ABSTRACT

The thesis by publication (TBP) – a collection of standalone articles aimed at publication and accompanied by an explanatory narrative – has grown in popularity over the last two decades. Although research on the TBP is beginning to emerge, it is thus far fragmented. We carried out a scoping review of the literature on the TBP for the years 2000–2020 to assess the current state of knowledge about the TBP and emerging knowledge needs. We identified 65 studies that met our criteria and analyzed what kind of research is emerging (as well as where it is emerging from), what topics are covered, and what recommendations are called for. Our analysis shows that the literature has been dominated by studies focusing on individual TBP experiences and on solving practical challenges surrounding the TBP. We argue that important next steps in research on the TBP will be to move from micro-level analysis of individual experiences to more conceptual studies that seek to analyze the TBP from a meso or macro level – exploring the links between thesis format, doctoral education, and the production of knowledge in a longitudinal perspective.

Introduction

Doctoral education evolves continually throughout the world (Boud & Lee, Citation2009; Thomson & Walker, Citation2010). Massification, professionalization, and increased accountability through various types of quality assurance schemes have characterized some of the major forces for change in recent years (Andres et al., Citation2015). These forces have led to an increased number of doctoral students worldwide (Shin et al., Citation2018) and the diversification of doctoral programs, with the establishment of the professional doctorate, the practice-based doctorate, and the industrial doctorate, among others (Park, Citation2005; Usher, Citation2002). They have also led to curricular changes with increased emphasis on ‘transferrable skills’, career development, and working life relevance (Bao et al., Citation2018). Research analyzing these trends has framed these developments in light of the knowledge economy – where knowledge is the product driving economies and societies – raising the question of how to make the doctoral thesis ‘fit for purpose’ for the current academic workplace (and beyond).

In the public mind, a PhD thesis has traditionally been synonymous with a monograph, a book-length text consisting of several chapters (Kelly, Citation2017). As Paltridge and Starfield (Citation2020) highlight, however, the structure and formats of PhD theses have always been diverse across time, institutions, and disciplines. Although there has been room for considerable variety in what a monograph looks like or includes, the idea of a book-length coherent text has been dominant. The suitability of the monograph format as the default mode through which to display the skills and features of doctoral work, however, has been contested – and more vocally so in recent years – in academic texts (e.g., Cassuto, Citation2015; Paré, Citation2019), policy reports (e.g., CAGS, Citation2018; Hasgall et al., Citation2019) and newspapers (e.g., Jump, Citation2015; Parry, Citation2020). Digital formats, various hybrid formats, or monographs accompanied by published articles are among the alternatives that have emerged (Christianson et al., Citation2015). Amidst the calls for new approaches, the thesis by publication (TBP) – also referred to as article-based thesis, cumulative thesis, manuscript dissertation, manuscript option, integrated format, among others – has become one of the most popular alternative formats to the monograph. Although there are different variants of the TBP depending on institutional and disciplinary context, a key feature is that it comprises several stand-alone texts, rather than a single book-length study. In most cases, local policies dictate that one or more of these must be published, while the others may be in various stages of the submission process, or simply deemed of ‘publishable’ quality. These stand-alone texts are usually accompanied by a narrative that explains the significance of the individual articles and how they represent a coherent body of knowledge. In other words, the TBP is a doctorate in pieces – and the subject of debate about what form it should take, and its role in the changing landscape of academia.

As several scholars have pointed out, the doctoral thesis conceived as a collection of stand-alone texts rather than one book-length study is not ‘new’. Dong (Citation1998) shows that this variety has been available for doctoral students in the sciences in the US since at least the early 1990s. In some contexts, what is known as the ‘PhD by Published Work’, where scholars can apply for a doctorate based on submitting previously published material, has existed alongside traditional PhD programs for decades (Green & Powell, Citation2005). What makes it ‘new’ in the context of the changing doctorate, however, is the shift from this retrospective form to a prospective TBP, where the articles are conceived as part of a single, coherent PhD project from the start (and must be completed, if not published, during candidature).

The emergence of the prospective TBP thesis format has taken different paths in different fields and geographical contexts. For example, in the US and UK it is still a rarity; in Scandinavia it has been the norm for the last decade or so; and in Australia and New Zealand, it is not quite the norm but considered a valid option. And throughout all these regions, it is more common in STEM fields than in the social sciences and humanities. Perhaps because of these different paths, the format remains unsettled: there is no general agreement about the number of texts required, the genres permitted, the role of the narrative, or publication status of the texts submitted.

Given the unsettled nature of the format and its increasing uptake over the last two decades, researchers of higher education, HE institutions, and policy makers will need to be able to critically assess its implications. Although research is beginning to emerge, it is thus far fragmented. The goal of this literature review is therefore to assess the current state of knowledge about the TBP and emerging knowledge needs. We aim to identify what kind of research is emerging (as well as where it is emerging from), what topics are covered, and what recommendations are made.

Our review is based on 65 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters where the TBP is the main focus of the research. We approached the material with the following questions:

Publication trends: What are the basic trends with regard to (i) when the research has been published, (ii) disciplinary context, (iii) geographic context, and (iv) type of TBP examined?

Thematic content: What are key characteristics of research on TBP in terms of research focus, methods, and theory?

Recommendations: What are the recommendations for practice or further research reported in the literature?

Our analysis shows that the literature has been dominated by studies focusing on individual TBP experiences and on solving practical challenges surrounding the TBP. We argue that important next steps in research on the TBP will be to move from micro-level analysis of individual experiences to studies that seek to analyze the TBP from a meso or macro level. While current literature can tell us what writing a TBP means for individuals, we need more studies that ask what the TBP means for disciplines and institutions. We also need more studies with a sustained theoretical engagement that attempt to conceptualize the links between thesis format, doctoral education, and the production of knowledge in a longitudinal perspective.

Materials and methods

We drew our sample from databases covering a wide range of fields and disciplines: Web of Science (including Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Emerging Sources Citation Index), ERIC (Education Resources Information Center – a database specializing in education research), MEDLINE (U.S. National Library of Medicine's database) and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health). Because there is no agreement on terms used to describe this kind of thesis, our search terms and search string attempted to account for the diversity in terminology: ((PhD OR doctor*) AND (dissertation OR thesis)) AND ((manuscript-style) OR (article-style) OR (manuscript-model) OR (manuscript-option) OR (by publication) OR (by portfolio) OR (Scandinavian model) OR (sandwich model) OR (article-compilation) OR (integrated) OR (article-based) OR (alternative format)).

The search was conducted in April 2021 and limited to studies published between 2000–2020 to capture the period when the TBP has emerged as a commonly used alternative. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed research articles and chapters in edited anthologies with an explicit focus on the prospective or retrospective TBP.

We excluded studies that were not published in English because we wanted to ensure that the dataset in our analysis would be possible to evaluate by readers of this English langauge publication. Moreover, our research team lacked the linguistic competence to conduct reliable searches and content analysis in languages beyond English and our own languages (Danish, Norwegian, Swedish), which would have introduced an additional bias in the data. We realize that this decision increases the likelihood that the contexts of the reviewed studies lean heavily towards geographic areas where English is the main language. This bias is a limitation with significant implications which we discuss more in detail in our analysis. We also excluded studies that discuss thesis writing, theses or doctoral education in general, where the TBP was mentioned, but not the main topic of investigation.

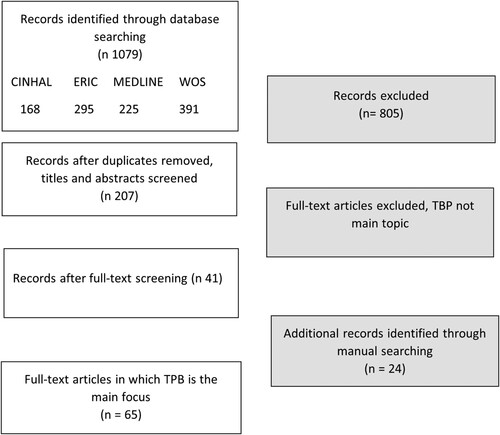

Applying these criteria resulted in a preliminary sample of 41 studies, with WOS and ERIC as the databases that yielded the greatest number of relevant studies with, respectively 32 and 23 relevant studies each, while CINHAL and MEDLINE yielded far fewer, with respectively four and six relevant papers each. We then did a supplemental manual search of the reference lists of the identified studies, a citation search by using the ‘cited by’ feature in Google Scholar, and an additional Google Scholar search using ‘thesis by publication’ as a search term. This manual search yielded another 24 studies, resulting in 65 included studies in total. provides an overview of the process. (See Table S1 in the online supplemental material for full bibliographic information for each article included in the review, as well as information about which database(s) each study appeared in.)

We developed a review matrix consisting of the following categories:

Full bibliographic reference

Field of journal in which the study was published (as determined by journal title or journal's own description of disciplinary focus)

Disciplinary context of the material or participants studied

Geographical context of the material or participants studied

Prospective or retrospective TBP type

Term used for the TBP

Type of study: empirical/conceptual/combined

Theoretical framing/concepts

Methods

Aim

Argument/key findings

Implications/recommendations for policy/practice

Recommendations for research

The studies were first read and charted by each author individually. We then compared our analyses and discussed any disagreements. We resolved disagreements by re-reading the article in question together to reach consensus. None of the categories caused consistent disagreement, suggesting that we understood the categories in the same way.

We used the review matrix to identify the descriptive features of our sample. To classify the thematic content, KS identified the research question/aim and key findings/arguments of each study to pinpoint the aspect of the TPB under inquiry, arriving at three focus areas: experience (experiences, perceptions, opinions, practices of students, supervisors, and examiners), text (characteristics of the publications included, such as number of publications, authorship credit, publication rates, citation rates, and various forms of ‘impact’ or textual and linguistic features), and curriculum (curricular implications for doctoral programs, regional or national policies, and institutions). These categories, in addition to categories for recommendations and knowledge gaps, were reviewed and refined in discussion with LPN.

Publication trends

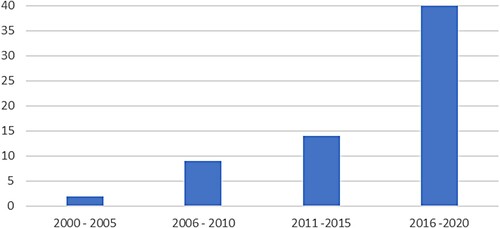

Our first research question seeks to identify the key trends in the publication of TBP research in terms of when the articles were published, disciplinary and geographic contexts, and type of TBP studied. As shows, we found a sharp increase in research interest in the TBP over the period studied, with 62% of the studies published between 2016 and 2020. This trend most likely indicates the increased adoption of the format during the 2010s, with subsequent interest in exploring the implications of this move.

The vast majority of the studies (52) focus on the prospective TBP, with only ten examining the retrospective TBP (and three unspecified). The overwhelming focus on the prospective thesis might indicate that while the retrospective version has existed as an alternative that has been in limited use for a number of years, particularly for those already employed at an academic institution (Green & Powell, Citation2005), the prospective version is seen as a more fundamental and recent change targeting students enrolled in a doctoral program. It might be that researchers perceive the prospective TBP as signaling a shift in traditional doctoral education as an organized program of study writ large.

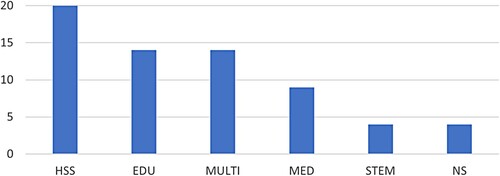

We explored issues of disciplinarity and the TBP by looking at the field of the journals that have published research about the TBP and the fields of the material and participants analyzed in the studies. Forty-five of the studies were published in journals or edited volumes related to the field of education, which is not surprising since the thesis is an important part of doctoral education. If we examine the disciplinary contexts analyzed in the studies (), two observations stand out: first, disciplines within the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) comprise the vast majority of contexts studied; and second, within the HSS disciplines, the field of education dominates. While most HSS disciplines were the topic of no more than two or three studies, the field of education was the topic of 14 studies, which is why we separated it out instead of including it in HSS.

Figure 3. The disciplines investigated in the studies. HSS = Humanities and Social Sciences; EDU = Education; MULTI = Multidisciplinary; MED = Medicine and Health Sciences; STEM = Science, Technology, Engineering, Math; NS = Not specified.

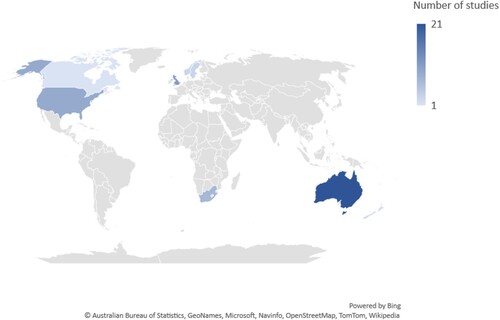

Perhaps because of our search criteria, most studies in our sample were carried out in geographic contexts in which English is the main language (): Australia (21 studies), the United Kingdom (11 studies), the United States (9 studies), and South Africa (7 studies). The only exception to the dominance of English-language contexts is Scandinavia (8 studies), where, as previously noted, the TBP is well-established. It is difficult to know whether the lack of studies from other non-English language contexts is because the TBP has not been adopted there, not been researched, or been researched, but the studies have not been published in English. As such, our search strategy of including only studies published in English leaves us with an incomplete picture, limiting the conclusions we can draw from this review as far assessing possible trends globally.

Thematic content

Our second research question attempts to map the key aspects of the identified studies in terms of research focus, and which methods and theories researchers have used. Below, we examine each of these separately.

Research focus

The studies in our sample explore a broad range of issues, which, as explained in our methods section, we sorted in three main categories: experience, text, and curriculum. Thirty-five studies examine experiences, 13 the thesis text itself, and 11 curricular implications of adopting a TBP. Six studies were difficult to place squarely in one category or the other, so we labeled those ‘combined’.

Within the ‘experience’ focus area, 20 studies in our sample examine experiences from a student perspective, while seven focus on joint explorations of students and supervisors. Three studies focus on the perspectives of examiners, while two examine the experiences of other members of disciplinary and academic communities. Studies focusing on experience typically identify and discuss the challenges and opportunities faced by individuals who have written or supervised a TBP, with the aim of offering advice for doctoral researchers, supervisors, or institutions. One illustrative example is Dowling et al. (Citation2012), where three doctoral researchers and a supervisor provide a co-written account with the aim of highlighting key issues and features of this thesis format for doctoral researchers and supervisors in their discipline.

In the ‘text’ focus area, bibliometric elements and various features of the stand-alone publications included in the thesis feature in 13 studies. For example, Hagen (Citation2010) investigates ‘How many papers does it take to make a PhD?’ and answers the question by conducting a bibliometric analysis of the authorship credit required in different fields and different institutions. Four studies in this focus area examine how the publications and the narrative are presented structurally. Mason and Merga (Citation2018), for instance, analyzed a corpus of 153 theses from Australian universities and identified 11 different ways to structure a TBP.

In the group of studies that examine various curricular aspects, seven look at developments within specific programs or disciplines, three studies focus on geographic regions or countries, and only one explores developments at a specific university. What these studies have in common is an interest in the TBP at a more aggregate level. For example, Graves et al. (Citation2018) analyze the uptake of the TPB in nursing programs in the United States, and Asongu and Nwachukwu (Citation2018) discuss whether the TBP can be seen as a possible way to close the gap in knowledge production between richer and poorer countries.

All studies in the combined category examine experiences in combination with either textual features or curricular issues, such as can be seen in Frick’s (Citation2019) use of her own personal experience to a conduct a more conceptual discussion of the development of doctoral policies and curriculum.

Methodological approaches

Fifty-seven of the 65 studies in the sample are empirical. (See Table S2 in the online supplementary material for classification of individual studies by methods.) The eight studies categorized as ‘conceptual’ primarily engage with existing literature and policy to provide commentary and analysis on some aspect of the TBP; seven of the eight conceptual studies focus on curricular issues. We further subdivided the empirical studies into those that used qualitative (36), quantitative (12), and mixed methods (9). The dominance of qualitative methods is not surprising given the large number of studies that explore experiences, perceptions, and practices – areas of inquiry that lend themselves to qualitative methods.

The most common qualitative approach used in our sample is autoethnography, or personal reflection, with 22 of the studies using some variant of this approach. In addition, the six studies that use a mix of different qualitative approaches rely on personal reflection as one of their methods. The authors of such studies often present themselves as pioneers in their institutional contexts, and the research aims to offer insight into a process considered new or unfamiliar (see e.g., Freeman, Citation2018; Merga, Citation2015; Nethsinghe & Southcott, Citation2015). Nineteen of the autoethnographic studies are from education and other disciplines in HSS, while only one study in STEM and one in Medicine and Health Sciences draw on first-hand experiences (the final study using this approach does not specify the disciplinary context of the study). This trend likely reflects differences in research traditions, where the use of autoethnography and personal experience is a more common methodological approach in HSS than in other fields. The relative newness of the TBP in HSS might also explain the prevalence of first-hand accounts.

Seven of the 12 studies using a quantitative approach examine bibliometric data, often comparing the ‘traditional’ thesis with the TBP in terms of how likely work from the PhD is to be published across formats in order to establish which type of thesis is more ‘productive’ (see e.g., Martin et al., Citation2018; Odendaal & Frick, Citation2017; Urda-Cîmpean et al., Citation2016). The remaining five quantitative studies use surveys to examine changing policies and perceptions and experiences of authorship issues.

Seven of the nine studies with a mixed-method design use survey questions that include both quantitative and qualitative elements, while the remaining two combine a quantitative survey with qualitative interviews. Six of the mixed-method studies focus on experiences of students or examiners, two analyze the thesis text, while one investigates curricular aspects.

In all approaches, there is a notable absence of studies with longitudinal designs. Of course, autoethnographies that retrace the doctoral experience have a longitudinal element, but apart from Gullbekk and Byström (Citation2019) who interviewed students at several points throughout their candidature, no studies have tracked experiences, thesis texts, or curricula over time.

Theoretical approaches

We identified 20 studies that include explicit discussion of theoretical frameworks or concepts. (See Table S2 in the online supplementary material for an overview of the theoretical approach of each article.) Fifteen of these studies adopt concepts related to experience and identity; three studies use concepts that address social and historical developments; and two use concepts primarily attempting to explain textual features.

Given the dominance of studies that explore experiences, the theoretical interest in experience (e.g., writing, or learning) and identity is not surprising. The overall rather low level of explicit theoretical engagement might be somewhat surprising given that a large portion of the sample have been published in education journals, where theorization is typically an important part of knowledge-building practices. However, a potential explanation is that descriptive studies might be considered of more immediate value as a way of documenting what is largely conceived as a new phenomenon and as a way of offering advice on how to write, supervise or assess such a thesis.

Recommendations in the literature

Our third research question seeks to map out the key recommendations for practice and research identified in the literature. All but two of the studies make some kind of recommendation for practice. In this context, ‘practice’ refers to policies and pedagogies surrounding the TBP and doctoral education more broadly. We inductively created three categories for the kinds of recommendations made in the studies: (1) the development of clearer institutional understandings and policies, (2) the development of TBP-specific pedagogies, supervisory practices, and institutional support, and (3) the adoption of the TBP on a wider scale. It should be noted that many studies made recommendations that fit into more than one category (see Table S2 in the online supplementary material for a more detailed overview).

In general, the studies overwhelmingly agree that the TBP is altogether a different proposition than other thesis types and that adopting this format requires the development of TBP-specific policies and pedagogical practices. Some of the most frequently mentioned recommendations include instituting supervisor training, guidelines for ethical issues surrounding co-authorship, writing courses for students, guidelines for examiners, guidelines for students in terms of publication requirements and for the format and content of the narrative. Nineteen studies explicitly position the TBP as a positive development in doctoral education, yet many caution that adoption needs to be carefully considered and that institutional policies and practices need to be in place. It is striking, however, that none of the studies conclude that they would not recommend the adoption of the TBP.

While almost all of the articles in our sample make recommendations for practice, only about half (34) explicitly articulate recommendations for future research. This imbalance in the kinds of implications outlined in the studies indicates that most TBP studies have been geared towards solving practical problems of policies and pedagogies rather than towards developing an area of research. We identified 13 areas that the studies pointed to as future directions, and these areas ranged from issues of research design and methodology to underexplored empirical areas (see Table S3 in the online supplementary material). Below we present and comment on the areas that were mentioned by five or more studies:

First, eight studies mention that there is a need for further exploration of how the emergence of the TBP is both shaped by and shapes conceptualizations of doctoral education. For example, Freeman (Citation2018) and Graves et al. (Citation2018) argue that we lack a sense of the overall prevalence of the TBP, or the reasons PhD programs adopt them; Thomas et al. (Citation2015) suggest we need more research on resistance to the TBP; and O’Keeffe (Citation2020) and Dowling et al. (Citation2012) raise the question of whether the TBP fosters a neo-liberal instrumentalist approach to research and doctoral education.

A second commonly named area for future research, mentioned by seven studies, is the career and publication trajectories of TBP writers – that is, how completing a TBP affects job prospects, career choices, or post-PhD publication patterns. Third, an equal number of studies call for more comparative work with respect to how policies, practices, pedagogies, texts, and experience compare across institutions and disciplines. Fourth, five studies point to the need for comparing potential differences between TBP writers and writers of other thesis formats. While several studies assume that writing a TBP is a different experience than writing a traditional thesis, few have used a comparative design (with the exception of de Lange & Wittek, Citation2014; and Liardét & Thompson, Citation2022). Finally, five studies point to a need for more research about particular aspects of student experiences: support for students writing a TBP (Mason et al., Citation2020; Presthus & Bygstad, Citation2014), co-authoring with supervisors (Thomas et al., Citation2015), TBP writers’ publication practices (Merga et al., Citation2019), and unsuccessful TBP writers (Mason et al., Citation2020b). The remaining eight areas for future research were mentioned by three studies or fewer.

Discussion

This review set out to map current research on the TBP in order to consolidate the state of the field and identify avenues for further research. It should be noted that we have not assessed the quality of the studies, but instead attempted to provide an overview of areas of research interest and how these interests have been pursued, as well as some reasons for why we might be seeing these trends.

Our analysis shows that existing TBP research has been dominated by studies attempting to articulate suggestions for the kind of policies and pedagogical practices that must be in place for institutions and programs considering adopting a TBP. Overall, the conceptual implications of the TBP have not been as thoroughly examined as the more practical implications. This is in line with research on doctoral writing more broadly, which shows that a considerable amount of research in the field attempts to provide ‘solutions’ to writing ‘problems’ (Burford et al., Citation2021, p. 11). And given that so many of the studies document individual experiences, with the aim of sharing those experiences and offering advice to others, the emphasis on practical solutions stands to reason.

We argue that while such advice and recommendations are of great value, the time has come to complement this type of research with studies that ask different kinds of questions focusing on how the emergence of the TBP shapes our understanding of doctoral education and doctoral research. A way to move forward in this respect would be to conduct studies with a more sustained theoretical focus. While some of the studies in our sample connect individual experience to historical and social developments by framing individual experiences in terms of new public management, neo-liberalism or the knowledge economy, few attempt to theorize the TBP in a more sustained way at a macro or meso-level. Rigby and Jones (Citation2020) echo this observation and call for more discussion about the conceptual issues involved in moving from a thesis type that traditionally privileges the educational process over the knowledge product to a thesis type that tends to privilege the thesis as a knowledge product. What does this shift mean for knowledge-building traditions in different fields? Does the increased uptake of the TBP in, for example, the field of education, mean that different kinds of research questions or methodologies are becoming more common while others are becoming less common? And what does that mean for the production of knowledge in that field?

One way to approach these more conceptual questions is to design studies where institutions or disciplines are the main unit of analysis. This might include studies that examine meso-level dynamics of how the TBP shapes collective or disciplinary practices. For example, while the literature indicates that the TBP has been common within medicine for some time, we know little about the historical trajectory of this shift. Has this shift changed curricular practices or the relationship between course work and thesis? Has it had implications for the viva or oral defense (for contexts that have some form of oral defense as part of the thesis assessment)? Although there are a few studies of assessment practices, there is a great need for studying how examiners approach the assessment process and how the TBP shapes ideas of scholarly quality at the doctoral level. Has the emergence of this thesis format shaped the kind of projects deemed suitable and appropriate for a doctoral thesis? Or expectations about what function a thesis serves? In sum, studies that seek to explore insitutional or disciplinary history rather than personal experience would provide us with a focus that is currently not well analyzed. This type of research could help us understand not only how individual stories intersect with disciplinary and institutional structures, but also how the TBP shapes and is shaped by disciplinary and institutional knowledge-making practices. Given the ‘newness’ of the TBP, it is, of course, not surprising that such longitudinal conceptual approaches that we call for here are missing, but as the TBP is now gaining disciplinary and institutional histories in many contexts, we believe such perspectives are important to investigate.

Another way to address more conceptual questions is to explore voices, disciplines, and institutions that are critical of the TBP. While many of the studies in our sample mention wide-spread skepticism towards the TBP, such skepticism is more often used as a framing device to argue against, or at least to temper such critique, rather than acting as the subject of research in and of itself (O’Keeffe, Citation2020 is one exception). It is clear, however, that the format is not universally embraced, as the studies that survey attitudes towards the TBP among faculty members in criminology and criminal justice (Bartula & Worrall, Citation2012) and music (Sims & Cassidy, Citation2016) suggest. To understand the TBP as a window into doctoral education more conceptually, the perspective of such voices should also be examined. In a study that is too recent to be included in our review, Skov (Citation2021) points out that the TBP tends to be intertwined in discourses that emphasize the doctoral thesis as a means to something else (an impressive CV, getting a job, a successful career), what she calls ‘instrumental’ discourses, whereas the traditional monograph is associated with ‘intellectual discourses’ that emphasize the doctoral thesis as an intellectual process of seeking truth and knowledge within a particular discipline. She is careful to highlight that these discourses are not mutually exclusive, and her research shows that doctoral researchers wrestle with these discourses and often construe their choice of format as choosing either instrumentalism or intellectualism, where they see the value of both. Skov's study indicates that the more conceptual work we call for is starting to emerge.

In addition to studies with a more conceptual and theoretical focus, we also see a need for more studies with research designs that rely less on personal experiences of the researchers. Because many of the accounts have been written by candidates or supervisors who have successfully completed a TBP, we know less about the experiences of students who have quit or changed formats (with the exception of Pretorius (Citation2017), who discusses a case where a supervisor recommended that a student switch from a TBP to a monograph). While many of the accounts of successful TBP writers do not shy away from describing challenges, the stories are, ultimately, success stores where the challenges were overcome, and the degree obtained. The prevalence of such first-hand ‘success stories’ might leave less successful stories unexamined, as also observed by Mason et al. (Citation2021). As noted by several studies in our sample, more studies with genuinely comparative research designs are also necessary.

Another key avenue for further research is to broaden the scope of analysis to include studies published in languages other than English. The scope of our study significantly limits what we are able to discern about research on the TPB in contexts where English is not the main language, so expanding the scope to be truly international should be a priority.

A final area we want to mention due to its pressing ethical nature is that in fields where co-authoring is common, more research on pedagogical practices and ethics surrounding co-authorship is needed. One study in medicine shows that as many as 53% of the respondents said they had experienced co-authoring practices that break with the Vancouver guidelines for co-authorship (Helgesson et al., Citation2018). The TBP is likely to make co-authorship a part of the doctoral experience also in fields other than medicine, and this makes researching ethics and pedagogical issues of co-authorship practices particularly important.

In sum, the body of knowledge reviewed here has broken new ground to increase our understanding of the emergence and growing popularity of the TBP. We posit that deeper conceptual engagement and longitudinal perspectives are required for a fuller understanding of what the doctorate in pieces represents for doctoral education and for the production of knowledge more broadly.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (146.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (90.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (468.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andres, L., Bengtsen, S., Gallego Castaño, L., Crossouard, B., Keefer, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2015). Drivers and interpretations of doctoral education today: National comparisons. Frontline Learning Research, 3, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v3i3.177

- Asongu, S. A., & Nwachukwu, J. C. (2018). PhD by publication as an argument for innovation and technology transfer: With emphasis on Africa. Higher Education Quarterly, 72(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12141

- Bao, Y. H., Kehm, B. M., & Ma, Y. H. (2018). From product to process. The reform of doctoral education in Europe and China. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 524–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1182481

- Bartula, A., & Worrall, J. L. (2012). Criminology and criminal justice faculty perceptions of a multi-paper option in lieu of the dissertation. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 23(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2011.590510

- Boud, D., & Lee, A. (2009). Changing practices of doctoral education. Routledge.

- Burford, J., Amell, B., & Badenhorst, C. (2021). Introduction: The case for re-imagining doctoral writing. In C. Badenhorst, B. Amell, & J. Burford (Eds.), Re-imagining doctoral writing (pp. 3–28). University Press of Colorado.

- CAGS. (2018). Report of the Task Force on the Dissertation – Purpose, content, structure, assessment. Canadian Association for Graduate Studies. https://secureservercdn.net/45.40.150.136/bba.0c2.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CAGS-Dissertation-Task-Force-Report-1.pdf.

- Cassuto, L. (2015). The graduate school mess: What caused it and how we can fix it. Harvard UP.

- Christianson, B., Elliott, M., & Massey, B. (2015). The role of publications and other artefacts in submissions for the UK PhD. UK Conference for Graduate Education.

- de Lange, T., & Wittek, A. L. (2014). Knowledge practices: Experiences in writing doctoral dissertations in different formats. Journal of School Public Relations, 35(3), 383–401. https://doi.org/10.3138/jspr.35.3.383

- Dong, Y. R. (1998). Non-native graduate students’ thesis/dissertation writing in science: Self-reports by students and their advisors from two U.S. Institutions. English for Specific Purposes, 17(4), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(97)00054-9

- Dowling, R., Gorman-Murray, A., Power, E., & Luzia, K. (2012). Critical reflections on doctoral research and supervision in Human geography: The ‘PhD by publication.’. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(2), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.638368

- Freeman Jr, S. (2018). The manuscript dissertation: A means of increasing competitive edge for tenure-track faculty positions. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 273–292. https://doi.org/10.28945/4093

- Frick, L. (2019). Phd by publication – panacea or paralysis? Africa Education Review, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1340802

- Graves, J. M., Postma, J., Katz, J. R., Kehoe, L., Swalling, E., & Barbosa-Leiker, C. (2018). A national survey examining manuscript dissertation formats among nursing PhD programs in the United States. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12374

- Green, H., & Powell, S. (2005). The PhD by published work. In H. Green, & S. Powell (Eds.), Doctoral study in contemporary higher education (pp. 69–85). Open University Press.

- Gullbekk, E., & Byström, K. (2019). Becoming a scholar by publication – PhD students citing in interdisciplinary argumentation. Journal of Documentation, 75(2), 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2018-0101

- Hagen, N. T. (2010). Deconstructing doctoral dissertations: How many papers does it take to make a PhD? Scientometrics, 85(2), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0214-8

- Hasgall, A., Saenen, B., Borrell-Damian, L., Van Deynze, F., Seeber, M., & Huisman, J. (2019). Doctoral education in Europe today: Approaches and institutional structures. European University Association.

- Helgesson, G., Juth, N., Schneider, J., Lövtrup, M., & Lynøe, N. (2018). Misuse of coauthorship in medical theses in Sweden. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 13(4), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264618784206

- Jump, P. (2015, May 21). PhD: is the doctoral thesis obsolete? The Times Higher Education Supplement. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/phd-is-the-doctoral-thesis-obsolete/2020255.article.

- Kelly, F. (2017). The idea of the PhD: The doctorate in the twenty-first century imagination. Routledge.

- Liardét, C. L., & Thompson, L. (2022). Monograph v. Manuscript: Exploring the factors that influence English L1 and EAL candidates’ thesis-writing approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1852394

- Martin, W. C., Askim-Lovseth, M. K., & Bateman, C. R. (2018). Monographic versus multiple essay dissertations: A comparison of journal publications in the marketing discipline. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 26(2), 33–43. http://www.mmaglobal.org/publications/JAME/JAME-Issues/JAME-2018-Vol26-Issue2/JAME-2018-Vol26-Issue2-Martin-Lovseth-Bateman-pp33-43.pdf

- Mason, S., & Merga, M. (2018). Integrating publications in the social science doctoral thesis by publication. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1454–1471. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1498461

- Mason, S., Merga, M. K., & Morris, J. E. (2020a). Choosing the thesis by publication approach: Motivations and influencers for doctoral candidates. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(5), 857–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00367-7

- Mason, S., Merga, M. K., & Morris, J. E. (2020b). Typical scope of time commitment and research outputs of thesis by publication in Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1674253

- Mason, S., Morris, J. E., & Merga, M. K. (2021). Institutional and supervisory support for the thesis by publication. Australian Journal of Education, 65(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944120929065

- Merga, M. K. (2015). Thesis by publication in education: An autoethnographic perspective for educational researchers. Issues in Educational Research, 25(3), 291–308. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/merga.pdf.

- Merga, M. K., Mason, S., & Morris, J. E. (2019). ‘The constant rejections hurt’: Skills and personal attributes needed to successfully complete a thesis by publication. Learned Publishing, 32(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1245

- Nethsinghe, R., & Southcott, J. (2015). A juggling act: Supervisor/candidate partnership in a doctoral thesis by publication. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10, 167–185. https://doi.org/10.28945/2256

- Odendaal, A., & Frick, L. (2017). Research dissemination and PhD thesis format at a South African university: The impact of policy on practice. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1284604

- O’Keeffe, P. (2020). PhD by publication: Innovative approach to social science research, or operationalisation of the doctoral student … or both? Higher Education Research & Development, 39(2), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1666258

- Paltridge, B., & Starfield, S. (2020). Change and continuity in thesis and dissertation writing: The evolution of an academic genre. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 48, 100910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100910

- Paré, A. (2019). Re-writing the doctorate: New contexts, identities, and genres. Journal of Second Language Writing, 43, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.08.004

- Park, C. (2005). New variant PhD: The changing nature of the doctorate in the UK. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800500120068

- Parry, M. (2020). The new Ph.D. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 66(22), B26.

- Presthus, W., & Bygstad, B. (2014). Strawberry analysis: Writing a paper-based PhD. Norsk Konferanse for Organisasjoners Bruk av IT, 22(1). http://ojs.bibsys.no/index.php/Nokobit/article/view/46/44.

- Pretorius, M. (2017). Paper-based theses as the silver bullet for increased research outputs: First hear my story as a supervisor. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1208639

- Rigby, J., & Jones, B. (2020). Bringing the doctoral thesis by published papers to the Social Sciences and the humanities: A quantitative easing? A small study of doctoral thesis submission rules and practice in two disciplines in the UK. Scientometrics, 124(2), 1387–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03483-9.

- Shin, J. C., Kehm, B. M., & Jones, G. A. (2018). The increasing importance, growth, and evolution of doctoral education. In J. C. Shin, B. M. Kehm, & G. A. Jones (Eds.), Doctoral education for the knowledge society: Convergence or divergence in national approaches? (pp. 1–10). Springer International Publishing.

- Sims, W. L., & Cassidy, J. W. (2016). The role of the dissertation in music education doctoral programs. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(3), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083715578285

- Skov, S. (2021). PhD by publication or monograph thesis? Supervisors and candidates negotiating the purpose of the thesis when choosing between formats. In C. Badenhorst, B. Amell, & J. Burford (Eds.), Re-imagining doctoral writing (pp. 71–86). University Press of Colorado.

- Thomas, R. A., West, R. E., & Rich, P. (2015). Benefits, challenges, and perceptions of the multiple article dissertation format in instructional technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2573

- Thomson, P., & Walker, M. (2010). Doctoral education in context: The changing nature of the doctorate and doctoral students. In P. Thomson, & M. Walker (Eds.), The Routledge doctoral student’s companion: Getting to grips with research in education and the social sciences (pp. 9–26). Routledge.

- Urda-Cîmpean, A. E., Bolboacă, S. D., Achimaş-Cadariu, A., & Drugan, T. C. (2016). Knowledge production in two types of medical PhD routes—what’s to gain? Publications, 4(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications4020014

- Usher, R. (2002). A diversity of doctorates: Fitness for the knowledge economy? Higher Education Research & Development, 21 (2), 143-153. http://doi.org/10.1080/07294360220144060