ABSTRACT

Australia is one of the most urbanised countries, and its states and territories are facing significant environmental threats. This paper argues that urban planning authorities in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) repeatedly abandon their carefully crafted urban policies that could have improved environmental sustainability. This qualitative research analyses two cases, nearly two decades apart, to support its argument. In 2021, the NSW planning department developed significant reforms to planning laws, namely the Design and Place State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP). This set of proposed rules would have made planning, placemaking, and communities more liveable and sustainable. In April 2022, the proposed policy was suddenly and unexpectedly scrapped. The recent abandonment of a well-thought-out planning policy proposal in NSW is not unprecedented. It is a case of history repeating itself. In 2003, the PlanFirst sustainability-related planning reforms that had been developed over several years were abandoned similarly. This paper uses the path dependency theory to explore the repetition and discarding of sustainability-related planning reforms. This paper shows how politics and policy making in NSW have neglected significant policies designed to improve environmental sustainability and liveability following property developer lobbyists’ influence.

Practitioner pointers

NSW urban planning has every so often abandoned policies designed to improve environmental sustainability and liveability.

Two case studies show the strong path dependence of NSW urban planning policy reform and the significant influence of the development industry on reform outcomes.

Urban planners and policymakers in NSW need to develop strategies for overcoming path dependency to achieve more sustainable and equitable urban outcomes.

1. Introduction

‘Australia is a majority urban society’, where two-thirds of the population resides in the capital cities (Pill and Rogers Citation2024, 1225). With a majority of Australians residing in metropolitan areas, urban planning policies and their ongoing reforms directly influence the quality of urban development and the experience of city life (Pill and Rogers Citation2024; Tomlinson Citation2012; Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022). Urban planning is essential to managing and making cities, typically involving planning, controlling and implementing urban policy to achieve sustainable urban environments (Sorensen Citation2015; Uddin and Piracha Citation2023). Even though urban planning is well established in Australia, the planning process is continually changing to counter urban challenges (Brunner and Glasson Citation2015).

The largest per capita greenhouse gas emissions are usually from the world’s wealthiest metropolises (Bai Citation2022). In Australia, more than two-thirds of greenhouse gas emanations are linked to urban activities. They increased by 5 to 10 per cent during 2015–2020. In Australia, per capita emissions are alarmingly high in its cities. Australian cities and regions are also at the forefront of the growing threat of severe natural hazards such as floods and fires due to climate change (Bai Citation2022). A recent study reports that a million homes in Australia will be at extreme risk of destructive riverine overflowing by 2030 (Power Citation2022). To what extent and how effectively urban policy tackles urban challenges is a crucial question (Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022). Some researchers have argued that ‘urban policy is part of the problem’ (Pill and Rogers Citation2024, 1227). An essential function of urban policy is to shape a system that lets distinct groups, sectors, and organisations work collectively ‘to plan and build a better city for all citizen’ (Pill and Rogers Citation2024, 1223). However, effective urban policy is further challenged by various obstacles and difficulties (Pill and Rogers Citation2024; Uddin and Piracha Citation2023; Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022).

New South Wales (NSW) is Australia’s most urbanised state, and its capital, Sydney, is a global city. Its urban development began as a British penal colony in 1788. It has grown ever since. The NSW state government is the responsible legislative authority in creating basic settings to ensure a sustainable urban environment. In recent decades, NSW has embraced numerous urban planning policy reforms and strategies in shaping cities. This paper analyses how and why, in NSW, certain planning policies related to sustainability have been developed and abandoned over the years. It examines the influence of the development industry in abandoning these policies. Path dependency in the abandonment of carefully thought-through and well-crafted planning policy reform related to environmental sustainability has rarely been considered by planning scholars who have continued to debate the outcomes of the planning reforms, community participation in planning, urban sustainability and community resilience (Bunker, Freestone, and Randolph Citation2017; Legacy Citation2017; MacDonald Citation2018; Piracha Citation2010; Porter Citation2023; Uddin and Piracha Citation2023; Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022; Williamson and Ruming Citation2019).

Despite numerous reforms, the question remains how far NSW’s planning policies and practices based on the decades of reforms can protect or even improve urban ecosystems. This research argues that NSW’s urban planning policies have repeatedly been unsuccessful in caring for the urban environment. This is due to the focus on faster planning approval, more housing development and industry group influence, and the lack of meaningful measures that could have improved sustainability in urban planning. This paper examines the historical pathways of failure of urban policy related to urban sustainability in NSW through the careful crafting and abandonment of the ‘PlanFirst’ planning reform of earlier in 2001–2003 and the Design and Place State Environmental Planning Policy (D&P SEPP) of 2020-2022.

The NSW Department of Planning introduced the PlanFirst reforms in 2001. The policy was developed over the next couple of years through policy papers and widespread consultation. The policy was to be in operation by July 2007 through related statutory adjustments to the EP&A Act of 1979. The PlanFirst White Paper strategic reform claimed that the modified planning procedure would simplify the planning practice and improve public involvement in planning. The reform initiative also argued that PlanFirst would improve sustainability and strengthen local governments. However, the PlanFirst reform initiative was abandoned in September 2003 due to the industry partners’ concerns.

The Department of Planning announced significant reforms to planning laws in December 2021 to guide NSW’s regional, district and local strategic planning policies. The Minister introduced ‘A Plan for Sustainable Development’ to merge several SEPPs related to sustainability into a single Design and Place SEPP. The reforms were to come into effect on 1 March 2022. However, on 14 March 2022, the planning minister was replaced, and the newly appointed Minister scrapped the former Minister’s reforms due to objections by developers.

Both 2001 and 2021 sustainability-related urban policy reforms were abandoned following pressure from housing and property-related industry partners. This research argues that NSW urban policy transformation follows a path-dependent historic institutionalism – policy practices founded in the past. A historical analysis of urban institutions and policies can better characterise the process of urban development (Pflieger et al. Citation2009).

Path dependence is employed in historical institutional analysis (Fioretos, Falleti, and Sheingate Citation2016). Path dependency is an invigorating concept for interpreting the long-term historical evolution of typical public policy transformation patterns that extend the opportunity for institutional and policy empirical observations (Kay Citation2005). Martin and Sunley (Citation2006, 403) define path dependence and highlight the significance of ‘context, contingency and history’. Path dependency explores how specific political directions, institutional frameworks, and practical actions can produce a policy’s influence and outcomes (Pflieger et al. Citation2009). The concept of path dependency has not often been applied to study urban transformations (Pflieger et al. Citation2009), even though this concept can very well deliver a valuable context to explore how policy development impacts the urban ecosystem (Hensley, Mateo-Babiano, and Minnery Citation2014). Historical policy change trends are crucial to reforming and implementing government policies and legislation.

To date, most analysis of NSW urban policy is centred on neoliberalism, post-politics, public participation and NIMBYism (Bunker, Freestone, and Randolph Citation2017; Haughton and McManus Citation2019; Kent et al. Citation2018; MacDonald Citation2018; Williamson and Ruming Citation2019). However, the significant role of institutional path dependence in influencing urban strategic reforms has yet to receive attention. While urban studies have largely overlooked the concept of path dependencies (Pflieger et al. Citation2009), the idea of path dependence is gradually being applied and is being studied in various urban research areas, especially in urban transportation studies (Sorensen Citation2015). Within the limitation of research on path dependence of NSW planning, Troy (Citation1999) used path dependency to explore the Australian built environment in the post-war period, including in Sydney. Bunker (Citation2012) also explored the path dependency in Australian metropolitan planning. Troy (Citation1999) presented a general overview of path dependency from a social, economic and planning perspective. Hensley, Mateo-Babiano, and Minnery (Citation2014) conducted a review of path dependence literature to gain insights into public health interventions in urban planning, transportation development, and infrastructure improvement. This review established a theoretical framework to inform future practices in public health involvement. Research on NSW urban planning path dependence is vital to identify institutional impediments and policy reform trends.

Australia faces the challenges of climate change, population growth and massive urbanisation, and it is essential to develop urban planning policies that promote sustainability and resilience. However, this will be difficult to achieve if the policy initiatives cannot overcome the dependence on historical paths. Also, past urban initiatives can create lock-in effects, making it challenging to adopt more sustainable alternatives. Additionally, planning institutions and policies can become entrenched, making it difficult to implement new approaches.

This paper begins by articulating research objectives, questions and methodology. Then, it outlines the path dependency concept as it applies to the institutional and policy reform path dependence in NSW planning. The paper then outlines the NSW urban policy reform initiatives from 2001 to 2022 and introduces two policy cases of path dependence. It analyses the established historical context and ways of policy reforms through the examples and articulation from its case studies in NSW to discover the circumstances implicit in the imitation of previous urban planning documents context. It argues that institutional path-dependence actors influence NSW’s policy reform through their established approach and systems.

2. Research objectives and questions

This study examines how path dependence affects urban policy transformation in NSW. It analyses urban planning policies and explores how policy reforms often fail due to being abandoned mid-way through implementation. The study identifies influential urban actors and their impact on sustainability-related reforms in urban planning. The following questions guide this research: How have NSW urban policy transformations followed the path dependence pattern? What association exists between urban planning policy reform and industry partners’ influence? How do the industry actors introduce the path dependency in NSW urban policy?

3. Theoretical context

Urban policy is the state intervention and a technical process of making and implementing plans to administer, manage and function government in cities (Pill and Rogers Citation2024). Urban matters are complicated and very broad (Sorensen Citation2015). Considering the wider aspects of urban studies, this research outlines the vital concept of path dependency for analytical clarity. Metropolises are collective arrangements of institutions, authority, and sets of policies that have been established as a part of attempts to form, accomplish, and improve value in urban areas (Sorensen Citation2015). Institutions or organisations are the key stakeholders in a city. Institutions include political bodies (state government, local government and regulatory agency), economic or commercial organisations (companies, lobby groups), community bodies (community groups or associations), and individual residents (North Citation1990). Each institution and entity attempts to accomplish its objectives in urban matters. Organisations or organised groups can generate obstacles to fulfilling their desired objective.

Institutional analytical philosophy has been used in studying various socio-political and economic issues by the theorists ‘Plato and Aristotle to Locke, Hobbes and James Madison’ to comprehend how institutions develop governmental policy actions (Steinmo Citation2008). The term institutionalism became popular with theorists in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Sorensen (Citation2015, 18) argues that institutionalism is a ‘method that focuses on the creation, persistence, and change of institutions over time’.

The path dependence analytical context is linked to historical institutionalism (Thelen and Steinmo Citation1992). Over the past two decades, theoretical work in the social sciences by Paul A. David (Citation1988, Citation1994, Citation2001), Brian Arthur (Citation1988; Citation1994), Jack Goldstone (Citation1998) and James Mahoney (Citation2000) shaped the theoretical context of ‘path dependency’ that allows the discovery of the historical dynamics and contextual purpose of institutions and policies (Altman Citation2000; Martin and Simmie Citation2008; Pflieger et al. Citation2009). Path dependency is a critical concept and the traditional judgment in historical attempts to investigate and interpret the long-run evenness of paths and insight into social and political practices (Altman Citation2000; Kay Citation2005; Sorensen Citation2015). Path dependency is also a process that controls policymaking choices. North (Citation1990) argues that path dependency is a means to limit the options and connect policymaking out of past decisions that hinder future opportunities for tangible replacements.

Path dependency notion considers institutions as underlying variables that foster or severely restrict the scope, extent, or activity of the organisations and their actors along established paths (Pierson Citation2000; Trouvé et al. Citation2010). Institutions become harsher to shift their practice, values, standards and rules over time (Pierson Citation2000; Sorensen Citation2018) and create a hurdle to modifications in institutional development processes (Altman Citation2000; Pierson Citation2000). Trouvé et al. (Citation2010), citing Palier and Bonoli (Citation1999), argue that path dependence is the historical influence where a chosen path is hard to change because the actions become institutionalised and are upheld persistently. Thus, the path-dependent procedure follows the outcome of the historical reiteration where the processes repeat following the past path (Martin and Sunley Citation2006).

Path dependence theory is established and practised on various frameworks and perspectives. For example, Martin and Sunley (Citation2006) articulate three views of path dependence ().

Table 1. Path dependence viewpoints.

Hensley, Mateo-Babiano, and Minnery (Citation2014) revealed various basics of path-dependence theories ().

Table 2. Various elements of path-dependence theories.

Governments and their regulatory agencies with legislative powers create policies and rules to shape urban areas, strategies, design standards, and manage interaction with public and corporate entities (Evenhuis Citation2017; Sorensen Citation2018). Policy refers to a particular arrangement of laws, obligations, requisitions, and organisations to achieve specific objectives (Kay Citation2005). Governments, cities and urban policies are a more extensive set of institutional setups and complex procedures (Sorensen Citation2018), and indeed, urban planning institutions and their policy practices are often purposefully devised and more challenging to transform (Sorensen Citation2015). In this complex system, urban institutions and their policy procedure often exhibit and practice path dependence (Sorensen Citation2015).

The final concepts that need to be considered in institutional and policy analysis are the institutional actors and their influential powers. The path dependency concept also includes the institution’s arrangements of interests and powers where the organisational actors encourage or constrain policy restructuring (Trouvé et al. Citation2010). Scharpf (Citation1997, 1) argues that public policy selection and legitimation use the powers to achieve goals that are away from the reach of individuals. The private sector’s power in government decision-making is significantly present (Coleman Citation2004). Their influential power motivates the government policy process and empowers corporate partners to ensure their interests (Bathelt and Taylor Citation2002).

Institutions can shape the policymaking process, set the parameters for policy development and implement and enforce policies. Path dependency is an institutional process that creates a lock-in effect, where previous decisions make it difficult to change the course of institutional actions. Institutional actors can lobby for policies that favour their interests, block reforms that threaten their interests, and shape the implementation of policies in a way that benefits them. It can be challenging to build support for reforms that threaten the interests of influential stakeholders. This paper argues that path dependence is a powerful force that shapes urban planning policy in NSW and that institutional actors with influential powers play a crucial role in perpetuating path-dependent outcomes. The subsequent sections outline the evolution of NSW urban planning policy reforms to grasp NSW planning trends and illustrate two policy cases: the PlanFirst and D&P SEPP policy reforms to investigate path dependency in the NSW urban planning policy process. This paper’s NSW urban planning policy path dependency research helps understand and point out the aspects contributing to the phenomenon whereby historical repetitions matter because of resistance to transformation.

4. Research methodology

Qualitative research is a form of in-depth investigation in which investigators represent their practical observations and establish an extensive illustration of the researched topic (Creswell Citation2009). This research adopted qualitative methods to respond to the research questions. Qualitative investigation or analysis generates data from numerous means, such as case studies, conversations, and document analysis (Creswell Citation2009). This research used case studies and content analysis to explore path dependence in NSW planning.

A case study method was chosen in this paper because case studies provide a realistic picture of contemporary endeavours and actions. Rosenberg and Yates (Citation2007) argue that the case study method supports locating appropriate cases to answer the particular research questions. Its procedural flexibility allows the researcher to apply suitable practical research methods (Rosenberg and Yates Citation2007). In addition, publicly accessible qualitative research documents enable the researcher to gather the required data (Creswell Citation2009). Thus, the fundamental nature of a case study and document analysis supports this study in examining the different trajectories in NSW urban policies.

The paper’s methodology consists of two illustrative case studies and document analysis to explain the path dependence in NSW’s urban planning policy. This research has chosen two cases of NSW urban planning policy that were abandoned and followed the same failure process pushed by the industry partners. In conducting this research, various NSW urban policies and related materials were gathered from numerous sources, including government department websites, publicly available media reports, and other web-based search engines, which include 16 Department of Planning discussion papers, reports and brochures, 284 DP SEPP and PlanFirst submissions, 34 media reports and 65 academic sources. This research has used publicly available secondary sources of materials and triangulated them with the support of data, theory and analysis.

5. NSW urban planning policy evolution

Urban planning controls in NSW rest with the state government’s Department of Planning. The NSW the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (EP&A Act) 1979 is the principal law governing the state’s urban planning. It guides planning administration, development proposal evaluations, building approval, planning decisions implementation, and associated planning matters. With the launch of the Environmental Planning EP&A Act, an appeals court, The Land and Environmental Court, was also established in 1979 to regulate land use and planning. This Act introduced new environment conservation and community participation measures related to land-use planning. It also assigned administrative responsibilities to government departments and local government. However, the sustainability and community engagement objectives have not been attained (Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022). Since the mid-1990s, the planning laws have been amended many times to increase the state government’s control over the urban planning process (MacDonald Citation2015; Uddin, Piracha, and Phibbs Citation2022). Statutory mechanisms have been established for directing NSW urban planning and land use, such as the SEPP Exempt and Complying Development Codes, Housing SEPP, Planning System SEPP and Ministerial Directions. The Ministerial Directions is the critical statutory policy that is significant to the paper's arguments and analysis. Under Section 9.1 of the EP&A Act, the Minister can direct an environmental planning instrument, a public authority and any planning decisions to implement or not to implement certain principles, plans, objectives, or rules.

Since its establishment, the NSW state government’s institutional planning framework has been continuously revised for simpler and faster decisions and planning outcomes. highlights the major planning reform from 2001 to 2022.

Table 3. NSW urban policy reform initiatives from 2001–2022.

The NSW government has tried to reform planning policies several times, but many of those efforts fell short. The focus on speeding up planning approvals and promoting more infrastructure and housing development has shaped the state’s planning system over the years (MacDonald Citation2018). Instead of pushing large-scale reforms, the government shifted to smaller amendments to improve planning laws. These changes aimed to simplify the process and create clearer pathways for major urban development and infrastructure projects.

6. Case studies

This section analyses and discusses two cases of policy reform cancellation 20 years apart. The two cases’ institutional paths of failure or evasion are very similar.

6.1 Case 1: PlanFirst 1999–2003

In February 2001, the NSW Department of Planning released ‘PlanFirst: Review of plan making in NSW White Paper’. The PlanFirst white paper argued that the new planning approach would make planning processes easier, increase public involvement, focus on regional planning, and improve sustainability (DUAP. Citation2001). It followed the ‘Green Paper, Plan making in NSW — Opportunities for the Future’, which was delivered for conversation in February 1999. The proposals in the White Paper were the outcome of the consultative process with the key stakeholders and the community (336 submissions) in NSW (DUAP. Citation2001). The consultation results were later also discussed with ten focus groups around NSW. Lastly, the NSW planning department polished all the proposals in dialogue with State agencies, local governments, industry partners, and other stakeholders. In 2002, the then Minister for Planning, Andrew Refshauge, decided to proceed with the reform proposal.

In the PlanFirst process of the reform initiative, the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (DUAP) was reorganised and replaced with the freshly founded ‘Department of Infrastructure and Planning and Natural Resources’ (DIPNR). Then, there was a change in the NSW urban planning leadership, and Craig Knowles replaced Andrew Refshauge on 2 April 2003 as Minister for Infrastructure and Planning. On 12 June 2003, the new Minister announced the formation of a task force on whether the 2002 PlanFirst amendments should be entirely or partially implemented (Khan and Piracha Citation2003). The task force invited various key stakeholders, such as the NSW’s Housing Industry Association, Urban Taskforce, Planning Institute of Australia and Urban Development Institute of Australia, to share their experiences and express their views on the proposed reform (Khan and Piracha Citation2003). The task force also invited written submissions, and iPlan website was created to post interactive comments. They also advertised their initiation in various newsletters. On 1 September 2003, the PlanFirst Review Taskforce handed their ‘Planning System Improvements’ report to the Planning Minister. The PlanFirst review report summarised stakeholders’ main concerns and recommended abandoning most reforms recommended by the PlanFirst White Paper (Khan and Piracha Citation2003). After evaluation, the task force suggested scrapping the whole PlanFirst urban policy reform procedure in September 2003.

6.2. Case 2: design and place SEPP (State Environmental Planning Policy) 2020–2022

Hon. Rob Stokes, MP (Member of Parliament), was the NSW Planning Minister from 2015 to late 2021. In 2020, the Department of Planning consulted with government agencies, councils, peak industry body representatives and various stakeholders on reforming NSW planning policy (DoPI&E Citation2021). The NSW Government’s key objective was to improve the policies and processes to create healthy, sustainable, and thriving built environments (DoPI&E Citation2021). The planning department prepared to explain the policy reform’s intended effect during mid-late 2020. As a vital part of a broad program of changes in the planning system, the Department of Planning planned a broader reform of the D&P SEPP in early 2021. The Minister introduced ‘A Plan for Sustainable Development’ (nine Planning Principles), nicknamed the ‘Nine Commandments’ (Sadauskas Citation2022) that would guide planning policies, making more straightforward rules for urban planning by merging the 45 State Environmental Planning Policies (SEPPs) into only 11 SEPPs clustered by thematic areas. Each one was also connected to one of the planning principles. The new D&P SEPP would merge with the older SEPPs, covering the design excellence of suburban housing and buildings with the Building Sustainability Index SEPP. The Planning Principles were meant to lead urban strategic actions and land use planning and aimed to progress NSW planning policy practices. The Planning Principles’ fundamental goal was accomplishing sustainable development based on the intentions of the EP&A Act 1979. The Planning Principles also advocated that tying with Country and concentrating on climate change is crucial to comprehending sustainable progress and positive socio-economic and environmental values in NSW. The then-planning Minister outlined that a strong relationship with Country should be the key thought when implementing all Planning Principles (DoPI&E Citation2021). From February to November 2021, the Department of Planning exhibited an explanation of the intended effect of producing a D&P SEPP. Over 1,000 people joined webinars and forums to hear about the proposed reform, and 337 written submissions were received (DoPI&E Citation2021). In July 2021, the Department of Planning published the ‘What we heard’ document, which summarised the explanation of the intended effect of the public exhibition response received from the various stakeholders. The Minister identified seven issues that were elevated during the public exhibition for further attention, and the Department of Planning worked with eight internal and external policy working groups, peak industry bodies, and councils to address industry concerns (DoPI&E Citation2021). In addition, four rounds were held, and extended testing and economic modelling were accomplished to consider the critical problems and progress of the policy.

On 2 December 2021, the Department of Planning announced the planning principles, ‘A Plan for Sustainable Development’. As part of the reforms, the Minister also declared that from 1 March 2022, the 54 remaining State Environmental Planning Policies would be merged into 14 policies supporting the nine focal points of the new planning principles. In a sudden change in the NSW government, Dominic Perrottet took over from Gladys Berejiklian as Premier in October 2021. The new Premier made a significant change in the cabinet on 20 December 2021. The planning minister, Rob Stokes, was replaced by Anthony Roberts just weeks after announcing the Design and Place SEPP planning reform. The new Minister announced on 14 March 2022 that the NSW government was not proceeding with implementing the D&P SEPP and retracted the former Minister’s Direction.

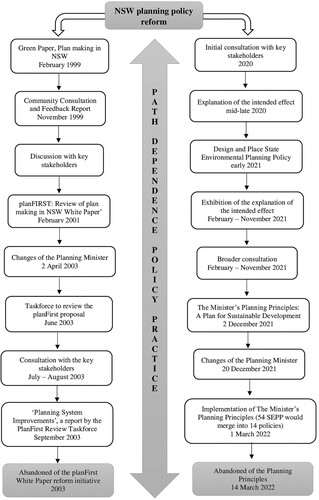

The sustainability-related policy reform initiatives of PlanFirst and D&P SEPP of the NSW planning department followed the same path in their development and abandoning ().

The figure shows that the NSW planning’s path has not changed over time. It highlights that the path of dependence on institutional practice is difficult to shift, and a small previous example can have critical impacts for an extended period of time (Sorensen Citation2015).

The two case studies presented in this paper demonstrate the strong path dependence in NSW urban planning policy reform. The two cases, PlanFirst and Design and Place SEPP were both ambitious reforms that aimed to improve the sustainability of NSW urban development. However, both reforms were cancelled shortly after their announcement, following changes in political leadership and pressure from influential stakeholders. This suggests that path dependence is a powerful force that can constrain even the most well-intentioned reform efforts.

7. Discussion and analysis: well thought support and strong disagreement

The NSW Government’s PlanFirst Green Paper of 1999 labelled five key effects. It highlighted the necessity of reviewing and improving coordination between different levels of government, reducing planning complications by introducing an improved and structured system with a smaller number of plans, better consultation and improved engagement in plan making, efficient land use administration to direct urban development, and effective methods for forming and evaluating plans. However, the government and its institutions outline and control the planning set that structures urban planning, and this process is tremendously path-dependent (Sorensen Citation2018).

The Feedback Report of 1999 highlighted several common themes amongst submissions. These were complications of the existing planning arrangement, the absence of harmonisation between planning rules, a need for clear evidence on the rules concerning land, and a strong demand for increased integration and management in planning (86% of submissions) (DUAP. Citation2001). Several submissions also mentioned making unified regional plans for state and local government, businesses and the community to shape the future of NSW.

It also outlined the need for sustainable outcomes and the environment and community well-being. Most respondents sought to forbid inappropriate development in environmentally sensitive problematic regions and greater independence for local councils in creating their neighbourhood plans. The PlanFirst White Paper of 2001 was a NSW Government proposal to renovate the plan-making approach, increase economic growth and create new jobs, assist in accomplishing an environmentally sustainable future, and strengthen local governments. The then Deputy Premier and Minister for Urban Affairs and Planning mentioned in his forward of the PlanFirst document (NSW Government Citation2001, iii) that,

Planning our future is a very important task. To achieve sustainable jobs, attractive neighbourhoods and healthy environments, we must, as governments, businesses, communities and individuals, work together on a plan for the future of New South Wales. We must PlanFirst … … … . We must work together with a clear vision for the future so we can achieve sustainability in our decisions and actions.

The review report by the PlanFirst Review Taskforce (Citation2003) stated the disagreement with the PlanFirst ideas and, defined it as ‘ambitious’ and claimed that they attempted to move ‘beyond what the environmental planning system could and should do in NSW’ (p.6). The Taskforce report substantially echoed the voice of the dominant industry stakeholders that significantly influenced the developers’ lobby in the urban policy reform process (Khan and Piracha Citation2003). In addition, the key stakeholders asked to be involved in the Taskforce expose a substantial majority of the urban development key stakeholder developers’ lobby group, as three out of the four were from the property development business, and the other is the professional body, the NSW Division Planning Institute of Australia (Khan and Piracha Citation2003). Finally, the PlanFirst review panel agreed with the influential industry partners’ concerns and recommended ditching the reform.

The D&P SEPP was to set ‘sustainability, resilience, and quality of places at the forefront of development in NSW’. It would contain ‘places of all scales, from precincts, large developments and buildings, to infrastructure and public space’. It emphasised the public outer space and aimed to mandate more sustainable materials, plants, parklands, and walkability. It also aimed to increase energy effectiveness and improve building standards, requiring all new houses and renewals over $50,000 to follow the BASIX (Building Sustainability Index) standards.

The D&P SEPP policy aimed to persuade net-zero carbon emissions from ‘day one’ in new commercial buildings and pointed to ensuring an electric vehicle charging facility and necessary tree cover for apartment blocks. The policy mandated ‘comprehensive hazard risk profiles’ for new developments to minimise future dangers involving floods and bushfires. It was the state government’s vital action to realise its 2030 target of 50% carbon emissions reduction on the 2005 levels.

The announcement of the draft D&P SEPP was a substantial landmark in the NSW State Government’s attempts to emphasise the sustainability direction of the state’s planning system. One environmental group described the D&P SEPP as ‘everything you could ever dream about’ (Hannam Citation2022). However, the policy attracted immediate criticism from the development industry, and many felt that the new draft provisions would increase costs and slow down approvals.

In its feedback, the Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA) stated that it is worried the D&P SEPP would increase the duration and expense of new development projects. Thus, it would decrease the housing supply, make housing expensive, complicate the planning system, and shrink innovation in building design. The UDIA stated that even though it ‘does support the effort to develop a principle-based approach to creating a high-quality urban fabric’, the plan would adversely impact housing development by ‘adding time and cost to development and reducing feasibility’ (Sadauskas Citation2022). In an announcement, Urban Taskforce Australia (another developer lobby group) criticised the D&P SEPP consultation system and survey process that directed the formation of the policy, defining it as ‘utopian in its aspiration’. ‘The survey seeks the views of recipients on the design of their home, the attributes of their home and the character of their neighbourhood. But all of this is done without any real focus on the cost of change, the price of the improvements’ (Sadauskas Citation2022). Immediately after the SEPP’s official announcement, the Property Council also expressed their serious objection to the SEPP. The Property Council deemed it to be ‘unworkable’ and a ‘detrimental impact on housing investment, affordability and job creation’ (Perinotto Citation2021). The development lobby did not take long to influence scrapping of the D&P SEPP new policies that would help achieve ‘beauty and liveability’ in NSW’s buildings, apartments and housings (Perinotto Citation2021).

The new Planning Minister, Anthony Roberts, who replaced Rob Stokes, threw out the vast majority of the D&P SEPP. The new Minister kept portions of the SEPP related to enhancing the BASIX (Building Sustainability Index) standard and some more features, but not those policy initiatives that are connected to better housing development and enhanced urban environment, such as tree coverings and open places. The Planning Minister’s decision to scrap most of the SEPP was controversial, and many people criticised the decision for undermining the government’s commitment to improving the quality of urban development in NSW. The Planning Minister’s chosen venue for the SEPP’s abandonment was an Urban Taskforce lunch. Tina Perinotto, publisher and managing editor of the Fifth Estate, wrote:

‘Whether it’s Liberal or Labor, they have the capacity to get to the highest level of government. You know, when do we ever get to see the Premier? The developer lobby can virtually walk into the office and demand a meeting. We’ve been trying to get a meeting with the new Minister for Planning, Anthony Roberts. Nothing. No response since December’ (Perinotto Citation2022).

The developers and their lobby groups are powerful players in NSW urban planning (Uddin and Piracha Citation2023), and the repeated failure presented through the two cases above again outlines their strong influence that forces the planning institution to choose an established path dependence. Rewarding political allies and strengthening their allegiance helps maintain the routine exercise of government authority and industry partners’ influence by repeating a continuous policy failure path dependence (Sorensen Citation2015). The established path dependence urban planning policy practices repeatedly block the sustainability-related reforms that can ensure maintaining a better and safer urban environment in the Australia's most urbanised state of NSW.

Due to the political climate and industry partners’ influence, vulnerable regions and communities are repeatedly placed at the centre of risks of climate disasters and hazardous conditions. As a recent example, ‘the NSW Premier Chris Minns announced plans in December 2023 to build a mini-city and Metro West station at Rosehill Racecourse, paving the way for the Australian Turf Club to sell the place to developers’ (Leeming Citation2024). However, the site is at high risk of flooding, which reminds us of the vulnerability of recent flood disasters NSW faced in the last couple of years. The modelling undertaken by environmental consultancy WSP on behalf of the Department of Planning shows that parts of Rosehill Racecourse, ‘a future site for a mini-city of 25,000 new homes and metro station, could be swamped during major flooding events, with some parts measured unsafe for all vehicles, children and the elderly’ (Madison Citation2024). However, the development prospect creates exciting opportunities for the industry partners without considering the sustainability issues. After the announcement of Rosehill Racecourse development, the Business Sydney Executive Director Paul Nicolaou said in Leeming (Citation2024),

If Sydney ultimately gets the Rosehill Gardens mini-city with 25,000 homes and a Metro station that would be a bonus.

Western Sydney, the largest region in Sydney, is at severe risk of adverse environmental impacts. The area has less annual rainfall and tree canopy coverage than some other areas of Sydney, is significantly hotter in summer, and is strongly affected by natural disasters like bushfires and floods (Farid Uddin and Piracha Citation2023). Western Sydney was the hottest place on earth in 2020 when parts of the Western Sydney region underwent up to 52.0 degrees Celsius (Pfautsch, Wujeska-Klause, and Rouillard Citation2020). Research shows Western Sydney will lose its liveability standards due to high heat (Milton et al. Citation2023). The Western Sydney region is at a higher risk of environmental sustainability. However, Western Sydney, which contains 44% of Sydney’s population, is targeted to accommodate the vast majority of population growth and residential development over the 2021–2041 period (Farid Uddin and Piracha Citation2023; Piracha and Greiss Citation2024).

Avoiding vulnerability to disasters provisions in the D&P SEPP would have helped prevent inappropriate, excessive urban development in Western Sydney. The NSW Planning Minister abandoned the most essentially needed policy two weeks after it came into effect, which would require new developers to consider the floods and fire hazards before constructing new homes. The Executive Director of the Total Environment Centre, Jeff Angel, argued in Perinotto (Citation2022),

Instead of a planning policy that would mandate that new communities would be liveable, walkable, covered by tree canopy for cooling and accessible to transport, there is genuflection to the mantra of the property industry for more supply, faster approvals and cheaper builds.

Australian First Nations people are the world’s oldest, most enduring, and rich culture. Western Sydney has the single largest Indigenous community in Australia. Nurturing Indigenous values and innovation is essential to ensure sustainable socio-economic development (Gyedu et al. Citation2021). The abandonment of D&P SEPP is also a threat to the First Nations people’s ability to maintain their connections with nature. After the announcement of D&P SEPP, the Planning Institute of Australia’s Advocacy and Campaigns Manager, Audrey Marsh, said the elimination of much of the SEPP was a ‘real shame’. She said in Perinotto (Citation2022),

This SEPP went a long way to addressing the urgent issues we have, particularly with urban tree canopy cover and connections between planning and First Nations Peoples and access to open space.

8. Conclusion

This paper outlines how urban planning in NSW has repeatedly abandoned policies designed to improve environmental sustainability and liveability. The policy reforms were developed carefully over a significant period of time, considering sustainable urban development. However, they were abandoned very suddenly and without providing a good rationale for the abandonment. The property development lobby groups were unhappy with them, as they perceived them as additional costs or hurdles in development approvals. In 2022, the Liberal Minister scrapped the necessity to consider the floods and bushfire risks before building new homes just two weeks after it came into effect and while the NSW State witnessed deadly environmental disasters.

The PlanFirst planning reforms developed over the period from 1999 to 2002, with widespread consultation with planning stakeholders and strong sustainability provisions. The then Labour Minister for Planning abandoned them abruptly and rapidly in 2003. Interestingly, the political orientation of the Minister in power, Labor or Liberal, did not matter. PlanFirst was abandoned during Labor times, and D&P SEPP was dropped during Liberal times.

Urban planning that would ensure sustainability ended with disappointment. In addition to being a disappointment and leading to poor planning outcomes, this path is very wasteful. Large amounts of resources go into the development and consultation of these policies. Uncanny similarities can be seen in the careful development of sustainability-related planning policies that address pressing societal needs and desires and the cursory abandonment of these same policies under economic and political pressures.

The two cases and the associated analysis presented in this paper show the strong path dependence in policy reform of NSW urban planning and the significant influence of the development industry in shaping the outcome of reforms. This has implications for vulnerable regions and communities, such as Western Sydney. Urban planners and policymakers in NSW need to be concerned about these challenges and develop strategies for overcoming the path dependency to achieve a more sustainable urban environment. In addition, building coalitions with other stakeholders, such as community groups and environmental organisations, is vital in the policy reform process.

Ethical consideration

This research study used publicly available secondary sources of documents and acknowledged the sources where necessary; thus, no ethical approval was required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Altman, M. 2000. “A Behavioral Model of Path Dependency: The Economics of Profitable Inefficiency and Market Failure.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 29 (2): 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(00)00057-3.

- Arthur, W. B. 1988. “Urban Systems and Historical Path-Dependence.” In Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy, edited by J. Ausubel, and R. Herman, 99–110. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Arthur, W. B. 1994. Path Dependence, Self-Reinforcement and Human Learning. Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Michigan: Michigan University Press.

- Bai, X.. 2022. "What Australian Cities Can do to Pulltheir Weight on Global Warming.” In The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: Fairfax Media. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/what-australian-cities-can-do-to-pull-their-weight-on-global-warming-20220404-p5aajl.html.

- Bathelt, H., and M. Taylor. 2002. “Clusters, Power and Place: Inequality and Local Growth in Time–Space.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 84 (2): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2002.00116.x.

- Brunner, J., and J. Glasson. 2015. Contemporary Issues in Australian Urban and Regional Planning. New York: Routledge.

- Bunker, R. 2012. “Reviewing the Path Dependency in Australian Metropolitan Planning.” Urban Policy and Research 30 (4): 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2012.700638.

- Bunker, R., R. Freestone, and B. Randolph. 2017. “Sydney: Growth, Globalization and Governance.” In Planning Metropolitan Australia, edited by S. Hamnett and R. Freestone, 76–100. London: Routledge.

- Coleman, R. 2004. “Images from a Neoliberal City: The State, Surveillance and Social Control.” Critical Criminology 12 (1): 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CRIT.0000024443.08828.d8.

- Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage publications.

- David, P. A. 1988. Path-dependence: putting the past into the future of economics. The Economic Series Technical Report 533: Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, Stanford University, California.

- David, P. A. 1994. “Why are Institutions the ‘Carriers of History’?: Path Dependence and the Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 5 (2): 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(94)90002-7.

- David, P. A. 2001. “Path Dependence, its Critics and the Quest for Historical Economics.” In Evolution and Path Dependence in Economic Ideas, edited by P. Garrouste, and S. Ioannides, 15–40. Cheltenham: In.: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781950227.00006

- DUAP. 2001. Review of Plan Making in NSW White Paper, 1–65. Sydney, NSW: NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning.

- DoPI&E. 2021. Design and Place SEPP Overview. Sydney: Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. www.dpie.nsw.gov.au.

- Evenhuis, E. 2017. “Institutional Change in Cities and Regions: A Path Dependency Approach.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10 (3): 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx014.

- Farid Uddin, K., and A. Piracha. 2023. “Neoliberalism, Power, and Right to the City and the Urban Divide in Sydney, Australia.” Social Sciences 12 (2): 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020083.

- Fioretos, O., T. G. Falleti, and A. Sheingate. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Goldstone, J. A. 1998. “Initial Conditions, General Laws, Path Dependence, and Explanation in Historical Sociology.” American Journal of Sociology 104 (3): 829–845. https://doi.org/10.1086/210088.

- Gyedu, S., T. Heng, A. H. Ntarmah, Y. He, and E. Frimppong. 2021. “The Impact of Innovation on Economic Growth among G7 and BRICS Countries: A GMM Style Panel Vector Autoregressive Approach.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 121169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121169.

- Hall, P. A., and R. C. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three new Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x.

- Hannam, P. 2022. “Property Developers Fight NSW bid to Make Houses More Energy-Efficient and Climate-Resilient.” In The Guardian. Sydney: Guardian News & Media Limited. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/mar/28/property-developers-fight-nsw-bid-to-make-houses-more-energy-efficient-and-climate-resilient.

- Haughton, G., and P. McManus. 2019. “Participation in Postpolitical Times: Protesting Westconnex in Sydney, Australia.” Journal of the American Planning Association 85 (3): 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1613922.

- Hensley, M., D. Mateo-Babiano, and J. Minnery. 2014. “Healthy Places, Active Transport and Path Dependence: A Review of the Literature.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 25 (3): 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE14042.

- Thelen K., and S. Sven. 1992. “Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis.” In Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis, edited by S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, and F. Longstreth. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kay, A. 2005. “A Critique of the use of Path Dependency in Policy Studies.” Public Administration 83 (3): 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00462.x.

- Kent, J. L., P. Harris, P. Sainsbury, F. Baum, P. McCue, and S. Thompson. 2018. “Influencing Urban Planning Policy: An Exploration from the Perspective of Public Health.” Urban policy and research 36 (1): 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2017.1299704.

- Khan, S., and A. Piracha. 2003. PlanFIRST and thereafter: the process of reforming the planning system in neo-liberal climate. Paper presented at the 1st State of Australian Cities National Conference, Sydney, 3–5 December.

- Leeming, L. 2024. “‘Great Opportunity’ to Redevelop Rosehill Racecourse Hangs in Balance, Premier Chris Minns Concedes.” In The Daily Telegraph. Sydney: NewsCorp. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/great-opportunity-to-redevelop-rosehill-racecourse-hangs-in-balance-premier-chris-minns-concedes/news-story/ff76e1b5851678863a775da8a0bef156.

- Legacy, C. 2017. “Is There a Crisis of Participatory Planning?” Planning theory 16 (4): 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216667433.

- MacDonald, H. 2015. “‘Fantasies of Consensus:’Planning Reform in Sydney, 2005–2013.” Planning Practice and Research 30 (2): 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2014.964062.

- MacDonald, H. 2018. “Has Planning Been de-Democratised in Sydney?” Geographical Research 56 (2): 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12264.

- Madison, M. 2024. “These Maps Show the Risk of Flooding at Rosehill Mini-City.” In The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: Fairfax Media. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/these-maps-showed-the-risk-of-flooding-at-rosehill-mini-city-20240424-p5fm6o.html.

- Mahoney, J. 2000. “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29 (4): 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879.

- Martin, R., and J. Simmie. 2008. “Path Dependence and Local Innovation Systems in City-Regions.” Innovation 10 (2–3): 183–196. https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.453.10.2-3.183.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of economic geography 6 (4): 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012.

- Milton, S., A. Gupta, J. Wang, J. Hartigan, and L. Leslie. 2023. “Why Western Sydney is feeling the heat from climate change more than the rest of the city.” The Conversation, Accessed 28 June. https://theconversation.com/why-western-sydney-is-feeling-the-heat-from-climate-change-more-than-the-rest-of-the-city-201477#:~:text=Western%20Sydney%20is%20home%20to,absorb%20and%20retain%20more%20heat.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- NSW Government. 2001. “planFIRST: Review of Plan Making in NSW White Paper.” In edited by NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning. 1–65. Sydney: NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, NSW Government.

- Palier, B., and G. Bonoli. 1999. ““Phénomènes de” Path Dependence” et Réformes des Systèmes de Protection Sociale.” Revue française de science politique 49 (3): 399–420.

- Perinotto, T. 2021. “New Planning Policy Looks Good for People but Developers are Furious.” In The Fifth State. Sydney: The Fifth State. Accessed Dec 10, 2021. https://thefifthestate.com.au/innovation/design/new-planning-policy-looks-good-for-people-but-developers-are-furious/.

- Perinotto, T. 2022. “Perrottet Plays with Fire as he Lets his Planning Minister Loose with Developers.” In The Fifth State. Sydney: The Fifth State. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://thefifthestate.com.au/urbanism/planning/perrottet-plays-with-fire-as-he-lets-his-planning-minister-loose-with-developers/?utm_source=The%E2%80%A6.

- Pfautsch, S., A. Wujeska-Klause, and S. Rouillard. 2020. “Benchmarking Summer Heat Across Penrith, New South Wales.” In 56. Sydney: Western Sydney University.

- Pflieger, G., V. Kaufmann, L. Pattaroni, and C. Jemelin. 2009. “How Does Urban Public Transport Change Cities? Correlations Between Past and Present Transport and Urban Planning Policies.” Urban Studies 46 (7): 1421–1437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009104572.

- Pierson, P. 2000. “Not Just What, but When: Timing and Sequence in Political Processes.” Studies in American Political Development 14 (1): 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898588X00003011.

- Pill, M., and D. Rogers. 2024. “Urban Policy.” In Australian Politics and Policy, edited by Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh, and Diana Perche, 1222–1246. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Piracha, A. 2010. “The NSW (Australia) Planning Reforms and Their Implications for Planning Education and Natural and Built Environment.” Local Economy 25 (3): 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690941003784291.

- Piracha, A., and G. Greiss. 2024. NIMBYism in Sydney is Leading to Racist Outcomes. Sydney: The Conversation Media Group Ltd. Accessed 5 May. https://theconversation.com/nimbyism-in-sydney-is-leading-to-racist-outcomes-207204#:~:text=Most%20population%20growth%20in%20Sydney,to%20an%20ethnically%20segregated%20city.

- PlanFirst Review Taskforce. 2003. “Planning System Improvements.” In Sydney: PlanFirst Review Taskforce to the Minister for Infrastructure and Planning and Minister for Natural Resources, NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources.

- Porter, L. 2023. “Decolonial Approaches to Thinking Planning and Power.” In Handbook on Planning and Power, edited by Michael Gunder, Kristina Grange, and Tanja Winkler, 165–180. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Power, J. 2022. “NSW Planning Minister Scraps Order to Consider fl ood,fi re Risks Before Building.” In The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: Fairfax Media. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/nsw-planning-minister-scraps-order-to-consider-flood-fire-risks-before-building-20220321-p5a6kc.html.

- Rosenberg, J. P., and P. M. Yates. 2007. “Schematic Representation of Case Study Research Designs.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 60 (4): 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04385.x.

- Sadauskas, A. 2022. “Major Planning Battle Brewing in NSWover Walkable Communities and sus-Tainable Homes.” In The Fifth State. Sydney: The Fifth State. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://thefifthestate.com.au/innovation/design/major-planning-battle-brewing-in-nsw-over-walkable-communities-and-sustainable-homes/.

- Scharpf, F. W. 1997. “Introduction: The Problem-Solving Capacity of Multi-Level Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy 4 (4): 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017697344046.

- Smith, A., and C. Roots. 2024. “Irreconcilable Differences’: Minns Concedes Rosehill City may not Proceed.” In The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney: Fairfax Media. Accessed Feb 21, 2024. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/irreconcilable-differences-minns-concedes-rosehill-city-may-not-proceed-20240221-p5f6o6.html.

- Sorensen, A. 2015. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: An Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30 (1): 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2013.874299.

- Sorensen, A. 2018. “Institutions in Urban Space Land, Infrastructure, and Governance in the Production of Urban Property.” In The Routledge Handbook of Institutions and Planning in Action, 74–91. New York: Routledge.

- Steinmo, S.. 2008. “Historical Institutionalism.” In Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective, edited by D. Della Porta and M Keating, 118–138. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Tomlinson, R. 2012. “Introduction: A Housing Lens on Australia's Unintended Cities.” In Australia's Unintended Cities: The Impact of Housing on Urban Development, edited by Richard Tomlinson, 1–18. Victoria, Australia: Csiro Publishing.

- Trouvé, H., Y. Couturier, F. Etheridge, O. Saint-Jean, and D. Somme. 2010. “The Path Dependency Theory: Analytical Framework to Study Institutional Integration. The Case of France.” International Journal of Integrated Care 10: 1–9.

- Troy, P. 1999. “The Future of Cities: Breaking Path Dependency.” Australian Planner 36 (3): 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.1999.9665751.

- Uddin, K. F., and A. Piracha. 2023. “Urban Planning as a Game of Power: The Case of New South Wales (NSW), Australia.” Habitat International 133: 102751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102751.

- Uddin, K. F., A. Piracha, and P. Phibbs. 2022. “A Tale of two Cities: Contemporary Urban Planning Policy and Practice in Greater Sydney, NSW, Australia.” Cities 123: 103583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103583.

- Williamson, W., and K. Ruming. 2019. “Can Social Media Support Large Scale Public Participation in Urban Planning? The Case of the# MySydney Digital Engagement Campaign.” International Planning Studies 25 (4): 1–17.