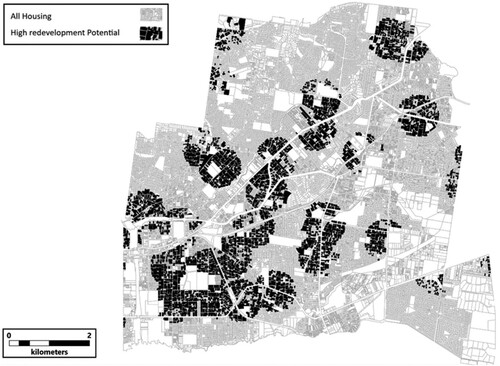

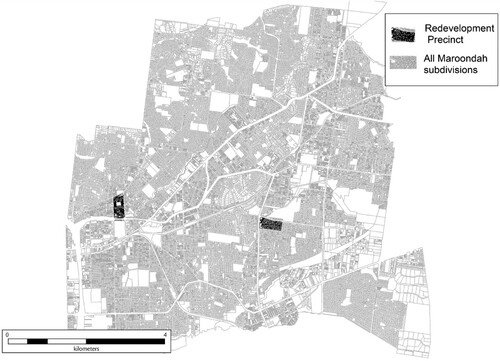

The first task required identifying potential redevelopment precincts based on housing valuation data, combined with data on access to services. Working iteratively with council officers on the selection of the most relevant variables, and their weighting in terms of significance, resulted in a simple outcome where parcels with high redevelopment potential within a 500 m buffer of a medium to large shopping precinct were selected. While initially the data queries included access to public transport, health care and a range of other services, the municipality, having a car dependent nature, resulting in too few potential precincts. An illustration of the results from the data query are presented in .

The second task required engagement both with council officers and community members, using their combined expertise and local knowledge to identify two pilot precincts. Whole of government workshops, attended by most functions within council (i.e., assets, parking, engineering, planning, open space etc.), resulted in two sets of mapping data. The first identified areas where the concept would have local and political support while the second dually identified where intervention was most needed and the particular local issues the precinct could speak to; for example, in areas where the chance of flooding was higher due to more non-permeable surfaces, the precinct would have to deliver flood mitigation; where private tree canopy was being negatively affected by housing infill some deep root space would be required; and where street parking was becoming problematic due to higher densities off-site (or underground) parking may be needed. This delivered several precinct locations and additionality options. The same processes were run with the community, at both a macro level (at community-wide events) and through a micro-level community advisory group and precinct landowners. The macro-level engagement socialised the concept and proved community support, providing confirmation of key issues of concern to the project team and political assurances to councillors. The community advisory group, over a period of one year meeting monthly, answered similar questions as the council engagement workshops, regarding local political support, appropriate forms of intervention, and the required additionally per area. When overlaid the two sets of data resulted in a full mapping of the area, identifying where the project would work, politically, and what the precincts would have to deliver.

When combined with the initial mapping data from task 1, plus internal council considerations regarding the idealised locations, two precincts, each of around 200 existing lots, became the final decision as to the location of the redevelopment precincts promoting land assembly and multi-lot development with combined precinct additionality ().

Figure 7. Two redevelopment precincts. The first abutting a major commercial activity centre to the west, the second leveraging a minor commercial activity centre to the east. Source: Authors.

Once identified, the third stage of research commenced, where precinct planning began, and new housing typologies were tested against existing statutory regulations and financial feasibilities. This process was naturally iterative, testing various densities and scales of additionality across lot sizes and numbers of combined lots. The product of this was a set of seven design typologies incorporating townhouses and apartments, three of which are represented in across plan, massing, and section. Each is replicable over two or more lots and assessed on frontage, depth, open space provisions, cost/sales, density increase, and statutory change required for their implementation; with them aim being to make this as minimal as possible. They provide the unit level data on which statutory assessment for a future planning amendment was tested.

With the locations for a planning amendment established, as well as built form and feasibility methods created, the final tasks were to, firstly, identify the most effective planning tool for implementation and, secondly, to draft the specifics of the tool to allow for full implementation of the varied outcomes sought for the precincts (as well as for scaling to new precincts if successful). This required testing all avenues, including the creation of a bespoke tool, hard encoding through a zone, or using a design focussed tool (locally termed an overlay). Given the complexity of the exercise, an overview of the statutory possibilities are presented in .

Table 1. Overview of statutory options against key criteria.

4.2. Statutory Scenario 1: a bespoke greyfield precinct zone

The most optimal proposal was for the creation of a new greyfield precinct specific, land assembly promotion zone. This new planning tool would be a bespoke mechanism allowing landowners/developers significant concessions in height and densities if they adhered to a precinct design brief and utilised the additional financial returns for on-site and off-site precinct-wide infrastructure and amenity. The assumption being that, with larger/amalgamated lots, massing could be centralised, minimising potential amenity impacts from streets. These alterations to the planning regime would then afford additionality such as improved tree canopy, combined car parking areas, additional public and private open space, improved walkability, better connectivity and flood mitigation.

While supported in principle by municipal strategic planners, this prospect was soon proven unviable for several reasons, including the following:

Legal – The Planning and Environment Act 1987 outlines the required statutory process that local authorities must follow to vary, delete, or create new zones (Eccles and Bryant Citation2011, 57). This process involves several stages requiring Ministerial and State planning department approval and adherence. It also requires altering planning regimes at the legislate level, making it highly politicised and bureaucratically cumbersome, and was deemed excessive and unwarranted by state planning authorities, particularly for a pilot scheme.

Cost – A new zone would need to be capable of duplication across all municipal jurisdictions. The cost of submitting one amendment for a municipality, including deriving the evidence base for that amendment and having it externally reviewed could range between AUD $50,000 – $150,000. The final figure for a universally applicable zone is well outside a typical research budget (see Valverde Citation2005 for a full overview of the cost and complexity of land-use change).

Business case – Firstly, aside from some exemplar amalgamation projects (N. McFarlane, Hurley, and Sun Citation2023; Meyer Citation2017), lot amalgamation is still largely outside of ‘Business as Usual’ practice. Secondly, the business processes for implementing lot amalgamation as a municipality, developer or landowner were yet to be established or proved, therefore making it an unviable process for municipalities to supply budget to.

Politics – In 2014, the Victorian Minister for Planning had, in response to a constituency agitated due to the misuse and vagueness of existing residential zones, proposed, and delivered a radical overhaul of the Victorian Planning Provisions, including the introduction of new residential zones. These new zones clearly delineated between areas to be protected from development (Minimal Change Areas), areas where only modest development would be allowed (Incremental Change Areas), and those areas which were ripe for significant redevelopment (Substantial Change Areas). Given the complexity of this process and the resultant significant overhaul of zones regulations in Victoria, any attempt by the Minister to alter the new zones could have resulted in negative media and political coverage.

These factors, and others evident to seasoned planners, made this option unviable.

4.3. Statutory Scenario 2: amending an existing zone

To ascertain the feasibility of utilising existing zones, the second scenario required an assessment of massing and amenity impacts across the sites at higher densities, greater heights and with significant alteration of set-back regimes relative to the existing planning controls. In this instance, existing densities averaged about 10 dwellings per hectare (d/H), ‘business as usual’ subdivisions produced roughly 20d/H and lot amalgamated precinct outcomes roughly 45d/H, moving them into the medium-density arena (noting that medium density outcomes may be far denser closer to the CBD). Based on the set of higher density designs developed by in-house designers, the areas of the planning scheme that required alteration were determined by municipal planners and can be seen in . These variations were further challenged by the fact that a greyfield precinct scheme would only be activated once two or more landowners took avail of the amalgamation process. As such, the process was entirely voluntary. Any new controls introduced through the new schedule to the General Residential Zone (typical residential) would need to cater concurrently for potential development on the original/existing lots (single/non-amalgamated lots below a specific size) and amalgamated lots of a range of resultant lot sizes. Lot amalgamation would be incentivised by allowing increased maximum building heights depending on the result lot size.

Table 2. Outcomes from statutory analysis.

As seen in , most issues related to the need for detailed design, heights, site coverage, setbacks, and open space provisions. In addition, to ensure the provision of the desired additionalities, development contributions would likely be required. Furthermore, other than a compulsory 5% developer contribution for open space, the Act does not specifically cover precinct additionality (the off-site additions to the area). These issues were presented to the State planning authority, who advised that:

The alterations to height and setbacks would largely be outside the purpose of the zone, and therefore potentially unethical, as it worked against its intent.

The inclusion of precinct additionality could not be enforced in a zone, as it lay outside of the zone template provided through the Act.

A design-based code (i.e., a design-based overlay) would be a more effective and appropriate means of ensuring delivery of the project.

4.4. Statutory Scenario 3: using adapted overlays

As with zones, an overlay consists of a map and a related ordinance. The map defines the area of affect, and the ordinance defines the regulation applying to the subject land. In the Victorian context, overlays generally speak to a specific context, such as design, heritage, conservation, or environmental outcome (flooding, erosion, toxic soil etc.). The aim of the overlay is (arguably) to provide additional support to the zone for the specific physical context. For design-based objectives and requirements, the two key overlays are a Design and Development Overlay (DDO) and a Development Plan Overlay (DPO).

A DDO is a planning control that is applied to land which requires a specific design and built form response. The purpose of the overlay is to give direction to specific design objectives and built form requirements (e.g., building design, building setbacks, building height, building form). The purpose of a DPO, however, is to identify areas that require the planning of future use or development to be shown on a plan before a permit can be granted. A DPO also exempts a planning permit application from ‘notice and review’ (public notice and review rights through the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal) if it is generally in accordance with an approved development plan. A Development Plan sets out conditions for the new built form. The specifics for such a plan are laid out in a schedule to the DPO. A schedule to the overlay specifies what the Development Plan must include and can include requirements about pedestrian and road connections, where different land uses should be located, and the design of new development on the land, among other issues.

The additionality (community benefit) aspect of the project indicated that the DPO was the most appropriate mechanism for implementation, particularly given that it required a Development Plan, which was not in the scope of the project, but due to it being a requirement of the overlay became one of the research outputs. This will be expanded on in the discussion section below, but, briefly, is indicative of the significance of the statutory environment for implementing and activating research outputs.

The funding mechanism for precinct additionality was also largely defined by state statutory planners, who indicated that the typical mechanism was a Developer Contribution Plan (DCP); a statutory device whereby, through the Development Plan, where densities were pre-calculated, a contribution for each built dwelling contributes towards precinct renewal additionality. Again, this was not a part of the initial proposal, particularly given that DCPs may have a negative connotation in the development community, but state planning regimes indicated a strong preference for this mechanism over other means of collecting contributions towards precinct-level infrastructure improvements.

4.5. Statutory outcomes

Though largely derived from consultant and State planning authority feedback, the jointly derived decisions for the most effective mechanism for greyfield regeneration precincts were to test the application of a Development Plan Overlay and a Developer Contribution Plan for each pilot precinct. Outcomes from the community and stakeholder engagement, and co-design activities were drafted into a visioning plan for both areas, seen in . These plans not only addressed the desired increase in densities but also the required alterations to streetscapes to provide additional flood mitigation, improved walkability, and better landscape outcomes. A range of costing options for each additionality, as well as the hierarchy of importance of each improvement, was derived from consultant and municipal engineers. To promote amalgamation, additional building height was offered for amalgamated lots of a variety of sizes typical of merged lots of two, three and four pre-existing lots. In addition, and significantly, third party appeal rights (from affected landowners and residents), typically provided via the applicable zoning controls, with any resultant appeals managed through the Victoria Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act and associated processes would not be available to submitters if developers adhered to specifications contained within the Overlay and associated precinct design guide. This has been tested with developers who see this as a significant gain, allowing them to better plan their outgoings, construction time and reduce land holding costs.

Figure 9. A precinct with off-site additionality outlined. Source: MCC (Citation2022).

Additional financial feasibilities, exploring the cost of on and off-site additionality, indicated that the developments in Precinct 1 would be achievable for an additional $4,300 per dwelling and $1,000 per dwelling in Precinct 2. These calculations were added to the dwelling feasibility models to assure that the developments remained viable. This process iterated until an optimised feasibility/additionality outcome was derived, indicating that financial feasibility analysis of dwellings and precinct additionality is an integral aspect of the statutory planning process.

Once the Development Plan, including costings, was finalised, it became part of the submission to state planning authorities as part of the proposed planning scheme amendments (one for each pilot precincts). Due to the feasibility analysis, the evidence was also available to create a Developer Contribution Plan. The schedules to the two DPOs (the context-specific ordinance of the Overlays) were derived through an analysis of existing housing types, typological potential future housing types plus analysis of localised contemporary examples of good design. The design guide for the project and the feasibility instruments can be viewed here (www.greyfields.com/resources).

Submissions to the amendments were considered in June 2021 by an independent planning panel arranged by Planning Panels Victoria, the state amendment review body. All data was presented over a 3-day sitting, including supporting representation from community members, indicating the high-level of community support for the project. Prior to approving the amendment, the panel chair noted the lack of precedent for this model, marking it as a novel, and innovative, contribution to urban planning in Victoria, but also the necessity of holistic planning mechanisms such as this as cities become more compact and contested, where dwelling density increases cannot be the only priority.

5. Discussion

Brooks and Lutz (Citation2016) present land assembly as one of the fundamental processes of city building, and without the capacity to reassemble the parcels comprising urban environments, cities will not be able to adjust to new economic and social realities. One of these new realities is reducing sprawl and creating a more compact city. The additional densities achievable with lot-amalgamation have been shown to increase the value of the land somewhere between 15% and 40% (Brooks and Lutz Citation2016; Cunningham Citation2013), so there are clear financial benefits to landowners. However, ongoing workshops with planning consultants and developers suggest that the lot-amalgamation negotiation process and subsequent planning issues can negate this benefit, or make the process so onerous that it is not considered viable by most developers; a fact supported by the ongoing novelty of lot-assembly, the difficulty implementing lot amalgamation policies at the municipal level and the significant volume of literature on holdouts, monopoly rent and other issues relevant to the ‘tragedy of the anti-commons’ debate (Cunningham Citation2013; Heller and Hills Citation2008; Lin, Huang, and Lin Citation2018; N. McFarlane, Hurley, and Sun Citation2023). A further difficulty is the regulatory regime and its inability to support infill (Farris Citation2001), due to zones being (perversely) defined for the current built form – not for the future built form (Talen Citation2012). The rigidity of regulatory compliance can also significantly impede the additional densities required to make lot amalgamation viable, and largely, due to the political nature of land-use planning (for example Jacks Citation2019), preclude the provision of the incentives required to counter the additional cost of land amalgamation. As such, while the financial motivation for land assembly may exist, the context within which it operates (zoning, strategic value, location etc.) largely defines its probability of success and its feasibility.

In the Australian context, the research on infill development has illustrated related issues, resulting in infill targets are not being met by major cities, which is tantamount to a failure of the compact city agenda (Newton and Glackin Citation2014). The work has also illustrated that, of the infill that is occurring, roughly 50% is happening in an ad-hoc manner; producing suboptimum outcomes in dwellings and removing the permeable space required for green infrastructure (Witheridge Citation2024). These outcomes are largely a product of small lot subdivision and the lack of a significant strategic focus on residential infill reform and governance; where piecemeal infill is left to the vagaries of zones that are not fit for infill purpose.

Research was therefore pushed towards identifying and testing the statutory regimes which could potentially implement lot amalgamation, and thus provide both a strategic and a statutory scheme implementable across the wider metropolitan area. As a note, these outcomes would not have occurred without significant academic funding, as its visionary and novel nature would not have attracted the state or municipal funding required. But without the involvement of municipal and state planning staff, the academic aspect would have stifled due to a lack of expertise. The interdisciplinary methodology then speaks to the co-design/deliberative democracy discussion (see Innes and Booher Citation2016), but by necessity, not design. The criticisms of community-led planning methods (Barry et al. Citation2018; Goodspeed Citation2016; Innes Citation2016) still stand, in that it is incredibly expensive and largely outside of the capacity of traditional planners. However, it must also be acknowledged that without the co-design approach, involving community members from the onset, that the project would not have achieved the level of political and community support it has.

Returning to the technical discussion, initial presumptions regarding the statutory scheme were that it would comprise a demarked area, similar to Heller and Hills’ Land Assembly District (Heller and Hills Citation2008), with a tiered height and setback system extending, due to the additional square-meterage, higher than the existing zonal allowances to make avail of internal massing on the larger amalgamated lot. This presumption was invalidated, primarily through the path dependence of established land-use practices (Barnett et al. Citation2015), or, more precisely, to the inability of zones to deal with the complexity of the plans being proposed. Nachman’s (Citation2011) overview of the ability of various planning tools to implement complex outcomes eventually arrives at ‘Overlay Districts’ as the preferred mechanism for implementation, but also illustrates the complexities arising from their implementation. The benefits of the overlay approach are generally to provide a more fluid development outcome than zones, in that they speak to localised and contextual issues, while still providing developers with the up-front costs and expectations. However, to assure viability and to provide an avenue for governance, bespoke particular-provisions need to be applied; similar to Form Based Codes (Council of Mayors (SEQ) Citation2011), but applied to residential as opposed to mixed use. The closest localised (Melbourne) expression of FBC are overlays that either promote specific designs (Design and Development Overlay) or work to a precinct plan (Development Plan Overlay). Through testing the local planning scheme, the research came to the same conclusions as many of the overseas theorists, which is a validation of the project outcomes. By working through all possible solutions our Development Plan Overlay managed to capture value uplift (through lot amalgamation), precinct additionality (through precinct plans – including streetscape), payment regimes (through a costed Developer Contribution Plan), and superior on-site dwellings with options for varied dwelling types (through the incorporated Design Guide). While these instruments worked in the Victorian context, it is assumed that practitioners should be able to interpret the outcomes and navigate their planning instruments to develop similar design-based statutory outcomes (e.g., Special Control Areas in Western Australia and Development Control Plans in New South Wales).

However, our proposed system will function far less effectively than initially hoped. The first issue regarding implementation relates to the nested nature of legislation. An overlay exists as a complimentary tool that delivers specialised controls for specific features or specify preferred design and development intent to the zone. As such, the zone (again, arguably) takes priority and cannot be overridden. This means that, unless the schedule to the zone is varied, heights and setbacks will remain as they are in the underlying zone, regardless of the overlay. This is due to Clauses 54 and 55 in all planning schemes in Victoria, which were developed in 2001 in response to the Good Design Guide for Medium Density Housing (DPD Citation1998) though superseded by Apartment Design Guides (DELWP Citation2017a). The guide was established to promote higher densities and to contain urban growth but led to community anger over development of medium density housing, irrespective of surrounding neighbourhood character. Sections 54 and 55 are therefore based on neighbourhood protection and largely oppose medium density dwellings in suburban environments, regardless of superior design and community benefits.

The second issue relates to the cost of developing precinct plans. To move beyond a concept, and to ensure that a plan has the rigour required to pass the scrutiny of state planning authorities, all assumptions need to be tested and the community needs to be significantly engaged on the potential changes to land-use. Gathering and collating the evidence required for this process is therefore a costly and time-consuming process; one that was initially perceived as far too onerous for municipalities new to the process to consider. With no other options available to the research group, it was the path that had to be followed. However, the cost of developing new precinct plans may be so significant that they may largely void the potential benefits to municipalities. This points to the need for planning reform, as a state-wide approach is needed; one that may make a bespoke greyfield precinct planning zone (or overlay) viable. Though typically a lengthy process, the speed of reform, when properly motivated, can be seen in the Victorian Housing Statement, where all local planning schemes were changed overnight to accommodate the Future Housing designs covered above. While these changes did not promote land assembly per se, they did change the desired location of medium density across metropolitan Melbourne, and created state planning budget to resolve the low supply of new housing (Victorian Government Citation2023).

The final issue is the business aspect of the approach. Though not explicitly part of the planning regime, though the process of making precinct scale development an achievable option for landowners and developers, is far more challenging than just creating a mechanism for its delivery (see Glackin Citation2019). Given that statutory change has been achieved, work is currently underway to develop the process whereby landowners, developers and council can work together, however there are significant issues to resolve.

Noting that this process was only achievable through successive research grants, a key consideration is how to finance the process so it becomes a cost neutral exercise for council (Plan SA, 2024). This is not only critical as the planning stage but also at the implementation stage. Though there are explicit development outcomes for the identified precincts, lot-amalgamation planning is not part of digital fast tracked planning approvals (DTP Citation2023b) and as such could take six months or more for approval. Potentially negating the removal of third-party objections. This will require specialised planning staff to assist with amalgamation subdivisions and development approvals across potentially atypical housing typologies. The issue of rollout and socialisation is also questionable. Given that the benefits of this system benefit all parties (council, landowner and developer) who becomes responsible for what aspects of its delivery? While the outcomes are, as yet, unknown, we are sure that partnerships, variously across state and local planning, developers and local planning, and/or developers and landowners, will be critical for to the process to become viable. These and other matters are the next set of issues that need resolution.

6. Conclusion

The movement towards sustainable solutions for urban planning is fraught with issues relating to path dependency. In a policy and legislative environment where major carbon producing projects are allowed, and major conservation projects are largely ignored, it is highly unlikely that any state government will offer significant support to land-use change for sustainability purposes. As such, the process is, for the moment, reliant on the existing tools for implementation. The work above has illustrated how one project navigated these tools and resulted in the submission for two planning scheme amendments that can potentially promote higher density dwellings on amalgamated lots, while also providing mechanisms for the inclusion of community co-benefit into development precincts. However, it is the first localised attempt at this and may prove less than ideal or, at a minimum, require further refinement when next applied. Furthermore, the scalability, due largely to the cost of the exercise, may not be forthcoming, and if it does so is best placed to come from state authorities. This last point speaks to the significant ongoing funding that was attached to this project, without which it would not have been feasible to fully explore this environment, and without which will no doubt prevent other research agendas, dealing with cross-sector issues involving multiple layers of applied research, from moving to full implementation. Notwithstanding, the aim of the paper has been to show that, though laws and established business models endure, it does not translate to an end to research. Instead, the existing laws, institutional practices and business models need to be queried and utilised to move towards project true compactness, i.e., one where the multi-facetted nature of the city is allowed to co-exist with housing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our funders and contributors to this project. The project was variously funded by the CRC for Spatial Information, the CRC for Low Carbon Living, the Federal Smart Cities and Suburbs program, the Victorian Department of Transport and Planning (DTP), The NSW office of Environment and Heritage, Maroondah City Council and Blacktown City Council. We thank all team members at the DTP and Maroondah Council, as well as the host of community representatives, architects, consultants, developers and legal experts who have assisted us in the development of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnett, J., L. S. Ewans, C. Gross, A. S. Kiem, R. T. Kingsford, J. P. Palutikof, Catherine M. Pickering, and S. G. Smithers. 2015. “From Barriers to Limits to Climate Change Adaptation: Path Dependency and the Speed of Change.” Ecology and Society 20 (3). http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07698-200305.

- Barry, J., M. Horst, A. Inch, C. Legacy, S. Rishi, J. J. Rivero, A. Taufen, J. M. Zanotto, and A. Zitcer. 2018. “Unsettling Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 17 (3): 418–438.

- Bibri, S. E., J. Krogstie, and M. Kärrholm. 2020. “Compact City Planning and Development: Emerging Practices and Strategies for Achieving the Goals of Sustainability.” Developments in the Built Environment 4: 100021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2020.100021.

- Bleby, M., and C. Kwan. 2024. “Housing Targets at Risk as Building Stalls at Decade-low Pace.” Australian Financial Review, January 4.

- Bloxham, P., D. McGregor, and E. Rankin. 2010. Housing Turnover and First-home Buyers. Canberra.

- Brooks, L., and B. Lutz. 2016. “From Today's City to Tomorrow's City: An Empirical Investigation of Urban Land Assembly.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8 (3): 69–105. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20130399.

- City of Sydney. 2024. Development Control Plans. https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/development-control-plans.

- Council of Mayors (SEQ). 2011. Next Generation Planning. A Handbook for Planners, Designers and Developers in South East Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Government.

- Cunningham, C. 2013. “Estimating the Holdout Problem in Land Assembly.” Working paper 19. Atlanta.

- DELWP, Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2016. Managing Residential Development Taskforce: Overarching Report: Residential Zones State of Play. Melbourne.

- DELWP, Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2017a. Apartment Design Guidelines for Victoria. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria.

- DELWP, Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2017b. Plan Melbourne 2017–2050. Melbourne.

- DELWP, Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2018. Housing Outcomes in Established Melbourne 2005 to 2016. Melbourne.

- Department of Planning Lands and Heritage. 2022. City of Fremantle Local Planning Scheme 4. Perth: West Australian Government. https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2023-07/fremantle4-schemetext.pdf.

- DPD, Victorian Department of Planning and Development. 1998. The Good Design Guide for Medium-Density Housing. Melbourne: Victorian Government.

- DTPLI, Victorian Department of Transport, Planning, Land and Infrastrcuture. 2014. Reformed Residential Zones for Victoria: Fact Sheet. Melbourne.

- DTP, Victorian Department of Transport and Planning. 2022. Practitioner's Guide to Victoria's Planning Schemes. Version 1.5. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria.

- DTP, Victorian Department of Transport and Planning. 2023a. Future Homes. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/guides-and-resources/strategies-and-initiatives/future-homes.

- DTP, Victorian Department of Transport and Planning. 2023b. VicSmart Permits. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/guides-and-resources/guides/all-guides/vicsmart-permits.

- Eccles, D., and T. Bryant. 2011. Statutory Planning in Victoria. Sydney: Federation Press.

- England, P., and M. McInerney. 2019. Planning in Queensland: Law, Policy and Practice. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Farris, J. T. 2001. “The Barriers to Using Urban Infill Development to Achieve Smart Growth.” Housing Policy Debate 12 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2001.9521395.

- Glackin, S. 2012. “Redveloping the Greyfields with ENVISION: Using Participatory Support Systems to Reduce Urban Sprawl in Australia.” European Journal of Geography 3 (3): 6–22.

- Glackin, S. 2019. “The Tail Wagging the Dog: Developing Business Processes to Enable Spatial Systems.” In Geospatial Challenges in the 21st Century. Key Challenges in Geography, edited by K. Koutsopoulos, R. de Miguel González, and K. Donert, 385–399. Cham: Springer.

- Glackin, S., and M. Dionisio. 2016. “‘Deep Engagement’ and Urban Regeneration: Tea, Trust, and the Quest for Co-design at Precinct Scale.” Land Use Policy 52: 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.01.001.

- Glackin, S., M. Moglia, and M. White. 2024. “Suburban Futures, Density and Amenity: Soft Densification and Incremental Planning for Regeneration.” Sustainability 16 (3): 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031046.

- Goodspeed, R. 2016. “The Death and Life of Collaborative Planning Theory.” Urban Planning 1 (4): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v1i4.715.

- GSC (Greater Sydney Commission). 2018. The Greater Sydney Plan: A Metropolis of Three Cities. Sydney.

- Haarstad, H., K. Kjærås, P. G. Røe, and K. Tveiten. 2023. “Diversifying the Compact City: A Renewed Agenda for Geographical Research.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13 (1): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221102949.

- Heller, M., and R. Hills. 2008. “Land Assembly Districts.” Harvard Law Review 121 (6): 1465–1527.

- Hirt, S. 2014. Zoned in the USA: The Origins and Implications of American Land-use Regulation. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Hurley, J., A. Saunders, A. Both, C. Sun, B. Boruff, J. Duncan, M. Amati, P. Caccetta, and J. Chia. 2019. Urban Vegetation Cover Change in Melbourne 2014–2018. Melbourne.

- Innes, J. E. 2016. “Viewpoint Collaborative Rationality for Planning Practice.” Town Planning Review 87 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.1.

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2016. “Collaborative Rationality as a Strategy for Working with Wicked Problems.” Landscape and Urban Planning 154: 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.016.

- Jacks, T. 2019. “East West Link: Battle Lines Still Drawn Over Massive Road Project.” The Age.

- Lin, T. C., F. H. Huang, and S. E. Lin. 2018. “Land Assembly for Urban Development in Taipei City with Particular Reference to Old Neighborhoods.” Land Use Policy 78: 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.058.

- McClure, L., and D. C. Baker. 2018. “How Do Planners Deal with Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation? A Case Study in Queensland, Australia.” Landscape and Urban Planning 173: 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.01.012.

- MCC (Maroondah City Council). 2022. Maroondah Housing Strategy – 2022 Refresh. Ringwood, Melbourne: Maroondah City Council.

- McFarlane, C. 2023. “Density and the Compact City.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13 (1): 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221144821.

- McFarlane, N., J. Hurley, and Q. Sun. 2023. “Private-led Land Assembly and Urban Consolidation: The Relative Influence of Regulatory Zoning Mechanisms.” Land Use Policy 134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106904.

- Meyer, G. 2017. Ringwood Metropolitan Activity Centre – Going Places. Planning News.

- Murray, S., N. Bertram, L.-A. Khor, D. Rowe, B. Meyer, P. Newton, S. Glackin, T. Alves, and R. McGauran. 2013. Design Innovations Delivered Under the Nation Building Economic Stimulus Plan-social Housing Initiative. Melbourne.

- Nachman, D. D. 2011. “When Mixed Use Development Moves in Next Door: Find a Home for Public Discourse and Input.” Fordham Environmental Law Review 23 (1): 55–101.

- Newton, P. 2010. “Beyond Greenfield and Brownfield: The Challenge of Regenerating Australia's Greyfield Suburbs.” Built Environment 36 (1): 81–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.36.1.81.

- Newton, P., and S. Glackin. 2014. “Understanding Infill: Towards New Policy and Practice for Urban Regeneration in the Established Suburbs of Australia's Cities.” Urban Policy and Research 32 (2): 121–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2013.877389.

- Newton, P., P. Newman, S. Glackin, and G. Thomson. 2021. “Planning, Design, Assessment, and Engagement Processes for Greyfield Precinct Regeneration.” In Greening the Greyfields: New Models for Regenerating the Middle Suburbs of Low-Density Cities, 135–170. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Parolek, D. G. 2020. Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis. Washington: Island Press.

- PlanSA. 2024. Browse the Planning & Design Code. https://code.plan.sa.gov.au/home/browse_the_planning_and_design_code?PubID=1&DocNodeID=94YEitVdpLA%3D&DocLevel=2.

- Puustinen, T., P. Krigsholm, and H. Falkenbach. 2022. “Land Policy Conflict Profiles for Different Densification Types: A Literature-Based Approach.” Land Use Policy 123: 106405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106405.

- Rokem, J., and M. Allegra. 2016. “Planning in Turbulent Times: Exploring Planners’ Agency in Jerusalem.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (3): 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12379.

- Roman, L. A., T. M. Conway, T. S. Eisenman, A. K. Koeser, C. Ordóñez Barona, D. H. Locke, G. D. Jenerette, J. Östberg, and J. Vogt. 2021. “Beyond ‘Trees are Good’: Disservices, Management Costs, and Tradeoffs in Urban Forestry.” Ambio 50: 615–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01396-8.

- Rowley, S. 2017. The Victorian Planning System: Practice, Problems and Prospects. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Talen, E. 2012. City Rules: How Regulations Affect Urban Form. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- UN Habitat. 2017. Planning Compact Cities: Exploring the Possibilities and Limits of Densification. Seville. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-06/planning_compact_cities_exploring_the_possibilities_and_limits_of_densification.pdf.

- UN Habitat. 2020. The New Urban Agenda. Nairobi.

- Valverde, M. 2005. “Taking ‘Land Use’ Seriously: Towards an Ontology of Municipal Law.” Law Text Culture 9: 34–59.

- Victorian Government. 2023. Victoria's Housing Statement: The Decade Ahead | 2024–2034. Melbourne.

- WAPC, Western Australian Planning Commission. 2018. Perth and Peel @ 3.5 Million. Perth, WA: Western Australian Government.

- Wikki, M., and D. Kaufmann. 2022. “Accepting and Resisting Densification: The Importance of Project-Related Factors and the Contextualizing Role of Neighbourhoods.” Landscape and Urban Planning 220: 104350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104350.

- Witheridge, J. 2024. “Future Challenges and Pathways for Open Space in Australian Suburbs.” PhD, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne.

- World Bank. 2023. Urban Development. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview.