ABSTRACT

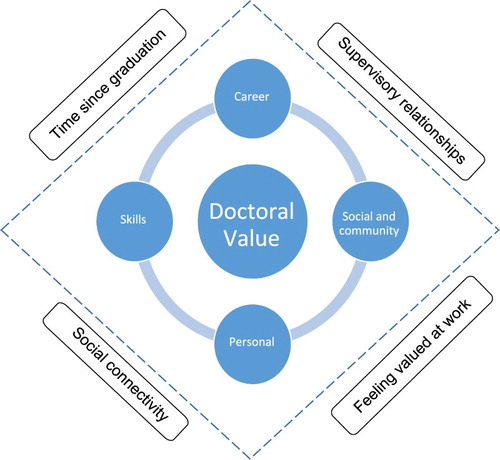

The recruitment of doctoral graduates yields collective knowledge, skills, networking, and prestige benefits to organisations, and to UK industries. As individuals though, do graduates experience overall benefit from their doctorate, and how do they perceive the value that engaging with doctoral study confers? This interview study used a critical, interpretive lens to examine perceptions of value across experiences of doctoral education and asked specifically about the utility of doctoral skills, behaviours, and competencies when translated into different workplaces. It presents some of the first insights into how doctoral value is perceived by graduates and the costs and benefits of doctoral study within and beyond the academy. Doctoral graduates (n = 22) identified four domains of doctoral value: (1) career value; (2) skills value; (3) social value; (4) personal value. These were influenced by factors experienced both during and after their degrees: (1) time since graduation; (2) supervision; (3) accrued social connectivity; (4) employer value of the doctorate. Our conceptual model of doctoral value contributes to international higher education knowledge by providing a structure for enhancing the doctoral experience and its benefits, both during study and for entering the job market.

Introduction

The movement of skilled individuals from the sites of knowledge production to knowledge application is vital to economic growth, and is the basis of the ‘Knowledge-Based Economy’. In the UK, graduates make positive social, cultural and economic contributions (Park, Citation2007), and universities, as sites of knowledge creation, play a key role in enabling such contributions. Transfer from university to business, of graduates with experience of producing novel and original research is central to that concept (Temple, Citation2012). Neumann and Tan (Citation2011) described doctoral students as the newest form of renewable energy in a world driven by knowledge-based economies. To facilitate the passage of the many doctoral graduates choosing to enter labour markets outside higher education (HE), and following multiple calls to reconsider doctoral development in broader employment contexts (Rip, Citation2004; Scott, Citation2006), doctoral programmes have been redesigned in many countries to include explicit development of broader workplace skills and experiences. Examples include access to development of management and teamwork skills (Benito & Romera, Citation2013) and increased attractiveness of doctoral graduates to non-HE employers (McGagh et al., Citation2016).

The recruitment of doctoral graduates yields collective knowledge, skills, networking, and prestige benefits to organisations making doctoral graduates assets of significant value to organisations (Diamond et al., Citation2014). In the European knowledge economy paradigm, doctorate holders are also understood to have a strategic role to play in achieving economic success (European University Association, Citation2008), and in building relationships between universities and businesses that enable knowledge sharing (Garcia-Quevedo, Mas-Verdú, & Polo-Otero, Citation2012). Doctoral graduates make a substantial contribution to UK industries, with around 56% of PhD holders leaving academia within six months of graduation (Mellors-Bourne, Metcalfe, & Pollard, Citation2013). Research graduates in Australia also go into a range of careers across business, academia, government, community and not-for-profit sectors, with almost 60% leaving academia within nine months of graduation (Guthrie & Bryant, Citation2015). Additionally, graduates are aware of the capital their knowledge-base affords them (Hancock & Walsh, Citation2016) and report positive impacts of their doctoral experience on their career progression and wider lives (Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2013).

We ask, how doctoral graduates as individuals conceptualise the value of holding a doctorate, and how their perceptions of different understandings of value can be leveraged to create doctoral programmes that maximise benefit to the individual candidate as well as ‘the greater good’? Our study was conducted in the UK, but we suggest that several of the factors and influences reported are relevant in other contexts internationally.

Concepts of value in doctoral education

The value of the doctorate is well explored in terms of describing the skills graduates develop. The comprehensive UK-sector document The researcher development framework (Vitae, Citation2011), delivered following the Roberts (Citation2002) report on UK STEM PhD graduate skills, lists 63 skills descriptors across four domains, and a similar framework of skills development for Australian Higher Degrees by Research is anticipated (McGagh et al., Citation2016). Commenting more broadly about professional identity and workplace behaviours, Hancock and Walsh (Citation2016) point out the limitations of ‘research career focused’ models of development, such as the Roberts (Citation2002) model, in the context of the changing nature of researcher careers. In answer to this known issue, researcher development professionals have utilised insight from graduates and from employers to supplement researcher ‘skills training’. Such value-added factors include, for example, developing cultural awareness, self-efficacy, leadership, and working relationships.

Postgraduates in HE may experience changing value perceptions affected by social and cultural factors, in addition to economic reward (Kalafatis & Ledden, Citation2013). Despite much media commentary on the subject, very little research explores the contextual factors of personal, social, and cultural value that individuals derive from the doctorate (Raddon & Sung, Citation2009), and the intellectual perspectives they develop (Boulos, Citation2016; Pitt, Citation2008). Ledden, Kalafatis, and Samouel (Citation2007) warned us that the influence of an individual’s personal values on the perceived value of engaging in education should not be overlooked, both in terms of educational content and also the structures, contexts, and relationships within which students operate. This study explored these aspects directly, and therefore, begins to fill such gaps in understanding.

Risk in doctoral education

The literature discussed in the previous section summarises the perceived individual benefits of doctoral study but does not balance the findings against the risks to the individual. That a doctoral degree does not offer a large financial incentive is well known (Casey, Citation2009). It can even, for some, represent a negative financial investment, a period ‘off the pay ladder’ in which study fees must be paid, undergraduate loans are not repaid, no pension contributions are made, and hidden costs such as ‘writing up fees’ compound financial stress. Post-PhD earning is not elevated much higher than that of Masters degree graduates, especially for women (Casey, Citation2009), and a share of doctorate holders take jobs unrelated to their degree or below their qualification level (Auriol, Citation2010). Being over-educated (doctorate not required for the role) and over-skilled (no opportunity to use doctoral skills) reduces job satisfaction dramatically (Paolo & Mañé, Citation2016), as well as threatening the doctorate holder’s financial situation. Doctoral students also experience many stressors relating to academic pressure and workload that are sustained over a period of years. Media attention and new research on occupational stress within university environments indicates that it is widespread among junior academics (Bozeman & Gaughan, Citation2011; Reevy & Deason, Citation2014), with as many as 32% of PhD students in a Belgian sample at risk of developing common psychiatric disorders (Levecque, Anseel, De Beuckelaer, Van der Heyden, & Gisle, Citation2017). Poor long-term academic career prospects, also impact deleteriously upon students’ sense of well-being (Walsh & Juniper, Citation2009), and dissatisfactory experiences of doctoral programmes negatively affects intentions to pursue a research career (Harman, Citation2002).

As recruitment to doctoral programmes continues to increase year-on-year in order to satisfy economic demand for highly skilled graduates, our study explored the value of a doctorate to the individual within the context of the challenges described above. We asked: (1) What value do doctoral graduates derive post-graduation from engaging with their doctoral studies and (2) How are their value judgements influenced?

Methodology

Participants and procedure

Doctoral graduates who were (a) working as postdocs at one institution, and (b) who were working in a variety of non-academic roles (members of an existing institutional ‘careers beyond the academy’ network), were recruited by email and through social media networks (run by the authors). Participants who graduated <15 years prior to the date of interview (chosen to improve accuracy of recall) and held a doctoral degree (any type) from a UK institution were eligible. Demographic information was supplied using a pre-interview questionnaire.

We used semi-structured interviews organised around open-ended questions about doctoral and postdoctoral experiences, to collect in-depth data. We used a constructivist approach to interviewing (Charmaz, Citation1995) as our priority was to draw out the experiences of the participant allowing them to use individual definitions of concepts (e.g., ‘value’ ‘benefit’ ‘risk’) with the aim of understanding how perceptions of value formed and changed. A topic guide was used and was based upon concepts of educational value from the literature, a preliminary ‘doctoral value survey’ sent to current doctoral students (not reported here), and piloting with two additional graduates.

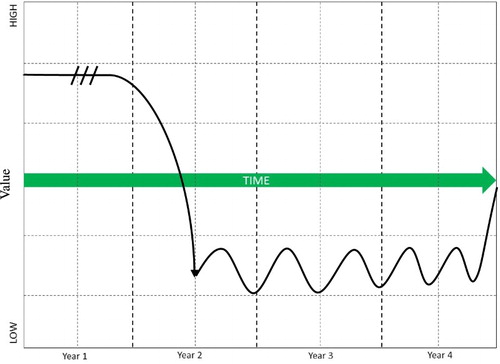

The following topics were explored in interviews: (1) experiences of the doctoral period; (2) skills, behaviours, and competencies for work; (3) philosophical perspectives and understanding of their doctorate; (4) value perceptions over time. Emerging themes identified by constant comparative analysis were explored in subsequent interviews. Recall of the participants’ positive and negative experiences during their doctoral degree was facilitated by using a graphic journey plot (see example in Appendix 1) exercise to stimulate discussion about the ‘high and low points’ over time. Data were collected using audio recordings, the mapping exercise, and researcher field notes.

Post-transcription, one-page summaries were created and sent with the full transcript to each participant. This member checking process allowed the participant to verify their account, providing credibility to our transcriptions and summaries of the data (Barnard, Lan, To, Paton, & Lai, Citation2009). Transcripts were then uploaded to NVivo (Version 12) in order to manage and make sense of the raw data.

Analysis

Our constructivist approach (Charmaz, Citation1995) prioritised a drawing out of participants’ lived experiences and personal definitions of doctoral value. A thematic framework was used to explore the interview data because of its iterative and systematic method of analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Data were inductively coded, allowing codes and themes to emerge and develop from the data, and subjecting codes to continuous refining and revision. Finally, sub-themes and themes were grouped and agreed. Peer debriefing within and outside the research team (e.g., with other colleagues, and at conferences) was used throughout the research to test emerging themes and embed credibility into the analytical process. The quotes provided in the results were deemed by us to be representative of the raw data, which we acknowledge is an interpretive process open to bias.

Results

Interviews (n = 22) occurred from May to September 2016 and lasted 51 minutes on average. Participant demographics are included in . Identifiers in the presented data are organised by gender, doctoral degree subject area, sector of current occupation, and years since graduation (y-s-g).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of doctoral graduates.

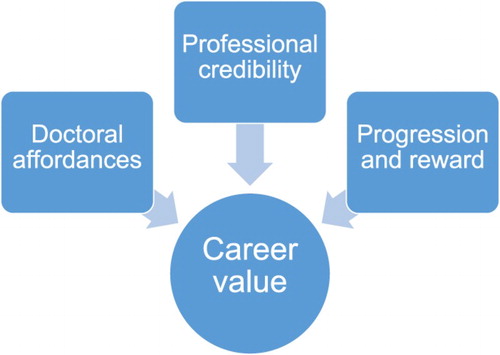

Doctoral graduates perceived that they had derived value from their studies that benefitted them after graduation. This was organised into the following core themes: (1) career value; (2) skills value; (3) social value; (4) personal value. These themes were consistent across the sample, although the way each graduate judged value was influenced by contextual and situational factors. We present these interpretations in relation to the core themes and these contextual ‘value-judgement’ factors. Finally, we present our conceptual model of doctoral value.

Career value

Career value was described in terms of the benefits/costs the doctorate had afforded graduates in their subsequent employment. It was organised into three sub-themes (). ‘Doctoral affordances’ refers to the intangible outcomes graduates attributed to their doctorate, for example, sector knowledge, networks, professional experience. In most cases, the doctorate was key in gaining employment after graduation, from simply giving a graduate ‘the edge’ in applications, to ensuring long-term career progression.

Male-STEM-Third sector 1 (4.5 y-s-g): I think it is valuable because I absolutely love my career now and it got me to where I am today. I don’t think I would have found my way otherwise.

This view was articulated regardless of the individual’s overall positive or negative feelings about their doctorate. Some questioned the career value of their doctorate in terms of its direct applicability within their current role, and some viewed the doctorate as comparable to periods of work experience, drawing from comparisons made to their current colleagues.

Male-STEM-Private sector 1 (1 y-s-g): If I had worked five years in a pharma company I think I would probably be at the same level as I would have been after a PhD. I think it is valuable but it’s probably as valuable as having five years’ experience.

Most graduates derived value from the credibility that their doctorates, and doctoral title, brought them in professional contexts. This credibility was described often as a way to attain professional credibility when meeting new colleagues or clients and made a positive impact early in those relationships.

Male-STEM-Third sector 1 (4.5 y-s-g): It’s very well respected. I interact with a lot of MPs, other doctors, professors, Lords. It’s quite useful to have a title in front of your name.

There was no consensus on whether their doctorates had already afforded them higher rates of promotion compared to non-doctoral colleagues; however, some articulated how they could access working opportunities that were not open to them before, allowing them to progress in their careers.

Male-STEM-Academic (research) 2 (2 y-s-g): I definitely think it’s improved my career from a practitioner perspective because it’s opened up opportunities; consultancy work that I may not have gotten previously.

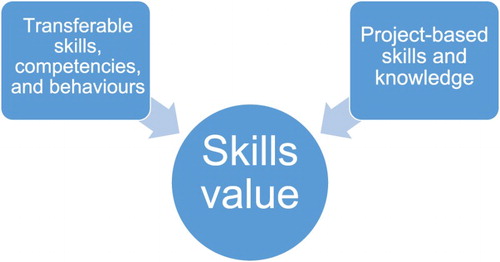

Skills value

All graduates identified significant skills value derived from their doctorate. These included technical skills – specific knowledge, laboratory techniques and report writing – though the most valuable were abstract cognitive skills, including critical thinking and argument construction (). Most importantly, they found that those skills, honed through the doctorate, were transferable into their graduate roles.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 3 (9 y-s-g): When I was filling in job applications I could provide examples of every skill that they wanted, because they would ask about problem solving, project management, organisation, and communication skills. And I realised that the PhD just covered all of this [and for graduate applications] I could draw on the PhD completely.

Significant skills value was derived from engaging with ‘extra-curricular’ activities (outside of their direct doctoral research project) that transferred readily into graduate roles. Typical examples included: work placements, part-time teaching, and public engagement activities.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 1 (10 y-s-g): I would almost put [public engagement activity] and other experiences, of more value than my PhD. I wouldn’t have been able to do them without my PhD because those doors wouldn’t have been open but actually they were the most valuable things.

Despite the valuable gains from their doctorate, many graduates identified common skills, behaviours, and competencies related to professional work outside of academia that they had not developed during their doctorate.

Female-A + H-Self-employed (14 y-s-g): The PhD just isolated me from every single person I knew so I don’t think it helped with management skills whatsoever.

There was also a clear need expressed for work placements, hosted in real working environments, that could help graduates prepare for different organisational cultures and contexts outside of the academy.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 1 (4 y-s-g): I don’t know if I felt that well prepared at all for work. I had done the obligatory courses that you do through your PhD. But I think I just didn’t have a broader understanding of that kind of work environment.

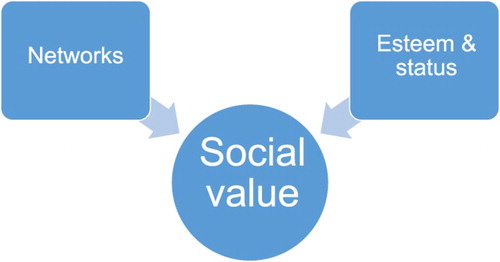

Social value

Most graduates described the close social bonds they had developed within their cohort of fellow students and colleagues, formed from the shared doctoral experience (). Social networks were strong throughout the doctorate and could endure years after graduation; for some this meant gaining valuable relationships.

Male-STEM-Academic (research) 1 (5 y-s-g): Because our PhD cohort was very tight. I married one of them and we are still good friends with our friendship group, the PhD cohort. We were all going through that together.

Integrating socially into their cohorts and departments was a prominent source of experienced value; however, in cases where social networks were not prevalent or less strong, graduates perceived that they derived low value, that they had ‘missed out’ compared to others.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 1 (4 y-s-g): We were in an office with three or four of us, but nobody spoke very often. Over the course of my PhD I started to go into the university less and less because there was no value of being in the room.

The doctorate offered some status/esteem value in social contexts to most graduates. However, its ‘real’ esteem value was questioned by many, especially in academic careers where doctorates are common. Some expressed hiding their doctoral title, either to appear humble, or to protect themselves.

Male-A + H-Public sector (7 y-s-g): There are some people where you see it in their signatures at work that they will call themselves doctor. That's something I’ve never considered and I think it would be almost detrimental to me, only because I think it would just make me feel a bit uncomfortable.

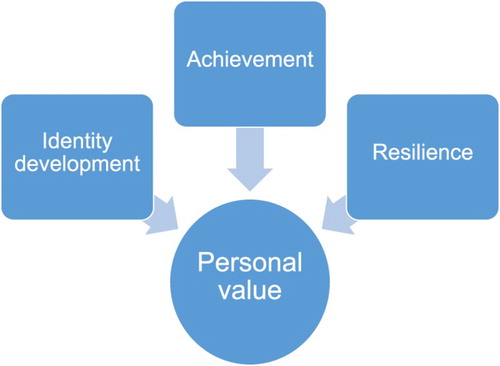

Personal value

It was a strongly held belief across all graduates that their doctoral experience had contributed significant personal value to their lives post-graduation (). They felt a strong sense of achievement and pride at attaining their doctorate and had developed resilience in the face of adversity, expressing the view that the doctorate had contributed positively to their perception of their own identity.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 1 (4 y-s-g): If you took the doctor off the front of my name I would feel half the person I currently feel, it’s massively important to me now. It’s become part of my identity.

Although for those who reported an overall negative doctoral experience, the value contribution of the experience to their identity was lesser or insignificant.

Female-STEM-Academic (research) 1 (1.5 y-s-g): I think I haven’t integrated the PhD into my personality at all, I don’t call myself doctor outside of work.

Universally, graduates were proud of earning their doctorates, even if this was expressed as ‘despite’ negative experiences. Many articulated their pride using wartime language and as a process they ‘suffered through’, ‘struggled with’, or that was a case of ‘survival’; conceptualising their doctorate as a hard won ‘badge of honour’.

Male-STEM-Academic (research) 1 (5 y-s-g): I’ve battled for my PhD.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 1 (4 y-s-g): You try and survive it, you survive a PhD, that’s what you do.

All graduates to some extent felt that their confidence had been broken down by the challenges of and relationships experienced within the doctorate. But, by ‘getting through’ the process with a successful outcome they found that they had gained valuable future strategies for resilience.

Male-STEM-Private sector 1 (1 y-s-g): I think it’s just made me a much stronger person mentally, […] it’s an experience isn’t it, you really go through something that not a lot of people go through, it’s so intense. […] You feel like you can deal with a lot of stuff after that.

Factors impacting upon value judgements

The derived value from the doctorate was weighted and utilised in different ways and constrained by different contexts for different individuals. Participants identified four main influencing factors in making value judgements: (1) time since graduation; (2) supervision; (3) accrued social connectivity; (4) employer value of the doctorate.

Time since graduation

In almost all cases, graduates’ perceptions of doctoral value fluctuated but increased over time from the point of graduation. This was articulated by some as being because they had more time to reflect and realise latent aspects of value that were not obvious to them at graduation.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 3 (9 y-s-g): I think I value it more. It took a period of reflection to realise the benefit of it, I think I value it more now than I did when was doing it.

Some graduates found the time-value factor was a function of the career opportunities open to them over time rather than an intrinsic/reflective value increase. In one case, there was a perceived decline in value over time.

Male-STEM-Private sector 2 (7.5 y-s-g): I think it’s gone down a little bit, because the other skills that I’ve had to learn […] which I think were missing from my PhD.

Supervisory relationships

Graduates’ value perceptions were most significantly influenced by supervisory relationships. Around half of graduates interviewed reported that they had experienced positive supervisory relationships which endured after graduation, and added social value, enhancing their professional networks.

Female-STEM-Public sector (1.5 y-s-g): I find the whole PhD relationship valuable, for getting life skills in general, and I’m still in touch with all the supervisors, the professor PhD supervisor wrote me a job reference after.

In the other half of cases, these relationships were described as more transactional, low quality, or of negative value. Similarly, these endured as lasting negative experiences which coloured the doctoral experience and beyond.

Male-STEM-Public sector (9 y-s-g): It wasn’t particularly productive and looking back there were these massive issues, but of course at the time I wasn’t aware of them.

Social connectivity

Graduates reported their reliance on other doctoral students and postdoctoral research staff for support during the doctoral process; formally as a cohort, and informally through departmental structures, shared offices, and socialisation. Many attributed succeeding with their doctorate to their peer group and valued peer support and socialisation above other factors. Peer group and postdoctoral support was described as being able to attenuate some of the negative effects of low quality supervision or poor supervision relationships.

Female-A + H-academic (professional services) (3 y-s-g): I certainly feel like the peer network was more valuable, and I got more in terms of academic support for my PhD from my peers than I got from (supervisor).

Feeling valued at work

When asked whether having a doctorate impacted upon their employer’s perceptions of their contribution, that is, ‘Is having this higher qualification valued by your employers?’, some graduates felt that it was not considered particularly valuable, and that it did not stop them ‘feeling like a commodity’ in their organisation.

Male-SocSci-Public sector (1 y-s-g): I don’t imagine for a second that anyone any senior to me would see that (their doctorate) as bringing value to the role I do.

However, most graduates felt their employers valued their doctoral-level skills and attributes, and often compared themselves to their non-doctoral colleagues.

Female-STEM-Academic (professional services) 3 (9 y-s-g): I think my colleagues had to build those professional skills whereas I already had those […] that was valued by the people above me.

Conceptual model of doctoral value and mapping

The four core themes of doctoral value, and the four influences on value judgements, were consistent across all participants’ accounts of their doctoral and graduate experiences. Our conceptual model of doctoral value () was developed from these findings and provides a frame of reference for discussions of value, and value added in the design and quality assurance of doctoral programmes.

Discussion

Our conceptual model illustrates how domains of value were positioned within a context of influencing factors: time since graduation, supervisory relationships, accrued social connectivity, and feeling valued at work. These domains and influencing factors were identified by all participants, from both positive and negative overall perspectives, reflecting the diversity of their experiences but also the enduring nature of the themes.

Research question 1 – domains of doctoral value

The doctorate was seen as an important factor in gaining employment, and in most cases, had contributed positively towards success in employment. However, for some the doctorate can be perceived as only equal to a period of professional experience. Most graduates felt that they could expect better salaries and career progression from completing their doctorates, and monetary and career advancement were factors in how career value was derived. Comparisons of these economic benefits to undergraduate or masters degrees are well-documented in the literature, primarily in demonstrating value for money from the doctorate (Conlon & Patrignani, Citation2011; Diamond et al., Citation2014). In this case, career value was used by individuals as a measure of the overall value of their doctorates. It was not possible from our data to define career aspirations ‘pre-doctorate’ for most participants. On embarking, most saw a doctorate as the ‘next logical step’ to continue their academic interests and had no defined career aspirations, meaning that we were not able to interpret our data in line with matched/mismatched career expectations.

Graduates identified many transferable skills gained from their doctoral experience, independent of discipline. It is well-known that doctoral graduates develop transferable skills (Nerad & Cerny, Citation2000), although previous accounts have focused more on direct gains (knowledge and techniques specific to doctoral research) (Diamond et al., Citation2014) than our examples (communication, critical thinking, strategies for resilience). Graduates in academic roles reported that the direct skills and knowledge gained were of utility more often than those in roles outside academia, also observed by Tzanakou (Citation2012). Graduates described the value added to their doctoral experiences through accessing ‘extra-curricular’ opportunities and experiences (e.g., public engagement, work placements). These experiences filled gaps in their development and were of significant importance post-graduation, suggesting that ‘standard’ doctoral degree programmes alone may not adequately prepare graduates for work. This is a useful finding for educational designers, and more holistic guides to the doctoral experience are beginning to encourage extracurricular involvement (Bryan & Church, Citation2017).

Graduates accrued socially derived benefits from their relationships with supervisors, the academic community, and their peers. Tzanakou (Citation2012) argued that the doctorate and awarding institution can confer a form of cultural and social capital, which can be converted into increased prospects or earnings dependent upon institutional prestige. Accounts of this were expressed in our study also; doctoral prestige was frequently described as ‘respect’ or ‘credibility’, although institutional prestige was not apparent in our data.

The doctorate’s contribution in shaping an individual’s sense of identity is not a new concept in doctoral education research. McAlpine and Amundsen (Citation2011, p. 178) discuss how individuals’ previous learning experiences affect their present and future ‘identity-trajectories’, influencing sense-of-self within the doctorate, and beyond. Personal resilience has been identified as essential in adapting to, and succeeding in the academic ‘rejection environment’ where judgement from others can be detrimental to academic professional development (McAlpine & Amundsen, Citation2011, p. 180). Significantly, we identified that resilience was cultivated in response to doctoral adversity. Several participants described their doctorates as a ‘badge of honour’ which they had ‘battled’ to earn, implying suffering for a higher goal. This is similar to the views of Kalafatis and Ledden (Citation2013, p. 1544) who described educational value as interwoven ‘benefits and sacrifices’ with benefits (functionality, prestige, and pride) arising from within experiences of ‘monetary and psychological sacrifices’.

Research question 2 – factors influencing doctoral value

Value perceptions changed over time as graduates progressed through their careers and away from the point of graduation. In almost all cases, these perceptions became more positive as the applicability of the skills gained, and status afforded by the doctorate, became more apparent. Changes in perceptions of educational value in undergraduate study have been identified (Kalafatis & Ledden, Citation2013), but our results are the first to suggest an increase in perceived doctoral value over time.

Supervision was the major influence on perceptions of doctoral value. In line with other research, participants cited issues with supervisory support and relationship quality as causal in creating negative doctoral experiences (Moxham, Dwyer, & Reid-Searl, Citation2013). Those describing positive supervision relationships also cited supervisors as key proponents of their development, compared to those who reported poor relationships. The supervisory relationship is of key importance in the doctoral experience (Zhao, Golde, & McCormick, Citation2007) and a number of sources highlight the relationship as being pivotal to successful completion (McCallin & Nayar, Citation2012; Zhao et al., Citation2007). Some graduates perceived value from the recommendations, connections, and support they had received from supervisors post-graduation, in line with Tzanakou (Citation2012) who reported similar benefits postdoctoral graduation.

Value perceptions were influenced by the social capital (contacts, networks, connectedness) graduates accrued within their doctorate, transferring into postdoctorate life. Much of this manifested from the support they received from different people, including: supervisors, peers, the department, and family. This finding reflects recent reports of a wide social context for doctoral learning (McAlpine & McKinnon, Citation2013; Wisker, Robinson, & Bengtsen, Citation2017). McAlpine and Amundsen (Citation2012) similarly found that students accessed support from many different sources and valued these equally to their supervisor. Social capital was derived from the educational prestige of the degree, although prestige did vary across disciplines and occupations (Triventi, Citation2013).

Most graduates were aware of how their employers viewed their doctorate. They described being viewed as individuals with ‘advanced knowledge and skills’ which were not as well developed in colleagues without doctorates. A similar finding was reported by Diamond et al. (Citation2014): employers cited doctoral graduates as able to offer advanced research skills as well as useful critical perspectives. Doctorate holders may influence what has been termed a ‘spill-over effect’ in organisations, helping to increase workplace productivity through shared knowledge, and enhancing reputation (Tzanakou, Citation2012). Negative value perceptions in this study were derived from feeling under-used or unable to apply the skills gained in their doctorates, which can decrease job satisfaction (Paolo & Mañé, Citation2016). Some participants described feeling like commodities, reflecting a broader view that doctorate holders are resource units in the new knowledge economy (Auriol, Citation2010).

There are some key limitations of this study that should be acknowledged and built upon in further research. As this study was exploratory in nature, we did not seek a large sample to collect generalisable responses on doctoral value. Although we believe the concepts of value presented are relevant across doctoral contexts, we acknowledge that the context in which our study occurred and its results are not globally representative. For example, there are different modes of study and candidacy across the world (professional doctorates; longer North American degrees, thesis by publication; candidate employment status) which adds variety. We did not collect participants’ age when they commenced the doctorate. With increased age we could expect to see larger professional networks, along with greater familiarity with workplace cultures and protocols, and the influence of increased age warrants require further detailed exploration. Finally, our approach to this study was framed around ‘value’ and ‘post-graduate employment’ and may have influenced the way our participants responded, promoting an economic view of the purpose of education.

This study builds upon the preliminary findings of others in regards to career and skills value (Diamond et al., Citation2014; Tzanakou, Citation2012), but also rigorously explores the previously unclear views of social value and personal value post-graduation (Raddon & Sung, Citation2009). It provides insight into how doctoral value is judged at the level of the individual, and points to supervision and other support networks as being of significant importance during and also after study. This informs the next stage in our research programme which, taking inspiration from Australian PhD alumni survey research (Marsh, Rowe, & Martin, Citation2002), uses survey methods to test the strength of our conceptual model using a higher sample. We will be able then to sift on potentially differentiating characteristics such as time since graduation, demographic, and labour markets.

Our findings chime with a key finding from a sector level report by Mellors-Bourne et al. (Citation2013) in that our participants were mostly satisfied with their early career progress and felt that they had been well prepared by their doctoral degree. Our work directly expands on these findings, contributing a deeper qualitative view using the lens of value, and identifies specific enablers and barriers to realising that value. A recent national report on Australia’s Higher Degree by Research training systems (McGagh et al., Citation2016) reported that making an informed choice about engagement in doctoral research was one of three priority areas for change to ensure that researchers are capable of succeeding with the doctorate and in a range of post-graduation careers. Our research (albeit from a small sample) contributes to our endorsement of this priority, particularly in determining how a prospective candidate may interpret, frame and maximise the value they gain from their experience.

The wider marketisation of the global HE sector distorts the individual’s perspective of value, reducing it to the more transactional view of ‘economic value’ apparent in undergraduate education, and which appears to be progressing to postgraduate level analyses (Kalafatis & Ledden, Citation2013). For example, UK policies on doctoral education, such as doctoral loans available in the 2018–2019 academic year (DofE, Citation2017), emphasise the value of doctoral graduates to the employer and economy, over that of the individual and society. If those who hold a doctorate are essential in the creation of knowledge-based economic growth (Neumann & Tan, Citation2011), then as a sector we need to think carefully about ‘what’s in it for them’, aiming to understand what enables an individual to declare that their PhD was worth the time, emotional effort, and financial investment.

Conclusion

We present our conceptual model of doctoral value to provide a structure that will help to enhance the doctoral experience, doctorate value, and preparedness for a range of employment contexts. Institutions could use this model for re-framing the doctoral experience, and to inform the design of development programmes. Raising early awareness of potential career paths (Mangematin, Citation2000) and enabling researchers to access the diverse systems of support and institutional resource (McAlpine & Turner, Citation2012) is paramount in encouraging engagement with value-added opportunities. Personalised development that aligns with individual career trajectories (rather than a set of ‘employability skills’) can help to mesh the needs of society and employers with individual satisfaction (Halse & Mowbray, Citation2011). This model may contribute to improved awareness of the value of employing doctoral graduates, and better partnerships with employers. The diverse benefits that doctoral graduates can bring to job roles must also be understood from both the employer and graduate perspective, so that supply of and demand for doctoral graduates is matched and mutually rewarding.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for their contributions and cooperation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Billy Bryan http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5771-2354

Kay Guccione http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9910-9388

References

- Auriol, L. (2010). Careers of doctorate holders. Employment and mobility patterns (p. 29). OECD library.

- Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S.-L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005

- Benito, M., & Romera, R. (2013). How to boost the PHD labour market? Facts from the PHD system side (Working paper). Retrieved from http://e-archivo.uc3m.es/bitstream/handle/10016/17545/ws132824.pdf?sequence=1

- Boulos, A. (2016). The labour market relevance of PhDs: An issue for academic research and policy-makers. Studies in Higher Education, 41(5), 901–913. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1147719

- Bozeman, B., & Gaughan, M. (2011). Job satisfaction among university faculty: Individual, work, and institutional determinants. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(2), 154–186. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2011.0011

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryan, B., & Church, H. R. (2017). Twelve tips for choosing and surviving a PhD in medical education – A student perspective. Medical Teacher, 39(11), 1123–1127. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1322192

- Casey, B. H. (2009). The economic contribution of PhDs. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 31(3), 219–227. doi: 10.1080/13600800902974294

- Charmaz, K. (1995). Between positivism and postmodernism: Implications for methods. Studies in Symbolic Interaction, 17(2), 43–72.

- Conlon, G., & Patrignani, P. (2011). The returns to higher education qualifications. London: Department of Business, Innovation and Skills.

- Diamond, A., Ball, C., Vorley, T., Hughes, T., Moreton, R., Howe, P., & Nathwani, T. (2014). The impact of doctoral careers. Leicester: CFE Research.

- DofE. (2017). Postgraduate doctoral loans: Government consultation response. London: Higher Education Administration. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/597333/Doctoral_response_to_consultation.pdf

- European University Association. (2008). Universities outline future priorities for improving the quality of doctoral education in Europe. Launch Conference for the European University Association Council for Doctoral Education, University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

- Garcia-Quevedo, J., Mas-Verdú, F., & Polo-Otero, J. (2012). Which firms want PhDs? An analysis of the determinants of the demand. Higher Education, 63(5), 607–620. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9461-8

- Guthrie, B., & Bryant, G. (2015). Postgraduate destinations 2014: A report on the work and study outcomes of recent higher education postgraduates. Melbourne: Graduate Careers Australia.

- Halse, C., & Mowbray, S. (2011). The impact of the doctorate. Studies in Higher Education, 36, 513–525. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.594590

- Hancock, S., & Walsh, E. (2016). Beyond knowledge and skills: Rethinking the development of professional identity during the STEM doctorate. Studies in Higher Education, 41(1), 37–50. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.915301

- Harman, G. (2002). Producing PhD graduates in Australia for the knowledge economy. Higher Education Research & Development, 21(2), 179–190. doi: 10.1080/07294360220144097

- Kalafatis, S., & Ledden, L. (2013). Carry-over effects in perceptions of educational value. Studies in Higher Education, 38(10), 1540–1561. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.643862

- Ledden, L., Kalafatis, S. P., & Samouel, P. (2007). The relationship between personal values and perceived value of education. Journal of Business Research, 60(9), 965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.021

- Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J., & Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868–879. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.008

- Mangematin, V. (2000). Phd job market: Professional trajectories and incentives during the PhD. Research Policy, 29(6), 741–756. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00047-5

- Marsh, H. W., Rowe, K. J., & Martin, A. (2002). Phd students’ evaluations of research supervision: Issues, complexities, and challenges in a nationwide Australian experiment in benchmarking universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(3), 313–348.

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2011). Making meaning of diverse experiences: Constructing an identity through time. In L. McAlpine, & C. Amundsen (Eds.), Doctoral education: Research-based strategies for doctoral students, supervisors and administrators (pp. 173–183). Dordrecht: Springer.

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2012). Challenging the taken-for-granted: How research analysis might inform pedagogical practices and institutional policies related to doctoral education. Studies in Higher Education, 37(6), 683–694. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2010.537747

- McAlpine, L., & McKinnon, M. (2013). Supervision – The most variable of variables: Student perspectives. Studies in Continuing Education, 35(3), 265–280. doi: 10.1080/0158037X.2012.746227

- McAlpine, L., & Turner, G. (2012). Imagined and emerging career patterns: Perceptions of doctoral students and research staff. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 36(4), 535–548. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2011.643777

- McCallin, A., & Nayar, S. (2012). Postgraduate research supervision: A critical review of current practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 17(1), 63–74. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.590979

- McGagh, J., Marsh, H., Western, M., Thomas, P., Hastings, A., Mihailova, M., & Wenham, M. (2016). Review of Australia’s research training system. Melbourne: Australian Council of Learned Academies.

- Mellors-Bourne, R., Metcalfe, J., & Pollard, P. (2013). What do researchers do? Early career progression of doctoral graduates. Cambridge: Vitae.

- Moxham, L., Dwyer, T., & Reid-Searl, K. (2013). Articulating expectations for PhD candidature upon commencement: Ensuring supervisor/student ‘best fit’. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(4), 345–354. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2013.812030

- Nerad, M., & Cerny, J. (2000). From rumors to facts: Career outcomes of English PhDs. ADE Bulletin, 43–55. doi: 10.1632/ade.124.43

- Neumann, R., & Tan, K. K. (2011). From PhD to initial employment: The doctorate in a knowledge economy. Studies in Higher Education, 36(5), 601–614. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.594596

- Paolo, A. D., & Mañé, F. (2016). Misusing our talent? Overeducation, overskilling and skill underutilisation among Spanish PhD graduates. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 27(4), 432–452. doi: 10.1177/1035304616657479

- Park, C. (2007). Redefining the doctorate. York: Higher Education Authority.

- Pitt, R. (2008). The PhD in the global knowledge economy: Hypothesising beyond employability. In M. Kiley & G. Mullins (Eds.), Quality in postgraduate research: Research education in the new global environment (pp. 55–64). Canberra: CEDAM ANU.

- Raddon, A., & Sung, J. (2009). The career choices and impact of PhD graduates in the UK: A synthesis review. Science in Society Programme.

- Reevy, G. M., & Deason, G. (2014). Predictors of depression, stress, and anxiety among non-tenure track faculty. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00701

- Rip, A. (2004). Strategic research, post-modern universities and research training. Higher Education Policy, 17(2), 153–166. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300048

- Roberts, G. (2002). Set for success: The supply of people with science, technology, engineering and mathematics skills. London: HM Treasury.

- Scott, P. (2006). The academic profession in a knowledge society. Wenner Gren International Series, 83, 19.

- Temple, P. (2012). Universities in the knowledge economy: Higher education organisation and global change. London: Routledge.

- Triventi, M. (2013). Stratification in higher education and its relationship with social inequality: A comparative study of 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 489–502. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr092

- Tzanakou, C. (2012). Beyond the PhD: The significance of boundaries in the early careers of highly qualified Greek scientists and engineers (Doctoral dissertation). University of Warwick.

- Vitae. (2011). The researcher development framework. Retrieved from https://www.vitae.ac.uk/vitae-publications/rdf-related/researcher-development-framework-rdf-vitae.pdf

- Walsh, E., & Juniper, B. (2009). Development of an innovative well-being assessment for postgraduate researchers and its use to drive change. Paper presented at the Vitae Researcher Development Conference, University of Warwick. Retrieved from http://www.vitae.ac.uk/policy-practice/916-86363/Workshops/119881/Vitae-researcher-development-conference-2009-realising-the-potential-of-%20researchers-.html

- Wisker, G., Robinson, G., & Bengtsen, S. S. (2017). Penumbra: Doctoral support as drama: From the ‘lightside’ to the ‘darkside’. From front of house to trapdoors and recesses. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(6), 527–538. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2017.1371057

- Zhao, C. M., Golde, C. M., & McCormick, A. C. (2007). More than a signature: How advisor choice and advisor behaviour affect doctoral student satisfaction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31(3), 263–281. doi: 10.1080/03098770701424983