ABSTRACT

As decolonization of the curriculum in higher education (HE) gains traction, academics may question their positionality and role as actors in the field. The concept of decolonization is contentious, but primarily focuses on uncentering the Western filter through which the world is viewed both socially and academically. Just as Gavin Sanderson has argued, that internationalization of HE requires the internationalization of the academic self, so we discuss how decolonizing the internationalized HE curriculum must begin with the decolonization of the individual. The strategic directions of our three European institutions reflect the tensions reported in international literature between HE as an income generator, and as a public good. In the autoethnographic project underpinning this article, we employed the unconventional Collaborative Analytics methodology and its iterations of share data, share results, share decisions to explore institutional strategy as experienced by academics. Our novel approach may help others reflect on decolonizing as a process of ‘forever becoming’.

Introduction

This article is the collaborative product of five educational researchers and curriculum developers at universities in Belgium, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. We had seen the term ‘decolonization of the curriculum’ emerge in recent years, not least due to the Rhodes Must Fall movement and the subsequent – and ongoing – student protests in other countries (Pimblott, Citation2020). This drove home the message that decolonization of curricula is not only imperative for education in formerly colonized countries, but also in those of the former colonizers. We became interested in the meaning of ‘decolonization’, its relationship to curriculum internationalization, and what it would entail for us as educational professionals in universities committed to inclusion, diversity and global citizenship, but which nevertheless remain Western-centric.

Decolonization of the curriculum, a contested term itself (Bhambra et al., Citation2018), can be viewed as a strategic response of HE institutions (HEIs) to redress past inequalities and injustices, to challenge the dominance of Western knowledge, pedagogy, and research, as well as to question the colonial roots of university practices and curricula (du Preez, Citation2018). Le Grange (Citation2016) frames decolonization as uncentering, displacing, deconstructing; a critical engagement with knowledge to offer a renewed understanding of history, culture and language, and a process of ‘forever becoming’. Smith (Citation2012) recognizes that decolonization is not about turning back the clock, or starting with a clean slate. What unites a decolonized, internationalized, inclusive curriculum is critical engagement with entangled constructions and openness to self and others with ‘respect of difference’ valued for its intrinsic worth (Le Grange, Citation2016).

Individually, we embraced what Smith (Citation2012, p. 24) identifies as ‘the reach of imperialism into “our heads”’. Our challenge, as educators who come from countries and peoples who ‘ravaged’ communities colonially (Smith, Citation2012) was to critically reflect on ourselves and our positions and responsibilities in education. Two of our institutions are involved in a European Community-funded project with South African universities on capacity building for curriculum internationalization through students’ online collaboration. This evoked the familiar discussion on the meaning of internationalization, ‘internationalization at home’, Africanization in the South African context, and the extent to which internationalization is a Western, neo-colonial, and imposed concept (see, e.g., Teferra, Citation2019). Nonetheless, our work with our South African colleagues has focused our attention on how internationalization and decolonization of the curriculum could be viewed as sharing similar aims.

The dilemma for us (and what has underpinned this article) is in negotiating our Western-dominated institutional strategies and policies whilst engaging in viable curriculum internationalization and decolonization practices. Each of us had contradictory feelings regarding our own practice. We were aware of a sense of unease: how could we, as white, privileged Europeans, meaningfully engage with the ongoing conversation (Behari-Leak, Citation2019) about decolonization of the curriculum in the context of the systemic and structural ways in which our HEIs are driving practices? Nonetheless, we are determined to contribute to decolonization intellectually, practically, and meaningfully rather than ‘tokenistically’ (Moosavi, Citation2020, p. 334). We are conscious of our whiteness, and see self-reflexivity as essential in critiquing privilege and power relations to support new conversations that can lead to authentic change – whilst also recognizing decolonial pedagogical change requires a collective effort with institutional support (Gibson & Farias, Citation2020).

In this article, we offer our ‘consciousness raising’ methodological approach as a contribution to scholarship and practice. In the context of Western dominance of HE internationalization, academics might use our approach and findings to help reorientate their thinking on decolonization while recognizing, accounting for, and undoing its inherent exclusivity (Bhambra et al., Citation2018). We therefore begin with the international contextualization for our research question. We next explore our local contexts, then introduce the Collaborative Analytics methodology and its iterations share data, share results, share decisions which we use to structure the remainder of the article, before moving to conclusions.

International context

In 2011, Brandenburg and de Wit (Citation2011) discussed ‘the end of internationalization’, noting that internationalization was developing in unintended directions. Subsequently, the International Association of Universities (Citation2012) called on all universities to:

affirm internationalization’s underlying values, principles and goals [through] pursuit of the internationalization of the curriculum as well as extra-curricular activities so that non-mobile students, still the overwhelming majority, can also benefit from internationalization and gain the global competences they will need (pp. 4–5)

The discourse on internationalization also includes discussion of its Western character, with some authors considering internationalization, including internationalization at home, for example in Africa, ‘coerced’ (Teferra, Citation2019). In our view, however, internationalization of teaching and learning should be determined by the context and by local perspectives, needs and knowledge in interaction with Other perspectives that include the Global South (Guzmán-Valenzuela & Gómez, Citation2019). We also acknowledge that how internationalization is enacted should be determined by each local context (see de Wit et al., Citation2017). IoC is for all students. We believe that internationalization is more than increased mobility, recruitment of international students and growth in branch campuses, which undermine the transformative potential of curriculum internationalization (Joseph, Citation2012). Rather, we contend, IoC should be situated within a decolonized and social justice framework. We support the communication of universities’ moral and social obligations of educating students to be respectful and culturally aware as a requirement of equity and social justice (Gorski, Citation2008). Students should be supported in having their perspectives challenged through knowledge that is inclusive rather than exclusionary of non-Western viewpoints (Santos, Citation2007). Moreover, we view internationalization processes as requiring critical cultural awareness and understanding of ourselves, our positionalities and our world-view and values, which in turn inform our curriculum practices. These practices center on academics’ consciousness about themselves, their approach to curriculum, and the role they play in providing students with relevant global and local perspectives of their discipline that prepare them as global citizens, able to function within complex and multicultural environments (de Hei et al., Citation2020).

At a personal level, Sanderson (Citation2008) discusses ideas around authenticity of academic practices in HE, and how critical reflection and self-reflection of one’s own culture and worldview are key in facilitating a transformative process for academics to internationalize their personal and professional outlooks. Such self-awareness enables a critical gaze on one’s personal value systems, which, by extension, are potentially open to transformation over time in relation to broader cultural interpretations and influences. ‘Authentic’ academic practice is therefore related to a merging of self, professional and academic outlooks: a ‘whole-of-person-transformation’ (Sanderson, Citation2008, p. 286).

Drawing on Sanderson (Citation2008) in that internationalization of HE requires the internationalization of the academic self, our research question therefore asks how decolonizing the internationalized HE curriculum must begin with the decolonization of the individual; and, how an academic might decolonize themselves given their own background and the specific, structural and systemic problems driving HE internationalization and decolonization strategies.

Local context

By reflecting on the local context, the institutional factors that influence our responses to decolonizing the internationalized HE curriculum can be better understood. Our three institutions are a convenience sample since they are the authors’ chosen places of work whose strategic direction we largely support. We do not present them as typical of European HEIs, or representative of their countries. Rather, they are exemplars of institutions in Europe which employ researchers in IoC and decolonization practices, being neither especially different from, nor especially similar to, each other.

University A (UA), UK

Internationalization is firmly embedded in the current UA Education Strategy, with ‘Intercultural Engagement and Internationalization’ being a core UA policy. Whilst the university is explicitly addressing decolonization through curriculum review, and examining the intersection of internationalization and equality and diversity agendas, concerns regarding the economic drivers for internationalization remain.

The university is committed to enabling graduates to acquire the skills to thrive in a global economy. Through ‘Curriculum 2025’, the institution pursues the public good of inclusive curricula that reflect and value the diversity of UA’s students’ backgrounds and experiences, to engender a sense of belonging, and enhance the student experience. Curriculum 2025 includes an explicit element of decolonization, framed in terms of fostering a plurality of voices and deconstructing systems of domination, especially, with adoption of learning and teaching methods to meet the needs and expectations of future students. Students will be involved in co-curating knowledge through open access teaching and learning resources, shared by the academic community.

The creation of the Research Centre for Global Learning (GLEA) in 2017 provided UA with the means of capitalizing on internationalization funding opportunities whilst promoting its beneficial research into internationalization. Current research addresses interculturality in deconstructing epistemologies and curriculum design, content and pedagogy, including interrogating different practices within and across cultures, having regard for the dynamics of class, gender and faith.

In terms of wider curriculum practices, the university has recently formed a ‘Decolonization Network’, bringing together staff and students to share work and practice, and the many challenges and tensions yet to be addressed. While some distrust remains, overall, UA is striving to rebalance any embedded Eurocentric outlook through ‘a deep interrogation of structures that produce inequalities’ (Felix & Friedberg, Citation2019, para. 10).

University B (UB), Belgium

Strategically, UB’s research in the context of internationalization is one of public good. It aims to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (United Nations, Citationn.d.) while cooperating with foreign institutions for quality education and research. The UB philosophy and mission statement is inspired by diverse Christian thinking on aspects that can be considered as related to decolonization through calling for openness to the Other for a just society. Accordingly, the institution’s educational philosophy promotes ‘open mindedness’, ‘contribute to just society’, ‘a self-declared international and intercultural global citizen’, valuing ‘a critical and reflective dialogue with others’, and a ‘glocal engagement and commitment’ (UCLL, Citation2019, p. 3).

UB appears committed to fundamentally question its narratives and assumptions about the way it views the world and to systematically diversify its educational sources and adapt its pedagogies for a diverse student body. Furthermore, UB recognizes that knowledge is constantly evolving, and that new knowledge and questions underpin co-created knowledge. This implies that there is a clear opening for decolonization processes, and suggests that UB has reflected on its policies, and in a public way (arguably more than the other two institutions appear to have done). However, the question remains whether this approach is radical enough to decolonize academics, students and curriculum. The same could be said about UA, and if strategies will indeed serve to impact curriculum practices.

University C (UC), the Netherlands

UC aims to be the most international university of applied sciences in the Netherlands, and the institution has developed strategies to bring the benefits of internationalization to all its students through its curricula. The focus is therefore restricted to internationalization at home as a public good. The benefits of internationalization relate to the specific context of UC’s programs (see Beelen, Citation2020). However, internationalization is not considered an aim in itself but rather as an instrument to achieve global citizenship skills (de Hei et al., Citation2020). The UC mission statement is ‘Let’s change. You. Us. The world.’ This demonstrates that the university wants students and staff to bring positive change: global citizens who make a difference. The three corresponding values mentioned are: curious, caring and connecting. Over the next few years, UC wants to strategically develop its international profile, in terms of promoting global citizenship and establishing networks.

The Centre of Expertise of Global and Inclusive Learning was established to research talent development to be ‘a citizen of the world’, as well as rethinking what it means for all our students, teachers and curricula. The notion of HE responsibility is often framed in terms of ‘social responsibility’ with various dimensions affecting individuals, the local community and region, as well as education policy (Larrán Jorge & Andrades Peña, Citation2017). To fully integrate these concepts in formal and informal curricula requires new leadership that empowers and gives students, lecturers and staff members a voice.

Comparing the three universities

All three universities have values-driven missions that address graduates’ contributions to society. While decolonization is not explicitly found in the missions, policies and strategies of UB and UC, their focus on inclusivity, diverse perspectives and global citizenship cover concerns relevant to the process of decolonization of HE. Both UA and UB identify how ways of knowing should be challenged and co-created. UC, like UA, emphasizes the involvement of students, and what it means to become a global citizen. All three institutions focus on a just society. UC and UA connect this more distinctively to challenging issues of domination and power-relations for their educational objectives and pedagogies. By putting knowledge questions as well as power structures upfront, UAs policy seems to associate with the notion of ‘global epistemic justice’, a key issue of decolonization of global social justice (Dennis, Citation2018, p. 190). UA is explicitly addressing decolonization through its research and projects. At the same time, UA also approaches internationalization as an opportunity for revenue generation and for enhancement of its position in the rankings. These latter considerations do not have relevance for UB and UC. Although there is a clear desire in UA to redress imbalances of power in HE, current institutional policies and practices have not been updated to reflect decolonization activities.

Collaborative analytics methodology

We framed the study that underpins this article with an unconventional analysis methodology: Collaborative Analytics (Wells, Citation2009), an approach which facilitates group research, and which has the ultimate aim of effecting change. It comprises three iterations: share data (gather, communicate, and organize the data), share results (analyze the data, validate conclusions, and develop conclusions), share decisions (report conclusions, coordinate actions, and determine actions). This methodology provides ways of gaining greater insight into our individual and institutional responses towards decolonization, and of identifying specific actions that would allow us to realign them if necessary. Our three iterations are explored below.

Share data

Since our focus is the ‘academic self’, we agreed to adopt an autoethnographic approach to data collection (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007). Through reflexivity, autoethnography helps to reveal feelings and vulnerabilities that may otherwise lie hidden, not just from others, but from oneself (King, Citation2013). Such introspection enables us as white academics to recognize our colonial privilege and its structures of inequality which play out in our workplace (Moosavi, Citation2020, p. 333). Autoethnography is particularly pertinent in the current context because it ‘lies at the intersection of discourses and experiences of Self and Other, Insider and Outsider, Native and Colonialist’ (Anderson & Glass-Coffin, Citation2013, p. 72). Each member of the five-person team created a visualization of their decolonizing self in the form of the ‘map’ of an island, following King (Citation2013). Each map was complemented with a reflexive commentary. These two qualitative moves enabled each individual to explore their insider/outsider positionality regarding their professional context and practices, alongside their more personal values concerning decolonization. Subsequently, we shared our images and our commentaries, and collaboratively explored them.

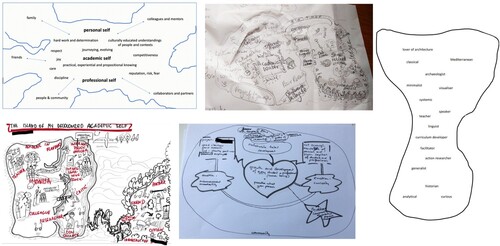

We have debated among ourselves whether the use of maps is, in itself, a colonizing metaphor. The idea of presenting academic identity through the visual metaphor of an island was originally inspired by an artwork by Grayson Perry, RA, entitled ‘Map of an Englishman’ (see King, Citation2013). The irony of such a title was not lost on us. However, we understand Perry intended his map as a critique of cultural norms. The process of mapping is inherently political, yet the mapping of the self is personal. It is a means of presenting ourselves as individuals, each physically separate from everyone while mentally open to collaborations, connections and compromise. Art-based methods, such as these island maps, help to unearth deeper understanding of individuals’ experience and self-view (Kortegast et al., Citation2019). Drawing on Smith (Citation2012), in uncentering Western methodology which often separates mind from body, we sought to consciously view our maps as body, mind, emotion and sense of (academic) self, all interconnected. Botsis and Bradbury (Citation2018) suggest that visualization provides ‘an alternative vocabulary for articulating […] experiences’ (p. 414), and as such can be an effective research strategy when used with multi-lingual individuals, such as several of our team. Our individual visualizations were created manually or digitally, and any lack of artistic skill appeared not to hamper the creation of these maps. The accompanying reflexive commentary allows the creator to add – or suppress – content, examine visual metaphors, consider the island’s topology and labels, their positioning and style of presentation, and reflect on elements that were not included (King, Citation2013). A composite of the ‘maps’ is set out in , providing the reader insight into the diversity of formats rather than detailed content.

Share results

We each found the mapping and reflexive processes uncomfortable, and felt exposed by the subsequent analyses. One digital representation had been ‘unconsciously influenced by the island off the coast of Western Turkey, on which [they] did archaeological fieldwork’. Another presented a landscape rather than an island, suggesting a strong sense of connectivity to others in the academy. A third map took the form of a photograph of a crumpled piece of paper on which the island had been drawn in pencil and inked over, discarded, then recovered from a wastepaper basket. All team members reported finding the visualization process revealing. Each felt the others’ maps were ‘better’ – more thoughtful, or encapsulating more telling characteristics. We allowed ourselves the option of revising the images and texts but, despite having expressed this desire, none of us did. Creating the originals had been a powerful, personal undertaking, the results of which, we felt, could not usefully be altered.

We employed a patchwork of analysis strategies over a six-month period to understand the range of responses that we had captured through our maps and reflexive commentaries. Thematic analysis across the full set of reflexive pieces broadly followed Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). It was initially separated from the visual analysis which, following Botsis and Bradbury (Citation2018), was undertaken for each individual. Both analyses conceptualized themes concerning individuals’ roles, biography, and professional practice – particularly in relation to decolonization. However, as Botsis and Bradbury (Citation2018, p. 415) suggest, visual analysis ‘resists the imposition of a linear form’. The reflexive piece provided scope for each map-author to share their personal values and worldviews, and to discuss the influence of the passage of time on the decolonizing self. Eventually, it became clear, that these elements were also represented in the maps, but in subtle ways through visual imagery which also suggested layers of academic identities. Interpreted through a geographical lens, compass points and topographical features provided insights into individuals’ priorities and relationships with others. Graphical devices illustrated perceived linkages and divisions between self and Other, accountability, community, and ideas around the ‘work-self’ and ‘home self’. The maps also presented numerous different personal and professional selves – ‘teacher’ , ‘linguist’ , ‘sister’, ‘facilitator’ – indicative of our complex lives. Eventually, the two analyses were amalgamated during a face-to-face meeting of the whole team. The four agreed themes are: Personal Values, Struggle, Learning, and The Other.

Personal values

We recognize that decolonization involves a multitude of definitions and interpretations in thinking about the world, colonialism, empire and racism (Bhambra et al., Citation2018). Our conscious awareness of our own racial group provides a lens through which we can frame the decolonial work we are doing.

Our maps and reflections demonstrate that individuals did not separate the personal and professional values they associated with decolonization, whether or not these aligned with organizational values. Working, collaborating, teaching, and living as we do with colleagues, students, and – indeed – partners of different backgrounds, we each welcome every new contact as an equal human being. Our maps and reflections indicate that we proactively take a decolonizing stance in our work and home lives, and confront our privilege daily by trying to change the status quo.

For example, one wrote ‘[I] acknowledge my intertwined professional, personal, and academic-educational-researcher self, and within that the interweaving nature of [these] values’. While another reflected: ‘I am being de-colonized by meeting, working and changing perspectives with colleagues and students from all over the world. Here I receive the best lessons in intellectual humility’.

The islands show the effect of HEI policies on the individual academic, particularly where policies are felt to be misaligned or poorly implemented. For example, one suggested that by enabling placements abroad, they felt guilty of ‘supporting “academic tourism”’. A distancing from certain institutional standpoints is evident in the way we wrote about institutional vocabularies of ‘Low and Middle Income Countries’, ‘the Global South’ and ‘develop[ing] countries’. Along with Kortegast et al. (Citation2019), we found that the initial visual elicitation opened the way to deeper reflection and to challenging colonial undertones encountered in our everyday lives.

At the heart of one map are three bands labeled personal self, academic self, and professional self. Turning the image 180 degrees provides an interesting comparator. Just as ‘South-up’ map orientations help to overcome culturally imposed biases (Marks, Citation1960), so this rotation allows the viewer to see beyond the spatial conventions employed by this map-creator. Viewing the map ‘upside down’ suggests that these bands had expressed a hierarchy with the professional at the bottom, academic in the middle, and personal at the top. Thus, perhaps, the map-author sees their decolonized self as encompassing their personal, professional and academic selves. Our institutions’ policies are not especially helpful in this regard; however, this provides us with a way forward. We are each immersed in decolonization in our everyday personal and academic practice. Over time, this has transformed us. Our maps present our claims to be advocates for decolonizing values through our roles as doctoral supervisors, curriculum developers, academics, researchers, and colleagues.

Struggle

Visual methods may help to uncover ‘participants’ anxieties and challenges’ (Kortegast et al., Citation2019, p. 500). We found that we each struggled in some way with feelings of vulnerability in relation to decolonization. For example, one archipelago of seven islands included two labeled Emotion, and of these, one was explained as representing embarrassment at perceived ignorance in relation to decolonization. Other depictions of struggle include a map which features a ‘Don Quixote’ figure waving their sword, two colleagues talking but with a jagged line dividing their conversation bubbles, and an island of self that is shrinking as cliff-edges crumble into the sea and marshland is engulfed. These graphical images are reinforced in the accompanying reflections.

Research practice itself was defined by one as a site of struggle. However, although they wrote of the importance of recognizing ‘socialized, cultural and epistemic understandings of the self in relation to one-another’, this individual’s map portrayed a collaborative landscape. The struggles against power and control involved in becoming a critical academic (Bernstein, Citation2000) are echoed in our own experience. For one, decolonization was just one more aspect of their private and work lives that felt unbalanced. For another, feeling defensive of their former discipline was characterized as ‘unseen, unvalued, not understood’ by more powerful and established disciplines.

Teaching is also an area of struggle, both on an individual and institutional level. Several maps conveyed struggles to connect different students to the institution – for example, showing them on separate islands or grouped together and dreaming of other lands. One expressed concerns regarding ways of integrating decolonized understandings into their teaching whilst themselves feeling ‘clumsy and ignorant’. Another wrote that decolonization makes us ‘aware of wider implications of colonized power, such as gender, and the links to IoC where so much of the hidden curriculum [has implications for] equity’. Thus, in different ways, we each expressed feelings that being and becoming decolonized involves strenuous personal effort which is largely hidden from others.

Learning

One of us reflected that their former discipline had taught them that ‘facts can be interpreted in different ways’, and that this insight underpinned their critique of institutional policy and the decolonization literature. Another suggested that they had learned to acknowledge ‘the interweaving nature of values, attributes, emotions, skills, knowledges and wider societal influences and relationships’, and that this supported their academic approach. With regard to their teaching, another wrote that their ‘key concern is how to achieve that students acquire critical perspectives on these issues and how we can support lecturers to make such perspectives an integral dimension of teaching and learning for all students’. Thus, the academic self, its power to critique, tolerate and instil these notions in others serves to promote a decolonized mind-set.

As a result of this project, we recognize our institutions as ‘compromised’ (Moosavi, Citation2020, p. 342) yet we are willing to initiate change, for example, by challenging terminology. This perspective is encapsulated in one of the maps which features an island labeled ‘Curiosity’. This was explained as providing the ‘the bridge to get across the gap’ between self and unknown aspects of decolonization.

The Other

While our institutions establish policies to promote tolerance, inclusion, diversity, and global perspectives, we live these lives already. Our maps and reflections convey our attempts to overcome the simplistic binaries that typically gel wider society. One wrote: ‘the more I read on decolonization, the more I’m confronted with the reality of my whiteness, and my [nationality]’. The kinds of research and academic practice we undertake seem to have made us unusually aware of ‘Otherness’. Consideration of the self was connected by one of us to consideration of the hidden curriculum (Leask, Citation2015), and the knowledge that ‘the hidden curriculum is often invisible from the inside and [to] those who grew up in and with that curriculum’. Some of our work colleagues, collaborators and students may perceive us as Other, or we may be suspected of Othering them. We cannot change our cultural heritage but we each strive for equity and mutual understanding.

Three of the five maps comprise multiple islands which represent different selves, or aspects of self. For one map-author, this is an attempt at compartmentalization: ‘Just like my life, my island is split in two’. The map shows links between the two halves, but some are fractured. Another map portrays one island representing a decolonizing academic self, and a second representing the author’s personal life. The author reflected that ‘fault lines characterized the structure of my metaphorical island’, however, their graphical imagery suggests attempts to bridge these fault lines.

Share decisions

When we compare the thematic analysis with the review of our university contexts, we recognize a value perspective, an historic perspective, and a holistic view of people. These elements underpin our discussion.

Decolonization of the academic self as a continual process

Being open to the need to decolonize one’s academic self is a continual process, and one which requires time and (safe) space to engage in often uncomfortable introspection. Our analysis helped us question how internationalization and decolonization relate to our academic selves and how these academic selves relate to our experienced realities and varied university roles. We question how our values, perspectives and concerns relate to those adopted by our universities. This crossroads of positionality and the socio-cultural-political environment outside of work, represents the intersection of professional and personal values which autoethnography is particularly useful at revealing (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007). It also addresses the extent to which our identities are influenced by our former academic disciplines, and by a Western perspective. We have concluded that our sense of struggle and vulnerability is an asset for our roles of researchers and curriculum developers since it increases our perceptiveness and desire to consider, challenge, and confront forms of inequality and coloniality in our classrooms, curricula and campuses.

Considerations for curriculum relationships

William Pinar refocused curriculum on the significance of individual experience, and its ‘alignment with society or the economy’ (Pinar, Citation2011, p. xii). In privileging the individual, Pinar (Citation2011) argued, curriculum is a complicated concept not least because of our difference. Further, as Pinar’s theory of the horizontality and verticality of curriculum studies highlights, horizontality concerns researching curriculum studies from a global to a local level while verticality entails researching the past, present, and future of curriculum studies (Smith, Citation2012). Fundamental questions about being human are clearly part of discourse taking place in global HE communities. Our focus on curricula here relates to the coming together of knowledges, pedagogies, practices and learning communities as an active force of human educational experiences. Our research and focus on the internationalized curriculum reveal how epistemic diversity (Santos, Citation2007), which disrupts white privilege and the normative voice, encourages creativity, and does not distance learners. In this way, we reflect decolonized imaginings of the curriculum as proposed by Hlatshwayo and Shawa (Citation2020).

The need for change in our universities’ policies and strategies

While our universities’ visions, policies and strategies underpin a decolonization approach, it may be argued that a more explicit focus is required to avoid tokenizing the decolonized curriculum and within that the decolonizing of our academic selves. This is particularly relevant where the diversity among academics is considerably less than among students. We contend that universities should offer opportunities for their academic staff to engage in critical dialogue with disciplinary assumptions and hidden curricula. Further, we suggest that the Collaborative Analytics methodology can usefully be employed in academic development activities for colleagues at all levels.

Vandeyar (Citation2020) argues that decolonization of curricula in South Africa will fail if academics are not decolonized. This would apply all the more to European universities, where the drive to decolonize teaching is clearly heard, but where learner demographics have not changed as drastically as in South Africa (Le Grange, Citation2016). In this respect, the challenges for leadership resemble those for the implementation of internationalized curricula. While included in policies, there are generally few strategies in place to stimulate and support meaningful decolonization in teaching, learning and assessment. Mestenhauser (Citation2011) discusses the importance of addressing the ‘dispositions’ of academics to move beyond existing Western paradigms and achieve transformation. This applies equally to decolonization since there are clear similarities between internationalization and decolonization of education as illustrated in the next theme.

Appreciating relationships between internationalization and decolonization

Decolonization promotes the need to revisit the curriculum to redress injustices done to the colonized, while IoC uses cross-cultural engagement to inform understandings and challenge assumptions in the promotion of global relations. A decolonized, internationalized, inclusive curriculum requires critical engagement with such entangled constructions and openness to self and others with respect of difference valued for its intrinsic worth (Le Grange, Citation2016). We recognize the challenge of tackling the mind-sets or ‘dispositions’ of academics, which Mestenhauser (Citation2011) considers obstacles to internationalization. Similarly, Vandeyar (Citation2020) highlights research gaps in our knowledge around decolonizing oneself.

Building on du Preez (Citation2018), our contention is that decolonization and IoC are not opposites, but enable curriculum scholars to rethink the transformative potential of university curricula. Such transformation includes promoting global citizenship, fostering understanding between and amongst cultures, and working collectively to address societal challenges (du Preez, Citation2018). Moreover, as the internationalized curriculum requires attention to knowledge exchange, teaching and learning and community engagement, the ‘why, how and what we teach and research’ should be at the heart of the institution. For this to have impact, it has to start with decolonizing the self – as unlocking one set of relations most often requires unlocking and unsettling the different constituent parts of other relations (Smith, Citation2012). Moreover, drawing on Sanderson’s (Citation2008) internationalization of the academic self, we contend that philosophical self-awareness and critical self-reflection are required for introspective engagement with our own whiteness and ‘Otherness’. Starting at the personal level, and then turning that lens outwards, we better explore and define the necessary support structures and spaces for dialogue required alongside the role of educational developers in these initiatives – as with internationalization (Wimpenny et al., Citation2020). (Re)alignment of individual and institutional responses is required to move beyond the rhetoric of openness, pluralism, tolerance, flexibility, and transparency, towards ways in which decolonization and internationalization are reflected in educational practice.

Conclusion

In this article, we have questioned how an academic might decolonize themselves in the context of structural and systemic problems driving internationalization and decolonization strategies within HE. By adopting Collaborative Analytics, and employing an autoethnographic approach to data capture, we have cooperatively shared our intersecting ideas and perspectives. The three iterations of share data, share results, share decisions have helped us investigate the many facets of decolonization of the academic – itself, a Western perspective. Pursuit of knowledge can be deeply embedded in colonial practices and consequences, yet there is a need for heightened reflexivity, and self-scrutiny in better realizing our decolonial quest as European academics. We recognize how the act of writing for a Western journal is immersed in the Western academy. We appreciate that academic writing involves selecting, arranging and presenting knowledge, privileging text, and considering carefully what issues count as significant. If engaged in uncritically, we could be guilty of rendering indigenous writers invisible or unimportant, while reinforcing the validity of our voices in this article. As Smith (Citation2012, p. 37), asserts: ‘writing … is never innocent’. We therefore write with ‘epistemological vigilance’ (Santos, Citation2007, p. 79).

There are grounds to consider that decolonization and IoC have similarities. Hidden curricula, which have long been a component of the discourse on internationalization of curricula, seem equally relevant in the debate on decolonization. Implementation processes for internationalization and decolonization may also run along similar lines. Yet, even with dedicated university policies, strategies and support, meaningful decolonization ultimately depends on radical investment and focused operationalization initiatives for curriculum transformation to occur. Nonetheless, we also argue that individual responsibility and commitment is required, and at all levels, to engage critically with knowledge to offer a renewed understanding of history, culture and language, in a process of ‘forever becoming’.

Acknowledgements

We thank our peer reviewers for their helpful insights, and Dr Arinola Adefila for her critical friendship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, L., & Glass-Coffin, B. (2013). I learn by going: Autoethnographic modes of inquiry. In S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 57–83). Left Coast Press.

- Beelen, J. (2020). ‘Intelligent internationalization’ at work in The Hague, the city of peace and justice. In K. A. Godwin, & H. de Wit (Eds.), Intelligent internationalization: The shape of things to come (pp. 61–65). Brill.

- Behari-Leak, K. (2019). Decolonial turns, postcolonial shifts, and cultural connections: Are we there yet? English Academy Review, 36(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10131752.2019.1579881

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bhambra, G. K., Dalia, G., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (2018). Introduction: Decolonising the university? In G. K. Bhambra, G. Dalia, & K. Nişancıoğlu (Eds.), Decolonising the university (pp. 1–15). Pluto Press.

- Botsis, H., & Bradbury, J. (2018). Metaphorical sense-making: Visual narrative language portraits of South African students. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 15(2–3), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1430735

- Brandenburg, U., & de Wit, H. (2011). The end of internationalization. International Higher Education, 62, 15–17. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2011.62.8533

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Custer, S. (2019, September 27). ‘Ethical internationalization’ absent from national agendas. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/

- de Hei, M., Tabacaru, C., Sjoer, E., Rippe, R., & Walenkamp, J. (2020). Developing intercultural competence through collaborative learning in international higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 24(2), 190–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315319826226

- Dennis, C. A. (2018). Decolonizing education: A pedagogic intervention. In G. K. Bhambra, K. Nişancioğlu, & D. Gebrial (Eds.), Decolonizing the university (pp. 190–207). Pluto Press.

- de Wit, H., Gacel-Ávila, J., Jones, E., & Jooste, N. (2017). The globalization of internationalization: Emerging voices and perspectives. Routledge.

- de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., & Egron-Polak, E. (Eds.). (2015). Internationalization of higher education. European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies.

- du Preez, P. (2018). On decolonization and internationalization of university curricula: What can we learn from Rosi Braidotti? Journal of Education, 74, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i74a02

- Felix, M., & Friedberg, J. (2019, April 8). To decolonise the curriculum, we have to decolonise ourselves. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/to-decolonize-the-curriculum-we-have-to-decolonize-ourselves/

- Gibson, C., & Farias, L. (2020). Deepening our collective understanding of decolonising education: A commentary on Simaan’s learning activity based on a Global South community. Journal of Occupational Science, 27(3), 445–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1790408

- Gorski, P. C. (2008). Good intentions are not enough: A decolonising intercultural education. Intercultural Education, 19(6), 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980802568319

- Green, W., & Whitsed, C. (2015). Critical perspectives on internationalising the curriculum in disciplines: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health. Sense.

- Guzmán-Valenzuela, C., & Gómez, C. (2019). Advancing a knowledge ecology: Changing patterns of higher education studies in Latin America. Higher Education, 77(1), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0264-z

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Hlatshwayo, M. N., & Shawa, L. B. (2020). Towards a critical re-conceptualization of the purpose of higher education: The role of Ubuntu-Currere in re-imagining teaching and learning in South African higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1670146

- International Association of Universities. (2012). Affirming academic values in internationalization of higher education: A call for action. https://iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/affirming_academic_values_in_internationalization_of_higher_education.pdf

- Joseph, C. (2012). Internationalizing the curriculum: Pedagogy for social justice. Current Sociology, 60(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111429225

- King, V. (2013). Self-portrait with mortar board: A study of academic identity using the map, the novel and the grid. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.751525

- Kortegast, C., McCann, K., Branch, K., Latz, A. O., Kelly, B. T., & Linder, C. (2019). Enhancing ways of knowing: The case for utilizing participant-generated visual methods in higher education research. The Review of Higher Education, 42(2), 485–510. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0004

- Larrán Jorge, M., & Andrades Peña, F. J. (2017). Analysing the literature on university social responsibility: A review of selected higher education journals. Higher Education Quarterly, 71(4), 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12122

- Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. Routledge.

- Le Grange, L. (2016). Decolonizing the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-2-709

- Marks, R. W. (1960). The dymaxion world of Buckminster Fuller. Doubleday.

- Mestenhauser, J. (2011). Reflections on the past, present and future of internationalizing higher education – discovering opportunities to meet the challenges. University of Minnesota.

- Moosavi, L. (2020). The decolonial bandwagon and the dangers of intellectual decolonisation. International Review of Sociology, 30(2), 332–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2020.1776919

- Pimblott, K. (2020). Decolonizing the university: The origins and meaning of a movement. The Political Quarterly, 91(1), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12784

- Pinar, W. F. (2011). The character of curriculum studies: Bildung, currere and the recurring question of the subject. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Sanderson, G. (2008). A foundation for the internationalization of the academic self. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(3), 276–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307299420

- Santos, B. D. S. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review, 30(1), 45–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40241677

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Teferra, D. (2019, August, 23). Defining internationalization – intention versus coercion. University World News, African Edition. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190821145329703

- UCLL. (2019). Moving minds DNA. https://www.ucll.be/sites/default/files/documents/international/brochures/19-20/MovingMinds_DNA/summary_mm_dna.pdf

- United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable development goals. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300

- Vandeyar, S. (2020). Why decolonizing the South African university curriculum will fail. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(7), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1592149

- Wells, D. (2009). Collaborative analytics – an emerging practice. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from http://www.b-eye-network.com/view/9406

- Wimpenny, K., Beelen, J., & King, V. (2020). Academic development to support the internationalization of the curriculum (IoC): A qualitative research synthesis. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(3), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1691559