ABSTRACT

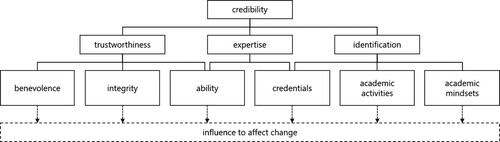

For educational developers (also called academic or faculty developers) to facilitate change toward effective teaching and learning practices at any level, they must build trust and communicate credible expertise, often while conveying ‘second-hand’ educational knowledge to academics who then act on that knowledge in their own work. In this conceptual article, we propose a new credibility framework, drawing on the intertwined literature on trust and trustworthiness, non-positional leadership, cognitive authority, and educational development. Our framework delineates six interrelated dimensions that developers employ to build trust and promote evidence-informed change in their local contexts.

Introduction

Educational development supports change at multiple levels, whether providing holistic support for academics from ‘different disciplinary cultures’, enhancing an institution’s ‘learning and teaching capacity,’ ‘advocat[ing] for the quality of the student learning experience’ (Taylor & Rege Colet, Citation2010, p. 146), or contributing to organizational change (Beach et al., Citation2016). In this article, we use the term ‘educational development’; in some parts of the world, the field is called ‘academic development’ and occasionally ‘faculty development’. (For further reflections on the field internationally, see Leibowitz, Citation2014.) Educational development scholars suggest that to be ‘actively and purposefully engaged in contributing to change’ (Handal, Citation2008, p. 56), developers must build and sustain trustworthiness and credibility, often from in-between spaces (Little & Green, Citation2012; Taylor, Citation2005) or as non-positional leaders (Dawson et al., Citation2010; Timmermans, Citation2014).

Although concerns over credibility and positioning surface in the educational development literature (for example, Fraser & Ling, Citation2014; Sugrue et al., Citation2018), the relationship between trust, credibility, and change in higher education (HE) academic practice has yet to be systematically conceptualized. In compulsory education internationally (for instance, Van Maele et al., Citation2014), the connection between trust in a credible colleague and a teacher’s willingness to reveal vulnerability or engage in informed risk-taking has been well-established. As Wermke (Citation2014, p. 337) notes, teachers ‘reduce the complexity of choices […] by distinguishing sources they do and do not trust. Trustworthy sources of knowledge are then able to transfer their knowledge into the classrooms, whereas sources which are not trustworthy remain peripheral’. Parallel to the compulsory education environment, in HE educational developers are often conveying ‘second-hand’ educational knowledge, teaching and learning strategies, or organizational development research to academics and administrators. In this conceptual article, we examine interrelated factors that developers employ to build trust and promote evidence-informed change in their local contexts. We connect the literature on credibility, trustworthiness, non-positional leadership, cognitive authority, communication, and educational development to propose a credibility framework for educational development.

As a starting point for our framework, we adapt a theory from information science – cognitive authority (Wilson, Citation1983). In Second-hand knowledge: An inquiry into cognitive authority, Wilson (Citation1983) argues that ‘cognitive authority’ – or, knowledge or expertise that is not merely credible, but can also influence one’s thought, opinions, or behavior – is the reason individuals come to trust and act on second-hand knowledge. Wilson distinguishes cognitive authority from two other types: Administrative authority ‘commands’ (p. 14) through structural hierarchies or positional leadership; and institutional authority carries status based on institutional affiliation or reputation (such as a prestigious organization). In contrast, cognitive authority is a ‘kind of influence’ (p. 14) related to credibility (p. 15).

Wilson argues that all three forms of authority have influence. Unlike the other two, though, he argues that cognitive authorities are those we ‘think should be allowed to have influence on [our] thinking’ (Citation1983, p. 14; emphasis ours) – who are valued both as sources of knowledge and for holding opinions one trusts to influence ‘what one thinks about the world’ (p. 128). Being a trusted ‘authority’ who can influence someone’s thoughts, Wilson maintains, is ‘different from being an expert, for one can be an expert even though no one else realizes or recognizes that one is’ (p. 15); one can be the ‘world’s leading authority’ (p. 14) on a subject without necessarily compelling others to trust that expertise.

In our article, we reimagine Wilson’s theory of cognitive authority as a conceptual framework, which, when applied to educational development, helps us describe the features developers rely on to build rapport, encourage reflection, and develop empathy for productive collaboration.

Credibility

Wilson’s exposition of his theory is discursive, loose, and not formalized into a model. In a two-page overview, he envisages cognitive authority as comprised of credibility and influence, with credibility achieved through trustworthiness and competence. Wilson does not dissect influence further, yet does argue that trustworthiness and competence lead to information sources being influential (p. 15). He lists elements of cognitive authority – ‘experience, training, publicly appraisable accomplishment, reputation among peers, reputation among our other cognitive authorities, intrinsic plausibility’ (p. 26) – while noting that none alone is ‘sufficient to establish authority beyond any challenge’.

Wilson’s theory aligns with communication scholars from Aristotle to the present day, who emphasize that successful influence depends on source credibility and that expertise and trustworthiness are the two primary and equally weighted dimensions of that credibility (Hovland et al., Citation1953; Teven & Herring, Citation2005). Some scholars disagree on the umbrella concept, arguing that trust/trustworthiness is a component of credibility (Fogg & Tseng, Citation1999); however, most conclude that both components overlap, and that expertise also plays a role. More recently, information studies scholars have taken up Wilson’s theory (Hilligoss & Rieh, Citation2008; Rieh, Citation2002) and connected it with other research to offer a ‘unifying framework of credibility assessment’ (Hilligoss & Rieh, Citation2008) explaining why readers trust online sources. Their research, like Wilson’s, emphasizes that credibility is not an absolute quality but is established in relationship and ‘relative to the social context in which information seeking is pursued and credibility judgements are made’ (Hilligoss & Rieh, Citation2008, p. 1482).

Studying third-space HE professionals (including educational developers) in the UK, USA, and Australia, Whitchurch provides one way of understanding the dynamic relationship between credibility, authority, and influence as a ‘delicate social contract’ (Citation2013, p. 63): She explores how academic professionals located in boundary-spanning spaces ‘saw themselves as constructing their own authority on a personal and ongoing basis, with minimal recourse to positional authority’ (Whitchurch, Citation2013, p. 71). Whitchurch’s description of the authority third-space professionals exert closely resembles Wilson’s cognitive authority and aligns with other credibility research. Third-space professionals perceive their credibility and influence as dynamic and shifting, rather than static or dependent on structural hierarchy. Whitchurch explains further that for these professionals, ‘influence may lie to a significant extent in the perceptions of others, that these perceptions may need to be managed, and that in practice authority only exists insofar as it can be continuously renewed’ (p. 94).

Such perception management requires interpersonal skills, which also surface in the communication literature on instructor credibility among students – a parallel learning context to that of developers among academics. This research couches such skills as ‘referent power’ (French & Raven, Citation1959, cited in Teven & Herring, Citation2005), based on ‘a student’s positive regard for and personal identification with the teacher, as evidenced by perceptions of similarity or interpersonal affinity’ (Schrodt et al., Citation2008, p. 182). Referent power is often generated and sustained by affinity-seeking behaviors (Frymier, Citation1994), such as listening or supportiveness, making teachers’ attempts to influence student learning more likely to succeed, providing ‘a greater chance to produce more positive learning both affective and cognitive in students’ (Teven & Herring, Citation2005, p. 241). Importantly for the collaborative ethos of educational development, referent power use is found to increase not only the instructor’s credibility and influence, but also the learner’s sense of empowerment (Schrodt et al., Citation2008).

Method: evolution of the framework

My experience of teaching at all educational levels has provided me with insight and skills that are useful in my work; university teaching […] makes me trustworthy among academics and my PhD research (focused on different disciplines within the university) provides insight into different disciplinary cultures which is very useful working with academics from those disciplines (you understand us), and adequate status as a researcher. (Respondent 1092, Education)

Using a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2008), we conducted a textual analysis of these unexpected, seemingly tangential responses (as they focused on indirect and general ways that specialized training informed one’s work), which nonetheless resonated with issues of credibility, authority, and positionality in the educational development literature. Our analysis prompted the question: ‘Which factors contribute to an educational developer’s credibility in influencing change?’ To answer this question, we next reviewed the literature on credibility, trust, and communication, particularly around HE teaching and learning, including Wilson’s (Citation1983) theory of cognitive authority.

Wilson’s theory provided a model for judging the authority of credible second-hand knowledge but does not provide details of how trustworthiness and competence are constructed through communicative acts. To adapt his theory into an explanatory framework for educational developers, we used Hilligoss and Rieh (Citation2008) and Kharouf et al., (Citation2015) to begin distinguishing the constituent components of credibility: Hilligoss and Rieh (Citation2008) propose five components of ‘competence’ for evaluating information sources, while Kharouf et al. (Citation2015) suggest six components of ‘trustworthiness’ for university communication strategies. To these we added seven factors previously identified in the educational development literature that relate to affinity-seeking (Blackmore & Blackwell, Citation2006; Fraser & Ling, Citation2014; West et al., Citation2017), which we originally classified problematically as ‘homophily’, but subsequently reconceptualized as ‘identification.’ Combined, these studies generated a longlist of 21 dimensions to becoming a credible authority as an educational developer ().

Table 1. Longlist of components in educational developers’ credibility formation.

To create a more manageable framework, we turned to the literature in psychology, communication studies (including instructor communication), and management. Research on trustworthiness (Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Mayer et al., Citation1995) and affinity-seeking (Finn et al., Citation2009) suggests that some dimensions in interrelate, so we further condensed associated terms into a six-dimension credibility framework.

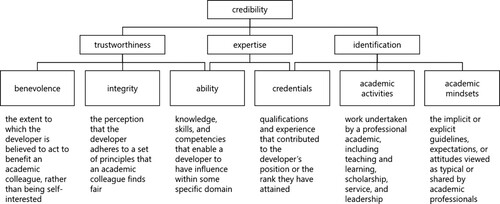

Our development of the framework was also iterative; we tested it with international conference delegates at three stages in development. Responses led us to refine the phrasing of the dimensions presented in . The final framework comprises three major components – trustworthiness, expertise, and identification – divided into six dimensions, which we introduce with illustrative quotations from our previous study. Below we describe the interrelated dimensions that educational developers demonstrate when (re)negotiating credibility with their academic colleagues in the interest of educational change. The framework dimensions contribute to educational developers’ credibility as cognitive authorities, as influence develops over time and through relationships. Our purpose is to bring these dimensions to light and illustrate how they may appear in practice.

Trustworthiness

As a precursor to trust (Mayer et al., Citation1995), trustworthiness is foundational for developers’ credibility. Trust results from ‘an individual’s perception of the characteristics or qualities of specific others, groups, or systems to be trusted’ (Möllering et al., Citation2004, p. 625). By acting in ways that demonstrate trustworthiness, developers foster trust, increasing the likelihood that colleagues will act on a developer’s knowledge and adopt new evidence-based practices or engage in calculated risks with a new pedagogy.

Trustworthiness is a ‘key factor in credibility assessment’, (Hilligoss & Rieh, Citation2008, 1468–1469), whether individuals are assessing the credibility of colleagues, organizational leaders, a second-hand authority, or an information source (Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Wilson, Citation1983). In their meta-analysis of the relationship between trust, trustworthiness, trust propensity, and risk-taking or job performance, Colquitt et al. (Citation2007) distill trustworthiness into three distinct dimensions – benevolence, integrity, and ability – which independently correlate highly with trust (p. 922), reflecting its ‘both cognition-based and affect-based sources’ (Citation2007, p. 918). Like Colquitt et al., we turned to Mayer et al.’s (Citation1995) integrative model to describe these three dimensions of trustworthiness, adapted here to apply to educational development:

benevolence, or the extent to which the developer is believed to act to benefit an academic colleague, rather than being self-interested,

integrity, or the perception that the developer adheres to a set of principles that an academic colleague finds fair, and

ability, or the knowledge, skills, and competencies that enable a developer to work effectively within some specific domain.

Benevolence

I think my ‘people’ awareness is crucial in this current role. […] I stay in the role because of the joy of working with and learning with and from people who look at the world in different ways – all with a view to supporting their engagement with students in similarly inclusive, curious ways. (Respondent 1124, Social Sciences)

Integrity

I am committed to the value of research, to conducting research in ways that are ethical and useful, and to ensuring that theory and practice are consistently informing one another. […] my work as an educational developer is informed by my training as an academic learner, researcher, and teacher. (Respondent 710, Interdisciplinary)

Educational development practice explicitly includes values and ethical guidelines (for example, Knight & Wilcox, Citation1998; Taylor & Rege Colet, Citation2010) that echo descriptions of integrity in the literature on trust and trustworthiness, including such professional values as ethicality, honesty, fairness, reliability, and consistency. Integrity can be demonstrated by, for example, maintaining confidentiality, clarifying goals, outcomes, and parameters, engaging in evidence-based practices congruent with ones we encourage colleagues to use, and promoting just and equitable access to knowledge and learning. Meanwhile, when senior leaders invite educational developers to collaborate on institutional initiatives, developers’ reputations will increasingly depend on maintaining awareness of any ‘consequential risks to integrity’ (Sugrue et al. Citation2018, p. 2347) that could negatively affect our work with academics.

Ability

Working collaboratively, problem solving, leadership, action research are all vital to my developer role, which I learnt and refined when an academic teaching my discipline. (Respondent 1066, Nursing)

Expertise

I am primarily a grad student developer and our PhD students and postdocs are primarily in STEM fields, so my position requires a PhD in STEM. (Respondent 880, Natural Sciences)

ability, or the knowledge, skills, and competencies that enable an educational developer to work effectively within a specific domain, and

credentials, or qualifications and experience that contributed to the developer’s position or the rank they have attained.

Expertise figures prominently in the credibility literature and its dual dimensions overlap with the other two categories: with trustworthiness (as ‘ability’) and identification (through ‘credentials’). We include it as a separate component to emphasize that expertise includes both ‘the perceived knowledge, skill, and experience’ (Fogg, Citation2003, p. 124, emphasis ours) and the actual knowledge, skill, and experience necessary for a source to be trusted. The expertise required for educational development varies locally and regionally and is evolving: There is no standard preparation or degree program, developers enter with postgraduate degrees in varied disciplines (see, for example, Beach et al., Citation2016), and their practices may vary based on institutional and national contexts and agendas (Saroyan & Frenay, Citation2010). However, comparative analyses across national contexts reveal sets of shared professional values, practices, abilities, and skills that comprise expertise in the field (Beach et al., Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2010; DiNapoli et al., Citation2010; Sugrue et al., Citation2018).

Ability

Ability not only signals trustworthiness, as described above, but also demonstrates specific expertise pertinent to the moment. Such abilities may include developers’ academic and practical skillsets (Baume & Popovic, Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2010), as well as discipline-specific expertise, either for interacting with discipline-based audiences or for ‘opening doors’ as the situation demands. Abilities that developers learned in their prior disciplines sometimes, though not always, transfer to their current educational development work, with survey respondents referencing, for example, communication, analysis, critical thinking, management, and metacognition.

Credentials

‘Credentials’ are verified qualifications, akin to Wilson’s ‘training,’ ‘occupational specialization’ or ‘publicly appraisable accomplishments’ (p. 26). They often act as shorthand for expertise, validating one’s academic training – in the above example, both of degree and of discipline – or indicating a level of achievement, such as academic rank. Complicating matters, credentials may verify one’s training and experience, even when they are not directly related to educational development or required to complete a job successfully (Whitchurch, Citation2013, p. 88). Whitchurch notes that ‘credibility could be as much to do with the “mystique” of academic qualifications, as being qualified for the job in hand’, with a doctorate acting as ‘magic dust that could provide a turnkey in offering credibility, gaining entry to academic networks and developing their career’ (p. 88). Credentials may therefore function as proxies for expertise, offering reassurance to academics who are considering changing their practices. As one conference delegate wrote, ‘Because I’m a full professor, I might play this card to counter some of the criticism from other full professors. I wouldn’t lead with rank, but it might come into play later’ (participant 16, 2018).

Identification

The final overarching component in our framework – ‘identification’ – encapsulates developers’ academic credentials, their activities in teaching, research, and service, and their academic mindset as dimensions of credibility. Under various guises, identification is a recurring theme in educational development, particularly in studies examining how developers mirror the academic colleagues they work with or model those colleagues’ ideas of exemplary practice (Baume & Kahn, Citation2004; Blackmore & Blackwell, Citation2006; Fraser & Ling, Citation2014). As Saroyan (Citation2014) explains:

When ADs [academic developers] share the same rank, status, or responsibilities with faculty, they are more likely to have the confidence to articulate a point of view that is different from others and their contribution may be valued more. […] If faculty do not consider them as peers, they may show less willingness and even resistance to taking on board the suggestions put forward by ADs. (Saroyan, Citation2014, p. 59)

Our model focuses on professional identities, yet we are mindful that these intersect with multiple social identities as developers interact with others in specific contexts. Social identities and contexts shape how individual developers might enact the framework’s dimensions and – particularly for developers with minoritized identities – greatly shape the extent to which the dimensions may seem important to accentuate, understate, or explicitly resist. Research suggests identification is complicated by inherent biases and stereotypes about group membership, especially when an in-group feels its values or distinctiveness are somehow threatened (Voci, Citation2006); similar prejudices around ‘belonging’ occur across the academy, around both social (Bernhagen, Citation2019; Plank, Citation2019) and professional identities (Ginsberg, Citation2011).

When facilitating change, finding credibility through professional identification runs cognitive risks, too: As Poole et al., (Citation2019, p. 68) note, ‘valuable learning opportunities are to be had by exploring dissimilar views’ (emphasis ours), concurring with Wilson’s observation that inevitable bias ensues when ‘the people we know best tend to be much like ourselves’ (p. 33) – one reason we rejected ‘homophily’ as a label for this framework component. Like Saroyan above, we divide identification into three dimensions:

Credentials, or qualifications and experience that contributed to the developer’s position or the rank they have attained.

Academic activities, or work undertaken by a professional academic, including teaching and learning, scholarship, service, and leadership.

Academic mindsets, or the implicit or explicit values, norms, expectations, or attitudes viewed as typical or shared by academics.

Credentials

Being an academic and having a scholarly background allows me to talk to faculty like one of them. (Respondent 1018, Cultural Studies)

Academic activities

As an academic developer holding an academic position it is important to be involved in all aspects of academic work (teaching, research, publication and administration and policy engagement). why? Because I love working in each of these areas but also it’s important for credibility with colleagues across the institution. (Respondent 972, Education)

In the HE literature, Blackmore and Blackwell (Citation2006) argue that mirroring and modeling are crucial for developers to transform academics’ practice: an ‘integrated view of the developer’s professional identity and role […] will put leaders in academic development into a position that is more congruent with faculty self-perceptions, and enable them to support those in faculty roles more effectively’ (p. 374). Further, they argue developers must ‘have a real appreciation of all the aspects of faculty roles’ (emphasis ours) and demonstrate understanding the connections between those aspects, as exemplified in the quotation above.

This perspective is further supported by Harland and Staniforth (Citation2008) and Brew (Citation2003), who highlight the importance of research activity for developers’ credibility, particularly in research-intensive institutions. In many countries, developers conduct research even when it lies outside their official role (Green & Little, Citation2016).

Academic mindsets

In working with academics, I found that taking the data-driven, academic approach to teaching and learning (It's a process we can understand) has been very successful, gaining considerable traction with those who would not normally be that enthused about academic development. (Respondent 305, Interdisciplinary/Education)

Nonetheless, the HE literature suggests that some common values and norms will likely make educational developers more effective. A study by Poole et al. (Citation2019) reveals that instructors are almost nine times more likely to value individuals with similar beliefs about teaching and learning than those whose views differ. Roxå and Mårtensson (Citation2009, p. 554) likewise find that ‘significant conversations’ typically occur between academics ‘often with similar interests and values’, while Taylor’s (Citation2005) educational development interviewees regard ‘an academic disposition’ an essential attribute (p. 36).

Given the varied teaching and learning regimes in HE, shared academic mindsets developers draw upon may include the value of evidence-based decision-making, academic freedom, intellectual rigor, or, as Handal (Citation2008) proposes, constructive criticism or critique. Having established identification through common mindsets, developers may find themselves better placed to ‘surface the social roots of [disciplinary] frameworks and beliefs’ (Trowler & Cooper, Citation2002, p. 236), leading to more generative educational development work with colleagues.

Conclusions

presents a full picture of cognitive–relational authority in our credibility framework. Like most frameworks, it requires sensitivity to be employed ethically and could be misused if applied rigidly or devoid of contextual considerations. Investigating how the intersecting identities of developers affect how we use or adapt the framework in different scenarios could prove fruitful to help us be further equipped to ‘recognize and negotiate the intersections of power’ (Plank, Citation2019, p. 93) we encounter in HE institutions.

Although here we have focused primarily on conceptualizing the dimensions that contribute to developers’ credibility, this framework also has practical applications: it can serve as a reflection tool for developers to consider how we establish trustworthiness, demonstrate expertise, and communicate identification – or even when and how we choose to (de)emphasize particular dimensions when working with colleagues in specific contexts.

Considering the framework before a consultation, for example, can help us determine whether benevolence will provide a generative starting point for a vulnerable colleague or whether we might need to establish our expertise early for a sceptical one. During a consultation, the framework can prompt meta-cognition and adjustments in the moment: If ideas are not resonating for the consultee, we may decide to verify what academic values they prioritize in order to proceed from a shared point of understanding. After a consultation, too, the framework can provide a reflective diagnostic tool for analyzing which dimensions of trustworthiness, expertise, or identification arose in order to examine and improve one’s educational development practice.

Our aim in this article is to contribute a conceptual tool to our dynamic field to provide a firm footing for credibility in order to influence and promote change to academic practice. Our framework organizes interrelated components of trustworthiness, expertise, and identification to stimulate developer agency, aligned with ethical practice. By foregrounding the interwoven aspects that contribute to credibility and ‘cognitive-relational authority,’ developers’ first-hand engagements with academic colleagues can better lead to constructive use of second-hand knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baume, D., & Kahn, P. (2004). How shall we enhance staff and educational development? In D. Baume, & P. Kahn (Eds.), Enhancing staff and educational development (pp. 183–194). RoutledgeFalmer.

- Baume, D., & Popovic, C. (2016). Advancing practice in academic development. Routledge.

- Beach, A. L., Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., & Rivard, J. K. (2016). Faculty development in the age of evidence: Current practices, future imperatives. Stylus Publishing.

- Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines (2nd ed.). SRHE/Open University Press.

- Bernhagen, L. (2019). Classwork: Educational development and blue-collar sensibility. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 158(158), 25–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20336

- Blackmore, P., & Blackwell, R. (2006). Strategic leadership in academic development. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 373–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680893

- Blackmore, P., & Kandiko, C. B. (2011). Motivation in academic life: A prestige economy. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 16(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2011.626971

- Brew, A. (2003). Research and the academic developer: A new agenda. International Journal for Academic Development, 7(2), 112–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144032000071332

- Brown, T., Goodman, J., & Yasukawa, K. (2010). Academic casualization in Australia: Class divisions in the university. Journal of Industrial Relations, 52(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185609359443

- Burgan, M. (2006). What ever happened to the faculty? Drift and decision in higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). The legacy of Anselm Strauss for constructivist grounded theory. In N. Denzin (Ed.), Studies in symbolic interaction (Vol. 32, pp. 127–141). Emerald Group.

- Cohen, M. A., & Dienhart, J. (2013). Moral and amoral conceptions of trust, with an application in organizational ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1218-5

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

- Dawson, D., Britnell, J., & Hitchcock, A. (2010). Developing competency models of faculty developers: Using world café to foster dialogue. To Improve the Academy, 28(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2010.tb00593.x

- Di Napoli, R., Fry, H., Frenay, M., Verhesschen, P., & Verburgh, A. (2010). Academic development and educational developers: Voices from different European higher education contexts. International Journal for Academic Development, 5(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440903529851

- Eastcott, D. (2016). Coaching and mentoring in academic development. In D. Baume, & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 110–126). Routledge.

- Fanghanel, J. (2009). Exploring teaching and learning regimes in higher education settings. In C. Kreber (Ed.), The university and its disciplines: Teaching and learning within and beyond discplinary boundaries (pp. 196–208). Routledge.

- Finn, A. N., Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., Elledge, N., Jernberg, K. A., & Larson, L. M. (2009). A meta-analytical review of teacher credibility and its associations with teacher behaviors and student outcomes. Communication Education, 58(4), 516–537. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903131154

- Fogg, B. J. (2003). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Fogg, B. J., & Tseng, H. (1999). The elements of computer credibility. In M. G. Williams, & M. W. Altom (Eds.), CHI ‘99: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 80–87). ACM.

- Fraser, K., & Ling, P. (2014). How academic is academic development? International Journal for Academic Development, 19(3), 226–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.837827

- French, J. R. P., Jr., & B., Raven. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). University of Michigan Press.

- Frymier, A. B. (1994). The use of affinity-seeking in producing liking and learning in the classroom. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 22(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889409365391

- Ginsberg, B. (2011). The fall of the faculty: The rise of the all-administrative university and why it matters. Oxford University Press.

- Green, D. A., & Little, D. (2016). Family portrait: A profile of educational developers around the world. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1046875

- Handal, G. (2008). Identities of academic developers: Critical friends in the academy? In R. Barnett, & R. Di Napoli (Eds.), Changing identities in higher education: Voicing perspectives (pp. 55–68). Routledge.

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2008). A family of strangers: The fragmented nature of academic development. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802452392

- Hilligoss, B., & Rieh, S. Y. (2008). Developing a unifying framework of credibility assessment: Construct, heuristics, and interaction in context. Information Processing & Management, 44(4), 1467–1484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2007.10.001

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Holcombe, E., & Kezar, A. (2018). Mental models and implementing new faculty roles. Innovative Higher Education, 43(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-017-9415-x

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

- Kharouf, H., Sekhon, H., & Roy, S. K. (2015). The components of trustworthiness for higher education: A transnational perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1239–1255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.881352

- Knight, P. T., & Wilcox, S. (1998). Effectiveness and ethics in educational development: Changing contexts, changing notions. International Journal for Academic Development, 3(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144980030202

- Leibowitz, B. (2014). Reflections on academic development: What is in a name? International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 357–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.969978

- Lind, E. A. (2001). Fairness heuristic theory: Justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In J. Greenberg, & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 56–88). Stanford University Press.

- Little, D., & Green, D. A. (2012). Betwixt and between: Academic developers in the margins. International Journal for Academic Development, 17(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.700895

- Little, D., & Palmer, M. S. (2011). A coaching-based framework for individual consultations. To Improve the Academy, 29(1), 102–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2011.tb00625.x

- Lycke, K. H. (2010). Epilogue. In A. Saroyan & M. Frenay (Eds.), Building teaching capacities in higher education: A comprehensive international model (pp. 188–201). Stylus.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

- Möllering, G., Bachmann, R., & Lee, S. H. (2004). The micro-foundations of organizational trust. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(6), 556–570. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551480

- Mullinix, B. (2008). Credibility and effectiveness in context: An exploration of the importance of faculty status for faculty developers. To Improve the Academy, 26(1), 173–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2008.tb00508.x

- Plank, K. M. (2019). Intersections of identity and power in educational development. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 159(159), 85–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20351

- Poole, G., Iqbal, I., & Verwoord, R. (2019). Small significant networks as birds of a feather. International Journal for Academic Development, 24(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1492924

- Rieh, S. Y. (2002). Judgment of information quality and cognitive authority in the Web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10017

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks: Exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

- Sarangapani, P. M. (2011). Soft disciplines and hard battles. Contemporary Education Dialogue, 8(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/097318491000800104

- Saroyan, A. (2014). Agency matters: Academic developers’ quests and achievements. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.862622

- Saroyan, A., & Frenay, M. (2010). Building teaching capacities in higher education: A comprehensive international model (pp. 139–167). Stylus.

- Schoorman, F. D. (2002, August 9-14). Discussant. Integrating trust perspectives: Foundations for a revised integrative model of organizational trust [Symposium]. Academic of Management 62nd Annual Meeting, Denver, CO.

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24348410

- Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., Myers, S. A., Turman, P. D., Barton, M. H., & Jernberg, K. A. (2008). Learner empowerment and teacher evaluations as functions of teacher power use in the college classroom. Communication Education, 57(2), 180–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701840303

- Sugrue, C., Englund, T., Fossland, T., & Solbrekke, T. D. (2018). Trends in the practices of academic developers: Trajectories of higher education? Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2336–2353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1326026

- Sutherland, K. A. (2018). Holistic academic development: Is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks.

- Taylor, K. L. (2005). Academic development as institutional leadership: An interplay of person, role, strategy, and institution. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500099985

- Taylor, K. L., & Rege Colet, N. (2010). Making the shift from faculty development to educational development. In A. Saroyan, & M. Frenay (Eds.), Building teaching capacities in higher education: A comprehensive international model (pp. 139–167). Stylus.

- Teven, J. J., & Herring, E. (2005). Teacher influence in the classroom: A preliminary investigation of perceived instructor power, credibility, and student satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 22(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00036810500230685

- Timmermans, J. A. (2014). Identifying threshold concepts in the careers of educational developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.895731

- Trowler, P., & Cooper, A. (2002). Teaching and learning regimes: Implicit theories and recurrent practices in the enhancement of teaching and learning through educational development programmes. Higher Education Research & Development, 21(3), 221–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436022000020742

- Van Maele, D., Forsyth, P. B., & Van Houtte, M. (2014). Trust and school life: The role of trust for learning, teaching, leading and bridging. Springer.

- Van Veelen, R., Otten, S., Cadinu, M., & Hansen, N. (2016). An integrative model of social identification: Self-stereotyping and self-anchoring as two cognitive pathways. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315576642

- Voci, A. (2006). The link between identification and in-group favouritism: Effects of threat to social identity and trust-related emotions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 265–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X52245

- Wermke, W. (2014). Teachers’ trust in knowledge sources for continuing professional development: Investigating trust and trustworthiness in school systems. In D. Van Maele, P. B. Forsyth, & M. Van Houtte (Eds.), Trust and school life: The role of trust for learning, teaching, leading and bridging (pp. 335–352). Springer.

- West, K., Hoessler, C., Bennetch, R., Ewert-Bauer, T., Wilson, M., Beaudoin, J.-P., Ellis, D. E., Brown, V., Timmermans, J. A., Verwoord, R., & Kenny, N. A. (2017). Rapport-building for educational developers. Educational Development Guide Series 2. EDC.

- Whitchurch, C. (2013). Reconstructing identities in higher education: The rise of third space professionals. Routledge.

- Wilson, P. (1983). Second-hand knowledge: An inquiry into cognitive authority. Greenwood.