ABSTRACT

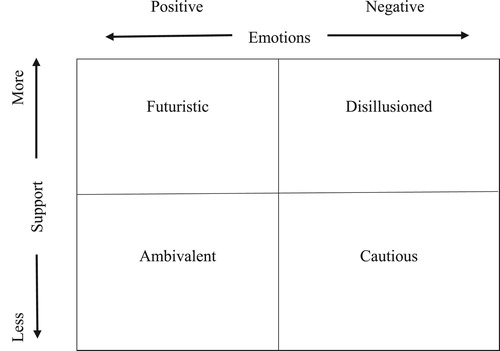

Higher education (HE) has seen a growing trend towards online study. However, teaching is deeply connected to one’s beliefs, values, commitments and to relationships with students. A change in the mode of instruction and pedagogy has the potential to disrupt these deep and personal connections giving rise to an emotional response. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore the nature and significance of emotions in HE educators transitioning to online teaching. Findings indicate a dynamic relationship between the type of emotional responses and the amount of institutional support. Based on the type of emotional response and amount of support, four emergent orientations of educators are presented: Futuristic, Ambivalent, Disillusioned and Cautious. Implications for practice are also presented.

Introduction

Teaching by its very nature is a complex social, personal and cognitive process that relies on effective communication and relationships between educators and students, and as such it is an emotional experience for both (Day, Citation2008; Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014; Jephcote & Salisbury, Citation2009; Schutz et al., Citation2006). More specifically, emotions are known to influence educators’ well-being, job satisfaction, burnout risk and retention, and their emotional bonds with students influence their decisions about teaching strategies, curriculum selection and lesson planning (Bennett, Citation2014; Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). Adding to this is the growing and well-documented trend towards online study in HE (Gazza, Citation2017; Han et al., Citation2019; Howe et al., Citation2018; Ouyang & Scharber, Citation2017). Indeed, the recent impact of COVID-19 has propelled the HE sectors into obligatory online delivery overnight. This has posed significant challenges for HE educators as they race to learn new technologies and apply a different type of pedagogy.

Past research concerned with online teaching has focused on students’ experiences (Brown, Citation2016); implementation of technology (Gazza, Citation2017: Han et al., Citation2019; Howe et al., Citation2018); and the facilitation of online learning communities (Ouyang & Scharber, Citation2017). However, less is known about the impact of teaching online for HE educators and even less is known about HE educators’ emotional responses to online teaching. McIntosh’s (Citation2010) study into the affective nexus of e-teaching and e-workplaces concluded that neither ‘great feelings’ nor ‘great work’ are experienced consistently by the HE sector and that there needs to be increased attention to HE educators’ emotions and its impact on online teaching.

This study sought to explore the nature, extent and significance of emotions experienced by HE educators as they transition to online learning environments (OLE). In our investigation, we applied Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which is an established idiographic, inductive methodology connected to hermeneutics and theories of interpretation (Smith et al., Citation2009). The major objective of IPA is to interrogate how people make sense of life experiences. The methodology combines the investigation of unique experiences with the interpretation of these experiences from the participant’s perspective, thus presenting an opportunity for researchers to create new meaning about a phenomenon (Smith & Osborn, Citation2003). We therefore judged IPA as a useful approach to exploring the interplay of educator emotions when going online. The outcomes of this study will further understandings about the impact of emotions on teaching in the HE online environment and facilitate the development of policies and practices that support the implementation process and experiences for HE educators.

Literature review

Literature recognises emotions as a significant factor that contributes to the teaching experience and impacts educators’ beliefs, judgements and motivation (Chen, Citation2018; Schutz et al., Citation2006). However, empirical research on the emotional perspectives of teaching in higher education continues to be scarce. To inform our study, we looked at relevant research into the nature, extent and significance of emotions in HE educators and the associated impact on transitioning to online teaching.

The nature of emotions

Schutz et al.’s (Citation2006) research into emotions in educational settings defines emotions as:

Socially constructed, personally enacted ways of being that emerge from conscious and/or unconscious judgements regarding perceived success at attaining goals or maintaining standards or beliefs during transactions as part of social-historical contexts. (p. 344).

Extent and significance of emotions in HE educators teaching online

The extent and significance of emotions refers to the degree to which emotions are identified and described by HE educators. The few studies that reported findings about HE educators’ emotions in OLE found they ranged from positive to negative (Bennett, Citation2014; Downing & Dyment, Citation2013; Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014; McIntosh, Citation2010). Positive emotions reported by HE educators included feeling energised and motivated to try out new technologies and ways of engaging with students, and being committed to improving students’ outcomes (Bennett, Citation2014). Other positive emotions emerged from intrinsic factors, such as successful students’ learning (passion, enthusiasm), students’ engagement and achievements or lack of (delight, frustration), ability to build positive relationships (satisfaction, surprise, pride), and when educators realised teaching was only partially controllable (hope, excitement, relief) (Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014).

However, Bennett’s (Citation2014) study found the majority of HE educators reported negative emotions to online teaching with three broad themes emerging. Firstly, negativity ranged from being anxious and apprehensive to stronger emotions such as fear of exposure (inadequate knowledge). Educators experienced embarrassment when institutional systems failed, and frustration, infuriation, fear of catastrophe and despair when the technology impacted on students’ assessments. Relations with colleagues elicited emotions ranging from humiliation and being laughed at, to feeling despondent and not wanting to persevere with online teaching. This implies that emotions have the potential to influence the degree to which HE educators are willing to engage in and embrace OLE. HE educators were positive and confident with their knowledge of pedagogy and content as a result of years of face-to-face teaching. However, the integration of technology and pedagogy present a different and significant role change. Because technology is progressive and tends to place educators in a position of perpetual novice, developing competency in OLE can be a moving target (Brinkley-Etzkorn, Citation2018; Kilgour et al., Citation2019). The emotional perspectives involved in learning new ways to teach presents potential challenges that require acknowledgement.

The impact of emotions to teaching online

Whilst the small number of studies investigating the impact of HE educators’ emotions to teaching online found that emotions influenced their actions, motives, reasoning and decision-making, these studies have presented mixed results. Positive emotions were associated with enhanced self-perception of well-being and engagement in teaching. Bennett (Citation2014) found educators also used strategies for managing their emotions, such as being highly prepared by knowing the content and being skilled in both the technology and pedagogy. Gilmore and Warren (Citation2007) concluded that emotions had the potential to engage students and tutors in more creative, complex and critical thinking, and therefore was a more productive arena for learning and a rewarding experience for HE educators.

In contrast, Downing and Dyment (Citation2013) found HE educators who were highly skilled and confident in face-to-face teaching became abruptly deskilled when transitioning to OLE. Negative emotions were associated with disempowerment, isolation, vulnerability, shame and frustration. HE educators found themselves technologically challenged by their lack of familiarity with software and system programmes. They faced pedagogical challenges to construct effective learning outcomes and experiences that ensured students’ participation and engagement, and in providing effective assessment and feedback online. The negative emotions impacted on educators’ self-identity, self-efficacy, participation in courses, choice of strategies and in their interactions with students and other co-workers.

The impact of emotions, either positive or negative, has the potential to constrain or facilitate the transition to OLE. Heath and Heath (Citation2010) emphasise that change is not simply a technical process but rather it requires significant emotional energy and, without emotional engagement, changes will not be sustained. Rogers' (Citation2003) diffusion of innovation theory (DOI) also serves to describe the emotional states of mind when faced with accepting and adapting to innovations such as OLE. Firstly, participants must see the change as having a relative advantage or being an improvement on previous ways of doing. Secondly, the change must be compatible with previously held beliefs and values. Thirdly, the innovation should be comparatively easy to implement. Fourthly, participants must be able to trial the innovation. Finally, participants must have opportunities to observe the innovation in successful situations by successful mentors. These states of mind are likely to influence HE educators’ implementation of OLE.

Institutional support for online teaching

The institutional support for HE educators as they transitioned to online learning is critical during the change process. Martin et al. (Citation2019) reviewed award-winning online institutions and noted conditions that were in play. They concluded that successful online institutions have online educators centre stage in the roles of designer, assessor and facilitator. This implies the need for HE educators to have ownership of the pedagogy, technology and the content in courses they develop. In addition, Howe et al. (Citation2018) reported institutional satisfaction was significantly higher for educators who received mentoring, release time, technical support and training for software and hardware, than those that did not. Downing and Dyment (Citation2013) found individualised ‘at the elbow’ technology support was most valued, followed by self-directed professional development and least useful was formal institution-wide workshops. The popularity of ‘at the elbow’ support was the result of a culture of trust and reciprocity with the online team in order to abate fear, vulnerability and uncertainty with online technology. Individualised technology support posits the importance of recognising the interrelationship between professional identity, knowledge and action.

This review serves to highlight the limited research on emotions involved in HE online teaching. Given the impact of emotions to educator pedagogic practices and professional development, research into how emotions play out in the HE online environment is critical. The purpose of this study was to investigate the emotions of HE educators as they transitioned to online teaching. Our study was guided by three research questions:

Q1. How do HE educators describe their initial emotional response to online teaching?

Q2. What emotional responses do HE educators experience during the transition to online teaching?

Q3. What institutional support is offered to HE educators as they transition to online teaching?

Methodology

We approached our study using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to examine the emotional perspectives of transitioning to online teaching. A major strength of IPA is its ability to expose unique patterns drawn from participant accounts (Smith et al., Citation2009). The method acknowledges the reflexive role of researchers in the interpretation of the data by going through a double hermeneutic process (Smith & Osborn, Citation2003). As the participants communicate how they make sense of their experiences, the researcher interprets what participant experiences mean. This reflexive action provides researchers with opportunity to uncover new theoretical perspectives. These fundamental features of IPA found congruence with our research aim of gaining insight into the emotional perspectives of going online.

Participants

Following the receipt of ethics approval for the study, we purposively selected 20 educators involved in online teaching from cross-discipline areas in one Australian university. They included five (5) discipline areas of Business, Liberal Arts, Nursing, Social work, and Teaching. All consented to participate and were invited to individual interviews. There were 12 females and 8 males with ages ranging from 30 to 69 years. Their online teaching experiences ranged from 3 to 21 years. The educators had a range of experiences with online teaching from course development and design to teaching and course evaluation. Each participant was assigned a code to protect confidentiality.

Procedures

The participants were interviewed for approximately 1 h. The interview schedule used open-ended questions that allowed for rich and detailed accounts of educator’s experiences and emotional responses to teaching online. Examples of questions were ‘Tell me about your initial emotional response to online teaching’, ‘Tell me about the emotions you felt whilst you transitioned to online teaching’, and ‘Tell me how you feel about the support provided for online teaching’. At the end of each interview, participants were invited to add any additional comments to ensure their experience had been sufficiently covered. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The interactive analytical process proceeded in accordance with established guidelines (Smith et al., Citation2009). In IPA methodology with multiple participants, it is recommended that researchers look at one participant in detail before moving on to the subsequent cases. Thus, we looked independently at the first transcript to identify categories. For each research question we annotated the script for the emotions being explicitly or implicitly described. Secondly, we inferred the causes of these emotions. The next stage of data reduction was to connect the categories and look for themes and sub-themes. After establishing the initial themes, we met to confirm and validate our interpretations. From this analysis of the first script, the subsequent scripts were analysed following the same procedure.

Finally, a list of master themes was generated, and minor themes, either not supported by most of the participants, and/or not highly significant for any one participant, were removed. This iterative process culminated in a collection of related themes under each master theme, and corresponding illustrative statements of the meaning and essence of the participants’ lived experiences.

To enhance the quality of the study, we applied the criteria for validity of qualitative studies as proposed by Yardley (Citation2000). Sensitivity to context was ensured by the co-researchers remaining grounded in the data at each stage of analysis. Commitment and rigour were established by adhering to the recommended IPA systematic method (Smith et al., Citation2009) and employing thoroughness in the analytical process. Transparency and coherence were applied by providing a clear description of how themes were constructed and included illustrative extracts of the data. Impact and importance were encouraged by presenting findings that contribute to new perspectives of teaching online, thus adding to existing theory.

In terms of limitations, the sample size of 20 could be perceived as conservative. The sample size, however, is appropriate for the methodology applied. The study produced an enormous amount of rich data with repeating themes emerging during data analysis, demonstrating that saturation had been reached. Another limitation is the involvement of the researchers as they interact with the data. Particularly within this study’s context, participants were known to researchers on both a social and professional level. And the researchers’ interpretative framework was certainly influenced by personal experiences of teaching online. This means that findings may not be identically replicated. However, familiarity with participants and subject content intuitively facilitated rapport and effective analysis of the data. Beyond generalisability, IPA provided us the opportunity to use participants’ lived experiences to offer insights into the phenomena of emotions in the process of transitioning to OLE.

Findings and discussion

Initial responses to teaching online revealed the full spectrum of emotions from positive to negative in the transition to OLE. This finding was consistent with existing literature (Bennett, Citation2014; Downing & Dyment, Citation2013; Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014; McIntosh, Citation2010). Going online challenged all educators to interrogate how they could combine technology and new ways of teaching. Aligned with Rogers’ (Citation2003) diffusion of innovation theory, the educators displayed different rates of adoption depending on their attitudes and beliefs. As we engaged with the data, major themes of ‘being a pioneer’, ‘the changing landscape of teaching’ and ‘sense of a journey’ were revealed. ‘Being a pioneer’ was expressed through feelings of experiencing unprecedented challenges of combining pedagogical and technological learning under immense pressure. The ‘changing landscape of teaching’ was reflected in the educators’ realisation of the necessity to integrate technology with pedagogy and managing the challenges that arose. The ‘sense of a journey’ was attached to the rapidity of the change process because the transition to online teaching happened relatively quickly and the technology was new and evolving. One participant summed up these experiences:

We’re pioneers, and at the moment we’re bearing the brunt of wasted time as we run around to meet these new audiences, these new users, these constantly changing tools, the lack of real time engagements that accompanies the online environment. (P11)

Below we elaborate on our findings in consideration of the transitioning to online teaching framework developed from the data and integrate our discussion with the major themes of ‘being a pioneer’, ‘changing landscape of teaching’, and ‘the sense of a journey’.

Futuristic educators – ‘Read something, see something and listen to something’

Futuristic educators were those that predominantly revealed positive emotions and perceived a high level of institution support in their transition to OLE. This orientation presented as pioneers who had foreseen the inevitable change and initiated research on how online teaching would work. They were enthusiastic about trying the new technology and different ways of engaging students, albeit with some apprehension. Based on their research, they believed teaching in OLE was feasible and could be implemented.

I was enthusiastic because I was interested to see how it would work and I had a sense that it was a different way of teaching. But I was concerned about all these whizz bang gadgets and technology that I have to learn how to use. (P6)

We had funding … time to really develop it and get together as a team and talk about what we were doing and share resources … we had a plan that was based on the literature about what was required online – read something, see something and listen to something, have engagement with the students … [but] it didn’t mean that there wasn’t any hiccups. (P9)

I became a lot more confident because I was working with a good team of people and they were really collaborative and if I didn’t understand something they would help me and it was a reciprocal relationship. (P4)

I was excited because I was less familiar with (face-to-face) but I knew the content … and we put ourselves in the position of the student and what tools would they need and really right from the beginning in that program and with guidance from the staff we really treated them as two different ways of learning. (P9)

Whilst all educators expressed frustration with students who did not engage, the futuristic educators reported that this was less of a problem and that they were less worried about it because it was the student’s choice. Additionally, when technology failed or was inadequate, they reported feeling less stressed, but rather this provided opportunities for new learning through collaborations with learning advisors.

For the futuristic educators, the ‘sense of journey’ was made as a team and, as such, they did not feel alone. Their journey was supported by colleagues and learning advisors working collaboratively and having a shared and consistent vision of what online teaching would look like. This degree of preparation placed them in a strong position to tackle any technological or pedagogical challenges experienced.

I've become much better at knowing where to put my effort for the most return, for me and my students … The other thing I've changed over time is to really make sure that the online environment is easy to understand and navigate by students … and that’s good for students and it's really good for me, because it means less mucking around during the semester trying to solve [technological] problems. (P6)

Ambivalent educators – ‘It’s just get on with it and you get on with it’

Ambivalent educators were those that were accepting of the imminent changes of transitioning to OLE but perceived having received less institutional support. They were somewhat submissive pioneers and expected that they would and should regulate and control their own learning needs. These ambivalent educators believed it was their professional responsibility to learn how to teach online and they did not expect much support from the institution. Most of these educators felt going online was an institutional directive so they were more concerned about how to apply the principles of the on-campus component to the online version.

No one really talks too much about what you need to be doing with your online students. It’s just get on with it and you get on with it. I’ve just done what I feel is the way to go. (P14)

Absolute frustration with not being able to see and contact them and they enrol in these units and they perhaps don’t engage or they don’t do the readings and they expect to scrape through and you think well, are they completing this unit and not really knowing enough that I would like them to know? Whereas if I see a face to face class, I can sort of tell by their responses in class immediately how they’re going. (P3)

I think as my confidence grows with actually having some real time to play with technology and learn how it … because I didn’t do any of those but that’s a confidence thing for me … (P2)

Disillusioned educators – ‘An environment that is very restrictive’

Disillusioned educators predominately relayed negative emotions about their transition to OLE but perceived that adequate institutional support was provided. These educators presented as rather disillusioned pioneers and expressed frustration and sadness with the current web-based online teaching. One educator felt the learning management system (LMS) was a training model that was restrictive and prevented people reaching their potential. Additionally, he felt frustrated by the consistent attempts to promote the on-campus experience as superior and replicate it online, instead of encouraging creative teaching methods that integrated technology and pedagogy.

[Initially online teaching] was driven by pedagogy … now it is driven by saving money and it really does create an environment that is very restrictive as to what you can do with the technology … there is no instructional design. (P10)

And there’s quite a bit of technology resources available to the students, in order to promote the equity of having one group gets a lecture and one groups just gets a website, trying to actually bridge that gap so that both groups are comparable … so they’ve had a similar background in what’s been taught when you do the assessment. (P10)

Cautious educators – ‘A sort of a fluffy headed academic’

Cautious educators mainly experienced negative emotions and, at the same time, perceived little institutional support during the change process. Their initial responses were of cautious pioneers with emotions such as being hesitant, concerned, sceptical or resentful and, as such, they were the more reluctant pioneers. They were resentful about there being no negotiation about going online and reported feeling overwhelmed and undervalued.

The ‘changing landscape of teaching’ echoed a perception that online teaching was a global phenomenon beyond their control. The move presented unanswered questions about suitability to particular courses, engagement of students and the belief that online teaching was a transmissive and passive mode of pedagogy. Others were sceptical and worried about how a current constructivist teaching orientation would be reconstructed in practice by students. The cautious educators wondered how their specific discipline areas, that required performance or practical skills and immediate feedback, would work in the online mode.

I am concerned about not seeing my students. I am a very hands on, active teacher and I was wondering how I could be as effective as I am on-campus … and just the way I get people involved … students wouldn’t get as much out of the unit as on-campus. (P3)

Most of the cautious educators had been exposed to face-to-face teaching for many years and they were constantly comparing the two modes with a preference for face-to-face teaching. They were happy and confident with their face-to-face pedagogy and delivery of content knowledge, and they were not able to appreciate the relative advantage and compatibility of OLE. Additionally, they were less confident with their knowledge of technology and the virtual environment and this was a major disruption and challenge. There was also a perception that the rapid implementation had not provided ‘time to play’ with the technology to identify its scope and potential nor was there time to observe successful implementation and practices. Consequently, the cautious educators were more likely to feel disempowered, resentful and undervalued.

I felt as an academic my expertise was in a content area that I had learned and developed expertise in communicating, but now I am being expected to learn this new technology that is foreign to me and which I do not enjoy that kind of social discourse. (P11)

The cautious educators often felt alone in their ‘journey’. They were often ‘scrambling to stay ahead’ and were constantly having to learn new things about the LMS and other technological tools. They felt more embarrassed at constantly seeking help because of their lack of familiarity with technology.

So I resorted to posting memes online that position me as a sort of a fluffy headed academic for example, to explain why I was having difficulty with these technologies that the students expected me to be able to use properly. (P11)

Support from the institution

The type of support that was most valued by all the educators was having timely ‘at the elbow’ specialist technical support and this finding aligned with Downing and Dyment (Citation2013). The anywhere anytime support from learning advisors was regarded as invaluable. It included having issues resolved quickly, technical troubleshooting and advice on technical capabilities, but also recognition of a reciprocal relationship with the learning advisor. Overwhelmingly, educators commented on the institution’s underestimation of the time needed to research and implement online teaching and the workload calculations that acted as an inhibitor of progress.

So I think the university needs to recognise if they want us to be on top of these things and institute a really world class online learning – they really need to have a look at how they measure what we do because there’s a whole heap of stuff that we do that’s not measured. (P15)

If we’re going to do this, can I request for time that we actually simulate something … and then [when] students encounter problem I wouldn't have to go to you to help me solve it. (P16)

Implications and conclusions

The current study has revealed orientations that educators experience while transitioning to online teaching. The knowledge and awareness of orientations subscribed to by individual educators can guide institutions to provide unique and targeted support during transitions to online teaching. To facilitate sustainable change, educators need to be at the helm of the design, assessment and facilitation of the transition (Martin et al., Citation2019). Where educators’ orientation to online teaching was positive and supported, the futuristic educators reported being more satisfied with the transition to online in terms of perceived self-efficacy, perseverance, satisfaction, pride, positive student outcomes and appraisals. Where educators' orientations were negative and unsupported, the cautious educators, the outcomes were less satisfying in terms of educators' perceived lower self-efficacy, feelings of inadequacy, resentment, frustration, exhaustion and ill-feeling towards the institution. Support provided in the transition to online teaching should recognise the inherent tensions when technology and pedagogy are combined (Kilgour et al., Citation2019). Such tensions invariably produce emotional reactions that need to be acknowledged in intervention strategies. In transitioning to online teaching, institutions need to respect that educators mostly want to do what is best for students yet require targeted support to overcome hurdles presented by the change process. The challenge facing HE is how to implement innovative yet effective strategies such as people-intensive ‘at the elbow’ support in contexts where workloads are high and budgets are low.

In this study, those who deemed their implementing of online teaching to be successful, the futuristic educators, experienced many of the conditions espoused by Rogers (Citation2003) and subsequent positive emotions. They were given time to initiate and systematically design content by working backwards from desired learning outcomes, assessments, activities, and learning technologies; time to trial and develop meaningful, consistent and common LMS that were designed around student needs; and they worked collegially on the development of the course by sharing knowledge, skills and resources (Martin et al., Citation2019). In contrast, where support was not rendered, educators maintained their professionalism but were more likely to resort to transmissive modes and increased workloads as they tried to replicate the face-to-face delivery. The integration of technology into their pedagogy and content knowledge was not perceived as successful.

This study also contributes to existing literature on how emotions impact HE educators when transitioning to OLE. Educators in this study expressed the full range of emotions from positive elation because they had ‘nailed it’ to negative despair at finding the whole process ‘exhausting’ (Bennett, Citation2014; Downing & Dyment, Citation2013; Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014; McIntosh, Citation2010). Somewhere in between positive and negative was the notion of a neutral or non-committal response that indicated no control or choice so they simply ‘got on with it’. Most importantly, we found that emotions, whether strong or weak, have the potential to make the change process slow and laborious or progressive and rewarding. This has implications for future research because emotions in HE educators are under-researched. Further research is needed to identify developmental changes in the nature and significance of emotions in HE prior to, during and in periods after implementation of changes to delivery modes. For example, do most HE educators begin with cautious orientations, then move to ambivalent, followed by futuristic and then become somewhat disillusioned? Additionally, as this was a cross-discipline study, are there some patterns in emotions consistent with particular discipline areas during the change process?

In these times of rapid change and disruption, such as we experienced with the COVID-19, HE institutions have an obligation to their staff to promote innovation by supporting them in the transition period. Although this research was conducted across a number of schools in the institution and prior to COVID 19, it is somewhat amazing that one institution had such contrasting experiences. Our study suggests that careful implementation strategies will assist with educator retention and in assessing institutional progress in transitioning to OLE.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aitchison, C., Harper, R., Mirriahi, N., & Guerin, C. (2019). Tensions for educational developers in the digital university: Developing the person, developing the product. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1663155

- Bennett, L. (2014). Putting in more: Emotional work in adopting online tools in teaching and learning practices. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 919–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.934343

- Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2015). Technology tools to support learning design: Implications derived from an investigation of university teachers’ design practices. Computers and Education, 81, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.016

- Brinkley-Etzkorn, K. E. (2018). Learning to teach online: Measuring the influence of faculty development training on teaching effectiveness through a TPACK lens. The Internet and Higher Education, 38, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.04.004

- Brown, M. G. (2016). Blended instructional practice: A review of the empirical literature on instructors' adoption and use of online tools in face-to-face teaching. The Internet and Higher Education, 31, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.05.001

- Carbone, A., Drew, S., Ross, B., Ye, J., Phelan, L., Lindsay, K., & Cottman, C. (2019). A collegial quality developmental process for identifying and addressing barriers to improving teaching. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1356–1370. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1645644

- Chen, J. (2018, March). Exploring the impact of teacher emotions on their approaches to teaching: A structural equation modelling approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12220

- Day, C. (2008). Committed for life? Variations in teacher’s work, lives and effectiveness. Journal of Educational Change, 9(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833.007.9054.6 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-007-9054-6

- Downing, J. J., & Dyment, J. E. (2013). Teacher educators’ readiness, preparation and perceptions of preparing pre-service teachers in a fully online environment: An exploratory study. The Teacher Educator, 48(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2012.760023

- Gazza, E. A. (2017). The experience of teaching online in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(6), 343–349. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20170518-05

- Gilmore, S., & Warren, S. (2007). Themed article: Emotion online: Experiences of teaching in a virtual learning environment. Human Relations, 60(4), 581–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707078351

- Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. (2014). ‘I don’t think I could, you know, just teach without any emotion’: Exploring the nature and origin of university teachers’ emotions. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2012.754929

- Han, X., Wang, Y., & Jiang, L. (2019). Towards a framework for institution-wide quantitative assessment of teacher’s online participation in blended learning implementation. The Internet and Higher Education, 42, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.03.003

- Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. Random House Business.

- Howe, D. L., Chen, H.-C., Heitner, K. L., & Morgan, S. A. (2018). Differences in nursing faculty satisfaction teaching online: A comparative descriptive study. Journal of Nursing Education, 57(9), 536–543. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834.20180815.05 doi: https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20180815-05

- Jephcote, M., & Salisbury, J. (2009). Further education teachers’ accounts of their professional identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(7), 966–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.010

- Kilgour, P., Reynaud, D., Northcote, M., McLoughlin, C., & Gosselin, K. (2019). Threshold concepts about online pedagogy for novice online teachers in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1417–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1450360

- Martin, F., Ritshaupt, A., Kumar, S., & Budhrani, K. (2019). Award-winning faculty online practices: Course design, assessment and evaluation, and facilitation. Higher Education, 42, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i1.1329

- McIntosh, K. (2010). E-teaching in e-workplaces: The affective nexus. International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning, 3(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijac.v3i1.998

- Nyanjom, J. (2020). Calling to mentor: The search for mentor identity through the development of mentor competency. Educational Action Research, 28(2), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1559069

- Ouyang, F., & Scharber, C. (2017). The influences of an experienced instructor's discussion design and facilitation on an online learning community development: A social network analysis study. The Internet and Higher Education, 35, 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.07.002

- Perrotta, C. (2017). Beyond rational choice: How teacher engagement with technology is mediated by culture and emotions. Education and Information Technologies, 22(3), 789–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9457-6

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

- Schutz, P. A. (2014). Inquiry on teachers’ emotion. Educational Psychologist, 49(1), 1–12. doi.10.1080/00461529.20.2013.864955 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.864955

- Schutz, P. A., Hong, J. Y., Cross, D. I., & Osbon, J. N. (2006). Reflections on investigating emotion in educational activity settings. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 343–360. doi.10.1007/s10648-006-9030-3

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 53–80). Sage.

- Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302